Oxford University Press's Blog, page 31

March 25, 2024

Conversations with Dostoevsky

The first time I visited St Petersburg, nearly thirty years ago, I stayed not far from the area in which Dostoevsky set the action of Crime and Punishment. The tenement blocks were, for the most part, those that Dostoevsky himself would have seen—indeed, one friend lived at Grazhdanskaya 19, a possible location for the coffin-like garret inhabited by Raskolnikov, the novel’s homicidal anti-hero. The area borders the Griboedov canal, along which Raskolnikov frequently walked and where the house in which he murdered the miserly old pawnbroker and her innocent sister is situated—I could even imagine that the dark figure emerging from the dingy entrance was the pawnbroker herself. Further away was the Haymarket, still crowded with gypsies, peddlers, beggars, and cheap food stalls, and—despite the old Church of the Assumption having been pulled down by the Soviet authorities to make way for a Metro station—still an atmosphere heavy with poverty and the crimes of poverty.

During those long walks, it was easy to feel that ghosts of Dostoevsky’s city lingered on in the mostly unvisited and run-down streets of the late twentieth century. There wasn’t so much traffic back then, and in the late afternoon sun, with only the distant shouts of some unseen workmen breaking the silence, there was a sense of timelessness, as if this is what it had always been like.

Sheer imagination, of course—and much more important is what Crime and Punishment and Dostoevsky’s other great novels (Notes from Underground, The Idiot, The Possessed, The Brothers Karamazov, and more) can mean for us today. We live in a material and social world very different from that of Dostoevsky’s characters but, like them, we still have to struggle with the challenges of finding a place in a competitive society that is endlessly generating economic insecurity, social injustice, family breakdown, and the fragmentation of religion and other value systems—as well, of course, as the eternal questions as to who and how to love, and whether, in the end, there is a God who cares.

The historical study of Dostoevsky addresses these questions by taking us back to Dostoevsky’s world—less to the canal-side streets and back-alleys of St Petersburg and more to the literary and intellectual culture of his time, placing him in the context of contemporary debates about literature, politics, faith, and, not least, the future of Russia itself. Historical scholarship goes a long way towards reconstructing Dostoevsky’s world and showing the detail of his involvement in contemporary issues of art and society and his approach to fundamental questions about the ultimate purpose of human life—and what a lot of detail there is! Even apart from the dramatic events of his mock execution, his imprisonment and exile in Siberia, his gambling addiction and often chaotic love life, Dostoevsky was extraordinarily active in the literary world of his time, editing a succession of journals that published both Russian and foreign literature, from Mrs Gaskell to Edgar Allan Poe (he admired both). He was interested in philosophy and at one point planned on translating Hegel, while Russian identity and the fate of Russia in the modern world elicited some of his most intemperate and controversial statements—and, of course, there was God! As Dostoevsky himself put it, the question of belief plunged him into a ‘crucible of doubt’ as he confronted the seemingly irresolvable clash between the Christian God of love and the reality of a world scarred by poverty, injustice, gratuitous cruelty, violence against women, child abuse, and much more—all addressed in his novels.

Historical study is one way of exploring these questions, but Conversations with Dostoevsky attempts the opposite approach. Instead of going back to Dostoevsky’s world, the Conversations bring Dostoevsky into ours, specifically into a series of conversations with a mid-career academic going through a rather average mid-life crisis—‘average’, that is, until, while he is reading one of Dostoevsky’s short stories, the writer himself appears. Thus begins a series of conversations that cover many of the themes of Dostoevsky’s fiction and non-fiction, focussing especially on the ‘eternal questions’ of God and that mysterious creature we call the human being.

History cannot be ignored, of course, and the Conversations are accompanied by a set of commentaries that explore the issues raised in a more conventional manner. Nevertheless, a fictionalizing approach can help to profile the existential questions at issue in his work and to help us reflect on how we, as readers, bring our own concerns and—inevitably—biases into what we read. In the century and a half since his death, Dostoevsky has been read in many ways—as a prophet of the Russian Revolution, as a spokesman for protest atheism, or as representative of Orthodoxy Christianity, and more. Today, his work is necessarily exposed to the critical rereading of the Russian literary and intellectual tradition provoked by the invasion of Ukraine that is taking place across Russian Studies. More than ever before, it is important to be conscious not just of what Dostoevsky wrote but of how we are reading him.

Featured image credit: Portrait of Fedor Dostoyevsky by Vasily Perov. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Does doctrine have a future in Christianity?

Does doctrine have a future in Christianity?

Why did Christianity develop doctrines in the first four centuries of its existence? After all, no other religion or worldview of late classical antiquity felt the need to do this. A school of philosophy might focus on propagating the teachings of its founders, yet Christianity seemed more concerned with clarifying the identity of Jesus Christ, before affirming his moral and spiritual vision. And what about the contemporary significance of these doctrines? Since these emerged in the culture of late classical antiquity, can they be disregarded today?

These questions have fascinated me since I began studying theology at Oxford in the 1970s. I was a late arrival in this field, having initially studied chemistry and earned my doctorate in Oxford’s Department of Biochemistry under the supervision of Professor Sir George Radda. I could not help but wonder whether there might be some interesting parallels between the development of scientific theories on the one hand, and Christian doctrine on the other. Reflecting on these questions took me the best part of fifty years. In The Nature of Christian Doctrine, I present a constructive and innovative account of the origins, development, and enduring significance of Christian doctrine, explaining why it remains essential to the life of Christian communities.

My original hunch that there might be some significant commonalities between the development of scientific theories and Christian doctrine is more plausible today than it was back in the 1970s. Since 2010, an increasing number of scholars of early Christian thought have explored the idea of early Christianity as a “theological laboratory,” which proposed and assessed various ways of conceptualizing its vision of reality. I suggest that doctrinal formulations are best seen as proposals submitted for testing across the Christian world, rather than as static accounts of orthodoxy. This approach aligns with the available evidence much better than Walter Bauer’s famous theory of suppressed early orthodoxies.

I argue that we can use Thomas Kuhn’s concept of a “paradigm shift” as a lens for understanding early Christian doctrinal development. Existing modes of thinking are found to be inadequate in explaining a diverse array of observations, leading to a “tipping point” in which new frameworks of interpretation are needed. There is an interesting parallel here with Christ’s remark that old wineskins are incapable of containing new wine. Furthermore, early Christian writers, such as Athanasius of Alexandria, seem to have employed something very similar to the modern scientific notion of “inference to the best explanation” in developing their accounts of the identity and significance of Christ.

While these may be the most original and interesting aspects of this volume, I also explore many other facets of Christian doctrines. I provide a robust critique of George Lindbeck’s still-influential Nature of Doctrine (1984), raising significant concerns about his crude reduction of doctrine to a single function. I point out that there are multiple functions of doctrine that we need to weave together into a cohesive whole, rather than limiting ourselves to a single preferred option. Drawing on the philosopher Mary Midgley’s concept of “mapping” as a means of coordinating the multiple aspects of complex phenomena, and Karl Popper’s “three worlds” theory, I explore how the theoretical, objective, and subjective aspects of doctrine can be seen as essential and interconnected. Christian doctrine both allows us to grasp the deep structures of reality, while at the same time creating a coordinating framework that ensures its various aspects are perceived as interconnected parts of a greater whole. Doctrine provides a framework that allows theological reality to be seen and experienced in a new manner.

So what difference does doctrine make? Why not simply embrace Christianity’s moral and spiritual vision and consider its doctrinal aspects as optional? I explore this question by considering some important connections between Christian doctrine and the Platonic idea of theoria—a new way of perceiving reality that encourages participation rather than mere observation. Doctrines provide a framework that alters our perception and experience of reality, influencing how we feel about the world and ourselves. Although many older accounts of Christian doctrine treat it somewhat rationalistically, I emphasize its imaginative and affective dimensions. It is not simply something that we understand; it is something that gives us a new vision of reality.

So does doctrine have a future? If the arguments presented in this book hold any merit, doctrine is crucial to the future of Christianity. It safeguards the core vision of reality that is essential for the proper functioning and future flourishing of Christian communities. It articulates the life-giving and life-changing realities that lie at the heart of the Christian community of faith. If Christianity has a future, then doctrine will be an important part of that future. In fact, I think the evidence allows me to go further: if Christianity has a future, it is because of doctrine.

Featured image credit: First Council of Nicaea (Damaskinos). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

March 22, 2024

How well do you know your ancient Greek literature? [Quiz]

How well do you know your ancient Greek literature? [Quiz]

From Homer to Euripides, ancient Greek literature has an abundance in poetry, prose and plays—but how well do you think you know these works? Test your knowledge with our short, fun quiz and don’t forget to let us know how you did!

Which of these Greek poets wrote a biography of Caesar?PlutarchOlenPindarAt the end of Oedipus Rex by Sophocles, what does Oedipus do upon realizing he has married his own mother?Kills his father, King Laius. Banishes himself to Egypt.Gouges out his own eyes.Which of the Greek tragedians wrote Medea (c. 431 BC)?Aeschylus SophoclesEuripidesWhich of these plays by Aeschylus is not part of the trilogy known as The Oresteia?The SuppliantsThe EumenidesAgamemnon In Homer’s Iliad, who kills Patroclus?HectorCerbriones Achilles Sappho was a prolific female poet from the island of Lesbos. Only one of her poems has survived in near-complete form. What is it called?Song of HermiaHeraOde to Aphrodite In The Odyssey by Homer, what do Odysseus’ sailors do to protect themselves from the Sirens’ call?Sing a ballad, describing their military successes, to drown out the noise of the Sirens’ song.Fill their ears with beeswax.Lock themselves below deck.The origins of the war in Ukraine [timeline]

The origins of the war in Ukraine [timeline]

The fall of the Soviet Union meant independence for Ukraine, and radically altered the shape and power structures of Eastern Europe. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 was the culmination of a number of growing fissures and collisions in the region—between Russia and Ukraine, but also between Europe and Russia, and Russia and the United States. Michael Kimmage, a historian and former diplomat who served on the Secretary’s Policy Planning Staff at the U.S. Department of State where he handled the Russia/Ukraine portfolio, looks at the origins of this conflict dating back to 24 August 1991.

Feature image by Max Kukurudziak via Unsplash.

March 21, 2024

Awkward? We’d better own it

We live in a golden age of awkwardness. Or so we’re told, by everyone from The Washington Post to Modern Dog Magazine. But we always have. A 1929 Life Magazine contributor writes, “These are awkward times, and I sympathize with the teashop waitress who approached a customer from behind and said brightly, ‘Anything more sir, I mean madam; I beg your pardon sir.’” What’s new isn’t awkwardness itself, but our upbeat attitude towards it; headlines tell us that post-Covid, “We’re all socially awkward now,” and public health campaigns urge us to “embrace the awkward” and talk openly about issues like mental health. But while reducing the stigma around mental health, addiction, and other issues is a good thing, we should be wary of our tendency to embrace awkwardness—or at least, we should be aware of the way in which we selectively celebrate awkwardness, and who gets left out of the embrace.

The idea that being socially awkward is a personality trait—and a sign of superior intelligence—has become a mainstay of writing about the (predominantly white and male) worlds of tech and finance. From Mark Zuckerberg to the recently disgraced Sam Bankman-Fried, the socially awkward genius is a familiar figure in the news these days. It’s found in fiction, too: Sherlock Holmes, even our beloved Mr Darcy. In these men, awkwardness is seen as not only excusable, but laudable—the true genius can’t be bothered with social niceties; he doesn’t notice such things. But this stereotype rests on a misconception about where awkwardness originates. In fact, people aren’t awkward—situations are. And one reason situations become awkward is because of individuals’ willingness to disregard others’ social cues, needs, and feelings. The myth of the awkward misfit is harmful when it’s used to license antisocial behavior, but it’s also used to exclude and stigmatize the neurodivergent, the disabled, and other marginalized groups.

That’s not to discount the fact that some people have more difficulty than others at detecting social cues; these individuals may feel, and be perceived as, awkward. But when we label people “awkward,” we attribute the problem to them, rather than to our failure to make social expectations clear. Programs like Rochester Institute of Technology’s Career Ready Bootcamp train autistic students in the so-called “soft skills” needed to succeed in job interviews and the workplace—skills such as where to look while talking (between the eyes, as a substitute for eye contact) and how to interpret and respond to open-ended questions (like “tell me something about yourself”). But this shouldn’t be a one-way process: employers can make interviews more accommodating, too, by asking more specific questions, or de-emphasizing the roles of small talk and considerations of whether a candidate will be a good “fit” in hiring decisions.

Indeed, the emphasis on awkwardness as a personality trait disproportionately burdens people who don’t conform, for various reasons, to our social norms regarding speech patterns, eye contact, or body type. It’s no coincidence that the “geniuses” I mentioned above are all relatively affluent, successful white men. When we see awkwardness as a property of individuals, our choice about whether or not to accept or even celebrate it intersects with other forms of bias and prejudice.

Our cultural assumptions about awkwardness put women at a double disadvantage. Whether in the workplace or at home, women are disproportionately tasked with “emotion work” like facilitating social interactions, smoothing over social discomfort, and managing others’ feelings. When conversations get uncomfortable, it’s women’s work to repair them. On the other hand, we stigmatize conversations about salaries, periods, postpartum bodies, etc., and these conversations are bound to get uncomfortable. More problematically, we’re prone to see that awkwardness as caused by the person who brings them up, and not by the social norms or stigma around the issues themselves. Our fear of being perceived as awkward, or of being seen as “making things awkward,” can function as a form of silencing, suppressing conversations about important issues like salary gaps, menopause, and microaggressions.

I’m not saying that the desire to embrace awkwardness, and to celebrate self-proclaimed awkward people, is a bad thing. Our fear of awkwardness and our desire to avoid awkward encounters is real, and we would be better off, in many cases, if we got more comfortable with discomfort. But all too often, we treat powerful people as if they’re immune from social expectations, tolerating or even celebrating their disregard for social norms as a sign of intelligence.

As long as we embrace or celebrate awkwardness as an individual trait, we risk embracing a solution that reproduces existing social biases and inequality. The intersection of awkwardness, gender, and status empowers some to disregard social conventions, while using those same conventions to keep others quiet.

What’s the alternative? First, we should be aware that awkwardness is a product of all of our discomfort with certain topics. It’s not something individuals cause or have. It’s the result of insufficient or inadequate social guidance for how to handle an issue. Second, where we do feel uncomfortable talking about issues, we should take that as an indication and an opportunity to improve our social infrastructure, clunky and odd as that process may seem. For example, many professors now ask students to share their pronouns on the first day of class. For some older faculty, this process may feel awkward. Over time, it becomes less so. And often, avoiding awkwardness comes at the expense of someone else’s discomfort: for example, the students who faced the choice between being the only ones to share pronouns or being consistently misgendered. The work of discussing menopause or menstruation should be shared by everyone—not left to women. New York City Mayor Eric Adams’ recent press conference discussing menopause and women’s orgasms may have made many viewers (myself included) cringe, but it’s a step in the right direction. Making topics like sex, health, disability, and neurodiversity less awkward to discuss will take work, and that work shouldn’t selectively burden members of marginalized groups.

Finally, we should look for areas where our social cues may not be accessible to everyone, and make our expectations more explicit. And if, after all that, someone still seems to disregard others’ comfort and our social norms around workplace behavior? Maybe he’s not so awkward after all. Maybe he’s just a jerk.

Feature image by Campaign Creators via Unsplash.

March 20, 2024

A Retrospective on “Origin Uncertain”

A Retrospective on “Origin Uncertain”

In early March, the mail brought me the expected complimentary copies of my recent book Origin Uncertain: Unraveling the Mysteries of Etymology, published by Oxford University Press (2024). The book is based on my contributions to this blog, and some of our readers may perhaps be interested in hearing how the events developed. The blog started on March 1, 2006, eighteen years (almost to a day) before the publication of the book. At that time, OUP inaugurated a series of blogs, and the “Oxford Etymologist” column was one of them.

Yet the story is much longer. My work on etymology began forty, rather than eighteen, years ago and grew out of the discovery that even the best dictionaries often say about the words they feature: “Origin unknown.” To be sure, the formula has several variants: “perhaps related to such and such a word” (often equally obscure), “of uncertain origin,” “origin disputable (contested),” and an array of adjectives like dubious and doubtful, but in principle, the result is always the same, that is, “unknown.”

Exploring the unknownThe first mysterious word I began to explore was heifer. Just why heifer piqued my curiosity is a special plot, not worthy of attention here. In any case, some time later, I wrote a paper about it, after which my work on other mysterious words never stopped. I am not a decorated veteran, but if I were asked about a medal I would like to receive as a sign of recognition, I would say: “Bronze, small format, with an image of a heifer rampant facing forward.” So much for my knightly aspirations.

What words, one wonders, resist language historians’ attempts to discover their origin? Surprisingly, all kinds: adz(e) and awl, bad and bamboozle, curmudgeon and Cockney, dandruff and drudge, and so on to the end of the alphabet (yeoman and zoot suit). We know neither who coined them nor what inspired the mysterious wordsmiths “to call a spade a spade.” Some such words are old, even very old, while others surfaced in the late Middle Ages, and still others emerged in our recent memory. Slang tends to be especially impenetrable.

When I was entrusted with this blog, I decided to avoid all trivial information and discuss only such words as belong to the group “origin unknown/uncertain.” Very early on, I devoted a short post to copacetic. Recently, longer essays on caucus and curfew have appeared. This does not mean that I got stuck in the letter C. The opposite is true. I have written more than 900 posts covering the entire alphabet. In some, I answered the readers’ questions and discussed their comments, but all in all, I think I have touched on the origin of at least 600 English words.

When OUP suggested that I write a book based on the blog, it also specified its size. The volume, now on the market, contains 330 pages, index and all. I had to choose the most attractive words and ended up with about seventy of them. To those I added four idioms, one place name (the mysterious Rotten Row), and three biographical essays: on the great language historian and etymologist Walter W. Skeat, the author of the English Dialect Dictionary Joseph Wright, and the little-remembered William W. John Thoms, the man who, among many other things, coined the word folklore.

How does one tackle “origin unknown?”Here I should say something about Thoms but will have to begin from afar. If dependable sources say “origin unknown,” what was there to write in the blog and in the book? Why bother? Ay, there’s the rub. “Unknown” does not mean “beyond redemption” or “undiscussed.” Usually the opposite is true: the attempts to solve the riddle have been numerous, but the solution evades the researcher. While fighting my real, non-heraldic rampant heifer, I realized that comprehensive bibliographies of English etymology do not exist. The same is true of Dutch, German, Scandinavian, and Romance linguistics. Nor has an English etymological dictionary with even near-exhaustive references to the scholarly literature been written. Fortunately, I found a rather old paper on heifer which contained good footnotes. It became clear that if I wanted to continue work on etymology, I needed a bibliography worthy of its name. The formula “origin unknown” had to give way to a full-fledged discussion of the state of the art.

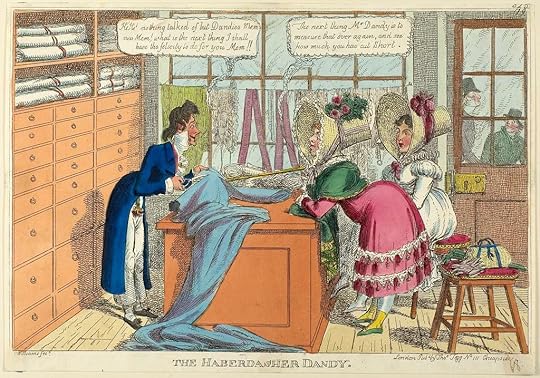

‘Book of Snobs VI – Page 26’ (1848), Oxford University, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

‘Book of Snobs VI – Page 26’ (1848), Oxford University, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.It took a host of volunteers and a few undergraduate assistants about twenty years to look through thousands of pages of popular periodicals like The British Apollo, The Gentleman’s Magazine, and The Nation in search of statements on word origins, while I screened the scholarly journals in about every European language for several centuries. The bibliography (a huge volume) was published by the University of Minnesota Press in 2009. (I have taught at the University of Minnesota since 1975.) Countless invaluable letters to the editor appeared in the British weekly Notes and Queries, conceived and edited for many years by Thoms. Hundreds of them dealt with word origins. English linguistics owes a huge debt of gratitude to that periodical, which, incidentally, spawned a whole gallery of offspring, including American Notes and Queries. Hence Thoms’s fully justified appearance next to Skeat and Wright.

All the words featured in my book are among the most problematic ones in English etymology. Here are some of them: awning (and tarpaulin), ajar, akimbo, bizarre, dildo, bicker, galoot, snob, dandy, henchman, bigot, haberdasher, shenanigans, Hoosier, and the much-vilified ain’t. For the fun of it, three relevant images have been selected to illustrate this post. In my work on the blog and the book, I depended on the comprehensive bibliography described above. Whether it was bizarre or Hoosier, I had at my disposal practically everything ever said about the history of those words in any source or language, and it was sometimes in the darkest nooks that I would run into a clever suggestion, overlooked by my predecessors. This is what happened in the essay on conundrum, to cite the most spectacular case. Samuel Johnson’s definition of a lexicographer as a harmless drudge has been quoted to death. Alas, it also holds for an etymologist. To reach the ever-hidden shining heights, a word-hunter should tread patiently through a quagmire and a desert.

‘Giuseppe Maria Mitelli – Standing Peasant with Arms Akimbo’ by Art Institute of Chicago, via Picryl.From blog to book

‘Giuseppe Maria Mitelli – Standing Peasant with Arms Akimbo’ by Art Institute of Chicago, via Picryl.From blog to bookTurning even seventy disparate essays into a cohesive unity turned out to be a difficult task. Sometimes I had to rewrite the post from scratch. In other cases, it was necessary to edit the text, remove repetitions, and add cross-references, because the chatty style of a standalone post and the flowing style of a book, however “popular,” are different matters. It is not always easy to steer between Scylla and Charybdis.

As could be expected, in my travels through the vocabulary, I did not solve all or most of the problems that had baffled my predecessors for decades, if not for centuries. But in all cases, I tried to present a full picture, reject groundless hypotheses, and choose what seemed to me the most promising solution, while making the story accessible to “everyone.” In a few cases, I think I could even suggest a promising way out of the impasse. Yet in the text, few references to scholarly sources appear. Those who will choose to pick up where I have left off will open my bibliography, familiarize themselves with the history of the question, and decide whether they can do better. In some cases, they will probably reject my solutions, as I have rejected numerous hypotheses of my predecessors. This is perfectly fine.

‘The Haberdasher Dandy, Charles Williams, England’ by Art Institute of Chicago via Picryl.

‘The Haberdasher Dandy, Charles Williams, England’ by Art Institute of Chicago via Picryl.The readers of the book will of course notice how often I suggest an “expressive” (that is, sound–imitative or sound -symbolic) origin of the most intractable words. Language must have been expressive in the remotest past, and it still is, even though we have learned to pronounce and understand words like supercalifragilisticexpialidocious and psychoanalysis. To return to my main point. Few people realize who difficult it is to write a “popular” book, without watering down the relevant facts and arguments. The uninitiated reader should be able to open the book by chance, feel intrigued, drawn to the page, and go on reading. Origin Uncertain was conceived not as etymology for dummies but as a detective story, a thriller. Let me quote the last sentences of the introduction: “Studying word origins is like participating in an eternal carnival. Masks beckon to you, tease, give a kiss, or bamboozle by unrealistic promises. All is about snipp, snapp, snorrum, an incantation Hans Christian Andersen liked, or, to use Hemingway’s phrase, a moveable feast.”

Feature Image: Book Labyrinth at the Last Bookstore, CC3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Who do you think you are? Genetics and identity

Who do you think you are? Genetics and identity

Ethnicity and ethnic identity have been recently brought to the fore in the Western world. One important reason is that immigration and globalization have resulted in a variety of clashes among different groups in very different contexts. However, there is another reason: DNA ancestry testing. Margo Georgiadis, president & chief executive officer of the major company in the field, Ancestry.com, has estimated that in early 2020, 30 million people had taken a DNA test, of which over 16 million was with her company. These companies tell you that by simply spitting into a tube or swabbing the inside of your cheek, you can find out a lot about your origins and your ancestors through DNA. Indeed, the way these tests are sometimes marketed may make people think that ethnicity is something “written” in their DNA. In many cases, people have to deal with surprising revelations that make them reconsider their ethnic identity, and in some cases reveal that the person whom they called father is their biological one.

Identity matters a lot to people, because it affects both how we perceive ourselves and how we are perceived by others. There are two big issues with how people tend to think about ethnic identity. On the one hand, it is assumed that people of the same ethnicity are a lot more similar than they actually are. On the other hand, it is assumed that people of different ethnicities are much more different from one another than they actually are. Therefore, once considered as members of particular ethnic groups, each person is no longer considered as an individual, but as a representative of particular ethnic types. This has an important consequence: people are not considered on the basis of what they really are, but rather on the basis of what they are expected to be given the ethnic group to which they belong. And this is where false stereotypes can easily prevail. Here DNA ancestry companies enter the scene by arguing that their tests can indicate to which ethnic group one belongs. Thus, these tests privilege notions of ethnicity based on genetics, contributing to the myth of genetic ethnicities.

Research in psychology has supported the conclusion that people believe that they have internal, immutable essences that influence who they are. This kind of thinking is called psychological essentialism; when genes, and DNA more general, are considered as being these internal and immutable essences, the view is described as genetic essentialism. This is an intuitive view that makes people find natural that they belong in one or another group, as well as that these groups are internally homogeneous and entirely discrete from one another. Therefore, if people intuitively tend to think of ethnic groups in genetic essentialist terms, it might seem natural to them that there exist discrete ethnic groups that are both genetically homogeneous and genetically distinct from one another.

Ethnic groups are real, but are socially and culturally constructed. More often than not, these groups have not had continuity across time historically, linguistically, culturally, and of course biologically. However, people intuitively tend to essentialize these groups, and DNA often serves as the placeholders for this. Population genetics provides an objective means for distinguishing among human groups; however, even though there are many different ways to do this, people (and researchers themselves) often tend to privilege those groupings that align with previously perceived, extant categories, such as continental and racial groupings. People living in the same continent are indeed more likely to have recent common ancestors among themselves than with people living in other continents. But what really exists at the genetic level are gradients of genetic variation, not distinct groupings. Human genetic variation is continuous and the genetic differences among people are overall very minor. For this reason, ethnic groups, nations, or races are not biological entities.

As a result, any ethnically, nationally, or racially distinctive genetic markers exist only in a probabilistic sense, and what ancestry tests provide are just probabilistic estimations of similarities between the test-takers and particular reference populations, consisting of people living today. But being related genetically to people living today somewhere does not necessarily mean that their ancestors came from that place. Furthermore, as more people take such tests, these reference groups change and as a result the ethnicity estimates for the same person can change across time. DNA provides partial information about our ancestors, which is the outcome of a process of interpretation. Therefore, DNA cannot reveal our true ethnic identity and the genetic ethnicities to which test-takers are assigned are imagined. However, this does not devalue these tests as their results can indeed provide some valuable insights and information to people who may not know much about their ancestors. Indeed, the tests are very good for finding close relatives, and this is perhaps why the industry should be rebranded to DNA family testing.

March 19, 2024

Music Publishing: Looking to the Future

Music Publishing: Looking to the Future

Music publishing is an exciting and fast-paced industry touching all our lives, whether as performers, composers, or music lovers listening in the car or in our favorite movies. Music publishers provide the conduit, the link, through which a composer’s or song-writer’s inspiration travels, allowing musicians and audiences to discover and explore different works. It’s a publisher’s job to disseminate as widely as possible the songs and the symphonies, the jingles and the jazz that we all so enjoy.

Embracing the technologyPublishing music has always been driven largely by both technological development and consumer behaviour, particularly in the multifarious ways through which music is delivered and consumed. Looking back, it is clear to me, for example, how publishers in the early twentieth century needed to respond (quickly!) to the mechanical reproduction of their music in then-new devices such as gramophones and pianolas. How were publishers and their composers to be paid for such use of their music? A new legal ‘right’ was the answer—the ‘mechanical reproduction right’—and from that rapidly followed infrastructures and processes to license and collect income from the soon-to-be ubiquitous availability and use of recorded and broadcast music. Oxford University Press, in the 1920s, was fast to embrace those new technologies commercially, issuing guides to ‘pianola repertoire’ and radio broadcasts, teaming with the BBC and Radio Times, and including gramophone records as components within some publications. Fast-forward to the twenty-first century, and we find ourselves still running that same race, keeping up with technological change and with the ever-hungry blanket consumption of music of all genres. There’s a near-constant need to find new solutions for delivering, monetizing, and protecting the music that we publish and into which so much inspiration, effort, and finance is invested.

Image: public domain via Pexels.

Image: public domain via Pexels.My role as Head of the Business Operations team at OUP entails understanding and embracing new technology and maximizing opportunities, whether through licensing, new partnerships, or perhaps reviewing our back catalogue for materials that we can refresh and supply in different ways and formats, always ensuring that we have the required legal rights: copyright drives our work, but equally important are our agreements with composers, authors, and partners. Publishing music is a collaborative business.

Music today flourishes in a digital environment. Composers create their music ‘manuscripts’ as digital notation files and, from these, publishers work to produce printed scores, orchestral parts for hiring, and new files which can be distributed and sold (and even streamed) online. Sound recordings are now made, stored, delivered, and consumed in digital formats. The joys of ‘digital’ are many: its durability, flexibility, and accessibility are all key advantages for music publishers and for the communities which make music. A conventional printed choral music anthology, chunky and possibly heavy for singers to hold, provides comprehensive access to a wide range of content in a fixed and immutable form. But, because the ‘content’ used to create that anthology is digitally based, it is now possible to split this up and easily supply individual items from such anthologies, allowing choirs to choose repertoire from the larger collection, in formats suitable for those choirs’ (or even for the individual singers’) needs. We as publishers informally call this process ‘atomization’: breaking the bigger publication down into its smallest useful components.

‘Atomizing’ the collectionTo give an example, in 2023 OUP issued the collection The Oxford Book of Choral Music by Black Composers (complied and edited by Marques L. A. Garrett)as one of a select group of special publications marking OUP’s centenary as a music publisher. This celebratory collection is ground-breaking in its new and diverse content, and it also looks forward in opening accessibility to that content: a handsome printed anthology, yes, and many choirs continue to purchase it in that format—but of its thirty-five separate items, twenty-seven have also been made available separately to purchase as digital sheet music downloads. And of those twenty-seven, twelve are additionally available as printed sheet music ‘leaflets’. Much of the content is available, too, to browse and peruse free of charge on the Yumpu platform, making choice and selection a simple matter. In parallel, all of this is backed up by equally accessible sound recordings of twenty-five of the anthology’s titles, available (again ‘digitally’) as streams through Spotify—these tracks can be used for repertoire selection, for learning, or simply for pure enjoyment.

The digital provenance of this anthology’s text and music notation files and of the audio recordings has clearly enabled the transformation of the Oxford Book of Choral Music by Black Composers from a traditional ‘single anthology’ concept into a flexible, convenient, accessible, and multi-component resource. Choirs are now even able to customize their own ‘collections’ from the bigger collection! As did our OUP predecessors with their pianolas and their gramophones, so today’s publishers embrace the new and the emerging technologies, working with platforms and partners, to ensure the widest possible availability of the music which we publish. In the digital environment that presence and access is now only ever a few seconds away—from anywhere in the world.

Looking aheadOUP Music’s centenary allowed us to reflect on the profound changes that truly impacted on the shape and the content of our catalogue—not only technological, but social, political, and attitudinal change, wars and conflicts, and (most recently) the immediate and wide-ranging effects of the Covid-19 pandemic (music publishing was first bowed by this, but then rose splendidly to the challenge of delivering and supporting music in new and creative ways).

But what of the future? The next one hundred years? All that is certain is that the ‘technology race’ will continue, as will societal and other developments, and that music publishers will have to (and surely will) keep up. Artificial Intelligence is merely the latest technology development, but it’s already challenging creator communities in terms of both content and its use, and the underlying copyright (as did those pianolas one hundred years ago, which essentially used ‘artificial intelligence’ to create live piano performances in real time, the same performances over and over again). The sophisticated digital supply routes with which we increasingly engage—and whatever may replace them in the future!—will mean that the old distinctions between ‘selling’ and ‘hiring’ and ‘licensing’ music will probably disappear or become blended. Solutions will be found and will be designed to continue delivering, in the best possible ways and to multitudes of users, the increasingly diverse and always exciting music created by our writers—across the globe, and possibly beyond.

Feature image by Kelly Sikkema via Unsplash.

Alice Mustian’s scandalous backyard performance

Alice Mustian’s scandalous backyard performance

The year 1614 was an eventful one for the London theatre world. Shakespeare’s Globe playhouse, rebuilt after having burned to the ground during an ill-fated performance of Henry VIII, was reopening its doors. Playgoers across the city could see performances of Ben Jonson’s Bartholomew Fair and John Webster’s The Duchess of Malfi. However, ninety miles away from London, in Salisbury, another play was performed that year, which was quite different from all of those: it was written by a middle-class woman, and it was staged in a temporary theatre in her backyard. Like much of the evidence about early modern performances in England, the story of this backyard performance was hidden away in archives for centuries; however, a recently reexamined lawsuit reveals the sensational tale of adultery, slander, and revenge behind this remarkable event.

On 4 September 1614, a Salisbury woman named Alice Mustian erected a stage in the backyard of her house on Catherine Street. Neighbours trickled in, paying a small admission fee (pins or pieces of ribbon) as they gathered in front of the make-shift stage constructed on top of tubs and barrels to watch a play that Mustian herself had written. The cast for the performance was a group of local children, including Alice’s ten-year-old son Phillip. The subject of the play, however, was hardly juvenile. Instead of a fictional tale, Mustian’s backyard play dramatized a very real piece of local gossip: that Mary Roberts, the wife of a joiner, had been caught having an adulterous affair with a baker named Robert Humphries. In some ways, Mustian’s astonishing decision to stage this salacious real-life story for her neighbours represented a kind of vigilante justice. When the townspeople of Salisbury had learned two years prior that Roberts was caught in a compromising situation with Humphries, some expected that the adulterous pair would be subjected to the traditional shaming ritual known as “carting,” in which the two would be paraded through the streets in a cart. This, however, never happened. Alice Mustian, thinking that their punishment was long overdue, took it upon herself to shame them both. In her backyard play, the troupe of local children, at Mustian’s direction, enacted the precise moment that Mary Robert’s husband, accompanied by a town constable, caught his wife with the undressed Robert Humphries, thereby exposing the affair. It wasn’t long before news of this backyard play reached the real Mary Roberts. Fiercely maintaining her innocence and furious that Mustian would try to shame her so flagrantly, Roberts immediately sued for defamation.

While the story of Mustian’s scandalous backyard play is remarkable, it is in one respect highly representative of early modern drama: the play itself does not survive and we only know anything about it through secondhand accounts, namely, the witness statements prepared for the ensuing defamation trial. Indeed, the majority of plays written and performed in the time of Shakespeare were never published and, in most cases, no complete scripts survive today in any form. Instead, theatre historians know about these plays through a wide range of types of evidence, such as playgoers’ diaries and letters, financial accounts, professional records, and manuscript fragments. This evidence might include titles, descriptions of performances, translations or quotations, backstage playhouse documents, payments to playwrights, or expenses for costumes and properties. As editors of the Lost Plays Database, a collaborative digital resource for compiling historical evidence and scholarly insights, we are dedicated to discovering as much as we can about these lost works of drama by examining the original documentary evidence.

The case of Alice Mustian proves to be a perfect example of just how much can be uncovered by locating and analyzing these primary archival sources directly. The six witness statements prepared for Mustian’s defamation trial are preserved in a single handwritten volume, a so-called “deposition book” prepared for ecclesiastical court cases, currently held at the Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre in Chippenham. The first scholar to discover these records was the historian Susan J. Wright, who mentioned them briefly in her doctoral dissertation about the social life of seventeenth-century Salisbury; a few years later, Martin Ingram cited the same case in the context of early modern English shaming rituals. While these brief early references were enough to alert later scholars to the name of Alice Mustian, no one had returned to the original legal sources of evidence to learn more about her. The amusing anecdote remained an anecdote and wasn’t investigated further.

In recent decades, however, scholars have increasingly turned their attentions to the fascinating body of dramatic writing by early modern women, including such plays as Elizabeth Cary’s The Tragedy of Mariam (printed in 1613), or Mary Wroth’s Love’s Victory (c. 1617) and Jane Cavendish and Elizabeth Brackley’s The Concealed Fancies (c. 1645), both preserved in manuscript. In light of this scholarly work, a more complete story of Alice Mustian’s backyard play demanded to be told. Even though her play itself does not survive, the legal records that do provide clear evidence that a woman from a very different social world than Cary, Wroth, Cavendish, and Brackley could write a play—and indeed that, like the professional dramatists of the London stage, a woman could write a play for the express purpose of public performance. The story of Mustian’s backyard play, in other words, underscores Ramona Wray’s claim that “Early modern women’s drama was restricted neither by social status nor by site of activity” and that “the extraordinary richness of kinds of performance […] sensitise us to women who purposefully engaged in playing actions across of range of institutional and informal, licensed and unlicensed, settings.” For us, the case of Mustian reminds us that the evidence awaiting discovery in the archives might very well change our understanding not only about the kinds of plays that were written in early modern England but also of the kinds of voices who once wrote those plays and poems that may not have survived into the present. It exemplifies the kinds of stories that have yet to be discovered in the archives, stories that can profoundly change what we think we know about the drama of Shakespeare’s time. In the case of Alice Mustian, we find a powerful revision to our ideas about who could be a playwright.

Feature image by Joanna Kosinska via Unsplash.

March 18, 2024

Explore the history of Asia in ten stops [interactive map]

Explore the history of Asia in ten stops [interactive map]

Embark on a captivating journey through pieces of the rich tapestry of Asian history with this interactive map of reading suggestions. Within these ten works, readers will encounter a rigorous examination of the historical trajectories, socio-cultural dynamics, and geopolitical intricacies that have characterized much of Asia’s evolution across epochs. Engage with renowned scholars and historians as you navigate through these ten essential works, each offering unique insights into the vibrant and intricate mosaic of Asian history.

Some stops on the map include access to chapters, free for a limited time, as well a select number of open access journal articles.

Feature image: Pink and yellow umbrella on brown wooden table by Ice Tea. Public domain via Unsplash.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers