Oxford University Press's Blog, page 30

April 4, 2024

Pay attention to your children

Pay attention to your children

You’ve probably been ignoring your children. This isn’t simply you not paying attention to them because you’re distracted or need to do something. You don’t know what your children like and dislike. You don’t know their names and ages. You probably haven’t even acknowledged the existence of some of your children. You may be thinking “How could I not know how many children I have?” or “I don’t even have children!” and find the assertion that you’re ignoring and don’t know your children as outlandish. But equally bizarre is the fact that your children don’t know you. How can this be?

Your children are in foster care. Before you argue, let me explain. I know that you may not have a biological or adopted child who’s in foster care. But you still have children in foster care. When the state determines that a child’s parents or caregivers are not able to care and provide for a child, the state can remove the child from their home and place them in foster care. At this point, the state assumes the responsibility of parenting the child. The state uses money from taxpayers to provide for the child while in foster care. As taxpayers, you and I have a responsibility to the children in foster care. Our money is supporting the foster care system. It is our foster care system. And the children in foster care are our children.

Most children in foster care will be reunified with family. Some will be adopted. Other will enter a guardianship. However, not all children receive permanency. Some remain in foster care until they are adults. Eventually, these young adults who do not obtain permanency—through no faults of their own—leave foster care. These young adults are often referred to as “youth aging out” or “care leavers.”

Research consistently finds that compared to their peers who have not been in foster care, those who are “aging out” of foster care have poorer outcomes across multiple domains, including education, employment, housing, health, mental health, substance use, justice system involvement, and early parenting. As they are leaving foster care and entering adulthood, many of these young adults experience hardship and encounter structural barriers. These young adults typically lack support and resources as they age out. How is this a concern to you?

The current social norm is that parents support their children during the transition into adulthood. Parents of young adults often provide their children a place to live, assist with paying bills, help in times of crisis, offer encouragement, and provide guidance. Most young adults are not told by their parents “you’re on your own” on their 18th birthday when the state recognizes them as adults. However, when someone in foster care enters adulthood, they can find themselves without support. They may lose access to resources and services. There are some areas where extended foster care is available, allowing a young person to remain in foster care. However, not all young adults decide to remain in foster care. Other programs may be available based on where a young person is aging out and their life circumstances; however, many young people aging out still struggle.

These are our children aging out of foster care. To be consistent with the social norms, we should help those who are aging navigate the transition to adulthood. There are many ways that taxpayers can help young people aging out. First and foremost, we need to know about the young people in and aging out of foster care and recognize the importance of helping them. How each of us helps these young people is going to vary based on our resources and abilities. The ways we make a difference and help young people aging out of foster care are practically endless. It all starts with us adopting the mindset that children in foster care are our children and that we must pay attention to our children.

Featured image by Aditya Romansa via Unsplash, public domain.

April 3, 2024

An etymological plague of frogs

An etymological plague of frogs

Last week, I discussed a few suggestions about the origin of the English word frog. Unfortunately, I made two mistakes in the Greek name of this animal. My negligence is puzzling, because the play by Aristophanes lay open near my computer. I am grateful to our correspondent for pointing out the error, but is the etymology he offered his own? He referred to an online explanation of the Greek noun. Yet no hint of his hypothesis can be found in it. The Greek word is either sound-imitative, like the Latin one (rāna), or of unknown origin. What he suggested is an example of folk etymology. Even less trustworthy is his idea that the Germanic name of the frog goes back to Greek. Why should it?

In the previous part of this essay, I mentioned two attempts to account for the origin of frog and its cognates elsewhere in Germanic and argued that the word cannot be traced to the idea of the frog’s skin being slimy or to the frog’s ability to jump. Yet I did not mention a third hypothesis, which derived the name of the frog and the toad from the Indo-European root “to swell.” This reconstruction allowed some etymologist to trace Greek br– and Germanic fr– to the same ancient root. Only the images in the post referred to that idea. At the end of the essay, English pad “frog” or “toad” (!) came up for discussion, and I suggested that pad is a sound-imitative word, with reference to the animal’s going pat-pat or pad-pad.

It will be remembered that the Old Germanic languages had several names of the frog. Even in Old Icelandic, three words competed: froskr, frauki, and frauðr (read ð as th in English the). They look like different names, rather than phonetic variants of the same word. Apparently, as long as the group fr– remained in place, the speakers felt that the frog had received its due. The call of the frogs’ chorus in Aristophanes is brekekeks-koax-koax. Incidentally, when an ugly toad abducts Thumbelina, Hans C. Andersen makes “her” say: “Koaks, koaks, brekkekekeks,” straight from the Greek comedy. There is some reason to believe that frog and its lookalikes elsewhere are sound-imitative words, with cr- ~ kr, br-, and fr– serving the same purpose. By the way, the German for “toad” is Kröte! The oldest recorded forms of Kröte were krete ~ krede, krota, and krade. An onomatopoeic origin of Kröte is worthy of consideration.

The general impression is that the name of the frog was a popular, playful word without “respectable” Indo-European ancestry. A curious case is dialectal (Low German) Pogge, resembling both Middle Dutch padde and English pad. (Old Icelandic had padda; German Padde could designate both a frog and a toad.) In 1990, the German philologist Norbert Wagner suggested that Pogge is a pet name of frogga. He noted that in pet names, fricatives (that is, consonants like f and þ/th) are regularly replaced by the stops p and t. Theodore becomes Ted, Philip becomes Pip (as in Dickens’s Great Expectations), while Frisian Franz and Italian Francisco emerge as Panne and Paco.

Here is Dickens’s Philip, known to the world as Pip.

Here is Dickens’s Philip, known to the world as Pip. I entreated her to rise by F. A. Fraser, The Victorian Web. Public domain via GetArchive.

Wagner’s idea looks appealing in light of the fact that in many parts of Eurasia, the names of the toad and the frog tend to be expressive. English pad is not a variant of Pogge, but if Pogge goes back to frog, the reference to the expressive nature of pad receives some reinforcement, and the attempts to trace frog to some ancient root meaning “slimy, frothy” or “jump,” or “swell” lose the small appeal they may still have to some etymologists. To reinforce the idea of playfulness in naming toads, I’ll cite the words designating this animal in several modern German dialects: Ütsch, Pädde, and Quadux. The first, almost certainly, and the third not improbably, are expressive.

Incidentally, Ütsch resembles English ouch (an exclamation perhaps of German descent). Indeed, you see a toad and exclaim in a totally uncalled for outburst of disgust: “ütsch!”—don’t you? (What is so wrong with the poor toad?) If my guess about the connection between Ütsch and ouch is correct, I may be the first to have suggested such an exotic solution and swell with pride, because discovering a new etymology is hard, and ouch is such an important word. As Albert Einstein once said, ideas occur so seldom. By way of conclusion, I should express my strong disagreement with William Sayer’s paper: “The Etymology of English toad: Effects of the Celtic Substrate.” Nothing in the history of toad testifies to a foreign influence. The article is available online.

Ouch!

Ouch! Image by Jesse Milan, CC2.0 via Flickr.

As is well-known, the word frog has numerous senses, unconnected with the animal. Frog refers to objects that hold things in place: a certain fastening, a loop, and a device on a rail. In the body of a horse, frog denotes a pyramidal substance in the sole of the hoof. One can also cite a few German analogs. The motivation for calling each of such things a frog is usually said to be unknown. Yet of crucial importance is the fact that the Finnish Sampo “the pillar of the world” shares its root (sampa) with sammako “frog.”

The picture all over Eurasia yields the same result: the world was believed to stand on the back of a primordial animal: a frog, a fish, or a whale. The literature on this subject is huge. Finnish scholars have been especially active in studying the connection between frog “animal” and frog “a supporting device,” while English and German etymologists have hardly referred to Eurasian myths in trying to explain the many senses of frog ~ Frosch. (Note that a frog is found in the foot of the horse.) Yet my knowledge of the relevant literature is superficial. It would be tempting to show that frog “device”–-from “the support of the pillar of the world” to “part of the horse’s anatomy”—goes back to ancient folklore. Is such a hypothesis feasible? The late attestation of frog “device” in English and German poses an almost insurmountable problem in this reconstruction.

Don’t despise frogs. They are princes and princesses in disguise.

Don’t despise frogs. They are princes and princesses in disguise. Image by MCAD Library, CC2.0 via Flickr.

Frog “a hoarseness in the throat” may refer to croaking, but a tie between frogs (and especially toads) and diseases, such as angina, may again go back to ancient myths. An evil toad on the breast is a familiar image in folklore. Yet frog folklore is varied. Every year, the Nile was expected to overflow its banks. When it did, countless frogs appeared in the fields. The Egyptian goddess Hequet (or Heket) was worshipped, because she was believed to guarantee fertility (frogs lay between 20,000 and 25,000 eggs). This fact may go a long way toward accounting for the appearance of an animal spouse in folklore (in our case, a frog prince in German and a frog princess in Russian) if we assume that the Egyptian beliefs became known in Ancient Greece and later in Rome, from where they spread and mutated in the rest of Europe. In any case, frogs played a role in the initiation of Dionysus, a god of fertility.

Such is my tale. Comments are welcome.

Featured Image: Biblical illustration of Book of Exodus Chapter 9 by Jim Padgett, Distant Shores Media/Sweet Publishing. CC3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

April 2, 2024

Is humanity a passing phase in evolution of intelligence and civilisation?

Is humanity a passing phase in evolution of intelligence and civilisation?

“The History of every major Galactic Civilization tends to pass through three distinct and recognizable phases, those of Survival, Inquiry and Sophistication…”

Douglas Adams, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to The Galaxy (1979)

“I think it’s quite conceivable that humanity is just a passing phase in the evolution of intelligence.”

Geoffrey Hinton (2023)

In light of the recent spectacular developments in artificial intelligence (AI), questions are now being asked about whether AI could present a danger to humanity. Can AI take over from us? Is humanity a passing phase in the evolution of intelligence and civilisation? Let’s look at these questions from the long-term evolutionary perspective.

Life has existed on Earth for more than three billion years, humanity for less than 0.01% of this time, and civilisation for even less. A billion years from now, our Sun will start expanding and the Earth will soon become too hot for life. Thus, evolutionarily, life on our planet is already reaching old age, while human civilisation has just been born. Can AI help our civilisation to outlast the habitable Solar system and, possibly, life itself, as we know it presently?

Defining life is not easy, but few will disagree that an essential feature of life is its ability to process information. Every animal brain does this, every living cell does this, and even more fundamentally, evolution is continuously processing information residing in the entire collection of genomes on Earth, via the genetic algorithm of Darwin’s survival of the fittest. There is no life without information.

It can be argued that until very recently on the evolutionary timescale, i.e. until human language evolved, most information that existed on Earth and was durable enough to last for more than a generation, was recorded in DNA or in some other polymer molecules. The emergence of human language changed this; with language, information started accumulating in other media, such as clay tablets, paper, or computer memory chips. Most likely, information is now growing faster in the world’s libraries and computer clouds than in the DNA of all genomes of all species.

We can refer to this “new” information as cultural information as opposed to the genetic information of DNA. Cultural information is the basis of a civilisation; genetic information is the basis of life underpinning it. Thus, if genetic information got too damaged, life, cultural information, and civilisation itself would disappear soon. But could this change in the future? There is no civilisation without cultural information, but can there be a civilisation without genetic information? Can our civilisation outlast the Solar system in the form of AI? Or will genetic information always be needed to underpin any civilisation?

For now, AI exists only as information in computer hardware, built and maintained by humans. For AI to exist autonomously, it would need to “break out” of the “information world” of bits and bytes into the physical world of atoms and molecules. AI would need robots maintaining and repairing the hardware on which it is run, recycling the materials from which this hardware is built, and mining for replacement ones. Moreover, this artificial robot/computer “ecosystem” would not only have to maintain itself, but as the environment changes, would also have to change and adapt.

Life, as we know it, has been evolving for billions of years. It has evolved to process information and materials by zillions of nano-scale molecular “machines” all working in parallel, competing as well as backing each other up, maintaining themselves and the ecosystem supporting them. The total complexity of this machinery, also called the biosphere, is mindboggling. In DNA, one bit of information takes less than 50 atoms. Given the atomic nature of physical matter, every part in life’s machinery is as miniature as possible in principle. Can AI achieve such a complexity, robustness, and adaptability by alternative means and without DNA?

Although this is hard to imagine, cultural evolution has produced tools not known to biological evolution. We can now record information as electron density distribution in a silicon crystal at 3 nm scale. Information can be processed much faster in a computer chip than in a living cell. Human brains contain about 1011 neurons each, which probably is close to the limit how many neurons a single biological brain can contain. Though this is more than computer hardware currently offers to AI, for future AI systems, this is not a limit. Moreover, humans have to communicate information among each other via the bottleneck of language; computers do not have such a limitation.

Where does this all leave us? Will the first two phases in the evolution of life—information mostly confined to DNA, and then information “breaking out” of the DNA harness but still underpinned by information in DNA, be followed by the third phase? Will information and its processing outside living organisms become robust enough to survive and thrive without the underpinning DNA? Will our civilisation be able to outlast the Solar system, and if so, will this happen with or without DNA?

To get to that point, our civilisation first needs to survive its infancy. For now, AI cannot exist without humans. For now, AI can only take over from us if we help it to do so. And indeed, among all the envisioned threats of AI, the most realistic one seems to be deception and spread of misinformation. In other words, corrupting information. Stopping this trend is our biggest near-term challenge.

Feature image by Daniel Falcão via Unsplash.

April 1, 2024

The hidden toll of war

During war, the news media often focus on civilian injuries and deaths due to explosive weapons. But the indirect health impacts of war among civilians occur more frequently—often out of sight and out of mind.

These indirect impacts include communicable diseases, malnutrition, exacerbations of chronic noncommunicable diseases, maternal and infant disorders, and mental health problems. They are caused primarily by forced displacement of populations and by damage to civilian infrastructure, including farms and food supply systems, water treatment plants, healthcare and public health facilities, and networks for electric power, communication, and transportation.

Increasingly, damage to civilian infrastructure is caused by targeted attacks—as a strategy of war, resulting in reduced access to food, safe drinking water, healthcare, and shelter. When water treatment plants and supply lines are damaged during war, people often have no choice but to drink water from sources that may be contaminated with microorganisms or toxic substances. Healthcare facilities have been increasingly targeted during war; for example, during the first 18 months of the war in Ukraine, there were 1,014 attacks on healthcare facilities, which injured and killed many patients and healthcare workers, and caused much damage, which reduced access to healthcare for many people.

Globally, there are now more than 108 million people who have been displaced from their homes, many as a result of war. Most of these displaced people have been internally displaced within their own countries, often facing greater health and security risks than refugees, who have fled to other countries. And during war, many more people live in continual fear that they may be forcibly displaced.

Major categories of communicable diseases during war include diarrheal diseases and respiratory disorders. These diarrheal diseases result mainly from decreased access to safe drinking water and reduced levels of sanitation and hygiene, leading to increased fecal-oral transmission of bacterial and viral agents. Among respiratory disorders, measles is of great concern because it is highly contagious and associated with high mortality rates among unimmunized children. Another major concern is tuberculosis, which can spread easily among war-affected populations and is difficult to treat without continuity of care. Crowding in bomb shelters, refugee camps, and other locations during war facilitates the spread of both diarrheal diseases and respiratory disorders. Disruption of public health services leads to reduced access to immunizations and reduced resources to investigate and control outbreaks of communicable disease. During war, bacterial resistance to antibiotics increases because people have decreased access to antibiotics and therefore take inappropriate antibiotics or shortened courses of treatment.

Malnutrition often increases during war, thereby increasing the risks of acquiring and dying from many communicable diseases. Infants and children are at greatest risk of becoming malnourished and suffering from its adverse health consequences. Micronutrient deficiencies during pregnancy can lead to birth defects. And severe malnutrition during war can increase the risk of hypertension, coronary artery disease, and diabetes in later life.

During war, exacerbations of preexisting cases of noncommunicable disease increase, mainly because of reduced access to medical care and medications for treating common chronic diseases. For example, a survey by the World Health Organization in Ukraine in 2022 found that about half of the respondents experienced reduced access to medical care and almost one-fourth could not acquire necessary medications that they needed. Without these medications, people with hypertension were at increased risk of myocardial infarction and stroke, people with asthma were at increased risk of life-threatening attacks, people with diabetes were at increased risk of serious complications, and people with epilepsy were at increased risk of seizures.

War exerts adverse effects on reproductive health. Access to prenatal care, postpartum and neonatal care, and reproductive health services are frequently decreased. As a result, complications of pregnancy, including maternal deaths, occur more frequently and there are increased rates of infant deaths and of infants being born prematurely or with low birthweight.

Mental and behavioral disorders occur more frequently during war, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression and anxiety, alcoholism and drug abuse, and suicide. There are many contributing factors to increasing the risk of these disorders, including physical and sexual trauma, witnessing of atrocities, forced displacement, family separation, deaths of loved ones, loss of employment and education, and uncertainty about the future.

Violations of human rights and international humanitarian law occur frequently during war. In addition to those already mentioned, these violations include gender-based violence, summary executions, kidnapping, denial of humanitarian aid, and use of indiscriminate weapons, such as antipersonnel landmines.

The possible use of nuclear weapons represents a profound threat whenever nuclear powers are engaged in war, partly because these weapons could be launched by accident or because of misinterpretation or miscommunication. Even a small nuclear war could cause huge numbers of deaths and severe injuries and could lower temperatures globally, leading to widespread famine.

Environmental damage during war can result from chemical contamination of air, water, and soil; presence of landmines and unexploded ordnance; release of ionizing radiation from nuclear power plants or conventional weapons containing radioactive materials (“dirty bombs”); destruction of the built environment; and damage to animal habitats and ecosystems. In addition, war and the preparation for war consume large amounts of fossil fuels, which generate greenhouse gases, which, in turn, cause global warming.

Protection of civilians and civilian infrastructure during war and improved humanitarian assistance can reduce the indirect health impacts of war. But the only way to eliminate these impacts is to eliminate war. The risk of war can be reduced by resolving disputes before they turn violent; by reducing the root causes of war, such as socioeconomic inequities, militarism, ethnic and religious hatred, poor governance, and environmental stress; and by strengthening the infrastructure for peace. Peace can be achieved and sustained by rehabilitating nations and reintegrating people after war has ended, strengthening civil society, promoting the rule of law, ensuring citizen participation, and holding aggressors accountable.

Barry S. Levy is the author of From Horror to Hope: Recognizing and Preventing the Health Impacts of War (Oxford University Press, 2022). He is an Adjunct Professor of Public Health at Tufts University School of Medicine and a past president of the American Public Health Association.

Featured image: Markus Spiske via Unsplash , public domain.

March 29, 2024

England and Egypt in the early middle ages: the papal connection

England and Egypt in the early middle ages: the papal connection

When the Venerable Bede (d. 735) looked out from his Tyneside monastery across the North Sea, over the harbour at Jarrow Slake to which ships brought communications, wares, and human traffic from Europe and the Mediterranean—how then did he picture Rome and the papacy, the city and institution he thought so central to English and even world history? His grasp of its visual culture cannot have been great. We know that Bede never saw Rome (in fact, he never saw any city or town). Our usual reference points of its basilicas, shrines, walls and mosaics—indeed, its sheer urban and suburban mass—cannot have meant much to him.

He surely saw books from Rome, and perhaps church vestments and other textiles, although how distinctively ‘Roman’ these looked we do not know. He made a great deal of the relics of Roman saints brought to his island. But the kinds of relics of which he spoke were hardly spectacular: tiny wrappings of cloth, filled with dust, tagged with plain, fingernail-sized labels—to the modern eye, they resemble more covert bundles of narcotics than tokens of God’s elect on earth. Rather, the main visual medium through which Bede and many others in the early Middle Ages must have experienced Rome was through the physical format itself of the papal decrees which his monastery and wider political community received. Throughout the first millennium, these papal letters were not routine bureaucratic documents, and they would have not gone unnoticed. They took the form of enormous, metres-long scrolls of Egyptian papyrus.

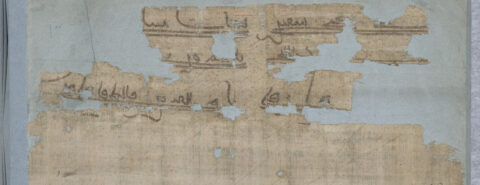

So fragile is papyrus that no more than about two dozen of the original letters sent by early medieval popes survive anywhere in Europe (the others, in their thousands, have come down to us via later copies and citations). The few we retain, however, indicate that the visual message which opened up before the eyes of those who unrolled these documents firmly located Rome, the papacy, and the mainstream of the Christian world within a culture which was distinctively eastern Mediterranean. One such survival appears on the cover of my recent book, England and the Papacy in the Early Middle Ages.

The artefact now sits in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, where it was sliced into eight fragments by an overzealous librarian in the nineteenth century. It records the intervention of Pope John VIII into the legal privileges of the monastery of Tournus (eastern France) in the year 876. Textually, it is fairly mundane. Yet the external features of this papal manuscript are extraordinary when compared to what else we know of other European medieval documents. Like other papal survivals, it is huge—an amazing 3.2 metres in length (and specimens of up to 7 metres survive elsewhere). Like other surviving scrolls, it is written in a strange, seemingly deliberately baffling Roman script. And the use of papyrus, not parchment, as a format is by itself astonishing: this was a medium definitively phased out of use across most of Europe in the seventh century. By the ninth century, stocks must have been very difficult to obtain. The Tournus letter’s most remarkable feature, however, is its grand opening statement. This is not in Latin at all, nor by a papal notary. Instead, the letter begins with a half-metre-wide proclamation in Arabic, and its scribe was presumably Egyptian.

What this Arabic actually says is contested. The extant script is almost undecipherable; a , an early-to-mid-ninth-century finance director of Abbasid Egypt, may or may not be secure. In any case, its scribe probably added the text to the plain sheet of freshly manufactured papyrus in Egypt, the caliphal province which held a virtual monopoly on the papyrus industry. This was completely standard procedure, inherited from the Roman Empire. Such ‘protocols’ are found elsewhere on Byzantine and Arabic papyri. Essentially, they certified that rolls of new papyri, whose manufacture was state-supervised, had passed through the right authorities before distribution. A rough modern-day analogy might be the duty-stamps found on exported whiskey and cigarettes.

From Egypt, some stocks must have made it to Rome. But that is where things get weird. One would, I think, expect the papal notaries who prepared this magnificent, highly formalised document for Tournus to have at least trimmed off this half-metre block of Arabic text inserted by the Abbasid functionaries. On the contrary, the Arabic is retained in full, and is by some distance the single largest graphic element on the letter, where it stands out as pivotal to its visual power. It was surely kept on purpose. If those handling the letter could not read giant sweeps of official, Arabic chancery script, then they must have still recognised its connotations. At the head of the document, it signalled the claims of Rome and the papacy (and with them, the letter’s recipients) to a privileged hyperconnectivity with a universal Christian culture that stretched far beyond the bounds of the Latin west, and even touched upon the aesthetics, technologies, and trade networks of Islamic civilisation. This Arabic contribution to the document was something to be prized, not neglected.

There’s no reason to believe that this would have been the only instance where such an Arabic protocol became embedded into a papal letter or decree. Rates of survival are too poor for us to assert that this single case was exceptional. Nor does the fact that later copyists failed to note such features when transcribing the many papyri which we have lost mean anything: even modern editors of the Tournus document have not always bothered. Hence my—slightly provocative—choice of this letter for a French recipient for the cover of England and the Papacy in the Early Middle Ages. I think we should take very seriously the possibility that a great many of the lost original papal letters for early medieval England would have looked just like this: that the archives of Canterbury, York, Wearmouth-Jarrow and Glastonbury could well have counted documents emblazoned with the Arabic calligraphy of Umayyad and Abbasid officials as their most prized possessions—that is, as both sacred texts issued by the pope, and as key witnesses to their legal title.

When the early medieval English imagined Rome and the papacy, then, they may have often done so through the prism of what remained, for many, their most immediate sensory experience of its distant allure. This was an experience which none of us would associate with Rome today. To experience the popes and their city from afar meant to gaze upon metres-long rolls of an unfamiliar, precious, Egyptian fabric, and to watch them being unfurled in a church, palace, or place of assembly, to reveal decrees penned in a strange southern Italian script, sometimes even an Arabic one that looked stranger still. Was this the Rome of Bede, Offa, Wulfstan, Æthelred? If we want to take a more radical approach to thinking about English religion and politics in the first millennium—one which expands our sense of the ‘Anglo-Saxon’ worldview beyond the familiar Insular tropes and images and destabilises our weary modern assumptions about what its Christian identity involved—then this seems to me like a good place to start.

Feature image: gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France. Département des Manuscrits. Latin 8840.

March 28, 2024

Thinking disobediently?

A person who “thinks disobediently” can be invigorating, maddening, or both. The life and writings of Henry David Thoreau have provoked just such mixed reactions over time, scorned by some; cherished by others. What seems bracingly invigorating can also seem an off-putting mannerism.

That’s also a significant reason why Thoreau lingered in provincial obscurity during his life but rose to iconic status after death to become one of the few figures in American literary history besides Mark Twain and Ernest Hemingway to achieve something like folk hero status—at least for many. Against-the-grain thinkers are often easier to take from a distance than upfront. Socrates, Nietzsche, and Gandhi are some others who come to mind.

Thoreau’s mentor Ralph Waldo Emerson observed that “first instinct upon hearing a proposition was to controvert it.” Emerson usually found this cantankerousness energizing, but he also wearied of it; and so, to a much greater extent, did more conventional-minded folk, especially if they’d never seen Thoreau’s sweeter and more vulnerable side, as Emerson had. His author-physician friend Oliver Wendell Holmes, who had little time for willful idiosyncrasy, dismissed Thoreau as an Emerson clone who “insisted in nibbling his asparagus at the wrong end.” In Thoreau’s writing as well, we often find him insisting on the importance of such gestures as rejecting the gift of a doormat for his Walden cabin because “it is best to avoid the beginnings of evil.”

This dogged staunchness repelled even some who were closer to him, like one neighbor who quipped that she would no more think of taking Thoreau’s arm than the arm of an elm tree. Never mind that still others who knew him more intimately disagreed, especially among the younger generation of Concord like Louisa May Alcott and Emerson’s son, who remembered him as a kindly playfellow and guide. Standoffish resistance, with a satirical bite, was the face he tended to present to the adult world.

This side of Thoreau, however, is also key to the special force and bite of his writing, which for many latter-day readers has made his writing seem more vibrant and provocative over time than Emerson’s more abstract prose. Judged by their writings alone, Thoreau emerges as the far more memorable flesh-and-blood figure, Emerson by contrast as a kind of recording consciousness. Even Thoreau’s cranky niggling can seem like lovable eccentricity. When I put the question, “Which of the two would you rather room with?” to students who’ve read them both extensively, their first impulse is to choose Thoreau, although, on second thought, they grant that Emerson would have been easier to get along with.

Thoreau scholars also face a version of this problem. Many of us, myself included, were first drawn to Thoreau in years past by his ringing idealistic denunciations of the social and political status quo (“Under a government which imprisons any unjustly, the only place for a just man is also a prison,” etc.) In addition to their sheer charismatic vehemence, such pronouncements may ignite a feeling of special kinship in those who also feel themselves on the margins of society, as aspiring academics often do. The autobiographical persona in Thoreau’s writing evokes the sense of being invited into a select circle of intimacy above or apart from the ordinary herd, such as what e. e. cummings conjures up in the preface to an edition of his collected poems: These poems “are written for you and for me and are not for mostpeople [sic].”

Only later does one realize that Thoreau might have scorned most who write articles and books about him as obtuse pedants. But that awakening may also have the salutary effect of making a scrupulous Thoreauvian less addicted to his or her pet theories about who the real Thoreau was, and more wary of making “authoritative” claims about the essence of his personhood or writing.

That said, the defining arenas of Thoreau’s disobedient thinking are unmistakable. Individual conscience is a higher authority than statute law or moral consensus. True wildness can be found at the edges of your hometown. Scientific investigation of natural phenomenon is formulaic without sensuous immersion in the field. Religious orthodoxies of one’s time or any time are tribalistic distortions of the animating energies whose epicenter lies, if anywhere, in untutored intuition or the natural world, not human institutions.

What gives these and other Thoreauvian heterodoxies their special bite is not so much how he lived but how he wrote. Many have practiced a more rigorous voluntary simplicity than Thoreau did during his two-plus years at Walden, often for far longer stretches of time and in places far more wild. Many have suffered for conscience’s sake far longer and far more agonizingly than his one-night incarceration for tax refusal. But no such heroes of nonconformity managed to write the likes of Walden and “Civil Disobedience,” which since Thoreau’s death have become classics of world literature and have helped inspire many more thoroughgoing acts of conscientious withdrawal, political resistance, and environmental activism.

In order to make sense of how these—and other—Thoreau works have had such impact, a good place to start is Thoreau’s talent for arresting assertions, often directed as much to himself as to others, that set you back, make you think, urge you on. Such as: “Any man more right than his neighbors constitutes a majority of one already”; “If I repent of anything, it is very likely to be my good behavior”; “For the most part, we are not what we are, but in a false position”; or “How vain it is to sit down to write when you have not stood up to live!” This, however, is only a starting point for a deeper understanding of the motions of this disobedient thinker’s mind. For that, there’s no substitute for a careful examination of the works themselves. That’s what I’ve striven to do in Henry David Thoreau: Thinking Disobediently.

Feature image by Chris Liu-Beers via Unsplash.

March 27, 2024

A jumping frog and other creatures of etymological interest

A jumping frog and other creatures of etymological interest

Our readers probably expect this post to deal with Mark Twain’s first famous story. Alas, no. My frog tale is, though mildly entertaining, more somber and will certainly not be reprinted from coast to coast or propel me to fame. In the past, I have written several essays about animal names. One of them examined toad. Here too, the toad will make its appearance, but before it does so, we should keep in mind that animal names—be it horse or sparrow, shark or rabbit—are often among the most obscure words from an etymological point of view. Frog is no exception. Consider Greek barakahs (origin unknown; borrowed from some other language?).

Frogs are famous for their long hind legs and jumping. Consequently, we may expect them to be called jumpers. And this sometimes happens. For example, in Russian, lyagushka “frog” (stress on the second syllable) is derived from the word for “hip” (liazhka), obviously with reference to the creature’s ability to hop and leap. One does not have to be a historical linguist to recognize the connection. But strangely, this transparency is rare. To increase our confusion, we find that even across related languages, the word for the frog is sometimes applied to the toad.

Numerous animal names go back to the sound those animals make. Supposedly, Latin rana “frog” is sound–imitative. I am not quite sure what frogs “say.” English speakers hear croak-croak. Does one also hear ran-ran from them? In Russian, frogs go kva-kva, and in German, kvak-kvak. People’s attempts to imitate animals sounds are often puzzling: compare oink-oink (English) and khriu–khriu (Russian). It almost appears that English and Russian pigs have inherited different languages. German pigs, with their grunz–grunz, should feel more comfortable in the east that in the English-speaking world. The internet informs us that frogs whistle, croak, “ribbit” (an American verb, seemingly coined for this purpose only), peak, cluck, bark, and grunt—quite a symphony (as regards grunt, compare grunz-grunz; German z has the value of ts). As we will soon see, the origin of English frog is “not yet settled” (quoted from my favorite English dictionary by Henry Cecil Wyld). What if frog is a sound-imitating word? Perhaps those who coined frog heard frog–frog, along with croak-croak, kva-kva, and ran-ran? Correct etymologies are usually simple, but it does not follow that every simple etymology is correct. The Old English for “frog” was frogga, a hypocoristic formation, similar to docga “dog” (dog is a word of “contested etymology”: see my posts on May 4, May 11, May 18, and June 8, 2016). In the adjective hypocoristic, cor– means “child” (from Greek kóros “child”). Both dog and frog may be ancient baby words.

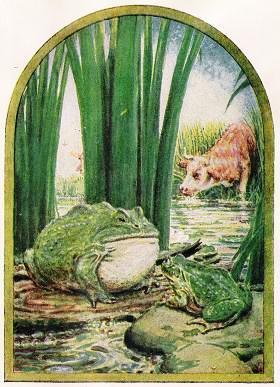

If you are a frog, don’t try to become an ox. Fables in Thyme for Little Folks by John Rae, Project Gutenberg, via Wikimedia Commons. CC1.0.

If you are a frog, don’t try to become an ox. Fables in Thyme for Little Folks by John Rae, Project Gutenberg, via Wikimedia Commons. CC1.0.The “adult” root of dog (if it existed) is unknown. Besides, dog is almost isolated in English, and to increase our bafflement, the Old English form of dog occurred most rarely in the recorded texts. Frog is less obscure than dog, because Old English words for “frog” did turn up in early medieval prose. They are forsc, frosc, and frox. Obviously, they are different forms of the same noun, whose pronunciation fluctuated. In Middle English, we find the variants frūde (with ū, a long vowel) and froude, borrowed from Scandinavian: the Old Norse (that is, Old Icelandic) for “frog” was froskr, frauki, and frauðr (ð = th in Modern English this), in addition to frauki. One can see that the name for “frog” had several variants not only in English. Some fluctuation was due to phonetic reasons. For instance, in forsc and frosc, the vowel and consonant played leapfrog (I am genuinely sorry for the pun, but the temptation was too strong). This game is called metathesis. When r is entailed, metathesis is especially common: compare English burn and German brennen. Both bird and horse once sounded as brid and hros.

Frogs’ voices did not appeal to Ancient Greeks. Frogs of the Aristophanes Playbill by Trinity College Dramatic Society, via Wikimedia Commons.

Frogs’ voices did not appeal to Ancient Greeks. Frogs of the Aristophanes Playbill by Trinity College Dramatic Society, via Wikimedia Commons.If frog was not a production of the nursery or sound imitation, what could its origin be? Naturally, etymologists searched for some similar word that might provide a clue to the animal name. One such word is froth. If the match is good, the reference must have been to the frog’s slimy skin. The noun froth probably existed in Old English, but only a related verb has been recorded. The noun we today know is a fourteenth-century borrowing from Old Norse. The connection froth ~ frog is not particularly appealing, and hardly anyone supports it today. Dutch vors, Old English frosk (see it above), and Old Icelandic frauki (assuming that they all go back to a so-called protoform) seem to have developed from some early root like frusk-, which corresponds to non-Germanic prusk-. It will be remembered that the non-Germanic (that is, Greek, Latin, Celtic, Slavic, and so forth) match for f is Germanic p: compare English father, and Latin pater (the words are certainly related). This regularity is part is part of what is known as the Germanic Consonant Shift, or Grimm’s Law.

In prusk-, -sk might be a suffix, which leaves us with the root pru-. This root was found in the Russian verb pry-gat’ “to jump.” No correspondence could be better (frogs emerged as jumpers), but the entire procedure looks like an attempt to justify a forgone conclusion: since frogs are jumpers, let us try to find some word meaning “jump, spring, leap” and connect the two. Many good dictionaries accept the frog ~ prygat’ solution, but I share Elmar Seebold’s skepsis on this score (Seebold is the editor of the main etymological dictionary of German).

We’ll leave our frog in midair until next week and remember that English has another name for this anurous amphibian, namely, pad or paddock (-ock is a suffix). Perhaps some light on the origin of frog will fall from the history of pad? Pad first meant “toad”; pad “a small cushion, etc.” corresponds to northern German pad “the sole of the foot.” To paddle is almost a synonym for toddle (of unknown origin!). After years of hesitation, etymologists seem to have reached a state of unenthusiastic agreement that despite all difficulties connected with the origin of path, the word reflects the tread of the walker going pad ~ pad ~ pad. All over the world, people and animals are said to go pad-pad, pat-pat, and top-top. Frogs jump, while toads move slowly, that is, go pad-pad. I believe that pad “toad” is onomatopoeic (sound-imitating), and so are, most probably, pad– in paddle and tod– in toddle. There is also English dialectal tod “fox.” Since among other things, tod means “a weight used for wool; a bushy mass,” couldn’t tod “fox” get its name from the animal’s bushy tail? Be that as it may, pad and tod have nothing to do with frog, and after this long digression, we are none the wiser.

Some creatures are born tailless, others have wonderful tails, but all are perfect.

Some creatures are born tailless, others have wonderful tails, but all are perfect.Images: (1) Public domain via Pexels, (2) Internet Archive Book Images via Flickr, (3) Plains Spadefoot, Alberta by Andy Teucher via Flickr. CC2.0. (4) Creeping fox by Eric Kilby via Flickr. CC2.0.

The main conclusion of this part of our investigation is that in dealing with the names of the frog and the toad, one should be on the lookout for expressive formations. Toads and frogs have occupied the attention of our ancestors much more than, in our opinion, they deserve. Anticipating the discussion next week, it should be mentioned that there also is northern German pogge “frog,” which, despite its similarity with pad, cannot be dismissed without further discussion (pogge resembles frog!), and we’ll soon see a promising way of dealing with this word. Wait for the continuation next week!

Feature image by Biodiversity Heritage Library via Flickr (Public Domain).

Why decolonization and inclusion matter in linguistics

Why decolonization and inclusion matter in linguistics

As sociolinguists, we have centered social justice in our research, teaching, and administrative work for many years. But as with many other academics, this issue took on renewed collective urgency for us in the context of the events of 2020, from toxic politics and policies at the federal level, to state-sanctioned anti-Black violence and the ensuing racial reckoning, to the Covid-19 pandemic and the many inequities it exposed and heightened.

Troubled by the often-misinformed efforts to make institutional change that we saw around us, we wanted to take action that was both specific to our disciplinary context and wide-reaching in its effects. We started with an article in the flagship linguistics journal, Language, calling for the centering of racial justice within the discipline. That article was the lead piece in the journal’s Perspectives section and was accompanied by a range of responses from linguists worldwide, which we responded to in turn.

We wrote with the hope that institutional change could start from the individual and (especially) collective actions of linguists. We were also motivated by the hope that the discipline our students will enter will be radically different from the one that we have spent our careers within. This hope fueled our work for the next several years, as we collaborated with linguists within and beyond linguistics departments and throughout the academy to create concrete, specific, and action-centered models for how to do the work necessary to transform the discipline. The results of this intensive collaborative process are two companion volumes, Decolonizing Linguistics and Inclusion in Linguistics, and their websites, which provide additional information and resources.

Some linguists, particularly those for whom linguistics is structured and whom it best serves, may be asking themselves, “What’s so bad about linguistics in its current form?” Many linguists we interacted with as we embarked on this project were defensive, baffled, or even outright hostile. Fortunately, many others were curious and eager to learn how the discipline could do better and what they could do to help. Most importantly, the people for whom we do this work—those who have been made to feel unwelcome in linguistics and who have been shut out, pushed out, or relegated to the disciplinary margins, as well as those who have succeeded despite rather than because of linguistics-as-usual—understood and welcomed our project. Many of these current, former, and would-be linguists have been engaged in like-minded efforts of their own.

Some critics see our work as “politicizing” linguistics. But these commenters miss the point that linguistics (and academia) has always been political. The discipline has its roots in empire and the colonizing practices of categorizing and classifying languages in order to control those who use them. As the discipline has taken shape over the centuries to the present day, linguistics has become a field limited by its own exclusionary practices and ideologies—a field that, in our view, is simply too small. In Decolonizing Linguistics and Inclusion in Linguistics, we envision and work to build a linguistics that is capacious and welcoming, particularly to those whose lived experiences give them fresh and much-needed insights into the kinds of questions linguistics should be asking, the kinds of methods it should be using, and the kinds of real-world impacts it should be making.

Inclusion in linguisticsMost linguists are familiar with the concept of inclusion through institutional discourse in academia and elsewhere, particularly the acronym DEI (diversity, equity, inclusion) or its many variants. Too often, however, inclusion is used to mean recruiting members of formerly excluded groups into often hostile institutions, without making significant changes to the workings of the institutions themselves. True inclusion is not a matter of making space within existing institutions for new people to do the same old thing. Instead, true inclusion requires the transformation not only of who is in institutional spaces but what they do, how, and why. Transformation demands that we ask ourselves who is and isn’t present in linguistics, whether they have full and equitable access, and whether the community of linguists will value their full humanity, rather than treating them merely as sources of linguistic data or as token representatives and spokespersons for the groups to which they belong.

Inclusion in Linguistics offers abundant examples of how linguists can and already are creating genuine inclusion within the discipline. The authors challenge limited notions of who gets to be included, calling attention to a wide range of groups who remain marginalized on the basis of race and ethnicity, gender identity, disability, geography, language, class and caste, and more. The authors issue a powerful call for a linguistics that does not simply make space for but purposefully centers those who have been excluded. We collectively urge linguists to think bigger, to abandon long-cherished ideological investments in what is and isn’t legitimate within linguistics, and to build a discipline that doesn’t hide in the ivory tower but engages with the world and makes it a better place.

Decolonizing linguisticsCompared to inclusion, decolonization may be a less familiar concept to many linguists. Some academics in the US may have first encountered the idea, along with related concepts like settler colonialism, through student activism on their campus in recent years and months. (In fact, the New York Times recently published an explainer on the term settler colonialism, assuming—no doubt correctly—that its predominantly white, liberal, and highly educated readership is not well versed in decolonial theory and activism.)

We chose the title Decolonizing Linguistics to invoke the long and ongoing history of linguists’ global academic exploitation of Black and Indigenous people and the discipline-based extraction of their languages for professional and economic gain. Contributors identify some of the forms of colonialism that linguistics has taken and continues to take. We emphasize the importance of Black-centered and Indigenous epistemologies and methodologies in undoing colonizing structures. We also highlight community-driven collaborative projects that provide a comprehensive picture of the powerful social and scholarly impacts of an unsettled, decolonized linguistics.

Both volumes offer specific roadmaps and pathways for how to advance social justice, through programs, partnerships, curricula, and other initiatives. Our work is a necessary first step toward institutional and disciplinary change: a linguistics built by, around, and for groups that have confronted colonization, oppression, and exclusion—that is, precisely the people whose languages so often fascinate linguists—is also a linguistics that prioritizes the new ideas and practices that these groups bring to the discipline and recognizes these new directions as precisely where linguistics needs to go.

We do not consider Inclusion in Linguistics and Decolonizing Linguistics as definitive statements but rather as an invitation for others to join us in ongoing conversations. We invite linguistics scholars and students, educators and higher education leaders, around the world to engage with the ideas in both volumes with an eye toward what you can do in your own local context, what we have inevitably left out, and how you might build on, adapt, and push us forward to create the kind of inclusive, decolonized, and socially just linguistics that you would like to be part of.

Featured image by Fons Heijnsbroek, abstract-art via Unsplash.

Why decolonization and inclusion matter in linguistics?

Why decolonization and inclusion matter in linguistics?

As sociolinguists, we have centered social justice in our research, teaching, and administrative work for many years. But as with many other academics, this issue took on renewed collective urgency for us in the context of the events of 2020, from toxic politics and policies at the federal level, to state-sanctioned anti-Black violence and the ensuing racial reckoning, to the Covid-19 pandemic and the many inequities it exposed and heightened.

Troubled by the often-misinformed efforts to make institutional change that we saw around us, we wanted to take action that was both specific to our disciplinary context and wide-reaching in its effects. We started with an article in the flagship linguistics journal, Language, calling for the centering of racial justice within the discipline. That article was the lead piece in the journal’s Perspectives section and was accompanied by a range of responses from linguists worldwide, which we responded to in turn.

We wrote with the hope that institutional change could start from the individual and (especially) collective actions of linguists. We were also motivated by the hope that the discipline our students will enter will be radically different from the one that we have spent our careers within. This hope fueled our work for the next several years, as we collaborated with linguists within and beyond linguistics departments and throughout the academy to create concrete, specific, and action-centered models for how to do the work necessary to transform the discipline. The results of this intensive collaborative process are two companion volumes, Decolonizing Linguistics and Inclusion in Linguistics, and their websites, which provide additional information and resources.

Some linguists, particularly those for whom linguistics is structured and whom it best serves, may be asking themselves, “What’s so bad about linguistics in its current form?” Many linguists we interacted with as we embarked on this project were defensive, baffled, or even outright hostile. Fortunately, many others were curious and eager to learn how the discipline could do better and what they could do to help. Most importantly, the people for whom we do this work—those who have been made to feel unwelcome in linguistics and who have been shut out, pushed out, or relegated to the disciplinary margins, as well as those who have succeeded despite rather than because of linguistics-as-usual—understood and welcomed our project. Many of these current, former, and would-be linguists have been engaged in like-minded efforts of their own.

Some critics see our work as “politicizing” linguistics. But these commenters miss the point that linguistics (and academia) has always been political. The discipline has its roots in empire and the colonizing practices of categorizing and classifying languages in order to control those who use them. As the discipline has taken shape over the centuries to the present day, linguistics has become a field limited by its own exclusionary practices and ideologies—a field that, in our view, is simply too small. In Decolonizing Linguistics and Inclusion in Linguistics, we envision and work to build a linguistics that is capacious and welcoming, particularly to those whose lived experiences give them fresh and much-needed insights into the kinds of questions linguistics should be asking, the kinds of methods it should be using, and the kinds of real-world impacts it should be making.

Inclusion in linguisticsMost linguists are familiar with the concept of inclusion through institutional discourse in academia and elsewhere, particularly the acronym DEI (diversity, equity, inclusion) or its many variants. Too often, however, inclusion is used to mean recruiting members of formerly excluded groups into often hostile institutions, without making significant changes to the workings of the institutions themselves. True inclusion is not a matter of making space within existing institutions for new people to do the same old thing. Instead, true inclusion requires the transformation not only of who is in institutional spaces but what they do, how, and why. Transformation demands that we ask ourselves who is and isn’t present in linguistics, whether they have full and equitable access, and whether the community of linguists will value their full humanity, rather than treating them merely as sources of linguistic data or as token representatives and spokespersons for the groups to which they belong.

Inclusion in Linguistics offers abundant examples of how linguists can and already are creating genuine inclusion within the discipline. The authors challenge limited notions of who gets to be included, calling attention to a wide range of groups who remain marginalized on the basis of race and ethnicity, gender identity, disability, geography, language, class and caste, and more. The authors issue a powerful call for a linguistics that does not simply make space for but purposefully centers those who have been excluded. We collectively urge linguists to think bigger, to abandon long-cherished ideological investments in what is and isn’t legitimate within linguistics, and to build a discipline that doesn’t hide in the ivory tower but engages with the world and makes it a better place.

Decolonizing linguisticsCompared to inclusion, decolonization may be a less familiar concept to many linguists. Some academics in the US may have first encountered the idea, along with related concepts like settler colonialism, through student activism on their campus in recent years and months. (In fact, the New York Times recently published an explainer on the term settler colonialism, assuming—no doubt correctly—that its predominantly white, liberal, and highly educated readership is not well versed in decolonial theory and activism.)

We chose the title Decolonizing Linguistics to invoke the long and ongoing history of linguists’ global academic exploitation of Black and Indigenous people and the discipline-based extraction of their languages for professional and economic gain. Contributors identify some of the forms of colonialism that linguistics has taken and continues to take. We emphasize the importance of Black-centered and Indigenous epistemologies and methodologies in undoing colonizing structures. We also highlight community-driven collaborative projects that provide a comprehensive picture of the powerful social and scholarly impacts of an unsettled, decolonized linguistics.

Both volumes offer specific roadmaps and pathways for how to advance social justice, through programs, partnerships, curricula, and other initiatives. Our work is a necessary first step toward institutional and disciplinary change: a linguistics built by, around, and for groups that have confronted colonization, oppression, and exclusion—that is, precisely the people whose languages so often fascinate linguists—is also a linguistics that prioritizes the new ideas and practices that these groups bring to the discipline and recognizes these new directions as precisely where linguistics needs to go.

We do not consider Inclusion in Linguistics and Decolonizing Linguistics as definitive statements but rather as an invitation for others to join us in ongoing conversations. We invite linguistics scholars and students, educators and higher education leaders, around the world to engage with the ideas in both volumes with an eye toward what you can do in your own local context, what we have inevitably left out, and how you might build on, adapt, and push us forward to create the kind of inclusive, decolonized, and socially just linguistics that you would like to be part of.

Featured image by Fons Heijnsbroek, abstract-art via Unsplash.

March 26, 2024

American Exchanges: Third Reich’s Elite Schools

American Exchanges: Third Reich’s Elite Schools

In the summer of 1935, an exchange programme between leading American academies and German schools, set up by the International Schoolboy Fellowship (ISF), was hijacked by the Nazi government. The organization had been set up in 1927 by Walter Huston Lillard, the principal of Tabor Academy in Marion, Massachusetts. Its aim was to foster better relations between all nations through the medium of schoolboy exchange.

However, the authorities at the National Political Education Institutes (aka Napolas), the Third Reich’s most prominent elite schools, had other plans. Lillard and the ISF were informed on 12 February 1935 that they would be exchanging ten American boys for ten Napola pupils. However, the American organizers were wholly unaware that the German pupils and staff were charged with an explicitly propagandistic mission. Their aim: to counteract and neutralize the effect of anti-Nazi accounts in the American media; to form opinions, and influence future foreign views of the Third Reich.

To ensure the effectiveness of this pro-Nazi propaganda campaign at the highest level, one of the first German boys to be selected for the program was Reinhard Pfundtner, the son of a high-ranking civil servant in the Third Reich’s Interior Ministry. In his role as ‘state secretary,’ Hans Pfundtner was one of the key architects of the Nuremberg Laws, which demoted Jews, Sinti, and Roma to a pariah status within Nazi Germany, and which were instrumental in the genesis of the Holocaust. He was also a member of the Olympic Committee, and was keen to use the exchange as an opportunity to persuade Lillard, Reinhard’s American headmaster, to lobby in favour of U.S. participation at the upcoming 1936 Winter Olympic Games in Garmisch-Partenkirchen.

Surviving letters between Pfundtner and Lillard, now preserved in the German Federal Archives in Berlin, show that the principal of Tabor Academy was completely taken in by the Pfundtners’ pretense of friendship. In one letter from 23 November 1935, Lillard even assured Pfundtner that his ‘excellent letter replying to…questions about the Olympic Games’ had been ‘quoted by several of our good newspapers, and was included in the Associated Press service throughout the country… Undoubtedly, this message of yours will be very helpful in submerging some of the false propaganda.’

Even after the ‘Night of Broken Glass’ pogrom in November 1938, known in Germany as Kristallnacht, Lillard was still urging the principals at the eighteen American preparatory schools involved with the Napola-ISF exchange to continue the programme into the 1939-40 academic year. In one of these letters, he asserted that ‘if we continue to bring the boys together, something constructive may be accomplished; whereas, if we abandon all efforts in the direction of Germany, we are closing the opportunity for the future leaders to be enlightened, and we are retreating back toward the condition of ill-will which prevailed after the World War.’

In general, then, the Napola exchanges seem to have achieved their goal, at least in the short term. After 1935, many leading academies took part in the programme each year, including Phillips Academy Andover and Phillips Academy Exeter, St Andrew’s Delaware, Choate, the Loomis School, and Lawrenceville. Between 1936 and 1938, each year fifteen American pupils lived as pupils of the Nazi elite schools for ten months, while two groups of fifteen Napola-pupils spent five months each at the American schools.

The Napola-pupils were often able to convince their American hosts that events in Germany were not nearly as dire as press reports might lead them to believe—and were also given the opportunity to put their political point of view across. Reports in school newsletters suggest that the American pupils also enjoyed getting to know the ‘new Germany’ and could quite easily be swayed into displaying some sympathy for their hosts’ political perspective.

One American pupil who attended the Napola in Plön claimed that the year he had spent there was the ‘greatest experience of his life.’ Another was even discovered practising the Hitler salute in front of his mirror. Meanwhile, many staff and pupils at the US academies kept in touch with their German partner schools even after the outbreak of war in 1939. Walden Pell, principal of St Andrew’s School, Delaware, continued to correspond with the parents of one of his German exchange pupils for decades, assisting them in their search for their missing son, sending them food parcels and care packages, and donating a large sum of money to enable a pilgrimage to his war grave in Italy once his final whereabouts were known.

To a present-day reader, the attitudes towards Nazi Germany depicted here might seem highly naïve. At the time, however, many educated Americans shared similar sentiments—curious, trusting in German good faith, and willing to downplay or disregard prior reports of Nazi atrocities, at least until Nazi belligerence reached its fatal climax.

Feature image by Australian National Library via Unsplash.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers