Oxford University Press's Blog, page 49

June 19, 2023

Public health challenge: taking on the commercial determinants of health

Public health challenge: taking on the commercial determinants of health

Next year the World Health Organization is expected to release its first Global Report on the Commercial Determinants of Health. In April this year, Lancet published a series of papers on the commercial determinants of health (CDoH), the most comprehensive assessment to date on this emerging field of public health scholarship. Defined by the WHO as “private sector activities that affect people’s health,” the Lancet reports describe commercial determinants as the “systems, practices, and pathways through which commercial actors drive health and equity.” A CDoH framework has the potential to inform powerful new approaches to reducing the world’s most serious public health problems. For public health professionals, scholars, and activists, the growing interest in CDoH provides a forum for re-thinking how to improve public health by changing established policies on regulation, marketing, conflicts of interest, lobbying, and other business practices.

How commercial actors threaten planetary and human healthIncreasing evidence shows that the activities of commercial actors shape the adverse health and environmental consequences of climate change, the growing global burden of diet-related and other chronic diseases, firearms deaths and injuries, the failure of governments to respond adequately to infectious disease outbreaks, and inadequate access to health care for low income populations. Commercial actors include transnational corporations, small and medium sized businesses, trade associations, financial institutions, advertising, legal and public relations firms, as well as industry-funded Corporate Social Responsibility organizations, such as charities. Through business practices that are focused only on profit generation, these organizations promote, defend, and market unhealthy products, push people into debt, pollute the environment, and endanger their workers. Through political practices such as lobbying, campaign contributions, and “capture” of government agencies, they mislead policymakers and undermine, dilute, or delay policies designed to protect public health.

“A CDoH framework has the potential to inform powerful new approaches to reducing the world’s most serious public health problems.”

Over the last 100 years or so, businesses have also made positive contributions to improving health but increasingly in the last 50 years, changes in the world’s political economy including globalization, financialization, and market concentration have amplified the negative consequences and moderated the positive ones.

How can the public health community use the CDoH lens to better protect human and planetary health and reduce the stark health inequities that characterize the world today? We suggest four cross-cutting strategies.

1. Restoring the public sectorFirst, public health professionals can contribute to restoring the role of the public sector in defending health. As the wealth and power of the market economy has grown, the role of government in regulating business activities, providing quality public services, and shaping belief systems has diminished. Using their communications and message framing skills, health professionals can challenge commercial actors that mislead the public, counteract ideas that emphasize individual rather than collective responsibility for health, and defend regulations that protect public health against attacks from private interests.

2. Identifying the pathways that harm healthTo inform action to reduce commercial harms, researchers need to identify the specific pathways by which business practices lead to poor health outcomes. An impressive body of evidence documents how tobacco, alcohol, unhealthy food, gambling, fossil fuel, firearms, and other industries have harmed health, but more work is needed to identify emerging twenty-first-century threats. How do employers of precarious workers, payday and mortgage lenders, private equity firms that invest in nursing homes, or Big Tech companies that market to children shape patterns of health and disease? By elucidating the pathogenic routes of harm, investigators can suggest policies and regulatory approaches to prevent these adverse outcomes.

3. Using practice-based evidence to inform strategiesWhile some are pessimistic about overcoming the power of business to shape the rules, around the world thousands of organizations are campaigning—and sometimes winning— battles to create healthier communities, challenge corporate pollution, provide healthier and more affordable food, make essential medicines more accessible, and find other ways to create healthier communities and worlds.

By analyzing these experiences and identifying what works and what does not—creating a body of practice-based evidence to reduce harmful commercial influences—researchers can speed the scaling up of best and promising practices.

4. Joining the fight for democracyFinally, the public health community can join the fight for democracy, promoting the societal benefits of fair taxation and protecting voting and other democratic rights, key foundations for healthier and more just societies. Providing a health rationale for reversing the growing voice of corporations in deciding voting, tax, climate, health care, and other policies creates a more level playing field where ordinary citizens can reclaim their rights to a livable world.

As we write in the Lancet series, in our view, the most basic public health question is not whether the world has the resources or will to take action but whether humanity can survive if society fails to make this effort.

June 16, 2023

“There is no writer can touch sir Walter Scott”: Joyce and the Wizard of the North

“There is no writer can touch sir Walter Scott”: Joyce and the Wizard of the North

While Walter Scott was one of the greatest novelists of nineteenth-century literature, at least in terms of sales, James Joyce was probably the major novelist of the twentieth century in terms of impact and influence. According to Joyce’s brother Stanislaus, the Irish writer “couldn’t stand” the Scot’s work. Be that as it may, Joyce kept a copy of The Bride of Lammermoor in his Trieste library and, in 1924, Joyce memorised 500 lines of The Lady of the Lake while recovering after one of his many eye operations. There are also important similarities between Scott and Joyce as thinkers— both were fascinated by the histories of their respective nations, in the relationship between their home country and English power, and in the historical development of societies.

Scott is associated with forms of onanistic self-obsession and incest in Joyce’s texts. In “An Encounter”, a “queer old josser” asks a group of young boys if they have read any of Scott’s works. It is then heavily implied that the man goes off to masturbate. In A Portrait, a “dwarfish”, and “monkeyish” figure with a “shrunken brown hand” called “the captain” (an acquaintance of Stephen Dedalus), says he is reading The Bride of Lammermoor and announces that Scott “writes something lovely.” The captain adds that “There is no writer can touch sir Walter Scott.” Here Scott’s work is associated with a rather uncanny, degenerate character whose family possibly has a history of inbreeding: “was the thin blood that flowed in his shrunken frame noble and come of an incestuous love?”

According to Scott Klein, “the captain acts […] as a figure for Stephen’s national and sexual fears, a potentially apocalyptic image of the end of Ireland through inbreeding and Romantic absorption in its own past.” However, it is noteworthy that the captain is fascinated with the work of Scott, who worked primarily on Scottish history, rather than an Irish novelist with an Irish focus (although Scott’s national tales were heavily influenced by the Irish novels of Maria Edgeworth and Sydney Owenson). In other words, the captain is not directly absorbed in Ireland’s past. However, since Joyce viewed Scotland as Ireland’s “Poor sister” and part of the “Celtic family”, the captain is attracted to representations of the past of a “close relation” of Ireland’s. Furthermore, since Joyce saw attraction to family members as a veiled mode of self-obsession, the captain’s attachment to Scott and Scottish historical fiction can be read as a warped, indirect form of Romantic obsession with Ireland and Ireland’s past. The attention paid to the hands of the captain in A Portrait and the suggestive use of the word “touch” add vaguely onanistic connotations to the passage mentioned above.

In Dubliners and A Portrait, Scott is associated with sterility and decline rather than with the possibility of progress, despite societal advancement being a key theme in Scott’s work. Scott’s “stadial” view of history, influenced by Scottish Enlightenment figures such as Adam Smith, involves societies advancing and developing through set stages towards fixed states and is reflected in novels such as Waverley. This thinking is rejected in Joyce’s work in favour of a cyclical vision of history influenced by the Neapolitan philosopher Giambattista Vico. Scott’s Smithian “barbarism to refinement” sequence of development is reflected in the postscript to Waverley, when Scott considers the transformation of post-Culloden Scotland:

the change, though steadily and rapidly progressive, has, nevertheless, been gradual; and, like those who drift down the stream of a deep and smooth river, we are not aware of the progress we have made until we fix our eye on the nowdistant point from which we set out.

The obvious comparison to this image in a Joycean context is, of course, Joyce’s use of flowing rivers as a symbol of history and the passage of time in Finnegans Wake. On the face of it, Scott and Joyce have similar ways of thinking about history. However, Scott’s river image conceives of society moving towards completion and stasis while Joyce’s river of history in Finnegans Wake is linked to the sea and rain and is, therefore, associated with continuity and recurrence. This model of history is mimicked by the circular structure of Finnegans Wake, a text that that nullifies teleology and resists its own closure or completion. For Scott, progress is largely about the “gradual influx of wealth” and the “extension of commerce”, as mentioned at the conclusion of Waverley. To paraphrase Garrett Deasy, Stephen’s boss in Ulysses, all human history in Scott moves towards one great goal: the manifestation of capitalist modernity.

Scott’s work is informed by what Catherine Jones has called a “poetics of distance,” the exploration of how present society came into being, and an emphasis on the differences between “then” and “now.” In contrast, Joyce’s work is structured by what might be termed a poetics of parallel, where the present echoes the historical or mythic past. His use of the Odyssey as a scaffold for Ulysses is perhaps the best-known example of this feature of his work.

Featured image: Čeština: Adolf Hoffmeister, James Joyce, 1966 (CC BY-SA 4.0)

June 14, 2023

The company we keep, part two: bud(dy)

The company we keep, part two: bud(dy)

I am picking up where I left off two weeks ago. Since there have been no comments or letters connected with part one, I will, as promised, tackle the convoluted history of bud. The Internet is awash in suggestions about the origin of this universally known word. Some such suggestions are reasonable, even clever; others fanciful (for instance, bud has been derived by some from Pashto, from Spanish, and even from the names Buddha and Budweiser!). Of course, we now have the opinion of the OED online, and yet I may add something to the ongoing discussion—no revolutionary hypothesis: rather a glance at the state of the art. Predictably, bud ~ buddy can also be found in the first volume of the original OED, but its editor James A. H. Murray was reticent on the word’s etymology. Today’s editors have much more to say about the history of bud; yet the sought-for origin remains disputable and will probably remain such.

Though the first volume of the OED appeared in 1896, people kept returning to the history of bud, and some of their hypotheses deserve attention. Perhaps the most important part of the tale is whether bud ~ buddy has anything to do with the word butty “comrade.” Here are some quotations from the letters sent to the biweekly Notes and Queries (my constant and inexhaustible source of inspiration). “What is the origin of the word butty, gamekeeper’s slang for “comrade”? The dog was took away home to granny by my butty” (Richard Jefferies, ‘The Amateur Poacher,’ 1896, p. 117”). The editor answered:

“The origin is unknown. The ‘H.E.D.’ [that is, Historical English Dictionary, the original name of the OED; even Murray could not remember when HED became OED!] says that it is a possible corruption of booty. The word is in general use in England. See ‘English Dialect Dictionary’ [by Joseph Wright].”

The beginning of the HED/OED

The beginning of the HED/OEDOther contributors also cited butty from the regions where they lived, and Walter W. Skeat, ever-ready with a suggestion when it came to etymology, wrote:

I would suggest that butty, comrade, is a mere abbreviation of booty-fellow, one who shares in booty; hence a comrade. The full form occurs in Palsgrave [an early sixteenth-century lexicographer] and is duly explained in the “H.E.D.”, s. v. [sub voce “under the word”] “Booty,” §5.

Since that time the derivation of butty from booty-fellow has been repeated more than once. Other contributors to Notes and Queries mentioned butty collier “a man who contracts with the proprietor of a coalpit to get and raise coal to the bank at so much per ton.” In that context, butty was also connected with boot. Additionally, “in ironworks, where two men frequently manage a forge, one superintendent by day and the other by night, each often describes the other as his butty.” In the same region, “a man and a woman living together irregularly sometimes describe each other as his or her butty, and other people would so describe their relations” (1901). “In Warwickshire [the West Midlands] sweethearts who keep company describe their association as buttying with each other.” Bud “husband” has been used for centuries, but of course no phonetic legerdemain can produce this wordfrom husband. Finally, in Scotland, buddy, buddie, and butty have been long since used as a pet designation for a little child.

In some regions, this activity is called buttying.

In some regions, this activity is called buttying.(Via Pexels, public domain)

Judging by the meaning of the words mentioned above, it seems that buddy and butty have rather little to do with booty, a French word of Germanic origin. Booty-fellow is close but seems to have little to do with buddy as we know it. Below, I will quote part of a letter from the journal American Speech 4, 1929, p. 389. Though the author’s suggestion looks like an example of folk etymology, bud is such a controversial word that even dubious remarks have some value.

The Standard Dictionary [that is, Funk and Wagnalls] gives butty as a variant of buddy. I raise the query whether precedence should not be the other way. When I was a boy in the Pennsylvania coalfields, one of the commonest words in the miners’ speech [again mining, as in England!] was butty, or buttie, as I have always preferred to spell it, meaning work-fellow. In the cramped, underground and honey-combs where bituminous coal is dug, the man with a pick and the man with the shovel are literally butties, working all day long buttock to buttock, or in the vulgar but comradely abbreviation, butt to butt. The word was used generally in a technical sense, without any endearing connotation of spiritual nearness. But the boys of the community thirty years ago adopted the word for the idea which later at school they were to express by chum, a word which I confess always sounds emasculated and utterly lacking the vulgar warmth of buttie (!).

The author begins his letter by saying that buddy “is by origin a childish corruption of brother, with a familiar form ‘bud.’ … it is incontrovertible that bud and buddy are diminutives of brother…”.

The “emasculated” chum was discussed briefly and inconclusively in the previous blog post, and I will not comment on the author’s use of the word incontrovertible. I have more than once expressed my objections to terms like certainly, undoubtedly, obviously, and so forth. (Very few things in etymology are incontrovertible.) I am only a bit confused about the order of events. If buddy is from brother, how can it a variant of butty? Here, I’ll also mention the enigmatic sixteenth-century adjective baddy of unclear meaning, but, apparently, with some negative connotations. This word deserves attention, because Murray devoted a long letter to “the queer phrase” paddy persons in Notes and Queries 9/XII, 1903, 87-88, and nothing that great man wrote should fall through the cracks. It turned out that paddy persons is a misreading: the correct 1585 phrase is baddy persons, and I wondered whether baddy has anything to do with buddy. My question remains unanswered, but the syntax of the quotation is characteristic, and I would like to quote that phrase as a postscript to my blog post.

The mood of the stories are gloomy.

The mood of the stories are gloomy.(Via Pexels, public domain)

Here is this phrase: “I doubt [= fear] not that the flower of the pressed English bandes are gone, and that the remnant supplied with such baddy persons as commonly, in voluntary procurements, men are glad to accept.” Baddy will, unfortunately, remain a minor riddle, but another thing should not be overlooked: “The flower of such band(es) are gone.” The subject is of course flower, and the verb should have been is. Yet the writer made the verb agree with the noun closest to it (bands). As is well-known, colonial languages are conservative. American English is no exception. The Revised Version of the Bible has: “Our Father which art in heaven.” And I sometimes hear statements like: “That’s the guy which I told you about.” But this usage is relatively rare. By contrast, the syntax of the phrase quoted above is ineradicable: students’ papers teem with it. I have once quoted my favorite example from an undergraduate’s essay: “The mood of the tales are gloomy.” This usage, well-known to the historians of English syntax, is still rather common in Ireland and in other “colonial” varieties of English. It would be interesting to heart what our readers know about it.

Next week, I’ll finish my discussion of buddy and say what little I think I know about its origin. Nothing in my suggestion will be original or incontrovertible.

Featured image via Wikimedia Commons (public domain)

June 13, 2023

What can Large Language Models offer to linguists?

What can Large Language Models offer to linguists?

It is fair to say that the field of linguistics is hardly ever in the news. That is not the case for language itself and all things to do with language—from word of the year announcements to countless discussions about grammar peeves, correct spelling, or writing style. This has changed somewhat recently with the proliferation of Large Language Models (LLMs), and in particular since the release of OpenAI’s ChatGPT, the best-known language model. But does the recent, impressive performance of LLMs have any repercussions for the way in which linguists carry out their work? And what is a Language Model anyway?

At heart, all an LLM does is predict the next word given a string of words as a context —that is, it predicts the next, most likely word. This is of course not what a user experiences when dealing with language models such as ChatGPT. This is on account of the fact that ChatGPT is more properly described as a “dialogue management system”, an AI “assistant” or chatbot that translates a user’s questions (or “prompts”) into inputs that the underlying LLM can understand (the latest version of OpenAI’s LLM is a fine-tuned version of GPT-4).

“At heart, all an LLM does is predict the next word given a string of words as a context.”

An LLM, after all, is nothing more than a mathematical model in terms of a neural network with input layers, output layers, and many deep layers in between, plus a set of trained “parameters.” As the computer scientist Murray Shanahan has put it in a recent paper, when one asks a chatbot such as ChatGPT who was the first person to walk on the moon, what the LLM is fed is something along the lines of:

Given the statistical distribution of words in the vast public corpus of (English) text, what word is most likely to follow the sequence “The first person to walk on the Moon was”?

That is, given an input such as the first person to walk on the Moon was, the LLM returns the most likely word to follow this string. How have LLMs learned to do this? As mentioned, LLMs calculate the probability of the next word given a string of words, and it does so by representing these words as vectors of values from which to calculate the probability of each word, and where sentences can also be represented as vectors of values. Since 2017, most LLMs have been using “transformers,” which allow the models to carry out matrix calculations over these vectors, and the more transformers are employed, the more accurate the predictions are—GPT-3 has some 96 layers of such transformers.

The illusion that one is having a conversation with a rational agent, for it is an illusion, after all, is the result of embedding an LLM in a larger computer system that includes background “prefixes” to coax the system into producing behaviour that feels like a conversation (the prefixes include templates of what a conversation looks like). But what the LLM itself does is generate sequences of words that are statistically likely to follow from a specific prompt.

It is through the use of prompt prefixes that LLMs can be coaxed into “performing” various tasks beyond dialoguing, such as reasoning or, according to some linguists and cognitive scientists, learn the hierarchical structures of a language (this literature is ever increasing). But the model itself remains a sequence predictor, as it does not manipulate the typical structured representations of a language directly, and it has no understanding of what a word or a sentence means—and meaning is a crucial property of language.

An LLM seems to produce sentences and text like a human does—it seems to have mastered the rules of the grammar of English—but at the same time it produces sentences based on probabilities rather on the meanings and thoughts to express, which is how a human person produces language. So, what is language so that an LLM could learn it?

“An LLM seems to produce sentences like a human does but it produces them based on probabilities rather than on meaning.”

A typical characterisation of language is as a system of communication (or, for some linguists, as a system for having thoughts), and such a system would include a vocabulary (the words of a language) and a grammar. By a “grammar,” most linguists have in mind various components, at the very least syntax, semantics, and phonetics/phonology. In fact, a classic way to describe a language in linguistics is as a system that connects sound (or in terms of other ways to produce language, such as hand gestures or signs) and meaning, the connection between sound and meaning mediated by syntax. As such, every sentence of a language is the result of all these components—phonology, semantics, and syntax—aligning with each other appropriately, and I do not know of any linguistic theory for which this is not true, regardless of differences in focus or else.

What this means for the question of what LLMs can offer linguistics, and linguists, revolves around the issue of what exactly LLMs have learned to begin with. They haven’t, as a matter of fact, learned a natural language at all, for they know nothing about phonology or meaning; what they have learned is the statistical distribution of the words of the large texts they have been fed during training, and this is a rather different matter.

As has been the case in the past with other approaches in computational linguistics and natural language processing, LLMs will certainly flourish within these subdisciplines of linguistics, but the daily work of a regular linguist is not going to change much any time soon. Some linguists do study the properties of texts, but this is not the most common undertaking in linguistics. Having said that, how about the opposite question: does a run-of-the-mill linguist have much to offer to LLMs and chatbots at all?

Featured image: Google Deepmind via Unsplash (public domain)

June 12, 2023

Elon Musk, Mars, and bioethics: is sending astronauts into space ethical?

Elon Musk, Mars, and bioethics: is sending astronauts into space ethical?

The recent crash of the largest-ever space rocket, Starship, developed by Elon Musk’s SpaceX company, has certainly somewhat disrupted optimism about the human mission to Mars that is being prepared for the next few years. It is worth raising the issue of the safety of future participants in long-term space missions, especially missions to Mars, on the background of this disaster. And it is not just about safety from disasters like the one that happened to Musk. Protection from the negative effects of prolonged flight in zero gravity, protection from cosmic radiation, as well as guaranteeing sufficiently high crew productivity over the course of a multi-year mission also play an important role.

Fortunately, no one was killed in the aforementioned crash, as it was a test rocket alone without a crew. However, past disasters in which astronauts died, such as the Space Shuttle Challenger and Space Shuttle Columbia disasters, remind us that it is the seemingly very small details that determine life and death. So far, 15 astronauts and 4 cosmonauts have died in space flights. 11 more have died during testing and training on Earth. It is worth mentioning that space flights are peacekeeping missions, not military operations. They are carried out relatively infrequently and by a relatively small number of people.

It is also worth noting the upcoming longer and more complex human missions in the near future, such as the mission to Mars. The flight itself, which is expected to last several months, is quite a challenge, and disaster can happen both during takeoff on Earth, landing on Mars, and then on the way back to Earth. And then there are further risks that await astronauts in space.

The first is exposure to galactic cosmic radiation and solar energetic particles events, especially during interplanetary flight, when the crew is no longer protected by both Earth’s magnetic field and a possible shelter on Mars. Protection from cosmic radiation for travel to Mars is a major challenge, and 100% effective protective measures are still lacking. Another challenge remains being in long-term zero-gravity conditions during the flight, followed by altered gravity on Mars. Bone loss and muscle atrophy are the main, but not only, negative effects of being in these states. Finally, it is impossible to ignore the importance of psychological factors related to stress, isolation, being in an enclosed small space, distance from Earth.

A human mission to Mars, which could take about three years, brings with it a new type of danger not known from the previous history of human space exploration. In addition to the aforementioned amplified impact of factors already known—namely microgravity, cosmic radiation, and isolation—entirely new risk factors are emerging. One of them is the impossibility of evacuating astronauts in need back to Earth, which is possible in missions carried out at the International Space Station. It seems that even the best-equipped and trained crew may not be able to guarantee adequate assistance to an injured or ill astronaut, which could lead to her death—assuming that care on Earth would guarantee her survival and recovery. Another problem is the delay in communication, which will reach tens of minutes between Earth and Mars. This situation will affect the degree of autonomy of the crew, but also their responsibility. Wrong decisions, made under conditions of uncertainty, can have not only negative consequences for health and life, but also for the entire mission.

“It is worth raising the question of the ethicality of the decision to send humans into such a dangerous environment.”

Thus, we can see that a future human mission to Mars will be very dangerous, both as a result of factors already known but intensified, as well as new risk factors. It is worth raising the question of the ethicality of the decision to send humans into such a dangerous environment. The ethical assessment will depend both on the effectiveness of available countermeasures against harmful factors in space and also on the desirability and justification for the space missions themselves.

Military ethics and bioethics may provide some analogy here. In civilian ethics and bioethics, we do not accept a way of thinking and acting that would mandate the subordination of the welfare, rights, and health of the individual to the interests of the group. In military ethics, however, this way of thinking is accepted, formally in the name of the higher good. Thus, if the mission to Mars is a civilian mission, carried out on the basis of values inherent in civilian ethics and bioethics rather than military ethics, it may be difficult to justify exposing astronauts to serious risks of death, accident, and disease.

One alternative may be to significantly postpone the mission until breakthrough advances in space technology and medicine can eliminate or significantly reduce the aforementioned risk factors. Another alternative may be to try to improve astronauts through biomedical human enhancements. Just as in the army there are known methods of improving the performance of soldiers through pharmacological means, analogous methods could be applied to future participants in a mission to Mars. Perhaps more radical, and thus controversial, methods such as gene editing would be effective, assuming that gene editing of selected genes can enhance resistance to selected risk factors in space.

But the idea of genetically modifying astronauts, otherwise quite commonsensical, given also the cost of such a mission, as well as the fact that future astronauts sent to Mars would likely be considered representative of the great effort of all humanity, raises questions about the justification for such a mission. What do the organizers of a mission to Mars expect to achieve? Among the goals traditionally mentioned are the scientific merits of such a mission, followed by possible commercial applications for the future. Philosophers, as well as researchers of global and existential catastrophes, often discuss the concept of space refuge, in which the salvation of the human species in the event of a global catastrophe on Earth would be possible only by settling somewhere beyond Earth. However, it seems that the real goals in our non-ideal society will be political and military.

June 9, 2023

Rethinking the future of work: an interview with Eduardo Salas and Scott Tannenbaum

Rethinking the future of work: an interview with Eduardo Salas and Scott Tannenbaum

Introducing the authors of Teams That Work: Eduardo Salas and Scott Tannenbaum. Their work draws on a strong body of evidence to reveal what really drives team effectiveness in organizations. Eduardo Salas is the Allyn R. & Gladys M. Cline Professor and Chair of the Department of Psychological Sciences at Rice University, a prolific author, and active consultant. Scott Tannenbaum, as the President of the Group for Organizational Effectiveness, has advised hundreds of organizations globally, including more than 75 Fortune and Global 1000 companies across every major business sector.

Read an interview with the authors exploring aspects of teamwork and the future of work.

What are the building blocks for a successful team?We think the science is clear here. Teams that have some degree of task interdependence need a number of “key ingredients” in order to be effective. To begin, role clarity is a must. Then the team needs to have a compelling reason to be a team. That is, clear, valued goals and a purpose. The team leader matters—a leader who orchestrates the functioning of the team moment-to-moment by providing guidance, support, and caring for team members’ well-being and focus. They set the tone for the behavioral norms and how to resolve conflict and move ahead. This means the team members must perceive they have psychological safety to raise issues of concern. And finally, to mature, evolve, and be resilient—teams need a discipline of debriefing. Engaging in reflections of what transpired and how they can improve.

What is the difference between good and bad team communication?The funny thing about team communication is that there is a belief that “more is better.” But research shows that “better is better” and not more. In fact, from our experience the best teams are relatively quiet. That does not mean there is no communication going on, there is, but its timely and efficient. We think that what matters in teams is to hold robust information exchange protocols—protocols that allow for clear and accurate exchange of information and encourage team members to share unique information that others don’t possess.

How do we develop and support the next generation of leaders in a more remote world?“Organizations need to provide team and leader development and tools that mimic the new remote world.”

Yeah, the world of work has changed. Hybrid work might be the new normal. Although some organizations are going back to in-person too. In a “remote world” the teamwork issues are more challenging. More salient. Teams must pay more attention to the building blocks we noted as they are less likely to just “happen.” For example, it often takes longer to create psychological safety and mutual trust in a team when some teams members are remote, while others are collocated. So, organizations need to provide team and leader development and tools that mimic the new remote world. For team training, it can be helpful to use “simulations” as a means of building teamwork “muscles” that are relevant to the context they work in.

How does increased flexibility impact employees and organizations?Flexibility has two sides. Personally, most employees want flexibility, including having some degree of control over where and when they work. But employees also need to know where and how to communicate and coordinate with co-workers… and it is more difficult to maintain an awareness of who is available and who has the latest information when team members have a great deal of personal flexibility. To attract, retain, and engage employees, employers need to allow ample flexibility. And they then need to provide the tools, resources, and processes that enable them to coordinate effectively.

What do you think the world of work will look like in 10 years?“To attract, retain, and engage employees, employers need to allow ample flexibility and provide the tools that enable them to coordinate effectively.”

From the teamwork and collaboration angle—teams are here to stay, whether they are in person, remote, virtual or some hybrid form. More collaboration will be needed. People will be more connected, there will more networks that need to coordinate, communicate, and cooperate to succeed. We think a disproportionate share of breakthroughs, innovation, and knowledge generation will come from multi-disciplinary teams.

Visit the Rethink Work hub for more organizational psychology insights

Featured image: Canva

June 8, 2023

Inside the shark nursery: the evolution of live birth in cartilaginous fish

Inside the shark nursery: the evolution of live birth in cartilaginous fish

A new study in Genome Biology and Evolution reveals that egg yolk proteins may have been co-opted to provide maternal nutrition in live-bearing sharks and their relatives.While giving birth to live young is a trait that most people associate with mammals, this reproductive mode—also known as viviparity—has evolved over 150 separate times among vertebrates, including over 100 independent origins in reptiles, 13 in bony fishes, nine in cartilaginous fishes, eight in amphibians, and once in mammals. Hence, understanding the evolution of this reproductive mode requires the study of viviparity in multiple lineages.

Among cartilaginous fishes—a group including sharks, skates, and rays—up to 70% of species give birth to live young; however, viviparity in these animals remains poorly understood due to their elusiveness, low fecundity, and large and repetitive genomes. In a recent article published in Genome Biology and Evolution, a team of researchers led by Shigehiro Kuraku, previously Team Leader at the Laboratory for Phyloinformatics at RIKEN Center for Biosystems Dynamics Research in Japan, set out to address this gap. Their study identified egg yolk proteins that were lost in mammals after the switch to viviparity but retained in viviparous sharks and rays. Their results suggest that these proteins may have evolved a new role in providing nutrition to the developing embryo in cartilaginous fishes.

According to Kuraku, who now works as Professor of Molecular Life History Laboratory at the National Institute of Genetics in Mishima, investigators have long wanted to learn more about the evolution of viviparity in sharks and their relatives. “Reproduction is one of the most fascinating features of cartilaginous fishes because they show a broad spectrum of reproductive modes.” Among viviparous species, this includes a range of mechanisms for providing nutrients to the developing embryo, from relying solely on nutrients present in the embryo’s yolk sac, to feeding the embryo unfertilized eggs, secreting nutrients from the uterus (“uterine milk”), or transferring nutrients via a placenta.

To better understand these various mechanisms, the authors searched genomic and transcriptomic data from 12 cartilaginous fishes for homologs of vitellogenin (VTG), a major egg yolk protein synthesized in the female liver in egg-laying species. Regardless of their reproductive mode, all cartilaginous fish species had at least two copies of VTG, while all copies of VTG have been lost from mammals (although the authors did identify a copy in the Tasmanian devil, a marsupial, which was not previously known to harbor a VTG gene).

Next, the authors searched for homologs of the VTG receptor; while mammals retain a single copy of this receptor, Kuraku and his colleagues identified two ancient tandem duplications giving rise to three copies of the receptor in cartilaginous fishes. The authors note that this finding was unexpected. “We predicted the retention of egg yolk protein genes in the shark genomes because live-bearing sharks rely partly on nutrition supply from the egg yolk,” says Kuraku. “What surprised us the most was that cartilaginous fish including sharks have more copies of the egg yolk protein receptor genes.” This suggested that these proteins may provide a novel function in this viviparous lineage.

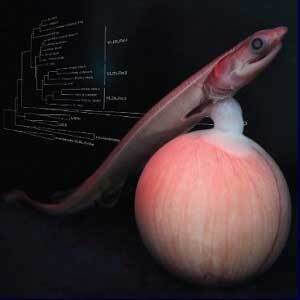

A developing embryo of the frilled shark, which has a unique mode of live-bearing and presumably exhibits a long gestation time of no less than three years. Photograph by Frilled Shark Research Project.

A developing embryo of the frilled shark, which has a unique mode of live-bearing and presumably exhibits a long gestation time of no less than three years. Photograph by Frilled Shark Research Project.To shed light on the functions of VTG and its receptor in these species, the authors compared tissue-by-tissue transcriptome data from one egg-laying shark (the cloudy catshark) and two viviparous sharks. The frilled shark is a viviparous species that provides no maternal nutrients to the developing embryo, while the spotless smooth-hound has a placenta. In the egg-laying cloudy catshark, VTG is primarily expressed in the liver, and its receptors are primarily expressed in the ovary. In contrast, in the two viviparous sharks, VTG was expressed not only in the liver but also in the uterus. Interestingly, the VTG receptor was also expressed in the uterus in these species. This suggests that VTG proteins may not only function as yolk nutrients but may also be transported into the uterus, where they may play a role in providing maternal-based nutrition in some cartilaginous fishes.

As noted by the authors, this intriguing possibility remains to be confirmed through functional studies. They also hope to expand this analysis to a genome-wide survey of factors associated with the various reproductive modes of cartilaginous fishes. Unfortunately, such experiments are difficult in these species given the challenge in obtaining biological samples. Kuraku and his collaborators, however, hope to change this. “This study was enabled by networking among individuals with various types of expertise who recognize the biological potential of cartilaginous fishes,” says Kuraku. “It also led to the launch and development of the Squalomix consortium,” an initiative launched in 2020 to promote genomic and molecular approaches specifically targeting shark and ray species. The consortium aims to make its resources publicly available, including a cell culture technique that may help enable functional assays of molecules, facilitating future research into the reproductive modes of these elusive and fascinating creatures.

Featured image is in the public domain

June 6, 2023

Societal roles for meat: what does science tell us?

Societal roles for meat: what does science tell us?

“Today’s food systems face an unprecedented double challenge. There is a call to increase the availability of livestock-derived foods (meat, dairy, eggs) to help satisfy the unmet nutritional needs of an estimated three billion people, for whom nutrient deficiencies contribute to stunting, wasting, anaemia, and other forms of malnutrition. At the same time, some methods and scale of animal production systems present challenges with regards to biodiversity, climate change and nutrient flows, as well as animal health and welfare within a broad One Health approach.”

Dublin Declaration

The debate about the use of animal-sourced food is not new.

Livestock and human nutritionHumans evolved as omnivores, and meat is a high-quality food source providing protein, fats, and a variety of nutrients, including those that are limiting factors in diets worldwide (Leroy et al, 2023). It’s broadly accepted that populations with limited access to meat have greater occurrences of health problems such as stunting. On the other hand, how much meat should be included in human diets has also been the topic of much research and discussion.

Based on international standards for evidence-based health recommendations, associations between red meat consumption and non-communicable diseases (such as metabolic diseases, obesity, and cardiovascular diseases) were of low to very-low certainty (Johnston et al., 2023). These limited risks depend on variation between individuals, as well as the preparation methods and degree of processing of the meat. Regular consumption of meat, dairy, and eggs as part of a well-balanced diet is advantageous.

Given the complex nutrient composition of meat, there are very limited options for replacement, and no simple 1-for-1 replacement. Individuals with sufficient resources are able to consume a well-balanced diet while restricting meat, dairy, and other animal food sources. However, individuals with fewer resources may not have access to alternatives but can ensure a balanced diet by including animal sourced foods. Reducing meat consumption globally could result in additional malnutrition, especially in already vulnerable populations such as children and pregnant women.

Livestock and the environmentPlant-based foods have been proposed as an alternative to meat. Plant-based food production generates large amounts of by-products that are inedible by humans (Thompson et al., 2023). Livestock consume by-products of human food production, simultaneously converting these back into the natural cycle and producing high-quality food products.

Well-managed livestock systems can improve environmental conditions by sequestering carbon, improving soil health, supporting biodiversity, and protecting watersheds. Simplified approaches to sustainability, such as reduction in livestock numbers globally, may actually increase environmental problems on a larger scale, especially as increases in plant-based food production require additional arable land.

Are there alternatives?Technologies based on cultured cells that aim to create a food product similar to meat have been under development for several decades (Wood et al, 2023). Should these technologies create a product with similar nutrient profiles, at less cost, and with lower environmental impact, they could provide nutrient-dense alternatives to meat. However, the technological issues with scaling production to a level where it is viable indicate that it may take considerable additional time to meet those goals.

To meet the demand of a growing population, it is critical that we increase efficiency of meat production, while building environmentally sustainable livestock food systems. It is critical to continue research, active conversations, and allowing science to do what science does best—asking questions.

Related articles

Related articlesJohnston, B., De Smet, S., Leroy, F., Mente, A., & Stanton, A. (2023). Non-communicable disease risk associated with red and processed meat consumption-magnitude, certainty, and contextuality of risk? Animal Frontiers 13(2). 28-34. https://doi.org/10.1093/af/vfac094

Leroy, F., Smith, N., Adesogan, A. T., Beal, T., Iannotti, L., Moughan, P. J., & Mann, N. The role of meat in the human diet: Evolutionary aspects and nutritional value. Animal Frontiers 13(2) 11-18. https://doi.org/10.1093/af/vfac093

Thompson, L., Rowntree, J., Windisch, W., Waters, S. M., Shalloo, L., & Manzano, P. (2023). Ecosystem management using livestock: Embracing diversity and respecting ecological principles. Animal Frontiers 13(2). https://doi.org/10.1093/af/vfac094

Wood, P., Thorrez, L., Hocquette, J.-F., Troy, D., & Gagaoua, M. (2023). “Cellular agriculture”: Current gaps between facts and claims regarding “cell-based meat.” Animal Frontiers 13(2) 68-74. https://doi.org/10.1093/af/vfac092

To read the entire Dublin Declaration, or to sign, visit the website. As of the publication date, there are over 900 signatures from across the globe.

Featured image via Pixabay (public domain)

June 5, 2023

Finding purpose for the corporate office

Finding purpose for the corporate office

Over two decades ago, a new type of fictional TV series debuted on the BBC that established a foothold between reality TV and sit-com. The Office brought the viewer into a familiar, yet mundane environment loaded with caricatures of people they ran into on a daily basis and thereby blurred the line between fiction and reality. The format was so effective at creating tension between characters that it verged on cringe-worthy, especially when Ricky Gervais was in the role of David Brent. Common character arcs played upon power dynamics between boss and employee, ill-advised office romance, and useless business procedures, creating a solid foundation for the 10 global incarnations of the show. Regarding the American version, we remember fondly the rivalry between Jim and Dwight, the incompetence of Michael as manager, and the growth of Pam from receptionist to sales associate. The characters got deeper and the call-backs grew stronger as the show navigated nine seasons and 201 episodes, an amazing run for any show, especially considering its humble back-drop of Dunder Mifflin, a fictional wholesale distributor of paper and office supplies.

The Office was not the first TV series to depict the workplace, but it was probably the most effective at capturing what many of us experienced on a routine basis, due to the show’s mockumentary style. Sitting in a conference room for sales training, calling HR to resolve a personal dispute, and participating in a community service day were instantly relatable. In March 2020, the pandemic drew to an end this version of the corporate office, as a new normal of work was ushered in based upon virtual collaboration technology. The depiction of Dunder Mifflin has become more akin to a time capsule of the corporate office’s heyday than an enduring depiction of the workplace. Three years later and employee expectations are firmly set on hybrid work, averaging between two or three days from home each week. Moreover, a majority of employees are prepared to quit their jobs if employers do not offer the flexibility they desire. When pressed about whether employees desire greater flexibility in either where or when they work, they place greater weight on work hours, yet both forms of flexibility have become table stakes when defining a desired employee experience for attracting and retaining talent.

“A majority of employees are prepared to quit their jobs if employers do not offer the flexibility they desire.”

It is ironic that Dunder Mifflin was a paper company, as the primary purpose of a corporate office was based in large part on the creation and retention of documents. Around the same time as the premiere of The Office, early signs of a dwindling sense of purpose for the physical corporate workplace began, as companies introduced the concept of “the paperless office.” E-mail replaced letters and document retention transferred to large computer servers. Such a move did not immediately eliminate the need for a physical office, as employees still required computers, phones, scanners, printers, and fax machines to do their jobs. Office life continued, with confidential documents circulating from desk to desk via a sealed manila envelope and assistants printing important documents just in case the computer crashed. Soon after, the provision of work laptops and Blackberry phones further chipped away at its purpose. Employees embraced the ability to work from anywhere, including the local coffee shop. Office space that was designed for a world based upon paper was out of step with modern day working, as evidenced by the empty bookshelves and file drawers of a traditional office. Despite a lack of purpose based upon paper or technology, employees still traveled to the office, if nothing more than out of habit.

When the pandemic occurred, a major shift to virtual work occurred out of necessity and those in corporate settings adapted magnificently to a new way of working. Any apprehensions that collaboration technology was not ready for wide scale adoption were quickly put to rest and with them, the last meaningful purpose for a physical office. If meetings, workshops, and trainings could all be done from anywhere, how much value was left for informal water-cooler types of conversations and do they in any way justify a full return to the office, now that most health concerns have abated? It is important to note that many jobs never shifted during the pandemic; for those working in manufacturing, healthcare, or similar industries, their jobs are inherently linked to a physical environment where virtual work may not be an easy or effective option. For jobs based upon paper, the story is different, with occupancy rates in downtown settings still trailing pre-pandemic levels and likely to stabilize to around 20% lower than before.

“With little of the original purpose for the corporate office left, it may be time for a reinvention of what the workplace should be.”

So where does this leave the corporate office and what are the long-term ramifications for hybrid and remote work? To keep the physical office relevant, employers are searching for the core reason why employees should bother to travel in. Should the office act as a connector, primarily to foster conversations and innovation, or should it be considered a magnet, pulling employees in for key events and professional development? Alternatively, should it transform into a hub fully embracing the blend between work and personal time, with onsite facilities like day care? Regardless of the model, the effects of hybrid and remote work on psychological well-being will be experienced for years to come. Beyond the fatigue already felt by employees from attending endless video conferences, as well as the intrusion of work into personal time, there are likely some very real consequences for interpersonal relationships. For example, helping behavior relies upon individuals knowing that they are on point to be helpful, which is confused by the anonymity offered by virtual work and leads to free-riding. Alternatively, with less opportunity for intimate interactions, repairing strained relationships will likely become harder. As a third example, corporate identity is less pronounced without the experience of walking into a physical office, which can lead to a more transactional mindset amongst employees and a lack of shared social norms about acceptable performance.

In many ways, the relevance of the physical corporate office has been under fire for decades, but the pandemic accelerated the shift and eliminated any remaining hesitations about the feasibility of hybrid and remote work. Without finding a new purpose, it is unlikely that the antics of The Office will be repeated in the same way or frequency as before. We might look back at the series in a different way, more of a time capsule than the mockumentary that it was intended to be. With little of the original purpose for the corporate office left, it may be time for a reinvention of what the workplace should be, one that embraces the new reality of work and blends our personal and professional lives to a much greater extent. Instead of the towering skyscrapers from the twentieth century, a visual representation of an apartment above a storefront might be a closer depiction to where we are heading. If that means one less character like David Brent, then the future of work might be alright after all.

June 4, 2023

What’s coming down the pike?

During the news coverage of the COVID pandemic, I enjoyed seeing Dr Anthony Fauci on television and hearing his old-school Brooklyn accent, still shining through in his late seventies in words like Pfizer, because, data, here, and that.

But my favorite expression to listen for was his use of “down the pike” to mean “in the future.” Fauci explained once that “you don’t see for days or weeks down the pike.” Another time he said “before you know it, two to three weeks down the pike, you’re in trouble.” Discussing vaccine testing he said “So we go into phase one, it’ll take about three months to determine if it’s safe. That’ll bring us three or four months down the pike.”

“Down the pike” is an expression I grew up hearing all the time in my home state of New Jersey. And, of course, many people say it besides Anthony Fauci. Joe Biden talks about how government and the private sector should “anticipate and respond to shortages that may be coming down the pike.” If you Google “down the pike” you’ll find it everywhere, even in New York Times headlines like “Is a Trans-Atlantic Pact Coming Down the Pike?” and (with an attempted pun) “Hydrogen Cars, Coming Down the Pike.” You can find occasional instances of things coming “up the pike,” and there is an early twentieth-century slang expression “hit the pike,” meaning “hit the road” or “leave.”

Not everyone is familiar with “down the pike.” Some mislearn it as the semantically plausible “down the pipe” rather than “down the pike.” It’s “down the pike,” but where does it come from?

I had assumed that “down the pike” had something to do with the New Jersey Turnpike, the 117-mile toll highway that runs from New York City to Delaware. The New Jersey Turnpike Authority was created in 1948 and the Turnpike itself was completed in 1951. It’s been collecting tolls ever since, along with the Garden State Parkway, which was completed in 1957.

There are lots of turnpikes, however, and the word goes way back. The Oxford English Dictionary gives examples from the early 1400s. It originally meant “a spiked barrier fixed in or across a road or passage,” and was used as a defense against attacks by men on horseback.

Later turnpike became extended to the sense of a turnstile to block horses. Samuel Johnson offered this definition: “Turnpike… a cross of two bars armed with pikes at the end, and turning on a pin, fixed to hinder horses from entering.” By the late 1600s, the turnpike was a toll booth of sorts, and a late seventeenth-century Act of Parliament refers to “collecting the said [toll]… by setting up a Turnpike or otherwise.”

Turnpike, or the clipping pike, was often used to refer generally to roads in the nineteenth century, and the expression “coming down the pike” was another way of saying “coming down the road.”

By the late 1800s, figurative senses were emerging and taking hold. An 1898 story in the Dayton Herald had the line “Bowling, if dead, is the liveliest corpse that ever ’came down the pike’, as they say on the bowery.” The quote marks suggest that figurative “down the pike” was a newish expression at the time.

Pike was also used as a synonym for boardwalk or midway, and in 1903 the organizers of the St. Louis World’s Fair announced that the upcoming fair would call its promenade “The Pike,” to distinguish it from Chicago’s Midway. Perhaps St. Louis got the idea from Long Beach, California, which debuted a boardwalk amusement zone called “The Pike” even earlier—in 1902. In any event, St. Louis encouraged visitors to “Come Down the Pike,” and there was later a Broadway musical titled “Down the Pike” whose second act took place at the 1904 World’s Fair.

The figurative sense of “coming down the pike” took hold but remained sporadic in the early twentieth century. A 1905 Portland, Maine, newspaper talked about “nothing but anarchy coming down the pike” and “chaos coming down the pike.” A 1936 issue of the International Stereotypers’ and Electrotypers’ Union Journal which refers to “The fall election… coming down the pike.” Both examples are clearly oriented toward time and events rather than space.

By the 1950s the sense of “coming down the pike” to mean happening in the future was increasingly common and it took off in the 1960s and 70s, after the completion of the Interstate Highway System.

With language, you never know what’s coming down the pike.

Featured image: the New Jersey Turnpike, 1992, via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 2.5)

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers