Oxford University Press's Blog, page 25

June 6, 2024

How to turn your PhD thesis into a book

How to turn your PhD thesis into a book

As an OUP editor who has also completed a PhD, one of the most common questions I am asked is how to turn a thesis into a book. My only-slightly-flippant answer is don’t.

Rather than a revision of their PhD, I would encourage first-book authors to treat their fledgling monograph as a brand-new project.

In a 2015 interview for Vogue, Ursula K. Le Guin spoke about revising Steering the Craft, her classic handbook for aspiring fiction writers, for the twenty-first century. ‘It’s substantially the same book,’ she says, ‘but almost every sentence is rewritten.’ This oxymoron draws attention to the slippery distinction between the work of revising and the work of rewriting. Far from being a distinct undertaking with a separate purpose, revising often shades off into rewriting by an almost imperceptible degree.

For former doctoral students, this is no bad thing. A PhD thesis and an academic monograph have entirely different purposes—trying to turn the former into the latter via a process of revision can feel like trying to fit a square peg into a round hole.

At the most basic level, a thesis is a document written to pass an exam and to prove the writer’s skill as a researcher. In keeping with this purpose, it is written for a readership of two or—if we’re being generous—three people: your pair of examiners and your primary supervisor. More people will likely read parts of your thesis, although they are not the target readership. A monograph, on the other hand, is written to communicate important and useful research to the widest possible specialist readership. Each of the two documents’ purposes is entirely different, and everything about their construction must feed into that purpose, or they are not doing their job very well.

Before you beginIt’s worth pausing to think whether your thesis needs to become a monograph to advance your career. In certain disciplines, a couple of peer-reviewed research articles in reputable journals is just as, if not more, advantageous than a monograph with an equally reputable publisher.

There’s also the effort-to-reward ratio to consider; turning two thesis chapters into research articles may be less time consuming than turning your entire thesis into a monograph. Besides, having some disciplinary journal publications to your name is going to make a publisher far more interested in your first book, which can now be based on new research unrelated to your thesis. I am reminded of Pat Thomson’s sage advice that ‘all PhDs can generate some refereed journal articles. But not all PhDs have enough in them to become a book.’

Turning your PhD thesis into a monograph should not be seen as the default course of action, so carefully consider the alternatives before embarking upon this route. But if you still want to, here are a few things you should consider:

Authorial voiceWith your PhD in the bag, you have proven your skill as an academic researcher. Congratulations!

Your authorial voice should now feature more prominently in your writing and your own original interpretation should be prioritised over the views of your predecessors. This approach is very different to writing a thesis, where your interpretation must be couched in quotations from secondary sources. You no longer need to provide an audit trail to such a great extent, and monographs feature far fewer secondary quotations—especially long block quotations—than are commonly found in theses. Similarly, the number of secondary citations should be significantly reduced to only cover essential reference points. The spotlight should be firmly on your original ideas and your discussion of primary sources, with far fewer words devoted to quoting and evaluating the contributions of others.

Literature reviewTo put it simply, a monograph shouldn’t have one. Building on the previous point about authorial voice, the literature review is the prime example of providing an audit trail that simply isn’t expected in a monograph. Remove it! Then, in its place, summarise in one or two pages the most important through-lines found in that literature that are of direct relevance to your arguments. Your readers will assume you’ve done your homework (that was the PhD thesis) and you only need to introduce them to the secondary sources that are essential to following the argument of your monograph. For example, if your work is interdisciplinary and you’re pitching the book to a publisher’s disciplinary list, you might need to summarise the key findings of a particular school of thought from outside the list’s ‘home’ discipline.

MarketUnlike a PhD thesis, a monograph needs to sell copies. Even not-for-profit university presses are required to break even, and a publisher won’t take a chance on a monograph unless they consider it a safe investment. It is down to you to convince them that there is a market for your work and that you write in a way that effectively captures that readership. You must be certain of your book’s selling points and ensure they are effectively communicated in your book proposal and woven into every section of your draft manuscript or writing sample.

One example: publishers are increasingly asked to think about how ‘adoptable’ someone’s book project is, meaning: can we picture it being assigned as required reading in undergraduate or postgraduate courses? For this to be the case, individual chapters should be concise and able to be assigned as standalone reading. Jargon should be kept to a minimum. Anything even slightly tangential should be cut.

StylePat Thomson says that converting your PhD thesis into a monograph is ‘a time to hone your writing craft’. What she means by this, I think, is that you have the opportunity and responsibility to learn how to become a better communicator. Your PhD examiners are obliged to read your thesis no matter how engaging they find it, whereas if the readers of your monograph find it unengaging, they will simply stop reading. Academic writing can be so much more than dry, expository prose, and this is a time to stretch your creative writing muscles in a way you weren’t able to do while writing your thesis. Le Guin’s Steering the Craft provides some narrative techniques and writing exercises to help you do this.

Where to begin?My advice would be to begin at the end. The conclusion of your PhD thesis probably contains your most valuable insights, most useful innovations, and most compelling answers to the all-important questions of ‘so what?’ and ‘why should anyone care?’. These diamonds in the rough can form the building blocks of a monograph that should be thought of not as a revision of your thesis, but as a brand-new project that builds upon your previous research. This new project can draw from some of the most exciting parts of your thesis, though it should be more than just repackaged doctoral research. And it will be far more attractive to a publisher, not to mention enjoyable to write.

Featured image by Element5 Digital via Unsplash.

June 5, 2024

Some gleanings and the shortest history of bummers

Some gleanings and the shortest history of bummers

Before coming to the point, I wish to thank our readers for commenting on the previous post, which was devoted to the history and origin of lady. Yet one comment hearkens back to my ideas on the etymology of quiz. I think such a “funny” monosyllable could be coined more than once. Some language historians choose to refer to so-called multiple origins. Yet even if some word had, like the Scandinavian god Heimdall(r), nine mothers, only one must have been the real source of the form that continued into the present. The problem is to find the successful progenitor.

Another reader noted that essays, like the one devoted to the word lady, are more attractive than such as deal with an obscure piece of American slang (the reference must have been to fink “police informer; strikebreaker”). Tastes differ, but the origin of slang interest many people. Let us also remember that this weekly blog is supposed to deal with etymology. To be sure, since March 1, 2006 (the day on which the blog was launched), I have occasionally discussed usage and other topics not related directly with word origins, but those were chance “deviations.” Finally, the development of meaning is easy to follow by consulting the OED, and I always try to avoid recycling the information available elsewhere. As far as lady is concerned, I was in a good position, because I could use a long article about that word’s history. At the moment, I have a candidate for another similar post and will probably soon avail myself of it. Also, today’s post is both about origins and history.

Finally, a note on the ladybird. I too grew up using this word but changed it to ladybug in America, just as I substituted bug for beetle and almost stopped using the present perfect.

And now some observations on bummers, inspired by an old exchange in Notes in Queries. If you’re so inclined, I’ve provided a soundtrack for this particular post.

Many years ago, I wrote a series of posts on the names of drinking vessels. One of them dealt with bumper. Words like bump, thump, bomb, and boom are rater obviously sound-imitative, but this does not mean that they have no history worthy of investigation. Bumper was a typical example. Do bum and bummer belong with it? As early as the eighteen-sixties, bummer was traced to German bummeln “to stroll,” its Dutch cognate, or to several German verbs referring to a booming noise. Californian and Nevada miners connected bummers and cockchafers. The author of the note on this subject added: “I have myself heard a lady [!] on a Virginia plantation speak of ‘bummers booming around’. The word in its insect meaning is evidently formed from sound.”

A classic bummer, but not the one we need.

A classic bummer, but not the one we need.Image by Patrick Rock via Wikimedia Commons. CC3.0.

A correspondent from Paisley (Renfrewshire, Scotland) wrote: “Bummer is a slang word in this district to signify a person who is given to talking in a boastful manner; also to one who utters much idle and foolish talk. It is only used among a certain class of people. Those who are choice in their language [sic] never use it. Bumming is equivalent to ‘humming’, of bees. Bees are sometimes called here bumbees. Hence a bummer may be a person who bums like a bee, that is, utters a deal of empty sound to no purpose.”

The never-to-be-forgotten Mr. Bumble did get his comeuppance. Say no to bumbledom!

The never-to-be-forgotten Mr. Bumble did get his comeuppance. Say no to bumbledom!Image by Kyd (Joseph Clayton Clarke), Wikimedia Commons via Picryl. Public Domain.

The knowledgeable Edward Bradley (not to be confused with Henry Bradley of the OED), who wrote under the pen name Cuthbert Bede, commented on the word so: “In an almost obsolete ceremony of beating the bounds, a person is selected to be bumped at certain places at a certain part; and I have heard the above title [bummer] assigned to him, for very obvious reasons.” He added that in some parts of East Anglia bitterns were called bummers, a synonym for boomers, and concluded his note so: “The word ‘bumble-bee’ is very common; and I have always fancied that from this ‘yellow-liveried’ gentleman, with his obesity and fussiness, Mr. Dickens took the name of his never-to-be-forgotten Bumble.” In 1868, Dickens was still alive; hence Mr. Dickens. Cuthbert Bede was probably right, though he did not remember that in Chaucer’s Wife of Bath, there is a line: “And as a bittern bumbleth in the myre.” Incidentally, it will be observed that we are a century away from the Americanism bummer “a severe disappointment.” Its etymology is not as obvious as it may seem.

Then there once was the word bummaree. The original OED referred bummaree to bottomry, a legal term in mortgaging ships: the money under this contract is borrowed upon the bottom or keel of the ship (that is, the ship itself!). Apparently, in the second half of the seventeenth century, bum “bottom” was not vulgar. Later, it became a word “not in polite use.” Bum “buttocks” throws an additional light on bummer. Whatever the origin of bummer may be, the word could not avoid associations with bum, polite or impolite. That association was not lost on the speakers who contributed their opinions to Notes and Queries in the second half of the nineteenth century: “This [bummer] probably is an adaptation of a very coarse common English word, and signifies a squatter; one who sits in your cabin till everybody is tired of him, and at last are glad to be rid of him by giving him something” (1888). Or “a bummer may be a person who bums like a bee, that is, utters a deal of empty sound to no purpose” (1868), an already familiar derivation.

Then there is bummaree. I’ll reproduce part of an unsigned letter to Notes and Queries (November 3, 1888, p. 5; it was reprinted elsewhere in 1890 and 1891). Among other things, it contains, though, unfortunately, without an exact reference, an antedating to the citations in OED: “This [bummer] is usually considered to be an Americanism. [?]. But, like many other Americanisms, it is simply a legitimate descendant of an Old English word, bummaree, which may be found in the ‘English Market By-Laws’ of over two hundred years ago. In the London Publick Intelligencer for the year 1660 it appears in several advertisements. Bummaree meant a man who retails fish by peddling outside of the regular market. These persons were looked down upon and regarded as cheats by the established dealers, hence the name became one of contempt for a dishonest person of irregular habits. The word first appeared in the United States during the ‘50’s in California, and traveled eastward until during the civil war [sic] it came into general use.” If I understand the idea of this note correctly, bum is said to be the stub of bummaree.

[image error]No bummarees allowed on these premises.Image by Ben Stephenson via Flickr. CC2.0.

The spelling traveled in the note above (with one l) betrays an American. Thus, we are offered a third etymology of bum (a stub of bummaree). This etymology is unlikely, because bummaree could never be a widely-known word. Still, we wonder: what could be the origin of the exotic-sounding bummaree? If it is bum-a-ree (compare cockle-a-doo or jack-a-dandy), what is ree? The OED lists several obscure nouns spelled ree, none of which fits this context. An old hypothesis derived bummaree from French bonne marée “good fresh sea fish” (folk etymology? Or did those cheats pretend to be French?). In any case, the paths of bum and bummaree hardly ever crossed.

James A. H. Murray said that the use of the word boom has not been regulated by any distinct etymological feeling (what a wonderful formulation!). Isn’t this also true of bum? And couldn’t bum, like, presumably, quiz, be born of more mothers than one, with only one being considered legitimate?

Featured image by George Eastman Museum via Flickr. No known copyright restrictions.

Dictators: why heroes slide into villainy

Dictators: why heroes slide into villainy

What do Vladimir Putin, Fidel Castro, and Kim Il-sung have in common? All took power promising change for the better: a fairer distribution of wealth, an end to internal corruption, limited foreign influence, and future peace and prosperity. To an extent, they all achieved this, but then things began to go wrong. Corruption raged in Putin’s Russia; millions fled grinding poverty and political persecution in Castro’s Cuba; and Kim’s Korea launched a disastrous war that, to this day, makes reunification with the now-wealthy South a distant dream.

Rather than admitting failure and handing over power to the next generation, each autocrat hung on, long outliving their welcome. And we can add Joseph Stalin, Benito Mussolini, Hugo Chavez, Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, Muammar Gaddafi, and Daniel Ortega to the list.

So, why does this happen so often?

From triumph to tyrantA new model, developed by Professor Kaushik Basu from Cornell University, and published in Oxford Open Economics, simulates the decisions national leaders face. It reveals positive feedback conditions that lead to escalating acts that serve the autocrat’s self-interest, and preservation of power, rather than the best interests of the country.

“My paper was provoked by a personal encounter with Daniel Ortega of Nicaragua,” Professor Basu, former chief economist of the World Bank, recalls. “When I met him in September 2013 he still had the aura of a progressive leader, but subsequently morphed into a kind of tyrant that I would not have predicted. I wrote up the algebra to explain this transformation, and realized I had hit upon an argument that explains the behaviour of a large number of authoritarian leaders around the world.”

It can take many years of struggle for a dictator to reach office and achieve their political ambitions. Reluctance to risk this work in progress with a popular vote after a mere four- or five-year term leads to actions such as intimidating, imprisoning, or assassinating political rivals; silencing the press, financial corruption, and tax evasion; influencing or corrupting the judiciary. Such tactics work—in the short term, at least —but opponents can’t be silenced forever: truth finds a way, often supported by domestic or foreign antagonists.

As these controlling behaviours escalate, it becomes clear that relinquishing power would lead to legal persecution or imprisonment: just ask Chilean autocrat General Pinochet, arrested after leaving office; or Uganda’s Idi Amin, forced into exile in Saudi Arabia.

Basu’s algebraic model shows that, after a threshold of bad behaviour is passed, no amount of do-gooding can undo the damage: the only choice left a dictator is to tighten his grip on power especially if, beyond national justice, lie international courts and tribunals. For example, Sudan’s former leader Omar al-Bashir has been in hiding since 2009, a fugitive of the International Criminal Court.

Democratic policy mattersThe model explains why two-term limits have evolved as a popular way to curb such damage as they provide a limited time for unsavoury actions to accumulate, a single opportunity for re-election, and better options for leaving office peaceably. So, could this common system be more widely employed to prevent dictatorships?

“A globally-enforced term limit is an important step, but may not be enough,” says Basu, who half-jokingly suggests that creating an easy exit for dictators, such as offering them a castle on a Pacific island, could also be effective.

Joking aside, the paper has important implications for current US politics. Former US president Donald Trump faces 91 felony counts across four states. Is the barrage of legal indictments boxing him into the corner where he has no option but to regain office, and then corrupt power to save himself, just as the model predicts?

At a time where authoritarian regimes are on the rise—the 2024 Economist Intelligence Unit report shows that 39.4% of the world’s population is under authoritarian rule, an increase from 36.9% in 2022—the need is greater than ever to promote policies that could halt the slide.

Feature image by Peterzikas, via Pixabay. Public domain.

June 3, 2024

A listener’s guide to Sand Rush [playlist]

A listener’s guide to Sand Rush [playlist]

Writing Sand Rush forced me to watch some of the worst teen movies ever produced by Hollywood— I’m never getting that one hour of my life spent watching The Ghost in the Invisible Bikini (1966) back—but the music associated with California beaches is top notch. Almost all of the songs on the Sand Rush playlist are from a very short period in time, roughly between 1961 and 1965 (not withstanding some obvious throwback songs from the 80’s, 90’s, and beyond), when the Southern California beach culture was on display everywhere, from music album covers to movies and magazine advertisements.

This obsession was part of the enormous cultural influence California exerted nationally during the postwar period. With its burgeoning suburbs, automobile-centered lifestyle, bountiful jobs, and youthful population, the Golden State came to embody the boundless opportunities that peace and economic growth had to offer. Furthered by the surfing craze and the popularity of beach “teenpics,” Southern California beach culture emerged as the perfect metaphor for the good life. The music of that era reflected the carefree nature of the LA beach scene.

By the 1970s, however, the tide had turned. Americans were singing a different tune as they became aware of the environmental cost of “progress.” Two years after the 1969 Santa Barbara oil spill, the Beach Boys released their uncharacteristically melancholic “Don’t Go Near the Water” (1971). This wasn’t their last foray into ecological music; in 1995, they appeared on the TV-show Baywatch for a good cause—fundraising for the Surfrider Foundation—and committed one of their worst tunes to date, “Summer in Paradise” (“Give me sunshine water and an ozone layer!” they pleaded). Nonetheless, apart from the latter example, most of the songs listed here make for some enjoyable listening whether you’re planning a road trip along the Pacific or simply want a taste of summer. I’ve included obvious choices, a few personal favorites, and some below-the-radar songs that combine historical value and musical appeal.

Listen to the full playlist and read on to learn about the songs that were a backdrop to the transformation of the California coastline.

1. Original music for Muscle Beach by Joseph Strick (1948); words and lyrics by Edwin Rolfe, composed and sung by Earl RobinsonThis is one song that you are unlikely to see mentioned on most “California beaches” playlists. Muscle Beach is a wonderfully evocative short documentary by experimental filmmaker Joseph Strick, filmed, you guessed it, at Muscle Beach. Except this is the old site in Santa Monica, not the Venice one you may have visited along the boardwalk. From the 1930s onwards, acrobats and gymnasts started working out at this public playground, eventually improving it by building a wooden platform and other gym apparatuses. In the 1950s, Muscle Beach was the ideal place to observe beautiful, athletic bodies in motion. However, it wasn’t to the taste of everyone in Santa Monica and the conservative city council eventually got rid of it in 1958. The song that accompanies the film is typical of the folk music genre Earl Robinson was famous for and the lyrics, by poet Edwin Rolfe, poke gentle fun at the pursuit of the body beautiful when “laying off the custard cream” is so hard. His message (get out to Muscle Beach!) is a timeless reminder that the beach is a good place to get back into shape!

2. James Darren “Gidget” (1959)The release of Gidget in 1959 is often praised (or blamed depending on who you’re speaking to) for starting the beach craze and turning Malibu into an overcrowded area full of “kooks.” Based on the young adult novel of the same name written by Austrian-born Frederick Kohner, Gidget was certainly a box-office hit and the precursor to the beach movie genre. James Darren’s “Gidget” may not be so much about the surfing culture (the lyrics focus on the “tomboy” charm of the main character), but it captures something of its carefree spirit. Darren’s vocals and upbeat rhythm evoke the sun-kissed beaches of California, where the fictional Gidget (short for “girl midget”) learns to ride the waves and finds herself (and a boyfriend). With its catchy melody and playful lyrics, the song became a symbol of youthful exuberance and summertime adventures.

3. Dick Dale “Let’s Go Trippin’” (1961)Dick Dale’s “Let’s Go Trippin’” is a groundbreaking surf rock anthem that ignited a cultural revolution. Considered by many to be the first surf song, “Let’s Go Trippin’” encapsulates the thrill of riding the waves and the freedom of the open ocean. Dale’s innovative use of reverb and tremolo amplification creates a sonic landscape that transports audiences to sun-drenched beaches and blissful summer days. This legendary track not only launched Dale’s career as the “King of Surf Guitar” but also paved the way for the surf rock genre’s enduring legacy. It should also be noted that while many members of surfing bands had never set foot on a board (most of the Beach Boys, in fact), Dick Dale himself was a bona fide surfer.

4. Annette Funicello & Frankie Avalon “Beach Party” (1963)Released in 1963, “Beach Party” by Annette Funicello and Frankie Avalon epitomizes the core essence of 1960s surf culture, and is a renowned anthem of the beach movie genre. Funicello and Avalon, beloved icons of the era, didn’t exactly look like California teens. They both had dark brown hair, Funicello had pasty white skin and she couldn’t (or wouldn’t, it was never clear) show her belly button on screen, allegedly out of respect for Walt Disney who had launched her career as a Musketeer. Yet their undeniable chemistry on screen and the gorgeous background dancers and surfers made up for it.

In addition to the famous song that launched the Beach Party genre, I would also direct you to my personal favorite: the contrapuntal duet the couple sings in Beach Blanket Bingo (1965). As the couple walks along the beach at night, they each give their version of what the future looks like for them. She wants a ring; he wants to fool around. “I think, You think” may be a stark reminder of the constrictive nature of 1960s gender roles, but it’s still a delightful pop tune evocative of summer flings and carefree evenings spent by the ocean.

5. James Brown “I Got You (I Feel Good)” (1965)James Brown gave a rendition of his song “I Got You (I feel Good)” in Ski Party, one of the last of the era’s beach teenpics. Having exhausted the genre, filmmakers took the surfers to the slopes and James Brown got to perform in a garish wool sweater. This song reminds us that the beach movies famously lacked diversity, and kept people of color on the sidelines, only allowing them to appear as musical acts, fully clothed. In fact, it is worth remembering that at the same time as these movies were being released, African Americans in the South were staging swim ins to claim their right to the beach and the ocean. Brown’s electrifying performance for Ski Party stands as a stark reminder of the racial segregation and exclusion of that period.

Another famous Black artist who had a small role in a beach party movie is Stevie Wonder, who made his first appearance on screen, aged 13 years old, in the strangely compelling Muscle Beach Party (1963).

6. Jimi Jamison “I’ll Be Ready (Baywatch theme)” (1993)In the 1990s, Baywatch epitomized beach culture, its red swimsuits and slow-motion rescues defining an era. Jamison’s powerful vocals and uplifting melody became the sonic emblem of the show’s beautiful bodies and easy lifestyle (casting aside the actual job of saving people from drowning). And that song, and all that it carried, travelled far. Let’s not forget that Baywatch was rescued from cancellation after its first season thanks to viewers in Europe who couldn’t have enough of Pamela and the Hoff.

As my Northumbria colleague Joe Street told me recently, reminiscing about his youth in 1990s Britain, hearing the first notes of the song was the sign that pre-gaming for Saturday night could begin. A beloved “tea-time show”, you can easily understand why Baywatch was a hit in Britain where beaches are usually enjoyed wearing a raincoat and rubber boots.

Featured image via Pixabay.

Six books to read this Pride Month [reading list]

Six books to read this Pride Month [reading list]

As Pride Month blossoms with vibrant parades and heartfelt celebrations, it’s the perfect time to reflect and honor the rich tapestry of LGBTQ+ history and culture. Whether you’re looking to deepen your understanding, celebrate diverse identities, or simply enjoy compelling stories, our carefully curated reading list offers something for everyone. From historical explorations to helpful resources, these books provide invaluable perspectives and celebrate the enduring spirit of the LGBTQ+ community.

1. Forbidden Desire in Early Modern Europe [image error]Delve into the intricacies of sexuality and desire in Early Modern Europe with Noel Malcom’s seminal work, Forbidden Desire in Early Modern Europe. This scholarly masterpiece unravels the veiled history of male-male sexual relations, once shrouded in taboo. Malcom meticulously navigates through archives—from the bustling streets of Florence to the serene gardens of Venice—unveiling a clandestine world of desire that transcends societal norms. With unparalleled depth and insight, he challenges conventional narratives surrounding sexuality in the Early Modern era, presenting a range of human experiences across continents and cultures.

2. Unsuitable [image error]Buy Forbidden Desire in Early Modern Europe by Sir Noel Malcolm

Unsuitable invites readers on a journey through the hidden history of lesbian fashion. From the dapper attire of “Gentleman Jack” to the avant-garde fashion of genderqueer Berlin, this book illuminates the diverse and often overlooked contributions of queer women to the world of fashion. Unsuitable serves as a timely reminder of LGBTQ+ resilience and creativity, offering a kaleidoscopic view of trans lesbian style, Black lesbian Style, and gender nonconformity. Readers are invited to celebrate the vibrant spectrum of identity and expression that has shaped queer history— Unsuitable is an essential read that shines a light on a rich and often obscured legacy.

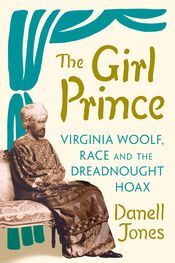

3. The Girl PrinceBuy Unsuitable by Eleanor Medhurst

The Girl Prince offers a captivating exploration of a little-known chapter in the life of Virginia Woolf, blending history, race, and identity into a compelling narrative. Set against the backdrop of Edwardian Britain, this book delves into Woolf’s audacious prank onboard HMS Dreadnought and its broader implications. The Girl Prince serves as a potent reminder of the complexity of identity and the intersection of gender and race. Through meticulous research and vivid storytelling, Danell Jones invites readers to reflect on the legacy of a boundary-pushing novelist—it is a thought-provoking examination of race, empire, and privilege.

4. Trans Bodies, Trans Selves [image error]Buy The Girl Prince by Danell Jones

Trans Bodies, Trans Selves is a groundbreaking and indispensable guide for the transgender community, written by transgender and gender-expansive authors. This comprehensive resource offers vital insight into the diverse experiences of transgender individuals: from medical and surgical transition to relationships, parenthood, and beyond. Inspired by the empowering ethos of “Our Bodies, Ourselves,” this book provides authoritative information in an inclusive and respectful manner, amplifying the voices of transgender people from all walks of life. With its commitment to representing the collective knowledge and lived experiences of the transgender community, this second edition is a testament to resilience, diversity, and the ongoing journey towards equality and understanding.

5. Trans Children in Today’s Schools [image error]Buy Trans Bodies, Trans Selves edited by Laura Erickson-Schroth

Trans Children in Today’s Schools is a timely and essential resource for educators, parents, and community members seeking guidance on supporting transgender youth in educational settings. This groundbreaking book shines a light on the challenges and barriers faced by transgender students and their families, providing practical strategies for creating safe and inclusive learning environments. Author Aidan Key expertly navigates beyond polarizing debates, focusing instead on the fundamental goal of ensuring all children have access to a supportive and welcoming educational experience. By challenging societal norms and advocating for gender-inclusive approaches, this book invites readers to join the paradigm shift towards a more affirming and equitable future for all youth.

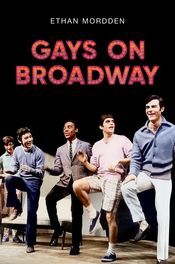

6. Gays on BroadwayBuy Trans Children in Today’s Schools by Aidan Key

Gays on Broadway provides a vibrant celebration of the LGBTQ+ community’s rich and enduring influence on American theater. From the genteel female impersonators of the early 20th century to the groundbreaking works of modern times, Ethan Mordden’s insightful chronicle traces the evolution of gay themes on Broadway with verve and wit. Against a backdrop of societal resistance and moral scrutiny, Mordden highlights the courageous artists and productions that pushed boundaries and paved the way for greater acceptance and visibility. From iconic plays to memorable characters, Gays on Broadway captures the spirit of defiance, creativity, and resilience that defines LGBTQ+ theater.

Buy Gays on Broadway by Ethan Mordden

You can explore these titles and more on Bookshop US and Bookshop UK.

Feature image by Brielle French via Unsplash.

June 1, 2024

Find your perfect summer read [quiz]

Find your perfect summer read [quiz]

As the warm breeze of summer can be felt, it’s the perfect time to dive into a captivating read that will transport you to another place. Whether you’re by the pool, on a sandy beach, or on the way to your next destination, take our short quiz to find your perfect summer read and browse our complete reading list to make your summer reading experience unforgettable.

Personalities Leaves from the Journal of Our Life in the Highlands Sand Rush Dublin Tales VeniceDiscover more titles to read this Summer here:

UK: https://uk.bookshop.org/lists/your-summer-2024-reads

US: https://bookshop.org/lists/your-summer-2024-reads

Featured image by S O C I A L . C U T via Unsplash.

May 29, 2024

From rags to riches, or the multifaceted progress of lady

From rags to riches, or the multifaceted progress of lady

Every English dictionary with even minimal information on word origins, will tell us that lord and lady are so-called disguised compounds. Unlike skyline or doomsday (to give two random examples), lord and lady do not seem to consist of two parts. Yet a look at their oldest forms—namely, hlāf-weard and hlæf-dīge—dispels all doubts about their original status (the hyphens above are given only for convenience). In the course of time, the first “halves” in those words yielded Modern English “loaf.” Originally, they meant “bread.” The components –dīge and –weard stood for “kneader” and “ward” respectively.

Today, –dīge means nothing to us. It is related not to the verb dig but to the noun dough. However, –dige has a much closer descendant in Modern English, namely, dey. At present, this word is regional. It was borrowed from Old Norse into Middle English and means “maidservant.” Its cognates occur everywhere in Modern Scandinavian, especially often in compounds. The story certainly began with a kneader, because Icelandic deig and German Teig still mean “dough.” Even the fourth-century Gothic, the oldest Germanic language known to us, had the same word.

Though the way from a “bread-kneader” (that is, “a servant”?) to “lady, mistress” looks odd, the other suggestions are even worse. The original OED admitted the implausibility of the proposed etymology, Skeat added perhaps to it, the second edition of the Century Dictionary did the same, and the attempts by early amateurs to explain lady as “bread-dispenser” cannot even be considered. For amusement’s sake, I may note that for some time, the tremendously popular Gentleman’s Magazine (1731-1922) coexisted with Lady’s Magazine (1770-1832). In both, I ran across a letter, published in 1772 and 1817, respectively. The texts are almost identical, and I suspect that the second one was a plagiarized version of the first. Here is the relevant passage from the earlier letter: “You must know, then, that heretofore it was the fashion for those families whom God had blessed with affluence, to live constantly at the mansion-houses in the country, and that once a week, or oftener, the lady of the manor distributed to her poor neighbours, with her own hands, a certain quantity of bread, and she was called by them the Leff-day, i.e. in Saxon, bread-giver.” This is pure fiction.

The Lady of the Lake.

The Lady of the Lake.Image by H.J. Ford, Wikimedia Commons via Picryl.

In 1992, Rainer Schulze, a German researcher, examined the entry lady in the OED and presented the word’s story in nineteen steps, which I’ll reproduce below in an abridged form (all my examples will also be borrowed from his paper). The main steps are as follows: someone who kneads bread; the female head of the household (a mistress in relation to servants or slaves); Virgin Mary (a most important leap), and Lady as the designation of the Virgin (Our Lady, finds its counterparts in Latin Domina Nostra, French Notre Dame, and elsewhere); a woman who rules over subjects; a woman of superior position in society; a woman who is the object of chivalrous devotion; a woman, loosely defined but of usually not very elevated standard of social position.

To be sure, side by side with lady, the word wife continued to exist, but it is worth noting how rich the history of lady turned out to be in comparison to the history of wife. Today, the old meaning of wife “woman” can still be discerned in fishwife and old wives’ tales. “The mistress of a household” is discernible in goodwife and housewife. By contrast, German Weib still means only “woman.” The interplay between Weib and Frau is also most interesting but has no direct bearing on today’s story, and I’ll let it be. Synonyms always struggle. Wife has been allowed to occupy one main niche (“spouse”), while lady moved in many directions.

Incidentally, Old English, like all the other Germanic languages, had a third word, not to be forgotten in this context. In Gothic, that word sounded as quino, and in Old English, as cwene. It still exists, though sadly “demoted” and little remembered: quean means “hussy; prostitute.” Side by side, but with a different (long) vowel, Old English cwēn “queen” existed. It probably first designated any woman and only later narrowed its meaning to “the wife of a king.” Quean and queen have always been related (in technical terms, their vowels represent two different grades of ablaut) and always designated “some kind of woman.” But the meaning of one synonym was “degraded,” and the meaning of the other “ameliorated.” Both are cognates of the Greek noun we recognize in gynecology.

A knight and his lady.

A knight and his lady.Image by Berendey_Ivanov / Andrey_Kobysnyn via Pexels.

It is amazing how often the most innocent words for “woman” fall victim to deterioration. For instance, the little-remembered huzzy is a contraction of housewife, that is, hūs-wīf, and whore is related to Latin carus “dear.” Against this background, the advancement of “bread-kneader” to “lady” is a most heartening event, assuming that lady did mean “bread-kneader.” In the quartet wife, queen, quean, and lady, only lady never meant “woman” in the past, but its time soon came.

Lord has hardly changed it semantics over the centuries, while lady kept developing ever new connotations. Here is an early example (I retain the spelling of the original): “For Ladies and women to weepe [that is, weep] and shed tears at euery little greefe [grief], it is nothing vncomely, but rather a signe of much good nature and meekness of minde [sic]” (1589). Ladies here are obviously women of high social standing. Soon, Lady Beauty, Lady Largess, Lady Pleasure, and even Lady Law and Lady Money appeared! At the same time, lady emerged as a synonym of “lover, mistress,” and in the eighteenth century, lady-love made its entry.

The sense of lady as an intensification of the honorary title arouses no surprise. When women began to compete with men for all kinds of historically “male” positions, all kinds of coinages became necessary. Chairman became Chair, firemen yielded to firefighters, waitresses to servers, and so forth. Adding Lady to Mayoress looked like a clever combination in 1967. At the same time, lady became a polite (genteel?) synonym for woman (three young ladies, and the like). We may remember that in George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion, Professor Higgins thrust a piece of chocolate into Eliza’s mouth, and she swallowed it, because it would have been not “lady-like” to spit it out. Yet the word’s old connotations never disappeared.

This is a ladybug with its surprising name.

This is a ladybug with its surprising name.Image by Marek Piwnicki via Pexels.

As a postscript, something should be said about ladybug. Numerous sources inform us that according to some legend, afflicted farmers prayed to the Virgin Mary to save their fields from the pest that endangered them. Allegedly, She sent thousands of ladybugs to the fields, and those ate up the dangerous insects. The grateful farmers called the insect after Her. No one gives references to the source of the legend, which, I believe, should be ascribed to folk etymology. Considering the ladybug’s appearance, the true reference may perhaps be to the Virgin’s seven sorrows or to the multicolored dress in which She is represented in late medieval paintings. The word ladybug and its likes have spread all over Europe, but the occurrences do not antedate the eighteenth century.

Finally, I would like to thank our reader for the comment on fink in the previous post and wish everybody affluence with or without a country mansion.

Featured image by Olia Danilevich via Pexels.

May 27, 2024

Human vulnerability in the EU Artificial Intelligence Act

Human vulnerability in the EU Artificial Intelligence Act

Vulnerability is an intrinsic characteristic of human beings. We depend on others (families, social structures, and the state) to enjoy our essential needs and to flourish as human beings. In specific contexts and relationships, this dependency exposes us to power imbalances and higher risks of harm. In other words, it increases our vulnerability.

The digital revolution has amplified this phenomenon—exposing our lives to addictive social media architectures, mentally manipulative commercial practices, the exploitative and abusive collection of behavioural data, more sophisticated and hidden forms of discrimination, and much more. The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is the first “digital law” that seems to recognize the enhanced vulnerability of online users. The notion of “vulnerable consumers” (introduced in the EU law in 2005 via the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive) has some similarities with the idea of “vulnerable data subjects”. But who are the vulnerable data subjects in the digital ecosystem? Or, better, what might they be vulnerable to? In which contexts? Towards whom?

These questions have become much more urgent due to the EU Artificial Intelligence Act (hereinafter AIA), the most discussed EU law of our age. The final text was approved by the European Parliament on 13 March 2024, and will be fully applicable in two years. There are 16 references to the notion of human vulnerabilities in the final text of the AIA. For example, AI systems exploiting certain human vulnerabilities are now officially forbidden (Article 5(1)(b)). In addition, human vulnerabilities are a parameter to update the list of “high-risk AI systems” in the future (Article 7(h)). Such vulnerabilities must be analyzed and mitigated in the new Fundamental Rights Impact Assessment by high-risk AI deployers (Article 27) and considered with “particular attention” by the market surveillance authorities when dealing with AI systems presenting risk (Article 79(2)). The AIA “Codes of conduct” will need to assess and prevent the negative impact of AI systems on vulnerable persons (Article 90). Within the context of regulatory sandboxes in the AIA, the data subjects in a condition of vulnerability due to their age or disability must be “appropriately protected” (Article 60).

Despite all these references to human vulnerability, there is still considerable uncertainty about the concept. Article 3 of the AIA contains 68 definitions of concepts and terms—none of which are about human vulnerability. In addition, the language and the semantics referring to vulnerability vary greatly throughout the text of the law.

Article 7(h)

Despite the lack of a definition, the most exhaustive and fruitful reference to a conceptualization of vulnerability is in Article 7(h). If the European Commission wants to update the list of high-risk AI systems in the future, it has to consider, among other parameters, “the extent to which there is an imbalance of power, or the persons who are potentially harmed or suffer an adverse impact are in a vulnerable position in relation to the deployer of an AI system, in particular due to status, authority, knowledge, economic or social circumstances, or age”. Here, the AIA explicitly refers to the concept of vulnerability as a gradual, contextual element. The language “persons… in a vulnerable position” conveys the idea that vulnerability is an accessory condition and not a label that can define people. It can also be inferred that vulnerability is relational (“vulnerable position in relation to”) and based on “power imbalance”, which might be generated by personal characteristics of the powerless person (“knowledge, age, status”), of the powerful party (“authority”), or by social factors (“economic or social circumstances”). These are not the only possible sources of vulnerability admitted in the AIA since Article 7(h) says “in particular”, admitting other structural, external or internal conditions that might generate vulnerability.

The AIA’s preamble contains three more specific cases of human vulnerabilities. In particular, it includes: children’s vulnerabilities online (recital 48); people applying for or receiving essential public benefits or services because of their typical “dependency” on those benefits (recital 58); and people who are subjects to AI systems in migration, asylum and border control management (recital 60), since they are “dependent on the outcome of the actions of the competent public authorities”. Interestingly, these last two cases explicitly relate vulnerability to dependency, in correlation with the traditional legal literature on legal vulnerability (see, e.g., Martha Fineman).

Article 5(1)b

Article 5(1)(b) AIA prohibits the commercialization or use of an “AI system that exploits any of the vulnerabilities of a person or a specific group of persons due to their age, disability or a specific social or economic situation, with the objective, or the effect, of materially distorting the behaviour of that person or a person belonging to that group in a manner that causes or is reasonably likely to cause that person or another person significant harm”.

Although it seems to refer to “any of the vulnerabilities of a person or a group”, it clarifies specific sources of vulnerability (“their age, disability or a specific social or economic situation”). While we might easily interpret cases of vulnerability based on “age and disability”, the notion of “specific social or economic situation” seems vaguer. Recital 29 mentions some non-exhaustive examples, i.e. “persons living in extreme poverty, ethnic or religious minorities”. However, a simple textual analysis of the AIA should push for a more comprehensive list of cases, including people with lower incomes or who belong to specific marginalized groups, e.g. political, linguistic or racial minorities, migrants, LGBTIA+ people.

Some striking examples of vulnerability situations excluded from the wording in Article 5 AIA are victims of gender-based violence, employees, patients (without disabilities), gamblers, and people addicted to social media or with other specific addictions. This is unless we accept an extensive understanding of “specific social situation” or of disability (which is not possible, due to the explicit reference to the Directive (EU) 2019/882, defining disability on long-term impairments and barrier-mediated limitations to equal participation in society).

Conclusions

We observe that the references to vulnerability factors in the AIA are much broader in Article 7(2)(f) than in Article 5(1)(b), where there is no specific reference to power imbalance, authority, or knowledge asymmetry. The reason for this discrepancy is probably that Article 5 strictly prohibits AI practices, while Article 7 instead provides the regulator with instructions. Accordingly, the list in Article 5 should be clear and foreseeable. However, the “social or economic situation” in Article 5(1)(b) is anything but.

In conclusion, although the AIA is one of the world’s most advanced pieces of legislation regarding the recognition and protection of human vulnerabilities, the concept is still complex and problematic. The interpersonal, relational, contextual and power-imbalanced notion of vulnerability highlighted in the data protection literature still seems extremely pertinent and meaningful. However, the prohibitions of vulnerability exploitation in the AIA show many gaps, e.g. for what concerns some sources of vulnerability (employees, healthy patients, addicted consumers, or victims of gender-based violence). Furthermore, the broad concepts, of power imbalance in Article 7 and social conditions in Article 5, will need specific authoritative interpretations in the coming months.

May 25, 2024

Kids, race and dangerous jokes

Kids, race and dangerous jokes

I wish that everything my children will hear about race at school will be salutary, but you and I know it won’t. Their peers will expose them to a panoply of false stereotypes and harmful ideas about race, and much of that misinformation will be shared in the guise of humor.

The New York Times recently asked teens about their experience of racist jokes in school. Kaylee, at Bentonville West High School, wrote that racist humor at her school is “as common as the amount of people with Stanley cups, they’re everywhere. You hear them directed at you, directed at others, directed towards teachers, toward your dog, toward your mom….” (Stanley cups are so trendy that people have camped out in parking lots to buy them.) Kaylee goes on to describe the jokes, and others laughing at them, as “diminishing.” Kaylee’s description is apt. Jokes like this convey negative ideas and stereotypes that play a role in maintaining unjust social hierarchies, thus belittling people by lowering them in power and status. Further, I believe that wholehearted laughter at racist jokes—as opposed to, say, an uncomfortable or involuntary giggle—welcomes belittling ideas into a conversation.

Another student who participated in the conversation with the Times, Caio from High Tech High, wrote, “School administration should require guilty students to attend a lesson that teaches in detail how making racist jokes perpetuates racism.” While I believe Caio is right that racist jokes perpetuate racism, I think that many of the cultural ideas that we hold about derogatory jokes—like the idea that it’s OK to tell derogatory jokes about one’s own social group—are mistaken. Given the ample evidence that our culture does not understand how derogatory joking works, there are very few people who could construct the lesson plan that Caio envisions.

Many teens, like many adults, don’t think that racist humor is always wrong; Abigail from New York told the Times that “depending on who you’re with or where you are, [racist or other hateful] jokes can be okay. If a person of that race is telling the joke, I feel it is fine. If someone is ever offended, then the joke should stop, but if it’s all fun and laughs, it’s fine. Maybe a place like school or work isn’t okay, because you never know who could take it the wrong way. If you’re just hanging out with friends, it should be fine.”

Abigail’s opinion that you can kid around about race with friends is widely shared among adolescents. Research tells us that even though teens think that joking about race or ethnicity with your friend group is harmless, in fact it has negative consequences. For example, Douglass et al. (2015) found that teens who are generally not anxious experienced more anxiety if they directed racial or ethnic humor towards themselves. For teens who already experience anxiety, the same humor from others that they dismiss as harmless—just their friends kidding around—raises their social anxiety not just on the day that it happens but on the following day. Over the course of three weeks, the teens in this study experienced an average of 3.49 incidents of racist or ethnic humor in their friend groups. Thus, socially anxious adolescents had an average of a little over two days of anxiety every week because of jokes that they deem harmless.

This study did not consider the effects of racial or ethnic humor on what teens believe about race or ethnicity, nor on how they act. But we can extrapolate from research with adults, which shows that exposure to derogatory humor affects adults who are already prejudiced against the derogated group. For example, for people who are prejudiced against Muslims, anti-Muslim jokes (not anti-Muslim statements) affect how they perceive an incident in which a manager sends a Muslim woman to work in the stockroom, rather than with customers, because she is wearing a burqa. The effect is limited to groups that the researchers characterize as groups of “shifting acceptability”—these are groups where social attitudes are in flux, moving from a time when prejudice was widespread to a time when prejudice against the group is less socially acceptable. So, for example, for people who are prejudiced against gay people, exposure to anti-gay jokes decreases how much money they are willing to allocate to an organization that promotes “the political and social advancement” of gay people; but for people who are prejudiced against racists, jokes about racists have no effect on how much money they are willing to allocate to a similar organization that promotes the advancement of White people. There’s no reason to think that adolescents are immune to these effects in a way that adults are not.

In adults, there is no evidence that exposure to racist jokes makes people more racist; rather, it seems to encourage the expression of pre-existing racism. However, adolescents are still mapping the social world in a way that many adults are not; while I was working on Dangerous Jokes, I read and heard anecdotes from adults who recall gleaning derogatory ideas and stereotypes about social groups from humor. I suspect that racist jokes spread and cultivate prejudice among young people by introducing negative stereotypes and ideas about race in a way that many adolescents consider socially acceptable.

Featured image by Caroline Hernandez via Unsplash.

May 24, 2024

When health care professionals unintentionally do harm

When health care professionals unintentionally do harm

The Hippocratic Oath, which is taken by physicians and implores them to ‘first, do no harm,’ is foundational in medicine (even if the nuances of the phrase are far more complex than meets the eye). Yet what happens when doctors bring about great harm to patients without even realizing it? In this article, we define microaggressions, illustrate how they can hinder the equitable delivery of healthcare, and discuss why the consequences of microaggressions are often anything but “micro”.

What are microaggressions?Microaggressions can be defined as actions, gestures, or even environments that subtly and often unintentionally harm members of marginalized groups. Some examples include when a healthcare professional speaks slowly and loudly to an elderly patient (who is neither hard of hearing nor cognitively impaired) and when medical clinics don’t have hospital gowns or blood pressure cuffs that fit people with larger bodies (or furniture that they can comfortably use).

In response, you might think that in the first case, it’s just an honest mistake committed by a well-meaning individual; and in the second case, it’s not a big deal since it’s nobody’s fault—there’s not even a specific individual to hold responsible.

So how and why are each of these examples microaggressions? And what kind of harm do they cause?

The healthcare professional who speaks loudly and slowly to an elderly patient, based on assumptions and stereotypes about what elderly people are like, might be thinking that they are acting in a way that can benefit the patient. Their reasoning (conscious or not) might be something like this: “elderly patients tend to be hard of hearing and suffer from cognitive impairment and thus the louder and more slowly I speak, the more it will help the patient hear and understand what I’m saying.” However, this elderly patient is not hard of hearing or cognitively impaired. In fact, the loud, slow speaking lands quite differently from their perspective. It might make them feel as though the healthcare professional has not taken the time to get to know them. This can lead to the patient not feeling properly seen, heard, or understood. And this, in turn, can result in the patient not feeling comfortable around the healthcare professional and not trusting them.

With regards to medical clinics not having hospital gowns or blood pressure cuffs that fit patients with larger bodies, or furniture that can comfortably accommodate them, one might think that given the relatively small number of patients who might need to make use of these resources, the impact is relatively low. But the Hippocratic Oath and the imperative to “first, do no harm” applies to all patients—some patients should not be excluded from proper care simply because their bodies fall outside of a normative ideal of what bodies ought to look like. All patients deserve recognition, respect, and the means to receive comprehensive, high-quality care. To be denied this sends the message that one is abnormal, that they do not belong, or that they are not respected enough to be treated fairly in healthcare spaces.

How do microaggressions hinder the delivery of healthcare?As we can see from these examples, the harms of microaggressions are only “micro” from the perspective of the one committing them. From the perspective of patients, the harms aren’t “micro” at all. Microaggressions can result in the immediate harms of feeling disrespected or invisible. But they can also contribute to long-term harms. For the elderly patient, even though the microaggression was committed with no ill intent, the healthcare professional failed to treat the patient as a dignified human being, worthy of respect. As a result, the patient’s sense of self is undermined and the stigma associated with being elderly in an ageist society is worsened.

The same is true with pervasive anti-fat bias both within and beyond medical contexts. People with larger bodies are disrespected, degraded, and pathologized. When they enter medical spaces only to find that their larger bodies literally cannot be contained by the furniture, that medical devices cannot be used on them, and that medical gowns cannot cover their bodies, their sense of self and self-worth is harmed. This can worsen anti-fat stigma and bias, making fat patients feel shame and hesitant to seek medical care at all.

The consequences of microaggressions are anything but “micro”Trust is the cornerstone of high-quality medical care. Yet microaggressions can corrode the trust of patients: both their trust of individual providers but also their trust in the institution of medicine more broadly. Distrust in practitioners and institutions can contribute to delaying or foregoing medical treatment, missed or incorrect diagnoses, prolonged illness, and sometimes even unnecessary death.

The upshot is this: when one’s health, well-being, and in many cases one’s very life is at stake, it’s imperative for there to be a trusting, positive relationship with those in charge of the treatment and care. Experiencing microaggressions in medical contexts, however, can undermine this trust. Thus, we must bring attention to microaggressions that arise within medical contexts in order to work to diminish them as much as possible. Doing so can be one important step in building a more just and equitable healthcare system.

Feature image by Online Marketing via Unsplash, public domain.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers