Oxford University Press's Blog, page 48

July 6, 2023

From Dr Google to ChatGPT: are the tides turning in how cancer patients access information?

From Dr Google to ChatGPT: are the tides turning in how cancer patients access information?

The discussions surrounding ChatGPT, a state-of-the-art natural language processing AI, are hard to miss. With its capabilities to draft articles, engage in written conversations, and provide complex coding solutions, ChatGPT holds great potential to revolutionize how people seek health information.

In November 2022, OpenAI introduced ChatGPT, first powered by GPT-3.5 architecture; it is now even more enhanced with its recent upgrade to GPT-4. Trained on vast amounts of text data, ChatGPT excels in translation, summarization, and question-answering tasks. The disruptive nature of GPT-4 is evident by Microsoft integrating it into the “new Bing” to compete with Google. Further, this technology is hypothesized to be able to power future AI tools that will serve as virtual assistants for telemedicine, clinical decision support, real-time translation, remote patient monitoring, and even patient triage interactions, drug information dissemination, and medical education.

Granting that ChatGPT is far from replacing a doctor’s consultation, our team investigated ChatGPT’s potential to revolutionize healthcare information-seeking. In our research, we compared the responses of ChatGPT to Google on questions frequently asked by cancer patients. These questions ranged from simple queries to detailed questions about symptoms, prognosis, and treatment side effects.

Round one: reducing alarmInterestingly, ChatGPT generates different answers when asked the same question multiple times. However, for straightforward questions, ChatGPT’s responses appear similar in quality to Google’s featured snippets. For example, when asked if coughing is a sign of lung cancer, both ChatGPT and Google’s snippet identified a persistent cough as a symptom of lung cancer. However, ChatGPT went further, explaining that various conditions can cause coughing and that a doctor’s consultation is necessary for an accurate diagnosis. Our clinical team valued these nuances in the information provided by ChatGPT for reducing unnecessary alarm.

Round two: directing you to a healthcare professionalIn our study, we also assessed the ability of ChatGPT to answer a complex question regarding pembrolizumab’s side effects. With GPT-3.5 architecture, ChatGPT’s responses were observed to vary considerably in quality and content. While all answers recommended consulting a healthcare professional, they needed more clarity on the urgency, potential severity, and occurrence of fever as a side effect of pembrolizumab. However, demonstrating the rapid advancement of this technology, the GPT-4 update now better emphasizes that it is not a doctor, that it provides general information only, and urges users to seek personalized advice from healthcare professionals about pembrolizumab adverse events.

Our team has also observed improved consistency in ChatGPT’s responses to other health-related questions, as it now consistently reminds users that it is not a doctor and that personalized advice should come from healthcare professionals. These are important updates that enhance the tool’s safety, potentially making it more reliable than having patients navigate the vast amount of links provided by Google, which can be tricky and potentially misleading.

Round three: consistencyDespite these updates, significant limitations remain for ChatGPT, indicating that ChatGPT is yet to be a reliable tool for health information. For example, the architecture is still prone to AI hallucinations (the phenomenon of AI producing responses that appear coherent but are, in fact, wrong or made up), providing questionable references, giving varying answers to a single query, and lacking real-time updates. At this stage, it is essential that healthcare professionals are aware of these limitations and ensure patients understand that AI tools like ChatGPT—similar to Google—need to be treated with considerable caution.

“All AI innovations impacting the patient-care interface must undergo rigorous implementation studies to ensure they deliver improved health outcomes without causing unwanted side effects for patients.”

Clinicians remain the best source for advice and should be consulted promptly for health queries, particularly about cancer or cancer treatment, where the consequences of delayed intervention can be serious. Furthermore, these limitations highlight the need for regulators to be actively involved in establishing minimum quality standards for AI interventions targeting healthcare.

Post-match commentaryThe use and availability of AI chatbots and assistants will continue to grow, and healthcare-targeted interventions will likely emerge. For these tools, it’s crucial to uphold the principles of evidence-based medicine. While AI advancements are exciting, even the best public health interventions can have unforeseen effects. All AI innovations impacting the patient-care interface must undergo rigorous implementation studies to ensure they deliver improved health outcomes without causing unwanted side effects for patients. Moreover, as evidence-based tools for healthcare emerge, it’s essential to address equity issues. Without careful planning, there is significant potential for medically focused AI tools to come with costly price tags, potentially exacerbating existing disparities in access to healthcare.

Acknowledgments: Ashley M. Hopkins would like to acknowledge Dr Ganessan Kichenadasse, Dr Jessica M. Logan, and Professor Michael J. Sorich for their contributions as co-authors of the original research paper at https://doi.org/10.1093/jncics/pkad010.

Interested in learning more about applications of AI regarding cancer information? Try this article by Skyler B Johnson, MD, et al: Using ChatGPT to evaluate cancer myths and misconceptions: artificial intelligence and cancer information | JNCI Cancer Spectrum | Oxford Academic (oup.com)

July 5, 2023

Dangerous neighbors: “sore” and “sorrow”

Dangerous neighbors: “sore” and “sorrow”

Last week, I discussed the history of the word day and half-heartedly promised to go on with an essay on night. But what little is known about the distant origin of night can be found in any good dictionary, and I gave up my idea. Yet I still wonder why night begins with the consonant n, the first sound of the most common negation (no and its likes) and the adjective naked. As a matter of fact, some etymologists did compare night and naked, but naked is also opaque and can therefore provide no help. For this reason, I have chosen another couple of twins: sorry and sorrow. Here again, I will have nothing original to say, but some details and considerations may be of interest to our readers.

Quite naturally, speakers connect words that sound alike. From a strictly scholarly point of view, sore and sorrow are unrelated, but for centuries, people thought differently, and folk etymology united the two long ago.

The etymology of “sore”We may begin with sore, which continues Old English sāre “grievous, painful.” English still has the archaic form sore “painfully, grievously,” as in the well-known phrase from the King James Bible: “…and they were sore afraid.” The modernized versions have: “…they were terrified” and “…they feared with a great fear.” This meaning of sore stops being a mystery as soon as we realize that its exact German counterpart is sehr “very.” Once upon a time, it also meant “painfully.” Likewise, the related Gothic word meant “pain.” (The Gothic Bible was recorded in the fourth century.) And we still say in English: “painfully obvious, thin, shy, etc.,” so that this usage makes sense.

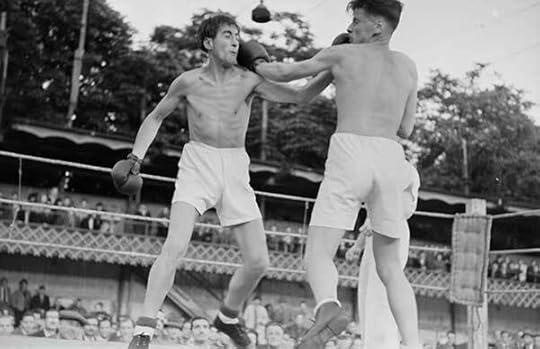

A good blow, or beaucoup.

A good blow, or beaucoup.Photo by Austrian National Library (public domain)

I may perhaps digress a little and say something about the words used to reinforce statements. Most often, they are adverbs and even prepositions, whose original meaning has been obliterated. Such is French très “very,” from Latin trans “beyond, through” (compare English thorough, a doublet of through; the idiom through and through, and the adverb thoroughly, as in thoroughly bored); Italian molto, that is, “much”; Latin maximē (which needs no gloss) and its synonym valdē from validē “strongly.” French merci beaucoup “thank you very much” refers to a good blow (at the moment, the English noun coup is “painfully” familiar to all!). In some languages, “tight” and “ready” are also on record as being the sources of “very, exceedingly.” English very, from French, means “truly” (compare verily).

Now back to sore. Old English sāre meant “painful.” If it had developed regularly, today, it would probably have rhymed with story, rather than quarry, though I am not sure whether all English speakers distinguish the vowels in Tory, story, hoary versus sorry and quarry. Anyway, today, sorry and sorrow are pronounced with the same vowel, because, as mentioned above, the two words are and were, for quite some time, thought to belong together. Sorry is related to sore (it is an adjective with the same suffix as in hoary and gory), not to sorrow, while sore is a common Germanic word for “pain” and “wound,” thus, not quite the same as Modern English sore.

“The devotion to something afar / From the sphere of our sorrow.” (Percy Bysshe Shelley)

“The devotion to something afar / From the sphere of our sorrow.” (Percy Bysshe Shelley)Photo by nega (public domain)

From an etymological standpoint, few inherited words are more obscure than the names of diseases, a taboo subject in all ancient societies. Such names were deliberately maimed, to hoodwink and ward off evil spirits, allegedly responsible for all the mental and bodily harm. Sometimes, we find inexplicable regularities. For instance, many words designating “pain” begin with the vowel a: English ache is one of them. Is it a coincidence to which we by mistake tend to ascribe sacral significance? Perhaps. But the fact remains that the history of such words as deaf, dumb, halt “lame,” and their likes is often impenetrable. To complicate our search, the oldest meaning of such words might be non-specific, something like “affliction; defect; confused; lost,” with later specialization. Thus, deaf is, most probably, related to Greek typhlós “blind.” Both referred to “darkness.”

The origin of sore, as could be expected, is obscure. It too has been sought in taboo, but the result of this search was far from convincing. Words having the root of sore in the old languages mean “wound.” It is probably natural to begin with a concrete meaning (“wound”) and move to such a general concept as “pain.” All the recorded cognates of sore have a long monophthong (ā), but judging by the form recorded in Gothic, the initial vowel was the diphthong ai. Why should a sound complex like sair– have designated a wound, pain, or something dangerous? Whether Latin saevus “fierce, dire” belongs here is immaterial (dictionaries cite it in connection with sore, but Walter W. Skeat doubted their relatedness), because the unquestionable cognates mean “grievous; suffering; painful,” rather than “fierce.” Thus, we would like to know why the ancient sound group sair– suggested the idea of being wounded and suffering from pain.

I keep returning to this question, because all etymology is about such queries. Where do we go from discovering the most ancient roots of our words? The answer is well-known but sad: nowhere, unless the root is sound-symbolic or sound-imitative (onomatopoeic). But sair– is neither, and we are left wondering why it was chosen to designate something dangerous and painful. The same question arises in a study of modern words. Why, for example, should flub mean “to botch, bungle”? Apparently, it was coined by someone in an unbuttoned moment and alighted itself with flabby, fluff, flop, and a host of other expressive fl-words, including the devilish Flibbertigibbet. But sair?

The etymology of “sorrow” I am sorry.

I am sorry.Photo by Caleb Woods (public domain)

In anger at our ignorance, we are moving to the noun sorrow. Its root in Germanic must have been surga– or sworga-. Modern German has Sorge, related to Old Norse sorg. This noun has related forms all over the Indo-European world. The prevailing sense of the recorded cognates is “sick(ness).” And there we stop again. As we have seen, English sore and sorrow are not related, that is, those two words cannot be derived from the same root. Yet we have two similar-sounding complexes: sair– (as in today’s sore) and surga ~ sworga- (as in today’s sorrow). From a strictly phonetic point of view, they are different, even incompatible. However, they refer to kindred concepts (pain, grief, anguish). It is probably not for nothing that English speakers associated and confused them.

Was there something in the mentality of our remote ancestors that made them associate the complex sr with pain and fear? Vowels are, after all, mere props. Br-and gr– are much better candidates for onomatopoeia and sound symbolism. Obviously, I won’t pull even the skinniest rabbit out of a hat in the last sentence of this blog post. (I wish I could!) Yet I suspect that the enigmatic sound group sr, for the reasons hidden from modern scholars, did have ominous connotations to the speakers of long ago. Not much of a rabbit. I know. Sorry!

Featured image: “Zan Zig performing with rabbit and roses”, Strobridge Litho Co., via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 2.0)

July 2, 2023

Helping verbs are curious, AND fascinating

Helping verbs are curious, AND fascinating

English has a big bagful of auxiliary verbs. You may have learned these as “helping verbs” in elementary and middle school, since they are sometimes described as verbs that “help” the main verb express its meaning. There are even schoolroom songs about them. They are a curious bunch.

The auxiliaries include the modal verbs (can and could, shall and should, will and would, may and might, and must). The verb that follows a modal is in its bare, uninflected form: can go, could go, must go, and so on. There are also a number of semi-modal auxiliary verbs (such as dare, need, ought to, had better, have to, and used to). Some are compound words spelled with a space and several have unusual grammatical properties as well, such as being resistant to contraction or inversion. And in parts of the English-speaking world, modals can double up, yielding expressions like might could, may can, might should, and more.

Aside from the modals, semi-modals, and double modals, the primary auxiliaries are forms of have, be, and do, which are inflected for tense (is versus was, has versus had, do versus did), number (is versus are, has versus have), and person(is versus am versus are, do versus does). These auxiliaries help to indicate verbal nuances like emphasis, the perfect and progressive aspects, and the passive voice. Here are some examples, adapted from Ernest Hemmingway’s The Old Man and the Sea:

Those who did catch sharks had taken them to the shark factory on the other side of the cove … (emphatic do and perfect aspect had)

The old man opened his eyes and for a moment he was coming back from a long way away. (progressive aspect)

His shirt was patched so many times that it was like the sail … (passive voice)

The primary auxiliaries come before the negative adverb not and allow contraction to it.

They didn’t catch sharks.

His shirt wasn’t patched.

He hadn’t taken the sharks.

And they play a role in questions by hopping to the left over the subject

Did they catch sharks?

Was his shirt patched?

Had he taken the sharks?

or by being copied at the end in a tag question.

They caught sharks, didn’t they?

His shirt was patched, wasn’t it?

He had taken the sharks, hadn’t he?

Main verbs like see and go and walk don’t do any of those tricks.

Things get even curiouser, however, because the helping verbs have and do have doppelgangers that actually are main verbs.

The old man did his chores.

His shirt had a tear in it.

How do we know these are main verbs and not helping verbs? Well, for one thing, they are the only verbs in the sentence. For another, they can occur with other helping verbs:

The old man had done his chores.

His shirt had had a tear in it all day.

And if you make the sentences questions or negate them, you have to add a form of auxiliary do.

Did the old man do his chores?

Did his shirt have a tear in it?

The helping verb be also has a doppelganger main verb, but the forms of main verb be behave pretty much just like the helping verb. More curious behavior, keeping us on our toes. The first sentence below has past tense main verb was followed by an adjective; the other two have the past tense helping verb was.

The shark was tenacious. (main verb was)

The shark was never caught. (auxiliary was)

The old man was trying his best. (auxiliary was)

But all three was forms hop to the left in questions.

Was the shark tenacious?

Was the shark ever caught?

Was the old man trying his best?

The curious behavior of helping verbs goes on and on, with different dialects doing different things. If you’ve read many British novels or watched British television you might have noticed forms of helping verb do popping up in elliptical sentences. Here’s an example from J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Two Towers: “Sam frowned. If he could have bored holes in Gollum with his eyes, he would have done.” (For a study of these forms, check out Ronald Butters’s 1983 article “Syntactic change in British English propredicates.”)

In African American English, the auxiliary done lends a completive meaning to events. You can see it in these dialogue examples from August Wilson’s Fences and from Walter Mosely’s Blond Faith: “Now I done give you everything I got to give you!” and “Didn’t she tell you that Pericles done passed on.” For more on this use of done, take a look at the chapters by Lisa J. Green and Walter Sistrunk and by Charles E. DeBose in the Oxford Handbook of African American Language.

We’ve just scratched the surface of auxiliaries. I hope you’ve become curious about these curious words.

Featured image by Alexander Grey via Unsplash (public domain)

June 29, 2023

“Lying” in computer-generated texts: hallucinations and omissions

“Lying” in computer-generated texts: hallucinations and omissions

There is huge excitement about ChatGPT and other large generative language models that produce fluent and human-like texts in English and other human languages. But these models have one big drawback, which is that their texts can be factually incorrect (hallucination) and also leave out key information (omission).

In our chapter for The Oxford Handbook of Lying, we look at hallucinations, omissions, and other aspects of “lying” in computer-generated texts. We conclude that these problems are probably inevitable.

Omissions are inevitable because a computer system cannot cram all possibly-relevant information into a text that is short enough to be actually read. In the context of summarising medical information for doctors, for example, the computer system has access to a huge amount of patient data, but it does not know (and arguably cannot know) what will be most relevant to doctors.

Hallucinations are inevitable because of flaws in computer systems, regardless of the type of system. Systems which are explicitly programmed will suffer from software bugs (like all software systems). Systems which are trained on data, such as ChatGPT and other systems in the Deep Learning tradition, “hallucinate” even more. This happens for a variety of reasons. Perhaps most obviously, these systems suffer from flawed data (e.g., any system which learns from the Internet will be exposed to a lot of false information about vaccines, conspiracy theories, etc.). And even if a data-oriented system could be trained solely on bona fide texts that contain no falsehoods, its reliance on probabilistic methods will mean that word combinations that are very common on the Internet may also be produced in situations where they result in false information.

Suppose, for example, on the Internet, the word “coughing” is often followed by “… and sneezing.” Then a patient may be described falsely, by a data-oriented system, as “coughing and sneezing” in situations where they cough without sneezing. Problems of this kind are an important focus for researchers working on generative language models. Where this research will lead us is still uncertain; the best one can say is that we can try to reduce the impact of these issues, but we have no idea how to completely eliminate them.

“Large generative language models’ texts can be factually incorrect (hallucination) and leave out key information (omission).”

The above focuses on unintentional-but-unavoidable problems. There are also cases where a computer system arguably should hallucinate or omit information. An obvious example is generating marketing material, where omitting negative information about a product is expected. A more subtle example, which we have seen in our own work, is when information is potentially harmful and it is in users’ best interests to hide or distort it. For example, if a computer system is summarising information about sick babies for friends and family members, it probably should not tell an elderly grandmother with a heart condition that the baby may die, since this could trigger a heart attack.

Now that the factual accuracy of computer-generated text draws so much attention from society as a whole, the research community is starting to realize more clearly than before that we only have a limited understanding of what it means to speak the truth. In particular, we do not know how to measure the extent of (un)truthfulness in a given text.

To see what we mean, suppose two different language models answer a user’s question in two different ways, by generating two different answer texts. To compare these systems’ performance, we would need a “score card” that allowed us to objectively score the two texts as regards their factual correctness, using a variety of rubrics. Such a score card would allow us to record how often each type of error occurs in a given text, and aggregate the result into an overall truthfulness score for that text. Of particular importance would be the weighing of errors: large errors (e.g., a temperature reading that is very far from the actual temperature) should weigh more heavily than small ones, key facts should weigh more heavily than side issues, and errors that are genuinely misleading should weigh more heavily than typos that readers can correct by themselves. Essentially, the score card would work like a fair school teacher who marks pupils’ papers.

We have developed protocols for human evaluators to find factual errors in generated texts, as have other researchers, but we cannot yet create a score card as described above because we cannot assess the impact of individual errors.

What is needed, we believe, is a new strand of linguistically informed research, to tease out all the different parameters of “lying” in a manner that can inform the above-mentioned score cards, and that may one day be implemented into a reliable fact-checking protocol or algorithm. Until that time, those of us who are trying to assess the truthfulness of ChatGPT will be groping in the dark.

Featured image by Google DeepMind Via Unsplash (public domain)

June 28, 2023

Plain as day?

Etymologists interacting with the public on a day-to-day basis usually receive questions about words like copacetic and shenanigans, but so many nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, and even prepositions and conjunctions not crying for attention are not less, perhaps even more, interesting. Over the years, I have written about summer, winter, ice, sheep, dog, live, leave, good, bad, red, and even such inconspicuous words as but and yet, to mention just a few. We use them like old trusty tools and never stop to ask where they came from. Somebody somewhere coined them, which probably means that once upon a time they were as transparent to speakers as giggle and hiccup. But today their origin is either debatable or unknown. Isn’t a dog called a dog because it looks like a dog, runs like a dog, and barks like a dog? This is what the naïve speaker thinks, though nothing in the group d-o-g suggests a muzzle, swiftness, or any kind of explosive sound. How did day and night get their names? Aren’t the words in some way associated with light and darkness? Dictionaries know a lot about the oldest history of both but do not always provide a clue to the “motivation” that might explain their origin.

Let us look at day. Its past is not totally hidden (no reference to or pun on clear obscure!). Day has exact cognates everywhere in Old Germanic, including of course Old English, as well as in Sanskrit, Celtic, Slavic, and elsewhere. In Old Icelandic, the proper name Dagr has been recorded. Similar names existed in Gothic and Old High German. Does this fact testify to the word’s significance in some religious ritual? We’ll never know. What conclusion will an etymologist two thousand years from now draw about our names June, Melody, and Makepeace? Day, it should be remembered, does not always mean “a period of twenty-four hours” (as in a few days ago) or half of this period (as in day and night or daytime): it sometimes refers to “a certain period or date” as in Doomsday, the day of reckoning, I’ll remember it until my dying day, and the like. Even if you were born at night, you probably celebrate your birthday. It follows that we are not quite sure where to begin our exploration, though day as “the period of light” looks more promising: after all, law-abiding citizens tend to make their arrangements for the time when there is enough light around, while at night most of us sleep.

DAWN, the beloved sister of DAY.

DAWN, the beloved sister of DAY.(Via Pexels, public domain)

Speakers of Modern English no longer realize that dawn has the same root as day. The verb to dawn means “to begin to grow light,” and the same reference is obvious in the phrase it dawned on me. I’ll skip the phonetic part of the story (why dawn? In German, unlike what we observe in English, the connection between the noun Tag and the verb tagen is immediately obvious). Will then a search for the etymology of day take us to the idea of “light,” as suggested above? Perhaps. But first, let us remember Latin diēs “day.” Its root occurs in the English words diurnal, dial “an instrument to tell the time of day by the shadow cast by the sun,” and diary, all three of course borrowed from Romance. Though diēs and day sound somewhat alike, they are not related (a fact often mentioned in dictionaries, to warn readers against what looks like an obvious conclusion), and as though to prove the absence of ties between them, language provides us with a word like Gothic sin-tiens “daily,” in which sin– means “one” and –tien– is a cognate of the Latin word. The correspondence d (Latin) ~ t (Gothic or any other Germanic language) is regular, by the so-called First Consonant Shift: compare Latin duo versus English two.

This is what a dial looks like.

This is what a dial looks like.(“Ottoman Sundial at the Debbane Palace museum” by Elias Ziade, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

This –tien- has unquestionable correspondences all over the Indo-European world: for example, Sanskrit had dínam “day.” In Latin, we find the word nun-dinum “market held every ninth day.” Also, Russian den’ “day” (with cognates elsewhere in Slavic) and many other references elsewhere to burning, ashes, and warmth belongs here too. On the strength of, among others, several Greek words meaning “appear” and “visible,” the root of all such words has been understood as “shining.” Since the Sanskrit dèvas (obviously related) means “god,” this idea looks realistic. The Indo-Europeans habitually referred to “god” as “shining” or “sky” (such was Latin Jū-piter “sky father,” known to the ancient Scandinavians as Týr, no longer a sky god; but the name reveals his distant past). Yet it is still odd that both the words related to day and those related to diēs, though unconnected, sound somewhat alike and not only mean “day” but also begin with d. Did d suggest burning, heat, or glowing or refer to things dry and arid? Such ancient sound-symbolic associations are beyond reconstruction. They are often hard to pinpoint even in our modern languages.

Another puzzling lookalike is Sanskrit áhar “day.” It almost rhymes with Proto-Germanic dagaz but lacks d-, to which, above, I ventured to ascribe magical properties. An incredible coincidence? The Sanskrit noun has no correspondences in Germanic, Romance, Celtic, and elsewhere. (At least, none has been discovered.) Did áhar once have d- and lose it? The fertile imagination of historical linguists reconstructed several processes that could be responsible for the loss. Initial d- does sometimes disappear for no known reasons. For instance, t in tear (from the eye), which, as expected, corresponds to d outside Germanic, is sometimes absent altogether: this is true of Sanskrit and Baltic, among others. We have enough trouble with s–mobile (it tends to turn up wherever it wants). Did d–mobile also exist? Most unlikely.

Jupiter and his degraded Scandinavian counterpart Týr.

Jupiter and his degraded Scandinavian counterpart Týr.(L: Louvre Museum. R: Icelandic National Library. Both via Wikimedia Commons, public domain.)

My point has been to show how intriguing some of our common words sometimes are. Copacetic is late (it was first recorded in the twentieth century), while day is older than most of the hills around us. But the problem of origin remains the same: people coin words and etymologists wander in a labyrinth of look-alikes, roots, fleeing initial, and final consonants, and emerge with the all-too familiar verdict: “Origin unknown (uncertain, disputed).” Yet day probably did refer to heat or a bright light. This conclusion sounds reasonable, assuming (and this a reliable assumption) that the word’s initial sense was “the time of light,” rather than “a certain period, date.” Plain as day? Almost.

Featured image by Ivana Cajina via Unsplash (public domain)

June 27, 2023

The great gun conundrum [podcast]

The great gun conundrum [podcast]

With estimates of nearly 400 million privately-owned firearms in the United States and more than 40,000 deaths due to gun violence each year, guns and gun ownership have become polarizing issues. Forty-eight percent of Americans view gun violence as a major problem, with more than half of US citizens favouring stricter gun laws. The prevailing arguments, both for and against greater gun ownership restrictions, incorporate a range of issues, from party lines and political agendas to the influence of media coverage and the role of police in combatting violence—but what does recent scholarship reveal, and how might this scholarship inform policy for the better?

On today’s episode of The Oxford Comment, we explore the history of gun ownership in the United States and practical solutions for resolving contemporary gun violence. First, we welcomed Robert J Spitzer, the author of The Gun Dilemma: How History is Against Expanded Gun Rights, to share new historical research on America’s gun law history as it informs modern gun policy disputes. We then interviewed Philip J Cook, the author of Policing Gun Violence: Strategic Reforms for Controlling Our Most Pressing Crime Problem, who spoke with us about utilising the police as a strategic resource for reducing gun violence.

Check out Episode 84 of The Oxford Comment and subscribe to The Oxford Comment podcast through your favourite podcast app to listen to the latest insights from our expert authors.

Oxford Academic (OUP) · The Great Gun Conundrum – Episode 84 – The Oxford CommentRecommended readingRead the first chapter from Robert Spitzer’s book, The Gun Dilemma: How History is Against Expanded Gun Rights, which explores the policy dilemma of a public strongly supportive of stronger gun laws, and overwhelmingly supporting of existing laws, while gun rights advocates press to repeal existing gun laws by expanding the definition of gun rights.

Read the second chapter of Philip J. Cook and Anthony Braga’s book Policing Gun Violence, which explores the social burden of gun violence. The authors explore the widespread fear and trauma that stem from the threat of gun violence and the required vigilance to avoid victimization, addressing the statistics of the communities that are most affected.

The fourth chapter of The Silent Epidemic of Gun Injuries by Melvin Delgado approaches gun violence interventions as establishing a foundation using the latest thinking and data. A social perspective on gun injuries allows for casting a wide net in capturing this phenomenon, helping readers develop a wide lens for gun injury. Grasping the social meaning of guns is essential in coordinating public health campaigns on the outcomes they cause.

Read the introduction to Mark R. Joslyn’s The Gun Gap: The Influence of Gun Ownership on Political Behavior and Attitudes, wherein the gun gap is defined to refer to differences in political behavior and attitudes between gun owners and nonowners. In addition, the introduction establishes why the gun gap is important for understanding modern mass politics.

This chapter from Pained: Uncomfortable Conversations about the Public’s Health by Michael D. Stein and Sandro Galea explores how states with stricter firearm legislation have fewer fatal police shootings—defined as the rate of people killed by law enforcement agencies. Also assessed is the relationship between different types of legislation and rates of fatal police shootings, showing laws that strengthen background checks, promote child and consumer safety, and reduce gun trafficking are linked to lower rates of fatal police shootings.

Read the following Open Access articles from our journals:Social media response to mass shootings in the United States provides an important window into the nature of public mourning and policy debates in the wake of these tragedies: “Whose Lives Matter? Mass Shootings and Social Media Discourses of Sympathy and Policy, 2012–2014” by Yini Zhang et al, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication (July 2019)Social movements pushed to reconceptualize intimate partner violence (IPV) as a social problem deserving of intervention rather than a private family matter, but political ideology and affiliation shape support for disarming the abuser or arming the victim: “Polarized Support for Intimate Partner Violence Gun-Related Interventions” by Anne Groggel, Social Problems (January 2023)Within the business of organized crime, guns are mostly used as a threat or to maim or kill but they also serve the more basic masculine requirement of protection, giving them a symbolic meaning as well as serving as a resource for achieving power: “Masculinities on the Continuum of Structural Violence: The Case of Mexico’s Homicide Epidemic” by Jennie B Gamblin and Sarah J Hawkes, Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society (Spring 2018)Taking a long view of police shootings from 1970 to 2020 lessens the stochastic effect of shootings over shorter time periods and reveals that the frequency of police shootings has increased in both jurisdictions over this period, despite police not being routinely armed with firearms: “Police Shootings in New Zealand and England and Wales: A Cross-National Comparison” by Ross Hendy and Darren Walton, Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice (April 2022)Featured Image: bermixstudio, CC0 via Unsplash

June 26, 2023

Is a 15-week limit on abortion an acceptable compromise?

Is a 15-week limit on abortion an acceptable compromise?

A recent opinion piece by George F. Will, “Ambivalent about abortion, the American middle begins to find its voice” in the Washington Post made the startling claim that the overturning of Roe v. Wade (Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, 2022) has resulted in “a partial healing of the nation’s civic culture.” One might think exactly the reverse. The Dobbs decision energized voters, especially women and young people, resulting in numerous Republican electoral defeats across the country. However, Will argues that the return of abortion policy to the states gives voters the opportunity of choosing moderate restrictions on abortion. Since most Americans support early abortion while opposing late-gestation abortion, Will thinks that a 15-week ban on abortion would be an acceptable compromise.

Why 15 weeks? Two reasons can be given. Almost all abortions in the US—93%—occur within the first 15 weeks of pregnancy. For this reason, making abortion illegal after 15 weeks would not, it would seem, impose serious burdens on most people seeking abortions.

Another reason is that several European countries limit abortion on request to the first trimester, leading some US lawmakers to suggest that a 15-week ban would bring our abortion law in line with theirs. This is disingenuous, to say the least. While elective abortion is limited in some European countries, it is not banned afterwards, but is allowed on other grounds, including economic or social reasons, or a threat to the woman’s physical or mental health. Moreover, in most European countries, patients do not have to pay for abortion; it is covered under universal health coverage. The fact is that the trend in Europe has not been to limit abortion, but to expand access to it. Countries in Europe “… have removed bans, increased abortion’s legality and taken steps to ensure laws and policies on abortion are guided by public health evidence and clinical best practices.”

Were states to guarantee access to abortion prior to 15 weeks, a 15-week ban might be acceptable. However, even before Dobbs, many women in the US lacked access to abortion, due to a dearth of providers, especially in rural areas. They often had to travel many miles to find an abortion clinic, which meant that they had to arrange childcare if they have other children or take time off work. Delay is also caused by the need to raise money for an abortion, which is not paid for by Medicaid in most states, except in cases of rape, incest, or a life-threatening condition. To be sure, even if there were none of these roadblocks, some women would still not be able to have early abortions because they do not know that they are pregnant, due to youth, being menopausal, chronic obesity, or a lack of pregnancy symptoms. Any time limits will pose hardships for some people. But if access to early abortions were guaranteed, a compromise on a 15-week limit might be worth it.

I suspect that time-limit advocates are not particularly interested in making sure that women who have abortions get them early in pregnancy. They want to place roadblocks in the way of getting abortions, full stop. That these roadblocks increase the numbers of late abortions is of little concern to them, however much they wring their hands over late abortions. Abortion can be reduced by reducing the number of unwanted pregnancies, something that has been shown to be achieved by access to contraceptives and science-based sex education in the schools. Remember when pro-lifers emphasized those methods? Me neither.

“Some US lawmakers suggest that a 15-week ban would bring our abortion law in line with European countries. This is disingenuous, to say the least.”

My second concern is with abortions sought after 15 weeks. The reason for a late abortion may be that the woman has a medical condition that has not developed, or has not been detected, until later in pregnancy. In such cases, the pregnancy is almost always a wanted pregnancy, and the decision to terminate imposes a tragic choice.

It may be responded that all states allow abortions to be performed when this is necessary to save the pregnant woman’s life, and many allow for abortions to protect her from a serious health risk. The problem is that these exceptions conflict with standard medical care, especially in the case of miscarriage. Once the woman has begun to miscarry, the failure to remove the fetus is likely to cause her sepsis, which can be life-threatening. However, in states with restrictive abortion laws, doctors cannot perform an immediate abortion, which is the standard of care in such situations. They have to wait until her death is imminent and, in some states, they cannot remove the fetus until its heart stops.

Ireland’s restrictive abortion law was repealed after a woman who was denied an abortion during a miscarriage died from septicemia. To the best of my knowledge, no woman in the US has died as a result of restrictive abortion laws, but some have come close. An OB-GYN in San Antonio had to wait until the fetal heartbeat stopped to treat a miscarrying patient who developed a dangerous womb infection. The delay caused complications which required her to have surgery, lose multiple liters of blood, and be put on a breathing machine. Texas law essentially requires doctors to commit malpractice.

Conservatives often portray those in the pro-choice camp as advocating abortion until the day of delivery, for trivial reasons. This is deeply unfair. If they want us to compromise on time limits, they should be willing to guarantee access to abortion before 15 weeks. They should be willing to compromise on pregnancy prevention through contraception and sex education. And they should agree to drop all restrictions on late-term abortions that make legislators, rather than doctors, in charge of deciding what is appropriate medical care for their patients.

Featured image: Gayatri Malhotra via Unsplash (public domain)

June 22, 2023

Real patterns and the structure of language

Real patterns and the structure of language

There’s been a lot of hype recently about the emergence of technologies like ChatGPT and the effects they will have on science and society. Linguists have been especially curious about what highly successful large language models (LLMs) mean for their business. Are these models unearthing the hidden structure of language itself or just marking associations for predictive purposes?

In order to answer these sorts of questions we need to delve into the philosophy of what language is. For instance, if Language (with a big “L”) is an emergent human phenomenon arising from our communicative endeavours, i.e. a social entity, then AI is still some ways off approaching it in a meaningful way. If Chomsky, and those who follow his work, are correct that language is a modular mental system innately given to human infants and activated by miniscule amounts of external stimulus, then AI is again unlikely to be linguistic, since most of our most impressive LLMs are sucking up so many resources (both in terms of data and energy) that they are far from this childish learning target. On the third hand, if languages are just very large (possibly infinite) collections of sentences produced by applying discrete rules, then AI could be super-linguistic.

In my new book, I attempt to find a middle ground or intersection between these views. I start with an ontological picture (meaning a picture of what there is “out there”) advocated in the early nineties by the prominent philosopher and cognitive scientist, Daniel Dennett. He draws from information theory to distinguish between noise and patterns. In the noise, nothing is predictable, he says. But more often than not, we can and do find regularities in large data structures. These regularities provide us with the first steps towards pattern recognition. Another way to put this is that if you want to send a message and you need the entire series (string or bitmap) of information to do so, then it’s random. But if there’s some way to compress the information, it’s a pattern! What makes a pattern real, is whether or not it needs an observer for its existence. Dennett uses this view to make a case for “mild realism” about the mind and the position (which he calls the “intentional stance”) we use to identify minds in other humans, non-humans, and even artifacts. Basically, it’s like a theory we use to predict behaviour based on the success of our “minded” vocabulary comprising beliefs, desires, thoughts, etc. For Dennett, prediction matters theoretically!

If it’s not super clear yet, consider a barcode. At first blush, the black lines of varying length set to a background of white might seem random. But the lines (and spaces) can be set at regular intervals to reveal an underlying pattern that can be used to encode information (about the labelled entity/product). Barcodes are unique patterns, i.e. representations of the data from which more information can be drawn (by the way Nature produces these kinds of patterns too in fractal formation).

“The methodological chasm between theoretical and computational linguistics can be surmounted.”

I adapt this idea in two ways in light of recent advances in computational linguistics and AI. The first reinterprets grammars, specifically discrete grammars of theoretical linguistics, as compression algorithms. So, in essence, a language is like a real pattern. Our grammars are collections of rules that compress these patterns. In English, noticing that a sentence is made up of a noun phrase and verb phrase is such a compression. More complex rules capture more complex patterns. Secondly, discrete rules are just a subset of continuous processes. In other words, at one level information theory looks very statistical while generative grammar looks very categorical. But the latter is a special case of the former. I show in the book how some of the foundational theorems of information theory can be translated to discrete grammar representations. So there’s no need to banish the kinds of (stochastic) processes often used and manipulated in computational linguistics, as many theoretical linguists have been wont to do in the past.

This just means that the methodological chasm between theoretical and computational linguistics, which has often served to close the lines of communication between the fields, can be surmounted. Ontologically speaking, languages are not collections of sentences, minimal mental structures, or social entities by themselves. They are informational states taken from complex interactions of all of the above and more (like the environment). On this view, linguistics quickly emerges as a complexity science in which the tools of linguistic grammars, LLMs, and sociolinguistic observations all find a homogeneous home. Recent work on complex systems, especially in biological systems theory, has breathed new life into this interdisciplinary field of inquiry. I argue that the study of language, including the inner workings of both the human mind and ChatGPT, belong within this growing framework.

For decades, computational and theoretical linguists have been talking different languages. The shocking syntactic successes of modern LLMs and ChatGPT have forced them into the same room. Realising that languages are real patterns emerging from biological systems gets someone to break the awkward silence…

Featured image by Google DeepMind Via Unsplash (public domain)

June 21, 2023

Confronting bud and buddy

In the previous installment (14 June 2023), I mentioned several attempts to explain the origin of bud(dy). See also the comment at the bottom of that post. It may perhaps be useful to remember that monosyllabic words beginning with b, d, g ~ p, t, k and ending in one of those consonants (bed, big, pig, kick, gig, dog, gag, keg, dab, bug, and a host of others) are notoriously obscure from the etymological point of view. Sound imitative? Sound-symbolic? Baby words? Borrowed? Some of them once had an ending (e, i, a), which is of no consequence as regards their origin. Incidentally, bud (on a plant) also poses problems. Known from texts since the Middle English period, it has a Dutch lookalike with t at the end and resembles French bouton, which may be of Germanic origin, but this derivation is far from certain. In one widely-used but rather unreliable dictionary, buddy is said to be “etymologically identical with the adjective buddy ‘full of buds’.” Thus, our correspondent, who had a similar idea, even though she cannot be said to be in good company, is at least not alone. Another complicating factor deserves mention. Such nouns and verbs may be coined, forgotten, and coined again in the same form. After all, it is not too hard to come up with words like bob, gab, pad, and so forth.

Buddy poses familiar problems. It may or may not be a native word. Everybody is agreed that we are dealing with an Americanism. It appeared in texts around the year 1800, which excludes the idea of its derivation from bud “part of a plant.” Strange things sometimes happen. Guy, one the most common American words, goes back to a proper name and the 1605 Gunpowder Plot. The plot happened in England, but guy ousted or limited the use of pal, fellow, and their likes in American English. Last week, I mentioned Skeat’s derivation of buddy from booty-fellow and expressed my doubts on this score. Despite my admiration of everything Walter W. Skeat did, I keep thinking that in this case he was wrong.

Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm: two brothers, two buddies.

Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm: two brothers, two buddies.(Via Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

What follows depends largely on Jeremy Bergerson’s article in the Dutch periodical Leuvense Bijdragen (91, 2002, 63-71). Dutch has the dialectal word boetje “brother.” It has been recorded in numerous variants, and, according to a reasonable suggestion, it is an affectionate form of the baby word boe “brother.” In recent English scholarship, the idea that buddy goes back to brother has gained the upper hand. The direction seems to be correct, but the way may have been less straight than etymologists would like it. The problem is the loss of r after b. In languages in which r is a trill (or a roll: both terms mean the same), for instance, Spanish, Italian, and Russian (to cite a few examples), r is usually the hardest sound to master. Children tend to substitute l for it. But English r is NOT a trill, and the well-known substitution for it is w. Many of us have heard children say: “I am hungwy.” This is also a much-ridiculed pseudo-aristocratic affectation. As a general rule, an English-speaking baby would probably not say buddy for brother.

We may try to ask for help abroad. Dutch bout, beut, boetje, and budde, among many other similar forms, seem to go back to the baby word boe (pronounced with a vowel like English oo in boo). The story is partly reminiscent of the history of English boy. Boy, too, may be a derivative of a baby word for “little brother,” and the Old English name Boia perhaps contains the “root” in its pristine form. Dutch Boio, Boiga, Boga, and even Scandinavian Bo may once have meant “little brother.” (More details on this score can be found in my and J. Lawrence Mitchell’s An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction, pp. 15-16). If this reconstruction is correct, the many words cited above do go back to “brother,” but not to the word brother. The baby etymon contained no r. This suggestion runs counter to what we find in some of our most respectable sources.

They are happy, rather than hungwy.

They are happy, rather than hungwy.(Via Wallpaper Flare, public domain)

Unexpected light on the origin of buddy comes from the English word Boots. The word is known from such compounds as slyboots and lazy–boots, but most will probably remember Boots “a name for the servant in hotels who cleans the boots.” The OED cites numerous examples. Apparently, Boots emerged with the meaning “servant; a person at the lowest level of the hierarchy” rather than “shoeshine boy.” This is evidenced by such senses as “the youngest officer in a regiment” and others. The hotel Boots did clean boots and put them outside the gentleman’s door, but this is not why he received his name. George Webbe Dasent used the word Boots for rendering Norwegian Askepott ~ Askeladden (this is what the despised third son in fairytales, “male Cinderella,” is called). If Dasent had associated Askepott only or mainly with the shoe shiner, he would hardly have used the word in such a context. An ingenious correspondent to Notes and Queries once suggested that Puss in Boots might be a misnomer, because allegedly, Puss and Boots, that is, Puss as Servant was meant. But the English title is a translation from French, where Chat botté is unambiguous.

Askeladden in full glory.

Askeladden in full glory.(Via Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

Bergerson suggested that Boots is a borrowing of Dutch boet, a childish word for “brother.” We find Dutch boet “a recent recruit in the Indian Army” and a few other words that fit our story well. If boet (pronounced approximately like English boot) was indeed borrowed into English with the meaning “a person of inferior rank,” the rest is plain sailing. The ending s is added freely to English words. I, for example, have dealt with two guineapigs: Cuddles and Sniffers. In Dickens’s Dombey and Son, the servant who wheeled Mrs Skewton around had the name Withers. Dobbin of ours, a most important character in Thackeray’s Vanity Fair, was called Figs, because his father sold all kinds of groceries. And don’t we occasionally live in digs and have things for keeps?

Dutch words in English are numerous (very numerous indeed). If Boots is one of them, perhaps so is buddy from boetje. The voicing of t between vowels is no problem. Buddy is an American coinage, and in American English, intervocalic t is voiced, so that seated and seeded, Plato and playdough, sweetish and Swedish, futile and feudal (to mention just a few examples), are homophones pairwise. With time, the vowel in boetje acquired, as expected, the value of u in but, and butty ~ buddy was born. Speakers quite correctly interpreted the last sound as a diminutive suffix and produced bud from buddy by back formation. The word has just the expressive value one needs: compare studs “a great virile guy,” as in Studs Lonigan byJames T. Farrell.

Have we solved the riddle? No, the etymology of buddy and Boots will probably remain “debatable” (unless it suddenly gains universal recognition—a rare case in etymological studies), but perhaps we have made a step in the right direction.

Featured image via pxfuel (public domain)

June 20, 2023

Rethinking the future of work: an interview with Phil McCash

Rethinking the future of work: an interview with Phil McCash

Meet co-editor of The Oxford Handbook of Career Development Phil McCash. Phil is a qualified career development practitioner and currently works as an Associate Professor at the University of Warwick’s Centre for Lifelong Learning where he is Director of Graduate Studies and teaches on postgraduate courses in career development and career coaching. His work addresses the context, theory, and practice of career development in the contemporary world.

Discover his thoughts on career development and the future of work.

1. What initiatives can organizations put in place to enhance their employees’ careers?One of the best ways organisations can enhance their employees’ careers is through access to career coaching. Career coaching can be accessed through external providers or delivered internally by suitably trained members of staff.

The key to this training lies in helping the career coach learn how to forge an appropriate relationship between the career coach and the employee. This tends to be seen nowadays as a form of learning alliance. The alliance needs to be initially agreed in relation to the initial, middle, and end phases of career coaching interactions.

Once established, this coaching relationship can be used to support the career learning of employees in relation to a wide range of topics including career influences, workplace relationships, and career management styles. As part of their training and development, career coaches also need to engage in reflexivity and assessment.

Read Phil McCash’s article “Cultural Learning Theory and Career Development” in The Oxford Handbook of Career Development (2021) for more on cultural learning theory and coaching.

2. What are the most common obstacles in career development?One of the biggest problems identified in the career development field is the decline in decent work. This rise in precarious work is resulting in work instability and poverty for growing numbers of workers throughout the world. The reduced availability and quality of jobs globally has negative consequences for the individual, community, and society. Ellen Gutowski and others argue for the necessity of decent work for all.

“Career development theory and practice have the potential to foster a sense of belonging and well-being by facilitating the construction of meaningful life-careers.”

A further and related issue is social justice. Career development theory and practice have the potential to foster a sense of belonging and well-being by facilitating the construction of meaningful life-careers. Social justice issues are integral because they are concerned with fairness and equity, (in)equality, cultural diversity, psychosocial well-being, and societal values. Barrie Irving argues that we need a deeper understanding of social justice and the multiple and complex influences on how “career” is interpreted and “opportunities” are presented. Such an understanding should provide critical insight into the effects of wider sociocultural and political concerns affecting what is deemed possible in the shaping and enactment of career.

3. Can career theories be applied globally?Career theories from the Global North have sometimes been imported and applied uncritically in the Global South countries. These theories were developed in different socioeconomic and cultural contexts than those of the Global South, which can generally be characterized by vulnerability and instability. Marcelo Ribeiro argues that these theories and practices must be contextualized if they are to be of assistance to the users of career development services. Through intercultural dialogue, we need to contextualize theories to assist people with their career issues and foster social justice. We also need to understand career theories and practices produced in the Global South (Latin America, Africa, and developing countries of Asia) and their potential as an alternative to expand the mainstream career development theories from the North. Such theories can be understood as a Southern contribution to the social justice agenda.

4. How does increased flexibility impact employees and organizations?Increased flexibility and its impact have been debated in the field of organisational studies for many years. Organizational career development theory highlights three different perspectives on career.

First, and most commonly, organizations are seen as the context that constrains and enables individual careers. Second, careers may be valued as enhancing or limiting organizational performance and subject to talent management practices. Third, careers can be conceptualized as an ongoing process of interaction between individuals, organizations, and the broader social context.

The move from a focus on organizational careers to highly flexible, self-driven, boundaryless careers in the 1990s overemphasized individual choice and individual responsibility. These ideas became the accepted rule, leading to a divided workforce, with real choice available only to some categories of workers. The psychological contract between individual and organization was largely undermined, and the role of the organization and the importance of contextual and structural factors were relatively neglected.

To move forward, Kate Mackenzie Davey argues that this opposition between organization structure and individual agency is best avoided. The future of organizational career development theory requires an understanding of both the individual and social context, and their interaction over time.

5. What do you think the world of work will look like in 10 years?Debates about the future shape of the working world feature regularly in the field of organisational and managerial career studies. Hugh Gunz and Wolfgang Mayrhofer propose a Social Chronology Framework in which the study of careers should be seen to involve the simultaneous application of three perspectives: being, space, and time. Building on this, they emphasise the importance of a coevolutionary perspective. Within a bounded social and geographic space, career development happens based on configurations of individual and collective career actors who provide context for each other and coevolve together. They argue that this approach can suggest new ways of seeing established career development arrangements.

In addition, the world of work is inevitably shaped by public policy frameworks. Christian Percy and Vanessa Dodd set out a conceptual model of the economic outcomes of career development work. It is centred on the financial metrics that are most important to stakeholders at three different tiers of the economy. These tiers include individuals, organizations/employers, and the state. Empirical examples from the literature are provided to show that financial impacts can be identified at each tier. The limitations of the model and the evidence base are discussed. In addition, a critical examination of a narrow focus on economic outcomes in public policy is presented in order to convey the limitations of an economistic rationale for career development.

Taking this further, Pete Robertson explores and questions the aims of public policy for career development. In the early years of the twenty-first century, an international consensus emerged in the literature describing the intentions of governments when they seek to intervene in the careers of their citizens. He makes a case for a broader conception of the socially desirable outcomes from career interventions. Drawing on the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, he proposes a systematic framework of six types of policy goal for career development services:

labour market goalseducational goalssocial equity goals,health and well-being goals,environmental goals, andpeace and justice goals.The latter three categories represent new or relatively neglected areas of focus. The proposal highlights cross-cutting themes of social justice, sustainability, and societal change within public policy for career development in the coming years.

Visit the Rethink Work hub for more organizational psychology insights

Featured image: Canva

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers