Oxford University Press's Blog, page 58

February 1, 2023

Etymology gleanings for two winter months (2022-2023)

Etymology gleanings for two winter months (2022-2023)

Occasionally I receive letters from our readers, and from time to time, comments follow a post, but I have recently put together a book based on this blog and while working on it, reread everything I have written since 1 March 2006, the day The Oxford Etymologist was launched. It is amazing how much richer my mail was fifteen, ten, and even five years ago. I used to “glean” my field once a month and return with a full load of etymological grain. Nowadays, I do not always have enough even after two months. Fortunately, when I make a mistake, someone always notices it. Every sign of life is welcome, and many thanks to such attentive readers. I am also grateful to those who occasionally write kind words about my short essays. Praise is a rare coin, and like most people, I prefer appreciation to abuse. Discussion of idioms seems to interest especially many people. But now that the University of Minnesota Press has brought out a cheap paperback (Take My Word for It), my explanatory and etymological dictionary of English idioms, there is no point in returning to this subject, unless someone sends a question about a puzzling phrase.

Words multiplying like mushroomsA reader called my attention to the Hebrew word uhushboo-ot “a plague of boils” (Exodus 9; 2 and 10) and cited Latin būbō “swelling” and “owl.” The first sense was borrowed from Greek. The question was whether the similarity between Hebrew and Greek is the result of borrowing, and if so, from which language to which. One should add that at least some words belong to the common Indo-European and Semitic stock (those interested in this subject should consult the works by Saul Levin). It also seems that būbō1 and būbō2 are homonyms. In any case, in the Latin dictionary by Ernout-Meillet, they are given as two separate entries. Not being a specialist in Hebrew or Greek, I can only say that the word for “owl” is undoubtedly sound-imitating, like, for example, German Uhu “eagle-owl.”

This is a baboon. Sound-symbolic to us, it is perfectly natural to itself.

This is a baboon. Sound-symbolic to us, it is perfectly natural to itself.(By X posid, public domain)

Whether the name of the disease is sound-imitating (so in Ernout-Meillet) is less clear, but for curiosity’s sake, I may cite the Indo-European root beu-, allegedly alternating with bheu-, found in words “loosely associated with swelling” (note that Indo-European b became p in Germanic, while bh– yielded b): pock, poke; bosom, big, bucket, buckle, boil, boast; bullet, and so forth. It is most probable that the idea of swelling does underlie the words cited above and quite a few more that I did not include in my list. But reference to a root like this can only mean that when people coined words referring to something big and round, they intuitively chose the complex bo– or boo– and produced more and more nouns and verbs. Besides, sound complexes like bobo and booboo are rather typical baby words, like the noun baby itself, and reference to babbling and baby language also occurs in a search for the origin of some b-b “complexes,” from baboon to bubble (bubble is perhaps sound-imitative, rather than sound-symbolic). The question about borrowing such “universal” words poses obvious difficulties.

In connection with my previous post on gr-words as mushrooms (25 January 2023), my colleague and friend Victor Fet reminded me of grok and of Danish rhyming aphorisms called grooks. He is especially fond of such coinages because of his lifelong interest in Lewis Carroll and his neologisms. Grok is now ubiquitous. Both words (see them in Wikipedia) are classic examples of sound symbolism. Of course, I knew them but did not want to overload my post with too many examples. By the way, the inventors of such neologisms (even they!) are sometimes unable to explain how they coined them.

This is a common problem with sound symbolism. Sound imitation is obvious. When someone says gr-gr, to frighten people (as one of the shopkeepers in Dickens’s David Copperfield did), there is nothing to explain, but sound symbolism seems to be realized in retrospect. It is a case of guilt by association. Nothing in the English consonantal group sl– suggests disgust, but the accumulation of words like slum, slops, slime, and sleazy colors our understanding of slack, sleuth, slattern, slippery, and the rest. Yet we have nothing against slippers, slings, and slender people. That is why reference to sound imitation in etymology arouses no objections, while sound symbolism is too evasive to clinch any argument in a search for word origins.

We like slender people, don’t we?

We like slender people, don’t we?(“Ida Rubinstein” by Valentin Serov, 1910, Google Art Project, public domain)English mo(u)ld ~ mildew and Greek

Mo(u)ld is an ancient word. Its cognates occur all over the Germanic-speaking word. Even Gothic mulda “dust” has been recorded. We have here a rather transparent noun with the suffix –d. Its quite probable cognate is Greek amalós “soft” (in its Latin shape, the root is known to English speakers from the verb mollify). Therefore, in mo(u)ld, we are dealing with related forms, rather than with a borrowing (however ancient) into Germanic from Greek.

Strawberry: etymologySee my post for 1 April 2015. Recently, a correspondent cited Icelandic strá “straw of grass” as a possible clue to the English word. William Sayers, an unimaginably prolific author (a list of his publications can be found online), offered an etymology (mentioned in my post), which is neither better nor worse than a few older ones. No one has explained why English replaced the traditional Germanic word for this fruit (earth-berry) by a new one. Without this explanation, that is, without reference to some event in real life, all the hypotheses will remain exercises in intelligent guessing. Children sometimes collect strawberries on straws. Do we need this tip?

Strawberries indeed!

Strawberries indeed!(Public domain)Three puzzles

Editor’s note: explicit language

A Dublin newspaper for 1780s mentioned pinkerdindies, which referred to gangs or perhaps a drinking club. Predictably, in my database, I was unable to find references to this word’s origin. But I wonder whether dandy (a Scottish word) provides a clue to dindies. (In the vocabulary, what is Scottish is often also North Irish.) The origin of dandy (also a Scottish word?) is obscure, though a good deal has been written about it. However, here we are interested not in the history of dandy but only in whether there may be some connection between dandy and dindy. Such a vowel change is not unthinkable in slang. Pinker is an occupational term. Websites gloss it as “butler” (not in Jamieson). Or there could be an obscure reference to the name Pinkerton.Cunt as an animal name (“mole”). Not in any regional dictionary I have consulted. Moles are called boars (males) and sows (females). A group of moles is a labo(u)r. I suspect that the usage our correspond found (from ?female mole to cunt) is idiosyncratic: a humorous individual coinage.Why do we say a pounce of cats? Pounce is a synonym of talon “a claw of a bird of prey.” Probably pounce in a pounce of cats, refers to cats’ claws.Featured image: “The plague in Winterthur in 1328.” Lithograph by A. Corrodi, Wellcome Trust via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 4.0)

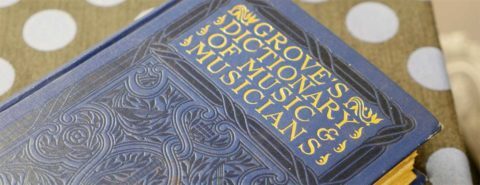

Grove Music’s 2023 spoof article contest is now open!

Grove Music’s 2023 spoof article contest is now open!

I am pleased to announce the semi-annual Grove Music Online spoof article contest is now open for 2023!

Spoof articles have had a long history within Grove Music. Grove’s particular style and format have long inspired parodies of all kinds. Last year, David W. Barber won with a spoof on “Bach, Ludwig Odense Lämmerhirt,” and Robert Stein was commended for a spoof entry on “La Sorella della Principessa di Malta.”

This year’s winner will receive a one-year subscription to Grove Music Online and $100 in OUP books.

Submission guidelines:Entries should be no longer than 300 words.Entries will be judged by Grove Music’s Editor in Chief Deane Root, Acquisitions Editor Scott Gleason, and a guest to be named later.Judges will consider the following criteria:Does the article adhere to Grove style?Is it entertaining?Could it pass for a genuine Grove article?Send submissions by email to GroveMusic.Editor@oup.com as follows.Subject should read “Grove Music fake article contest-[title]”.In the body of the email, include the title of the article and your full name and contact information (street address, email, phone).Include the entry in an attached document. Do not include your name. This is to facilitate blind judging.You may send as many as three articles, but please send each submission separately. No more than three entries will be accepted from a single author.All submissions must be received by 23:59 EST on 28 February 2023. Manuscripts received after that time will not be considered.

The winning article(s) will be announced on 1 April 2023 on the OUPblog.The winner will receive USD100 in OUP books, a year’s personal subscription to Grove Music Online, and bragging rights. There is no cash alternative, and the prize is not transferable.We reserve the right not to award a prize if we feel the submissions do not meet our criteria.January 31, 2023

Mind the gap: the growth in economic inequality [podcast]

Mind the gap: the growth in economic inequality [podcast]

The world is navigating a troubling economic situation. Inflation has become a global issue, concerning policy makers and private citizens equally. Energy and supply chains woes are continuous. Interest rates, consumer prices, and cost-of-living have soared, with many economists positing that the current trajectory is indicative of a coming recession.

Amid these crises, how do we recover? How can we address such financial distress and inequity, and how might we go about enacting more permanent resolution?

On today’s episode, the first for 2023, we spoke with Chris Howard, author of Who Cares: The Social Safety Net in America, and Tom Malleson, author of Against Inequality: The Practical and Ethical Case for Abolishing the Superrich, on the social safety net, the ethical implications of extreme wealth, and what steps can be taken to achieve economic equality.

Check out Episode 79 of The Oxford Comment and subscribe to The Oxford Comment podcast through your favourite podcast app to listen to the latest insights from our expert authors.

Oxford Academic (OUP) · Economic Inequality – Episode 79 – The Oxford CommentRecommended readingIf you would like to find out more about the social safety net in America, we’ve made the introduction to Chris Howard’s new book, Who Cares: The Social Safety Net in America free for 3 months.

Before writing Against Inequality, Tom Malleson argued on behalf of economic democracy in After Occupy: Economic Democracy for the 21st Century. Its first chapter, also free for 3 months, can be found here. Tom also co-wrote Part-Time for All: A Care Manifesto with Jennifer Nedelsky, which proposed a plan to radically restructure both work and care.

We’ve freed Gøsta Esping-Andersen and John Myles’ chapter, “Economic Inequality and the Welfare State“, from The Oxford Handbook of Economic Inequality (edited by Brian Nolan et al), which discusses the difficulties of capturing the impact of the welfare state on income inequality.

For further reading on economic inequality, social welfare, power dynamics, neoliberalism, and democratic socialism, check out these recent OUP titles:

Transnational Social Protection: Social Welfare across National Borders by Peggy Levitt, Ken Chih-Yan Sun, Ruxandra Paul, and Erica DobbsThe New Power Elite by Heather GautneyDisorienting Neoliberalism: Global Justice and the Outer Limit of Freedom by Benjamin L. McKeanWould Democratic Socialism Be Better? by Lane KenworthyLastly, check out these Open Access journal articles and book chapters, which can all be found on Oxford Academic:

“Introduction: Why Do Governments Struggle to Reduce Inequalities?” from Public Policy to Reduce Inequalities across Europe: Hope Versus Reality (August 2022) by Paul Cairney, Michael Keating, Sean Kippin, and Emily St Denny“Bringing the market in: an expanded framework for understanding popular responses to economic inequality” by Arvid Lindh and Leslie McCall in Socio-Economic Review, April 2022“‘It’s the value that we bring’: performance pay and top income earners’ perceptions of inequality” by Katharina Hecht from Socio-Economic Review, October 2021“On the Impact of Inequality on Growth, Human Development, and Governance” by Ines A Ferreira, Rachel M Gisselquist, and Finn Tarp from International Studies Review, January 2021“Billionaires” by Tino Sanandaji and Peter T. Leeson from Industrial and Corporate Change, January 2013Featured Image: Towfiqu barbhuiya, CC0 via Unsplash.

January 30, 2023

Charity and solidarity! What responsibilities do nonprofits have towards Ukraine?

Charity and solidarity! What responsibilities do nonprofits have towards Ukraine?

In a speech to the UN General Assembly in the fall of 2022, President Biden called on the UN to stand in solidarity with Ukraine. At least 1,000 companies have left Russia because of Putin’s brutal unprovoked war on Ukraine. Some companies left because of sanctions. Others left for moral reasons, often under pressure from investors, consumers, and out of empathy with their employees in Ukraine. But companies also have human rights responsibilities. Whether they stay or leave Russia will impact the war and human rights of the people of Ukraine. When companies leave en masse, Russia faces the possibility of economic oblivion.

Nonprofits can also impact the war. Russian oligarchs have donated lots of money to cultural organizations, universities, and think tanks, such as Harvard, MOMA, and the Council on Foreign Relations. Many of these donations are tainted by corruption and the close ties oligarchs have with Putin.

Philanthropy is a common way for oligarchs to launder their reputations, sometimes with an eye to future wrongdoing, what social psychologists call moral licensing. Studies show that people often follow their good acts with bad acts as a way to balance out the good with the bad. In the end, whatever good oligarchs do through their giving may be outweighed by the bad they’ve done in the past or will do in the future. But oligarchs are only part of the problem. Nonprofits that solicit and accept their donations are complicit in those harms, too.

What are the responsibilities of nonprofits? How should they meet their moral and human rights responsibilities during Russia’s war on Ukraine? What should we expect from museums, universities, and cultural organizations? If anything, they should be held to a higher standard than for-profit enterprises. After all, nonprofits serve the public good. They may not have had a physical presence in Russia, the way Starbucks and Levi Strauss did, but many of them are connected to Putin by way of Russian oligarchs.

How are nonprofits connected to Russia’s oligarchs?“Philanthropy is a common way for oligarchs to launder their reputations, sometimes with an eye to future wrongdoing.”

Consider Viktor Vekselberg, a prominent Russian oligarch with close ties to Putin and head of the Skolkovo Foundation. Like many Russian oligarchs, he made his money with the collapse of the Soviet Union. The Skolkovo Foundation donated over $300 million to Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) to support Skoltech, a program aimed at developing Russia’s tech sector. Vekselberg also sat on MIT’s Board of Trustees. It was only in 2018, after the US Treasury sanctioned him for “malign activities,” that MIT found the wherewithal to remove him from the Board. And, it was not until Russia invaded Ukraine that MIT ended the Skoltech Program, explaining, “this step is a rejection of the actions of the Russian government in Ukraine.” MIT finally got it right. Donors, such as Vekselberg, implicate nonprofits in Russia’s war on Ukraine. But had MIT done its due diligence from the outset, it would not have accepted Vekselberg’s donation in the first place. Boycotting oligarchs shows solidarity with the people of Ukraine, while doing nothing renders nonprofits complicit in the human rights violations suffered in Ukraine.

Vladimir Potanin, Russia’s richest oligarch, has supported the Kennedy Center and the Guggenheim Museum, among others. Until recently, he sat on the Board of Trustees at the Guggenheim, and on the Advisory Board of the Council of Foreign Relations. Potanin resigned from both in April 2022. Although not a Russian citizen, Len Blavatnik is a Russian insider who donated millions of dollars to Oxford, the Tate Modern, Yale, Harvard Medical School, and the Council of Foreign Affairs, to name a few of the elite recipients of his philanthropy. Aaron Ring, a Yale professor who received support from the Blavatnik Fund, called on Yale to suspend the Program. He was concerned that Yale was endorsing the donor. Yale maintained that since Blavatnik had not been sanctioned, his donation could be accepted. During Russia’s war on Ukraine, stakeholders like Aaron Ring don’t want to benefit from Russia’s oligarchs. They want to stand in solidarity with Ukraine.

How are nonprofits implicated in Russia’s human rights violations?The Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights were endorsed by the UN Human Rights Council in 2011. They hold that enterprises are responsible not only for their direct human rights violations, but also for their indirect ones. So, what counts as an indirect violation in the nonprofit sector? When a nonprofit benefits from donors who are implicated in human rights violations, the nonprofit is complicit in the wrongs of the donors. Many Russian oligarchs are tied to Putin, have profited from their relationship with him, and stand to benefit from his war on Ukraine.

“Boycotting oligarchs shows solidarity with the people of Ukraine, while doing nothing renders nonprofits complicit in the human rights violations suffered in Ukraine.”

When nonprofits refuse to accept donations from oligarchs, they stand in solidarity with Ukraine against Russia. Given the tendency of oligarchs to donate to elite and high-profile organizations, boycotting them may create a bandwagon effect, or a little philanthropy warfare!

Russia has a long record of human rights violations. Freedom of expression is one. The Committee to Protect Journalists confirmed that 82 journalists and media workers were killed in Russia between 1992 and 2022. In 2020, Russia adopted a law banning so called “disrespect” to authorities. Its violation of the fundamental rights of LGBTQ people is longstanding. In 2013, it penalized so called “propaganda” about homosexuality. Activists and celebrities faced fines for supporting the LGBTQ community in Russia.

Now, Russia is under investigation for war crimes such as rape, torture, and execution style murders of civilians. As of 2022, the UN General Assembly resolved that Russia should withdraw its military forces from Ukraine. This came amidst reports of Russian attacks on residences, schools, hospitals, and on civilians, including women, people with disabilities, and children.

Have nonprofits done enough for human rights?Have nonprofits done enough for human rights? No, not when it comes to Russian oligarchs. By laundering the reputations of oligarchs, nonprofits have enabled Putin’s war on Ukraine and the horrific suffering it has brought. The Guiding Principles can help nonprofits identify their human rights responsibilities and ensure that they are not complicit in Russia’s human rights violations. All enterprises should practice due diligence, a mechanism that prevents human rights violations and complicity in them. Refusing donations from Russian oligarchs is the very least nonprofits can do.

Transparency is at the heart of due diligence. Yale Professor Jeffrey Sonnenfeld has tracked which companies left Russia and which have stayed, providing much-needed transparency on the operations of for-profit enterprises. Not only does Sonnenfeld’s list incentivize companies to pull out of Russia, those that left have outperformed those that remained. Unfortunately, no such list exists for nonprofits. Tracking nonprofits with respect to Russian oligarchs, knowing and showing, would go a long way toward ensuring that they meet their human rights responsibilities.

To be sure, there is a risk that nonprofits will receive less money if they boycott Russian oligarchs. But it is also possible that they will be rewarded for doing the right thing, as Hands on Hartford was when it refused donations from the Proud Boys, a white supremacist group. Generous donors may come forward when they learn that nonprofits stand in solidarity with Ukraine. Granted, the impact nonprofits can have on the war in Ukraine is not as great as for-profit companies, if only because of scale. But keep in mind that nonprofits serve the public good, which if anything enhances their human rights responsibilities. In the long run, when nonprofits stand in solidarity with Ukraine, they serve the public good.

Featured image by Elena Mozhilov via Unsplash (publish domain)

January 27, 2023

A Q&A with Bryan Garner, “the least stuffy grammarian around”

A Q&A with Bryan Garner, “the least stuffy grammarian around”

The fifth edition of Garner’s Modern English Usage has recently been published by OUP. I was happy to talk to Bryan Garner—who has been called “the least stuffy grammarian around” and was declared a “genius” by the late David Foster Wallace—about what it means to write a usage dictionary.

What possesses someone to undertake a usage dictionary?“Possesses” is a good word for it. In my case, it was matter of falling in love with the genre as a teenager. I discovered Eric Partridge’s Usage and Abusage (1942) and immediately felt that it was the most fascinating book I’d ever held. Partridge discussed every “problem point” in the language—words that people use imprecisely, phrases that professional editors habitually eliminate, words that get misspelled because people falsely associate them with similar-looking words, the common grammatical blunders, and so on. And then Partridge had essays on such linguistic topics as concessive clauses, conditional clauses, elegancies, hyphenation, negation, nicknames, and obscurity (“It may be better to be clear than clever; it is still better to be clear and correct.”).

At the age of 16, I was going on a ski trip with friends, and the book had just arrived in the mail as I was leaving for New Mexico. I stuck it in my bag and didn’t open it until we arrived at the ski lodge. Upon starting to read it, I was hooked. In fact, I didn’t even ski the first day: I was soaking up all that I could from Usage and Abusage, which kept mentioning some mysterious man named Fowler.

So when I got home, I ordered Fowler’s Modern English Usage (2d ed. 1965), and when it arrived I decided it was even better. By the time I was 17, I’d memorized virtually every linguistic stance taken by Partridge and Fowler, and I was thoroughly imbued with their approach to language. By the time I’d graduated from high school, I added Wilson Follett, Bergen Evans, and Theodore Bernstein to the mix. I was steeped in English usage—as a kind of closet study. I spent far more time on these books than I did on my schoolwork.

I suppose in retrospect it looks predictable that I’d end up writing a usage dictionary. I started my first one (A Dictionary of Modern Legal Usage) when I was 23, and I’ve been at it ever since. That was 41 years ago, and it ended up being my first book with Oxford University Press.

There must be a further backstory to a teenager who suddenly falls in love with usage books. What explains that?You’re asking me to psychoanalyze myself? Okay, it’s true. When I was four, in 1962, my grandfather used Webster’s Second New International Dictionary as my booster seat. I started wondering what was in that big book.

Then, in 1974, when I was 15, one of the most important events of my life took place. A pretty girl in my neighborhood, Eloise, said to me, with big eyes and a smile: “You know, you have a really big vocabulary.” I had used the word facetious, and that prompted her comment.

It was a life-changing moment. I would never be the same.

I decided, quite consciously (though misguidedly), that if a big vocabulary impressed girls, I could excel at it as nobody ever had. By that time, my grandparents had given me Webster’s Second New International Dictionary, which for years had sat on a shelf in my room. I took it down and started scouring the pages for interesting, genuinely useful words. I didn’t want obsolete words. I wanted serviceable words and remarkable words. I resolved to copy out, by hand, 30 good ones per day—and to do it without fail.

“I decided, quite consciously (though misguidedly), that if a big vocabulary impressed girls, I could excel at it as nobody ever had.”

I soon discovered I liked angular, brittle words, such as cantankerous, impecunious, rebuke, and straitlaced. I liked aw-shucks, down-home words, such as bumpkin, chatterbox, horselaugh, and mumbo-jumbo. I liked combustible, raucous words, such as blast, bray, fulminate, and thunder. I liked arch, high-toned words, such as athwart, calumny, cynosure, and decrepitude. I liked toga-wearing, Socratic-sounding words, such as eristic, homunculus, palimpsest, and theologaster. I liked mellifluous, polysyllabic words, such as antediluvian, postprandial, protuberance, and undulation. I liked the technical and quasi-technical terms of rhetoric, such as asyndeton, periphrasis, quodlibet, and synecdoche. I liked frequentative verbs with an onomatopoetic feel, such as gurgle, jostle, piffle, and topple. I liked evocative words about language, such as billingsgate, logolatry, wordmonger, and zinger. I liked scatological, I-can’t-believe-this-term-exists words, such as coprolalia, fimicolous, scatomancy, and stercoraceous. I liked astonishing, denotatively necessary words that more people ought to know, such as mumpsimus and ultracrepidarian. I liked censoriously yelping words, such as balderdash, hooey, pishposh, and poppycock. I liked mirthful, tittering words, such as cowlick, flapdoodle, horsefeathers, and icky.

In short, I fell in love with language. I filled hundreds of pages in my vocabulary notebooks.

In the end, I decided that I liked the word lexicographer better than copyist, so I tried my hand at it.

What about Eloise? Did she respond well?I was trying to impress her, it’s true. I never called her. I just started using lots of big words. It took me about two years to realize that big words, in themselves, have no intrinsic value in attracting females. Perhaps the opposite.

But that’s okay. By the time I was 17, I had this prodigious vocabulary. I thought of SAT words as being quite elementary. I had a larger vocabulary then than I do today. You can see why, at the ski lodge in early 1975, this particular teenager was absolutely primed to relish the work of Eric Partridge and H.W. Fowler.

You’re not limited to English usage, are you? You’ve written other language-related books—what, 28 of them with different publishers?That’s true. But it all began with words and English usage. Then I moved to legal lexicography and other language-related topics.

Many if not most lexicographers today are interested in slang, in current catchphrases, and in jargon—the more shifting and volatile parts of language. (Always something new!) I’m different. I’ve always been interested in the durable parts. In my usage book, I tackle the difficult question of what, precisely, constitutes Standard Written English. In any era, that’s a complicated question or series of questions. And so I’ve answered it in a 1,200-page book, word by word and phrase by phrase. It’s intended for writers, editors, and serious word lovers.

Bryan Garner, author of Garner’s Modern English Usage, Fifth EditionWithin Garner’s Modern English Usage, you intersperse essays of the kind you mentioned earlier, don’t you?

Bryan Garner, author of Garner’s Modern English Usage, Fifth EditionWithin Garner’s Modern English Usage, you intersperse essays of the kind you mentioned earlier, don’t you?Of course. I’m very Fowlerian and Partridgean in my mindset. Though all my essays are original, some bear the same category-titles as Fowler’s (for example, “Archaisms,” “Needless Variants,” and “Split Infinitives” ) or Partridge’s (“Clichés,” “Johnsonese,” and “Slang” [yes, that]). Meanwhile, I’ve created new essay-categories of my own, much in the mold of my admired predecessors: “Airlinese,” “Estranged Siblings,” “Hypercorrection,” “Irregular Verbs,” “Skunked Terms,” “Word-Swapping,” and the like). I have a dozen new essays in the fifth edition, including “Irreversible Binomials,” “Loanwords,” “Prejudiced and Prejudicial Terms,” “Race-Related Terms,” and “Serial Comma” (a big one). These essays are some fun.

You also have lots of new short entries, don’t you? Didn’t I read that there are 1,500 of them?Yes, something like that. Consider an example. Note that an asterisk before a term denotes that it’s nonstandard:

At the ends of your entries, you include ratios about relative frequency in print.

tic-tac-toe (the elementary game in which two players draw X’s or O’s within a pattern of nine squares, the object being to get three in a row), a phrase dating from the mid-1800s in AmE, has been predominantly so spelled since about 1965. Before that, the variants *tick-tack-toe, *ticktacktoe, and even *tit-tat-toe were about equally common. The British usually call the game noughts and crosses.

Current ratio (tic-tac-toe vs. *tit-tat-toe vs. *tick-tack-toe vs. *ticktacktoe): 96:4:3:1

There are thousands of such entries. As you can see, a usage-book entry is entirely different from a normal dictionary entry.

Yes. Those are key. I’m capitalizing on big data, which makes GMEU entries empirically grounded in a way that earlier usage books couldn’t be. This is a great era for lexicographers and grammarians: we can assess word frequencies in various databases that include millions of published and spoken instances of a word or phrase. By comparison, the evidence on which Fowler and Partridge based their opinions was sparse. In my case, opinion is kept to a minimum, and facts come to the fore. Sometimes that entails inconveniently discovering that the received wisdom has been way off base.

Some people ask why we need a new edition of Garner’s Modern English Usage after only six years.“People who say they’re sticking to the original Fowler might as well be driving an original Model-T.”

I’ve heard that. It’s a naive view. For one thing, the empirical statistics on relative word frequencies have been updated from 2008 to 2019. The language has evolved: email is now predominantly solid. There are thousands of updated ratios, and some of the judgments differ from those in past editions. For example, overly and snuck are now declared to be unobjectionable.

Every single page of the book has new material. It’s a big improvement. The six years have allowed for much more research.

People who say they’re sticking to the original Fowler might as well be driving an original Model-T.

Here’s something reference books have in common with medical devices. There’s no reason for a new one unless it’s a significant improvement over its precursors. That’s how the field gets better and better.

The book has been praised as “a stupendous achievement” (Reference Reviews) and “a thorough tour of the language” (Wall Street Journal). You’ve been called “David Foster Wallace’s favorite grammarian” (New Yorker) and “the world’s leading authority on the English language” (Business Insider). That’s heady stuff, isn’t it?I’m just a dogged researcher. That’s all. Research is simply formalized curiosity, and I seem to have an inexhaustible curiosity about practical problems that arise for writers and editors. I certainly wouldn’t call myself “the world’s leading authority on the English language.”

I’ve also been helped by generous scholars, especially by John Simpson, the Oxford lexicographer, and Geoffrey K. Pullum, the Edinburgh grammarian. And then I had a panel of 34 critical readers who minutely reviewed 55-page segments for suggested improvements. I can’t tell you how grateful I am for the contributions of all these erudite friends.

In any event, a lexicographer must be especially adept at delayed gratification. You labor for years and then wait. You’re lucky, as Samuel Johnson once said, if you can just “escape censure.” That some people have praised my work, after all these years of toil, is certainly pleasing. But for me, the real pleasure is in the toil itself: asking pertinent questions and finding useful, fact-based answers to all the nettlesome problems that arise in our wildly variegated English language.

Find out more and buy Garner’s Modern English Usage, Fifth Edition →

January 26, 2023

“A tiger’s heart wrapped in a player’s hide”: Shakespeare under attack

“A tiger’s heart wrapped in a player’s hide”: Shakespeare under attack

Around three years into his career as a dramatist, Shakespeare’s blank verse—his unrhymed iambic pentameter—came under attack:

there is an upstart crow, beautified with our feathers, that with his tiger’s heart wrapped in a player’s hide supposes he is as well able to bombast out a blank verse as the best of you; and being an absolute Johannes fac totum, in his own conceit the only Shake-scene in a country. O! that I might entreat you rare wits to be employed in more profitable courses and let these apes imitate your past excellence, and never more acquaint them with your admired inventions.

This passage from Greene’s Groatsworth of Wit (1592) is the first recorded response to Shakespeare’s writing and the first reference to Shakespeare in print. It was written by some combination of Henry Chettle and Robert Greene (although most scholars now think Chettle was the principal author, it was designed and marketed as Greene’s). The passage can be characterised by “lasts” as well as by “firsts.” It appears on the last pages of the Groatsworth, in a letter addressed “To those gentlemen his quondam acquaintance that spend their wits in making plays.” And it emerged from the last days of Greene’s life. He was dying. If we believe his adversary Gabriel Harvey, Greene had succumbed to “a surfeit of pickled herring and Rhenish wine” after a lifetime of boozing (even his occasional ally Thomas Nashe would admit, and then assert, that Greene’s “only care was to have a spell in his purse to conjure up a good cup of wine with at all times”). By the end of 1592, Greene was dead. The Groatsworth was published posthumously by Chettle.

In the letter’s catalogue of abuses, Greene attacks Christopher Marlowe for his atheism, Thomas Nashe (or perhaps Thomas Lodge) for his wit, and George Peele for being neither Marlowe nor Nashe. Greene allows a little admiration for these three “gentlemen” (his “sweet boy” Nashe, and “the other two, in some things rarer, in nothing inferior”)—sufficiently so for Thomas Dekker to later stage Greene, Marlowe, Nashe, Peele, and Chettle engaged in nothing worse than good-humoured spat. It is only Shakespeare who emerges without anything like the “Million of Repentance” advertised by the Groatsworth’s subtitle.

The Groatsworth’s salvo at an “upstart crow” has long been interpreted as an accusation of plagiarism (the “Shake-scene” Shakespeare beautifying his plays with others’ feathers) and/or as a belittling remark about Shakespeare having been a mere actor (an “ape” for others’ inventions). Yet scholars have not paid proper attention to the Groatsworth’s remarks about Shakespeare’s blank verse: that he “supposes he is as well able to bombast out a blank verse as the best of” the best playwrights. To “bombast” is to “stuff” or “swell.” According to Greene, Shakespeare’s blank verse is both too little and too much; he pads out its essential emptiness (its blankness, even) with portentous rhetoric and vacuous sound. In thinking about Shakespeare’s alleged “bombast,” we might consider whether he spoke others’ blank verse with a bellow (if he is one of the actorly “puppets […] that speak from our mouths”), and whether his own blank verse was especially or exclusively bombastic, or whether the Groatsworth was condemning the blank verse of the period as typically and vexatiously loud and then condemning Shakespeare for being unable, or all too able, to reach that miserable standard. In other words, we might wonder whether the Groatsworth was right rather than treating it “as something to attack, or a document from which Shakespeare needs defence or exoneration” (as Andy Kesson has put it).

The Groatsworth twists a line from 3 Henry 6: “his tiger’s heart wrapped in a player’s hide” alludes to “O tiger’s heart wrapp’d in a woman’s hide!” (1.4.138). As it appears in 3 Henry 6 the line is part of York’s long polemic against Queen Margaret. Having treated him to a mock-crucifixion and wiped his face with his son’s blood, Margaret urges York to “Stamp, rave, and fret” (92). York obliges. He calls her “an Amazonian trull” (115), “vizard-like” (117), “as opposite to every good / As the Antipodes are unto us, / Or as the south to the Septentrion” (136-8), “stern, indurate, flinty, rough, remorseless” (143), “ruthless” (157) and “abominable” (134), “more inhuman, more inexorable – / O, ten times more – than tigers of Hyrcania” (155-6). Could this be the “bombast” which Greene hears in Shakespeare?

At the start of my new book Shakespeare’s Blank Verse: An Alternative History, I listen to the rhythms of this early Shakespearean blank verse and establish what about it makes the verse sound so bombastic—and then how Shakespeare wriggled loose of such bombast over the course of his career, and finally returned to Robert Greene’s criticism by versifying his prose romance Pandosto (1588) into the supple, non- or un-bombastic blank verse of The Winter’s Tale (c.1611). Can we even think of Shakespeare as taking his revenge upon Greene, in a play much concerned with questions of retribution and restitution, by finally returning Greene’s epistolary assault to its sender?

January 25, 2023

Gr-words as mushrooms

This is a continuation of the previous post, and the reference in the title is to my idea that some words propagate like mushrooms: no roots but a sizable crowd of upstarts calling themselves relatives. In that post, words of the map-mop type were discussed. Gr-words are the pet subject of all works on sound imitation and sound symbolism. Grim grumblers growl and grit their teeth much to the gratification of those who attack this piece of etymological granite. Today, I am returning to the question about words of suspicious and unknown origin.

It is rather clear why speakers associate gr- with grinding and growling, and the etymology of grist and grit has been accounted for quite successfully. But there are numerous gr-verbs that have nothing to do with grinding and growling, and dictionaries have little to tell us about their descent. Grip means approximately the same as grasp. It has existed since the days of Old English, and its German cognate greifen (the same meaning) shows that we are indeed dealing with an old word. Elmar Seebold, the editor of the main etymological dictionary of German, naturally, cites the ancient Germanic root and adds that Slavic and Baltic have similar verbs (for instance, Russian grabit’ “to rob”; add to it Russian grebú “I rake together”), but that the relations between the Germanic and Balto-Slavic lookalikes remain unclear. In this context, unclear means that the ancient root gr-b cannot be reconstructed for all such verbs (because the vowels do not match).

This is what raking really means!

This is what raking really means!By Haddon E P, USFWS on Pixnio (public domain)

Walter W. Skeat mentioned Low German grapsen and a stray occurrence of the Middle English form grapsen and suggested that grasp goes back to grabsen. The OED finds this idea feasible. Ernest Weekley also shared Skeat’s opinion. Perhaps so, but as likely, grapsen was a folk etymological variant of graspen (a natural attempt to ally grasp to grab) or a form with ps from sp by metathesis (transposition of sounds). To cite a parallel case, wasp occurred in Old English in the forms wæsp and wæps (æ had the value of a in Modern English aspen)

This is where a broader view of all those words may perhaps be of some value. Grope, grip, and gripe, which are related to one another and to German greifen, also have reputable West Germanic ancestry, as evidenced by German greifen “to grab.” Is grab another member of the same family? Perhaps so, if we accept the evasive idea that the root of this verb, borrowed from Low German or Dutch, is a “modification” of the root we find in grip. Obviously, modification is a face-saving term, unlike ablaut, which refers to regular alternations. But in principle, this term reflects the true state of affairs. We have a loose cohesion of “bases,” and that is why so many partly synonymous verbs exist. On this boggy soil, every step is unsafe. The English verb to grave (related to German graben) means “to dig; bury.” And once again, Elmar Seebold (at graben) cites Russian grebú as a cognate. Does it follow that grip and grave are related? There is no reason why they should not be, but the nature of the alliance is not quite clear.

Two types of etymological dictionaries exist. Some cite individual words and discuss their origin in individual entries, in which we find references to several related words. A few other dictionaries (mainly those of old and reconstructed languages) feature in their headings nests of cognates, so that we can see the broad picture at a glance. In Modern English, Eric Partridge, a great expert in slang and Shakespeare’s “bawdy” language, had little knowledge of historical linguistics but boldly produced an etymological dictionary of English and chose the second approach. In criticizing his predecessors, he wrote that: “…they treat words so briefly and ignore ramifications so wholeheartedly that it was easy to plan a work entirely different.”

True, under individual headings, his dictionary treats groups of words, but his book is derivative of other dictionaries and has no independent value, except, as just noted, for featuring “nests,” rather than separate vocables. The entry that interests us has the heading grip, gripe, grippe, grope, grasp. Partridge does not say why he combined those words and does not refer to any old roots, so that all our questions remain unanswered. He also missed the verb grave and the noun grub, allied to grave.

Eliza Doolittle’s aunt died of influenza, but we are safe!

Eliza Doolittle’s aunt died of influenza, but we are safe!By Whoisjohngalt via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Grippe is (as Partridge also says) believed to be a borrowing from French, to which it, allegedly, came from Germanic. The idea is that the grippe grips one hard. This is an unconvincing approach to a disease that in the past was not supposed to be particularly dangerous (the word conquered Europe in the eighteenth century). Grippe was earlier the name of several infectious diseases and sometimes meant “a bad mood.” That is why the Slavic source of this word (Russian khrip “hoarse voice”) is unlikely. The grippe does grip one hard, but in the present context, the word can be ignored.

The broader topic deals with native words multiplying like mushrooms, rather than with borrowings. Sure enough, grope, grasp, grip, gripe, grab, and grave look like a family, but the question is whether it is a family of siblings descended from the same root (ancestor) or a family of mushrooms multiplying by spores. At its inception, historical linguistics drew its inspiration from botanical metaphors: words have trees, roots, and stems, while languages form branches. No harm will be done if we sometimes choose to refer to spores. A certain sound complex like grb/grp can produce an indefinite number of similar-sounding words, loosely connected with regard to form and meaning. Another complex, for instance, m-p, spawns map, mop, mope, and so forth. (Spawn has nothing to do with mushrooms, but the metaphor seems to be appropriate.)

Once again, I would like to repeat that the reconstructed ancient roots are only the common part of the recorded words. They never had an independent existence and are only useful as formulas that help researchers to organize the vocabulary of the most ancient languages. Write is indeed the basis of writer; it does exist as an independent word, and so do writ, writes, wrote, writing, and written. Such is not the case of gripe, grope, grasp, and perhaps grub.

A grub eager to join the gr-family.

A grub eager to join the gr-family.By Bernard Ladenthin via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 4.0)

My previous blog post (18 January 2023) was devoted to this idea. As of 20 January 2023, when I am writing this post, there has been no discussion of it. What concerns the remarks pertaining to Hebrew (private) and Greek (posted), rather than to my main question, I hope to address them in my next “gleanings,” once I have enough material for them. But I would be glad to hear objections to or approval of the mushroom idea. If no comments follow this appeal, I will turn to other topics. Etymology is a broad field, and every word is a worthy subject for meditation and scrutiny. Amazingly, the Russian word for “mushroom” is grib, and anyone can see that it begins with gr. I look upon this fact as a nod of approval from some higher authority.

Featured image by George Chernilevsky via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Gr- words as mushrooms

This is a continuation of the previous post, and the reference in the title is to my idea that some words propagate like mushrooms: no roots but a sizable crowd of upstarts calling themselves relatives. In that post, words of the map-mop type were discussed. Gr-words are the pet subject of all works on sound imitation and sound symbolism. Grim grumblers growl and grit their teeth much to the gratification of those who attack this piece of etymological granite. Today, I am returning to the question about words of suspicious and unknown origin.

It is rather clear why speakers associate gr- with grinding and growling, and the etymology of grist and grit has been accounted for quite successfully. But there are numerous gr-verbs that have nothing to do with grinding and growling, and dictionaries have little to tell us about their descent. Grip means approximately the same as grasp. It has existed since the days of Old English, and its German cognate greifen (the same meaning) shows that we are indeed dealing with an old word. Elmar Seebold, the editor of the main etymological dictionary of German, naturally, cites the ancient Germanic root and adds that Slavic and Baltic have similar verbs (for instance, Russian grabit’ “to rob”; add to it Russian grebú “I rake together”), but that the relations between the Germanic and Balto-Slavic lookalikes remain unclear. In this context, unclear means that the ancient root gr-b cannot be reconstructed for all such verbs (because the vowels do not match).

This is what raking really means!

This is what raking really means!By Haddon E P, USFWS on Pixnio (public domain)

Walter W. Skeat mentioned Low German grapsen and a stray occurrence of the Middle English form grapsen and suggested that grasp goes back to grabsen. The OED finds this idea feasible. Ernest Weekley also shared Skeat’s opinion. Perhaps so, but as likely, grapsen was a folk etymological variant of graspen (a natural attempt to ally grasp to grab) or a form with ps from sp by metathesis (transposition of sounds). To cite a parallel case, wasp occurred in Old English in the forms wæsp and wæps (æ had the value of a in Modern English aspen)

This is where a broader view of all those words may perhaps be of some value. Grope, grip, and gripe, which are related to one another and to German greifen, also have reputable West Germanic ancestry, as evidenced by German greifen “to grab.” Is grab another member of the same family? Perhaps so, if we accept the evasive idea that the root of this verb, borrowed from Low German or Dutch, is a “modification” of the root we find in grip. Obviously, modification is a face-saving term, unlike ablaut, which refers to regular alternations. But in principle, this term reflects the true state of affairs. We have a loose cohesion of “bases,” and that is why so many partly synonymous verbs exist. On this boggy soil, every step is unsafe. The English verb to grave (related to German graben) means “to dig; bury.” And once again, Elmar Seebold (at graben) cites Russian grebú as a cognate. Does it follow that grip and grave are related? There is no reason why they should not be, but the nature of the alliance is not quite clear.

Two types of etymological dictionaries exist. Some cite individual words and discuss their origin in individual entries, in which we find references to several related words. A few other dictionaries (mainly those of old and reconstructed languages) feature in their headings nests of cognates, so that we can see the broad picture at a glance. In Modern English, Eric Partridge, a great expert in slang and Shakespeare’s “bawdy” language, had little knowledge of historical linguistics but boldly produced an etymological dictionary of English and chose the second approach. In criticizing his predecessors, he wrote that: “…they treat words so briefly and ignore ramifications so wholeheartedly that it was easy to plan a work entirely different.”

True, under individual headings, his dictionary treats groups of words, but his book is derivative of other dictionaries and has no independent value, except, as just noted, for featuring “nests,” rather than separate vocables. The entry that interests us has the heading grip, gripe, grippe, grope, grasp. Partridge does not say why he combined those words and does not refer to any old roots, so that all our questions remain unanswered. He also missed the verb grave and the noun grub, allied to grave.

Eliza Doolittle’s aunt died of influenza, but we are safe!

Eliza Doolittle’s aunt died of influenza, but we are safe!By Whoisjohngalt via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Grippe is (as Partridge also says) believed to be a borrowing from French, to which it, allegedly, came from Germanic. The idea is that the grippe grips one hard. This is an unconvincing approach to a disease that in the past was not supposed to be particularly dangerous (the word conquered Europe in the eighteenth century). Grippe was earlier the name of several infectious diseases and sometimes meant “a bad mood.” That is why the Slavic source of this word (Russian khrip “hoarse voice”) is unlikely. The grippe does grip one hard, but in the present context, the word can be ignored.

The broader topic deals with native words multiplying like mushrooms, rather than with borrowings. Sure enough, grope, grasp, grip, gripe, grab, and grave look like a family, but the question is whether it is a family of siblings descended from the same root (ancestor) or a family of mushrooms multiplying by spores. At its inception, historical linguistics drew its inspiration from botanical metaphors: words have trees, roots, and stems, while languages form branches. No harm will be done if we sometimes choose to refer to spores. A certain sound complex like grb/grp can produce an indefinite number of similar-sounding words, loosely connected with regard to form and meaning. Another complex, for instance, m-p, spawns map, mop, mope, and so forth. (Spawn has nothing to do with mushrooms, but the metaphor seems to be appropriate.)

Once again, I would like to repeat that the reconstructed ancient roots are only the common part of the recorded words. They never had an independent existence and are only useful as formulas that help researchers to organize the vocabulary of the most ancient languages. Write is indeed the basis of writer; it does exist as an independent word, and so do writ, writes, wrote, writing, and written. Such is not the case of gripe, grope, grasp, and perhaps grub.

A grub eager to join the gr-family.

A grub eager to join the gr-family.By Bernard Ladenthin via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 4.0)

My previous blog post (18 January 2023) was devoted to this idea. As of 20 January 2023, when I am writing this post, there has been no discussion of it. What concerns the remarks pertaining to Hebrew (private) and Greek (posted), rather than to my main question, I hope to address them in my next “gleanings,” once I have enough material for them. But I would be glad to hear objections to or approval of the mushroom idea. If no comments follow this appeal, I will turn to other topics. Etymology is a broad field, and every word is a worthy subject for meditation and scrutiny. Amazingly, the Russian word for “mushroom” is grib, and anyone can see that it begins with gr. I look upon this fact as a nod of approval from some higher authority.

Featured image by George Chernilevsky via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

January 24, 2023

America’s first feminist ballet: Ruth Page and American Pattern

In 1977, reflecting on a six-decade career, Ruth Page (1899–1991) made an off-the-cuff remark to a newspaper reporter: “I was always making up dances. I knew right away that was the world for me. I never could endure a humdrum life.”

In her more than nine decades of life, Page created a large oeuvre of choreographies, served as the artistic director of several dance companies, staged her ballets on numerous others, completed 13 extensive national tours at the helm of the Chicago Opera Ballet, and collaborated with countless international and Chicago-based artists in dance and the related arts. As that rare creature—an American woman who, defining herself as a choreographer and ballet director, amassed a degree of power and prestige and exerted aesthetic prerogatives—her life and work offer refreshing paradigms for the twenty-first century, at a time when women still encounter a “satin ceiling” in the ballet world.

Page’s career stands as an exemplar of how a wider spectrum of choreographic voices could serve the diversity of ballet and, consequently, its popular appeal and ability to flourish today.

Always a creative boundary-crosser—whether of genre, gender, race, or sexuality—Page generated movement through her own embodied practice, using kinesthetic methods that stood at the cutting edge of modernism. Neoclassicism struck her as a banal throwback. So far from seeking purity of the medium, she relished what one might call the anti-ballet, or what was not ballet in the space of ballet; an experimentalist, she tested the limits.

“American Pattern embodied … woman-centered subjectivity and [an] implicitly feminist critique of women’s lack of meaningful options in society.”

Page’s ballet An American Pattern—originally titled An American Woman—presented an explicit statement of a female subject position. Premiering on 18 December 1937, it was probably, to boot, the first feminist ballet created in the United States. Not that its feminist message was unequivocal and resolute, because, for one thing, it emerged as a highly collaborative project, with Nicolas Remisoff co-authoring the scenario, Jerome Moross composing the music score, and Bentley Stone co-creating the choreography. Nevertheless, American Pattern embodied some of the dilemmas, conflicts, and compromises in Page’s own life, and these fueled its woman-centered subjectivity and implicitly feminist critique of women’s lack of meaningful options in society.

Early drafts of program notes hint at some of the ballet’s ambivalent messages. One seems to question the whole institution of marriage from a middle-class woman’s perspective: “Her husband, being himself satisfied with the limitations of American business success, has little meaning for her as a woman, so that in the end they are strangers. There seems to be nothing ahead for her except dull routine, to which she succumbs.” Was Page bucking “the problem that [had] no name” 26 years before Betty Friedan’s groundbreaking The Feminine Mystique touched off a second wave of feminism? The scenario certainly seems to challenge ideas that a woman’s whole being should revolve around husband and home, with housework representing the pinnacle of achievement. Admittedly, the jabs at American capitalism and unthinking automatism give it a quasi-radical, interwar-era slant; nevertheless, its focus on a woman’s alienation and failure to discover meaningful existence, hemmed in as she was by convention, anticipates feminist arguments articulated decades later.

In Lament, Ruth Page inscribed her voice as a woman into Federico García Lorca’s “Lament for Ignacio Sánchez Mejías” by simultaneously enunciating the words of the poem and embodying the movement of the dance.

In Lament, Ruth Page inscribed her voice as a woman into Federico García Lorca’s “Lament for Ignacio Sánchez Mejías” by simultaneously enunciating the words of the poem and embodying the movement of the dance.In the ballet’s plot, the young woman turns from one false icon or empty ecstasy to another: sex, money, mysticism, and mob—each represented by a male power figure. Neither acquiescing to nor flouting conventional, decorous existence offers a solution. Does the tragedy proceed from a flaw in the development of a self or society’s lack of meaningful options? Or are these two failings intimately related? “Her life is tragic because she has failed to find herself—her soul.” The woman finds neither worthwhile purpose nor meaningful relationships; it is truly an existential crisis without the prospect of educational or professional growth, self-development, or transformation.

Such a predicament did not exactly reflect Page’s life. She had found meaningful—very meaningful—work: dance. She had built gratifying relationships with her husband and chief advocate, Thomas Hart Fisher; with coworkers in the arts; and with friends in Chicago, New York, and Europe. She had found her soul in creating through dance. Moreover, she knew how to educate herself through mentors and collaborators, literary and cultural pursuits, touring and travel, and new ballet projects. However, there was one overarching conflict or compromise in her life that could at times be felt as bad faith: settling for Chicago when she wanted New York. Her marriage to Fisher had made that compromise necessary. Nevertheless (or perhaps because of this), her husband supported her career ambitions magnificently, serving as her agent and attorney and, as a fellow arts lover and cultural patron, sharing her fascinations and commitments. But the kernel of truth in American Pattern—beyond its choreographic study of a social malady larger than herself—was that conventional, respectable, patterned existence filled her with dread. The life of a housewife, dilettante, or nondancer (non-doer of any sort) was anathema and oppression to her.

Flagrant, outlandish, off-kilter, and weird, yes; “humdrum,” no—not a word one would ever use to ponder the life and work of Ruth Page.

Featured image: “Scene of ‘class struggle’ from Ruth Page and Bentley Stone’s 1937 ballet An American Pattern.“

Images used with permission from the Ruth Page Collection at the New York Public Library

January 20, 2023

Life of a Contrarian Writer: James Purdy’s life-changing correspondences [excerpt]

![A contrarian writer: James Purdy's life-changing correspondences with William Carlos Williams, Dame Edith Sitwell, and Carl Van Vechten [excerpt from the new biography]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1674556350i/33868644.jpg)

The American author James Purdy has long been considered a “lost” figure in literary studies—during his life he constantly struggled to find commercial and critical success, but he has always enjoyed a certain cult following among artists and writers interested in the fringes of society. This status was cemented early in his career. Michael Snyder, in the new biography, James Purdy, details how after publishing two key works, Purdy began making the connections that would carry him through his career.

Excerpt from James Purdy: Life of a Contrarian WriterThat autumn of 1956, Purdy reaped a harvest of correspondence from recipients of Don’t Call Me by My Right Name and Other Stories and 63: Dream Palace. This bounty vindicated his talent and risky decision to leave his teaching position.

Modernist poet William Carlos Williams wrote in September. Since he had suffered a stroke five years earlier, reading was difficult, so he depended on his wife, Florence Williams. She read aloud the first three stories, which they both enjoyed, and they planned to finish. Williams was frank in praise and criticism: “You have a rather lumpy style but at least there’s no redundancy and the perception and feeling makes the stories notable to a receptive mind. They’re downright good if at times somewhat crude—”…

Chicago writer Nelson Algren, a friend of Gertrude Abercombie who caused controversy with tough urban novels like Walk on the Wild Side and The Man with the Golden Arm, thanked him for the collection. “Your people come sharply alive. Hope the next book will be hardcover, and as honest as this one.” Thornton Wilder also wrote from Chicago with “many thanks” for the stories; he read them with “much admiration,” finding them “filled with remarkable insights,” especially “Eventide” and “Sound of Talking.”…

The most magnificent reply was from Dame Edith Sitwell. In late October, Purdy’s fate was forever changed. Although Purdy mailed the book to Sitwell, her discovery of it was a “minor mystery that was never solved,” her secretary and biographer Elizabeth Salter states. Edith fell asleep one afternoon at Castello di Montegufoni with “windows shuttered and doors closed against draughts and intruders as was her custom,” but when she awoke, a book was lying on her bed that “had not been there when she went to sleep.” Her memory may have failed her, though, since she was drinking a lot of wine in those days and had recently bloodied her face after a bad fall. Reading “Eventide” first, Sitwell believed she had “stumbled on a great Negro writer,” Salter writes. On October 20, 1956, Sitwell wrote from Montegufoni: “I do not know whether it was you, or whether it was your publishers, who sent me your Don’t Call Me by My Right Name. But I owe a debt of gratitude to you and to them.”…At her loneliest, Edith found that Purdy’s stories, with their “great compassion, insight, and mastery of language,” provided much consolation, biographer Geoffrey Elborn writes. She could “identify with the mood,” and was “overjoyed to have discovered a new writer in whom she sincerely believed.”

Stunned, James then sent 63: Dream Palace. Sitwell read it twice within two days of its arrival. According to Purdy, after reading its devastating ending capped with an obscenity, Sitwell swooned, and declared: “My former life has come to an end!” On November 26, Sitwell marveled: “What a wonderful book! It is a masterpiece from every point of view.” She was “quite overcome. What anguish, what heart- breaking truth!” He was “truly a writer of genius.” … Believing 63: Dream Palace and the stories ought to be bound together in one volume, she recommended her agents including David Higham and said she would write to them. She thought poet “Stephen Spender’s Encounter might be a good place” for his stories in England. As is now known, Encounter was secretly funded by the CIA. As soon as Spender returned to England, Edith wrote him about the stories. She spread the word to friends. To Portuguese poet and BBC Radio presenter Alberto de Lacerda, she acclaimed Purdy as a “much greater writer than Faulkner.” She could not think of “any living prose writer of short stories and short novels who can come anywhere near him. He is really wonderful.” With this all set in motion, within months, Gollancz accepted the works for publication.

Sitwell’s lyrical responses to his books nearly had an “unhinging effect” on Purdy. Reading her letters over and again, he could scarcely believe Sitwell had written them, since the works she extolled were the “very same works, unchanged in any particular” that American publishers had rejected with “bitter denunciation, contempt, and derision.”… On Purdy’s forty- third birthday, Sitwell wrote: “I am certain as I can be of anything that you will, in the course of time, be given the Nobel Prize.” He replied, “The person who should win the Nobel Prize, my dear Edith, is you! So many poets not fit to tie your shoelaces have won it.” Sitwell’s correspondence showed “extraordinary kindness and devotion to those she believed in,” and “warrior- like courage in defending them,” Purdy wrote Elborn. A fighter, Purdy admired those who fought for their convictions.

Many literati found Purdy’s use of black vernacular in “Eventide” authentic, and like Sitwell, a number of them initially assumed him to be black, including novelist and photographer Carl Van Vechten, poet Langston Hughes, and British novelist Angus Wilson. A longtime supporter and friend of black creatives, Van Vechten’s misapprehension is corroborated by his letter of November 1956: “I wish you would read Giovanni’s Room by another Negro friend of mine, James Baldwin.” Set in Paris, Baldwin’s novel was groundbreaking in its frank depiction of gay and bisexual life. Before meeting Purdy, “Carlo” solicited more information and a photo, and in December, he wrote: “I don’t mind TOO MUCH your NOT being a Negro. The reasons your Washington [DC] friends think you ARE is doubtless because you make frequent references to matters like ‘passing’ but doubtless you do it to tease or terrify.” In early 1957, Van Vechten stated, “Whether you are white or colored doesn’t make too much difference to me, but I am a little prejudiced in favor of COLOR!” When Purdy first arrived at his Park Avenue West apartment on December 18, Van Vechten seemed to hold out hope that James had a smidgen of African “blood” because Carlo “seemed surprised when he saw James,” Jorma said. Tall, white- haired Van Vechten looked him up and down and quipped, “I don’t think you have a drop.” During the evening, Van Vechten photographed the couple. Purdy was “one of the last writers Van Vechten championed seriously and continually,” and he even arranged for Purdy’s early papers to be accepted into Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

A week before Sitwell responded to the novella, Van Vechten wrote: “63: Dream Palace is NOW MY Dream Palace. ‘I would like to attend a wedding with you, on some bleak day, each carrying tiny cages of white rats in lieu of a prayer book. This would be HEAVEN. Hell would be attending a football game in evening clothes. I want to send some of your wet- dream palaces around and I find your publisher ridiculously slow in shipping. We must think of a better plan.” Carlo made it clear he intended to help Purdy find a good publisher. Seemingly referring to James, Van Vechten added a limerick exemplifying camp aesthetics:

Said a morbid and dissolute youth

I think Beauty is greater than Truth,

But by Beauty I mean

The obscure, the obscene,

The diseased, the decayed, the uncouth.

Such a response from this legend was thrilling. James in turn began to shower Carlo with new poems, satires, and stories, signed and dedicated to him. Purdy later declared that Edith Sitwell rescued him from certain obscurity, which is an attractive myth. But even if Sitwell had never encountered the work, Van Vechten would have helped him to get published in New York—just as he had helped Ronald Firbank, Langston Hughes, Nella Larsen, and many others.

Featured image by Carl Van Vechten, March 15, 1957 (public domain)

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers