Oxford University Press's Blog, page 44

September 11, 2023

Making psychology a reflexive human science

Making psychology a reflexive human science

As the thousand flowers of psychological research bloom in the fields of popular understanding, we ought to reflect upon the nature of the explanations our field proffers.

The model of the rational computable subject leaves out much that makes us human. For one it does not adequately convey the relation between culture and biology. It is time we admit the insufficiency of the positivist project; we should not tie our hopes of explanation too tightly to the experimental paradigms we develop to operationalize prevalent metaphors of mind (Koch, 1999; Danziger, 2008).

Joseph Henrich’s reflections on the cultural context of empirical research further suggest that the majority of our findings reflect a very small WEIRD sample of the human population. Lack of context obscures the significance and meaning of research results. Empirical psychology ought to foreground historical and cultural context so that in addition to deriving descriptive principles of mechanism, psychologists can discursively approach the phenomena as part of our broader cultural projects.

Drawing from historical and anthropological forms of analysis will allow psychology to better encapsulate how the mind emerges from and reflects back onto its particular cultural context.

History and context can expand empirical psychologyAn interdisciplinary psychology must posit explanation at multiple levels, from description of the mechanics of receptor function to the discursive space of identity. Mixing these distinct layers of explanation would allow the mind sciences to express the phenomenological reality of the contextual setting of individual minds. Anthropology is designed to secure such stories and will help us describe what epistemic use psychology fulfills in a given locale. For example, psychology is used in the West to assess pathology and provide therapeutic interventions for mental suffering.

“It is time we admit the insufficiency of the positivist project.”

If tradition is the self-encounter of the human mind, horizon is the vantage point of knowing the relative significance of a finite position. History then allows for a broader understanding of the reflexive links between knowledge and practice. As Gadamer (2004) surmised, we understand the horizon of the questions we ask by regaining concepts from the past in a way that includes our own comprehension of them. Deployment of psychology in concordance with an historical anthropology enriches our understanding of the symbolic sphere we inhabit. According to Roger Smith (2019: 17), “Historical knowledge contributes narrative, and the understanding of narrative is fundamental to the notion of being human; human self-knowledge and action are mutually constitutive, or, belief changes a person and what a person does changes belief.”

We also know from history that many causes are best characterized as chaotic or through complexity theory due uncertainty, the interdependency of variables, and the contingent nature of agency (Gaddis, 2002). The historical method of developing narratives seems to be crucial to our imaginative appraisals of truth and knowledge and should be considered in its own regard as a shaping influence upon the nature of belief and explanation in psychology. Observation, imaginative sense-making, and perspective-taking are themselves sources of knowledge rather than artifacts in the scientific process (Osbeck, 2019).

Models should allow for variability, design limitations, and failure rates. Heuristics should be understood as pragmatic applications that we substitute for deductive knowledge (Wimsatt, 1976). Our theories should be so robust and valid that failure of replication does not threaten the foundation of the field. To counteract these crises, psychologists can develop familiarity with levels of analysis above and below the brain and the person. In this way, we can develop generative models which are open to inter-field integration.

“Making psychology a more reflexive human science would bestow a sense of scope and context.”

It is time empirical psychology adds historical and anthropological methodology so that in addition to descriptive principles of mechanism and verificationism a new generation of psychologists will approach the mind with a view to more discursive, contextualized, and empathetic explanation. Some community psychology is already moving in this direction, but we also need laboratory and theoretical research to adopt this approach. Making psychology a more reflexive human science would bestow a sense of scope and context and allow for more effective communication with humanists and natural scientists.

Exciting frontier work that integrates types of explanation are being undertaken in the study of affect, pain management, and the gut-brain axis. Such work expands and investigates the embeddedness and multilevel integration of mind and body. Focusing on such phenomena has the potential to unify subjective/mental and objective/material aspects of mind because it concerns the precise relations between bodily mechanisms and enculturated conscious experience. Using anthropology, we can see healing as the pragmatic goal of such work in the historical context of a shift from dualism to monism. Through a more thorough understanding of our mythological frames, we can better understand the motivations of the unique form of shared understanding that is psychological explanation.

September 9, 2023

The turn to domestic accountability in the shadow of international criminal tribunals

The turn to domestic accountability in the shadow of international criminal tribunals

On 21 July, the Special Criminal Court in the Central African Republic concluded its first trial, with three suspects convicted of war crimes and crimes against humanity. A few weeks earlier, Ukrainian investigators launched a war crimes and ecocide investigation into the attack on the Khakovka dam, while dozens of other cases weave their way through the national justice system. On the other side of the Atlantic, Colombia’s Special Jurisdiction for Peace contemplates how to address hundreds of crimes committed during South America’s longest civil war.

What do these three examples spanning three continents have in common? Although they stem from different geo-political contexts of criminality, the proliferation of investigations and trials across Africa, Europe, and the Americas speak to the growing importance of domestic accountability for serious crimes, especially war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide. While international justice is still reflexively associated with high-profile international cases, for instance Vladimir Putin’s recent arrest warrant at the International Criminal Court (ICC), most defendants are now prosecuted by national institutions. In fact, even in countries like Ukraine or Colombia, the ICC plays mainly a backup role, with only two to three trials in The Hague at any given time, in stark contrast to the hundreds of cases prosecuted by the former criminal tribunals for Rwanda or the former Yugoslavia.

How did domestic accountability come to eclipse the dream of international criminal tribunals? And what effects does this shift from international to domestic trials have on the global fight against impunity? To answer these questions, my book, International Criminal Tribunals and Domestic Accountability: In The Court’s Shadow, examines the causes, rationales and, consequences of what it calls the complementarity turn—a paradigm shift toward national trials as the ultima ratio or end goal of international criminal justice. Just 25 years after the adoption of the ICC’s founding treaty, domestic justice is celebrated as quicker, cheaper, and more attuned to victims’ needs than proceedings in the far-away courtrooms of The Hague. Many even argue that “the future of international criminal justice is domestic.” And yet, while a sophisticated literature now exists on international criminal tribunals’ shortcomings, scholars are only beginning to study what a turn to domestic accountability means for societies in the midst of violence, emerging from conflict, or confronting a legacy of past abuses. Given international criminal law’s short history, many accountability debates, including about how international and national justice relate to one another, still revolve around assumptions and conventional wisdom.

“The pursuit of accountability for serious crimes is a complex, context-specific multi-actor process, and no one should expect ‘quick fixes.'”

By drawing on three case studies—Rwanda, Sierra Leone and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC)—my book contributes to this growing body of socio-legal scholarship that moves beyond assumptions to analyze what has and has not worked in in specific countries. By comparing how three different international criminal tribunals interacted with domestic justice processes (in addition to the ICC in the DRC, I examine the work of the Special Court for Sierra Leone and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda), I assessed the extent to which the three tribunals’ different institutional designs conditioned relations with state officials and civil society in three countries, and ultimately what kind of “shadow effect” the tribunals had on state actors’ ability and willingness to launch genuine and fair prosecutions of serious crimes at the national level.

The findings confirm that the pursuit of accountability for serious crimes is a complex, context-specific multi-actor process, and no one should expect “quick fixes,” silver bullets, or “optimal” institutional design “solutions to impossible problems.” However, beyond context-specificity, the book draws attention to cross-cutting patterns and how the language of complementarity—a neologism derived from the ICC’s institutional design—has come to shape accountability efforts in the DRC, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, as well as a dozen other countries mentioned in the book. While the ICC’s institutional design vis-à-vis states, known colloquially as complementarity, was expected to spur domestic accountability efforts—setting the ICC apart from other tribunals—20 years of practice has confounded these expectations. Similar to other international criminal tribunals, domestic accountability efforts in countries under the ICC’s jurisdiction have varied considerably, with hundreds of domestic prosecutions in the DRC or Colombia standing in stark contrast to the quasi-absence of national trials in Georgia or Uganda. Although geopolitical realities and social expectations partly explain these divergent national responses, the book draws on the experiences of Sierra Leone, Rwanda and the DRC to suggest that international and national accountability stakeholders, especially donors and NGOs, increasingly prioritize (consensual) capacity-building programs for national magistrates and attorneys while avoiding the political dimensions of state-led justice efforts, including (contentious) questions about who gets selected for domestic prosecution, on what charges, or the fairness of ensuing trials. In questioning the ICC’s dominant interpretation of its jurisdictional powers, I warn that, even in best case scenarios, the Court’s engagement with states may produce “unintended diversionary complementarity,” or selective national prosecutions of lower-ranking suspects and less controversial crimes. Another way of putting this is that, instead of incentivizing—by casting a shadow over domestic accountability efforts—a genuine and fair reckoning with the most serious crimes, ICC interventions may result in selective national prosecutions that entrench the ruling political elite’s power.

“This is an invitation to scholars and civil society to reflect more critically on the rationales and consequences of the much-celebrated complementarity turn.”

In identifying a potential “authoritarian effect” of state-centric domestic accountability initiatives in countries like the DRC and Rwanda, the book raises further questions about the “romanticization” of national responses to atrocity crimes and whether an overly optimistic emphasis on domestic trials qua ultima ratio of the international criminal justice project may promote illiberal tendencies in some contexts. Not only is the book an appeal to other scholars to study whether similar dynamics of “unintended diversionary complementarity” can be observed elsewhere, I identify factors that impede domestic accountability initiatives as well as forward-looking strategies that can enable a balanced approach by the ICC vis-à-vis its national counterparts, for instance greater civil society engagement, prosecutorial cooperation, and trial monitoring.

However, beyond strategies and institutional design tweaks geared to more dynamic ICC-national relations, my stock-taking of major trends in international criminal justice since the 1990s is an invitation to scholars and civil society to reflect more critically on the rationales and consequences of the much-celebrated complementarity turn, including the cliché that “the future of international criminal justice is domestic.” Although it started after my book was finished, Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine and ongoing accountability debates over the respective roles of domestic, international, and hybrid trials suggest that a relational evaluation of the merits and drawbacks of both international and national accountability initiatives will require further study.

Featured image by Michal Vrba via Unsplash, public domain

September 8, 2023

Illuminations and enlightenment throughout the history of the Middle East [reading list]

Illuminations and enlightenment throughout the history of the Middle East [reading list]

Explore the vast history of the Middle East and immerse yourself in the stories of the luminaries, leaders, moments, and the movements that shaped the intellectual and cultural landscape for the centuries that followed.

Each of the seven books on this reading list—spanning hundreds of miles geographically and thousands of years chronologically—sheds a contemporary light on the pursuit of knowledge and spirit of curiosity that continues to inspire the region and the world.

1. The Genius of Their AgeThe Genius of Their Age by S. Frederick Starr is a vibrant portrait of an age when Arabic enlightenment anticipated and inspired the European Renaissance, illuminated by its guiding figures, Ibn Sina and Biruni.

A thousand years ago, these two intellectual giants and rivals made ground-breaking strides in fields as diverse as medicine, astronomy, mathematics, philosophy, geography, and physics. Biruni measured the earth more precisely than anyone else down to the sixteenth century, and Ibn Sina’s impressive repertoire of medical knowledge became the standard for the next 600 years in Europe, the Middle East, and India, and these achievements just barely scrape the surface of a much larger story. Ibn Sina and Biruni both lived and worked in what is now Uzbekistan in the tenth century, and their work both reflected and propelled an era of rapid change.

Starr uses the lives and correspondences of these two brilliant thinkers to bring the age to life.

2. Peerless among PrincesBuy The Genius of Their Age by S. Frederick Starr

Under the sixteenth-century reign of Süleyman, the Ottoman Empire became a true global power. From Hungary to Iran, and from the Crimea to North Africa and the Indian Ocean, his domain was expansive, multilingual, and multireligious.

The wealth of his treasury, the strength of his armies, and his personality were much discussed by courtiers, diplomats, poets, and publics, making Süleyman an almost mythic figure during his life and through to the present day. His prolific poetic output, charity, and patronage of arts and architecture enhanced his reputation as a universal ruler with a well-rounded character. But who was the man behind the public façade of might and glory?

Peerless among Princes explores the true Süleyman. From his relationship with his overbearing father, to his loving marriage to a concubine named Hürrem, this book paints a compelling portrait of one of history’s most influential rulers.

3. King of the WorldBy Peerless among Princes by Kaya Şahin

King of the World takes readers back in time to the Persian Empire of the sixth century BC, the world’s first hyperpower, with the purpose of delving into the life of Cyrus the Great, who conquered most of the empire’s territory.

Cyrus was a legend in his own lifetime. His conquests of Media, Lydia, and Babylon earned him a reputation as one of the greatest conquerors in history. But he was equally well-regarded for his approaches to governance and leadership. During his reign, he instituted a policy of religious tolerance, implemented administrative reforms that increased the efficiency of the empire while also respecting regional customs and laws, and he invested in infrastructures that facilitated trade and communication throughout the empire.

King of the World by Matt Waters gives Cyrus’s legacy the recognition it is due and seeks to provide an accurate and approachable portrait of the great ruler’s life and achievements. Waters draws from a wide array of sources, both from the Ancient Greeks and primary evidence from the ancient Near East as well.

4. The MasnaviBuy King of the World by Matt Waters

If something else can capture your attention

Then it’s not love, but just a trivial passion –

Love is that flame which, once it blazes up,

Burns everything but the Beloved up.

Immerse yourself in the poetic beauty of Rumi’s magnum opus, the Masnavi, widely recognized as the greatest Sufi poem ever written, and dubbed by some “the Koran in Persian.” Composed for the benefit of his disciples in the Sufi order named after him, Rumi weaves entertaining stories and passionate verse to convey his message of divine love and unity.

The latest addition to this multi-book collection is the first ever translation of the entirety of Book Five. Previously, the poem had been deemed too provocative to publish in full and so only translations of select passages or in lineated prose were available.

5. A Short History of Islamic ThoughtBuy the Masnavi

While much has been written about Islam, particularly over the past 25 years, few books have explored the full range of the ideas that have defined the faith over a millennium and a half.

A Short History of Islamic Thought is a perfect book for general readers looking to expand their horizons. Tracing Islamic thought from its beginnings in the seventh century, this illuminating introduction to Islam explores the major ideas and figures—those who over the centuries have broached life’s major questions, from the nature of God and the existence of free will to gender relations and the ordering of society, and in the process defined Islam.

Above all, this book reveals the fundamental principles of Islamic thought, both as a source of inspiration for Muslims today and as illuminating and rewarding in their own right.

6. The Caliph and the Imam

Following the Prophet Muhammad’s death in 632 a struggle broke out among his followers regarding who would succeed him. Most argued that the leader of Islam should be elected by the community’s elite and rule as Caliph. They would later become the Sunnis. Others believed that Muhammad had designated his cousin and son-in-law Ali as his successor, and that henceforth Ali’s offspring should lead as Imams. They would become known as the Shia.

The Caliph and the Imam by Toby Matthiesen explores this rift and sheds light on the many ways it has shaped the Islamic world to this day.

7. Rivers of the Sultan

Dive into the fascinating histories of the Tigris and the Euphrates rivers in Rivers of the Sultan by Faisal Husain. Running through the heart of the Middle East and merging in the area of Mesopotamia known as the “cradle of civilization,” these two bodies of water experienced a rare period of political stability and integration during the sixteenth century.

Under the rule of Sultan Süleyman I, the management of the system was unified and centralized to enable cooperation among the rivers’ dominant users and improve the exploitation of their waters for navigation and food production. Under this imperial policy, shipments of grain, metal, and timber from upstream areas of surplus in Anatolia were regularly sent to downstream areas of need in Iraq, thus rebalancing the natural resource disparity within the Tigris-Euphrates basin.

Placing these historic bodies of water at its center, Rivers of the Sultan reveals intimate bonds between state and society, metropole and periphery, and nature and culture in the early modern world.

September 7, 2023

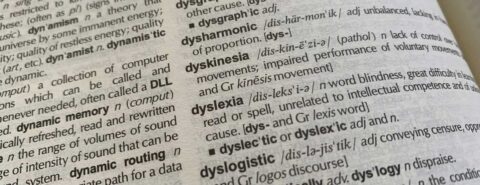

American English dialects: always changing, yet here to stay

American English dialects: always changing, yet here to stay

Are Americans in different parts of the country starting to talk more alike? It’s a reasonable question to ask. Americans have always been footloose, and now that working remotely is possible, they’re relocating to other regions more than ever. Americans watch the same television shows, listen to the same radio programs and podcasts, and converse on the same microblogs and message boards. Once new slang finds its way onto the Internet, it quickly nationalizes. Certain words and usages traditionally associated with one part of the country have started expanding their territory. For example, y’all, once used exclusively in the South, is starting to be heard in other places.

American English, like all languages, is made up of dialects. A dialect is a set of words, pronunciations, and sentence structures that connects its speakers to a particular region or social group. Dialect boundaries can never be rigid or exact. Not only do dialect regions always include an admixture of people from other places, but even speakers who were born in the area vary in which linguistic features they adopt (if any). The way people talk depends on many factors besides where they grew up, such as age, gender, social status, education, and ethnicity.

“A dialect is a set of words, pronunciations, and sentence structures that connects its speakers to a particular region or social group.”

In spite of these complicating factors, distinctive regional dialects are still alive and well in the United States. Starting in the mid-twentieth century, several projects have recorded American regional speech, including the Linguistic Atlas, the University of Pennsylvania Telsur (telephone survey), and the Yale Grammatical Diversity Project. Interviewers for these projects often had to speak to several people before finding someone native to the place. Nonetheless, clear regional patterns emerged, each with a unique constellation of words, pronunciations, and usages. Remarkably, the regions that make up the present-day dialect map of the United States are essentially the same ones that were in place by the time of the American Revolution.

American dialects got their start with the four major groups who colonized British North America during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Each brought their own way of talking. The Puritans, who began arriving in Massachusetts in 1629, came mainly from East Anglia in the southeast of England. The Cavaliers, aristocrats who settled in Virginia during the second half of the seventeenth century, were mostly from areas of southern England to the south and west of London. The Quakers, who settled Pennsylvania between 1675 and 1715, were more geographically mixed, but most came from the North Midlands. The final rush of colonists, arriving between 1717 and 1775, migrated from the border regions of Scotland and northern England, plus northern Ireland, and settled in western Pennsylvania and the Appalachian backcountry.

As these early colonists and their descendants spread out across the continent, they tended to move directly west. Their settlement patterns are reflected in the current dialect regions of the United States. These are the North, covering the northeastern states and the upper Midwest; the South, encompassing the southeastern states and the inland South as far west as Texas; the Midland, which includes the strip of states between the North and the South, from Pennsylvania to the Rocky Mountains; and the West, which runs approximately from the Rockies to the Pacific Ocean. The West represents a new dialect area. People from everywhere flooded into that region during the nineteenth century and no single dialect gained a dominant hold.

“British regional dialects are the foundation on which American speech was built, and traces of these original speech patterns still exist.”

It would be a vast oversimplification to say that modern American dialects are the direct descendants of British regional dialects, but they are the foundation on which American speech was built, and traces of these original speech patterns still exist. For instance, y’all and its variant you’uns came over with the Scots and Irish who settled western Pennsylvania and the mountainous backcountry of the South. They’ve been heard in these places since the early nineteenth century, and they are still heard in more or less the same areas today. In fact, the use of you’uns is one of the chief identifiers of natives of the western Pennsylvania city of Pittsburgh. (Pittsburghers spell it yinz.)

Other examples run through the language. Several southern terms can be traced to southern England, including disremember for forget; favor for resemble; traipse for walk in a straggling way; and like to meaning almost (I like to died). Pronunciations that until recently were typical of New England country folk, such as ‘deef” for deaf, ‘marcy’ for mercy, and ‘desate’ for deceit, arrived with the Puritans. The expressions want in and want out and the combination of need with a past participle (That needs washed) are likely contributions of immigrants from northern Ireland who settled the Midland in the eighteenth century.

What’s next for American English dialects? They’ll no doubt continue to evolve, as all languages do. For instance, a noticeable change in progress involves the pronunciation of word pairs like cot/caught, Don/dawn, and stock/stalk. Traditionally, speakers in the Southeast and the North say these words differently, producing the vowel sound of the first word with unrounded lips (like ah) and that of the second word with lips rounded (like aw). In other parts of the country, people typically pronounce both words of each pair the same way, with unrounded lips. Lately, the second pronunciation is spreading into some northern states and will probably become the most common one. Similar pronunciation changes are happening in other places too.

However, it’s unlikely that any of these changes will result in the merging or disappearance of regional variations. American dialect boundaries have stayed the same for a few centuries now, so they’ll likely continue to do so. New Englanders of today don’t talk the same way as New Englanders of fifty years ago, but they still sound different from Southerners, Midwesterners, and Californians.

Featured image by Nico Smit via Unsplash, public domain

September 6, 2023

An etymological stinkpo(s)t

Most of what I am going to say in this blog post can be found elsewhere, that is, in any good dictionary and partly online, but the conclusion will be, or so I hope, not entirely trivial. Besides, not everybody has access to my published database and a collection of etymological dictionaries in nine languages that grace the walls of my study, so that after all, the effort may be worth the trouble.

Today’s subject is the origin of the verb stink. Some people feel confused about the difference between stank and stunk. Let them consult a grammar book and be informed. The sequence is the same as in sink—sank—sunk and ring—rang—rung. Stink has always been a strong verb, that is, a verb, whose infinitive, past tense, and past participle display ablaut, or, to avoid this learned term, a series of alternating vowels. Unlike the illegitimate and ever-controversial sneak—snuck, stink has always been a strong verb. Always means that its conjugation has not changed since the Old English period and that its cognates in other related languages display the same system of alternating vowels. The oldest Germanic language whose long narrative texts have come down to us is Gothic. It was recorded in the fourth century, and a word like English stink and Dutch/German stinken surfaced in it several times. Surprisingly, it meant “to clash, to do battle,” and when it appeared with a prefix, the senses were “to stumble” and “to strike against,” while a related noun glossed Greek “obstacle” (the Gothic New Testament was translated from Greek). No reference to a bad smell!

A prototypical German stinker.

A prototypical German stinker.Illustration from Vinkhuijzen collection of military uniforms, via NYPL, public domain

If we look at the senses of all the attested Old Germanic cognates of stink, we will find “strike against; bounce, leap,” and the like, all of them referring to collision, sudden movement, running, and (not to be missed!) sprinkling. Apparently, stink progressed from “attacking” to “attacking with water, besprinkling” and “an attack of the air on the nostrils,” a tremendous change. In later texts, stincan (elsewhere spelled stinkan) has been recorded as meaning “to emit a smell; sniff” (a neutral odor) and (surprisingly) “to smell sweetly.” Today, its sweet odor is gone. The process known as the deterioration of meaning is common in the history of words. An anthologized example is silly, which has gone all the way from “happy” (compare German selig “blissful; blessed; happy”) to “foolish.” Those who have read the post for last week may remember that fond developed in the opposite direction: from “foolish” to “foolishly affectionate” and “loving” (predictably, this process is referred to as the amelioration of meaning). The related English noun stench also meant “odor” but changed it to “offensive smell” quite early.

Students always wonder why such changes are possible. The answer may sound disconcerting: “Because so many people speak a language.” Teachers, editors, and manuals keep reminding us that we misuse a certain word or grammatical form, but most people don’t care and persist in their folly. Once the smart educators die out, only those who ignore the strictures remain, “irregardless,” as it were, of the ire of their ancestors. Such is the mechanism of all language change. Obviously, in a search for the distant origin of stink, we should concentrate on such senses as “strike against, collide” and disregard the later connotations, even though they are the only ones we now remember.

Though the meaning of the recorded cognates is most important, in this case, we have no way of going beyond “spring, burst, run, flee, collide.” The story began with reference to a forceful movement. Such a verb, we suspect, must have been sound-imitative or sound-symbolic, but nothing in the complex st-nk or st-k alludes to any noise: br, tr, kr, and their likes are a different matter. Perhaps for this reason, all authorities agree that the etymology of stink is unknown. Naturally, the hypotheses on the verb’s origin have not been wanting. Most of them, as usual, concentrate on attempts to find related forms (cognates) of stink outside Germanic. And indeed, a few similar-sounding words in Baltic, Celtic, Sanskrit, Latin, and Greek are not too few.

From an etymological point of view, snoring is fine, while stinking is not.

From an etymological point of view, snoring is fine, while stinking is not.Photo by Nicky Wilkes, via Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

They all begin with st– (or t-, because one should reckon with the elusive prefix, known as s-mobile), may or may not have n in the middle, and display a variety of senses. Compare, for example, instigate and distinguish (in English, ultimately, from Latin). The possibility of the Germanic root of stink without initial s- and without n in the middle has been suggested more than once, but no promising conclusions have been reached along those lines. A few similar-sounding Sanskrit words for “pillar; stumble” and “trample, tread” exist. They too have been rejected as possible cognates. However, if the ancient ancestor of stink really meant “to drive a post into the ground,” we may at least conclude that the senses“collide; strike” were derived from some labor activity. This conclusion would be a step forward in our semantic reconstruction but not explain what made such a “quiet” sound group as st-k appear in the verb referring to a noisy activity. Crush, crash, creak, croak, cry, along with bump, thump, stamp, stomp; hiss, and hush live up to their sense, while stink does not.

Therefore, the origin of stink is doomed to remain a riddle, and we arrive at a somewhat unexpected conclusion. References to sound imitation (onomatopoeia) and sound symbolism (in my blog posts and in many others) may seem like cheap tricks on the part of language historians, but it is not. Enormous literature exists on the emergence of language. We may perhaps be allowed to ask a less general question: “Was language iconic in its inception?” Translated into easy terms: “Was there an indissoluble tie between sound and meaning in the first words?” There probably was, but the “first words” are millennia away from us, and we can only hope that impulses which motivated our distant ancestors can still be reconstructed and are the same today as “once upon a time.” In the Semitic languages, the sought-for link seems to be more apparent than in Indo-European, but in Indo-European, it is also evident. When we fail to discover that primordial tie or show that our word is a loan from another language, we stop, for there is a blind wall (more properly, a deaf wall) in front of us.

Silly but happy.

Silly but happy.Via Pxfuel, public domain

Our conclusion about stink is less than moderate, and I have chosen this word to show (not for the first time!) the meaning of the ever-recurring verdict: “Origin unknown.” Indeed, we have an Old Germanic verb that meant something like “to push forcefully forward; thrust; collide.” It probably sounded approximately like stinkwan. Similar words still exist in other Indo-European languages, but it remains unclear whether this similarity is a case of kinship or a coincidence. Even if their kinship happens to be recognized, our gain will be of minimal value, because the wall will grow in size but not become lower or easier to penetrate. The forceful sense of the verb does not correspond to its quiet sound.

You probably expect some self-evaluation of this post. I know what you want to say and agree. Yes, it stinks. But not every day is Sunday, or, to put it differently, an etymologist’s life is not beer and skittles.

Featured image via Pxfuel, public domain

September 5, 2023

Building copyright: an absurdist work in progress

Building copyright: an absurdist work in progress

Would you say that a(n actual) banana duct-taped to a wall may be protected by copyright? And would you consider a claim that the author of said duct-taped banana copied the work of another artist who had also duct-taped a (plastic) banana to a green cardboard an infringement of the copyright owned by said artist?

These questions are those that, recently, a court in the USA had to answer in the context of litigation that artist Joe Morford had brought against fellow artist Maurizio Cattelan. Morford claimed that Cattelan’s work titled Comedian infringed copyright in the former’s work Banana and Orange. In the end, the judge sided with Cattelan: while Morford’s Banana and Orange would enjoy some copyright protection, Comedian does not incorporate any protectable features of that work.

Not only is the Morford/Cattelan dispute nearly as “absurdist” as Cattelan’s Comedian (as stated by Cattelan himself) is meant to be but it does also illustrate the inherent ambiguity of copyright’s founding principles.

We know that copyright is an intellectual property (IP) right that protects works that are created by an author and are sufficiently original. Yet, nowhere in legislation is it defined what the very object of protection (a “work”) is, who is or what makes one an “author” in a legal sense, or what the concept of originality refers to.

Starting with “work,” international law merely describes what the expression “literary and artistic works” encompasses and hints at the fact that copyright only protects expressions of ideas and not ideas as such (the so called idea/expression dichotomy) when it refers to this notion as requiring a “production.” Like US law, EU and UK law are no more helpful in this regard: no definition is provided of “work.”

Something more is said in relation to “originality” and “authorship,” at least in EU legislation, though hardly anyone could consider such hints as being akin to a definition. So, originality under EU law (the same is still true for the UK too, as well as the USA) is considered fulfilled where the work at issue is “its author’s own intellectual creation.”

“Nowhere in legislation is it defined what the very object of protection (a ‘work’) is, who is or what makes one an ‘author’ in a legal sense, or what the concept of originality refers to.”

For authorship, nothing is specified regarding its foundational requirements, that is: what makes one an author. The only hints we may find relate to who may be regarded an author. For example, the Compendium of Practices of the US Copyright Office excludes that “works produced by a machine or mere mechanical process that operates randomly or automatically without any creative input or intervention from a human author” may be protected by copyright. Recently, for example, the US Copyright Office refused to register a work that was said to be entirely generated by Artificial Intelligence (AI); the decision has been however appealed and the appeal is pending). The situation is different under UK law, where the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act expressly provides that, for a work that is entirely computer-generated, the person who made the necessary arrangements is deemed to be the author. Insofar as the EU is concerned, it is not entirely clear if an “author” in a legal sense needs to be a natural person, though case law suggests indirectly that in most cases this likely needs to be the case to receive protection under copyright.

Indeed, while we may look in vain for statutory definitions of foundational principles of copyright protection, a lot of what copyright is and protects today stems from case law guidance developed over time.

If we consider the EU alone, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) has expressly provided definitions of key concepts like “work” and “originality.” The former has been defined in a case concerning the protectability of the taste of a spreadable cheese under copyright: a “work” is an expression that is “identifiable with sufficient precision and objectivity, even though that expression is not necessarily in permanent form.” Turning to originality, what is needed is that the intellectual creation at hand reflects “the author’s personality, which is the case if the author was able to express [their] creative abilities in the production of the work by making free and creative choices.”

In all this, two things are clear. The first is that this process of refinement is still underway, also considering the challenges that generative AI has been posing. The second is that it is precisely this fuzziness that has allowed a right like copyright, which regulates (and should stimulate) the production and dissemination of cultural objects and also serves as an instrument of technological governance, to maintain a central role. Without it, a system originally devised to regulate the circulation of printed books in the aftermath of Gutenberg’s revolutionary invention would have hardly survived, let alone thrived several centuries later.

So, yes, Cattelan’s “absurdist display of a banana duct-taped to a wall” showcases not only why copyright is—in all likelihood—the most delightful of all the IP rights but also how its own inherent absurdities are needed for its very livelihood… and liveliness.

Featured image: Matthew Feeney via Unsplash, public domain

September 4, 2023

Rising seas, eroding beaches, and fewer fish in Africa

Rising seas, eroding beaches, and fewer fish in Africa

Climate change has brought dangerous new threats to food production in West Africa. Crop farmers face disrupted rainfall and protracted drought, which are serious livelihood threats since most small farms have no irrigation. Yet coastal fishermen are now threatened as well, due to ocean warming and sea-level rise. West Africa’s traditional marine fishermen launch their 30-foot wooden canoes from broad beaches that are now rapidly eroding, which denies space to haul their nets ashore and leaves their fragile homes exposed to sudden storm surges. Meanwhile warmer sea temperatures have reduced their catch. The World Bank projects that by 2050, climate change alone could reduce Ghana’s potential fish catch by 25% or more. This will be a serious threat, since fish currently provide of total animal protein in the Ghanaian diet.

I am a food security expert who has often worked with traditional farmers in Africa, but until now not with coastal fishermen. My perspective was enriched this July when I joined a research team visiting coastal fishing communities in Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, and Nigeria. We saw shocking evidence of livelihood threats from rapid beach erosion everywhere, but the complaints we heard from the fishermen themselves went well beyond a changing climate.

“The World Bank projects that by 2050, climate change alone could reduce Ghana’s potential fish catch by 25% or more.”

Our research team—five from Harvard University and five from partner institutions in West Africa—spent three weeks travelling by van to visit more than a dozen different fishing communities along the Gulf of Guinea coast, using translators when necessary to overcome local language differences. We always explained our business in advance to community chiefs, the key arbiters in all dealings with outsiders. We visited first with fishermen engaged in net mending or boat repair and then spoke at length with community leaders, usually out of the sun in a covered meeting hall. Like traditional fishing communities everywhere (including the small lobster harbor I know on the coast of Maine), those we met took obvious pride in their hard work and distinctive way of life, but worried about looming changes beyond their control.

In all of these communities we saw evidence of damaging beach erosion. Shorelines in some places were moving inland by several meters a year. We visited the town of Keta, in eastern Ghana, where a storm surge in 2017 displaced more than 300 local inhabitants. All along the coast concrete block buildings were being toppled, undercut by the waves. We often found the remains of tarmac roads that were originally built well behind the beach but were now regularly under water. At one location near Accra, we interviewed two women standing in distress beside homes wrecked just two weeks earlier by a storm that came at high tide.

Homes wrecked by a storm at high tide near Accra.

Homes wrecked by a storm at high tide near Accra.Photo by Robert Paarlberg.

Some of this was damage from climate change, but not all. Local experts explained that a strong natural west-to-east current had been scraping sand from the beaches along the coast for at least the past century. This natural erosion was then worsened by human actions not connected to the climate, such as the building of hydro dams that stop river sediments from reaching the shore, and illegal “sand mining” from the beach to supply a booming construction industry needing concrete. Sand is also dredged offshore for fill, to turn coastal wetlands into marketable real estate. Jetties built to protect harbors and navigation channels trap sediment, accelerating erosion down the coast. Concrete sea walls (one known as “The Great Wall of Lagos”) are constructed to protect tourist hotels and other high-value real estate, but this only deflects the ravages of the sea onto unprotected areas nearby, including the fishing communities we visited.

Several other non-climate factors also threaten traditional fishing communities in West Africa. Small wooden canoes with outboard motors cannot hope to compete for fish with large diesel-powered trawlers equipped with fish-finding sonar, bigger nets, mechanized hauling devices, and chilled storage for the fish. On paper, the trawlers are officially restricted in what they can catch and where they can operate, but most of the fishermen we talked to complained loudly about “Chinese trawlers” fishing without restriction at night, while government patrol boats looked the other way.

The weak support provided to artisanal fishing communities by governments in Africa has a parallel in what traditional farming communities also experience. More than half of all citizens in sub-Saharan Africa are farmers, yet most governments devote only 5% of their public budget (less than this in many cases) to any kind of agricultural development. As a consequence, essential public goods like farm-to-market roads are either poorly repaired or missing completely, cutting farms off from marketing opportunities. Our research team visited fishing communities also cut off due to roads with deep potholes making them virtually undrivable. When we asked why government authorities hadn’t fixed the roads, we were told that visiting politicians regularly promised repairs just before election-time, but then never returned.

We asked community leaders if non-governmental organizations (NGOs) had taken an interest in their plight and were advocating on their behalf. Social justice and environmental NGOs claim to care for the special needs of those they call “fisherfolk,” and whilst some of the community leaders we questioned confirmed that well-meaning representatives from these organizations did visit to ask questions, they as well tended not to return and how they used the collected information remained a mystery. We knew our own research team would be seen in the same light if we failed to report back on the final outcome of our own project, so our intent is not to let this happen.

Featured image: photo by Robert Paarlberg

September 3, 2023

Is it a noun or an adjective?

The distinction between nouns and adjectives seems like it should be straightforward, but it’s not. Grammar is not as simple as your grade-school teacher presented it.

You may have learned about nouns with the description that nouns name a person, place, or thing. That’s a good enough place to start with young kids, but pretty soon someone will realize that “things” is pretty broad. Adjectives are tricky too: they are not just words that describe what nouns stand for; often adjectives clarify nouns by saying how much (several, twenty, most) or they may propose a comparison (more, better, faster).

A better approach to thinking about adjectives and nouns is to put semantic definitions aside and identify nouns and adjectives by their shapes—what sorts of endings they take. And they can be identified also by their syntactic behavior, that is by what other words they occur with or they can be substituted for.

Thinking about nouns and adjectives in this way allows us to work through some puzzles about what is a noun and what is an adjective. Consider a phrase like a stone wall or a steel cabinet. We know that wall and cabinet are nouns, but what about stone and steel? Are they adjectives or nouns?

Actually, they are nouns that modify other nouns. We can be confident of this for several reasons. First, we can’t modify stone or steel with adverbs like very or completely. Second, the most likely paraphrases are ones like “a wall made of stone” or “a cabinet made of steel.” And finally, there are contrasting expressions with actual adjectives, like stony and steely: “a stony demeanor” and “a steely glance.” A silk scarf is made of silk, while a silky scarf has the qualities of silkiness. Comparing stone and steel and silk with stony, steely, and silky helps to decide the issue.

Another noun-or-adjective puzzle involves expressions like the rich or the poor (and also the lucky, the good, the bad, the ugly, the lazy, the industrious, the strong, the weak, the meek, the humble, the mighty, and more). Are these nouns or adjectives? The presence of the would seem to suggest nouns. But that would entail many pairs of homophones, such as rich the noun and rich the adjective, and so on. A bigger problem is that words like rich and poor can occur with a preceding adverb (as in “The very rich”). And we can even make superlative forms (like “The best and the brightest” or “The happiest”). The evidence points to adjective here and so the best way to think about such phrases is as having an omitted noun, something like “The rich (people)” or “The poor (people).”

Finally, there are possessives. Some grammars, like Wilson Follett’s Modern American Usage, treat possessives as adjectives. Most modern grammars, however, see possessives as nouns or noun phrases. How can we be confident of this? Consider a phrase like “Truman’s temperament.” The word Truman’s modifies the noun temperament, so it has that feature of an adjective. But if we treat it that way, we open the door to a whole host of compound adjectives exactly like nouns: Harry Truman’s, The 33rd president’s, Give-Em-Hell-Harry’s, and so on. What’s more, possessives can be replaced by pronouns (his temperament), which is a feature of nouns, not adjectives. And perhaps most important is the contrast between true adjectives and possessives: compare the two sentences “Lincoln’s descendants resemble him,” where the pronoun easily refers back to Lincoln and “Lincolnesque people resemble him.” The latter sounds odd, because there is no noun for him to refer back to. But the first sentence is fine because Lincoln’s is a noun.

Grammar is less arbitrary than you might think.

Featured image by Rob Hobson via Unsplash, public domain

September 2, 2023

Pandemic? What pandemic?

Three months after the official US government “end” of three years of monitoring the COVID-19 pandemic that took over 1.1 million American lives, we are back to “new normal.” This is the Summer of Pink—Barbie, Taylor Swift, and the women’s soccer world playoffs. We witness divisive politics-as-usual in Washington DC and four indictments of former president Donald J. Trump. Carefree citizens seem to have forgotten the past three years of contagion, contentiousness, suffering, and death. Our “public health emergency” has been replaced by a “science of forgetfulness.” The insistence to return to “normal”—or something relatively close—is acute. This is both a symptom of “pandemic fatigue” and so-called existential relief at being alive, working from home, traveling abroad, and planning the future. (Everything now seems to be labeled “existential”—journalists, pundits, and politicians concur!)

Philosopher Albert Camus offered us a compelling narrative in 1947 that became a bestseller again in spring 2020 as the world shut down its social activities to withdraw into isolation. As a pied noir, Camus was born a French citizen in Algeria whose burden was to reconcile his two allegiances through philosophical insight. As a novelist, he set The Plague in Oran, a rather lifeless seaport he called “modern” where people’s daily routines were set by the sun and the seasons. Out of nowhere, rats invade. They bring horror, disease, and slow, breathless death. We track a predictable pattern of human behavior previously documented in real-world accounts of plagues from ancient Greece (the Justinian Plague of 541 BC), fourteenth-century Italy (Boccaccio on the Black Death), and Daniel Defoe (seventeenth-century Great Plague of London).

Camus’s plague invites rich comparisons to COVID-19: denial, anger, fear, hostility, resignation in the face of the uncontrollable. He seeks to explain the absurdity of unprovoked death, arbitrary infliction, and human inevitability in facing a “foe” that takes on animalistic, indeed anthropomorphic qualities intent on slaying the masses. “We all face death together” is Dr Rieux’s mantra, as he advocates fighting without a cure, while awaiting a vaccine, as people turn on one another. Similarly, we watch medical science argue with those who call COVID-19 a “hoax.” We defend doctors, nurses, parents, and vulnerable populations who defy anti-vaxxers. Dr Rieux calls for solidarity—what I call “heroic solidarity”—in order to rally the troops who have volunteered to help. On the metaphorical level, of course, he is recalling the French Resistance to fight Nazism during World War II:

Dr. Rieux resolved to compile this chronicle, so that he should not be one of those who hold their peace but should bear witness in favor of those plague-stricken people: so that some memorial of the injustice and outrage done them might endure; and to state quite simply what we learn in time of pestilence: that there are more things to admire in men than to despise.

Albert Camus, The Plague, 308

Did we face the foe of Covid and fight together in heroic solidarity: our behavior a confirmation of Camus’s idealism, “What’s true of all the evils in the world is true of plague as well. It helps men rise above themselves”? Or did we fail the challenge to unite, opting instead for selfishness, pettiness, and political weaponization of a virus that killed seven million people worldwide? As Camus hauntingly foretells, the plague bacillus never dies; it waits, below the surface, to rise again. Camus’s 74-year-old daughter offered her thoughts in March of 2020 when sales of the book soared; “Perhaps with the lockdown we will have some time to reflect about what is real, what is important, and become more human.” We can surely tell ourselves that next time, after further study and reflection, we will be more prepared. But will we?

Featured image via Unsplash, public domain

September 1, 2023

Five children’s classics that stand the test of time [reading list]

Five children’s classics that stand the test of time [reading list]

The books people remember most are often the ones from their childhoods, and it’s no surprise; many children’s books have survived decades of changing tastes and digital distractions, continuing to entertain generations of children and even adult readers.

Here are our top five picks for the young and young at heart!

1. The Adventures of Pinocchio by Carlo Collodi

Translated with introduction and notes by Ann Lawson Lucas

Did you know the story of Pinocchio comes from Italy? Carlo Collodi’s tale of the wooden puppet who wants to be a “real boy” has thrived beyond the borders of its native land. This fantasy had been widely translated and adapted many times—in 2022 alone there were three Pinocchio films! With a strong moral message and plenty of quirky characters, The Adventures of Pinocchio is a novel you won’t soon forget.

Read: The Adventures of Pinocchio

2. Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson

Edited by Peter Hunt

After being entrusted with a treasure map and warned to beware “a one-legged seafaring man,” young Jim Hawkins goes on a swashbuckling, high-seas adventure. There may be a one-legged man cooking meals below deck, but he doesn’t seem too bad… Treasure Island may have founded the “boy’s story” genre, but its moral complexity and gripping plot appeals to children and adults alike.

Read: Treasure Island

3. The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum

Edited with an introduction by Susan Wolstenholme and with the original illustrations by W. W. Denslow

The film and musical might be better known, but neither would exist without this 1900 novel. The first in L. Frank Baum’s Oz series, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz follows Dorothy Gale in a magical land where wild beasts talk, silver shoes have magic powers, and good witches offer protection with a kiss. It’s a surreal adventure with the important message of appreciating what you had all along.

Read: The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

4. Black Beauty by Anna Sewell

Edited by Adrienne E. Gavin

It might seem strange to find a horse’s autobiography on this list, but Anna Sewell’s 1877 novel is one of the bestselling children’s books in English. Join Black Beauty as he grows from colt to stallion, experiencing a range of kind and cruel owners. Anna Sewell may have originally written this book to expose animal cruelty to Victorian adults, but Black Beauty’s story has found its way into children’s hearts then and since.

Read: Black Beauty

The Water Babies by Charles Kingsley

Edited by Brian Alderson and Robert Douglas-Fairhurst

This might be one of the darkest children’s classics ever written. Forced to work as a chimneysweep, Tom later drowns in a tragic accident. After death he becomes a “water-baby” and is sent to help others across the world. Tom’s encounters with the animals of the river introduced children to the joys of nature and the new theory of Darwinism. Its message of redemption has given readers hope over many generations.

Read: The Water Babies

If you’ve enjoyed our recommendations, why not check out our full list of classic children’s titles on Bookshop?

Bookshop UK Bookshop USFeatured image by Aaron Burden on Unsplash.com (public domain)

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers