Oxford University Press's Blog, page 41

October 17, 2023

Human rights are not a “luxury belief”: why Suella Braverman’s rhetoric is dangerously misguided

Human rights are not a “luxury belief”: why Suella Braverman’s rhetoric is dangerously misguided

In a chilling moment in the middle of her speech to the recent Conservative Party conference, the current Home Secretary, Suella Braverman, made a pronouncement that, even by the standards of contemporary political rhetoric, was shocking in its implication. Human rights, the Home Secretary declared, are a “luxury belief.” In one sense, some such declaration has been a long time coming. Building on a decade of policies designed to produce a Hostile Environment for so called “illegal migration,” and in line with ongoing attempts to dismantle the Human Rights Act, the 2023 Illegal Migration Act is itself a thoroughgoing refusal of the obligations of human rights. As the UNHCR has repeatedly pointed out, by criminalising so-called irregular asylum claims (claims made by people fleeing perilous situations who seek refuge within the UK), the British government has reneged on commitments enshrined in the 1951 Refugee Convention. Even so, and even though the UK government’s attack on human rights has been sustained and systematic, the Home Secretary’s pronouncement is a shocking step, fundamentally wrong as a reading of history, and deeply disturbing in the future it anticipates.

Let’s start with the word “luxury.” Luxury, we might ask, for whom? When the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was formulated in the period immediately following the Second World War, it was in direct response to the genocidal acts of the Nazi regime. The Holocaust required a set of commitments on the part of the international community that would seek to prevent such acts of inhumanity happening again. The Declaration was not in itself a guarantee—no form of words is a guarantee—but it was a recognition that certain political rights must be acknowledged if people are not to be expelled from the human community. The 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees was a practical elaboration of the Declaration. It stated in material terms the obligations that political states owe people, as humans, in the event that those people are forced to leave their homelands.

“It could not be more wrong to call human rights a ‘luxury belief.’ To say so is both historically offensive and politically dangerous.”

The purpose of the Convention, in other words, building on the Declaration, was to ensure that no individual would be forced outside the human community, that everybody would be protected, as the Convention put it, against expulsion. It could not be more wrong, therefore, to call human rights a “luxury belief.” To say so, even to come up with such a phrase, is both historically offensive and politically dangerous. Human rights are the means by which the international community commits to protecting the most vulnerable. To abandon such rights is to abandon humans.

Braverman’s phraseology may or may not stick. As a populist politician stoking the culture war, she is prepared to risk increasingly perilous formulations to establish the divisions on which populism depends. Some of the phrasing will land, some won’t. What she wants her audience to take away, however, is the view that whereas we, by which she means the West, could once afford human rights, now, in some way that is not specified, those rights are not sustainable. Implicit in this claim, under-developed as it is, is an historical comparison, a comparison from which Braverman should have the humility to learn.

The 1951 Refugee Convention was a “visionary” document. As Terje Einarsen puts it, in his history of the drafting of the text:

It was decided to start the work of a general convention for the protection of refugees and stateless persons. The international spirit had changed and was significantly more visionary than before.

We need to hear the force of that word “visionary.” Like the authors of the Declaration, the authors of the Convention set out to envision a geopolitics from which no person would be expelled. In the genocidal crimes of the Second World War, and in the phenomenon of mass displacement that followed, they were witness to what expulsion from the human community meant and were therefore resolved to formulate principles that would ensure fundamental protections. The 1951 Convention, in other words, was a profound act of political imagination, a way of re-drawing geopolitical relations that sought to underpin a different relation between individuals and nation states. Human vulnerability, the document asserted, cut across the exclusions of borders. It constituted a recognisable human demand which states had a responsibility to meet.

“Post-war writings against expulsion remind us repeatedly what is at stake.”

The stakes of the game Suella Braverman is playing could hardly be higher, but just possibly her appalling rhetoric will have a clarifying effect. What her offensively complacent phraseology reminds us is that we must recall the moment of the inception of human rights; we must remember that they constituted that rare formulation, a necessary imaginary, a means of envisaging the world that addresses the world’s most urgent questions. Authors of all kinds understood this impulse and so, as one reaches back, one finds post-war writings against expulsion across a range of disciplines, writings that constitute the context in which the Universal Declaration and its related international instruments emerged. What one finds in those writings are the developing historical implications of the document, as human rights became a means of anti-racist struggle elsewhere, not least, as Frantz Fanon understood, in de-colonizing contexts.

As I write, I am leaving another conference, the Labour Party conference, where the organisation I work with, Refugee Tales, has held an event. Fringe meetings have been deeply serious in their engagement with Braverman’s remarks, shocked by the mainstreaming of far-right sentiment that such remarks represent. There is a clear understanding among activists that human rights constituted a geopolitical response to fascism and that it is the weight of that historical reality that must always determine the commitment to the obligations such rights impose. Whether the urgency of fringe discussions comes to inform policy-makers’ thinking remains to be seen. What Braverman’s remarks must cause us to recall, however, as post-war authors looking forward desperately wanted people to understand, is that human rights were and are crucial in ensuring an anti-fascist future. Post-war writings against expulsion remind us repeatedly what is at stake.

October 16, 2023

Tuning in to the cosmic symphony: restarting LIGO

Tuning in to the cosmic symphony: restarting LIGO

In 2015 history was made when LIGO (Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory) detected the first ever gravitational wave signal. This was an incredible technological achievement and the beginning of a completely new way of investigating the cosmos.

The collision of two massive objects shakes the fabric of space, making it ring like a bell and producing ripples that travel unhindered through space. For several decades astronomers and physicists worked on the construction of LIGO with the goal of detecting these ripples. LIGO is the most sensitive instrument ever devised. It consists of two laboratories, one located in Hanford, Washington, and the other in Livingston, Louisiana. Each houses an L-shaped interferometer whose arms extend for 4 kilometres (2.5 miles). Within these arms, a powerful laser beam travels back and forth, bouncing between mirrors before recombining to form an interference pattern. As a gravitational wave passes by, the fabric of space is pulled and pushed and this alters the distance between the mirrors and these tiny disturbances change the interference pattern. LIGO’s sensitivity is truly astonishing. It can detect changes in distance of around one billionth of the size of an atom. Having two observatories is important; like listening in stereo, it helps to determine the direction from which the waves arrive. It also ensures that a signal came from deep space and not a local disturbance.

“LIGO has provided the most direct evidence that we have for black holes and their properties.”

By comparing the data captured by LIGO to computer models, physicists can determine how each gravitational wave signal was created. It is possible to deduce the masses of the colliding bodies, the rate at which they were spinning, the energy released in the collision and how far away they are. LIGO’s first signal arrived from the collision and merger of two black holes located around 1.3 billion light years away. In the subsequent five years, LIGO received close to one hundred signals. Almost all of them came from collisions between pairs of black holes. The most epic was the collision and merger of black holes with 85 and 66 times the mass of the Sun that produced a black hole of 142 solar masses. During this collision, a mind-boggling nine solar masses were converted into pure energy in the form of gravitational waves.

In 2017, the Italian gravitational wave observatory Virgo also achieved the exquisite sensitivity necessary for the detection of gravitational waves and joined the LIGO observatories in their quest for distant cosmic dramas. Later that year on 17 August one of the most spectacular duly arrived. This event, named GW170817, was the first detected signal to come from the merger of two neutron stars rather than two black holes. Neutron stars are bizarre objects formed from the collapsed cores of stars that have run out of nuclear fuel. They are just 20 kilometres in diameter but contain at least one and a half times the mass of the Sun. In many ways they are like gigantic atomic nuclei. This was the first time and, so far, the only time that the source of a gravitational wave signal has been located with optical instruments, heralding the dawn of multi-messenger astronomy. The combination of optical and gravitational data has greatly advanced our understanding of what happens when two neutron stars collide. It is like being able to both see the lightning and hear the thunderclap. These observations lent support to the idea that many of the heavier chemical elements such as gold are created and dispersed in neutron star collisions.

“LIGO offers wonderful new tests of our best theory of gravity, Einstein’s theory of general relativity.”

In 2020, LIGO’s operations were suspended to allow for a major upgrade of the system. Now, after a three-year hiatus, LIGO is back up and running. On 24 May LIGO started a new observing run with refined instruments. With its enhanced sensitivity, it is expected to detect a gravitational wave signal every two to three days. LIGO is the lynchpin of the LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA collaboration—a partnership with the world’s other two gravitational wave observatories: Virgo in Italy and KAGRA in Japan. The construction of a third LIGO detector in India has also recently been approved. This expansion of the global network of gravitational wave observatories will help to pinpoint the location of gravitational wave sources so that they can also be studied optically.

LIGO has provided the most direct evidence that we have for black holes and their properties, and offers wonderful new tests of our best theory of gravity, Einstein’s theory of general relativity. By observing and studying the mergers of black holes and neutron stars, scientists are gaining new insights into fundamental physics, the nature of gravity, and the evolution of the universe itself. The restart of LIGO and the global gravitational wave research network launches a new phase of deep space exploration. We can look forward to more incredible discoveries in the near future.

October 15, 2023

Should animals have the right to vote?

Should animals have the right to vote?

Many countries have adopted legislation that protects the interests of animals to some extent—see, for example, the 2006 Animal Welfare Act in England, or the 1966 Animal Welfare Act and the 1973 Endangered Species Act in the US. These laws ordinarily ban animal cruelty and place various restrictions on people’s treatment of animals.

That is all well and good. But suppose we went one step further. Suppose it were suggested that animals’ interests would be even better protected if we recognized a right of political participation to animals. One way to do that would be to have human representatives cast votes on behalf of animals with respect to different legislative proposals. Thus, monkeys, parrots, and other creatures in the Amazonian forests in Brazil would have a say in the adoption or rejection of laws impacting their environment. Pigs, cows, and chickens on animal farms would have a say on laws related to their life conditions. This proposal would elevate animals to the status of actual actors in the political process. Right now, animals are merely subjects of our legal protection, but they don’t get to directly influence their own welfare. Under the proposal just stated, animals would have more direct control over their lives.

“Animals’ interests would be even better protected if we recognized a right of political participation to animals.”

But hold on. Why bother with political rights? Wouldn’t we achieve the same results by just doing more of the same of what we are already doing? More and better laws protecting animal welfare, more coverage for more species, etc. That should take care of all the animal protection we want, right? Perhaps. Nonetheless, there are a couple of things to be said in favor of the voting scheme. First, animal voting may relate not only to the right of animals not to be harmed (which arguably could be protected by laws against harm to animals). Animal voting might take place along dimensions that are captured better by a voting system, than merely by laws for the protection of animals. For example, some candidates in an election might propose laws offering a mandatory minimum food quantity for certain categories of animals, say rabbits. Similarly, a candidate could promise shelter to various species (e.g., subsidizing farmers to build more sheds for horses and cows). In those cases, the animals’ vote would go to those candidates. There is a large variety of such policies that could be proposed and implemented, and they would be better left to the electoral process rather than political theorists or politicians coming up ex ante with a list of laws concerning all these possible proposals.

Second, the voting system proposal, once people get accustomed to seeing past its initial bizarreness, may actually gain more traction in the real world of politics than categorical legal proposals for the protection of animal interests. The voting proposal is actually more modest than a purported law mandating the elimination of all harm to animals. Consider the following analogy: arguing for the adoption of a law banning guns entirely, or for a law banning abortion completely, is a stronger claim than submitting gun policy or abortion to a democratic vote. In the same way, in arguing that animals should have a voice regarding their rights, the burden of proof is not as high as in arguing directly that animals should be subject to no harm whatsoever, or that they are entitled to sufficient food or shelter (and that therefore laws should be passed protecting these rights). The end result of each argument may end up being the same, for example laws may be passed protecting animals from harm or providing them with food and shelter. But getting there in the indirect manner (through voting for candidates who support animal-oriented policies), given the significant size of conservative (in outlook, rather than political affiliation) constituencies everywhere, should be more acceptable in public debate today, and thus the safer way to go.

“A voting scheme for animals may provide just the right amount of novelty and provocation to jilt politicians and policymakers out of their apathy.”

Third, indirect protection of animals through legislation has made significant advances, but the general track-record of this approach remains dismal. Animals are still being slaughtered by the dozens of billions every year (you read that right; check out the live Animal Kill Clock in the US) and turned into food (generating huge amounts of unnecessary waste in the process). By this standard, the effects of laws banning animal cruelty and protecting endangered species dwindle almost to insignificance. It doesn’t look like things are getting anywhere like this. So why not try something new? And a voting scheme for animals may provide just the right amount of novelty and provocation to jilt politicians and policymakers out of their apathy.

Of course, one may point out that, if animals have fundamental rights, those rights should be unassailable, not subject to the vagaries of voting. So, it would be absurd to subject such fundamental rights as the right to be free from pain, or the right not to be killed, to voting; as if, should the winning candidate happen to be hostile to animals, the fact that animals had a say in the vote would make it all right to kill animals or make them suffer. This observation is correct, but, at least with respect to fundamental rights, a scheme of animal voting may be seen as only one step in the right direction, i.e., that of protecting animal interests. It is not a solution that guarantees that animal rights will be protected. Given the almost universal indifference to animal suffering and the size of the animal-based food industry, an animal voting system would be better than nothing.

October 13, 2023

Test your knowledge of Gothic literature!

Test your knowledge of Gothic literature!

Do you know your Shelley from your Poe? Have you read everything the Brontes wrote? Think you are an afficionado of Gothic literature? Take this quiz to see how well you really know your castles, ghosts, and scary stories.

Which of these eighteenth-century Gothic novels was published earliest?The Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole The Mysteries of Udolpho by Ann RadcliffeVathek by William Beckford The Castle of Wolfenbach by Eliza Parsons In which of Edgar Allan Poe’s works does the narrator hear a “rapping, rapping at my chamber door”?"The Cask of Amontillado" (1846) "The Tell Tale Heart" (1843) "The Raven" (1845) "The Masque of the Red Death" (1842) What is the name of Maxim de Winter’s family home in Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca (1939)?Hill HouseLimmeridge HouseThornfield HallManderleyWhich Gothic short story features a tax collector who is haunted by spirits whilst staying in an abandoned palace?"The Lady of the House of Love" (1979) by Angela Carter "The Hungry Stones" (1920) by Rabindranath Tagore"The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" (1820) by Washington Irving "The Lovely House" (1950) by Shirley Jackson In Northanger Abbey (1818), Jane Austen’s witty parody of the Gothic genre, which Gothic novel does Mr Thorpe describe as “tolerably decent”?The Monk (1796) by Matthew Lewis The Mysteries of Udolpho (1874) by Ann Radcliffe Horrid Mysteries (1796) by Carl Gosse Camilla (1796) by Frances Burney In Cold Comfort Farm (1932) by Stella Gibbons, which character is sent mad by “something nasty in the woodshed”?Seth StarkadderAda DoomFlora PostMeriam BeetleWhich of these contemporary Gothic novels tells the story of Mr Rochester’s first wife?Our Share of the Night (2022) by Mariana Enriquez The Woman in Black (1983) by Susan Hill Wide Sargasso Sea (1966) by Jean Rhys The Little Stranger (2009) by Sarah Waters In Wuthering Heights (1847) by Emily Bronte, Catherine describes her love for Linton as like “the foliage in the woods”.To what does she compare her love for Heathcliff?"The roaring, rapid waves” “The eternal rocks beneath” “The silver of the waning moon” "The ever-growing moorland” Who wrote The Vampyre (1819)?Mary ShelleyLord ByronPercy ShelleyJohn PolidoriWhich Gothic novel closes with this line:“He was soon borne away by the waves and lost in darkness and distance.”The Turn of the Screw (1898) by Henry James Frankenstein: or, the Modern Prometheus (1819) by Mary ShelleyDracula (1897) by Bram Stoker Vivir Abajo (2019) by Gustavo Faveró PatriauIf you’d like to see more fun activities, as well as keep up to date with Oxford University Press products and offers, why not follow @OUPLibraries, where we share quizzes, industry insights, and product news?

Open access and the academic community: a librarian’s view

Open access and the academic community: a librarian’s view

The Bibsam Consortium is an association of Swedish universities which negotiates licence agreements for electronic information resources. Headed by the National Library of Sweden, it currently has 95 member organizations. Oxford University Press has had a Read and Publish agreement with the Consortium since 2019.

We asked Henrik Schmidt, Licence Manager from the Research Collaboration Unit at the National Library of Sweden, for his views on open access and the transformation of the research environment.

How has the transition to open access changed the nature of your role as a consortium manager?The movement towards open access has changed the focus from reading use to publishing activities. This also means that the target group for the consortium’s work has partly changed. The publishing researcher has become an important and fully “visible” target group. In addition, the institutions’ (universities, university colleges, as well as public agencies and research institutes) management and research departments are more involved compared to the past when the university libraries (or equivalent) were alone in dealing with these issues.

How has open access changed what your consortium does as a service provider within its community?As a Licence Manager at a consortium, my job is to present to participating institutions, and take care of administration relating to any agreements which the consortium concludes with publishers and producers. The services requested have changed as a result of open access. Publication analyses are becoming increasingly important. This also means discussions are needed over how the costs of an agreement should be distributed within the consortium, where a distribution model based on publication is now being implemented.

What are the wider benefits, from your perspective, of a more open research environment?Open access is important for all of society. When research results quickly become available, more people can validate and build on previous results. Research is not only conducted at universities, but also in business, industry, and the public sector, where there is also a great need for open access.

The National Library of Sweden and all the universities and university colleges in Sweden have a mandate from the Government that we should work towards 100% open access. Currently, we have around 80% open access to Swedish research articles. For Swedish researchers, open access is becoming standard. For them, it is obvious that all publications should be open access. It is part of their academic life.

What challenges has open access presented to you as a consortium manager?As an administrator for a consortium, the challenge is partly to keep up with rapid changes and partly to seek new ways to conclude and finance agreements. New pricing models and legal principles need to be implemented in the next generation of contracts.

What would you like to see happen in the future, as open access transforms the way research is communicated, accessed, digested, and used?Alongside transformative agreements we need to consider other paths towards open access, both in terms of constructing new agreements based on publishing as a service (to replace the transformative agreements) and other alternative ways of publishing academic results, for example on platforms like ORE (Open Research Europe).

It is also of vital importance that publishers significantly increase the pace of converting journals to fully open access journals, known as “journal flipping.” There are indications which show that flipped journals have higher visitor numbers, that their acceptance and impact remain the same, and that their publication output increases.

How do you perceive your future role in that transformation?Try to keep up! Try to contribute to the national goal which states that scholarly publications resulting from research financed with public funds must be published with immediate open access. And by 2026 (at the latest), this will also include research data.

Featured image by geralt on Pixabay (public domain)

October 11, 2023

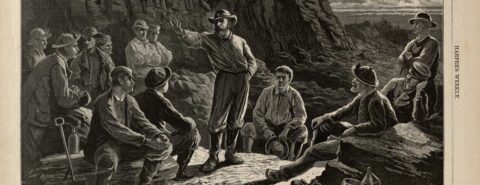

Making sense of the Molly Maguires today

Making sense of the Molly Maguires today

Twenty Irish mine workers were hanged in the anthracite region of Pennsylvania in the 1870s, convicted of a series of murders organized under the cover of a secret society called the Molly Maguires. Hostile contemporaries described the Molly Maguires as inherently savage Irish immigrants who had imported a violent conspiratorial organization into industrial America. Challenges to this nativist myth produced a counter-myth casting the Molly Maguires as innocent victims of economic, religious, or ethnic oppression. Neither interpretation makes historical sense.

In October 2023, Oxford University Press published a twenty-fifth anniversary edition of Kevin Kenny’s Making Sense of the Molly Maguires. Who were the Molly Maguires, what did they do, and why did they do it? Why did contemporaries describe them in such hostile ways? And what does the subject tell us about the history of immigration and labor in the United States? Here Professor Kenny discusses 10 things that helped him answer the questions at the heart of his book.

1. The Molly Maguires left almost no evidence of their ownOther than two letters, one of them a fragment, no direct evidence survives from the Molly Maguires themselves. Almost everything that is known about them takes the form of hostile, often exaggerated, descriptions by their enemies. How, then, can a historian hope to write their history?

First, I read everything that was written about the Molly Maguires in the nineteenth century and since. Then, I used census records and government reports to determine the class structure of the anthracite region, in particular the different kinds of work performed by different ethnic groups, with British immigrants dominating the skilled positions in the mines and Irish immigrants providing most of the unskilled labor. In these ways, I began to make sense of the Molly Maguires—not only how they were portrayed by others, but also who they were, and why they acted as they did. The pattern of violence in Pennsylvania, moreover, strikingly resembled a pattern of violence I had already encountered in my study of Irish rural history.

2. The Molly Maguires were a transatlantic outgrowth of a distinctive Irish rural traditionThe Molly Maguires first emerged in Ireland in the 1840s and 1850s, the last in a long line of rural secret societies that included the “Whiteboys,” the “Oakboys,” the “Ribbonmen,” and the “Lady Clares.” The men who joined these organizations wore female clothing as a form of disguise and pledged their allegiance to a mythical woman who symbolized their struggle against landlords who raised rents, evicted tenants, or enclosed common land.

3. The Molly Maguires embodied an archaic form of labor protest in industrial AmericaIn an industrial capitalist economy, trade union leaders negotiate with employers to raise wages and improve working conditions, and they can bring production to a standstill by calling a strike. The Molly Maguires took a more direct approach. If a mine operator treated Irish workers unfairly by paying them less for the same work, or by reserving the best jobs for British workers, they delivered a verbal warning. If he did not listen, they nailed a sheet of paper to his door with a coffin sketched on it and the words “this will be yours.” This coffin notice might be followed by a beating. The ultimate sanction was assassination.

4. The labor movement in the Pennsylvania anthracite country took two overlapping forms“Making sense of the Molly Maguires means trying to understand why, under certain conditions, desperate people resort to violence.”

Organized in the anthracite region in 1868 and open to all mine workers regardless of national origin, religion, or skill, the Workingmen’s Benevolent Association (WBA) mobilized 35,000 men into one big union. Its leaders were Irish-born. But some of the most alienated members of the workforce, known to history as the Molly Maguires, favored direct violent action instead.

5. The trade union movement condemned violence on moral and tactical groundsThe union leaders insisted that violence was morally wrong and that it would provoke a backlash against the labor movement. Franklin B. Gowen, the president of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, targeted the labor movement as a whole by claiming that the Molly Maguires were the terrorist arm of the WBA and, by destroying both institutions, secured monopoly control over the production and distribution of coal in the lower anthracite region.

6. The Molly Maguires became outcasts from their own communityMany of the men convicted as Molly Maguires came to Pennsylvania from the remote northwest county of Donegal. Unlike most Irish immigrants at this time, they spoke Irish as their first language. The alleged ringleaders of the conspiracy were mostly former mine workers who, like their counterparts in rural Ireland, operated taverns. Culturally marginalized to begin with, the Molly Maguires were eventually disowned by the twin pillars of their own ethnic community—the trade union and the Catholic Church—for their secrecy and violence.

7. The Molly Maguires were not depraved killers, but neither were they figments of the nativist or anti-labor imaginationTwenty Molly Maguires died on the scaffold, but 16 other men—mine owners, superintendents, bosses, workers, and public officials—were killed as well. The men who killed them operated within local branches of an Irish fraternal organization called the Ancient Order of Hibernians. In the context of intense anti-Irish prejudice and a protracted conflict between labor and capital in the Gilded Age, contemporaries greatly exaggerated the threat to American society posed by the Molly Maguires. They never existed as the vast conspiracy imagined by their enemies, but they did kill people.

8. Violence was the norm in the mining country, not the exception“Historical inquiry requires empathy… but empathy is not the same as sympathy: to explain a historical phenomenon is not to justify it.”

The Pinkerton Detective agency sent one of their agents, James McParlan, to work undercover in the anthracite region, posing as a miner. McParlan was almost certainly an agent provocateur. Other Pinkerton agents conducted a fatal vigilante attack on a family suspected of harboring Molly Maguires. Together with the Coal and Iron Police—a private force operated by the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad—the Pinkertons arrested 50 suspected Molly Maguires and delivered them to the authorities for trial. Based largely on McParlan’s evidence, the state of Pennsylvania deployed its control over legitimate violence to execute 20 men.

9. Explanation is not justificationMaking sense of the Molly Maguires means trying to understand why, under certain conditions, desperate people resort to violence. Historical inquiry requires empathy, an attempt to see the world from the perspective of others. But empathy is not the same as sympathy: to explain a historical phenomenon is not to justify it. This distinction makes for good classroom discussions in teaching other violent episodes in American labor and immigration history as well, including the Haymarket Affair of 1886 and the Sacco and Vanzetti case of the 1920s.

10. Labor remains central to immigration, and to immigration history, todayIn the 25 years since the publication of Making Sense of the Molly Maguires, industrial work and trade unionism have become less prominent in the field of labor history. Immigration history has moved in exciting new directions, covering a much wider range of groups and periods. The tragic events in Pennsylvania in the 1870s were unique in several respects. But the main themes in Making Sense of the Molly Maguires—class, labor organizing, ethnicity, religion, nativism, and history from below—remain central to any understanding of immigration in the past and in the present.

Feature image: “The Strike in the Coal Mines – Meeting of Molly Maguires.” From Harper’s Weekly, January 31, 1874. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

October 10, 2023

Embracing a sustainable open access future: removing barriers to publishing

Embracing a sustainable open access future: removing barriers to publishing

In the ever-evolving landscape of academic publishing, Oxford University Press (OUP) is committed to working towards a sustainable open access (OA) future. Our vision is clear: to make trusted, high-quality research accessible to everyone while striving to eliminate as many barriers to publishing as possible. However, we also recognize that the road to achieving this goal is paved with challenges. In this blog post, we explore how we are addressing some of these challenges and share some information on the volume of articles we waive Article Processing Charges (APCs) for each year.

OA publishing has revolutionized the dissemination of knowledge, enabling research to reach a wider and more diverse audience. However, as OA publishing has grown, so too have discussions about its sustainability and accessibility. While the OA model offers free access to readers, it does not eliminate the costs associated with the publication process. To sustain the high quality of our journals and uphold rigorous editorial standards, most of our gold OA journals rely on APCs. These charges, though necessary, can pose a barrier for some authors, particularly those without access to research funding. The availability of funding varies greatly across research disciplines, countries, and institutions. These imbalances can result in some authors struggling to cover APCs.

In addressing the issue of publishing barriers, it’s important to recognize that these challenges have their origins prior to the advent of OA publishing. Historically, some journals charged page and colour charges to cover the additional costs of longer articles or printing in colour. While subscription journals were free to publish in (notwithstanding the charges mentioned above), the subscription fee itself created barriers to access. These longstanding issues have, in many ways, shaped the landscape of scholarly publishing.

“Our vision is clear: to make trusted, high-quality research accessible to everyone.”

As we work to eliminate contemporary barriers, we must also acknowledge and learn from the past. We want to foster a publishing environment where these historical impediments are addressed alongside the challenges posed by the shift to OA. One crucial facet of our strategy involves negotiating transformative agreements with institutions and national consortia. These agreements centralise the payment of OA publishing fees, removing the financial burden from individual authors and ensuring access to quality research. Additionally, OUP publishes a range of diamond OA journals where sponsoring organisations cover the costs of OA, again removing the need for APCs, and further enhancing accessibility.

Another mechanism we use to remove barriers to publishing in our fully OA journals is a variety of different APC waivers. Waivers are an imperfect solution to a complicated problem but do enable us to ensure that authors who cannot afford to pay APCs can still publish OA.

1. Discretionary Waivers: We recognize that not all authors have access to funding for APCs. We offer waivers to authors in this situation, ensuring that research can be published irrespective of an author’s financial circumstances.

2. Waivers for authors in low and middle-income countries: We are acutely aware of the disparities in research funding between countries. To address this, we automatically grant waivers to corresponding authors based at institutions in more than 100 low and middle-income countries.

3. Editorial Waivers: Journal editors offer waivers to authors whose work is commissioned for a specific issue or to mark an occasion, recognising the importance of their contributions to the academic community.

“Between 2021 and 2022, over 3,800 papers in OUP’s fully OA journals had their APCs waived, around 15% of the total publishing in those journals.”

It is understandable that authors may feel uncomfortable requesting financial assistance to publish their work. Where possible we have sought to remove the need for the request (such as our automated waivers for authors based in low and middle-income countries) or limited the amount of information authors need to provide when requesting a waiver. We also work hard to ensure that all waiver requests are independent of the peer review process so authors can be assured that the assessment of their work is not contingent on their ability to pay an APC.

Even with these mitigating steps in place, we recognize there is more to do, both in simplifying the waiver process, and in expanding our other collective and diamond approaches to OA. We will continue to work to improve our approach, including through participating in cross-publishing initiatives such as the Open Access Scholarly Publishing Association’s workshops on equitable OA and Research 4 Life’s OA Taskforce.

Transformative agreements, diamond OA approaches, and waiver programmes form a holistic approach that underscores our dedication to fostering an inclusive, accessible, and sustainable OA publishing landscape. As a not-for-profit, society publisher furthering the transformation to OA, we are committed to playing our part in fostering change and ensuring equitable access to OA publishing for all.

We welcome feedback and suggestions from our authors, readers, and partners to refine and improve our approach. Together, we can build a more inclusive and sustainable future for academic research.

Featured image by Hans via Pixabay (public domain)

Supporting researchers at every career stage

Supporting researchers at every career stage

Academia is a complex ecosystem with researchers at various stages of their careers striving to make meaningful contributions to their fields. In support of furthering knowledge, academic journals work with researchers to disseminate findings, engage with the scholarly community, and share academic advances.

Oxford University Press (OUP) publishes more than 500 high-quality trusted journals, two-thirds of which are published in partnership with societies, organizations, or institutions. The remaining third is a list of journals owned and operated by the Press. Fundamental to this list of owned journals is our mission to create world-class academic and educational resources and make them available as widely as possible, including expanding our fully open access options for authors. As a not-for-profit university press, our financial surplus is reinvested for the purpose of educational and scholarly objectives of the University and the Press, thereby fostering the continued growth of open access initiatives and supporting the scholarly community.

How do we support researchers in different career stages through our journals?Early Career Researchers: nurturing talentFor early career researchers (ECRs), having their work published in a reputable journal is a crucial step in establishing their academic reputation. OUP journals provide several avenues of support including:

Mentoring and guidance: Some journals provide mentorship programs or editorial support to help young researchers navigate the publishing process. Featuring Oxford Open Immunology and Oxford Open Energy:

Two of our Oxford Open series journals, Oxford Open Immunology and Oxford Open Energy run dedicated ECR boards, which provide a key channel for direct engagement between ECR participants and our high profile academic senior editorial teams. Activities are planned throughout the year and may include assisting with facilitating journal webinars, joining ECR board meetings to discuss journal strategy and direction, suggesting and coordinating special collections or commissioned pieces on highly topical areas of research.

Open access initiatives: 120 of the journals we publish are fully open access and the vast majority of the remaining journals offer authors open access options, making research freely available for a global audience to read, share, cite, and reuse. This helps early career researchers, and researchers of all stages in their career, gain visibility of their work and reach a wider readership. Featuring our Oxford Open series:

The Oxford Open series is underpinned by a set of guiding principles, which include an emphasis on open research, with each journal having been developed in a bespoke way to best serve the needs of its own research community.

Hear more about OUP’s approach to OA published and the Oxford Open series in The Oxford Comment podcast.

Many of our Oxford Open journals offer article types that are specifically developed for ECRs to start their publication journey, these may take the form of a Rapid Report, Short Communication, or Perspective article, for example. We regularly invite ECRs to submit their work to the journal, often in collaboration with their mentors or supervisors as appropriate.

Mid-career researchers: advancing expertiseAs researchers progress in their careers, they require journals that can help them deepen their expertise and broaden their impact. OUP journals provide several avenues of support including:

Cutting-edge research: OUP journals prioritise publishing high-impact, innovative research, allowing mid-career researchers to stay updated with the latest advancements in their fields. Featuring Exposome:

Exposome is the home of cutting-edge research from the emerging field of exposomics. The journal sits at the systematic intersections of environmental science, toxicology, chemistry, and public health and policy, and it calls on daring science from a broad community of investigators to provide a forum for engagement, redefine our understanding of the human exposome, and critically advance the field.

Editorial and reviewer roles: Many researchers at this stage are invited to serve as peer reviewers or editorial board members to further contribute their knowledge to the academic community and enhance their own expertise. Featuring STEM CELLS Translational Medicine:Editor-in-Chief Gary W Miller outlines the need for this new field in the inaugural editorial.

For over 10 years, STEM CELLS Translational Medicine has served as a home for timely and important research to advance the utilization of cells for clinical therapy. The journal’s peer reviewers play a critical role in ensuring that the research published in the journal serves the needs of this research community by helping move applications of these critical investigations closer to accepted best patient practices and ultimately improve outcomes.

STEM CELLS Translational Medicine is proud to work with mid-career researchers, and reviewers of all career stages and encourages researchers to join the journal’s network of expert peer reviewers where researchers can get a first-hand look at the quality of research that is required and preview cutting-edge scientific work that helps them stay atop their field.

Established researchers: global recognitionFor established researchers, maintaining a high level of visibility and recognition in the academic world is paramount. OUP journals provide several avenues of support including:

Prestige and impact in the field: OUP journals are known for their prestige and rankings in their relevant fields. Publishing in our journals can bolster an established researcher’s reputation. Featuring Nucleic Acids Research:

For almost 50 years, Nucleic Acids Research (NAR) has provided the scientific community with detailed and constructive editorial feedback resulting in publications of the very highest standard. The quality of content has been demonstrated in this year’s Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, which cited this article from NAR as one of three publications fundamental to the research recognized by the award.

Edited by a fully independent team of leading academic researchers, the journal serves as a beacon of trusted and high-quality research in a rapidly advancing field. Having flipped to fully OA in 2005, NAR has opened the doors to rigorous, impactful research, sharing knowledge globally and it remains at the cutting edge of molecular biology science.

Leadership opportunities: As a partner to academic research, all of OUP’s journals are edited by members of the academic community, longstanding experts in their own fields. Our journals therefore offer established researchers the opportunity to take on leadership roles within journal editorial boards as associate editors or editors-in-chief, helping to shape the direction of the journal and their fields. Featuring Oxford Open Neuroscience:

Oxford Open Neuroscience is run by a representative group of five active scientists who are subject specialists, rather than a single editor-in-chief. Representing the needs of that community and making science-based decisions, the journal’s senior editors act as ambassadors for their individual fields.

As a researcher-led publication with a focus on diversity, transparency and innovation, Oxford Open Neuroscience is a fully open access alternative to more traditional neuroscience journals and enables researchers themselves to propel the field into a new publishing era.

OUP’s owned journals are more than just platforms for publishing research, they are invaluable partners in the academic journey of researchers at every career stage. From nurturing early career talent to supporting mid-career researchers in advancing their expertise and providing global recognition for established scholars, our journals contribute to the growth and success of the academic community. As the world of research continues to evolve, our journals will remain dedicated to supporting researchers around the world, ensuring knowledge is disseminated, shared, and celebrated.

October 9, 2023

On Shakespeare’s “illiteracy”

No greater honor could have been conferred upon Shakespeare than the one he received in 1623: the publication of his plays in the monumental folio format associated with the great works of the ancient past. The volume’s very durability assumed the lasting value of its content. Like the classics, Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories & Tragedies was meant to live on. And yet one small phrase in the most lavishly praising of the verse eulogies throws the project into doubt. In “To the Memory of . . . Mr. William Shakespeare,” Ben Jonson mentions, as if in passing, that Shakespeare had “small Latin and less Greek.” The detail seems amiss. Why drop a language barrier between Shakespeare and the ancients, especially in the very sentence invoking the ancient tragedians who wrote in those languages: Aeschylus, Euripides, Sophocles, and Seneca? With only minimal knowledge of Greek and Latin, how could Shakespeare have studied the ancient models that were at the heart of any vernacular attempt to rival them?

There could be no doubt about the classical status of the 1623 Folio’s precedent: Jonson’s own 1616 folio, The Works of Benjamin Jonson. His mastery of the tongues was unquestionable, as was his imitation of the works in those tongues. The affiliation of his opera to the classical tradition was emblazoned on his folio’s title page: a triumphal arch with allegorical figures, classical architectural elements, and Latin mottos. The content was organized into several genres, each with a classical counterpart. To Jonson, the conferral of the dignity of the folio on Shakespeare’s plays must have seemed a travesty. His plays might have merited the fleeting applause of the popular stage or circulation in ephemeral quarto pamphlets; but not the everlasting fame of publication in folio.

Yet Jonson was not the only contemporary to target Shakespeare’s scant learning. In what is assumed to be the earliest reference to Shakespeare, Robert Greene warns three fellow scholars of “an upstart Crow” (a raucous countryside bird, the bane of farmers) who beautifies his wings by plucking the pennings (penne, quills or feathers) of others. Greene here may be objecting not to Shakespeare’s practice of lifting from the writing of his betters but to his lack of the credentials that would entitle him to do so. (Greene, of humble rearing, might have been similarly stigmatized, if not for his Cambridge degrees.)

Among playwrights, Shakespeare was an anomaly: all of his contemporaries had either matriculated at Cambridge or Oxford or, like Kyd and Jonson himself, had the private education that was a close equivalent. In a verse letter addressed to Jonson, Francis Beaumont, an Oxford matriculant as well as Jonson’s pupil, feigning untutored modesty, likens his style first to that of a Devon cheese-maker and then to Shakespeare’s:

heere, I would lett slip

(If I had any in me) schollershipp,

And from all learninge leave these lines as cleare

As Shakespeares best are.

In this jibe, even Shakespeare’s best lines lack scholarship.

Shakespeare may himself have made a joke of his unlearning. Both As You Like It and Merry Wives of Windsor feature an academically challenged character who is repeatedly called William. In the former, the stock country bumpkin is mocked by the court fool: to Touchstone’s question “Is thy name William?” he replies “William, sir”; and to Touchstone’s rhetorical follow-up, “Art thou learned?” he answers an earnest, “No, sir.” In Merry Wives of Windsor, an entire scene focuses on an underperforming schoolboy who bungles through his Latin declensions as his exasperated school master calls him to attention 10 times by name.

If Shakespeare was widely identified as undereducated, might the designers of his funeral monument have been faced with the same challenge as the compilers of his bibliographic monument? Perhaps they, too, felt the need to cover up his low-level education. John Aubrey, who saw the Stratford monument as early as 1640, noted that Shakespeare’s statue, quill and paper in hand, wore the academic robes of his own alma mater of Oxford University.

In every biographical notice of the next century, Shakespeare’s limited education is his salient feature. Thomas Fuller comments, “Indeed his Learning was very little”; Edward Phillips echoes his assessment, “probably [Shakespeare’s] Learning was not extraordinary.” Aubrey is slightly more positive: Shakespeare “understood Latine pretty well,” at least well enough, Aubrey speculates, to have taught it, albeit in the provinces, as “a Schoolmaster in the Countrey.” But in an anecdote circulating around the same time, his learning hits rock bottom. Shakespeare, the story goes, on the occasion of the christening of his godchild, Ben Jonson’s son, presents him with the christening gift of a dozen spoons inscribed with Latin mottos; he tasks Jonson with their translation, though the inscriptions must have been simple, at the level of a child’s first words in Latin: Fides or Deo Gratias.

In the eighteenth century, the folio volume in which Shakespeare’s plays were published in 1623, 1632, 1664, and 1685 breaks into serial volumes. Yet the aim is still to promote Shakespeare as an English classic. In the first of the multi-volumed editions, Nicholas Rowe’s 1709 The Works of Mr. William Shakespear, the same classicizing engraving reproduced on the frontispiece of all six volumes makes its purpose clear: Shakespeare is being laureated by togaed figures of Comedy and Tragedy, with trumpeting Fame aloft, and shady Ignorance underfoot.

Frontispiece to all six volumes of

The Works of Mr. William Shakespear

, 6 vols., ed. Nicholas Rowe (1709)

Frontispiece to all six volumes of

The Works of Mr. William Shakespear

, 6 vols., ed. Nicholas Rowe (1709)Yet in the edition’s prefatory Life, Rowe returns to Jonson’s meager appraisal, inventing an incident to account for it: his father withdrew him from the local grammar school and could thereafter give him no “better education” that of his own wool-dealing trade. Rowe later finds a match for his “small Latin” in Titus Andronicus: “about that of one of the Gothick princes,” the loutish youth who recognizes a Latin quote from Horace familiar to any Elizabethan schoolboy. But Rowe finds abundant evidence of the same lack in the dramatic writing itself: its routine neglect of the dramatic unities, its preference of character over plot, its unregulated or undisciplined style. In a supplementary seventh volume to Rowe’s edition, the critic and dramatist Charles Gildon measures each of Shakespeare’s plays and poems against ancient works of the same genre, believing Shakespeare’s learning had been underestimated, while allowing that had it been greater, so, too, would his works have been.

In the preface to his 1765 edition of Shakespeare, Samuel Johnson looks back on Shakespeare’s reception: “There has always prevailed a tradition, that Shakespeare wanted learning, that he had no regular education, nor much skill in the dead languages.” But that tradition was nearing its end. Two years later, Richard Farmer published An Essay on Shakespeare’s Learning demonstrating that Shakespeare had not needed Greek or Latin: he acquired learning of the ancients through translation. Yet would Jonson have thought it possible to imitate the ancients in English or in any of the continental vernaculars? Would translations retain the form, rhetoric, and style of the originals? But by 1800, the question was moot. The imitation of the ancients was no longer essential to literary composition as genius, originality, and experience came to rule the day.

October 7, 2023

Why does government policy ignore scientific evidence? Experts and the public must act together

Why does government policy ignore scientific evidence? Experts and the public must act together

July 2023 was the hottest month ever measured in human history. Scientists have warned of the dangers of climate change for decades. And yet, the political systems in Western societies respond inadequately: public discussion has only really picked up speed when various groups of protesters, such as Fridays for Future or Extinction Rebellion, started organizing rallies and blocking bridges. Steps taken to reform our energy provision, our transport systems, and our agricultural practices seem painfully slow. Why is it that even the best available evidence, gathered by thousands of scientists using a broad range of methods, is not taken up by politics?

One answer is to blame citizens: maybe they are insufficiently informed or care more about their private lives than learning about political issues. If one understands the situation in this way, it may become tempting to look for non-democratic solutions: maybe we need technocratic experts to take over?

But this account is too simple, and it puts the blame in the wrong place. The relation between expert communities and society at large does not take place in a vacuum, but in a field marred by vested interest. For if policies change, this creates winners and losers—and potential losers have an interest in the status quo remaining in place. One strategy they can choose is to accept the facts and openly fight for their interests. But often, these potential losers choose another strategy: undermine the public dissemination of the facts that would suggest that change is needed.

“The relation between expert communities and society at large does not take place in a vacuum, but in a field marred by vested interest.”

The most famous instance of such a strategy has been the “tobacco strategy” that cigarette producers used when a scientific consensus built up showing the harmfulness of smoking. For decades, they threw doubt on the soundness of these studies, funded alternative lines of research, and did everything to make the science look uncertain. Similar strategies have also been used by other industries, including the oil and gas industries. With their deep pockets, these industries could support climate change denialism and thus delay political action. Instead of blaming ordinary citizens for not knowing enough about climate change, it is these activities that need to be called out and stopped.

Does this mean that distortion by private interests is the only problem in the relation between expert knowledge and citizens? Even without it, there remain challenges. Expert knowledge is, by definition, unequally distributed, whereas democracy, as a form of governance and way of life, is built on a foundation of moral equality. And yet, also among moral equals we need to recognize that a climate scientist who spent decades studying shifts in ocean temperature, or an indigenous farmer who intimately knows the changes in the biosphere caused by shifting rainfall patterns, know more about these things than many other individuals.

“Together, expert communities and the society at large need to manage the interfaces between the production of specialized knowledge and its use in wider political discourse.”

In Citizen Knowledge: Markets, Experts, and the Infrastructure of Democracy, I argue that communities of experts and the broader democratic public have a joint responsibility to deal with this tension in the best possible way. Together, they need to create conditions in which citizens can trust the expertise of others and thus benefit from the division of cognitive labor. Expert communities need to have space to explore facts according to the logic of the knowledge area in which they work—without, for example, impossible pressures to raise funding from no-matter-what source. They need to make sure that they allow for internal diversity in doing so, because this is the best bet to prevent blind spots and distorted perspectives. If they discover facts that are relevant of society, they need to make those public, but democratic societies also need to provide infrastructures, such as science journalism, that facilitate this task. Together, expert communities and the society at large need to manage the interfaces between the production of specialized knowledge and its use in wider political discourse. This concerns structural questions such as the composition of scientific advisory boards. But it also concerns ethical questions for each and every expert, for example not to “epistemically trespass” by claiming authority for utterances that do not fall into one’s own area of expertise.

By creating more awareness about the risks of knowledge being abused, democratic societies can counter the dangers that stem from private interests, but also the risk of undermining democratic values by giving experts too much authority. Ultimately, it is elected politicians that have the legitimacy to take decisions. But in a complex world of divided labor, the knowledge of very different expert communities is needed to make good policy. And while democratic politics will always have to navigate conflicts of values and interests—that’s what it is for, after all—some of the problems that concern the production and transmission of expert knowledge can and should be addressed better, through institutional design and professional ethics.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers