Oxford University Press's Blog, page 45

August 30, 2023

Language peeves and the word peeve

Language peeves and the word peeve

I assume that since for quite some time there have been no new comments, the discussion about good and bad English in the pages of this blog is over, at least for now. Below, I’ll address very briefly the comments and private letters I have received. I very much appreciate the idea that language needs not only motors and brakes but also steering. That is why schools exist. But teaching has become a dangerous occupation, and “steering” is at present chaotic. The remarks I have received can be classified under several rubrics.

Redundancy“He returned a whole ten books.” Whole, like very, completely, and so forth, makes a trivial statement more emphatic; hence its allure. Remember the whole nine yards.

BuzzwordsThe use of clichés allows one to speak like a machine and to be rewarded with a membership in a prestigious club. You say so-and so made history and feel how important you are, almost as important as the person you described. Equally beautiful is the phrase empower and uplift.

Sham grandeur and verbositySomeone says epicenter instead of center and believes that the statement has acquired additional weight. Based off of instead of based on may belong here too: the longer a statement, the greater weight it appears to carry. (Curiously, Melissa Mohr, who interviewed Professor Fridland for The Christian Science Monitor—search for the short piece on the Internet—did not address any of the questions that interested us.)

Finally, the English verb like never meant “to be equal to.”The etymology of peeveAnd now some ideas about the etymology of peeve. The word lives up to its meaning with enviable accuracy. Only the last stage of its history is known: peeve is a twentieth-century back formation from peevish, that is, the root was abstracted from the adjective. The question then is only about the origin of this adjective, rather than the noun. Peevish was first recorded in English texts at the beginning of the fourteenth century but was rare (rare in texts!) at that time. Later, the examples multiplied, but as the OED indicates, it is often hard to understand what peevish in some of them meant, even though all the senses seem to have been negative. Before looking at the rather numerous attempts to explain the word’s origin, I may suggest two things. First: if the word had been borrowed from some foreign language (most likely, Old French), its Middle English meaning would have been more transparent. Second: the adjective seems to have originated in slang as a term of disapproval, mockery, or abuse, and as we know from the history of modern slang, the etymology of such “low-class” words is usually hard to reconstruct.

Both men and women can be peevish.

Both men and women can be peevish.The more or less ascertainable early senses of peevish are “doting, silly; malignant; obstinate, ill-tempered.” Today, a peevish person is irritable and fretful. Among its modern synonyms, we find “petulant, cross, ill-tempered.” Unexpectedly, in a 1691 dictionary, peevish is glossed as “witty, subtil” (a north-country word). The reference may have been to things bizarre, too subtle, rather than to a bent for humor. Shakespeare used the adjective more than once and understood it as “silly, senseless; perverse.” He applied it not only to human beings (boys, for example) but also to harlotry (so in Hamlet) and tokens. Walter W. Skeat summed up the situation so:

Thus, the various senses are “childish, silly, wayward, froward, uncouth, ill-natured, perverse” and even “witty.” All of these may be reduced to the sense “childish,” the sense of witty being equivalent to that of “toward,” the child being toward instead of froward.

Fro-ward indeed goes back to fro (that is, from: compare to and fro), as opposed to to-ward, but one wonders whether the common denominator of all the senses Skeat listed is indeed “childish.” “Senseless, silly, perverse,” as in Shakespeare, seem to capture the message of the adjective better. The idea of stupidity and sometimes meanness appears to underlie most of the recorded senses. It seems to have always been bad to be peevish, and with regard to meanness, one may cite Scottish pewische “niggardly, covetous,” recorded by the great lexicographer John Jamieson.

The most peevish birds in the English-speaking world at large.

The most peevish birds in the English-speaking world at large.Photo by Andreas Trepte, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.5

The earliest attempts to discover the origin of peevish are not less sophisticated than the latest, and in a few cases, they are even more reasonable. From some sound-imitative verb like pew: “to complain; mutter”? (The adjective pewish “cross, froward” is, apparently, a doublet or a spelling variant of peevish.) Or from beeish “resembling a bee” (compare waspish)? (This is ingenious but fanciful.) Or perhaps from pipe or pew “to complain, to emit a mournful sound”? All such attempts assumed that peevish was a native word.

However, French etymons have also been proposed. Among the glosses of peevish, the adjective perverse turned up more than once, and perverse has been suggested as the source of the English word. It too surfaced in English in the fourteenth century and meant “perverted, wayward,” and “froward” (the latter is familiar to us from the definitions of peevish). Above, I expressed my doubts about the Romance source of peevish. Here, I may add that Middle English perverse and peevish seem to have belonged to different registers and that perverse never displayed such a variety of senses as did peevish. Leo Spitzer, a distinguished Romance etymologist, suggested the Latin etymon expavidus “startled, shy,” which surfaced in Old French in the form épave (an epithet applied to stray animals). He recognized some phonetic difficulties in his reconstruction but attempted to explain them away.

I am a very foolish fond old man.

I am a very foolish fond old man.Painting by Robert Smirke, The Awakening of King Lear, via Wikimedia Commons, public domain

As we have seen, some early students of English etymology believed that peevish is a sound-imitative word. They compared peevish with the bird name pewet ~ peewit. Such was also Skeat’s final opinion, who rewrote his long verdict from scratch: “The leading idea seems to be ‘whining’, ‘making a plaintive cry.’” From the evidence we have seen (“doting, malignant, ill-tempered,” and so forth) it certainly does not follow that the sought-for common denominator is “making a plaintive cry” (curious how even the best researchers try to cut their cloth according to their readymade coats). But the idea of deriving peevish from an onomatopoeia seems fairly reasonable. Birds often supply people with metaphors related to stupidity. A fool in German is a silly goose (du, dumme Gans), while in English, a silly goose is a nervous, jittery person who has to stop worrying and come to business. Likewise, a booby is a fool, and being ga-ga is not an accomplishment either.

Perhaps peevish was indeed one of such words. The reference would have been to the pewet-peewit called this for the sound it makes. If so, the word first meant “stupid, brainless.” The rest is plain sailing. From “stupid’ as the semantic kernel one may go in many directions. A classic example is fond, which first meant “foolish,” then “foolishly affectionate,” “doting,”, “desirous,” and finally, “having a strong liking.” Other than that, as regards its origin, fond is a rather obscure word. Thus, I disagree with the common verdict that peevish is a word of unknown origin. And if I am wrong, I’ll be happy to accept the proverbial booby prize.

August 29, 2023

The revelation of the Book of Mormon at 200 [podcast]

The revelation of the Book of Mormon at 200 [podcast]

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, also known as Mormonism, is one of the fastest growing global religions—as of the latest reports, there are over 17 million members, and while it is still predominately considered an American religion, almost half of those members live outside of the United States due to the church’s reliance on global missionary work.

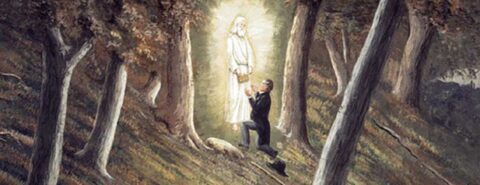

This September marks the 200th anniversary of the Church’s founder Joseph Smith’s first vision of the angel Moroni. In this vision, the angel told Smith that he had been chosen to restore God’s church on earth and instructed him to go to the Hill Cumorah in western New York State, where he would discover a set of gold plates. Smith translated and published these plates as the Book of Mormon in 1830, giving birth to a new religion.

On today’s episode, we’re joined by two preeminent scholars on the history and theology of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to discuss with us the legacy of Joseph Smith’s Gold Plates as well as the state of academic scholarship surrounding the Book of Mormon.

First, we welcomed Richard Lyman Bushman. Bushman’s books include Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling and Mormonism: A Very Short Introduction. His most recent book with Oxford is Joseph Smith’s Gold Plates: A Cultural History, which traces the history of the gold plates over the last two centuries. We then interviewed Grant Hardy whose new The Annotated Book of Mormon is the first ever fully-annotated, academic edition of the book. His previous works include The Book of Mormon: A Reader’s Edition as well as Understanding the Book of Mormon (OUP, 2010).

Check out Episode 86 of The Oxford Comment and subscribe to The Oxford Comment podcast through your favourite podcast app to listen to the latest insights from our expert authors.

Oxford Academic (OUP) · The Revelation of the Book of Mormon at 200 – Episode 86 – The Oxford CommentRecommended readingFor a more in-depth introduction to Joseph Smith’s visions and the founding of the church, read the chapter “Revelation” from Richard Lyman Bushman’s Mormonism: A Very Short Introduction.

You can also read more of Bushman’s scholarship on the Gold Plates and Joseph Smith’s translation and publication of the Book of Mormon in the chapter “The Gold Plates as Foundational Text” from Foundational Texts of Mormonism.

To learn more about the Book of Mormon’s language, style, organization, and religious claims, read Grant Hardy’s “A Brief Overview: Narrator-based Reading” from Understanding the Book of Mormon.

Finally, Terry L. Givens explores the scriptural implications of the Book of Mormon and its relationship with biblical doctrine in “’Plain and Precious Truths’: The book of Mormon as a New Theology, Part 1—The Encounter with Biblical Christianity” from By the Hand of Mormon.

Transcript The-Oxford-Comment-Episode-86-transcript-finalFeatured image: C.C.A. Christensen’s painting of Joseph Smith receiving the Golden Plates from the Angel Moroni at the Hill Cumorah. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons .

August 28, 2023

Alzheimer’s: do we focus too much on new treatments?

Alzheimer’s: do we focus too much on new treatments?

Virtually every new discovery in Alzheimer’s disease treatment is greeted with excitement. In July 2023, the drug donanemab was reported to have slowed the progression of symptoms in early stage patients. A few weeks earlier the FDA gave accelerated full approval to lecanemab. Two months earlier, news came of a rare gene variant, RELN-COLBOS, that appears to protect those who carry it, and of blood biomarkers for astrocyte reactivity that could be used to screen patients to identify those most likely to progress to the disease. Two years earlier, in June 2021, the FDA gave approval to aducanumab, to much fanfare and controversy.

Is the level of excitement accompanying these developments justified? To be sure, they seem promising. Risks of serious brain bleeding and swelling attend the use of all three drugs, though, and the benefits of even the most impressive of them are modest, at best: a four-to-seven-month slower decline in cognition over 18 months for the most optimal patients, with no indication that eventual progression to severe stages is avoided. Effectiveness studies, moreover, often focus on physiological effects associated with the disease that are not actual improvements in the patient’s condition—so-called surrogate endpoints. Amyloid plaques—clumps of beta-amyloid protein in the brain—and tangles of protein within neurons known as Tau tangles are commonly used surrogate endpoints. Some experts are skeptical that amyloid and Tau are key to understanding what causes the disease. Dr Tia Powell, Director of Montefiore Einstein Center of Bioethics, for example, notes that some patients with well-developed Alzheimer’s do not have high amyloid plaque or Tau tangles, and some patients with high amyloid and Tau never develop Alzheimer’s.

The public attention reflects in part the excitement of patients. Jay Reinstein of Durham, NC, for example, age 62 with early-mid stage Alzheimer’s, is enthusiastic about lecanemab: “If it gives me six or 12 or 24 more months at the current level, that’s a great thing.” At the rate of slowdown shown in the tests submitted for FDA approval (noted above), however, Reinstein in 26 months will be where he would otherwise be in 36. That’s not likely to be the “current level” for 6-24 additional months that he imagines.

Hope is good, but how realistic should it be? Should it add to research institutes’ leverage in gaining funding, and pharmaceutical companies’ ability to obtain approval for very marginally effective new drugs? Widespread fear of a disease can be the springboard to determined and constructive effort, but it can also lead to less rigorous, careful assessment. More important is that in the meantime, realistic approaches that can already benefit patients may get overlooked.

Live better with dementia“In supported decision-making, trusted others assist persons to still make their own decisions, preserving the dignity of self-determination.”

The sensitive and perceptive kinds of care developed in specialized centers like the Penn Memory Center could be more widely used. An element in this approach is “supported decision-making,” a supplement to the guardianship and surrogate decision-making used for those who have lost this capacity. In supported decision-making, trusted others assist persons to still make their own decisions, preserving the dignity of self-determination. Such elements should be standard-of-care.

Opt out of life with dementiaIn addition to living better with whatever level of dementia one has, people can do something more definitive to avoid living to its most advanced stages. That future is what many fear most—years of lingering, withering life when one only weakly communicates with others (if at all), does not recognize one’s closest loved ones, and is no longer capable of anticipating tomorrow, or remembering yesterday when tomorrow comes. To many, a life that ends like that is for them worse than if they simply did not live that long. With or without those years, this life is their life. This subjective value underlies the self-determination at the core of the doctrine of informed consent, including the right to refuse lifesaving treatment.

Yet it is difficult for people with progressive dementia to exercise this right, for when they get close to severe dementia, they are not likely to have the capacity to make medical decisions. Fortunately, there are two feasible ways around this.

Withhold life-sustaining treatment by advance directiveAdvance directives have been well established morally and legally for decades. When still capable of making such a directive, a person can instruct their healthcare agent and providers to withhold life-extending care when they reach a certain stage of dementia. They can also instruct them to withhold such care somewhat before that stage if it is possible that no such life-threatening condition is likely. By such instructions they can significantly reduce their odds of reaching a stage they badly want to avoid.

Such a strategy using advance directives to refuse treatment is legal, but it has a clear drawback: not everyone is presented with the opportunity to refuse life prolonging treatment. Another course of action, though, is available.

Voluntarily stop eating and drinking (VSED)Relatively unknown, VSED is a legal way to hasten death when no illness provides the opportunity to die by refusing lifesaving treatment. When well supported, it provides a peaceful and reasonably comfortable death in 7-14 days. It is certainly not for everyone, requiring considerable determination to get through the hunger of the first 36-48 hours (after which hunger dissipates) and after that, to endure the dry-mouth and thirst that do not as readily dissipate. Good palliative measures, though, can help immensely. For those who are sufficiently determined not to live longer, VSED is a viable option.

The problem in the case of Alzheimer’s, however, is that once people lose executive function, they will not be able to carry out VSED. To avoid that, they must do VSED “preemptively,” significantly before executive function and decision-making capacity are lost. They will need to begin VSED when they are still assured of their capacity, and by doing that they are likely foregoing some time worth living.

Such preemptive VSED may sound extreme, but there are well-documented cases of it (and undoubtedly many others). To be sure, the person would give up some valuable time they would liked to have had, but they avoid what they fear most, years of severe dementia.

These last two ways of dealing with Alzheimer’s are seldom acknowledged in the public discussion (or by providers and caregivers). The Alzheimer’s Association does not mention, much less highlight, them. The headlines go to every new treatment, no matter how marginally effective. Some lines of research from those treatments may indeed pay off decades down the road, with huge benefits for humankind, but let’s not fail to attend to the things that people with progressive dementia can realistically do already through taking ownership of the real choices they can make about how their lives end.

Featured image by Christina Victoria Craft via Unsplash, public domain

August 26, 2023

The British Army: how is the Army meeting changing societal priorities?

The British Army: how is the Army meeting changing societal priorities?

It was commonplace among the pioneers of the study of civil-military relations in the 1950s to stress that armies reflected in very sharp focus the social structure, degree of technological progress, and creative vigour of the societies they sought to defend. In short, armies were a mirror of their parent society. But these early proponents of civil-military relations theory struggled to explain why Britain did not fit their proffered models.

To a degree Britain fitted into the wider Western relationship of war to the development of the modern state but also stood outside European practices by virtue of an army primarily raised by voluntary enlistment other than in the twentieth century. An island, maritime, and imperial mind-set was fundamentally different from that of Continental powers with open land frontiers. Ambiguities in public responses to the army in Britain were shaped by continuities in environment and culture that marked its exceptionalism. Voluntary enlistment ensured that the army was unrepresentative of society and even wartime conscription and national service was selective rather than universal. In the past what might be termed the “amateur military tradition” represented by militia, yeomanry, volunteers, and territorials provided a better link between army and society. In the twenty-first century, however, the “footprint” of the amateur soldier in the wider community has contracted even further than that of the regular. The “Army Reserve Centres”—the modern version of the old drill halls – have been banished to the peripheries of communities.

Despite wider popular sympathy for the army than previously as a result of the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, there is more disconnect between army and society than before. Public sympathy does not fill the ranks nor does it equate to understanding, not least when public perception of the circumstances in which the use of military force is justifiable changed dramatically as a result of the deceit visited upon the public by Blair’s government prior to the Iraq War. In any case, an ever-smaller army has faced increasing challenges from changing strategic priorities, changing military environments, continuing and unrelenting financial pressures, and often dysfunctional political and military decision-making.

A survey undertaken for the British Forces Broadcasting Service’s Remembrance Campaign in 2017 revealed that 85% of those asked were unaware of more than half the conflicts or military deployments in which the British armed forces had participated since 1945. Notwithstanding financial reductions, the army has confronted a change in the age profile of the UK population, those aged 18-22 declining by a quarter between 1987 and 2000. Familiarity with the army also decreased. In 1997, 20% of those aged 35-41 had a direct link to individuals with a military background broadly defined. That was true of only 7% of those aged 16-24.

Society is less deferential and more individualistic in ways testing traditional military culture. The army felt obliged to advertise its “right to be different” in a doctrinal publication, Soldiering: The Military Covenant, in 2000. It has had to come to terms with recruits from more unstructured backgrounds as well as coming to terms with issues of gender and sexuality. From 1991, pregnancy no longer resulted in dismissal whilst the prohibition on homosexual acts was lifted in 2016 and HIV-positive recruits permitted to enlist from 2022. An earlier zero tolerance on drug use was lifted in 2019. Bizarrely, recruitment was outsourced in 2012 and the army’s cause has not been helped by cases of “beasting” of recruits; excessive shouting and swearing of recruits was prohibited in 2016. Cases of racial discrimination have also arisen, non-white soldiers including overseas recruits representing 13% of army strength in 2020.

“Society is less deferential and more individualistic in ways testing traditional military culture.”

Military wives are increasingly better educated and more likely to pursue their own careers than in the past and the army has struggled to improve family life. In 2021, the National Audit Office reported critically on the state of army housing, its privatised maintenance remaining a disgrace. Treatment of veterans remains an underlying and unresolved problem that has not been adequately addressed. The 2011 Armed Forces Covenant has certainly assisted in drawing in central and local government, business, communities, and charities to support serving personnel, service leavers, veterans, and families. It contrasts with the extended indemnities handed out to terrorists in Northern Ireland by Blair’s government amid the continued vexatious persecution of veterans.

Smaller than at any time since the eighteenth century, the army is simply unable to match politicians’ continuing aspirations for a “global Britain” in a world of increasing tensions. Defence Secretary, Ben Wallace, admitted that the army was “hollowed out and under-funded” in January 2023. The promises by Liz Truss during the Conservative leadership contest to increase defence expenditure to 3% of GDP by 2030 have fallen away under the Sunak government to a mere 2.25% at some point in the future. Understandably, considerable assistance has been given to the Ukraine in terms of training, equipment, and munitions but, as Andrew Roberts pointed out recently, Britain’s own stock of munitions has been woefully depleted based on consumption rates in the present war. Too many ministers of defence have been less than distinguished and some truly pitiful. With two exceptions all had some military experience until 1992, the trend being reversed with Ben Wallace’s appointment in 2019. The last prime minister with any service experience was James Callaghan.

It must be said that Iraq and Afghanistan demonstrated the army’s inability to embrace institutional learning to the extent required, and of its leadership to accept accountability for military failure. The tri-service Permanent Joint Headquarters established in 1966 failed to recognise the reality of the insurgency being faced both in Iraq and Afghanistan. History suggests the unexpected is always likely to occur and the army will always do its best but, as the Chilcot enquiry concluded in 2016, an ingrained “can do attitude” prevented “ground truth from reaching senior ears.” Britain has been fortunate in its army—indeed, more fortunate than it has often deserved—but institutional limitations remain.

August 25, 2023

The contested nature of religious liberty in today’s America

The contested nature of religious liberty in today’s America

Several decisions recently made by the United States Supreme Court, along with an escalation in Christian Nationalist rhetoric among right-wing American politicians, have brought the issue of religious liberty to the surface in today’s media. Much of the commentary has focused on a paradox: the concept of religious liberty has increasingly been used to suppress minority or disempowered voices. Such critical commentary, however trenchant, ought not to obscure the need for a reinvigorated idea of religious liberty without its oppressive implications.

The majority of justices in today’s Court, many of them from Roman Catholic backgrounds, have strengthened protections for religious practice in controversial rulings (not to mention the Court’s overturning of Roe v. Wade). In a case that set a United States Postal Service worker against a supervisor who required him to work on the Sabbath, the Court challenged previously held standards that favored employers in such cases. In a highly publicized case, the Court ruled against a state of Washington schoolboard that disciplined a high school football coach who prayed on the school’s football field with students. The Court also ruled against the city of Boston for refusing to fly the flag of a Christian group over the City Hall when it had allowed other interest groups to do so. In addition, the Court sided with a Colorado web designer who refused, on religious grounds, to create web designs for weddings of same-sex couples. In these cases, as in others, the majority opinion of the Court was expressed as a protection of religious liberty in the face of federal, state, and municipal restrictions on religious practice.

Seen in the light of a more widespread turn in Republican political discourse (and legislation) toward policies often informed by conservative Christian instruction, including restrictions on LGBTQ rights and abortion, such rulings have cast a shadow over the concept of religious freedom. Editorialists have sometimes pitted the principle of religious freedom against other valuable principles such as equality before the law or simple fairness.

Critique of religious freedom as a principle has precedents in a line of anthropological, philosophical, and historical writing for the past half century. Many twentieth-century critics, from Michel Foucault to Talal Asad, had voiced a deep suspicion about western, Enlightenment-inflected, eighteenth (or late-seventeenth)-century conceptions of religious liberty or secularism—the Locke to Jefferson celebratory narrative—as complicit in imperial politics, statist discipline, and cultural hubris. Critical race theorists often have dismissed self-congratulatory accounts of American religious liberty as a diversion from the story of racial oppression. Historians of the English state have deconstructed the Anglo-American narrative of liberty as, in the end, a mere tool for a Protestant regime in a nationalist form.

There is much to be said for such criticisms. Yet there is another aspect of American politics in which a recovery of older—even Lockean or other Enlightenment-driven—notions of freedom of conscience and religious liberty may be helpful. Right-wing American politicians increasingly have voiced explicitly Christian nationalist sentiments. At the most recent Faith and Freedom Coalition gala, Donald Trump claimed that he, as President, had upheld the interests of evangelical Christians in his appointment of pro-Christian justices who, among other rulings, invalidated the central tenets of Roe v. Wade. Trump’s presumed rivals for the Republican nomination for President in 2024, Mike Pence and Ron DeSantis included, were also at the gala, competing for evangelical support by arguing that they stood for genuine Christian values even more resolutely than did the former president.

As one editorialist recently complained, such evidence of Christian nationalism is hardly limited to high-profile proto-campaign events or presidential politicking. Once allied with free-speech movements and freedom of religion platforms, Christian commentators have sometimes advocated strict speech codes, claims that the United States ought to declare itself to be a Christian nation—with laws that follow suit from that claim—and rejection of Islam as an un-American religion. Movements such as Roman Catholic “integralism” and Protestant “dominionism,” along with books such as Stephen Wolfe’s The Case for Christian Nationalism, published by Canon Press in Moscow, Idaho, advocate for an end to religious liberty and for the establishment of a theological-political order in the United States. Such sentiments suggest the intellectual backdrop for recent turns in the Supreme Court and political electioneering.

They also suggest that scholarly suspicions ought to be tempered by a consideration of how the discourse of freedom of conscience in early Anglo-America, with all of its Enlightenment presumptions, might offer some clues to a recovery of a robust notion of religious liberty. We do not have to accede to the Anglo-American nationalism and imperialism, or the implicit Protestant biases, or the racism of eighteenth-century proponents of religious liberty to appreciate and reformulate some of their ideas about freedom of conscience and the necessity of distinguishing a nation’s wellbeing from any one religious creed. Such a consideration might at least hint at ways to rebuff the worst of the religious politics that afflicts us today.

Featured image: “Supreme Court of the United States – Roberts Court 2022” via Wikimedia Commons, public domain

August 23, 2023

No release from an etymological entanglement

No release from an etymological entanglement

Last week (16 August 2023), I wrote that I had received two questions: one about the verb glance and the other about the noun entanglement. The previous post dealt with glance. Now I am ready to tell an incomplete tale of the noun and the verb tangle. The tale is incomplete, because the sought-for etymology remains a matter of speculation.

Tangle surfaced in English in the middle of the fourteenth century. The earliest recorded Middle English form of tangle is tangil, but, strangely, Richard Rolle of Hampole (1290-1342), once a very well-known and widely read mystic, who wrote his works in both Latin and English, also used the form tagil. He did not mean to mystify us, but as far as I can judge, the origin of the word that interests us today depends to a great extent on the relation between tangil and tagil. Those who have read the blog post on glance may remember the term nasalization, that is, the appearance of n in a seemingly n-less root (messenger versus message, stand versus stood, and so forth). Once again, we face a similar question and wonder how tangil and tagil are related. The previous discussion of glance alongside Old French glacier “to slide” cannot be resolved to everybody’s satisfaction. Perhaps those words are indeed related, but what facts can we marshal to clinch the argument? Our case today is better. Middle English tangil and tagil alternated as two forms of the same word; they were certainly related.

Richard Rolle of Hampole

Richard Rolle of HampoleVia Wikimedia Commons, public domain

Our oldest etymologists knew the word tangle well, but, contrary to my usual practice, I’ll begin with some later views on its origin. Walter W. Skeat, our prime nineteenth-century authority on the origin of English words, never changed his opinion from the early eighteen-eighties to 1911 (the year the last edition of his “concise” dictionary was published). He believed that tangle was a loan from Scandinavian and cited Danish tang “seaweed” (along with its Norwegian and Icelandic cognates and northern English tang of the same origin) as its source. Skeat’s opinion was repeated in many contemporary works. Only the usually neglected Century Dictionary, a source of well-thought-out etymological information, despite its great indebtedness to Skeat, noted: “…but the development of such a verb from a noun of limited use like tangle is somewhat remarkable, and needs confirmation.” I was pleased to find this opinion quoted in recent sources, because it sounds correct.

The emergence of a new English word of Scandinavian origin in the fourteenth century causes no surprise, and the name of a seaweed is, almost certainly, related to the verb tangle, but it cannot be its etymon. (Incidentally, several dictionaries prefer to discuss entangle, rather than tangle, which turned up in texts two centuries later than tangle; en– is a Romance prefix, so that entangle is an etymological hybrid, not too rare a case in the history of English words. The suffix –ment in the noun entanglement is Romance too, and so is the prefix dis– in disentanglement. In such words, the name of the Scandinavian seaweed is enwrapped in foreign morphemes.) The distant origin of that name presents no interest in today’s context. Perhaps it shares the root with thick, which once upon a time also had the consonant n after a vowel.

This is an entanglement indeed!

This is an entanglement indeed!Electricity wires via Pexels, public domain

It will be noticed that Skeat did not discuss Rolle’s n-less form tagil. Neither did the etymologists of the OED. This omission is especially curious in light of the fact that some of their most visible predecessors, when dealing with the origin of tangle, regularly mentioned Gothic tagl “hair,” an indisputable cognate of English tail, from tægel, as its source. Naturally, both Skeat and the editors of the OEDwere aware of the old tangle ~ tagl comparison, and I wonder why they ignored it without minimal discussion. Dictionary makers often say something like: “Such and such an idea is unacceptable” or add a short explanation to this peremptory verdict. Perhaps Skeat and others concluded that an animal tail, a most tidy appendage, rather than a mess, cannot have anything to do with an unkempt tangle of hair (mere guessing).

I do not know whether my guess has justification, but I would like to note that tail is a generic term: it is the name applicable to any tail. People have also coined a few specific terms, such as bush, scut, and dock. Perhaps tail was initially one of such descriptive words. In any case, the origin of words for “tail” is usually far from clear. The fact that outside Germanic, English tail has a related form in Irish or that Latin cauda perhaps has a cognate in Albanian may bring joy to language historians but to no one else (cauda is sometimes supposed to be a “low” word by origin). Equally obscure and perhaps partly sound-symbolic is Proto-Slavic xvost” (Russian khvost and others). The Serbo-Croatian cognate of khvost means “thicket, brushwood, undergrowth” (!), thus, a messy heap. Words constantly narrow their meaning. For instance, meat once meant “food” (as it still does in sweetmeat and in meat and drink), fowl was a general word for “bird” (like German Vogel), and so forth. Perhaps tail did not always refer to the tidy appendage we know. I realize that with this proposal I am stepping on a mine but stay calm. A researcher always faces two dangers: to say nothing new (and be accused of wallowing in trivialities) or to offer a novel solution (and be castigated for the rash proposal). One is damned if one does and damned if one doesn’t. Why worry?

Everybody has a tail.

Everybody has a tail.L: sparrow, via Pxfuel, public domain. R: fox, via Wallpaper Flare, public domain.

Fully aware of the dilemma, I would like to return to the oldest etymology of tangle. Perhaps the initial form (that is, tagl) had no n in the middle and meant “a mass of hair, tidy or otherwise,” with a later narrowing (specialization) to “a bunch of hair at an animal’s rear end.” Tails come in different shapes and forms: compare a sparrow, a peacock, and a fox (all of them have tails). Given my idea, tangle will emerge as a related form of tagl with nasalization. The name of the seaweed will remain in the family but not as the source of the verb tangle. However, if the old etymology is wrong, it would be good to hear some hypotheses about why it was dismissed without discussion. An exchange of opinions is always better than silence. Etymologists frequently resuscitate old hypotheses. Given the fact that tangle lives up to its meaning so well and refuses to reveal its origin, a new discussion may be of some worth. If human beings have not shed their tails (alas, all is lost except for the tailbone and tailcoats), the word would probably have attracted more attention.

Such is my version to the tale of the tail. Tongue has nothing to do with tangle, and tongs should probably stay away too.

Featured image by Steve Harvey on Unsplash, public domain

August 21, 2023

Environmental remediation of sea-dumped chemical weapons: courageously fixing the mistakes of our past

For many generations to come, there is only one place where we can live, and that one place is the Earth. It is therefore imperative that we take care of our home, rather than treating the Earth as if it were given to us for our own selfish exploitation. The impending collapse of some ecosystems is motivating more and more of us to take action in the present to avoid suffering in the future—all the more since much of this suffering will be experienced most intensely by communities that wield relatively less political and economic power. But few will be fully spared.

It has become axiomatic that the health of the Ocean is essential for the survival of not only marine life itself, but also for the whole Earth. The land and the sea are one. In the ignorance—or naiveté—of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries CE, some thought—and daresay still do think—that the Ocean’s immensity was such that we humans could not harm and exhaust it, the so-called “infinity of the oceans.”

A myriad of scientific studies has revealed that the Ocean has been seriously impacted by land-based pollution, global warming, overfishing, emissions from vessels, oil spills, and the dumping of industrial waste, radioactive waste, and munitions, including chemical weapons. The nature of this environmental harm is inherently transboundary in nature: although we have created legal delimitations in the Ocean and seas, all things in nature are connected. The marine environment knows no geo-political borders, and we will all have to deal with the degradation of the Earth’s ecosystems in the coming decades and centuries.

“Instead of a resource to be exploited, we need to regard the Ocean as integral to our survival on Earth.”

It is time for a radically different approach to the Ocean and the living creatures that inhabit it. Instead of a resource to be exploited, we need to regard the Ocean as integral to our survival on Earth —the one place in the Universe where we can live, at least for the foreseeable future. This reconceptualization of our relationship with the Ocean may bring the need to include new legal arrangements to protect it; however, so far, the adoption of legal promises to preserve and protect the Ocean has not led to adequate protection and action on the part of public and private stakeholders. The London Dumping Convention, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, the Regional Seas Conventions, and customary international law (specifically the principles of prevention, precaution, and cooperation) entail mandatory legal obligations for the protection of the Ocean. These binding legal instruments and principles of law require the cleanup of sea-dumped chemical weapons, not only in areas that are under the sovereignty of states, but in all areas of the Ocean. In addition to their territorial seas and exclusive economic zones, states must avoid a “tragedy of the commons” where all have access and can make use of the high seas, but no one is acting as the caretaker of those areas to preserve them for future generations.

The chemical weapons that were dumped into our Ocean and seas after the world wars of the twentieth century CE have been languishing there, in some cases, for over 100 years with little to no action to environmentally clean them up. Chemical weapons have been dumped in all the areas of the Ocean (except the Antarctic) and also in many seas. Estimates range from 1 to 1.6 million tonnes. Many of them are in shallow waters and regularly wash up on shore or are caught in fishing nets. People are injured every year in accidents involving sea-dumped chemical weapons. Many of the chemical weapons have already contaminated the marine environment. In time, the remaining munition casings will erode, and their toxic contents will be released into the marine ecosystem. It is not yet fully known how devastating the effect will be, but scientists have already observed the contamination of the flora and fauna surrounding chemical weapon dump sites. Sea-dumped chemical weapons are therefore yet another environmental pressure on an already troubled marine environment.

The time for action is long overdue. The problem is a finite one with finite solutions. A worldwide intergovernmental solution might not be realistic, as stakeholders historically have even tried to legally exempt themselves (via international treaty) from being legally obligated to clean up sea-dumped chemical weapons and so far have been unwilling to devote the resources necessary to the remediation of the munitions we know about—not to mention the ones that are yet to be located. Rather, an incremental and iterative process might be more feasible and achievable.

“The time for action is long overdue. The problem is a finite one with finite solutions.”

Efforts to clean up sea-dumped chemical weapons could also be seen as a political, financial, and technological challenge. One place to start would be to require off-shore projects to adopt a holistic approach to cleaning the seabed for future projects, rather than avoidance or underwater relocation of the munitions, which can be considered re-dumping. Public entities need to provide subsidies to off-shore ventures to clean up munitions in order to provide economic incentives (necessary in our market economy) for the remediation of the munitions, either in situ or on land. Such subsidies could, for example, take the form of a “bounty” paid for each remediated munition or site.

An international organisation could serve as a coordinating agency for efforts in this area, such as a centralised database for the location and status of the munitions, a clearing house for best remediation practices, and the administration of a modest, voluntary trust fund to finance further research and operations. A pilot project could be undertaken in the next years to fully remediate a site in the Baltic Sea—an area of particular concern due to the large number of dump sites, the low depth of the water, and the increased economic activity there. Lessons would be learned from such a project and then applied to future cleanup projects.

These efforts would be undertaken as voluntary cooperation and would be consistent with the legal obligations undertaken by states to preserve and protect the Ocean. In this manner, the taboo that has long been associated with sea-dumped chemical weapons can be lifted, and we can get on with the work of altering the mistakes of our past, so that we can restore the balance of our planet’s Ocean, upon which we all depend for survival.

Featured image: Ivan Bandura via Unsplash, public domain

August 18, 2023

Communicative luck reduction: machine-like or social (or both)?

Communicative luck reduction: machine-like or social (or both)?

As a rule, a linguistic success is a non-lucky success. In other words, grammaticality, communication, interpretation, mutual understanding, and the forms of social coordination thereby enabled, succeed by innate capacity, acquired skill, and social convention, as opposed to luck or chance. To be sure, we sometimes manage to luckily pick out the same referent as an interlocutor (e.g., Clark Kent and Superman), hope that we are using the right words in a second-language conversation, and express the right message with ambiguous emoticons or jokes. Yet, while we occasionally have the sense that we are rolling dice with words and hoping for good luck, meaning and communication would be impossible if we only and always succeed no better than luck would allow. Stable grammars, word meanings and conversational norms require very robust regularities.

Meaningful communication requires a reliability far greater than chance produces. Day in and day out, communicating with words is drastically different from rolling dice at a gaming table. Getting things wrong because of a linguistic misunderstanding can prove inconvenient at best and fatal in the worst circumstances, but even good luck is bad too because our real communicative intentions have failed and common ground for subsequent linguistic exchange has not accrued. Thus, if we interpret luck as achieving a goal with a rate not higher than chance, all kinds of communicative actions require a reliability much greater than luck affords. Luck in linguistic communication must be the exception rather than the rule.

“Social coordination succeeds by innate capacity, acquired skill, and social convention, as opposed to luck or chance.”

Recently, large language models (LLM) have challenged the assumption that only humans can communicate through language. ChatGPT employs luck-reducing mechanisms to achieve a very high success rate in sentence completion and contextualization, at least at the performance level. A crucial question facing us with the rise of LLMs is how, if at all, human linguistic success differs from ChatGPT’s linguistic success? One novel and fruitful way to pursue this question is to compare how each system manages to succeed in linguistic luck reduction.

Do human and AI systems utilize the same luck-reducing mechanics, or are they essentially different? How we answer this question has significance for understanding fundamental issues in linguistics and philosophy of language, as well as current issues about the nature of language raised by LLMs. How do we humans reduce dependence on luck? How does ChatGPT do it? What, if anything, is the difference between the two?

We suggest the following broad framework for pursuing the questions above, although it leaves us with a fruitful dilemma rather than an easy answer. We suggest that causation, inference, and intention are the main sources of luck reduction in syntax, semantics, and pragmatics. Humans utilize (at least) this degree of variation in the luck-reducing mechanisms that underlie reliable communication at different levels of linguistic competence. (More detailed frameworks for approaching linguistic luck reduction can be found in Linguistic Luck: Safeguards and Threats to Linguistic Communication.)

“A crucial question facing us with the rise of LLMs is how, if at all, human linguistic success differs from ChatGPT’s linguistic success?”

Unlike these diverse sources of linguistic luck reduction in humans (some of which we share with animals), ChatGPT seems to be a “one-trick pony” when it comes to luck reduction. LLM luck reduction is based on single-method, statistical-predictive analysis of syntactic features. The way in which recent LLMs compress information into the next most likely set of words or features might be enough to mimic the causal, inferential, and intentional mechanisms employed by humans.

The lack of diversity in luck-reducing mechanisms appears to be one clear difference between human linguistic success and ChatGPT linguistic success, and may point us to other fundamental differences. However, to show that any difference in luck-reducing artillery indicates a fundamental difference in linguistic capacities, it must be shown that the diversity of human mechanisms cannot be reduced to the powerful, monolithic luck-reduction of ChatGPT (and future LLM systems). The diversity of human mechanisms may simply reflect the limited capacities we have as humans in comparison to systems like ChatGPT. If the initial differences discerned in luck-reducing mechanisms dissolve upon further analysis, they do not indicate a fundamental difference between human and machine linguistic capacities.

This can be framed as a dilemma illustrating the importance of understanding linguistic luck-reducing mechanisms: either the diverse human luck-reduction mechanisms (causation, inference, intention) are reducible to the single process ChatGPT employs, or they are not. If they are not reducible, then further inquiry in this direction should reveal some deep difference between human and machine linguistic capacities. This would be a fruitful and important result, and may turn out to be a scientifically powerful tool to understand how human language is irreducible to statistics and computer power.

“Unlike the diverse sources of linguistic luck reduction in humans, ChatGPT seems to be a ‘one-trick pony’.”

However, if the full range of human luck-reducing mechanisms turn out to be the workings of a single formal/syntactic mechanism used by LLMs, then human luck reduction is ultimately explainable as just so much ChatGPT-style luck reduction. If humans had the computational power of the emerging LLMs, the remaining luck-reducing processes may be unnecessary. This would also be a fruitful and important result for understanding human linguistic capacities.

In either case, reducible or not, inquiry linking luck reduction, LLMs, and human linguistic systems is fruitful for understanding essential features of human language.

August 16, 2023

A few things at a glance

The comments on the most recent post (9 August 2023) have been many and interesting. I’ll return to them later, but in the meantime, I have received two queries. One dealt with the puzzling meaning of the verb to glance, and the other with the origin of the word tangle. I will answer them without delay, one at a time.

Glance “a quick look; to take a quick look” is familiar, but (this is what the question was about) how do we account for the senses that have nothing to do with looking? I am quoting examples from Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary of Current Englishby A. S. Hornby and others. This dictionary cannot be used as “a first English book for boys and girls whose mother-tongue (sic) is not English” (such was the title of Walter Ripman’s 1920 excellent book), but as a source of absolutely natural idiomatic usage and as an unobtrusive source of information warning foreigners of possible errors it probably has no equals. Quoting Hornby (but in American spelling): “The arrow glanced off his armor,” that is, “slipped or slid” (said of a weapon or a blow); a glance of spears in the sunlight “a sudden movement producing a flash of light.” The question I received from Japan was just about those seemingly secondary senses of glance in today’s English.

A glance at a cake glacé (a cake with an icing).

A glance at a cake glacé (a cake with an icing).By Brent Keane via Pexels, public domain

The OED allows us to trace the history of glance. No citations precede the fifteenth century. The basic meaning was (and is) “to move rapidly,” and of course, that is what a glance is: a quick look! Yet some doubt remains: aren’t glance “flash” and “a quick look” different words? The situation calls for an explanation of the etymology of the verb. The earliest recorded forms of glance are glench, glence, and glanch, which resemble the once current glent and even launch. Their origin is far from transparent. They may be loanwords from French. Old French glacier “to slide” (from glace “ice”) does look like a member of this family.

Questions come up at every step. Glacier and glance ~ glence ~ glanch can be looked upon as related if we succeed in accounting for n in the middle of the word. This we can do, for the so-called intrusive n is not an uncommon phenomenon in language history. Some anthologized examples are English message versus messenger, English nightingale versus German Nachitgal, and English farthingale “hooped petticoat” versus the Romance forms without n. Scottish ballant “ballad” belongs here too. Conversely, the family names Hutchinson and Robinson have variants without n in the second syllable. It is hard to account for the emergence of such nasals, but they are not exceptions, because regional variants like sumple “supple” occur all over the English-speaking world. Similar cases are also known from the history of Old Germanic: sometimes n is lost, and sometimes it is added. For example, the case of stand ~ stood has been discussed in all historical grammars (this type of variation is also common elsewhere in Indo-European). Returning to semantics, we observe that though ice is described as sparkling, glance refers to a flash. A tie between them does not look improbable.

A furtive glance.

A furtive glance.By Monstera via Pexels, public domain

As mentioned above, in the etymology of glance, launch has also been pressed into service. Launch is related to lance, and the names of weapons, we will remember, figure prominently in the definition of glance. But here, we run into initial g, which we don’t need. Sometimes this g- is a remnant of the old prefix ga- ~ gi- ~ ge-, as in German glauben “to believe” (compare the roots of g-lauben and be-lieve, along with g-leich “similar” and like, G-lück “good fortune” and luck, and so forth). But if glance is a relatively late word of Romance origin, the scenario that depends on the presence of an old Germanic prefix looks uninviting, unless we assume that in the past, the Old French verb glinser was a borrowing from German. Indeed, Old French ganchier was seemingly taken over from Germanic, and therefore, glance may indeed have emerged as a product of several forms in contact.

Regrettably, all such hypotheses leave us where we were at the beginning: no one doubts that Germanic, including Middle English, did have several forms resembling those of Old French. To complicate matters, in the Germanic group itself, a few English and Scandinavian verbs sounded alike. Consequently, the source of glance will remain uncertain even if we ignore Old French. For comparison, the verb glint “to give out a small flash of light” is believed to be of Swedish origin. The great German etymologist Friedrich Kluge called (rashly, as it seems) glance a loanword from Scandinavian. Walter W. Skeat looked on glint as a nasalized form of glitter. In similar fashion, he called glance a nasalized form of Old French glacer ~ glacier “to glide, slip, glance,” though in this case, he admitted the influence of Middle English glenten.

The picture resembles an image of worms in a heap or a knot of snakes: a few English, German, and Scandinavian verbs resemble one another and similar-sounding verbs in (Old) French. If someone wants a more dignified metaphor, interdigitation springs to mind. The words that interest us here may begin with g- or with gl-, have a, e, or i or conversely, in, en, or an in the middle. It is hard to decide where to begin and where to stop. For instance, glance is traditionally compared with glint but not with glimpse or glimmer. Also, Russian gliadet’ “to look” (stress on the second syllable) and its numerous Slavic cognates turn up in most works that deal with glance. No wonder that dictionaries end up saying that the origin of glance is unknown or uncertain.

Unfortunately, arrows don’t always glance off the target.

Unfortunately, arrows don’t always glance off the target.St. Sebastian by Andrea Mantegna via Wikimedia Commons, public domain

A few respectable sources reconstruct the ancient (that is, Indo-European) root gel– or ghel-. Given the picture presented above, attempts to discover such a root hold out minimal promise, while an opinion that glance is a product of several words influencing one another (hence the multitude of senses!) may be correct. In a recent post on flout and flaunt (2 August 2023), I discussed the role of initial fl- in sound-symbolic English words. Gl– is a similar element. Next to glance, we have gleam, glitter, glint, glow (with its offspring glower), glaze (a derivative of glass), and Old Icelandic glámr “moon,” obviously a shining object (its English cognate is gloaming “twilight”). Gl– suggests light and unsteady movement, but not all is gold that glitters, and as usual in such cases, there is no law. At best, we are dealing with a pan-human tendency. A century ago, Wilhelm Oehl, a scholar to whom I often refer in this blog, studied this tendency in great detail, though sometimes with excessive zeal.

Since no such “symbolic” group is tied to its meaning, a good deal of etymology of the words mentioned above remains guesswork. Did Latin gladius “sword” make people think of gleaming steel? Perhaps it did. Is this the etymology of gladius? English glad once meant “bright, shining.” But next to glad and gleam, we have glean, gloom, and glum. Etymologists like strict linguistic algebra. Unfortunately, words are capricious creatures and obey many rules. I was pleased to discover that Elmar Sebold, the editor of Kluge’s German etymological dictionary, a serious student of Indo-European, gave up the idea of reducing words like German Glanz “sheen” to an ancient root and explained them as sound-symbolic formations. In this respect, glance resembles Glanz, a nearly rootless word living up to its sound form. If someone attacks me for this amateurish conclusion, all spears will glance off my armored body.

Featured image: “Rødefjord, Northeast Greenland National Park” by GRID-Arendal, via Flickr (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

August 15, 2023

Putting positive planning into telemedicine projects

Putting positive planning into telemedicine projects

A new implementation tool helps practitioners design and build better bespoke remote healthcare programmes.While the face-to-face consultation will never be replaced, online and phone-based healthcare is here to stay—even more so after the global COVID-19 pandemic that catalysed remote diagnosis. But designing successful telemedicine projects is notoriously complex with most initiatives failing during the founding stages.

In an article in the journal Oxford Open Digital Health, Neha Verma and colleagues present a new easy-to-use chart-based checklist tool—Telemedicine Program Design Canvas (TPDC)—that brings clarity and a logical checklist approach to the process.

The TPDC allows doctors and healthcare workers to construct a programme that identifies strengths and likely pitfalls that can be adapted to suit patients and the wider community. To make sure it could be used in a variety of settings, the tool was developed over six mammoth 16- to 20-hour workshops, using healthcare stakeholders from three government organisations and three non-profit organisations.

From the sessions, the researchers identified 14 key elements that need to be addressed when designing a new programme: the problem, ecosystem, patients, patient journey, patient engagement and trust, providers, provider training, provider engagement, channels, technology, medicines and diagnostics, desired outcomes, and costs and revenues.

Process for the peopleThese 14 elements can then be grouped to guide conversations about implementation. For example, consider the problem and the ecosystem together. Is the community mainly urban or rural? In many low- and middle-income countries, rural phone and internet access may be limited so provision would need to be made to enable patients to participate in the programme.

Next comes the patients, patient journey, and patient engagement and trust: what particular strengths can be drawn on and what have patients been saying about their needs or previous programmes?

After patients, consider the providers: are they specialists or generalists, and what can be done in terms of provider training and engagement?

“The TPDC allows doctors and healthcare workers to construct a programme that can be adapted to suit patients and the community.”

With the patient and provider relationship examined, the TPDC looks to the medium and channels of communication. Which modes are most appropriate: web, apps, chat bots, or video? And how is the core technology in terms of software and hardware going to work reliably?

Finally, the tool looks at how tech and provider combine to deliver the diagnostics and treatments offered to patients. It also considers the desired outcomes because clear goal setting orientates the entire telehealth project. The very last step is to balance outcomes and treatment against overall costs and revenues.

Putting the process into practiceThe authors tested the new tool in two projects in rural India. The Visilant project used the TPDC tool to help achieve its aim to increase eye care to vulnerable populations through teleophthalmology. The MyTeleDoc project used the tool to help with its work connecting community health officers in government-run rural primary care clinics with specialists at secondary and tertiary health facilities.

The TPDC tool enabled each project to focus on their strengths and identify weaknesses, resulting in a more formulaic and less ad hoc approach to planning.

While the process is far from finished this is not the end of the conversation, as the article authors note. Many more projects will be needed to evaluate the efficacy of this approach.

However, with such a high failure rate for current remote healthcare projects there is a bridge to build between design and implementation of telehealth interventions, particularly for low and middle-income countries where people lack immediate access to onsite healthcare facilities. Providing a robust framework for the holistic design of such interventions, the TPDC is well-placed to help bridge this gap, enabling better comprehensive and iterative remote healthcare programme planning.

For more from Oxford Open Digital Health, check out our selection of scicomms content supporting our journal authors in spreading the word about their research.

Featured image by Karolina Grabowska (public domain)

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers