Oxford University Press's Blog, page 24

June 19, 2024

More gleanings and a few English sw-words

More gleanings and a few English sw-words

Before I come to the point, a short remark is due. Some of our readers may have noticed that two weeks ago, they did not receive Wednesday’s post. This happened because of a technical problem, but the post “Some Gleanings and the Shortest History of Bummers,” is available.

On June 12, my topic was “Pudding All over the World.” As a postscript, I mentioned an enigmatic phrase about Larry Ward’s pig lying in lavender. Many thanks for the comments and for the words of encouragement. One of our readers wrote: “Keep going.” I will! Jonathon Green, to whom, among other things, I owe a debt of gratitude for his generous words printed in the blurb of my recent book Origin Uncertain, sent me a bunch of citations with the word lavender, matching the context of my quote to a T. Lavender is, obviously, the right place for reposing, but Larry Ward did not show up in any text. Stephen Goranson, who can usually identify the best-hidden characters and decipher impenetrable acronyms, did not find Larry Ward either. May this gentleman, the owner of an indolent pig, enjoy his peace. I’ll only reiterate my favorite reference: like Rosa Dartle, I asked merely for information.

In the meantime, a reader sent me a query about the origin of the word swig “gulp of drink.” He suggested German saugen “to suck” as a cognate of this otherwise obscure word (obscure only from an etymological point of view). I responded in a private letter that, to my mind, the answer lies elsewhere. Yet Francis A. Wood, an extremely active etymologist of more than a hundred years ago, also connected swig and saugen (saugen is of course related to English suck).

This is what I can say on this matter. Let us look at a few other sw– verbs. In parentheses, the century of the word’s first occurrence in print will be given.

Swab (16) “to mop up, etc.”; several exact cognates in German and Dutch. The initial sense must have been “to sway.”Swag (18): several senses, but the basic one is again “to sway,” easily recognizable from the verb’s frequentative doublet swagger (a Norwegian cognate is known).Swank “to show off, etc.” (19): its German cognate schwanken means “to sway” (the origin is said to be unknown, but we find the same verdict in the entries on the previous verbs).Swop (14), which is remembered mainly or only as meaning “to exchange,” might be sound-imitative .Swash (16), belonging with clash, dash, crash, and their likes, is certainly sound-imitative.I would be surprised if sweep (13) did not belong with swap, swash, and other verbs of this type.For a long time, swive (12) was the main verb for “copulate.” Like our indispensable F-word, it meant “to move on, sweep, move back and forth” (see sway, above!). This sense is still partly recognizable in the related adjective swift.Sway emerged in text in the sixteenth century, and it looks like a doublet of swag.Though I know full well that reading such lists will bore anyone but a lexicographer, there is an important point to make, namely, that swig is a member of a large but loose family. Everybody realizes this, but dictionary entries, of necessity, present a series of disjointed words, rather than a mosaic. Therefore, bear with me. I’ll let the verbs swallow, sweep, swim, swindle, swing, swirl, swish, switch, swither “to hesitate,” swoon, swoop, and swoosh, a doublet of swish, stay dormant and come to the point. And the point is that each of the verbs mentioned above has a history, and their history has been traced very well (the main source is of course the OED), but none has an etymology worth mentioning (origin unclear; expressive; similar forms have been recorded elsewhere, and so forth). Even some old and “respectable” verbs with many cognates in Frisian, Dutch, German, and Scandinavian like swim, their reconstructed ancient roots and all, do not break the magic circle of “move quickly (or with a noise)” and occasionally being onomatopoeic.

Let us now look at swig. Its neighbors are swill and the little-known swizzle “to guzzle.” According to one hypothesis, swizzle is a blend, and it does look like a blend of swig and guzzle. Now, suck once had a long vowel in the root and is related to soak and as noted, to German saugen. Perhaps soak and suck are also expressive verbs. It is only obvious that initial sw– may have an expressive value, and I would prefer to treat swig as a “sound gesture.” Our readers may say that I refer to sound imitation and sound symbolism much too often, but this happens because I prefer to discuss unusual words, including slang. And at the dawn of creation, probably all words were “expressive.” Today, bed, pig (in or out of lavender), laugh, and so forth are mere “verbal signs” to us. Things were different “once upon a time.” At the end of this post, I’ll return to the question about how our views on the most common phenomena change over time.

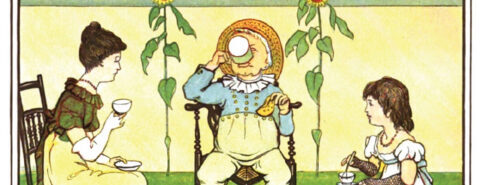

This is a swivel chair. No reference to hips.

This is a swivel chair. No reference to hips.Image via Picryl. Public domain.

With regard to sw-words, here, for amusement’s sake, are a few quotes from little-known sources. “… many schoolteachers were once called ‘Miss Swivel Hips’.” A swivel, as we remember, is a coupling device that accounts for the swivel chair. “… the verb swatch [rhyming with catch!] in swatch round, etc., meaning ‘bustle about’ or ‘get busy’ was used by a Kentucky friend of mine in 1929. …swatch is reported from Nebraska as used in the sense of ‘swat’ or ‘switch’.” “…swank in the sense of ‘agile’… is in common use in Scotland. A swank child is one who is tall, well-knit, and not burdened with superfluous weight.” Many such curious examples can also be found in the OED and in dialectal dictionaries.

As promised, I’ll end this swashbuckling adventure through a forest of words of dubious origin with a note on facts and opinions and will quote a ditty from my collection of proverbial words and idioms. At one time, everybody (at least in GB) seems to have known the rhyme: “February fill-dyke / With either black or white; / But if it is white, /the better to like.” The rhyme has existed for over five centuries. Do people still know and recite it? The meaning of the third line (…but if it is white) has attracted a good deal of discussion. February is certainly not the rainiest month of the year in Great Britain.

Image by Benjamin Williams Leader via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

Image by Benjamin Williams Leader via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.Do the following explanations make sense? “A considerable amount of rain may fall upon growing crops and on a thirsty land with but little effect in increasing the volume of water in the neighboring streams; but when February begins, there is but little vegetation, and, moreover, the ground has usually become so saturated that it can absorb no more, and so the rain—although so little—fills the dikes.” Conversely, “Old folks in Somerset still quote this proverb as though it was founded on fact. It is no use to remind them that February’s not really a wet month. They shake their heads and intimate that “the seasons have changed.” Both quotations appeared in 1905. It has also been noted that as a matter of “statistics,” the saying is not true.

Today, we know incomparably more about weather and climate than people knew not only in the remotest past but even a hundred years ago. Is there anything to say about the old proverbial poem?

Featured image by Frederick Warne & Co. via Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

Distributed voice: disability and multimodal aesthetics

Distributed voice: disability and multimodal aesthetics

“Let’s listen with our eyes and not just our ears.” – Christine Sun KimSome years ago I became interested in the impact of tape-recorders on postwar poetry. The advent of the small reel-to-reel tape recorder, developed by Germans during WWII, was instrumental in disseminating Hitler’s voice to the masses. As Alice Kaplan says, for Nazi propaganda it was the “reproduced voice rather than the voice itself that conveyed the archaic values demanded by so-called antimodernist fascist rhetoric.” When the portable tape-recorder began to appear at poetry readings in the 1950s and 1960s this reproduced voice allowed poets to hear their own voices for the first time and accommodate this knowledge to graphic innovations on a page that Charles Olson regarded as “a score for the voice.”

I called the voice thus produced a “tapevoice” as a way of describing the liminal condition of a voice that while accurate to the poet’s reading was also mediated through technology. The dissemination of reel-to-reel (and later cassette) tapes in library archives and digitized on websites like UBU Web and PennSound has given students and scholars a unique opportunity to compare the poem on the page against the poet’s idiosyncratic vocal inflections along with the ambient sound of the reading venue, interlinear commentary, and audience noise.

Over the years since writing about tapevoice I have lost most of my hearing and rely on various interfaces—captions, American Sign Language, lip-reading, conversation slips, and body language—that distribute the voice through multiple modalities. What I call “distributed voice” refers to the multiple forms through which the voice is produced and reproduced. But the idea of a voice dissevered from its source in the body and distributed through other media touches on larger communicational ethics in an era of digital information, social media, “fake news,” and broadband connections. Derrida’s important deconstruction of voice as originary source, tied to a metaphysics of presence, understands speech as an effect of linguistic difference embodied by writing. He does not discuss the different meanings voice may have for persons who, socially or sonically, lack a voice.

Artists and poets have seized on the materiality of vocality and its socio-political implications to create work that challenges the audio-centricity—“audism”—of hearing culture. This is particularly the case with deaf artists such as Christine Sun Kim who understands voice and sound as a kind of cultural capital that organizes a world around the ability to hear. When a gate change at the airport is broadcast verbally, when a political address is not captioned or sign-language interpreted, when the doctor diagnoses an illness without an interpreter present, deaf people understand the force of Kim’s economic metaphor. As I’ve written elsewhere voice, in a hearing world, is a social value as much as a communicational medium. In her work Kim “distributes” sound and voice through installations asking hearing audience to “hear” differently, making voice difficult to access or, by asking deaf friends to re-caption films they otherwise cannot hear.

Disability activists and theorists note that the absence of a sense is productive in gaining an understanding about what the world presumes as normal and obvious. What hearing people regard as a tragic loss or incapacity is understood by many deaf people as a “gain” in discovering new capabilities and potentialities. Many writers and artists, both disabled and not, have made the distribution of voice a key feature of innovative work. Consider the following examples of what we might call multimodal aesthetics: In Alvin Lucier’s I am sitting in a room the composer tapes his voice reading a text and then re-tapes the tape many times until the voice disintegrates into a low drone. The deaf poet Peter Cook and his hearing partner, Kenny Lerner, create collaborative poems where Peter signs in ASL while Kenny, standing behind him in a black hood, translates while simultaneously signing in front of Peter’s body—four hands signing. The poet Charles Bernstein incorporates his dyslexic spelling errors into his poem, “Defense of Poetry” while appropriating (and distressing) the language of another critic on his work. The composer Pauline Oliveros in her “deep listening” performances asks participants to “tune” on a single tone, thus distributing her voice among her audience members. In Richard Serra and Nancy Holt’s video, Boomerang, Serra records Holt speaking and then plays her words back through earphones after a one-second delay. In the video Holt struggles to continue speaking while listening and responding to her own voice, an experience that she characterizes as a “boomerang” effect. In these and other projects, aesthetic reliance on a single sensory organ—the filmic gaze, the sound of music, visual perspective in painting, haptic features of dance—is redistributed among the five senses.

Writing about the “acousmatic voice,”—a voice whose source is unseen—Mladen Dolar notes that “[r]adio, gramophone, tape-recorder, telephone: with the advent of the new media the acousmatic property of the voice became universal, and hence trivial.” I wouldn’t go so far as to say that voice has become trivial, but I do agree that the “property” of the voice, its materiality and malleability, is no longer unitary. My variation, “a distributed voice,” emphasizes the importance of mediation, speech, and sound as always already reproduced—appearing on a screen, a transducer waveform, an ASL sign, a caption, a Morse Code signal, Stephen Hawking’s voice generator, a tape recording—and gives new body to speech and new forms of speech to artists whose bodies and minds may speak differently.

OUP is not responsible for the content of external links.

Featured image by Shubham Dhage on Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

June 18, 2024

Age and experience: Early Modern women’s perspectives

Age and experience: Early Modern women’s perspectives

It’s newsworthy, apparently, when the cover of Vogue magazine features a woman over 70 years old. The New York Times recently devoted an article to the photograph of Miuccia Prada on the March 2024 cover, breathlessly noting that Prada was wearing little if any makeup, did not appear to be “posed,” and remarkably was not gazing at the camera, “looking elsewhere, thinking of something else.” Ordinarily, one would not think it surprising to see images of a powerful, wealthy, highly-educated—and attractive—woman in the public sphere. But her age….

The scrutiny of women’s age is hardly new. Seventeenth and eighteenth-century French salon culture was said to be “a woman’s paradise” of elegance, wit, and mild flirtation. However, actual women intellectuals and salonnières (salon hostesses) were frustrated by society’s emphasis on their physical appearance and the restraints on their behavior.

Old age and the activities and attitudes appropriate for the late stage of life are key topics in moralist reflections, from Cicero and Seneca to Montaigne. Nevertheless, as Anne-Thérèse de Lambert wrote in the early decades of the eighteenth century, male writers “work on behalf of men, and women are left to their own devices.” Lambert’s treatise on old age translates traditional reflections in terms that reflect women’s lives. In her more pointed “Discourse on the sentiments of a Lady who believed that love was appropriate for women who were no longer young,” her narrator juxtaposes the opprobrium attached to older women in love with the exceptional qualities of mind and heart of her friend Ismène, who holds the contrary opinion. Although the narrator ostensibly accepts the status quo (“I take the world as it is, not as it should be”), her essay ends with a scathing denunciation of a world in which men dictate the terms of women’s conduct: “everything is for them and against us.”

As I was working with these texts with retirement on my horizon, many of these women’s observations hit close to home. In one of Madeleine de Scudéry’s philosophical Conversations, the older Chrysante is universally admired for her wisdom, but her offer of mentorship to the younger Célinte is politely declined, since to be like Chrysante, Célinte would need to confront the reality of ageing.

Lambert sees the bucolic retreat from the world recommended by Cicero as a possibility for women, but she herself did no such thing: she maintained her influential salon until her death at age 86. At the end of the century, another powerful society hostess, Suzanne Necker, coolly observes, “When one is no longer young, one has nothing but religion, morals, friendship, and one’s mind: one should therefore live in retreat and often in solitude, because these benefits can only be cultivated far from other people…” Necker, however, maintained her salon until the French Revolution forced her and her husband, the former finance minister, to flee to Switzerland.

A common thread in many of these writings is relief that although old age poses its own physical and emotional hardships, it also provides a welcome relief from the expectations and constraints that weigh on young women. For Necker, “One is oneself at the end of life.” Constance de Salm mocks the “resignation of old age” as “the first stage of the declining mind,” but she saw at least one advantage: “being able to speak freely about any number of things that one could never say when one was young.” Journalist and essayist Pauline de Meulan Guizot writes a satirical piece from the perspective of a young woman who looks forward to growing old: “At sixty, one should shrug off others’ approval, so that they do not shrug at you. I can hardly wait to be sixty.” The older woman’s “gaiety can be less circumspect, her manners freer, her generosity more personal, her feelings more expressive.” If only, she concludes, one could have all that and be young and pretty too…

One of the most moving explorations of old age can be found in the late manuscripts of Geneviève Thiroux d’Arconville, written when she was in her 80s. In poor health and relatively reduced circumstances, mourning the deaths of friends and family members, she nevertheless found pleasure in writing, exploring ideas, and delighting in quirky language. Beginning an essay “On Commerce,” she digresses: “My old brain cannot seem to come up with anything to feed my pen, despite my unfortunate need, even if 82 years of existence should excuse me from the effort of splattering ink on paper. But my pen’s nature is to have a doglike appetite, so I am forced to throw it at least some bones to gnaw so that it will not die of starvation.”

Without sugar-coating the indignities of old age, these women delve into what it means to “be oneself” at last. As I discuss in Women Moralists in Early Modern France, they show similar originality in their treatments of other topics from the tradition: self-knowledge, friendship, happiness, the passions, marriage, and women’s nature. They reflect not only on their immediate social world, but also on the philosophical tradition that has excluded their voices. If their writings remind us that women’s present-day limitations and frustrations have a long history, their ability to confront their constraints provides a salutary counter-example.

Featured image by Rosalba Carriera via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

June 13, 2024

Summertime musicking

Many families imagine summer as a time of endless fun and warmth. But summer is full of parenting challenges, including disrupted schedules and kids having more free time while parents have less. Such parenting challenges make this a great moment to consider how to weave music into activities and routines of family life to make things a little easier and a little more fun—an approach I call “parenting musically.”

New Zealand-born musicologist Christopher Small (1927-2011) coined the term musicking, which he used to encompass every aspect of music-making, including composing, performing, listening, setting up the stage, taking tickets at a performance, and so on. Musicking can occur on stages, in strollers, and everywhere in between.

For families, the idea of musicking can be valuable because it helps us recognize that there are many fleeting moments of a day that are already musical, such as a child creating rhythms with a pencil on the metal ridges of a radiator. The broad umbrella of musicking also reminds us of the many ways we can incorporate music into family life; there is no need for special training or polished performances. We can slip in a sung “Hello, hello, hello” to our own tune each time we come home, creating a small but poignant ritual.

In my research with families and how they use music in daily life, I found it helpful to consider the purposes for which parents deployed music. I observed families using music in ways that were mostly practical, mostly relational, or a blend of the two. You might recognize that certain times of day call for practical musicking (such as a song that gets kids into their car seats and buckled without arguing!). Other summer moments are prime for relational musicking, like reconnecting as a family after children return from summer camp. The families in my research study reported that blended goals (practical and relational) helped sustain musical involvement over many years.

Practical musicking helps us get things done as a family with a little more ease, including brushing teeth, calming down, or building specific musical skills. For example, music playlists can help provide structure to wide-open summer days, with “get ready” playlists and “calm down” playlists. As a family you could put together a “get ready” playlist that lasts for the length of time you expect your children to accomplish specific morning tasks (eating, grooming, chores). Set the goal of finishing before the end of the playlist. Playlists can also bring a sense of stability if you are traveling or your schedule is disrupted—even though the location or time has changed, the music is the same for your kids. If your children have more free time than usual during the summer, consider pointing them to music composition apps such as Garage Band, Soundtrap, and BandLab to build skills and provide a creative outlet.

Relational musicking refers to music making that helps children deepen their relationship with self, family, friends, the world, or the divine. You could make a list of family members to connect with over the course of the summer, either in person or long distance, then brainstorm ways to connect musically with these family members. For instance, prepare three songs to play on the porch for grandparents, or collaborate with teenage cousins on a long-distance ringtone composition using Garage Band or a similar app. Model for your children the way you use music relationally, such as showing your excitement to attend a concert with college roommates or demonstrating how you create a new playlist for your partner with songs you think they will enjoy.

Summer is also a good time to explore new music—whether by new music listening, opportunities, and concerts, or by finding new ways to engage with music. Make a “new music” calendar and assign family members to find and share new artists each week during shared listening in the car or at home. If your family tends to use headphones to create their own sonic worlds, use the new summer schedule to designate a few times for shared listening. Make a summer bucket list of music festivals, outdoor concerts, or album releases you are excited about. Look around for free or low-cost opportunities to engage in music in new ways, like community dances or drum circles.

The suggestions for adding musicking to your summer do not need to include expensive or time-consuming activities. Small adjustments can add more meaning to existing family traditions. You might also notice that many of your musical interactions are practical and decide to intentionally “add more relational musicking to the mix.” Throughout, remember that music belongs to everyone and does not require special training or equipment. Create your own family hashtag or keep a family journal to document your shared musical adventures this summer, from practical to relational and everything in between.

Featured image by Aarón Blanco Tejedor via Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

June 12, 2024

Pudding all over the world

Quite recently, the Polish linguist Kamil Stachowski has published a paper “On the Spread and Evolution of pudding” (the source is the journal Studia Linguistica Universitatis Iagellonicae Cracoviensis 141, 2024, 117-137). He followed the history of pudding in England, the United States, Germany, France, and Italy. The present post owes its inspiration to Stachowksi’s paper (a few statements will be lifted from it without quotes), but some of the etymological musings are mine. On the face of it (read my lips: I have used this idiom on purpose), the origin of pudding is rather obvious. Consider pad ~ paddock “frog” (enough has been recently said in this blog about frogs’ propensity to puff themselves up), pod, pudge ~ podge “a short fat person,” poodle, and a few other similar p-d words, all of which convey the idea of swelling. Probably it is the sound of p that provided the inspiration. To produce p, we press and open the lips; hence the vague idea of puffing. Also, consider the verb pout and all the puddles and piddling people you have failed to avoid in your life. Such words are sound-symbolic, rather than sound-imitative (like crush, crash, grunt, growl, and so forth).

Image via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

Image via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain. Pudding probably belongs with all such p-t ~ p-d words. Because what is a pudding? Once, very long ago, the familiar word meant “sausage” (this statement will surprise many, but such is indeed the beginning of all puddings) and later, “boiled and steamed cake.” The cake was originally boiled in a bag “to a moderately hard consistence,” as the sources tell us. A pudding has the tendency to spread, to puff itself up (so to speak). Curiously, though the word pudding was attested in English texts around the year 1100, for the first two and a half centuries, it seems to have occurred only as a byname or a name. This, I think, points to the old word’s expressive register (slang). We often encounter nouns that originated in rude mockery but were later “ameliorated.” As regards names, the modern noun boy may be a continuation of Old English Boia.

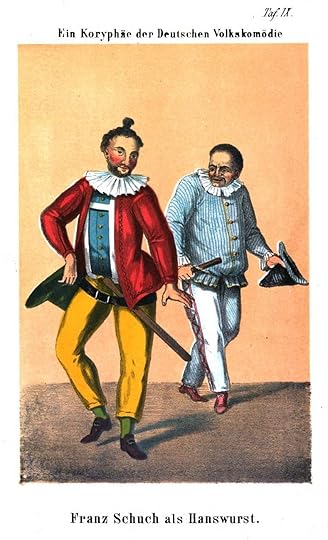

It is curious how the sense “sausage” stuck to pudding. In the post-medieval period, Jack Pudding was the name of a famous buffoon (attested as early as 1635). His continental counterpart was the German comic character Hanswurst, that is, “Hans sausage.” The word is northern German. I do not know the literature on the names of those clowns, but I wonder: aren’t we dealing with some sort of common North-European slang? And why pudding, that is, sausage?

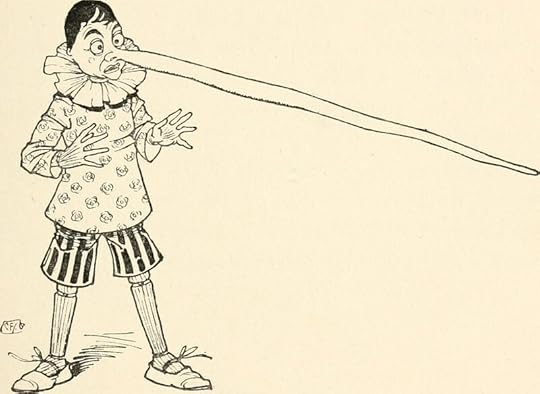

Clowns still appear with a long nose on the face. Pinocchio (that is, his ancestor Burattino: not a clown, but a great master of tricks and the embodiment of mischief) had such a nose too. Was “sausage” a vulgar substitute for “penis”? A helpful synonym dictionary informed me that today, among the amazingly numerous words for “penis,” one finds sausage, hotdog (!), and quite a few other nouns of this type. Stachowski mentions the fact that pudding “penis” was around as early as 1693. Apparently, people don’t change, and manners don’t improve.

Pinocchio, famous for his tricks and long nose.

Pinocchio, famous for his tricks and long nose.Image by Internet Archive Book Images via Flickr. Public domain.

But back to etymology. Anglo-Norman had the word bodeyn ~ bodin “(blood) sausage,” and following the OED, most dictionaries look upon this word as the source of the English noun. A few cases of Old French initial b becoming p in Old English borrowings are known. But the OED does mention the possibility of a native origin. If native, pudding may align itself with other p-d words, like those mentioned above. Also, the OED admits that both etymologies have a chance, because pudding might be an Anglo-Norman borrowing from Germanic. In any case, –ing in pudding seems to be the continuation of –yn of bodeyn.

If my idea of pudding as slang has any virtue, the North Germanic hypothesis does not sound too bold. Stachowski also admits such a possibility. The p ~ b problem more or less disappears if the word was sound-symbolic: in such nouns and verbs, the occurrence of p and b was not regulated by any rigid “sound law.” Who cares whether you say boo to a goose or pooh-pooh your friend’s warning! Stachowski also favors the Germanic etymology of pudding. On the whole, the origin of pudding seems to be rather clear, especially in comparison with the almost hopelessly obscure haggis.

Say boo to a goose.

Say boo to a goose.Image by Wellcome Collection via Rawpixel. Public domain.

As noted, the first attestation of pudding (in this survey, I depend on Stachowski’s summary of the data in the OED and other sources) points to “sausage.” When used in the plural, the sense “bowels” emerged. However, as early as the middle of the 16th century, pudding could already refer to a sweet preparation, or to what is today known as bread pudding. We can ascribe this development to “the fact that the distinction between… the main course and the dessert was not as rigorous during the Tudor period as it is today, and meat was regularly paired with fruits.” Additionally, we are told that bread pudding can also be seen as the transitional form with regard to consistency, and in the 17th century, puddings boiled in cloth were recorded for the first time. Regardless of the many niceties found in those old recipes, pudding shifted its meaning toward “cake.” “The leitmotif of that seemingly unexpected change is ‘a mixture of fine ingredients in a sauce’.”

Finally, the American version of pudding made its appearance. The new dish bears resemblance to thick custard or blancmange more than to a cake. Consequently, from cake to custard. (Those interested in cowardly custard will find some information in my post for May 17, 2023: “On Cowards and Cowardly Custard from a Strictly Linguistic Point of View.”) We are told that though this new kind of pudding has never completely replaced the old usage of the word, it has relegated it to second place, and not just in America. I’ll skip the history of many other figurative senses of pudding and the word’s travels through three European countries, with the by now familiar p- ~ -b variation.

Since sausage and puddings are historically connected, while sausage belongs with pork, I may be excused for returning to my database of unpublished idioms, to reproduce the following letter from Notes and Queries (November 11, 1882, pp. 388-389): “In Memoirs of the Rebellions in Ireland, including that of 1798, &c., third edition, 2 vols. 8vo, 1802, one gentleman is recorded to have remarked to another, whom he was engaged in translating to another sphere, ‘You lie there, my lad, in lavender, like Larry Ward’s pig. Who was Larry Ward; and why did his pig rest in lavender?’ No answer ensued. Idioms with references to such characters are numerous, and some of those probably emerged merely for the sake of alliteration. Here, my lad… lie like Larry Ward’s pig in lavender). But is this all there is to the question? The internet informs us that pigs seem less stressed if their barn if scented with lavender. I also found Lavender Pigs Fabric. Apparently, the association between pig and lavender in that old sentence was not quite fortuitous. This is a promising clue. But to repeat the question: who was Larry Ward? Comments and conjectures are welcome.

Featured image by HarshLight via Flickr. CC2.0.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

Greenhouse gases from an unseen world

Greenhouse gases from an unseen world

The list of ways we humans produce greenhouse gases is long and varied, starting with the combustion of coal, oil, and natural gas, which releases prodigious amounts of carbon dioxide. That most important greenhouse gas is also emitted by deforestation, the making of cement, the cultivation and harvesting of crops, and the raising of cattle, pigs, and chickens. Agriculture accounts for an even larger fraction (40 to 50 percent) of two other greenhouse gases, methane and nitrous oxide, released by anthropogenic sources. The list goes on.

Yet we aren’t the biggest emitters of greenhouse gases. Depending on the gas and the study, the biggest emitters are often the smallest organisms on the planet: bacteria, fungi, and a few other inhabitants of an unseen world.

Let’s start with carbon dioxide. The gas is measured in petagrams, or Pg, which is one million billion grams or a billion metric tons. Today, there is over 870 Pg of carbon in the atmosphere. The roughly 10 Pg released each year by fossil fuel use is small compared to what comes from nature, such as the roughly 50 Pg of carbon dioxide emitted by bacteria and fungi in soils each year. Bacteria in the ocean release over 145 Pg per year, although most of that carbon dioxide never gets to the atmosphere. A huge amount of carbon dioxide is discharged every year by natural processes, many of which are mediated by microbes.

More methane and nitrous oxide also come from microbes than from fossil fuels. Microbes in wetlands and other natural habitats produce about three times more methane than what is leaked from natural gas pipes and coal mines. For nitrous oxide, the difference is even greater—about a factor of 10.

Yet even though microbes release a lot of greenhouse gases, humans are the reason why greenhouse gases have been building up in the atmosphere since the early 1800s. We are the cause of the climate change now threatening the planet. Before the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century and agriculture’s Green Revolution in the 20th, levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere were roughly constant for eons. The carbon dioxide released by soil microbes was taken up by trees and other plants, aided by symbiotic fungi. The carbon dioxide from marine bacteria didn’t get to the atmosphere because it was used by microscopic phytoplankton during photosynthesis. Methane and nitrous oxide from microbes were degraded by other microbes before the gases could escape into air. The cycles of carbon and nitrogen were in balance.

Humans have disrupted that balance. Unlike the carbon dioxide released by soil microbes or marine bacteria, the carbon dioxide emitted by a gas-guzzling SUV or a coal power plant is not counteracted by any organism or process that soaks up the greenhouse gas. Methane has been increasing in the atmosphere not only because of natural gas use and coal operations (methane seeps out of coal mines and waste piles), but also because anthropogenic global warming has stimulated methane production by microbes in wetlands faster than microbes can degrade the gas. Global warming may lead to even higher emissions of methane and carbon dioxide as bacteria and fungi decompose organic matter previously frozen in Arctic soils and permafrost. The huge rise in nitrous oxide in the atmosphere started in the 20th century when fertilizer nitrogen became abundant and cheap after the invention of the Haber-Bosch process. The widespread application of fertilizer nitrogen is a big reason why the Green Revolution was so green. The problem is: as much as 75% of the nitrogen spread on a field isn’t used by crop plants; too much is transformed by microbes into a potent greenhouse gas, nitrous oxide. The Haber-Bosch process has doubled the supply of useable nitrogen to the biosphere, greatly upsetting the nitrogen cycle.

A big challenge facing climate-change scientists is figuring out what happens next: how will the biosphere respond to disruptions in the carbon and nitrogen cycles, global warming, and other manifestations of climate change? The answer largely depends on microbes. Understanding the most serious environmental problem facing us today depends on the smallest organisms—the microbes.

Featured image by querbeet via iStock.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

June 10, 2024

75 years of unidentified flying objects [interactive]

75 years of unidentified flying objects [interactive]

In the summer of 1947, a private pilot flying over the state of Washington saw what he described as several pie-pan-shaped aircraft traveling in formation at remarkably high speed. Within days, journalists began referring to the objects as “flying saucers.” Over the course of that summer, Americans reported seeing them in the skies overhead. News quickly spread and, within a few years, flying saucers were being spotted across the world. The question on everyone’s mind was: what were they? Some new super weapon in the Cold War? Strange weather patterns? Optical illusions? Or perhaps it was all a case of mass hysteria? Some, however, concluded they could only be one thing: spacecraft built and piloted by extraterrestrials. The age of the unidentified flying object—the UFO—had arrived.

Explore 75 years of this global preoccupation, with this interactive, multimedia map. The UFO phenomenon extends beyond national borders and beyond civilian sightings. You can also trace the military, government, and scientific communities’ evolving responses to lights in the sky and the possibility of extraterrestrial life.

Featured image by Albert Antony on Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

June 9, 2024

A ridge too far: getting lost in the Italian Apennines

A ridge too far: getting lost in the Italian Apennines

Most people these days speed across the Apennines between Florence and Bologna through road or rail tunnels without really noticing. But if, as I did, you travel more slowly along that ridge on foot, you’ll get some impression of how these modest peaks had once been seen as “the dreadfull … Appennines“.

A “dreadfull ridge of the Appennines”? The “Leap of Death”

A “dreadfull ridge of the Appennines”? The “Leap of Death”Photo credit: Nick Havely

Earlier travellers were faced with various dangers, such as accidents on the steep rocky tracks. A seventeenth-century guidebook urged its readers to beware of fatally losing their balance on the way over a high pass through being overcome by “the staggering whimsies”. A British tourist in the eighteenth century boasted about rescuing two ladies whose mule-litter had been overturned on a steep slope, where they would surely “have been dashed to pieces”.

Another threat was from one’s fellow men: extortion and poor accommodation were common complaints. Back in the Middle Ages local barons ruthlessly fleeced the merchants and pilgrims who came this way, and in the nineteenth century tales were told of innkeepers who robbed and murdered their customers, or even served them up as dishes on the menu.

Going astray with Dante and Captain BrookeDifferent dangers were faced by, for example, Dante, Victorian travellers, Allied escapees in World War II, and even myself; and we can now follow in the tracks of some of those wanderers. At one point during his climb up Mount Purgatory Dante is plunged into a thick fog which he compares to running into mist on the Apennines and “seeing no more than does a mole through its eyelids”. And at the very start of the Divine Comedy‘s allegorical journey, Dante’s traveller goes astray in a wooded and mountainous terrain that may recall the poet’s own crossings of the Apennines, and he finds himself confronting dangerous beasts.

Dante’s pilgrim in the dark wood and on the mountainside

Dante’s pilgrim in the dark wood and on the mountainsideImage by Baccio Baldini, Biblioteca Riccardiana via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

Later travellers would describe adverse weather and winds that could blow the unwary off their feet as they toiled over the high passes. One of those high passes—on the way over the Apennines from Florence—was the scene of an unintended detour by a British traveller early in the Victorian period.Captain Francis Brooke was a scholarly gentleman of leisure whose itineraries are described in his voluminous travel journals. In May 1844 Brooke was exploring the Casentino, a mountainous region to the north-east of Florence, and on the 12th of May, he set out to explore the Apennine ridge above the source of the Arno. He and his Italian guide climbed up to the river’s source, then upwards again to the summit of Monte Falterona on the ridge itself.

The start of Captain Brooke’s detour: Monte Falterona

The start of Captain Brooke’s detour: Monte FalteronaPhoto Credit: Nick Havely

He had told his guide that he wanted to visit a famous waterfall referred to in the Inferno. But Brooke had given his companion the wrong location, one that was some way north of the cascade mentioned by Dante. In addition they were now at a height of some 1600 metres, and crossing over to the north side of the ridge they “lost [their] way in the snow and fog, the former of which was in some parts four or five feet in depth”. They thus roamed around the flanks of the mountain, eventually reaching a “small hamlet”. From here, a woman who knew the way guided them over more peaks and along valleys to reach a village with two “pretty cascades” but not the ones mentioned in the Inferno. So, after a night spent in a squalid (but not actually life-threatening) inn, Brooke headed south again to the true Dantean waterfall, then crossed the Muraglione Pass over to San Godenzo, where his carriage was waiting to take him back to Florence.

Modern diversions: in Newby’s footstepsOne of the villages that Brooke came down to out of the fog on Falterona was where I set out in August 2001, on the last day of that year’s stretch of walking the ridge. My mistake that afternoon was missing the turning that would have led down to the Muraglione pass and continuing instead along a spur of the ridge.

After a large white mountain dog guarding its flock had warned me off, I headed down through the woods, following a precipitous dry streambed and emerging at a remote farm where an elderly nonna tending her chickens directed me down to the valley. I was now some eight kilometres of winding road on the wrong side of Muraglione, and the only way of reaching my hotel at San Godenzo that evening was to hitch a lift – which did eventually appear in the form of a couple of kindly honeymooners from Munich. It was worth waiting for the Bavarians.

I would go astray on several other occasions. Once I was trying in the dark to reach a high refuge and my torch bulb gave out as I looked across towards its distant lights. Again I had to struggle down a pathless slope, this time reaching a field that resounded with the harmonious howling of wolves. On another evening journey I stumbled off the ridge into a deep gully overgrown with huge bramble bushes: a similar predicament to Eric Newby’s when he tried to cross such a gully while reconnoitring an escape route to the coast during World War 2. As Newby later wrote in Love and War in the Apennines: “If I broke a leg here, no one would find my bones for years and years, perhaps never …”.

After getting lost yet again: the author following a hailstorm on Monte Nuda – “the Bare Mountain” – a peak I never meant to climb

After getting lost yet again: the author following a hailstorm on Monte Nuda – “the Bare Mountain” – a peak I never meant to climbPhoto Credit: Nick Havely

Getting lost in these mountains can prompt such fears. But it can also yield moments of getting to know them better: Captain Brooke’s intermittent views of the “beautiful valley of the Casentino”; Eric Newby finding refuge with an eccentric old craftsman and storyteller after escaping the dark bramble wood; my own encounter with the voices of the wolves echoing in a moonlit Apennine pasture. As Rebecca Solnit argues in her Field-guide to the subject: “Never to get lost is not to live”.

Featured image by Nick Havely.

June 8, 2024

Does Orwell still matter?

Does Orwell still matter? With Nineteen Eighty-Four celebrating its diamond jubilee, and the seventy-fifth anniversary of George Orwell’s untimely death quickly approaching, the question “Does Orwell still matter?” is timely. Familiar answers abound: he anticipated the surveillance technology that we struggle to restrain; the threats to freedom and democracy he identified remain at large; his ideal of windowpane-like political writing is still aspirational. But the familiar answers are also suspicious: our condition of continual surveillance was hardly imposed by the thought police given we freely embrace its technology; Orwell is hardly the only author to worry about the survival of Western values; the clear prose he admired has been exploited by nefarious actors. If Orwell still matters, he probably matters for different reasons. One reason is hinted at, not in his novels, but his reporting.

In “Why I Write,” Orwell affirmed that “Every line of serious work I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism, as I understand it.” His 1937 The Road to Wigan Pier is part commentary on England’s industrial North, part critique of his fellow socialists: it included attacks on “cranks”—progressives that Orwell thought had lost touch with common humanity—and Marxists who seemed to have no idea how to talk to actual human beings. “The fact is that Socialism,” he wrote, “in the form in which it is now presented, appeals chiefly to unsatisfactory or even inhuman types.” He knew just how unappealingly it could be presented. Having been harangued by a militant Communist propagandist, Orwell replied “Look here, I’m a bourgeois, and my family are bourgeois,” adding “If you talk about them like that again I’ll punch your head.”

Orwell’s pugilistic response expresses understandable anger to having one’s family threatened, but it also reveals an important insight. In The Road to Wigan Pier, he repeatedly suggested that abandoning a core self-conception amounts to death: he explained that “to abolish class-distinctions means abolishing a part of yourself,” that he was being compelled to “alter myself so completely that at the end I should hardly be recognizable as the same person,” and that while “you have got to drop your snobbishness… it is fatal to pretend to drop it before you are really ready to do so.” Such talk might seem hyperbolic, but a legion of philosophers contend that radical disruption of psychological continuity disrupts personal identity. Orwell’s preferred, less hostile strategy appealed instead to native English patriotism to recruit potential allies, one that his first wife, Eileen, understood when she explained that his short book, The Lion and the Unicorn, was his attempt at “explaining how to be a Socialist though Tory.” It did not demand the seriously difficult task of abandoning one’s self-conception, but instead culled existing sentiments to overcome class differences.

If Orwell’s preferred strategy seems obvious, consider how bad the American Left sometimes seems at this sort of thing. Frequent appeals to the value of diversity and equity have produced furious contrary reactions. Talk of “building back better” is pragmatic but seems to have fallen flat. Consider too a 22 May 2023 statement from Class Unity, a caucus within the Democratic Socialists of America, titled “Class politics, not identity politics” which contends that:

Neoliberalism seeks to separate us into a vast number of groups according to factors such as race, gender, religion, and country or region of origin. Divided, we cannot advance our collective interests as working people. Liberal politics embraces this division and creates a political landscape where every group fights for “its” interests… A true socialist politics

allows working people to transcend this atomization and join with each other not on the basis of who we are, but of what we do. And what the working class does is work, because otherwise we starve. It is only by organizing around our shared class interests and strategically withdrawing our labor that we can challenge capitalism.

The call to transcend atomized self-conceptions might be sincere, but it is bound to feel divisive, like a demand to abolish part of oneself. Could appealing sincerely to American patriotism work better? What if jargon-filled statements of principles were dropped in favor of “We’re Better than This” or “Out of Many, One: For Real This Time”? What if the American Left created propaganda incorporating images of insurrectionists pulling down the American flag from the United States Capitol? Might that better engage working-class and middle-class voters?

Orwell’s strategy might seem odd given he is so often read as the honest champion of telling uncomfortable truths. But he spent “two wasted years” producing war-time propaganda for the BBC and he told his fellow socialists that “we need intelligent”—that is, better—“propaganda.” Orwell still matters because he showed us how to turn our political tribalism on its head, never quite losing faith in the decency of human beings.

Featured Image by Ilse Orsel via Unsplash, public domain.

June 6, 2024

Behind the scenes: what it’s like to be a junior author for the OHCM

Behind the scenes: what it’s like to be a junior author for the OHCM

To mark the release of the much anticipated 11th edition of the Oxford Handbook of Clinical Medicine (OHCM), Oxford University Press spoke with the three new authors of this edition: Peter Hateley, a GP based in New Zealand; Dearbhla Kelly, a Critical Care Medicine fellow in Oxford; and Iain McGurgan, a Neurology Resident in Switzerland. The author team shared their experiences of writing the world’s best-selling medical handbook.

How did you get involved with being a junior author for OHCM?PH: I’d done some medical editing and journalism while at medical school. I really enjoy teaching and, in particular, the place where teaching meets writing. I loved reading the OHCM while at medical school, so I threw myself at the chance when I saw an advert online to be a junior author.

DK: I read a tweet from a previous author whom I greatly admire, in which she promoted the opportunity and described what a positive experience it had been for her. Like Pete, I also needed little encouragement as the OHCM holds a special place in my heart as the talisman of my (very) junior doctor days.

IMG: The OHCM is an institution that carried me through medical school and beyond; I couldn’t resist when I saw the call for applications! Funnily, Dearbhla and I worked in the same service at the time, but we didn’t clock that we had both applied until we had made the final cut many months later, when we asked one another to cover a shift at the exact same day and time (the final interview).

What were the best things about your experience as an OHCM author?PH: Working towards a book that provided so much enjoyment (and frantic revision material) for me personally, and for many more internationally. I had particular fun writing some of the more creative parts of the OHCM; as is the tradition, the book is peppered with asides that encourage thinking about the world from the patient’s perspective. The team at OHCM have been brilliant, a great source of support and knowledge throughout the process.

DK: I enjoyed getting to add new sections or pages that I vividly recall searching for in vain during my time as an intern! It was also a very educational and enriching experience to read the literature and guidelines across such a range of medical specialties. I too am grateful for the kindness and patience of all the senior authors and OHCM publishing team.

IMG: The opportunity to work alongside and learn from such an incredible team (co-authors, senior authors, specialist readers, junior readers, editors, and the publishing team at OUP). I had (and still have) a great deal of imposter syndrome!

And what were the most challenging parts?PH: As with most of our readers, we had the challenge of the pandemic and its aftermath to juggle alongside our other clinical work. This left our writing on the back burner for a while, and some updated guidelines to read on our return! It’s been a fun challenge reducing each topic to be most useful and relevant to our readers.

DK: Balancing pertinent detail with succinctness/word count limits! As Pete acknowledges, the pandemic-sized interruption in the middle of our writing created some challenges in terms of keeping the writing up to date since the nature of evidence-based medicine and best clinical practice is so dynamic.

IMG: Keeping the H in the OHCM! The temptation was always to add more and more material. I learned that it’s so much easier to write than remove.

How did you manage to juggle writing with your clinical work, studies, and home life?PH: With great difficulty! All my time planning went out of the window with the pandemic (the best-laid schemes of mice and men…). Making time for writing alongside exams led to a few long evenings of writing. It’s been a good lesson on balancing work and life a little better, and a reminder of the value of supportive family, friends, and colleagues!

DK: I am still looking for some suggestions! For me, it was forgiving family, friends, and colleagues.

IMG: My experiences were identical to those of Pete and Dearbhla above. Sleep was the ball the most frequently dropped for me. I felt it was too hypocritical to add a sleep hygiene section to the book, so that will have to wait until the 12th edition and a better time-managing author than me.

What tips would you pass on to aspiring Handbook authors?PH: In our digital age, information is often already there to be searched but can be dry to read. I’d suggest considering: how will my writing help people to really remember that information? More importantly, how will I incorporate the human, empathic core of being a doctor? I think the OHCM does that really well.

DK: Perfection is the enemy of good! The expert feedback of the specialist reviewers is also such a helpful and practical resource when wading through the waters of an unfamiliar medical specialty.

IMG: I tried to review my work as if I were reading it for the first time, frantically poring over every word on a trembling page on the eve of exam, or hiding out of sight of the ward round to assimilate some knowledge that I ought to have had already! This helped me to keep it (I hope) relevant, reliable, and readable.

Featured image by Free-Photos via Pixabay.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers