Oxford University Press's Blog, page 55

March 21, 2023

Twenty years on: Luis Moreno Ocampo on the International Criminal Court

Twenty years on: Luis Moreno Ocampo on the International Criminal Court

In 2003, 78 nations gave me the authority, as the Chief Prosecutor, to trigger the International Criminal Court (ICC) intervention in their territory.

I had to decide for the first time when and where to trigger the ICC. Should the Court open investigations in the Democratic Republic of Congo or Colombia? Did Prime Minister Blair’s decision to intervene in Iraq allow the Court to open an investigation against President Bush?

We had no benchmark. Political leaders in post-Nazi Germany, Yugoslavia, and Rwanda decided the international criminal intervention in those nations. The Rome Statute created a different model. My mission was to establish an Office of the Prosecutor to implement a judicial mandate in what was a political field.

Each of our decisions to launch the Court intervention was in strict compliance with the law and confirmed by the judges. However, they triggered heated debates. No single framework exists to harmonize justice demands, political decisions, military operations, humanitarian assistance, peace negotiations, and court interventions. I perceived the lack of a common criterion to manage transnational violence.

War and Justice in the 21st Century: an overviewSince the end of my tenure in 2012, I have been working on a book to transform my unique experience into valuable data. I was a decision-maker and a privileged witness. I don’t have a thesis to prove. The book describes our office standards, the facts, and the role of other actors in 17 different situations under preliminary examination.

“My mission was to establish an Office of the Prosecutor to implement a judicial mandate in what was a political field.”

I aim to contribute to the study of an innovative and unprecedented legal system, facilitate a dialogue between experts and scholars, discuss new tactics to manage conflicts, and improve the teaching of international law and international relations.

The book’s first part introduces the Rome Statute and its relationship with the War on Terror, the circumstances of my appointment, and our strategy to build the Office of the Prosecutor’s foundations. Taking the Jus ad Bellum classification as an analogy, I proposed to label the norms defining the intervention of International Criminal justice into sovereign states as Jus ad Curiam.

Second part: our decisions to open investigations in four different states parties (Democratic Republic of Congo, Uganda, Central African Republic, and Kenya), the discussion on peace negotiations and the interest of justice, and our preliminary examinations in nine situations under our treaty jurisdiction (Venezuela, UK personnel involved in Iraq, Palestine, Guinea, Nigeria, Honduras, Colombia, Korea, and Georgia).

Third part: the ICC’s interaction with the UN Security Council in states non-parties like Iraq, Sudan, Libya, Ivory Coast, and Syria, and with the US in the Afghanistan situation.

The fourth part includes a summary of the Office of the Prosecutor’s Jus ad Curiam practice, the War on Terror’s policy redefining jus ad Bellum, including military interventions in countries not at war with the US, and the UN Security Council’s jus ad Curiam and jus ad Bellum decisions.

I also offer my observations: the outcomes of normative conflicts are in a consequential blind spot.

No chaos, just complexity: a fragmented international legal systemThe operational international legal order includes multiple subsystems working simultaneously, conferring power to various authorities, and prescribing different and sometimes opposite solutions to the same case.

“Still, there is no comprehensive academic field integrating the different authorities’ decisions.”

Anne Marie Slaughter proposed a “New World order” based on networks and David Kennedy explained how decisions are made: “The internationalization of politics means the legalization of politics. Every agent of the state, of the city, of the region, acts and interacts on the basis of delegated powers, through the instruments of decision and rule and judgment.”

Still, there is no comprehensive academic field integrating the different authorities’ decisions. International relations, political science, international law, international criminal law, humanitarian law, and military strategy scholars analyze variables in isolation. They deny fundamental problems to protect their field boundaries. Knowledge is produced within “echo chambers” according to nationality and expertise.

The International Law Commission’s report on Fragmentation described the evolution “from a world fragmented into sovereign States,” integrated under the UN Security Council on international peace and security “to a world fragmented into specialized ‘regimes.’”

The Rome Statute and the War on Terror are the twenty-first century “specialized regimes” to manage international crimes and terrorism. They are two antagonistic legal models conferring power to different authorities and influencing states and the UN Security Council decisions.

Quoting French Professor Mireille Delmas-Marty, “these are indeed legal, and therefore normative, interactions.” There is no chaos, just complexity.

From my office at The Hague, I perceived how other authorities, following their interests, selected the norms to apply. Perpetrators of massive atrocities followed instructions and rules, and diplomats and intelligence services worked to consecrate their impunity.

“War crimes, crimes against humanity, and aggression crimes are the consequence of a fragmented and contradictory international legal system.”

The crimes examined during my tenure were not the direct consequence of individual cruelty or the lack of respect for the norms. The leaders’ commands triggered institutions to act.

The decision to launch the War on Terror promoted efforts to protect the US troops and its allies and became a critical obstacle to international justice. The aggression crime committed in Ukraine exacerbated the problem.

Obstructing justice would be regarded as a crime at the national level. Still, political leaders have the legal authority to interfere with criminal justice in the international field and to instruct diplomats and intelligence agencies to do it.

War crimes, crimes against humanity, and aggression crimes are the consequence of a fragmented and contradictory international legal system. There is a failure by design.

March 16, 2023

Scars on the Land: Slavery and the environment in the American South [extract]

Scars on the Land: Slavery and the environment in the American South [extract]

Although typically treated separately, slavery and the environment naturally intersect in complex and powerful ways, leaving lasting effects from the period of emancipation through modern-day reckonings with racial justice. David Silkenat’s Scars on the Land provides an environmental history of slavery in the American South from the colonial period to the Civil War. The below extract from his book, sets the scene and considers how the environment shaped the lives of enslaved people.

A fugitive from bondage in Mississippi, William Anderson observed in 1857 that “it is almost impossible for slaves to escape from that part of the South, to the Northern States. There are a great many things to encounter in escaping, vis: large and small rivers, lakes, panthers, bears, snakes, alligators, white and black men, blood hounds, guns, and, above all, the dangers of starvation.” In enumerating the many barriers to freedom, Anderson lumped together natural and human obstacles. He understood that slavery’s shackles were not just man-made; enslaved people toiled in an environment that conspired with slave owners to keep African Americans in bondage. At the same time, Anderson and other enslaved people knew the Southern environment in a way their enslavers never could. By day, they plucked worms from tobacco leaves, trod barefoot in the mud as they hoed rice fields, and felt the late summer sun on their backs as they picked cotton. By night, they clandestinely took to the woods and swamps to trap opossums and turtles, to visit relatives living on adjacent plantations, and to escape to freedom.

“While environmental destruction fueled slavery’s expansion, no environment could long survive intensive slave labor.”

While the Southern environment provided the context for the peculiar institution, enslaved labor remade the landscape. One simple calculation had profound consequences: rather than measuring productivity based on outputs per acre, Southern planters sought to maximize how much labor they could extract from their enslaved workforce. They saw the landscape as disposable, relocating to more fertile prospects once they had leached the soils and cut down the forests. The expanding enslaved frontier irrevocably transformed the environment. On its leading edge, slavery laid waste to fragile ecosystems, draining swamps and clearing forests to plant crops and fuel steamships. On its trailing edge, slavery left eroded hillsides, rivers clogged with sterile soil, and the extinction of native species. Although the precise mechanisms and effects varied in Virginia’s tobacco fields, Louisiana’s swamps, and North Carolina’s pine forests, slavery exacted the same swift price. The scars manifested themselves in different ways, but the land too fell victim to the slave owner’s lash.

Slavery more than nature defined the South as a region. Geographers have identified dozens of distinct ecosystems within the American South, encompassing a vast variety of soil types, weather patterns, and biota. Two centuries of human bondage cemented these diverse biomes into a distinct cultural region. When they sought to establish a slaveholders’ republic in 1861, Southern partisans saw enslaved labor as the thread that linked the Eastern Coastal Plain, the Appalachian Piedmont, and the Mississippi Delta. “The South is now in the formation of a Slave Republic,” wrote L. W. Spratt, the editor of the Charleston Mercury, in February 1861. Its commitment to human bondage defined “the South as a geographical section” and provided what Confederate vice president Alexander Stephens described as the “cornerstone” of the new republic. Its advocates championed the South’s ecological diversity as an asset, one that enslaved labor could exploit. “What a soil, and climate, and variety of productions,” boasted Daniel M. Barringer in April 1861, shortly after the firing on Fort Sumter. Urging his fellow North Carolinians to join the newly established Southern Confederacy, Barringer saw its future in the expanding slave frontier, where “almost everywhere an inviting soil, capable of every variety of production and, in many portions of the Confederacy, still of virgin fertility—with every good climate of the world, and very little of the bad.” For Spratt, Stephens, Barringer, and other Confederate nationalists, slavery undergirded the world they hoped to defend. As historian Ira Berlin has observed, the ethos of a slave society infused and infected all aspects of its social order: law, family, custom, religion, politics, and art. Slavery also shaped how white and Black Southerners came to view the land itself and their relationship to it.

March 15, 2023

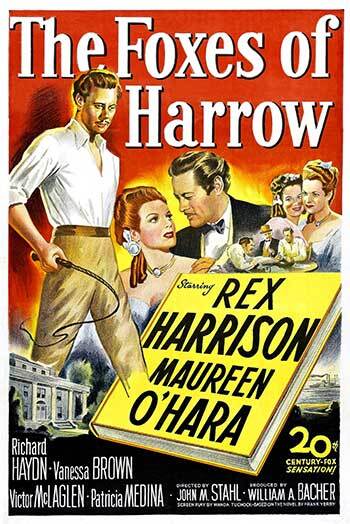

A Black Irish-American rejoinder to Gone With The Wind: Frank Yerby’s The Foxes of Harrow

A Black Irish-American rejoinder to Gone With The Wind: Frank Yerby’s The Foxes of Harrow

The Foxes of Harrow (1946), a Southern historical romance by Black Irish-American author Frank Yerby (1916–1991), writes back to Margaret Mitchell’s bestselling novel, Gone with the Wind (1936; hereafter GWTW). Although Yerby and Mitchell were both raised in Georgia during segregation by mothers of Irish descent, their socially assigned racial identities created divergent approaches to representing the pre- and post-Civil War South in their respective novels.

GWTW was (and remains) controversial for opening with a vision of an antebellum world of grace and for a plotline that justifies the KKK as needed protection from the sexual predation of white women by formerly enslaved men in the Reconstruction South. A break-out bestseller, Foxes kick-started a historical novel-writing career that made Yerby America’s highest-earning novelist by 1954. As with GWTW, Yerby’s novel covers the rise and fall of white Southern fortunes, but markedly departs from Mitchell in centering three-dimensional African-American characters and in its positive depiction of Reconstruction. Nevertheless, both romances feature penniless, “off-white” planters of Irish birth who transform themselves into the white exploitative landowner class to whom they themselves had once been subject: Gerald O’Hara in GWTW and Stephen Fox in Foxes. Only Yerby’s Irish planter ultimately understands the connections between these contexts, however.

As a young man in Ireland, Mitchell’s Gerald murders an oppressive landlord’s agent in disordered colonial Ireland and subsequently flees. Arriving in the South in the 1820s, O’Hara acquires both his first enslaved man and a neglected plantation in Georgia in games of poker, and further “whitens” by marrying into the local elite. These plot points almost all repeat in Foxes, but in an insightful departure from the easy interpretation of Yerby as merely derivative, Mark C. Jerng calls his novel “a prequel to GWTW that centers on the Gerald O’Hara figure.” (Mitchell moves from an opening emphasis on Gerald to center his daughter, Scarlett, for much of the action.)

Yerby’s negotiation of his dual heritages is apparent in Stephen’s “guttersnipe” Dublin street urchin beginnings, which challenges the certainties of the South’s black-white binary as much as the novel’s many mixed-race and racially ambiguous (“swarthy”) French characters. Yerby writes accessible fiction in the Mitchell mode, but simultaneously debunks what Du Bois had indicted as the “southern white fairytale” of graceful plantation life. In a Foxes scene that anticipates a similar event in Toni Morrison’s Beloved (1987), the unfree Sauvage attempts to take her baby with her when she commits suicide, exposing the stark reality of the desperation created by enslavement. By contrast, Mitchell propounds the “cherished darky” myth by having Scarlett claim that “house slave” Peter is “‘family,’” though this claim is certainly not meant to suggest interracial ties of the sort depicted by Yerby! (Indeed, the impossibility of Irish-African hybridity in GWTW’s sealed white supremacist universe is mocked by Alice Randall’s 2001 parody, The Wind Done Gone, in which Scarlett turns out to be mixed-race.) Although Yerby had a predominantly white mainstream readership and his marketing in the South evaded the issue of his racial identity, he deviates most from Mitchell in depicting rebellious, articulate, and prominent African-American characters, particularly those on the enslaved Caleen’s matrilineal line.

Foxes of Harrow starring Maureen O’Hara film poster used by permission of Alamy

Foxes of Harrow starring Maureen O’Hara film poster used by permission of AlamyWhen read without the blinders of caste, gender, and the patrilineal, Foxes turns out to be a novel of Caleen’s surname-less matrilineal line as much as Stephens’s “legitimate” line. Caleen, the shrewd materfamilias of Harrow’s enslaved cohort, upon whose knowledge of weather and medicine Stephen relies, is everywhere in the action and is its seditious centre: she teaches her grandson, Inch, reading and passwords for the Underground Railroad, and he ultimately makes a bid for freedom. Caleen makes herself indispensable to Stephen, but all the while she strategizes for her family and its future, as protective of bloodline as any white planter. The dynastic lines of Caleen and Stephen converge at the close with Cyrus, Stephen’s son by his mixed-race Creole mistress, Desiree. Young Cyrus becomes Inch’s stepson when the latter marries the boy’s mother in the Reconstruction era, a repudiation of the racially “pure” bloodline that underpins the antebellum logic of Mitchell’s novel.

Mitchell’s planter sees no connection between the sectarian oppression in Ireland that he had fled and the South’s slave system. Fox’s street origins, by contrast, are an implicit source of his ambivalent view of that way of life. Indeed, Yerby puts words in his planter’s mouth of the sort likely never before uttered by “the master” in a Southern plantation romance: “‘slavery is a very convenient and pleasant system – for us…I have my leisure, which I haven’t earned, and my wealth, which I didn’t work for…’” Mitchell’s Gerald justifies his acquisition of plantation and human chattel as the hunger “of an Irishman who has been a tenant on the lands his people once had owned.” Likewise, Stephen flees Ireland to gain “freedom,” but his final words in Foxes—as his plantation is threatened by the war and the hunger of his Dublin street days returns—suggests a reluctant understanding of the costs paid by others for his freedom that is entirely absent from GWTW: “‘For a little while, we lived like gods. I’m not sure that it was good for us.’”

Sir Stanley Wells and the First Folio

Sir Stanley Wells and the First Folio

This year marks the 400th anniversary of the publication of the First Folio of William Shakespeare’s plays. So called because of its plush page-size (roughly, 8.5 by 13 inches), the book got a sniffy reception in some quarters. Drama was usually deemed too vulgar for such publication, and one bishop complained its pages seemed a better quality than many bibles. None the less, the Folio has since acquired the status of a cultural touchstone, and the 235 copies known to survive are now treated like holy relics.

It’s often been difficult to dispel this reverence and distinguish an actual author behind it. For enabling many readers to accomplish that, we have to thank Sir Stanley Wells, general editor of the Oxford Shakespeare and Emeritus Professor of Shakespeare Studies at Birmingham University. His diligent and common-sense scholarship has done much to de-mystify Shakespeare and reposition the plays as working documents. With its text running in parallel columns, a eulogy by Ben Jonson, and Droeshout’s now-iconic portrait of Shakespeare, the Folio was very much a costly gentleman’s volume, to be admired, mused over, or perhaps (as some annotated copies show) used for dainty drawing-room entertainment. Sir Stanley’s achievement has been to point out that the texts were never intended for such refined use. Whatever their poetry, these are public pieces, demanding production. Staging and pacing are essential for their full effect. Shakespeare wrote them, as it were, in rooms always lacking the fourth wall. He was constantly aware of the faces either side of the footlights: a paying audience hungry for romance, comedy, bloodshed, the supernatural, and great historical figures brought to life, but also an onstage cast which had to engage and satisfy that appetite. Any good editor should honour those practical imperatives lodged at the heart of the text, which can only emerge with its rehearsal and delivery: there is always, as Sir Stanley notes in one essay, “the unwritten dimension … the fact that Shakespeare necessarily and consciously left something to hisactors.”In that respect, the plays resemble musical scores. They aren’t simply abstract exercises or conceits, but represent both a basis and a framework for gesture, expression, and carefully gauged response.

Even so, the Folio remains a landmark work. It published 36 plays, half of which existed in no other form. Without it, we might only remember Macbeth or Julius Caesar as titles, like Cardenio, a work written with John Fletcher but now apparently lost for good. Beyond that, however, the text represents an editorial nightmare. Though fondly assembled by his colleagues seven years after Shakespeare’s death, the Folio ignores collaborations like The Two Noble Kinsmen (now an Oxford World’s Classic), imposes its own act and scene divisions, and loses any sequence of composition by grouping the plays into thematic clusters. Inconsistently, the editing also tries to fend off questionable texts which had circulated from stolen prompt-books or audience transcriptions made during Shakespeare’s life-time, but probably introduces personal readings and allows running corrections throughout the print run, so that no two copies of the Folio are precisely alike.

“We celebrate the First Folio, but as Sir Stanley Wells reminds us, the text is both more and less than it might at first appear.”

The Civil Wars and Cromwellian England interrupted any continual tradition of performance, and later productions confused matters even further by employing the Folio and other, more unstable editions as a grab-bag of rhetoric and effect. The lack of any play in Shakespeare’s own hand meant authoritative readings were hard to establish. That absence left his posthumous corpus wide open to error, corrupt adaption, or lazy wishful thinking, and its misattribution to Bacon and others has been a deluded consequence of the chaos.

Sir Stanley has helped to clear up this mess. His objective was an Oxford Shakespeare based on scholarly principles, without any attempt to distort the text. Previous editions, from publishers like Penguin or Four Square, had run into inertia and editorial caprice, or were hampered by outmoded scholarship. Marshalling fresh academic insight, and drawing on the resources of the Oxford English Dictionary, Sir Stanley has clarified the texts and their production. This also informed his huge enthusiasm for Sam Wanamaker’s extraordinary reconstruction of the Globe Theatre, and we all now have a much clearer view of Elizabethan stage-craft, including the management of ghosts, murder, and mutilation—in Northrop Frye’s memorable phrase, “the problem of getting all this meat off the stage.” Through close analysis and re-enactment, a modern public has been brought closer than ever to Shakespeare’s original intentions, and to the playwright’s life. Anyone interested in that should consult Sir Stanley’s excellent Very Short Introduction on the subject.

So, we celebrate the First Folio, but as Sir Stanley Wells reminds us, the text is both more and less than it might at first appear. Our reception of it, as readers and audiences, continues to evolve with each re-interpretation. There is, in the end, no final, definitive Shakespeare.

Featured image: “Shakspeare from the First Folio Edition”, John Swaine (1775–1860), Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Fund (public domain)

March 10, 2023

Five books to celebrate British Science Week 2023

Five books to celebrate British Science Week 2023

British Science Week is a ten-day celebration of science, technology, engineering and math’s, taking place between 10-19 March 2023. To celebrate, join in the conversation, and keep abreast of the latest in science, delve into our reading list. It contains five of our latest books on plant forensics, the magic of mathematics, women in science, and more.

1. Planting Clues: How Plants Solve Crimes

Discover the extraordinary role of plants in modern forensics, from their use as evidence in the trials of high-profile murderers such as Ted Bundy to high value botanical trafficking and poaching.

In Planting Clues, David Gibson explores how plants can help to solve crimes, as well as how plant crimes are themselves solved. He discusses the botanical evidence that proved important in bringing a number of high-profile murderers such as Ian Huntley (the 2002 Soham Murders), and Bruno Hauptman (the 1932 Baby Lindbergh kidnapping) to trial, from leaf fragments and wood anatomy to pollen and spores. Throughout he traces the evolution of forensic botany, and shares the fascinating stories that advanced its progress.

Buy Planting Clues, How Plants Solve Crimes

Take a look at Gibson’s blog on Environmental DNA , as well as John Parrington’s (author of ‘Mind Shift’) blog on what neuroscience can tell us about the mind of a serial killer.

2. The Spirit of Mathematics: Algebra and all that

What makes mathematics so special? Whether you have anxious memories of the subject from school, or solve quadratic equations for fun, David Acheson’s book will make you look at mathematics afresh.

Following on from his previous bestsellers, The Calculus Story and The Wonder Book of Geometry, here Acheson highlights the power of algebra, combining it with arithmetic and geometry to capture the spirit of mathematics. This short book encompasses an astonishing array of ideas and concepts, from number tricks and magic squares to infinite series and imaginary numbers. Acheson’s enthusiasm is infectious, and, as ever, a sense of quirkiness and fun pervades the book.

Buy The Spirit of Mathematics, Algebra and all that

To learn more, discover our Very Short Introductions series, including editions about Geometry, Algebra, Symmetry, and Numbers.

3. Not Just for the Boys: Why We Need More Women in Science

Why are girls discouraged from doing science? Why do so many promising women leave science in early and mid-career? Why do women not prosper in the scientific workforce?

Not Just For the Boys looks back at how society has historically excluded women from the scientific sphere and discourse, what progress has been made, and how more is still needed. Athene Donald, herself a distinguished physicist, explores societal expectations during both childhood and working life using evidence of the systemic disadvantages women operate under, from the developing science of how our brains are—and more importantly aren’t—gendered, to social science evidence around attitudes towards girls and women doing science.

Buy Not Just for the Boys, Why We Need More Women in Science

Make sure not to miss Athene Donald’s limited 4-part podcast series featuring Donald in conversation with fellow female scientists and allies about the issues women face in the scientific world.

4. Distrust: Big Data, Data-Torturing, and the Assault on Science

Using a wide range of entertaining examples, this fascinating book examines the impacts of society’s growing distrust of science, and ultimately provides constructive suggestions for restoring the credibility of the scientific community.

This thought-provoking book argues that, ironically, science’s credibility is being undermined by tools created by scientists themselves. Scientific disinformation and damaging conspiracy theories are rife because of the internet that science created, the scientific demand for empirical evidence and statistical significance leads to data torturing and confirmation bias, and data mining is fueled by the technological advances in Big Data and the development of ever-increasingly powerful computers.

Buy Distrust, Big Data, Data-Torturing, and the Assault on Science

Check out Gary Smith’s previous titles, including: The Phantom Pattern Problem , The 9 Pitfalls of Data Science , and The AI Delusion .

5. Sentience: The Invention of Consciousness

What is consciousness and why has it evolved? Conscious sensations are essential to our idea of ourselves but is it only humans who feel this way? Do animals? Will future machines?

To answer these questions we need a scientific understanding of consciousness: what it is and why it has evolved. Nicholas Humphrey has been researching these issues for fifty years. In this extraordinary book, weaving together intellectual adventure, cutting-edge science, and his own breakthrough experiences, he tells the story of his quest to uncover the evolutionary history of consciousness: from his discovery of blindsight after brain damage in monkeys, to hanging out with mountain gorillas in Rwanda, to becoming a leading philosopher of mind. Out of this, he has come up with an explanation of conscious feeling—”phenomenal consciousness”—that he presents here in full for the first time.

Buy Sentience, The Invention of Consciousness (UK Only)

As an added bonus, you can also read more on the topics of evolutionary biology, the magic of mathematics, and artificial intelligence with the Oxford Landmark Science series. Including “must-read” modern science and big ideas that have shaped the way we think, here are a selection of titles from the series to get your started.

You can also explore more titles via our extended reading list via Bookshop UK.

March 9, 2023

The hidden and fraught development of an International Peace Architecture

The hidden and fraught development of an International Peace Architecture

The historical evolution of peace has led to the development of a substantial International Peace Architecture (IPA). This often-ignored architecture represents a wide set of frameworks, concepts, and methods, which span the balance of power, diplomacy, mediation, peacekeeping, civil society peacemaking, as well as development and peacebuilding. It also includes institutions and laws designed to prevent violence, end wars, and sustain a long-term peace based upon more than victory. The development of the IPA ultimately points to a peace with justice. Also of great significance have been social movements, civil society, and global networks of peace activists.

However, the IPA’s historical development has overall been very slow, hidden, and fraught. Its main historical stages or layers are now becoming clearer:

1. The ancient to medieval period

The ancient to the medieval period saw the development of the victor’s peace, wise governance to avoid war, truces and treaty-making to end wars, and the realization of the advantages of achievement of prosperity. It also saw a growing role for religious and social movements, which preached philosophical pluralism and pacifism.

2. The Enlightenment

The Enlightenment added a concern with domestic and international law and norms to govern state behaviour, the liberal social contract (the constitutional peace), social movements for anti-slavery, enfranchisement, disarmament and pacifism, labour movements, human rights, and free trade.

3. The modern period

Whilst the modern period saw these interests extend into social and gender issues, as well as equality and social justice (which is known as the civil peace) it also saw the emergence of international organizations, law, and conventions, forming an institutional peace. Other peace-related mechanisms also emerged in the context of decolonization and the collapse of the Soviet Union, including self-determination, development, aid, democratic peace, and trade. This became known as the liberal peace and appeared to some to represent the end of a long journey of political evolution.

To maintain the liberal peace, peacekeeping, various approaches to peacemaking, humanitarian intervention, liberal peacebuilding, development, and state-building were developed, along with processes of transitional justice, in post-conflict countries around the world. Over time all of these developments have coalesced into a comprehensive international peace architecture, complex, reactive, and fragmentary, but significant, nonetheless.

On the recent return of militarised authoritarian nationalism with Russia’s war in Ukraine in 2022, its apparent alliance with China and other regional powers, and with nationalist ideologies competing with Western versions of liberal peace, there are now major questions about whether the IPA remains adequate, however. There is also the question as to what version of peace and international order the global south might prefer, given that they were not fully supportive of the liberal peace model.

New agendas and the IPAThe older notion of a victor’s peace still plays an important role as a foundational layer of the IPA. Peacemaking and the complex machinery it requires has advanced considerably throughout history, even though it remains far from ideal. When confronted with transnational problems and political tensions which relate to inequality, environmental unsustainability, injustice, the arms trade, human trafficking, nuclear proliferation, urban conflict, and the use of new technologies, new agendas for peace are emerging.

As peace systems have become more complex, with new layers and tools being added as conflict, violence, and war evolve, they have also become more costly and require more political will to maintain.The liberal peace model of the twentieth century was a significant attempt to move beyond cruder versions of the victor’s peace, by focusing on democracy, human rights, development, and free trade, and placing the West as the leader of the IPA. This has provided the basis for the bulk of post-Enlightenment advances in peace thinking and practices. Similarly, an important layer of the IPA dealt with expanded (ECOSOC) rights after industrialized warfare ended in 1945 and decolonization thereafter. This was all consolidated in the most recent stage of the IPA, the liberal peacebuilding system (often now known as the Liberal International Order), after the end of the Cold War.

“A new layer of the IPA is now required to deal with new war and conflict dynamics, and to respond to widespread social demands for a form of peace more closely connected with justice.”

However, after failures in peacekeeping and peacebuilding across countries such as Somalia, Rwanda, and in the Balkans, and with the start of the War on Terror in the aftermath of 9/11, the IPA began to be dominated by a more limited neoliberal statebuilding framework in a new stage. This was applied in Afghanistan and Iraq, and failed to bring peace, justice, or stability. Given the failures in the 2010s and onwards in other cases such as Libya, Syria, Yemen, and Afghanistan, the next stage of the IPA is as yet undetermined. It must stabilize many frozen conflicts and open wars, from Syria to Ukraine, as well as deal with new phenomena and technologies in warfare (AI and automated weapons, proliferation of small arms and worse, hybrid warfare, urban violence, and more), as well as the older forces of nationalism, populism, inequality, authoritarianism, and environmental unsustainability.

Thus, a new layer of the IPA is now required to deal with new war and conflict dynamics, and to respond to widespread social demands for a form of peace more closely connected with justice. This process will probably not lead to a world government (to the disappointment of some liberal internationalists and the relief of others attuned to nationalism, political, and identity differences), but instead may indicate a world community made up of interlocking, pluralist, or “pluriversal” “peaces”: a “Grand Design” to quote the Duc de Sully (1560‒1641), a seventeenth-century philosopher. It may include different types of states, institutions, and norms, as well as new transnational and transversal networks that include official, civil, and social actors and groups. From a scholarly perspective, it would need to reaffirm that only cooperation, inclusivity, pluralism, and redistribution can maintain an ever-evolving IPA and thus a peaceful, just, and sustainable international order.

Featured image by Chris Liverani via Unsplash (public domain)

March 8, 2023

Women in the history of linguistics—from marginalization to recognition

Women in the history of linguistics—from marginalization to recognition

Women’s History Month raises issues of erasure and marginalization, authority and power which, sadly, are still relevant for women today. Much can be learnt from the experience of women in the past. We find inspiring stories of women who overcame prejudice and constraints of all kinds and who sometimes managed to gain recognition from their peers, only to be excluded from the history of their discipline.

In the field of linguistics, this marginalization relates to some extent to what is today considered part of linguistics and the current valuing above all of theoretical work. Words matter: a broader definition of linguistics allows women across the centuries to be included in this scholarly field. Given the cultural and practical limitations imposed on their access to education across all cultures, we need to look outside more institutionalized and traditional frameworks to discover the contributions made by women to the study of language structure and function.

“Words matter: a broader definition of linguistics allows women across the centuries to be included in this scholarly field.”

Classic histories of linguistics, very rarely, if ever, include women scholars. We set about uncovering the contribution of women linguists—from European and non-European traditions— and their ideas and writings to give them the recognition they deserve. A group of equally motivated and determined scholars joined us in our quest. We looked for names, works and ideas, especially in those liminal spaces not reached by official historiography, that is, outside institutions, universities, and academies in more private and domesticated spaces. We decided to challenge categories and concepts devised for male-dominated accounts and expands our field of enquiry: we turned our attention not only to pioneers and exceptional women, but also to those non-exceptional women who nevertheless quietly moved forward our knowledge of languages, their description, analysis, codification and acquisition. Painstaking research in archives and libraries, looking at manuscripts and printed sources, gradually unearthed rich, fascinating, and often unexpected evidence of women’s contribution.

For the earlier periods, it was difficult to find women who published grammars or dictionaries, but they did exist. Marguerite Buffet in seventeenth-century France wrote a volume of observations on the good usage of French specifically aimed at women (Nouvelles observations sur la langue françoise, 1668). Similarly, in 1740, Johanna Corleva published a Dutch translation of Port-Royal’s celebrated general and rational grammar. In Portugal, in 1786, Francisca de Chantal Álvares produced a compendium of Portuguese grammar for female pupils in convent schools, the Breve Compendio da Gramatica Portugueza para uso das Meninas que se educaõ no Mosteiro da Vizitaçaõ de Lisboa, at a time when the majority of women did not have access to formal education. Further afield, women missionaries were also active in the field. Gertrud von Massenbach joined the Sudan Pioneer Mission in 1909, as a teacher of mathematics in Aswan, in Nubian territory. Her linguistic interests led her to publish a dictionary with a grammatical introduction of Kunûzi Nubian (Wörterbuch des nubischen Kunûzi-Dialektes mit einer grammatischen Einleitung, 1933) and a collection of Nubian texts (Nubische Texte im Dialekt der Kunuzi und der Dongolawi, 1962).

“We need to look outside more institutionalized and traditional frameworks to discover the contributions made by women to the study of language.”

But there is much more. Women were, for instance, the intended audience or dedicatees of some of the earlier vernacular grammars in Europe. The Gramática de la lengua castellana (1492) by Antonio de Nebrija, the very first printed grammar of a vernacular language in Europe, was commissioned by Queen Isabella I of Castile and, according to Juan de Valdés, was meant to be of benefit, “para las damas de la sereníssima doña Isabel” (“for the ladies-in-waiting of Her Very Serene Highness Queen Isabel”). Women were translators, language teachers, collectors of data on endangered languages, and creators of new scripts. In Jiangyong county (Jiāngyǒng xiàn) of Hunan (Húnán) province in China, a rural territory surrounded by mountains, the nǚshū script (“female script/writing”) was used and transmitted among village women for at least one and a half centuries: a variant of the Chinese script, it represents a significant example of Chinese women’s contribution to character invention and development.

Women also assisted male members of their families, or male colleagues, in their work as linguists. Lucy Catherine Lloyd (1834-1914), the sister-in-law of the German linguist Wilhelm Bleek, was his most important collaborator. Together they created the nineteenth-century archive of ǀXam and !Kung texts (today called the Digital Bleek and Lloyd), an invaluable resource for linguists working on Khoisan languages. Cinie Louw followed her husband Andrew Louw to South Rhodesia (today Zimbabwe) to work on the Morgenster Mission, learning the local language, Karanga, a Shona dialect, and becoming a fluent speaker. Their 1919 translation of the Bible into Karanga was a joint effort, preceded in 1915, by an important manual of the Chikaranga Language.

Other women’s linguistic work has been neglected or overshadowed, the men with whom they collaborated reaping the benefit of their efforts. The young Chiri Yukie (1903–1922) helped codify the oral tradition of the Ainu people of Hokkaido in northern Japan. Thanks to her bilingual and bicultural knowledge she was able to collect a wide range of oral performances, preserving them for posterity and making them accessible by translating them into Japanese. Her invaluable work ultimately ended up promoting, instead, the career of a prominent male academic who was awarded the Imperial prize for his work on the Indigenous language.

“Women’s personal and professional life cannot be separated in a way that has been possible for male scholars across the centuries.”

What came to light, piece by piece, through reading their personal stories, was the challenges women had to face in male-dominated academia. Women’s personal and professional life cannot be separated in a way that has been possible for male scholars across the centuries. Theirs are often tales of perseverance and determination. Take the example of Mary Haas, a stalwart of twentieth-century American Indian Linguistics and a central figure in the Boas-Sapir tradition, which laid the foundation for current language documentation practices. Haas found her marriage in 1931 to Morris Swadesh limited her opportunities both within linguistics and with respect to employment generally. Given the scarcity of academic appointments, she considered getting a teaching certificate to teach in public schools in Oklahoma to support herself and her fieldwork on Native American languages. However, as a married woman she was unlikely to get hired in a public school. Undeterred, she wrote to Swadesh asking for a divorce so that she might be able to support herself. Swadesh agreed. Their divorce was meant to allow Haas to pursue more avenues of employment, although her plans were ultimately interrupted by World War II.

Uncovering such stories proved complicated, but extremely rewarding. And the more we found, the more we have become convinced that there is still so much more to discover.

Read a free chapter from Women in the History of Linguistics on Oxford Academic.

Featured image from the cover of Women in the History of Linguistics by Wendy Ayres-Bennett and Helena Sanson.

Going out on an etymological limb

Going out on an etymological limb

I despise coy, punning titles, so familiar from newspapers, but constantly invent such myself. Be that as it may, today’s post is about the murky origin of the word limb. This word had the same form in Old English, except that it lacked b at the end: just lim. The parasitic b must have appeared in declension. For example, in the old plural, limu became limbu, or the excrescent b first emerged in the genitive and the dative: m, a labial sound, produced an illegitimate offspring, closely resembling its parent. Later, just because both m and b are labial, the second consonant was eliminated, as in dumb, comb, and so forth. There is, apparently, no way to please speakers. (Some such trickery must also have happened in the history of thumb; yet in thimble, we still pronounce b. Likewise, mb has stayed in assemble and crumble, but not in crumb.)

Limbs all over.

Limbs all over.(Via Pixabay, public domain)

It is always hard to discover the etymology of a word that has no related forms in other languages, but non-matching cognates, even though they are better than nothing, also cause trouble. The Dutch cognate of lim(b) is lid, corresponding to German Glied, and we wonder what to do with the difference between the final consonants (m and d). G- in Glied poses no difficulties: it is a remnant of the prefix ge– (compare English like and German g-leich). This old prefix often occurred and still occurs in collective nouns. Thus, German Berg is “mountain,” while Ge-birge refers to a mountain range. Likewise, the German for “brother” is Bruder, and its plural is Brüder, but “brethren” or “brothers united for some enterprise” are (or at least were in the past) called Ge-brüder. Therefore, it looks probable that Glied initially referred to all the “members” (limbs) of a body.

But we may go farther and risk suggesting that even without the prefix the root -lim/-lid had a collective meaning and that the prefix only reinforced the reference that was there to begin with. The Old English word (which had no prefix!) was neuter, and from that period, we know the phrase dēofles limu “devil’s limbs,” referring to a multitude. Not inconceivably, lim originated as a collective neuter plural. Such words were many. The question remains open, because the fourth century Gothic cognate (liþus; þ has the value of th in English thin) was masculine (not neuter), while Old Icelandic had both lim-r “limb” (masculine) and lim “branch” (neuter). Perhaps the neuter form lim once designated all the limbs of a body and all the branches of a tree, later developed the sense “an individual limb (branch),” and became masculine (limr). In Old Germanic, short i alternated with its long counterpart ī (that is why English has ridden, with short i, and ride, with the vowel going back to ī). In Icelandic, we find lími (í designates a long vowel) “a heap of brushwood; broom.” Once again, the reference is to a collective noun (“many limbs”).

Those interested in the relations between collective plurals and neuter nouns in the singular may consult my old post for 12 October 2011 “Were ancient wives women?” A few comments on my hypothesis appeared much later, and I have only now read them. Also, something is said about Sib there, the goddess discussed last week. Today, I would rather refer to community and family relations, rather than just family relations, but other than that, I have not read any refutation of my etymology of wife, though a long article about it (and not only a post in this blog), multiple references and all, was published long ago.

A perfect image of a collective plural.

A perfect image of a collective plural.(Via Pixahive, public domain)

Those musings must needs remain vague. Another problem is the difference between the final consonants: lim ends in –m, while the final root consonant in Gothic liþ is þ, corresponding to d in Dutch lid and in German Glied. The traditional approach to this difference is easy to guess. When such words occur, etymologists isolate a root (in this case, it must be li-) and call the final consonants extensions (unlike suffix, extension is a vague term, because extensions have no ascertainable functions: they are mere additions to reconstructed roots). Perhaps li-meant “to bend.” If so, el– in elbow may be related.

To explain why I am suspicious of extensions, though they have been sanctified by our best and most reliable etymological dictionaries, I’ll give an example from Modern English. Let us compare tip, tit, tid, tig, tick, and tiff. Compare the definitions: tip “pointed end; touch lightly; gratuity”; tit “teat; small horse”; tid (as in tidbit; the more common British form is or used to be titbit); tig “to touch lightly”; tick “an insect; to touch lightly”; tiff “a slight quarrel.” Those are late words, some of which of questionable or unknown origin. If they were recorded in our oldest texts, etymologists would unhesitatingly have isolated the root ti– “a small amount” and a series of extensions. Yet such a procedure will of course not occur to anyone looking at the list above. Why not? How is the root le– “to slip, vanish” different from my suggested root ti– “small”? Nothing prevents us from saying that in the phrases tit for tat or in tic-tac-toe we recognize the existence of some common “stems,” but were they instrumental in coining the words? This is the crucial question.

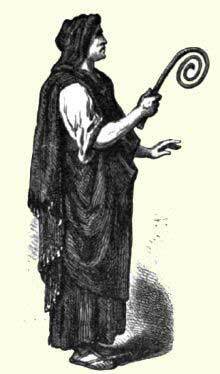

A lituus, an augur’s artificial limb.

A lituus, an augur’s artificial limb.(By Mariageorgieva0802, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

I assume that two or three thousand years ago, people formed words, just as they do it today. In the past, two names for “limb” competed: one began with lim– and the other with lith-. Supposedly, both the lith-word and the lim-word have cognates elsewhere. Latin lituus “a crooked staff borne by an augur” (incidentally, an obscure word, perhaps even a borrowing), Tocharian lit- “depart, fall down,” and Lithuanian liemuõ “depart, fall down” have been cited as possibly related to the Germanic forms. The connections are insecure and explain nothing about why just such sound groups were once upon a time chosen for denoting branches and other “limbs.” That is why the etymology of limb is “unknown.” Even forty thousand cognates cannot throw light on the origin of a word unless we are able to answer the main question: in this case, what is so “special” in the group lim- ~ lith– that it came to denote “limb.” No sound symbolism, no sound imitation.

Etymology is often a travel with no end in view. Here, we have lim-. It alternated with lith-. A few suspicious relatives showed up elsewhere. Perhaps in Germanic, the word initially designated all the branches of a tree and by extension, all the limbs of the body. It seems to have referred to something pliant, or bending. The impulse behind the coining remains undiscovered—just going out on a limb.

Editor’s note: the Oxford Etymologist will return on Wednesday 22 March.

Featured image by brewbooks via Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)

March 6, 2023

Marilyn Monroe goes to the Oscars

Marilyn Monroe goes to the Oscars

If the Academy Awards were very much a Hollywood institution in 1951, the awards ceremony itself, on 29 March of that year, was a far cry from the mega-productions of later years and today. The 23rd Oscar ceremony was held at the RKO Pantages Theatre—now known as the Hollywood Pantages Theatre—with a sort of “satellite” location at a New York restaurant to accommodate the nominees then on the East Coast. The ceremony was broadcast on radio but not television, a situation which would change with the first Oscar telecast two years later. Fortunately, the ceremony is not lost to us, since for years the Academy had been seeing to it that its awards presentation was filmed. Even better, the 1951 show was the first to be filmed in color and is available for viewing online.

In many ways, it was a capsule summary of the Oscar shows we still watch more than six decades later: a famous and well-liked host (in this case, Fred Astaire) reading scripted jokes, celebrity presenters, “Best Song” performers, and a buildup to the main events of the acting and Best Picture winners. In short, it’s never changed, except that it has: no big production numbers, a very modest set, and winners in so-called lesser categories not giving acceptance speeches. This, needless to say, kept the ceremony quite short.

The big winner that year was All About Eve, with six awards. One of those, Best Sound Recording, was the only Eve prize handed out by one of the film’s cast members. Although she’d had limited—if flashy—screen time in All About Eve, Marilyn Monroe was starting to launch a major career and had been spotlighted in the 1 January 1951 Life magazine as one of Hollywood’s “Apprentice Goddesses.” Six of those deities-in-waiting were called on to be Oscar presenters that year, and besides MM the roster included Debbie Reynolds, Arlene Dahl, Debra Paget, Phyllis Kirk, and Jan Sterling. For MM, then in the first year of her contract at Twentieth Century-Fox, it was a signal moment. With no further films yet on the professional horizon, she was feeling ignored by her studio and eager for opportunities. An Oscar appearance, even on the radio, would be great exposure, and Monroe was determined to make a major impression.

Unfortunately, a couple of factors could be seen as a hindrance. One was the evening gown Fox lent her to wear—a black concoction with an enormous full skirt and a rather strange network of netting that draped around her shoulders and, in the back, rose halfway up her head. It was, in fact, a hand-me-down, previously worn by Valentina Cortese in Fox’s The House on Telegraph Hill. Despite a smattering of sequins and the expected low neckline, it wasn’t what we think of as a vintage-Marilyn dress, not with that skirt. (She always wanted them much, much tighter.) A pair of dangling earrings and a couple of black hair clips completed the ensemble, and her hair was a few shades darker than the familiar color seen in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and The Seven Year Itch.

And, because it was Marilyn Monroe appearing before a live audience, there was also a major case of nerves. Backstage, as the show commenced, her panic ratcheted up to the crisis point when something (or someone) caused the net trim on her gown to rip. As her fellow presenters watched in horror, MM came close to falling apart completely. Gloria De Haven, Jane Greer, and Debra Paget rushed over to console her and, since malfunctions were as much of an issue in 1951 as in 2023, there was a wardrobe woman nearby with a needle and thread. After a hasty repair, MM found the means to pull herself together before Fred Astaire called her name.

“As in other moments in her career, Monroe had scored a public triumph after a rough private start.”

As the orchestra played “Oh, You Beautiful Doll,” Monroe glided serenely out onto the Pantages stage, deftly maneuvering the oversized skirt and giving no indication of the terror she’d been feeling. In her familiar throaty murmur, she carefully read the scripted list of nominees, her nervousness apparent only to those who wondered why she looked up only briefly in the course of her presentation. After calling the winner as All About Eve, she looked out at the audience with a big MM smile and walked over to greet Thomas C. Moulton of the Fox Sound Department, hand him his Oscar, and stride offstage with him arm-in-arm. Backstage, she posed with Moulton and alone, looking every inch the professional and, indeed, an Apprentice Goddess.

As in other moments in her career, Monroe had scored a public triumph after a rough private start. Yet, despite her successful appearance and the legendary stardom that would soon arrive, it would be the only time she ever attended the Academy Awards. It is, without question, Oscar’s loss.

March 5, 2023

Semantic prosody

When linguists talk about prosody, the term usually refers to aspects of speech that go beyond individual vowels and consonants such as intonation, stress, and rhythm. Such suprasegmental features may reflect the tone or focus of a sentence. Uptalk is a prosodic effect. So is sarcasm, stress, or the accusatory focus you achieve by raising the pitch in a sentence like “I didn’t forget your birthday.”

Scholars working with computer corpora of texts have extended the notion of prosody to aspects of meaning. The term “semantic prosody” was coined by William Louw in his 1993 essay “Irony in the text or insincerity in the writer: the diagnostic potential of semantic prosodies.” Building on work by John McHardy Sinclair, Louw used the term to refer to the way in which otherwise neutral words can have their meanings shaded by habitually co-occurring with other, positive or negative, words. He referred to it as a “semantic aura.”

How do you see the aura? Researchers use tools like the Key Word In Context (or KWIC) feature which produces a listing of collocates of a key word. As the term suggests, collocates are words that are co-located with the key word in the corpus and in some genre. Semantic prosody is not as in-your-face as a connotation, and as Louw’s title suggests, it can be used ironically. Perhaps because of this, dictionary definitions tend not mention prosodies in a word’s definition.

So, to take an example used by Susan Hunston of the University of Birmingham in her article “Semantic Prosody Revisited,” the word persistent often occurs with a following noun in negative contexts. We find examples like persistent errors, persistent intimidation, persistent offenders, persistent cough, persistent sexism, or persistent unemployment. That tone seems to carry over to examples like persistent talk or persistent reports. The reports and talk have a presumption of negativity to them. Hunston points out that persistent is not necessarily negative, however. One can be a persistent advocate, or a persistent suitor, or reach a goal by persistent efforts. Its aura comes from being often negative.

That carries over to the verb persist as well, I think. When Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren was silenced during a 2017 confirmation debate, the Senate majority leader’s comment that “She was warned. She was given an explanation. Nevertheless, she persisted.” was intended as a rebuke. Quickly, however, “Nevertheless, she persisted” and “Nevertheless, they persisted,” became a rallying cry of women refusing to be silenced and a renewed call to activism. The rebuke of “she persisted” was repurposed as defiance and determination.

Linguists are fascinated by phenomena like semantic prosody and the potential hidden patterns in language use. For writers who are not linguists, semantic prosody is worth pondering as one drafts and revises. How do our words shade our sentences with positive or negative associations? And how can we play with those associations to surprise readers.

Consider the example of break out, a two-word verb studied by Dominic Stewart in his 2010 book Semantic Prosody: A Critical Evaluation. What sort of things break out? Typically, it’s wars, crises, fires, conflicts, violence, insurrections, diseases, inflammations. As writers, we can reverse that tone with phrasings like “peace broke out” or “hope broke out,” giving peace and hope the sudden eruption often associated with negative events.

As readers, we ought to be aware of potential semantic prosody in the media we consume. When we encounter words like utterly, symptomatic, chill, threaten, rife, or give rise to, what subtle tones are being communicated to us? There’s not, as yet, a dictionary of semantic prosody where you can look up a word’s preferences, but you can certainly think about them.

Featured image by Pawel Czerwinski via Unsplash (public domain)

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers