Oxford University Press's Blog, page 51

May 18, 2023

Bringing museum collections to life

Bringing museum collections to life

“Would you have a dried specimen of a world, or a pickled one?”

On 24 September 1843, the writer and naturalist Henry David Thoreau recorded a fairly long critique of natural history museums in his journal. Best known for Walden (1854) and other environmental writings, it is not entirely surprising that Thoreau would have mixed feelings about museums, where plants, animals, and other objects were being rapidly accumulated to serve the study of science. “I hate museums,” he wrote. “They are the catacombs of nature…They are dead nature collected by dead men.” Describing a visit to the Boston Society of Natural History (the predecessor of the Museum of Science in Boston), he noted only a sense of detachment: “I walk amid those jars of bloated creatures which they label frogs, a total stranger, without the least froggy thought being suggested.”

Thoreau’s reflections are especially noteworthy as we mark International Museum Day this month. The International Council of Museums (ICOM) has declared a focus for 2023 on sustainability, well-being, and community. Noting the significant position of museums “as trusted institutions and important threads in our shared social fabric,” ICOM emphasizes their “transformative potential” for shaping larger conversations about climate change, global health, and other pressing issues. This year’s International Museum Day marks an opportunity, in ICOM’s words, to imagine the possibilities that museums can play “in shaping and creating sustainable futures.”

We can better understand what it might take for museums to create such futures by looking more closely at their past. The earliest museums were the cabinets of curiosities owned by early modern collectors. Often the product of an individual’s distinct interests, they included “natural and artificial curiosities” such as natural history specimens, works of art and other printed materials, and anthropological objects. During the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, many early museums continued this vision, bringing together numerous kinds and categories of objects with the goal of promoting “useful knowledge” through the study and close examination of collections. The cases and cabinets filled with objects increasingly represented knowledge itself, seen in visual and tangible form. Their founders emphasized the value of studying material objects as a way to learn about numerous subjects. They imagined the “spark” that might result from studying objects, the new ideas that could emerge, and the exciting possibilities of placing different objects—and the minds of observers—in conversation.

“Thoreau’s dilemma highlights the ongoing question about how to use museum collections to explore and better understand our surrounding world.”

Around the time that Thoreau was professing his hatred of natural history museums, these institutions were undergoing major shifts in their purpose and scope. Some museums were moving in the direction of emphasizing education and expanding public access. Nonetheless, this was a fairly slow and somewhat mixed process. Many objects in museum collections were the direct result of colonial ventures and systems of exploitation, theft, and violence around the world. Labeled as “curiosities” by white collectors, they were used to promote inaccurate information and racist misconceptions. Even when museum galleries opened to a wider public, the authority to interpret objects still rested with elite white men. It was during this period that the term “scientist” was first coined, reflecting growing disciplinary specialization and professionalization within the scientific community. Nonetheless, many collections continued to combine numerous fields, bringing together works of art, natural history, anthropology, and more. Museums were undergoing a process of transformation, but it remained incomplete and reflected an uncertain future for these institutions.

Wandering amid the “jars of bloated creatures” in a museum gallery, Thoreau was not as distant from these collections as he claimed in writing. He donated numerous specimens to the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University and the Boston Society of Natural History, including fish, turtles, and birds’ eggs. He struggled with the ethics of his own scientific practices, seeking to balance between the close observation and “useful knowledge” afforded by stilled specimens and his preference for observing a living creature. In his journals, he often recorded lengthy descriptions of the turtles living near Walden Pond, marveling at their appearance and making detailed notes about their behavior. In addition to these writings, however, a turtle that he donated to the Museum of Comparative Zoology still remains suspended in alcohol in a glass jar, much like those he observed during his own visits to museums. Taken together, his writings and specimens show how he wrestled with different modes of studying his surrounding environment, recording his observations, and participating in broader scientific practices throughout his career.

As museums today look to expand their commitments to sustainability, well-being, and community, we can look to their history to understand both the challenges and possibilities of the work that lies ahead. Thoreau’s dilemma highlights the ongoing question about how to use museum collections to explore and better understand our surrounding world. At the same time, his criticisms perhaps unexpectedly reflect the kind of “spark” that museum founders once hoped to see resulting from the accumulated knowledge in their collections. Then and now, visitors to museums continue to play an important role in advocating for ethical practices and drawing connections to contemporary issues. As museums today imagine transformative change, they might continue to look to their own communities to participate in these broader conversations. In this way, “a dried specimen of a world” can continue to take on new life.

Feature image: London Natural History Museum by Kafai Liu. Public domain via Unsplash .

May 17, 2023

On cowards and custard from a strictly linguistic point of view

On cowards and custard from a strictly linguistic point of view

It is curious what a multitude of synonyms for “brave” Modern English has (bold, courageous, valiant, fearless, and at least a dozen more), while coward ~ cowardly have practically none. For coward only a few rather unexciting nouns like poltroon and dastard turn up, and for the related adjective we chiefly find compounds like chicken-hearted and faint-hearted. It appears that language endows courage with many shades, while cowardice has only one hue. Such picturesque metaphors as scaredy-cat and milksop don’t count.

The origin of coward is known, and I’ll say nothing about it that cannot be found elsewhere, but the story will take us to other, more interesting words. The strangest thing is that coward, a single common name in English for a person lacking fortitude, is a borrowing from Old French. Where, we would like to know, is the Germanic coward lurking? We’ll discover that ignoble person later but will first note that people seem to have resented this lack of native, grassroots diffidence and mobilized folk etymology to fill the gap. Time and again, coward has been explained as an alteration of cowherd. Why should cowherds be or have been prototypical cowards? The silliness of this derivation did not bother its proponents. Folk etymology seeks an easy explanation rather than logic. The same approach to word origins connected coward with the verb cower, but neither cower nor incidentally, the verb cow has anything to do with coward, even if cower may have reinforced the meaning of our noun.

A cowherd is not a coward!

A cowherd is not a coward!Photo by WBRA Jen via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

The source of coward is Old French couard, ultimately, from Latin coda “tail.” In the immensely popular and beautiful poem Reynard, The Fox, translated into Middle English from Old Flemish by the great William Caxton (1415-1490), the hare is called Cuwaert and Kywart. Perhaps the original allusion was to a frightened dog with its tail between its legs. It has also been noted that in heraldry, a lion with its tail between its legs, called couard in Old French, has the depreciating suffix –ard and means “having a short, drooping, or otherwise ridiculous tail.” The reference to the tail is sometimes called obscure, but on the whole, the existing explanation is not bad. As for the suffix, which we can see even in the name Reynard, it also occurs (among others) in drunkard, dotard, sluggard, and the already mentioned dastard.

Now back to the Germanic coward. We find him in German and Scandinavian: German feige and Dutch veeg mean “cowardly,” while Old Icelandic feigr means “doomed, fated, destined to die.” In Modern Norwegian, Danish, and Swedish, the cognates of feigr mean “fearful; unusual; crazy,” but this change happened under the influence of German. The sense in Old Icelandic is the original one. In German, the transition from “doomed” to “cowardly” went through several stages, one of which was “hated.” The distant origin of our word is unclear and need not bother us. I should only note that the most usual Indo-European root cited in this connection looks unconvincing. The development must have been from “doomed to die” to “afraid of death.” Perhaps one of the intermediate stages was “ready to die.” In some southern German dialects, the related adjective means “almost ripe” and “rotten.” The most ancient root may have had that meaning, as suggested long ago but dismissed by later scholarship without discussion. And this brings us to English fey “fated to die,” an exact cognate of German feig(e), Dutch veeg, and Old Icelandic feigr, now and for many centuries, chiefly Scottish. Such is one of the verbal sources of Germanic fear.

This is Reynard.

This is Reynard.Image by Ernest Henri Griset, via Wikimedia Commons (public domain)

Yet it is not the only one. German Angst “fear” has made its way into English dictionaries, along with the untranslatable Zeitgeist and Schadenfreude. The word, whose specific meaning goes back to Freud, is at least a century old in English, but it still exists only as a synonym for “anxiety.” Itis related to German eng “narrow” and a host of words outside Germanic. When you find yourself in a narrow spot, you experience anxiety, you are afraid. This etymology highlights the development of abstract concepts from concrete ones, about which more will be said below. Here we will only note that the root of Angst can also be seen in anger, anguish, angina, anxious, agnail (!), and so forth. The related words in Greek and Latin sound almost like those in Germanic, and we recognize their English offspring without any trouble.

Fear is also a Germanic word. Its Old English source meant “sudden calamity; danger.” Its cognate in Old Saxon (another West Germanic language) turned up with the sense “ambush.” By contrast, “danger” is the only meaning of Modern German Gefahr and Dutch gevaar. Our knowledge of the subtler meanings of words in the oldest texts is imperfect, because we depend on a limited number of contexts and on occasional, often untrustworthy Latin glosses. Even though such a rigorous semantic law does not exist, it makes sense to assume that abstract senses tend to be derived from more concrete ones. In our case, “ambush” (a source of fear) may have developed into “danger” and “fear.” Yet our material is too scanty for bold generalizations. Though great perils awaited a traveler (ambushes, highwaymen, inhospitable terrain), English fare and its numerous congeners, including German fahren, are not related to fear, because the noun fear had a long vowel in the root, while the vowel in fare and the rest was short. Such niceties did not bother our oldest scholars, but all modern etymological research depends on them.

Here then is a short summary of what we have found. Cowards, those mean-spirited, pusillanimous people who treasured their lives more than the common good, have always existed, but the oldest Germanic words for the lack of bravery seem to derive from the ideas of being fated (doomed, destined) to die. When French words for the spiritual sphere flooded Middle English, the native nouns designating the lack of courage were lost, and coward, a loan from Old French, replaced them. However, fear, an old word, survived, though its original meaning was more concrete, namely, “calamity” or perhaps “accident.” German Angst preserves its status of a foreignism in English, but fear is native and thus makes amends for the imported word coward.

Custard, a repast for the timid.

Custard, a repast for the timid.Image via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

For dessert, I would like to quote the phrase cowardly, cowardly, custard, an alliterative taunt used by boys and reported in 1872 in the biweekly Notes and Queries by a correspondent from Philadelphia. He wrote: “It is supposed to have its origin in the shaking, quivering motion of the confection called ‘custard’. In Microcosmos (1687) [by Johann Martini], Act iii, Tasting says “I have a sort of cowardly custards, born in the city, but bred up at court, that quake foe fear.” The date of the OED’s earliest citation of the phrase is 1833. The explanation given in 1872 seems to be correct: a quivering heart has always been associated with cowardice. In an Old Icelandic poem from the Elder Edda, one of the heroes sees a heart, allegedly cut out of the breast of his brother, but gives the messenger the lie: the heart is quivering. And indeed, the heart belongs to a cook. Then they kill the brother, whose heart looks right! My questions is obvious: Does any of our readers know the taunt? If so, where is it still used?

Featured image: “Two Jack Russell terriers chasing a rabbit into a burrow”, Wellcome Images via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 4.0)

May 16, 2023

Rethinking the future of work: an interview with Adrienne J. Colella and Eden B. King

Rethinking the future of work: an interview with Adrienne J. Colella and Eden B. King

Introducing the editors of The Oxford Handbook of Workplace Discrimination: Adrienne J. Colella is Professor and the McFarland Distinguished Chair in Business at Tulane University, and Eden B. King is Associate Professor of Industrial Organizational Psychology at George Mason University. Their work synthesizes research across psychology, sociology, and management, and inspires a new era of scientific practice on understanding and reducing workplace discrimination.

Adrienne and Eden share their insights on workplace discrimination and the future of work.

What can organizations do to tackle workplace discrimination?Workplace discrimination cannot be eradicated by a single policy or process. Instead, organizations need to develop strategic, comprehensive initiatives that cut across levels, units, and talent management cycles. Aligned with such strategy, leaders need to be visibly committed and held accountable to diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). Ongoing transparent assessment and accountability for DEI will help to ensure positive change. Finally, organizations need to create and sustain a culture where respect, empathy, and justice are core values.

How can academic research practically reduce discrimination within organizations?“Leaders need to be visibly committed and held accountable to diversity, equity, and inclusion.”

Academic research can help to inform practice by providing robust evidence regarding the unique experiences of people who face discrimination as well as the strategies that are most effective in addressing these issues. In other words, good science can inform good practice.

How do we develop and support the next generation of leaders in a more remote world?Leader development requires the opportunity to engage in a variety of challenging tasks and to receive feedback about performance. The specific nature of the experiences, and the ways in which feedback is transmitted, are constantly evolving with technology and the environment. At the core, then, leader development will be the same—challenging tasks and feedback—but the conditions will evolve. It is yet to be seen whether the nature of leadership and the traits and behaviors which make leaders effective will also change in a more remote world.

How does increased flexibility impact employees and organizations?Like most things, the increase in remote work has both positive and negative implications. On the positive side, many people have found flexibility for opportunities to engage with family and leisure activities. In addition, people with disabilities and chronic health conditions have found better access to work. On the negative side, however, remote work can create challenges for human connections, increase loneliness, and blur the lines between work and home in a manner that is exhausting. And, of course, many types of work (especially low wage jobs) cannot be done remotely, potentially exacerbating socioeconomic divides. Experience and evidence in the upcoming months and years will help us understand for whom, how, when, and where flexibility can yield the most positive effects.

What do you think the world of work will look like in 10 years?Given the rapid, unexpected changes we have experienced in the last few years, this question is really difficult to answer. We expect that rapid advances in technology will come with both unforeseen advantages and disadvantages for employers and employees and that the notion of “going to work” will change. Beyond this, we can’t predict.

Feature image credit: Canva

May 15, 2023

American evangelism and complementarianism: authority and abuse

American evangelism and complementarianism: authority and abuse

In early February 2023, evangelical Twitter was abuzz with a bombshell news story in Christianity Today. In the article, journalist Kate Shellnutt described megachurch pastor John MacArthur and his Grace Community Church as repeatedly dismissing the concerns of women in abusive marriages, sometimes threatening the women (implicitly or explicitly) with church discipline if they did not return to their abusive husbands or if they reported the abuse to the police. The story was a bombshell because MacArthur is, as Shellnutt described, “one of America’s longest-standing and most influential pastors.”

While Shellnutt’s article exposed long-term practices at MacArthur’s church, the case shared significant similarities with news stories from the previous year about the Southern Baptist Convention—at nearly 14 million members, the nation’s largest Protestant denomination. In a May 2022 story for the New York Times, Ruth Graham and Elizabeth Dias reported that a third-party investigation found Southern Baptist leaders had “suppressed reports of sexual abuse and resisted proposals for reform” for more than two decades. The independent investigation also documented “a pattern of intimidating survivors of sexual assault and their advocates.” Making matters even worse, the report revealed that for a decade denominational staff had kept a detailed list of ministers and other church workers accused of sexual abuse, yet no action was taken to ensure that the accused were not in positions of power at Southern Baptist churches.

“Complementarianism is an evangelical theology that… men are created to lead… and women are created to submit to men’s authority.”

Reports of abuse in both John MacArthur’s non-denominational megachurch and the Southern Baptist Convention can be linked to their shared complementarian theology. Complementarianism is an evangelical theology that men and women are created by God to serve different ends. While men and women are equal in worth, they are designed by God to fulfill distinct roles: men are created to lead in the church and home, and women are created to submit to men’s authority in both spheres.

In researching and writing Making Christianity Manly Again: Mark Driscoll, Mars Hill Church, and American Evangelicalism, I encountered stories of women who blamed Mars Hill Church’s complementarian theology for their husbands’ abuse in stories very similar to the reports of Grace Community Church and the Southern Baptist Convention. Mars Hill Church’s infamous pastor, Mark Driscoll, was a strident complementarian, who described himself as an “intense biblical literalist who believes that the man is the head of the home, that the man should provide for his family. . . and that we would not have so many deceived feminists running around if men were better husbands and fathers because the natural reaction of godly women to godly men is trust and respect.”

Members of complementarian churches firmly believe the theology of God-designed differences for men and women. For many, complementarian theology is a successful strategy to define roles and the division of labor within church and home. For some, however, the prescribing of authority to men and submission to women can result in men misusing their authority to keep women in line, resulting in abuse. Sometimes women interpret abuse as a corrective to their not being submissive enough.

“[T]he prescribing of authority to men and submission to women can result in men misusing their authority to keep women in line, resulting in abuse.”

Some women at Mars Hill Church reported that the church’s complementarian theology had led to boyfriends’ or husbands’ abuse. One woman I interviewed, Anna, reported that as she and her husband experienced infertility, their marriage faltered with her husband becoming physically abusive. Anna told me that when she sought counseling at Mars Hill, church policy at the time required permission from husbands before women could see an elder or counselor. After a concerned friend stepped in to make an appointment for her, Anna met with an elder who was supportive, telling her she couldn’t go back to her abusive husband. Anna told me this was the first time she realized she had been submitting herself to abuse because she believed that was what she was “supposed to do.” Unfortunately, Anna was later counseled by different church elder to return to her abusive husband. Anna eventually divorced her husband and left Mars Hill, feeling that church members (her friends and family) judged the failure of her marriage as a failure of faith.

Like Anna, the women interviewed for the Christianity Today article on John MacArthur and Grace Community Church considered themselves, at some point, to be “partly responsible for their husband’s behavior or had a church leader indicate they were.” These women reported being “reminded of the biblical directive for wives to submit to their husbands,” as a reason for reconciling and returning to their homes, even when they “feared for their safety and the safety of their children.”

Like other complementarians, Driscoll adamantly preached against husbands abusing wives, just as MacArthur preached “against women staying with abusive husbands,” as have many Southern Baptist preachers. Yet a theology that gives men power over women can lead to mixed messages, with men using their authority in abusive ways and women denying or minimizing the abuse as an expression of men exercising their authority. The research and reports on Mars Hill Church, Grace Community Church, and the Southern Baptist Convention illustrate the entrenched nature and dysfunction inherent in American evangelicalism’s complementarian theology.

Featured image: Grace Community Church Sun Valley building, public domain via Wikimedia Commons .

May 12, 2023

An inflation-proof methodology to measuring policy effects on poverty

An inflation-proof methodology to measuring policy effects on poverty

Europe’s soaring inflation and energy prices highlight the need to measure poverty and policy responses in non-monetary ways.Hard times continue for those on tight budgets in Europe and elsewhere. Despite the end of COVID-19 lockdowns and a return to a new normal economy, soaring prices for necessities such as food, housing, and energy are eating up the purchasing power of households’ incomes with every purchase and bill payment.

Non-monetary indicators of poverty such as the European Union’s (EU) Material and Social Deprivation (MSD) indicator are exceptionally well suited to register the pinches and punches delivered to the purchasing power of households with relatively low resources and/or high needs.

The MSD indicator measures whether households cannot afford items that are considered by most people to be necessary for an adequate living standard. Examples of items are a household’s financial ability to keep their home adequately warm, to have two pairs of properly fitting shoes for every member, and to have an internet connection. A household and its members are considered deprived when they cannot afford 5 out of 13 such items.

The EU’s official income poverty indicator cannot capture the effects of the current crisis on households’ living standards. This is because inflation and soaring energy prices decrease consumption, not income.

During the consecutive crises hitting Europe between 2007 and 2012, the MSD indicator already proved its use registering marked increases in material deprivation and, as recovery took hold, accounting for the lion’s share of the EU’s improvement towards its 2020 social inclusion target.

The MSD indicator will therefore again be the center of political attention and it will show which households are hit hardest. When households cannot influence their income enough to make up for lost purchasing power, rising costs will force them to choose between necessities, which is exactly what the MSD indicator measures.

“The EU’s Material and Social Deprivation (MSD) indicator is exceptionally well suited to register the pinches and punches delivered to the purchasing power of households.”

However, whereas measuring the effect of policies on households’ income is routine practice in governments and among researchers and interest groups, the same does not hold for assessing the effects of such policies on material deprivation.

It is a problem when potentially substantive policy effects are going unmeasured because it could lead to less support for those in need and thus less progress on the reduction of poverty and social inclusion overall. For instance, when policies appear more costly relative to their beneficial effects, decisionmakers may not find them worthwhile of pursuit. Or policies may benefit certain groups in need (e.g., those with a low income) while excluding other groups with similar or higher needs (e.g., those with a higher income and higher needs). Or policies that have a measurable effect on income poverty may appear more effective than policies that reduce the need for households to spend money out of pocket.

A reason why policy effects on material deprivation have gone unmeasured is that, despite the rising use of material deprivation indicators, there was no established methodology to measure such effects. A recently published study showcases a new methodology that estimates the effect of a small increase in income on material and social deprivation in 32 European countries.

The study quantifies the impact of a small universal income transfer and shows that the transfer’s effect is considerably higher in the most deprived countries and among the most deprived persons in a country.

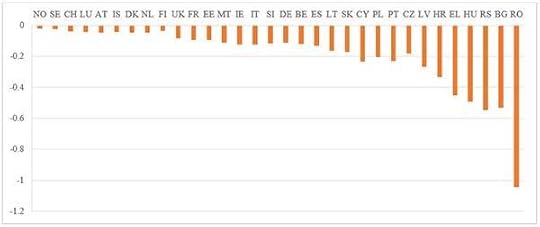

Figure 1 below shows that a very modest transfer of 150 Euro per year, adjusted for differences in purchasing power across countries (PPS), would contribute to reducing MSD rates across Europe. The reductions are sizeable for countries with lower average living standards, with the largest reduction of one percentage point in Romania.

Figure 1: Impact of a universal 150 (PPS) transfer on the social and material deprivation rate, in percentage points

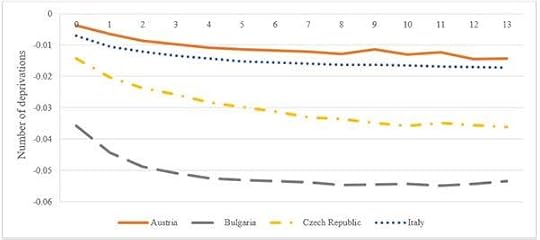

Figure 1: Impact of a universal 150 (PPS) transfer on the social and material deprivation rate, in percentage pointsFigure 2 below furthermore shows that the same transfer has a bigger difference for those households experiencing more deprivations in each country. The average marginal effect (AME) of the transfer reduces the average number of deprivations among households experiencing one deprivation is 0.02. It is 0.03 for household experiencing five deprivations. This effect is present in all countries, regardless of their living average standard.

Figure 2: Impact of a universal 150 Euro (in PPS) transfer on the number of deprivations, by (observed) deprivation level, selected countries

Figure 2: Impact of a universal 150 Euro (in PPS) transfer on the number of deprivations, by (observed) deprivation level, selected countriesThese results demonstrate that progressiveness should not just be thought of in terms of income, while also underlining the importance of a progressive social transfer system everywhere.

The same research shows that the impact of extra income depends on the type of social transfers received. Compared to households not receiving transfers and those receiving pension transfers, those in receipt of non-pension transfers, on average, experience the largest decrease in the number of deprivations in Europe. Non-pension transfers include transfers such as child benefits, housing allowances, social assistance, and unemployment or disability benefits. In some Eastern European countries, however, those receiving pensions or both pensions and non-pension transfers also benefit more than average. Such results inform which parts of the social safety contribute to reducing material deprivation and where additional transfers are likely to make the biggest difference.

The methodology developed in this study can be applied to many microdata contexts, including microsimulation datasets. A non-linear regression technique estimates the relation between the number of deprivations and predictor variables such as income, debt burden, and other household characteristics. The methodology can be used to predict effects of potential policies, as was done in the above-mentioned study. It can also be used as part of multivariate techniques that evaluate the effects of policies implemented.

In the context of the current affordability crisis, European countries have implemented policy packages involving measures such as income support, social tariffs, in-kind support, and a cap on energy prices. As many of these measures work either through increasing income or reducing expenditures, they have a “money equivalent” value. Using that monetary value, the new methodology enables estimating the effect of such measures on social and material deprivation.

Finding out by how much such policies reduce poverty and social exclusion, who benefits (most), and by how much is an extremely relevant research effort in a policy context in which there is limited scope for expansionary fiscal policy. And now it is possible to do so.

Read the journal article in Socio-Economic Review: “Reducing poverty and social exclusion in Europe: estimating the marginal effect of income on material deprivation”

Featured image: Anna Dziubinska on Unsplash (public domain)

May 10, 2023

Etymology gleanings for April 2023

Etymology gleanings for April 2023

Since my previous attempt to glean on a half-frozen field, I have received quite a few letters and suggestions. All of them deserve a response. But first, as always, let me thank our correspondents for consulting the blog, asking questions, and offering words of encouragement.

Hook, hookers, and all, all, allSince my subject was hooker “prostitute,” I stayed away from the other senses of the word. Therefore, I apologize to the correspondent who excels in rugby, calls himself a proud hooker, and found nothing about the game in my post. I share his pride, feel his pain, and have two things to say. First, a hooker is obviously anyone who wields a hook. In fishing, for example, a hooker is distinguished from a netter, and of course, a hooker is a filcher, as explained at length in my post. Consider also hook it “to make oneself scarce,” discussed at some length in my recent dictionary of idioms. As to hockey, yes, the word may be related to hook, but some details are obscure.

Another observation concerns the impact of words related to the sexual sphere on their sources. Obviously, gay “homosexual” is an extension of gay “merry, etc.” The development of the now prevalent sense has been traced in detail, but what matters is that gay “homosexual” killed all the other senses. I once noted that in A. T. Hatto’s splendid English translation of The Lay of the Nibelungen, gay (that is, richly dressed) knights appear with great regularity (this usage was already known to Chaucer), much to the amusement of my undergraduate students. The same happened to queer. In the mid-1950s, I learned and was puzzled by the word because of my lifelong admiration for Oscar Wilde’s works. The phrase snobs queer caused the 1894 trial. Was it possible anywhere in the English-speaking world to say in 1957 “what a queer (= odd, quaint, bizarre) dress,” without making the interlocutor blush or giggle? Many older people can undoubtedly answer this question. The same happened to proud hookers, alas! Today even hooker “ship” is funny. On the other hand, only forty years ago, it sucks was taboo, and now my computer, this precocious child of artificial intelligence, stubbornly suggests three answers to every letter I receive and lists this variant as an expression of my indignant disapproval. Cool!

Gay nights galore.

Gay nights galore.By Barthélémy d’Eyck, 1460, Bibliothèque nationale de France, via Wikimedia Commons (public domain)

As for filch (see the post Prolegomena to the word hooker for 19 April 2023), the connection with filchman is obvious, and that is why I referred to Jamieson. The putative Romany etymology of filch is also well-known. But it is far from clear whether the Romany word is not a borrowing of the cant of English thieves. And this brings us to the serious question of alternate hypotheses of word origins. I was asked what I think of the derivation of the adjective secure. Latin had sēcūrus and apparently, sicurus, because the latter was taken over by the speakers of Old English as sicor (Modern English sicker is dialectal, but compare German sicher “certain,” from sihhur). Could the English word be borrowed from a similar-sounding Greek one and be traced to a cognate of Latin sīcut “like” and understood as sic-urus? When there is a secure explanation, why look for another one? How is the vowel length in sīc– to be explained away, and what is –urus? Our correspondent borrowed his etymology from someone who, apparently, had little exposure to historical linguistics. People not versed in etymology often have good ideas about the origin of slang, technical terms, puzzling idioms, and the like, but the history of old words is a special subject, and guesses about their past are seldom, if ever, profitable.

Troll, trawl, and their likesTrawl has traditionally, even if with reservations, been derived from Latin trahere “to draw.” All the senses of troll (“move about; roll; sing in full round voice”) may be related. The difficulty is that tr– and dr– verbs are often either sound-imitative, sound-symbolic, or both (compare trip, drip, trap, trickle, tread, tremble, trample, trill, drill, drawl, droll, drool, and so forth). This means that all of them might emerge in their respective languages independently of one another or influence their look-alikes, or serve as their sources, or be borrowed. Perhaps trawl has been borrowed or coined more than once with vaguely the same meanings. As regards the verb troll, the existence of stroll complicates the picture, and we wonder: is stroll a variant of troll with so-called s-mobile, mentioned in this blog more than once (a ubiquitous prefix without a clear function)? There is no way to answer this question, because we always face possible, even probable, but not definite solutions.

Notes on some idioms In a sound-symbolic tizzy.

In a sound-symbolic tizzy.Image by Robert Higgns via Pixabay (public domain)

What is tizzy, part the phrase in a tizzy “in a state of agitation”? Given such a funny word as tizzy, it is almost natural to refer to it as an expressive coinage and to stop wondering about its origin. Compare drizzle, sizzle, swizzle “a frothy (!) intoxicating drink,” and fizz ~ fizzle. Once, tizzy also meant “sixpence,” apparently, an alteration of tester, itself an alteration of teston (the same meaning). Tizzy is a word easy to coin (the pun and half-rhyme are not intentional). There once was the word tuzzy-muzzy “a nosegay.” Dialectal tuzzy means “a tuft of hair” and must be related to touseled, which has respectable relatives but seems to be a member of the same group. The fuzzy Tootsie-Wootsie is also close by.

Can step change “a significant change” be an alteration of sea change? Similarly, can thin as a rake be an alteration of the much more transparent phrase thin as a rail? In the absence of recorded intermediate stages, this type of reconstruction leads nowhere. Also, in connection with rake, our correspondent noted that the Hebrew for “rake” is a word spelled with the consonants resh-het-tof. If rake is of sound-imitative or sound-symbolic origin, then the combination r-h ~ h-r looks natural, but, as always, sound imitation is absolutely obvious only in cases like blah-blah and barf–barf.

Sliding down in a handbasket to hell, I agree, is easy to visualize. It is the ascension to heaven by the same vehicle that remains a puzzle. What is the means of transportation? I asked our readers whether anyone could make sense of the phrase five miles to hell, where Peter pitched his waistcoat. The puzzle has not been solved, but one of our correspondents remembered an old man saying out where Jesus lost his sandals. This image makes more sense! Finally, I received a query whether I have any dirty idioms in my book. Alas, no! In the journals I screened for Take my Word for It, almost everything was prim and proper: in those days, smut and profanity were not allowed in print. The samples sent to me are a delight, but I dare not share them with the readership of this blog. In our speech, we are so squeamish, are we not?

Odds and ends This is a tuzzy-muzzy, is it not?

This is a tuzzy-muzzy, is it not?Photo by Karolina Grabowska, via Pexels (public domain)

Did both ever refer to more objects than two? No. Bo– in both has cognates in and outside Germanic and has the same meaning everywhere. I believe that in the phrase both Father, Son and Holy Ghost through all eternity, Father and Son was taken for one unit. I am also grateful to another reader who pointed out that the word sib is very much alive in the genetic community and means “sibling” in the speech of its practitioners. And one more. A teacher wrote me that explaining a spelling rule by reference to history is often helpful. I agree. We have rite, right, write, and wright. While dealing with an advanced learner who wonders why English has four written images for the same phonetic unit, a glance at the past may be valuable. But the problem is that spelling is taught (or should be taught) at an early age, and we cannot delve into the history of English while dealing with children. In explaining the spelling of Kate, cat, car, and care, history is good for dessert but not as the main dish.

Once again: please send me questions and notes, and I’ll do my best to comment on them in my gleanings.

Featured image by quintinsmith_ip via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 2.0)

May 9, 2023

How well do you know your twentieth-century literature? [Quiz]

![How well do you know you twentieth-century literature? [Quiz] - OUP blog](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1683741484i/34238769.jpg)

How well do you know your twentieth-century literature? [Quiz]

From James Joyce to Virginia Woolf, the first half of the twentieth century was a fascinating time for poetry, prose, and drama—but how well do you really know the writing? Try our short, fun quiz to test your knowledge on some of the period’s prominent writers, and you may just find some new texts for your to-read list!

Which epic poem does James Joyce's Ulysses most prominently allude to?The OdysseyThe IliadThe AeneidThe Divine Comedy"Yes, of course, if it's fine tomorrow," are the opening words to which Virginia Woolf novel?Mrs DallowayOrlandoTo The LighthouseThe WavesWhat is the name of the central character in Dorothy Richardson's Pilgrimage novel sequence? Molly BloomSeptimus SmithMadame SosostrisMiriam HendersonIn what year was Joseph Conrad's Nostromo published?1930192419041912"A Game of Chess," "The Fire Sermon," and "What the Thunder Said" are titles of parts from which poem?The Waste Land (T. S. Eliot)Paterson (William Carlos Williams)The Cantos (Ezra Pound)Observations (Marianne Moore)You can explore more authoritative twentieth-century texts with the latest releases from Oxford World’s Classics and Oxford Scholarly Editions Online:

Introducing the new twentieth-century literature module from Oxford Scholarly Editions Online, exploring seminal poetry, prose and drama from the period. Launching with six exciting titles from renowned authors such as James Joyce and Dorothy Richardson, this new twentieth-century module will provide trustworthy, annotated primary texts for scholars and students alike.For over 100 years, Oxford World’s Classics has brought readers closer to the world’s greatest writings, which is why we are excited to announce the expansion of its offering to early twentieth-century texts. Covering a range of influential pre-1928 writing, these new titles will support readers by providing comprehensive introductions, clear explanatory notes, chronologies, and bibliographies in every book.Discover more of our twentieth-century texts →

Featured image by Alex Block (@alexblock) via Unsplash (public domain).

May 7, 2023

What does a technical writer do?

What does a technical writer do?

When people think about careers in writing, they may focus on writing novels or films, imagining themselves as the next Stephen King or Sofia Coppola. They may aspire be a poet like Tracy K. Smith or Ada Limón. They may lean toward non-fiction, aiming to become an author like Jill Lepore or Louis Menand. But for steady work, there is nothing like technical writing for science, medicine, manufacturing, finance, retail, and other specialized fields.

According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, there are more than 55,000 technical writing jobs in the US, projected to hit 59,000 by 2031. And while there are advanced certifications available in specialty fields and even master’s degrees in technical communication, technical writing is a career path open to writers with undergraduate degrees in English, communication, linguistics, and related fields. It usually helps though to have some experience in design, business, science, or technology.

What do technical writers do?Technical writers prepare instruction manuals, guides, technical articles, descriptions, posts, and documents for all manner of processes, products, and procedures. One student of mine working as an intern said that her first task was to write instructions for packing jars of peanut butter in shipping boxes. Another developed a safety manual for a supermarket’s deli kitchen. A third got assigned to explain procedures for using water softeners and filtration systems. And I once worked for a time documenting an automated query system for real estate listings.

When I’ve invited career technical writers to visit my classes, they’ve shared some of the work they do at any given time. They’ve written clinical evaluation reports and protocols in the medical field and instructions for financial and business systems and software. They have written explanations of how environmental data is collected and analyzed and procedures for compliance with federal and state regulations. One rewrote hospital incident reports to make sure they were understandable to staff and insurers. Another developed a design proposal for an event venue. The writing itself is tremendously varied.

A writer friend once told me, “A lot of writing is not writing,” meaning that there was more to it than words on paper. That’s certainly true for technical writing. Research and consultation are large parts of the technical writer’s work. Figuring out the needs of the users takes time, curiosity, and perseverance. Technical writers consult with designers, developers, managers, technical staff, and end-users to understand the products or processes involved. They may be responsible for recommending the most appropriate medium and design for materials and for ensuring that content is uniform across various modes of delivery.

Some technical writers may also be responsible for collecting and analyzing user feedback and usage patterns. And they may work as technical editors for projects developed collaboratively or drafted by others: scientists, clinicians, programmers, and engineers may not be familiar with writing for the general public or for their end-users.

At times, technical writers can also find themselves doing some feature writing in addition to the technical bread and butter. A writer might profile staff members explaining their work and write newsletter, blog, or magazine copy to tell the backstory of a new discovery, promote an innovative product, or explain a live-saving procedure.

Our fiction-writer colleagues like to remind us that “all writing is creative writing.” If you enjoy research and can write clearly, technical writing may be the place to put your creativity to work.

Featured image by Amy Hirschi via Unsplash (public domain)

May 3, 2023

A riddling tale

This is not a mystery tale, but a few twists in the history of the word riddle are worthy of note. Riddles, it should be noted, played and play an outstanding role in world culture. To win a bride, suitors had to offer or solve an insoluble riddle, as happened, for example, to Samson and Turandot. Forever memorable is the riddle of the Sphinx. According to an Old Norse myth, when the shining god Baldr was killed, Odin (that is, Óðinn) whispered something to his dead son on the funeral pyre. For a long time, the best Scandinavian antiquarians have been trying to guess what Odin imparted to his son, a task as profitable as chasing a rainbow or nailing a pudding to a tree (in an earlier post, I referred to a sleeveless errand). Baldr is dead, to begin with, and if Odin wanted the secret message to be known, he would have pronounced it aloud. In principle, all riddles defy solution: they are meant to be insoluble. Collections of riddles from many cultures make such an unexpected conclusion clear. The scholarly literature on this genre of popular culture is a shoreless sea. Especially instructive is the excellent recent book byProfessor Savely Senderovich Riddle of the Riddle.

Princess Turandot wanted to marry a smart man (and did).

Princess Turandot wanted to marry a smart man (and did).(By Marty Sohl/Metropolitan Opera in New York City, via Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

English has two homonyms: riddle “puzzle” and riddle “sieve” (the latter, I think, mainly northern English). Their origin has been known for centuries and can be found in any middle-sized dictionary, so that I won’t be able to say anything new about them. However, I have a tiny postscript, and it is for its sake I am telling this story. But first, here is a short and trivial note on the origin of riddle1 and riddle2.

The root of riddle “puzzle,” from rǣdels(e), is Old English rǣdan “to read.” Reading, it will be noted, is unlike swallowing or breathing: it is a skill, not an instinct. Literacy came to the Western “barbarians,” including the Anglo-Saxons, from Latin (with the conversion to Christianity), and they had to invent a word for the new occupation. Along that road, each tribe went its own way. Verbs meaning “think, guess; collect; count; carve, scratch,” and so forth were pressed into service. The closest cognates of English read are German raten “to advise,” Dutch raden “to advise; guess,” and Old Icelandic ráða (ð has the value of th in English this) “to rule, advise; explain.” Modern English still has the phrase to read a dream and another, semi-tautological, one, especially instructive in this context, “to read a riddle” (read “interpret”), though today the tautology is lost on us.

The most famous riddle in the world.

The most famous riddle in the world.(“Oedipus and the Sphinx of Thebes, Red Figure Kylix,” c. 470 BC, Vatican Museums, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

German Rätsel “riddle”is still an obvious cognate of raten, and the same holds for Dutch raadsel, related to raden. Such, however, is not the case of English riddle ~ read. Two sound changes severed the ties between the verb and the noun, and nothing connects those two words in the language intuition of today’s English speakers. Since the vowel in read is long, we might expect riddle to rhyme with beadle, but in the noun, that long root vowel was long ago shortened before the suffix. It might remain long, as happened in ladle (related to lade “to load”), bridle (related to braid), and many other similar words, but quantitative phonetic changes are rarely consistent.

Some words succumb to them, while the others manage to stay intact, and it is hard to account for their power of resistance. For example, English silly (with its short vowel) is related to German selig “happy” (with its long vowel preserved), while breeches is spelled with ee but rhymes with riches, rather than reaches. Likewise, sieve looks like a perfect rhyme for receive and deceive, but in fact, its poetic partners are live and give. To make matters even worse, the final consonant s in the old form of riddle was taken for the ending of the plural and dropped. The history of –s in English is a fitting plot for a short story. For example, alms, eaves, and riches were once singulars. Speakers misinterpreted –s in them but let it live, while in riddle, s was dropped, to reemerge only in the form of the plural.

Words shed sounds, as lizards drop their tails.

Words shed sounds, as lizards drop their tails.(By Martin LaBar, via Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Riddle “sieve” traces to Old English hriddel, related to the synonymous form hrīder and the verb hrīdrian “to sift” (sifts of course exist for sifting). The suffix –el in this riddle is the same as in riddle1, ladle, and the rest. Centuries ago, many English words began with hr-, hl-, hn-, and hw-. This initial h has been lost, except in the pronunciation of those who still distinguish between witch and which (in today’s erratic spelling, the old group hw– is reflected as wh-: consider which, when, who, and so forth). Thus, riddle1 and riddle2 became homonyms because of a series of phonetic changes, a most usual scenario. As a result, a modern proposal can be riddled with riddles to the despair of evaluators and the joy of punsters.

And now the promised desert should be served. There is another English word for “sieve,” namely, temes, going back to tamis “worsted cloth, originally used for straining sauces,” familiar from Indian cooking. Tamis “sieve, colander” is a living Modern French word. It has been known for centuries, but its origin remains disputed, and unambiguous facts do not support the suggestion that the Romance noun is an adaptation of the Germanic one. We will leave its etymology in limbo and only note that temes sounds like Thames. This fact gave rise to the hypothesis that in the popular saying to set the Thames on fire (usually about someone or some event that cannot set the Thames on fire) refers to that unfortunate sieve, rather than the river name.

A sieve without a riddle.

A sieve without a riddle.(Via Pxfuel, public domain)

Perhaps this wild guess would have been dead on arrival if it had not been supported, with a most dubious reference to material culture, by E. Cobham Brewer, the author of the once immensely popular Dictionary of Phrase and Fable. The book was on “everybody’s” desk. For years, people kept discussing whether in the process of sifting, some sieves or strainers may catch fire. Citations in my database go all the way from 1865 to 1921(!). Finally, sieves left the drama unscathed, and the Thames was allowed to remain inflammable. Analogs of phrases about rivers set on fire exist in several languages. The origin of the English idiom has not been found, and the OED has no citations of it before 1720. Such a late date makes one suspect that we are dealing with an adaptation of a similar idiom in a language other than English. Be that as it may, the entire argument looks like a parody of etymological research: some people who have more time on their hands than they need launch a ludicrous hypothesis, and the rest of the world keeps the ball rolling until the last thread disappears in the sand.

Featured image: “The Great Fire of London” by Josepha Jane Battlehooke, Museum of London, via Wikimedia Commons (public domain)

May 2, 2023

A listener’s guide to Rhythm Man [playlist]

A listener’s guide to Rhythm Man [playlist]

Rhythm Man: Chick Webb and the Beat that Changed America is the first full biography of the innovative 1930s Swing Era drummer/bandleader, known as the “Savoy King.” Rhythm Man traces Webb’s footsteps from his birthplace in East Baltimore to Harlem and on to national fame, with his popular big band and a young vocalist named Ella Fitzgerald, who went on to become the “First Lady of Song.”

Listen to the playlist and read on to trace Webb’s legacy on records and radio, from 1929 to 1939:

1. “Dog Bottom”Recorded in 1929, “Dog Bottom” is one of Chick Webb’s first records with his Harlem Stompers (the record label used “Jungle Band” as a pseudonym on record by several Black bands at the time). Webb and his 10-piece dance band are playing a Charleston-style stomp, driven by banjo, tuba, and Webb’s steady drumming, a vivid example of pre-swing jazz played by Harlem’s finest young musicians.

2. “Let’s Get Together”By 1933, Chick Webb’s Savoy Orchestra was playing a full-out, forward-moving swing rhythm. This arrangement by composer/arranger/alto player Edgar Sampson sets off a clever riff-based call-and response—Sampson’s specialty. This tune became the Webb Orchestra’s theme song soon after the record’s release in early 1934.

3. “Stompin’ at the Savoy”“Stompin’ at the Savoy” was also by Edgar Sampson, whose arranging style helped define the sound of Chick Webb’s band as it expanded into a powerhouse swing dance band. This tune became a staple of the Webb Orchestra’s repertoire at Harlem’s Savoy Ballroom, where the band reigned for the rest of the decade.

4. “Don’t Be That Way”This tune, also by Sampson, was another signature piece for Webb’s band, especially when performed by Ella Fitzgerald after lyrics were added later. The song was soon covered by Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw, and other popular white big band leaders, raising still-controversial issues of race and appropriation in the music business, themes explored in Rhythm Man.

5. “(If You Can’t Sing It) You’ll Have to Swing It”This 1936 recording—better known as “Mr. Paganini”—was one of Ella Fitzgerald’s first solid hits for the band. It’s got the lyrics of a 1930s novelty number—“Mr. Paganini, don’t you be a meanie…”—and shows off Ella’s talent as one of the first swing vocalists at the moment that swing rhythm and dance—the Lindy Hop—were sweeping the country.

6. “Go Harlem”“Go Harlem” displays Webb’s command of the band from his drummer’s throne. His playing delineates all the music’s phrases and dynamics of Sampson’s arrangement; meanwhile Webb is the perfect complement for the successions of soloists. He brings everyone together at the end, closing with cascading cowbells.

7. “Vote for Mr. Rhythm”Webb’s band swings out on this 1936 election year novelty, hitting all the right notes as Ella sings: “Now when I say vote for Mr. Rhythm, you all know I mean Chick Webb!” and that victory means, “Soon we’ll all be singing, ‘Of Thee I Swing.’”

8. “Harlem Congo”Recorded in fall 1937, this track displays the innovative virtuosity of Chick Webb throughout. He swings the band like crazy, and for the first time on records lets loose a 24-bar drum solo. He brings down the tempo and pace of the piece majestically, and concludes with a startling, yet also gorgeous, cymbal crash.

9. “Bei Mir Bist Du Schön”This song has an extraordinary history. It began as a Yiddish song written for a musical comedy, then became a major hit by the Andrews Sisters sung in English, though it was banned in Nazi Germany when its Jewish origin was discovered. Chick Webb’s Orchestra swings klezmer, while Ella’s voice soars with a bit of Yiddish lilt in her scatting.

10. “Liza (All the Clouds Will Roll Away)”This is Webb’s third recorded version of George Gershwin’s “Liza,” from a January 1939 radio transcription. Like “Harlem Congo,” here is the virtuosic Webb— an orchestra all by himself! Playing across his instruments —drums, cowbells, woodblocks, bells, and more— he pulls out all the stops, a blueprint for future drummers in big bands, rock bands, and beyond.

11. “A-Tisket, A-Tasket”Ella Fitzgerald started fooling around with rocking this nursery rhyme when the band was at a Boston nightclub in 1938. Van Alexander, Ella’s main arranger for Webb, crafted it into the band’s biggest hit ever. Ella and the band transformed this rhyme to gold with Ella’s buoyant swing, and a shuffle rhythm bordering on early rock’n’roll.

12. “One O’Clock Jump”Webb often paid tribute to other bandleaders, covering their best tunes. It was a challenge to compete with Count Basie’s band, which Webb and Basie did in an epic band battle in 1938. Here, Webb pushes the beat and so do his soloists—to the delight of generations of Lindy Hoppers.

13. “T’Aint What You Do but the Way That You Do it”Webb’s band swings out on this Jimmie Lunceford hit, while Ella wittily mangles the lyrics—“You’ll learn your ABCs, and then your DFGs.” A perfect snapshot of the era, Ella takes one of her lengthiest scat solos on record to date—upbeat and adorable.

14. “Let’s Get Together”This playlist closes with two broadcast recordings from the Southland Cafe in Boston, in May 1939. On this clip from the band’s theme song, Webb pounds out a forceful beat, encouraged by the wild crowd. Nobody on the dance floor could have suspected that Webb’s health was failing, and he would pass away a few weeks later.

15. “My Wild Irish Rose”Also recorded at Southland, Webb takes this sentimental popular song to stratospheric heights, playing it at what the Lindy Hoppers called his “killer tempo.” Webb’s stupendously musical pyrotechnics are aimed to whirl into everyone’s heart.

For more information on the life and legacy of Chick Webb, read Stephanie Stein Crease’s Rhythm Man: Chick Webb and the Beat that Changed America.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers