Oxford University Press's Blog, page 35

January 31, 2024

Holes in the Tower of Babel

The Tower of Babel story (Genesis 11:1–9) is among the most famous in the Bible. It might even be considered an iconic text—famous beyond its actual content; since the story was originally written it has come to mean much more than its actual words. Although many Westerners have a vague idea of what the story is about, or at least know the name “Babel,” it is best to (re)read the text in full. Here it is in the New Revised Standard Version:

1Now the whole earth had one language and the same words. 2And as they migrated from the east, they came upon a plain in the land of Shinar and settled there. 3And they said to one another, “Come, let us make bricks, and burn them thoroughly.” And they had brick for stone, and bitumen for mortar. 4Then they said, “Come, let us build ourselves a city, and a tower with its top in the heavens, and let us make a name for ourselves; otherwise we shall be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth.” 5The LORD came down to see the city and the tower, which mortals had built. 6And the LORD said, “Look, they are one people, and they have all one language; and this is only the beginning of what they will do; nothing that they propose to do will now be impossible for them. 7Come, let us go down, and confuse their language there, so that they will not understand one another’s speech.” 8So the LORD scattered them abroad from there over the face of all the earth, and they left off building the city. 9Therefore it was called Babel, because there the LORD confused the language of all the earth; and from there the LORD scattered them abroad over the face of all the earth.

That the story is tightly constructed and a well-designed unit is apparent even in English translation. Note, for instance, how the humans say “Come, let us. . . .” (vv. 3, 4) and this is balanced by a divine “Come, let us. . . .” (v. 7). This balance is actually an imbalance because the humans twice make this statement whereas the deity says it only once—an indication, perhaps, that the deity’s singular comment is decisive, trumping the repeated and collective efforts of the humans. That impression is underscored because what the humans fear most—being “scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth” (v. 4)—is exactly what God accomplishes in the story, again decisively, and this time twice told (vv. 8-9). We can find irony elsewhere in the story as well: the humans design to make a tower “with its top in the heavens” (v. 4), but it is said that the Lord had to “come down” to even see this massive city and the tower (v. 5). Finally, there is an important instance of word play in the story. The name of the city, “Babel” (Heb bābel), is a play on the verb used for the confusion or confounding (Heb bālal) of the languages that happens there. Also, the name of the city, “Babel,” is the same term used of “Babylon” elsewhere in the Bible, suggesting that the story functions not only as a narrative explanation or etiology for the confusion of languages, but also for the etymology of “Babylon” and thus the Babylonian empire that would wreak such havoc on Israel in the early sixth century B.C.E.

“The tower of Babel story is replete with gaps—notable lacks in important information.”

Despite these literary features and the high level of literary artistry in the story, much is left unsaid. In this regard, it resembles other biblical narratives, which are often rather spare in narrative detail. The tower of Babel story is replete with gaps—notable lacks in important information. It does not indicate—at least not clearly—what is wrong with this city and tower that God should be bothered by it in the first place. The height evidently was not an issue because, again, God had to come down to see it. Yet despite that detail, God immediately states that this building project is the beginning of something apparently threatening (v. 6). Something is clearly wrong with the tower—or rather the city (v. 8)—but we do not know what that is exactly.

All literature contains gaps like these (lawyers, after all, are often hired to find loopholes in supposedly airtight legal discourse), but careful readers can identify them and determine where and when such gaps can be filled and how to do so. Indeed, the history of biblical interpretation could almost be described as a history of gap-filling, and the tower of Babel story is no exception. So, while the text of Gen 11:1–9 does not clearly indicate what the problem is, that has not prevented subsequent readers and interpreters from doing so. Such tendencies are present in modern interpretations, and are evident already in very early texts. For instance, as James L. Kugel shows in Traditions of the Bible: A Guide to the Bible As It Was at the Start of the Common Era, the book of Jubilees says that the people built the tower in order to “ascend on it into heaven” (Jub 10:19). 3 Baruch 3: 7–8 goes further, saying that the people not only wanted to ascend into heaven but wanted to pierce it—that is wage war against heaven and God, an explanation also found in the Babylonian Talmud (b. Sanhedrin 109a), Philo of Alexandria, 3 Baruch 2:7, and one of the Aramaic translations of Genesis (Neophyti). Such interpretations are not outlandish—or at least they are not completely fabricated out of thin air. They are fabricated in the sense that they are constructed, but early interpreters typically constructed their interpretation on the basis of other biblical texts. In the case of the war-on-heaven idea, interpreters often referred back to the story of Nimrod in Gen 10:8–10, which also mentions Babel, (re)interpreting the obscure statement about Nimrod there as indicating something evil or devious about him—he was proud, arrogant, or sinful. Kugel summarizes the “transformation” of Genesis 11:1–9 in such early interpretations as follows:

The real crime involved in the building project was the tower itself, which was intended for the purpose of “storming heaven” or some related evil desire. For this plan and the arrogant attitude underlying it the builders were punished. Their leader was Nimrod. He himself was a wicked giant and a rebel against God; he may have been aided by other giants. As a result of this deed, the people themselves were scattered and their great tower was cast down to the ground.

An impressive (re)interpretation to be sure, but—and here’s the rub—one that is not obvious from Gen 11:1–9 itself. What is fascinating in this particular case is how this “(re)interpretation” of the tower of Babel story—that the builders wanted to storm heaven—is often the common understanding of the text now. The content of the text has been usurped and replaced by its “(re)interpretation,” which is another indication of the story’s iconic status. But a return to the words of the text itself suggests other, equally compelling interpretations.

While the text does not clearly indicate what is wrong with the tower/city, God’s judgment and punitive action imply some sort of problem. And while the text does not clearly indicate that the humans wanted to storm heaven, it does hint at two possible motivations. First, there may be a hint of pride in the humans’ desire to “make a name for ourselves” (v. 4). This is a relatively common assumption in the history of interpretation. In the very next chapter it is God, not Abram himself, who makes Abram’s name great (Gen 12:2). However, David makes a name for himself later (2 Sam 8:13) without any negative repercussions or divine reprisals, so it is hard to say that “making a name” is always bad.

The second hint about the builders’ motivation seems to involve fear: they do not want to be scattered over the whole earth (v. 4). Indeed, this note of fear is the climactic one: building a tower and making a name is precisely to prevent (“lest. . . “) such scattering.

The first hint (pride) ties in with the history of interpretation, which has often hung much on a theory of hubris, but the latter hint (fear) is the opposite of hubris. It envisions a small group of humans hunkering down—afraid, perhaps, of this large new world. Far from storming heaven, this reading suggests the humans wanted to sink deep roots into local soil and not go anywhere on earth, let alone in heaven.

[T]he story of the tower should be read in its larger literary context, the entire book of Genesis, and in its immediate literary context, the first eleven chapters of Genesis.

If this fearful reading is correct, one might well wonder what is wrong or even sinful about being afraid and wanting to stick together. Perhaps nothing, but the story of the tower should be read in its larger literary context, the entire book of Genesis, and in its immediate literary context, the first eleven chapters of Genesis. There we find that God created humans precisely to fill the earth and steward it (Gen 1:26–30)—a point reiterated after the Flood narrative (Gen 9:1, 7). In this larger perspective, the hunkering down in Gen 11:4 is a refusal to fulfill the creational mandate. God’s punishment, while definitely a reversal of human desire, is not negative: it actually enables the humans to comply with God’s initial command. Describing the scattering as “God’s judgment,” in this light, is overstated: the judgmental act has nothing to do with the tower as such but with the city (a place of settlement) and the scattering abroad (v. 8). Moreover, this non-judgmental “judgment” is predicated precisely of Babel/Babylon, which, later in the Bible, will represent a dire threat and mortal enemy to Israel.

The scattering also has to do with the confusion of languages (vv. 7, 9), and this leads to another curiosity. The closest linguistic link to the scattering abroad is not Genesis 1 or 9, with their mentions of filling the earth, but rather with 10:18 which uses the exact same verb as Gen 11:4-9 (Heb pūş), and discusses how the family of the Canaanites “spread abroad” (Heb pūş). Similar sentiment, though different terminology, is found in 10:5, 32 (Heb pārad).

What is curious is that Genesis 10, which discusses different family/ethnic groups, comes before Genesis 11, which discusses the separation of languages, because one of the primary ways we distinguish different groups is precisely via language differentiation. To be sure, one should not expect ancient Israelites to be expert linguistic theorists; moreover, Genesis 10 probably comes from a different source/tradition than Genesis 11:1–9. Even so, the final ordering of the chapters is intriguing, if for no other reason than they are “dischronologized”.

At least two results of this (dis)ordering are worth noting. First, following the diffusion of people groups in Genesis 10, the hunkering down of the people in Genesis 11 can be more easily seen as a refusal to fulfill God’s command to populate the earth. Such unification is not what God wills. The story can thus be seen as an early witness to the importance—indeed, the divine legitimation—of pluralism and diversity. There is, according to the story, a kind of unity (national, linguistic, otherwise) that God does not will and a diversity (national, linguistic, otherwise) that God does will.

Second, it is possible that the unusual ordering of Genesis 10–11 functions to bring these chapters into line with a pattern previously established in Genesis, according to which humans cause some sort of problem to which God must respond. Fitting Gen 11:1–9 into this pattern means that it segues nicely into the call of Abram in Gen 12 and beyond, which thus becomes God’s next “response” to what humans have done. This interpretation may depend overmuch on a judgmental reading of God’s actions in Genesis 11, which, as we have seen, can be challenged, but if right, it would indicate that, in the final analysis, whatever its literary features, gaps, and ideology, the tower of Babel story may be a setup for the story of Abraham, another iconic text from the Hebrew Bible.

Feature image: The Tower of Babel, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Kunsthistorisches Museum. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

January 30, 2024

Less-than-universal basic income

Less-than-universal basic income

Ten years ago, almost no one in the United States had heard of Universal Basic Income (UBI). Today, chances are that the average college graduate has not only heard of the idea, but probably holds a very strong opinion about it. From Silicon Valley elites to futurists to policy wonks, UBI is igniting passions and dividing opinions across the political spectrum.

Much of the credit for this is due to Andrew Yang, whose 2016 presidential campaign took a centuries-old academic idea and transformed it into a focal point for conversations about poverty, inequality, and the future of work in an age of increasing technological automation.

Since then, the idea of UBI has taken off. The organization Mayors for a Guaranteed Income reports that it has sponsored almost 60 pilot programs in various cities across the United States, and the results of these pilots have been largely encouraging. In Stockton, California, a guaranteed income program not only reduced income volatility and mental anxiety, but significantly boosted full-time employment among recipients—by 12 percentage points, compared to a mere 5-point increase in the control group over the same period. A more recent experiment in St. Paul, Minnesota, showed similar increases in employment as well as improvements in housing and psychological wellbeing.

And yet, for all its popularity, the idea of UBI seems stuck at the level of a temporary experiment. No government has yet to implement UBI as a permanent, large-scale policy, and none seems likely to do so in the near-term future.

The UBI That Almost Was: Nixon’s Family Assistance Plan

After all, we’ve been here before. Back in the 1960s, a similar wave of enthusiasm for UBI (or “guaranteed income,” as it was called at the time) swept the United States. Milton Friedman popularized the idea in 1962 with his proposal for a Negative Income Tax. In 1968, a letter supporting a guaranteed income garnered over 1,000 signatures from academic economists and received front-page coverage in the New York Times. Finally, by 1969, Richard Nixon proposed his “Family Assistance Plan,” which would have provided a federally guaranteed income to families with children. Between growing bipartisan support and extreme public dissatisfaction with traditional welfare, it looked like the timing might be just right for the idea to actually become a reality.

Except, it didn’t. After months of struggle and compromises that left no one happy, the Family Assistance Plan ultimately failed to make it through Congress. The full story of its defeat is a complicated one, well-documented in Brian Steensland’s masterful book, The Failed Welfare Revolution. But, in essence, its failure came down to the same two objections that always bedevil guaranteed income programs: cost and fairness.

The Two Main Objections to UBI: Cost and Fairness

The issue of cost is a serious challenge for advocates of UBI. A grant of $1,000 per month would be close to enough to bring a single individual with no other income up to the poverty level. But a fully universal grant of $1,000 per month to all the roughly 330 million people living in the United States would cost almost 4 trillion dollars – more than half the entire federal budget for 2024! A smaller grant would cost less money, but the smaller the grant, the less effective it will be at lifting people out of poverty. Fiscal constraints thus create a dilemma that is difficult to escape.

The other problem is, if anything, even more difficult to manage. One of the defining features of UBI is its universality, meaning, in this context, that everyone is eligible to receive the grant, whether they are working or not. But it is precisely this universality that strikes many people as morally unfair. It’s one thing, the argument goes, to help people who are trying to support themselves but can’t. It’s quite another thing to declare that everybody is entitled to live off the federal dole, whether they’re able and willing to work or not. The old Victorian distinction between the deserving and the undeserving poor resonates deeply with a sizable majority of the American public, liberals, and conservatives alike.

It might be time to consider an alternative approach to UBI—one that avoids the main objections to the policy while retaining much of what makes it so attractive in the first place.

Of course, UBI advocates have responses to both objections. The cost of a UBI can be mitigated by imposing modest new taxes, consolidating existing welfare programs, or both. And claims of unfairness can be met by pointing out that just because full-time parents, artists, and caretakers aren’t working, this doesn’t make them free-riders. There are other ways of making a positive contribution to one’s community beyond participation in the paid labor market.

These responses are serious enough to merit more attention than I can devote to them here. But so far, at least, they have failed to persuade a majority of the American public. This doesn’t necessarily mean that they should give up. But it does suggest, perhaps, that it might be time to consider an alternative approach to UBI—one that avoids the main objections to the policy while retaining much of what makes it so attractive in the first place.

The Child Tax Credit as an Alternative to the UBI

We don’t have to stretch our imaginations to conceive of what such an alternative might look like. We’ve already tried it—at least briefly. In 2021, responding to the economic crisis caused by COVID-19, the United States made its Child Tax Credit (CTC) fully refundable. This meant that families whose income was too low to owe any taxes received cash payments from the government, the size of which depended on how many children they had. The results of this experiment were impressive. Childhood poverty levels fell to their lowest level on record—5.2%. When the expansion ended in 2022, child poverty more than doubled almost immediately, skyrocketing to 12.4%.

So far, efforts to make the expansion permanent have been unsuccessful. But its demonstrated success and relative popularity suggest that it might be the viable path forward for enacting a policy of large scale, no-strings-attached cash transfers.

First, because the CTC is limited to families with dependent children, its scope is far narrower than a fully universal UBI. Only about 40% of US households have children under the age of 18, so even keeping the size of the grant constant, a CTC cuts the cost of UBI by more than half.

Second, and perhaps more importantly, because the CTC is focused on families with children, it is much less vulnerable to the kind of worries about unfairness that plague UBI. Even if you think that there’s something morally objectionable about able-bodied adults being dependent on government support, surely that objection doesn’t apply to children. Children aren’t responsible for putting themselves in poverty. And they aren’t capable of getting themselves out of it. If anyone deserves a helping hand, it is children.

As Josh McCabe has recently noted, other countries such as Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom all have child tax credits that are at least partially refundable. The United States not only lacks such a policy, but spends less on cash transfers to children than any other country in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). No surprise, then, that the US also has the highest post-tax, post-transfer child poverty rates of any other country in the developed world.

For many of UBI’s supporters, its universality is one of its strongest appeals. And yet the objections about cost and fairness show that it might also be one of its greatest political liabilities. A permanent expansion of the Child Tax Credit has the potential to realize much of the promise of permanent, broad-based, unconditional cash transfers, while simultaneously avoiding the biggest pitfalls of UBI. In bridging ambition with practicality, expanding the Child Tax Credit could be the key to transforming the ideal of universal financial support into a sustainable reality.

Feature image by Andre Taissin via Unsplash.

January 29, 2024

Cello and the human voice: A natural pairing

Cello and the human voice: A natural pairing

I’ve heard the phrase “It’s the instrument most like the human voice and that’s why it’s so expressive” countless times over the years. As a cellist myself I’m probably biased to some degree, but I truly believe that the cello has a unique voice which wonderfully synergises with the human voice.

In addition to being a cellist, I’m also a composer of mainly choral music, so I was thrilled when Oxford University Press invited me to edit a book of pieces specifically for choir and cello, particularly as such an anthology has never been published before. How interesting and rewarding to bring together a collection of pieces where the cello is seen in all its varied guises!

The cello is hugely versatile: it is able to mingle with or stand out above or below the voices of the choir; it can provide a jazz walking bass or a baroque continuo; it can function as a soloist with the voices of the choir accompanying; it is able to produce a variety of textures and rhythmic drives with pizzicato strummed chords or arpeggiated figures; it can provide a solid bass beneath complex rhythms or harmonies in the choir. What other instrument could switch between any of these roles in a moment?

Its ambit encompasses the whole vocal range, from bass to soprano, and its timbre is very similar to the human voice. Its sound can be earthy, gritty, soulful, or joyful; able to convey the deepest emotion, just like the human voice. Cellist Steven Isserlis said of the instrument “Even physically, one’s relationship to it is somehow similar to a singer with his or her voice; the cello seems to become part of one’s body, as one hugs it close and coaxes mellow sounds from it”.

It is surprising that over the centuries comparatively little has been written for cello and solo voice—and even less for cello and choir. However, in recent years, music for cello and choir has become increasingly popular as composers (or commissioners?) seem to have discovered the wonderful possibilities of this combination.

Music for Choir and Cello includes not only new compositions but also adaptions of pieces from the classical canon, two of which I had the joy of arranging. “Agnus Dei II” from Palestrina’s Missa Brevis has long been a favourite of mine, and it was easy to reimagine this exquisite piece in a new setting for choir and cello.

Unlike the rest of the mass, which is for four voice parts, this final movement has an additional superius part which is in canon with the cantus, and thus seemed to lend itself perfectly to rescoring with the cello taking the superius (or second soprano) part. I experimented with bringing the cello down an octave for certain phrases in order to exploit the richer tones of the lower strings (and to give the cellist a break from playing high up on the A string for an entire piece!), but in the end decided to keep it at the original pitch throughout as this really draws the listener’s attention to the imitation between the upper two parts.

Whilst exploring other possible repertoire to arrange for the anthology, I came upon J.S.Bach’s uplifting and energetic motet Lobet den Herrn which struck me as an ideal contrast to the pure serenity of Palestrina’s music. Here, the cello functions in an entirely different way, playing a continuo part which often doubles the bass vocal line, and occasionally the tenor, and provides harmonic direction and rhythmic momentum beneath the largely contrapuntal voice parts.

I would love to think that the inclusion of these arrangements in Music for Choir and Cello might bring a couple of gems from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries to the attention of those who perhaps haven’t sung such music before. (After all, it’s not every choir that has Palestrina in its repertoire!) And of course, I hope very much that all the pieces in this book will be enjoyed by singers, cellists, and audiences alike.

Feature image by Isabela Kronemberger via Unsplash.

January 25, 2024

Could lonely and isolated older adults be prescribed a cat by their doctor?

Could lonely and isolated older adults be prescribed a cat by their doctor?

Many older adults struggle with isolation and loneliness. Could cats be the solution? At the same time, many humane societies have more cats to rehome than they can manage. Could lonely older adults be the solution?

Researchers at the University of Georgia and Brenau University developed a novel program where older adults were paired with a foster cat coming from a local humane society, with the opportunity to adopt. A Human-Animal Bond Research Institute (HABRI)-funded feasibility study explored the impact of this program on the older adult participants and the cats. Researchers explored how fostering a shelter cat could impact loneliness and well-being in older adults living alone. They also wanted to learn if these older adults would be more likely to adopt their foster cat after common barriers, such as pet deposit fees, were paid by the study. Could it really be a win-win situation?

The study enrolled adults aged 60 and older living alone and without any pets. Participants completed health surveys before placement with cats and completed follow-up surveys at 1-month and 4-months post-placement. Participants could choose to adopt their foster cat any time between 1- and 4-months post-placement. If participants chose to adopt their foster cat, the study paid the adoption fee, and a 12-month post-placement survey was completed.

Findings from the study revealed that loneliness scores significantly decreased at the 4-month mark after the cat fostering began. A similar 4-month improvement that approached statistical significance was observed for mental health. However, at the 12-month follow-up, loneliness scores were no longer statistically significant. The researchers suggest that these one-year reports were impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, which resulted in a substantial proportion of older adults experiencing elevated levels of loneliness.

Alexis Winger and AmbiAlexis states that before she got Ambi, “I lived alone, and the loneliness was becoming oppressive. Ambi has brought an end to oppressive loneliness. There are still times when I am away from people too long, when I have no one to talk to and lonelines settles in, but then Ambi settles into my lap or just runs through the room, and I am not alone. Ambi has brought me smiles, laughter, responsibility and love.”

The day that Alexis picked out Ambi at the Athens Area Humane Society to foster. Alexis states “I didn’t expect to find a cat for me at the first visit, but as I walked in, my eyes connected with hers in the end cage. The minute she was in my arms, she was mine.”

This is a picture and text message that Alexis sent to Sherry Sanderson, one of the researchers in the study, during the Pandemic.

Photo Credit: Alexis Winger

Alexis still gets lonely occasionally, but it is not the oppressive loneliness she felt before she got Ambi. Alexis says “Ambi has brought me an end to oppressive loneliness.”

Photo credit: Photo and text message Alexis Winger sent to Sherry Sanderson.

What about the cats? Almost all (95.7%) of study participants decided to adopt their foster cat at the completion of the study. Dr. Sherry Sanderson, the team lead and Associate Professor at the University of Georgia’s College of Veterinary Medicine, noted: “Our results show that by removing some perceived barriers to pet ownership, including pet deposit fees, pet adoption fees, pet care supplies and veterinary support, we can not only help older adults live healthier, happier lives but we can also encourage the fostering and adoption of shelter cats into loving homes”.

Dr. Kerstin Emerson, a Gerontologist in the College of Public Health’s Institute of Gerontology, Health Policy & Management at the University of Georgia, and an investigator from the study states, “In May of 2023, the U.S. Surgeon General stated that loneliness and isolation is an epidemic in this country, and their report placed an emphasis on the urgent need for a cure.” Dr. Don Scott, a Geriatrician and Campus Director of Geriatrics and Palliative Care from the Augusta University-University of Georgia Medical Partnership and also a researcher from the study, added, “The ill effects of loneliness and social isolation, particularly for older adults, are well-documented, and more strategies are needed to improve health outcomes for this population.” The investigators from this study plan to do a larger scale study. The hope is when an older adult seeks to prevent or ward off loneliness and isolation, they will collaborate with a support team prepared to explore feline companionship as part of an individualized holistic approach to care, and there will be programs in place and funding available to support this new approach to treating loneliness in older adults.

Judith Atkins and BashiJudith is semi-retired from nursing, but she still provides nursing care to some of the residents in the Senior Living Residence that she lives in. When recently asked what Bashi means to her, Judith sent back the following reply:

“He (Bashi) has been a comfort to two of my neighbors. While providing nursing care to a resident who was in hospice care, Bashi stayed with her until she died. I also took him to visit a resident with cancer and breathing problems when I went to visit. I also took Bashi to the nursing home to visit two people I took care of there.”

Judith went on to say, “He still enjoys catching balls and batting them into the hall closet, continues to steal straws from my drinks and claims all boxes. Best of all, he still likes my left shoulder to put his head on to make sure his world is okay. At night at times, I find him asleep on a pillow by my head. His love of people is unlimited, and he will try and go in any apartment with the door open to be loved on by strangers. He escapes into the hall to force me to exercise chasing him, and needless to say he is always the winner.”

Judith was ready to enroll in the study just days before the Pandemic occurred, and the Foster Cat Study was shut down for six months. Once the study resumed, participants were no longer allowed to go to the shelter to pick out their cats to foster. Rather Dr. Sanderson, would go to the shelter and send them pictures and videos of available cats they may be interested in. The picture on the left is from the very first time Judith met Bashi in her apartment. The picture on the right shows that their Human-Animal Bond remains strong. Photo credit: Sherry Sanderson

Judith and Bashi getting ready to make the rounds in the building to visit people. Photo credit: Sherry Sanderson

Judith and Bashi love to hold birthday parties at the Senior Living Residence where they both live. Here are pictures from Bashi’s second birthday party. Photo credit: (L) Sherry Sanderson; (R) Judith Atkins

Feature image by Pietro Schellino via Unsplash, public domain.

January 24, 2024

The intractable word caucus

At the moment, the word caucus is in everybody’s mouth. This too shall pass, but for now, the same question is being asked again and again, namely: “What is the origin of the mysterious American coinage?” A correspondent of The Washington Post asked me about it, and of course I told her that no one knows the answer and probably never will. She also asked me whether there are many such intractable words in English. I’ll devote an essay to her second question later. Today, I will highlight the main points in the long search for the etymology of caucus. My collection of about forty notes (almost all of them from old journals) covers the period from 1855 to 1943, and it may be of some interest to our readers to be exposed not only to the tentative results of that search but also to the process of discovery. The way to the truth, as we know from Hegel, should itself be of the truth.

In 1855 (this is my date), Latin caucus “cup, vessel,” from Greek, allegedly, “a vessel for receiving voting papers,” was suggested as the etymon of our word. Later researchers used to refer to drinking at meetings, rather than voting (!). This will be DERIVATION NO. 1. It still has a few supporters.

Two names loom large in our investigation. John Pickering, the author of an invaluable collection of Americanisms (1810), quoted William Gordon’s History of the American Revolution(1788) to the effect that the word had been around for “more than forty years.” If this statement is trustworthy, caucus must have been in use around 1738. Our earliest known mention of the word dates back to May 5, 1760. It occurred in The Boston Gazette (I have not seen the relevant page). The standard reference is to the diary of John Adams, the second President of the United States. To some investigators such an early date of caucus seemed unlikely, because caucuses originated in Boston (there is no disagreement on this point) close to the beginning of the Revolution.

Modern ship caulkers: no conspiracies. Caulking the Schooner, Falmouth Harbour, by Joseph Savern, Yale Center for British Art. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Modern ship caulkers: no conspiracies. Caulking the Schooner, Falmouth Harbour, by Joseph Savern, Yale Center for British Art. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Pickering derived caucus from the meetings of the caulkers of Boston for political purposes. A certain S.S. wrote in the first issue of The Historical Magazine that this derivation might be correct but wondered why the phrases caulker’s [his spelling] club or caulker’s meetings never turned up in print. Ship caulkers’ duties were most important: they filled in any gaps, to make the ship watertight. Pickering’s etymology has been accepted and rejected many times. Terms going back to the meetings of professionals occur not too rarely and tend to be obscure: compare the history of wayzgoose (see my post for December 9, 2009). Thus, DERVATION NO. 2: from caulkers. However, even if caucus has anything to do with shipyards, those caulkers were not workers but “disguised patriots of Massachusetts who met in shipyards.” Remember Pickering’s political purposes! “Caulkers meetings were held at night in Boston to talk over the ways and means for helping to drive out the English troops in the decade made famous for America by the declaration of 1776.” We end up with a kind of password, a piece of political slang, whose meaning was first clear only to the initiated. In the 1860s, Webster also derived caucus from caulkers. He wrote: “Private meetings of Boston citizens just at the outbreak of the Revolutionary war on behalf of some of the Caulkers of the town, killed by the British soldiers, the name being corrupted or changed to caucus meeting.” “The Boston Massacre” occurred on May 5, 1770. The second edition of The Century Dictionary says: “Such a corruption and forgetfulness of the original meaning of a word so familiar as calkers is improbable.”

James Hammond Trumbull. Walter Stollwein CDV Collection. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

James Hammond Trumbull. Walter Stollwein CDV Collection. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.In 1872 (if not earlier), James Hammond Trumbull, a first-rate expert in Native American languages, traced caucus to cau cau as’u, which he defined as “promoter.” The corresponding verb meant primarily “to talk to.” Variants of the Algonquin etymon of caucus have been defended and rejected in numerous publications ever since. This is DERIVATION NO. 3. In 1885 and much later, Walter W. Skeat supported, even if cautiously, Trumbull’s idea, and so did the 1890 edition of Webster’s dictionary. I can only join those who doubted that the Bostonians of the middle of the eighteenth century would have gone so far as to understand a Native American phrase, cherish it, and transform it into caucus. The existence of the word cockerouse ~ cockarouse “a person of importance among American colonists,” certainly from Algonquin, throws no light on the history of caucus.

It seems preferable not to squeeze the remaining information into the allotted space (my post usually fills about two computer pages, though this length is self-imposed) and to draw some preliminary conclusions. In investigating an obscure etymology, we can at best weigh the probability of the existing conjectures, and opinions are bound to differ. Responsible sources, unless they only say that the origin of caucus is unknown, tend to offer, even if hesitatingly, one of the three solutions mentioned above but do not give details for justifying their choice. Thus, Merriam-Webster’s dictionary (the online version) calls attention to the putative Native American source and to the derivation from calker’s [sic] meetings. A short essay follows, and more is said on the subject. There, we also find a brief reference to the first edition of The Century Dictionary, which (I must say, unexpectedly!) traced caucus to the Latin word for “cup.” As we have seen, the cup etymology predates the CD by almost fifty years.

Regardless of this chronological detail, I find a mere listing of conjectures counter-productive: it seems better to say as much as is known on the subject or nothing at all. Anticipating my conclusions, I’d like to note that that in my opinion, deriving our word from Latin caucus is fanciful. A description of those “smoke-filled” early meetings is extant. Drinks, we may assume, were provided, but unless the medieval ritual mentioned above (a loving cup going around) or some kind of communion cup defined the atmosphere, the conspirators hardly looked upon themselves as “the members of the cup,” similar to the knights of King Arthur’s Round Table. A vessel for voting papers looks even more fanciful.

King Arthur’s Knights, or a medieval caucus. Holy Grail Round Table, Bibliothèque nationale de France. Public domain via Picryl.

King Arthur’s Knights, or a medieval caucus. Holy Grail Round Table, Bibliothèque nationale de France. Public domain via Picryl.I tend to agree with the statement that the idea of a speedy “corruption and forgetfulness” of the word calkers inspires little confidence, unless the alternation was intentional, to hide the word’s origin. Finally, I do not share most lexicographers’ enthusiasm (even if guarded) for the Native American etymology of caucus. To repeat: did those people who met “for political purposes” know enough Algonquin to pronounce a long phrase correctly and change it into an English short word? Most Algonquin words in English are straightforward and denote animal names and other objects connected with the environment. Perhaps the only “societal” terms of Algonquin origin still used in American English are powwow “gathering” (and even that one is the result of a misunderstanding!) and mugwump “a person staying away from party politics.” The origin of those two nouns is straightforward, while deriving caucus from Algonquin presupposes a rather complicated process. I may refer to my favorite maxim that the more ingenious an etymology is, the greater the chance of its being wrong.

To be continued.

Iowa Caucus Night by John Edwards. CC by 2.0, via Flickr.

A librarian’s reflections on 2023

A librarian’s reflections on 2023

What did 2023 hold for academic libraries? What progress have we seen in the library sector? What challenges have academic libraries faced?

At OUP, we’re eager to hear about the experience of academic librarians and to foster conversation and reflection within the academic librarian community. We’re conscious of the changing landscape in which academic libraries operate. So, as 2024 gets underway, we took the opportunity to ask Anna França, Head of Collections and Archives at Edge Hill University, to share her impressions of the library sector and her experiences throughout the past year.

Tell us about one thing you’ve been surprised by in the library sector this year?I’m continually surprised and impressed by how quick the library sector is to respond and adapt to wider trends and challenges. The sector’s response to developments in generative AI is one obvious example from the past year (and one that I’ll speak more on later), but I think academic libraries have navigated some difficult years remarkably well and are continuing to demonstrate their role as a vital cornerstone of their academic institutions. I have worked in academic libraries for over 18 years and in that time I have seen the library’s role shift from being primarily a support service to becoming an active partner across a range of important areas.

What have you found most challenging in your role over the past year?In recent years, libraries have been at the forefront of conversations on wide-ranging and complex topics, including generative AI and machine learning, learner analytics and Open Research, while also placing an emphasis on support for Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion initiatives and the role of libraries in promoting social justice. These developments make libraries interesting spaces in which to work and provide opportunities for innovation and collaboration, but keeping up to speed as a professional with the most current information on a topic can be challenging. There is always something new to read or learn about!

There has been a lot of debate this year about the place of AI in academia. How has the progression of AI affected your library or role thus far?Supporting students to develop digital literacy skills has always been an integral role of the library at Edge Hill, but with advancements in generative AI and the increased risk that students will be exposed to erroneous or biased information, we know this is more important than ever.

As a library we have recently established a group tasked with looking at the potential impacts of AI on our services. I’m excited by the opportunities that AI might offer to deliver enhanced services for our users—for example, supporting intelligent resource discovery, improving the accessibility of content, and enabling our users to carry out their research more efficiently. I certainly think that libraries are uniquely positioned within their institutions to help drive and influence the conversation around AI.

What’s an initiative your library took in 2023 that you’re proud of?I am very proud of the work that has taken place around our archive service. Our archive is at the center of a new research group, Research Catalyst, which brings together library and archive professionals, academic staff, and students who are interested in how we can use innovative and interactive methods to research items in our collections. Research Catalyst has a focus on engagement and using the archive to connect with new audiences. One initiative involved us developing an online Archive Showcase and an associated competition which asked local school students and adults to create an original work inspired by the archive. This work led us to be shortlisted for a 2023 Times Higher Education Outstanding Library Team award—it was wonderful to have our initiative recognized nationally in this way.

Feature image by Mathias Reding via Unsplash, public domain.

January 22, 2024

A Q & A on English and all its varieties [interactive map]

A Q & A on English and all its varieties [interactive map]

With the rise of English as the world’s lingua franca, countries have adopted English in their own unique and fascinating ways. It is therefore more important than ever to record these words and phrases. We decided to talk to Dr Danica Salazar, the World English Editor for the Oxford English Dictionary, who takes care of projects relating to the varieties of English around the world.

What are World Englishes?

World Englishes are localized or indigenized varieties of English spoken throughout the world by people of diverse cultural backgrounds in a wide range of sociolinguistic contexts.

What is the World English programme and its importance?

One of the most interesting developments in the recent history of English is its rise as a global lingua franca. English is now used by billions of people in many different places on earth, and this is reflected by the many new words that make it into English from this amazing variety of people and places. Oxford Languages’ World English Programme aims to accurately and authentically document as many of these words as possible in our dictionaries and lexical datasets, including the historical Oxford English Dictionary and our dictionaries of current English.

Can you tell us about some of the different Englishes spoken across the world?

The World English programme covers a wide range of varieties of English. We document the vocabulary of countries where English is spoken as a majority first language, such as Canada, New Zealand, and Ireland, but also that of postcolonial nations where English is generally spoken as a second language and/or has some official status, like Nigeria, Singapore, and Sri Lanka. We look at varieties that characterize specific countries, but also wider regions such as the Caribbean and East Africa. We record words used by large English-speaking populations, such as those in India and South Africa, but also words used by much smaller Anglophone communities, such as that in Bermuda. We work on dialects determined by geographical boundaries, but also on sociolects spoken by different linguistic communities such as African American English and Hispanic Englishes spoken in the United States. We also include words from non-English-speaking countries, such as Japan and South Korea, which nonetheless have had a significant influence on the English lexicon.

There are a few exciting projects in the works at the moment. Could you tell us about the Oxford Dictionary of African American English?

The Oxford Dictionary of African American English (ODAAE) is a dictionary based on historical principles documenting the lexicon of African American English (AAE). The dictionary will be based on examples of African American speech and writing spanning the whole documented history of AAE. A team of lexicographers based in different parts of the United States are currently working on this landmark scholarly initiative, with input from an Advisory Board composed of renowned experts on African American language, history, and culture.

The ODAAE is a collaborative project between Oxford University Press and the Harvard University’s Hutchins Center for African & African American Research, funded by the Mellon Foundation.

What resources are available on the OED’s dedicated World English Hub?

The OED’s World English Hub is a section of the dictionary’s website that is dedicated to different varieties of English spoken around the world. It is publicly accessible and serves as a central repository for the content and resources related to varieties of English in the OED. There, one can find free articles, videos, teaching resources, pronunciation information, and more. There are also links to academic publications and news features, as well as a submissions form that people can use to suggest World English terms for inclusion in the OED.

The Hub features individual pages for most of the varieties covered by the OED, which contain even more information and resources specific to each variety.

What have you loved most about working on the World English programme?

I love working on the World English programme because, whatever variety we’re doing—whether it’s words from India, Singapore, Hong Kong, South Africa, the Caribbean, or the United States—I feel that I learn something new every day, not only about the words themselves, but also about the language, culture, and history of the people who use them. Each word I work on is like a little window into the everyday realities of English speakers all over the world, who adapt English vocabulary to accommodate their own traditions and values.

I also love that my work gives me the opportunity to travel and to work with experts from around the English-speaking world. I find it very rewarding working with people on documenting the varieties they speak natively or do research on, as this enables me to see the English language from different perspectives and opens my mind to new ideas. I find that this enriches not only my work but my life in general.

Featured image by CHUTTERSNAP via Unsplash.

January 17, 2024

Etymologicon and other books on etymology

Etymologicon and other books on etymology

In the previous post, I answered the first question from our correspondents (idioms with the names of body parts in them) and promised to answer the other one I had received during the break. But before doing that, let me offer my thanks and apologies to the reader who found a dreadful typo in the Latin phrase. Believe me: it is indeed a typo! I can only refer to the Russian saying that a sword does not cut off (“sever”) a repentant head and appeal to mercy before justice (Gnade vor Recht, as they say in German). Typos are a strange thing: one always misses the most obvious, the most glaring ones.

The second question concerned the book titled The Etymologicon: A Circular Stroll through the Hidden Connections by Mark Forsyth (New York: Berkley books, 2011. 279 pp.). The reader wrote that whenever she searched for books on etymology, that title invariably popped out as No. 1, as the best, etc. She asked me whether I could recommend it as a textbook for her high school students.

Let me begin by saying that assigning numbers to books (No. 1 or No. 2, or No. 10) is a thankless endeavor. We can say that The OED is the most complete English dictionary or that Hamlet is the most famous of all Shakespeare’s plays. There is likewise no harm in saying that a certain book is interesting, provocative, or conversely, uninformative, stodgy, and so forth, but “the best” and “the worst” should, in my opinion, be avoided. Who assigns those labels and on what grounds? Countless popular books deal with the origin of English words. Most have been written by non-linguists, that is, by engaged amateurs who can spin a good tale but have nothing new to say. This genre is useful and serves its purpose: readers (who are also non-specialists) are grateful for getting the information of which they have been previously unaware. The most successful popular books on etymology known to me were written about a hundred years ago by Ernest Weekley (1865-1954), a Romance scholar (who is also the author of a semipopular etymological English dictionary), and I am sorry that so few of them have been reprinted.

The Etymologicon started as a blog. The author characterizes himself as “a writer, journalist, proofreader, ghost writer and pedant. He was given a copy of the Oxford English Dictionary as a christening present and never looked back.” On the cover, his book is called #1 International Bestseller. I assume that this line is the source of the ranking our correspondent found on the Internet.

Those who have used the first and some subsequent editions of The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language know that an addendum to it contains a list of reconstructed Indo-European roots. Multiple words, seemingly unrelated in the modern language, are believed to stem from the same source. But one need not go back to prehistory, to discover amusing or puzzling connections. Compare stupendous, stupid, and stupor. A look at blank, black, bleak, and bleach reveals more complicated and not entirely clear ties. Another knot is pension, stipend, compensation, and pesos (p. 194). In dealing with English words of Romance origin, one runs into hundreds of similar examples. Forsyth explores many such obvious and hidden clusters. He also examines numerous other situations that one expects from a “popular book.” Among them are frequentative suffix (-le, as in fizzle, jostle, and so forth) and folk etymology.

A courtyard pathway: a sheer tautology. Photo by

form

PxHere

.

A courtyard pathway: a sheer tautology. Photo by

form

PxHere

.Forsyth often looks at words belonging to the same semantic sphere, such as drugs, or simply tells an entertaining story. Typical examples are the origin of the word tank and of the names of drinks like vodka and whiskey. Some essays are trivial, others show that he noticed an important phenomenon but did not quite realize how important it is. For instance, he mentions such place names as River Esk (pp. 174-75), that is, “River Water”: Esk goes back to a Brythonic word for “water,” and the result is a tautology, but the reader misses the information about the frequency of tautological compounds. Words like pathway, gangway, courtyard, sledgehammer “hammer-hammer,” and perhaps slowworm “snake-snake” and henbane, presumably, “death-death,” show that this curious redundancy is not limited to geography (see my post for June 21, 2006). Also, idioms attracted Forsyth’s attention. He mentioned the funny phrase before you can say Jack Robinson (p. 53) but was unaware of several more or less plausible explanations of it and vouched for the least convincing one. I also read with genuine surprise that “monkeys are called after monks” (p. 182). Monkey is a hard word and has to be treated seriously. (If anyone is interested, see my post for January 23, 2013.)

The river Esk. View south along the River Esk from Whitby New Bridge by Jeff Buck, CC BY-SA 2.0.

The river Esk. View south along the River Esk from Whitby New Bridge by Jeff Buck, CC BY-SA 2.0.To summarize this volume would be hard, because it consists of odds and ends: something about dictionaries, suffixes, and compounding, and something about alcoholic drinks and obscenities. Though a few sections produce a more or less systematic narrative, the indebtedness of the whole to a blog is clear at every step. There is nothing wrong with it, however. Think of books of fairy tales (One Thousand and One Nights, for instance): they don’t have to form a coherent whole. But I would hesitate to recommend Etymologicon as a textbook. I also winced at the author’s attempt to appear perennially relaxed and funny. Consider such passages as “Once upon a time there was a fisherman called Simon. He fell in with a chap called Jesus” (p. 135). “Funny chap Jesus. First, it’s a little strange to assert that a piece of bread is your body. If you or I tried that[,] we wouldn’t be believed. We certainly wouldn’t be allowed to run a bakery” (p. 166). Should an author always sound facetious to engage the readership?

Most emphatically: no connection. Via Pixabay and Pexels.

Most emphatically: no connection. Via Pixabay and Pexels.One can see that my opinion about this book is mixed. The collection is a mishmash and lacks depth, but this was of course to be expected, and such a reproach can be used against any author of a popular book on etymology. That Forsyth knows a lot need not come a surprise: anyone who spends years reading the OED, naturally, absorbs tons of useful information. Therefore, the reader will learn many interesting things from Etymologicon. Forsyth finds himself on treacherous terrain when he leaves his authority and ventures into the open. However, my main objection to Etymologicon is that it lacks style. I don’t believe that any author should beclown oneself and speak about that “funny chap Jesus,” to make an essay sound attractive. As for its being No. 1, let the public decide.

Feature image: Lexicographical order by Thomas Guest. CC by 2.0, via Flickr.

Living Black in Lakewood: rewriting the history and future of an iconic suburb [Long Read]

Living Black in Lakewood: rewriting the history and future of an iconic suburb [Long Read]

In the annals of American suburban history, Lakewood stands as an icon of the postwar suburb, alongside Levittown, NY, and Park Forest, Ill. Noted not only for its rapid-fire construction—17,500 homes built from 1950-1953—it was also critiqued for its architectural monotony, alarming writers at the time who feared that uniform homes would spit out uniform people.

That worry quickly faded when the demography of Lakewood began to change.

Since 1980, Lakewood moved away from its highly segregated white beginnings to a reality of ethnic and racial diversity. Along with other southeast LA suburbs like Carson, Bellflower, and Artesia, it represents one of LA’s most racially balanced towns, with a stable mix of whites, Black Americans, Latinos, and Asian Americans.

Lakewood’s official history has so far emphasized its original residents, especially the “original kids.” However, the next generation also deserves a central part in that story. Their experiences reveal not just how the suburb was becoming a place of new cultural variety and richness, but also how the community was learning to live with difference. The Chase family of Lakewood illustrates how far we’ve come from the days of Ozzie and Harriet in the 1950s. The Chase’s story of living Black in white suburbia was both predictable and unexpected, and it shows how suburbia—which now houses over half of all Americans—is becoming a place of profoundly varied experiences.

Louis Chase was born and raised in Barbados in 1943, in humble circumstances. Raised by his grandmother, he had deep ties to the Methodist church from a young age. At 14, he quit school “because of poverty” and went to work. He moved to London as a teen, where he first worked in textiles and then transitioned into community organizing and social justice activism. He earned a degree at Oxford, where he studied Pan-African movements, and met his future wife Marion, a nursing student at Coventry University who hailed from Jamaica.

In 1980, the couple immigrated to the United States and landed in Lakewood, where they purchased a home and started a family. They were the only Black family on their block. At the time, Lakewood’s Black population was 1,500, just 2 percent of all residents. Although they met little resistance when moving in, they faced prejudice from time to time. Louis was racially profiled by the Lakewood sheriffs who pulled him over without provocation, their two daughters were subjected to racial name-calling at school, and the family was often tailed by security guards on trips to the Lakewood Mall.

And yet, Lakewood also showed a warmer side. Louis started attending Lakewood United Methodist Church, an all-white conservative congregation. After attending his first service, which ran from 11 to 12, he returned home, and at 12:30 a member of the church showed up at his doorstep inviting him to join the church. When Louis hesitated, explaining that he didn’t have a car, the man offered to pick him up for Sunday services and meetings of the men’s group. And so began an enduring connection to Lakewood Methodist.

That church changed Louis’ life. Louis had been struggling to land a job in human relations work in L.A. The minister at Lakewood Methodist encouraged Louis to consider pursuing the ministry. He put in a good word at the Claremont School of Theology, and thus helped set Louis on a new career path. Louis became a Methodist minister, serving a number of churches around Los Angeles including Holman United Methodist Church, where he worked closely with James Lawson and other leading figures in the Black rights and anti-apartheid movements. He became an active part of the social justice community in Los Angeles, all while living in a suburb struggling with its own racial challenges.

The Chases’ first child, Cassandra, was born at Lakewood Regional Medical Center in 1981, making her an “original kid” of Lakewood’s second generation. By her own account, Cassandra led a very sheltered childhood, in part because of her parents’ desire to shield their children from racism. She was the only Black child among mostly white children in the neighborhood, at school, at Girl Scouts, and at Park and Rec activities.

The social milieu of Lakewood during this period of diversification was a mixed bag. Lakewood experienced a fair share of racial friction over the years, as it struggled to cope with racial change. After the passage of Proposition 13 (1978) in California, many communities lost funding for the human relations work that would have otherwise helped create a civic infrastructure to ease the process of ethnic and racial change. Instead, many communities, including Lakewood, had to figure things out on their own.

Latino and Black American residents in Lakewood recounted stories of both warm receptions and racist rebuffs. Some remembered neighbors welcoming them with cookies and cakes, which offered some reassurance and a sense of acceptance. Others recalled hostile neighbors and harassment from the Lakewood Sheriffs. Over the years, a number of white residents—including city leaders—expressed open resentment about the demographic changes, blaming it for a perceived decline in the parks and schools. In the early 1990s, when several Black American families were wrongly evicted from an apartment complex on racial grounds, local officials expressed more concern about Lakewood’s tarnished image than the plight of the ousted families. (Those families won a $1.7 million settlement for housing discrimination in 1997.) More often than not, Lakewood did not consider race relations a civic priority.

That changed in 2020. In the wake of the killing of George Floyd and intensified BLM activism nationally, Lakewood held two town hall meetings on race for the first time in its history. Among the 80 or so residents who participated via Zoom, many expressed their love for Lakewood and their desire to see race relations improve. Then, stories of racism and discrimination poured out. Cassandra Chase relayed the story of her cousin who was “walking while Black” in Lakewood while knocking on doors for his job with the Census Bureau, prompting a neighbor to call the Sheriffs. Two deputies arrived to question him, one with his hand very close to his gun.

Another resident of color relayed that they constantly got the question, “why are you here? We live here, we own property.” One resident described how they hated trash day—“People I don’t know assume I’m the maid or the gardener. I put trash out early now, so I don’t have to deal with that.” A Black American resident of Lakewood for 17 years described how her son came home from his third year of law school during the Covid lockdown. On a jog, a white man followed him back onto their block, “to make sure he lives on the block. My son sat on the porch. This was at the same time as Ahmaud Arbery was killed when he was out running…we were a little panicked.”

These public meetings laid bare the prejudice experienced by some residents of color in the community. Lakewood leaders responded by forming an ad hoc task force and issuing a “Community Dialogue Action Plan” which called for the creation of a Council Committee on Race, Equity, Diversity and Inclusion and quarterly meetings with community members on the subject.

Perhaps most significantly, in June 2022 Cassandra Chase won a seat on the Lakewood City Council, the first time a Black American was elected in Lakewood’s history. (Two years prior, a Black American had been appointed to the Council.) The suburb’s transition to a council district system may have helped Chase win office. She saw herself bringing to the position a diverse perspective in terms of gender, age, and race, and a commitment to increasing civic engagement and participatory democracy among residents. In terms of Lakewood leadership, her frank acknowledgment of Lakewood’s racial challenges marked a true break with the past.

Cassandra Chase, daughter of Lakewood and child of an activist minister, illustrates something significant about the future of changing suburbia. Her rise to power signals one iconic suburb’s pivot toward social and political pluralism. Chase laid claim to her hometown. To her, Lakewood “always felt like home. It’s home.” Just like legions of other new suburbanites of color, she is helping to rewrite the American suburban story.

Feature image: Lakewood Drive-In Theater, Lakewood, California 1981 by John Margolies. Public Domain via Library of Congress .

January 15, 2024

Your 2024 travel guide [reading list]

Your 2024 travel guide [reading list]

Now is the time for crafting your resolutions and setting the stage for a remarkable new year.

For those ready to become frequent flyers in the upcoming year, our curated reading list features ten exceptional books that will ignite your wanderlust and serve as invaluable companions on your journeys. Whether you’re seeking inspiration, practical travel tips, or a deeper understanding of the world, these books have got you covered.

So, gear up for a year of adventures and let these literary companions be your guide to a 2024 filled with exploration!

1. Venice: The Remarkable History of the Lagoon City [image error]Should the enchanting canals of Venice be your calling, look no further. This history book delves into the lives of the city’s diverse inhabitants — women and men, noble and common, rich and poor, spanning Christian, Jew, and Muslim. But it’s more than a history lesson; it’s an immersive experience, guiding you through the labyrinth of Venice’s past, from its intricate canals to an empire stretching from Northern Italy to the eastern Mediterranean.

In the pages of Romano’s masterpiece, Venice comes alive, inviting you to explore its rich tapestry and create your own connection with this extraordinary city.

2. Eliza Scidmore: the Trailblazing Journalist Behind Washington’s Cherry TreesBuy Venice: The Remarkable History of the Lagoon City by Dennis Romano

Dreaming of strolling through Washington DC, surrounded by the ethereal beauty of cherry blossoms in full bloom come March’s end? Pay homage to the remarkable woman whose vision brought Japan’s signature trees to America’s capital city. Eliza Scidmore: The Trailblazing Journalist Behind Washington’s Cherry Trees is the story of a remarkable woman and her life

Join the journey of this fearless maverick as she transforms a vision into reality, leaving an indelible mark on the landscape of Washington, DC.

3. Totality: The Great Northern Eclipse of 2024

Buy Eliza Scidmore: the Trailblazing Journalist Behind Washington’s Cherry Trees by Diana P. Parsell

Mark your calendars for April 8, 2024, when the total solar eclipse, will paint the skies across Mexico, the United States, and Canada. Are you ready to witness this cosmic extravaganza? This book is your essential guide to making the most of this celestial wonder.

Whether you’re a seasoned eclipse chaser or a first-time observer, Totality promises to be your indispensable companion, sharing the science, wonder, and the mysteries of the cosmos. Don’t just watch the eclipse; immerse yourself in its magic with the insights and expertise found within the pages of this captivating guide.

4. Facing the Sea of SandBuy Totality: The Great Northern Eclipse of 2024 by Mark Littmann and Fred Espenak

For the daring souls looking for an adventure of epic proportions, envision the journey across a colossal sea of sand that stretches from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea, dominating most of Northern Africa. Yet, believe it or not, the Sahara wasn’t always the arid desert we know today.

Embark on a captivating exploration of the Sahara in a journey that goes beyond the shifting dunes. Discover the tales of those who once inhabited the fringes of the desert and the ingenious ways they navigated its challenges. Whether you’re gearing up for a real-life expedition or seeking a mental getaway, this book unveils the gripping narrative of the intricate links between two worlds.

5. Dublin TalesBuy Facing the Sea of Sand by Barry Cunlife

Dublin, a city steeped in literary allure, has etched itself into the pages of some of the world’s most celebrated works. A harmonious blend of rich history and contemporary vibrancy, Dublin beckons millions with its warmth and character each year.

Dublin Tales weaves together stories that are vibrant, evocative, humorous, and diverse—each a unique dance with Dublin’s history, culture, cityscape, and its people. Spanning the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, these tales offer a kaleidoscope of perspectives that will kindle a profound connection with the city and its storied past.

6. Sand RushBuy Dublin Tales edited by Helen Constantine, Prof Eve Patten and Dr Paul Delaney

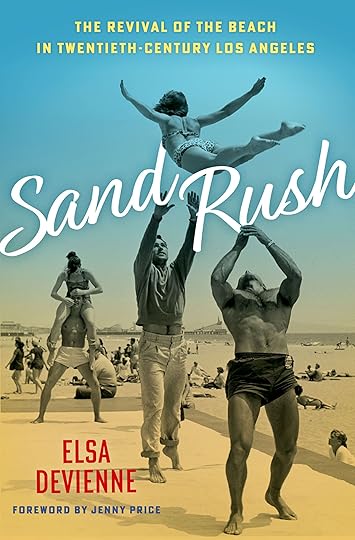

This summer, dive into the history of Los Angeles’ transformation into a coastal metropolis with Sand Rush. Unveiling the secrets behind the iconic shorelines of Santa Monica, Venice, and Malibu, this book exposes the reality behind the pristine sands seen in films and television. This engaging title takes you on a journey through the major planning and engineering project that not only constructed the city’s shores but also shaped the lives of its residents.

Sand Rush is more than a history lesson; it’s a compelling narrative of reinvented seaside leisure and the triumph of modern bodies against the backdrop of LA’s sprawling beaches. Immerse yourself in the stories of ordinary city-dwellers and witness the profound impact of this coastal metamorphosis.

7. Leaves from the Journal of Our Life in the HighlandsBuy Sand Rush by Elsa Devienne

As you set your sights on the adventures of 2024, why not let Queen Victoria be your guide? Immerse yourself in the daily musings of the monarch as she captures not only the serene family holidays at Balmoral Castle but also her sovereign journeys as the “Royal Tourist” around Scotland, Ireland, and the British Isles.

Complete with authoritative texts, historical context, maps of the Queen’s travels, and a cast of characters that bring her world to life, this book is more than a journey through history—it’s an opportunity to travel through time with one of the most significant figures of the Victorian era. Let Leaves from the Journal of Our Life in the Highlands be your royal guide to the captivating landscapes and stories of the British Isles.

8. Hopped UpBuy Leaves from the Journal of Our Life in the Highlands by Queen Victoria, Edited by Margaret Homans, Joanna Marschner, and Adrienne Munich

If you’re planning a pilgrimage to the heart of beer culture or seeking the lively atmosphere of your local Oktoberfest celebration, Hopped Up is your passport to the global beer meccas, from Munich’s Oktoberfest to the bustling streets of Tsingtao and the iconic pints of Guinness in Ireland.

Embark on a frothy adventure through the history and economy of beer and brewing around the world. From precapitalist times to the present, explore how virtually every country boasts its own iconic brew, whether it’s Budweiser in the United States, Corona in Mexico, Tsingtao in China, or Heineken in Holland. Unravel the surprising commonality among these labels — a light, crisp, clear Pilsner lager — and the tale of its journey as a product of Western cultural imperialism.

9. Atlas of the WorldBuy Hopped Up by Jeffrey M. Pilcher

Navigate the world with confidence using Oxford’s Atlas of the World, the singularly authoritative atlas updated annually to guide your journeys and adventures. This indispensable atlas provides crisp, clear cartography that vividly captures the urban landscapes and natural wonders across the globe.

For the curious explorer and the meticulous planner alike, the Atlas of the World is not just a map—it’s an uncommonly beautiful volume offering a diverse collection of information to enhance your travel experience in 2024. Chart your course with confidence, armed with the insights and visuals that only the most authoritative atlas on the market can provide.

10. The Happy Traveler: Unpacking the Secrets of Better Vacations

No matter where you’re heading, let The Happy Traveler be your essential guide to ensuring your travels are a source of joy, growth, and lasting memories. Authored by psychology professor Jaime Kurtz, this book draws on a wealth of research on happiness and decision-making to elevate your travel experience to new heights.

With a delightful blend of humor and adventure, Dr. Kurtz shares invaluable insights on crafting your perfect trip, igniting excitement before departure, and fully immersing yourself in a new culture while disconnecting from the technological ties of home. Learn how to cherish and share your travel moments, seamlessly re-enter your daily life upon return, and weave the secrets of happy travel into every day. The Happy Traveler is your passport to a more fulfilling and joyful travel experience.

Buy The Happy Traveler: Unpacking the Secrets of Better Vacations by Jaime Kurtz

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers