Oxford University Press's Blog, page 39

November 7, 2023

How the US healthcare system is failing people with eating disorders [infographic]

How the US healthcare system is failing people with eating disorders [infographic]

People with eating disorders often do not receive sufficient support within the United States healthcare system, which can have a devastating emotional and monetary impact on patients and their families. Issues that need to be addressed include a lack of awareness of serious mental illness, insufficient research funding, healthcare coverage, and rigorous treatment that would lead to earlier identification.

This infographic illustrates some of the statistics and case studies included in Pamela K. Keel’s article on eating disorder treatment in the US healthcare system.

Keel is a Distinguished Research Professor and Director of the Eating Behaviors Research Clinic in the Psychology Department at Florida State University, and an advocate for greater awareness and treatment for people with eating disorders.

Read her full analysis in this blog post: How the healthcare system is failing people with eating disorders.

November 6, 2023

D.B. Cooper, Martin McNally, and the Golden Age of Skyjacking

D.B. Cooper, Martin McNally, and the Golden Age of Skyjacking

In June 1972, Martin McNally pulled off one of the most daring airline hijackings in American history, parachuting from the aft stairs of a Boeing 727 with half a million dollars in cash. He jumped at night at 320 miles an hour, using only a small reserve parachute. He had never parachuted before. It took the FBI nearly a week to track him down.

McNally’s heist came at the end of a wave of US hijackings that shook commercial aviation. Before the introduction of large commercial jets, hijackings were virtually unknown in the US. From 1961 to 1967 there were only nine hijackings of US commercial flights.

All of that changed in 1968. That year there were 17 hijackings and another 40 in 1969. All but four of the hijackers wanted to go to Cuba. Many were homesick Cubans who had migrated to the US after the Cuban revolution and became disillusioned with life in America. The take-me-to-Cuba hijackings had a certain innocence about them. None of the passengers were harmed and the Cuban government treated them like tourists.

In December 1968, Time magazine advised hijacked passengers to “relax… most Cubans are indeed friendly and will make your layover as comfortable as possible.” At the Havana Libre (formerly the Havana Hilton), “the rooms are still comfortable, the service is still good, and Havana still swings,” ran the article in Time. Some travelers deliberately booked flights through Miami in the hopes of being hijacked. “Is this the plane to Cuba?” Miami-bound passengers asked stewardesses with a smile.

The hijackers were not so lucky. Many, including about a dozen Black Panthers or members of other Black Power groups, languished in Cuban prisons under brutal conditions. They had expected a hero’s welcome, but were instead treated like spies, criminals, and terrorists. As word filtered back about the fate of hijackers in Cuba, the number of planes commandeered to the island declined.

But the hijackings continued, facilitated by lax airline security. Carryon luggage was almost never screened, and no identification was required to buy a ticket. Airlines considered installing metal detectors, but worried that they would annoy passengers. As a result, hijackers carried machine guns, rifles, shotguns, pistols, knives, hand grenades, dynamite, and all manner of bombs, mostly fake, on board commercial flights.

A common thread running through these hijackings was the cool professionalism with which stewardesses, as they were called at the time, managed the hijackings. They were the ones who negotiated with the hijackers, often at gunpoint, easing tensions and protecting passengers.

In June 1970, Arthur Barkley used a gallon of gasoline to hijack a TWA flight from Phoenix. Barkley did not want to go to Cuba. Instead, he demanded $100 million in cash, ostensibly to settle a grudge over a bill for $471.78 on his 1964 tax return. Barkley was apprehended when the plane landed at Dulles Airport near Washington, D.C., but his caper added something new to the mix: hijacking as a means of extortion.

Getting the money was not the problem, it was getting away with it. Then, in November 1971, D.B. Cooper figured it out. No one knows who he was or where he came from. At the Northwest Orient ticket counter in Portland, Oregon, he used the name “Dan Cooper,” paying 20 dollars cash for a one-way ticket to Seattle. While they were taxiing for takeoff, he asked for a Bourbon and 7-Up and handed stewardess Florence Schaffner a note. “MISS—I have a bomb here and I would like you to sit by me.”

She asked if he was kidding.

“No, miss, this is for real,” Cooper calmly replied.

Cooper opened his briefcase, showing Schaffner what looked like a bomb, and demanded $200,000 and two sets of parachutes. He knew that the aft stairs of a Boeing 727 could be opened in flight. As the plane flew south from Seattle, he parachuted into the night, a bag containing the money in twenty dollar bills tied around his waist. A news story reported his alias as “D.B. Cooper” and the name stuck. Despite a massive search, no one connected with the investigation ever saw him again.

Worse yet, from the FBI’s perspective, Cooper became a countercultural hero. He had beaten the system and done it in style, sipping his bourbon and smoking a cigarette, joking with the stewardesses while wearing wraparound sunglasses. “He seemed rather nice,” stewardess Tina Mucklow later said. “You have to admit he was clever,” said a Seattle taxi driver. “He didn’t hurt anybody,” another local said. “Most of the people around here kind of hope he makes it.”

“McNally’s heist came at the end of a wave of US hijackings that shook commercial aviation.”

Five parachute hijackers followed Cooper in the first half of 1972. Richard LaPoint, a troubled Vietnam veteran, hijacked a flight from Las Vegas, jumping near Denver with $50,000. Frederick Hahneman commandeered an Eastern Airlines 727 en route to Miami, eventually jumping into the night over Honduras with $303,000. Robb Heady hijacked a 727 in Reno by running across the apron with a pillowcase over his head and a .357 Magnum revolver in his hand. Richard McCoy jumped near Provo, Utah, after obtaining a $500,000 ransom in San Francisco. All four of these hijackers survived their jumps with, at most, only minor injuries, and all were soon caught.

Martin McNally’s hijacking of American Flight 119 in June 1972 was the last of the US parachute hijackings and it almost worked.

McNally commandeered a St. Louis-to-Tulsa flight using a sawed-off machine gun he concealed in a briefcase. Back in St. Louis, he demanded $502,500 in cash and four parachutes. How he bailed out over central Indiana and eluded capture for almost a week is perhaps the most remarkable part of the story—but you will have to read the book for that.

The parachute hijackers fit the cultural moment. Their exploits seemed more thrilling than sinister and less surprising than they would be today. When things turned violent in the second half of 1972, everyone agreed that something had to be done. That something was better security, beginning with metal detectors. There were 134 US hijackings between 1968 and 1972, but only one unsuccessful attempt in 1973. Airline security would not become a pressing issue again until 9/11.

Featured image by Leio McLaren on Unsplash (public domain)

More than emotion words

Interjections like oh or wow are sometimes described—too simply—as “emotion words.” They certainly can express a wide range of emotions, including delight (ah), discovery (aha), boredom (blah), disgust (blech), frustration (argh), derision of another (duh) or one’s self (Homer Simpson’s d’oh).

Some grammars refer to interjections with the term “exclamations” and older grammars may even use the term “ejaculations,” which evokes laughter from sophomores in the classroom. But whatever one calls them, they are an underappreciated and somewhat misunderstood part of speech.

Part of the problem is that not all interjections express emotion. Some aim to frighten: take boo, for example (to which the response might be eek). Some interjections indicate mock sympathy or amusement: boo-hoo or ha-ha. Shh is a command, not an expression of emotion. Whoa (not the misspelling Woah) calls a halt to something. And uh-huh indicates attention or agreement, but again not emotion. Interjections like ick and meh indicate that something is disappointing. And of course, other words besides interjections can express emotion—the verbs love and hate, for example, or various expletives.

Interjections can be ambiguous: Hm can indicate curiosity, confusion, concern, or skepticism. Among other things, oh can indicate comprehension or acknowledgment (Oh, I see), approximation (“Oh, about ten minutes”), pain or pleasure. And oh should not be confused with the prayerful O! or oh-oh used as an indication of something bad. Ouch (or ow) signals pain but can also be a comment on a harsh or unfortunate situation (“Ouch, look at all these red marks on my paper.”)

It’s not uncommon for words that function as another part of speech to be pressed into use as interjections, like well or yes, as in “Well! That’s rude,” or an ecstatic “Yes! I got the job.” In other situations, such as “Well, I don’t think that is such a good idea” or “Yes, you are right,” well and yes are not expressing emotion and should be considered adverbs indicating a speaker’s attitude.

It probably makes the most sense to talk about interjections as words used to manage communication by indicating reactions (uh-huh, oh, I see), attitudes (hm, well, boo-hoo), emotions (wow, eek, ugh), or parenthetical asides (I mean, you know). Linguists often refer to such words and phrases as “pragmatic markers,” and thinking about interjections in this way rather than as “emotion words” will sharpen our understanding of grammar.

You may not be ready to replace the term “interjections” with “pragmatic markers.” But remember, there’s nothing sacred about the traditional parts of speech.

Can I get an “uh huh?”

Featured image by Karolina Badzmierowska via Unsplash (public domain)

November 5, 2023

Supporting a loved one who self-injures [infographic]

Supporting a loved one who self-injures [infographic]

The stigmatization of self-injury remains common. Such stigma makes it difficult for people to reach out about their experience, even when they may want support. Further, many people who do not have lived experience, but who are concerned about someone who does, want to offer support but are unsure about how to navigate this. The application of a person-centered approach when discussing self-injury can be used to foster more appropriate discussions, which will leave individuals with lived experience feeling more understood and validated.

Starting a supportive dialogue with a loved one who self-injures can make a big difference in their journey to recovery. For tips on starting this conversation, read our infographic adapted from Understanding Self-Injury by Stephen P. Lewis and Penelope A. Hasking.

November 3, 2023

How to recognise and treat an episode of psychosis [infographic]

How to recognise and treat an episode of psychosis [infographic]

Psychosis is a rare experience and often misunderstood within society. It often first occurs in late adolescence or early adulthood—an exciting but often tumultuous time of role transitions and challenging new opportunities such as college and employment. An episode of psychosis can be frightening for those undergoing it, and for their loved ones, and navigating through evaluation, treatment, and recovery can be a stressful and isolating experience. It’s important to spread awareness that with the right support, those experiencing psychosis can take an active, informed role in their care and journey to recovery.

Learn more about the symptoms, stages, and treatments for psychosis in the infographic adapted from The First Episode of Psychosis, which supports young people and their families experiencing the initial episode of psychosis.

How little we (can) know about the history of the English language

How little we (can) know about the history of the English language

As a historical linguist, I devote much of my teaching, research, and even recreational time to trying to understand what English is today and how it got here. Some things are easily noticed: that Beowulf uses words (“æþelingas”), morphemes (“monegum”), and graphs (þ, æ, ð) that English no longer has. Or that later English, because of its orthography and word order, often looks more remote than it really is. “Whan that Aprill with his shoures soote,” the opening of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, is not much more than “When April, with its sweet showers.”

In examples like these, it’s easy to distinguish what English was from what it is. But many cases are less clear, and one of the reasons for this is that, as perhaps with all historical inquiry, the farther back in time one goes, the less substantive the evidence becomes. By which I mean the fewer the attested examples of written or spoken English. Some evidence hangs by a thread. The 3182 lines of just one poem (Beowulf), for example, constitute about 10% of the entire corpus of Old English poetry. If one were to graph the number of surviving examples of English against each successive year, that graph would show a steady increase in extant material from the date of the Beowulf manuscript (around 1000) until about the year 1600; a significant rise at that point due to increases in literacy and printed documents and an expansion of the kinds of works (such as personal letters) that begin to survive in abundance; and a precipitous rise after 1900, due to new media and the spread of English as a global language. For the first part of this graph the line might incline at about 20 degrees, for the second part at about 45 degrees, and for the last part, when messages, texts. and digital files of all kinds offer accessible data in the cloud, at perhaps 60 degrees.

“Any language history is not a history of what happened linguistically but a history of what survived.”

Historical English data are skewed by more than survival rates, however. The kinds of English that survive also vary significantly from one era to another. Prior to 1400 the data set of English (as my Beowulf example suggests) is comparatively small; before 1700 much of it is rhetorically crafted in some way, whether by legal figures, theologians, administrators, novelists, or poets; before 1800 it is mostly composed by males; and before 1900 it is virtually all written and offers little evidence of the actual language of entire groups, such as children or second language learners.

Preservation of unambiguously spoken English, then, is very much a recent phenomenon. The earliest extant English oral data occur in Thomas Edison’s 1877 recording of “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” and after that recordings are sporadic for at least a half century, with many of the earliest being stylized exercises in political oration or poetry reading and all of these (with the possible exception of a disputed recording of Queen Victoria) being by males. The primary reason for any widening of the linguistic record is of course technology, and because of this a true proliferation of genuine oral data is even more recent. The preservation of casual speech, as ubiquitous and inexpensive as it may be today, is very much a recent phenomenon.

“In the history of English, historiography is as important as grammar, usage, and speakers.”

To make up for gaps in the record, historical linguists, like all historians, rely on reconstructions based on what they know of the language’s larger history or on documented processes of change for other languages. While methods of reconstruction have been refined for hundreds of years, they remain fundamentally tied to a very partial historical record: one without speech or children for most of its history, without women for much of it, without ephemeral examples for nearly all of it, without much documentation of the early contact varieties that developed globally in the age of exploration, and so forth. Ultimately, any language history is not a history of what happened linguistically but a history of what survived, or what linguists believe themselves able to reconstruct. And an account like this cannot explain the whole of the language because so much of the language’s history does not survive.

Which shows that in the history of English, historiography is as important as grammar, usage, and speakers. It is historiographic frames that put these pieces together into a cohesive narrative that then can be used to explain still other linguistic pieces. Significantly, whether through heuristics like genealogy, social criticism, usage, or language families, different historiographies will identify and categorize the same data in different ways, each of which sustain its own objectives. This means, in essence, that writing the history of English (or any language) is not so much a matter of connecting the pre-arranged dots of some paint-by-numbers picture as it is in laying out those dots and assigning an order to them.

November 2, 2023

Understanding Depersonalization and Derealization Disorder [infographic]

Understanding Depersonalization and Derealization Disorder [infographic]

What if our perceptions of our own thoughts, or the world around us, changed in an inexplicable way? What if the world suddenly seems strange and unfamiliar? This is the story of millions of people worldwide who experience depersonalization/derealization disorder (DDD). This condition causes a serious disruption in a person’s experience of the self that alters their entire world.

Depersonalization is the third most common psychiatric symptom, yet clinicians and lay people still know little about its presentation and treatment. While it can indeed be a symptom accompanying other mental illnesses, it is also a full-blown disorder itself, recognized by every major diagnostic manual.

Learn more about the symptoms of DDD in the infographic adapted from the second edition of Feeling Unreal by Daphne Simeon and Jeffrey Abugel.

November 1, 2023

Breakthrough and disgrace: Knut Hamsun’s Hunger and Pan in retrospect

Breakthrough and disgrace: Knut Hamsun’s Hunger and Pan in retrospect

The 2023 award of the Nobel Prize for literature to the Norwegian writer Jon Fosse brings Norwegian literature into focus for English-speaking readers and provides a fresh angle from which to view the writings of Knut Hamsun. Born in 1859, almost exactly a hundred years before Fosse, Hamsun was awarded the same prize in his early sixties, which is also Fosse’s current age. Hamsun’s earlier writings stand at the threshold of European modernism, of which he is an acknowledged forerunner. Fosse’s work may now appear to us as more radically experimental, but its repudiation of traditional narrative and its focus on inner worlds and responses rather than life-like “characters” and their plots belong recognisably to the lineage that Hamsun explicitly set out to inaugurate with two of his works Hunger (1890) and Pan (1891).

However, Hamsun’s political opinions and his subsequent trajectory on the world stage took him to a place very different from Fosse’s. In 2011, in recognition of his contribution to arts and culture, Fosse was granted honorary residence in The Grotto (Grotten), a small house in the grounds of the Royal Palace in Oslo, first inhabited by the nation’s great Romantic poet, Henrik Wergeland (1808–45). Hamsun, by contrast, applauded the rise of the National Socialists in Germany in the 1930s, admired Hitler, and became a leading publicist of the Nazi occupation government. After the war, he was submitted to a lengthy legal and psychiatric enquiry (1945–47), heavily fined, and even received an official medical diagnosis (he was said to suffer from “chronically diminished mental capacities”). He had sacrificed the reputation he had spent a long life building and lived out his last years in disgrace.

Another Norwegian winner of the prize, in 1928, was Sigrid Undset, a novelist whose vast historical canvases and powerful, complex women characters attracted readers worldwide. She became Hamsun’s fierce political opponent during the 1930s, and in April 1940 was the first Norwegian writer to go into exile following Germany’s invasion and occupation of Norway, returning only after the end of the Second World War.

“To what extent should readers let Hamsun’s later public deeds and beliefs affect their reading of his earlier works?”

These different life-choices cast a spotlight on Hamsun’s political affiliations and activities which cannot be erased by means of mitigating arguments. The question they leave open is to what extent readers of today should let Hamsun’s later public deeds and beliefs affect their reading and interpretation of his earlier works.

Hamsun’s Nobel prize was awarded, essentially, for his 1917 novel Growth of the Soil, the story of a pioneering Norwegian farmer who labours to cultivate the land in a remote Norwegian province. This novel cemented Hamsun’s already considerable reputation and was praised for its “idealistic” qualities. The Nobel committee was critical of the experimental qualities of Hamsun’s works of the 1890s, but there is no sign that they reacted against his political ideas. Yet Growth of the Soil was widely read in Germany and was to become a favourite of the National Socialist regime, for which it was held to exemplify the virtues of a Germanic love of the soil. It thus played a central role in making Hamsun a favourite for Goebbels and others in the Nazi leadership when they looked for major cultural figures who could promote their values. Hamsun became, in short, a new Goethe from the north.

This soon led to ideological challenges at home. How was one to read Hamsun? The apologetic Hamsun tradition was started already in 1936 by the communist playwright, later celebrated resistance poet, Nordahl Grieg. He wanted to save a writer whom he loved and insisted that Hamsun was a political idiot but a poetic genius. Life and work ought to be thought of as separate.

What is most remarkable about Hunger and Pan, the early Hamsun works that now appear in new English translations, is that, in their quite different ways, both are accessible, deeply moving, hilarious (Hunger in particular), and rich in strange ways of looking at the world and its inhabitants, while at the same time constantly challenging conventional modes of storytelling. Both also illustrate (again in contrasted ways) what Hamsun meant by “a poetry of the nerves,” his phrase for the mode of inner dissonance that governs his fictional imagination. This is what one reads these works for, and it is also these qualities that give him a unique place in the rise of European modernism. It is what made them seem so fresh and sensational when they first appeared. Hamsun’s fiction, like that of so many of his twentieth–century successors, calls out post-romantic, nostalgic, and emotionally complacent modes of storytelling. These are not doctrinaire novels, but explorative works of fiction, even when they no doubt query certain aspects of the modernity to which they belong; one has to look to Hamsun’s essays and letters for more outright expressions of socio-political opinion.

How one reads Hunger and Pan will thus depend critically on the reader’s choice of perspective. You can regard them as poetic experiments, as uniquely brilliant instances of the early modernist imagination, or, more sombrely, as embryonic symptoms of the twentieth-century European catastrophe. Hamsun’s life and works are suspended between these two polarities.

Featured Image by Kjetil r via Wikimedia Common (CC 2.0)

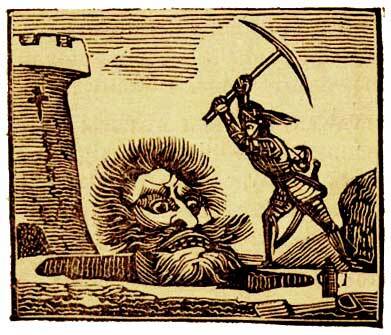

A fool’s cap of etymologies, or the praise of folly

A fool’s cap of etymologies, or the praise of folly

It is Halloween season and I thought I might offer our readers some mildly entertaining topic, appropriate for the occasion, but ghosts, ghouls, and gourds have been explored with such fullness by other people that I decided to talk about fools, though 1 April is a long way off.

It is amazing how many synonyms for “fool” exist! Here is the shortest list of English non-compound nouns meaning “fool”: booby, dunce, dolt, ninny, and noddy ~ noddle. Compounds often end in –head, such as blockhead, lunkhead (from lumphead?), and dunderhead (from thunderhead?), but of course, we also remember numskull (a rather confusing spelling for numbskull). It is almost funny that fool, the main English word for “a stupid person,” is not native. Fool was borrowed from Old French and, like folly, ultimately goes back to Latin follis “an inflated ball.” Obviously, a windbag is not a paragon of wit.

Stupid is also a Romance word. In English texts, it surfaced in the fourteenth century and meant “pitiful.” By way of compensation, silly is Germanic, but how sad its history is! German selig, a close cognate of silly, means “blessed.” In the fourth-century Gothic Bible, the adjective sels meant “happy.” Later, the English adjective developed into “simple, ignorant,” and “feeble-minded.” What a striking case of the deterioration of meaning! The Old English for “fool” was (ge)dwǣsmann. –mann is of course “man,” and dwǣs is related to the root found in the Romance word for “beast.” That root meant “to breathe”: from an etymological point of view, the ancient noun beast meant “a breathing creature.” But those distant origins were forgotten long ago, and, as a rule, language treats animals with beastly contempt.

A smart bird called noddy.

A smart bird called noddy.Via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 2.0 DEED)

Our intelligence is so much superior to that of dumb beasts, isn’t it? We have even invented artificial intelligence, the dreaded AI. Ass, for instance, has become another word for “idiot.” Stubborn asses (donkeys) have forever carried burdens for us, and this is their reward. A particularly flagrant case of animal abuse comes from Scandinavia. The main fish that has sustained northerners for centuries is the cod: Icelandic þorsk(u)r, Norwegian torsk. The name of this invaluable fish has come to mean “fool.” A rare but insufficient case of restitution is an exclusive club the Norske Torske Klubben in St. Paul, Minnesota, founded by clever and dedicated people. Alas, a very big cod is called auli in Icelandic. This word also means “idiot”! By way of comfort, let us look at how we treat one another. Ninny is mine Inny(= Innocent), as nanny is mine Annie. And nincompoop consists of the first part of Nicholas (or more probably, Nicodemus), with -n-, perhaps “borrowed” from ninny, and poop added for the ultimate insult.

Other than that, we (or some of us) are fine. Everybody else is dumb. Once upon a time, formidable giants lived everywhere. In myths, the Scandinavian gods fought them. Nowadays, smart boys and girls overpower them in folk tales, and giants have long since gained an unenviable reputation for stupidity. Old English had the word fīfel “monster, giant.” Its Modern Icelandic cognate means only “fool.” Yet my favorite Icelandic word for “giant” is glóp(u)r, because it sounds almost exactly like the Russian adjective glup- “stupid.” Some researchers believe that the two words are connected (a Slavic borrowing from Germanic?). Others deny the connection. My exposition sounds like a tale told by an idiot (minus the fury), but no, this is etymology: in reconstruction, few things are certain.

In our languages, birds do not fare much better than four-legged creatures and giants. One, almost arbitrary, example is noddy, the name of a nice, innocuous bird. Did the image of constant nodding ruin the bird’s reputation? The verb nod, first recorded in Middle English, seems to have related forms in German, and there, much to our irritation, its traces are lost. But then noodle also means “fool”! The origin of this word, the distant relative of noodle, designating a food product, has never been discovered. Does the image of noodles (strips and rings) make this food look ridiculous? The Russian idiom (in translation) don’t hang noodles on my ears means “stop duping me with your nonsense.” I have no idea where it originated or whether it is native or borrowed. The Russian word for “noodles” (lapsha, stress on the second syllable) is old; at some time, it acquired the not unexpected sense “confusion.” English use your noodle “think about it” (once, much more offensive than today) seems to be rather close to the Russian phrase. Can they be connected? Or is the n-d group sound symbolic, suggesting actions of a fool?

Here is our wide-awake and intrepid youngster Jack the giant-killer.

Here is our wide-awake and intrepid youngster Jack the giant-killer.Via Wikimedia Commons (public domain)

Even though there is no way to discover the answer, we’ll presently return to this matter. Here I’ll only note the playful element in dealing with words for stupidity. Among several Icelandic words for “fool” (as though we have not yet seen enough of them!), we find bjáni, gjáni, and kjáni. Each has its own uncertain etymology, but it would be a minor miracle if they did not interact in some way. What a chance to denigrate an opponent and call him teasingly bjáni-gjáni-kjáni “cowardly, cowardly custard”! Words for “fool” must often have originated in slang. That is why their origin is usually hard to trace. We note with surprise that, for example, the etymology of German Narr “fool” is debatable, almost unknown. Perhaps a borrowing, but this idea is shaky.

Now back to sound symbolism. English dolt seems to be in some way connected with dull. But is it? The great Romance scholar Hugo Schuchardt followed his predecessors and cited similar forms from Basque, Portuguese (doudo, now doido “crazy”) and German (Dudeltopf “simpleton, noodle”), along with Latin stultus “stupid” (think of English stultify and disregard the s-mobile before t) and the possibly related stolildus “stolid.” Though cautiously, he suggested that the group dl-d occurs in words for silliness and has an emotional value. He was probably right. Once again, I may cite Russian examples. Dylda (stress on the first syllable) means “a lanky youth”; the word is humorous. The verb doldonit’ (stress on the second syllable) means “to prattle.” No Russian etymological dictionary features it. It may well be that dolt, along with its earlier doublet dold, is a word like dylda and that only folk etymology connected it with dull. As noted above, though proof in this area does not exist, there is no harm in suggesting a rational idea.

A fool from Twelfth Night, the cleverest character of them all.

A fool from Twelfth Night, the cleverest character of them all.Via Wikimedia Commons (public domain)

Finally, English geek for desert. The present-day senses “a socially eccentric person” and “someone engrossed in a single subject” are recent. For a long time, only geek “a performer whose act consists of biting the head off a live chicken or a snake” was known. A geek was a freak, a fake, an attraction in a pit-show. The word’s source must have been German Geck “fool” (Scottish geck “to deride” comes from the same source). The origin of German Geck is murky and need not trouble us in this context. Perhaps the word was sound-imitative or sound-symbolic. Or perhaps geeks gawked too much.

Fools are all over the place, but let us not despair and remember that the smartest person in Shakespeare’ plays is the fool. Happy Halloween! Go trick-or-treating. Someone who always stays at home (Icelandic heimski) is a fool. And look up the origin of idiot! Out, out, into the world of fresh air!

Featured image by Robert Linder on Unsplash (public domain)

October 31, 2023

Infrastructure, public policy, and the Anthropocene [podcast]

Infrastructure, public policy, and the Anthropocene [podcast]

On today’s episode of The Oxford Comment, we discuss the state of human infrastructure in the Anthropocene with a particular focus on how research can best be used to inform public policy.

First, we welcomed Patrick Harris, co-editor-in-chief of the new transdisciplinary journal, Oxford Open Infrastructure and Health, to speak about the aims and scopes of OOIH, how OOIH is poised to meet the challenges of the Anthropocene, and the kind of research the editors are seeking. We then interviewed Jonathan Pickering, co-author of The Politics of the Anthropocene, the winner of the 2019 Clay Morgan Award Committee for Best Book in Environmental Political Theory. We spoke with him about how the shift from the Holocene to the Anthropocene has affected our core infrastructure systems and how good governance can help us mitigate the many challenges we’ll face in the future.

Check out Episode 88 of The Oxford Comment and subscribe to The Oxford Comment podcast through your favourite podcast app to listen to the latest insights from our expert authors.

Oxford Academic (OUP) · Infrastructure, Public Policy, and the Anthropocene – Episode 88 – The Oxford CommentRecommended readingUpon the initial launch of Oxford Open Infrastructure and Health, co-editors Evelyne de Leeuw and Patrick Harris penned this blog post on the OUPblog, introducing the journal and detailing how OOIH will provide a link between infrastructure and both (inter)planetary and human health.

OOIH’s opening editorial, also written by the co-editors, elaborates on their vision for OOIH, provided greater context for the intersection between infrastructure and well-being, and presented the foundations of what future research published by the journal will need to include.

Human activities have a decisive causal influence on the Earth system, but to date the responses of the social sciences to the challenge have been inadequate. It is necessary to do better. Delve into the scholarship of our guest, Jonathan Pickering, and his co-author John S. Dryzek as they unravel the good, the bad, and the inescapable of our new epoch in this chapter from their book, The Politics of the Anthropocene.

The Anthropocene will not recede, and the central question of environmental management will be whether we can develop ways to reflexively and sustainably manage ecosystems, habitats, and human needs. This chapter examines four possible normative underpinnings for such management, from The Oxford Handbook of Environmental Political Theory.

The Anthropocene has emerged as a powerful new narrative of the relationship between humans and nature. Anthropocene: A Very Short Introduction draws on the work of geologists, geographers, environmental scientists, archaeologists, and humanities scholars to explain the science and wider implications of the Anthropocene. This chapter explores why we should accept that a new chapter of Earth history might indeed be unfolding, with humans playing a leading role.

This response to the editors’ essay by Phil McManus offered a clarification on what is termed infrastructure, and examined the history of urbanist programs as a means to inform today’s relationship between health and infrastructure as their intersection is more clearly defined.

The Anthropocene is not only a geological event but also a political, philosophical, and theological one. This chapter, from Call Your “Mutha’”: A Deliberately Dirty-Minded Manifesto for the Earth Mother in the Anthropocene, proposes that key to its undoing is decolonization, including of lands, waters, minds, and spirit, by drawing upon unjustly discredited knowledges, including Indigenous ontological conceptions of spiritual meanings that recognize the awareness and being of all terrestrial life, the inherent value of matter and the agency of Nature-Earth.

Explore the following Open Access articles from our journals:

“The Paradox of Anthropocene Inaction: Knowledge Production, Mobilization, and the Securitization of Social Relations” by Madeleine Fagan in International Political Sociology (February 2023)“Ecosystems and Ordering: Exploring the Extent and Diversity of Ecosystem Governance” by Cristiana Maglia and Elana Wilson Rowe in Global Studies Quarterly (June 2023)Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers