Oxford University Press's Blog, page 28

April 26, 2024

Unlocking the Moon’s secrets: from Galileo to giant impact

Unlocking the Moon’s secrets: from Galileo to giant impact

It is a curious fact that some of the most obvious questions about our planet have been the hardest for scientists to explain. Surely the most conspicuous mystery in paleontology was “what killed the dinosaurs.” Scores of hypotheses were proposed, ranging from the sublime to the ridiculous and including such delusions as “senescent overspecialization, lack of standing room in Noah’s Ark, and paleoweltschmerz.” Not until 1980 did a hypothesis catch on—the Alvarez Theory of dinosaur extinction by meteorite impact—and it is still not fully accepted today, 182 years after Richard Owen discovered the terrible lizards.

In the nineteenth century, scientists were preoccupied with explaining the ice ages, when vast sheets of ice marched from the poles, obliterating everything in their path, only to retreat—and repeat. Not until the 1970s did scientists discover that cyclical changes in Earth’s orientation in space and distance from the Sun caused the great glaciers to wax and wane. The first maps of the Atlantic Ocean in the sixteenth century showed that the facing coastlines of Africa and South America fit together like two pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. Geologists rejected Alfred Wegener’s 1912 explanation that continental drift had ripped a giant protocontinent asunder. It took until the mid-1960s and the discovery of plate tectonics to explain the jigsaw fit. This led to the realization that the continents and ocean basins do not stay in one place, but move constantly, albeit at the minuscule rate at which our fingernails grow. Or consider one of the most conspicuous features of our planet, America’s Grand Canyon, plainly visible from space. In the nineteenth century, its cause seemed obvious: the land underneath the Colorado River had risen, causing the muddy stream to incise itself ever deeper in its channel in order to keep up with the uplift. But by mid-twentieth century, newly discovered facts about the age of the canyon led scientists to finally reject the old hypothesis.

Every field of science has puzzles that despite being obvious, are exceedingly difficult to solve. Witness the Moon, the most viewed object in the sky, whose largest features we can see with the naked eye. Where did it come from and why does it hang there in space, the same face always turned toward us? The very first person to view the Moon through a telescope, the great Italian father of science, Galileo, saw that it’s surface was not smooth and regular, as the Greeks had supposed, but is marked by pits that came to be called craters. Another great scientist, Robert Hooke, unaware of the existence of meteorites, conducted experiments that indicated that the forces that had created the craters had come from below, from volcanism, a view that persisted for centuries.

Isaac Newton was able to answer the question of why the Moon neither crashes into Earth nor flies off into space: the Moon’s velocity in space gives it a momentum that exactly balances the gravitational pull of the Earth. Another great of the Enlightenment, the German philosopher Immanuel Kant, pointed out that the Moon’s gravity would slow the Moon’s rotation until eventually it kept the same face turned to the Earth.

Sometimes the answer to a scientific question cannot even be conceived because it depends on some fact yet to be discovered or some research method yet to be invented. Hooke realized that an object descending from above could have created lunar craters, but as far as he knew, the sky contained no such objects. Another reason scientists are slow to adopt a new idea is that they have become wedded to a particular dogma or theory and are unwilling to change their minds. Meteorite impact on the Moon was proposed in the 1870s, but it took nearly a century and spacecraft voyages to the Moon before scientists were willing to entertain it. Both meteorite impact and continental drift were resisted in part because they violated uniformitarianism: the belief that geological processes are gradual rather than catastrophic. Most geologists were unwilling to give up this fundamental principle, learned at their professor’s knee.

I have always been fascinated by how scientists have handled these great questions, both because I would like to know the answers myself, but also because they reveal so much about how science really works, as opposed to the idealized scientific method that we learned about in high school. I hope that readers will be interested in my latest effort to make science accessible: Unlocking the Moon’s Secrets: From Galileo to Giant Impact. You will learn how our seemingly placid and unchanging heavenly companion was born in the most colossal act of violence in the history of the solar system.

Feature image by Helen Field, via iStock.

April 25, 2024

How to co-write a book 3,000 miles apart: In Dialogue with Dickens [long read]

How to co-write a book 3,000 miles apart: In Dialogue with Dickens [long read]

RB lives outside Boston in the United States, PD across the Mersey from Liverpool, England. We have never met in person. We had found each other’s previous writings and ways of thinking sympathetic, in particular concerning the relation of writers and their autobiographical selves in the act of writing fiction. RB began publishing on Dickens in 1979, her book Knowing Dickens appearing in 2007. David Copperfield was part of PD’s Memory and Writing (1983), and Dickens figured largely in his volume on The Victorians for the Oxford English Literary History series in 2002. But we first encountered each other by exchanging drafts of the volumes we separately wrote for Oxford University Press’s series My Reading during 2020: one Samuel Beckett, the other William James.

What we had valued in the right-hand marginal notes provided by track changes was a form of excited interruption, adding an extra dimension to the otherwise continuous unfolding of one person’s thought process in the main body of the text.

What made it a real meeting during lockdown was that in each case whoever acted as reader found time and again what the writer had privately felt was his or her best or newest or most exciting place in the manuscript; the reader pointing through track changes and marginal comments to moments of sudden potential that needed or called for ‘more’, for further development. There was a wavelength. We decided to take this affinity and try to recreate it within a fuller collaboration. Our editor at OUP had already suggested a book on Dickens. But we knew that if wanted to recapture in a different form what we had been able to do for each other in the My Reading projects, it would not be by writing separate chapters in such a book, jointly authored. What we had valued in the right-hand marginal notes provided by track changes was a form of excited interruption, adding an extra dimension to the otherwise continuous unfolding of one person’s thought process in the main body of the text. We were not simply looking for each other’s cosy approval, any more than we prized merely opinionated disagreement, but what was most radically powerful in the process was when the reader picked up the thought of the writer, stopped it, felt and received its impact, and then gave it back again with added personal weight and a renewed sense of its living value. Often the comments were relatively raw and muted, pointing to something vital, saying wow, thinking of a related or contrasting example elsewhere, or noting that it made a difference somehow that it was this phrase or this situation and not another. This seemed to us more literary, or at least more like what literary thinking came out of, than offering immediate conceptual explanation. It was also more like speaking, another voice, an informal accompaniment. We felt we could only try to reproduce this sense of a jointly generated spark through dialogue: that spark was what thinking felt like at its best—electric, sudden, visceral, shared across poles—and this was what Dickens himself was like.

We communicated across the distance between America and England via books, via Dickens, trying to use our different lives in the same common purpose: In dialogue with Dickens.

Looking to create something other than interpretation from a single position, we wanted to open out the conventional form of the scholarly monograph: to include the rough beginnings of thoughts coming into being, to follow more than one line of argument at a time, and to register the after-meaning of the work as well as its immediacy. We hoped to let in the spirit of the inarticulately unknown or the personally hidden, felt, and imagined in author and readers alike, and to show unabashedly what matters to us, in both small detail and large concern, and in the relation between them. We communicated across the distance between America and England via books, via Dickens, trying to use our different lives in the same common purpose: in dialogue with Dickens.

It was at first a hesitant process. After some email discussion and drafting, we submitted a sketchy proposal and rough sample to OUP in October 2021 which went out for readers’ reports, and we were offered a formal contract in April 2022. In the meantime we resolved to go ahead anyway. We had decided, with qualms, to start with Dombey and Son and began to read it separately, at around the same pace, stopping to send each other emails on initial thoughts, however simple, with reading still in progress. We tried not to be too worried about either impressing or annoying each another, or to be quite conscious that we might be testing each other and the possibility of our working relationship. It began to go well when we noticed the same details, were moved by the same painful places, or discovered together in a shared area of feeling something new or latent that we could not have got to separately or more formally.

Then one of us might ask, anxiously: are we agreeing too much? Does it look chummy or false, like (yuck!): What a wonderful point you have made there, PD/RB!

This graduated to writing up the emails into the beginnings of a script. Best of all, one of us might say something like:

You go on from this good point you’ve made here, and develop it however you like for a couple of pages. We won’t bother initially with who is writing the most or whether either of us is going on too long and forgetting the other. As long as we are just concentrating on Dickens, instead of ourselves, that’s all we need to share. Then I will just take your two or three pages and if I want to, interrupt them with something they have made me want to say, inserting that in the midst if needs be, like the marginal comment in our previous partnership. And then you can respond and readjust in light of what I’ve said. Then we can keep asking: what is the next thought, what passage in Dickens will help us here?

It helped then to begin to have weekly meetings by Zoom from April 2022. What did this sentence mean in your last draft? Why should this thought or this situation matter so much to you personally? Or: Where should we go next? How can we keep this as close as possible to thinking in real time, without being sloppy? And are we only talking to ourselves? Or again: how can we best share this with an audience, without explaining too much, too sedately, in the aftermath of actually doing the thinking between us? Then one of us might ask, anxiously: are we agreeing too much? Does it look chummy or false, like (yuck!): What a wonderful point you have made there, PD/RB!

But really what we were doing mainly was trying to help each other, or rather help the thought between each other: not argue or agree, so much as develop, extend, push each other harder to get somewhere—in the chapter, into Dickens. We set ourselves homework before our next meeting, exchanged parts of Dickens’s manuscripts in PDF format, divvied up tasks, discussed different forms and shapes and divisions for the best presentation of our thinking, made notes and exchanged records of our discussions, sent pages back and forth, alternately, day after day—and in short and in truth, began to feel cheered and stimulated by each other.

…our aim was to show what goes on behind the scenes of a finished, published work, as still part of its meaning.

Over the many decades of our separate commitments to thinking about Dickens, both of us have read widely in the rich store of Dickens scholarship. But we decided early on that we would not, for the most part, stop to put ourselves in direct agreement or contention with specific critical arguments. Previous work on Dickens had become an implicit part of our thinking, such that we have not always known exactly how and when we absorbed it. We didn’t want in writing and rewriting to lose that human sense of a first experience, a sudden realization coming from somewhere prior to professionalization. In relation to ourselves, to the Dickens manuscripts, and to the use Dickens made of his life in his fiction, our aim was to show what goes on behind the scenes of a finished, published work, as still part of its meaning.

When it came to revising, we therefore needed to resist the temptation to smooth it all down, to create neat chronologies and lines of argument when rhythmically it hadn’t been like that in the first place. Naturally we cut what we thought were the boring bits, the undue repetitions, the moments when we had lost the originating spark. One thing we hardly ever cut or changed were those moments when one of us might say, ‘It is almost as though… almost as if…’ on the threshold of language; or would interject ‘I love the way that…’ on the basis of owned relish.

So we have sought neither to tame and tidy our thinking nor to be too obtrusively personal or wildly obscure. But when we have veered one way or another, we have tried to keep in our attempted correction of the course en route. That is why we found ourselves writing sections or even chapters that were like inserted ‘time-out’, sites of explicit revision, visible rethinking, placed in between one stage of the novel and another, or after our account of a novel had seemingly ended. We then went through the whole manuscript with the same principles and caveats, needing to stay quick in order not to forget its spirit, and completing it, for better or worse, a year ahead of schedule.

That’s our story.

This blog post has been adapted from the Preface to In Dialogue with Dickens: The Mind of the Heart by the authors.

Featured image: Dickens giving the last reading of his Works. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark. Source: Wellcome Collection. https://wellcomecollection.org/works/t2fy7db2

April 24, 2024

Unscheduled gleanings and a few idioms

Unscheduled gleanings and a few idioms

I receive questions about the origin of words and idioms with some regularity. If the subjects are trivial, I respond privately, but this week a correspondent asked me about the etymology of the verb loiter, and I thought it might be a good idea to devote some space to it and to its closest synonyms.

Words for worthless activities tend to emerge in slang and seldom have “respectable” ancient roots. Some of the synonyms of loiter belong to that “plebian” group. Such, for instance, is the verb to gad about, which surfaced in English in the fifteenth century. According to some authorities, it looks like a borrowing of Scandinavian gadda “to goad,” while others connect it with the obsolete noun gadling “companion,” later “wanderer.” Even though the second derivation looks more promising, the specific sense “to wander idly” suggests that perhaps we are dealing with an item of scamps’ self-characterization. The origin of even less mysterious monosyllabic words (dig, put, and kick among them) is no less problematic: they are easy to coin, easy to borrow, and hard to trace.

Dawdle is another synonym of loiter. Unlike gad, it was recorded only in the 1660s. It has such synonyms (or variants?) as daddle, diddle and doddle—thus, a frequentative verb with the suffix –le, as in babble, giggle, fiddle–faddle, and their likes. One of course also remembers doodle. Some such verbs have a curious history. Ramble is one of them. Rams are famous for their sexual power, and German rammeln does mean “to copulate.” In Dutch, the same verb was used about cats, rabbits, and other animals. English ramble looks like a variant of rammeln, but its meaning is quite innocent: “to wander about”—thus, another synonym of loiter. Is such a development (from copulate to wander) probable?

Loiter, a fourteenth-century verb, sounds quite unlike the monosyllables mentioned above. It appeared in Middle English in the form lotere and then in a 1440 English-Latin dictionary as loytre. Still later, the spelling leutere ~ leutre turned up. It is not improbable that “loiterers” (vagabonds) from the Low Countries were the originators of the verb (another case of self-characterization?). However, Leo Spitzer (1887-1960) thought otherwise. I often refer to that outstanding and prolific philologist, but usually with a mild caveat. He wrote dozens of short etymological etudes. A Romance scholar (journalist, literary critic, and dialectologist, among other things), he fled to Turkey and then to the United States from Hitler’s Germany (Spitzer was a Jew), and as of 1936, Baltimore (John Hopkins University) became his home.

In his lifetime, Spitzer was more notorious than famous, but in the literature on him I could not find an explanation for where he, a native speaker of German and a Romance philologist, learned such faultless English. His notes on English etymology are numerous and always inspiring. However, they display a noticeable bias: for every hard word Spitzer invariably found a French etymon. This bias is typical. I have more than once observed that linguists’ expertise tends not only to guide but to determine their conclusions. (At one time, I researched the life and work of the outstanding Icelandic philologist Stefán Einarsson. He always found the root of everything in Icelandic.)

Anjou, France.

Anjou, France.Image by Ty’s Commons via Wikimedia Commons, CC4.0

Not unexpectedly, Spitzer thought that the etymon of loiter was not a Middle Dutch but an Old French word. He cited the verb loitroner, current in Anjou “to walk slowly, etc.” and identified it with French lutiner “to behave impishly,” from lutin “imp who visits people at night.” The word goes back to the name of the god Neptunus, who, along with the other pagan divinities, was reduced in the Middle Ages to a demon or devil, or imp. Spitzer went on to account for the difference between the initial n in Neptunus and l- in the verband added many details to his reconstruction, all of which I’ll skip. One thing is clear: the French verb lutiner is not of Dutch origin. Though the semantic match between lutiner and loiter is perfect and the problem of the diphthong in the root finds a solution, Spitzer did not trace the path of the French verb to England. The question remains open, but in dealing with a word of dubious origin, the more information the researcher has, the better, so that a dissenting view cannot harm anyone. The French hypothesis does not seem to have been noticed. Long before Spitzer, Ernest Weekley, another first-rate French etymologist, supported the Dutch derivation, and so did Skeat before him. If loiter is indeed a borrowing from Dutch, the English adjective little may be related to it.

A postscript on toadI have once again consulted the most authoritative sources on the etymology of the Greek word for “toad.” Unlike the English noun typewriter, the Greek word is, most certainly, not a compound, and its origin is unclear. The other comment on the same post was from a reader who stated that the Old Chinese name of the toad looks remarkably like the English one. I won’t venture any hypotheses. Words, seemingly related in Indo-European and Chinese, are known. Whether toad is one of them is not for me to decide. The problem is that toad is limited to Germanic. If, however, toad is sound-imitative, as I suggested, its Chinese counterpart may have the same origin.

A few phrasesMore than a month ago, I began publicizing some curious idioms from my database that were not included in my recent book Take My Word for It. Today, I will cite a few more in the hope that our readers may have heard them or can say something about their use and origin.

A crow’s age. Crows do not live too long: just eight or twelve years. Why then did even Horace say to Lyce that he may live as long a crow’s age (IV Od. xiii: 24-25). And in 1887, a man from Nottinghamshire (England, the East Midlands) said: “Why, Bill, it’s a crow’s age sin’ I seen ya.” The wording surprised the correspondent of Notes and Queries, who had never heard the idiom. The American phrase I have not seen you in a coon’s age is known very well. Coon is of course “racoon” (no offensive connotations). But why were the crow and the racoon, two rather short-lived creatures, chosen as the best examples of longevity? No alliteration, no rhyme—nothing to endear those similes to native speakers of English.

Two dubious symbols of longevity.

Two dubious symbols of longevity.Image 1 by Rhododendrites via, Wikimedia Commons, CC4.0 and Image 2 by Cary Bass-Deschênes via Wikimedia Commons, CC4.0.

Paws off, Pompey. Many phrases exist only as part of adults addressing children. Has anyone heard paws off, Pompey, said to children when they put arms on the table? (asked in England in 1907). Who is Pompey? A dog? The phrase is slightly reminiscent of to make a long arm “to help oneself to something far from the place where one is sitting.” It was once known to many people in England and on the East Coast in the United States. Perhaps it still is.

Paws off, Pompey.

Paws off, Pompey.Image by Yaroslav Shuraev via Pexels.

He fell heavy “he died rich.” I wish all our readers many years of excellent health and prosperity. Live heavy, as it were!

Feature image by Kgbo, via Wikimedia Commons. CC4.0.

“Unparalleled research quality”: An interview with Tanya Laplante, Head of Product Platforms

“Unparalleled research quality”: An interview with Tanya Laplante, Head of Product Platforms

As part of our Publishing 101 blog series, we are interviewing “hidden” figures at Oxford University Press: colleagues who our authors would not typically work with but who make a crucial contribution to the success of their books.

Tanya explains how, as research behaviours have changed, we use digital platforms to ensure that our authors’ books reach readers worldwide.

What is your role at OUP?I am Head of Product Platforms in the Academic Division of Oxford University Press. I oversee the strategic development for the platforms, such as Oxford Academic, that host our book and journal products and services.

What is the difference between the product and editorial departments at OUP?While editorial focuses on individual works like books and journals, product is responsible for the overall success and health of OUP’s digital portfolio. Many departments contribute to our digital products and oversee various aspects of product creation and maintenance that are central to success: editorial, sales, marketing, data strategy, content operations, royalties, etc. Product’s role is to ensure that all of those aspects are working together in as seamless a way as possible to deliver high-quality, author-driven products to the people that read our content, namely researchers.

How did Oxford Academic become our home for academic books?Research behaviours have changed over the past two decades, as we have steadily seen sales shift away from print towards online. Oxford Academic allows us to better connect the online version of our books into a wider aggregated library of content that is easily found on search engines like Google, which can dramatically enhance the reach and impact of our authors’ work. Digital dissemination allows us to put scholarship into the hands of researchers and learners worldwide who might never have access to a library print copy.

Oxford Academic came out of a desire within the Press to create a single gateway into Academic’s content to streamline the research journeys of those searching for content in our books and journals. It launched with journals in 2017, with research books following in 2022. Digital-first publishing is a priority for OUP as it increases the discoverability and accessibility of our research, thereby magnifying its reach and impact for our authors.

What opportunities does Oxford Academic offer our authors?Oxford Academic offers authors a modern, mobile-friendly, accessible, search engine optimized platform upon which to publish research. In practice, this means that it’s easier for researchers to find our authors’ work online. With journals and books on the same platform, reader journeys across the two formats are not only possible but can be informed by AI-driven recommendation widgets, so readers are recommended other relevant research.

Some of the key benefits for readers include being able to:

Quickly find books, journals, and images by building powerful searches, or using our robust links to related content Access content from their preferred device, and experience a modern platform with updated features and functionality Understand research quickly with our graphical or video abstracts, non-textual outputs such as images, multimedia, data, and code, and text shown with tables or images side-by-sideOur Insight Working Group is constantly reviewing reader behaviors to recommend development that will drive the use of our books and journals content and, consequently, the impact of authors’ research.

What do you enjoy most about your job?I enjoy working across departments with various stakeholders to find innovative platform solutions for customers, readers, and authors. It can be a challenge to narrow down the areas of the platform that we should invest in. But I, and the stakeholders I work with, have developed a great deal of expertise that informs where investment is best placed. We want to invest in areas that will have the greatest impact for the greatest number of people that use platforms such as Oxford Academic, including authors, customers, and society partners.

How do you see the digital publishing landscape evolving over the next few years?New publishing models (Open Access) and technological changes (AI) are both impacting scholarly publishing. With the expansion of Open Access and a changing funder landscape, OUP needs to demonstrate the value of what we, as a non-profit publisher, bring to the research ecosystem. We need to better educate funders, authors, and customers about the critical role we play in the publishing process: overseeing peer review, managing distribution, application of metadata, maximizing discoverability on digital platforms, and more.

In terms of AI and other technological changes, we need to optimize the benefits while minimizing the risks. We are entering a period of great change in digital publication, from review to submission to publication and discoverability. The quality of the research we publish on behalf of authors is unparalleled. We need to harness that quality and use AI as a way to enrich the user experience and increase discoverability of the content, while ensuring we are still driving users to a trusted version of record on OUP’s platforms.

In both of these spaces, we will also need to consider unique services and capabilities we can provide for key stakeholders in this space, including authors, customers, and society partners. What can OUP bring to the table to make their role in the publication process a more seamless one?

Feature image by Marius Masalar, via Unsplash.

April 23, 2024

Is it democratic to disqualify a popular candidate from the ballot?

Is it democratic to disqualify a popular candidate from the ballot?

That a popular candidate could be disqualified from running and removed from the ballot might, at first glance, seem at odds with the very idea of democracy. For that reason, despite his evident role in instigating an insurrection, many Republican senators demurred and chose not to impeach former President Donald J. Trump on 13 January 2021. There was no need, they thought. The American voters had already passed judgment. Trump would now fade away.

Three years later, with Trump still fully in control of the Republican Party and poised to regain the Presidency, the US Supreme Court decided per curiam that Courts cannot declare a candidate ineligible for public office under the “insurrection clause” of the Fourteenth Amendment. Moreover, the Supreme Court’s scheduled hearing of Trump’s executive immunity claim seems intended to guarantee that the federal January 6 case will occur too late to influence or interfere with the 2024 US Presidential Election.

In these and other cases, we can see that, despite the existence of constitutional mechanisms to disqualify antidemocrats from obtaining power, elected representatives, judges, and other officials are reluctant to use them.

At first glance, there seems to be something principled about their reluctance: what is democracy if not an equal chance to see one’s preferred candidate elected into public office; and what are political rights if not the right to choose one’s values freely, even if that choice may seem “wrong” to others? As long as someone adheres to the legal democratic procedures in effect for pursuing their goals, are their views not as valid as anyone else’s?

Democracy seems to mean that every member should have their interests and values considered equally, through value-neutral majoritarian procedures. Everything should in principle be “on the agenda” when it comes to these procedures, to ensure that the electorate holds final authority over decision-making.

A measure like political disqualification seems to undermine the essence of democratic equal chance—even when used to stop an unambiguous enemy of democracy. So many today, across the political spectrum, express reservations about using such measures, arguing that the decision can only be left to voters to decide.

That view is mistaken, however. Elected and appointed leaders, not to mention democratic citizens, can be more confident in their defence of democracy. Constitutional mechanisms that limit value-neutral procedures, including disqualification, can be consistent with our most fundamental ideals of democracy.

The near collapse of democracy during the interwar period provides some insight into why that may be. It highlighted two related problems with conceiving of democracy merely as a value-neutral procedure. First, although value-neutral procedures are indeed important to democracy, they are insufficient. Liberal constitutionalism—human rights, the separation of powers, and the rule of law—is as essential. Without it, majority or even supermajority rule can become tyrannical and as oppressive as a dictatorship. So-called “illiberal democracy” is a contradiction in terms. A state must also guarantee basic rights, separate and balance its powers, and adhere to the rule of law to be considered a legitimate democracy.

Second, the interwar period exposed the limits of traditional methods of constitutional entrenchment, such as supermajoritarian thresholds. Those methods assume most citizens are fundamentally committed to democracy. That assumption proved wrong. Many citizens are at best weakly committed to democratic principles. Some are illiberal and antidemocratic. Others prioritize partisan interests over democratic principles. Antidemocrats can exploit a complacent or self-interested majority and turn democracy’s value-neutral procedures against its constitutional essentials, leading to democratic suicide.

Post-war constitutions, such as the German Basic Law, were designed with that historical lesson in mind. Among other things, they adopted what is known as “militant democracy” to defend themselves. A militant democracy is a democracy that adopts stronger forms of constitutional entrenchment, in particular explicit unamendability of basic rights, procedures to disqualify parties and candidates, and a more robust role for constitutional courts to check legislative and executive abuses of power, all to prevent democracy’s legal revolution. Militant measures limit political rights to protect democratic constitutional essentials against legal yet illegitimate changes.

Systematically demonstrating an intent to use one’s political rights to overturn democratic constitutional essentials may justify disqualification: a party becomes a candidate for disqualification if its internal structure is antidemocratic or if it endorses abrogating or derogating human rights; an individual becomes a candidate for disqualification if he knowingly assists an insurrection and in so doing violates his oath of public office.

Democrats can be confident in pursuing disqualification in these circumstances. Although some may believe disqualification pre-empts a legitimate democratic choice, the truth is that disqualification may secure the possibility for democratic choosing to happen in the first place.

Of course, it would be better to simply defeat antidemocrats at the ballot box. Yet history shows this does not always work. Democratic backsliding in countries like Hungary and India underscores the inadequacy of a passive defence of democracy. According to Freedom House, 2024 marked the eighteenth consecutive year that democracy declined worldwide. If democrats will not act to defend democracy, then who will?

One lesson from the COVID-19 pandemic is that states adopting multiple levels of defence fared best, notably New Zealand and South Korea. The reason is clear: every defensive measure has inherent weaknesses and blind spots. Relying on a single measure dramatically increases the risk of a threat breaking through, no matter how robust that measure is. Conversely, the layering and networking of different defence mechanisms generates a cumulative effect, significantly reducing the risk of a public health disaster.

Just as a single measure is inadequate in public health, democracy’s self-defence also requires a layered approach. Key strategies include promoting civic education in democratic values and tackling inequality through economic redistribution and strengthened social safety nets. However, it is militant democracy alone that addresses the problem of antidemocrats using legal revolutionary methods to subvert democracy. This recognition is reflected in the design of many post-war constitutions, which were written with the threat of legalistic antidemocrats in mind.

Militant measures work best when executed in a timely and decisive manner, as soon as a party or candidate reveals its true colours. It is far easier to disqualify a marginal antidemocratic party—as West Germany did in 1952 and 1956—than a popular one.

However, militant measures should be used in any case, whether a party is popular or not. It is far better to take action against antidemocrats, even if doing so is countermajoritarian, than it is to passively stand by, as if democratic suicide were democratically kosher.

In the end, what matters is the recognition that democracy extends beyond value-neutral majoritarian procedures. Human rights, the separation of powers, and the rule of law are the bedrock of any functioning democratic society. Today, the phenomena of democratic backsliding and “illiberal democracy” highlight the urgency of learning from democracy’s history. Militant democracy, including its disqualification mechanisms, is vital for countering the legal revolution of our democratic constitutional essentials and preventing democracy’s self-cannibalization. While their deployment must be judicious, measures of militant democracy are both legitimate and indispensable for guaranteeing democracy’s survival.

Featured image by Cyrus Crossan via Unsplash.

April 22, 2024

A Sand County Almanac at 75: the evolution of the land ethic

A Sand County Almanac at 75: the evolution of the land ethic

A lot changes in 75 years. In 1949, when Oxford University Press published Aldo Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac with “The Land Ethic” included, there were about 2.5 billion people alive on Earth. The atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration was just over 310 parts per million. The average global temperature was 0.6 degrees Celsius below the average for the twentieth century. Less than 30% of the world population lived in cities; agriculture was industrializing, but not yet industrial. Climate change and environmental injustice existed, but they were not formalized concepts, let alone fields to be studied. Much of Leopold’s writing was concerned with developing an appreciation for the aesthetics and services of intact ecosystems; protecting wilderness for recreation, beauty, and ecological stability; and advancing the emerging science of land health and the potential of ecological restoration.

If Leopold were to rewrite his collection essays for a present-day audience, he would face 8 billion people, 411 ppm of atmospheric CO2, 1.2 degrees Celsius of temperature rise, and an increasingly urbanized population. Climate change is perhaps the most widespread threat to human well-being—and life in general—and it both reveals and exacerbates environmental injustice around the world. We are reframing the concept of wilderness, and even conservation as a whole, as Indigenous and other non-Euro-centric perspectives are finally given the regard they deserve. And, while ecological restoration is now common and celebrated, we are confronted with new questions about what is right and wrong for us to manipulate in the landscape.

With all of this rapid change and no sign of slowing down, can Leopold’s land ethic evolve to stay relevant in this tumultuous era?

Thankfully, the land ethic was actually meant to evolve. Leopold acknowledged that he could not write or prescribe it—it would “evolve in the minds of a thinking community.” Leopold hoped his readers, members of a Western society who weren’t always raised to see the land as community, would create a mindset of care and respect for the land to which we all belong. The land ethic is meant to be a foundation for social norms that consider the health of air, water, soils, and all other beings. Such consideration was needed in the 1940s to address rampant soil erosion and habitat loss; it is needed today, perhaps even more urgently, to address our warming planet and species extinctions.

Because the land ethic was not meant to live in a vacuum, it adapts, informing and inspiring us as we seek to make our conservation work more just. The essay alone may not contain explicit guidance for how to pair care for other humans with care for the land, but the two are inextricably tied, and contemporary conservation leaders are bridging the gaps. “The evolution of the land ethic is an intellectual as well as emotional process,” Leopold wrote. It is our job to continue advancing this ethic from “the individual to the community,” taking what works from Leopold and combining it with knowledge and wisdom from other cultures and teachers, be they past or present.

For many, A Sand County Almanac and the land ethic are their first glimpse into a worldview that cares for and respects the land and other people. This worldview must continue to evolve with, and through, a more diverse thinking community if we are to truly develop an ethic of care for all people in all places.

A lot changes in 75 years, the land ethic included. It will continue to evolve with the times as we listen and learn from new voices and reconcile with past injustices. But no matter how or when the land ethic reaches someone new, it will still carry its timeless message: to “see the land as a community to which we belong.”

Feature image by John Salzarulo on Unsplash.

April 19, 2024

How do you solve a problem like gender inequality?

How do you solve a problem like gender inequality?

For most women’s rights advocates, the answer is obvious: adopt a human rights framework. At the global level this means using the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), ratified by 189 countries, which requires all states parties to themselves respect gender equality, protect against gender discrimination by others, and fulfill those human rights needs (e.g., right to adequate housing) that stand in the way. Women’s Property Rights Under CEDAW addresses those parts of CEDAW that protect, inter alia, women’s equal rights to access land, financial credit, social benefits, inheritance, and all forms of family property. While CEDAW has been subject to many critiques, my co-authored book defends it against criticisms that it privileges the experiences of Western women, fails to address salient issues (such as violence as discrimination), or marginalizes women’s rights. The book also rejects concerns that the CEDAW Committee’s property jurisprudence advances a “neo-liberal” agenda in favor of commodification, privatization, business deregulation, and economic globalization. The Committee’s outputs demonstrate how the Convention has evolved to incorporate domestic violence and nuanced positions on the male/female “binary,” the public/private divide, and the nature and causes of discrimination, subordination, and marginalization. There is a reason that CEDAW is specifically cited as a justification for progressive new laws around the world as well as in hundreds of national judicial opinions that use the treaty or the Committee’s jurisprudence to interpret existing laws and even national constitutions.

Nonetheless, the limitations that CEDAW shares with other global human rights institutions—from UN bureaucratic and fiscal constraints to a weak “managerial” approach to securing state compliance increasingly manipulated by rights-disrespecting states—encourages those seeking gender justice to seek alternatives or complements. The UN’s Development Agenda—specifically Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 5 to “achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls”—is one of them. Whereas CEDAW relies on a legal binding treaty under which states are obligated to implement at the national level equal rights of women, the SDGs’ 17 pledges are a political, aspirational effort, originating in hortatory General Assembly resolutions. They reflect a results-oriented model for international development for all—and not merely developing states—that set specific policy priorities, help steer action and resources, and use bench-marking backed by data. States’ progress towards achieving gender equality under SDG 5 is measured by nine targets and 14 indicators. This includes, under target 5.1 (to “end all forms of discrimination against all women and girls everywhere”), progress towards achieving indicator 5.1.1 which calls for the adoption of “legal frameworks . . . to promote, enforce, and monitor equality and non-discrimination on the basis of sex.” SDG targets and indicators, subject to periodic review since the SDGs were originally adopted in 2015, are intended to inspire new development thinking. While the SDGs have been criticized for lacking references to human rights, that might be the point.

For governments now caught in bottom-up populist or top-down authoritarian backlashes against human rights, the SDGs offer an appeal not to abstract dignitarian values but to the need to tackle structural obstacles like poverty, hunger, and gender inequality because these hinder economic growth. The SDGs appeal not only to “rule of law” states long accustomed to rights discourse at the domestic and international levels, but to governments—nearly all of them—that want to attract international financial institutions and market actors. They may particularly appeal to governments leery of “Western-centric” human rights or inclined to resist legally binding instruments that impose “sovereignty costs.” To be sure, the SDGs are not value free. Those who praise the SDGs see them as embodying Amartya Sen’s “human capabilities” approach grounded in the need to equalize life’s chances, satisfy basic needs, and level the playing field while paying greatest interest to those with the greatest need. Some may see them as yet the latest attempt to blue-wash the UN’s (and international financial institutions’) “civilizing mission,” notwithstanding the pretense of “universal” goals. Feminist critics of SDG 5 may emphasize what SDG targets/indicators fail to measure—namely enjoyment of LGBTQ rights, cyber or economic violence, women’s roles in peace-making and conflict, or the root causes of discrimination and violence against women. Those focusing on property rights might point out that while one SDG 5 indicator seeks data on the proportion of women who have rights to agricultural land, there are no requirements to measure many other kinds of property addressed under CEDAW, such as access to financial services, inheritance, or natural resources. The downside to the nostrum that “what gets measured gets done” is that under the SDGs what is not measured may get ignored.

Notwithstanding the SDGs’ weaknesses as yet another flawed attempt to impose global governance by indicators, advocates for gender equality searching for complements to CEDAW might consider their many other strengths:

(1) The SDGs encourage the collection of gender disaggregated data essential for naming gendered equality gaps and for measuring progress to resolve them.

(2) Many of the indicators (like 5.1.1 above) directly relate to lawyers’ efforts for law reform.

(3) The SDGs’ specificity may be useful for determining whether states are in fact taking “all appropriate measures” to combat discrimination against women as required by CEDAW’s Article 2; they may provide signposts that concretize states’ “due diligence.”

(4) The SDGs supply some useful data not typically demanded under CEDAW (such as, under 5.c.1, the level of governments’ resource allocations devoted to advancing gender equality).

(5) They embrace an integrative approach (suggested by the 54 gender-specific indicators apart from those included in SDG 5) that link gender equality to all the other development goals such as the alleviation of poverty, hunger, and environmental degradation.

(6) They provide more specific rationales for educating governments and the public about why gender equality is necessary to, for example, better address the disproportionate gendered effects of climate change.

(7) By calling attention to the costs of gender inequality to individuals, groups of women, to societies, and to the world—and to the resources needed to redress them—the SDGs demonstrate that advancing gender equality in all its dimensions is not free and that states facing massive sums of debt need help to achieve it.

All of these suggest another formidable benefit: the interconnectivity of the SDGs may enable gender equality activists to bridge silo-ed domains within governments and among international organizations and NGOs. They may help convince those who foolishly think that women’s equality is not their problem.

Featured image by Pawel Czerwinski via Unsplash.

April 18, 2024

The US South: A deadly front during World War II

The US South: A deadly front during World War II

The US Army recently gave a full military funeral to Albert King, a Black private stationed at Georgia’s Fort Benning who was killed by a white military policeman in 1941. With this act, the Army completed its acknowledgement of a racial murder it tried to cover up 83 years ago. What the Army or the nation has never fully recognized, however, is that during World War II, in and around Army facilities in the US South (where 80% of Black soldiers trained), an internal war zone raged, one with its own share of casualties, primarily African American GIs.

Ironically, the Army’s effort to enforce the laudable goal of nondiscrimination during wartime helped to stoke racial conflict and violence on this home front battlefield. During World War II, the Army built a biracial army, but one where all units remained strictly segregated by race. At the same time, the military tried to enforce the mandate enshrined in the 1940 Selective Service and Training Act, which officially disavowed racial discrimination. Segregation and nondiscrimination, however, were incompatible goals, especially in the South, where racial segregation was inherently discriminatory.

The Army’s effort to promote nondiscrimination within its own sphere did challenge existing southern racial practices and drew strident criticism from southern white leaders. In 1940, the Army desegregated its Officer Training School at Fort Benning; Black and white trainees lived and learned together before being assigned to their segregated units. Many army camps did not segregate sick or wounded soldiers by race in what was often a single base hospital. In 1942, the Army ordered a ban on the use of offensive language when referring to Black soldiers, a directive unevenly implemented, often dependent on the attitudes of individual commanders. In the summer of 1944, in large part in response to the racial upheaval ongoing in and around military facilities in the South and elsewhere, the Army made its boldest move to embrace nondiscrimination. It declared all recreation facilities and transportation under its control desegregated, although this order was also not always fully implemented by the officers charged with carrying out the directive. The Army took all these steps and others largely for reasons of efficiency and military necessity. For Black soldiers, these actions gave them some sense that they were part of a unified effort to defeat America’s enemies abroad and emboldened them to assert their rights as American citizens at home.

During the war, that home was the local communities that surrounded Army camps. While the Army could try to ensure nondiscrimination on base, off base the Army had no authority to enforce the principle of nondiscrimination. But the Army could not keep its Black soldiers locked on base; every soldier needed time away from their training and their military officers. And outside the camp perimeter, the harsh realities of southern racial segregation remained untouched by the upheaval of war.

As a result, many of the Black casualties of World War II’s “southern battlefield” occurred in the communities located near Army training grounds. In addition to Albert King, African American soldiers killed in the frequent wartime skirmishes in these locales include Henry Williams, a private from Birmingham, Alabama, stationed at Brookley Army Air Field and shot by a white bus driver in Mobile; Raymond Carr, a MP from Louisiana’s Camp Beauregard (and a Louisiana native), shot in the back by a Louisiana state trooper after the lawman told Carr to abandon his post in Alexandria, Louisiana; and William Walker, a private from Chicago, killed by local lawmen while fighting with a white MP just outside the fence of Camp Van Dorn, near the village of Centreville in southwest Mississippi. There were other Black casualties—including some deaths for which we will probably never know all the details, a common occurrence during wartime—as well as hundreds wounded in various beatings and assaults that occurred in the US South’s “war zone.”

Both Albert King and the MP who murdered him in 1941, Robert Lummus, were Georgia natives. Lummus had been at Fort Benning since the spring of 1940, when it was still a white outpost. After the draft began in the fall of 1940, the facility was soon transformed, as thousands of Black soldiers from all over the country arrived at what became one of the country’s largest training facilities. As the US Army began its experiment in promoting nondiscrimination, white soldiers like Lummus remained unmoved. He and others must have believed that Black soldiers at the facility would continue to abide by the South’s existing racial hierarchy. If not, the traditional use of violence to keep Black men in their “place” was a tried-and-true option, even if it meant opening another front at home in the global war of the 1940s.

During World War II, the US Army, through its nondiscrimination efforts, gave African American soldiers a glimpse of America’s racial future. And indeed, the US military would later be the first national institution to abandon racial segregation. The Army’s actions, however, had limits, both within the areas it controlled and certainly beyond. It simply could not change the hearts and minds of most whites, soldier or civilian, overnight.

Feature image: Black soldiers pinning their brass bars on each others shoulders, Ft. Benning, GA 1942. Courtesy National Archives (531137).

The Alexander Mosaic: Greek history and Roman memories

The Alexander Mosaic: Greek history and Roman memories

Perhaps the finest representation of battle to survive from antiquity, the Alexander Mosaic conveys all the confusion and violence of ancient warfare. It also exemplifies how elite patrons across diverse artistic cultures commission artworks that draw inspiration from and celebrate past and present events important to the community. Specificity of visual imagery (e.g., identifiable protagonists, carefully rendered details, and inscriptions) combined with commemorative intent differentiates historical subjects from scenes conceived generically or drawn from daily life. In celebrating events meaningful to those holding power, historical subjects are propagandistic in that they foster a supremely favorable conception of those responsible for their creation. Yet no matter how carefully makers try to control the message, artworks can acquire an autonomy that permits audiences to construct “memories” of those events never intended.

Properly speaking, the Alexander Mosaic’s manufacture comprises Roman work, but most scholars believe it reflects a lost painting described by Pliny the Elder: “Philoxenos of Eretria painted a picture for King Cassander which must be considered second to none, which represented the battle of Alexander against Darius” (NH 35.110). This would date to ca. 330-310 BC, when memories of the battle were still fresh, and its propaganda value would be most effective. That painting may have been brought to Italy as plunder after the Roman conquest of Macedonia in 146 BC. The fact that the mosaic reproduces an earlier work for a later audience forces us to consider the discrepancies between historical narrative and artistic tradition.

All of the surviving accounts of Alexander’s conquests were written against the background of Roman imperialism, and ancient readers necessarily interpreted what they read in the light of the social and political structures that characterized their age. Alexander “the Great” was a Roman creation: the title first appears in a Roman comedy by Plautus in the early second century BC. Because historical representations are distinctive and clearly recognizable to contemporary viewers, since its discovery in the House of the Faun at Pompeii in 1831, scholars have had to reckon with how the mosaic’s imagery functioned in two very different contexts: first as a fourth-century Greek painting and then as a first-century Roman mosaic. A painting celebrating a Macedonian victory meant something quite distinct when originally displayed in a Hellenistic palace than when it was possibly displayed as war booty in a Roman temple; and the mosaic copy in a Roman private house would carry still different significance. For a Roman audience, the commemorative specificity of the battle scene was probably less important than celebrating the qualities of Alexander’s personality that spoke to them: his ferocity in battle, his charisma, and his military genius. Alexander was as much a part of the cultural memory of Rome as Homeric epic was for Greece, providing a paradigm for their own military triumphs.

Heinrich Fuhrmann first suggested that the Roman patron of the artwork had participated in the Macedonian Wars, and that this mosaic copy of a spoil of war functioned as both a sign of his admiration for the “greatest” general and perpetuated the memory of his own role in overthrowing the dynasty that Alexander founded. A Roman viewer might have imagined a broader reenactment of the paradigmatic conflict between East and West, a conflict he may have participated in or merely appreciated through the lens of Roman ideology. Given the Roman taste for the allusive, a history become anachronistic could have also been appropriated and meaningfully reused through a cognitive metaphor whereby in place of Alexander’s empire, Roman viewers could have understood their own (since Rome had conquered the territories formerly occupied by Macedonia). Roman sources repeatedly compare Roman campaigns on the eastern frontier with earlier Greek struggles. Given that Parthia, which had fought on the Persian side against Alexander, was now Rome’s enemy in the east and Alexander’s legacy was now Roman, a Roman viewer could have easily identified with the Greeks. Furthermore, the patron who commissioned the mosaic copy belonged to the new Roman ruling class, which appropriated older Greek artworks—the fruits of their conquest—to express social status. It was prominently featured in a luxury dwelling, of a type also of Greek origin, whose colonnaded courtyards and receptions rooms were sumptuously decorated with other paintings and sculptures meant to impress visitors. Its Roman owner may even have appreciated the Alexander Mosaic as a “work of art”: an image divorced from its original context by its new role in a Roman social performance.

When artworks reconstruct a past in order to explain the present, their makers determine which events are remembered and rearrange them to conform to the required social narrative. Their display provides visible manifestations of collective memories. More than merely passive reflections, monuments with historical subjects reinforce those memories and confer them prestige. Divergent motivations were again in evidence after the Alexander Mosaic’s discovery when various European leaders such as the Prussian King Fredrick Wilhelm IV ordered copies of the copy: was the motivation for such modern commissions the desire for prestige achieved through association with a masterpiece from antiquity or with the political symbolism of its historical subject?

Featured image: Alexander Mosaic (ca. 100 BCE), Naples, Museo archeologico nazionale. Berthold Werner via Wikimedia Commons.

April 17, 2024

Walter W. Skeat and the Oxford English Dictionary

Walter W. Skeat and the Oxford English Dictionary

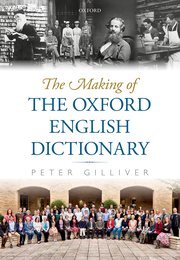

For many years, I have been trying to talk an old friend of mine into writing a popular book on Skeat. A book about such a colorful individual, I kept repeating, would sell like hotcakes. But he never wrote it. Neither will I (much to my regret), but there is no reason why I should not devote another short essay to Skeat. In 2016, Oxford University Press published Peter Gilliver’s book The Making of the Oxford English Dictionary, a work of incredible erudition. Skeat is mentioned in it many times, and I decided to glean those mentions, to highlight Skeat’s role in the production of the epoch-making work.

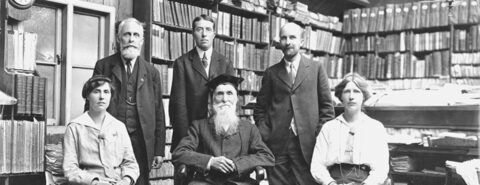

Twenty-six years separated the day on which the idea of the dictionary was made public and the appearance of the first fascicle. Countless people contributed to the production of the OED, but the public, if it knows anything about the history of this project, has heard only the name of James A. H. Murray, its first and greatest editor. This is perhaps as it should be, but in the wings we find quite a few actors waiting for broader recognition. One of them is Walter W. Skeat, a man of incredible erudition and inexhaustible energy. I have lauded him more than once (see, for example, the post for November 17, 2010, reprinted in my book Origin Uncertain….). However, today I’ll use only the material mentioned in or suggested by Peter Gilliver.

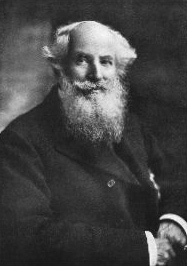

Walter W. Skeat

Walter W. SkeatImage by Elliot & Fry, Cassell’s Universal Portrait Gallery via Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

Skeat was not only the greatest English etymologist of his time (in a way, I think, of all times, despite the progress made by this branch of linguistics since 1912, the year he died). In 1873, he also founded the English Dialect Society and remained active in it as secretary and later director until 1896 (in 1897, after fulfilling its function, the society was dissolved). He edited the numerous book-length glossaries published by the society; attended its meetings wherever they were held, and without him Joseph Wright’s work The English Dialect Dictionary (1898-1905), still a source of inspiration to students of English, would probably not have been completed.

Among very many other things (!), he was a founding member of The Early English Text Society, and in 1865, he became a member of its committee. Neither post was “ceremonial,” for it presupposed a lot of work. Last but not least, Skeat was a generous man, a rare quality in scholars. For instance, he contributed a large sum of money to the Dialect Society at its inception, and much earlier, in 1885, he loaned Murray £1,660 for the purchase of a house in Oxford, the location of the future famous Scriptorium. Curiously, to this day, it is often the philanthropists who subsidize historical linguistics.

In the early eighteen-seventies, some influential people suggested that Skeat should become the main figure in the production of what became the OED. Fortunately, he concentrated on editing medieval texts and writing his etymological dictionary. He would not have become a second Murray, but by way of compensation, no one else would have done so much for the study of word origins and early English literature. Amazingly, Murray, a wonder of erudition, had little formal education and no university degree, while the Reverend Skeat’s background was in the classics. As individuals, Skeat and Murray represented different psychological types. Skeat was impatient and ready to bring out a book, not yet quite perfect, in the hope of a revised version. He would have been satisfied with a much smaller OED, while Murray made no concessions to haste (his invariable goal was absolute perfection, a wagon hitched to a star) and advised Skeat to wait for the completion of the OED before publishing his etymological dictionary. Fortunately, his suggestion fell on deaf ears, but Skeat’s readiness to agree that the text of the OED might be shortened infuriated Murray. (The episode was the result of a misunderstanding, and Skeat apologized.)

At that time, all thick dictionaries appeared in fascicles, which presupposed a good deal of competition among the lexicographers, the more so as a relatively small circle of publishers was involved. The people whom we know only from the names on the covers of their works were often not only colleagues and even friends but also rivals. At a certain moment, Skeat concluded that the Clarendon Press had declined to take on the OED and turned to the Press with an offer of his own etymological dictionary. As it happened, the two projects ran concurrently and did not get into each other’s way. Skeat’s work appeared in 1882, two years before the first fascicle of the OED came out. Murray once commented on Skeat’s dependence on the research at the OED, but Skeat responded rather testily that the OED had also had access to his findings. Yet Skeat remained Murray’s trusted friend and often maneuvered among various projects, to prevent other publishers from interfering with the OED. Though also hot-tempered, he was more diplomatic than Murray, and the relations between the two men remained friendly and even warm for years. To James Murray, Skeat’s death in 1912 was a heavy blow. He survived Skeat by three years. (Skeat: 1835-1912, Murray: 1837-1915.)

Throughout his life, Skeat supported the OED by his reviews (today it seems incredible that once not everybody praised Murray’s work) and kept chastising his countrymen for their ignorance and stupidity when it came to philology. He never stopped complaining that people used to offer silly hypotheses of word origins, instead of consulting the greatest authority there was. He also tried to encourage Murray, who often felt exhausted and dispirited. This is the letter he wrote to Murray, when he was working on cu-words: “I could find enough talk to cumber you. You could come by a curvilinear railway. Bring a cudgel to walk with. We will give you culinary dishes. Your holiday will culminate in sufficient rest; we can cultivate new ideas, & cull new flowers of speech. We have cutlets in the cupboards, & currants, & curry, & custards, & (naturally) cups. […] Write & say you’ll CUM!” Nor did Skeat stay away from the least interesting part of the work connected with the OED and often read the proofs of the pages before they went into print.

Frederick James Furnivall

Frederick James FurnivallImage via Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

Gilliver states that Skeat’s support for the Dictionary and its editors in so many ways places him alongside Furnivall and Henry Hucks Gibbs. Gibbs was “a wealthy merchant banker (and director of the bank of England) who would go on to become one of the Dictionary’s greatest supporters… He had been reading for the Dictionary at least since July 1860.” And the somewhat erratic Frederick James Furnivall (1825-1910) earned fame as a central figure in the philology of his day, even though today only specialists remember him.

A picture of Furnivall can be seen on p. 12. Gibbs appears sitting in a comfortable armchair on p. 43, and on p. 67, an entry for rebeck “a rude kind of fiddle” (among other senses), subedited by Skeat, is photographed. Quite a few more bagatelles of this type can be produced by an attentive reader of Peter Gilliver’s monumental book, but for the moment, I’ll stay with Skeat.

Header: James Murray photographed in the Scriptorium on 10 July 1915 with his assistants: (back row) Arthur Maling, Frederick Sweatman, F. A. Yockney, (seated) Elsie Murray, Rosfrith Murray. Reproduced by permission of the Secretary to the Delegates of Oxford University Press.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers