Oxford University Press's Blog, page 23

July 8, 2024

AI attitudes and behaviour: researcher profiles [interactive]

AI attitudes and behaviour: researcher profiles [interactive]

Researchers’ attitudes to AI vary significantly across career stage, subject area, and country. While 76% of researchers say they have used some form of AI tool in their research, our survey uncovered unexpected generational differences and polarised opinions on the impact of AI.

We recently conducted a survey of over 2,000 researchers to hear directly from the research community about how they are reacting to and using AI in their work. A statistical cluster analysis identified eight groups illustrating the spectrum of attitudes, from ‘Challengers’ (those fundamentally against AI), through to ‘Pioneers’ (those fully embracing AI). Click on the image below to learn more about these profiles.

Featured image by Cash Macanaya on Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

July 4, 2024

What can seventeenth-century sources teach us about living with climate change?

What can seventeenth-century sources teach us about living with climate change?

At the beginning of another summer that will likely prove to be the hottest in the planet’s recorded history, it is easy to feel like we are living through a moment without precedent in human history. But it’s a mistake to assume that our histories have nothing to teach us about living under climate change. In my work as a historian of religions, I explore the ways that the religious beliefs of common people during the early modern period were shaped by the Little Ice Age, a period of severe global cooling that peaked in the second half of the seventeenth century.

Rather than turning to orthodox or traditional religious authorities, common people in Europe and the Americas during the Little Ice Age largely turned to esoteric religious sources to make sense of their changing climate. They read and used texts like almanacs, devotional literature, and other popular writings that relied on Hermetic, alchemical, and astrological perspectives to interpret the world around them. What made these texts worthwhile to rural people living through the tumult of the Little Ice Age?

As scholars of esotericism have long suggested, the basic perspective of Hermetic literature and the alchemical traditions that arose from it is a kind of cosmotheism, a religious sense that divine forces are at work in the physical world, the environment, and that human beings are connected with these forces in their environments. These texts portrayed the cosmos as an intelligent and communicative entity, constantly transmitting divine knowledge for anyone who cared to listen. Climate phenomena like frigid cold, failed crops, and darkened skies were symptoms of our interconnection with an environment that seemed to be communicating its own decline.

One of the most popular examples of what I call Hermetic Protestantism was a German devotional author named Johann Arndt. Arndt is largely forgotten today beyond historians of Protestantism, but in seventeenth-century Germany, a place ravaged by war and climate change, he was one of the most popular authors working at the time, bar none. Arndt’s book of Protestant devotion, True Christianity, was in constant print and circulation during the period, even outselling the Bible in some parts of Germany.

What made Arndt’s book so popular? Johann Arndt used (and even plagiarized) esoteric authors like the Swiss alchemist Paracelsus in order to give the Protestant people of northern Europe a religious perspective on their changing climate. As historians of modern Christianity have consistently noted, Lutheranism and an emphasis on scripture and word is entirely absent from Arndt’s work: in its place is a largely Hermetic cosmology of macrocosm and microcosm, derived from his own deep engagement with alchemy and the work of Paracelsus.

Arndt presents a Christian vision of a cosmos in which the suffering of human beings is mirrored by a wider suffering of nature:

The suffering of the macrocosm, that is, the great world, is subsequently fulfilled in the microcosm, that is, in humanity. What is to befall man, nature and the great world suffer first, for the suffering of all creatures, both good and evil, is directed towards man as a center where all lines of the circle converge. For what man owes, nature must suffer first.

In this deeply Paracelsian passage, Arndt envisions an almost ecological (if admittedly anthropocentric) Hermetic Christianity, in which the suffering of the human being is connected to and shared with a wider suffering of the cosmos.

Following the work of comprehensive histories like Geoffrey Parker’s 2013 book Global Crisis: War, Climate Change and Catastrophe in the Seventeenth Century, we are still at the beginning of understanding how exactly climate change has been a profound factor in even relatively recent human history. In the seventeenth century as surely as today, human beings felt the changes in their environments (even if they did not use contemporary frames of reference like “the environment” to describe them) and expressed their own understandings of themselves as connected with and dependent on the wider world around them. What is striking to me about these sources, which were intensely popular but remain largely understudied, is how they seem to reveal a common population that was remarkably intent on engaging, understanding, and drawing meaning from their changing world, while elite and university sources from the time seem largely oblivious to or unwilling to engage with the environmental signals around them. The more things change.

Reading sources from the seventeenth century will not provide us with strategies for mitigating global climate change—we already have those, and merely lack the political will to implement them. Rather, I interpret sources from this period to better understand the world we inhabit now, a world which has not stopped sending environmental signals to people who are willing to listen. If nothing else, the world of the seventeenth century shows that we are not alone as people living through climate change.

Featured image: Kometenbuch, 1587, State Library and Murhard Library of the City of Kassel. No known copyright restrictions.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

July 3, 2024

Words related to size, part two: tiny

Words related to size, part two: tiny

Now that we know how untrivial the origin of small, little ~ leetle, and wee is (see the post for June 20, 2024), we are fully prepared to examine the puzzling history of tiny. Little pitchers have long ears, and inconspicuous words may have a nearly impenetrable etymology. It is hard to believe how much trouble the adjective tiny has given researchers.

Little pitchers have long ears.

Little pitchers have long ears. Image by Alena Darmel via Pexels. Public domain.

This word surfaced in texts around the year 1600. Shakespeare (1564-1616) knew it (he always kept his ears open to the latest street talk), but his contemporary John Minsheu (1560-1627), who brought out the first etymological dictionary of English in 1627, may not have heard the new-fangled adjective. In any case, he did not include it in his work. All the later dictionaries featured tiny and even offered hypotheses of its origin in short (even tiny) statements, without citing any arguments. A serious discussion began with Walter W. Skeat, who kept returning to this word and in 1900 decided that he had at last solved the riddle. Nine years later, Ernest Weekley challenged his solution. Some sources side with him, but most say: “Origin unknown/uncertain.” An admission of ignorance is preferable to persistence in one’s folly. Still, one watches a long way from a wilted garden to a complete desert with sadness (sorry for speaking in metaphors).

These are the “unknowns.” Is tiny native or borrowed? Regardless of the answer, what is the root of tiny (-y looks like a suffix)? Tiny was not slang, but it emerged as a colloquialism. Though such etymological “lightweights” are always hard to trace to their sources, we would still like to find out under what circumstances the word was coined. Here is the summary in The Century Dictionary, published about a hundred and twenty years ago, long before the appearance of the fascicle with tiny in the OED (that is, not later than 1924; the date for the entire volume is 1926). Tiny, we read, competed with teeny, tinny, and tyny. The phrase little tine ~ tyne “a little bit” has been recorded, but the origin of this tyne is undetermined. This is all.

Our oldest dictionaries tried to guess which foreign word might be the source of tiny. Danish tynd “thin” has been cited with some regularity. As I keep repeating, when we pose borrowing from another language, we are expected to show the nature of the contact (who borrowed the word, where, and for what reason?). Indeed, why should English speakers have suddenly noticed a Danish adjective around 1600, garbled it, and turned it into a common English one? In 1924, W. de Vries, a Dutch philologist, pointed out that on hearing Dutch een litteltijn “a very little thing” (with ij pronounced like English ee), teen would emerge, appear in spelling as tine ~ tyny, and be pronounced accordingly. (In Dutch, littel is a variant of luttel.) Dutch is closer to English than Danish. Yet this is an unlikely scenario.

Here is Tiny Tim from Dickens’s A Christmas Carol in the early part of the story.

Here is Tiny Tim from Dickens’s A Christmas Carol in the early part of the story.Image by Jessie Willcox Smith via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

English etymons of tiny have also been suggested. The word teen “the tooth or spike of a fork or harrow” is close by, and so is the obsolete teen “affliction, vexation, malice, grief.” Neither looks like a promising source of tiny, especially because we are interested in tiny, rather than teeny. Teeny lad “peevish youngster” (Lancashire) may perhaps go back to teen “vexation,” but, to repeat, we need tiny. Several other conjectures share the same flaw: they tend to explain teeny and stop there. The ghost of Middle English Tineman “small official” was laid by the OED once and for all: this word did not exist. At present, tiny is cautiously believed to be of French origin, though most sources say: “Origin unknown.”

As noted, in 1900, Skeat published an article about the history of tiny. These were his main points. Tiny occasionally (seldom!) appeared in the form tine (so, for example, in Shakespeare). It emerged as a noun (!), preceded by little, as in a little tine boy, and this tine was dissyllabic (in Skeat’s spelling tinè), like tiny. However, the adjective tiny ~ tyne ~ tine occurred too and, when monosyllabic, rhymed with fine. Today, we say tiny, but tinee would have been the form to expect. A little tine meant “a little bit.” The use of bit (a bit bread, a bit paper, and so on) provides a good parallel. The OED cites similar instances of bit from Robert Burns and Walter Scott. The suffix –ee (as in tinee) occurs only in French words (committee, guarantee, and so forth). Consequently, tiny is also French. Skeat bent over backwards, trying to find a proper French etymon, and cited tinee “the content of a vessel called tine.”

The word he unearthed fits the context so badly that he needed a long paragraph to justify it. Earnest Weekley also believed that tiny was of Romance origin but derived it from French tantin, tantinet “ever so little.” He continued: “Transition from sense of small quantity to that of small size is like that of Sc[ottish] the bit laddie… But if the etymology I propose for wee is correct, tiny may rather be connected with teen.” As we remember, teen “affliction” figured in the search for the origin of tiny before Weekley, and in the previous post, I mentioned Weekley’s derivation of wee from woe. At the end of his career, Skeat hesitatingly accepted Weekley’s suggestion.

My problem is that I don’t understand why tiny, a colloquial word for “little,” should have been borrowed (or rather derived!) from French around the year 1600. Puny, which was recorded about fifty years later than tiny, is indeed a loan from French, but this word was a term meaning “a junior pupil.” Here, I would like to mention an unnoticed detail. In the first edition of his dictionary, Skeat wrote curtly: “Not imitative.” Consequently, such an idea had occurred to him! Indeed, tiny does not refer to sound, but Skeat may have remembered tintinnabulation “a ringing or tinkling sound” from Latin tintinnabulum “small tinkling bell” or English tingle and tinkle. The syllable tin is an ideal basis for all kinds of funny words. Such is the name of Tintin, the hero of the famous comics. Such is Japanese tintin “penis” (slang) and probably many more similar words in the languages of the world.

Teeny is believed to be an expressive variant of tiny. Four centuries ago, tiny was probably also expressive. I suspect that both teeny and the much earlier tiny belong with eena-meena and their likes—indeed, not necessarily imitative, but expressive words, used by or about children. People probably called little children tintin or something like it, and tine, with several variants, sprang up. Don’t we call little children tiny tots? By the way, tot, which sounds like quite a few words in the languages of the world, is, alas, “of unknown origin” too. Think of tit, tat, tut, teeter, totter…

A tot lot of undisputed origin.

A tot lot of undisputed origin.Image by Jlbirman1 via Wikimedia Commons. CC By-SA 3.0.

In one of my very old posts, I recalled a tale about a little girl who asked her mother how street cars go. The woman gave her a detailed explanation about electricity, motors, and the rest. The girl listened and then said: “No, this is not how they go.” “And how?” wondered the mother. The girl replied “Ding-dong.” I am afraid to return to the days of Plato’s etymology, but I suspect that tiny is one of such ding–dong words in English. This conjecture cannot be supported by any facts or arguments. Hence the result: “TINY: origin unknown.”

Featured image by Danielle Scott, via Flickr. CC BY-SA 2.0.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

June 30, 2024

Quiz: Pioneers from British history

Quiz: Pioneers from British history

We are celebrating the remarkable individuals who have shaped British history, from groundbreaking scientists to social reformers. Test your knowledge of historical figures and learn more about their astounding achievements with the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (ODNB).

Who was Ada Lovelace (1815-1852)?A: A romantic poet and satirist, whose poems include “She Walks in Beauty”.B: The creator of one of the earliest computer programmes.C: A popular portrait artist and one of two female founding members of the Royal Academy of Arts.What is Aneurin [Nye] Bevan (1897–1960) best known for?A: Founding the modern hospice.B: Establishing the National Health Service (NHS).C: Advocating for mental health care as General Secretary of the National Association for Mental Health.What is Sir Roger Bannister (1929–2018) best known for?A: Captaining England when they won the World Cup.B: Winning the Wimbledon singles championship five times.C: Becoming the first athlete to break the four-minute mile.Who was (Una) Winifred Atwell (1913–1983)?A: One of the longest-serving governors of the BBC.B: A community activist and the first Black headteacher in Wales.C: A musician who topped the British pop charts and sold out the Royal Albert Hall.Who was Dr Rosalind Franklin (1920–1958)?A: A crystallographer who contributed to the discovery of the structure of DNA.B: A crystallographer who discovered the structure of penicillin.C: A geneticist who pioneered the mapping of human chromosomes.What invention is Sir James Martin (1893–1981) best known for?A: The ejector seat.B: The portable fire extinguisher.C: Cat’s eyes.What is Elizabeth Blackwell (1821–1910) best known for?A: Leading the Edinburgh Seven, the first group of female students matriculated at a British university.B: Becoming the first recognized female doctor in Britain.C: Setting up a boarding house to treat soldiers during the Crimean War after the War Office refused her services.Featured image by Ray Harrington, via Unsplash, public domain.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

June 29, 2024

The medieval world [interactive map]

The medieval world [interactive map]

The study of the Middle Ages is expanding. With new locales and cross-cultural interconnections being explored, the study of the medieval world has never been more open. Against the backdrop of Martellus’ c.1490 world map, venture across the medieval world discovering Latvian Mead, trans-Mediterranean trade, and Ibn Battuta’s travels. Explore the Middle Ages like never before and sample medieval research from across our books, research encyclopedias, and open access journal articles.

Discover more research on the Middle Ages in our new collection page “The Medieval World” .

Featured image by Heinrich Hammer the German (“Henricus Martellus Germanus”) via Wikimedia Commons. CC0 1.0 Public Domain Dedication.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

June 26, 2024

Etymological small fry: some words for “size”

Etymological small fry: some words for “size”

Even the best-explained words denoting size are partly problematic, but at least their etymology does not always look like a series of insoluble riddles. For instance, small has cognates all over the Germanic–speaking world, and we know that the word was once mainly applied to small cattle. Such is the Icelandic noun (!) smali. Elsewhere, we find the familiar adjective meaning “thin,” “slender,” and “narrow” (such are, for example, German schmal “narrow,” as well as Danish and Swedish smal “narrow, thin”). Even the ties of small with a few non-Germanic forms are almost certain. In this blog, I have often referred to the enigmatic prefix s-, known as s-mobile, or movable s. Like the wind, this prefix “blowth where it listeth” and appears in front of many roots for no obvious reason. (A classic and trodden to death example is English steer “young ox” versus Latin taurus.) That is why when we come across Russian mal “small,” we have some reason to believe that it is related to English small. Classical Greek mēlon means “sheep,” just like Icelandic smali (small cattle!), and here too, we should probably yield to the temptation to connect them.

If the s-less forms are indeed related to small, then Latin malus (recognizable from English malaise, malcontent, malfeasance, and other borrowed Romance words of this type) and Greek mēleos “vain, useless, unhappy” (thus, not only mēlon “sheep”!) belong here too, but this Greek connection is less secure. Unfortunately, a list of related forms is not an etymology, because we want to know why a certain root means what it does. Yet we can seldom go beyond the same well-worn suggestions: sound imitation and sound symbolism. Perhaps such words as Russian molot’ “to grind” (stress again on the second syllable) and Latin molere (from whose root we have molar and less certainly emolument) are indeed sound-imitative (mol-mol-mol), but this is at best intelligent guessing. In any case, the development of meaning in small (as far as Germanic is concerned) was from some collective noun (a flock of small animals) to an abstract adjective. Adjectives often seem to be a result of afterthought.

The origin of all our smallness

The origin of all our smallnessImage by Krzysztof Kowalik via Unsplash. Public domain.

In dealing with other English words for “small,” we never have as much reliable information as in the history of small. For instance, the origin of little has given word historians endless trouble. The adjective is old, and its root must have been lut-, with either a short or a long vowel. Like small, little was a word known over a large territory. The Old English adjective had a short vowel, but in both Old Icelandic lítill and in Gothic leitils, the vowel was long. The difference between the vowels baffled historical linguists so much that the author of the recent German etymological dictionary declared (at lützel “little”): “Until this discrepancy has been clarified, the problem of origins will remain unsolved.”

It is always dangerous to swim against the current (see the image at the header!), but the problem may be less formidable than it seems. Words denoting size are often emotional. Over five hundred years ago, the English adjective leetle turned up in a book for the first time. Leetle is usually labeled as a vulgar pronunciation of little. But it is not really vulgar: it is emphatic or playful. Leetle means “very, very little.” Speech habits hardly change over time. Old Germanic, it seems, had several variants of the word that interests us here, one of them (childish or facetious) might sound approximately like leetle. Nursery words tend to penetrate the language of adults and lose their emotional coloring. A similar hypothesis concerning the long vowel in Icelandic and Gothic was offered exactly a hundred years ago and is always mentioned in detailed etymological dictionaries by way of afterthought and without discussion. It makes a lot of sense.

To show how wayward the path of words for “small” is, I may also cite English clean. Its exact Dutch and German cognates are kleen and klein “small, little” (not “free form dirt”!). The sense of the English adjective is original, as evidenced by its cognates in older German, in which the adjective meant “pure; delicate; neat; puny.” Such lines are easily crossed. Even in Modern English, the phrase delicate hands refers to hands beautifully shaped and small. Another example of a more or less the same type is English slight. Since slight means (among other things) “inconsiderable,” it does not come as a surprise that it may mean “not worthy of praise” (compare the verb: “to slight someone”), and lo and behold: German schlecht means “bad.”

In a different corner of the English vocabulary, we find the word wee. No Germanic or Indo-European ties here: just plain English. Not everybody may realize that some familiar poems from Mother Goose have well-known authors and were composed “the day before yesterday.” “Wee Willie Winkie” by William Miller (yes, William!) appeared in 1841. Wee is an old word. It emerged as a noun in the phrase a little wee “a little bit, a short time.”

This is William Miller, 1810-1872, the man who composed the poem “Wee Willie Winkie.”

This is William Miller, 1810-1872, the man who composed the poem “Wee Willie Winkie.”Image 1 by Kim Traynor via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 3.0. Image 2 by Cleo Sara, Library of Congress via Picryl. No known copyright restrictions.

This is what Walter W. Skeat wrote about wee: “I have little hesitation in assuming the Old Northern English we, or wey, or wei, ‘a way, space’, to be the same as Middle English wei ‘a way’, also a distance, Modern English way. Cf. Northern English way-bit, also wee-bit ‘a small space’.” Perhaps he was right, but even Skeat should not have said “I have little hesitation,” because hesitation is the corner stone of etymological research. (In the latest edition of his Concise Etymological Dictionary, he did not include weeny.)

Unlike Skeat, the editors of the OED connected wee with the word weigh. A little wee thing was supposed to mean “a thing that weighed little.” This derivation sounds more realistic than Skeat’s. Then there is weeny, used mainly in the phrase teeny-weeny. Apparently, weeny is wee with a suffix –ny, as in tiny ~ teeny. Weeny turned up as slang in the last quarter of the eighteenth century. This funny word looks like German wenig “little, a little,” but the two have nothing in common: the similarity is fortuitous and deceptive.

This is not the origin of the phrase small fry!

This is not the origin of the phrase small fry!Image by Dzenina Lukac via Pexels.

Now for desert, small fry. Fry in this idiom means “offspring; spawn of fishes; young fish”; hence “an insignificant person” and “all kinds of insignificant things.” French fries have nothing fishy about them. The word fry in small fry is of Germanic origin, even though the phrase turned up in thirteenth-century Anglo–Latin, that is, in the form of Latin used in medieval England.

Above, I have mentioned tiny, a late sixteenth-century word. Its etymology deserve a special page.

To be continued.

P.S. In my previous post, I discussed sw-words (swaying). Add swank and swanky to them.

Featured image by David Boca via Unsplash. Public domain.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

All about all

One of the quirkier features of the English syntax has to do with the simple word all. All is a quantity word, or quantifier in the terminology of grammarians and logicians. It indicates an entirety of something.

When I taught grammar, someone invariably brought up examples like this:

All of the books were damaged in the flood.

What is the subject of were damaged in the flood? Some students opted for the word books, since books were the things that got wet and moldy. Others said the subject was all, reasoning that of the books is a prepositional phrase, so books cannot be both the object of the preposition and the subject of the sentence.

That reasoning makes sense but it raises another question, when we look at examples like:

All of the money was burned in the fire.

If all is the subject, why does the verb seem to agree with the object of the preposition? We say The books were damaged and The money was burned. Perhaps all draws on the noun in the of-phrase for its grammatical number. By itself, all can be singular or plural, so this is not too outlandish.

All is lost.

All are accounted for.

Alongside examples with all followed by an of-phrase,there are examples like these, where there is no preposition following all:

All the books were damaged in the flood. All the money was burned in the fire.In these examples, the books and the money are the subjects and all is a modifier. Linguists consider this use of all a “pre-determiner quantifier” because it can occur right before the determiner the. Dictionaries will simply tell you that all can serve as a pronoun (all of the money) or as an adjective (all the money). The presence or absence of the preposition of makes the difference.

Here’s a further wrinkle. The modifier all can shift to the right, yielding sentences like:

The books were all damaged in the flood. The money was all burned in the fire.Linguists call this phenomenon “Quantifier Float”: the quantifier can float out of the noun phrase to an adverb position.

When pronouns are involved, the preposition of is required: we say All of them were waiting rather than the unEnglish All they were waiting. BUT if all floats to the right, the sentence with they sounds fine: They were all waiting.

Floating is even possible with direct object pronouns: We saw all of them and We saw them all.

Quantifier Floating is not just an English phenomenon. Similar shiftiness is documented in French, Arabic, Hebrew, Thai, Japanese, and German, to name just a few languages. And there are some other quantifiers in English that have similar floatability, like both and each.

Both of the copies were checked out from the library. The copies were both checked out from the library. Each of the books was returned to the library. The books were each returned to the library.So that’s all folks.

Featured image by Stephanie LeBlanc via Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

June 24, 2024

Speech, AI, and the future of neurology

Speech, AI, and the future of neurology

Imagine what your life would be like if you did not know where you are or who you are with, and a young man told you, “We’re home and I’m your son.” Now imagine how you would feel if your body became still when you want to walk or shaky when you try to keep still. Do it. Take a moment and think about it.

Those who do not need to imagine are the 55 million people living with Alzheimer’s and the 10 million living with Parkinson’s, respectively, as they experience similar challenges every day. While these figures raise concern, future projections are alarming: by 2050, the number of cases is expected to double in high-income countries and triple in low/middle-income countries. Things are particularly bleak in the latter, as they account for 60% of the cases but less than 25% of global investment in research, prevention, diagnosis, and treatment.

With growing patient-per-clinic ratios and soaring inequities across the globe, how will we detect these diseases early and massively enough for timely intervention? What solutions could balance the scales of brain health worldwide? An unsuspected answer involves combining natural speech and artificial intelligence. Yes, this sounds like another flight of imagination, but it all rests on solid science.

Note that these diseases are incurable. Rapid and mass detection is our best alternative; and this is precisely where the need for innovation emerges.Tracking diseases

Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s are neurodegenerative disorders, characterized by progressive atrophy of distinct brain regions. Alzheimer’s usually begins with neuron degeneration in the hippocampus and temporal lobe, affecting memory and several other abilities. In Parkinson’s, neuronal degradation begins in the basal ganglia, leading to motor and cognitive difficulties. Yet, this is just the tip of the iceberg. For patients, these diseases are disabling and often fatal. For families, they undermine emotional stability, financial solvency, and quality of life. For governments, they challenge health systems’ infrastructure and finances. Thus, these conditions project from the brain onto society, tracing a devastating trajectory.

That is why timely detection is crucial. Early diagnosis can mitigate the impact of symptoms, reduce their emotional burden on patients and caregivers, increase time to plan neuroprotective habits, and reduce costs by favoring routine over emergency care. Note that these diseases are incurable. Rapid and mass detection is our best alternative; and this is precisely where the need for innovation emerges.

Today, diagnosis rests on interviews with specialists, extensive paper-and-pencil tests, and, when conditions allow, brain MRI studies and biomarker assessments. These procedures are invaluable, but imperfect. Many countries lack enough qualified personnel and appropriate technology (and when these resources exist, their costs can be prohibitive). Furthermore, outcomes depend on the judgments of examiners, who vary in training and experience. Moreover, assessments are usually stressful and appointments take weeks or months. Worse yet, these limitations are exacerbated as patient numbers increase and socioeconomic disparities between countries deepen. An urgent need thus arises for new affordable, user-friendly, scalable, and immediate approaches.

Red flags in speechThis is where digital speech biomarkers come into play. Suppose that Tom, who is pushing 70, has been showing signs of cognitive decline and you suspect he might be suffering from Alzheimer’s. What if you asked him to recount a memory and an app detected traces of the disease in his speech? This non-invasive, low-cost approach offers real-time results without the need to visit a clinic, sparking great enthusiasm. Yet, how exactly does it work?

The key is that when we speak, we engage multiple brain regions that are affected by these diseases. Some, such as the hippocampus and the temporal lobe, are involved in accessing words as discourse unfolds; others, like the basal ganglia, coordinate the physical movements during speech production. So, if such regions were atrophied, one would expect alterations in the types of words used, their articulation, or other relevant aspects. By testing specific linguistic dimensions, we can uncover the integrity or dysfunction of those brain areas.

The first step is to record the natural speech of individuals with and without a given disease (the more, the better). Subsequently, complex algorithms quantify multiple aspects of the recording (say, speech rhythm) and its transcription (say, word properties). These metrics are used to train computational models that learn the typical speech characteristics of diagnosed individuals and healthy ones. Once the model is trained, it is presented with acoustic and linguistic measures from Tom, and, essentially, queried with this question: “Model, based on what you’ve learned, does Tom have the disease or not?”

In a recent study, our team identified Alzheimer’s disease with nearly 90% success via word property analysis. The model learned that patients, compared to their healthy peers, use words with higher frequency (‘doctor’ rather than ‘physician’), lower specificity (‘dog’ instead of ‘poodle’), and more common sound sequences (like ‘bat’, which resembles ‘cat’, ‘fat’, ‘mat’, ‘rat’, ‘bet’, ‘bit’, ‘bought’, ‘boot’, ‘bad’, ‘bag’, and ‘ban’; as opposed to ‘giraffe’, whose sound sequence is quite unique). Indeed, these lexical properties predicted the patients’ level of cognitive decline and brain atrophy. The reason is quite simple: word selection is a central function of semantic memory, which becomes impaired since the onset of temporo-hippocampal atrophy in Alzheimer’s. When navigating semantic memory, people with the disease prioritize the most accessible parts of their vocabulary, consisting of frequent, unspecific, and common-sounds words. And the more severe their disorder is, the simpler the words they favor.

In another study, we detected Parkinson’s disease with over 90% accuracy by measuring motor aspects of speech. We found that patients, compared to healthy individuals, leave longer pauses between words and produce less recognizable sounds. These patterns even differentiated between disease variants. Once again, the finding is clear. Speech production requires coordinating movements of the tongue, lips, and vocal cords, among other organs. Since basal ganglia atrophy affects motor skills, these actions in people with Parkinson’s prove slow, shaky, and imprecise. The audio signal carries traces of these alterations.

The breakthroughs do not stop there. These methods can anticipate who will develop specific conditions in the future. Some studies also suggest that they outperform standard tests in estimating disease severity and discriminating between syndromes. The approach has been validated with data acquired in hospitals and over the phone, incorporated in clinical trials, and harnessed by user-friendly apps. These are critical milestones towards rethinking clinical assessments.

The breakthroughs do not stop there. These methods can anticipate who will develop specific conditions in the future.A story in the making

For all its promise, this story is only beginning. The approach requires more validation, especially in large groups of patients. New studies should focus on vulnerable populations to balance the abundant data coming from high-income countries. More generally, a digital medical culture must be cultivated for clinicians to incorporate computational tools. Of course, these milestones demand concerted efforts of scientists, medical professionals, patients, family members, companies, and policymakers. None of this is easy or immediate. The path from science to clinical practice and public policy is long, crooked, and uphill.

Fortunately, this is not an isolated endeavor. Various teams are working on other digital tools for disease detection, including eye-tracking devices, motion sensors, and gamified cognitive tests. Speech analysis is part of a vast movement pushing for clinical equity through technological innovations.

To conclude, imagine that we can detect these diseases before Tom shows symptoms of decline. Imagine doing so by reducing the social gaps among world nations. And imagine a future where all this needs no longer be imagined. If such a day ever arrives, it will be through disruptions like this.

Featured image by TungArt7 via Pixabay.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

June 21, 2024

Better together: coupling up to watch TV and talk synchronizes brain waves

Better together: coupling up to watch TV and talk synchronizes brain waves

Scientists are a step closer to finding out just why watching TV together and talking is such a popular pastime. Watching the same movie stimulates similar neural activity across brains: a phenomenon referred to as inter-subject correlation. Subjects sitting in the same room and talking over the content have been shown to increase various other measures of brain synchrony.

Now it turns out that we don’t even need to be discussing what’s on the screen to get more in tune with each other during the next show.

Lead author Dr. Sara De Felice, Professor Antonia Hamilton, and other colleagues at University College London used functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) to measure brain activity in 27 pairs of adults as they each watched two different episodes of the short BBC children’s cartoon Dipdap. In between the episodes, the subjects talked over trivial facts unrelated to the show, such as exotic animals and musical instruments. The researchers then compared the data on brain activity recorded during each episode to see if the non-relevant chatter had affected mental synchrony.

Their results, published in Oxford Open Neuroscience, showed increased brain synchrony over the right dorso-lateral pre-frontal cortex (DLPFC) and right superior parietal lobe (SPL) in familiar pairs (housemates, friends, or partners) watching the cartoon together compared to pseudo pairs who had not met, and who watched the short film alone. These results are in line with previous studies into these brain regions which indicate that the DLPFC is associated with functions like working memory, abstract reasoning, and cognitive flexibility while the SPL receives significant visual input, and is also associated with reasoning and memory, as well as attention.

The study also found that co-watching after a conversation was associated with greater brain synchrony over the right temporoparietal junction (TPJ)–an area of the brain famous for allowing other perspectives (theory of mind)–compared to co-watching before a conversation. This effect was significantly higher in familiar pairs engaging in conversation with each other than in pseudo pairs who talked to someone else.

“Two things are surprising and novel here,” says Dr. De Felice (now at the University of Cambridge). “First, having a chat resulted in brains also synchronising afterwards. Second, the chat didn’t have to be related to the movie to see this effect.”

Brain gamesThe scientists selected fNIRS for this research as it uses light to map blood flow in response to neural activity at sites across the head, allowing the study of natural face-to-face interactions because subjects aren’t physically confined in a noisy fMRI machine.

“fNIRS is non-invasive and robust to movement, allowing the measurement of brain activity from people as they act and interact normally,” says Dr. De Felice. On the downside, its lag time of around five seconds makes it much less spatially and temporally accurate than other techniques.

The researchers found no significant differences in the other five brain regions selected for measurement.

“Brain synchrony was observed in three areas (the DLPFC, SPL, and TPJ) which play a key role in our ability to interact with others, understand intentions and emotions, and interpret other people’s perspectives,” explains Dr. De Felice. “It makes sense that we observe synchrony over these areas during co-watching of the BBC Dipdap cartoon, where the watcher is encouraged to follow and predict what the puppet will face next.”

She suggests the findings, along with those from numerous other studies, could indicate that brain synchrony extends to and from further behaviours: “This might explain why people who spend considerable time together often find themselves in greater agreement with each other than with those they’ve never met. Through such interactions, individuals can develop a shared reality, both physically and mentally.”

The next challenge is to better explore the causal relationship between synchrony and social interaction, examining if altering this synchrony using brain stimulation would alter the parameters of interaction, she says.

Featured image by Sarandy Westfall via Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

The enchanted renegades: female mediums’ subversive wisdom

The enchanted renegades: female mediums’ subversive wisdom

Amidst the tapestry of history, there exist threads often overlooked, woven by the hands of remarkable women who defied the constraints of their time. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, amidst the burgeoning intellectual and cultural movements of Europe, the fascinating phenomenon of female mediumship emerged as one such thread in the history of Western psychology.

When considering the pioneering intellectual figures of the era, prevailing narratives often cast their achievements as monuments of male genius. The likes of Charcot, Freud, and Jung have long persisted as emblematic icons of modern thought, perpetuating a mythos of masculine dominance in the annals of history.

But peer deeper into the cultural undercurrents, and you’ll find eccentric, queer feminine forces that disrupted masculine regimes of knowledge. In dimly lit parlors of 19th-century Europe, the spiritualist séance cultivated a uniquely democratic forum where traditional gender hierarchies dissolved under trance’s transfigurative epistemology. Common housewives and daughters, through spirit possession, could channel poetic tongues, cosmic landscapes, and incarnated personae that far eclipsed their modest social status.

Hélène Smith was an unremarkable Genevan clerk who, through spiritualist séances, produced outpourings of poetic tongues, alien landscapes, and revivals of historical figures that enchanted and bewildered the rationalist thinkers observing her (interpreters of her séances have included the “fathers” of French psychoanalysis, linguistics, and surrealism: Jacques Lacan, Ferdinand de Saussure, and André Breton). Smith’s embodied possessions erupted with what could be seen as a distinctly queered grandiosity–not only upending norms around feminine expression, but channeling esoteric mysteries that transcended the grasp of her renowned observers. Her glossolalia (she created a variety of extra-planetary languages), past-life narratives (she notably incarnated Marie-Antoinette), and visionary artworks (paintings of her supernatural visions) asserted a chthonic, feminine gnosis challenging modern understandings of the psyche.

Spiritualism had emerged in the 1840s as a ceremonial practice for communing with the dead. In many ways, spiritualist exploration of the séance ritual represented a subversive evolution of Western esotericism’s enchanted worldviews. While eccentric, radical philosophies of nature’s divine embodiment had circulated through esoteric undercurrents for centuries, the 19th century saw mediums democratizing access to such landscapes. Common individuals, and most particularly women, were believed among adherents to host manifestations of the supernatural through their own consecrated bodies and psyches.

The Fox sisters are known today as having originated the Spiritualist movement in Hydesville, New York, in 1848. The movement spread rapidly: as the psychologist Carl Gustav Jung recounted in a 1905 lecture, “in Europe, spiritualism took the form chiefly of an epidemic of table-turning. There was hardly an evening party or dance where the guests did not steal away at a late hour to question the table.”

The Fox sisters are known today as having originated the Spiritualist movement in Hydesville, New York, in 1848. The movement spread rapidly: as the psychologist Carl Gustav Jung recounted in a 1905 lecture, “in Europe, spiritualism took the form chiefly of an epidemic of table-turning. There was hardly an evening party or dance where the guests did not steal away at a late hour to question the table.”Mrs. Fish and the Misses Fox. Library of Congress. New York, 1852. Public Domain.

Spiritualism’s rise coincided with scientific disenchantment narratives claiming to secularize occult forces into clinical phenomena like hysteria. Yet paradoxically, medical theorists like Jean-Martin Charcot reframed the feminine body itself as a site of profound mystery—a threshold where cosmic wonders could inscribe themselves through stigmata, seizures, and automatic scripts. Séances erupted this sanctified feminine materiality into public discourse. Women mediums’ incomprehensible corporealized phenomena unsettled masculine knowledge constructs. The feminine body’s passions and flows became mouthpieces for ancient, prophetic teachings that masculine authorities anxiously reframed yet could not fully grasp.

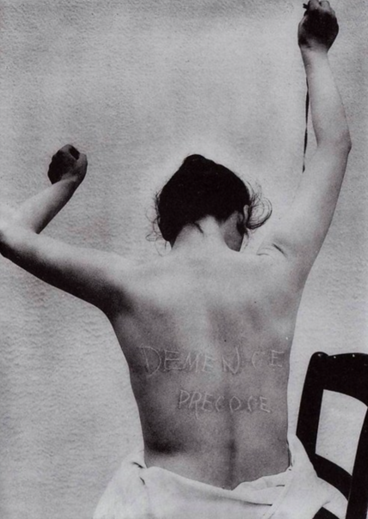

At Charcot’s institution, the hysterical female body became a paradoxical site for the material relocation of the sacred and magical. Associating hysteria and a dermatological condition called dermographism, medical authorities conducted various experiments during which they inscribed signs of the devil, or the name Satan, on the hysteric’s body to indicate that previous sightings of this mark had been ill-understood manifestations of hysteria.

At Charcot’s institution, the hysterical female body became a paradoxical site for the material relocation of the sacred and magical. Associating hysteria and a dermatological condition called dermographism, medical authorities conducted various experiments during which they inscribed signs of the devil, or the name Satan, on the hysteric’s body to indicate that previous sightings of this mark had been ill-understood manifestations of hysteria.

L. Trepsat. Dermographisme: démence précoce catatonique. Nouvelle iconographie de la Salpêtrière. Paris, 1904, p. 196. Public Domain.

In this light, spiritualist mediumship unfolded privileged modes of knowledge. Mediums like Smith produced otherworldly speeches and visions that scientific observers labored to secularize and inadvertently drew nourishing power from.

Hélène Smith’s Uranian script, deciphered by Théodore Flournoy in his work.

Hélène Smith’s Uranian script, deciphered by Théodore Flournoy in his work.Nouvelles observations sur un cas de somnambulisme, 1900, p. 185. Public Domain.

Hélène Smith was not an isolated phenomenon, but emblematic of women medium’s intrusions into masculine knowledge structures at a time when the boundaries between ESP (extra-sensory perception) phenomena and psychology emerged. Through their consecrated embodiments, spiritualists like her did not merely dissolve identities into passivity, but unleashed agential mysteries into philosophies that pre-encoded the sanctified feminine’s marginalization. Their refusal to cohere sparked foundational questionings at the origins of modern understandings of the mind. The enchanted renegades transmuted subversive wisdom through acts of self-dissolution—twinning pathways of submission and subversion into an undecidable, uncanny, and impossibly alive feminine force.

Featured image credit: “Un salon the Paris au mois de mai 1853.” L’Illustration, Paris, May 1853. Public Domain.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers