Oxford University Press's Blog, page 36

January 12, 2024

Which imaginary book should you read?

Which imaginary book should you read?

Are you looking to broaden your book list? Why not try a book that doesn’t exist? Literature is full of fictional books – books which exist only in other books.

Take this quiz to find out which fictional book would be a perfect next read for you. Be prepared for disappointment though – none of our recommendations have ever been written or published. At least, not in the real world!

Personalities 'Anything out of Anything' Now It Can Be Told The Red Book of Westmarch ‘The Jealous Rival; or in Death Not Divided'If you’d like to see more fun activities, as well as keep up to date with Oxford University Press products and offers, why not sign up to receive our email communications?

Feature image by Peter Herrman via Unsplash.

January 11, 2024

How can business leaders add value with intuition in the age of AI? [Long Read]

How can business leaders add value with intuition in the age of AI? [Long Read]

In a speech to the Economic Club of Washington in 2018, Jeff Bezos described how Amazon made sense of the challenge of if and how to design and implement a loyalty scheme for its customers. This was a highly consequential decision for the business; for some time, Amazon had been searching for an answer to the question: “what would loyalty program for Amazon look like?”

A junior software engineer came up with the idea of fast, free shipping. But a big problem was that shipping is expensive. Also, customers like free shipping, so much so that the big eaters at Amazon’s “buffet” would take advantage by free shipping low-cost items which would not be good for Amazon’s bottom-line. When the Amazon finance team modelled the idea of fast, free shipping the results “didn’t look pretty.” In fact, they were nothing short of “horrifying.”

But Bezos is experienced enough to know that some of his best decisions have been made with “guts… not analysis.” In deciding whether to go with Amazon Prime, the analysts’ data could only take the problem so far towards being solved. Bezos decided to go with his gut. Prime was launched in 2005. It has become one of the world’s most popular subscription services with over 100 million members who spend on average $1400 per year compared to $600 for non-prime members.

As a seasoned executive and experienced entrepreneur Bezos sensed that the Prime idea could work. And in his speech he reminded his audience that “if you can make a decision with analysis, you should do so. But it turns out in life that your most important decisions are always made with instinct and intuition, taste, heart.”

The launch of Amazon Prime is a prime example of a CEO’s informed and intelligent use of intuition paying off in decision-making under uncertainty (where outcomes are unknown and their likelihood of occurrence cannot be estimated) rather than under risk (where outcomes are known and probabilities can be estimated). The customer loyalty problem for Amazon was uncertain because probabilities and consequences could not be known at the time. No amount of analysis could reduce the fast, free shipping solution to the odds of success or failure.

Under these uncertain circumstances Bezos chose to go with this gut. This is not an uncommon CEO predicament or response. In business, decision-makers often have to act “instinctively” even though they have no way of knowing what the outcome is likely to be. The world is becoming more, not less uncertain, and “radical uncertainty” seems to have become the norm for strategic decision-making both in business and in politics. The informed and intelligent use of intuition on the part of those who have the nous and experience to be able to go with their gut is one way forward.

Human intuition meets AITurning to the uncertainties posed by artificial intelligence and winding the clock back to over half-a-century ago, the psychologist Paul Meehl in his book Clinical Versus Statistical Prediction (1954) compared how well the subjective predictions of trained clinicians such as physicians, psychologists, and counsellors fared when compared with predictions based on simple statistical algorithms. To many people’s surprise, Meehl found that experts’ accuracy of prediction, for example trained counsellors’ predictions of college grades, was either matched or exceeded by the algorithm.

The decision-making landscape that Meehl studied all those years ago has been transformed radically by the technological revolutions of the “Information Age” (see Jay Liebowitz, Bursting the Big Data Bubble, 2014). Computers have exceeded immeasurably the human brain’s computational capacity. Big data, data analytics, machine learning, and artificial intelligence (AI) have been described as “the new oil” (see Eugene Sadler-Smith, “Researching Intuition: A Curious Passion” in Bursting the Big Data Bubble, 2014). They have opened-up possibilities for outsourcing to machines many of the tasks that were until recently the exclusive preserve of humans. The influence of AI and machine learning is extending beyond relatively routine and sometimes mundane tasks such as cashiering in supermarkets. AI now figures prominently behind the scenes in things as diverse as social media feeds, the design of smart cars, and on-line advertising. It has extended its reach into complex professional areas such as medical diagnoses, investment banking, business consulting, script writing for advertisements, and management education (see Marcus du Sautoy, The Creativity Code, 2019).

There is nothing new in machines replacing humans: they did so in the mechanisations of the agricultural and industrial revolutions when they replaced dirty and dangerous work; dull work and decision-making work might be next. Daniel Suskind, author of World without Work thinks the current technological revolution is on a scale which is hitherto unheard of. The power with which robots and computers are able to perform tasks at high speed, with high accuracy, at scale using computational capabilities are orders of magnitude greater than those of any human or previous technology. This one reason this revolution is different and is why it has been referred to as nothing less than the “biggest event in human history” by Stuart Russell, founder of the Centre for Human-Compatible Artificial Intelligence at the University of California, Berkeley.

The widespread availability of data, along with cheap, scalable computational power, and rapid and on-going developments of new AI techniques such as machine learning and deep learning have meant that AI has become a powerful tool in business management (see Gijs Overgoor, et al). For example, the financial services industry deals with high-stakes, complex problems involving large numbers of interacting variables. It has developed AI that can be used to identify cybercrime schemes such as money laundering, fraud and ATM hacking. By using complex algorithms, the latest generation of AI can uncover fraudulent activity that is hidden amongst millions of innocent transactions and alert human analysts with easily digestible, traceable, and logged data to help them to decide, using human intuition based on their “feet on the ground” experiences, on whether activity is suspicious or not and take the appropriate action. This is just one example, and there are very few areas of business which are likely to be exempt from AI’s influence. Taking this to its ultimate conclusion Elon Musk said at the recent UK “AI Safety Summit” held at Bletchley Park (where Alan Turing worked as code breaker in World War 2) that: “There will come a point where no job is needed—you can have a job if you want one for personal satisfaction but AI will do everything. It’s both good and bad—one of the challenges in the future will be how do we find meaning in life.”

Creativity and AICreativity is increasingly and vitally important in many aspects of business management. It is perhaps one area in which we might assume that humans will always have the edge. However, creative industries, such as advertising, are using AI for idea generation. The car manufacturer Lexus used IBM’s Watson AI to write the “world’s most intuitive car ad” for a new model, the strap line for which is “The new Lexus ES. Driven by intuition.” The aim was to use a computer to write the ad script for what Lexus claimed to be “the most intuitive car in the world”. To do so Watson was programmed to analyse 15 years-worth of award-winning footage from the prestigious Cannes Lions international award for creativity using its “visual recognition” (which uses deep learning to analyse images of scenes, objects, faces, and other visual content), “tone analyser” (which interprets emotions and communication style in text), and “personality insights” (using data to make inferences about consumers’ personalities) applications. Watson AI helped to “re-write car advertising” by identifying the core elements of award-winning content that was both “emotionally intelligent” and “entertaining.” Watson literally wrote the script outline. It was then used by the creative agency, producers, and directors to build an emotionally gripping advertisement.

Even though the Lexus-IBM collaboration reflects a breakthrough application of AI in the creative industries, IBM’s stated aim is not to attempt to “recreate the human mind but to inspire creativity and free-up time to spend thinking about the creative process.” The question of whether Watson’s advertisement is truly creative in the sense of being both novel and useful is open to question (it was based on rules derived from human works that were judged to be outstandingly creative by human judges at the Cannes festival). In a recent collaborative study between Harvard Business School and Boston Consulting Group, “humans plus AI” has been found to produce superior results compared to “humans without AI” when used to generate ideas by following rules created by humans. However, “creativity makes new rules, rules do not make creativity” (to paraphrase the French composer Claude Debussy). The use of generative AI which is rule-following rather than rule-making is likely to result in “creative” outputs which are homogeneous and which may ultimately fail the test of true creativity, i.e. both novel (in the actual sense of the word) and useful. Human creative intuition on the other hand adds value by:

going beyond conventional design processes and rulesdrawing on human beings’ ability to think outside the box, produce innovative solutionssensing what will or won’t workyielding products and services that stand out in market, capture the attention of consumers, and drive business success.—as based on suggestions offered by Chat GPT in response to the question: “how does creative intuition add value to organizations?”

Emotion intelligence and AIAnother example of area in which fourth generation AI is making in-roads is in the emotional and inter-personal domains. The US-based start-up Luka has developed the artificially intelligent journaling chatbot “Replika” which is designed to encourage people to “open-up and talk about their day.” Whilst Siri and Alexa are an emotionally “cold” digital assistants, Replika is designed to be more like your “best friend.” It injects emotion into conversations and learns from the user’s questions and answers. It’s early days, and despite the hype rigorous research is required to evaluate the claims being made on behalf of such applications.

“The fact that computers are making inroads into areas that were once considered uniquely human is nothing new.”

The fact that computers are making inroads into areas that were once considered uniquely human is nothing new. Perhaps intuition is next. The roots of modern intuition research are in chess, an area of human expertise in which grand masters intuit “the good move straight away.” Nobel laureate and one of the founding figures of AI, Herbert Simon, based his classic definition of intuition (“analyses frozen into habit and the capacity for rapid response through recognition”) on his research into expertise in chess. He estimated that grandmasters have stored of the order of 50,000 “familiar patterns” in their long-term memories, the recognition and recall of which enables them to play chess intuitively at the chess board.

In 1997, the chess establishment was astonished when IBM’s Deep Blue beat Russian chess grand master and world champion Garry Kasparov. Does this mean that IBM’s AI is able to out-intuit a human chess master? Kasparov thinks not. The strategy that Deep Blue used to beat Kasparov was fundamentally different from how another human being might have attempted to do so. Deep Blue did not beat Kasparov by replicating or mimicking his thinking processes, in Kasparov’s own words:

“instead of a computer that thought and played like a chess champion, with human creativity and intuition, they [the ‘AI crowd’] got one that played like a machine, systematically, evaluating 200million chess moves on the chess board per second and winning with brute number-crunching force.”

Nobel laureate in physics, Richard Feynman, commented presciently in 1985 that it will be possible to develop a machine which can surpass nature’s abilities but without imitating nature. If a computer ever becomes capable of out-intuiting a human it is likely that the rules that the computer relies on will be fundamentally different to those used by humans and the mode of reasoning will be very different to that which evolved in the human organism over many hundreds of millennia (see Gerd Gigerenzer, Gut Feelings, 2007).

AI’s limitationsIn spite of the current hype, AI can also be surprisingly ineffective. Significant problems with autonomous driving vehicles have been encountered and are well documented, as in the recent case which came to court in Arizona involving a fatality allegedly caused by an Uber self-driving car. In medical diagnoses, even though the freckle-analysing system developed at Stanford University does not replicate how doctors exercise their intuitive judgement through “gut feel” for skin diseases, it can nonetheless through its prodigious number-crunching power diagnose skin cancer without knowing anything at all about dermatology (see Daniel Susskind, A World Without Work, 2020). But as the eminent computer scientist Stuart Russell remarked, the deep learning that such AI systems rely on can be quite difficult to get right, for example some of the “algorithms that have learned to recognise cancerous skin lesions, turn out to completely fail if you rotate the photograph by 45 degrees [which] doesn’t instil a lot of confidence in this technology.”

Is the balance of how we comprehend situations and take business decisions shifting inexorably away from humans and in favour of machines? Is “artificial intuition” inevitable and will it herald the demise of “human intuition”? If an artificial intuition is realized eventually that can match that of a human, it will be one of the pivotal outcomes of the fourth industrial revolution―perhaps the ultimate form of AI.

Chat GPT appears to be “aware” of its own limitations in this regard. In response to the question “Dear ChatGPT: What happens when you intuit?” it replied:

“As a language model I don’t have the ability to intuit. I am a machine learning based algorithm that is designed to understand and generate human language. I can understand and process information provided to me, but I don’t have the ability to have intuition or feelings.”

More apocalyptically, could the creation of an artificial intuition be the “canary in the coalmine,” signalling the emergence of Vernor Vinge’s “technological singularity” where large computer networks and their users suddenly “wake up” as “superhumanly intelligent entities” as Musk and others are warning of? Could such a development turn out to be a Frankenstein’s monster with unknown but potentially negative, unintended consequences for its makers? The potential and the pitfalls of AI are firmly in the domain of the radically uncertain and identifying the potential outcomes and how to manage them is likely to involve a judicious mix of rational analysis and informed intuition on the part of political and business leaders.

Human intuition, AI, and business management“The potential and the pitfalls of AI are firmly in the domain of the radically uncertain.”

Making any predictions about what computers will or will not be able to do in the future is a hostage to fortune. For the foreseeable future most managers will continue rely on their own rather than a computer’s intuitive judgements when taking both day-to-day and strategic decisions. Therefore, until a viable “artificial intuition” arrives that is capable of out-intuiting a human, the more pressing and practical question is “what value does human intuition add in business?” The technological advancements of the information age have endowed machines with the hard skill of “solving,” which far outstrips this capability in the human mind. The evolved capacities of the intuitive mind have endowed managers with the arguably hard-to-automate, or perhaps even impossible-to-automate, soft skill of “sensing.” This is the essence of human intuition.

Perhaps the answer lies in an “Augmented Intelligence Model (AIM),” which marries gut instinct with data and analytics. Such a model might combine three elements:

human analytical intelligence, which is adept in communicating, diagnosing, evaluating, interpreting, etc.human intuitive intelligence, which is adept in creating, empathising, feeling, judging, relating, sensing, etc.artificial intelligence, which is adept in analysing, correlating, optimising, predicting, recognizing, text-mining, etc.The most interesting spaces in this model are in the overlaps between the three intelligences, for example when human analytical intelligence augments artificial intelligence in a chatbot with human intervention. Similar overlaps exist for human analytical and human intuitive intelligences, and for human intuitive intelligence and artificial intelligence. The most interesting space is where all three overlap and it is here that most value stands to be added by leveraging the combined strengths of human intuitive intelligence, human analytical intelligence, and artificial intelligence in an Augmented Intelligence Model which can drive success.

This blog post is adapted from Chapter 1 of Intuition in Business by Eugene Sadler-Smith.

Feature image by Tara Winstead via Pexels.

January 10, 2024

Back to work: body and etymology

Back to work: body and etymology

While the blog was dormant, two questions came my way, and I decided to answer them at once, rather than putting them on a back burner. Today, I’ll deal with the first question and leave the second for next week.

Since the publication of my recent book Take My Word for It (it deals with the origin of idioms), nearly all the queries I receive turn around buzzwords, cliches, and the like. Journalists are especially often interested in the source of “trending” catchphrases. The first question of 2024 (indeed, not from a journalist) was of the same type: “Can you discuss the etymology of the most popular English idioms dealing with the human body?” Before I can say what I know on the subject, I would like to return to the etymology of the word body, discussed in some detail in my post for October 14, 2015.

The result of that discussion was meager: the origin of body remains unknown, though the ideas on the subject are many. The root of body is of course bod-. Words like bod-, bed, bud, dad, dude, along with bib, bob, dig, dog, bug, bag, bum, bomb, and so forth, are usually expressive or sound-imitative. A few may have emerged as baby words, later repeated and accepted by adults. Once they leave “the nursery,” their origin is forgotten and they become stylistically neutral. However, appeal to expression, sound symbolism, and onomatopoeia is often hard to justify, because numerous nouns and verbs similar to bob, dude, and their likes have a non-expressive origin. That is why the hypotheses are so many and the results meager.

A kid, a dog, and a pup. PickPik. CC0.

A kid, a dog, and a pup. PickPik. CC0.Dog is a classic example of this uncertainty (see my posts for May 4 and May 11, 2016). Responsible dictionaries list the main hypotheses and refuse to commit themselves to any solution. One feature unites the story of dog and body. Neither is a continuations (reflex is the technical term in this context) of an ascertainable Indo-European root: think of the vastly different Latin canis “dog” and corpus “body”! An English cognate of canis is hound (German has Hund). Where then is dog from? I think it was a dialectal baby word (most sources state that English dog is isolated, which is not true). No one was in a hurry to agree with me, but then no one found my reasoning wrong. Dialogs between etymologists often resemble those between people speaking different languages. Body resembles dog in that in Germanic, it is a word of very narrow provenance (only a few insignificant cognates in German). Therefore, a search for its very ancient source seems to be an unpromising occupation. Related forms have been sought for all over the world, in most cases, with moderate success (to put it mildly).

The common Old English word for “body” was līc (with a long vowel, as in Modern English leek), still recognizable in lychgate. The conjunction ge-līce (it corresponds to Modern German g-leich) “having the same form” lost its prefix and finally became the conjunction like (as in like father, like son) and as in the ubiquitous filler like (“Like, when I went in and saw, like, a hundred people, I was stunned”). The distant origin of like, a common Germanic word, is obscure. Perhaps it once meant “corpse” (as in German Leiche and in the already cited lychgate), but even if so, no light is thrown on the origin of the word. Russian lik “image” is hardly related. I am aware of several ingenious derivations of līc, and they confirm my belief that the more convoluted an etymology, the smaller the chance of its being correct.

Jealousy, a green-eyed monster. Othello and Desdemona by Heinrich Hoffmann. Public Domain.

Jealousy, a green-eyed monster. Othello and Desdemona by Heinrich Hoffmann. Public Domain.Now back to idioms. Phrases featuring some part of our anatomy are countless. The origin of some of them only seems transparent. Think of keep a stiff upper lip and put your best foot forward. What is the exact reference? The reference (once we discover it) comes as a surprise. By contrast, to keep someone at an arm’s length is picturesque enough to need an etymology. As usual, numerous idioms of this type have foreign sources (often Biblical or Classical). Compare an eye for an eye, which is from the Old Testament, and one hand washes the other, presumably, from Latin (manus manam lavat), though the idea of one hand helping the other is universal. It often happens that the same expression occurs in two European languages, and we cannot ascertain which is the borrower and which the lender. Thus, according to the OED, the earliest reference to the phrase to cut off one’s nose to spite one’s face surfaced in an English text in 1788, and an exact French analog exists. A few phrases were probably individual coinages by clever authors. For instance, in the heart of hearts is usually ascribed to Shakespeare, but then all words and all phrases were at one time coined by someone. Word creation is not committee work! Green-eyed monster “jealousy” certainly goes back to Shakespeare (in the Middle Ages, green was the special symbol of fickleness and inconstancy). We live in the world of familiar quotations.

Three Men in a Boat by Jerome K. Jerome. CC0.

Three Men in a Boat by Jerome K. Jerome. CC0. It is easy to cite further examples of the phrases whose reference seems obvious, even though no one knows where to look for the source. A particularly picturesque simile is as cold as a maid’s knee (with the variant a maid’s knee and a dog’s nose are the two coldest things in creation). Some people in England knew it in the 1870s, but who coined it and where? Alas, the Internet provides excellent information only on housemaid’s knee, but this is not my subject. Incidentally, I learned the medical term housemaid’s knee from Chapter One of Jerome K. Jerome’s delightful book Three Men in a Boat (To Say Nothing of the Dog). No one in my surroundings has read it. May I recommend it to all those who enjoy brilliant humor? As early as 1732, the phrase butter out of a dog’s mouth occurred in two senses: “you can’t retrieve what you have lost” and “you can’t make a silken purse out of a sow’s ear,” though the reference to the second sense is dubious. (Has any of our readers ever heard this phrase? Many regional sayings, like hundreds of once dialectal words, are now dead.)

Predictably, dozens old phrases refer to eye. By far not the most inspiring but the most often discussed one among them has been All my eye and Betty Martin. I wrote about it in my post for November 23, 2016, and it may be worth consulting because the comments following the post offer several important cases of antedating by Stephen Goranson, which I forgot to include in the aforementioned book Take My Word for It. Language Log, filed for June 12, 2008 (“Who is Betty Martin?”) provides curious reading, but as could be expected, no one knows the origin of the once popular phrase and, most probably, never will. Such is of course the fate of many words and idioms: “everybody” has heard them, but the source is lost. Are we dealing here with an amusing case of folk etymology? Or is the simile about Betty from a forgotten song? The phrase my eye and Tommy (the same meaning, that is, “nonsense”) also existed. Another curious phrase the bishop’s has had his foot in it was the subject of my post for May 20, 2015 (“Putting one’ foot into it”). On October 13, 2010, I wrote about the idiom pay through the nose. A reference to this post on the Internet ascribes an explanation to me I never gave!

Quite a few body (bawdy) idioms focus on the parts we usually keep covered, and I’d rather pass them by, though we have come a long way from the much-exaggerated modesty of the Victorian age.

Feature image by Henry Winkles and J. Gustav Heck. CC4.

From Abbas Ibn Firnas to Assassin’s Creed: The legacy of Medieval intellectualism

From Abbas Ibn Firnas to Assassin’s Creed: The legacy of Medieval intellectualism

The dream of flying has a long premodern history. Think of the myth of Daedalus, the ancient Greek inventor who designed wings for himself, and his ill-fated son Icarus. Or think of Leonardo da Vinci’s famous sketches and studies of birds and flying devices.

It might surprise many to know that, centuries before Leonardo da Vinci depicted birds in flight and flying machines in Renaissance Italy, an intrepid polymath in the city of Córdoba, in today’s Spain, may have carried out an experiment in early human gliding flight. My book, A Bridge to the Sky, focuses on that intrepid ninth-century aeronaut, Abbas Ibn Firnas, and the Islamic civilization that provides the backdrop and context for his life and work. As a specialist in medieval Islamic architecture, art, and history during the caliphal period (c.650-1250 CE) most of my work has focused on Córdoba, the capital of early Islamic Iberia. In A Bridge to the Sky I set out to understand Ibn Firnas’ unusual experiment, to try to understand why an intellectual in a medieval Islamic context imagined and then is reported by his contemporaries to have carried out such an unusual experiment, and why this might be significant for the way we understand the past.

Like the prototypical “Renaissance Man” Leonardo, with whom he is often compared, Ibn Firnas was a person of many talents: a poet, a musician, a philosopher, and a ‘scientist’ who designed fine scientific instruments for the Umayyad dynasty who ruled Córdoba and Iberia between the 8th and 11th centuries. He carried out fascinating experiments and activities that combine science and art, including designing and creating a chamber in his home that sounds very much like the medieval version of a 3D immersive Virtual Reality experience: famously, this experience made ninth century viewers imagine they were seeing stars, lightning, and clouds, and hearing thunder.

My book introduces readers to Ibn Firnas and his flight experiment, against the backdrop of caliphal artistic and intellectual cultures. Those who play the new Assassin’s Creed Mirage video game will find a different type of introduction in the game’s setting, its characters, and the historical information contained in its Codex.

The connections between my book and the game are reflective of my work as an external historian on Assassin’s Creed Mirage, which was released by Ubisoft in October 2023. The narrative setting of Mirage is Baghdad in the ninth century, and my role was to provide the Ubisoft in-house historians with detailed historical information about medieval Baghdad and Islamic art, history, and civilisation in the caliphal period.

The topics and entries represented in the game’s educational feature, known as the “History of Baghdad,” were chosen by Ubisoft’s historians, and were based on a series of thematic workshops that were very like an intensive graduate research seminar on the history and visual culture of the caliphal period. Out of those workshops, the Ubisoft team chose things they thought were important to include, focusing on art and the exact sciences (especially astronomy and engineering), all of which are central to A Bridge to the Sky.

For instance, players of Mirage can read about astrolabes, celestial globes, and other scientific instruments of the time, and see these illustrated in the Codex, much as they are in my book. In the game they’ll encounter astronomers, an astronomical observatory, and references to important treatises, including ones on astronomy, engineering, mathematics, and other exact sciences, which I write about in A Bridge to the Sky.

In A Bridge to the Sky, I write about the Banu Musa, three intellectual brothers who were ninth-century contemporaries of Ibn Firnas. Important Abbasid courtiers in Baghdad, they are especially well known for their work in engineering, thanks to their important treatise, The book of ingenious devices (Kitāb al-ḥiyal). In Mirage, players have the chance to ‘meet’ the Banu Musa, who provide Mirage’s protagonist, Basim, with ingenious tools and mechanical devices. Indeed, one of the game quests has players seeking one of the brothers, Ahmad, in the House of Wisdom, and investigating his workshop there.

I’ll leave it to players to learn if Ibn Firnas makes an appearance in the game, though I will say that players who go looking will find intriguing references to a flight experiment.

While working on a video game might be an unusual choice for a scholar, my reasons for doing so are the same ones that led me to write a Bridge to the Sky—a desire to make academic knowledge about medieval Islamic art and history widely accessible to broader audiences. In that sense my book and Assassin’s Creed Mirage are quite similar. Both depict a vibrant age of scientific and artistic achievement in which caliphal intellectuals imagined, created, and experimented with art and science, and which shares many similarities with later times and places, such as Renaissance Florence, with which today we are much more familiar. My hope is that readers of A Bridge to the Sky and those who follow Basim in his adventures through Baghdad in Mirage will come away with a new appreciation for the Age of the Caliphs and a period of medieval intellectual and artistic innovation that profoundly shaped global history, including Italy in the age of Leonardo, and eventually Europe’s Scientific Revolution.

January 8, 2024

Albrecht Dürer and the commercialization of art

Albrecht Dürer and the commercialization of art

The Nuremberg artist Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) is often thought of as one of the Renaissance´s greatest self-promoters. He might even be categorized as a “reputational entrepreneur.” Dürer was the first artist to depict himself on self-standing portrait panels. These three portraits now hang in some of Europe´s most important collections—the Louvre, the Prado, and Munich´s Alte Pinakothek—and frame our own image of him. Most strikingly, the German artist depicted himself on the last of these as almost identical to Christ. To many, the portraits hint at his arrogance and the type of Renaissance self-centeredness that culminates in the selfie culture of today.

Dürer’s portrayals can be understood through the rise of the art market. Anything recognizably done by his hand fetched better prices than what came out of a workshop as collaborative effort. To develop a distinctive approach to art, Dürer cultivated his mastery of depicting hair naturalistically with the finest brushes. Dürer turned his own hairstyle into something iconic—by 1500 he sported long, curled hair with golden highlights. It is thought that he kept his last, Christ-like self-portrait at home to attract clients. In relation to his printed work, Dürer fought hard to get a copyright on his monogram. Why? He was not a court artist, salaried and dressed by a ruler, but lived from what he made and sold, day-by-day.

It is easily overlooked therefore that there was great precarity to his life for much of his career. What looks like arrogance was bound up with fear and assertion out of anger against mean patrons. Becoming a painter, in the first place, had been a precarious decision. His passion for painting had cost Dürer a secure career as goldsmith, for which his father had trained him up from the age of five. Dürer the Elder was devastated when his teenage son told him that he did not wish to take over the workshop but wished to switch careers. Young Albrecht loved the vibrant paintings in Nuremberg´s churches. The most ambitious of these were grand altarpieces with their complex compositions and great spiritual power in the age before the Reformation. The end of the Middle Ages was marked by intense piety and the expectation that great religious images could bring to life what they depicted and could spiritually heal. A painter was a therapist of sorts, a healer of souls through his union with God and Christ, in whose image mankind had been created.

Fast forward to 1509, when Dürer was in his late thirties. He had been brilliantly successful in making innovative printed images and in getting recognized. His prints sold down to Rome. He achieved praise for an altar-painting in Venice that demonstrated his mastery of colours. German scholars lauded him as equal to the Greek master painter Apelles. Working on a new commission—an altar-painting for a rich Frankfurt merchant—Dürer felt ever more frustrated. What a gap between his reputation and his lack of cash to buy a nice house, nice clothes, and food, and to simply ensure that he and his family felt financially secure. He put a portrait of himself right in the centre background of the painting. “Do you know what my living expenses are?”, he challenged the merchant.

The question remains meaningful. Some think of artists as aesthetes whose moral purity and vision should be bound up with being disinterest in money. The British contemporary artist Damien Hirst by contrast is well known for his commercial success and for being open about his wish to be rich. Why, he tells us in an interview, should artists suffer, like van Gogh? “I think it´s tragic,” he says, “that great artists die penniless.” Hirst thinks that Andy Warhol was the first to make it ok for artists to be commercially minded without appearing as a “sellout.” Hirst would admire Dürer if he went further back in time.

Dürer resisted dying penniless and mentally tormented—something which would happen to so many well and little-known artists who refused to play the art market in the Renaissance and supposed Golden Age of art that followed it. Adam Elsheimer, a pioneering German landscape artist in Rome around 1600 is a less well-known example; Jan Vermeer remains the most famous pre-modern artist whose own life and fortune of his small family ended in tragedy.

Dürer, by contrast, died a rich man—today he would be a millionaire. He saved up most of his assets, though, so strong was his need to feel financially secure after decades of living on loans for greater expenditures and paying in installments. Up to the end of his life, he accounted for pennies of expenditure, noting down when his wife bought a broom or he purchased cheap pigments made from red bricks. This was despite the fact that the couple had no children to leave an inheritance for.

Dürer´s late financial success came at a price though. Despite writing nine letters to the Frankfurt merchant in 1508 and 1509 to explain what was involved in painting an altarpiece well and would constitute a fair price, Dürer failed to achieve what he regarded as decent pay. The experience left him scarred, and the artist´s decision was radical: he would no longer take on commissions for new altarpieces. Imagine if a composer of complex symphonies, or a writer of novels, suddenly stopped work while at the top of their game. Understanding such transformative decisions opens a new window onto Dürer and his age when patterns of consumption and commerce changed. Succeeding as an artist meant experiencing losses and gains. The birth of the artist in the Renaissance was bound up with rich emotions and challenging adjustments to the rules of the market, even for the most established of artists. Dürer´s amazingly innovative prints, such as his “Melencolia I” in 1514, demonstrate that he never became a sell-out. Still, his life is full of questions for our own time and for an artist like Hirst—the first to go as far as giving collectors the choice of burning original paintings as they buy its version as a digital asset, an NFT. The NFT includes a hologram portrait of the artist. Dürer most likely would have approved.

Feature Image: Albrecht Dürer, ‘Self-portrait’, Museo Nacional del Prado. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

January 7, 2024

Janus words

January gets its name from Janus, the Roman god of doors and gates, and (more metaphorically) the god of transitions and transformations. What better time to talk about so-called Janus words.

Statues of Janus depict him with two faces, one looking to the past and one looking to the future. Janus words are ones that signify a meaning but also its opposite. They are sometime also called contranyms (or contronyms), antagonistic terms, auto-antonyms, or even the fancy Greek term enantiosemes. Typical examples include oversight, a noun which can mean a mistake or can mean monitoring something, peruse, a verb meaning to skim or to read extra-carefully, sanction, meaning to allow something or to penalize someone, and citation, which can refer to an achievement or a violation. And there are even Janus greetings, like aloha, ciao, and shalom, which can be used for “hello” or “goodbye.”

Janus words arise because of polysemy: words get their meaning from their use, and as words are used in new circumstances, new meanings arise. Sometimes the new meaning extends part of the older one, as when peruse shifts from “to read carefully” to mean “to read quickly” or when citation goes from “document listing an achievement” to “document listing a violation.” Over time, the specifics of a meaning can be radically reinterpreted. If you read something carefully and quickly, both meanings come together. And actions noted in a citation can be good ones or bad ones. When you dust something, that involves doing something with particles of matter: you can dust a room by removing dust or you can dust a crime scene or a cake by sprinkling around some powdered material.

Some Janus words are oddly idiosyncratic: the verb strike means “to hit,” but in baseball, a strike occurs when you fail to hit the pitch. It may be called a strike because you struck at the pitch, but didn’t hit it. And there is the Christmassy term to trim the tree, which means to decorate the tree with ornaments, not to cut off its limbs. The opposed meanings make more sense if you think of trim’searlier meaning “of putting something in order.” When we trim hair or hedges or meat,cutting away is involved, but we are also putting the hair, hedges, and meat in proper condition. And we refer to ornamentation of clothing and buildings as trimming. You may have eaten a holiday meal with “all the trimmings.” So trimming the tree retains the sense of fixing it up, while trimming the hedges combines the idea of putting something in order with the idea of cutting away the overgrowth.

Many Janus words are a natural consequence of the twist and turns that meanings take and it’s easy to find long lists words that can have more-or-less opposite meanings. Each has its own story and circumstances and some are more convincing than others. The two meanings of cleave (“to adhere to” and “to split”) arose by accident, from homophones with different meanings (Old English clifian and cleofan). The same is true for clip (“to attach” or “to cut away”).

There are also Janus phrases and Janus word parts (or “morphemes” as we linguists call them). “It’s all downhill from here” can refer to easy sledding or a downward fall. And if you say “That takes the cake,” the idiom can mean outstanding or egregious, depending on the situation (and perhaps on the intonation). And the morphemes awe- and ter- can be good or bad depending on whether we are talking about something “awesome” and “terrific” or “awful” and terrible.” Other words get their Janus-like meanings from the ways in which they are combined, like unbuttonable or inflammable.

Finally, there is the much-maligned literally. That’s a word that many of us sometimes use to mean “figuratively” (as in “literally paved with gold” or “literally climbing the walls”) and other times to mean “not figuratively” (“to take someone’s comments literally” or “is literally a baby”). As is the case with many other adverbs, the intensified use of literally takes over as the core of the meaning.

Figurative literally gets a bad name because of the starkness of the contrast of the two senses and of course because it is overused by some speakers. But it’s part of set of such words (such as totally, awfully, terribly, completely, and more), where intensification has shifted an earlier word sense.

In any event, I think Janus words are literally awesome.

Featured image by Glen Carrie via Unsplash.

December 20, 2023

English spelling, rhyme, rime, and reason

English spelling, rhyme, rime, and reason

Alexander Pope, not a friend of hackneyed rhymes. Jonathan Richardson, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Alexander Pope, not a friend of hackneyed rhymes. Jonathan Richardson, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.The story of rhyme has been told more than once, but though both The OED and The Century Dictionary offer a detailed account of how the word acquired its meaning and form, it may be instructive to follow the discussion that occupied the intellectuals about a hundred and fifty years ago and some time later. To begin with, there is a rather infrequent English word rime “hoarfrost,” which has nothing to do with poetry. We are interested in the rhyme, as described in 1711 by the then twenty-two-year-old brilliant wit Alexander Pope: “They ring round the same unvaried chimes / with sure returns of still expected rhymes; / Where’er you find ‘the cooling western breeze’, / In the next line it ‘whispers through the trees.”

A few remarks about the etymology of rhyme are in order. At one time, it was believed that rhyme goes back to Old English rīm “number” (rīm, with its long vowel, must have sounded like today’s ream). Though Middle English rīm occurred as early as 1200 in the much-researched poem Ormulum, its meaning and origin are far from clear (see the end of this post!). Anyway, rīm1 (Old English) and rīm2 (Middle English) are different words. Orm, the author of Ormulum, lived in Danelaw and spoke a dialect, strongly influenced by Danish. According to the traditional opinion, Middle English rīm, which occurred most rarely, meant “rhyme,” and “was supplanted by the extremely common Old French rime,… identical in form and in original meaning, but used in Old French with the newly acquired sense of verse, song, lay, rhyme, poem, poetry,” to quote Walter W. Skeat.

Danelaw, where Orm lived and wrote his poem. Emery Walker, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Danelaw, where Orm lived and wrote his poem. Emery Walker, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.In the first edition of his great etymological dictionary, Skeat identified Old English rīm with Middle English rīm and derived rhyme from that word, but later he changed his opinion. It is now an established fact that rime, a borrowing of Old French rime, goes back to Medieval Latin rhythmus “rhythm.” This derivation poses the natural question about the difference between rhyme and rhythm, but before answering it, let us look at the word’s spelling.

In the eighteen-seventies, some linguists considered the spelling rhyme, with its h and y, foolish, because they rejected the analogy between English rhyme and Latin rhythmus (and its Greek source rhuthmós). The spelling rhyme goes back to Samuel Daniel, a once well-known poet, a contemporary of Shakespeare. Frederick James Furnivall, whose name is inextricably connected with the early stages of The Oxford English Dictionary, wrote in his 1873 discussion of Skeat’s spelling rime: “But as it seems to me a pity to re-introduce rime for A[nglo]-S[axon] [that is, Old English] rîm, when the hoar-frost rime had possession of the modern field, I adopted—as in private duty-bound—the spelling ryme of the best Chaucer manuscripts. And I think that any Victorian Englishman, who wants to cleanse our spelling from a stupid Elizabethan impurity, generated by ignorance and false analogy, should now spell either as Mr. Skeat or as I do.” The moral of the story is “make haste slowly.”

Elizabethan spelling is indeed nothing to admire or emulate, and today we are heirs to quite a few pseudo-learned monstrosities introduced in the sixteenth century, but by chance (from a historical point of view) rhyme is a correct form (which of course does not mean that it should be the one in use today!). This tug of war is known only too well: in spelling a modern language, should we be true to the word’s history or to its modern pronunciation? Unfortunately, neither principle can be followed quite consistently, as many fights about spelling reform in different countries have shown. The so-called iconic principle also plays some role, and here Furnivall was right: since the word rime “hoarfrost” already exists, it is better to do without its homograph.

Four random Victorian gentlemen. They never read Chaucer. CC0 via rawpixel.

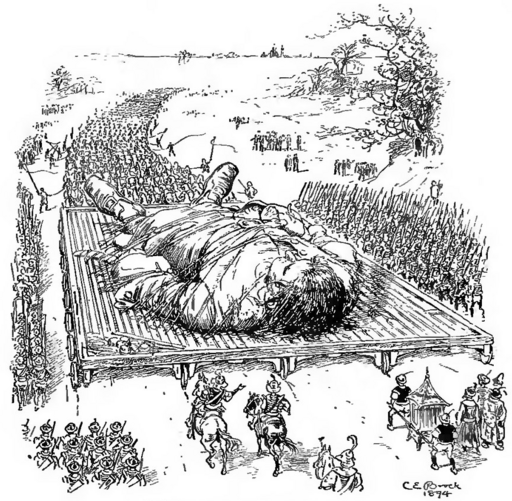

Four random Victorian gentlemen. They never read Chaucer. CC0 via rawpixel.But note the amusing reference to any Victorian Englishman. Furnivall had a rather low opinion of his male compatriots, and indeed one’s contemporaries, male or female, are sometimes hard to admire. He wrote: “No English gentleman would think of opening a book in the language, or deign to suppose that Chaucer wrote English, or could spell. And as to looking at any dictionary to know the history of a word, why, it’s plain nonsense. Evolve it out of your consciousness, and chaff anybody who appeals to recorded fact.” Do times change? Not being a Victorian gentleman, I can only register my surprise at a recent conversation with the students I have taught this year. They did not understand the word Lilliputian, and I said: “Why, it is from Gulliver’s first travel.” No one had read Swift or heard about Lilliputians, and no one had the remotest idea about the source of the now universally known word Yahoo.

Swift’s Lilliputians are much better known than some people think. Charles E. Brock, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Swift’s Lilliputians are much better known than some people think. Charles E. Brock, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.But back to etymology. I think the correct origin of rhyme would have come to light long ago if the German, French, and English researchers had been aware of the corresponding Russian word, which is rifma. Its odd-looking f owes its existence to th in Greek rhuthmós. In the word for “rhyme,” as we know it from the West-European languages, Greek th left no visible trace. Even so, it may cause surprise that “rhyme” goes back to a word meaning “rhythm.” The OED and other detailed dictionaries clarify the situation. Below, I’ll follow the exposition of The Century Dictionary.

Greek rhuthmós referred to many things, namely, “measured movement, time, measure, proportion, rhythm,” and “metrical foot.” The medieval Latin term, which continued into Old French, was applied especially to accentual verse, as distinguished from quantitative or classical verse, and came to denote verse with agreement of terminal sound, and in general any poems having this characteristic. The dictionary also adds that about 1550, with the increasing interest in classical models and nomenclature, English rime, ryme often came to be spelled rhime or rhyme, rithme of rhythme, and then rhithme or rhythme, the latter forms being at length pronounced as if directly derivatives of Latin rhythmus, from Greek ruthmós.

At the beginning of this essay, I mentioned the poem Ormulum (1200). Its author explained (in translation from Middle English): “I have written here in this book / among the words of the Gospel / all by myself many a word, / in order thus to fill the ríme.” The latest study of ríme, that is, rīme, in Ormulum, seems to have appeared in 2004 (Nordic Journal of English Studies 3, 63-73). It author, Nils-Lennart Johannesson, made a strong argument that Orm’s ríme was not a borrowing from Old French but derived from Old English and that, consequently, its sense in the poem is “story; text,” rather than “rhyme.” If this conclusion is valid, the earliest citation of the English word rhyme will disappear from our records. For students of English words and of English literature, this will be a significant conclusion.

However, one curious French trace of rhyme (among many others) will remain. The alliterating phrase neither rhyme nor reason does have a French source (n’avoir ni rime ni raison, sans rime ni raison). It has been around for many centuries, but I could not find its origin in French. Even its source in English (I mean the source, rather than the earliest attestation) is unknown: it looks like a coinage by some wit, “a familiar quotation.” But then once upon a time, all idioms and all words must have been individual coinages.

At this time of year, The Oxford Etymologist will take a traditional break and will reemerge on the second Wednesday of January 2024. A Happy New Year!

Feature image: Ms. Codex 196 English religious poems . Public domain, via the University of Pennsylvania, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts.

December 15, 2023

Five ways the British magnetic enterprise changed the concept of global science

Five ways the British magnetic enterprise changed the concept of global science

The concept of global science was not new in the nineteenth century. Nor was that of government-sponsored science. But during the 1830s and 1840s, both of these concepts underwent a profound transformation: one that still has ramifications over today’s relationship between specialist knowledge and the modern nation state.

We are used to governments invoking scientific advice and technical expertise when making policy, be it in the handling of a global pandemic, or the formation of strategies for mitigating anthropogenic climate change. In the nineteenth century, however, the mobilization of the natural sciences for governance was embryonic. True, past governments had looked to scientific practitioners for solutions to technical challenges, most famously in the development of reliable methods for calculating longitude at sea throughout the eighteenth century. Yet the nineteenth-century problem of terrestrial magnetism would see the extent of such activity escalate both in financial and geographic scale.

Amid growing anxieties over the threat magnetic-induced compass error presented to oceanic navigation, and philosophical concerns over how the Earth’s magnetic phenomena operated, the British state provided the military, naval, and financial resources to transform the study of terrestrial magnetism into a world-wide study. The impact of this was to change the concept of “global” science in five ways.

1. To truly know how a global phenomenon operated, you had to be able to coordinate and synchronise experimental measurements over vast geographical space, even without modern communications technology.The great challenge of charting the world’s magnetic phenomena is that you have to know how it changes over time and physical space. Edward Sabine, the magnetic fanatic leading Britain’s magnetic enterprise, was well aware of this problem: a successful survey would depend on the coordination and synchronization of magnetic experiments around the world, in an age before modern communications technologies.

Sabine was especially concerned with recording magnetic epochs, that is to say, single moments in which the Earth’s magnetism was measured at the exact same time, producing a snapshot of its magnetic properties. However, ensuring naval ships and observatories around the world performed such experiments in synchronization demanded a strict regime or, rather, a system of magnetic data collection.

Sabine was not the first to appreciate the global nature of examining magnetic phenomena: Alexander von Humboldt had promoted such an approach to the study of a series of natural phenomena, including terrestrial magnetism, during the 1800s. An Empire of Magnetism really is the story of the development of a system for realising such global ambitions. It demonstrates the crucial role of the state in delivering such a system.

2. The state could play a transformative role in the collection of data from around the world.In the nineteenth century, the Royal Navy was the most powerful military organization in the world. Britain’s empire was the most expansive of all of Europe’s colonial powers. And the British Treasury was unrivalled in its capacity for expenditure. Put together, these resources were beyond what any individual, private or corporate, or voluntary organisation, could mobilize in the investigation of terrestrial magnetism or, indeed, any natural phenomenon.

The allocation of money to sustain scientific activity was nothing new, but the extent and broadening range of material assets involved in the British magnetic enterprise was unprecedented, including ships, trained officers, overseas territories for observatories, building materials, the funding of instruments, and human calculators. Of particular value was the formation of a Magnetic Department at Woolwich Arsenal, which provided Sabine with a disciplined team to process incoming magnetic data and reduce it to the order of charts. This effectively made possible the rapid publication of the survey’s results, though this task would not be complete until 1877.

3. The military’s potential to deliver discipline for realizing a global scientific enterprise.Naval and army officers were far from perfect experimentalists: they frequently made errors or damaged their magnetic instruments. However, they did provide a disciplined labour force with which to realise a global survey.

For a start, they were under orders, particularly those emanating from the immensely powerful Admiralty. When instructed to undertake experimental training, they obliged, and when told to be diligent in making measurements at fixed times, they performed these as directed. Sometimes, other duties or circumstances prevented officers from performing their magnetic work, but generally they followed their orders, be it from Sabine or the Admiralty.

They also had obedient crews or non-commissioned officers from the Royal Artillery or Royal Engineers to assist in the practicalities of magnetic experiments: dipping needles, the primary instruments for measuring magnetic phenomena, tended to be heavy, while constructing temporary magnetic observatories was physically demanding and required teamwork. Naval officers like Sir John Franklin and James Clark Ross needed little persuading to be industrious in their collection of magnetic data and it was not uncommon for magnetic practitioners to become committed to their study of magnetic phenomena, but military order and discipline was crucial to a systematic surveying of the globe.

Fox’s Falmouth-built dipping needle as portrayed in Annals of Electricity in 1839.

Fox’s Falmouth-built dipping needle as portrayed in Annals of Electricity in 1839.(Author’s image, 2020)4. The rising significance of standardization for producing consistent results, despite a diversity of contributors of varying experimental skill.

The key to transforming the Royal Nay into an organ of scientific investigation was standardisation. Sabine, along with Cornish natural philosopher Robert Were Fox, were constantly engaged in developing and refining a network of instruments training, instrument manuals, and experimental procedures that could allow naval and military officers to collect and return reliable magnetic data, be they performing experiments in Cape Town or Hobart, or on a ship in the middle of an ocean. The effort that this involved is well exhibited by the immense volume of surviving correspondence on the subject of dipping-needle design, especially between Fox and Sabine, but also with naval officers like John Franklin and James Clark Ross.

But it is also evident from the number of revised instrumental manuals produced during the 1830s that the promoters of the enterprise were eager to produce written instructions of greater clarity that could shape the actions of experimentalists, regardless of their location or distance from Sabine’s immediate direction. Likewise, Fox regularly invited naval officers to his home in Falmouth, where he could guide them on the use of his instruments. Achieving standardization was both crucial to the operation of Sabine’s system of magnetic data collection, as well as a source of constant labour for those at the centre of global survey work.

5. Public accountability would take on a growing urgency in global scientific enterprises that relied on state support.Traditionally, if a nation state sponsored scientific activity, the question of public accountability was of low concern. Given that most pre-nineteenth-century forms of governance were essentially autocratic, usually being the business of unelected monarchs, this is hardly surprising. The eighteenth-century British state had invested into the resolution of the longitude problem, but Parliament was representative of a very narrow socio-political elite. With the passing of the 1832 Reform Act, which extended the vote to the middle classes for the first time and increased the franchise from around 400,000 to about 650,000, Parliament was faced with questions of accountability to a broader electorate.

It would be a mistake to exaggerate the impact of the Reform Act, given that voters still had to be small landowners, tenant farmers, shopkeepers, or in a household with an annual rent of £10, and also be male. Mid-nineteenth-century Britain was very far from a representative democracy as we would know it now. Yet, undoubtedly, the problem of public accountability escalated after 1832. Along with the repealing of a host of taxes, most famously the abolition of the Corn Laws in 1846, Parliament found itself under increasing scrutiny, especially over perceived financial extravagances.

The 1830s and 1840s saw a series of economizing measures, with both Whig and Tory administrations cutting government expenditure, particularly on the armed forces. During this period, we see the rolling back of what historian John Brewer has described as the “fiscal-military state”; that is to say, the disintegration of the system of high-taxation and high-military expenditure which had been crucial to Britain’s victory over the Revolutionary and Napoleonic French states during the 1790s and 1800s, but was largely redundant after Britain’s victory over Napoléon Bonaparte in 1815. In this context, promoters of the British magnetic enterprise were under constant pressure to justify themselves with increasingly broad public audiences.

Changing the face of scientific studyIt is important to note that “global science,” in the sense that we use it today, was not an actor category in the mid-nineteenth century. Nevertheless, the magnetic enterprise’s promoters were keen to stress the project’s global ambitions and world-wide extent. Britain’s magnetic enterprise was central to a broader trend in nineteenth-century science. Increasingly, scientific practitioners were looking at the world as a complex network of interconnected natural phenomena. The global study of terrestrial magnetism concurred with the world-wide collection of data and observations, including astronomical, geological, botanical, anthropological, and tidal. Yet it was the performance of magnetic measurements that required the greatest organization in terms of coordination and synchronization. The examination of terrestrial magnetism’s protean nature, both in terms of time and physical space, required a system that could operate on a global scale.

Feature image: Owen Stanley – Voyage of H.M.S. Rattlesnake : Vol. I. f.6 The Pursuit of Science under adverse circumstances, Madeira. Image out of copyright, original held at Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales .

December 14, 2023

7 ways to deal with the rejection of your manuscript submission

7 ways to deal with the rejection of your manuscript submission

Publication in peer-reviewed journals is an integral part of academic life, but however successful you are in your research career, you’re likely to receive a lot more rejections than acceptances of your submitted manuscript. Excelling as a researcher requires a delicate balance between handling rejection and savouring fleeting moments of triumph – after all, it’s estimated that at least half of all papers undergo one or more rejections before finally being published. Here are 7 suggestions on how to cope, understand, and learn from manuscript rejection.

Cope1. Acknowledge your feelings

First of all, let’s be upfront that rejection hurts – bad news and stressful situations can have a physical effect on a person. Whether this is your first rejection, or you have dealt with this before, it doesn’t necessarily make rejections any easier to bear. If you need advice or support, consider talking with senior colleagues who will doubtless have gone through the same emotions on countless occasions.

2. Build resilience.

Resilience is the ability to meet, learn from, and not be crushed by the challenges and stresses of life. As manuscript rejections are all too common for researchers, resilience will be crucial for helping you bounce back and try again. In many careers, ambition comes with the risk of being turned down, but it doesn’t mean that you should give up. Robert Wickes explains that although everyone has different a range of resilience, we can make a conscious decision to be self-aware, to practice self-care, and to apply ideas from positive psychology.

Understand3. Re-frame rejection as success.

Any ambition comes with a risk of being turned down and I believe that if your manuscripts are never rejected, you might not be aiming high enough. While there are many factors you should consider when choosing where to publish your research, the reputation and prestige of the journal tend to top the list when academics rank their priorities.

Submitting your article to the top journal in your field or well-known cross-disciplinary journals inevitably comes with a higher risk of rejection because of the amount of demand and competition, but it is worth a try if you feel your findings are important, and it does keep life exciting. If you do feel your findings are important, a high-level submission may also provide the opportunity to obtain expert reviewer comments, which can be especially valuable to early-career researchers who want to improve their manuscripts.

4. Understand the rejection.

There are multiple reasons your manuscript might have been rejected and it is important to try and understand why.

An editorial or desk rejection is when your article is rejected without being sent for peer review. Most journals have a limited (and often diminishing) pool of willing reviewers nowadays, so need to be quite careful which manuscripts they send off for detailed consideration. Desk rejections often happen because the topic or article type does not match the journal’s scope, or because it does not conform to the submission requirements. It might be worth double-checking previously published articles and instructions to authors.

If you do receive reviewer comments, you can at least take heart that an editor was interested enough in your ideas or results to seek further opinion. When you are in the right mindset to do so, try to consider these comments so that you can take practical, level-headed steps towards another submission. A constructive review, even if negative, will explain whether the reviewer thought there was a fundamental problem with your methodology or premise, or whether they disagreed with specific aspects of your interpretation of results or your arguments.

Should you try to guess your anonymous reviewers?

No. It’s been investigated and doesn’t work (example 1, example 2). Also, that way lies academic paranoia which won’t do you any favours—knock it on the head and move on.

5. Understand your options.

Just because your manuscript was rejected, doesn’t mean it’s the end of the road. It’s important to know what next steps you can take.

The ‘cascade’ process, also known as transfer, is intended for papers that are deemed inappropriate for the initial journal they were submitted to. If this applies to your manuscript, the editors may recommend one or more alternative journals from the same publisher. You will be given the choice to submit your work to one of these suggested journals for evaluation. Alternatively, you can opt to submit your article elsewhere.

Should you appeal a rejection?

My advice is that it’s usually more beneficial to focus on moving forward. I would only consider appealing if a manuscript was rejected due to a single concern or a minor misunderstanding. If you are considering an appeal, a good first step is checking the ‘instructions to authors’ page to see if they have an appeals policy but if this isn’t available, you can contact the journal administrator for advice.

Learn6. Act on constructive feedback

There is something a little objectively strange about a community whose members spend their time anonymously commenting on and evaluating each other’s work. But take advantage of the outside perspective and act on constructive feedback. I recommend that you discuss any feedback with co-authors or your supervisor and decide which aspects of your article need revision.

Before you submit your article to a new journal also take the opportunity to revisit your abstract/summary and cover letter, to ensure they are as compelling as possible.

7. Get Involved

One of the best ways to improve your own writing is to go behind the curtain and experience reviewing and editing other academics’ work. Nowadays your email need only appear once or twice on published work, and you’ll find yourself receiving several peer-review requests each week along with every other form of academic cold-calling. Some will be relevant (within your field of expertise), so why not contribute?

For early career researchers, there are an increasing number of schemes and initiatives to help you with training and involvement. For example, lots of journals offer support for researchers who are new to peer review and editing.

December 13, 2023

Going on an endless etymological spree

Going on an endless etymological spree

I have more than once remarked that though I despise punning titles, the temptation to use them is too strong. Sure enough, this post is about spree, a word that has existed in English since roughly 1800. Noah Webster (1758-1843) knew spree and included it in the first edition of his dictionary. He defined spree as “low frolic” and branded it as vulgar. By the eighteen-eighties at the latest, the word’s status was upgraded to “colloquial.” Some modern dictionaries call spree slang. Webster had nothing to say about the word’s origin, but The Century Dictionary referred hesitatingly to Irish spre “spark, flash, animation, spirit.” Spree alternated with the earlier recorded forms spray and sprey.

Before writing this essay, I, as always, consulted the Internet. The most detailed information on spree appeared on Etymonline, an online etymological dictionary. Nothing in the relevant entry is wrong, but I would like to comment on one aspect of the information given there. We read that according to Barnhart (that is, The Barnhart Dictionary of Etymology, 1988), spree goes back to French esprit. I am not sure who was the first to derive spree from esprit, but it was certainly not Barnhart. Then Old Norse sparkr, Ernst Klein’s etymon, is cited. This is another very old suggestion, and Henry Cecil Wyld (whose dictionary appeared in 1932) already mentioned it as possible. Finally, we read that Calvert Watkins supported the Gaelic etymon of spree. The reference is probably to the first edition of The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, where English words are traced to their Indo-European sources. As mentioned above, this too is a well-known hypothesis. For instance, the same information appears in Eric Partridge’s 1958 etymological dictionary called Origins.

A drinking bout of old. Fatigues of the Campaign in Flanders by James Gillray. CC0.

A drinking bout of old. Fatigues of the Campaign in Flanders by James Gillray. CC0.Here is my point. None of the three sources—Barnhart, Klein, and Watkins—offered original hypotheses on the etymology of spree. All the explanations in those sources were derived from earlier works. Each compiler chose what he considered to be the most plausible hypothesis. References to them as authorities are fine, as long as we realize their place in the history of the research, but no one should be misled into thinking that those lexicographers said something new about the etymology of spree or any other English word for that matter. Walter W. Skeat, James A. H. Murray, and many others did, but not they. I believe that references should make this clear.

And now to business. As noted, spree was traced to Irish long ago, and the Celtic origin of this word has never been given up. In 1931, Thomas F. O’Rahilly, a recognized authority in the area, “had no doubt” that the word was a borrowing of Scottish Gaelic spraigh. In addition, he cited the word spreadhadh “bursting, activity, life, noise” and noted that English burst also occurs with the sense “a bout of drunkenness, spree.” Of special interest is his following statement: “From the 16th cent[ury]… spréidh or spréadh is also found as a verb, in the sense of ‘scatter, disperse, sprinkle’; for the meaning compare Engl[ish] sparkle (‘to emit sparks’), which formerly also meant ‘to scatter, disperse’, and also the connection between Engl[lish] spark and Lat[in] spargo [‘to scatter, strew, sprinkle’].” I may add that English sparse, from sparsus, the past participle of spargo, an eighteenth-century word in English, originally referring to widely spaced writing, was also a Scottish loanword. My only objection to O’Rahilly concerns the phrase no doubt. Whenever a scholar uses it, we understand that doubt is possible.

Sparkling wine, sparkling wit. Felices fiestas by Demi, CC2.0. Via Flickr.

Sparkling wine, sparkling wit. Felices fiestas by Demi, CC2.0. Via Flickr.Spree may indeed be a Scottish borrowing in English, but this fact says nothing about the word’s etymology. However, we cannot help noticing that English spree, spark, and sprinkle, along with Latin spargo, have a similar “skeleton,” namely, the group spr. Also, as pointed out at the beginning of this essay, in spree, spr– seems to be all that matters, because the form spree alternated with spray ~ sprey (the vowel was added for good measure, because a monosyllable needs a vowel). Now, forgetting about spree, we observe that in English, spray can mean (1) “a slender shoot; twig” and (2) “a jet of vapor” (spray2 was originally spelled spry!), while spry is a Modern English word in its own right (“active, brisk”).

It again begins to look as though the entire structure hangs by a single nail, and that the group spr suggests bursting forth, stretching, extending, unrolling, and so forth. Yet we could not expect that spr– arouses similar associations and evokes similar images everywhere. Yet it does play the same role in Celtic (if spree is a borrowing) and Latin (sparsus). The shortest list of spr– words in English confirms the initial impression: consider sprag (alternating with sprack) “a lively young fellow,” sprawl, spread, spring (noun or verb), sprinkle, sprout, and spry. Nealy all of them were recorded relatively late and are usually dismissed as words of unknown (uncertain) origin.

A curious case is the verb speak, related to German sprechen. As could be expected, the origin of the verb is obscure, and so is the cause of the old sp- ~ spr- variation. Dictionaries cite possible cognates in Welsh and Albanian, along with Old Icelandic spraka “to crackle; to sprawl” and sprika “a pretentious man.” The underlying meaning of Old English sprecan may have been “holding forth” or “loud statement; eloquent utterance.” Old English spræk “a shoot, twig” (see it above; æ has the value of a in Modern English rack) again comes to mind. Long ago, the now half-forgotten English etymologist Hensleigh Wedgwood offered no hypothesis on the origin of spree but listed a few spr- words in various languages, including Polish (!). Wedgwood often neglected regular sound correspondences at his own risk, and his habit of stringing together multiple forms from all over the world has little to recommend it, except when we deal with sound-imitative and sound-symbolic words, along with those used “for the nonce,” that is, for a particular situation, because such words may not obey sound laws.

A perfect image of what spr- means. Rawpixel. CC0

A perfect image of what spr- means. Rawpixel. CC0Spree has been classified with words of unknown etymology. We may ask: what exactly do we want to know? What new conclusions can we expect from further research? Or does the verdict “origin unknown” stick to spree like a death sentence? I think the situation is less ominous and somewhat reminiscent of the one I discussed last week, in connections with the word shark, but the case of spree is perhaps more transparent. In many languages, the sound group spr seems to have suggested to speakers the idea of spontaneous, unregulated growth. One could say spray, spry, sprawl, spræk, spring, and, among others, spree. Of course, in the beginning, some of those unbuttoned coinages were what we today call slang. (Or are all recent unborrowed words slang? Last week, I mentioned flub and wonk.) Once the newcomers find acceptance, some of them become colloquial or regular colorless words. Weren’t all or most of the ancient roots, reconstructed by comparativists, such? In this context, it is especially instructive to note that spontaneous word creation is not the privilege of distant epochs and that language creativity is a process equally characteristic of all ages. Some inspiring ideas on this subject can be found in the works by Wilhelm Oehl, to whose little-known and sadly underappreciated heritage I often refer in this blog.

Feature image via Pexels.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers