Oxford University Press's Blog, page 52

May 2, 2023

A listener’s guide to Rhythm Man [playlist]

A listener’s guide to Rhythm Man [playlist]

Rhythm Man: Chick Webb and the Beat that Changed America is the first full biography of the innovative 1930s Swing Era drummer/bandleader, known as the “Savoy King.” Rhythm Man traces Webb’s footsteps from his birthplace in East Baltimore to Harlem and on to national fame, with his popular big band and a young vocalist named Ella Fitzgerald, who went on to become the “First Lady of Song.”

Listen to the playlist and read on to trace Webb’s legacy on records and radio, from 1929 to 1939:

1. “Dog Bottom”Recorded in 1929, “Dog Bottom” is one of Chick Webb’s first records with his Harlem Stompers (the record label used “Jungle Band” as a pseudonym on record by several Black bands at the time). Webb and his 10-piece dance band are playing a Charleston-style stomp, driven by banjo, tuba, and Webb’s steady drumming, a vivid example of pre-swing jazz played by Harlem’s finest young musicians.

2. “Let’s Get Together”By 1933, Chick Webb’s Savoy Orchestra was playing a full-out, forward-moving swing rhythm. This arrangement by composer/arranger/alto player Edgar Sampson sets off a clever riff-based call-and response—Sampson’s specialty. This tune became the Webb Orchestra’s theme song soon after the record’s release in early 1934.

3. “Stompin’ at the Savoy”“Stompin’ at the Savoy” was also by Edgar Sampson, whose arranging style helped define the sound of Chick Webb’s band as it expanded into a powerhouse swing dance band. This tune became a staple of the Webb Orchestra’s repertoire at Harlem’s Savoy Ballroom, where the band reigned for the rest of the decade.

4. “Don’t Be That Way”This tune, also by Sampson, was another signature piece for Webb’s band, especially when performed by Ella Fitzgerald after lyrics were added later. The song was soon covered by Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw, and other popular white big band leaders, raising still-controversial issues of race and appropriation in the music business, themes explored in Rhythm Man.

5. “(If You Can’t Sing It) You’ll Have to Swing It”This 1936 recording—better known as “Mr. Paganini”—was one of Ella Fitzgerald’s first solid hits for the band. It’s got the lyrics of a 1930s novelty number—“Mr. Paganini, don’t you be a meanie…”—and shows off Ella’s talent as one of the first swing vocalists at the moment that swing rhythm and dance—the Lindy Hop—were sweeping the country.

6. “Go Harlem”“Go Harlem” displays Webb’s command of the band from his drummer’s throne. His playing delineates all the music’s phrases and dynamics of Sampson’s arrangement; meanwhile Webb is the perfect complement for the successions of soloists. He brings everyone together at the end, closing with cascading cowbells.

7. “Vote for Mr. Rhythm”Webb’s band swings out on this 1936 election year novelty, hitting all the right notes as Ella sings: “Now when I say vote for Mr. Rhythm, you all know I mean Chick Webb!” and that victory means, “Soon we’ll all be singing, ‘Of Thee I Swing.’”

8. “Harlem Congo”Recorded in fall 1937, this track displays the innovative virtuosity of Chick Webb throughout. He swings the band like crazy, and for the first time on records lets loose a 24-bar drum solo. He brings down the tempo and pace of the piece majestically, and concludes with a startling, yet also gorgeous, cymbal crash.

9. “Bei Mir Bist Du Schön”This song has an extraordinary history. It began as a Yiddish song written for a musical comedy, then became a major hit by the Andrews Sisters sung in English, though it was banned in Nazi Germany when its Jewish origin was discovered. Chick Webb’s Orchestra swings klezmer, while Ella’s voice soars with a bit of Yiddish lilt in her scatting.

10. “Liza (All the Clouds Will Roll Away)”This is Webb’s third recorded version of George Gershwin’s “Liza,” from a January 1939 radio transcription. Like “Harlem Congo,” here is the virtuosic Webb— an orchestra all by himself! Playing across his instruments —drums, cowbells, woodblocks, bells, and more— he pulls out all the stops, a blueprint for future drummers in big bands, rock bands, and beyond.

11. “A-Tisket, A-Tasket”Ella Fitzgerald started fooling around with rocking this nursery rhyme when the band was at a Boston nightclub in 1938. Van Alexander, Ella’s main arranger for Webb, crafted it into the band’s biggest hit ever. Ella and the band transformed this rhyme to gold with Ella’s buoyant swing, and a shuffle rhythm bordering on early rock’n’roll.

12. “One O’Clock Jump”Webb often paid tribute to other bandleaders, covering their best tunes. It was a challenge to compete with Count Basie’s band, which Webb and Basie did in an epic band battle in 1938. Here, Webb pushes the beat and so do his soloists—to the delight of generations of Lindy Hoppers.

13. “T’Aint What You Do but the Way That You Do it”Webb’s band swings out on this Jimmie Lunceford hit, while Ella wittily mangles the lyrics—“You’ll learn your ABCs, and then your DFGs.” A perfect snapshot of the era, Ella takes one of her lengthiest scat solos on record to date—upbeat and adorable.

14. “Let’s Get Together”This playlist closes with two broadcast recordings from the Southland Cafe in Boston, in May 1939. On this clip from the band’s theme song, Webb pounds out a forceful beat, encouraged by the wild crowd. Nobody on the dance floor could have suspected that Webb’s health was failing, and he would pass away a few weeks later.

15. “My Wild Irish Rose”Also recorded at Southland, Webb takes this sentimental popular song to stratospheric heights, playing it at what the Lindy Hoppers called his “killer tempo.” Webb’s stupendously musical pyrotechnics are aimed to whirl into everyone’s heart.

For more information on the life and legacy of Chick Webb, read Stephanie Stein Crease’s Rhythm Man: Chick Webb and the Beat that Changed America.

April 30, 2023

Rethinking the future of work: an interview with Joe Ungemah

Rethinking the future of work: an interview with Joe Ungemah

Dr Joe Ungemah, author of Punching the Clock, examines whether the future of work is compatible with maintaining the social fabric of the workplace and the psychological needs of workers. His work seeks to make connections between the psychology underlying human behavior and the social world we live in, translating scientific theory into simple and straightforward insight that can be applied in the workplace and beyond.

What are the key differences between pre-and post-pandemic work?The first thing to remember about the difference between pre- and post-pandemic work is that the change has been felt differently by workers across jobs and industries. Service workers or those working jobs that are location dependent do not have the same ability to work remotely and therefore, their ways of working may be relatively unchanged. Yet for those in office environments, trends like remote, hybrid, and gig work have left a permanent mark on the workplace.

From a psychological vantage-point, the social distance created by these new ways of working poses challenges to the establishment of common social norms, shared identity, and clarity around performance expectations, as the cues and opportunities for social interaction are limited. Counteracting promises of increased flexibility, many workers are feeling the fatigue created by endless hours of remote meetings and the temptation for work hours to creep into personal time. In this way, behavior has not kept pace with changes in technology.

How can academic research make a practical improvement to worker well-being?There is a wealth of psychological literature on behavior and motivation that is ready for application into the workplace. There are so many insightful experiments from social and occupational psychology specifically, on the big topics like altruism, obedience, and conflict, that have not made their way into leadership development programs or practical advice for companies. If companies were to adopt a more humanistic perspective, by digging into the human drivers that corporate policies and procedures influence, greater employee well-being is likely to result. Right now, employees are calling out for a combination of financial, social, emotional, and physical well-being, which can be better informed by looking across disciplines and considering the workplace just like any other social environment where human drivers are at play.

How do we develop and support the next generation of leaders in a more remote world?“If companies were to adopt a more humanistic perspective … greater employee well-being is likely to result.”

Remote, hybrid, and gig work pose distinct challenges for leaders to navigate. They will likely face employees who have a transactional mindset, less developed social networks, and inconsistent understandings of work expectations. Yet, they are likely to be more open to share their personal lives and have greater opportunities to work across geographies and cultures. As such, leaders will need the time and capability to set and communicate clear vision and goals, help employees navigate the organization, and capitalize fully on opportunities for social interaction. At the same time, these leaders might require coaching for themselves on how to attend to their own needs, even as they help others.

How does increased flexibility impact employees and organizations?Much of the attention on the topic of flexibility has focused on physical location (i.e. working from home instead of the office), however this is just one type of flexibility. Employees are also calling out for a say on when they work, with control over start and end times or the ability to work a 4-day week, prioritizing this type of flexibility over physical location. When flexibility is not provided, research by EY (Work Reimagined Employee Survey, 2021) discovered that 54% of employees were willing to quit their jobs. Employers have responded by providing leniency on working hours, offering unlimited paid time off, and providing home office equipment, yet at the expense of empty and eerily quiet offices.

What do you think the world of work will look like in 10 years?“When flexibility is not provided, research by EY discovered that 54% of employees were willing to quit their jobs.”

I think in time, we will see the pandemic as just one step along a journey away from the traditional office. Twenty years ago, offices were built on a need for record keeping. Pushes towards a paperless office made file drawers disappear and bookshelves go empty, yet the office hung on due to needs for employees to access computers and other technology. Laptops and cell phones took that need away, leaving personal interaction and collaboration as the core purpose. The pandemic taught us that even that was not sacred and video conferences were an effective mechanism to get work done.

We have seen so much change in such a short time that it is difficult to predict what the future will hold. It is only in hindsight that we can see the progression of technology and how it can fundamentally change behavior and needs.

Featured image: Canva

April 28, 2023

Studying ancient tsunamis is all about glasses

Studying ancient tsunamis is all about glasses

If you go back a mere 40 years or so, not a long time really, then you pretty much arrive at the time when the modern study of ancient tsunamis began. Before then there had been some work, but it really kicked off with Brian Atwater and his work on the 1700 CE Cascadia earthquake and tsunami. His seminal work pieced together all the evidence that basically said there was a big earthquake and it generated a huge tsunami. The evidence included the now-famous ghost forests you can find along the Washington State coast if you know where to look. It also included a long thin strip of sediment sandwiched between peat layers like a jam sponge cake that you can easily pick out on river banks as they near the sea. This evidence had been there for nearly 300 years waiting for someone to come along and have a Eureka moment. This is where the glasses come in.

Like anyone who is myopic, you need glasses to see properly. It is the same with a scientist. Scientific discovery isn’t as you see in the movies where handsome actor A says to an even more ridiculously handsome actor B something like “I know what this is, look at that rock, it’s obvious…” OK, so that was a B-movie, but the point is that invariably with the study of ancient tsunamis nothing is obvious. While it is often the case today that a tsunami researcher wanders down to a bit of coast, pokes around a bit, and finds an ancient tsunami, this does not mean that it is easy. A lot of work has gone in before a spade has been put into the ground. Maps, satellite images, historical documents, academic papers, and old traditions have all been studied to try and make every moment you spend “on the ground” actually worth it. After all, research funding does not grow on trees and it needs to go a long way.

In the early days of tsunami research, it wasn’t exactly the Wild West but the world’s coastlines were pretty much your oyster. They were a blank sheet. We knew where a lot of historical tsunamis had happened, but when you dipped into prehistory there were no newspaper accounts, no convenient photos or tweets on the internet. It was down to science. The downside, though, was that unlike today where you can take university courses about tsunamis or even do a thesis about them, in the beginning of the study of ancient tsunamis there was no rule book, no textbook to learn from; we were making the rules up as we went along.

“The more we learn, the more we change our way of seeing the evidence around us.”

In the beginning, our eyes were open but not seeing: what were the signs that indicated that an ancient tsunami had been here? Many times over the years, I have been asked what a tsunami deposit (the geological evidence) looks like. That is a bit like asking “how long is a piece of string?” There is no one-size-fits-all answer. I have come up with what I feel is about the only reasonable answer to that question: it is a deposit that is out of place. A bit like a weed in garden, there is something not quite right about it. In many cases it is obvious; you are standing two miles inland on the edge of a river bank and can see a beautiful yellow sandy layer sandwiched between two dark brown peats. The sandy layer extends as far as the eye can see in both directions, it is chock full of sea shells, and lies on top of a layer of dead trees all pointing inland in the direction they fell.

OK, that might be a bit of a researcher’s dream, but there are deposits like that. A layer of sand that has come from the sea, bowled over a forest, and deposited sand and shells two miles inland. You don’t have to be a genius to figure that out—or rather, you don’t have to be one now, but when we started it was head-scratchingly interesting and needed a lot of laboratory analysis to work out all the details. We have “banked” all of that information now and so do not need to reinvent the wheel for some types of deposit—in a sense, that information represented the first pair of glasses. We could see better and we could find tsunami deposits!

Through the years my “glasses” have been changed regularly. As the years go by, the banked information from a seemingly endless variety of deposits has grown and so what used to be seemingly impossible to figure out is now much easier to recognize. However, all that has really happened is that we have moved on to harder cases or revisited cases that were less obvious the first time around now equipped with new insights. The more we learn, the more we change our way of seeing the evidence around us.

“There is a saying in earth science: ‘the present is the key to the past.’ Well, our work puts a spin on that: ‘the past is the key to the future.'”

There have been several occasions where I have given myself a hearty head smack when I have revisited a site and the veil has been lifted by my new glasses. It is good to know that we do not know everything, but equally it is good to know that we are learning more every year. If nothing else, we are keeping the tsunami optician in business and in doing that we increase our understanding of these devastating events. There is a saying in earth science: “the present is the key to the past.” Well, our work puts a spin on that: “the past is the key to the future.” Bigger tsunamis have occurred in prehistory than we have ever seen in historic time. We need to learn as much about these as possible in order to be prepared for them in the future, and for that there will continue to be a need for new glasses.

April 27, 2023

Eight fun facts about Bibles at OUP

Eight fun facts about Bibles at OUP

Bibles have had a long history at our Press; in fact, Oxford’s Bible business made OUP a cornerstone of the British book trade, and, ultimately, the world’s largest university press. When you’ve been in the Bibles business for this long, you’re bound to have some interesting anecdotes. Read on for some fun facts in the history of Bibles at OUP.

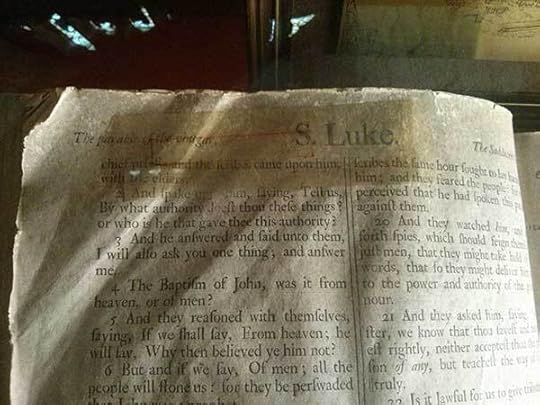

1. OUP has been printing Bibles for over 300 yearsIn 1636, Archbishop Laud, Chancellor of the University, obtained the right to “print all matter of books” from Charles I. However, for a generation, Oxford signed away its right to print Bibles to the Stationers’ Company of London. In 1675, under John Fell, the currently unbroken tradition of Bible printing in Oxford began with the quarto bible.

2. Home of the Vinegar BibleThe infamous “Vinegar Bible” was printed by OUP in 1717, when the chapter heading of the Gospel of Luke, Chapter 20 was printed as “The Parable of the Vinegar” instead of “The Parable of the Vineyard.”

Photo by Victuallers. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons3. The birth of Bible paper

Photo by Victuallers. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons3. The birth of Bible paperOxford was the first Bible publisher to refine the use of really thin, strong paper, called Oxford India paper. Running about 1,000 pages per inch, Bibles using this paper were known for their portability and lightness.

4. Not so interdenominational…While we produce numerous Catholic Bibles today, this wasn’t always the case. When it was suggested in 1895 that we should produce a Roman Catholic Bible, the Press Delegates responded that they did not “think it desirable that such a work should be issued with the University Press Imprint.”

5. The New York office owes its existence to BiblesBibles played a huge role in the existence of OUP in the USA. The Press opened the New York office in September 1896, primarily to facilitate sales of Bibles in the US market.

6. 100 years of annotated BiblesOxford’s history of annotated Bibles goes back to 1907, when we signed Cyrus Ingersoll Scofield to create a new bible product for the Press. What was eventually called The Scofield Bible introduced a new system of cross-references, or connections between one Bible verse and another on the same topic or using similar wording. It was also the first Bible to publish commentary on the same page as Bible text.

7. A coronation Bible too heavy to carryWhile we’ve produced Bibles for several coronation ceremonies (including the upcoming coronation of King Charles III), we had to produce two for the Coronation of George VI in 1937. The first, a particularly extravagant Bible, proved too heavy to carry and had to be replaced at short notice by a smaller bible. The Archbishop of Canterbury, Cosmo Gordon Lang, was “very sorry” that all the care OUP had taken had “brought about these complicated problems” but added, “I cannot but wish that you had given some more consideration to the physical infirmities of those who would have to carry it.”

8. A Presidential connectionOn 20 January 2009, Barack Obama was sworn in on an Oxford bible that was previously used for the swearing in of Abraham Lincoln on 4 March 1861. Because the Lincoln family bible had not yet been unpacked after the famous 10-day train trip across the country, the sixteenth president of the United States was sworn in on an 1853 Oxford KJV, which had been borrowed from (or purchased specially by, according to some accounts) William Thomas Carroll, Clerk of the US Supreme Court.

Public domain image via Wikimedia

Public domain image via WikimediaFeatured image: OUP Bible Library, OUP Archives, photo by Joseph Kennedy.

April 26, 2023

Hooker, as promised

The promise, referred to in the title, was made last week (19 April 2023) in connection with the etymology of the verb filch. I also indicated that my exposition would be written in honor of and as a tribute to Professor E. Peter Maher, who had explored the history of hooker in exhausting detail. Everything I will say below, except for a few remarks in brackets, will be borrowed from his book-length publication “The Unhappy Hookers; Origin of hooker ‘prostitute’,” published as a special issue of the monthly journal Comments on Etymology 50, 6-7, 2021 (58 pages, with numerous illustrations and an exhaustive bibliography).

Reverend Thomas Hooker, the founder of the Connecticut colony

Reverend Thomas Hooker, the founder of the Connecticut colony(Thomas Hooker by Frances L. Wadsworth, Daderot, via Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

Maher’s main point is that hooker “prostitute” swept (American) English only after the publication of Xaviera Hollander’s (XH) book The Happy Hooker (1971). Twenty-five million copies were sold, and “everybody” read it. The author’s real name was Vera DeVries. There is an entry on Hollander in Wikipedia, and I’ll dispense with retelling it. XH of course did not coin the word hooker. Occasionally, it even had some connections with sex, but before 1971, it had not yet become common property (far from it). In his youth, Maher did not know hooker “prostitute.” Family names are often incredibly offensive, but the many Hookers faced no opprobrium. For example, the founder of the Connecticut colony was the Rev. Thomas Hooker and Harriet Beecher Stowe had a sister who was a Hooker, Mrs. John Hooker, i.e., Isabella Beecher Hooker.

At one time, hookers made hooks, just as carters made carts. But hookers also hook (players play, hookers hook, etc.). That is why thieves were called hookers. The Century Dictionary (a great American reference book) cites hooker ~ hoker “thief,” with an example from a 1598 dictionary: “A cunning filcher, a craftie hooker”, and Maher quotes Mark Twain: “…while Aunt Polly closed with a happy scriptural flourish, Tom hooked a doughnut,” that is, he “filched” it. Maher continues:

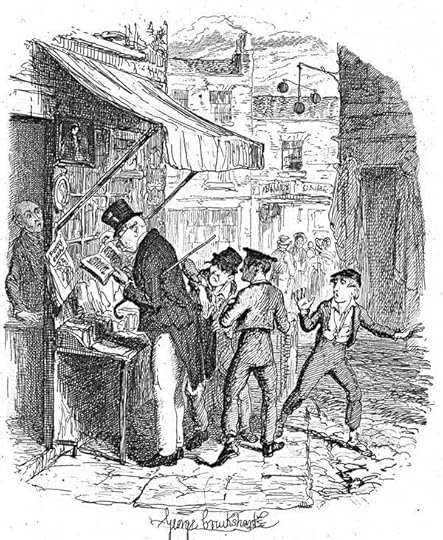

“Equipped with hooks, thieves snatched valuable clothes and bed-clothes through open windows and doors. Poor girls and boys of England and Ireland could be sentenced to transportation to Australia for stealing a handkerchief. [Those who have read Oliver Twist will know how true this statement is.] Shoplifters were termed hookers from their modus operandi.”

Indeed, they behaved like filchers (sorry for harping on the familiar note).

Mr. Brownlow’s handkerchief is being stolen

Mr. Brownlow’s handkerchief is being stolen(From Oliver Twist by George Cruikshank, via Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

Hooker “a glass of whiskey” is “a word of unknown origin.” Was it not called this for its intoxicating purposes: it “sort of” hooked the drinker, did it not? We also find hooker “a boat for fishing with hook rather than net” (from Dutch). Amusingly, as late as 1979, there was an Irish ferry called The Happy Hooker. “The captain must have heard of Xaviera and hoped to attract American tourists,” Maher noted. Enter General Joseph Hooker (1814-1879). The morals of the servicemen in his army were notoriously low. Yet despite the obvious connection, the word hooker owes nothing to the Union general. Some websites keep clinging to this discredited etymology.

Maher found only one pun on hooker before World War II. Even before the 1960s, hooker appeared very rarely in magazines, and the word never made anyone blush. [By blushing I mean unwanted but inevitable associations. For instance, when we speak about the poop on a ship or see the word nincompoop, we cannot suppress our knowledge of what poop usually means.] Later, the word, though not yet vernacular, gained some popularity, but only in the early seventies, after Xaviera, did “all whoredom break loose.” That the 1901 volume of the OED missed hooker causes little surprise: such “vulgarisms” were not allowed in print and could be smuggled in only in the hope of being overlooked, as happened to the bird name windfucker, but more probably, the OED’s team did not have any convincing citations of the word. Once the censorship of this type was abolished, prohibited nouns and verbs swamped the printed page.

A proud hooker.

A proud hooker.(Via Pxfuel, public domain)

The OED team was of course familiar with John Russell Bartlett’s Dictionary of Americanisms. The post-World War Two Second Supplement to the Oxford English Dictionary, cited hooker, as it cited the F-word, and referred to the relevant passage from Bartlett: “Hooker … strumpet, a sailor’s trull, so called from the number of houses of ill-fame frequented by sailors at the Hook (i.e., Corlear’s Hook) in the city of New York.” Maher remarks that Bartlett’s hooker indeed designated someone living or frequenting Corlear’s Hook in New York. [It was a word like Londoner or New Yorker. There is a village in Buckinghamshire, England, called Wing. I assume that its inhabitants are called Wingers. Some of them may be wingers.] Corlear Hook’s hookers were prostitutes, but that local name is not the beginning of the now universally known word. Bartlett discarded his entry on hookers as sailors’ trulls from the fourth and the fifth edition of his dictionary.

Though it is true that in the works of Hemingway and his contemporaries, hooker, denoting a woman who could be easily hooked, does occur at irregular intervals, those were occasional coinages. They were easy to understand, but their occurrences do not show that English had an accepted noun hooker “prostitute.” In 1845, a young man tells a friend that “he will find any number of pretty Hookers in the Brick row not far from French’s Hotel,” who do it for love (!). The story sounds almost too good to be true, but those selfless Hookers were obviously not prostitutes. In any case, they were not the immediate ancestors of Xaviera’s happy hookers. Maher’s ironic comment is: “Prostitutes hook a john. Honest women hook a husband.”

Hooker “prostitute” also turns up in later American English, and Maher quotes a passage from a tale told by an Englishman, a naïve outsider but not an idiot, about an encounter with a woman in 1863, whom, from his description, his interlocutors identified as a “hooker,” that is, a prostitute. Quite a few later occurrences make this sense of hooker certain. More examples follow that show the same: hooker “prostitute” existed, but though people understood it (the context was unambiguous and could not be misinterpreted), it remained a rarity.

Bonnie and Clyde

Bonnie and Clyde(Library of Congress, via Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

“The Unhappy Hookers…” is a riveting personal memoir by a seasoned linguist who did not set out to “prove” anything. His aim was to dispel etymological myths by investigating the history of one word, and he did it in an exemplary manner (but I in general have a soft spot for monographs devoted to a single word, be it ginger, shyster, kibosh, or hooker). I’ll now quote a postscript, apparently, added in 2021:

“As I write this I’m a geezer though still ambulatory. My Cold War army hitch was over fifty years ago now, but it seems like yesterday. I can still see it, hear it, smell it, taste it. None of us in the ranks called a prostitute a hooker then. Novelists Wolfe and DosPassos and Steinbeck, born between 1898 and 1902, were now in early middle age. They were writing their novels in the twilight of the Civil War veterans. Some sixty years after the end of the Civil War Bonnie and Clyde were on the road. I was a baby. In this span of time the H-word spawned and spread….”

The final picture on p. 49 is of Bonnie and Clyde.

Featured image by Anthony Mac Donnacha via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

April 25, 2023

Digital dilemmas: feminism, ethics, and the cultural implications of AI [podcast]

Digital dilemmas: feminism, ethics, and the cultural implications of AI [podcast]

Skynet. HAL 9000. Ultron. The Matrix. Fictional depictions of artificial intelligences have played a major role in Western pop culture for decades. While nowhere near that nefarious or powerful, real AI has been making incredible strides and, in 2023, has been a big topic of conversation in the news with the rapid development of new technologies, the use of AI generated images, and AI chatbots such as ChatGPT becoming freely accessible to the general public.

On today’s episode, we welcomed Dr Kerry McInerny and Dr Eleanor Drage, editors of Feminist AI: Critical Perspectives on Data, Algorithms and Intelligent Machines, and then Dr Kanta Dihal, co-editor of Imagining AI: How the World Sees Intelligent Machines, to discuss how AI can be influenced by culture, feminism, and Western narratives defined by popular TV shows and films. Should AI be accessible to all? How does gender influence the way AI is made? And most importantly, what are the hopes and fears for the future of AI?

Check out Episode 82 of The Oxford Comment and subscribe to The Oxford Comment podcast through your favourite podcast app to listen to the latest insights from our expert authors.

Oxford Academic (OUP) · Digital Dilemmas: Feminism, Ethics, and the Cultural Implications of AI – Ep 82 – The Oxford CommentRecommended readingLook out for Feminist AI: Critical Perspectives on Algorithms, Data, and Intelligent Machines, edited by Jude Browne, Stephen Cave, Eleanor Drage, and Kerry McInerney, which publishes in the UK in August 2023 and in the US in October 2023.

If you want to hear more from Dr Eleanor Drage and Dr Kerry McInerney, you can listen to their podcast: The Good Robot Podcast on Gender, Feminism and Technology.

In May 2023, the Open Access title, Imagining AI: How the World Sees Intelligent Machines, edited by Stephen Cave and Kanta Dihal publishes in the UK; it publishes in the US in July 2023.

You may also be interested in AI Narratives: A History of Imaginative Thinking about Intelligent Machines, edited by Stephen Cave, Kanta Dihal, and Sarah Dillon, which looks both at classic AI to the modern age, and contemporary narratives.

You can read the following two chapters from AI Narratives for free until 31 May:

Chapter 8: “Enslaved Minds: Artificial Intelligence, Slavery, and Revolt” by Kanta DihalChapter 9: “Machine Visions: Artificial Intelligence, Society, and Control” by Will SlocombeOther relevant book titles include:

Relationships 5.0: How AI, VR, and Robots Will Reshape Our Emotional Lives by Elyakim Kislev Human-Centered AI by Ben Shneiderman (Read Chapter 16: “Social Robots and Active Appliances” for free until 31 May)You may also be interested in the following journal articles:

“AI ethical bias: a case for AI vigilantism (AIlantism) in shaping the regulation of AI” by Ifeoma Elizabeth Nwafor from the Autumn 2021 International Journal of Law and Information Technology“My AI Friend: How Users of a Social Chatbot Understand Their Human–AI Friendship” by Petter Bae Brandtzaeg, Marita Skjuve, and Asbjørn Følstad from the July 2022 Human Communication Research (Open Access)“Persuasion in the Age of Artificial Intelligence (AI): Theories and Complications of AI-Based Persuasion” by Marco Dehnert and Paul A Mongeau from the July 2022 Human Communication ResearchFeatured image: ChatGPT homepage by Jonathan Kemper, CC0 via Unsplash .

April 24, 2023

Open secrets? Where to look for the history of colonial violence

Open secrets? Where to look for the history of colonial violence

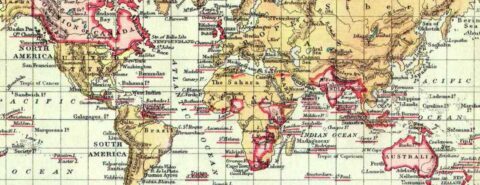

It has now been more than a decade since the Foreign and Commonwealth Office was forced to reveal the existence of a secret archive at the Hanslope Park intelligence facility in Buckinghamshire. As decolonization accelerated in the 1950s and 1960s, hundreds of thousands of files were wrenched free from archival procedures that would have made them accessible to officials of the new states that emerged from the empire or to members of the public in Britain. A 1961 Colonial Office directive made clear that this special handling was specifically intended for materials that “might embarrass Her Majesty’s Government.” Roughly 20,000 such files ended up at Hanslope Park while many more were destroyed on the spot.

Since 2011, this collection has gradually been transferred to the National Archives of the United Kingdom and opened to the public. The consensus among historians is that revelations from the files so far have been incremental rather than revolutionary. But unsettling questions about the politics of historical writing continue to linger. If it had not been for a lawsuit brought by survivors of the brutal British counterinsurgency in 1950s Kenya, the Hanslope Park archive would likely never have come to light at all. How can the history of British imperialism—and above all the “embarrassment” of its violence against British subjects—be salvaged from archives painstakingly crafted and sanitized by imperial rulers? Of course, all historians must construct their narratives from fragments of the past; they must likewise read against the grain of potentially misleading documents. But with seventy-five linear feet of colonial files apparently “lost” by the Foreign Office and another 600,000 “non-standard” files yet to be released, one has to ask whether a source base already overwhelmingly biased toward literate, Anglophone men can tell us much beyond the aspirational self-image of the ruling elite. The conspicuous black holes of official suppression threaten to make at least some aspects of imperial history one of those subjects, like the royal family or the Kennedy assassination, where constraints on scholarship have left a flourishing field to speculation and lore.

“The seductive drama of secrecy and revelation… [is] an active impediment to understanding Britain’s relationship with colonial violence.”

How to write a worthwhile history of empire after Hanslope Park was something I wrestled with when starting work on the book that would become Age of Emergency. I soon realized that the seductive drama of secrecy and revelation was not just a distraction but an active impediment to understanding Britain’s relationship with colonial violence. Too many observers had drawn the wrong conclusion from the archive scandal: that the brutality of imperial rule had long been “suppressed and buried,” as critic Paul Gilroy put it, and that the horrifying truth was only now emerging into the light of day. Besides overstating the importance of the Hanslope files themselves—and perhaps falling prey to what has been called the “fetishism” of secret files—these kinds of responses painted a highly questionable picture of the British past. My thoughts turned first to the 1950s: a period marked not only by intensely violent counterinsurgencies in colonies such as Kenya, Malaya, and Cyprus, but by record-high newspaper circulation, the advent of television, the conscription of ordinary men as soldiers, and fresh memories of the Second World War as a “good war.” Against this backdrop, was it really possible that British forces could torture suspects, carry out summary executions, and commit other atrocities in the colonies without people at home taking notice?

I am not the first historian to argue that the violence of decolonization was more open than secret. But this is usually asserted rather than demonstrated, leaving open the question of how contemporaries came to know about violence and what those ways of knowing meant for action—or the absence of action—to stop it. Rather than seeing the Hanslope Park scandal as confirmation that the state exercised a tight grip on information from the colonies, I took it as an invitation to look beyond the self-serving records of the imperial bureaucracy altogether. As it turns out, one of the clearest signs of widespread knowledge about colonial violence is the sheer range of institutions and individuals whose archives still contain traces of it.

“One of the clearest signs of widespread knowledge about colonial violence is the sheer range of institutions and individuals whose archives still contain traces of it.”

Letters from soldiers in the field to relatives and friends in Britain acknowledged brutality in a few different registers: sometimes matter-of-fact, sometimes ashamed and disgusted, sometimes vengeful and excited. Missionaries and aid workers came face-to-face with violence in the detention camps where they did their jobs, then drew correspondents at home into discussions about the atrocities they witnessed and the dangers of complicity. Debates unfolded, too, between journalists and editors who questioned whether common knowledge in the colonies met professional standards for publication or broadcast. From the British Army and the Church of England to the British Red Cross and the BBC, the confrontation with extreme violence moved in parallel through bureaucratic chains of command.

Private confidences and public statements reinforced each other rather than defining radically different domains of knowledge. Fantasies of racial violence were pronounced in the memoirs and novels about colonial war that rolled off presses in the 1950s, many of them written by veterans, giving rise to a surprisingly explicit genre I call “counterinsurgency pulp.” Though muted and hedged in significant ways, reporting on colonial war in newspapers, newsreels, radio, and television delivered a steady drumbeat of disclosures and occasionally shocking revelations. Even stage plays and television dramas meditated on the grim fatalism of crossing moral boundaries for the sake of an empire that seemed to be slipping away.

To show that colonial violence was experienced as British violence, moving beyond state archives proved vital, not only because governments selectively disclose information but because an unsettling sense of involvement in brutality reached across classes and cultures. It became part of everyday life. And it was no secret.

April 22, 2023

“Think like a forest”: how forest literature can help us fight climate change

“Think like a forest”: how forest literature can help us fight climate change

Literary texts are clearly not the most potent weapons in the fight against climate change. Manufacturers of wind turbines are more important protagonists in that struggle, as are protest groups campaigning to leave coal and oil in the ground. But while this gargantuan task needs practical know-how and political militancy, it also requires a clear sense of its wider goals.

Full decarbonisation in the next 10 years will demand massive state-led investment in renewable energy and therefore a head-on confrontation with the overweening power of big banks and their political allies. It will necessitate the drastic restriction of commercial air travel. The subordination of virtually all other social and political priorities to the existential task of preventing the catastrophic, cascading effects of global heating may also require gigantic state-led investment in the atmospheric capture of CO2. The late EO Wilson, author of Half-Earth, urged the rewilding of vast areas of the Earth’s surface so that “carbon sinks,” principally fens, bogs, swamps and forests, might absorb anthropogenic (human-caused) greenhouse gas emissions.

Around 15% of emissions are caused by the cutting and burning of forests, primarily for the purpose of clearing land for plantations and animal grazing (which is itself a major source of methane and nitrous oxide emissions). The fight to forestall or at least mitigate global heating will therefore require states, in the tropics and elsewhere, to police a ban on deforestation. The task that faces humanity is frankly mind-boggling in its scope and radicalism. How we do it is a practical and political question for activists and movements, as well as engineers, economists, agronomists, pioneers of new technologies and so on. Why we should embark on what would truly be, as David Wallace-Wells suggests in The Uninhabitable Earth, “the greatest story ever told” is in part a cultural question.

Apocalyptic warnings of drowned cities and biblical exoduses, record droughts and deadly heatwaves, roiling storms and crozzled forests, might just as easily embolden rising nationalist and fascist movements that wish to respond to the crisis by erecting border walls. I am convinced that the fight against climate change requires images of an emancipated, egalitarian, and sustainable future for human societies. My current research on world literature and the climate crisis, including my article “Conjectures on Forest Literature” in Forum for Modern Language Studies, aims to show how literary texts cultivate images of a desirable future after the climate crisis.

“Literature is a vital resource in the era of climate emergency because it explores rival ways of inhabiting the living world.”

Literature is a vital resource in the era of climate emergency because it explores rival ways of inhabiting the living world. There are multiple ways of seeing a forest, for example. From the point of view of a logging company it is a stand of valuable timber. To a Brazilian cattle rancher, the Amazon is a useless wasteland to be cleared and made productive and profitable. To the seventeenth-century white settler in New England or what is now Canada’s Atlantic provinces, the forest was a sinful wilderness as well as a feminised space that ought to be domesticated and disciplined.

By virtue of their superior scientific and imaginative understanding of that same forest, the Mi’kmaq, the First Nations people of that region, have viewed it as a densely interconnected web of selves, according to Annie Proulx’s Barkskins (2016). In this extensive historical novel about deforestation in North America since the seventeenth century, the forest emerges as a battleground between rival ways of seeing the living world. For Thomas Hardy’s The Woodlanders (1887), the wood in Little Hintock, a secluded dale in deepest Wessex, is a kind of holdover of “natural” social and ecological relations. There Hardy’s woodlanders preserve their age-old customs and their dependency on the wood’s bounty while chafing at the restrictions of property, money, and marriage. In the American speculative fiction writer Ursula Le Guin’s The Word for World is Forest (1972), the exceptionally perceptive and cooperative Athsheans on the distant forested world of New Tahiti wage a successful revolutionary struggle against grasping imperialists from a treeless Plant Earth. An allegory for the Vietnam War, this classic short novel also promotes the forest as a resonant image of our essential connectedness with the rest of nature.

Such texts teach us to “think like a forest,” in the words of the anthropologist Eduardo Kohn, to esteem what the narrator of Proulx’s Barkskins calls “the wildness of the world,” “the vast invisible web of filaments that connected human life to animals, trees to flesh and bones to grass.” A “barkskin” is a logger, so called because the axemen rapidly become covered in hardened sap. Humans resemble trees, the novel tells us, and are not separable from or independent of nature. Similarly, trees resemble humans, since they communicate with and sustain each other through invisible networks of thread-like fungi in their roots, a discovery related by the Canadian scientist and conservationist Suzanne Simard in Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest (2021).

Novels, poems, plays, legends, and fairy tales about woods and forests (what I call “forest literature”) sometimes tell stories about the destruction of forests. They also engender emotional and intellectual attachments to the forest. They evoke grief and anger at felled or incinerated trees and exterminated peoples, cultures, and animals. They re-enchant the forest, not just describing but in their very forms, structures, and styles by purposefully evoking the mystery, complexity, intricacy, and magnitude of the forest. Forests, including representations of forests, are sites in which humans might learn to appreciate their essential connections with the rest of nature.

“Representations of forests provide us with exhilarating glimpses of a world outside a system of profit and plunder.”

There they might espy a distinctive and well-nigh revolutionary form of value. A tree is in one sense just a commodity or rather a primary commodity, the saleable material from which other commodities are made. It has exchange value and use value. But sequoia and oak trees, like Hardy’s woodlanders and the terrorised indigenous peoples of the Amazon certainly cannot be reduced to this impoverished definition of value. They are in truth what the Hungarian philosopher Karl Polanyi once called “fictious commodities”: they were not produced for sale.

Representations of forests provide us with exhilarating glimpses of a world outside a system of profit and plunder, of production for exchange rather than human and ecological need. Earth Day on 22 April, urges us to act, innovate, and implement a green revolution—boldly, broadly, and equitably. There is a cultural imaginary of oil, as the cultural theorist Imre Szeman has argued; oil and especially petroleum give rise to destructive fantasies of weightless freedom from social and natural constraints. Forest literature, by contrast, sketches the cultural imaginary of renewable energy and of sustainable forms of industrial and agricultural production; it points us in the direction of a coming world that is greener, wilder, more equal, and more just.

Featured image via Pixabay (public domain)

April 20, 2023

Populism and the future of democracy

Populism and the future of democracy

The democratic world is struggling to find political leadership. On the conservative side of the spectrum, the parties of the center-right have watched their constituencies fade and their political role be supplanted by a populist upsurge. The German Christian Democrats, the dominant party of the postwar period, now poll below 30% in national elections. The French Gaullists claim only 5% of registered voters and were eliminated in the first round of the 2022 presidential election. The Italian Christian Democrats got muscled off the political stage by insurgent populists, who in turn forced the resignation of the centrist prime minister, Mario Draghi. In lamenting the end of the era of postwar alliances, Draghi proclaimed, “the majority of national unity that has sustained this government from its creation doesn’t exist anymore.”

On the left of the spectrum, the picture is no rosier. The French Socialist presidential candidate got only 1.75% of the vote in the 2022 election and was unceremoniously eliminated. The dominant political parties of the postwar period—on both the right and left—have lost their mass base and their ability to project a common mission. The fact that the once-dominant French Gaullists and Socialists got less than 10% of the last presidential vote combined signals that the postwar politics of stable political competition is over.

“The dominant political parties of the postwar period—on both the right and left—have lost their mass base and their ability to project a common mission.”

In place of the parties of yesteryear, lone wolves quickly ascend through independent channels and the parties cannot resist the power of social media fueled candidates. Once in office, the restraints are gone. No one today sees faithful service as a back bencher or a junior committee member as a path to personal advancement. More critically, few fear challenging party leadership as a meaningful roadblock to personal or policy success. Repeatedly, the parties of the center-right and center-left have watched their constituencies fade and their political role be supplanted by a populist upsurge.

At home in the United States, the party publicly evidencing current disarray is the Republicans. But a quick look around the world’s democracies makes clear that is not just the Republicans who are displaying inability to project clear leadership. The evident tumult at the heart of the Republican Party may appear as a momentary loss of direction in the incomplete transition away from President Trump. Barely able to select a Speaker, House Republicans are now unable to form a set of legislative proposals showcasing their claims to manage the deficit, immigration, or a host of real governance concerns. In 2020, in thrall to the prospect of Trump’s re-election, the Republicans abandoned the American tradition of debate and horse-trading over a party platform, but promised, in the words of Mitch McConnell, that “the party only needs to reveal its plans for running Congress ‘when we take it back.’” But in 2023, even without a Trump-centered axis, the party now cannot present a coherent public platform despite having a House majority.

But beyond the Beltway dramas, one sees reflections of American political disrepair across the core of democracies. In the United Kingdom—where, like the US, the first-past-the-post electoral system entrenches the existing parties—both Labour and the Tories have proven repeatedly unable to put forward cohesive policy frameworks. In the proportional representation systems of France, Germany, and Italy, meanwhile, politics fracture further, citizens’ interests fail to be integrated in a common enterprise, and democracies recede.

“The atrophying of the center-right is destabilizing all western democracies because they are ceding valuable political turf to populism.”

The atrophying of the center-right is destabilizing all western democracies because they are ceding valuable political turf to populism.These parties shared a core vision and overlapping constituencies with the Republican Party, and it yielded a political path that offered fairly steady electoral success in the second half of the twentieth century. All these parties had ties to the commanding heights of the economy, but with wide and deep roots among small entrepreneurs and farmers. They were institutionally linked to the mainstream churches and local chambers of commerce. Conservative in their social values, they nonetheless coexisted for the most part with the individual rights demands of the post-1968 era. When in government, these parties were fiscally cautious, yet had made their peace with the core New Deal and social democratic safety nets, including national health in Europe and social security and Medicare in the US.

Broad constituencies yielded conflicting policy demands. Electoral success required an ability to mediate and re-election turned on successful stewardship once in office. That in turn required both internal party discipline and the capacity to control the delivery of political goods through the legislative process. Despite internal tensions, these parties all stood for something and could translate electoral success into tangible outcomes.

Across the democratic world, almost without exception, the legislative chamber has now largely collapsed into dysfunction reflecting the failure of political party leadership. The dominant political parties of the postwar period —on both the right and left—have lost their mass base and their ability to project a common mission. The parties of the left relied on a trade union tradition that has largely evaporated in the private sector. Correspondingly, the parties on the right saw the disappearance of the social ties that forged their base of support. It is hard to even imagine that in post-WWII America, about 40% of the adult male population belonged to a fraternal order such as the Masons or Rotaries or Kiwanis—relics of a form of local engagement which has almost disappeared from contemporary life.

As the historic parties become unmoored from their institutional bases, the consequences of their weakened internal discipline compound. These parties lose control over their nominees and become less participatory and more susceptible to capture by narrow, minority, or extreme interests within the party. What these parties stand for is increasingly unclear. The resulting loss of political coherence finds its substitute in inconsistent, personalist, or substance-less platforms, as with the Republicans in 2020. And with less capacity to organize members, parties provide less of the coordination benefits that made legislatures productive, deepening democracies’ under-delivery and capacity problems. Around the world, from the US to Eastern Europe, left and right, the caudillo politics these weakening constraints have allowed are undermining popular sovereignty.

“Demographic changes and cultural estrangement fracture citizens’ relationships with their polities, weaknesses that populists gleefully exploit.”

Party weakness highlights the perceived inability of democracies to meet citizens’ economic expectations. Meanwhile demographic changes and cultural estrangement fracture citizens’ relationships with their polities, weaknesses that populists gleefully exploit. When it comes to railing against threats from outside, established parties hold no natural advantage over charismatic demagogues.

No doubt President Biden was exploiting the moment of the State of the Union in February to demand what is the Republican program on deficits, social spending, and immigration. Very well. We live in a world of partisan competition. But how long can a party claiming the inherited mantle of years of governance avoid taking positions on critical issues of the day? The Tories thought they could avoid taking a stance on Brexit and instead substitute attacks on the uninspired leadership of Labour. That strategy brought years of weakness and even a scathing comparison to the shelf life of a head of lettuce.

The Democrats in 2020 were able to command from the center around President Biden’s candidacy and have been able to govern more-or-less on that basis. Whatever one’s party affiliation, the reality is that a healthy democracy requires partisan competition that presents voters a choice on policy outcomes. Parties that cease to reflect their constituencies and to organize themselves around a vision of governance do not satisfy the demands of democracy. Slowing the rise of populism and protecting popular sovereignty is a tall endeavor, and no simple platform of reform can do it alone. But reinvigorating parties, re-empowering electoral majorities, and restoring the capacity of parties and their candidates to govern must play a part.

Featured image by Jilbert Ebrahimi on Unsplash (public domain)

COVID-19 and consumerism: what have we learnt?

COVID-19 and consumerism: what have we learnt?

Writers often worry that someone will scoop them before they finish, or an unexpected event will undo years of research and writing. Two weeks after naturalist Rachel Carson published her first book, Under the Sea Wind, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. Despite excellent reviews, the book sold fewer than a thousand copies. The COVID-19 pandemic became my Pearl Harbor. As The All-Consuming Nation went to press, COVID complicated almost every aspect of the book’s publication. Supply-chain disruptions delayed its arrival from the printers in India. Book talks, interviews, and other marketing tools were no longer possible.

Yet, the COVID crisis did have one benefit. It highlighted the book’s central themes about the vital role consumerism plays in sustaining our national economy and the environmental costs it imposes. Since World War II, government policy promoted mass consumption to maintain high employment. The consumer sector grew to account for about 70% of GDP. Mass consumerism also became an instrument of foreign policy.

Governments have lost legitimacy when they fail to fulfill the material wants of their people. The collapse of the Soviet Union illustrates the point. Ronald Reagan’s massive defense build-up created anxiety in the Kremlin, but it was the failure to produce both guns and butter that doomed the Soviet empire. In the 1980s, the USSR was saddled with a second-world economy that provided a decent living for only an elite minority.

“Of all the “isms” seeking to capture hearts and minds around the globe… consumerism was the winner.”

Many industries that created materials for consumption spewed pollutants and toxic wastes. Farm runoffs created dead zones in coastal waters. New suburban communities destroyed once tranquil rural landscapes, while failing septic systems swamped lawns with sewage. The automobiles that connected suburbanites with urban jobs added to layers of smog. Junkyards of discarded vehicles blighted roadsides. And when manufacturers closed factories and sent jobs overseas, whole communities felt the pain.

In the late 1960s, the combination of spending for the Vietnam War and LBJ’s Great Society triggered an inflation that ate away at disposable income. Cynics described the economy of the early 1970s as “Nixonomics” in which what should go up such as income and employment went down, while prices and unemployment went up. The tech boom that began in the late 1970s created a cornucopia of new devices, including the personal computer, portable music players, cell phones, and wide-screen televisions. It made possible the development of the Internet, Worldwide Web, and Etailing as a new avenue for consumption. Shortly after the “Dot.com bubble” burst in 2002, destroying considerable wealth and consumer confidence, investors found a new way raise money. They bundled home mortgages and other debt instruments into securities they peddled to anyone seeking high rates of return. Contraction of the housing market in 2008 sent the economy into a tailspin from which it took years to recover.

“Yet, the dark clouds of the COVID era did have a thin silver lining. COVID temporarily eased the climate crisis that mass consumption spawned.”

The outbreak of COVID in 2020 proved even more disruptive. Over previous decades, American businesses established global supply chains to keep costs low and profits high. As a result, the United States no longer produced goods such as surgical masks that Americans and other nations needed to fight the epidemic. Shortages of vital parts manufactured overseas such as silicon chips shutdown assembly lines at home. Shoppers found stores shelves increasingly bare. Even pet food was hard to find, new cars were scarce, and used-car prices soared. Once the COVID death toll abated and unemployment started to fall, inflation posed a new headache for consumers and for politicians. The rising price of goods and services added one more issue to gridlock in Washington. Conservatives opposed the massive expenditures incurred to fight the pandemic and keep the economy functioning.

During the pandemic, consumers increasingly based their political choices on their cultural values. In the 2020 election, those districts with Cracker Barrel restaurants voted for Donald Trump; those with Whole Foods markets went for Joe Biden. Factions, angry at pandemic restrictions and loyal to Covid-denier Trump, expressed their outrage at companies that respected “politically correct” values.

With travel for work, shopping, or pleasure at a virtual standstill, jet vapor trails disappeared from the skies. Tailpipe emissions also lessened as commuters worked from home, shopped on-line, and used Zoom to gather without burning fossil fuel. In that way, COVID offered “the all-consuming nation” lessons about how to create an economy with a lighter footprint on the earth.

Feature image: Big market in Ubud, Indonesia by Bernard Hermant. Public domain via Unsplash.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers