Oxford University Press's Blog, page 34

February 16, 2024

The third sister: beauty, and why the aesthetic matters

The third sister: beauty, and why the aesthetic matters

In the current critical/political atmosphere, the “aesthetic” has come to be regarded as the province of dandies and their descendants, not to do with the enormous difficulties of the here and now. What work, if any, as the sky threatens to collapse over our head, might the aesthetic do to help us out of this mess? Can one make the case that the aesthetic is not peripheral to all that matters in this tumultuous, difficult, and utilitarian world, but that it always has been and is still an urgently valuable element in it?

We have seen, particularly with the crisis of COVID—which closed cinemas, theaters, concert halls, and museums—how immediately and pressingly society manifested a deep need for the arts. They proved essential to the psychological wellbeing of millions of people, and their absence from public life had economic impact as well. People sought and found new ways to perform, to hear, to see those elements of social life, literature, film, theater, music, graphic art, for which they are now not eager to pay for in the education of their children.

On the one hand, in both England and America, the humanities, with their crucial aesthetic components in the arts, are regularly defunded for the sake of more obviously utilitarian studies. On the other hand, within the humanities themselves, the aesthetic components of the arts are being increasingly ignored in favor of more apparently urgent political problems. As Ankhi Mukherjee puts it, in much criticism “political…stands for literature that is not beautiful.” The Question of the Aesthetic argues that the aesthetic should be seen as a mode of knowledge—not incompatible with such currently inflammable issues as imperialism, or race, or gender, but as an important means to understanding them.

The peculiar value knowledge the aesthetic generates is not discursive and generalizing but singular, emotive, and humanizing. Knowledge of the aesthetic helps pose critical questions that disciplines and discourses inattentive to problems like form or “beauty” cannot. The aesthetic, as Herbert Tucker puts it, “can provide a salutary check on the rush to relevance in contemporary humanities study, which will labor to better effect, even in service to causes that summon it most urgently, as it redoubles attention to the resources of artistic form, and the unexpected truth that beauty harbors.”

The Question of the Aesthetic attempts to address this double difficulty—the idea that the aesthetic is peripheral to the urgencies of human life, and the idea that attention to it deflects attention from the issues that really matter. Although the conventional understanding of evolutionary development is that all species change as a result of fundamentally utilitarian pressures, a strong case can be made that the aesthetic sometimes trumps the utilitarian. Richard Prum argues that aesthetic preference, the desirability of the beautiful, has played a crucial evolutionary role, as on the model of Darwin’s sexual selection: new species have often emerged out of the preference of one sex for beauty in the other, as evidenced by the astonishing elaboration of the peacock’s wings.

But while this argument should be taken as one piece of evidence that the aesthetic is not only compatible with the fundamental needs of human life, but in many cases is a critical element in satisfying those needs, it should be supplemented with broader understanding. With their attention to the facts of history, to the language in which that history is embodied, to the very materials of art and the cultural and political and economic conflicts that mark the lives of everyone, art engages with the felt experience of the facts. Through aesthetic representation, unattended facts speak, or can speak, across cultures, opening to fresh understandings of the other. It is not by chance that various forms of art—in music, poetry, fiction, film—become the media through which human experience, in conflicts, oppression, liberation, and simple suffering or simple joy, are most forcefully articulated. The power of critique of such representation is critical to whatever future the world can work out for itself. The beautiful—the traditional subject of aesthetics—should be an unembarrassed sister of knowledge and ethics, and a vital condition for that intellectual and moral work.

“The humanities,” concludes Helen Small, “have a special interest in the experiences of beauty…as they alter the quality of our perception and understanding of the world—recognizing that what moves us is at once private and shared, conventionally determined and constantly subject to change. …It is in the process of acknowledging, discussing, debating, disputing aesthetic experience…that much of our social and political experience takes place. Critical to that thinking is the power aesthetic experience affords us to apprehend the idea of agency through language, and thus be in a position to respond better to the reality of injustice.”

Featured image: Ayush Tiwari on Unsplash.

February 14, 2024

“Indian summer” and other curious idioms

“Indian summer” and other curious idioms

Part 1: Indian summerThe Internet is full of information about the origin of the phrase Indian summer. Everything said there about this idiom, its use, the puzzling reference to Indian, as well as about a desired replacement of Indian by a word devoid of ethnic connotations and about the synonyms for the phrase in the languages of the world, is correct. Obviously, the idiom emerged in the United States, and obviously, Indian has something to do with the rites or customs of the indigenous population, even though the phrase was coined by English speakers, rather than translated from some Native American language.

All sources mention the study of the idiom by Albert Matthews, an outstanding researcher of American English (among many other things). The honor accorded Matthews is fully justified, because his conclusions still stand. Indian summer surfaced in print in 1790, which means that it was known some time earlier. The reference has always been to a spell of good weather in November, and the suggestion that the short warm period witnessed some activities peculiar to the customs or habits of the native population is unobjectionable. It only appeared hard to guess what those activities consisted of: hunting, setting fires, or even attacking white settlements.

In the periodical Notes and Queries for September 2017, pp. 503-505, Dr. Matthew R. Halley of Drexel University, Philadelphia, published a clipping from an early American newspaper (Poulson’s American Daily Advertiser), which contains a new etymology of the idiom. The text is a letter to the editor, almost certainly by Reuben Haines III (1786-1831). Below, I’ll reproduce the gist of his etymology (see p. 505). There used to be, we read, an annual fair in Philadelphia for three days, beginning on the last Wednesday in November. The fairs were discontinued soon after 1788 (just when the phrase Indian summer turned up!). As long as they existed, they were regularly attended by the Native population. People brought there all kinds of articles to exchange for what they could find at the fair. “In those days, as ever since about this season, there generally happened a few very pleasant days: these pleasant days frequently coming at the time the Indians came to the fair, gave the idea that they brought the summer with them. … there is no specific time for the Indian summer; consequently, when a few pleasant days occur the term is applied to them.”

Like Dr. Halley, I believe that this simple explanation solves the riddle. The surprising thing is that the phrase Indian summer gained almost immediate popularity in the rest of the English-speaking world. I don’t know how many people still read John Galsworthy, but his interlude “Indian Summer of a Forsyte” (1918) is one of the best tales he wrote.

Part 2: Mysterious idiomsCollecting the data for the book Take My Word for It: A Dictionary of English Idioms took me about ten years, and an additional reward for this labor is a huge filing cabinet full of xeroxed pages from all kinds of periodicals for about three centuries—indeed, many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore. However, my goal was not to cite and illustrate those quaint and curious phrases (since the seventeen-hundreds, many full dictionaries of English idioms have been written by antiquarians, amateurs, and professional linguists) but to say something fairly convincing about their origin. In many cases, a correspondent to The British Mercury or Long Ago, to mention two little-remembered titles, would ask questions that were never answered. As a general rule, I did not include such idioms in my book. But it seems a pity to let all of them die in my office. Once I retire, they will probably be recycled. That is why I am going to publish some of the discarded phrases in the blog “The Oxford Etymologist.” What if someone has heard them or has an idea about their origin? My plan is to add a few phrases to at least some future posts. Today’s batch comes from Notes and Queries.

[image error]Wellcome Collection","created_timestamp":"0","copyright":"","focal_length":"0","iso":"0","shutter_speed":"0","title":"","orientation":"0"}" data-image-title="image-from-rawpixel-id-13991308-original" data-image-description="" data-image-caption="An old man leans over a table counting the money in his hand as a girl peeps through the door. Etching by T. Sibson.

More:

Original public domain image from Wellcome Collection

" data-medium-file="https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa..." data-large-file="https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa..." src="https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa..." alt="" class="wp-image-150028" style="width:288px;height:auto" srcset="https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa... 2088w, https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa... 180w, https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa... 158w, https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa... 120w, https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa... 768w, https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa... 1253w, https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa... 1670w, https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa... 128w, https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa... 184w, https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa... 31w" sizes="(max-width: 2088px) 100vw, 2088px" />The authentic Matty Murray? CC0 via rawpixel.(1856) “I have heard a servant-girl say the other day, speaking of the growth of an infant, ‘Aye, he is growing like Matty Murray’s money.’ Upon my inquiring the source of the adage, she was unable to give me any further information on the subject, beyond ‘It’s only a saying we have’.” Today, the idiom sounds especially funny because of the existence of the Canadian professional ice hockey goaltender Matt Murray. For some reason, the questioner assumed that the proverbial Matty was a woman of Sottish descent. Be that as it may, Matty Murray must have hailed from Scotland, and the only obvious thing about the phrase is the alliteration, though there may have been a local tale about Matty’s ever-increasing riches. As far as I can judge, the heroes of such tales are most often apocryphal, but perhaps someone knows the source of the idiom. If so, don’t hide your light under a bushel.

The next idiom I did include in my book, charmed by the beauty of it, but it still would be good to understand how it came about. (1879) “‘There she lies fast asleep with her hands full of pancakes’. I heard this said of a child the other day in Berkshire [a county south of Oxfordshire]. Can any of your readers supply an explanation why sound sleep should be associated with pancakes?” No one could.

But where are the pancakes? Pickpik. CC0.

But where are the pancakes? Pickpik. CC0.(1879) “‘To hang Jos’. This is an expression I hear occasionally in North Staffordshire [central England]. It means ‘to encroach on provisions reserved for some particular occasions’. I believe it is also used in other districts. I am unable to discover its origin.” Joz, we can assume, means “Joseph.” Is there an obscure reference to Joseph’s interpretation of the Pharoah’s dream about seven fat and seven scrawny cows?

Not a dairy farm. Mother shelters goslings, CC2.0. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Not a dairy farm. Mother shelters goslings, CC2.0. Via Wikimedia Commons.The last piece for today is not unknown, but the reference remains puzzling. (1929) “In an American ‘Wild West’ Magazine I came across the following dialogue: ‘Nigh ten years they have been thumbing their noses at us, an’ here you two shoot them all in ten minutes’. ‘Goose milk, Sheriff, not so quick as that’. If this is a Untied States slang phrase, what is its meaning?” I know the phrase, because decades ago, I found it in a dialog between Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn. Tom says: “My plan is as mild as goose milk.” Actually, his plan for setting Jim free is incredibly complex and silly, but apparently, he means that everything will go swimmingly and that the stratagem is simplicity itself. Mild alliterates with milk, and this is the only thing that is clear. Mark Twain’s use of dialect in the novel, published in 1885, leaves nothing to be desired (the subject has been studied more than once). I assume that goose milk is a southernism (Missouri?). The phrase did not make its way into the great Dictionary of American Regional English. Probably no one uses it now, though people understood it as late as 1929. In the magazine story, goose milk seems to mean something like “don’t jump to conclusions.” Perhaps Tom’s words also imply some negative sense, because he is objecting to Tom? After all, milch geese do not exist, and whatever milk may be expected from them will certainly be “mild.” Today, the phrase is obscure. The presentation, as they say at conferences, is now open for discussion.

Feature image: Indian Summer Scenery on Cayoosh Creek by Roger Sylvia. Panoramia Web Archive. CC3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

February 12, 2024

Aleph-AI: an organizing force or creative destruction in the artificial era?

Aleph-AI: an organizing force or creative destruction in the artificial era?

The Aleph is a blazing space of about an inch diameter containing the cosmos, Jorge Luis Borges told us in 1945, after being invited to see it in the basement of a house. The Aleph deeply disrupted him, revealing millions of delightful and awful scenes simultaneously. He clearly saw everything from all points of the universe, including the sea, the day and the night, every single ant and grain of sand, animals, symbols, sickness and war, the earth, the universe, the stunning alteration of death, scrutinizing eyes, mirrors, precise letters from his beloved, the mechanisms of love, his blood, my face, yours, and apparently that of every single person. Borges felt endless veneration and pity. He feared that nothing else would surprise him after this experience.

Amelia Valcárcel proposes that technological progress equated us with an Aleph with a display of about six inches. She compares Borges’ Aleph with mobile phones, which are accessible to most people. Now, I think we have at our fingertips the third generation of Aleph, what we could call Aleph-AI. We use this new Aleph not only to see everything, but to work from everywhere, communicate whenever we want, get travel directions, play games, search for specific information, trade without borders, conduct banking, take pictures and notes, get instant translations or suggestions for completing a message, get product recommendations that we are likely to buy, listen to a personalized list of music, and perform an endless list of activities powered by AI. Has the 6 inches Aleph-AI become creative destruction, or an organizing force in the artificial era?

Some workers feel threatened with being replaced by AI applications and losing their jobs. Fear has knocked on the doors of several unions, including operators, customer service representatives, artists, manual workers, or office workers. For example, Hollywood artists protest because they fear losing control of their image by being AI simulated and replaced by computational creativity. Customer service representatives fear being replaced by chatbots, manual workers by robots, and office workers by a variety of AI innovations.

On the other hand, economists argue that AI can make us about 40 percent more productive and drive economic growth through the use of a virtual workforce. AI innovations could even generate new revenue streams. In recent years, startups have been growing in record time, thanks to internet connectivity that almost everyone can get on highly accessible devices. Trading products and services hasn’t been as seamless as it is now, thanks to AI innovations in the palm of our hands. Governments can potentially easily apply regulations and taxes through a mixed bag of applications that serve millions over their mobile phones, says Thomas Lembong, who optimistically views this as more of an organizing force than a force of creative destruction.

But we can not deny that some people will suffer from the impacts of this unstoppable force. History shows that every time innovations occur, some people face negative effects and react with fear. When Jacquard looms appeared at the beginning of 1800, artisans united under the name of Luddites. They protested, destroyed, and burned textile fabrics. Skilled textile artisans were frightened by the introduction of a technology operated by workers, who could finish their job at a much faster speed, easily operating Jacquard looms. Some intellectuals supported the Luddite protests. Among them was a well-known poet of the time, Lord George Gordon Byron, Ada Lovelace’s father. Today, Ada Lovelace is recognized as the world’s first programmer and AI forerunner, who could have been fascinated by Jacquard looms’ binary technology, suggests Hannah Fry. Indeed, Ada Lovelace pioneeringly noticed the great potential of computers to perform any complex task, like composing music. Luddite protests lasted two years and died out after the English government enacted the death penalty for those caught destroying fabrics.

Technological progress will follow its path, and we are going to adapt. Did painters disappear when photography appeared? No, they re-invented themselves. Many techniques appeared: impressionism, expressionism, cubism, and abstract art, to mention a few. Previously, painters made a living from portraits. Today, we take selfies. How many of you have hired a painter for a portrait? With Aleph-AIs in our hands, we retouch pictures taken on our own. Will actors be entirely replaced by AI? Not happening. The changes in the film industry will be led by a group of professionals, including artists, computer scientists, entrepreneurs, lawyers, and policymakers. This will be the case in every sector and industry. Will there be suffering? Change is suffering. Change is new possibilities. Change could be re-thinking what we want for the future during the artificial era.

Feature image by Anna Bliokh via iStock.

February 7, 2024

Intractable words

In my correspondence with the journalist who was curious about the origin of caucus, I wrote that we might never discover where that word came from (see the posts for January 24 and January 31, 2024). She asked me whether more such intractable English words exist, and I promised to deal with her question in this blog. Here is my answer. People usually want to know “where such and such a word came from.” They seldom realize how tricky their question is. The answer should be: “How far do you want to go?”

We have two “actors” (sound and meaning) and would like to discover why just this combination of vowels and consonants evokes the familiar image. Why should b-i-g refer to a certain size, while p-i-g designates a familiar animal? Regrettably, with the means at our disposal, most of such questions can seldom be answered. The only words whose origin is clear are sound-imitating ones (the likes of bow-wow, oink-oink, beep-beep, puff, and hush) and a few baby words (mamma, papa, daddy, and so forth). When it comes to other words, be it house, man, red, go, yet, if, on, or any other, we at best (at best!) know their history in written documents and can state that, for example, fire and water are ancient nouns with numerous cognates, while the more recent boy and girl are of “contested origin” (which means that numerous language historians have tried to solve the riddle, but no one has been fully successful). Or we learn from our dictionaries that ruse and rose are borrowings, which means that their history is hidden in some foreign language.

A big pig: a simple image but two etymological riddles. Hairy pig with piglets on farm. By Brett Sayles via Pexels.

A big pig: a simple image but two etymological riddles. Hairy pig with piglets on farm. By Brett Sayles via Pexels.Here then is the conclusion: in most cases, an etymologist can go only so far. Consequently, we deal with many degrees of intractability. This conclusion should not come as a revelation: the “final” origin of hardly anything in the world is “known.” Caucus is so intriguing because the word emerged almost “the day before yesterday,” and we still have trouble deciding who and under what circumstances coined it. The same holds for most of slang.

Noah Webster was a passionate etymologist, but few of his bizarre word derivations outlived him. Noah Webster pre-1843 by James Herring. Public domain via Picryl.

Noah Webster was a passionate etymologist, but few of his bizarre word derivations outlived him. Noah Webster pre-1843 by James Herring. Public domain via Picryl. In a comment on the latest post, a reader suggested that the best authority on etymology is Webster’s dictionary. The information posted by Merriam-Webster online is indeed generous and reliable. But as far as I can understand, the only dictionary that has a permanent group of etymologists is the OED. Other “thick” dictionaries, now defunct, had only consultants, none of whom could assess the information in hundreds of articles dealing with every word. Even finding such articles in at least a dozen languages is a major problem, now partially mitigated by my voluminous Bibliography of English Etymology. It is characteristic but not surprising that all editors missed Ernst’s important notes on caucus (both were discussed in detail in the previous post). We need a detailed dictionary of English etymology, with all the literature on every word listed, summarized, however briefly, and evaluated. Such dictionaries exist for several languages, but I have doubts that an English dictionary of this type will ever appear: no institutions train etymologists, and agencies are not in a hurry to fund the effort.

Spelling reformI received a letter in which our correspondent pointed out that society is no longer interested in spelling reform, calendar reform, number-base reform, and their likes. What, he wonders, is my take on this phenomenon? I can say something only about spelling. Roughly between the 1870s and the First World War, it seemed that the incredibly erratic English spelling would soon be reformed. The most influential intellectuals, from Walter W. Skeat to George Bernard Shaw, supported the idea. The main obstacles are well-known. Those who can spell well are reluctant to forfeit their hard-won knowledge. They don’t want enough to become inuf or enuf and resent the idea of exceed and quick turning into ekseed and kwik. And the horror of gnaw becoming naw! All the arguments for and against reforming English spelling have been rehearsed more than once. Only one argument remains, but it outweighs all the others. Modern English spelling is so incredibly hard to learn that the effort is not worth the trouble, money, and anguish. The result is no secret: for instance, our contemporaries are unable to spell occurrence (the universal form is ocurence) and even after a semester-long course in German folklore and multiple reminders that there were two brothers write Grimm’s Tales. Long live the spellchecker!

Knight at the crossroads, or an etymologist pondering three dangerous solutions. Knight at the crossroads (1878). Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain via Picryl.

Knight at the crossroads, or an etymologist pondering three dangerous solutions. Knight at the crossroads (1878). Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain via Picryl.But this is not the worst part of it. Despite a catastrophic decline in our education (the greatest books remain unread, the most famous events in history are news to the young, and so forth), native speakers reach some level of (il)literacy, but today, English is the main international language, and for foreigners it costs a fortune and causes great psychological pain to cross the barrier between millions of people and the written/printed text in English. Why then don’t we witness universal enthusiasm for the Reform? Of course, I have no explanation, but perhaps the reason is that since 1914, the world has not had a single quiet day: there have always been catastrophes or periods of spasmodic recovery, and spelling receded into the background. Also, the last seventy years or so have witnessed such a triumph of low culture, with the intellectuals supporting and celebrating it, that a minor thing like spelling disappeared from the public view. Yet the English Spelling Society is still active and works on good projects. Not all is lost.

Confusing similaritiesThe author of another letter wonders why so many words designating opposite concepts sound alike. Most of his examples owe their existence to chance. For instance, LAD (a boy) and LADY (a woman) or TOP (with its reference to height) and DEEP. The same holds for GIRL (a late word in English) and CARL (“churl”), which has existed in the language for ages and whose origin is unclear. The relation between BLACK and BLEACH does pose some problems, but one thing is certain: Old English had a word with a short vowel (blæc, blac-), the ancestor of black, and another word with a long one (ā), that is, blāc, the root of Modern English bleach. No one knows why those adjectives arose in such close proximity. English speakers traveling in Italy often think that caldo means “cold,” but it means “hot.” CALDO and COLD go back to two different roots. A more interesting problem is covered by the term enantiosemy, a situation in which a word refers to two opposite concepts. Such is, for instance, Latin altus “high” and “deep.” You look up and observe height; you look down and see depth.

The origin of “lopsided”English has the verbs lob ‘’to lump,” lop “to cut off branches, limbs” and lop “to hang loosely, droop.” The first component of lop-sided and lop-eared obviously refers to the idea of hanging loosely, but cutting is close by. The verb lob ~ lop is probably of Low German or Dutch origin, a so-called “popular word.” Hence the variation of final b~ p. Monosyllables like lap, lop, and lap are often expressive. Lop–sided surfaced in English only in the early eighteenth century.

Feature image: Cpl. Emily E. Vandyke helps teach children to say. Defense Visual Information Distribution Service. Public domain via Picryl.

Exploring different facets of love in eight history books [reading list]

Exploring different facets of love in eight history books [reading list]

As Valentine’s Day approaches, we’ve curated a special reading list that considers the complexities of love, society, and human interaction. These recent history titles promise to captivate heart and mind and offer a journey through time that goes beyond roses and chocolates. From a powerful Roman couple to courtship in Georgian England, this Valentine’s Day inspired reading list is sure to ignite your intellectual ardor.

1. Love and the Working Class: The Inner Worlds of Nineteenth Century Americans

Love and the Working Class is a unique look at the emotions of hard-living, nineteenth-century Americans who were often on the cusp of literacy. These laboring folk highly valued letters and, however difficult it was, wrote to stay connected to those they loved. Using letters written to parents, siblings, husbands, wives, friends, and potential mates between 1830 and 1880, Karen Lystra identifies the shared conceptions of love and practices of courtship and marriage within a racially diverse population of free working-class people born in America.

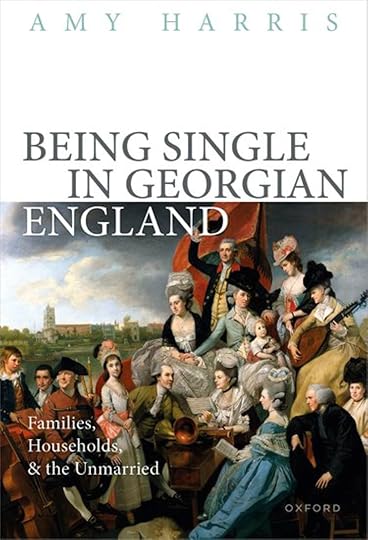

2. Being Single in Georgian England: Families, Households, and the UnmarriedBuy Love and the Working Class: The Inner Worlds of Nineteenth Century Americans by Karen Lystra

Using a micro-historical approach, Amy Harris covers three generations of the famous musical and abolitionist Sharp family. The Sharps’ exceptional closeness and good humor consistently shines through as their experiences reveal how eighteenth-century families navigated gender and age hierarchies, marital choices, and household governance. The importance of childhood relationships and the life-long nature of siblinghood stand out as central aspects of Sharp family life, no matter their marital status.

3. The Game of Love in Georgian England: Courtship, Emotions, and Material CultureBuy Being Single in Georgian England Families, Households, and the Unmarried by Amy Harris

If you want to find out more about love in Georgian England, Sally Holoway’s The Game of Love in Georgian England explores courtship as a decisive moment in a person’s life cycle; imagined as a tactical game, an invigorating sport, and a perilous journey across a turbulent sea. The book brings to life the emotional experience of courtship using the words and objects selected by men and women to navigate this potentially fraught process.

4. The Emergence of a Hero: A Tale of Romantic Love in Russia around 1800Buy The Game of Love in Georgian England: Courtship, Emotions, and Material Culture by Sally Holloway

Dedicated to the history of Russian emotional culture of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, The Emergence of a Hero centers around the life and death of Andrei Turgenev (1781-1803), the author of a confessional diary, a gifted poet, and an early Russian Romantic who failed to live up to the principles and models he cherished.

5. Sex in an Old Regime City: Young Workers and Intimacy in France, 1660-1789Buy The Emergence of a Hero: A Tale of Romantic Love in Russia around 1800 by Andrei Zorin, translated Leo Shtutin

Our ideas about the long histories of young couples’ relationships and women’s efforts to manage their reproductive health are often premised on the notion of a powerful sexual double standard. Here, Julie Hardwick offers a major reframing of the history of young people’s intimacy. Based on legal records from the city of Lyon, she uncovers the relationships of young workers before marriage and after pregnancy occurred, even if marriage did not follow, and finds that communities treated these occurrences without stigmatizing or moralizing.

6. Love at Last Sight: Dating, Intimacy, and Risk in Turn-of-the-Century Berlin by Tyler CarringtonBuy Sex in an Old Regime City: Young Workers and Intimacy in France, 1660-1789 by Julie Hardwick

Love at Last Sight examines the risk associated with modern approaches to dating and finding love in the turn-of-the-century metropolis. Using newspapers, diaries, police records, and court cases, it reveals the strangers, swindlers, and traditional middle-class values that threatened single people looking for intimacy in new ways. For most men and women, using modern technologies to seek romance—making an acquaintance on the street, pursuing a missed connection from a streetcar, or paying for a matchmaking service or personal ad—meant putting one’s livelihood, respectability, and life on the line.

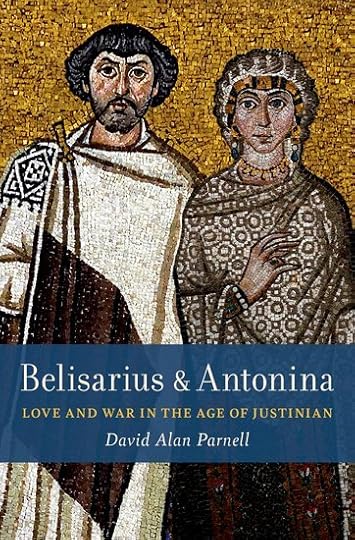

7. Belisarius & Antonina: Love and War in the Age of JustinianBuy Love at Last Sight: Dating, Intimacy, and Risk in Turn-of-the-Century Berlin by Tyler Carrington

Belisarius and Antonina were titans in the Roman world some 1,500 years ago. Belisarius was the most well-known general of his age, victor over the Persians, conqueror of the Vandals and the Goths, and as if this were not enough, wealthy beyond imagination. His wife, Antonina, made a name for herself by traveling with Belisarius on his military campaigns, deposing a pope, and scheming to disgrace important Roman officials. Together, the pair were extremely influential, and arguably wielded more power in the late Roman world than anyone except the emperor Justinian and empress Theodora themselves.

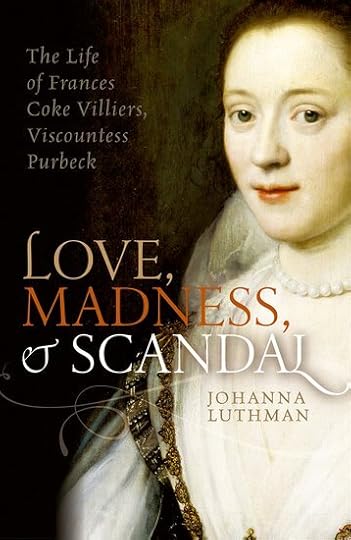

8. Love, Madness, and Scandal: The Life of Frances Coke Villiers, Viscountess PurbeckBuy Belisarius & Antonina: Love and War in the Age of Justinian by David Alan Parnell

The high society of Stuart England found Frances Coke Villiers, Viscountess Purbeck (1602-1645) an exasperating woman. She lived at a time when women were expected to be obedient, silent, and chaste, but Frances displayed none of these qualities. On one level a thrilling tale of love and sex, kidnapping and elopement, the life of Frances Coke Villiers is also the story of an exceptional woman, whose personal experiences intertwined with the court politics and religious disputes of a tumultuous and crucially formative period in English history.

Buy Love, Madness, and Scandal: The Life of Frances Coke Villiers, Viscountess Purbeck by Johanna Luthman

Feature image: Hearts Bokeh Photography by Rachel Walker. Public domain via Unsplash .

February 6, 2024

Françoise de Graffigny and Electronic Enlightenment

Françoise de Graffigny and Electronic Enlightenment

‘Ah mon Dieu, tu n’es plus ici. Voila les pleurs qui reccomensent.’ These melancholic words open the first of 173 newly digitalized letters from the ninth volume of Françoise de Graffigny’s complete correspondence. The recipient of this particular address, which is dated ‘le lundi soir, jour afreux pour moi, 11 mars 1748,’ is Graffigny’s closest friend and confidant, Francois-Antoine Devaux, who had just departed after a lengthy visit to her Parisian residence. We can’t help but feel sorry for the tearful Graffigny as she laments her newfound state of loneliness, not—it must be clarified—that she lacks for company. She bitterly recounts the incessant “protestations d’amitié” of one Pierre Valleré, or “Mr Train” as she dubs him, whom she escapes by locking herself in a wardrobe, key safely stowed away in her pocket. All she wants to do, she confesses to Devaux, is climb into bed and be ‘toute entiere a [sa] douleur’. Cruel as it may sound, Devaux’s departure is in fact a happy event for researchers of Graffigny, as his five-month visit had constituted a five-month hiatus in their correspondence. This hiatus unfortunately overlapped with the publication of Lettres d’une Péruvienne, the work that would make her, according to English Showalter, ‘the world’s most famous living woman writer’ from 1750 until her death in 1758 (2004, p.xv). Of Graffigny’s thoughts and feelings around this significant time we therefore have no known documentation.

Nonetheless, we can’t complain too much. The 173 letters published here span from 11 March 1748 to 25 April 1749, are mostly addressed to Devaux, or “Panpan” as he was affectionately known, and offer us a rich image of Graffigny’s daily life, from her lively social circle to her reading and writing habits. It is an extremely colourful collection, full of inside jokes and peppered with inventive nicknames for friends, foes, and everyone in between. Intrepid readers of Graffigny’s correspondence should be aware of this secret code between the two friends: to name but a few, Marie Thérèse Rodet Geoffrin is “l’Ennemie” or “la Fée sans baguette”, Claude Adrien Helvétius is “le Philosophe,” and, after Graffigny’s disastrous three-month stay at Cirey in 1738-1739, Emilie du Châtelet became “le Monstre” or “la Méchante” forevermore (for more on Graffigny’s doomed stay at the Voltaire residence, see Showalter, 1996). Readers should also anticipate the author’s idiosyncratic turns of phrase: ‘je te remercie de ta compassion pour moi’, she writes to Devaux on 7 December 1748, ‘c’est de la crème sur mon ulcere, je t’assure’. And they can look forward to some gossip too. The publication of Zadig incites quite a bit of speculation, with Graffigny ascribing it to Diderot and refusing to believe it could possibly be Voltaire’s handiwork. She adamantly (and scathingly) writes in another letter: ‘je te dis, moi, que Zadig n’est pas de Voltaire. J’en metrois ma main au feu. […] Pour moi, je n’y ai vu qu’un tas de moralle baroque, lardée de mauvaises avantures sans vraysemblance, sans gout, sans noblesse, enfin une vray rapsaudie.’

These letters also give us a window into Graffigny’s emotional life. She is frequently melancholic, which she tends to describe in terms of noirceur: ‘adieu, bonsoir, je te noircirois trop si je continuous, car je suis trop noire pour paroitre blanche’. Her mood is often influenced by her productivity and creative output on a given day, which is rather unfortunate for a woman who is constantly surrounded by people: ‘Bonsoir. Voila trois fois que je prends mon ecritoire depuis ce matin sans pouvoir seulement ecrire la datte de ma lettre, tant j’ai été assassinée de monde’. On one occasion, her desperation to withdraw in order to work elicits an interesting comparison with her famous protagonist: ‘d’alieurs un marché que j’ai fait avec mes acolites de me laisser seule depuis six jusqu’a huit me soulage beaucoup, ne fusse que pour ne pas avoir leurs regards a suporter. Je suis un peu comme Zilia.’ However, readers shouldn’t expect too much discussion of the recently published Lettres d’une Péruvienne, except for some references to its anonymous sequel, Lettres d’Aza, which Graffigny treats with a general tone of indifference, dismissing its author as ‘un sot qui a de l’esprit’.

Ultimately, what truly emerges in these letters is the incredible intimacy between Devaux and Graffigny. Whether she is baring her soul or simply providing an update on her stomach health, there is seemingly no topic that cannot be broached. The frequency of their correspondence means that one throwaway observation or anecdote could evolve into a conversation across multiple letters, the impracticality of which does not go unremarked: ‘reprenons notre causerie. Mon Dieu, cela seroit bien plus court et bien plus doux s’il ne failoit que dire: « Simonet, dis a Panpan de dessendre. »’ Devaux need not be physically present in order to be privy to the daily minutiae of Graffigny’s existence. ‘Voila l’eau qui chaufe pour le thé’, she digresses in one letter, and concludes another: ‘bonsoir, car j’ai faim. Je vais manger deux oeuf’.

As modern readers, we can imagine mentioning these small, seemingly insignificant details offhand to a friend in a phone call, but they don’t really seem worth noting in a handwritten letter. It is these details, however, which imbue this correspondence—and its author—with a sense of authenticity and aliveness. Françoise de Graffigny’s revival in scholarship is a fairly recent one: after falling into obscurity in the nineteenth century, her Lettres d’une Péruvienne only began to be published again in France in 1983 (Showalter, 1996, p.30). The publication of the ninth volume of her correspondence by the Electronic Enlightenment is another valuable step towards keeping her voice alive, and is also a reminder of the vitalness of the digital humanities for scholarship.

A version of this blog post was first published on Electronic Enlightenment.

February 5, 2024

Election plays and the culture of elections and electioneering in the days of Dunny-on-the-Wold

Election plays and the culture of elections and electioneering in the days of Dunny-on-the-Wold

England’s pre-Reform elections are memorably satirized in the historical sitcom, Blackadder the Third. Also glancing at late 1980s politics, the series begins with the rigged by-election for a fictional rotten borough—Dunny-on-the-Wold—taking centre stage. The first episode of the TV series based on the Horrible Histories books by Terry Deary contributes to the same satirical and comedic tradition: the sketch ‘How to Vote in a Georgian Election’ mocks the corrupt aspects, inequalities, and elite control of pre-democratic politics, for example, by stressing the importance of voting for the lord of the manor’s son: ‘You have to, there are no other candidates’.

In fact, these satirical takes on the long eighteenth century on the small screen have much in common with the drama of the period itself—as well as with related forms, such as Hogarth’s famous series of paintings, and associated prints, on the ‘humours’ of an election. Across the eighteenth- and early nineteenth centuries, and across the country, a rich and varied genre of election plays—that is, plays about contemporary elections and electioneering—presented society with images of itself, displaying key aspects of the political process, corrupt practices, abuses endemic to the electoral system, and acts of principled resistance, through the entertaining lens of particular dramatic performances and conventions.

Although potentially subject to forms of censorship, these daringly topical plays nevertheless circulated in print and manuscript, and were staged, in different parts of the country, before and after the Licensing Act of 1737 (which stipulated that new plays, and new material added to old plays, should be submitted for official examination in advance of performance). Election plays were also adapted—for instance, as printed plates for a toy theatre—and disseminated as extracts: for example, ballads featured in these plays circulated separately and in song books. The genre includes the work of canonical authors such as Shakespeare, as well as lesser-known playwrights and anonymous and now lost pieces.

One example is Henry Fielding’s self-consciously ‘libellous’, commercially canny ‘rehearsal play’, Pasquin, A Dramatick Satire on the Times (1736). The play presents an eighteenth-century precursor to the metatheatrical The Play That Goes Wrong plays of today, a kind of Election Play That Goes Wrong. Set in the theatre itself, it features the rehearsal of a ludicrously bad comedy about an election, with commentary provided by the playwright, Trapwit, and rival dramatist, Fustian, as well as the critic Sneer-well and other stage personnel.

Through the farcical dramatization of electoral bribery in Trapwit’s ‘senseless’ comedy—at one point, Trapwit directs the actors playing the voters to ‘range your selves in a Line’, and those playing the candidates to ‘come to one End, and Bribe away with Right and Left’—Fielding satirically suggests the similarities, as well as differences, between this parodic, exaggerated representation and real life. Fustian asks, ‘Is this Wit, Mr. Trapwit?’, to which Trapwit responds: ‘Yes, Sir, it is Wit; and such Wit as will run all over the Kingdom’. The play was a hit at the Haymarket in the spring of 1736, due, in no small part, to the appeal of its electoral comedy.

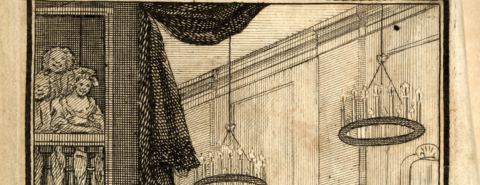

Fielding’s play also circulated widely in print. In 1737, there appeared what claimed to be a tenth edition, printed by Edmund Cook. The edition had a smaller, more portable duodecimo format than previous Pasquin editions. It also attracted purchasers by prefacing Fielding’s play-text with a frontispiece portraying a scene from the rehearsal of Trapwit’s election comedy, further underscoring the popularity of this part of the play.

Pasquin. A Dramatick Satire on the Times.

Pasquin. A Dramatick Satire on the Times.Although it is not a straightforwardly accurate representation, the frontispiece brings into focus some of the ways that election plays afforded voters and non-voters opportunities for political engagement and expression, at a time when the ability to vote was restricted. For example, as the copy in the Senate House Library Malcolm Morley Collection shows, the illustration highlights the presence of unenfranchised women in Fielding’s theatre audiences (members of whom have a prominent place on the left-hand side of the frontispiece); women could also read, hear readings from, and view the frontispiece to, the printed edition itself. (In writing his election plays Pasquin and Don Quixote in England (1734), Fielding was, moreover, following the example of Susanna Centlivre, whose influential works include the seminal election farce, The Gotham Election (1715).)

Again, the frontispiece comments on the role of actresses as active agents in shaping Fielding’s electoral comedy; the illustration represents the satirical onstage encounter between Miss Mayoress, a government supporter, and Miss Stitch, a supporter of the opposition, who, in Trapwit’s comedy, is susceptible to the bribe of a hand fan. In addition, the frontispiece points to the dynamic interplay between literary and visual satire key to the era’s electoral culture, apparent in the fruitful exchanges between numerous writers and artists, including Fielding, Hogarth, and Frederick Pilon.

Election plays like Pasquin had both immediate and wider, long-lasting implications for literature and political culture. Such plays reveal important interconnections between commercial theatre, the market for entertaining print, and the expansion of an audience for representations of contemporary political life in the long eighteenth century. This is also suggested by the way that other forms of electoral culture tapped into the popularity and appeal of dramatic forms (including election plays). These forms include partisan electioneering materials, such as mock playbills attacking particular candidates, which could also be sold as part of printed election miscellanies—collections of texts generated by particular contests—further highlighting connections between the commercialization of literature and politics.

At the same time as election plays energized contemporary drama, they also had an impact on political life. In a period when many seats were not contested (that is, the candidate(s) for a particular constituency faced no formal opposition) and many could not vote, election plays fuelled political engagement and the formation of opinion about elections across the social spectrum and across the country in terms of their diverse authors, audiences, and performers. These plays had the potential to popularize ‘libellous’ views, promote electoral partisanship, and encourage calls for reform. Interacting and overlapping with other forms—including ballads, prints, and novels—election plays helped to create an active culture of elections and electioneering in the age of ‘Dunny-on-the-Wold’ itself.

Today, political culture continues to draw upon and rework well-known cultural forms, including entertaining dramatic forms, at a time when many people also engage with elections and electioneering without voting, for example, by sharing parodic online memes. Campaigning for the UK general election held in December 2019 saw the Labour and Conservative parties circulate adaptations of the well-known seasonal romcom Love Actually (2003) on social media, reimagining the romantic declaration made by Andrew Lincoln’s character Mark to Keira Knightley’s Juliet via cue cards as an act of doorstep canvassing.

As forms of political communication continue to draw upon dramatic culture, elections remain occasions for satirical and comedic creativity. During campaigning for the 2015 general election, the comedy series Ballot Monkeys reworked the classic satirical theme of ‘canvassing for votes’ by focusing on rival party ‘battle’ buses. The election play itself remains alive, and ready for reinvention. December 2019 also saw the topical updating of James Graham’s election play, The Vote, previously staged and televised on election night in 2015. The next UK general election, currently expected to take place in 2024, may well see Graham’s play revived and adapted to the times once again, as earlier election plays were revived, adapted, and repurposed to suit different political and cultural occasions. If a variety of dramatic forms still feature in today’s political and cultural landscape, election plays of the long eighteenth century offer us a window onto the drama and political life of the past, and the vital exchanges between them.

Featured image credit: Frontispiece to Henry Fielding, Pasquin. A Dramatick Satire on the Times, ‘Tenth Edition’ (London, 1737) © University of London, Senate House Library, Malcolm Morley Collection, M.M.C. 2841

February 4, 2024

How synonymy rolls

If you look up the synonym of big, you are likely to find words like large, huge, immense, colossal, enormous, and ginormous, among others. Some of these will cause you to raise an eyebrow because they are bigger than big: something can be big, but not huge or enormous. With a little cogitation and comparison, you’ll probably settle on big and large as the best pair of synonyms. Both can be defined as “of considerable size, extent, or intensity.” But do they really have the same meaning?

That depends on the meaning of “meaning.” Big and large are not always interchangeable: we talk about a “big idea” but not a “large idea,” and you can talk about a “large amount” of something but are less likely to say a “big amount.” You can make a “big deal” out of something trivial, but probably not a “large deal.” And if you need a twenty-ounce coffee, you’ll likely ask for a “large coffee,” not a “big coffee.” Big tends to issues and large to amounts.

While there are some absolute synonyms (think groundhog and woodchuck), the vast majority are really near-synonyms, with the same meaning in some uses or senses but not fully overlapping in all senses.

Some word pairs wear their difference on their morphological sleeves. Take electric and electrical, for example. They can sometimes be used alike, as in when modifying appliance or current. But more often than not the two words spilt the terrain, with electric cars, electric toothbrushes, electric companies, and electric guitars, but electrical grids, electrical engineers, electrical storms, electrical tape, and so on. The difference seems to be that devices that use electricity are electric while things that produce or control electricity are electrical, though there is more to it (as the phrase electric personality suggests).

What’s more there are phrases which seem to be synonymous but which may have small differences such as the compound subordinators as if and as though. We use these to make comparisons by proposing imaginary, hypothetical, or possible situations.

He acted as if he owned the place.

It looks as though you’ve not done this before.

They moved toward the door as if to leave.

Bryan Garner suggests that “Attempts to distinguish between these idioms have proved futile” and that writers should let euphony be their guide—in other words, play it by ear. But he adds this teaser: “One plausible distinction is that as if often suggests the more hypothetical proposition when cast in the subjunctive <as if he were a god>. … By contrast, as though suggests a more plausible suggestion <it looks as though it might rain>.” In other words, imaginary situations may tend toward as if (“He stood silently, as if he were made of stone.”) while possible situations may tend toward as though (“He fidgeted as though he was high on something.”) To me, as if does sound more bookish and subjunctive. And the subjunctive as if it were is the most common usage in Google n-grams, a tool that analyzes the contents of Google books.

Notice too that the word like is a partial synonym for as if and as though, introducing nouns and clauses after such verbs as seem, feel, sound, act, and so on. But the subjunctive is decidedly odd. You can say “He acted as if he were a god, but not “He acted like he were a god.” Ugh.

Another pair of curious compounds is each other and one another. These convey what is known as the reciprocal relation, as in “The speakers shook hands with each other.” Each other is more common than one another and for many speakers (such as me) the only difference is that one another feels more formal or bookish. Some old or old-minded grammar books promulgate a fussy rule about each other being used for two and one another for more than two. That so-called rule is a bit of nonsense that attempts to force a grammatical distinction into these logical synonyms. The legendary grammarian Henry Fowler put it this way in his 1926 A Dictionary of Modern English Usage: the “differentiation is neither of present utility nor based on historical usage.”

Synonymy is tricky and imperfect. So before you take words or phrases as synonymous, think about it and see if they are really interchangeable. Which you use can make a big—or maybe a large—difference.

February 2, 2024

Scientific writing as a research skill

Scientific writing as a research skill

Scientific papers are often hard to read, even for specialists that work in the area. This matters because potential readers will often give up and do something else instead. And that means the paper will have less impact.

The fact that many scientific papers are hard to read is surprising. Scientists want others to read their papers—they don’t try to make them difficult to get through! So why does this problem arise? And how can we fix it?

The curse of knowledgeOne problem is that scientists are incredibly knowledgeable about every detail of their research: from the studies that inspired them, to their methods and results, to the implications of those results. This means that they’re about as far away as it’s possible to be from someone who is new to the topic, so often they’re the worst person in the world to write up their study.

This problem is so common that it has even been given a name in psychology literature: the ‘curse of knowledge’. The curse means that people tend to unwittingly assume that others have the necessary background to understand what they are saying. Put simply, it’s easy for a scientist to miss out crucial points or steps because they’ve forgotten how important those things are for understanding their work.

Another aspect of the ‘curse of knowledge’ is that scientists tend to write like scientists. They use jargon, technical abbreviations, and phrases that they would never use in everyday speech. This ‘science speak’ usually makes things harder, not easier, for potential readers. This is particularly true with readers of interdisciplinary research, or with readers who are new to the specific subject area, who are less likely to know the meaning behind the jargon.

So how can we fix the writing problems that come from science speak and the curse of knowledge?

Writing as a research skillThe first step is that we need to acknowledge that writing is a skill that needs to be learnt, just like any other aspect of scientific research. Indeed, good writing can require a much longer learning period than many familiar research techniques. Once you have learnt how to pipette, you can do it, but writing is something that you can keep improving throughout your career.

Writing can be learnt in multiple ways. Courses can be run, usually for undergraduate or graduate students. But learning to write needs practise and motivation, and these courses are often run before the students need to write up their own research, An alternative is guide

books, that provide advice and tips, that writers can read and apply as they go along, as they produce the different sections of their paper. But what exactly needs to be learnt?

The readerThe next step is to pause and imagine potential readers. A potential reader is likely to be time-limited, stressed, and easily bored. They have a million other things to do and will take any excuse to give up on reading your paper. They might be a PhD student trying to get to grips with their subject, or a professor who doesn’t really have time to read papers anymore.

They key point is that they don’t have to read your paper—it’s the writer’s job to make them want to. This leads to a fundamental principle of scientific writing: the reader must come first. It is the job of the writer to help the reader understand the content of their paper by making things as clear and straightforward as possible.

Guiding principlesUnfortunately, putting the reader first does not always come naturally, and can require a change of thinking on the part of the writer. Luckily there are a few general principles that help with this:

Keep it Simple. Use simple clear writing to make it as easy as possible for the reader.Assume nothing. A paper is more likely to be hard to read because it assumed too much, rather than because it was dumbed down too much.Keep it to essentials. A more focused paper will better at both getting the major points across and keeping the attention of a time-stressed reader.Tell your story. Good scientific writing tells a story. It tells the reader why the topic you have chosen is important, what you found out, and why that matters.The beauty is in the detailsThe above advice might still seem a bit vague, but it’s just an overview. In our recent book, Scientific Writing Made Easy, we build upon these guiding principles to provide a toolkit for writing the different parts of a scientific paper. We provide both a structure for each section, and detailed tips for how to fill that structure out. We make writing easier and less scary.

Our toolkit can be applied to different types of paper across the life, human, and natural sciences. While there are important differences, a lot of the same principles can be applied whether someone is writing up a laboratory experiment, a mathematical model, or an observational field study.

Learn more about Scientific Writing Made Easy with this review from the Stated Clearly YouTube channel.

January 31, 2024

The origin of the word caucus: conclusion

The origin of the word caucus: conclusion

Last week, I mentioned three etymologies of caucus: from caucus, Latin for “cup”; from an Algonquin phrase, and from calker’s or caulkers’. The derivation from caucus seems improbable to me, and the derivation from Algonquin unlikely (despite its support by many noted scholars). Calker is still up in the air. I am grateful for the two comments on the previous post. Both anticipated part of what I meant to include in today’s short essay. I do have two old messages from Dr. Stefan Goranson (initially left for dessert), and I hoped to finish this post with a flourish (a quotation from Alice in Wonderland). The remarks by our correspondents stole my thunder, but I’ll produce the intended rumblings anyway.

[image error]here","created_timestamp":"0","copyright":"","focal_length":"0","iso":"0","shutter_speed":"0","title":"","orientation":"1"}" data-image-title="image-from-rawpixel-id-6440291-jpeg" data-image-description="" data-image-caption="Flying stork with baby drawing, vintage bird illustration. Free public domain CC0 image.

More:

View public domain image source here

" data-medium-file="https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa..." data-large-file="https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa..." src="https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa..." alt="" class="wp-image-149998" style="width:284px;height:auto" srcset="https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa... 2560w, https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa... 180w, https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa... 194w, https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa... 120w, https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa... 768w, https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa... 1536w, https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa... 2048w, https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa... 128w, https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa... 184w, https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa... 31w, https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa... 50w" sizes="(max-width: 2560px) 100vw, 2560px" />Stork with a baby. CC0 via rawpixel.The hypothesis that will occupy us below is not unknown. Even the second edition of The Century Dictionary mentions it in a kind of postscript, but I have never seen it discussed. The main point is that in British English, calker and corker are homophones (compare also such words as stalk and stork). According to C. W. Ernst, the same pronunciation prevailed in Boston at the end of the nineteenth century (and by the same token a century earlier). C. W. Ernst, I am sure, is (1845-1919), the author of, among other works, the book Constitutional History of Boston. He contributed two articles on caucus to the British weekly Notes and Queries, 8th Series, IX, 1896, pp. 126 and 510-11: February 15 and June 27. The suggestions by such a specialist should not be neglected. With regard to John Adams’s diary (see the previous post), Ernst wrote: “But Adams was not a Bostonian and his allusion to the ‘caucus club’ is suspicious. Political clubs did not exist in the Boston of 1763; and the combination ‘caucus club’ is contrary to reason as well as history.” At that time, Ernst continues, there had been a great fire in Boston [I could not find its date], and an appeal was made to the legislature to get wider streets. The appeal was sustained by merchants and opposed by mechanics. In derision, the mechanics called themselves the members of the old and true Corcas and the merchants the new and grand Corcas. Enter corcas or Corcas.

The mechanics were defeated. Obviously, it is not the legal battle that interests us here but the odd word Corcas. Ernst admitted that the word was new. He wrote: “About that time corks and bottling came to be common in Boston. The slang phrase ‘corker’ is still common in Boston. It would have been reasonable had the mechanics of 1760 called the merchants ‘corkers’, first in ridicule, and after election in good faith.” Corker “an unanswerable argument” and especially “doozie” is still very much alive in American English. Though in my opinion, Ernst’s reconstruction deserves attention, many details in the transition from corkers too caucus remain obscure, and Ernst must have been aware of this circumstance, as follows from his later publication. Reference to the old corcas, he pointed out, showed that in 1760 the term was not new or unfamiliar.

In 1741, the caulkers (!) of Boston organized the first trade union in New England. Much turmoil followed. The union “became the talk of the time and the etymon for a cast-iron agreement. By 1760, as appears from the Boston Gazette, the agreement of electors in selecting candidates for public office was known as caucus (!) action.” I don’t know whether Ernst solved the riddle, but I believe that with his explanation we are at least partly out of the dark. Caucus seems to have arisen in the interplay of calkers, corkers, and the mysterious Corcas. The r-less pronunciation that prevailed in Boston was a factor in the word’s history.

The rest looks like an anticlimax. In 1943, a note was found among the papers of no less a figure than John Pickering (see again the previous post) to the effect that caucus consists of the initials of the names of six: Cooper (Wm.), Adams, Urann (Joyce, Jr.), Coulson, Urann [again!], and Symmes (American Speech 18, 1943, P. 130). This CAUCUS must have been a joke in imitation of CABAL under King Charles II (a private group of high councilors between 1667 and 1672: Clifford, Arlington, Buckingham, Ashley, and Lauderdale). The list only proves that the word caucus had already been known.

Alice and a caucus race. Illustration from the Nursery Alice. Public domain via Picryl.

Alice and a caucus race. Illustration from the Nursery Alice. Public domain via Picryl.In June 2015, Stephen Goranson posted two notes on the list serve of the American Dialect Society. He found “an impartial account of the conduct of the Corkass” [sic] going back to 1763. We read: “It may be expected that I should give the etymology of the word CORCASS, and some accounts of the Society, but as they keep no records, and their oral accounts are so various and dark, it is needless to mention them….” A classic teaser. Apparently, not only Ernst noticed an early Bostonian confusion of caucus and corcas(s). In the second note, Goranson quotes Samuel L. Knapp’s Biographical Sketches of Eminent Lawyers…. (1821): “The frequent political meetings at that house have by some… been supposed to be the origin of the caucus—a corruption of “Cooke’s House.”” Goranson also mentions the derivation of caucus from concourse. Etymological literature is full of such unsubstantiated guesses.

Enter Alice from Alice in Wonderland. The caucus race is described in Chapter Three. The satire is unforgettable. There is really no race, because all the participants run in different directions and begin running when they like, so that it is not easy to know at what time the race comes to an end. The question “But who has won?” received the unforgettable answer: “Everybody has won, and all must have prizes.” Alice is called upon to distribute prizes but is entitled to get one too. She produces a thimble from her pocket, gives it to the Dodo, and the Dodo gives it back to Alice, a procedure that seems ridiculous even to a little girl. Political processes do look ludicrous to outsiders and even to many insiders. Alice in Wonderland was published in 1865. By that time, the word caucus and the phrase caucus race had become quite familiar in England.

Ariadne’s thread. The golden fleece and the heroes who lived before Achilles. CC0. Via Flickr.

Ariadne’s thread. The golden fleece and the heroes who lived before Achilles. CC0. Via Flickr.This is the end of my story. Whether, to paraphrase Dickens, it will convert into a dazzling brilliance that obscurity in which the early history of the word caucus would appear to be involved, the future will show. The main thing about solving etymological riddles is to know everything everybody has ever said about the troublesome word. Some ideas die without issue, while some others, even if not fully satisfactory, may lead the investigator to an important discovery. Ariadne’s thread is a useful tool. The picture is now before us, and anybody can pick up where I have left off.

Feature image: Beacon Street and the Common by . Boston Pictorial Archive. CC0 via Digital Commonwealth.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers