Oxford University Press's Blog, page 77

May 29, 2022

When does a kid stop being a kid?

Last summer, my city’s community forum had a post that generated considerable discussion about the meaning of the word kid. Our governor had announced, via Twitter, that “All Oregon kids ages 1-18, regardless of immigration status, can get free summer meals” from the state’s Summer Food Service Program.

Now, everyone agreed that feeding the hungry was a good idea, but someone asked whether an 18-year-old was a kid or not. Shouldn’t 18-year-olds be considered adults, they wondered, not kids?

Other folks weighed in on the kid or not-a-kid question. One suggested that anyone enrolled in a K-12 institution was a “school kid.” Another asked whether people stopped being kids when they reached the age of legal majority or age of consent. Those ages vary by jurisdiction, so one could be an adult in Kansas but still a kid in Nebraska.

The assumption underlying the kid or not-a-kid thread was that someone was either a kid or an adult. But kid, like most words, is polysemous: it has more than one related meaning. Putting aside the young goat business, dictionaries will tell you that kid is an informal term for child and also that child refers to one’s offspring of any age. So, like Schrödinger’s famous cat (or Double-mint Gum), it is possible to be in two states at once: both a kid and an adult.

Ordinary usage bears this out. It’s not uncommon to read about someone’s “adult children” or “grown kids.” And Rick Blaine’s “Here’s looking at you, kid” in Casablanca wasan endearment directed to his former love Ilsa Lund. Rick was using a term of endearment first popularized in a flirty 1909 song called “Oh, you kid.” Kid is no longer much used in that “sweetie-pie” sense, and other slang uses have fallen by the wayside (you can check them out in Green’s Dictionary of Slang, if you are curious). But the nouns kid and kiddo have a long history of being used to refer to adults.

And of course, kid is used as a verb also, meaning to joke or tease. That use remains vibrant today even to the point of being abbreviated as JK. In earlier times, the verb to kid leaned toward trickery and hoaxes rather than what we think of as playful teasing. Is there a connection to kid the noun? The Oxford English Dictionary goes out on a limb to say that the verb is “perhaps” from the noun in the sense of “to make a kid of.”

The flexibility of the noun kid is actually a semantic advantage. It allows speakers and writers to refer to young people in a general way without fussing about the lines between infants, wobblers, toddlers, young children, tweens, and teens.

This flexibility may be why the above-mentioned Tweet writer (almost certainly not the governor herself) chose kids. The alternatives are all a bit clunky: “All Oregon students ages 1-18” is not quite right, since infants, wobblers, and toddlers won’t be in school. “All Oregon children ages 1-18” seems odd in a different way, suggesting that teenagers are children, and “All Oregon youth ages 1-18” seems to single out adolescence. The writer could have tried “All Oregon children and teens, ages 1-18,” or “All young Oregonians, aged 1-18,” but neither of those have the breezy, informal feel of a Tweet.

For me, kids is just right.

Featured image: “Playground equipment at Fu Shan Park in Woodlands, Singapore.” by Wzhkevin. CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

May 28, 2022

Institutional distrust in Britain and America: a history

In the past few decades, trust and distrust have become frequent subjects of journalistic and academic discourse. Much of this literature has dealt with the recent decline or loss of interpersonal trust—the faith or confidence we have in the ability, knowledge, or reliability of other people. We have, it seems, become a much less trusting society than in the past.

There has also been an apparent decline of trust in public institutions, most notably governments, but also law courts, banks, corporations, churches, the media, and universities. In some instances, distrust of institutions has led to a loss of trust in entire political, economic, and legal systems. Much has been written about this decline of institutional distrust, but its chronological parameters have been limited to the last few decades. Distrust of British and American public institutions has, in fact, a much longer and more complex history than most academics recognize. I locate the emergence and development of institutional distrust in Britain and America in the early modern period, which stretched from roughly 1500 to 1815.

Trust in institutions is more difficult to build than trust in people we know personally. The reason for this is that the officials who staff central governments, judges of superior courts, directors of corporations, heads of national banks, and high-ranking clerics in national churches are known to most people only by reputation or exposure in the media. Building trust requires frequent interaction between parties, and that is difficult to achieve between the members of local communities and the “strangers” who run large public institution.

Distrust of political institutions arose in England during the seventeenth century, and it was given theoretical expression by John Locke in Two Treatises of Government (1689). In making the case for resistance against Charles II and James II, Locke argued that all government is, or at least should be, based on trust. If the government violates the trust placed in it, the people (who are sovereign) are justified in forming a new government. Locke’s radical argument became an essential tenet of the Anglo-American liberal tradition. It inspired opposition to the Whig oligarchy in early eighteenth-century Britain and it justified the Patriot cause in the American Revolution of in the 1770s.

Distrust of English law courts also developed during the late seventeenth century, mainly in reaction to the common law judges’ coercion of juries and the violation of defendants’ rights in the political trials of political and religious dissenters in the 1680s. The harshness and unfairness of punishments for all crimes also eroded faith in the entire criminal justice system in both Britain and America in the eighteenth century.

The establishment of the Bank of England in 1694 and the growth of the stock market in the early eighteenth centuries cultivated deep distrust of British financial and commercial institutions. That distrust reached a peak in the South Sea Bubble of 1720, the greatest financial scandal in British history, which led to a loss of trust in the government itself as well as the large stock companies that made profits from the scheme. Distrust of national banks became a recurrent source of distrust in the United States, leading to the failure of the first two national banks in the first half of the nineteenth century.

Distrust of established churches led to the temporary abolition of the Church of England and the Church of Scotland in the seventeenth century and to the separation of church and state in the United States in 1791.

While most of the book deals with the distrust of institutions in the early modern period, the final chapter charts the loss of trust in British and American political, legal, financial, and ecclesiastical institutions in the period from 1970 to 2020. This chapter using polling data from both countries to determine changes in the level of trust in government, the courts, banks, corporations, and churches. It also compares the loss of trust in the early modern period with that of the recent past, recognizing the much larger number and greater complexity of present-day institutions. It also discusses, for the first time in the book, distrust of the media, especially the news media, which were in their infancy in seventeenth-century England. The section on the media emphasizes its recent politization and concludes with a discussion of the Trump administration’s distrust of fact-based bodies of knowledge, especially science, and its broader war against truth itself. These claims against factual knowledge bring to mind the argument of the Scottish philosophers in the eighteenth century who argued that telling the truth was the main condition for trusting other people. That argument remains true today in both Britain and the United States.

Featured image: UK Parliament and Big Ben, by Vicky Yu via Unsplash.

May 27, 2022

The president and the Patriarch: the significance of religion in the Ukrainian crisis

Baffling though this seems to most Europeans, President Putin believes that by invading Ukraine he is defending Orthodox Christianity from the godless West. At his side in this enterprise is Patriarch Kirill, Patriarch of Moscow and all Rus´.

How are we to understand this [un]holy alliance? Here are three ways into the debate: the first is historical and sets the scene; the second explores the fissures within Orthodoxy and their relevance to the current crisis; the third highlights the fault line between East and West Europe.

The story begins in Kyiv, currently the capital of Ukraine. In 988, Grand Prince Vladimir of Kyiv accepted baptism from the Greeks in the Crimean city of Chersonesus; he then ordered the mass baptism of his people in the river Dnipro, a step of huge significance for the subsequent history of Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus. On the one hand this decision marked a move away from the Eurasian steppe and towards Europe, but on the other, the choice of the eastern Byzantine (Orthodox) form of Christianity implied a continuing ambivalence towards Western (Catholic) Europe.

The narrative unfolds century by century and includes for Russia and Ukraine common beginnings, separate medieval and early modern paths, the rise and fall of empire, and the persecution of religion under communism. It has had, however, particular significance as new and independent post-Soviet identities emerged amidst a marked—some would say dramatic—religious revival following the fall of communism. Herein lies the source of the current tension, notably the competing visions of a “Russian World” (Russkii mir) on one side and autocephaly for Ukrainian Orthodoxy on the other. Put differently, does a shared beginning necessarily mean a shared future for Russia and Ukraine?

It is clear that both are predominantly Eastern Orthodox countries. In Ukraine, however, the recent evolution of the Orthodox community is not only complex but pulls in a different direction from its Russian equivalent. From 1992 to 2018, three Orthodox churches were active in Ukraine: the Ukrainian Orthodox Church—Kyiv Patriarchate (UOC-KP); the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church (UAOC); and the Ukrainian Orthodox Church—Moscow Patriarchate (UOC-MP). Initially the UAOC and the UOC-KP were not recognized by other Orthodox churches and were considered “schismatic” by Moscow.

That situation has changed. In December 2018, members of the UOC-KP, the UAOC, and parts of the UOC-MP voted to unite into the Orthodox Church of Ukraine. Early in 2019 the new entity was recognized by Bartholomew, Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, to the profound displeasure of Moscow where views remain unchanged. The shift, moreover, was encouraged by the Ukrainian government, whose support became increasingly visible following the Russian invasion of the Donbas in 2014. The current crisis cannot be understood without taking these tensions into account.

A third factor looks in a different direction: to the concentrations of Catholics (most of whom are Greek Catholics) in the west of Ukraine. In statistical terms the numbers are small (barely 10% of the total population), but the minority serves as a reminder that the territory currently known as Western Ukraine was part of the Second Polish Republic in the interwar period (1918-39)—a situation that reflects a relationship going back to the late Middle Ages. The many spellings of Lviv tell a similar story. The city was known as Lwów by the Poles, as Lemberg by the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and as Lemberik by its Jewish residents. Currently, different language groups maintain their own spelling and pronunciation: hence “Lviv” (Ukrainian) and “Lvov” (Russian).

Borders in this part of Europe have shifted over many centuries in a marchland squeezed between East and West, most recently—and tragically—between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. The key point, however, is the following: Ukraine’s western frontier is open to the West in a way that disturbs both Putin and the Russian Patriarch. Their unease is captured in the extraordinary sermon delivered by the Patriarch on 6 March (the eve of Orthodox Lent) just two weeks after the Russian invasion commenced. Patriarch Kirill sees the Russian campaign as a war to defend Orthodox civilization against Western corruption, symbolised in this case by the holding of gay pride marches.

Much has been written about the relationship between Putin and the Patriarch, most of which lies beyond the present discussion. The crucial fact, however, is abundantly clear: both men see themselves as defenders of an integral Christian culture as Western influence creeps ever closer. Seen from this perspective, Western “ideals”—not least, democracy, a market economy, secularity, diversity, and tolerance—become a threat to civilization itself. Thus, a culture war tips inexorably into a religious one, and becomes all the more difficult to resolve.

One reason why this is so is the incapacity of Western minds to grasp the continuing significance of religion in much of the modern world. That is unfortunate as good social science—including effective policy outcomes—demands that we see the issues from the point of view of the adversary as well as from our own. Only then can effective dialogue begin.

Featured image: The Presidential of Russia Press and Information Office via Wikimedia Commons, public domain

May 26, 2022

10 books to immerse yourself in the world of classical literature [reading list]

The term classical literature refers to the written works of the ancient Greeks and Romans, as well as various other ancient civilizations. While it can be intimidating to approach such imposing and oftentimes heavy works, reading classical literature opens the doors to the innermost thoughts of some of history’s greatest minds and allows the exploration of civilizations long past.

Here are 10 books that we recommend you read if you’re looking to immerse yourself in the world of classical literature, but don’t know where to start.

1. Elegies of Chu

1. Elegies of ChuOne of the two surviving collections of ancient Chinese poetry, Elegies of Chu is a must have on the reading lists of poetry and classical fans alike.

The elegies are a key source for the whole tradition of Chinese poetry and contain passionate expressions of political protest as well as shamanistic themes of magic spells and wandering spirits. Because of this they present an alternative face of early Chinese culture; one that does not align with orthodox Confucianism.

Learn more about Elegies of Chu here.

2. Estate Management and Symposium

2. Estate Management and SymposiumEstate Management and Symposium is a new translation of two of Xenophon’s most famous works.

The Oeconomicus describes Socrates conversing on the topic of successful management of one’s ‘oikos,’ or estate. The focus is a well-to-do Athenian household, which proves a testing ground for the moral qualities of the patriarch, but also a space in which the role of women turns out to be key. Symposium shifts to the men’s quarters of the home, describing an evening of conversation and entertainment at the house of an Athenian plutocrat. The conversation probes timeless questions regarding wisdom, love, and female capacity, and over it looms the deadly serious matter of Socrates’ trial and death.

Discover Estate Management and Symposium.

3. Antigone and other Tragedies

3. Antigone and other TragediesRegarded as one of the greatest dramatists of all time, Sophocles and his works have directly influenced many artists and thinkers over the centuries. As such, we would be remiss to leave him off this list.

Antigone and other Tragedies is comprised of three of Sophocles’ well-known plays: Antigone, Deianeira, and Electra, all of which feature women as their unyielding hero. These three tragedies portray the extremes of human suffering and emotion, turning the heroic myths into supreme works of poetry and dramatic action all with a new and distinctive verse translations which seeks to convey the vitality of Sophocles’ poetry and the vigour of the plays in performance, doing justice to both the sound of the poetry and the theatricality of the tragedies.

Learn more about Antigone and other Tragedies.

4. Epigrams from the Greek Anthology

4. Epigrams from the Greek Anthology Encompassing four thousand epigrams, or short poems, this ramshackle classic gathers up a millennium of snapshots from ancient daily life. Victorious armies, ruined cities, Olympic champions and lovers’ quarrels can all be found between its covers – as well as jokes and riddles, art appreciation, potted biographies of authors, and scenes from country life and the workplace.

This selection features more than 600 epigrams in verse and is the first major translation from the Greek Anthology in nearly a century.

Read more about Epigrams from the Greek Anthology.

5. Fasti

5. FastiOvid’s poetical calendar of the Roman year is both a day-by-day account of festivals and observances and their origins, and a delightful retelling of myths and legends associated with particular dates.

With tones ranging from tragedy to farce, and its subject matter from astronomy and obscure ritual to Roman history and Greek mythology, the poem relates a wealth of customs and beliefs, such as the unluckiness of marrying in May.

Find out more about Fasti here.

6. Constellation Myths

6. Constellation MythsConstellation Myths is the only comprehensive compendium of the ancient myths of the stars and constellations, including the two main sources, Eratosthenes and Hyginus, together with Aratus’ Phaenomena, the earliest surviving account of the Greek constellations. This fascinating collection of mythological stories covers the constellations of the zodiac, the northern and southern skies, and the Milky Way and includes the stories of Europa, Orion’s pursuit of the Pleiades, the kneeling Heracles, Pegasus, Perseus and Andromeda, the golden ram, and many more.

Together with Aratus’s astronomical poem the Phaenomena, these texts provide a complete collection of Greek astral myths; imaginative and picturesque, they also offer an intriguing insight into ancient science and culture perfect for historians and astronomers alike.

Discover Constellation Myths here.

7. The Odyssey

7. The OdysseyThe Odyssey is without a doubt one of the most well-known pieces of classical literature out there.

Homer’s great epic poem encapsulates the power of cunning over strength, the pitfalls of temptation, and the importance of home.

The Odyssey rivals the Iliad as the greatest poem of Western culture and is perhaps the most influential text of classical literature.

Explore more about The Odyssey.

8. The Interpretation of Dreams

8. The Interpretation of DreamsArtemidorus’ The Interpretation of Dreams is the richest and most vivid pre-Freudian account of dream interpretation, and the only dream-book to have survived complete from Graeco-Roman times. Composed in a time when dreams were believed by many to offer insight into future events, the work is a compendium of interpretations of dreams on a wide range of subjects relating to the natural, human, and divine worlds.

Artemidorus’ technique of dream interpretation uniquely stresses the need to know the background of the dreamer, making this work far more than simply a dream dictionary, but also a fascinating social history that reveals much about ancient life, culture, beliefs, and attitudes to the dominant power of Imperial Rome.

Learn more about The Interpretation of Dreams.

9. Six Tragedies

9. Six TragediesIf you’re in the market for something on the darker side, this compilation of six tragedies by Seneca is exactly what you’re looking for.

Tutor to the emperor Nero, Seneca lived through uncertain and violent times, and his dramas depict the extremes of human behaviour. In these works of his passion consistently wins out against reason, and rape, suicide, child-killing, incestuous love, madness and mutilation afflict the characters, who are obsessed and destroyed by their feelings. In his works Seneca forces us to think about the difference between compromise and hypocrisy, about what happens when emotions overwhelm judgement, and about how, if at all, a person can be good, calm, or happy in a corrupt society and under constant threat of death.

Find out more about Six Tragedies here.

10. Phaedrus

10. PhaedrusPhaedrus is widely recognized as one of Plato’s most profound and beautiful works.

It takes the form of a dialogue between Socrates and Phaedrus. The two begin by discussing love, which Socrates describes as a kind of divine madness that can allow our souls to grow wings and soar to their greatest heights. Then the conversation then changes direction and turns to a discussion of rhetoric, which must be based on truth passionately sought, thus allying it to philosophy. The dialogue closes by denigrating the value of the written word in any context, compared to the living teaching of a Socratic philosopher.

Five little-known facts about Dracula

The 26 May 2022 marks the 125th anniversary of Dracula’s publication, although its infamous villain is centuries older. Dracula follows the vampiric Count as he attempts to take over Victorian London. Only a group of ordinary men and women, the Crew of Light—led by the vampire hunter Van Helsing—stand in Dracula’s way.

Despite its reputation as one of the great Gothic novels, there are facts about Dracula that might surprise even the most hardcore fans. Read on to discover five facts you may never have known about Dracula.

1. Dracula could have been a very different novelLike many writers, Bram Stoker went through multiple ideas before coming up with the final plot of Dracula. One early idea was a dinner party at Doctor Seward’s house. Thirteen guests are asked to tell a strange story, their tales connecting once they’ve all been told. Dracula would then crash the party. Other ideas included calling Dracula “Count Wampyr” having one of the Crew of Light killed by a werewolf, and a terrifying scene at the “Munich Dead House.” We know this because of the extensive notes Stoker made, over 100 pages now held in the Rosenbach Museum and Library in Philadelphia.

2. Bram Stoker never visited TransylvaniaDespite being a vital location in Dracula, Bram Stoker never visited Eastern Europe. His notes show that he researched Transylvania extensively, including its folklore and history. In 2019, The London Library discovered the original books that Stoker used in his research, with notes by him in the margins. From E. Gerard’s The Land Beyond the Forest to Rev Albert Réville’s The Devil, 26 books in The London Library have been confirmed as part of Stoker’s research.

3. Dracula was translated into Icelandic—and completely changedDracula was translated into Icelandic in 1901 by Valdimar Ásmundsson, a newspaper editor. The result was Makt Myrkranna, also known as Powers of Darkness. Despite Stoker writing the foreword for this edition, Valdimar Ásmundsson took great liberties when translating the text. When it was translated back into English, it was discovered that Ásmundsson had added more gore and eroticism, cut the novel’s length, and removed the multiple narrators. However, some critics claim Ásmundsson’s prose is better than Stoker’s!

4. Stoker wrote a Dracula play… and it wasn’t very goodOn 18 May 1897, Stoker put on a performance of Dracula before the novel was even published. Adapting plays from unpublished novels was common in Victorian times, as it ensured the author retained dramatic rights to their story. Stoker quickly put together a mixture of extracts from the novel and additional written dialogue. The resulting play was six hours long, with many of Dracula’s most iconic scenes reduced to long speeches. Only two people paid to watch this dramatic reading. Stoker’s boss, actor Henry Irving, refused to play the title role and apparently called the play “dreadful.”

5. Dracula wasn’t based on Vlad the ImpalerIt’s commonly believed that Bram Stoker was inspired to write Dracula after hearing stories about Vlad the Impaler, a Transylvanian prince believed to drink the blood of his enemies. However, Vlad the Impaler is never mentioned in Stoker’s notes for Dracula, despite his deep research into Transylvanian history. Bram Stoker found the name Dracula while on holiday in Whitby. It means “devil” in Romanian and was commonly a surname given to famous (and infamous) figures. The fact that this was one of Vlad the Impaler’s titles, however, is pure coincidence.

May 25, 2022

What does UK law say about sexual harassment in the workplace?

In this blog series, Astra Emir, practising barrister and author of Selwyn’s Law of Employment, explains what UK employment law says about some of the important issues faced by employers and employees.

In this blog series, Astra Emir, practising barrister and author of Selwyn’s Law of Employment, explains what UK employment law says about some of the important issues faced by employers and employees.An MP watching porn in the House of Commons and inappropriate comments made about the deputy leader of the Labour party’s legs: not even the place where our legislation is made appears to be immune from the issue of sexual harassment in the workplace.

Such harassment can take many forms, ranging from serious sexual assault like those committed by Harvey Weinstein, to sex-based comments that one party may find amusing “banter” but the recipient feels are degrading.

Some people at times find it difficult to distinguish between “I was only flirting” or “it’s just a harmless bit of fun’” and the affront to dignity and creation of a hostile working environment that many women (and men) feel that they are subjected to by such conduct, so it is important to know what the law actually says. Here we consider how the law defines sexual harassment and the defences employers and employees can have against a claim, as well as looking at what changes could be made in the future.

Prevalence of harassmentIn 2020, the Government Equalities Office found that 29% of women had experienced at least one form of sexual harassment in the workplace the previous 12 months. This has not diminished with the increase in working from home—nearly one in two women who have experienced sexual harassment at work reported experiencing at least some of it online. 27% of men had also suffered such treatment, although the perpetrators against both were found more likely to be men.

Definition of harassmentThe law is set out in section 26 of the Equality Act 2010. Sexual harassment is defined as “unwanted conduct specifically of a sexual nature or related to gender reassignment and has the purpose or effect of creating an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment for the complainant or violating his or her dignity.”

A single incident can give rise to harassment under this section and, if the conduct is of a sexual nature, the fact that similar treatment is meted out to men as well as to women is irrelevant, as is whether the conduct was intended to violate someone’s dignity or create a degrading environment.

When deciding whether such an environment has been created, the perception of the person making the complaint must be taken into account, as well as the other circumstances of the case, and whether it was reasonable for the conduct to have that effect.

The person does not have to be the direct recipient of the unwanted conduct. They could simply be witness to someone else’s harassment. If the environment at work is degrading, humiliating, hostile, threatening, or offensive it can be felt by all those working in it, even those who are not specifically the targets of the conduct, and the law allows such people to bring an action even if the direct victim chooses not to do so him- or herself.

Also, the conduct does not have to be directed at anyone in particular; for example, if an employer displays any material of a sexual nature, such as a topless calendar. This could amount to harassment of the employees if it makes the workplace an offensive place to work for any employee, whether male or female.

The law also protects someone who has previously rejected conduct of a sexual nature and because of this is treated worse than someone else; for example, they are then refused a promotion because of it.

It can be difficult at times to know where to draw the line between lawful and unlawful conduct, especially when the two sides may view the same incident in different ways. What is simple flirting to one person may be viewed by the subject of it as unwelcome and demeaning harassment. An invitation for a drink after work is hardly unlawful harassment, but it may become so if it is persisted in, or because of the language used or the manner in which it is made. Indeed it was reported that, to avoid this situation, Netflix at one point banned its employees for making eye contact for more than five seconds to avoid claims of harassment. This is an extreme method and may have repercussions for staff welfare but shows that many employers are concerned about what happens when people have a relationship at work. In the United States some firms have a “love contract” to regulate the position between co-workers and protect the employer from claims, and this is increasing in use in the UK. They have taken that route as a preferable option to forbidding relationships between employees.

It should be noted that bullying is a separate issue and not the same thing as harassment.

A person who has been harassed can bring a claim in the employment tribunal seeking compensation. This has to be within three months of the last act of harassment that they are complaining of.

Employee’s defenceIt will be rare that an employee is sued for harassment rather than the employer, simply because it is the employer who will have the means to pay compensation. If they are, however, they can generally defend the case on the basis that either the events did not occur as claimed, or that they did not amount to harassment (because one or more of the elements of the section 26 definition set out above is missing).

Employer’s defenceThere are two types of defence that the employer can use (assuming that harassment did take place):

(a) The employer can show that it took all reasonable steps to prevent the act from occurring and that it acted promptly to deal effectively with the complaint as soon as it was drawn to a manager’s attention.

If an employer has reason to believe that sexual harassment is taking place, it should investigate the matter and take action if necessary, without waiting for a formal complaint to be made. The employer should therefore have effective harassment policies and provide information and training to its staff.

(b) The employer can show that the act did not occur “during the course of employment.”

The law has a doctrine called “vicarious liability.” This means that the case can be brought against the employer as well as, or instead of, the actual perpetrator of the harassment, if it occurred during the course of that person’s employment. An employer can defend itself by claiming that vicarious liability does not apply in a particular case. There is a grey area where office parties and social events organised by employers are concerned, and they depend on the exact facts of each case, and whether the circumstances can be treated as an extension of the employment.

The future of harassment legislationThe main issue with the current law is that it relies on individual enforcement, but often people are too afraid to bring an action in the courts or feel that it won’t make any difference.

A 2018 report by the Women and Equalities Committee made a number of recommendations for change, such as imposing a mandatory duty on employers to protect employees from harassment, which would be punishable by fines, and a duty to conduct a risk assessment for sexual harassment. They also advocated laws making employers take reasonable steps to prevent third parties from harassing their staff. In 2019, the Government responded to a consultation on this but no action has yet been taken.

It is important to tackle this issue not only to protect people from harassment, but also because it affects the happiness of the workforce, and therefore productivity, so there is also an economic element involved. Indeed the TUC also suggests that, “The prevalence of sexual harassment in our workplaces contributes to persistent gender pay gaps as toxic workplace environments create significant barriers to women remaining and progressing at work and can deter women from particular roles or workplaces.” Thus, although women (and men) have an individual right to bring a claim, it is the overall picture that the legislature also needs to address.

Please note that this an overview of the law and is not intended to be legal advice, and each case depends on its own specific facts.

Featured image by LYCS Architecture on Unsplash (public domain)

Idioms: a historian’s view

This is a continuation of

last week’s post

.

This is a continuation of

last week’s post

.Idioms are phrases and often pose questions not directly connected with linguistics. For example, ale is a very ancient word, and its ultimate origin, as could be expected, is a matter of speculation. We have little chance to discover the impulse that made a distant ancestor of modern Germanic speakers use this combination of sounds to designate the beverage whose name is famous in myth (ale has not changed too much from days of yore: the earliest form sounded approximately like aluth-), and we have to admit defeat in the search for the “ultimate” etymology. But it turns out that some moderately witty person once used the phrase Adam’s ale for “water.” The earliest occurrence of Adam’s ale in The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) goes back to 1643, the year Newton was born. The answer to the question about the origin of this phrase is not even worth the time we might spend while looking for it. What will change if we discover the wit’s name? By contrast, learning the origin of ale might shed light on ancient religious beliefs and the technology of preparing alcoholic beverages. It has been suggested that Adam’s ale is a phrase like Welsh rabbit “a cheese dish” and Cape Cod turkey “codfish.” But I am not sure the pattern is the same. Time and again students of idioms find themselves in this situation: they wonder who coined the odd locution and eventually find the author, but much more often they find nothing.

At approximately the same time (before 1635), the phrase ale and history turned up. It became proverbial (though today hardly anyone has heard it). The implication seemed to be that drinking ale is inseparable from telling a good story. Perhaps so. The inventor of the phrase remains undiscovered. It is not even clear whether we are dealing with an idiom. In any case, the OED does not list it. Perhaps language historians have better luck with the champagne to the masthead. The custom of “christening a ship” is old. It consisted in smashing a bottle of wine and throwing it overboard to celebrate the launching of the ship, her virgin voyage, even though champagne was not the earliest choice.

Champagne to the mast and beyond.

Champagne to the mast and beyond.(Via Picryl, public domain)

I came across the champagne to the masthead in an 1862 letter to the British biweekly Notes and Queries and included it in my prospective dictionary of idioms but refrained from the brief commentary given below, because the gloss “plentiful supply of the wine at table” does not seem to have a direct bearing on any ceremony. Apparently, to in the phrase means “all the way to.” But idioms are a slippery field, and I almost never risked adding my commentary. Though the origin of the champagne to the masthead is obviously naval, I’d rather leave the nuance to experts. Some readers of this blog may perhaps add a more enlightening comment. Once again the OED did not find the phrase worthy of inclusion. (I assume that at the OED they have all my materials as a matter of course and that if some item has been left out, it was done after serious consideration, while I may risk some linguistic promiscuity.)

The American version of Hoppin’ John.

The American version of Hoppin’ John.(Photo by srjenkins via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

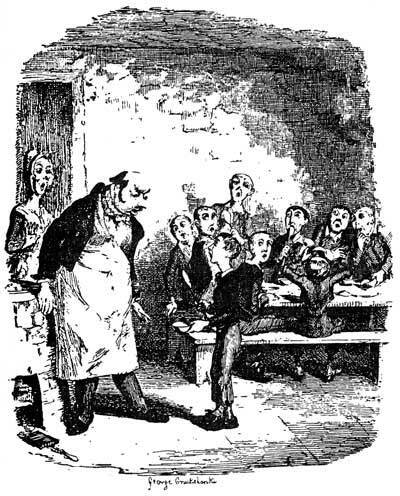

Now here is one more shot at drinking: hopping John. In George Cruikshank’s Three Courses and a Dessert, p. 26 (ed., 1830), this term is applied to half a gallon of cider, qualified by a pint of brandy and a dozen roasted apples, hissing hot. (From hissing to hopping?) The same odd phrase is applied in the southern parts of the United States to a stew of bacon with peas or rice. Thus, not a beverage! (My references are dated 1838 and 1856.) These incompatible uses, the correspondent to the periodical suggested, would seem to be independent of each other (Notes and Queries 1909, Series 10, No. I, p. 487). The OED has no citations before 1838. In America, the only pronunciation of the name of the dish is hoppin’ John and is sometimes treated as a borrowing from another language. Cruikshank is world-famous for his illustrations to the original editions of Dickens’s novels, and he probably knew a local, rather than the American, phrase. So many objects have been called john, from johnny-cake to john “toilet,” that in hopping John, the second word means simply “thing.”

Here is one of Cruickshanks’s celebrated illustrations to Oliver Twist.

Here is one of Cruickshanks’s celebrated illustrations to Oliver Twist.(Via The Charles Dickens Page, public domain)

Names often surprise us in idioms. More than a hundred years ago, in Ireland, Andrew Martin meant “any departure from the established rule by a clergyman.” Perhaps it still does (I have no idea). The trouble is that nothing is known about some riotous or unconventional churchman bearing this name. Andrew Martin is unlike hopping John: presumably, there was a prototype. No one has come up with a suggestion. Urban Dictionary informs us that “Andrew Martin” is the name of the most intelligent and the most attractive male in a group. Men admire him, women all but swoon in his presence. I envy him but wonder: Why Andrew Martin? Still another nautical phrase is Tom Cox’s traverse. “It means the work of an artful dodger, all jaw, and no good in him.” The Internet is full of references to this idiom, and they say the same (“all talk and no work”), but no one seems to be interested in the only question that bothers me: “Who was Tom Cox?” His namesakes, some of them, distinguished individuals, are among us.

Tom Cox’s traverse.

Tom Cox’s traverse.(Photo by Myshun via Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

It will be seen that today I have chosen a few obscure idioms, some of which may have a historical background because of rather distinct names. In the past, I have often written about proverbial phrases with names in them: as lazy as Lumley’s dog, to have got Charley on one’s back, Bobby dazzler, Queen Anne is dead, before you can say Jack Robinson, Davy Jones, and so forth. My point is clear: linguists interested in the origin of idioms should be historians and archeologists. To be sure, all etymologists study “things” and words, but idioms provide a different focus. Who are those skeletons in the closet (or cupboard, if you please): Andrew Martin, Tom Cox, and the rest? Also, some time in the past, I wrote about jerry-builders, very active scoundrels who never existed. My plea is always the same. Perhaps some of our readers will be inspired to join this archeological expedition, and, if not, let George do it!

I have only one thing to add to my series on idioms. The most natural question is about the sources (in addition to the Internet): “Where can we find answers to our queries about the origin of idioms?” Next week I’ll offer a short rundown of such sources and leave this subject behind me.

Featured image via Piqsels (public domain)

May 21, 2022

The possibility of a world without intimate violence

This is an extract from chapter seven, “From Hysteria to Justice,” of Every 90 Seconds: Our Common Cause Ending Violence Against Women by Anne P. DePrince.

This is an extract from chapter seven, “From Hysteria to Justice,” of Every 90 Seconds: Our Common Cause Ending Violence Against Women by Anne P. DePrince.A century and a half ago, doctors averted their collective gaze from the intimate violence in women’s lives to blame hysteria on women themselves. Meanwhile, violence against women continued to be wielded as a weapon of social control, tearing at the fabric of Indigenous and Black communities in the United States. In the 1970s, the women’s movement ushered in an age of awareness that promised change. Awareness-building led us down interconnected paths of criminalization and medicalization. Along those paths, gun laws have saved lives but focusing on criminal legal responses hasn’t deterred violence against women overall. Effective treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) relieved suffering even as the root causes of violence against women persist.

One step forward, two steps back. This has been our dance for decades.

Today, stopping violence against women falls to few. The criminal legal system is charged with enforcing laws. A school delivers prevention programming to the children in attendance that day. A doctor privately addresses a survivor’s pain.

And still, every 90 seconds a woman is sexually assaulted. Another is abused by an intimate partner.

We are not fated to this pattern, though. A world without intimate violence is possible, as much as that sounds like science fiction. After all, social change is science fiction, according to organizer adrienne maree brown. To end violence against women would be to imagine into existence a world that none of us has known and to persuade people that the actions they believe impossible are actually the only and best way forward.

To realize that transformation, we’re going to need a vision that is more compelling than the status quo.

A compelling reasonOur compelling vision starts with finding an irresistible reason for change.

In recent history, we’ve had no shortage of reasons proffered to end violence against women. Protect women. Law and order. Reasons like these get bandied about when intimate violence makes the headlines. Inevitably, some politician—usually a man—stands up to tell us that they care about ending violence against women because they have a daughter, sister, mother, and/or wife.

If stopping violence against women simply required having a daughter, sister, mother, and/or wife, though, we’d have ended it already. Since we haven’t, let’s assume knowing or being related to a woman isn’t a compelling reason for social change.

Personally, I’d prefer we end violence against women and address its many impacts because it’s the right thing to do. Because girls and women, like all human beings, deserve to live lives free of violence and abuse. Because there’s no dignity in being abused, abusing others, or being the person who does nothing despite the knowledge that a woman is harmed every 90 seconds in our communities.

However, we’re not going to stop violence against women because it’s the right thing to do, because we know the facts, or because we’re altruistic. We know this from nineteenth-century France and the many #MeToo moments that have passed us by. We know this from watching interrelated movements to end racism and other forms of oppression where facts and altruism don’t change systems.

What, then, is our compelling reason to move from awareness to action?

Our reason is right there in the interconnections between the issues we each care about: violence against women is inextricably linked to the issues that stoke our greatest passions and affect our communities. Each trip to the emergency room for an injury from intimate violence adds an entirely preventable cost to overburdened healthcare systems. Gun violence in public spaces is often rooted in violence against women. Traumatic stress from witnessing and enduring violence against women disrupts learning in schools, from kindergarten to college. Women fleeing intimate violence in home countries thousands of miles away risk sexual assault during migration only to find a perilous political and legal landscape when they seek asylum in the US. Violence against women costs billions of dollars each year, contributing to widespread poverty even as economic uncertainty makes intimate partner abuse more likely. All the while, justice remains out of reach in today’s legal systems.

This complicated picture means that each of our paths to reshaping the world must pass directly through violence against women. Whether our passion is to improve healthcare access, end school-to-prison pipelines, increase the gross domestic product (GDP), build an immigration system that respects the dignity of human beings, or create pathways to justice—all of that work requires ending and responding effectively to violence against women.

Ending violence against women, then, is in each of our self-interests, in our collective interest. Ending violence against women is the only and best way forward to create transformative change on the most pressing problems of our time.

Featured image by Michelle Ding on Unsplash, public domain

May 20, 2022

The French presidential election: Macron’s strange victory [long read]

In this series of blog posts, the historians Michael C. Behrent and Emile Chabal have teamed up with award-winning French journalist, Marion Van Renterghem to offer an in-depth look at the stakes, issues, themes, and big ideas that underpin the 2022 French electoral cycle. In the second of their three-part series on this year’s French electoral cycle, the authors look back at the results of the presidential election. Read part one here.

In this series of blog posts, the historians Michael C. Behrent and Emile Chabal have teamed up with award-winning French journalist, Marion Van Renterghem to offer an in-depth look at the stakes, issues, themes, and big ideas that underpin the 2022 French electoral cycle. In the second of their three-part series on this year’s French electoral cycle, the authors look back at the results of the presidential election. Read part one here.After the Fall of France in 1940, historian Marc Bloch famously spoke of France’s “strange defeat” by Germany. Emmanuel Macron’s victory on 24 April might just as appropriately be called a “strange victory.”

On the one hand, Macron received 58.5% of the vote in the second round, beating the far-right candidate Marine Le Pen, who received 41.5%. By any reasonable democratic standard, this is a decisive margin of victory. Furthermore, Macron managed to break a cycle of single-term presidencies, becoming the first French president since 2002 to be reelected. This is a major achievement given the depth of anti-incumbency feeling in most Western democracies.

On the other hand, France’s renewed endorsement of Macron was decidedly tepid. Le Pen significantly improved her score compared to last time: it went up by over 7% and 2.6 million votes. For a candidate who represents a party long considered beyond the democratic pale, this is an extraordinary accomplishment.

Moreover, if one considers Macron’s victory, not in terms of votes cast, but of registered voters, his score falls to 38.5%. Voter turnout was 72%, which was lower than the second-round turnout in 2017 (74.5%) or 2012 (80%). By this criterion, there is truth to the far-left candidate Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s claim that Macron is the most “poorly elected” French president since Pompidou in 1969.

Macron therefore begins his second term with a clear mandate, a broad geographical base, and a wide range of support across the centre of the political spectrum. But there is plenty for him to worry about. His anticipated reforms—particularly his plan to raise the retirement age—will elicit a strong reaction from a disillusioned left. And a new union of left-wing parties alongside the persistent challenge of the extreme-right mean that the opposition to his policies is likely to be more structured than during his first term.

Why do so many people dislike Macron?Many commentators and journalists have remarked on the fact that Macron has provoked an unusually intense amount of personal animosity. In many respects, this is surprising. Except for Chirac’s reelection in 2002, Macron’s second-round percentages in 2017 and 2022 are higher than any other winning candidate since 1965. His government is premised on an inclusive strategy, drawing figures from the centre-right and centre-left. While Macron has been chided for his arrogance and his authoritarian conception of executive power, few have questioned his competence. Indeed, he retained impressively strong approval ratings throughout his first term.

So where is this perception of “Macronophobia” coming from?

“While Macron has been chided for his arrogance … few have quested his competence. … So where is this perception of ‘Macronophobia’ coming from?”

The answer lies in a unique combination of personality and context. Were it not for Macron’s unusual background and character, and the singular moment in which he burst onto the political stage, it is unlikely that he would have provoked such hostility.

To begin with, Macron suffers as much as he benefits from his destruction of traditional party politics. For decades, the left-right spectrum gave shape to political competition in France. But its obsolescence has made it possible to incur hostility from both sides simultaneously. As a result, the left can accuse Macron of being the “president of the rich,” while the right can denounce him as a progressive globalist or internationalist.

Macron has also reactivated a new form of class politics, with all of its attendant emotions. Many French voters suspect Macron of looking down on them. This is the man who openly spoke of the difference between “people who succeed” and “people who are nothing.”

These suspicions are given credence by Macron’s economic agenda. Although his economic policies often resemble the “third way” of social-democratic leaders such as Tony Blair and Gerhard Schröder, he is strongly identified with his prior career as an investment banker and his decision, as president, to eliminate France’s wealth tax. His decision to impose a carbon tax triggered the gilet jaune revolt, in which Macron was cast as the tool of high-income and less car reliant urbanites. Combined with the now almost complete conversion of Le Pen into the candidate of France’s working-classes—polls suggest about 66% of workers voted for her this year—Macron has found himself firmly on one side of France’s polarized class politics.

Yet these structural factors are only part of the explanation for Macronophobia. To plumb its depths, one must consider the phenomenon’s political-psychological underpinnings. A key element of the antipathy to Macron can be illuminated by a theme explored in Ivan Krastev and Stephen Holmes’s recent book The Light that Failed, which examines populist politics, particularly in Eastern Europe.

Krastev and Holmes argue that support for Hungary’s Viktor Orbán and Poland’s Law and Justice Party is motivated by resentment at being compelled, for decades, to imitate foreign models—specifically, the liberal capitalist model championed by the United States and western Europe. The origins of populism, they maintain, lie “in the humiliations associated with the uphill struggle to become, at best, an inferior copy of a superior model.”

A very similar dynamic exists between Macron and many French people. Macron is superior to his peers. He is intelligent, articulate, and good-looking. He was raised in a well-off family, yet still managed to strike off on his own. He was admitted into a grande école and secured financial independence by working as an investment banker. He achieved all this at a young age—and then became France’s youngest president, at age 39.

“Anti-Macron feeling … results both from the political structures in which he operates and the sense that he expects people to copy a model that has worked for him.”

He implicitly encouraged the French to follow in his footsteps. As economics minister, he famously scolded a t-shirt wearing protestor, who happened to be unemployed, that “the best way to buy yourself a suit is to work.” Early in his first term, he appealed to the French to become a “start-up” nation. More generally, his political programme has consisted in a series of economic reforms aimed at liberalizing the French economy and proving that France can “win” at globalization.

Anti-Macron feeling, then, results both from the political structures in which he operates and the sense that he expects people to copy a model that has worked for him, even if the latter is unattainable to those who lack his qualities (and luck). He represents meritocracy’s dark side: in giving everyone the chance to succeed, it makes failure worse, because it seems personal and deserved.

Seen this way, the gilets jaunes crisis was not simply a revolt against a carbon tax, but a reaction to the holier-than-thou superiority implicit in taxing a deprecated form of transportation—the automobile—upon which many people depend. The resentment arising from the imperative of imitating, if not Macron personally, at least the model he is tied to, dovetails with the country’s new iteration of class politics.

Macron’s road to parliamentary dominanceSince 2002, legislative elections in France have been scheduled immediately after presidential elections, so that voters have an opportunity, which they have generally exercised, to give the president a majority in parliament. This is what happened in 2017, when Macron managed to translate his presidential victory into a parliamentary victory (32% for candidates aligned with the president on the first round, 49% on the second).

This feat was all the more impressive given that Macron created his party out of thin air, specifically to provide him with a parliamentary majority. Members of the traditional centre-right party, Les Républicains—at least those who did not defect to Macron—were the main opposition party, with the far-left La France Insoumise (LFI) and the far-right Rassemblement National (RN) coming in well behind.

The most likely outcome of the 12 and 19 June legislative elections is that Macron’s party—now re-baptised Renaissance—will remain the dominant force in parliament. Macron himself did relatively well in a very large number of constituencies, which provides a strong base for a parliamentary majority.

“[Macron] represents meritocracy’s dark side: in giving everyone the chance to succeed, it makes failure worse.”

The big question, however, is who—or what—will be his main opposition. After the disastrous performance of the centre-right presidential candidate, Valérie Pécresse, Les Républicains have struggled to muster up much momentum, and they remain deeply divided between those who are willing to work with Macron and those who are not. With their electorate torn between the centrism of Renaissance and the far-right politics of Éric Zemmour’s party, Reconquête, we can expect them to do poorly.

This would leave only the left, which, in contrast, has elicited a sudden rush of enthusiasm provoked by an unexpected electoral alliance between all the main parties of the left. The Nouvelle union populaire, écologique et solidaire—or NUPES—has brought together for the first time in decades the moderate Parti socialiste (PS) and the Greens (officially known as Europe-Écologie-Les Verts, or EELV), alongside LFI and the French Communist Party (PCF).

The agreement means that only one NUPES candidate will stand in each constituency, thereby concentrating the left vote. It is a strategy that has significant electoral potential, although its exact strength is difficult to estimate. If current polling is to be believed, NUPES could gain between 100-150 seats. This would be far too few to gain a majority, but it would be a major headache for Macron.

As for the RN, its prospects are more mixed. France’s first-past-the-post electoral system gives it few prospects, though the fact that Le Pen won a majority in 30 out of 101 departments in the presidential election’s second round suggests her party should get more seats than before. If the RN succeeds in getting more than 15 seats, it can form a parliamentary group. This would, at least, be a first step in transforming itself into a parliamentary force.

In short, while the parliamentary mathematics remain heavily tilted in Macron’s favour, the upcoming legislative elections have been made much more unpredictable by the left’s ability to put aside its differences and campaign on a united platform.

The exhaustion of the Fifth RepublicOne of Mélenchon’s rallying cries during the presidential campaign—and one now taken up by the new NUPES alliance—was his call for a “Sixth Republic.” The implication was that the institutions of the Fifth Republic have become so dysfunctional as to be no longer fit for purpose. This is almost certainly an exaggeration, but it is nevertheless clear that they are undergoing something of a stress-test in the current electoral cycle.

A major issue is the electoral system. In many ways, the first round of the presidential election is one of France’s best political barometers, as voters choose from a wide field of candidates, knowing that they almost certainly will not have to make a final decision until the second round. Yet a wide discrepancy exists between presidential first-round results and the relative power and influence of these political forces in democratic decision-making.

The discrepancy between first-round results and the make-up of the French National Assembly is particularly striking. Despite winning nearly 20% of the first-round vote in 2017, LFI managed to secure only seventeen députés. Similarly, despite winning 21.3% of the first-round vote—and 34% in the second round—the RN wound up with a paltry six députés. The fact that parties with real democratic legitimacy do not play a robust role in parliament explains, in part, why street protests like the gilets jaunes or frequent waves of strike action are so quick to take hold.

“[The] divergence between national and local politics has intensified the feeling of disconnection between those at the top and bottom.”

At the same time, while the Fifth Republic was always intended to be a presidential system, it seems to be becoming even more so. Macron’s preference for “vertical” decision-making, and the fact that parliamentary elections immediately follow presidential elections means that there is little in the way of contested politics. The National Assembly is seen to be a mere rubber-stamping mechanism for the president. This tendency has only been exacerbated by the emergence of parties-for-candidates, which have little independent structure or purpose beyond supporting a presidential candidate. While voters were more forgiving of “vertical” politics when the Fifth Republic was established in the late 1950s, they find it much harder today to tolerate what is regarded as an overtly authoritarian approach to governing.

These multiple problems are evident in the radical detachment between national and local politics. None of the four top candidates in the 2022 presidential elections can claim any real local power base. The RN and Reconquête have virtually no representation at the local level; LFI has done a little better, while Macron’s party dominates parliament but holds no French regions and few municipalities. Instead, local politics remains dominated by the main centre-right and centre-left parties, both of whose candidates were thoroughly beaten in the presidential election.

This divergence between national and local politics has intensified the feeling of disconnection between those at the top and bottom. While no major Western democracy has solved the problem of how to create a representative system that can capture the complexity of contemporary societies, the French Fifth Republic no longer seems able to cope with the political processes to which it gave birth.

The politics of divisive centrismIn our first instalment in this blog series, we said that this presidential election cycle was unusual in that the result was a foregone conclusion. There was a moment when it looked as if an upset might be on the cards—especially with Mélenchon’s strong performance, which came within a hair’s breadth of consigning Le Pen to the first round—but our analysis turned out to be correct. This was a predictable election that gave a predictable result.

“The paradox of Macron’s politics is that, by … transcending the left-right divide … he has made French politics more unstable rather than less.”

And yet there is a strong sense that France is, more than after any other recent presidential election, on edge. This may simply be a consequence of economic anxiety, international uncertainty, and distrust stemming from the pandemic. But it may also suggest a more fundamental dislocation of political and social life. The paradox of Macron’s politics is that, by achieving his goal of transcending the left-right divide and creating a broad centrist movement, he has made French politics more unstable rather than less. His presidency has created more opportunities for extremist contestation, and it has entrenched many citizens’ feelings of being alienated from the political elite.

This should serve as a warning. After all, even modern France’s greatest president, Charles de Gaulle, faced sustained opposition by the end of his reign, which culminated in the nationwide protests of May 1968. Could Macron’s second term presage something similar?

Featured image by Jacques Paquier via Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

May 19, 2022

Beyond the Anna Karenina principle in economic development

The opening sentence of Tolstoy’s novel Anna Karenina–All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way–is popular among development practitioners, who often offer their own version as follows: All rich economies are alike; each poor economy is poor in its own way. This idea, which we can call the Anna Karenina principle of economic development, is meant as a recognition of the value of context and local knowledge.

And it is not only practitioners that share this well-intentioned sentiment. A long-standing literature on development has usefully alerted us to the dangers of simply copying institutional best practices from developed countries, or “isomorphic mimicry” to use the term originally from evolutionary biology that has caught on in the development literature.

But, oversimplified as in the Anna Karenina principle, it has an unintended consequence. In short, what’s wrong with it is not the punchline but its setup. Thinking all rich economies are institutionally alike is simply misguided. (In jest, it could be described as a case of “idiomorphic myopia,” or the inability to clearly see different institutional forms.) But why does this matter?

If all rich economies are seen as institutionally alike, one would want to draw inspiration from only the most successful country, or a few at most. This helps to explain, for example, the prominent role that South Korea plays in the collective imagination of development practitioners. A “winner takes all attention” disposition makes slightly less successful country cases much less studied and used in development circles. And this means that the focus is put squarely on a relatively narrow slice of the experience of successful development.

Somewhat less successful cases may not even be seen as successes to begin with. To give an example from personal experience, when sharing that I was writing about Spain’s rise to high-income status, my interlocutors would often concede that Spain was an interesting case study but that, surely, I meant to say that I was writing about economic failure not success. This about a country, Spain, that is among a handful to have graduated into high-income status in recent decades and that in 30 years had been able to catch up 30 percentage points as a share of per capita output with that of the United States.

In the view of the world captured by the Anna Karenina principle, the economic history of rich countries is of little interest. Strictly speaking, the belief that all rich economies are alike does not necessarily imply the belief that their path to their current high-income status must have been similar. But in practice these two beliefs often go together. And when they do, they imply a loss that stems from overlooking a rich set of experiences that often look little like stylized institutional trajectories. Just like with biodiversity, there is much value in understanding how specific successful adaptations work in the development space. Not seeing that rich countries got to where they are through different paths is a missed opportunity to learn from truly diverse experiences.

Why is this important? In no small part because the successful adaptations of others can provide a springboard for one’s own adaptations. The dilemma of design in development projects, as Albert Hirschman put it, is balancing between elements of the status quo that have to be taken as unchangeable and those elements of the status quo to be disrupted. Escaping this dilemma is the art of project design and, as Hirschman noted, the fate of a project becomes a wager about getting that balance right. In doing so local context and knowledge can only go so far in informing what elements to disrupt because, by definition, some elements of the status quo are to be disrupted. Hence the value of looking to how numerous other countries addressed related challenges. Often a development challenge that a country faces has been solved by another country but on a different domain.

Taking solutions from one domain and applying them to another is a fruitful methodology, common for example in design thinking. In brainstorming techniques, the quantity of ideas generated really matters for the quality of the solutions created, not because it helps in the search of stylized facts or common features, but because it helps avoid functional fixedness and brings about more creative solutions.

Not only are all rich economies not alike but their paths to how they got there may prove to be full of insights. To return to Anna Karenina, it may not be its first sentence but its very last one, uttered by Tolstoy’s own alter-ego Levin, that may be more relevant after all: “my whole life… is not only not meaningless… but has the unquestionable meaning of the good which is in my power to put into it!”

Featured image by Didier Weemaels on Unsplash (public domain)

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers