Oxford University Press's Blog, page 66

October 23, 2022

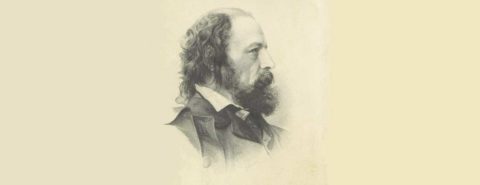

The Butcher’s Books: how did Tennyson write In Memoriam?

Where do we go to mourn the dead? A graveyard? A photograph album? A Facebook page? The very intangibility of death makes us yearn for a physical space to locate grief—a space we might return to. For many Victorians, mourning took place in notebooks. This was certainly the case for the future poet laureate, Alfred Tennyson, who, in 1833 learned that his closest friend, Arthur Henry Hallam, had died at age 22. In response, Tennyson began to write verses that, over the next seventeen years, would accumulate to become the great Victorian elegy, In Memoriam.

Tennyson recorded quotations and memories associated with Hallam in long, thin blank books that butchers traditionally used to account for profits and losses; accordingly, these manuscripts became known as the Butcher’s Books. Their structure mirrored the form of the poem developing inside of them. By writing in short quatrains, Tennyson could linger on the empty spaces left between thoughts—the divisions that create a stanza. And while poetry performs its own acts of cutting—by dividing language into literary forms—Tennyson emphasized carving as a theme. The Butcher’s Books highlight how cutting (stanzas, for example), despite its violent connotations, proved to be generative: the butcher disassembles a carcass and transforms it into nourishment. Likewise, Tennyson arranged worn-out commonplaces to form a spiritually recuperative poem.

Luckily for us, the University of Cambridge has digitized the Butcher’s Book in their possession (the other is at the Tennyson Research Centre in Lincoln): readers can view the manuscript here. The Wren Library at Trinity College, Cambridge, is a fitting home for this manuscript because it is where Tennyson and Hallam met as students. Even as Tennyson was composing In Memoriam, friends asked if they could donate loose pages to the college: Edward Fitzgerald wrote to Tennyson asking, “…if you have any objection to my giving two or three of the leaves of your old Butcher’s Book (do you remember?) to the Library at Trinity College?” (4 December 1864, Letters, E.F. 2:535).

Friends like Fitzgerald understood the immense value of access to the poet’s manuscripts. The same impulse motivates the remainder of this post, which serves as a guide through several fascinating aspects of the Trinity College manuscript.

8v & 9r: One of the first pages in this manuscript contains a detailed sketch of a man crying, perhaps evoking the emotional tenor of the following pages. More pointedly, the sketch recalls descriptions of Tennyson reading from this notebook as tears streamed down his face. Aubrey De Vere described one such reading in April 1845: “he read many of the poems to me….till the early hours of the morning. The tears often ran down his face as he read…They were written in a long and narrow manuscript book, which assisted him to arrange the poems in due order by bringing many of them at once before his eye” (Memoir I. 293). On the recto (the right page), we can observe the space between In Memoriam’s stanzas, illustrating De Vere’s point.

The reader might also notice that the top section of the verso (the left page) has been cut out. There are, in fact, many such cuttings throughout the manuscript, which adds another suggestive layer to the butcher-theme. Sections of this notebook were cut out for several reasons: to give to friends or (shockingly) to be used to light pipes. Fitzgerald describes “the Butcher’s Book, after its margins serving for Pipe-lights, went Leaf by Leaf into the Fire.”

45v & 46r: Many of the cuttings also excise comments made in pencil by James Spedding, another friend from Cambridge. Consider Spedding’s comments on what would become Canto 57. Spedding writes: “It seems to me that the 3rd stanza is not wanted and w[oul]d be better cut. The second does not please me…” Spedding ends his note with encouragement: “With this exception I think it beautiful.” Tennyson took Spedding’s advice and cut the second and third stanzas for the final version of In Memoriam. This page is also fascinating because of how Tennyson alters his handwriting as he evokes Catullus’s classic elegiac line, “Ave, Ave, Ave.” (A few pages earlier, Tennyson imitates medieval script while mocking worn out commonplaces of mourning (44r).) Tennyson supposedly considered ending the poem here with “and ‘Ave, Ave, Ave’ said, / ‘Adieu, Adieu’ for evermore.” But he chose to conclude on a happier note—with a wedding. Let’s do the same.

1r: The Trinity Butcher’s Book does not include what would become the “Epilogue” that describes the marriage of Tennyson’s sister in 1842. So, for a happier conclusion, we’ll return to the beginning of the manuscript, with Tennyson’s inscription on the “Anniversary of Hallam’s Wedding day” in 1886, when Tennyson gifted the manuscript to Lady Simeon.

Clearly, Tennyson shared his In Memoriam drafts with a close circle of friends. Accordingly, one answer to the title of this post (“How did Tennyson write In Memoriam?”) is simply that he wrote it among friends.

Featured image: Alfred Tennyson from “The Works of Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Poet Laureate”, via Picryl, public domain

October 22, 2022

How well do you know these spooky Oxford World’s Classics?

Whether you’re accompanying children door-to-door as they scream “trick o’ treat!?” or donning a scary costume just to sit on the couch and eat candy in front of your favourite horror flick, Halloween is a spooky and fun time for all!

To help get you in the mood for Halloween this year, we have created a quiz to test your knowledge on some of Oxford World’s Classics scariest tales. Are you up for the challenge?

The books in the quiz are:Dracula by Bram Stoker, available hereThe Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde, available hereFrankenstein by Mary Shelley, available hereThe Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole, available hereThe Great God Pan and Other Horror Stories by Arthur Machen, available hereThe Mysteries of Udolpho by Ann Radcliffe, available hereThe Monk by Matthew Lewis, available hereThe Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde and Other Tales by Robert Louis Stevenson, available hereZofloya; or The Moor by Charlotte Dacre, available hereThe Turn of the Screw and Other Stories by Henry James, available hereFeatured image by Nika Benedictova on Unsplash, public domain

Sanctions: who uses sanctions, why, and what impact do they have?

Even before the extensive economic sanctions against Russia for its 2022 invasion of Ukraine, it was hard to browse the news without seeing reports of yet another imposition of sanctions by one country or another.

The United States uses sanctions so much they’ve been dubbed “the Swiss army knife” of American foreign policy, different Presidents varying more in how they use sanctions than how much. While China continues to be resistant to being targeted with sanctions over human rights, as its economic power has grown it has become a frequent wielder of sanctions of its own. One study identified 19 cases of China-imposed sanctions between 2010 and 2020, half of which were since 2018. Russia is retaliating against the US and Europe with its own energy sanctions and other countersanctions. In recent years, the European Union has been second only to the United States in sanctions frequency. The United Nations, which only imposed sanctions four times in its first two decades, has done so over 40 times since then.

While sanctions go way back in history—Athenian sanctions against Sparta in 432 BC, Napoleon’s 1808-1814 Continental System—it wasn’t until the second half of the twentieth century that their frequency started increasing. From 1915 to 1940, there were only 11 sanctions cases, averaging out to less than one case per year. During the Cold War (1945–1990) there were 610 cases, a 13.5 annual average; from 1990 to 2005, this further increased to 802 cases, a 53.5 annual average.

Do sanctions work?With such frequency of use, you’d think sanctions were a sure-fire weapon. Yet there is lively debate over their success rate. One study puts success at 22%, another at 34%, another at 44%. Another study concludes that compared to military force sanctions have “little independent usefulness.” On the other hand, there is a view among some scholars that sanctions success gets “systematically underestimated” by studies that “accentuate the negative and downplay the positive aspects.” I know from my own experience serving in the US State Department and in other policy roles that policymakers often see sanctions as a weapon of choice.

So, some initial puzzles: why are sanctions used so much? What are their varieties? How to measure success? What key factors affect their success? What lessons can policymakers derive for why, how, and when to wield sanctions? In my work, I have addressed these and other fundamental questions about sanctions both historically and today.

“The gains from taking a principled stand have to be weighed against the ramifications of doing so, manifesting the ethical dilemma of right intentions but wrong consequences.”

In assessing sanctions success, it’s especially important to bear in mind that while some success is inherent in the very imposition of economic costs, even substantial costs do not always lead to policy compliance. Cuba has borne American sanctions for over half a century, yet the regime has stayed very much in place. Sanctions against North Korea have imposed plenty of costs, but its nuclear weapons programs have grown ever bigger. US-led sanctions have hit Russia hard, but Putin has kept the Ukraine war going and is retaliating with natural gas countersanctions against Europe.

Even when sanctions do achieve some “political gain,” they can also inflict “civilian pain” with humanitarian consequences so severe as to raise fundamental ethical questions. On the one hand, how could the US and EU not impose sanctions on the Myanmar military amid its brutal February 2021 coup? On Syria for Bashar Asad’s atrocities? Shouldn’t brutalizers be made to pay a price? Yet in both those cases sanctions have ended up misfiring in hitting the populace more than the regime. In such instances the gains from taking a principled stand have to be weighed against the ramifications of doing so, manifesting the ethical dilemma of right intentions but wrong consequences.

To the extent that sanctions do succeed, three factors—multilateralism, proportionality, and reciprocity—generally prove key.

1. MultilateralismBroad multilateral support helps limit alternative trade partners to which the sanctioned state can turn. Sanctions mandated by the UN Security Council have this advantage, albeit in some instances this gets impinged by loose enforcement against sanctions busting. While the sanctions against Russia over Ukraine do not have a Security Council mandate, the coalition supporting them is among the broadest ever assembled. Even with China, India, and some other countries providing Russia with some alternative trade, the economic impact has been considerable.

2. ProportionalityGiven that sanctions are a limited coercive means—no sanctioned country has ever just said “uncle”—their success is more likely for proportionally limited objectives. Contrast, for example, the Obama Iran sanctions succeeding in helping get the nuclear non-proliferation agreement but the Trump sanctions, despite having even greater economic impact, failing to set off the regime change it sought.

3. ReciprocityReciprocity linking sanctions and inducements also increases chances of success. This entails diplomatically playing a sanctions-strengthened hand for favourable, but still somewhat reciprocal, terms. The 2003 deal US and British negotiators struck (including William J. Burns, then-Assistant Secretary of State and now CIA Director) with Muammar Qaddafi’s Libya provided sanctions relief in exchange for terrorism concessions and WMD dismantling, the significance of which became especially evident amidst the 2011 Arab Spring chaos and the instability since. Striking such a balance on Russia-Ukraine, being sufficiently punitive to have US, European, and Ukrainian support, while still providing a basis for Putin or any Russian leader to agree, will be particularly tough.

Within this overarching framework patterns emerge in how different sanctioners wield their sanctions. The objectives for which the Biden administration uses sanctions differ somewhat from the Trump administration, but its frequency of use is even greater. Along with Beijing’s officially promulgated sanctions, what’s particularly interesting in China’s use of sanctions is its more informal “cueing” through signals for social media outrage and consumer boycotts against “anti-China” countries and companies. Russia is betting heavily that its energy countersanctions will win the current economic war of attrition. The EU is making sanctions a major tool of its Common Foreign and Security Policy. The UN is working to improve the roles of its Panels of Experts and Sanctions Monitoring Committees for more effective enforcement.

All told, it’s a pretty sure projection that sanctions are here to stay—making both scholarly theorizing and policy strategizing all the more important going forward.

Featured image: Venti Views on Unsplash, public domain

October 21, 2022

Environmental DNA: the future of forensic testing?

Can plants solve crimes? It’s been known for a long time that botanical evidence has forensic value. Back in the 1930s, Edmond Locard, the “father of forensics,” reported how a single seed of a rare species of dandelion caught up on the jacket of a murder suspect placed him at the scene of the crime. Locard had observed the plant growing next to the body. This sort of plant trace evidence is more valuable than ever today in forensic investigations and can include microscopic materials from plant seeds, pollen, spores, and their DNA.

Indeed, exciting recent advances allowing the detection and sequencing of minute amounts of DNA are providing new tools for conservation biologists and forensic scientists. Specifically, the detection of environmental DNA (eDNA) in water, air, dust, or soil samples can be used to identify the presence of plants, animals, and microbes that can’t be otherwise easily observed. Organisms shed their DNA into the environment as skin particles, cells, and liquids, even while still alive. When these DNA fragments are sequenced they can be matched to DNA sequences from known organisms in eDNA reference libraries providing an identification. Even when comparison sequences from named organisms are unavailable, as they are for many microbes, the number of unique eDNA sequences can provide a biodiversity estimate. As noted by environmental scientist Eric Larson at the University of Illinois, this approach has value in the detection of hard to observe or cryptic organisms, such as rare species. Levels of biodiversity can be estimated with important conservation implications, especially in light of climate change that is threatening natural ecosystems.

“Exciting recent advances allowing the detection and sequencing of minute amounts of DNA are providing new tools for conservation biologists and forensic scientists.”

eDNA technology allows improved identification of traditionally surveyed organisms used in forensic examination of trace evidence (e.g., pollen and fungal spores, or even fragments of plant tissues). The method provides opportunities to characterize the microbial fungal and bacterial components of samples. One exciting avenue that has been proposed by Sarah Ishak at the Université de Sherbrooke is the characterization of the leaf phyllosphere (microbial fungi that grow on plants surfaces such as leaves) associated with trace evidence samples. These fungi may be unique to the plants from the location and environment that they grew in providing an “assignment capacity,” i.e., crucial links to crime scenes. Amaury Frank at Ghent University takes this idea a step further proposing that plant eDNA in soil samples can be used to identify specific vegetation communities from where a sample originated.

The promise of forensic eDNADoes eDNA sampling have forensic value in criminal or civil cases? Forensic botanist Mark Spencer certainly thinks so suggesting its value in the geolocation of crime scenes, clandestine burials, and providing a means to improve “traditional” linking of suspects to victims. Proof-of-concept tests by Fabian Roger at Zurich University and James Comolli at MIT of dust samples collected from the air have shown that eDNA screening from objects of evidentiary value, such as clothing, vehicles, or instruments, could be used to estimate their geographic point of origin. Plant eDNA in the soil on the sole of a suspect’s shoe could be traced back to unique vegetation at a crime scene.

The identification of microbes, determined via their eDNA, has forensic applications in minimum post-mortem interval (PMI) estimation, human suspect identification (though transfer of bacteria to surfaces), and toxicology cases (by identifying microbes involved with toxin degradation).

Forensic eDNA applications are few at present but are likely to increase as the approach becomes more widespread and is introduced into the court system. Standardisation of the methodology and wider development of DNA databases is needed to ensure that results of eDNA applications are consistent, scientifically reliable, and valid so that they can accepted into evidence.

A pioneering eDNA court caseA pioneering forensic eDNA involved Asian carp in 2010. Biologists in Chicago were concerned that the opening of dams and weirs in the Chicago Area Waterways System (CAWS) would allow Asian carp to migrate up from the Mississippi River Basin into Lake Michigan. Asian carp are a hugely problematic exotic fish that reduce biodiversity of native fish in waterways. These large fish jump out of the water into boats injuring people (imagine being hit in the head by a 100 lb fish!). eDNA testing carried out by the US Army Corps of Engineers supported anecdotal sightings that live Asian carp were likely present in the CAWS indicating that at least some fish were close to Lake Michigan.

The US State of Michigan and five partner plaintiffs brought action against the Army Corps of Engineers to require the building of a hydrological barrier between the lake and the basin to stop the spread of Asian Carp. The eDNA evidence was a critical part of the forensic evidence considered by the court even though the case was dismissed as the plaintiffs did not demonstrate the Corps failure to abate a public nuisance (i.e. presence of Asian carp in the Great Lakes).

So, can we use plants to solve crimes? When Edmond Locard introduced his Exchange Principle in 1920, he emphasized the forensic value of materials identified in “les poussières organiques” (organic dust) to link suspects to victims and crime scenes. Over 100 years later, the examination of forensic trace evidence through eDNA testing is poised to take a step forward that he likely never imagined.

The radical reinterpretation of the fasces in Mussolini’s Italy

In November 1914, when Benito Mussolini, then prominent as a revolutionary socialist, tried to mobilize popular opinion for Italy to intervene in World War I, he gave the name “Autonomous Fasci of Revolutionary Action” to his disparate supporters. The term “fascio” (plural “fasci”) was then common in Italy’s political lexicon, in its core meaning of “bundle”, to denote a loosely-organized group grounded in a common ideology. It was the workers’ movement in Sicily of the mid-1890s that firmly cemented the word “fascio” into everyday use. At the time, the press even sometimes tagged members of the Sicilian fasci as “fascisti.”

Two decades later, especially after Italy entered the War in May 1915, there were dozens of activist groups of all stripes with “fascio’ in their name. Yet it was only after the conclusion of World War I that one of the political fasci used the old Roman symbol of the fasces—a bundle of wooden rods and a single-bladed axe with leather straps—to express its identity, and had its members proudly lay claim to the somewhat pejorative moniker “fascisti.” The take off point was Milan’s Piazza San Sepolcro on 23 March 1919, when Mussolini relaunched his war movement as a paramilitary group, the “Italian Fasci of Combat.”

The fasces in historical traditionIt is said that the charismatic “poet-soldier” Gabriele D’Annunzio (1863-1938) had urged Mussolini to adopt as the emblem of his new party the Roman fasces: in essence, a mobile kit for punishment, one intended to induce feelings of respect for the state’s highest authorities as well as fear. Ancient tradition is unanimous that the emblem had come from the Etruscans to archaic Rome, where 12 attendants known as “lictors” each carried these fasces in procession before the king, to mark his full civil and military power and with it, his capacity to inflict either corporal or capital punishment. What is certain is that the institution had a run of at least 1,800 years, through Rome’s Republican and Imperial periods, and then (in an attenuated form) to probably the end of the Byzantine empire.

“Use of the historical Roman emblem to a stunning degree helped valorize Mussolini’s violent methods.”

In sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Europe, authors and artists offered a new twist in the understanding of the fasces. We now find representations of the rods with axe regularly evoking memories not just of Roman rule, but also of a popular but decidedly non-pertinent Aesop fable featuring an old man, his quarrelsome sons, and a bundle of sticks. The point of the tale is that one can break rods easily one at a time, but not when bound together—a visual lesson of the power of unity. This learned conflation was responsible for promoting the emphatically non-Roman idea that the fasces represented unity, and good government in general, which later powerfully informed political iconography in both the young United States and revolutionary France.

The fasces as fascist iconographySome months after San Sepolcro, we find Mussolini vigorously promoting the symbol of the fasces, first to brand his “Fascist Bloc” in the Italian general election of 16 November 1919. In late October his campaign proclaimed that “the Fascist emblem signifies unity, force and justice!”, and showed Roman fasces with cords loosened at the base of the bundle, evidently in the process of being readied for punitive use. Starting in 1920 the fasces adorned the membership cards of the movement—initially with loose cords, later without. Use of the historical Roman emblem to a stunning degree helped valorize Mussolini’s violent methods, which intensified especially from spring 1920. It also helped grow his movement. By the end of the next year, Mussolini’s group had swelled reportedly to more than 300,000 members and was reconstituted as the National Fascist Party (Partito Nazionale Fascista, or PNF).

After his movement’s largely bloodless “March on Rome” (28-30 October 1922) that felled the elected government, Mussolini—now as prime minister—set out immediately to force the fasces into every crevice of Italian daily life, from coinage and postage stamps to cigarette packaging. In the first half of 1923, the Fascist-led government tasked Italy’s most prominent archaeologist, Giacomo Boni (1859-1925), with divining the most “authentic” form of the Roman fasces—not so much out of genuine academic curiosity, but surely to set a single official form as the basis for a visual identity system. Amazingly, one fringe group of occultists sought to counter this effort by creating what they regarded as a spiritually supercharged fasces, topped allegedly by an Etruscan axe-head, which one of its members managed to present to Mussolini in Rome during the May 1923 International Woman Suffrage Congress. The ploy didn’t work, and Italy’s new nickel coinage with an antiquarian-derived Roman fasces went into mass production in summer 1923.

“Mussolini seems to have been the first statesperson ever to interpret the fasces as an instrument for imposing political unity by means of authority.”

All that proved to be just the first strides of a 20-year program to makes the fasces ubiquitous in Italy and the territories it colonized in Africa. Mussolini’s regime’s relentless focus on the fasces, and propagation of the image on a massive scale (with individual items ranging in size from lapel pins to entire structures, including Florence’s train station) had no close parallel in world history—not in the Roman empire, where we never find the frightening image of a free-standing fasces on a coin, nor even in the feverish production of French Revolutionary iconography. Plus, Mussolini seems to have been the first statesperson ever to interpret the fasces as an instrument for imposing political unity by means of authority. (Everyone else had it the other way around.) It also was a special innovation of Mussolini to idealize the humble lictor who lugged the fasces and raise him to prominence. The not so subtle suggestion here was that all elements of Italian society should model their behavior on that of the lictor, and selflessly and energetically carry forward the standard of fascismo.

Post-war legacy of the fascesThe defeat of the Axis powers in 1945 sent the image of the fasces sharply in retreat—even in the United States, where soon after war’s end it was dropped from the long-established (since 1916) ten cent piece. However, Italy developed no master plan to address its now-ubiquitous Fascist symbols. Indeed, by 1953, its national Olympic committee was touting Rome’s ex-Foro Mussolini as an ideal site for the 1960 Summer Games. And once it won its bid, it made only a belated and feeble effort (quickly abandoned) to mitigate the effect of the hundreds of fasces embedded in the mosaic walkway that led to the principal stadium, which are still intact today. That said, in the post-World War II era—with the exception of a provocative twinned public sculpture by Scotland’s Alexander Stoddart (2001) on university campuses in Paisley and Princeton—no one has been putting up new fasces in public art.

Feature image: “Fascist parade: Benito Mussolini reviewing a military parade in Rome, December 3, 1940.” From Encyclopædia Britannica

October 20, 2022

When Ralph Bunche met Princess Margaret

In the fall of 1965, Queen Elizabeth’s younger sister, Princess Margaret, embarked on a charm offensive in a former—and now long-lost—British colony. Landing in San Francisco with some 50 pieces of luggage and her husband, Lord Snowden, the Princess wowed the nation, touring American cities and visiting President Lyndon B. Johnson and the First Lady “Lady Bird” in the White House. She then came to the United Nations for a series of meetings and a luncheon. Standing out in large cylindrical wool hat, pink dress, and long gloves, the princess mingled with diplomats at a reception hosted by the UK’s ambassador.

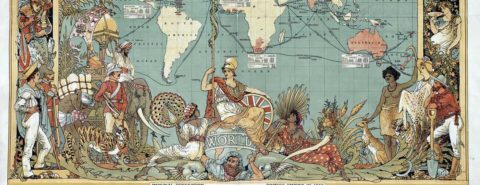

The reception, however, was boycotted by all the African states at the UN. Many newly-independent, these states sought to underscore Britain’s role in the controversial declaration of independence, just a week before, of white-dominated Rhodesia. Both Rhodesia and South Africa, former British colonies bent on maintaining white supremacy in Africa, were increasingly ostracized by the international community. To be sure, by Princess Margaret’s visit in 1965 the British Empire was a tiny vestige of what it once was. Yet, as the boycott showed, the legacy of British colonialism continued to be a source of great global conflict.

When the Queen and Margaret were children in the early 1930s, the British Empire stood at a peak and encompassed some half a billion people, perhaps a quarter of the world’s population at the time. The story of the empire’s rapid demise has many facets, but central to it is the crucial role of the UN. Though hardly intended to play this role by founders such as Winston Churchill, after the end of the Second World War the UN quickly became the site of intense and impactful anticolonial politics.

“Ralph Bunche … was above all a staunch anti-colonialist.”

Many individuals at the UN took part in the fight against empire. But perhaps most central, and certainly most striking, was one man, an American man, who nonetheless had long been fascinated by colonial rule, and indeed was one of the only Americans to actually study and live in colonial territories in the prewar heyday of empire. Ralph Bunche, perhaps most famous for his Nobel Peace Prize-winning mediation of the first Arab-Israeli conflict in 1949, was above all a staunch anti-colonialist. As one of the few Black graduate students at Harvard in the 1920s Bunche had studied colonial rule in Africa. At the State Department, during the Second World War, he helped develop the system of trusteeship that emerged at the UN to guide former colonies to independence. And at the UN itself Bunche was the architect of peacekeeping, a critical innovation that proved sadly essential for many postcolonial states as they were riven by conflict and contestation over power in the wake of their independence.

When Princess Margaret visited the UN in 1965, Ralph Bunche had ascended to the heights of the UN as Under-Secretary General. After the British royal couple left the somewhat fraught UK reception to attend a small lunch in the Dag Hammarskjold Library, Bunche, seeing the Princess standing by the window, went up to chat with her. He and his wife Ruth had travelled to Jamaica in 1962 for Jamaica’s independence from the UK and they had met Princess Margaret there in Kingston. (He later somewhat cattily noted in his diary that “she is rather affected but genuinely blasé I think” and her husband is “runt-sized.”) At the UN Bunche and Margaret had a conversation that illustrated the waning age of decolonization. Standing with the Princess, he told her that the colony of British Guiana was soon to become independent, probably in the spring of 1966. Princess Margaret replied that it was so small and poor, to which Bunche noted, “not as small as the last member we to welcomed into the UN, thanks to your government.” What nation was that, Margaret asked. The Maldive Islands, he replied. “Where are they?” replied Margaret. “That’s just it,” answered Bunche, “we didn’t even know.”

That even Princess Margaret could not keep track of the British territories left in the empire in the mid-1960s reflected both the once-vast size of Britain’s possessions but also that by this point in history the empire comprised mostly small and sunny vestiges of its former mastery of the seas. In the years to come Barbados, Bahrain, and the Bahamas, and at least a dozen more small island states, would all gain their freedom from British rule and join the UN as independent states.

“For Bunche, empire was a manifestation of white world supremacy, and the fight to end it a fight for global racial justice.”

Ralph Bunche was polite and friendly to Princess Margaret that day at the UN; he was a consummate diplomat and an engaging, easy-going person by nature. But like many around the world who have commented in the wake of Queen Elizabeth’s recent death, he likely saw the British Empire as one of the most troubling legacies of the House of Windsor. Bunche dedicated his career to ending colonialism; empire was, as he once said in a speech in Chicago in the mid-1950s, his “major preoccupation.” For Bunche, empire was a manifestation of white world supremacy, and the fight to end it a fight for global racial justice. Well before he left Howard University and entered the State Department in 1941, Bunche was a committed advocate for civil rights. He saw no tension in his dual commitment to civil rights and anticolonialism; indeed, he believed they were twinned movements aimed at the liberation of people of color.

Bunche, who died in 1971, did not live to see all the small remaining British colonies become sovereign states. (Indeed, not all have become independent even today.) But during his lifetime, and often through his efforts, many dozens of new states emerged from the ashes of European empire. When he began his career at the UN the organization’s membership stood at 50. By his death, there were some 132 member states. Today, there are nearly 200. That enormous growth represents the greatest revolution in world politics of the 20th century, and it was one that Ralph Bunche, standing at the apex of the UN in the 1950s and 1960s, helped shepherd to fruition.

Featured image: “Imperial Federation, map of the world showing the extent of the British Empire in 1886” by Walter Crane, via Wikimedia Commons, public domain

October 19, 2022

A year in review: Open Access at OUP

The open access landscape is fast evolving—and for good reason. Following the global outbreak of COVID-19 in which research and knowledge lay at the heart of hope, we have seen a renewed focus in the industry for open access (OA) publishing. Government-driven policies are being enhanced to increase public access to research, such as the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) update to its long-established 2013 memo on public access to federally funded research, and OA content continues to increase its share of the global scholarly publishing market.

In recognition of International Open Access Week, which this year runs between 24 and 30 October, we reflect on the progress that has been made at Oxford University Press and the people who have been influential in driving it. As the world’s largest university publisher of open access research and as a mission-driven organisation, we see “opening up” access to research as a vital part of how we disseminate knowledge. We are proud to be making significant contributions toward enabling greater access to academic research.

Currently, more than a third (36%) of our journal content is available OA—that’s without barriers to access or re-use—and we are working to see that number increase with new partnerships and through cooperation with the scholarly community by working with authors, society publishing partners, institutions, and funders to move towards an open world.

“Currently, more than a third of our journal content is available OA—that’s without barriers to access or re-use.”

Last year, we celebrated the significant milestone of 100,000 articles published OA. Since then, our teams have been busy launching new OA journals and books, signing Read and Publish agreements, and impacting government policy through the publication of critical research, all whilst ensuring our commitment to high-quality is maintained. Our rigorous editorial and peer review processes and our focus on publishing impactful research has led to mean lifetime citations for gold open access articles published in our journals reaching 29.34*—placing us in the top two of all major academic publishers.

Unlocking new publishing opportunitiesOver the past year, we have initiated a number of new publishing opportunities to further improve access to our scholarly content. As an example, we have increased our OA journal portfolio to 100 fully open access journals—a nearly 25% increase on last year—and expanded the number of hybrid journals offering authors the choice to publish OA to over 400. Launched in April 2020, our Oxford Open Journals series is underpinned by a set of guiding principles focused on open research, including open data and open peer review. The series now also includes Oxford Open Infrastructure and Health and Oxford Open Digital Health journals, bringing the total number of journals in the series to eight. You can read more from our Oxford Open Editors on this year’s Open Access Week theme of climate justice on the OUPblog.

In terms of journal flipping—a change that sees an existing journal move from a subscription-based closed access model, or similar, to OA—we have so far transitioned 16 journals, with the Journal of Plant Ecology and European Journal of Public Health having flipped to fully OA in 2022.

Likewise, we have seen notable growth in our books publishing, this year publishing 41 fully open access books and two with open access chapters, with our most read OA book so far being Cornerstones of Attachment Research, by Robbie Duschinsky.

This means more high-quality research, often published in partnership with global learned societies, is reaching a wider range of the academic community than ever before, benefiting our authors, those using our research, and wider society.

Read and PublishOur Read and Publish agreements help make OA publishing available to more authors worldwide. In addition to our existing Read and Publish deals ranging from the United States to China, this year saw us launch major new agreements in Australia and New Zealand, Italy, the UK, the US, Sweden, Spain, Cyprus, Croatia, and Lithuania, as well as with the Italian consortium of Biomedical Research Libraries (BIBLIOSAN) and Qatar National Library.

Greater author exposure“From Altmetric’s data, we know that authors publishing OA with OUP get more attention for their work.”

From Altmetric’s data, we know that authors publishing OA with OUP get more attention for their work. As of October 2022, 87% of OUP-published gold open access content gets mentioned online in comparison to 47% for closed access. Highlights from the mentions of gold-open access publications include:

1,129 mentions in policy documents, such as those from the World Health Organization, the United Nations, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 28,328 patents32,869 mentions in news outlets such as Aljazeera, Scientific American, Forbes, The Guardian, and National Geographic655,981 Twitter mentions. Impacting government policy and climate justiceIn line with this year’s open access theme—”open for climate justice”, which seeks to encourage connection and collaboration among the climate movement and the international open community—we are proud to have OUP OA research cited by key government bodies, including the WHO, EU, UN, the International Renewable Energy Agency, and Sweden’s Research Institute.

You can find some of the most influential climate and sustainability related articles on topics ranging from affordable clean energy to food environments below:

“Innovation policy and the market for vaccines“, Journal of Law and the Biosciences“Paths to low-cost hydrogen energy at a scale for transportation applications in the USA and China via liquid-hydrogen distribution networks”, Clean Energy“The impacts of COVID-19 on GDP, food prices, and food security”, Q Open“First Nations Food Environments: Exploring the Role of Place, Income, and Social Connection”, Current Developments in NutritionOur commitment to OA publishing is a key part of how we deliver on our mission to achieve the widest possible dissemination of high-quality research. It is this approach that steers our future direction and influences the way we work with authors, society publishing partners, institutions, and funders to maintain the highest quality research while creating a more open world for everyone.

As the open access landscape evolves, we will continue to be at the forefront of that change.

*Source: Dimensions, as of September 2022

Featured image by Tolga Aslantürk, via Pexels, public domain

Crabbed age and youth cannot live together, but crabs and scorpions can

The part of the title about crabbed age and youth is from Shakespeare’s poem The Passionate Pilgrim. His authorship of this poem has been questioned more than once, but we’ll let it be because at the moment we are interested only in the travels of crabs and scorpions across the language map, rather than literature, and your passionate pilgrim is the Oxford Etymologist.

Obviously, creak, croak, screech, scrape, and their likes are sound-imitative and occasionally sound–symbolic. Crabs crawl while other kr-creatures creep, and word roots beginning with kr– often have the variant skr– (the so-called s-mobile has often been mentioned in this blog). Such observations are trivial. The riddle is not the origin of such words but their similarity in at least half of the world. The crab, we are told, may have been named from its claws (see below). True enough. Crustaceans are usually clawy. Insects also know how to make us scratch. Scarabs provide another good example.

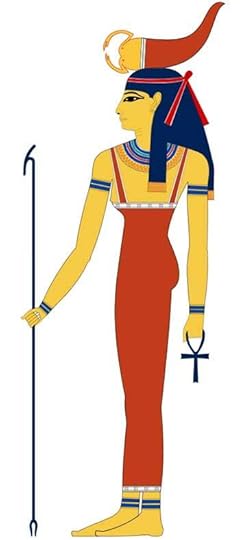

Serket, a theriomorphic goddess.

Serket, a theriomorphic goddess.(Image by Jeff Dahl, public domain)

How did the word crab and its likes spread so far? Where was the first such word coined? Classical Greek kárabos meant “crab.” In Ancient Egypt, there was a goddess called Serket. She controlled breath, and suffocating people stung by venomous insects invoked her when they lay in death throes. Later, she was associated and identified with scorpions. The root of Serket is (s)rk-. Did nouns with (s)rk– ~ (s)kr– in themoriginate in Egypt? I owe my knowledge of Serket and scorpions to a dissertation defended rather long ago in France. Many words and plots did spread from Egypt to Ancient Europe. For example, Egypt worshipped frogs. Millions of them appeared in bogs left at the flooding of the Nile and were venerated as symbols of abundance and fertility. The water goddess Heket was half-frog and half-woman (in this half-anthropomorphic [“having a human form”], half-theriomorphic [“having an animal form”] capacity she resembled Serket and several other deities and monsters, including Sphinx).

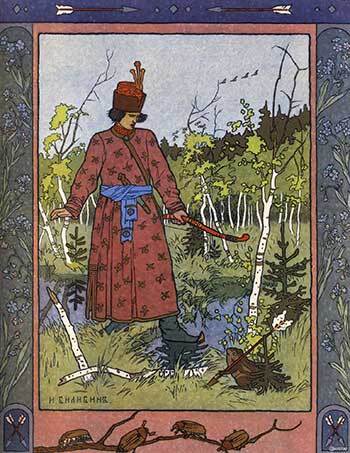

The knowledge of Heket reached Greece and Rome and survived in Europe in the form of a fairytale. In Russian folklore, the tale is known as “The Frog Princess” (with no traces of the ancient plot, except that a prince is destined to marry a frog). Similar versions have been recorded all over Europe. One of them reached Germany but in a hopelessly garbled form (perhaps via a mediaeval Latin text: in it, a princess marries a male frog (who, to be sure, when smashed against the wall, turns into a beautiful prince). The frog as a totem in Native American folklore may have had similar roots but the motif arose independently of its Old-World analog. If the frog could find a new home in Europe, why couldn’t the name of the (s)kr ~ (s)rk creature?

In Germanic, the familiar word for “crab” is ubiquitous. Such is German Krabbe “shrimp” (originally, a Low German form), Krebs “crab; crayfish ~ crawfish” (but more often used with the sense “cancer”). By the way, crayfish is an almost direct relative of German Krebs (that is, Middle High German krebiz). The German word was borrowed by French and later returned to its Germanic home, namely, Middle English. There, crevisse, by folk etymology, became cravish and (by the same trick) crafish; hence the American form crawfish. Each component of this story is trivial: Germanic words were often taken over by French and later borrowed by Middle English. Likewise, folk etymology produces the most outlandish creatures in all languages. A crab turns into a fish, and a squirrel becomes a horned creature on an oak (such is, for example, German Eich-hörnchen, literally, “oak-hornlet”). Dutch kreeft and Old Icelandic krabbi add nothing to what we already know.

The Frog Princess. Many trials and tribulations, but they hero and the heroine lived happily ever after.

The Frog Princess. Many trials and tribulations, but they hero and the heroine lived happily ever after.(By Ivan Bilibin, public domain)

Even if Ancient Egyptian Serket contains a variant of the same root as crab, its way from Egypt to Europe could not be straight. In 1926, the French linguist Marcel Cohen cited a long list of Semitic words that were strikingly similar to those cited above: Arabic caqrab “scorpion,” qaranbā “a kind of beetle’’ (almost the same form with n in the middle), qambri “shrimp” (the latter sounds almost like Greek kammoras ~ kammaras), and Latin cammaras. Cammaras also reached the Germanic-speaking lands. There, as usual, k became h, and we recognize the ancient word in French homard “lobster.”

Thus, scarab, scorpion, crab, and crayfish ~ crawfish emerge as cousins in a loose family of words. One can look at them from several points of view. For instance, Greek gráphein meant “to write,” but its original meaning was “to scratch” (many words for writing go back to some such notion). The Greek verb reminds one of scratching and scraping, though the relation between them and the crab group is not direct. A few Old Germanic verbs that sounded like gráphein and crab existed, and it has been suggested that the crab got its name from its claws. Though one can find this idea in several authoritative etymological dictionaries of Germanic languages, it is not quite persuasive, because it ignores the non-Indo-European words cited above.

It may be that skr- ~ kr– combinations evoked the same reaction in all places at all times. Perhaps we are dealing with the universal sound-symbolic group (s)kr that makes people think of scratching, and this is how the names of several insects and crustaceans came into being. Wilhelm Oehl, the Swiss etymologist to whose research I often refer in this blog, might have said so. But here too some dissatisfaction remains, because we are dealing with a bunch of animal names rather than with elementary verbs.

A crab and a scorpion: an unexpected alliance.

A crab and a scorpion: an unexpected alliance.(L: photo by Jonathan Wilkins, CC BY-SA 3.0. R: photo by Peter Prokosch, GRID Arendal, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Finally, it is equally probable that we have before us a migratory word (the German term is Wanderwort), once borrowed from a discoverable (Proto-Semitic?) source, and never staying in one place. This would be a satisfactory solution if we had to explain the origin ofa single word, for instance, crab. But scarabs and scorpions are not crabs! Nor did the Egyptian goddess have anything to do with crabs. Therefore, it would probably be reasonable to abstain from a binding solution. The facts are known, but the etymology of the words listed above still remains to a great extent unclear.

Now a few lines may probably be devoted to the odd adjective crabbed. As often before, I’ll quote from The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology: “CRAB + ED, with original reference to the gait and habits of the crab, which suggest cross-grained or fractious disposition; cf. for meaning Low German krabbe ‘cantankerous man’; krabbig ‘contentious, cross-grained’, and for formation dogged.” And here is our perennial authority Walter W. Skeat (I slightly edited the entry for style): “Crabbed, peevish, cramped…. From crab; that is, crab-like, snappish or awkward. Cf. Dutch krabben ‘to scratch’, kribben ‘to be peevish’.”

Dictionaries and the Internet give carefully worded explanations of the origin of crab apple, and I have nothing to add to the information found there (but see our image in the header!). However, if you are interested in the origin of the idiom to catch a crab, see the post for 21 September 2016 (“Sticking my oar in….”). I hope you will like that blog post even if your disposition is constitutionally cross-grained or fractious.

Featured image by Wehha via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0

October 18, 2022

Why we hate (and whether we can do something about it)

Human nature is a paradox. On the one hand, thanks to our evolution in the five million years since we left the jungle, we are a highly social species. We became bipedal, making it possible for us to become hunter-gatherers. We lived in bands of about fifty, generally far from other groups. Partly cause and partly effect, our brains started to grow. We developed features helpful for living together, like language, and did not develop (or lost) features not helpful for living together, like fangs and claws. On the other hand, as the last centuries show only too well, we can be truly hateful towards our fellow human beings—on a group level, war, and on an individual level, prejudice. Two horrendous world wars show that only too clearly. As do slavery, attitudes towards Black people; the Holocaust, hostility towards Jews; and restrictions on abortion, prejudice towards women.

Why do we have these two sides to our nature? Is it possible to mold that nature so hatred is diminished? The problem started with the advent of agriculture, about ten thousand years ago. Before that, there was no war. If another band was troubling you, you just pulled up stakes and moved on. There was violence within bands—killing the chap who pinched your mate, bumping off a resource-draining grandmother—but no systematic killing of one group by another. Then, with agriculture, there was a huge population explosion—many more mouths could be fed—and increasingly moving away was no longer an option. There was nowhere empty. In any case, one had unmovable asserts–crops and so forth. Systematic violence began.

Likewise with prejudice. You might or might not like people in another group, but they didn’t really bother you. The evolutionary emphasis was on ingroup solidarity rather than outgroup hostility. With agriculture, things changed. You could not get away from others, they threatened your ingroup solidarity, and so barriers were set up against others and prejudice began. Or, it was homegrown. In hunter-gatherer times, to use a normally offensive metaphor, you could not afford to have weak sisters. Everyone had to do their bit, if not out hunting then building traps for smaller animals. Then came agriculture. Not only did you get large families, but they were adaptatively advantageous. Working in the fields, tending the animals, processing the food. Women became baby machines, occupied with having and raising children, opening the way for men to take control of the groups.

“Our present situation is not a direct function of genetic changes, from peaceful to hateful, but a consequence of changed cultural circumstances.”

The essential point to be seized from all of this is that our present situation is not a direct function of genetic changes, from peaceful to hateful, but a consequence of changed cultural circumstances. As is stressed by evolutionary psychologists Leda Cosmides and John Tooby: “Our modern skulls house a stone age mind.” Expounding: “In many cases our brains are better at solving the kinds of problems our ancestors faced on the African savannahs than they are at solving the more familiar tasks we face in a college classroom or modern city.”

Is there a possibility of changing things and reducing war and prejudice? The reasons why we are in this difficulty suggest that there are ways that we can—as indeed we must—improve things. These ways will be cultural. No need for genetic reengineering. In the case of war, obviously, we need ways to avert the violence before it started. The First World War, for example, was much a function of the Kaiser and the Tsar being quite incompetent and unable to prevent their nations bumbling into conflict. The United Nations is hardly perfect but let us give it some credit. We had two world wars in the first half of the last century. We did not have a third world war in the second half.

Reducing prejudice depends on several factors. At the top of the list is increased knowledge. Africans were thought to be of inferior intelligence and that justified oppressing them. Slavery. However, evolutionary theory, backed by new techniques for ferreting out our past—the power of our knowledge about ancient DNA multiplies daily—tells us that there certainly are genetic differences between groups. Scandinavians are blond because that way they can more readily synthesize vitamin D, thanks to the sun. People of the Congo are dark, thanks to melanin, because they need protection from too much sunshine (UV radiation). But there is absolutely no reason to expect significant differences in intelligence and, given the intermixing of groups in the past thousands of years, much to lead us not to expect such differences. For all their claimed superiority to all other human beings, the English for instance are almost all (90%) descendants of intruders from the continent about 4,000 years ago—“Bell Beaker folk.” The people who built Stonehenge are not the people living around it today.

“Reducing prejudice depends on several factors. At the top of the list is increased knowledge.”

The most interesting and promising example of the way in which changes in culture can change prejudicial attitudes is with respect to women. Two factors have significantly raised their prospects. First, the advent of labor-saving devices. Around 1950, thanks to our new Bendix washing machine, my mother changed from weekends bent over the washing tub, to weekends spent reading, discussing, and writing. Second, the advent of the contraceptive pill. Suddenly, young women had as much control over their sexual lives as young men. And, very obviously, the changes have been significant. In 1965, I started teaching at the University of Guelph in Canada. One of our academic units was the Ontario Veterinary College. Back then, it had an annual intake of 80 men and a quota of four women. When I left, in 2000, the annual intake was 100 students, over 90 of whom were women. Some change is progress!

Without being Pollyannas, there is ground for optimism. Natural selection left us open for culture to make a mess of everything. Natural selection left us with the abilities to change culture for the better. No one—except perhaps hippies left over from the sixties—is arguing for a return to a hunter-gatherer life-style complete with Birkenstocks! We must show that we have the ability and will to use culture for our desired ends, rather than passively letting culture have its way, regardless of what we want or need.

Featured image by Aarón Blanco Tejedor on Unsplash, public domain

October 16, 2022

Nine new books to understand the Cold War [reading list]

This October marks the 60th anniversary of the Cuban Missile Crisis, a tense political and military standoff between the United States and the Soviet Union at the height of the Cold War.

To mark the anniversary, we’re sharing some of our latest history titles on the Cold War for you to explore, share, and enjoy. We have also granted free access to selected chapters, for a limited time, for you to dip into.

1. The Cold War: A Very Short Introduction by Robert J. McMahonThe Cold War dominated international life from the end of World War II to the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. But how did the conflict begin? Why did it move from its initial origins in post-war Europe to encompass virtually every corner of the globe? And why, after lasting so long, did the war end so suddenly and unexpectedly? Robert McMahon considers these questions and more, as well as looking at the legacy of the Cold War and its impact on international relations today.

Read a free chapter: From confrontation to détente, 1958–68

2. Little Cold Warriors: American Childhood in the 1950s by Victoria M. Grieve

2. Little Cold Warriors: American Childhood in the 1950s by Victoria M. GrieveBoth conservative and liberal Baby Boomers have romanticized the 1950s as an age of innocence—of pickup ball games and Howdy Doody, when mom stayed home, and the economy boomed. These nostalgic narratives obscure many other histories of postwar childhood, one of which has more in common with the war years and the sixties, when children were mobilized and politicized by the US government, private corporations, and individual adults to fight the Cold War both at home and abroad.

Read a free chapter: Introduction

3. Imagining the World from Behind the Iron Curtain: Youth and the Global Sixties in Poland by Malgorzata FidelisThe Global Sixties are well known as a period of non-conformist lifestyles, experimentation with consumer products and technology, counterculture, and leftist politics. But contrary to public perception, the Iron Curtain was hardly a barrier against outside influences, and young people from students and hippies to mainstream youth in miniskirts and blue jeans saw themselves as part of the global community of like-minded people as well as citizens of Eastern Bloc countries.

Read: Imagining the World from Behind the Iron Curtain

4. News from Moscow: Soviet Journalism and the Limits of Postwar Reform by Simon Huxtable

4. News from Moscow: Soviet Journalism and the Limits of Postwar Reform by Simon HuxtableNews from Moscow is a social and cultural history of Soviet journalism after World War II. Focusing on the youth newspaper Komsomol’skaia Pravda, the study draws on transcripts of behind-the-scenes editorial meetings to chart the changing professional ethos of the Soviet journalist.

Read a free chapter: Introduction: Reformers and Propagandists

5. The Human Factor: Gorbachev, Reagan, and Thatcher, and the End of the Cold War by Archie BrownWhy did the Cold War end when it did? Few questions have generated more heated debate over the course of the last three decades. Archie Brown, one of the foremost experts on the subject, shows why the popular view that Western economic and military strength left the Soviet Union with no alternative but to admit defeat is erroneous.

Read: The Human Factor, now new in paperback (UK edition | US edition)

6. Velvet Revolutions: An Oral History of Czech Society by Miroslav Vanek and Pavel Mücke

6. Velvet Revolutions: An Oral History of Czech Society by Miroslav Vanek and Pavel MückeThe Velvet Revolution in November 1989 brought about the collapse of the authoritarian communist regime in what was then Czechoslovakia, marking the beginning of the country’s journey towards democracy. Velvet Revolutions examines the values of everyday citizens who lived under so-called real socialism, as well as how their values changed after the 1989 collapse.

Read: Velvet Revolutions

7. Flowers Through Concrete: Explorations in Soviet Hippieland by Juliane FürstFlowers through Concrete takes readers on a journey into a world few knew existed: the lives and thoughts of Soviet hippies, who in the face of disapproval and repression created a version of Western counterculture, skilfully adapting, manipulating, and shaping it to their late socialist environment. As a quasi-guide into the underground hippieland, readers are situated in the world of hippies firmly in late Soviet reality and are offered an unusual history of the last Soviet decades as well as a case study in the power of transnational youth cultures.

Read: Flowers Through Concrete, now new in paperback

8. Race for Revival: How Cold War South Korea Shaped the American Evangelical Empire by Helen Jin Kim

8. Race for Revival: How Cold War South Korea Shaped the American Evangelical Empire by Helen Jin KimIn 1973, Billy Graham, “America’s Pastor,” held his largest ever “crusade.” But he was not, as one might expect, in the American heartland, but in South Korea. Why there? Race for Revival seeks not only to answer that question, but to retell the story of modern American evangelicalism through its relationship with South Korea. With the outbreak of the Korean War, the first “hot” war of the Cold War era, a new generation of white fundamentalists and neo-evangelicals forged networks with South Koreans that helped turn evangelical America into an empire.

Read a free chapter: Introduction

9. Afghan Crucible: The Soviet Invasion and the Making of Modern Afghanistan by Elisabeth LeakeOn 24 December 1979, Soviet armed forces entered Afghanistan, beginning an occupation that would last almost a decade and creating a political crisis that shook the world. To many observers, the Soviet invasion showed the lengths to which one of the world’s superpowers would go to vie for supremacy in the global Cold War. The Soviet war, and parallel covert American aid to Afghan resistance fighters, would come to be a defining event of international politics in the final years of the Cold War, lingering far beyond the Soviet Union’s own demise. Yet Cold War competition is only a small part of the story.

Read: Afghan Crucible

For more titles on the Cold War, visit our website.

Feature image: Fallout shelter sign by Burgess Milner. Public domain via Unsplash .

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers