Oxford University Press's Blog, page 54

April 2, 2023

When meanings go akimbo

The realization started with the word akimbo. I had first learned it as meaning a stance with hands on the hips, and I associated the stance with the comic book image of Superman confronting evildoers. Body language experts sometimes call this a power pose, intended to project confidence or dominance.

From time to time, I had encountered akimbo used to mean haphazardly sprawled, in expressions like “arms and legs akimbo,” but I assumed it was an error. And I’d seen the occasional phrasing “legs akimbo,” which referred to a splayed position.

Then I ran across “studiously akimbo hair,” which seemed to connote an intentional messiness. It was time to check some dictionaries.

I found that akimbo comes from a Middle English phrase in kenebowe, which meant “at a sharp angle.” Arms and hands had been in kenebowe since the 1400s and a-kimbo from the 1800s. In the nineteenth century we find a tailor on a bench with his legs akimbo and a man dancing with knees akimbo. There are hearts akimbo, hats akimbo, curtains akimbo, and, yes, hair akimbo. Today there’s even an action movie called “Guns Akimbo.” The Oxford English Dictionary yields a 1940s Mayfair slang use for being on one’s high horse, with the example “She got terribly akimbo.” Bent out of shape, perhaps?

By now, it was clear to me that my narrow conception of akimbo had gone askew. I got curious about what other lexical preconceptions of mine might be in disarray, so I turned to penultimate and erstwhile.

Penultimate is still defined as “next to last,” though Merriam-Webster notes that it is sometimes used as an “intensified version of ultimate,” but not usually in edited prose. Erstwhile too is still defined as “former,” though it is sometimes used as a synonym for esteemed or as a fancy way ofsaying worthwhile.

It’s not hard to see how these meanings could shift in use. When someone refers to the “penultimate scene” of a play or “an erstwhile professor,” listeners may understand these as referring to a finale or an eminence. Vagueness permits some drift in common usage, but the specificity of the older definitions provides a strong counterweight. It’s one thing for a dictionary to go from akimbo to askew, but a bit harder to get from the meaning of final to next-to-last or of esteemed to former.

A word that has shifted like akimbo is cohort. From its beginnings as a tenth of a Roman legion, the word was later extended to other bands of warriors and to people united in a common cause. Later it also came to refer to a group sharing a demographic characteristic (such as an age cohort or a cohort of students).

Since a cohort is a group and groups are made up of individuals, cohort also came to refer to one’s compatriots. The Oxford English Dictionary gives the gloss “assistant, colleague, accomplice,” and one of the citations is a bit of snark from a 1965 issue of the Times Literary Supplement: “The new American vulgarism of ‘cohort’ meaning ‘partner’.”

And by the way, even though you might be in cahoots with your cohorts, the two words don’t seem to be related. Cahoot is most likely related to the French word cahute referring to a cabin or hut, where one might form a partnership away from prying eyes.

Words shift their meanings for a lot of reasons. For akimbo and cohort, the fuzziness of their early meanings (“limbs askew” and “band of individuals”) has left room for new standard meanings. In other cases, as with penultimate and erstwhile, dictionaries have resisted including the newer, casual uses. For now.

And sometimes, there is a split decision. Recognizing that some people blur amused and bemused, Merriam Webster gives the sense “wry amusement especially from something that is surprising or perplexing.” The OED sticks with the sense of confused, muddled, or stupefied.

I’m bemused for now but waiting to see how those meanings play out in the future.

Featured image by Leon ellDOT via Unsplash (public domain)

April 1, 2023

Announcing the winner of the 2023 Grove Music Online spoof contest

Announcing the winner of the 2023 Grove Music Online spoof contest

Happy April Fool’s Day! I’m pleased to announce that the winner of this year’s Grove Music Online Spoof Article Contest is Steven Griffin.

This year’s judges were:

Deane Root, Editor in Chief of Grove Music Online, and Professor of Music emeritus, Director and Fletcher Hodges, Jr. Curator of the Center for American Music, University of Pittsburgh. Dr. Root has been immersed in Grove style since he worked with Stanley Sadie on the first New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Kimberly A. Francis is a feminist musicologist and Professor of Music at the University of Guelph where she also serves as the Director of Interdisciplinary Studies for the College of Arts and an affiliate of the Sexualities, Genders, and Social Change program. Together with Tes Slominski, she is Editor in Chief of the Grove Music Online Women, Gender, and Sexuality update project.Tes Slominski is a music and sound scholar who studies gender, sexuality, and race in Ireland and in its diaspora. She published Trad Nation: Gender, Sexuality, and Race in Irish Traditional Music (Wesleyan, 2020). Together with Kimberly A. Francis, she is Editor in Chief of the Grove Music Online Women, Gender, and Sexuality update project.Scott Gleason is Acquisitions Editor for Music Reference at Oxford University Press, a position that includes editing for Grove Music Online.This year’s winning entry, by Steven Griffin, is “Back to Bolivia.”

Back to Bolivia Verismo opera by Newton Grosvenor, based on the little known 1878 plot by Bolivian nationalists to exhume Simón Bolívar’s body from its burial place in the National Pantheon of Venezuela, Caracas, and to bring it to La Paz for reinterment. The opera has never been performed in its entirety, perhaps due to the composer’s stipulation that an actual corpse must be used to portray the body of Bolívar in order to maintain the realism of the verismo ideal. Fans of Grosvenor were prevented from staging a performance at his funeral despite the composer requesting that his remains be used in this way in his last will and testament. At midnight on July 24 each year (Simón Bolivar Day), a group of ‘Grosvenorites’ still gather at Grosvenor’s graveside in Whitby Cemetery to sing the opening chorus ‘Did you remember the sledgehammer and crowbar?’ a cappella.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

M. Béclard d’Harcourt: ‘Le folklore musical de la region andine: Equateur, Pérue, Bolivié’, EDMC, 1/v (1922) 6543ff

A. Rawton-Bawdy: ‘Verisissimo – Ultra Realism in Grand Opera’ Oxford 1956

H. Erichsen ‘Cremation Versus Burial’ J.P. Morton & Co 1886

X. Hume ‘Loosening the Plot’ Brașov 1970

GERARD BÉHAGUE

For his winning entry Steven will receive $100 in OUP books and a year’s subscription to Grove Music Online.

Judge Root noted the entry is a spoof of the 1992 New Grove Dictionary of Opera entries, as if written by one of my mentors, Gerard Behague, who wrote much of the South American music coverage for the 1980 New Grove. Perfectly in keeping with the libretto-focused entries of New Grove Opera, with clever grave-humor puns in the bibliography (Exhume as the author of an article with a title that could be read as undoing a burial plot, and published by “brushoff”).

Please join me in congratulating Steven Griffin and thanking all those who submitted! We look forward to next year’s contest.

March 31, 2023

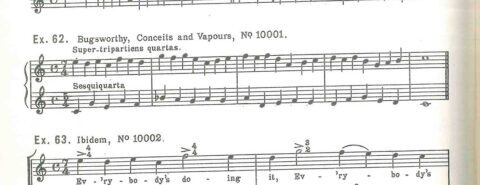

Nicholas Bugsworthy: an unknown Tudor composer?

Nicholas Bugsworthy: an unknown Tudor composer?

It seems unconscionably strange that the music of the great English Tudor composer Nicholas Bugsworthy (c.1540-?) should, to this day, remain utterly neglected, nay unknown. After all, the most eminent Tudor church music scholar of his day, Sir Richard Runciman Terry (1864-1938), proclaimed in 1928 (and in no uncertain terms) that Bugsworthy’s music “stands out in conspicuous supremacy by sheer force of its variety and originality, as well as by its special qualities of consummate technique, unquestionable dignity, beauty of outline, and nobility of purpose.” In the years following Terry’s declaration there have been absolutely no performances of works by Bugsworthy (known, incidentally, by his friends both as Boggysworth and Boggs), nothing was included in Oxford University Press’s pioneering and magisterial Tudor Church Music volumes (1922-29), there have been no modern editions or recordings, and no biography of the composer has ever been written. Bugsworthy is (curiously) absent from The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, and (scandalously, it seems to some) has no entry in The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (despite the inclusion in both eminent publications of his possibly less-brilliant colleagues Thomas Tallis and William Byrd). In summary, it is as if “Boggs” is the composer who, simply put, never was.

In pulling back the veil on Bugsworthy, Terry was jumping on an already slowly-moving (in fact stationary) bandwagon. His colleague the composer Reginald Owen Morris (1886-1948) was, six years before Terry, somehow “in the know.” Morris, when compiling the music examples for his book Contrapuntal Technique in the Sixteenth Century (OUP, 1922) had chosen two passages from Bugsworthy’s scores to illustrate points being made. Morris took his examples from the composer’s collection Conceits and Vapours: looking at these examples now, one is not only struck by the qualities that Terry was soon to identify as, shall we say, “Bugs-worthy,” but also that Boggs had a remarkable ability to pre-empt (with uncanny accuracy and prescience!) the music of many much later composers within the echt-Tudor textures of his works. One of the passages Morris selects (to exemplify sixteenth-century music’s “Proportions of Inequality,” discussed fully in Contrapuntal Technique) almost certainly shows the earliest version of musical patterns later to become threaded within Irving Berlin’s 1911 hit ragtime song Everybody’s Doin’ It Now (of which the opening phrase “Honey, honey, can’t you hear? Funny, funny, music dear” could be construed as pertinent to Bugsworthy). Morris highlights the connection by showing the words which became the celebrated refrain of Berlin’s song in appropriate position within Bugsworthy’s scoring (the composer’s work, claimed Morris happily, “demanded some slight mental activity” of the composer). Understandably, Berlin never acknowledged the debt. It was Morris’s preliminary work that evidently persuaded Terry that everybody should indeed be “doin’ it,” and that now was the time to look the Bugsworthy horse directly in the mouth.

“It is as if Nicholas ‘Boggs’ Bugsworthy is the composer who, simply put, never was.”

“Horse” is, though, perhaps a wrong image. The first discovery that Terry made concerned the armorial bearings of the Bugsworthy family (which was of Yorkshire descent—Nicholas’s Yorkist grandfather had been sadly slain on Bosworth’s field). Terry discovered that a “brock’s head” (badger) sat on the Arms’ escutcheon, while the Supporters were (dexter) “a dachshund argent” and (sinister) “an ourang-outang reguardant proper.” The Bugsworthy family motto was Sorte sua contentus—“content with his lot.” Stirred by these discoveries, Terry probed further into the record, going next to the Bodleian Library, Oxford—repository of the Giggleswick family papers (Nicholas had for many years been that famous family’s household musician, apparently) amongst which, bound up in “quaintly tooled binding,” the Bugsworthy manuscripts could be found. For Terry, this was indubitably the “Eureka!” moment. There he found before him “Madrigals, Ballets, and Fa-las” aplenty, the very Conceits and Vapours upon which Morris had drawn for his book. Then, following, contrapuntal instructions and exercises, In nomines, Fancies, Almains, Pavans, and music for Consort of Viols—nothing less than the stock-in-trade of any composer of Boggs’s day. Most unusual, however, was the collection of airs and songs Wiles and Wantonings which Nicholas had collected and arranged following his time at sea: Bugsworthy had, Terry tells us, “in early youth shipped aboard a Galeass (‘of an hundred and fifty tons burthen’) trading with Eastern Mediterranean ports.” The “gem” within this collection was, Terry discovered, No. 36, a “contrapuntal essay” in which the oriental air “Okar Fu Salaam” becomes the C.F (cantus firmus) in the tenor, combined with “The Querister’s Song of Yorke,” concluding with what Terry labels a “restful Coda.” The whole exercise thus brilliantly draws together materials taken both from Bugsworthy’s childhood experiences as a York Minister chorister and his later seafaring adventures. No other Tudor composer worked in quite this way, and it is clear to see why this particular example might have been overlooked (or unknown?) by Irving Berlin and other composers.

Maybe it is, in this centenary year of the OUP Music Department, during which we celebrate the story of our great music catalogue, that the Press’s editors could be persuaded to issue “first publications” of works by Boggs? A complete critical edition would quite likely be too onerous an undertaking but given that R.R. Terry eventually identified over ten-thousand unpublished works, it should not present too great a difficulty to select, perhaps, the top 10, and thus start the journey of putting Nicholas Bugsworthy firmly “back on the map.” Another view is that it might be wiser, and undoubtedly safer, to let good-friend Boggs simply remain Sorte sua contentus.

One matter of import should perhaps have been mentioned earlier, that it being noteworthy the first fruits of Terry’s research were revealed to an astonished public in a special supplement to the OUP Music Department’s own house journal The Dominant—“stop press,” hastily written and issued as Terry’s remarkable discoveries came to light, and carrying a most significant publication date: 1 April 1928.

The April 1928 issue of The Dominant, including the additional 1 April supplement

The April 1928 issue of The Dominant, including the additional 1 April supplementFrom the OUP Archive

Read “Nicholas Bugsworthy” by R. R. Terry in The Dominant, 1 April 1928

March 29, 2023

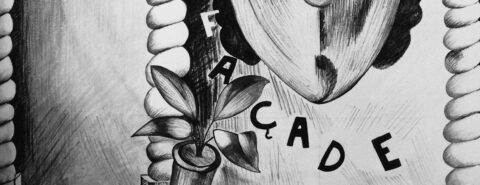

“Through Gilded Trellises”: a reflection on one hundred years of Façade

“Through Gilded Trellises”: a reflection on one hundred years of Façade

The making of Façade“Poetry is more like a crystal globe, with Truth imprisoned in it, like a fly in amber. The poet is the magician who fashions the crystal globe. But the reader is the magician who can find in these scintillating flaws, or translucent depths, some new undiscovered land.”

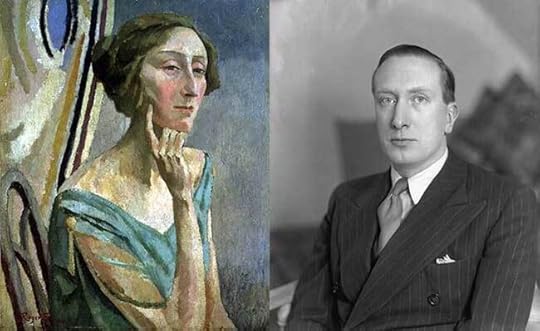

Osbert Sitwell, writing in 1921 (in his book of “remarks on poetry,” Who Killed Cock Robin?), accurately perceived the secret of the verses that his sister, Edith, was writing at that very time, and which, as they were produced, were being to set music by the Sitwell family’s young protégé, William Walton. By 1922 there were enough verses for Edith to publish in a small collection called Façade, and sufficient with music for an apparently unsuccessful private performance in the bitterly cold drawing room of the Sitwells’ London house. Walton conducted a small instrumental ensemble, Edith Sitwell declaimed through a special megaphone (a “Sengerphone”, its use suggested by the third Sitwell sibling, Sacheverell), and Osbert presided as master-of-ceremonies. The following year, with even more poems now set to music, the first public performance was given, on 12 June 1923, at London’s Aeolian Hall.

Edith Sitwell and William Walton

Edith Sitwell and William Walton“Portrait of Edith Sitwell” by Roger Fry, Wikimedia Commons (public domain); “Sir William Turner Walton”, Bassano Ltd whole-plate film negative, 3 April 1937. Bassano & Vandyk Studios, 1974, Photographs Collection.

That public premiere became something of a succès de scandale, with the hostile press criticisms (“naggingly memorable,” conceded the Daily Express) simply encouraging Sitwell and Walton to further endeavours in verse and music. Walton refined the music and instrumentation, and various new numbers were admitted, discarded, and altered, but by the early 1940s the collection had settled: a “Fanfare,” followed by twenty-one verses “spoken” over a musical accompaniment for flute, clarinet, saxophone, trumpet, cello, and percussion.

Walton’s publisher, Oxford University Press (OUP), had controlled the musical settings since 1926, but only published a score in 1951, almost thirty years after those contentious early performances—the score had a decorative front panel reproducing the back-curtain designed in 1942 by John Piper for performances of the work. That publication established Façade: An Entertainment as the definitive title for the collaborative work.

The composer and conductor Constant Lambert (who, after its premiere, had rapidly become a polished “narrator” of Façade), was very soon praising the “concentrated brevity” of the various numbers. Lambert labelled these as “satiric genre pieces, over in a flash, but unerringly pinning down some aspect of popular music, whether foxtrot, tango or tarantella.” Osbert Sitwell stated that his sister’s poems were experiments in sound, using words as musical rhythms to evoke the very dances named by Lambert. Some say that the “Entertainment” was simply making a jibe at the “modern music” of Schoenberg’s Pierrot lunaire of 1912 (also 21 verses set for “a speaking singer” and ensemble), others that it was merely playful whimsy on the part of the Sitwells and Walton.

Façade was chosen in 1978 as one of OUP’s own special quincentenary publications. A deluxe edition of the score in a slipcase was issued that year, showing the John Piper curtain design in full colour as a frontispiece, and featuring essays by Edith Sitwell and Frederick Ashton—once enfant terrible, Façade had become a favoured child.

Pages from the Façade quincentenary edition

Pages from the Façade quincentenary editionFrom the OUP Archive

Now, the centenary in 2023 of Façade’s first public performance allows us to move away from issues of genesis and growing pains, and instead provides a moment to reflect on Façade’s hugely important achievement, and its legacy in terms of the way its music became used and has become loved.

Music and verseSitwell’s language is rich in alliteration, assonance, and imagery: “Melons dark as caves have for their fountain waves / Thickest gold honey” in “Tarantella”; in “Valse”, Daisy and Lily are “lazy and silly”—they “Walk by shore of the wan grassy sea”; and “spangles / Pelt down through the tangles / Of bell-flowers” in “Through Gilded Trellises”. There are dark, disembodied, and surreal moments too: Queen Victoria sits “shocked upon the rocking horse” in “Hornpipe”, while Sir Beelzebub, in his verse, calls for syllabub “in the hotel in Hell”. Rhythm and effect provide the façade behind which meaning and syntax sit. Walton, in his music, responds directly and deftly to Sitwell in kind: musical allusion and reference (and, in one case, direct quotation), fragmentary and fleeting melody, and quicksilver changes of mood—for these poems, it was William Walton, rather than any reader, who held the key to their translucent depths and undiscovered lands.

“When Sir Beelzebub” from FaçadeMusic and verse, in Façade, work perfectly together, but at the same time do so in two curiously detached layers. Edith Sitwell’s words were not set by Walton in the conventional sense that they became songs; rather they were designed to be recited, or spoken, above the instrumental music, in rhythmic patterns determined by the composer. This immediately provided liberation for both the music and words, resulting in quite separate existences for each alongside their continued symbiosis as the “Entertainment.”

Sitwell had, as we have seen, published the then-small number of Façade items as poetry as early as 1922, with a complete edition following in 1950, and would often include selections in her celebrated poetry readings. The music (as both Walton and OUP quickly realized) was not, with a few exceptions, entirely dependent on Sitwell’s words for its effect, and mostly worked perfectly well without them—eventually resulting in a vast array of arrangements, adaptations, and new versions (all without words). Walton did, though, eventually set several of the Façade poems as songs: the now-lost Bucolic Comedies (voice and six instruments, 1923-4), and Three Songs (1931-2) for voice and piano (dedicated to Walton’s OUP publisher Hubert Foss and his wife Dora, who together recorded them for Decca in 1942). Of these three songs, the setting of “Daphne” is completely unrelated to its (eventually rejected) “Entertainment” version, while “Through Gilded Trellises” and “Old Sir Faulk” are broadly based on the originals.

Other composers, beyond Walton, have made musical settings of various Façade poems, but what was perhaps the ultimate tribute used neither Sitwell’s words nor Walton’s music at all. Noel Coward, who had walked out of the 1923 performance and afterwards perhaps read that early press review headlined “The Drivel They Paid to Hear,” included as a sketch in his first big revue, London Calling (1923), a merciless send-up of Edith Sitwell (now “Hernia” of the Swiss Family Whittlebot, the actress wearing clumps of fruit as earrings), her Whittlebot brothers, the poems, and Walton’s music. Even the venue of Façade’s first public performance was mocked: “the A-E-I-O-Ulian Hall,” Coward called it. Coward and the Sitwell family remained enemies for years as a result, especially after Coward, like Edith, had published his own skittish poems separately, under the title Chelsea Buns. But, as with all parodies, there was surely an element of respect on Coward’s part, and happily Noel and the Sitwells were eventually reconciled, in 1957, on the eve of Edith’s seventieth birthday.

Façade lives on…It was Walton who, in 1926, decided to transcribe five dance-based numbers from the “Entertainment” for medium orchestra (no speaker). These items were first performed at London’s Lyceum Theatre on 3 December 1926, conducted by the composer, in an interlude as part of that theatre’s season of Russian Ballet. This group of pieces rapidly became immensely popular under the banner “Façade Suite for Orchestra”, showing that the music was already moving far from its original foundation in amiable, if esoteric, entertainment. The suite was renamed “No.1” when Suite No. 2 (with the majority of items orchestrated by Constant Lambert) appeared in 1936. It is through these two orchestral suites, rather than via the “Entertainment”, that Walton’s music rapidly became firmly embedded in concert programmes and record catalogues, and therefore in the mind of the public. In 1991, for a Walton recording project with Chandos Records, Christopher Palmer created a third suite, comprising six numbers (including “Daphne” in the version from Three Songs). And four popular numbers found yet another incarnation in a version for salon orchestra made by Walter Goehr, published in 1939.

The market for domestic piano music (solo and duet) was still healthy at the time of Façade’s inception: arrangement of the catchiest numbers for this medium was an obvious step for OUP, especially having seen the popularity of the two orchestral suites. Broadcast music in Britain (from what was then the British Broadcasting Company) was “born” in the same year as Façade’s own first appearance, and mechanically reproduced music (the gramophone) was developing rapidly, but neither mode of music consumption in the home was yet ubiquitous—the pianoforte (just) remained the domestic music provider par excellence through to the Second World War. Walton himself produced the first Façade piano solo arrangement (“Valse”) in 1926—this was designated “Concert Arrangement,” was championed by Artur Rubinstein, and was in the end too difficult and showy for the domestic market.

Façade piano duet cover

Façade piano duet coverFrom the OUP Archive

It was Roy Douglas’s later and simpler solo piano arrangements of the five top numbers from the two orchestral suites (including “Scotch Rhapsody” and “Popular Song”) that became the sure-fire sellers. Piano duet arrangements by Constant Lambert of the two suites were published in 1927 and 1938 respectively (more-or-less coinciding with the launch of their orchestral counterparts). Ethel Bartlett and Rae Roberts commissioned two-piano versions of “Swiss Jodelling Song” (Herbert Murrill) and “Popular Song” (Mátyás Seiber) for their extensive “Oxford Music for Two Piano Series”—a note by Bartlett and Roberts in Seiber’s 1939 “Popular Song” arrangement made it clear that “it is rather the cheerful atmosphere of the old-fashioned Music-hall which is called for than the moaning of present-day crooners.” All of these arrangements were based on the “Suites” rather than “Entertainment” iterations of Walton’s music.

A frightening interview with the “immensely tall” Edith Sitwell was, for the choreographer Frederick Ashton, the immediate result of the most colourful and what has become the best known of all the Façade incarnations: his eponymous ballet. That meeting with Edith “was just like going before the headmistress,” recalled Ashton. “Why wasn’t I given a credit for Façade?” she demanded, having noticed that her name had not appeared on the programme of the ballet’s first performance (which had been given, on 26 April 1931, by the Carmargo Society in London). Being based on the orchestral versions (numbers from the first suite, plus various newly orchestrated items, themselves eventually to find a place in the second suite), the words were not recited and therefore had not been credited. But Ashton immediately caved in, conceding to Edith that an acknowledgement to her would “add great lustre to the whole thing.” Thus, the ballet is now designated as “freely adapted to music originally written as a setting to poems by Edith Sitwell.”

It was, though, Walton’s music (much of it based on the popular dance forms of the day, and “sounding like” ballet in orchestral form) rather than Sitwell’s words that had intrigued Ashton all along. “I wanted to do it and I did do it,” he said. Ashton’s choreography, notes his biographer Julie Kavanagh, was “a perfect match for the mood, wit and rhythms of the poetry and music, preserving a Sitwellian sense of fantasy and fun, while, at the same time, adding a personal, totally new dimension.” The dancers, in “Swiss Jodelling Song,” configure to provide a fantastical human cow, complete with udders and tail, and a dropped skirt revealing a pair of enormous bloomers still shocks in “Polka.” “I’m very fond of Façade,” said Ashton, “because I think it seems to me to be a complete entity in itself.” Matters turned full circle in 1972 when, in an evening of music at Aldeburgh in honour of Walton’s seventieth birthday, adaptations of Ashton’s choreography were given to the music of the relevant numbers in the original “Entertainment” scoring, with Peter Pears reciting Sitwell’s verses. In truth, it was indeed both William Walton and Edith Sitwell who sat behind and were the true progenitors of the by-then huge array of works, both literary and musical, known familiarly and collectively as Façade. One hundred years on, the fly no longer sits in amber.

Featured image: A sketch from the OUP Archive of John Spicer’s curtain design for the first public performance of Façade.

A guide to going to hell (first draft) and other matters

A guide to going to hell (first draft) and other matters

Since December 2022, when the University of Minnesota Press published my semi-etymological dictionary of English Idioms (Take My Word for It), I have received several questions about the origin of familiar phrases and some queries about the absence of others. The second batch of questions is easy to answer. My team consisting of two faithful volunteers who stayed with me for years and two more assistants, each of whom spent a single semester, looked through all the popular journals ever published in the English-speaking world, from The British Apollo (1708) to The New Yorker (still thriving), and alerted me to the articles and notes dealing with idioms. The selection and commentary were my duty. Also, if I happened to know some relevant works in a language other than English (provided they touched on English idioms), especially often in Latin, French, German, the Scandinavian languages, and Russian (less rarely in Spanish, Polish, etc.), I might add the relevant item or two to the database.

Some of the idioms featured in the book are hopelessly obscure, and the discussion in Take My Word for It may perhaps call attention to them for the first time since they were featured in Notes and Queries, The Academy, The Gentleman’s Magazine, and the rest. Conversely, some of the most “famous” phrases never turned up in my database. A glaring gap (to cite one example) is the whole nine yards. Here I should repeat that we screened only popular journals. Subscribers constantly sent letters to them with questions about the etymology of words and idioms, received answers from other readers, refuted, or supported certain suggestions, but as time went on, the exchange would often be forgotten, with the result that fifty or so years later, somebody would ask the same question, receive the same or similar answers, and no one would remember the first round. Alas, publications on etymology are hard to find.

The British Apollo.

The British Apollo.(Via Google Books, public domain)

This kind of exchange in the popular press lingered for a decade or so after the First World War and then petered out. Occasionally, Scientific American or Notes and Queries for Somerset and Dorset would still feature a discussion of a word or idiom, but in principle, this genre is now dead. The Internet provided a forum of which our ancestors could not even dream. Look up the whole nine yards in Wikipedia: an excellent article, supplied with an exhaustive bibliography. Nowadays, every literate person probably has a computer or/and a smartphone. Why should I have included such an entry? The greatest danger of even a semi-popular work is to be not wrong (mistakes cannot be avoided) but trivial.

While working on my dictionary, I googled for each item, to make sure that I had something of substance to add. Wikipedia features a semi-satisfactory entry on the idiom by hook or by crook, but I knew much more and included the idiom. With regard to rain cats and dogs, the Internet supplies the user with shameful nonsense (it refers to Old Norse mythology; allegedly, Odin had dogs, produced thunder, and so forth). Kick the bucket seems to have been explained rather convincingly, but the Internet fails the user. Finally, the Internet, except for a few responsible websites and Wikipedia, bears no responsibility for the information it provides, and the etymology found on it should be treated with healthy distrust. When the telephone was installed in Iceland, an old woman made herself famous by saying: “You heard it on the phone? That should be checked”—a most reasonable attitude, I would say.

Caution is invited.

Caution is invited.(Via Pexels, public domain)

Since the exchange on word and phrase origins in the popular press more or less petered out a century ago, I have no citations for countless new idioms, especially those going back to sports, jazz, rock, pop, and the rest of popular culture. Yet if articles on the origin of some idiom appeared in scholarly periodicals like American Speech, I of course discussed them. A good example is spittin’ image. Another example is put the kibosh on. The phrase was extensively discussed in the old issues of Notes and Queries, but two years ago, a book about it was published, and I, naturally, made use of it. Finally, I may mention a hog on ice, the object of long and not fruitless discussion. The phrase graces the title of a mainly dependable book by Charles Earle Funk. Finally, I looked up my material in all the existing English dictionaries of “phrase and fable” and commented on the solutions offered there when they differed from mine.

There are slightly over a thousand entries in Take My Word for It, while English, including its regional varieties, probably has at least a hundred thousand of them. Also, I mainly ignored proverbs, which are more numerous than stars in heaven.

Finally, I did not include phrases like give up, give in, put up with, and light out (for) “to rush out (for another place).” Their history is a special branch of lexicology (very dear to my heart, because it was the first topic I discussed in a research paper as an undergraduate). The only exception in my book was made for put up (with), because it once made its way into Notes and Queries. The origin of such verb-adverb collocations is often obscure: compare do in, make up, and their likes. The usage is also partly capricious. Why do we shut up but shut down our computers? I remember my puzzlement when I read in John Galsworthy’s novel Flowering Wilderness a woman’s request to another woman: “Please do me up from behind.” The British-American joke about knock me up in the morning is too stale to bear repetition.

Choose your favorite means of transportation.

Choose your favorite means of transportation.(Via Pixabay, public domain)

What follows was inspired by the question about the origin of the phrase unleash holy hell “to criticize one in a very angry way.” Holy hell (an exclamation) exists outside the longer phrase. I don’t know its origin, but I have a suggestion. Holy in holy hell is an obvious euphemism for “unholy, damned,” and it must have been chosen for the sake of alliteration, an important feature of English idioms and name giving. Even the latest of our cliches often follow this principle: publish or perish, bed and board, bed and breakfast, and so forth. I also recollect some other phrases with hell. One is to go to hell in a handbasket. The phrase seems to have been coined in America. The variant to go to heaven in a handbasket is also known. Countless people have asked word historians about the mysterious handbasket and received no answer. An alliterating joke that has no explanation? Consider also come hell or high water. The opposition (an ultimate depth versus a flood) is obvious, but so is the alliteration. Hot as hell and hell’s half-acre are not particularly memorable, but, like holy hell, they also alliterate. In the merry month of May, someone may meander less and enlighten us better. I know that my answer about hell is not convincing, but I had the best intentions in the world.

In the not too remote past, Hekla (the famous Icelandic volcano) was believed to be the place of real hell. Did it happen because Hekla sounds somewhat like hell in English, German, and the Scandinavian languages? In Sweden and Denmark, go to Heckenfel was once a famous curse. Hecklebirnie was known to be three miles beyond hell. The same usage has been recorded in Aberdeenshire. If one said: “Go you to the deil,” the reply often was: “Go you to Hecklebirnie.” Alliteration seems to be able to placate holy heaven and unleash unholy hell.

I have a curious set of notes tilted “Topographia Infernalis,” going back to 1884, and may quote parts of it next week.

Featured image by Hansueli Krapf, via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

March 28, 2023

Climate emergency: lessons from Classic Maya to contemporary China [podcast]

![Climate emergency: lessons from Classic Maya to contemporary China [podcast]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1680122729i/34088538.jpg)

Climate emergency: lessons from Classic Maya to contemporary China [podcast]

The consequences of climate change are catastrophic; floods, fires, droughts, rising sea levels, reduced biodiversity, and resource scarcity are but a few of the effects of failing to act. With the warmest decade on record behind us, and rising emissions before us, not to mention present conversations on how to best manage climate refugees, it is unsurprising that climate change is now a leading concern among institutions, and individuals, around the world. This real and present threat to our planet may seem insurmountable, but there are—and have been—lessons shared on how to mitigate the damage already wrought, and how to prevent future detriment.

On today’s episode, we explore two unique examples of societal adaptation to climate change: one from our past, and one from our present. First, we welcomed Kenneth E. Seligson, the author of The Maya and Climate Change: Human-Environmental Relationships in the Classic Period Lowlands, who shared insights into his work exploring the environmental resilience of the Classic Maya, the environmental challenges they faced and overcame, and the lessons we can learn from them. We then interviewed Scott M. Moore, the author of China’s Next Act: How Sustainability and Technology are Reshaping China’s Rise and the World’s Future, to speak about contemporary China’s meteoric and controversial rise to a global power, its leading role in sustainability and technology, and what this means for institutions around the world.

Check out Episode 81 of The Oxford Comment and subscribe to The Oxford Comment podcast through your favourite podcast app to listen to the latest insights from our expert authors.

Oxford Academic (OUP) · Climate Emergency: Lessons from Classic Maya to Contemporary China – Episode 81 – The Oxford CommentRecommended readingYou can read the introduction from Scott M. Moore’s book, China’s Next Act: How Sustainability and Technology are Reshaping China’s Rise and the World’s Future, which provides an accessible overview of a broad range of emerging issues that have reshaped China’s relationship with the world, including climate change, public health, artificial intelligence, and biotechnology.

In ‘Shifting the Focus’ from Kenneth E. Seligson’s The Maya and Climate Change: Human-Environmental Relationships in the Classic Period Lowlands, Seligson introduces conservation and sustainability practices of the Classic Maya including forestry, agriculture, water management, burnt lime production, and stone processing.

New in paperback, read the introductory chapter of Sustainable Materialism: Environmental Movements and the Politics of Everyday Life, by David Schlosberg and Luke Craven, which proposes the construction of different practices, institutions, systems for meeting some of our basic material needs—food, energy, and clothing—in more just and sustainable ways.

Also new in paperback, read the introduction to Building a Resilient Tomorrow: How to Prepare for the Coming Climate Disruption, by Alice C. Hill and Leonardo Martinez-Diaz, which analyses key developments and anticipated challenges in the emerging field of climate resilience, drawn from the authors’ unique network of national and international leaders in the private, public, and NGO sectors.

Read the following Open Access articles from our leading journals:

“Low-carbon warfare: climate change, net zero and military operations” by Duncan Depledge from International Affairs (March 2023)“Climate Change, Energy Transition, and Constitutional Identity” by J. S. Maloy from International Studies Review (March 2023)“Coping with Complexity: Toward Epistemological Pluralism in Climate–Conflict Scholarship” by Paul Beaumont and Cedric de Coning from International Studies Review (December 2023)“(Dis)order and (in)justice in a heating world” by Robyn Eckersley from International Affairs (January 2023)“What If: The Literary Case for More Climate Change” by Lucy Burnett from ISLE: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and EnvironmentFeatured image: “A morning shot in the jungle of Palenque of the Maya Temple of the Inscriptons and Temple of the Red Queen,” Danny van Dijk, CC0 via Unsplash

March 27, 2023

Why read Proust in 2023?

The world is literally on fire; authoritarianism threatens multiple countries; racism and xenophobia are rampant; women’s and LGBTQ rights are under threat—why on earth would anyone spend time reading a 3,000-page novel by a man who’s been dead (exactly) a hundred years?

Well, there’s at least some politics in Proust’s novel, In Search of Lost Time. The longest sentence—stretching over three full pages—is a lament for the plight of gay men, including Oscar Wilde, who had recently been sentenced to hard labor, more or less for the “crime” of being gay. (Painfully topical at a moment when a Supreme Court justice recommends reconsidering the Obergefell decision.) There’s a fair amount of talk about the Dreyfus Affair, a moment in French history when antisemitism came to the surface, much as it’s doing again today. There’s quite a bit about the folly that led us into World War I, not entirely unlike the folly of certain politicians who, for equally bad reasons, seem hell-bent on leading us into climate catastrophe.

And there’s plenty in Proust about the triumph of the mediocre, the worthless, the conniving. In one devastating episode, we see Mr and Mrs Verdurin—vapid and tyrannical salon hosts, desperate to be revered—successfully engineer a break between the Baron de Charlus and his boyfriend, violinist Charlie Morel, out of vindictive envy. Charlus has just brought his high society friends to watch a performance by Morel, something that could be transformative for his career. But behind the scenes the Verdurins have whispered lies to Morel, and just as Charlus congratulates him on his performance, he tells Charlus, as loudly as possible, to leave him alone, adding: “I’m not the first person you’ve tried to corrupt!” Charlus is stunned, humiliated, devastated; the Verdurins are triumphant.

In a beautiful coda to the scene, the Princess of Naples walks back in, having forgotten her fan, and finds Charlus shattered and bewildered. Lending him her arm, she walks him out. Not everyone in Proust is a monster. But just as in life, the heroes are far and few between.

“The core is a set of big, wonderful, difficult questions about life.”

So, Proust’s novel is in part about virtue, vice, prejudice, and folly. But most of Proust’s novel is not about that; the core of it is not about that. Instead, the core is a set of big, wonderful, difficult questions about life. Here are a few of them: how we can feel at home in the world; how we can find genuine connection with other human beings; how we can find enchantment in a world without God; how art can transform our lives; whether an artist’s life can shed light on her work; what we can know about reality, other people, and ourselves; when not knowing is better than knowing; how sexual orientation affects questions of connection and identity; who we are really, deep down; what memory tells us about our inner world; why it might be good to think of our life as a story; and how we can feel like a single, unified person when we are torn apart by competing desires and change over time.

Thinking about these questions won’t help us stop rising sea levels or rising authoritarianism, that’s true—but it will help us lead a richer inner life while we do so. And the experience of reading this amazing novel—the months or years we put into reading 3,000 pages, as difficult as delightful—does important things for us too. It shows us one shape a story of a life can take. It helps us understand ourselves, nudging us to ask ourselves questions we’d never even thought about before. It stretches our memory, rewarding us for holding an absurd amount of information in mind at once. And it gets us in the habit of neither fully trusting nor fully doubting what we read and hear, but instead assigning a probability. (Is it possible the heterosexual narrator fully understands the world of same-sex desire? I guess. Is it likely? Not so much.)

“The experience of reading this amazing novel—the months or years we put into reading 3,000 pages, as difficult as delightful—does important things for us.”

One of the characters in the novel, Albertine Simonet, has a mole on her chin. Or at least, that’s what the narrator tells us initially. Forty pages later, the narrator says he was wrong, and it’s really on her cheek. And six pages after that, he says it was on her upper lip the whole time. It’s hard to read brilliant prose like this without eventually developing a sixth sense for the possibility of error. And what, in 2022, could possibly be more useful than a sixth sense for the possibility of error?

And yet… isn’t all that still a bit decadent? A bit beside the point when the ice caps are melting? Maybe. But maybe we all need a little mental health break in between bouts with the forces of chaos and destruction. And Proust is really not a bad mental health break. (I know more than one person who devoted herself, during the pandemic, to finishing In Search of Lost Time.) Plus, in a way, it reminds us of what we’re fighting for: a world in which we get to think, again, about connection, enchantment, identity, and art. That, and not the imaginary golden age sold by the authoritarians, is the world we all need back.

In the desert of Chile, flowers produce seeds that can somehow live in the barren soil, surviving up to seven years of drought. When the rare rain finally begins to fall, the desert bursts into bloom, creating a “desierto florido.” One day, let us hope, we will emerge from this period of literal and figurative drought. And when we do, let’s hope there are people around to remind us of Marcel Proust, of Chinua Achebe, of George Eliot, of Toni Morrison… Proust loved plant imagery, and maybe he would have liked this one: we are the soil. We keep Proust alive. Maybe our flowers will bloom again one day, like the hawthorns and apple trees his character loves so much.

A version of this blog post was first published on Philosophy Talk.

Featured image by Faith Enck on Unsplash (public domain)

March 24, 2023

How to define 2022 in words? Our experts take a look… (part four)

How to define 2022 in words? Our experts take a look… (part four)

A tumultuous quarter—our experts choose the words for the final few months of 2022OctoberWe mentioned in our previous blog that mini-budget was the only word not related to the death of Queen Elizabeth II among the top ten words in our corpus that were significantly more frequent in September than the preceding months.

Taking place on 23 September 2022, Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng’s “mini-budget” sparked a series of economic events that were quickly called a doom loop—our word for October.

The term doom loop dates back to at least the 1980s in reference to a self-perpetuating downward spiral (broadly synonymous with vicious cycle). It is still often used in this sense. Examples in the corpus include:

“Increasing wildfires create a doom-loop that increases atmospheric carbon levels that risks worsening the next fire season” (The Hill, Oct 2021)“Those who apply for roles in real estate… are asked for experience before they are considered, creating a doom loop of rejection” (Personnel Today, June 2022)However, the term is increasingly used in economic contexts, as was the case last year. Usage of the word dramatically spiked in October 2022, largely with reference to the consequences of the UK government’s mini-budget in September. For example:

“Sterling crashed past $1.11 for the first time since 1985. Yields on UK government bonds, or gilts, blew out as their value collapsed, necessitating an emergency intervention by the Bank of England to stop a ‘doom loop’ of forced selling by pension funds” (Sunday Times, 2 Oct 2022)“A doom loop in the debt markets became so scary that the Bank of England had to make a massive emergency intervention for fear that some pension funds were about to go bust” (The Guardian, 2 Oct 2022).In this context, doom loop was almost eight times more frequent in October 2022 than at the same time the previous year. Other words related to doom loop that also spiked include mini-budget, gilt, unfunded, anti-growth, and Trussonomics, a word very occasionally used before 2022 but which shot up in prominence last year.

NovemberMoving onto November 2022, we saw the global spectacle that was the FIFA Men’s World Cup.

The tournament—eventually won by Argentina following a 3-3 draw and dramatic penalty shoot-out against France—was not without controversies. This included the treatment of migrant workers working to build the infrastructure for the competition and the treatment of LGBTQ+ people in Qatar, the host nation.

Our word for November is OneLove, a term that started life as the name of an anti-discrimination campaign by the Dutch Football Association in 2020. It is synonymous with rainbow-coloured armbands worn by team captains bearing its logo.

Before September 2022, the word did not have much of a presence in our corpus, but its prominence skyrocketed in November as the tournament drew nearer and attention towards anti-LGBTQ+ laws in the host nation grew.

In particular, the word was associated with reports that some teams planned to wear the OneLove armbands during games as a sign of protest, but this was abandoned after a very late warning from the governing body that any players doing so would be given a yellow card.

DecemberLast year’s severe weather events were not limited to the summer. The UK experienced heavy snow and freezing temperatures in December, and 10 days later across the pond a huge winter storm swept over large parts of the US and Canada.

This led to a large spike in use of the term bomb cyclone. Our word for December, bomb cyclone was over 23 times more frequent in December 2022 than December 2021.

The term dates to at least the early 2000s. For instance:

“Bomb cyclones have characteristics similar to hurricanes in their power and precipitation intensity… However, there are many major differences between the two storm types… Bomb cyclones have cold air and fronts associated with them, which hurricanes do not, and indeed, cold air is an essential ingredient for a bomb cyclone, while it kills a hurricane.” (The Halifax Daily News (Nova Scotia), 6 Dec. 2004)Before that, use of the word bomb to refer to a rapidly-developing, severe storm can be traced back to the 1940s:

“Nature flipped a weather bomb at Ohio today, catching the state unprepared for the worst snowstorm of the year.” (Norwalk (Ohio) Reflector-Herald, 11 Mar. 1948)The first use of bomb in a more specific weather sense—describing a rapidly developing severe storm in which barometric pressure at the centre of the storm drops by at least 24 millibars over a 24-hour period at or north of 60˚ latitude—appeared in 1980, in a paper written by Frederick Sanders and John R. Gyakum (“Synoptic-Dynamic Climatology of the ‘Bomb’”, Monthly Weather Review, October 1980).

Although the bomb cyclone is not a new phenomenon, the effects of climate change have led extreme weather events such as this to increase in frequency and severity, where previously they might have been once-in-a-generation occurrences.

December’s North American winter storm arrived on the heels of COP27 in November, an international climate conference which focused on ways to adapt to a changing global environment. Discussions of climate justice, climate reparations, and loss and damage also resulted in an increase in the usage of those terms.

A year in wordsAnd that concludes our look back at 2022 in words. It was certainly an eventful year and through it all our ever-changing language helped us to make sense of the world around us and brought us together. At Oxford University Press we continue to monitor the English language—we look forward to seeing what trends emerge this year…

Catch up with part one, part two, and part three of the Word of the Year 2022 blog series.

March 23, 2023

Macbeth, King James, and biting the hand that feeds you?

Macbeth, King James, and biting the hand that feeds you?

Possibly the most dangerous play William Shakespeare wrote was The Tragedie of Macbeth. The drama is packed with illegality: assassination of kings; prophecies about kings; supernatural women; and necromancy. To add to the danger, Shakespeare’s employer, King James, was a prickly patron of the performing arts and notorious for his sensitivity to slights, real and perceived.

Patrons of the theatre can have a confrontational attitude to the world of the stage and one such patron was King James VI of Scotland and I of England. James enjoyed plays and, prior to his elevation to the English throne, he kept abreast of English works as well as those in Scotland. Foreign observers considered the theatre to provide a valuable insight into the thoughts of King James, so much so that George Nicolson, the English agent at the Scottish court, gave his employer, the Secretary of State Robert Cecil, a list of plays. James was aware of the political implications of plays and also was sensitive to what he considered abuse or insults. A message from Nicolson to Robert Cecil’s father William, Lord Burghley on 15 April 1598 pleaded with his lordship:

It is regretted that the comedians of London should scorn [King James] and the people of [Scotland] in their play; and it is wished that the matter be speedily amended lest the King and the country be stirred to anger.

James also used the theatre in his contest for power with the church and the towns. The next year Nicolson wrote on 12 November 1599 to Robert Cecil that the ministers of the churches were forbidding their parishioners to attend theatrical performances. Furthermore, the bellows-blowers were claiming that two English actors named Fletcher and Martin were English agents who had been sent to sow discord between the king and the Church. King James responded by directly ordering the Edinburgh city council and the churches to reverse their bans and allow people to attend performances.

When King James VI of Scotland became King James I of England on 24 March 1603, he extended his patronage to the English theatre. In a royal patent of 19 May 1603 the troupe known as the Lord Chamberlain’s men became the King’s Men. The first name on the patent for the actors was Lawrence Fletcher (died 1608), apparently the same Fletcher who is mentioned in George Nicolson’s letter of November 1599. The very next name is William Shakespeare.

The King’s Men discovered that plays referring to Scottish events did not always meet with their royal master’s approval. There was, for example, the Tragedie of Gowry that the company performed twice in August 1604. This was otherwise known as the “Gowrie Conspiracy,” which was a supposed attempt on the king’s life in August 1600. When hunting near Falkirk, the king was approached by Alexander of Ruthven, the brother of the Earl of Gowrie, who said that a man with a pot of gold coins was at his residence called Gowrie House. James rode to the house and came to a room in a turret where there was an armed man. The king dashed to a window where he shouted “Treason” and his entourage broke into the house. Neither the assassin nor the man with the pot of gold coins was found and that led many people to question the king’s account. A generous interpretation is that there was an attempted assassination by Alexander Ruthven who wanted revenge for the execution of his father ordered by James’ regency council. The controversy might explain the cold reception the King’s Men received. A letter of 18 December from John Chamberlaine to his friend Sir Ralph Winwood noted:

The Tragedy of Gowry, with all the Action and Actors hath been twice represented by the King’s Players, with exceeding Concourse of all sorts of People. But whether the matter or manner be not well handled, or that it be thought unfit that Princes should be played on the Stage in their Life-time, I hear that some great Councellors (sic) are much displeased with it, and so ‘tis thought shall be forbidden.

Therefore, it is somewhat surprising that the Tragedie of Macbeth was performed so soon afterwards. Many critics believe that the play was written during the winter of 1606 and performed for the first time in the summer when James entertained his brother-in-law King Christian of Denmark. The play had many topics of possible offense to King James; so why did Shakespeare write Macbeth?

One possible answer is that the Tragedie of Macbeth told history the way that King James wanted it to be told. The drama was based on the historical record. All the main characters and the progression of events—murder of Duncan, flight of Malcolm Canmore, and his eventual triumphant return—are historically attested, with one exception: Banquo. The murder of Duncan by Macbeth could have been seen by James as parallel with the murder of his father Henry Darnley, while the victory of Malcolm was similar to his triumph over the Scots and English nobility. James’ fear of witches can be judged by his Demonology of 1599, where he sees them as enemies of humanity. Even prophecy was dubious and, since the fifteenth century, any prophecy that juxtaposed royalty with chronology was illegal. In the play, however, all these unsavoury elements are destroyed. The prophecies are shown to be deceitful and the witches deliberately mislead Macbeth. Finally, the world is put right when Malcolm avenges his father.

Like Robert Cecil, William Shakespeare understood how the theatre offered an insight into the mind of a prince. The Tragedie of Macbeth was drama of the sort that King James wanted and for which he paid.

March 22, 2023

Spring gleanings and a partial spring cleaning

Spring gleanings and a partial spring cleaning

Borrowed words and a few related subjectsI have received several letters dealing with borrowings and cognates (that is, related forms). I hasten to thank our correspondents for their questions and those who did not ask me anything but stated that the blog helps them in teaching language, spelling, and (in particular) etymology. Friendly feedback is a rare commodity. Only irritation and abuse are common and cheap.

Canoose, “the end piece of a loaf of bread” Does this last piece of bread look like a canoose?

Does this last piece of bread look like a canoose?(Via PxFuel, public domain)

Much to my surprise, I know the word’s etymology. I am surprised because the great Dictionary of American Regional English does not seem to feature canoose, though the Internet reports its occurrence in several places. In any case, the derivation from German cannot be doubted, that is, the word was brought to America by German immigrants (possibly, but not certainly, from the north). The following German forms have been recorded: Knust, Knaust, and the diminutive Knäust-chen (chen is a suffix, as in Mädchen “girl, maiden” and Gretchen), with exactly the same meaning as canoose. Numerous German words beginning with kn– designate thick objects. Not improbably, the meaning of the noun Knaus developed from “fat; conceited” to “stingy.” In English, kn– does not occur initially, except when you go “c’noeing”; hence the intrusive vowel a between k and n. (Words like knock, knead, and the rest bear witness to the existence of kn– in the past. We still tolerate kn if a syllable boundary divides k and n, as in ack-nowledge or rock’n’roll. No one knowns for sure why kn– changed to hn, and then, predictably, to n. But this change does not affect the etymology of the American noun.)

Beginning and end Bo-bo? It will go away.

Bo-bo? It will go away.(Via Pexels, public domain)

The non-Germanic cognates of end have been known for a long time. Those are Sanskrit ántas “end, boundary; death,” Greek anti “opposite,” and others. The Hittite adjective hanza “front” (mentioned in the letter) is close. In my post, I ignored all of them (dictionaries list them with or without questions marks), because I tried to show that the words for “beginning” and “end” often have the same semantic nucleus. This circumstance makes their origin especially interesting. By contrast, a tie between begin and the root found in generate is out of the question. Why should the earliest Germanic speakers have isolated the stem of the Greek word, changed the vowel, and shifted the sense from “generate” to “start”? Also, as I have pointed out more than once, if a word with initial g had been borrowed very long ago, it would have undergone the First Consonant Shift and become ken. Finally, the gen– root does have a legitimate cognate in Germanic: such is English kin (Gothic kuni). It is also useful to remember that unlike children picking up pebbles on a beach, people do not borrow words in an unpredictable, haphazard manner. (Here is a good root, why not borrow it?) I am afraid that our correspondent and I have been talking at cross-purposes for a long time.

Bubu, kibosh, trollTo repeat a piece of trivial information: for almost every word of a given language one can probably find a similar-sounding word in any other language with a more or less matching sense. (Thus, an old correspondent of mine pointed to a similarity between wīf, the etymon of wife, and a Hebrew word. Well, things happen.) English bubo is mainly remembered because of the phrase bubonic plague. Greek boubōn means “groin; swelling in the groin.” The word made its way into Medieval Latin and from there into English. Our correspondent cited a rather similar Biblical Hebrew word (Exodus 9: 9, 10: in translation—I always use the Revised Version—a boil breaking forth). Is there any connection? Dictionaries derive the Greek word from a root “to swell.” As usual, one wonders whether such a root ever existed. Words like bubu, baba, and bobo are typical baby words (like baby itself), and the name for a swelling, something that hurts, could very well be a word used by adults while addressing and soothing infants.

Putting a kibosh on.

Putting a kibosh on.(By puuikibeach, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

Kibosh has recently attracted great attention. See the book by Gerald Cohen, Stephen Goranson, and Matthew Little On the Origin of Kibosh (2020). Our correspondent, who is aware of the connections between the speakers of Greek and Hebrew in the ancient world, cites kabash “subdue” in Exodus 1: 28 (in translation: …and subdue it…). He also refers to the use of the word in Arabic. Could this verb enter Yiddish and be borrowed by English? The Yiddish etymology of kibosh has been suggested many times and even accepted by some authorities. In the aforementioned book, a special chapter is devoted to the refutation of this etymology. The main problem, as I understand it, is that the supporters of the Yiddish origin of kibosh have to explain the derivation of the entire phrase, rather than of the enigmatic word. Somebody had to PUT A KIBOSH (apparently an object) on somebody or something. An isolated verb could hardly become a noun and end up as part of the phrase we know (kibosh never occurs outside the idiom in question). See other arguments along the same lines in the aforementioned book.

English troll, “to move back and forth.” The letter I received concerns itself with the hypothesis that the verb may go back to Vulgar Latin tragulare “to trace.” The origin of troll (the verb not the noun!) is doomed to remain guesswork, partly because the word and its lookalikes surfaced late and partly because, with its initial tr-, it may be sound-symbolic. But in Germanic, it resembles several other words outside English and thus seems to be more at home than in Romance. Besides, troll may be related to a few words beginning with s, such as English stroll and German Strolch “vagabond.” It seems that the old opinion (traditionally supported by both Germanic and Romance historical linguists) deriving the verb troll from Germanic still stands.

Three g-wordsGhee “clarified butter made from buffalo’s milk” is a seventeenth-century borrowing from Hindi (the Sanskrit root means “to sprinkle”). Grime came to English from Middle Low German or Middle Dutch. I think Earnest Weekley was the first to suggest that Old English grīma “mask” is related. If grime goes back to the root meaning “to rub; anoint,” then Christ is indeed related. The root of grisly (a Germanic word) means “horror,” and the word can therefore be allied to many other gr-words for fear; horror.

Finally, I am grateful for the comment that informed me that the word sib is still very much alive in Modern English. I believed that it rarely occurs in everyday speech but was, apparently, wrong.

I was also asked about the origin of rake and scratch. I’ll deal with both words next week.

Featured image by USFWS/Steve Hillebrand (CC BY 2.0)

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers