Oxford University Press's Blog, page 47

July 25, 2023

Revisiting toxic masculinity and #MeToo [podcast]

![Revisiting toxic masculinity and #MeToo [podcast]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1690367712i/34514506.jpg)

Revisiting toxic masculinity and #MeToo [podcast]

Globally, an estimated one third of all women have been subjected to physical or sexual violence; however, out of fear and socio-economic disenfranchisement, less than 40% of women who experience such violence seek help. In the United States alone, one in four women have suffered rape or attempted rape in their lifetime; for men, this figure is closer to one in 26.

The disparity is staggering; statistics on gendered violence reveal men are more likely to commit violence crimes, whereas women are far more likely to be the victims of violence.

Despite greater visibility and awareness of crimes against women, notions derived from what is understood to be “toxic masculinity,” and its proponents, are a growing influence over men, and especially young males.

In 2022, the US Secret Service released a report detailing the rising threat of domestic terrorism from males identifying as “involuntary celibates,” better known as “incels,” a network of mostly young males who uphold the misguided belief that sex with women is an entitlement to which they’ve been denied. This report considered misogyny not only a threat to women, but to national security itself.

So how do we stop the tide of violence and hate-speech stemming from the circulation of such misogynistic rhetoric, and how can we move forward while best supporting its victims?

On today’s episode, we explore two recognizable components in contemporary conversations on gender and gendered violence: that of “toxic masculinity” and of the #MeToo movement, the awareness campaign that came to global prominence in October 2017 after the public downfall of Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein.

First, we welcomed Robert Lawson, the author of Language and Mediated Masculinities: Cultures, Contexts, Constraints, to share how language intersects with masculinities in media spaces and how it may be our best weapon in combatting rising misogyny, especially online. We then interviewed Iqra Shagufta Cheema, the editor of The Other #MeToos, who spoke with us about the origins of the #MeToo movement, how it has been received around the world, and how it has changed—and will continue to change—to meet the needs of the victims for which it advocates.

Check out Episode 85 of The Oxford Comment and subscribe to The Oxford Comment podcast through your favourite podcast app to listen to the latest insights from our expert authors.

Oxford Academic (OUP) · Revisiting Toxic Masculinity and #MeToo – Episode 85 – The Oxford CommentRecommended readingIn his interview with us, Robert Lawson discussed positive masculinity as represented by the various characters on the American sitcom, Brooklyn Nine-Nine. Read this chapter from Language and Mediated Masculinities: Cultures, Contexts, Constraints an in-depth look at how the characters subvert and destabilize hegemonic forms of masculinity through their use of language in building relationship with each other. Language and Mediated Masculinities is part of the Studies in Language and Gender series.

Read this chapter by Asmita Ghimire and Elizabethada A. Wright from The Other #MeToos on protest signs and placards written in Global English that allow women from very different contexts to identify with each other and builds on how people in non-dominant spaces can engage in semiotic reconstruction to adapt dominant languages for their individual needs. The Other #MeToos, edited by Iqra Shagufta Cheema, is part of the Oxford Studies in Gender and International Relations series.

This chapter from Credible Threat: Attacks Against Women Online and the Future of Democracy by Sarah Sobieraj explores how women who attempt to participate in public discussions about political and social issues online confront a hostile speaking environment analogous to the hostile work environments identified in policies addressing sexual harassment in the workplace.

Why is it the case that men perpetrate the vast majority of all violence against women and girls? This chapter from Jacqui True’s Violence against Women: What Everyone Needs to Know® explores the argument that masculinity is in fact dynamic, rather than fixed by biology or any other factor, and that it is the social constructions of masculinity within and across almost all societies that have encouraged and rewarded male aggression and violence toward themselves and others.

Read the following Open Access articles from our journals:

“Extremism and toxic masculinity: the man question re-posed” by Elizabeth Pearson in International (November 2019)“Online Abuse of Feminists as An Emerging form of Violence Against Women and Girls” by Ruth Lewis, Michael Rowe, and Clare Wiper in The British Journal of Criminology (November 2017)“Retweet for justice? Social media message amplification and Black Lives Matter allyship” by Jessica Roden, Valerie Kemp, and Muniba Saleem in Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication (January 2023)“’This Patriarchal, Machista and Unequal Culture of Ours’: Obstacles to Confronting Conflict-Related Sexual Violence” by Anne-Kathrin Kreft in Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society (Summer 2023)“Promoting positive masculinities among young people in Stockholm, Sweden. A mixed-methods study” by M Salazar and A Cerdán-Torregrosa in European Journal of Public Health (October 2022)Featured image: Mihai Surdu, CC0 via Unsplash.

Exploring language and masculinities in the media landscape

Exploring language and masculinities in the media landscape

We all engage with different media formats on a daily basis. From watching television shows and movies, to catching up with the news, playing videogames, reading a blogpost from a favourite author, downloading the latest app, or discussing current events with people on social media, the media is an integral (and inescapable) part of our lives. While there is some evidence to suggest rates of use across commercial media platforms is declining, a recent Ofcom report found that over 90% of the British adult population are regular users of the internet and British viewers are still watching over five hours of television per day, even as overall media consumption is now fragmented across smart phones, online platforms, radio stations, television, streaming services, and print.

Men in the mediaWhat is also clear across a variety of news reports, television shows, social media sites, computer games, and other media formats is that men appear to dominate, both in terms of focus and the number of contributions they make. In the case of televised and printed media, this dominance raises questions of representation, equity, and the shape of contemporary gender relations. In other spaces, such as the manosphere (a loose collection of blogs, websites, Twitter accounts, and Reddit communities dedicated to a variety of men’s issues), this dominance is inflected by a virulent strand of networked misogyny, anti-feminism, and male supremacism.

This intersection of men and media has been a research focus in academia, public policy work, and the charity sector for some time now. This research highlights how the media sets out cultural scripts of what’s “normal” and “accepted.” Media outputs give audiences exemplars and models they can compare themselves against, offering aspirational goals to strive for or images of self-hood to avoid. The media can also subvert these scripts, pushing gender discourses into new territory, challenging established wisdoms, and destabilising conventional stereotypes. By virtue of their interactivity and sense of community, manosphere spaces bring an added layer of complexity to proceedings, with research suggesting that their technological affordances play a key role in driving online radicalisation.

And it is clear that the diversity of media influences can have substantial real-world effects. For instance, a recent survey commissioned by BBD Perfect Storm found that 51% of men believe that the media negatively impacts how successful they feel, while a joint UN Women/UNICEF report from 2022 notes “the particular role of news media reporting in perpetuating discriminatory gender norms and stereotypes, and bolstering the social permission structures that normalize this violence.” The arrest of Andrew Tate, the self-proclaimed “king of toxic masculinity,” in December 2022 brought some of these issues into ever clearer focus, with a number of teachers, educators, charity leaders, parents, and counsellors expressing concerns about how Tate’s controversial talking points around consent, respect, dating, gender relations, and women were being parroted by male pupils in school hallways and classrooms up and down the country.

Exploring the language of men in the mediaGiven the ubiquity of men in the media, it would seem to be an obvious place to look at how language relates to issues of contemporary masculinities. But while masculinities studies is a well-established field, the empirical analysis of the language used by (and about) men is a relatively new part of language and gender research. In my own work in this area, I explore how language is used by men across a range of media contexts, including fatherhood forums, television comedy shows, newspaper articles, manosphere communities, and alt-right spaces. More specifically, I’m interested in the history of “tough” masculinity in the British press, evaluations of “ideal” masculinity in the manosphere, the role of the media in promoting “positive” masculinities (with specific focus on the comedy show Brooklyn Nine-Nine), and the representation of caring models of fatherhood in online forums.

Why might we want to apply a linguistic lens to men in different media spaces? First and foremost, language is the primary means through which we relate to one another and (dis)align ourselves from other groups and categories. By paying close attention to linguistic practice, we can learn more about contemporary gender dynamics and how language is used to structure these relations. Second, by analysing the kinds of linguistic strategies used in manosphere and alt-right spaces, we can better understand how these strategies become part of a system of persuasion and manipulation to recruit young men to male supremacist ideologies. In the context of the growing threat posed by networked misogyny (captured in the toxic narratives promoted by Tate and other “manfluencers”), challenging these strategies becomes an important pedagogical intervention. Finally, it is clear that some media outputs offer a more positive and healthier configuration of masculinity and we can do a lot to learn about how these outputs use language to disrupt some of the more damaging aspects of masculine behaviour.

For many people, language is an unremarkable part of everyday life, yet it is through this mundanity that language retains its power to shape society in subtle and indirect ways. The job of a linguist is to bring to light these hidden systems of differentiation and alignment, in order to show how language contributes to ongoing processes of discrimination, bias, and prejudice. The media reflects (and influences) both the good and the bad of who we are and what we stand for and, because of how it sits within a broader system of gender discourses, different media forms are ideal spaces for exploring the contemporary construction of modern-day masculinities (and of gender relations more generally). With the media so deeply integrated into our everyday lives, and substantial concerns being expressed about the problems of networked misogyny, gender representation, online radicalisation, male supremacism, and a whole host of other social ills, we need to use all the tools at our disposal to try to address these problems.

Featured image from the book cover of Language and Mediated Masculinities: Cultures, Contexts, Constraints (OUP 2023)

July 21, 2023

How to write a journal article

How to write a journal article

Academics normally learn how to write while on the job, suggests Michael Hochberg. This usually starts with “the dissertation and interactions with their supervisor. Skills are honed and new ones acquired with each successive manuscript.” Writing continues to improve throughout a career, but that thought might bring little solace if you are staring at a blank document and wondering where to start.

In this blog post, we share tips from editors and outline some ideas to bear in mind when drafting a journal article. Whether you are writing a journal article to share your research, contribute to your field, or progress your career, a well-written and structured article will increase the likelihood of acceptance and of your article making an impact after publication.

Four tips for writing wellStuart West and Lindsay Turnbull suggest four general principles to bear in mind when writing journal articles:

Keep it simple: “Simple, clear writing is fundamental to this task. Instead of trying to sound […] clever, you should be clear and concise.”Assume nothing: “When writing a paper, it’s best to assume that your reader is [subject] literate, but has very little expert knowledge. Your paper is more likely to fail because you assumed too much, than because you dumbed it down too much.”Keep to essentials: “If you focus on the main message, and remove all distractions, then the reader will come away with the message that you want them to have.”Tell your story: “Good […] writing tells a story. It tells the reader why the topic you have chosen is important, what you found out, and why that matters. For the story to flow smoothly, the different parts need to link clearly to each other. In creative writing this is called ‘narrative flow’.”“A paper is well-written if a reader who is not involved in the work can understand every single sentence in the paper,” argues Nancy Dixon. But understanding is the bare minimum that you should aim for—ideally, you want to engage your audience, so they keep reading.

As West and Turnbull say, frankly: “Your potential reader is someone time-limited, stressed, and easily bored. They have a million other things to do and will take any excuse to give up on reading your paper.”

A complete guide to preparing a journal article for submissionConsider your research topicBefore you begin to draft your article, consider the following questions:

What key message(s) do you want to convey?Can you identify a significant advance that will arise from your article?How could your argument, results, or findings change the way that people think or advance understanding in the field?As Nancy Dixon says: “[A journal] editor wants to publish papers that interest and excite the journal’s readers, that are important to advancing knowledge in the field and that spark new ideas for work in the field.”

Think about the journal that you want to submit toResearch the journals in your field and create a shortlist of “target” journals before writing your article, so that you can adapt your writing to the journal’s audience and style. Journals sometimes have an official style guide but reading published articles can also help you to familiarise yourself with the format and tone of articles in your target journals. Journals often publish articles of varying lengths and structures, so consider what article type would best suit your argument or results.

Check your target journals’ editorial policies and ethical requirements. As a minimum, all reputable journals require submissions to be original and previously unpublished. The ThinkCheckSubmit checklist can help you to assess whether a journal is suitable for your research.

Now that you’ve decided on your research topic and chosen the journal you plan on submitting to, what do you need to consider when drafting each section of your article?

Create an outlineFirstly, it’s worth creating an outline for your journal article, broken down by section. Seth J. Schwartz explains this as follows:

The typical structure of a journal articleTitleMake it concise, accurate, and catchyAvoid including abbreviations or formulaeKeywordsChoose 5-7 keywords that you’d like your journal article to appear in the search results forAbstractSummarize the findings of your journal article in a succinct, “punchy”, and relevant wayKeep it brief (200 words for the letter, and 250 words for the main journal)Do not include referencesIntroductionIntroduce your argument or outline the problemDescribe your approachIdentify existing solutions and limitations, or provide the existing context for your discussionDefine abbreviationsMethodsWriting an outline is like creating a map before you set out on a road trip. You know which roads to take, and where to turn or get off the highway. You can even decide on places to stop during your trip. When you create a map like this, the trip is planned and you don’t have to worry whether you are going in the correct direction. It has already been mapped out for you.

For STEM and some social sciences articles

Describe how the work was done and include plenty of detail to allow for reproductionIdentify equipment and software programsResultsFor STEM and some social science articles

Decide on the data to present and how to present it (clearly and concisely)ConclusionSummarise the key results of the articleDo not repeat results or introduce new discussion points AcknowledgementsInclude funding, contributors who are not listed as authors, facilities and equipment, referees (if they’ve been helpful; even though anonymous)Do not include non-research contributors (parents, friends, or pets!)ReferencesCite articles that have been influential in your research—these should be well-balanced and relevantFollow your chosen journal’s reference style, such as Harvard or ChicagoList all citations in the text alphabetically at end of the articleSharing dataMany journals now encourage authors to make all data on which the conclusions of their article rely available to readers. This data can be presented in the main manuscript, in additional supporting files, or placed in a public repository.

Journals also tend to support the Force 11 Data Citation Principles that require all publicly available datasets be fully referenced in the reference list with an accession number or unique identifier such as a digital object identifier (DOI).

PermissionsPermission to reproduce copyright material, for online publication without a time limit, must also be cleared and, if necessary, paid for by the author. Evidence in writing that such permissions have been secured from the rights-holder are usually required to be made available to the editors.

Learning from experiencePublishing a journal article is very competitive, so don’t lose hope if your article isn’t accepted to your first-choice journal the first-time round. If your article makes it to the peer-review stage, be sure to take note of what the reviewers have said, as their comments can be very helpful. As well as continuing to write, there are other things you can do to improve your writing skills, including peer review and editing.

Christopher, Marek, and Zebel note that “there is no secret formula for success”, arguing that:

The lack of a specific recipe for acceptances reflects, in part, the variety of factors that may influence publication decisions, such as the perceived novelty of the manuscript topic, how the manuscript topic relates to other manuscripts submitted at a similar time, and the targeted journal. Thus, beyond actively pursuing options for any one particular manuscript, begin or continue work on others. In fact, one approach to boosting writing productivity is to have a variety of ongoing projects at different stages of completion. After all, considering that “100 percent of the shots you do not take will not go in,” you can increase your chances of publication by taking multiple shots.

July 19, 2023

Language history and we: the case of “like”

Language history and we: the case of “like”

In 1894, the Danish linguist Otto Jespersen brought out a book titled Progress in Language. Whether anything in language can legitimately be labeled as progress is a moot point, but no one doubts that language indeed has history. The larger the speaking community and the more mobile the population, the faster the change. Problems arise when we go beyond such trivialities. Language does not remain stable even in our lifetime, and different people react differently to this phenomenon. Assuming that we notice the changes, do we accept, or do we resist them? I will skip phonetic problems, because it is the vocabulary and usage that deserve our attention here.

This post owes its existence to Valerie Fridland’s book Like, Literally, Dude: Arguing for the Good in Bad English (Viking, 2023). The book deals with some processes in Modern (American) English, and the author is very much on the side of “progress in language.” If I am not mistaken, her main point is that as long as some widespread phenomenon can be explained, it should be accepted. This approach does not convince me. For instance, I have read numerous interviews with celebrities in sports and music, and almost every noun in them is accompanied by a single epithet, namely, f—ing. I can easily explain why people speak so: the word is nowadays on everybody’s lips from the age of three, and many Americans don’t know any other equally expressive qualifying word. This argument does not make me look “for the good in [their] bad English.”

Some chapters in the book are less exciting than others: among them, the triumph of the word dude. Dude is a respectable relative of the aforementioned epithet: instead of using many nouns, people have limited their vocabulary to a single one: this is practical and convenient, because with overchoice comes much sorrow: the more knowledge, the more grief.

This is what an Old English text looks like.

This is what an Old English text looks like.First page of the Peterborough Chronicle, via Wikimedia Commons (public domain)

The chapter that especially interested me deals with the use of like, as in “Like, I came yesterday and found, like, only three people in the auditorium” or: “I said ‘Like, who? I? No way’” (those are my, not the author’s examples). The use of like turned out to be an amazingly fertile subject for modern scholars. Successful academic careers have grown from it. I was once present at a conference at which the greatest world specialist in like gave a plenary talk on it. The subject is not uninteresting, but it is trivial. Like is a hesitation phenomenon (to give it status, the term discourse marker has been used about it), and the speaker, to gain time, makes pauses and fills them with like. No doubt, in oral speech, such “markers” have existed forever, but here too caution should be exercised. Fridland writes: “For instance, the Old English word þa, meaning ‘then’, served as a foregrounding discourse marker in narratives and was often associated with colloquial speech. …some Old English scholars suggest þa occurred so often in some early texts that it can’t have carried much semantic content, a complaint that echoes our modern assessment of excessive like use” (p. 102). No references are given, but I am sure that such an opinion exists. It should be taken with a huge grain of salt. A written text obeys the laws of its own, and in the Middle Ages, the training of a scribe took years. It is improbable that a qualified monk would have inserted an unpremeditated “discourse marker,” “discourse thickener, “linguistic focuser” on a piece of expensive parchment.

The syntax of Old English, like the syntax of all the old Germanic languages, had hardly any subordinating conjunctions. The narrative went so: “… and they besieged the fortress, and they began to starve, and they attacked, and they fled, and fifty of them died” (try to disambiguate the pronouns!). Þa was certainly a marker, though hardly a spontaneous “attention-getting device,” and comparing it with our pestiferous like is unproductive. The fact that “our” like sometimes occurred as early as at the end of the eighteenth century is beside the point. Everything has a beginning, but no one in the past said: “He, like, tried to grab my bag and I, like, screamed.”

Ripped jeans: not in my taste.

Ripped jeans: not in my taste.Via Pxfuel (public domain)

Fridland asks: “Why despite the surprisingly long evolutionary history, are these speech features still perceived as an ‘emergent’ and disastrous blight on modern speech? And why is like the worst offender of them all?” (p. 105). The answer is obvious (I’ll ignore the reference to the surprisingly long evolutionary history): there is a difference between a solitary pimple (which may even be “cute”) and a skin rash. Indeed, if John says: “I exercised for, like, ten hours,” fine: let him. But quantity has become quality: like inundated our speech and stopped meaning “approximately.” Especially characteristic is the author’s following statement: “This form of nonstandard like use seems to be the one people find most difficult to digest, which is unfortunate, since it’s the most rapidly expanding one in English” (p. 114). I am not convinced. The epithet f—ing is, undoubtedly, the one most rapidly expanding in English, and the same is true of the verb f— up. So what? Should we embrace them?

Fridland does not mention the process, known as the regeneration of linguistic phenomena. It occurs even in phonetics but more often in grammar, when “progressive” forms yield to the once discarded ones (this once happened in the history of umlaut and in the conjugation of verbs, though not in English). The longevity of like is unpredictable. Several decades ago, the main filler was you know, which Fridland mentions only in passing. I remember a speech by a doctoral candidate in which you know took up half of the time. Where is this discourse marker, plot thickener, and linguistic focuser now? Gone or almost gone! At around the same time, the epithet cool conquered the world (its defunct predecessor was groovy). It is not quite dead yet but certainly not at the forefront of the adjectival world.

Aldous Huxley, a highbrow.

Aldous Huxley, a highbrow.Via Wikimedia Commons (public domain)

In grammar, popular usage almost always wins. Gone is the third person singular speaketh. Four centuries ago, speaks, says, and so forth were northern vulgarisms, and Shakespeare allowed only Falstaff’s boon companions to use it. Now this is Standard English. Other grammatical forms remain unstable for quite some time. For example, American English lost the form whom rather long ago. The so-called norm tries to reinstall it, and the result is pathetic. Here are two recent examples from respectable sources: “Video showed as officers pursue the suspect whom police reported had been taken into custody within minutes” and “This is true of obstetricians whom I believe are among the most sympathetic physicians in general.” But the parasite like is not grammar. It is “usage”: it arrived, and it may or may not go away.

I think Fridland mentions the word culture only once in the entire book, but isn’t language, in addition to being a means of communication, also an instrument of culture, and don’t most phenomena of culture have a semiotic value in our life? Do all of us have to wear ripped jeans because such jeans “are here to stay,” like, allegedly, like (p. 100; said about like, not about jeans). Aldous Huxley once wrote an essay titled “I am a Highbrow,” in response to an essay titled “I am a Lowbrow.” I am on Huxley’s side. I am perfectly happy wearing well-made clothes and enjoy the rich vocabulary of our best writers. Far be it from me to enforce my tastes on anyone, but I hate the fillers like and you know, and though I know that the lowest forms of culture, like weeds, usually prevail, I at least don’t hasten to contribute to their triumph.

If this subject arouses any interest, I may go on in the same vein next week.

Featured image by AC works Co., Ltd., via Pixabay (public domain)

July 17, 2023

Looking through the ice: cold-adapted vision in Antarctic icefish

Looking through the ice: cold-adapted vision in Antarctic icefish

A recent study reveals the genetic mechanisms by which the visual systems of Antarctic icefishes have adapted to both the extreme cold and the unique lighting conditions under Antarctic sea ice.

Antarctica may seem like a desolate place, but it is home to some of the most unique lifeforms on the planet. Despite land temperatures averaging around -60°C and ocean temperatures hovering near the freezing point of saltwater (-1.9°C), a number of species thrive in this frigid habitat. Antarctic icefishes (Cryonotothenioidea) are a prime example, exhibiting remarkable adaptations that allow them to survive in the icy waters surrounding the continent. For example, these fish have evolved special “antifreeze” glycoproteins that prevent the formation of ice in their cells. Some icefishes are “white-blooded” due to no longer making hemoglobin, and some have lost the inducible heat shock response, a nearly universal molecular response to high temperatures. Adding to this repertoire of changes, a recent study published in Molecular Biology and Evolution reveals the genetic mechanisms by which the visual systems of Antarctic icefishes have adapted to both the extreme cold and the unique lighting conditions under Antarctic sea ice.

A team of researchers, led by Gianni Castiglione (now at Vanderbilt University) and Belinda Chang (University of Toronto), set out to explore the impact of sub-zero temperatures on the function and evolution of the Antarctic icefish visual system. The authors focused on rhodopsin, a temperature-sensitive protein involved in vision under dim-light conditions. As noted by Castiglione, a key role for rhodopsin in cold adaptation was suggested by their previous research.

“We had previously found cold adaptation in the rhodopsins of high-altitude catfishes from the Andes mountains, and this spurred us into investigating cold adaptation in rhodopsins from the Antarctic icefishes.”

Indeed, the authors observed evidence of positive selection and accelerated rates of evolution in rhodopsins among Antarctic icefishes. Taking a closer look at the specific sites identified as candidates for positive selection, Castiglione and coauthors found two amino acid variants that were absent from other vertebrates. These changes are predicted to have occurred during two key periods in Antarctic icefish history: the evolution of antifreeze glycoproteins and the onset of freezing polar conditions. This timing suggests that these variants were associated with icefish adaptation and speciation in response to climatic events.

To confirm the functional effects of these two amino acid variants, the researchers performed in vitro assays in which they created versions of rhodopsin containing each variant of interest. Both amino acid variants affected rhodopsin’s kinetic profile, lowering the activation energy required for return to a “dark” conformation and likely compensating for a cold-induced decrease in rhodopsin’s kinetic rate. In addition, one of the amino acid changes resulted in a shift in rhodopsin’s light absorbance toward longer wavelengths. This dual functional change came as a surprise to Castiglione and his co-authors. “We were surprised to see that icefish rhodopsin has evolved mutations that can alter both the kinetics and absorbance of rhodopsin simultaneously. We predict that this allows the icefish to adapt their vision to red-shifted wavelengths under sea ice and to cold temperatures through very few mutations.”

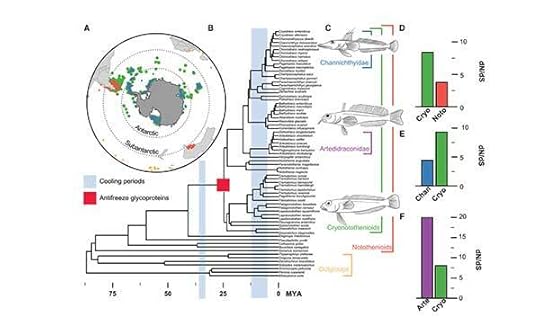

Accelerated evolutionary rates in icefish rhodopsin. (A) Geographic distribution of icefishes and outgroup species collected from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility. All catch data for each species are displayed and colored according to the classifications in (B). (B) Phylogenetic relationships of icefishes and outgroups from Rabosky et al. (2018). Periods of cooling (blue) before and after the evolution of AFGPs (red) are shown according to Near et al. (2012). (C) Rhodopsin (rh1) evolutionary rates of: (D) Notothenioids relative to all Antarctic cyronotothenioids; (E) Channichthyidae relative to other cyronotothenioids; and (F) Artedidraconidae relative to other cyronotothenioids.

Accelerated evolutionary rates in icefish rhodopsin. (A) Geographic distribution of icefishes and outgroup species collected from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility. All catch data for each species are displayed and colored according to the classifications in (B). (B) Phylogenetic relationships of icefishes and outgroups from Rabosky et al. (2018). Periods of cooling (blue) before and after the evolution of AFGPs (red) are shown according to Near et al. (2012). (C) Rhodopsin (rh1) evolutionary rates of: (D) Notothenioids relative to all Antarctic cyronotothenioids; (E) Channichthyidae relative to other cyronotothenioids; and (F) Artedidraconidae relative to other cyronotothenioids. © The Author(s) 2023. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of Society for Molecular Biology and Evolution

Interestingly, the amino acid changes observed in the Antarctic icefishes were distinct from those conferring cold adaptation in the high-altitude catfishes previously studied by the team, suggesting multiple pathways to adaptation in this protein. To continue this line of study, Castiglione and his colleagues hope to investigate cold adaptation in the rhodopsins of other cold-dwelling fish lineages, including Arctic fishes. “Arctic fishes share many of the cold-adapted phenotypes found in the Antarctic icefishes, such as antifreeze proteins. However, this convergent evolution appears to have been accomplished through divergent molecular mechanisms. We suspect this may be the case in rhodopsin as well.”

Unfortunately, acquiring the data needed to conduct such an analysis may prove difficult. “A major obstacle to our research is the difficulty of collecting fishes from Antarctic and Arctic waters,” says Castiglione, “which limits us to publicly available datasets.” This task may become even more challenging in the future as these cold-adapted fish are increasingly affected by warming global temperatures. As Castiglione points out, “Climate change may alter the adaptive landscape of icefishes in the very near future, as sea ice continues to melt, forcing the icefish to very likely find themselves at an evolutionary ‘mismatch’ between their environment and their genetics.”

Featured image by Uwe Kils, via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

July 13, 2023

The joy of playing duets

At a recent string teachers’ conference, coffee break in full swing, a delegate got out his violin and began to play a lively tune. Within minutes he was joined by another who spontaneously improvised a second part. It was a delight to all who were present.

There is clearly an irresistible appeal to playing with another musician. Practising a musical instrument can at times be a lonely pursuit; playing with a friend or teacher can make for a richer and more satisfying musical experience than playing on one’s own.

Indeed, the duet genre has attracted composers throughout musical history. Piano duets became increasingly popular from the second half of the eighteenth century. Before the age of recordings, piano duet versions of symphonies, large scale orchestral works, and operatic highlights allowed domestic players to become familiar with music that they might never hear live. Mozart and his sister Nannerl regularly performed duets as they toured around Europe and Mozart wrote several sonatas for four hands at one piano.

Pianists looking for duet repertoire have a rich range of material to choose from. From compositions by Brahms, Dvorak, Debussy, and Poulenc to the increasingly popular music of Fanny Hensel Mendelsohn, Amy Beach, and Cecile Chaminade, piano duettists have no shortage of repertoire to choose from.

“There is a human need for connection: music is a social activity that binds us together.”

Similarly, violinists are spoilt for choice when it comes to duet repertoire. Mozart’s “easy” violin duets K 487 (often a student’s first introduction to “real” duet playing), the joyful Telemann Six Canonic Sonatas, the enduringly attractive violin duets of Pleyel, Dancla, and Mazas: these have all been the mainstay of many violinists’ musical journey. Bartok’s 44 Duos for Two Violins, intended to be pedagogical works rather than for concert performance, give players a wonderful experience of intricate rhythms, poly tonality, canons, and inversions. From the wonderfully exuberant classical style of Maddalena Sirmen to the exciting musical language of Polish composer Graźyna Bacewicz, the violin duet repertoire is rich and wide-ranging.

As part of any musical training, the learning and playing of duets has many benefits. A teacher-pupil duet may help encourage a strong sense of pulse and rhythm. Playing and sight-reading duets that are at an easier technical level than a player has achieved can also boost confidence and help develop sight-reading skills—you have to keep up! A recent development with some music examination boards now sees duet playing appear as an option in some instrumental music examinations.

Teachers will often ask their students to think about particular things when playing duets, such as:

Am I playing a tune or an accompaniment?Do I need to adjust my dynamics to achieve better musical balance?What’s happening in the harmony at this point?Am I able to make eye contact with my duet partner?Learning and practising these important ensemble skills is an essential part of any musician’s development.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, there is a human need for connection: music is a social activity that binds us together. Playing duets can be a joyful, fruitful, and musically engaging activity. It may even give players the confidence to get their instrument out in a café during the coffee break and start duetting with someone… bringing a joyful smile to all who listen.

Featured image: Violin duet performance by cyano66 via Canva

July 12, 2023

Etymology gleanings for June 2023

Etymology gleanings for June 2023

Not that there is a lot to glean, but perhaps it is worthwhile to answer a few questions now, rather than waiting for another harvest. As usual, I’ll leave without comment the remarks that informed me about something I did not know. I can only express my gratitude to those who cite the words from all kinds of dialects and languages, such as pertain to the topics under discussion.

Robert Burns

Robert BurnsVia Wikimedia Commons, public domainGin a body meet a buddy

I would like to dispel a misconception about the pronunciation of some American vowels. In many parts of the United States, the vowel in not, hot, and their likes has lost labialization (rounding), and Europeans tend to associate it with Italian, Spanish, Russian, etc. a in mama. There was a change at the close of the Middle English period and later, known as the Great Vowel Shift. As a result of this epochal change (which, in a way, is a process still going on), mate, mite, mote, meet, and so forth are today pronounced the way familiar to us, though each major dialect went its own way. The shift affected all the old long vowels. As usual in the history of the Germanic languages, short vowels tended to form a close partnership with their long counterparts. For example, in the American Midwest, where I live, the vowel of small sounds to most Europeans like a in spa. (Listen to some rendition of “It’s a small world after all.”) That is why “short o” in hot, cot, and their likes is also delabialized, and foreigners believe that they hear hut and cut. Though such vowels are realized in many different ways, outsiders notice only the most salient features. The point of this digression on the history of English sounds is that in the pronunciation of American speakers, not and nut, hot and hut, cot and cut are NOT homonyms pairwise, and there is no chance that any native speaker would have confused body and buddy. Therefore, the derivation of buddy from body is improbable.

It is never hot in this hut.

It is never hot in this hut.Photo via Unsplash, public domain

And one more note on American pronunciation, namely, on the voicing of intervocalic t. In connection with the proposed etymology of buddy (with d supposedly going back to Dutch t) another reader mentioned the fact that now he understands why British actors affecting an American accent say d in words like writer. Yet here too one should exercise caution. That all or many Americans hear d in the middle of writer is a fact. Otherwise (as I noted in my previous posts), my students would not have spelled deep-seeded for deep-seated. Nor would futile have merged with feudal. But it is a weak d. Consequently, in dating, the first consonant and the one following the stressed vowel are non-identical variants of the same phoneme, just as in street, the first t is not identical with the second one. By the way, the voicing of intervocalic t is also known from some British dialects, and at least one-word bears witness to it. Porridge is an etymological doublet of pottage (today, remembered mainly or only from a mess of pottage): t was weakened to d and then “rhotacized.”

Children learn such subtleties with no trouble at all. Adults, by contrast, hardly ever manage to overcome the fateful threshold. I wonder whether they ever succeed in becoming indistinguishable from natives even on paper. Perhaps sometimes subtler, but not quite like them. Kipling once said that Joseph Conrad’s style was better than anyone’s, but one could see that every sentence of his was a translation (Conrad was a Pole). I hope he was wrong and reacted spitefully to Conrad’s prolixity.

Goldilocks in a mess with a mess of pottage.

Goldilocks in a mess with a mess of pottage.Via New York Public Library, public domainThe word night

As I wrote in my previous post, night is a Common Indo-European word. Scholars have been debating for a long time how Indo-European spread over the enormous territory from India to Norway and where its homeland was. The Germanic form is, in principle, the same everywhere (Gothic nahts, Old English neaht, Old Icelandic nótt, etc.). The protoform must have perhaps sounded approximately like nokw-t-. The root vowels vary: Latin nox, noctis versus Classical Greek núx-, and so forth. There is no evidence of the borrowing of the Germanic form from Greek. It is possible that the vowel of the Greek noun (u) differs from Germanic a by ablaut, but the details are hard to reconstruct, and they are irrelevant to the present discussion.

Love in English and GreekI received a letter from a reader who teaches the Bible and wonders why for Greek Érōs, philía, agápē, and stórge English regularly uses love, even though English is famous for its synonymy. This question has often been discussed by specialists in both theology and historical semantics. The shades of meaning highlighted by Greek are easy to render in Modern English, but the Old Germanic languages had few synonyms for “love,” noun or verb. From Old Icelandic, a language with an extremely rich vocabulary, we know elska “to love” and ást “love” (noun; like many other abstract feminine nouns in Old Germanic, ást was often used in the plural: ástir; a phenomenon worthy of attention).

Nótt, the Old Scandinavian goddess of Night

Nótt, the Old Scandinavian goddess of Night“The Night” by Peter Nicolai Arbo, via Wikimedia Commons, public domain

Old English did have several words for “tender affection,” but lufu was the one most often used, and viewed from our perspective, it means “fondness, favor; desire; kind action,” and in legal documents, “amicable settlement.” For “love of God” only lufu was used. English is not poor in the words of this semantic sphere: compare fondness (used above as a gloss), affection, attachment, and passion, among others. But love “monopolized” the biblical text and thus deprived it of subtle distinctions. Perhaps the only synonym for love that has broken through in Biblical English is adoration, as in “the adoration of the Magi,” but in this context, adoration is not the same as love. Other than that, an English speaker can love God, children, vacationing in the Alps, and Dutch cheese (clearly, an overused word).

In Greek, no word for “love” had sacral overtones. For “sexual love; passion,” we find Érōs. The word for this concept is absent from the oldest “postclassical” languages; hence the ubiquitous adjective erotic, a borrowing. Greek agápē (feminine) made its way into the Greek text of the New Testament and occurred in the plural (compare Icelandic ástir, above!); it means “brotherly love.” Brotherly love, naturally, takes me to Philadelphia and its name. Greek philía meant “friendship; affection” and became the popular first component of European words like philosophy and philology. The adjective of this root referred to things pleasant and pleasurable. Finally, the noun stórgē, though often translated as “love,” meant “loyalty; devotion” and referred to one’s attitude toward the ruler, one’s children, one’s profession, and so forth.

Several modernized English versions of the New Testament exist, and last time, I mentioned how some newer redactions dealt with the adverb sore. But no one seems inclined to do similar justice to the Greek nouns for “love.” The verb love is also untouchable. I’ll be grateful to those more proficient in Greek and Biblical studies than I am for giving a better answer to our correspondent.

Featured image: “Adoration of the Magi” by Sandro Botticelli, via Wikimedia Commons (public domain)

July 10, 2023

Reputations at Stake: 10 cautionary recommendations for leaders

Reputations at Stake: 10 cautionary recommendations for leaders

There are multiple rewards and risks that stem from how we manage our reputation, from the macro level for countries and governments through to the meso level for organisations and to the micro level for leaders and managers.

Reputation has rewards for those who engage and costs for those who abscond. The virtual events company, Hopin started with four employees in 2020 and was valued at $2 billion in less than a year but has recently struggled to live up to the hype of virtual events post-pandemic. The downfall for organisations and leaders can be steep. Theranos, the American health technology corporation, was valued at $10 billion in 2013 and 2014, but when people started to question the validity of its technology, the company nosedived and was eventually dissolved. The Founder and CEO, Elizabeth Holmes, will shortly be reporting to prison for defrauding investors.

Alongside the day-to-day challenges of leading organisations, there are existential threats that leaders face, including geopolitical tensions, climate change, and unprecedented levels of inequality. Leaders have a moral duty to act responsibly and if the public sniff they are being misled, as was the media’s response to Boris Johnson’s denial of a Christmas Party in December 2020 when there was a UK-wide coronavirus lockdown, which the House of Commons Committee of Privileges found he misled the House, or Liz Truss’s infamous mini budget in 2022 that triggered financial market chaos, then the reputation implications are unforgiving, as both former UK Prime Ministers found through being ousted.

Growing emphasis on purposeOrganisations such as the Business Roundtable, the World Economic Forum, and the British Academy are advocating businesses to be purpose led. This means leaders must ensure that their organisation’s purpose is aligned with relevant external movements like #MeToo and Black Lives Matters.

“A failure to ensure alignment between an organisation’s purpose and societal expectations risks reputation damage.”

Understanding who our different stakeholders are and reflecting on how they are important is an essential mechanism to ensure external and internal alignment. We may not always like what stakeholders say or do and at times we may decide to push back, but they are nevertheless a vital source of data that we need to understand, reflect on, and respond to. P&O’s firing of staff via videoconference showed a disconnection between the expectations of society and their actions, which created ill feeling among multiple stakeholders and undermined its reputation.

There has been a lot of rhetoric around purpose from investment in ESG to promoting diversity on leadership teams. The public are now more discerning and impatient for change, which is a reputation threat if the rhetoric leaders give is not matched by action. This was captured by Greta Thunberg’s 2021 “blah, blah, blah” statement to world leaders when their comments about building back better in response to the climate emergency were not perceived to have been matched by their policies.

The risk of reputation damageWhen we witness the likes of Sam Bankman Fried of FTX being arrested, our impression is this is another prominent leader who has gone rogue. However, my research with Navdeep Arora on white collar inmates in a United States Federal Prison suggests an uncomfortable truth: our behaviours stem from our personal circumstances, the organisational culture in which we work as well as the wider regulatory and industry environment in which we operate. It is the layering of these three levels: the individual, organisational, and environmental that escalates the risk for individuals to act unethically and unlawfully and succumb to reputation damage.

All organisations and leaders face various forms of reputation damage.

“While character and capability reputation play an important role in how others make judgments about us, they are also limiting because they are both based on our past actions.”

Instead. our contribution, how we propose to provide value to others in the future, is an important part of the recovery process. Different stakeholders may not like what you or your organisation has done in the past, but their future interaction will depend on their perception of and willingness to let you provide value for them in the future.

Having no engagement with reputation is a risky strategy because you run the risk of letting others control the narrative, whether you are a CEO trying to persuade investors or a politician attempting to send positive signals to the electorate. An obsession with reputation causes problems as Billy Macfarlane found with the hype around the Fyre festival in the Bahamas with the social and mass media attention causing an over-confidence with his abilities and a disconnection from the reality of the situation, with catastrophic consequences for the event and him personally.

Some cautionary recommendationsBuilding on the evidence and examples from Reputations at Stake, I provide 10 cautionary recommendations for leaders. The reputation stakes are high and require all leaders to take collective responsibility, whether they are government or business leaders, managers, employees, volunteers, members of communities, or many of these. While reputation is not something to unduly obsess over, leaders must attend to reputation proactively and meaningfully. If managed effectively, our reputation can have positive and sustained outcomes for wider sets of stakeholders, future generations and our planet.

10 cautionary recommendationsProactive reputation management without over-engineeringEngaging with broader sources of information promotes innovative solutionsFeedback from different stakeholders makes us aware of the opportunities and risks related to our reputationsMultiple reputations recognises that different groups have a stake in your organisationShow tangible initiatives to demonstrate commitment to responsibility and give less vacuous statementsWork with others to support your reputation claimsAspire for building a positive reputation with multiple groups, but avoid preserving your reputation at all costsExternal events provide clues of areas that require change in your organisation’s purposeResponsible leadership can prove costly in the short-term, but will reap reputation rewards in the long-termReputation damage is a time of frustration and regret, but can mark a turning point for learning and bettermentFeature image by Jason Goodman via Unsplash (public domain)

July 7, 2023

Much ado about nothing? The US Supreme Court’s Warhol opinion

Much ado about nothing? The US Supreme Court’s Warhol opinion

Despite the title of this post, I am not a Shakespeare fan; far from it. My only interest in him is in the wonderful derivative works he inspired, such as Hector Berlioz’s opéra comique Beatrice and Benedict, and other derivative works based on Romeo and Juliet, such as Berlioz’s dramatic symphony Roméo et Juliette. Shakespeare also inspired Prokofiev’s ballet Romeo and Juliet and Felix Mendelssohn’s Overture to a Midsummer Night’s Dream. These last two works can’t be considered derivative works in the copyright sense because they don’t incorporate any of Shakespeare’s text, any more than Modest Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition can be considered a derivative work of the exhibition of works by architect and painter Viktor Hartmann put on at the Imperial Academy of Arts in Saint Petersburg that Mussorgksy takes us on a musical tour of. Richard Strauss’ Don Quixote is another example of a musical work inspired by another art form (there a novel), but which is not a derivative work because it does not contain any expressive material from the original. Artists have always inspired other artists and may it remain so forever, without copyright law interfering.

The right to prepare derivative works was at the heart of the United States Supreme Court’s 18 May 2023 opinion in The Andy Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith. Warhol had, under license from Vanity Fair, created an authorized derivative work of Lynn Goldsmith’s photograph of the Artist Formerly Known as Prince, for a magazine article about Prince. The license was for a one-time use only. After Prince (and Warhol’s) death, another magazine licensed a different colored version of Warhol’s adaptation of Goldsmith’s work, but without a license from her. The Foundation then sued Goldsmith for a declaratory judgment that it’s use was a fair use, and therefore not infringing. The trial court ruled in the Foundation’s favor, but the court of appeals reversed, ruling in Goldsmith’s favor.

“Is there any future guidance in the opinion about other fair use disputes? Yes, but not in the majority opinion.”

The Supreme Court agreed with the court of appeals, but on a very truncated review of just the first of the four factors, the nature and purpose of the use. This truncated review renders the opinion of limited future value, a conclusion fortified by the many references in the opinion to it being narrow. But the case isn’t entirely much ado about nothing. The Court rejected, authoritatively, the Foundation’s argument that transformativeness can be found in the derivative author’s subjective intent. The Court also showed solicitude for the original author’s right to authorize third party derivative works. In the end, though, the case came down to a conclusion, factual or not, that Warhol simply hadn’t changed enough of Goldsmith’s work, at least in the context of an unlicensed use for the same market. Since the Court left open the possibility that the same Warhol work might be fair if displayed in a museum, one does wonder why the Court took the case, since denying certiorari would have had the same result.

Future guidance for fair use disputesIs there any future guidance in the opinion about other fair use disputes, general guidance aside from a judgment that in this case Warhol didn’t change enough to escape the clutches of the right to prepare derivative works? Yes, but not in the majority opinion, but rather in Justice Gorsuch’s concurring opinion for himself and Justice Jackson. The central argument made by the Foundation was that the first factor’s transformative standard could be met by a subjective different purpose. The majority rejected this, relying on the Second Circuit’s analysis. Justice Gorsuch offered more:

Nothing in the copyright statute calls on judges to speculate about the purpose an artist may have in mind when working on a particular project. Nothing in the law requires judges to try their hand at art criticism and assess the aesthetic character of the resulting work. Instead, the first statutory fair-use factor instructs courts to focus on “the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes.” § 107(1) (emphases added). By its terms, the law trains our attention on the particular use under challenge. And it asks us to assess whether the purpose and character of that use is different from (and thus complements) or is the same as (and thus substitutes for) a copyrighted work. It’s a comparatively modest inquiry focused on how and for what reason a person is using a copyrighted work in the world, not on the moods of any artist or the aesthetic quality of any creation.

This makes perfect sense from a practical, evidentiary angle. Allowing subjective intentions to prevail would in cases such as Warhol’s be impossible since he said nothing about his purpose. Silence is just silence. In other cases, such as the appropriation artist Richard Prince, his purported purposes are many and contradictory, which is unhelpful to bench and jury trials alike. In the future then, fair use cases, at least involving appropriation art, will be simpler, with fewer experts waxing philosophically about deep subjective meaning, and the trier of fact simply comparing the objective appearance of the works. That’s a blessing.

Featured image via Unsplash (public domain)

The heavy burden of the past: the history of the conquest of México and the politics of today

The heavy burden of the past: the history of the conquest of México and the politics of today

The history of the conquest of Mexico by Spanish conquistadors in the sixteenth century remains a complex topic of discussion. Various interpretations have emerged throughout the years, each offering unique insights into this pivotal moment in Mexican history. Andrés Manuel López Obrador, Mexico’s president, has taken up the issue and uses it to promote his populist policy. What are López Obrador’s views on this historical event, considering his emphasis on indigenous rights, historical context, and the importance of reconciliation in Mexico?

Indigenous rights and empathyAccording to the supporters of the government, one crucial aspect of President López Obrador’s view on the Conquest revolves around his concern for the rights of Mexico’s indigenous populations. He acknowledges the suffering and displacement inflicted upon indigenous communities during the Conquest. López Obrador emphasizes the need to respect the rights, culture, and dignity of indigenous peoples today, highlighting the importance of rectifying historical injustices through governmental policies.

His followers appreciate that President López Obrador often emphasizes the significance of understanding the historical context surrounding the Conquest of Mexico and stresses the deep-rooted impact of Spanish colonialism on Mexico’s social, economic, and political structures, which persist to this day. By examining the broader historical context, he claims to foster a critical dialogue about the long-lasting consequences of the Conquest.

Reconciliation and nation-building“López Obrador emphasizes the need to respect the rights, culture, and dignity of indigenous peoples today.”

Another key aspect of López Obrador’s views on the Conquest is the importance of reconciliation and nation-building in Mexico. According to the president, healing historical wounds is crucial for fostering unity in the country. López Obrador promotes acknowledgment of the past, aiming to create a more inclusive society. He encourages an open examination of Mexico’s history, recognizing both its triumphs and its darker moments, such as the Conquest, in order to move forward as a nation.

Efforts towards reconciliationPresident López Obrador has implemented various initiatives aimed at fostering reconciliation and addressing the historical consequences of the Conquest. One such effort is the campaign to commemorate the 500th anniversary of the fall of Tenochtitlán, the Aztec capital. By highlighting the achievements of pre-Hispanic civilizations and acknowledging the resilience of indigenous communities, López Obrador seeks to honor their contributions and restore a sense of pride in Mexico’s rich cultural heritage.

Furthermore, his administration has taken steps to provide reparations to indigenous groups affected by historical injustices. These initiatives include financial compensation, land restoration, and the promotion of indigenous languages and cultures. López Obrador’s government has also prioritized infrastructure development in marginalized communities, aiming to address historical inequalities and improve the living conditions of indigenous populations.

Oversimplification of history“One of the primary criticisms leveled against President López Obrador’s views is the oversimplification of complex historical events.”

One of the primary criticisms leveled against President López Obrador’s views is the oversimplification of complex historical events. His narrative often presents the conquest of Mexico as a morally clear-cut clash between indigenous peoples and Spanish conquistadors, neglecting the diverse dynamics and complex interactions that shaped this pivotal period in Mexican history. By reducing the conquest to a simplistic dichotomy of good versus evil, López Obrador overlooks the nuanced political, social, and cultural realities of the time.

Historical anachronismAnother significant criticism of López Obrador’s perspective is the application of contemporary standards to judge historical events. It is important to acknowledge that the values, norms, and perspectives of the sixteenth-century differ greatly from those of the present day. While recognizing the atrocities committed during the conquest, it is crucial to avoid projecting contemporary moral judgments onto historical actors. President López Obrador’s approach risks disregarding the historical context and complexities that influenced the actions of both indigenous peoples and the Spanish.

Exacerbation of social divisionsPresident López Obrador’s views on the conquest of Mexico have also faced criticism for their potential to exacerbate social divisions within the country. By emphasizing a simplistic narrative of victimhood, he risks perpetuating a sense of grievance and fostering resentment between different ethnic and cultural groups. While it is crucial to acknowledge historical injustices, a balanced approach that promotes understanding, reconciliation, and national unity is necessary to address the complexities of Mexico’s history and the multicultural nature of its society.

Marginalization of indigenous agencyCritics argue that López Obrador’s narrative of victimhood often marginalizes indigenous agency and undermines the rich history of indigenous resistance, adaptation, and cultural preservation during and after the conquest. By portraying indigenous peoples solely as victims, he fails to acknowledge their resilience, cultural contributions, and role in shaping the Mexican nation. Such a one-sided portrayal overlooks the complexity of indigenous societies and their interaction with European colonizers, ultimately perpetuating a distorted understanding of Mexico’s history.

Diminished focus on contemporary challenges“Critics argue that López Obrador’s narrative of victimhood often marginalizes indigenous agency.”

By directing excessive attention to the conquest of Mexico, President López Obrador’s views risk diverting focus from pressing contemporary issues that require urgent attention, such as poverty, corruption, inequality, and violence. While historical reckoning is important, an excessive emphasis on the past can distract from addressing current socio-economic challenges. Critics argue that López Obrador’s approach to history risks neglecting the pressing needs of the Mexican people and hampering progress in areas that demand immediate attention.

President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s views on the Conquest of Mexico reflect his emphasis on indigenous rights and national reconciliation. By acknowledging the atrocities committed during the Conquest, he seeks to rectify historical injustices and build a more inclusive Mexico. Through his initiatives and policies, López Obrador aims to honor the contributions of indigenous communities, promote dialogue, and foster a sense of national identity that is rooted in both the pre-Hispanic past and the multicultural present. However, his policies also give rise to criticism which revolves around concerns of oversimplification, historical anachronism, the exacerbation of social divisions, the marginalization of indigenous agency, and the potential neglect of contemporary challenges.

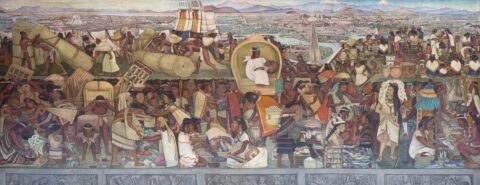

Featured image by Diego Rivera, via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers