Oxford University Press's Blog, page 72

August 12, 2022

Why Waterloo? How the Battle of Waterloo took its place in Britain’s national identity

When the House of Commons began discussing a national monument to the Battle of Waterloo in January 1816, they were forced to debate an issue that still concerns politicians, activists, and scholars today—how does a country choose what to commemorate? What elevated the victory of 18 June 1815 over other great British victories in the previous quarter century of war? What about Trafalgar, Salamanca, or Vittoria? Or indeed a monument to the war as a whole, as the architect Benjamin Dean Wyatt and MP George Tierney both suggested? Put simply, why Waterloo?

Outside the Palace of Westminster, however, there was no hesitation or discussion. The people decided, imprinting on Waterloo as their victory. Other battles and their participants were commemorated in select locations, but Waterloo immediately assumed a position of primacy in British life that it would enjoy for nearly half a century. Bridges, streets, businesses, vegetables, and even shades of blue were named for the battle; theatrical and open-air re-enactments, panoramas, models, and paintings all drew huge crowds; narratives, memoirs, prints, and other commemorative merchandise flew off the shelves; and 18 June became an unofficial national holiday, marked by dinners, balls, fairs, fetes, and openings all over Britain and increasingly throughout the Commonwealth as the years went on.

Well, why Waterloo? What combination of factors elevated British commemoration of Waterloo above all the other engagements that made up the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars? I believe above all else neatness, timing, and the fundamental shifts occurring in British society and national image in the first half of the nineteenth century.

“What elevated the victory of 18 June 1815 over other great British victories in the previous quarter century of war?”

Let us start with neatness. As a baseline, the British won. Waterloo could have been purposely designed by a focus group as a perfect grand finale to long years of war. Three of the great military leaders of the age—Prince Blücher (whose efforts, within days, were already being downplayed by certain Britons), the Duke of Wellington, and Napoleon Bonaparte—met in a decisive battle in a relatively small valley not a very long way from the Sceptered Isle itself. Waterloo was, in almost every way, contained and concentrated. Wellington’s army had covered itself in glory in the Iberian Peninsula, but the Iron Duke had never faced Napoleon himself, lessening those victories in some eyes. At Waterloo Wellington and Napoleon finally met, and it was the man that many were already transforming into the living avatar of Britain’s military glory that emerged victorious.

Next let us turn to timing, crucial for three different reasons. First, Waterloo benefited from being the last major British battle for several decades (in the European context until Navarino in 1827 or the Crimean War in the 1850s). It had time to sink into the nation’s consciousness without being supplanted. All previous British victories in the Napoleonic Wars had been celebrated in great style, but they had always been supplanted by the “next big thing”—Ciudad Rodrigo had given way to Badajoz, Badajoz to Salamanca, and Salamanca in turn to Vittoria. There was no “next big thing” in a military context after Waterloo, so it remained the “big thing” for decades. Second, it is important to note that the last major British battle before Waterloo was not Toulouse, which, although anticlimactic, was a victory, but New Orleans, where an outnumbered American force largely made up of militia and volunteer regiments decisively defeated a British expedition that included multiple regiments that had served with distinction in Wellington’s Peninsular Army. Waterloo was seized on as a golden opportunity to wipe the bad taste of New Orleans and its roughly 2,000 casualties (to the Americans’ 71) from the national consciousness, and every effort made to elevate Waterloo diminished New Orleans. Thirdly, there is the timing of the battle within the calendar itself. While the fact that 18 June is only days away from the summer solstice served to extend the battle until late in the evening, it also meant that the anniversary of the battle was ideally timed for outdoor commemorative events which could take advantage of usually good weather and that same extended light.

“Great Britain had built its secular national identity largely on an antagonistic relationship with France — its great enemy militarily, economically, gastronomically. Then it won.”

Finally, we come to Waterloo’s place in the shifting national identity of Great Britain. For arguably a century before Waterloo, Great Britain had built its secular national identity largely on an antagonistic relationship with France—its great enemy militarily, economically, gastronomically. Then it won. While this placed Britain in an unrivaled position as one of the great powers of Europe (if not the great power of the nineteenth century), winning also left a gap. How to define Britishness if not in opposition to Frenchness, when France was no longer the threat? Waterloo helped fill that gap as Britain underwent the shift from its Georgian and Regency identity to its Victorian one, and in its commemoration, we see the seeds of Victorian culture: spectacle, tourism, domesticity, imperial expansionism, and new forms of both consumerism and propaganda.

Waterloo’s ascendancy as the celebration—immediately, and consistently into the 1850s—happened organically in a population eager for victory and eager to define what Britishness meant on its own terms. Having become a crucial part of Great Britain’s creation myth, Waterloo was distilled into the perfect moment to encapsulate British military triumph and wider British ascendency, simultaneously anchoring Britain to its past while justifying its present and shaping its future.

Parliament never did erect a monument to Waterloo.

Featured image: “The wars of Wellington, a narrative poem” by William Heath, from the British Library via Flickr, public domain.

August 11, 2022

What does UK law say about strikes?

In this blog series, Astra Emir, practising barrister and author of Selwyn’s Law of Employment, explains what UK employment law says about some of the important issues faced by employers and employees.

In this blog series, Astra Emir, practising barrister and author of Selwyn’s Law of Employment, explains what UK employment law says about some of the important issues faced by employers and employees.Every day there are reports of further strikes. Chaos on the railways, the London Underground brought to a standstill, airlines, teachers, the NHS: the list goes on. On one hand, people are fighting for their rights, some would say justifiably. On the other, employers are trying to keep things running. While strikes cause huge disruption for the public, they are also one of the few levers available to employees to bargain for their position.

This blog post looks at what the main rights and requirements are, both for employers and employees, once a strike has been called.

The sheer number of strikes being planned have led to concerns that we may go back to the days of the “winter of discontent” in the 1970s. It is important however to note that the legal landscape is now very different. Since then, not only has overall membership of the unions declined drastically, but there have also been a number of changes brought in by various Conservative governments, the latest being the Trade Union Act 2016. This tightened the balloting requirements so that there now has to be at least a 50% turnout of the union membership for a vote on whether industrial action should take place and, for key public services, at least 40% of those eligible need to vote in favour of a strike. Indeed when the Trade Union Act was passed, there were fears that it would become extremely difficult to hold a strike in future. Clearly the current cost of living crisis has overcome these considerable hurdles and led for the ballots to be successful, and so we are facing more strikes than there have been for many years.

Protection of employeesIn order for employees to be protected, they have to be taking part in official industrial action. This means that it has to be called by a recognised, independent trade union, the action has to be “in furtherance of a trade dispute,” and the balloting and other procedural requirements have to be within the rules set out in the legislation.

“In order for employees to be protected, they have to be taking part in official industrial action.”

The employee does not have the right to be paid for any days they are on strike (unless their contract says otherwise), but the job will be protected. If an employer dismisses them for taking part in the official industrial action then this would be an automatically unfair dismissal, which means that the person does not have to have been employed for two years before bringing a claim, unlike most other unfair dismissal cases. (Note that a strike does not break continuity, but the time on strike does not count towards computing the time that someone has been employed.)

Indeed, the employee will be protected, not just for taking part in a strike, but against a detriment for any official industrial action, such as overtime bans or a work to rule, for 12 weeks from the date at which industrial action (of whatever kind) began.

After 12 weeks, the dismissal of those taking official action becomes potentially fair, provided the employer acts reasonably and consistently, treating all employees alike. In addition, the Employment Relations Act 1999 requires an employer to show that it took “all reasonable steps” to resolve the dispute if it wants its action in dismissing the employees concerned to be judged as reasonable.

The protection also applies to non-union members who take part in a strike.

PicketingOne issue that often arises is that of picketing. The law says that striking employees are permitted to picket peacefully at or near their own place of work, as are the trade union officials who represent them. This can only be for the purpose of “peacefully obtaining or communicating information, or peacefully persuading any person to work or to abstain from working.” Any other activity is not protected. If someone wants to cross the picket line, then they must be allowed to do so. Every picket line has to have a readily identifiable picket supervisor, wearing an armband or tabard, who must carry a letter stating that the picketing is approved by the union. “Flying pickets,” where employees of another employer come to join the picket line, are not permitted.

“The law says that striking employees are permitted to picket peacefully at or near their own place of work.”

There is also a Code of Practice on Picketing, which suggests a maximum of six people per picket line. The Code is not legally enforceable but can be taken into account in legal proceedings.

If the rules relating to picketing are not observed, for example when the picketing ceases to be peaceful (i.e., goes beyond communicating a message and seeking to persuade in a peaceful fashion) the immunity is lost, and the employer can apply for an interlocutory injunction to stop the strike from continuing. (Note that they can also apply for an injunction, for example, if the balloting requirements in the legislation have not been properly met, or if the strike is unofficial for another reason.)

Rights and duties of employersApart from applying for injunctions, which are only available in limited circumstances, there are a number of other things employers can do to keep their services running. They can outsource to a third party, and there is nothing to stop the employer using workers from another part of the business, if those people have the relevant skills and their employment contract allows them to be redeployed in that way.

Until recently, the law prevented an employment agency from providing an agency worker to cover for the striking worker. This was a criminal offence on the part of the agency and subject to an unlimited fine.

On 21 July 2022, however, new regulations came into force to repeal the prohibition on employment agencies providing staff to cover for striking workers, which means that an employer can now hire agency workers to fill the gaps.

New legislationThis legislation was the subject of a consultation and had been expected to be part of the Trade Union Act 2016, but it did not happen at the time. With the uptick in the number of strikes recently, it then became a priority for the Government.

“On 21 July 2022, new regulations came into force to repeal the prohibition on employment agencies providing staff to cover for striking workers.”

There are a number of issues with the new legislation, however. Not only does it undermine the bargaining position of the unions and striking workers, and indeed the point of having a strike in the first place, but also, according to Neil Carberry, chief executive of the Recruitment & Employment Confederation (REC), it puts agency workers and agencies in an invidious position if they have to cross picket lines.

More practically, it may be questioned whether the proposed legislation will make much difference. It might in some industries, e.g. nursing or perhaps teaching, where there is a strong culture of using agency workers for cover, but it is likely that it will be more difficult to replace train drivers and skilled airline staff at short notice.

In addition, if an employer does choose to go down this route, it is extremely likely to lead to bad industrial relations and the escalation of the strike action, which would defeat the purpose of the legislation. It remains to be seen what the outcome will be.

Please note that this an overview of the law and is not intended to be legal advice, as each case depends on its own specific facts.

Feature image by Kate Asplin on Unsplash , public domain

August 10, 2022

The human aspect of etymology

Like several other posts in this blog, this one has been inspired by a letter from a reader. I am not sure that I have enough comments and questions for a full-scale set of gleanings, but more than enough can be said in answer to the question: “Why do so many words beginning with sn– evoke unpleasant associations?” Such are snide, snicker, and even snake, though snack, snow, and snipe are neutral, as far as emotions are concerned.

In discussing the origin of English words, I often refer to two concepts: sound imitation (or its learned synonym onomatopoeia) and sound symbolism. Sound imitation poses relatively few problems, and the most common examples in this area are words purporting to reproduce animal cries and all kinds of noises. Yet even here, some cases give trouble to etymologists. When cats meow, people hear more or less the same sounds all over the world; hence miau and its likes. Cows’ moo is also universal. But no combinations of human vowels and consonants match the dog’s bark. The verbs bark, growl, and yelp, along with such onomatopoeias as woof and bow-wow (compare Russian gav–gav and tiaf-tiaf) imitate the noises made by dogs most imperfectly. Exclamation like ouch and oops also pretend to be sound-imitative but hardly reproduce anything we really say in pain and in frustration; we rather learn that such genteel verbal reactions are expected of us. The same holds for oh and ah. Be that as it may, in several spheres, sound imitation is a transparent concept, and let English pigs and donkeys “say” oink-oink and hee-haw and Russian horses “say” igogo (stress on the last syllable). Our withers are unwrung, as Hamlet put it.

Less obvious are verbs like creak, cry, crush, and crash. The group kr– does imitate the noises we hear when something crushes and crashes, and perhaps cry belongs here. A similar conclusion can be reached about grind, grumble, groan, and growl. However, a language historian must also explain where the sounds following kr and gr came from, and the same holds for the verb break: br– seems to owe its origin to sound imitation, but what about the end of the verb? The old posts on English trash and rubbish (24 March 2021 and 31 March 2021) are partly devoted to this difficulty.

Our withers are unwrung.

Our withers are unwrung.(Photo by European Mobility Week, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

The idea of sound symbolism is correct but evasive. Taken in separation, vowels and consonants do not “mean” anything, but when they become parts of words, they do not always remain “neutral.” Take such compounds as shillyshally, dillydally, fiddle-faddle, pitter-patter, trictrac, and flimflam. The progress is always from short i to short a, because we associate the vowel i with small-sized objects and short a with something big. Indeed, when we pronounce short i, the mouth is almost closed, and for short a we open it wide. Even the existence of the adjective big, with its “counterintuitive” vowel, cannot ruin this “law.” The process of growth refers to small things increasing their size. The structure of pitter-patter and its likes imitates this process.

Sometimes it is hard to separate sound imitation from sound symbolism. Not long ago (15 December 2021 and 5 January 2022), I devoted two posts to the words star and spark. The groups st(r)- and sp(r)- are, in a way, sound-imitative, because they remind us of spraying, sputtering, and strewing, but once they acquire this status, they begin to live a life of their own, and we tend to associate every word beginning with spr- ~ str- with strewing and the like. That is why I sometimes write in my blog posts: “sound-imitative or sound-symbolic.” We observe an even more enigmatic situation when we approach the much-discussed group fl-. For some mysterious reason, this group suggests to many people the idea of flowing and unsteadiness. Hence not only flow but also flutter and flatter, flicker and flimsy. According to the well-known law (The First Consonant Shift), Germanic fl– should correspond to non-Germanic pl-, and indeed, we find Latin pluere “to rain.” However, the Latin for “flow” is not pluere but fluere! (Hence English fluid and the rest.) No one is in a hurry to call the Germanic or the Latin verb a borrowing, and it is instructive to observe how much has been written about the symbolic (or sound-imitative?) role of the group fl. An etymologist should think twice before ascribing the origin of a certain word to sound symbolism, because the concept is vague and easy to put to use (or abuse) when all other arguments fail. Yet it exists and plays a noticeable role in the coining of words all over the world. It is unclear whether certain groups of vowels and consonants arouse the same emotions in all human beings or whether some or most of them are language-specific. Sound imitation is easier to deal with. The Austrian researcher Wilhelm Oehl defended the panhuman appeal of many groups.

A real, rather than symbolic, flood.

A real, rather than symbolic, flood.(Photo by Maxwell Hamilton, via Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

This brings us to the unsafe area of sn– and sl-. There is no doubt that sl– often brings forth negative feelings in English (and in most of Germanic) speakers. When we learn the meaning of slim, slight, sleazy, slattern, and quite a few others, we experience a feeling akin to satisfaction: the words, we conclude, mean what they should. But the association may be secondary. This is probably the case with sn-words, of which there are not too many. Snot, sneeze, sniff, snuff, snivel, and snore seem to be partly sound-imitative. In very many languages, words connected with the nose begin with the consonant n, like the word nose itself. But surely, snob, snub, snide, let alone snake and snarl, simply found themselves in bad company. This is guilt by association.

It is curious to observe how helpless etymologists are when they deal with sound-symbolic words. In this sphere, nothing can be proved. For example, very many English words beginning with j have very questionable antecedents. Here is a short list of j-words about which dictionaries say “origin unknown” or make do with the phrase “of symbolic origin”: jog (it used to alternate with jag and jug), jape “to copulate,” jaunt, jeer, jib, jiffy, jilt, jinx, job (!), junk, jerk, jumble, and even jump. Perhaps there is nothing to say about them, that is, no “serious” etymology of those words exist. They are like weeds on the rich garbage of human creativity.

Overwhelmed by the volume of letters to the Oxford Etymologist.

Overwhelmed by the volume of letters to the Oxford Etymologist.(Photo by Henry Lawford, via Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

It remains for me to say, that for “sound-imitative” James A. H. Murray, the first editor of The Oxford English Dictionary (OED), coined the term echoic. A study of echoic and sound-symbolic words has become a serious and fruitful branch of linguistics. The term iconic has been applied to the words that suggest their meaning, and the branch of linguistics that deals with iconic words deals with so-called iconicity. Students of iconicity have formed a society and meet for regular congresses. Quite a few books and very many papers deal with iconic words. The fortune of iconic words is no longer a stepdaughter of linguistics. Explaining them is slow work, but nothing of importance is done in a jiffy.

The moral of this post is: if you have questions, send me letters.

Featured image from PxHere, public domain

August 9, 2022

Comparing Woolf’s Jacob’s Room and Beethoven’s Third

Jacob’s Room begins with a mystery: “‘So of course,’ wrote Betty Flanders, pressing her heels rather deeper in the sand, ‘there was nothing for it but to leave’.” Why does Betty Flanders (with her ominous surname) have to leave? Why “of course”? We never find out. It is a beginning that announces an end, a departure imposed rather than chosen. And it heralds a story built on the hollow promises of a young man’s coming-of-age: promises integral to the nineteenth century’s massive array of social realist fiction, those novels by Dickens, Thackeray, and the Brontës that contained templates for molding men who would uphold the finest qualities of the British Empire. But Jacob’s Room holds such templates up to the pitiless gaze of history and resists their plot-making powers. Written in the wake of the Great War that slaughtered 1 million Englishmen, Woolf’s anti-Bildungsroman suggested that the very virtues the Empire prided itself on—valor, stoicism, duty—were the sources of its vulnerability. How does the formal originality of Jacob’s Room, its dark tenor, fit into the arc of Woolf’s career? And a century after its publication in 1922, what does it tell us about English literature’s annus mirabilis, the year that gave us Joyce’s Ulysses, Eliot’s The Waste Land, and Mansfield’s The Garden Party and Other Stories?

I found unexpected and illuminating answers to these questions when after days of studying Woolf’s drafts and preparatory notes for the novel in the Berg Collection of the New York Public Library, I treated myself to symphony tickets, thrilled by the prospect of hearing live music after the pandemic. It was a privilege to hear Yannick Nézet-Séguin conduct the Philadelphia Orchestra in an all-Beethoven concert at Carnegie Hall. And when he turned to address the audience, explaining how Beethoven’s sense of musical possibility changed between Symphony 2 and Symphony 3—the “Eroica”—I suddenly understood how to read the marriage of aesthetics and history in Jacob’s Room.

Separated by sex, nation, professional training, and the span of a century, Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) and Virginia Woolf (1882-1941) would seem to have little in common. But their similarities are intriguing. The German composer and the English writer lived through cataclysmic periods of history, inventing ever-more daring forms of art to oppose the tyrannies that precipitated the French Revolution and the Great War. They struggled with debilitating conditions—his deafness and her mental illness—that threatened to be fatal to creativity. These debilities contributed to suicidal impulses that visited each artist at the age of 31. Beethoven and Woolf both died before turning 60, leaving behind large, diverse oeuvres anchored by nine major works, and it is in the developmental parallels of these major works that we can locate Jacob’s Room’s significance. The first two works of the nine belong to the traditions that preceded them: the Classical symmetries of Beethoven’s first and second symphonies suggest that he had, as his patron Count Waldstein said, “receive[d] Mozart’s spirit from Haydn’s hands”; and the narrative conventions of Woolf’s novels The Voyage Out and Night and Day descend from Austen and Dickens. Their fifth works would be their most beloved: the first four notes of Beethoven’s Symphony 5 have imprinted themselves in musical consciousness just as the lyrical beauty of Woolf’s To the Lighthouse has infused the literary firmament. And Beethoven’s 9th symphony, its final movement opening with a dissonance that Wagner would call the “terror fanfare” and closing, radically, with a choir singing Schiller’s “Ode to Joy,” finds numerous affinities not with Woolf’s ninth novel The Years but with her last, genre-collapsing work, Between the Acts, which merges narrative, poetry, and drama to find strength through art on the terrifying eve of the second World War.

“Woolf’s third work joins Beethoven’s not only in rejecting the predictable modes of an earlier artistic form, but in remaking the idea of heroism.”

From these similarities, which merit greater attention than I can give here, I return to how Beethoven’s and Woolf’s third works announced their emergence into a new artistic phase. How does the “Eroica” illuminate Jacob’s Room? Beethoven’s third symphony—expansive, explosive, baffling to listeners—marked a turning-point not only in the composer’s career but also for symphonic music more generally. The first movement begins with swift, doubled tonic chords played in unison followed by a lilting melody in the cellos that is interrupted by unexpected dissonance. Beethoven catches his 1804 audience off guard, combining melodic urgency with bold, accelerating rhythms when listeners would have expected smooth development and recapitulation. It is precisely what Woolf does to narrative expectations in Jacob’s Room, whose opening, as we have seen, presents an unanswered question. Woolf’s novel courts the promises of the Bildungsroman and the Kunstlerroman, moving Jacob Flanders through Cambridge University, a job in London, a grand tour of Europe, and multiple artistic efforts: but Jacob thwarts our assumptions, becoming less knowable and less effective until the Great War swallows him. Thus, Woolf’s third work joins Beethoven’s not only in rejecting the predictable modes of an earlier artistic form, but in remaking the idea of heroism.

Beethoven originally dedicated his third symphony to Napoleon Bonaparte as a tribute to the latter’s anti-monarchical ideals but, in what is the stuff of musical legend, Beethoven was so enraged when Bonaparte made himself Emperor of France that he tore the symphony’s title page—with its inscription “Bonaparte”—down the middle. The piece was retitled Sinfonia Eroica, or “heroic symphony,” in 1806. Woolf’s journey in writing Jacob’s Room was not as dramatic, but it also unmade the historical figures of kings, emperors, and prime ministers, and its loose-jointed plot critiqued self-serving acts of power styled as greatness. Like Beethoven, Woolf had initially considered dedicating her work to a specific individual. She drafted an epigraph for her older brother, Thoby Stephen, who had died of typhoid at age 26, that contained a repeated line from the Roman poet Catullus:

Atque in perpetuum, frater, ave atque vale.

Julian Thoby Stephen (1881-1906)

Atque in perpetuum, frater, ave atque vale

Woolf may not have torn up her dedication, but she eventually decided against including it in Jacob’s Room, a work that treats heroism as a troubled abstraction rather than lauding it as a quality embodied in one character. The novel’s chapters are crowded with motifs and metaphors of the fast-approaching Great War, very much like the repetitive, fugal funeral march in the second movement of the “Eroica,” which Beethoven breaks into barely recognizable fragments by the movement’s end. But whereas Beethoven’s symphony ultimately offered a Romantic celebration of the human spirit, Woolf took a more somber direction, her novel’s narrator pronouncing, “All history backs our pane of glass. To escape is vain…It is no use trying to sum people up.”

As Yannick Nézet-Séguin began conducting the “Eroica” and the hall filled with the intricate sonorities of what was once unimaginable musical terrain, I was reminded that Woolf considered Jacob’s Room the novel where she found her artistic self. “There’s no doubt in my mind,” she penned in her diary on completing the novel, “that I have found out how to begin (at 40) to say something in my own voice.” That voice brought a new note to the revolutionary literature of 1922, an anti-transcendent dissonance distinct from the hopefulness coursing through the writings of Mansfield, Eliot, and Joyce. It was a dissonance that opened rather than shut down literary possibilities and signaled the creative momentum behind works that were stirring to life even before Jacob’s Room was published: Mrs. Dalloway, To the Lighthouse, The Common Reader. What Beethoven wrote about his artistic energies while he composed his third symphony equally describes Woolf as she wrote her third novel: “I live only in my notes, and with one work barely finished, the other is already started; the way I write now I often find myself working on three, four things at the same time.”

Featured image by Sigmund on Unsplash, public domain

August 7, 2022

Wedding: how did Shakespeare become a London playwright?

In this OUPblog series, Lena Cowen Orlin, author of the “detailed and dazzling” The Private Life of William Shakespeare, explores key moments in the Bard’s life. From asking just when was Shakespeare’s birthday, to his bequest of a “second-best bed,” to his own funerary monument, you can read the complete series here.How did Stratford’s Shakespeare become a London playwright?

In this OUPblog series, Lena Cowen Orlin, author of the “detailed and dazzling” The Private Life of William Shakespeare, explores key moments in the Bard’s life. From asking just when was Shakespeare’s birthday, to his bequest of a “second-best bed,” to his own funerary monument, you can read the complete series here.How did Stratford’s Shakespeare become a London playwright?Shakespeare’s first biographer, Nicholas Rowe, wrote in 1709 that the author married “while he was yet very young.” He then fell in with a bad crowd that “made a frequent practice of deer-stealing” from Warwickshire magnate Sir Thomas Lucy. Lucy prosecuted Shakespeare so vigorously that he “was obliged to leave . . . and shelter himself in London.” Rowe concluded: “though it seemed at first to be a blemish upon his good manners, and a misfortune to him, yet it afterwards happily proved the occasion of exerting one of the greatest geniuses that ever was known in dramatic poetry.”

The only surviving image that may depict Anne Hathaway is a portrait line-drawing made by Sir Nathaniel Curzon in 1708, referred to as “Shakespear’s Consort”.

The only surviving image that may depict Anne Hathaway is a portrait line-drawing made by Sir Nathaniel Curzon in 1708, referred to as “Shakespear’s Consort”.(Via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Indeed, as the Stratford-upon-Avon parish register confirms, Shakespeare was just 18 and still a minor when he wed in 1582. From there, though, confirming evidence was scarce for an account probably based in dubious oral history. The editor Edmond Malone, who searched archives in Stratford and elsewhere, did not believe the local legend. He and others assembled documents out of which they built a different narrative about Shakespeare’s migration to London. His wife was eight years older than he; she was pregnant when they married; the couple secured a special wedding license from the Bishop of Worcester. To nineteenth-century biographers, it looked as if a mature and predatory woman had sexually entrapped a naïve young man, dragging him to the altar for a shameful shotgun wedding. They quoted Orsino in Twelfth Night—“Let still the woman take / An elder than herself”—and referred to Venus and Adonis. The will in which Shakespeare left his wife nothing more than his “second-best bed” put the punctuation mark on this new theory for why he left Stratford: he was fleeing a wife whom he despised from beginning to end.

In fact, as the quantitative analysis of wedding and baptismal records reveals, up to a third of late-sixteenth-century brides were pregnant when they married. Pregnancy was often the signal to a committed couple that the time had come for them to cease living as wage earners and establish their own household and, so long as the liaison led to marriage, no disgrace attached. In contemporary courts, women were charged and shamed for sleeping with men to whom they were not married. They were never censured or slandered for having slept with their own husbands (even prematurely). As for the will, Malone was wrong to assert that the bed cut off Shakespeare’s wife. The family’s acquisitions of property were due in no small part to Anne Hathaway’s own contributions through their working partnership, and the law protected her property rights during her widowhood. Shakespeare died in Stratford, which, through all the London years, he always regarded as home.

The traditional accounts of his first journey to London depict him as a victim of his own ill-considered adolescent behaviour. He made himself susceptible to coercion, whether by Sir Thomas Lucy or by Anne Hathaway, and he ran away. But there is a new way of looking at this origin story: he elected not to follow in the footsteps of his father.

“Traditional accounts . . . depict [Shakespeare] as a victim of his own ill-considered adolescent behaviour. . . . But there is a [new] way of looking at this origin story.”

John Shakespeare was born into a family of tenant farmers. He achieved a crafts apprenticeship in the nearest market town, where he became so successful as a leather worker and glove maker that he branched out into wool wholesaling, moneylending, and civic leadership. He was already a town alderman when Shakespeare was born in 1564. When Shakespeare was four, his father was named bailiff, Stratford’s highest office. By the time Shakespeare was 13, however, his father’s business had failed and John Shakespeare was forced into “hiding” to evade his creditors. He was sued repeatedly, was probably gaoled, and ceased attending meetings of the town council.

Shakespeare, meanwhile, was on the same life path. Living in a market town, he was scheduled to be apprenticed at age 17 in a mercantile craft. Local lore had it that he was placed with a butcher. But Shakespeare’s apprenticeship indenture is lost, so we must look to other examples to learn that he would have trained for seven years, until he was 24. Surviving indentures also routinely spelled out that the apprentice had to be obedient to his master. He had to protect his master’s possessions. In addition, “fornication he shall not commit; matrimony he shall not contract.”

If Shakespeare wanted to break the terms of his indenture at age 18, a creative way of doing so was to give evidence of fornication and to oblige himself to wed. Anne Hathaway’s pregnancy and the early marriage were the keys to his becoming an actor and writer rather than, say, a butcher. To my mind, Shakespeare’s is a story of intentionality, with London as the aim rather than a hapless accident.

Featured image: Shakespeare’s family circle via Wikimedia Commons, public domain

August 3, 2022

The loudest short word in English: hurrah

There was a twelfth-century author called Wace, whom the king commissioned to write a chronicle of the Norman conquest. In it Raoul Tesson shouts: “Tur aie,” apparently, meaning “Thor’s aide.” “Surely this is the origin of our modern hurrah; and if so, perhaps the earliest mention of our English war-cry.” This was the opinion of someone who signed his name with the initials J. F. M. in a letter printed in Notes and Queries on June 25, 1853. Surely…. Contributors to nineteenth-century popular periodicals knew incredibly much: they read medieval chronicles in the original, quoted Homer and Latin authors, remembered psalms in Hebrew, and never forgot what they had learned, but their derivation of words was haphazard.

At that time, etymology in the English-speaking world was still an exercise in guesswork, and few people realized that a complete story of word origins should answer the following questions: 1) When (according to our information) did the word appear in the language? 2) What did it mean at that time? 3) If it is a borrowing, why and when was it taken over? The history of hurrah is full of puzzling moments, but I needn’t discuss them in detail, because in 1940 John A. Walz, a Harvard professor of German, once very well-known for his contributions, brought out a paper (42 pages long) on the history of this exclamation (The Journal of English and Germanic Philology 39, 1940, 33-75). Yet, though his survey is excellent, it seems to contain a flaw in need of our attention.

Hurrah surfaced in English texts at the end of the eighteenth century. It was preceded by huzza, and the origin of huzza has been explained quite convincingly as a sailor’s cheer of salute. The word may be identical with the old hauling-cry heissau ~ hissa, related to hoist (a verb of Dutch origin). The problem is that German has hussa (with voiceless ss), which has nothing to do with sailors: it is a cry of pursuit and exultation. A war cry, reminiscent of the sixteenth century hue and cry, used in the pursuit of a felon (the verb huer is, quite probably, of imitative origin)? Or hunters’ cry like English ataboy? We’ll return to hue and cry later.

“I am a lone, lorn creatur’.”

“I am a lone, lorn creatur’.”(“Mr Peggotty, Ham, and Mrs Gummidge” by

Sol Eytinge. Scanned image by Philip V. Allingham, via The Victorian Web, public domain.)

Two main questions haunt the student of hurrah. How is hurrah connected (if at all) with its synonym huzza? And how is it connected with Russian ura (a, as in English ah; stress on the second syllable), a cry of triumph, popular in both war and peace. Walz, a distinguished humanities scholar, but not a linguist, argued that in huzza, which predates hurrah, z developed to r “through rhotacism.” This is a baffling statement. The term rhotacism refers to any consonant becoming r. In the history of the Germanic languages, the best-known and the only important rhotacism happened long before the appearance of the first written monuments, when z changed to r.

The traces of this early change are not too hard to observe even today: wasversus were, lose versus (for)lorn (Mrs Gummidge in David Copperfield called herself a lone, lorn creatur’), and so forth. In Latin, the alternation Venus ~ (genitive) Veneris is due to rhotacism. The history of language shows that almost any consonant may become r. For instance, in dialectal British English pronunciation, pottage (which we remember almost only from the Biblical phrase a mess of pottage) was pronounced with very weak t, and the result is the universally known word porridge. One can find many similar examples. But Walz’s scenario is unrealistic: allegedly, hussa, through the weakening of s (rhotacism), gradually turned into hurrah. Without at least some reference to the dialect of the people in whose speech such rhotacism occurred, this reconstruction does not carry conviction. We should probably agree that hussa and hurrah are different words, even if, as time went on, they got into each other’s way.

In the research of hurrah, there was a seeming breakthrough many years ago. Medieval German poetry has come down to us quite well. In that language, known as Middle High German, the particle long a (pronounced as English ah) was often added to verbs and nouns for emphasis. Once, the verb hurren “to hurry” occurred with this enclitic (“hurry, hurry!”), and as early as 1866, Hendrik Kern, an eminent Dutch philologist, traced hurrah to it. This ingenious etymology is, unfortunately, impossible to accept. The medieval form in question turned up in the thirteenth century, while the earliest occurrence of hurra (so) in German poetry goes back to 1773. Where did the word lie dormant for four hundred years?

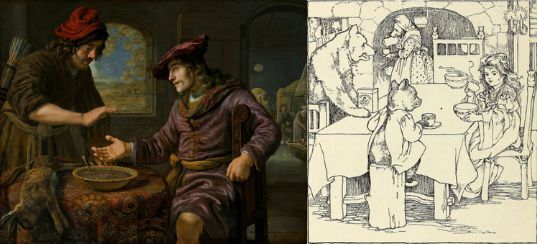

A mess of pottage next to a dish of porridge. What a mess!

A mess of pottage next to a dish of porridge. What a mess!(L: “Esau and the mess of pottage” by Jan Victors via Wikimedia Commons, public domain; R: “St. Nicholas” by Mary Mapes Dodge, via Picryl, public domain)

The most authoritative etymological dictionary of German was written by Friedrich Kluge. After his death, several editors worked on updating his work, and Kluge himself often changed his formulations from edition to edition. Walz traced the history of this entry from 1882 to 1940: reference to the medieval form in it appeared and disappeared. (The same holds for the later editions.) This is a usual scenario, and a similar story can be told about the etymology of many English words in the subsequent editions of Webster’s dictionary, The Concise Oxford English Dictionary, and others. Here, Walz’s conclusion sounds persuasive: given the great time interval between the thirteenth and the end of the eighteenth century, we have no right to derive the German word from a similar-sounding medieval form. The coincidence must be fortuitous.

As mentioned above, the other ghost in the history of hurrah that refuses to be laid to rest is Russian ura!, an exclamation of triumph and encouragement. Allegedly, it was borrowed from German, but many amateurs and professional linguists have observed that the same word is common in several Turkic languages, and, considering how often Russian soldiers fought their Turkic neighbors, the Oriental origin of the Russian exclamation seems rather probable. Also, in the process of borrowing from German, Russian would probably not have lost the initial consonant and modified it to a real fricative, like German ch.

From the Russian Civil War about a century ago: URA!

From the Russian Civil War about a century ago: URA!(By Алексей Задонский via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

It may be useful to throw a quick look at a few similar words, hue and cry among them. The etymon of this tautological Anglo-Norman phrase (tautological, because both components mean the same) is hu e cri “outcry and cry.” The initial group gr– (as in grumble, growl, grouch, grouse, and the like) is obviously sound-imitative. H-r is less expressive, but the aforementioned German hurren and English hurry (the English verb emerged only in Shakespeare), the noun hurly-burly; the verb hurl, an early loan from French, though the French verb may be of Germanic origin, and even hurt (its initial meaning was “knock”: compare hurtle) indicate that the group h-r, even if it is not as expressive as gr-, does occasional service in this direction. The weak sound h- goes back to a real fricative (like German ch), and followed by r, outside English, it produces a lot of words related to noise.

Is this then the origin of hurrah? Just a sound-imitative exclamation? Possibly so. And hurry has the same origin? Perhaps. Hardly a triumphant finale. No, not really. Little pitchers have long ears and short words have a complicated etymology. Sorry for producing a whiff instead of a hurricane.

Featured image by Ambreen Hasan on Unsplash, public domain

Management in the twenty-first century [infographic]

What does a modern-day workplace look like? Now, more than ever, businesses and offices are adjusting to changes in management and working patterns.

Explore our handy infographic, specially curated to reflect current discussions on workplaces and management techniques. Discover the latest business and management research from OUP, freely available to browse at your convenience.

Navigate the infographic by clicking on the relevant working space below to read chapters and articles on key topics including remote working, automated learning, sustainability, and business ethics.

August 2, 2022

A democracy, if we can keep it

I recently explored the Gun Violence Archive, one of many online resources for tracking the location, death toll, weapons used, and other grim details related to the nearly 19,000 gun deaths so far in the United States in 2022. Most troublesome are the attacks related to the widely-circulated “white replacement theory,” the outlandish and once-fringe idea that a sinister plot is at work to replace what Fox News’ Tucker Carlson calls “legacy Americans.” The “legacy” Carlson invokes is, of course, white and Protestant. With roots that go back to the earliest days of American life, such anxieties that a “way of life” is at risk—from a supposed influx of illegal immigrants, or a plot to register illegitimate voters, or from the machinations of extremists—have religion at their heart. Here the ongoing project to achieve a genuine multiracial democracy is framed as an assault on God-fearing “tradition.”

Related is the recurrent conservative theater around school curricula, an enduring winner that is dusted off every few years by think tanks, political action committees, and aspiring candidates like Virginia’s Glenn Youngkin, who successfully ran his gubernatorial campaign around slogans involving “parents’ rights.” The issue had arisen from the American right’s fierce opposition to Critical Race Theory (CRT), a legal theory examining the legacy of structural racism that first came to public light when President Bill Clinton abandoned as his nominee for Attorney General one of that theory’s best-known proponents, Lani Guinier. Classes that teach about slavery or xenophobia are themselves framed as being anti-American, the implication uncomfortably close to Josiah Strong’s 1885 book Our Country, which linked American civilization to white Protestantism.

Instead of an America committed to improved roads, green energy, and safeguarding voting rights, we live in an America seemingly choked with conspiracy theory, jingoism, hand-wringing about the right quotient of “woke” that Democrats can carry, and ongoing claims about the unprecedented liberal assault on religious liberty that has made such ferocity necessary. Organizations like Turning Point USA fill social media with alarm about “cultural Marxism” or a “radical secular agenda” threatening America’s greatness, talking points eagerly recirculated up and down the institutional ladder by Republicans who have long mastered selling panic over policy.

These are the makings of what scholars and journalists have in recent years come to call Christian Nationalism. While there is no doubt that far-right Protestants have made considerable inroads into all three branches of American government and have worked to undermine democratic institutions in tangible ways, obsessions about the religiousness of these efforts have done little to halt these efforts. This is because Republicans have made this obsession their most successful rallying cry. Whether at a local school board meeting where parents assert their children are being taught to hate God’s chosen nation, or at the Conservative Political Action Committee annual meeting, the very notion that a “lib” might be deriding conservative Christianity is, and has long been, the chief source of this movement’s energy.

Clearly, then, considerable resources and organization have gone into trumpeting these varied claims that white religion is persecuted. Legions of pundits have pointed out the unreality of persecution claims coming from largely comfortable white conservative Christians. Scholars have glanced on such notions amidst the tide of books about the “culture wars.” But I believe that most current approaches to this subject have it backwards: the much-ballyhooed Christian nationalism of our time is the product of multiple forces, but it is not the linchpin for understanding the roots of the many problems bedeviling America, nor should it be the main vector of analysis if we want to restore a frayed democracy. Instead of asking “why are evangelicals this way?”, we should ask “what has happened in America to enable such fearful changes?” The decades-long echo of white conservative grievance and those who debunk it is, I contend, a distraction from the urgent need to reassess key elements of what it actually means to live in a democracy.

To focus only on conservatives who protest against “religious bigotry,” or even to hope with good reason for the amplification of other religious voices, is to misconstrue the condition: Americans have not come to grips with our ambivalent attachments to democracy itself. This failure is exacerbated by America’s abundance of rage and therapeutic discourse alike, which work together to deflect the fear that our lives lack significance and that America has failed at democracy. Embattlement may liven up a narrative, but it directs us away from deeper sources of political discontent.

Reconsider the circulation of the “white replacement theory” and anxiety around CRT. Certainly, a kind of religious entitlement is at work in these fantastical grievances. No sane observer could deny that. Yet what I find more evident is a decades-long failure of particular institutions and political norms. As infuriating as it is to encounter fellow citizens who seek to censor the historical record, we should strive to ground all debates about education in the very idea of what democracy is. To get past these managed dramas, we might better embrace history as a place of discomfort. At this juncture in American history, the most compelling reason to investigate the past is to make the future better. Conservative religion and conservative readings of history are not privileged, but are, like all other expressions of identity and narrative, simply part of the range of American things for historical inquirers to evaluate. These evaluations should be guided not by fidelity to an ossified past but by resistance to self-aggrandizement and to the politics of domination.

Similarly, and separately from the urgent need for firearms restrictions (“well-regulated,” anyone?), America is clearly in need of a rigorous, sustained reexamination of just what citizenship and birthright mean in our time. Things are indeed changing. While most Americans are comfortable with or even happy about that fact, it is no coincidence that the rise of extrajudicial militants—which emerged from the shadows in the 1990s, though its roots are far older—occurred during the tenure of America’s first non-white president, and many of its fiercest practitioners helped plan the Capitol insurrection. Conservative pundits and members of groups like the Oath Keepers warned that Christians were going to be hunted down after Obama seized the guns, so there was little use acting as if the rules applied to them.

Never was the experience of white masculinity so publicly insistent on its own victimization when the mere existence of other humans who would not be silent about their own histories, experiences, and actual oppression was translated into the idiom of attack. Indeed, in response to Black Lives Matter marches in response to the execution of George Floyd in May 2020, activists like Charlie Kirk and Trump himself intoned consistently that a Biden victory would entail the end of the suburbs and churches.

In the smoldering wake of the Trump administration, the national conversation has shown signs of opening up into larger considerations of belonging, entitlement, and, indeed, birthright. Yet the opposition is fierce and our public institutions deeply compromised. Our politics is the result of decades of haranguing about “tradition” and “the American dream” rather than what citizenship and the good society substantively require. It is the result of thinking that the politics of economic materialism can or should be meaningfully distinguished from identity politics. It is the result of decades of hucksters and anti-democrats convincing large swaths of the American people that if someone else is allowed to count as part of the “we” in “we the people,” our own status will immediately become threatened. And, it must be admitted, the academy has a role to play in this for having become so nervous about the genuinely social critical role scholars should play.

At this fearful time in American democracy, the best way to starve anti-democratic forces of their energy is to change the subject away from conservative religion and demand investment in civic education, democratic localism, and human rights. The next five to ten years will tell the tale on American democracy itself. If Americans let the forces of authoritarianism continue to set the tone and the subject, it will be impossible to do the work necessary to keep it.

Featured image: 2021 storming of the United States Capitol via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 2.0)

August 1, 2022

The politics of interracial friendship

There have been instances of interracial friendship even in the worst of times—from Benjamin Banneker and Thomas Jefferson’s ill-fated efforts to the more hopeful stories of James Baldwin and Marlon Brando and Angela Davis and Gloria Steinem.

Explore five of these noteworthy friendships, which have served as windows into the state of race relations in the United States and often as models for advancing racial equality.

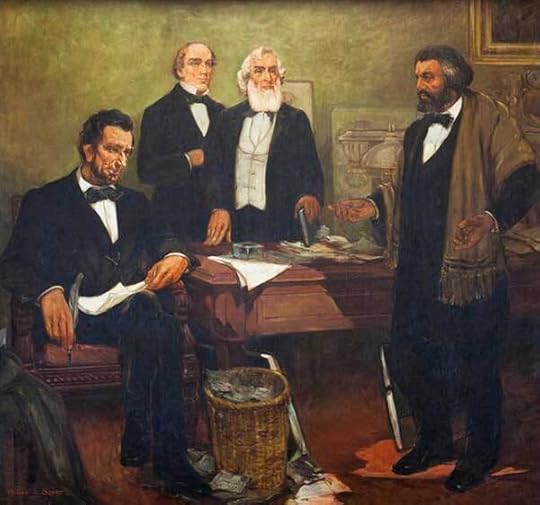

Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass 19 August 1864

19 August 1864Portrait by William Edouard Scott of meeting between Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass

(Photo credit: Carol M. Highsmith/WikiMedia Commons)

Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass met three times at the White House, with the first meeting in 1863. Though Douglass was amongst Lincoln’s harshest critics as Lincoln often failed to take a strong stance against slavery, the two eventually formed a political alliance and friendship. Their friendship would be inextricably tied to expanding democracy in America. In 1864, Lincoln enlisted Douglass’ help to inform those enslaved in the South that their freedom would be granted within Union lines by the Emancipation Proclamation.

“Douglass never let his affection and admiration for Lincoln get in the way of frank assessment of his legacy. He saw Lincoln’s flaws as well as his strengths, placing them beside each other so as to draw out the significance of what Lincoln had achieved.” – Read more about their friendship in chapter 2 of Stars and Shadows.

Eleanor Roosevelt and Mary McCleod Bethune 18 May 1943

18 May 1943Activist and leader Mary McLeod Bethune and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt speaking before a National Youth Administration meeting.

(Photo credit: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection, LC-DIG-fsa-8b29202)

Mary McCleod Bethune and Eleanor Roosevelt met in 1927 at a conference for women club leaders. Bethune’s relationship with Roosevelt brought her to the White House and she wielded significant power and influence as the first black woman in an advisory role to the president. Under her leadership, the National Youth Administration provided training and employment to thousands of black Americans. Roosevelt took a larger role in element of racial justice than the president, who needed to maintain political considerations and Southern white support. As with any interracial friendship of the time, their relationship had its limits, however, together the two women worked on many endeavors for advancing the position of black Americans and provided a symbol for what might be possible on a national level.

“For over a decade, Bethune and the first lady engaged in a political dance that sought to advance mutual, and at times discordant, goals. On the one hand, Bethune fought to increase the numbers and influence of African Americans in government; she likewise sought to empower black institutions, while advancing their economic standing.” – Read more about their friendship in chapter 4 of Stars and Shadows.

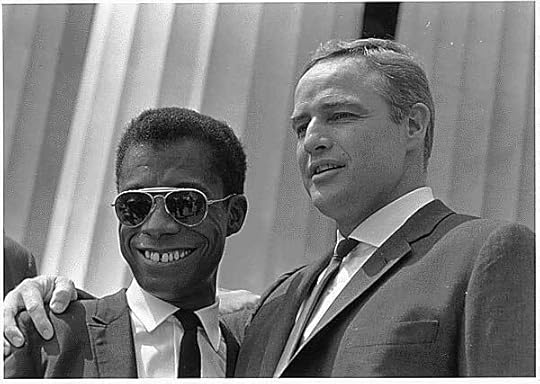

James Baldwin and Marlon Brando 28 August 1963

28 August 1963James Baldwin, celebrated black radical writer, and Marlon Brando, actor and activist, at the Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C.

(Photo credit: U.S. Information Agency. Press and Publications Service/WikiMedia Commons)

Marlon Brando and James Baldwin, two influential figures and activists of the 20th century, met in 1944 in New York, drawn together perhaps by artistry and their own personal struggles. Both attended the Civil Rights March on Washington in 1963. Their friendship influenced their work and views on race throughout their lives and was of great significance to both men. It reflected what could be possible in post-war America.

“For Baldwin and Brando, the March on Washington was but a piece of a decades-long journey—but in a sense, 28 August 1963, was the apex of their powers of collaboration. Was it enough—for either of them? For the country? What was accomplished that day—and how much more remained to be achieved?” – Read more about their friendship in chapter 6 of Stars and Shadows.

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel and Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. 7 December 1965

7 December 1965Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, theologian and scholar, presenting Judaism and World Peace award to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

(Photo credit: New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection/WikiMedia Commons)

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel and Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. met at Chicago Conference on Religion and Race in 1963. They shared a strong moral sense of justice based on their spirituality. Heschel was by King’s side during the Selma March of 1965 and when he gave his Riverside speech condemning the Vietnam War in 1967. Their friendship also provided an important example of overcoming historical tensions in Black-Jewish relations.

“Their bond, one directed toward a great democratic project, elevated the nation’s attention to moral courage in the face of deep injustice. It did not end altogether debates over what constitutes the nature of right or justice—even among friends and people with shared political visions.” – Read more about their friendship in chapter 8 of Stars and Shadows.

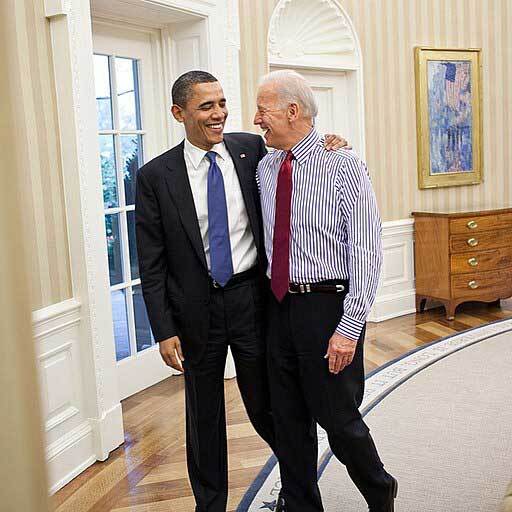

Joe Biden and Barack Obama 25 June 2015

25 June 2015President Barack Obama and Vice President Joe Biden in the Oval Office

(Photo credit: Phil Souza/WikiMedia Commons)

Barak Obama was the 44th president of the United States and the first black president, with Joe Biden serving as his vice president. Their shared value of family fostered their friendship and emotional connection. Much public attention and academic discourse has been focused on their friendship, including many viral memes. Joe Biden is the 46th and current president of the United States. Their friendship played a vital role in his rise to the presidency.

“Though the friendship of Biden and Obama carries great symbolic weight, its authenticity remains unquestioned. Part of the reason is that the relationship developed from real missteps along with personal and idiosyncratic differences.” – Read more about their friendship in chapter 10 of Stars and Shadows.

July 31, 2022

Religion: was Shakespeare raised Catholic?

In this OUPblog series, Lena Cowen Orlin, author of the “detailed and dazzling” The Private Life of William Shakespeare, explores key moments in the Bard’s life. From asking just when was Shakespeare’s birthday, to his bequest of a “second-best bed,” to his own funerary monument, you can read the complete series here.Was Shakespeare raised Catholic?

In this OUPblog series, Lena Cowen Orlin, author of the “detailed and dazzling” The Private Life of William Shakespeare, explores key moments in the Bard’s life. From asking just when was Shakespeare’s birthday, to his bequest of a “second-best bed,” to his own funerary monument, you can read the complete series here.Was Shakespeare raised Catholic?Biographical writing about Shakespeare began within 50 years of his death. In Stratford-upon-Avon, there arose a cottage industry in local anecdotes and latter-day legends. The late eighteenth-century wheelwright and self-styled antiquarian John Jordan was an especially prolific source of Shakespeare stories. One concerned the religion of Shakespeare’s father.

In 1784, Jordan reported that, nearly 30 years earlier, a bricklayer had discovered a pamphlet in the rafters of the building we know as “Shakespeare’s Birthplace.” It was a formulary for any member of the “holy Catholic religion” who might find himself on his deathbed without a priest to perform the last rites. The pamphlet lacked a first page, but Jordan called it the “Spiritual Last Will and Testament of John Shakespeare.” Each article of faith indicated that “I, John Shakespear, do protest,” or “pardon,” or “pray,” as ordained. Because the pamphlet was soon lost, we do not know whether a single hand had written the entire text, whether a second hand had filled in pre-devised blanks with John Shakespeare’s name, or whether the closing subscription was an autograph. (If so, it would have been the only known instance of a John Shakespeare signature; in all other documents, he signed with a mark.) The editor Edmond Malone published a transcript of the pamphlet, but sceptically, and he eventually concluded that it had no connection to “any one of our poet’s family.”

Shakespearians asked themselves whether Jordan had fabricated the “Spiritual Testament,” as he had done other supposed relics. In 1923, however, Herbert Thurston established the early modern authenticity of the tract when he discovered a Spanish translation attributed to the sixteenth-century cardinal San Carlo Borromeo and published in Mexico City in 1661. Other Mexican editions were then identified, most from the eighteenth century. The version that finally brought us closest to John Shakespeare, who died in 1601, was an English-language text of Borromeo’s Testament of the Soul printed in 1638.

This link between John Shakespeare and Roman Catholicism will always be shadowed by its origin story. Jordan gave contradictory reports of the “discovery,” the document was found in a building 150 years after John Shakespeare had lived there, and with its loss went all opportunity to verify paper, ink, and hand. The Testament gained biographical traction, however, when paired with a document discovered by the eminent archivist Robert Lemon and published by John Payne Collier in 1844. Here we were on much surer ground, with an official report commissioned by the Queen’s Privy Council in 1592. Amid fears of a Spanish invasion, local authorities were charged to identify men and women who did not attend Church of England services (as was compulsory at the time). Such “recusancy” seemed a likely symptom of Spanish sympathy. The list of suspect names returned by Warwickshire commissioners included that of John Shakespeare. Many biographers believe that the report proves John Shakespeare to have been a Roman Catholic.

This is to misread the document, which was a terror watch list. The commissioners separated their collection of names into risk categories. “Dangerous” and “seditious” recusants travelled to Continental seminaries, harboured Catholic priests, delivered secret letters “between papist and papist,” refused to profess loyalty to the queen, or took their children to “popish” priests for baptism rather than to the parish church. Most of these “obstinate” recusants were later noted in the report’s margins to have been “indicted.” John Shakespeare was in a different category entirely, one of a group who “come not to church for fear of process for debt” – that is, to avoid being jailed for failing to repay his creditors.

In Tudor England it was illegal for sheriffs to enter private homes to make arrests; their sting operations were conducted at parish churches. From the late 1570s through the 1590s, when John Shakespeare was sued repeatedly for debt and multiple warrants were issued for his arrest, sheriffs would have waited for him at Stratford’s Holy Trinity Church. In other words, he had good reason to stay away. For the Warwickshire commissioners to describe John Shakespeare as a man who avoided church in order to avoid arrest was their way of saying that he was not a “wilful” recusant—that is, not absent by choice. They placed a confirming checkmark next to his name, not the word “indicted.”

There are few other signs that John Shakespeare was a non-conformist. He baptised eight children at Holy Trinity, for example. His withdrawal from civic office in 1586 has sometimes been attributed to recusancy, but this, too, was a consequence of financial failure. He was asked to step down after he ceased paying his share of the officers’ expenses. If his son was raised Catholic, neither the “Spiritual Testament” nor the Warwickshire commissioners’ report confirms it. Instead, the evidence shows that Shakespeare was raised by a man who had an early spurt of great success but who then suffered a business collapse from which he would never recover.

Featured image: Interieur van de Holy Trinity Church te Stratford-upon-AvonStratford-on-Avon The Parish Church-the Chancel via Wikimedia Commons (public domain)

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers