Oxford University Press's Blog, page 56

March 5, 2023

Semantic prosody

When linguists talk about prosody, the term usually refers to aspects of speech that go beyond individual vowels and consonants such as intonation, stress, and rhythm. Such suprasegmental features may reflect the tone or focus of a sentence. Uptalk is a prosodic effect. So is sarcasm, stress, or the accusatory focus you achieve by raising the pitch in a sentence like “I didn’t forget your birthday.”

Scholars working with computer corpora of texts have extended the notion of prosody to aspects of meaning. The term “semantic prosody” was coined by William Louw in his 1993 essay “Irony in the text or insincerity in the writer: the diagnostic potential of semantic prosodies.” Building on work by John McHardy Sinclair, Louw used the term to refer to the way in which otherwise neutral words can have their meanings shaded by habitually co-occurring with other, positive or negative, words. He referred to it as a “semantic aura.”

How do you see the aura? Researchers use tools like the Key Word In Context (or KWIC) feature which produces a listing of collocates of a key word. As the term suggests, collocates are words that are co-located with the key word in the corpus and in some genre. Semantic prosody is not as in-your-face as a connotation, and as Louw’s title suggests, it can be used ironically. Perhaps because of this, dictionary definitions tend not mention prosodies in a word’s definition.

So, to take an example used by Susan Hunston of the University of Birmingham in her article “Semantic Prosody Revisited,” the word persistent often occurs with a following noun in negative contexts. We find examples like persistent errors, persistent intimidation, persistent offenders, persistent cough, persistent sexism, or persistent unemployment. That tone seems to carry over to examples like persistent talk or persistent reports. The reports and talk have a presumption of negativity to them. Hunston points out that persistent is not necessarily negative, however. One can be a persistent advocate, or a persistent suitor, or reach a goal by persistent efforts. Its aura comes from being often negative.

That carries over to the verb persist as well, I think. When Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren was silenced during a 2017 confirmation debate, the Senate majority leader’s comment that “She was warned. She was given an explanation. Nevertheless, she persisted.” was intended as a rebuke. Quickly, however, “Nevertheless, she persisted” and “Nevertheless, they persisted,” became a rallying cry of women refusing to be silenced and a renewed call to activism. The rebuke of “she persisted” was repurposed as defiance and determination.

Linguists are fascinated by phenomena like semantic prosody and the potential hidden patterns in language use. For writers who are not linguists, semantic prosody is worth pondering as one drafts and revises. How do our words shade our sentences with positive or negative associations? And how can we play with those associations to surprise readers.

Consider the example of break out, a two-word verb studied by Dominic Stewart in his 2010 book Semantic Prosody: A Critical Evaluation. What sort of things break out? Typically, it’s wars, crises, fires, conflicts, violence, insurrections, diseases, inflammations. As writers, we can reverse that tone with phrasings like “peace broke out” or “hope broke out,” giving peace and hope the sudden eruption often associated with negative events.

As readers, we ought to be aware of potential semantic prosody in the media we consume. When we encounter words like utterly, symptomatic, chill, threaten, rife, or give rise to, what subtle tones are being communicated to us? There’s not, as yet, a dictionary of semantic prosody where you can look up a word’s preferences, but you can certainly think about them.

Featured image by Pawel Czerwinski via Unsplash (public domain)

March 3, 2023

How to define 2022 in words? Our experts take a look… (part three)

How to define 2022 in words? Our experts take a look… (part three)

Heatwave, cost of living and queue—summer 2022 in wordsFrom booster to Platty Joobs, we’ve explored the first half of 2022 in words. The second half of the year was marked by a series of disasters—natural and economic—and our experts have taken a look at the words that sum up this turbulent time.

JulyThe extreme weather of July 2022 led to a surge in use of the word heatwave. In Portugal, temperatures reached 47°C in mid-July, while usage of the word spiked in British English sources as the UK experienced record temperatures of up to 40°C.

The Oxford English Dictionary’s (OED) first quotation of heatwave is from 1842. When it was first used, it normally referred to a wave of hot weather passing from one place to another. Now, we use it to describe a period of abnormally hot weather.

In July 2022, the word was almost 4.5 times more frequent in UK sources than the previous month.

The rest of the world experienced extreme weather events too, with catastrophic flooding in Pakistan, and wildfires and droughts around the world. These events were seen as a stark reminder of the impact of climate change and the unpredictability it is causing in global weather systems.

AugustOur term for August 2022 is cost of living.

The term is first recorded in the OED in 1796 and defined as “the general cost of goods and services viewed as necessary to maintain an average or minimal standard of living (such as food, housing, transport, etc.)” with a specific economics clause referring to “the average cost of such goods and services as measured by a representative price index.”

Frequency of the term gradually rose throughout 2022, with its usage increasing more than four-fold between December 2021 and August 2022, and levels staying high for the remainder of the year.

This increase was down to the economic situation that much of the world found itself in, with many people struggling with the cost of fuel and the price of basic necessities rising. Headlines included: “Fun is out as cost of living soars” (Courier Mail, 1 Aug 2022) and “Cost of living: How to cope with the rise in prices” (Independent, 31 Aug 2022).

That this situation was playing out around the world is reflected in the term’s usage too, which was geographically widespread and not restricted to any particular country or region.

A number of other terms related to the cost-of-living crisis saw increases in usage throughout the year, including energy crisis, fuel poverty, fuel crisis, permacrisis, and warm bank.

SeptemberAfter the passing of Queen Elizabeth II in September 2022, it was announced that Her Majesty’s coffin would lie in state for five days to allow mourners to pay respects to the late monarch.

This initiated the longest queue—our word for September—in British history, as more than 250,000 people waited patiently to make their way to Westminster Hall.

The queue caught the attention of the British and international media, with a live feed from the Palace of Westminster tracking its length and #TheQueue trending on Twitter. The word queue was used around 3.5 times more frequently than the previous month and year.

As a word, queue is borrowed into English from Anglo-Norman and Middle French, and derives from the Latin word cauda, meaning a tail (of an animal). It was first recorded in English in the fifteenth century with reference to ribbons or bands of parchment bearing seals and attached to a letter.

The earliest quotations for the queue that we all know today—“a line or sequence of people, vehicles, etc., waiting their turn to proceed, or to be attended to”—are found in a French context. Thomas Carlyle provided our first clearly English citation, writing in 1837 “That talent… of spontaneously standing in queue, distinguishes… the French People.” Since then, however, this has become a distinctively British word for what users of North American English would call a line.

Many of the words seeing a significant increase in usage in September 2022 were references to the death of Queen Elizabeth II. Monarch and monarchy, coffin, mourning and mourner, coronation, respects, corgi, and queen, which was recently chosen as the Oxford Children’s Word of the Year 2022, were all in the top ten words in our corpus which were significantly more frequent in September than the months before. Lying-in-state and catafalque (a platform on which a coffin is placed) saw a significant increase in usage too.

The only item in the top ten words for September not to relate to the death of HM The Queen is mini-budget. More to come on this word shortly…

March 1, 2023

Sib and peace

The title of this post reminds one of Tolstoy’s War and Peace, but it means “Peace and Peace.” Though the story is long and in some points incomplete, this need not worry us, because few etymologies are complete (here, our object of investigation will be sib), and in reconstructing the history of an old and partly obscure word, one can go only so far.

In Modern English, sib is a dead or almost dead word, but sibling has survived, and many people will also remember that gossip traces back to Old English god-sibb. This compound once meant “sponsor at baptism” (god– of course refers to God), but rather soon it deteriorated into “familiar acquaintance” and “idle talker.” The phrase old gossip “an old talkative woman, tattler” occurred in nineteenth-century literature with some regularity. For many years, dictionaries remained noncommittal with regard to the origin of sib, even though the wordhas close cognates all over the Germanic-speaking world (German Sippe, and so forth).

At present, the verdict in reference works has changed, though we are still warned that the situation remains partly unclear. In any case, the formulation “origin unknown” has all but disappeared from the entry sib. Somewhat unexpectedly, it remained in the 1966 Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology. Unexpectedly, because the original OED listed the cognates and stopped, wisely without adding the fateful phrase. The Century Dictionary and The Universal English Dictionary by Henry Cecil Wyld, two sources to which I refer with great regularity (their treatment of etymology deserves our respect), followed the example of the OED, that is, offered the obvious cognates and refrained from further conclusions.

Three gossips?

Three gossips?Photo by Yaroslav Shuraev, Pexels (public domain)

Let me begin with a story some of whose details are relatively little known outside the professional circles of mythologists. The old (that is, medieval) Scandinavians worshipped Thor, the thunder god. In the extant tales, Thor has nothing to do with thunder (he is a giant-killer and sometimes a foil to Odin), but his name does mean “thunder,” and his past of a sky god can be reconstructed with a high degree of certainty. (Now comes the denouement.) Among other things, he is married to a goddess named Sif. Almost nothing is said about this divinity, except that her name is an obvious cognate of sib. Consequently, she had something to do with contracts and unions.

The perfidious god Loki is said to have once cut her hair. How Loki dared do such a thing to Thor’s wife remains unclear. Later, he made amends, but cutting a woman’s hair might be a sign of her going to become married. Old English had a special word for the hair of a bride. In a late text (a song from the Poetic Edda), Loki brags of having slept with Sif. The truth of this scandalous assertion cannot be verified, but the author of the song may have drawn this conclusion from the hair-cutting episode.

Yet Sif appears, for whatever reason, to be Thor’s wife, and their union must have had some reason. We will soon see that this reason is hard to find. Long ago, it was observed that the great Vedic fire god Agni had the cognomen Sabhya, which was compared with Sif. The old attempts to connect the idea of lightning and fire with the concept of a family hearth seem strained, but nineteenth-century scholars tried to understand why Thor and Sif belonged together (according to myths, they did not only belong together but even had two sons) and believed that they had found a link. The main question for an etymologist is not Sif’s marital status but whether the ancient protoform of sib– (as in sibling) and Sif meant “family.”

A modern idea of Sif.

A modern idea of Sif.Image by Willy Pogony, Wikimedia Commons (public domain)

And this is where we are in for a surprise. In the Old Germanic languages, sib and its cognates meant “peace,” rather than “family.” The evidence at our disposal points unambiguously in this direction. In the fourth-century Gothic Bible, translated from Greek, sibja meant “relationship” (and this is the closest we come to the idea of “family”). The negative adjective un-sibjos glossed the Greek words meaning “unlawful” and “impious,” not “devoid or bereft of family”. In Old High German, Latin pax “peace” was glossed with sibbo, though frid, the ancestor of today’s Frieden, existed too. In Gothic, the noun with this root meant “reconciliation.” (Elsewhere in Germanic, the words with the root frid– referred to things beautiful and cherished.)

“Relationship” is a vague concept, and the main question is whether the Germanic words with the root sib- ~ sif- referred to a family or a broad community. Though opinions on this matter differ, it appears that “community” is a more secure choice. Individual ties often took precedence over those imposed by the family. (Incidentally, Romeo’s friend Mercutio, did not belong to ether clan; hence: “Plague on both your houses.”) If the preceding argument can be sustained, Sif, we conclude, did not protect family relations, regardless of who her husband was (at best, she took care of community ties), and the clever idea of her being a goddess of family ties or the family hearth must be given up. The root of Sif’s name recurs in several reflexive pronouns meaning “one’s own,” such as English self and German sich, with cognates in probably all Indo-European languages, while Agni disappears from out story.

A hearth, perhaps even a family hearth.

A hearth, perhaps even a family hearth.Image via PxHere (public domain)

The name for a close-knit community, rather than a group of family members, seems to underlie the English noun sib(ling), so thatthe word sib need not be defined as “related by blood.” Curiously, this word has all but disappeared from Modern English. The same happened to German Sippe and its cognates in the Scandinavian languages. German Sippe was revived in the eighteenth century and later used with a vengeance by the Nazis. English has also lost the native word for “peace.” As early as the twelfth century, a borrowing from French replaced it: peace goes back to Latin pax. In the Germanic-speaking world, the strangest word for “peace” occurred in Gothic: it had the root of the verb glossed as “to happen, to come to pass,” as in German werden (with the implication of “good thing happening”?) and had nothing to do with any of its synonyms elsewhere. “Peace” and “community” are sometimes called the same (so in Russian: mir “peace” and “world”). The root of German Frieden “peace” means “free” or “dear.” Despite the fact that people have always fought and killed one another in endless wars (and the Germanic-speaking people were certainly not an exception to this rule), peace was looked upon as the desired norm. In Old Scandinavian, an independent word for “war” did not even exist: people called hostilities (in translation) “un-peace.”

I should repeat that though the treatment of the Germanic nouns with the root sib– is a hotly disputed area, I gravitate toward understanding it as “community,” rather than “family,” and communities are formed for protecting peace, that is, for defending themselves from aggressors and suppressing internecine strife.

Featured image by Nomu420 via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Finding Jane Austen in history

Finding Jane Austen in history

2023 marks the 100th anniversary of the publication of R. W. Chapman’s OUP edition of The Novels of Jane Austen which dominated the market throughout the twentieth century. Recent years have seen calls to recover the unacknowledged contribution to its success of Chapman’s wife, Katharine Metcalfe.

Where Chapman scrutinized the Austen text inside a template derived from classical scholarship, suggesting its elucidation and elevation by comparison with Aeschylus and Euripides, the model provided by Metcalfe’s 1912 edition of Pride and Prejudice, Austen’s most celebrated novel, immersed the reader in a simulated Regency experience. Metcalfe undertook it after Walter Raleigh, first holder of the Chair of English Literature at Oxford, dissuaded her from writing a study of Mary Wollstonecraft.

Many features of Metcalfe’s edition now routinely inform the apparatus of a World’s Classics packaging of a classic novel; but in 1912 the approach was fresh. Facsimile title page and a restored first-edition text (the look of a nineteenth-century printed page) were supplemented with an appendix, “Jane Austen and her Time”, being notes on life in Regency England: “Travelling and Post”, “Deportment, Accomplishments, and Manners”, “Social Customs”, “Games”, “Dancing”, and “Language”. Chapman adopted them all.

Metcalfe’s contribution is best seen in the context of her historical moment. With a degree in English from Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford, she was among the first generation of female university graduates. In 1912-13, she was Assistant English Tutor at another of Oxford’s colleges for women, Somerville. Gender imbalance interacts complexly with genre: a matter of political and educational opportunities as well as hierarchies of readers and writers. Chapman dignified (or perhaps patronized) the female novelist by submitting her to the rigours of male classical textual criticism. In the early decades of the twentieth century, women graduates found intellectual space and a voice in sociological readings of literature and history. They found themselves in history by finding women from the past inside history.

“In the early decades of the twentieth century, women graduates found intellectual space and a voice in sociological readings of literature and history.”

The academic community of Somerville College was from the opening of the century to the outbreak of the Second World War a fertile ground for developments in feminist politics, Georgian history, and Austen studies. Margaret Kennedy, who went up to read History in 1915, was a contemporary at Somerville of second-generation suffragists, Hilda Stewart Reid, Winifred Holtby, and Vera Brittain. Kennedy was both historian (her first book, A Century of Revolution (1922), a study of the years 1789 to 1920) and historical novelist; she would publish a biography of Austen in 1950 and a general study of fiction, The Outlaws on Parnassus, in 1955. Holtby would write regional novels whose strong modern heroines champion social change. She lectured for the League of Nations Union and produced a feminist historical survey Women (1934), which included a section “The Importance of Mary Wollstonecraft”. Reid’s historical novel, Two Soldiers and a Lady (1932), set during the English Civil War, was praised in the New York Times for its “abnegation” of conventional history: “By deliberate concentration on what might, at first sight, appear to be historically of least importance the author has succeeded in reproducing the spirit of the period which determined the events” (18 September 1932, “Book Review”, p. 6).

Education and the social cataclysm of war propelled women into history. They saw that fiction might offer a space for mapping alternative histories and supplementing the official record. In 1923, as Chapman’s Austen appeared, Metcalfe published under her own name an edition of Northanger Abbey, though she adopted Chapman’s text.

Northanger Abbey is a novel in conversation with the novel as literary form, and it contains a famous critique of history. Its heroine, Catherine Morland, good-humouredly endures instruction from the hero Henry Tilney, but she is clear about the shortcomings of history books, what she calls “real solemn history”, in which women hardly feature at all. How can history exclude women’s lives, she asks, when so much that we take to be history consists of the colour, motives, and interpretation brought to its narration. Since “a great deal of it must be invention” it must be a kind of double fiction to exclude women from it (chapter 14).

“Writing from the margins of social history and literature, [women historians] set the past and present in dialogue.”

In the opening decades of the twentieth century, women historians (M. Dorothy George, English Social Life in the Eighteenth Century, 1923; Ivy Pinchbeck, Women Workers and the Industrial Revolution, 1750-1850, 1930) were at the forefront of developments in social and economic history to recover different kinds of past and to complicate the discourses of established history with a finer-grained, domestic, and moralized enquiry. Writing from the margins of social history and literature, they set the past and present in dialogue.

100 years ago these women were looking back 100 years. Jane Austen was a point of orientation. Recovered within a historical context rather than a purely affective one, Austen’s novels became amenable to new purposes. For Holtby it meant discovering why Virginia Woolf’s heroines could no longer “sit behind a tea-tray” (Virginia Woolf: A Critical Memoir, 1936, 91); for Woolf it meant celebrating Austen’s anarchic teenage voice (in “Jane Austen Practising”, The New Statesman, 19, 1922). Heard alongside their bold reimaginings, Katharine Metcalfe’s voice, too, sounds a new and confident note. “Two apparently contradictory impressions are left after reading Jane Austen’s novels”, she wrote, “a first impression of her old-fashionedness, a second of her modernness” (Pride and Prejudice, edited by K. M. Metcalfe, 1912, 389). Only for Chapman, ventriloquizing their socio-historical approach by sourcing contemporary engravings as set dressing to Austen’s novels—a Regency window curtain, a marble fireplace, naval uniforms of 1814—did it mean the past preserved in aspic rather than a challenge to the present.

Read Kathryn Sutherland’s “On Looking into Chapman’s Austen: 100 Years On” in The Review of English Studies. Available to read for free until 31 May 2023.

February 28, 2023

Women in sports: Althea Gibson, Billie Jean King, and their legacies [podcast]

Women in sports: Althea Gibson, Billie Jean King, and their legacies [podcast]

The world of sports has long been a contested playing field for social change. When Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in baseball in 1947, it was widely assumed that other heroic male athletes would follow in subsequent sports. So, when Althea Gibson—a young woman who grew up in Harlem playing paddle tennis—became the first Black athlete to win a major title in 1956, she shocked the tennis world. Women’s history in sports has in fact been a long series of shocks that have reshaped the world of athletics as well as the possibilities that exist for women everywhere.

On today’s episode, we discuss the lives, careers, and lasting legacies on and off the tennis courts of two great women athletes—Althea Gibson and Billie Jean King.

First, we welcomed Ashley Brown, the author of Serving Herself: The Life and Times of Althea Gibson, to speak about the barrier breaking tennis player and golfer. We then interviewed Susan Ware, the author of American Women: A Concise History, American Women’s History: A Very Short Introduction,and Game, Set, Match: Billie Jean King and the Revolution in Women’s Sports, published by UNC Press. Susan shared with us some background on how King leveraged her career as a form of activism for gender equality and discussed how sports have changed for women athletes in the years since.

Check out Episode 80 of The Oxford Comment and subscribe to The Oxford Comment podcast through your favourite podcast app to listen to the latest insights from our expert authors.

Oxford Academic (OUP) · Women in Sports: Althea Gibson, Billie Jean King, & Their Legacies – Episode 80 – The Oxford CommentRecommended readingYou can read the introduction from Ashley Brown’s book, Serving Herself, which explores how gender and sexuality were essential aspects to her history of integration.

Don’t miss this interview with Ashley Brown with a deeper discussion of why she chose to write about Gibson’s life.

To learn more about the Black women athletes who broke barriers in tennis, explore the Oxford African American Studies Center profiles of Althea Gibson, Zinna Garrison, Venus Williams, and Serena Williams.

Learn how Billie Jean King was the right woman at the right moment in American history, in the introduction to Susan Ware’s Game, Set, Match.

You can also learn more about the 20th century women’s movement in this chapter, “Modern American Women, 1920 to the present”, from Susan Ware’s American Women’s History

Featured image: Althea Gibson, half-length portrait, holding tennis racquet. Photograph by Fred Palumbo, 1956. Library of Congress, CC0 via Unsplash.

Five things musicians should know about the brain

Five things musicians should know about the brain

You may read the title of this blog post and wonder “why should musicians know about the brain?” Historically, there are thousands of musicians who have performed beautifully without knowing anything at all about the three-pound organ sitting atop the spine. But there are countless other individuals who may benefit from knowing some of the “brain basics” concerning music that have been discovered over the past few decades.

Music communicates emotion, but sometimes the failure to wire musical information securely in the brain during practice, or experiencing anxiety about technique or memory during performance causes emotional communication to suffer. Some knowledge of brain basics can help us study and teach with greater efficiency and confidence, thus giving us more freedom in performance to concentrate on communicating the emotional essence of the music. Consider the following:

1. We are hardwired for music as we are for languageInfants are born with amazing musical abilities. They can detect a missing downbeat at the age of two to three days and begin moving to music as soon as they have control of their limbs. They prefer singing to speaking, can recognize variations in complex rhythms at six months, and have a very good memory for music. Many of these abilities are lost by the age of one because they are not nurtured, as is the case with language. Perhaps we should rethink “how” and “when” we begin teaching music to children because music is part of who we are as human beings. Or as well-known music educator Edwin Gordon said, “Music is as basic as language to human development and existence.”

2. Practicing drives brain neuroplasticityWe all have similar brains, but each person’s brain develops in a unique way based on his learning and experience. For example, the brain of a cardiac surgeon will look a bit different from that of a musician. Many areas of the brain are involved in making music, including the areas for processing visual, auditory, kinesthetic, and motor information, as well as areas for processing emotion and memory. As we practice an instrument or voice, connections develop among all of these areas through vast neural networks, and our brains change as a result. The more we practice, the more the brain changes. These changes in the brain are called neuroplasticity. There are some ways of practicing that lead to stronger wiring or greater neuroplasticity in the brain, meaning increasingly better technical and musical skills and stronger memory for music.

3. Practicing happens in the brain, not in the musclesMotor imagery is a powerful practice technique that involves imagining all of the movements necessary to play or sing a piece of music. One hears the music in one’s mind and imagines making the movements to create the sound—“feeling” the movements in one’s mind. Research has shown that when we practice using motor imagery, all of the areas of the brain that would normally be involved when we physically practice are active—with the single exception of the motor cortex that sends signals to the muscles to make movements. So, if we imagine every aspect of making music, our brain is practicing, and the result is nearly the same as if we had physically practiced. Imagine the implications this technique has for being able to practice if injured, if one has no access to an instrument, or if needing additional practice on something technically demanding without the possibility of causing injury from physically over-practicing.

4. Sleep may be one of the most important practice strategies of allWhat happens in the brain during sleep reinforces the idea that practicing occurs in the brain, not in the muscles. With the discovery in the 1950s of REM and NREM sleep, researchers realized that the brain is quite active during sleep, and they subsequently have found that several stages of the sleep cycle are vitally important for the encoding and consolidation of procedural memory (motor skill memory) as well as for encoding and consolidation of declarative memory (memory for a particular piece of music). Lack of sleep impairs both our initial learning of, as well as our memory for, a piece of music.

5. The visual is important in learning and making musicWe think of music as being strictly about sound, but the visual is involved as well. Amazing brain cells called mirror neurons fire not only when we make a motion ourselves but also when we see someone else making that motion or hear the sound resulting from that motion (such as the sound of a musical instrument). If we are trying to learn the violin, our brain “learns” by watching someone else play and develops a template for that motion and for the sound that motion creates, a template on which we can build as we practice. So, observation and listening are tremendously important in teaching or learning an instrument or voice. And surprisingly, these mirror neurons also have an impact on how we hear a live performance as a member of the audience. What we see affects what we hear.

Over the past few decades, we have added a great deal of information about the mind and body to our vocal and instrumental study. With the recent explosion of information about neuroscience and music, perhaps it’s time to incorporate some information about the brain as well into how we think about studying and making music.

Featured image by Damir Kopezhanov from Unsplash (public domain)

February 24, 2023

How to define 2022 in words? Our experts take a look… (part two)

How to define 2022 in words? Our experts take a look… (part two)

From partygate to Platty Joobs, we continue our look through 2022 in wordsIn the first blog post of our A Year in Words series, we looked at some of the words that dominated our conversations and rose in usage during the first quarter of 2022: from booster to Ukraine, via the less well-known monobob.

Now, our experts look at April to June and what the language we used can tell us about these eventful months.

AprilA defining moment in Boris Johnson’s premiership came with a linguistic twist: partygate.

Referring to a series of social gatherings held in 10 Downing Street and other government buildings during the national COVID-19 lockdowns, this political scandal ran through much of 2022.

The word partygate began to crop up in December 2021, with its usage increasing dramatically in January and February and then peaking in April, as the nation waited for the publication of civil servant Sue Gray’s report into the parties.

Although a very British scandal, the word partygate reflects the influence of the United States in the language of politics around the world. Partygate is one of a large and varied group of words taking the suffix -gate, which denotes an actual or alleged scandal and often an attempted cover-up. These scandals take their name from the 1972 Watergate scandal where people connected with President Nixon’s Republican administration were caught breaking into, and attempting to bug, the national headquarters of the Democratic Party (in the Watergate building in Washington, D.C.) during a presidential election campaign.

And this isn’t the first time a scandal involving controversial celebrations has been dubbed partygate.

The word goes back to at least the late 1990s, with a 1997 article in the South China Morning Post suggesting a senior politician had used public money to fund a private party and calling the affair “Partygate.”

From then on, the word has been used intermittently to refer to a variety of unconnected scandals, all flaring up then disappearing. Time will tell if 2022’s partygate will become the word’s definitive moment.

MayWhile the partygate headlines rolled on into May, this month was also marked by an outbreak of monkeypox, leading to the word being used nearly 300 times more than in May 2021, and almost 600 times more than in April 2022.

The Oxford English Dictionary’s (OED) earliest evidence of the word monkeypox—“a disease resembling smallpox which affects various species of rodent, monkey, and ape, originally in western and central Africa, and which is transmissible to humans”—is from 1960, two years after it was first identified among laboratory monkeys in Copenhagen, Denmark.

In May 2022, words such as virus, symptoms, outbreak, infection, and spread were among those found near monkeypox, with others such as skin-to-skin, contact, and vaccine increasing in visibility as the outbreak progressed and focus shifted to public health attempts to limit its spread.

Its usage continued to grow before reaching a peak in August 2022, when the World Health Organisation (WHO) invited submissions for an alternative name for the disease. They were seeking to mitigate a rise in racist and stigmatising language associated with the disease, as part of an ongoing effort to ensure that the names of diseases do not create or reinforce negative associations or stereotypes. Our lexicographer Danica Salazar has written more on major health crises and language with Richard Karl Deang from the University of Virginia.

In November, it was announced that the WHO would phase out monkeypox in favour of mpox and urged other agencies to do the same.

JuneOne of the biggest events of the summer was Queen Elizabeth II’s Platinum Jubilee—the first and only time a British monarch has reached the milestone of 70 years on the throne.

The Jubilee, celebrated over the first weekend of June 2022, was marked in the UK by a two-day bank holiday enabling four days of street parties, parades, concerts, and services of thanksgiving.

This event prompted the creation of a new term—Platty Joobs.

This term burst onto the scene on 20 April 2022 when the actor Kiell Smith-Bynoe, one of the stars of the BBC sitcom Ghosts, tweeted:

“I dunno about you man gassed for Lizzies Platty Joobs. I don’t even know what it is but i’m READY. Might make some trainers on Nike ID 🎯💯 🤞🏾”

A month later, towards the end of May, it began to appear as a hashtag on Twitter.

While anticipation for this unprecedented celebration undoubtedly drove the use of Platty Joobs, discussion of the phrase itself also helped its spread.

Twitter users were divided on whether they loved or hated the playful abbreviation. Even those opposed found it hard not to succumb to what proved to be a lexical earworm. On 25 May, journalist and author Caitlin Moran tweeted:

The mid-year mark“The Platinum Jubilee being called “The Platty Joobs” might be the worst thing to have ever happened in my lifetime. And yet … I’ve started whispering it to myself.”

We’re halfway through the year, and both politically and linguistically what a busy six months it was. Over our next two instalments we’ll cover the rest of 2022, with words relating to the extreme weather we experienced, the economic crises around the world and, of course, the passing of the UK’s longest-serving monarch, Queen Elizabeth II.

February 22, 2023

A shaky beginning of the end and the state of the art

A shaky beginning of the end and the state of the art

The previous two posts were devoted to the verbs begin and start. For consistency’s sake, it is now necessary to say something about the noun and the verb end. Two weeks ago, you saw a picture of Sophus Bugge, a great Norwegian literary historian and linguist. Etymology was not his main area, but he made many astute remarks about word origins. Some of them have been accepted with reservations, others rejected. As mentioned two weeks (a fortnight) ago, Bugge compared the root of begin with the Slavic root chin-,from kin-. Since his days, a spate of articles dealing with begin has been published, and as far as I can judge, the common opinion of Germanic researchers is that Bugge’s idea is wrong (in most sources, it is not even mentioned as worthy of consideration). Slavic chin– means “end,” not “begin,” and this is what makes the situation intriguing. While discussing begin, I mentioned the fact that in the linguistic intuition of many speakers, “beginning” and “end” are often hard to differentiate, because both refer to such concepts as “edge, margin, border.” The post even featured a ball of thread, with one “end” of the thread showing.

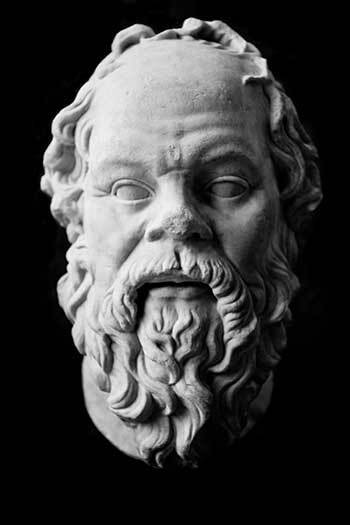

Socrates: a memorable forehead

Socrates: a memorable forehead(Louvre Museum, via Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

Curiously, the Slavic verb for “begin” (like Russian (na)chat’) practically never appears without a prefix, and likewise, the Germanic verb be-gin (Gothic had du–ginnan) is invariably tied to a prefix. We have no way of knowing why the bare root was avoided. Did the prefix denote direction? Or did it make the verb perfective, as up does in English finish up? (Think of the difference between eat and eat up, finish and finish up.) The Germanic verb for “begin” looks like a mirror image of the Slavic verb for “finish.” The phonetic match is also unobjectionable.

For many decades, a group of highly qualified specialists has been working in Moscow on a comparative etymological dictionary of the Slavic languages. The multivolume project has reached perz– (Vol. 41; the volumes are rather slim), so that by the middle of the century, unless the world collapses, the task will perhaps have been accomplished. The entry on the root for “finish” that interests us is short. As elsewhere, the root is compared in it with –cēns in Latin re–cēns “recent” (!), with Greek kainás “new” (!), and with Germanic –ginnan “to begin,” as though it were the most obvious thing in the world. That is why I mentioned the state of the art in the title of the post. Someone who will consult this excellent Slavic dictionary and then open an equally excellent modern Gothic (German, English, Dutch, Scandinavian) etymological dictionary will come away with incompatible answers. Beware of dogmatic verdicts!

Here are some of the senses of the Slavic words with the root –chen: “finish; thread; aim, target; edge; village street, beginning” (Vol. 11, pp. 5-6). Unfortunately, none of them can throw light on the mysterious origin of the Germanic verb end. Therefore, in a way, ours has been a disappointing journey. Apparently, once upon a time, the sound complex ken ~ gin (in and outside Germanic) meant “fringe, limit, border” and could refer to either end of an object. But why just this complex? We ask this question and realize that unless etymologists deal with sound imitation or sound symbolism, they cannot answer it. Something in the syllable ken must have been symbolic (this is true even if this complex was borrowed), but we cannot guess what.

Kronos, the god of time. It is hard to take him by the forelock

Kronos, the god of time. It is hard to take him by the forelock(Rubens, Museo del Prado via Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

English end is surrounded by a group of well-attested cognates: Gothic andeis, Dutch einde, German Ende, and so forth. Latin ante “before” (not “after”!) is also related. Among others, the most ancient Indo–European word that interests us must have meant “front” or “in front of,” because the same root regularly appears in the conjunction and (not a surprise!) as well as in Indo-European words for “forehead.” Such is Old Icelandic enni and Old Irish ēhtan (ē designates a long vowel), alongside Old Irish ēt “end, point.” Latin antiae “forelock” (remember the idiom take time by the forelock?), the much better-known ante “before” (up your ante, ladies and gentlemen!), and anterior belong here too. It would be more natural to expect that the story began with the word for “forehead” (a tangible object) and that only later, the concept of “fore-head” acquired the abstract sense known to us from the preposition. (Incidentally, in Slavic, some cognates of the word for “forehead” mean “the back of the head, occiput”!). But this is all like guesswork on coffee dregs or taking omens by the flight of birds. The ultimate origin of the word end, that is, the impulse behind its coining, remains unknown.

It may be of some interest to look at the familiar root hidden in a prefix. The noun answer, from Old English and–swaru, contains the prefix and– meaning “against” and the root of “swear,” from swar-. The verb denoted a solemn affirmation in response to a charge. Even the innocent-looking English along in go along, come along derives from Old English and-lang and corresponds to German entlang. The prefix in them means “opposite.” See what is said above about the history of the conjunction and. All this is interesting and instructive, but the sad truth remains: we failed to reconstruct the primordial impulse behind the coining of the words begin and end. In my end is my beginning.

By way of compensation, I may add a few lines on the story of the English word forehead. Like Old Icelandic enni, forehead is also an old word, and its inner form is the same. As time went on, the pronunciation of forehead changed. Do you remember: “There was a little girl, / Who had a little curl/ Right in the middle of her forehead. // When she was good, / She was very, very good. / But when she was bad, / She was horrid.” This poem is often called a nursery rhyme, perhaps suggesting anonymity, but it has become such: its author was Henry W. Longfellow, now cruelly and undeservedly neglected (practically forgotten, like almost everybody else). The rest of the poem is equally good. In the second element of a compound, h was lost in several other words, the best-known of which is shepherd. The true late pronunciation of shepherd can be seen in the family name Shepard. The now common pronunciation fore-head, like the variant often (with t in the middle) is a tribute to those words’ spelling, a pseudo-cultured “accurate” pronunciation. I hope no one yet says list-en or whist-le.

There was a little girl…

There was a little girl…(Bruno Miranda Photography, via Pexels, public domain)

The End

Featured image by Chaitanya Tvs, Unsplash (public domain)

February 21, 2023

Saving Earth’s Refrigerator: what does global warming mean for our planet’s future?

Saving Earth’s Refrigerator: what does global warming mean for our planet’s future?

Back in 1988, Jim Hansen of NASA told the United States Congress that the global warming of recent years was due to the burning of fossil fuels, which added so much dioxide (CO2) to the atmosphere that it exacerbated the greenhouse effect that kept the planet naturally warm. This new global warming was causing changes to climate and weather. It was greater in high latitudes than in low, and greater over land than over the ocean. With the benefit of hindsight, it’s clear that the continued increase in atmospheric CO2 from 350 ppm in 1988 to 412 ppm in 2022 is due to the fact that, since 1950, we have burned more than 90% of all the fossil fuel ever burned.

We have also learned that increases in other greenhouse gases emitted by human activities—like methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), and the chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs)—have added to the CO2-induced warming. Their effect is calculated by converting them to the equivalent amount of CO2, then adding that to the actual CO2 abundance to give the effective CO2. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), this is at about 500 ppm—a lot more than the 412 ppm due to CO2 alone. No wonder we are warming up.

Global temperature increase means melting snow and ice capsHansen was right. Although the global average temperature increase above the average for 1850-1900 is now almost 1.2ºC, it is close to 1ºC over the ocean, 2ºC over land, and about 3.6ºC over the Arctic. The Arctic is where much of the threat of global warming originates, because that’s where we have the most ice and snow in the Northern Hemisphere. We also find ice and snow in the Antarctic and in what scientists refer to as the “Third Pole,” the high mountains. In these three places, ice and snow are melting away as the world warms.

One key result is that sea level is rising. It rose about 20cm since the 1850-1900 baseline period but is happening at an increasing rate and is now 4 mm a year. Continued ice and snow melt may cause global sea level to reach between 1.5 m and 2 m by the end of the century, and 15 m by the year 2300. Although that estimate may seem extraordinary, geological data show that during periods of natural warming sea levels did rise by such amounts—for instance, 3 million years ago in Pliocene time, CO2 levels were in the range 450-500 ppm.

Melting snow and ice means losing Earth’s albedo“Since 1950, we have burned more than 90% of all the fossil fuel ever burned.”

My lecture audiences are not surprised that global warming melts ice and snow and makes sea levels rise. But they are surprised to learn that this same melt adds to the warming. This happens because ice and snow reflect solar energy. By doing so they keep our climate moderately cool. They are acting as Earth’s Refrigerator. As they melt away we are losing that reflectivity (Earth’s albedo). It’s as if we have gone away on vacation and accidentally left our fridge door open; everything inside begins to rot. Instead of that energy being reflected to outer space, it warms the ground and the ocean, which emit heat that is absorbed by the greenhouse gases. This creates a climate double whammy: warming caused by our CO2 emissions plus warming added by the loss of albedo. As mentioned earlier, CO2 is not acting alone. It is aided and abetted in particular by emissions of methane (CH4). In addition the warming created by these gases is exacerbated by water vapour, which evaporates from the warming ocean and is a powerful greenhouse gas in its own right.

Greenland is losing ice by melting at its surface. Antarctica is much colder, and very little of its ice is melting at the surface of its vast ice sheet. However, the Southern Ocean around the continent is warming, and its warm water is penetrating beneath the ice shelves that surround the continent, melting them from beneath. The net result is that both Greenland and Antarctica have lost about 5,000 billion tonnes of ice since 1980. Between 1993 and 2018, 8% of sea level rise came from Antarctic melt, 15% from Greenland, 21% from mountain glaciers, and 42% from the thermal expansion of heated seawater; the rest came from the pumping of groundwater for agriculture.

One of the most dramatic indicators of global warming is the loss of sea ice from the Arctic Ocean, which is likely to be ice-free in the summer by 2050. The volume of ice, as well as its area has diminished; since the late 1970s nearly all of the sea ice between 1 m and 6 m thick has disappeared. While this has not changed sea level, it did contribute to the shrinking of Earth’s Refrigerator.

Loss of ice means habitat erosion and extreme weatherOur planetary ice cover is extremely important. Mountain ice forms water towers for nearby populations. As it melts away, so does their water supply. Arctic snow and ice provide habitats for wildlife. As it melts away, those habitats shrink. As the Arctic warms, rain replaces snowfall and turns to ice at the surface, making it difficult for reindeer to feed. As the sea ice melts away from Arctic coasts, waves erode beaches and settlements. As Antarctic sea ice melts, penguin populations shift.

“Ice and snow reflect solar energy… They are acting as Earth’s Refrigerator.”

Away from icy regions, global warming dries vegetation and soils in already dry areas, making them more prone to wildfires. When the temperature over the ocean increases by just 1ºC, you get 7% more evaporation, which, when moist marine air hits land, means a lot more flooding in traditionally wet areas.

How can we save Earth’s Refrigerator?Evidently, anything we can do to eliminate global warming would help us to escape from these various dire side effects. Can we save Earth’s Refrigerator? Much mentioned is the concept of Net Zero, which means taking out from the air as much CO2 as we add to it. This is a tricky thing to do at the best of times. But in a very real sense it is an illusion, because it would mean maintaining in the air the current level of CO2, which would lead to continued warming, ice loss, and sea level rise.

What we really need are, firstly, fewer emissions, and, secondly, “negative emissions”—multiple means for extracting vastly more CO2 than we continue to supply. Without “negative emissions” we will hit an average global warming of well over 2ºC this century, which means well over 4ºC in the polar regions, hence vastly more ice and snow melt. To stop ice and snow melt we must also somehow increase the reflective effects of ice and snow. This could be done in the Arctic, for example, by pumping seawater into the air to stimulate the formation of reflective cloud cover. None of this will be cheap. But if we want our grandchildren and their descendants to experience the same equable climate through which our civilization developed, we have no choice but to work to save Earth’s Refrigerator.

Featured image by Michael Fenton, via Unsplash (public domain)

February 20, 2023

The social code: deciphering the genetic basis of hymenopteran social behavior

The social code: deciphering the genetic basis of hymenopteran social behavior

The authors of a recent study set out to uncover early genetic changes on the path to socialityBeginning with Darwin, biologists have long been fascinated by the evolution of sociality. In its most extreme form, eusocial species exhibit a division of labor in which certain individuals perform reproductive tasks such as egg laying, while others play non-reproductive roles such as foraging, nest building, and defense. This type of system requires individuals to forgo some or all of their own reproductive success to assist the reproduction of others in their group, a concept that at first glance seems incompatible with the key tenets of evolution (i.e. the drive of natural selection on individuals). While the honeybee is perhaps the most well-known example of a social species, the honeybee’s complex society represents just one end of a spectrum of social structures that can be observed among the Hymenoptera, which includes bees, wasps, and ants. At the other end are more rudimentary social structures involving, at the most basic level, cooperation of just a few individuals and their offspring.

While most research to date on insect sociality has focused on more complex social systems, understanding the evolution of these more rudimentary forms will likely help to reveal the earliest changes on the path to sociality. The authors of a new study published in Genome Biology and Evolution set out to fill this gap. According to first author Emeline Favreau, “Our work was unique in that we focused on six bee and wasp species that are not highly social, but have more rudimentary forms of cooperation, and are close relatives of highly social species.” By using machine learning algorithms to analyze gene expression across six species that represent multiple origins of sociality, the authors uncovered a shared genetic “toolkit” for sociality, which may form the basis for the evolution of more complex social structures.

The international team of researchers included Katherine S. Geist (co-first author) and Amy L. Toth from Iowa State University, Christopher D.R. Wyatt and Seirian Sumner from University College London, and Sandra M. Rehan from York University in Toronto. The authors worked together on this article “because we all find it important to understand the origins of sociality,” says Favreau. “We had been in the field observing the fantastic diversity of social lives, such as large nests of wasps busy with collective behavior or small carpenter bees organizing their broods in minute tree branches. We kept asking ourselves: But how did these behaviors come about? With this paper, we dove deep into the evolutionary stories to uncover molecular evidence of the emergence of social organization.”

“With this paper, we dove deep into the evolutionary stories to uncover molecular evidence of the emergence of social organization.”

The study involved a comparative meta-analysis of data from three bee species and three wasp species that represent four independent origins of sociality: the halictid bee Megalopta genalis, the xylocopine bees Ceratina australensis and C. calcarata, the stenogastrine wasp Liostenogaster flavolineata, and the polistine wasps Polistes canadensis and P. dominula. “Using data on global gene expression in the brains of different behavioral groups (reproducing and non-reproducing females), we found that there is a core set of common genes associated with these fundamental social divisions in both bees and wasps,” explains Favreau. “This is exciting because it suggests that there may be common molecular ‘themes’ associated with cooperation across species.”

A number of the functional groups found to be associated with sociality in this study have also been linked to sociality in other social bees and ants. These include genes related to chromatin binding, DNA binding, regulation of telomere length, and reproduction and metabolism. On the other hand, the study also identified many lineage-specific genes and functional groups associated with social phenotypes. According to the authors, these findings “reveal how taxon-specific molecular mechanisms complement a core toolkit of molecular processes in sculpting traits related to the evolution of eusociality.”

Interestingly, Favreau notes that “a machine learning approach to these large datasets was the best method for uncovering these similarities.” While the authors first attempted traditional methods for studying differential gene expression, these largely grouped species by phylogeny and failed to identify gene sets associated with sociality. In contrast, machine learning tools provided “a more nuanced and sensitive approach,” allowing the authors to identify gene expression similarities across a wide evolutionary distance.

The study involved three bees and three wasps representing four independent origins of sociality (circles; non-social sister species not shown) and a range of social and ecological phenotypes.

The study involved three bees and three wasps representing four independent origins of sociality (circles; non-social sister species not shown) and a range of social and ecological phenotypes. Images shown are (top) the bee species Ceratina calcarata (by Sandra Rehan) and (bottom) the wasp species Polistes dominula (by Seirian Sumner). Drawings by Katherine S. Geist.

One remaining question is how the findings of this study, which focused on species with rudimentary forms of sociality, might compare to an obligately eusocial species with morphologically distinct castes of reproductive and non-reproductive individuals. According to Favreau, “This is something we are currently working on and hope to be able to address in the near future. We are taking a broader approach to examine how genes and genomes change during the course of social evolution.” This includes adding transcriptomic data for 16 additional bee and wasp species, enabling “a larger comparative study with species of wasps and bees that are solitary, have rudimentary sociality, and have complex sociality.”

Expansion of the study however requires obtaining samples from around the globe, a feat that has at times proved difficult. “It was actually a challenge to find many of these species, some of which had never been studied before on a genetic level!” notes Favreau. “Given the global diversity of taxa and the remote locations many were collected in, we are happy to have been able to obtain all specimens and genomes given the global pandemic and travel restrictions the past few years.” The team was ultimately able to acquire a number of samples through partnerships with other investigators and institutions, emphasizing the critical role of collaboration in scientific discovery.

Featured image by Sandra Rehan (CC-BY: https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evac182)

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers