Oxford University Press's Blog, page 21

August 2, 2024

What’s the matter with moral fundamentalism?

What’s the matter with moral fundamentalism?

Inspired by fellow philosopher Anthony Weston, I often ask my ethics students to create a diabolical toolkit of rules that would torpedo public dialogue. The idea here, I explain, is to spell out rules that would maximize the distance between “us” and “them,” ensuring that possibilities for cooperatively setting and achieving social goals—like peace, security, justice, public health, or sustainability—go forever unnoticed. For example, consider things like “prepare your comeback instead of listening” or “be angrier and talk louder than others.”

I divide students into groups and ask each group to develop five more rules. They invariably come up with an excellent toolkit for sabotaging debate. For example: “stereotype the other side,” “be uncharitable: always present your side at its best and the other at its worst,” “ignore context,” “be smug,” “trust your anger; it would never steer you wrong,” “inflate certainty,” “assume your interlocuter is clueless” “reject complexity,” “be visibly offended by any questioning of your conclusions,” “approach any debate as a winner-take-all game,” “widen the gulf that separates us,” “act as though your values and concerns invariably overrule theirs.”

Gradually some of the fun fades as we reflect on our diabolical toolkit. Many of my liberal-identified students interpret the activity as a sendup of conservatives. Their imagined toolkit-users sport “Make America Great Again” hats and threaten DEI advocates. Meanwhile, many of my conservative students interpret the activity as damning liberal wokeness, virtue signaling, and cancel culture.

“Do you ever follow these rules?” I ask. This is a stretch for some of them, but most of us end up recognizing ourselves. “Have we learned anything from doing this?” The sense of the class is that we purposefully drew up a malicious playbook for undermining democracy, and it mirrored business-as-usual.

In my own writings on moral philosophy, I’ve come to call this cluster of toolkit-like habits “moral fundamentalism.” I’ll very briefly explore four questions about it: (1) What is it? (2) Is it really such a bad thing? (3) Is it good for motivating public action? and (4) Are we stuck with it?

1. What is it?More than a synonym for moral absolutism, a moral fundamentalist may be defined, minimally, as someone who acts as if they have access to: (1) the exclusively right way to diagnose moral or political problems and (2) the single approvable practical solution to any particular problem.

The word “fundamentalism” automatically calls to mind rigid religious dogmatism, which carries the idea that a select few have accessed ideals that should be heeded without public investigation, critique, and reformation. Like its religious counterpart, moral fundamentalism isn’t a promising resource for public dialogue, restoration of trust, or reconciliation. It’s a resource for reactionary oppression, rage, and fanaticism on all sides. We must find our diverse ways beyond the hell we inflict in the name of righteous certainty.

2. Is it really such a bad thing?For a moral fundamentalist, the main moral, social, or political problem is presumed to be that others don’t get the problem, as though events carry their own meanings. Or the main problem is presumed to be the failure of others to bow to our brilliant solutions—never mind aspects of the situation that may be obscured by our way of casting the problem or hidden by our principles. We too readily assume that, unlike their concerns, ours are value-neutral and free of interest-driven rationalizations and biases. We never doctor facts to predetermine results.

Moral fundamentalism is a drag on democracy. This drag is to be expected when people feel backed into a corner, or when their social position limits opportunities. But fundamentalism anywhere blocks communication and inquiry across differences. Whenever people suppose their reading of a problem is exhaustive, they autocratically predefine what’s relevant and they covertly prejudge alternatives. They assume, as a matter of course, that others are stubbornly refusing to accept the interpretation that is staring right out at them.

When we disagree about problems, it’s one thing to reflectively conclude that others are willfully refusing to face conditions. It’s quite another thing to start with the default assumption that we alone are taking the wide view.

Despite these habits—not because of them—moral fundamentalists have historically done many good things through their dealings with opposing fundamentalisms. But what else have they done that might in future be minimized by delegitimizing moral fundamentalism? When we take up the one-way mentality, what happens to opportunities for learning our way toward a healthier, more just, and more sustainable future across the dynamic spectrum of values, beliefs, and concerns?

3. Is moral fundamentalism good for motivating public action?We’re used to assuming that a kind of fundamentalism is the irreplaceable steam that powers activism and advocacy, that resistance to injustice is unintelligible without it, and that the virtues of moral clarity and conviction somehow imply a my-way-or-the-highway approach.

However, does activism actually require and benefit from moral fundamentalism? In order to motivate actions that restructure conditions and redress wrongs, must people harden their hearts and minds against the clamor of contradictory theories, both speaking and acting as if they’re governed by final truths?

This idea that incorrigibility is a virtue of activism and advocacy makes some dubious assumptions about the public. To some intellectuals, the international resurgence of gaslighting demagogues and self-seeking cronyism is incontrovertible proof that we can ultimately expect very little of the public. In that view, the public switch is permanently set to dim, and it’s up to intellectuals to take up the civilizing burden of enlightenment. If this requires us to proclaim finalities, then so be it.

Disagreements about what we can reasonably expect of a democratic citizenry have a long history, from Plato’s Republic to the Federalist Papers. The clearest modern statement of alternatives was arguably the debate in the 1920s between American philosopher John Dewey and journalist Walter Lippmann. Dewey rejected what he took to be Lippmann’s coziness with paternalistic rule by elite experts who oversimplify problems so that citizens will accept the reality that is bureaucratically packaged for them. Nothing made Dewey’s democratic blood boil more than Lippmann’s idea that intellectuals must lift the burden of inquiry from the provincial and parochial little heads of the masses while conferring the “mandate of heaven” on certain ideas.

Does Lippmann’s enlighten-the-masses outlook reveal intellectuals at their best? People cling to the illusion of ironclad certainty, and Lippmann exploited that illusion. Dewey’s alternative, in contrast, was to free public intelligence to creatively direct change. Accordingly, he focused throughout his life on the educative capacity of human experience. He argued that prophecies of public incompetence are self-fulfilling. We’ve expected too little of the public, and these low expectations continue to exact a heavy price.

4. Aren’t we stuck with moral fundamentalism?Yes, but its shape and extent are educable. Moral fundamentalism is at odds with the greatest educational need in any democracy. Drawing again from Dewey, that need is to improve “the methods and conditions of debate, discussion and persuasion. That is the problem of the public.”

Moral fundamentalism is a vice because it obstructs communication, constricts deliberation about what’s possible, and underwrites bad decisions. Social inquiry is more honest, collaborative, rigorous, and productive when youths learn to be patient with the suspense of reflection, open to discomfort and dissent, resolute yet distrustful of tunnel-vision, aware of the fallibility and incompleteness of any decision or policy, practiced in listening, and imaginative in pursuing creative leads.

We should teach students to value friction, and we should help them become compassionate, active, and informed problem-solvers. Instead of teaching them to oppose others’ fundamentalism with more of the same, we need a more genuinely radical approach that is not Pollyannaish. We need democratic engagement and resistance without puritanical zealotry, courage in mediating troubles without certainty, bold action without fatalistic resignation or paralyzing guilt, and moral clarity without oversimplification.

Featured image by George Bakos via Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

Racism, jazz, and James Baldwin’s “Sonny Blues”

Racism, jazz, and James Baldwin’s “Sonny Blues”

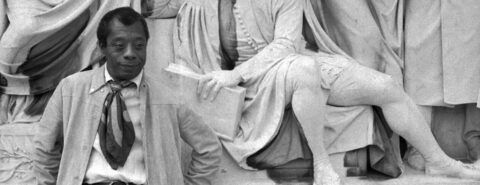

Reading is good; rereading is better. I can’t say with certainty how many times—forty? fifty?—I’ve read James Baldwin’s “Sonny’s Blues,” only that for more than thirty-five years I’ve been reading and teaching the story, each time with an undiminished sense of awe and appreciation for how Baldwin issues a prophetic warning about the outcome of racism while making deeply felt gestures of hope and reconciliation.

As the title indicates, the story moves on its music, specifically jazz. Whenever I read “Sonny’s Blues,” I think of John Coltrane’s “A Love Supreme,” a long, prayerful piece that gives thanks for his recovery from heroin addiction and that percussively, sonorously refrains its title in praise of the Creator. Coltrane’s song dates from 1963, a few years after “Sonny’s Blues,” and both pieces take part in a shift occurring in race consciousness and the American psyche. “A Love Supreme” proceeds in four parts—a similar orchestration to “Sonny’s Blues,” which occurs in three acts with a denouement and begins with a song of denial:

I read about it in the paper, in the subway, on my way to work. I read it, and I couldn’t believe it, and I read it again. Then perhaps I just stared at it, at the newsprint spelling out his name, spelling out the story. . . .

It was not to be believed and I kept telling myself that . . .

The occasion of “Sonny’s Blues” is that a long-standing denial of a horribly painful truth has come home to the main character and can no longer be denied, though he tries. Having established this conflict, Baldwin promptly reveals the news: the narrator’s younger brother, Sonny, a jazz pianist, has been arrested for using and peddling heroin. From that moment, the story proceeds with forthcoming directness. What’s at stake is life and death.

In the 1950s the New York City rate of death from heroin use for Black users was as much as two times higher than for white users, and the median age of those who died was twenty-seven. Baldwin would have been all too aware of mortality even in youth, as in the course of his lifetime, he survived several suicide attempts. In an essay titled “The Uses of the Blues,” he writes:

I’m talking about what happens to you if, having barely escaped suicide, or death, or madness, or yourself, you watch your children growing up and no matter what you do, no matter what you do, you are powerless, you are really powerless, against the force of the world that is out to tell your child that he has no right to be alive. And no amount of liberal jargon, and no amount of talk about how well and how far we have progressed, does anything to soften or to point out any solution to this dilemma. In every generation, ever since Negroes have been here, every Negro mother and father has had to face that child and try to create in that child some way of surviving this particular world, some way to make the child who will be despised not despise himself.

In the early 1980s, when Toni Morrison was winding up sixteen years at Random House as a groundbreaking editor of Black authors, I was dismayed to hear various publishing personnel repeat the conventional wisdom of that era: Black people don’t buy books. It also meant that publishers were reluctant to spend money to support and publish work by Black writers, making it hard for those writers to find an audience. And going back to 1957 and Baldwin’s advent, how much more prevalent this conventional notion would have been and how very aware of it Baldwin would have been, taking into account the need to form his work in such a way as to summon an audience by touching readers of all kinds.

Wynton Marsalis has been credited with seeing jazz as a solution to a shared cultural mythology between Blacks and whites that can help move the needle on race relations. Baldwin employs this kind of perception in writing “Sonny’s Blues.” Throughout the story, readers aren’t necessarily aware of hearing jazz or blues in the scraps of sound that will ultimately crescendo in a transcendent performance at a Village nightclub, but that’s where the story will finish. Near the end, Baldwin’s narrator notes that not many people ever really hear the music they listen to:

And even then, on the rare occasions when something opens within, and the music enters, what we mainly hear, or hear corroborated, are personal, private, vanishing evocations.

And it can also be said that not many people actually see what they’re looking at. Look, Baldwin was saying, this is how things are, and he wrote with the knowledge that change would be hard and slow to achieve. Across the sixty-five years since the story’s first publication, it has been assigned and taught in secondary schools and in colleges and universities throughout the world, ultimately reaching and moving many millions of readers to new awareness. Some things have changed for the better; some things have worsened; there’s still work to do.

When teaching “Sonny’s Blues,” I sometimes manage to get all the way through the lecture without letting my voice break or my tears well, though never without some students’ tears. But what are these tears? Grief, of course, at the terrible suffering. Wonder at the endurance required for survival and self-respect. Sorrow and joy mingled when the vulnerable heart’s truth is called forth, touched and held without sentimentality. Gratitude for Baldwin’s art.

Featured Image ‘James Baldwin on the Albert Memorial with statue of Shakespeare’ by Allan Warren via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

August 1, 2024

8 must reads in sport history [reading list]

8 must reads in sport history [reading list]

Human civilization has always celebrated movement. Whether as recreation in everyday life, or elite competition to honour the gods of Olympus, sport has been a cornerstone of human culture for both spectator and competitor since records began. From the cricket crease to the athletics track to the All England Lawn Tennis Club, discover the history of sport in 8 books and bibliographies from Oxford University Press.

1. The Oxford Handbook of Sports History

Orwell was wrong. Sports are not “war without the shooting,” nor are they “war by other means.” Although sports have generated animosity throughout human history, they also require rules. Those rules limit violence, even death. Thus, sport has been a significant part of a historical “civilizing process.” As the historical profession has taken its cultural turn over the past few decades, scholars have turned their attention to a subject once seen as marginal.

2. Cricket Country: An Indian Odyssey in the Age of EmpireRead more in The Oxford Handbook of Sports History edited by Robert Edelman and Wayne Wilson.

Cricket is an Indian game accidentally invented by the English, it has famously been said. But India was represented by a cricket team long before it became a nation.

Conceived by an unlikely coalition of imperial and local elites, it took twelve years and four failed attempts before the first Indian cricket team made its debut on the playing fields of imperial Britain. Drawing on an unparalleled range of original archival sources, Cricket Country is the story of this first ‘All India’ national cricket tour of Great Britain and Ireland. It is also simultaneously the extraordinary tale of how the idea of India took shape on the cricket pitch long before the country gained its political independence.

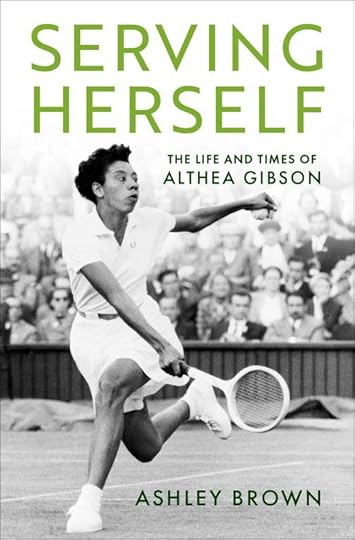

3. Serving Herself: The Life and Times of Althea GibsonLearn more about the first Indian cricket team the Cricket Country: An Indian Odyssey in the Age of Empire by Prashant Kidambi

From playing paddle tennis on the streets of Harlem as a young teenager to her eleven Grand Slam tennis wins to her professional golf career, Althea Gibson was the most famous Black sportswoman of the mid-twentieth century. In her unprecedented athletic career, she was the first African American to win titles at the French Open, Wimbledon, and the US Open. This book narrates the public career and private struggles of this fascinating athlete.

4. Classical SportLearn more about the life of Althea Gibson in Serving Herself: The Life and Times of Althea Gibson by Ashley Brown.

Sport was a key fixture in the classical world, from the Bronze Age to late antiquity. In the Homeric epics, competition in a number of events (including running, discus, jumping, and chariot racing) is presented primarily as an elite activity that is integrated into the Homeric aristocratic ethos of masculine valour and peer interaction. Archaeological, literary, and epigraphic evidence unequivocally suggests the rapid growth and popularity of competitive sport in the centuries that followed, demonstrated by the ancient Olympic games in 776 B.C. for example. Containing research on athletics, boxing, chariot racing, and gladiatorial games, learn more about ancient sport in the Oxford Bibliography of Classics.

5. Body by Weimar: Athletes, Gender, and German ModernityRead Classical Sport on Oxford Bibliographies Online.

Body by Weimar argues that male and female athletes fundamentally recast gender roles during Germany’s turbulent post‐World War I years and established the basis for a modern body and modern sensibility that remain with us to this day. Athletes in the 1920s took the same techniques that were streamlining factories and offices and applied them to maximizing the efficiency of their own flesh and bones. Sportswomen and men embodied modernity—quite literally—in all of its competitive, time‐oriented excess and thereby helped to popularize, and even to naturalize, the sometimes threatening process of economic rationalization by linking it to their own personal success stories. Enthroned by the media as the new cultural icons, athletes radiated sexual empowerment, social mobility, and self‐determination.

6. An English Tradition? The History and Significance of Fair PlayRead Body by Weimar by Eric Jensen on Oxford Academic

For hundreds of years, English people have claimed that fair play is at the core of their national identity. Jonathan Duke-Evans explores the origins of the idea of fair play, tracing it back to the classical world and the Dark Ages, and finding its genesis deep within England’s social structure. Charting its early development through both the tales of chivalry and the stories of popular legend, the book shows how fair play manifested itself in literature, the law, the Christian religion, and the family.

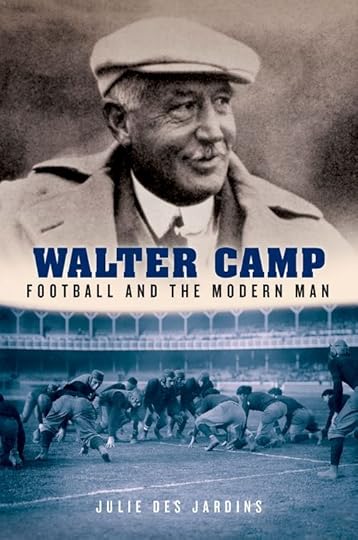

7. Walter Camp: Football and the Modern ManLearn more about the history of fair play in An English Tradition by Jonathan Duke-Evans

To a handful of colleagues, Walter Camp was a clock company executive. To nearly everyone else, he was the quintessential gentleman athlete and the Father of American Football. Born in Connecticut in 1859, he attended Yale University just as collegiate sport was becoming organized and competitive in the United States. In college, he was a varsity letterman who led the earliest efforts to codify the rules of football and to make it distinct from English rugby. As the creator of the All-America football team and the writer of some of the first football fiction, guides, and sports page coverages, Camp popularized the game like no other.

8. Medieval Sport and GamesLearn more about Walter Camp’s life in Walter Camp: Football and the Modern Man by Julie Des Jardins

Some sports in the Middle Ages, such as tournaments and hunting, were monopolized by the nobility and gentry and acted as marks of status. However, archery and ball games were common throughout society, and common people encroached on hunting through poaching. The most physical sports tended to be dominated by men, but some women used bows; both genders socially joined in music and dancing.

Discover a comprehensive list of research into medieval sport in The Oxford Bibliography of Medieval Studies.

Featured image Jakub Matyas via Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

July 31, 2024

Two nonidentical twins: rump and runt?

Two nonidentical twins: rump and runt?

Rump and runt are not twins, but they sound somewhat alike, and they may be “distantly related,” to use a phrase sometimes occurring in dictionaries, though this phrase is too vague to be useful. Rump surfaced in texts only in the fifteenth century, and but for the Rump Parliament (1648-1653), famous in British History, the word would probably have been relegated mainly to talks about animals and birds. Since rump made such a late entry into English, it may have been a borrowing. Indeed, its source is often believed to be Scandinavian, but the picture needs clarification, because the obvious cognates of rump are also well-known in other Germanic languages. Thus, German Rumpf and Dutch romp mean “torso, trunk, body,” and they are certainly not loans from Scandinavian. Modern Icelandic rumpur is probably a borrowing from Danish. The latest edition of the main German etymological dictionary says at Rumpf: “Origin unclear.”

Not only the sound-imitative verb rumble (a rootless word) but also the name of the German fairy tale dwarf Rumpelstilzchen (Anglicized as Rumpel-stilt-kin) is close by. This tale appears in the famous Grimms’ collection. The name probably means “rumbling stilts.” Most of our readers know the story, but, just in case, I’ll briefly retell it. A stupid man tells the king that his daughter can weave straw into gold. The king takes the claim seriously, and the poor girl is brought to the palace. There, she is locked in a room full of straw and told that unless she can live up to her father’s promise, she will die. Otherwise, the king will marry her. A mysterious dwarf appears. He vows to fulfill the impossible task if she gives him some presents, though why someone endowed with such a gift needs presents is unclear. She agrees. The greedy king cannot stop, and the ordeal is repeated two more times. But the girl runs out of precious objects on her. On the third night, she has nothing to give the dwarf and is made to promise him that as a reward she will part with her firstborn. Again, we are in the dark about why the dwarf needs the baby. She is saved, becomes Queen, and gives birth to a boy. The dwarf returns for his reward. She pleads for mercy, and he finally agrees to relent if she guesses his name in three days.

A beautiful rump in sharp relief.

A beautiful rump in sharp relief.Image by World Wildlife via StockSnap. CC1.0.

The plot is as old as the hills. Knowing one’s name meant having full control of the person, but we need not delve into folkloristic depths, though, perhaps unwittingly, the tale (it will be noticed) brings out the idea that there is no fool like an old fool. One fool is the heroine’s father. The other is the dwarf. Nobody can guess his name, but on the third day, someone spots the dwarf and overhears him singing boastfully that his name is Rumpelstiltzchen and will remain hidden forever. The queen tells the dwarf his name, and he bursts in fury.

This odd name is not only impossible to guess but hard to interpret. Yet in English dialects, rump has been recorded as meaning “a cow with bones sticking out.” Not improbably, rump, in addition to meaning “torso” and “backside,” could also refer to protruding bones and the coccyx. I will venture the guess that Rumpelstilzchen, like so many folklore ghosts, was named for being able to rattle his bones and frighten people. According to an old suggestion, which I, naturally, like, the word rump first meant “tree stump.” Therefore, my guess may be correct. The same holds for the idea that rump is related to such Slavic words as Russian rubit’ (stress on the second syllable) “to cut, hew.” Cutting wood is a noisy activity, and the result is of course a stump. Rumpus “commotion,” a late eighteenth-century “fanciful formation,” is unrelated but what an apt one, as far as sound imitation is concerned!

Woodcutting is a noisy activity.

Woodcutting is a noisy activity.Image by Pavel Danilyuk via Pexels.

No one knows what exactly the Old Icelandic derogatory nickname rympill meant. Perhaps it should be glossed as “badass,” which returns us to rump. Above, I said that since rump surfaced in English so late, it may have been a borrowing. But perhaps a vulgar word for “hind quarters” was part of common Scandinavian-North-West Germanic slang, and I need not dwell on a possible connection between one’s posterior and auditory effects. My point is that despite all the uncertainties, the complex rump– ~rumb– ~ ramb– gravitates toward “noisy” words and is possibly onomatopoeic.

Now lo and behold! Runt, which also made its way into English books more or less at the same time as rump, means in dialects “an old tree stump.” It still means roughly the same (“the stem of a plant”) in Scotland. Those English speakers who use the word runt may mainly remember its sense “the smallest of a litter of pigs” (like Wilbur, a doomed and rescued pig in E. B. White’s book Charlotte’s Web). Rumpelstilzchen was also a dwarf. The conjectures about the origin of runt are few and unpromising: mere guesswork. An obsolete English word rother “ox” is cognate with German Rind and Dutch rund and means “cattle.” Runt and rind have sometimes been compared, and Ernest Weekley defined runt as “small cattle,” but the senses do not match too well. Old Icelandic hrinda meant “to push, throw, drive.” This verb is part of our story only if runt is a very old word that once began with hr– (such words are numerous: outside Icelandic, that is, in West Germanic and in the continental Scandinavians languages, the initial h has been lost before consonants). But runt need not be old. Animal names are often sound-imitative, and perhaps runt is one of them. I am not impressed by the runt-rind connection.

Today a runt, tomorrow a prizewinner.

Today a runt, tomorrow a prizewinner.Image via PickPik.

Runt has been more or less given up as a word of unknown origin, and I have no arguments to prove or even suggest its connection with rump, but they may be close. No definite solutions present themselves, though perhaps my ideas on rump are a bit more convincing than those on runt. Be that as it may, when one comes to think of it, rump and runt emerge as having a similar phonetic structure (nt consists of two sounds articulated in the same part of the mouth, and so does mp: such consonant groups are called homorganic), and both words share a suggestive abut obscure past.

A postscript to the previous post

A reader asked me why I had rejected the Indo-European root of the word whale. If it is true that the word is Nostratic, then its root is pan-human, so to speak. But if some old word for a sea monster (a whale or a shark, or any other big fish) migrated from land to land, then again we end up with a “rootless” vagabond. This was my reason for staying away from Pokorny’s root. I also recommend our readers to have a look at a comment about Australia and New Zealand, following the post of a week ago. I, of course, copied my information about a beached whale from a newspaper.

Featured image by thecmn via Flickr. Public Domain

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

July 29, 2024

Diary of a dead man

This blog post introduces readers to the well-traveled remains of an Egyptian mummy now residing in Houston, Texas. If old Ankh-Hap still had his original hands and an endless supply of papyrus, he might have made entries like these in a diary of his afterlife.

29 July 1987Dear Diary,

I traded coffins today. I left behind the comfortable wooden box that had cradled my remains for the past twenty-three centuries. I feel a bit lost without it. Ancient mourners had listed upon its lid the essentials of my being, including my name (Ankh-Hap, son of Ma’at Djehuty) and my eternal needs (bread, beer, wine, milk, meat, oil, and incense). In brilliant colors, it pictured the gods who have guarded my afterlife and the rituals of my resurrection. It recorded all that I was and would ever be: a transitory man and then a mummy.

My new coffin is larger but less personal, the product of another time and place that worships Science instead of Osiris. Its priests have sealed me inside a casket they call a CT-Scanner. This modern metalloid coffin promises me no food or drink; it does not even know my name. Yet, I sense it searching my deepest self, probing for secrets my wooden one has refused to share. What lies hidden beneath my linen wrappings? The whole world is about to know.

I am a physical wreck. The priests see in the shiny coffin that I have wasp nests in my skull. There are seven wooden slats rammed through my body from head to ankles. I have partial limbs and fake ones too. Most of me is missing between my head and my hips, an inexplicable void filled by just a few ribs and vertebrae. No one yet knows how, when, or why this happened. Was I the victim of a crocodile attack or perhaps a chariot crash? Did tomb raiders despoil my body in search of loot and then leave me to be pieced together and reburied? Could my condition be the result of a modern crime? Am I even Ankh-Hap at all, or just a Franken-mummy who was stuffed into a stolen coffin? Is one casket calling the other a liar? This has been an unsettling day.

29 July 2024Dear Diary,

Many Wep Renpets have passed since my week-long sojourn inside that second coffin. It was an experience that changed my afterlife. Resting again in the one of wood, I peep out at throngs of modern admirers—or should I call them mourners? They do not seem sure how to respond to my updated obituary. I was a man of some means but not of high status; neither of my coffins support old rumors that I was a tax collector or a prince of royal blood. I was about forty when I died, with signs of osteoarthritis and episodes of stress-related anemia. I most certainly did not go to my grave with wasps in my head or with sticks where my bones should have been.

When carbon-dated, the wooden braces inside me proved to be modern, showing that my body was ravaged and then repaired during the mummy craze of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. That’s when an American entrepreneur dredged me from the infamous mummy-pits of Egypt. His company openly trafficked in mummies and mummy parts, selling assorted arms, legs, heads, and whole bodies at bargain prices to all and sundry. That’s how my wooden coffin and I (yes, I am its rightful inhabitant) came to Texas, where I spent some time in a traveling show, a university lecture hall, and an abandoned campus bathroom. Sadly, people forgot I was there, allowing those worrisome wasps to colonize my cranium. Fortunately, I was rescued and now repose in a marvelous temple called the Houston Museum of Natural Science. Its priests and patrons keep me and my coffin safe within a shrine that now links the religions of Science and Osiris.

All of these details and more appear in a new book about my life and afterlife, titled A Mystery from the Mummy-Pits: The Amazing Journey of Ankh-Hap (Oxford University Press, 2024). In its pages, author Frank L. Holt makes the most of what my two coffins reveal about me. I just love being buried in a good book.

Featured image by Dmitrii Zhodzishskii via Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

Goethe in shirt-sleeves

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe is Germany’s greatest poet, then and now. At the age of thirty-seven he was on the way to being the centre of a national culture, and a European celebrity. But at the moment (in 1786), he is simply on his way to Italy, a journey that was nothing grand or official. He is escaping as a private individual under a cover-name—escaping, on one level, from a decade labouring to help administer Weimar (one of eighteenth-century Germany’s mini-states), and, on a more intimate level, from an emotional entanglement with Charlotte von Stein, a married lady nine years older who is a prominent member of Duchess Anna Amalia’s court.

Over his early time in Weimar, Charlotte had helped this rough-diamond bourgeois writer to find his feet in an unfamiliar aristocratic scene. His gratitude shaped a close relationship between them—a love affair even? The clerihew is well-known:

Charlotte von Stein

went to bed at nine.

If Goethe went too,

nobody knew.

But surely in that tightly enclosed society, everybody would have known? Everything we do know about Charlotte’s character and life experience makes this affair unlikely. Yet Goethe’s letters, almost two thousand of them, often informal notes punctuating the day, certainly speak of love. Hers haven’t survived; she demanded them back when the relationship soured, which began with this Italian journey. So, the picture remains incomplete.

Goethe has left Weimar and the court behind him, telling no-one where he’s going, not even Charlotte, to her great resentment. But he does stay residually in touch, slipping in assurances of his love with successive batches of his travel diary. So at least she does know where he is now, though she may have been left cool by his reports. His clear enthusiasm surely signalled that he was in every sense moving beyond her.

It is a happy return after the decade of frustrated creativity in which several works were begun but none finished.

Those batches, thrown down almost daily over the eight weeks it took him to reach Rome are our text. Goethe never published it, didn’t think much of it, and many years later used it when writing the full formal account of the nearly two whole years he spent in Italy. It’s a surprise he didn’t then throw it away. That makes it the more precious, because it really is a work in itself: exuberant, charmingly informal, and spontaneous, shaped by a growing excitement as Rome comes tantalisingly closer.

And then—almost unbelievably, after years of longing and two missed opportunities—he is finally there. It feels like a destiny fulfilled, and his simple words “I am Goethe” when he meets his host in Rome, the painter Tischbein, convey the confidence in his restored free self. It is a happy return after the decade of frustrated creativity in which several works were begun but none finished.

Rather than finishing these works, he starts from the beginning, opening himself up to a world he knew from texts and images but is only now experiencing with all his senses and faculties. He sometimes feels overwhelmed by the realities pressing in on him from every side—landscape, climate, the cities on his route (Verona, Padua, Vicenza, Venice), ancient monuments, Renaissance art, Palladio’s architecture, history under every stone; and a new kind of people with an easy-going, out-of-doors, communal way of life. Among them he finds himself relaxing too, sloughing off the depression he had been suffering from under grey northern skies. He sums it up gratefully as a rebirth.

Material enough for a happy time—a happiness not of self-indulgence, but of a powerful mind fully and rewardingly engaged once more with the world—Italy was to remain a cherished memory, a pivotal moment in his life and career, and an inspiration for a new aesthetic in the years to come.

Featured image by Clay Banks via Unsplash. Public Domain.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

July 24, 2024

A whale of a blog

The title of this post embodies everything I despise about cheap journalism, but the temptation was too strong, because today’s topic is indeed the origin of the word whale. I was planning the story for quite some time, and then suddenly the media informed the world that a spade-toothed whale had been washed up on South Island beach (Australia). The habits and the anatomy of this species are completely unknown, so that a tragedy for the beast will be a great boon to scholarship. The newspaper article tipped the scale, and I decided to contribute an etymologist’s mite to the study of the word, nearly as mysterious as the spade-toothed whale. Those interested in the etymology of the even more mysterious word shark will find my discussion in the posts for May 23, 2012, and December 6, 2023. Sharks will also float to the surface below, if only briefly.

Unlike shark, whale is an old word in English, and it sounds similarly in all the Modern Germanic languages: German Walfisch (that is, “whale-fish”), Dutch walfis, and Icelandic hval(u)r. One should not treat such odd compounds as whale-fish lightly: people probably took whales for very big fish. Also, the idea of a “whale fish” occurred to other inhabitants of Eurasia. For instance, in Russian folklore, the whale is called ryba–kit (ryba fish” and kit “whale”; the world is said to stand on it), that is, German Wal-fisch in reverse order. This reordering of a compound’s elements is also common. For instance, the root of the word whale can be recognized as the first element of English walrus. The element –rus is akin to the word horse, so that walrus (eventually, from Dutch) means “whale-horse,” while the genuine Old English form was horsc–hwæl, like Old Icelandic hross–hvalr, that is, “horse-whale.” Kit in ryba-kit is a borrowing of one of the Greek words for “whale,” namely, kētos, which also meant “sea monster; seal; tuna.”

This is a sheatfish, not a whale, but opinions differ.

This is a sheatfish, not a whale, but opinions differ.Image by Bernard Dupont, USFWS Fish and Aquatic Conservation via Flickr. CC BY-SA 2.0

As far as we can judge, the remote ancestors of those who spoke the oldest Germanic languages had never seen whales. If the word whale had been coined by the Vikings, it would probably have been more transparent. Assuming that whale was taken over from the speakers of some distant land, our main support will be the German fish name Wels “catfish” or perhaps “sheatfish.” The Scandinavians may have known a similar name, but it turned up in texts only in German and only in the fifteenth century. Supposedly, the oldest form of Wels was hwalis. If so, it is related to Old Prussian kalis (Old Prussian is a Baltic language!), and again supposedly, this name was transferred to the otherwise new sea creature. Some catfish are quite big. Those who cite Wels wonder whether the fish was called after the whale or the whale after the fish! As just mentioned, the word Wels is late, it has no cognates in Scandinavian, and there is no certainty that it ever had h- at the beginning. But kalis will soon swim up in an entirely new light.

According to another predictable idea, the Germanic word for “whale” was borrowed from some foreign language. First come Latinsqualus “shark” or “some other big fish” and Latin balæna “whale.” Balæna resembles Greek fálaina. Probably both the Greeks and the Romans took over those words from their Illyrian neighbors, though the Romans believed that they had borrowed the name of the whale directly from Greek. Squalus, which may be related to squatus (another fish name), does look like a more or less probable cognate of whale, except that its origin is also unknown. Greek ‘aspalos, a rare and obscure word, and Sanskrit khāla, both fish names (though khāla seems to be a freshwater fish), have also been pressed into service and are members of the same etymological aquarium. The great German etymologist Friedrich Kluge compared whale and Greek pélor, another name of a sea monster. (I’ll skip phonetic details, because they won’t lead anywhere.) As could be expected, none of the proposals, mentioned above, has been accepted as definitive, though the most authoritative dictionary of Indo-European cites the reconstructed root squalo-.

This form requires an explanation. At one time, before the appearance of the first written documents, the language we call Germanic underwent a consonant shift. For example, Latin has quod (read: kwod), while its Old English cognate has hwæt “what.” (The consonants p and t underwent a similar change, but they need not concern us here.) That is why when etymologists look for forms related to Old English hwæl– “whale,” they try to find promising non-Germanic (Greek, Latin, Slavic, Celtic, and so forth) forms beginning with k-. The root squalo, that is, skwalo-, has the desired k, while initial s is the ubiquitous s-mobile (mobile s), an enigmatic prefix that appears in numerous words for the reasons that have never been explained to everybody’s satisfaction.

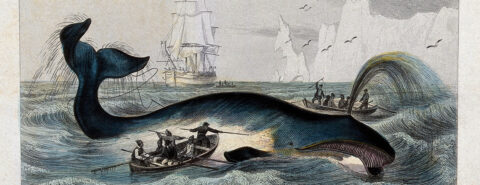

Whales escape hunters. Etymologies do too.

Whales escape hunters. Etymologies do too.Credit: From the Oxford World’s Classics edition, photo by Dave Cassar. Used with permission.

Despite all those wanderings over the map of the world, there have been attempts to connect whale with some native Germanic words. Walter W. Skeat referred whale to the root of the word wheel. One of the Old English forms of wheel was hweowol, not too different from hwæl. Whale emerged from this hypothesis as “roller.” Another ingenious reconstruction traced the name of the whale to a verb meaning “to draw back to recoil.” Those are very old ideas. Everybody who has at least opened Moby Dick knows that the book begins with a page, called “Etymology.” It contains quotations from dictionaries by Webster and by Richardson: “The animal is named from roundness or rolling; for in Dan. hvalt is arched or vaulted” and “It is more immediately from the Du. and Ger. Wallen; A-S Walw-ian, to roll, to walkout.” Moby Dick was published in 1851, and Melville had no better authorities to consult. Later, Skeat offered a rather improbable Greek etymon of whale. As a postscript, some dictionaries state that Old Norse hvalr made its way to the Finno-Ugric world: Finnish has valas and Estonian has vaal.

The case seems to be closed, but at the last moment, a nearly fateful complication arises. For more than a hundred and fifty years, etymologists have been citing Finnish kala “fish,” along with Prussian kalis, in connections with the Germanic word for “whale.” Prussian, as noted, is a non-Germanic Indo-European language, so that initial k in kalis arouses no suspicions, but Finish is not Indo-European! Yet kala, like kalis, has k-. And the Korean for “whale” is karia, that is,nearly the same form as in Finnish. The word seems to be Eurasian, rather than Indo-European, or as linguists say, Nostratic (this term was coined by the great Danish scholar Holger Pedersen and is now widely used in historical studies). Below, I am rephrasing the conclusion by Martin Sevilla Rodriguez. Indo-European peoples, he suggests, while migrating toward the west, took with them the word that sounded approximately like (s)kwalos or (s)kwalis, which designated in their lexicon a large fish, the biggest freshwater fish being the sheatfish, which in today’s German is called Wels. Later, they continued using the term wherever the sheatfish occurred. In other places, the name stuck to other big fish (sharks, for example) and ended up as “whale-fish.” (In light of such facts, Latin squalēre “to have a rough surface (skin),” also suggested as related to whale, is out of the game.)

Image 1: And here is a whale-fish!

Image 1: And here is a whale-fish! Image by Pixabay, via Picryl. CC0 1.0.

Image 2: A pleasant walk, a peasant talk / Along the briny beach.

Image via Picryl. Public domain.

This is a reasonable hypothesis, which survives in the margin of a more traditional etymology of the word whale. The riddle has not been solved, but some obscurity may have been dispelled. Among other things, we have no idea why the complex squal– was chosen as the name of a sea monster. Not sound–imitative and, seemingly, not sound-symbolic. Yet we are a step above the verdict: “Origin unknown.”

Correction. A reader has pointed out that I should not have used sword and board as rhyming with broad. At most, the rhyme exists in the r-less varieties of English. I should have used words like pawed, cawed, overawed. Sorry!

Featured image: A whale being speared with harpoons by fishermen in the Arctic sea. Engraving by A. M. Fournier after E. Traviès. Wellcome Collection. Public domain.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

Abominable mysteries

One hundred twenty-five million years ago, the earth exploded with a kaleidoscope of color with the rapid evolution of flowering plants, the angiosperms. The explosion coincided with the rapid increase and diversification of bee species, the new artists of the landscapes. This presented Darwin with a special difficulty for his view of gradual evolution, his “abominable mystery”. Darwin eventually explained this adaptive radiation of plants and bees as a dialectical coevolutionary dance—coadaptation.

Image by Julia Margaret Cameron, via Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

Image by Julia Margaret Cameron, via Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.Bees have transformed the earth in geological time scales, but they continue to transform our landscapes today in timescales of decades, weeks, and hours by painting the hills and fields through their pollination activities. Honey bees pollinate about 1/3rd of the crops grown in the United States and, as a consequence, have shaped the agricultural industry. Honey bees are used because they are plentiful (up to 40,000 in a hive) and transportable. Crop pollination in the U.S. is “bees on wheels”: millions of colonies loaded onto trucks, transported sometimes thousands of miles, and dropped in fields needing pollination. Bees quickly relearn their new locations and begin foraging.

In California today, there are more than 400,000 hectares (each comprising of 280 trees) of almonds under cultivation. The total 112 million trees produce 3 trillion flowers (28,000 each), in turn producing 750 billion almonds—double the numbers from 30 years ago. The flowers are pollinated by 60 billion bees transported from across the U.S. After a flower is pollinated, its petals fall to the ground and, along with the fresh flowers, paint the Central Valley of California with a white and pink ribbon 600 km long that lasts about 4-6 weeks in the early spring.

About 335,000 hectares of alfalfa are grown in California. Fields of seed alfalfa, like almonds, extend up and down the Central Valley. Alfalfa seed production is totally dependent on bee pollination. Honey bees are reluctant to forage on the flowers because the reproductive parts are spring loaded and slap the forager on the head when the flower is first visited. The flowers lure them in with abundant nectar: 2,000kg of it per hectare. Hives of bees are placed in groups on the ground in the alfalfa fields. New flowers open in the morning and are deep purple in color. Once the flowers are pollinated, they rapidly senesce and turn pink. You can look across a field of alfalfa in the morning and see where the bees have been foraging near the hives. The field is painted with bands of purple and pink extending out from the groups of hives; bees pollinate the closest flowers first. The painting begins again the next morning with a new canvas of fresh flowers.

Image by Raygday, via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 3.0.

Image by Raygday, via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 3.0.A new “abominable mystery” looms today. In 2006, beekeepers reported losing up to 90% of their colonies, with no explanation. Since then, they have continued to lose more than 850,000 of the 2.6 million commercial colonies every year, which equates to about a third. Around the same time, reports came in about the decline in native solitary bees worldwide. There are about 25,000 species of bees—most are solitary. Some species can only exist by exploiting specific species of plant and the plants are likewise totally dependent on them. People started asking “where have the bees gone?” Natural history surveys showed that their numbers and diversity are dwindling. What is causing this widespread plague on bees? Research money flowed. Every week a new “one thing” cause was found, only to be refuted and/or replaced by the next. Causes included parasites and diseases, insecticides, pesticides, herbicides, and habitat loss. Mark Winston in his wonderful book Bee Time called the decline of honeybees “death by a thousand cuts”.

Habitat destruction and indiscriminate use of chemicals have reduced populations of wild bees, perhaps sending some native plant and bee species into a new dialectic dance, a vortex of extinction. Rachel Carson warned in her 1962 book The Silent Spring of the consequence of indiscriminate use of chemicals and neglect for nature: the loss of the sounds of nature. Perhaps a new warning should be issued against the loss of the colors and artists of our landscapes.

Featured image by proxyminder via iStock.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

July 23, 2024

Rediscovering Piano Time

It’s an eventful time in the OUP Music office—we’ve just sent to press the latest editions of our Piano Time method books by Pauline Hall. It’s always exciting to see the publication of a new titles, but these books feel extra special. We last updated the method books in 2004, with Pauline Hall herself spearheading the changes and providing new material. Sadly, Pauline passed away in 2015, but her books have remained consistently popular with teachers and students alike. We wanted to honour her vision and approach, while giving the books the update they deserve, both visually and pedagogically.

The journey to new editionsPauline’s family have been fully supportive throughout the process of creating the new editions and, importantly, felt sure that Pauline herself would have been thrilled to see her books living on in this way.

From the beginning, I was lucky enough to work with two fantastic content consultants—Janet Bullard and Dr Jeanette Gallant—who advised on the areas that required a fresh approach to suit today’s market.

We wanted to introduce a handful of new pieces to each of the method books and together we identified which of the existing pieces we felt could be replaced. We were well aware that many teachers have their favourites and tried to avoid losing any Piano Time ‘classics’ if we could! We also discussed other proposed changes to the books for reasons of pedagogy (changing the order of some material or introducing a technique more explicitly) or context (adding short background notes to explain certain terms or the history behind a piece).

Commissioning new works from composersThis is always one of the most exciting parts of my job, and our new contributors—Reena Esmail, William Chapman Nyaho, and Kristina Arakelyan—did not disappoint! While the pieces themselves may be simple, the process of writing to such a specific pedagogical brief is certainly not; the composers did an incredible job of creating pieces that ticked all the educational boxes while, most importantly, being great fun to play. All three composers were completely collaborative and happy to adapt their work to suit the precise requirements of the books, which made for a really wonderful end result—exactly what we were hoping for.

Editing and proofing the booksOnce the manuscripts were finalised, I handed the books over to our brilliant in-house editorial team, led by Managing Editor Laura Jones, who oversaw the process of editing and proofing the books, keeping to the original design where possible.

Working with the illustratorPerhaps the most transformative aspect of the new editions was working with the illustrator Rosie Brooks. We’d all fallen in love with Rosie’s style of illustration and couldn’t wait to see the characters she would create for our new books! We worked through stages of pencil sketches before Rosie delivered the final colour illustrations, which were set into the proofs by our typesetter Julia Bovee.

A musician as well as an artist, Rosie was such an enthusiastic and talented partner to work with, and the process really was a joy. I am sure her artwork will brighten the practice sessions of many generations of pupils to come.

Initial sketches of trumpeters and a bird from Piano Time illustrator, Rosie Brooks

Initial sketches of trumpeters and a bird from Piano Time illustrator, Rosie BrooksRosie’s cover illustrations were sent on to our in-house designer Marten Sealby, who had the tricky brief of updating some very well-known covers so that they felt fresh but also recognisable. I think he did a great job of achieving that balance.

Recording the piecesThe final piece in the puzzle was, for the first time, recording all the pieces in the method books. Naturally, we wanted to make sure that what we recorded reflected exactly what was written in the scores, so this was left until the end of the process. We asked the renowned pianist Michael Higgins to make these recordings for us—he did a wonderful job of bringing the pieces to life. I hope they will inspire many young pianists as they work through the new editions.

The thing that I’m most proud of is how much these new books have brought the whole team together. We all understand the importance of continuing Pauline’s work and I know every single member of our publishing team (as well as many others) contributed to the books in one way or another—a real team effort. I hope they are enjoyed by many new learners, and that teachers appreciate the updates to the new editions—and also what we chose not to change.

Please do let us know!

Featured image by Rosie Brooks.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

Data protection, the LED, and the evolving landscape of AI governance

Data protection, the LED, and the evolving landscape of AI governance

In May 2024, OUP attended the Computers, Privacy and Data Protection (CPDP) conference in Brussels where academics, practitioners, and policymakers from the fields of data protection and privacy, as well as politics and technology, gathered to discuss the latest in legal, regulatory, academic, and technological development in privacy and data protection. The theme of this year’s conference centred around the seemingly inescapable growth of AI and its increasing impact on all parts of our lives, cultures, and societies, and sought to ask the fundamental question: is AI governable?

We spoke to Franziska Boehm and Eleni Kosta, two leading scholars who co-edited The EU Law Enforcement Directive: A Commentary to get their thoughts on the evolving landscape of data protection and how this might inspire further research into the LED, what the European Parliament’s recent adoption of the AI Act might mean for the LED in the future, and the evolving landscape of data protection.

Please could you briefly introduce yourselves and the titles of your book?EK: I’m Eleni Kosta, a Professor of Technology Law and Human Rights at the University of Tilburg.

FB: And I’m Franziska Boehm, a Law Professor in Germany at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology and the Leibniz Institute of Infrastructure.

EK: And the two of us co-edited the commentary on the Law Enforcement Directive, which is Directive 2016/680 on the processing of personal data in the field of law enforcement, so it’s kind of the little brother of the GDPR.

What are you hoping readers will take from the book?EK: Because this is not a traditional book (it is a commentary), we hope that it will function as a source of guidance to all sorts of legal scholars, practitioners, judges, students, lawyers…

FB: Even police officers…

EK: Exactly.

And how do you think it might inspire future research in the area of the LED? What do you think are the areas that are evolving or that might require further research in the future? Or further guidance?EK: Case law.

FB: Yes, case law, but I also think automatic decisions and the connection between law enforcement and AI. The use of AI tools in law enforcement is a big topic I think, which we were discussing in the Europol panel. They said we should agree that AI should be used more in law enforcement—I don’t know whether we should agree exactly—but I think that automatic decisions in law enforcement is a special topic that requires more research.

And it’s obviously a fast-moving area, so there are challenges there…EK: Yes, because it took a few years for the EU member states to actually transpose the LED into their national legal orders, so now we see that more and more court cases appear, and then several of them reach the Court of Justice, which gives some guidance, and then there will be a need for further work.

You touched on it there, but what are your thoughts around the theme of the conference – AI governance, and is AI governable? How does that impact research around the LED?FB: As I mentioned, it will be an important topic, and we need more critical voices also to, let’s say, limit the use of AI in law enforcement a bit, because there are serious fundamental rights issues that come along with it, and I think that this is one part of this topic; the other side is the challenges that also arise via the use of AI, possibly also partly in law enforcement, and finding the right balance there.

EK: Also, the fact that we just got the approval of the AI Act by the Council yesterday [22nd May] makes the conference super timely. We were anticipating it—we are both members of the scientific committee—so we were thinking about it. Are data protection and AI closely related? Of course they are not overlapping, but they are certainly closely related, so I think that it’s interesting that the conference is opening up to that.

FB: Also, the interlinks between the AI Act and the Law Enforcement Directive—that will need further work as well very soon.

Featured image: Maximalfocus via Unsplash, public domain.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers