Oxford University Press's Blog, page 26

May 23, 2024

The year of singing politically: The 68th Eurovision Song Contest 2024 Malmö, Sweden

The year of singing politically: The 68th Eurovision Song Contest 2024 Malmö, Sweden

Welcome to the show. Let everybody know I’m done playin’ the game. I’ll break out of the chains.

—Nemo, “The Code,” winning song of Eurovision 2024

Breaking out of the chains had emerged as a central leitmotif and call for activism at the Eurovision Song Contest long before Swiss non-binary singer, Nemo, performed it as the winning song, “The Code,” at the Grand Finale on May 11 2024 in Malmö, Sweden. Though the lyrics could and did allow for different interpretations when the 2024 national entries first began to circulate on the internet—whose show, whose game, who’s everybody, who’s playing—ambiguity had been stripped away by the height of the Eurovision season in April. Nemo’s own breaking of the code became an allegory for direct engagement with the most unbreakable of all Eurovision codes: performance of politics, understated or overt, is strictly forbidden.

Nemo, “The Code,” Official Eurovision VideoViolating the code would lead to rejection of a national entry by the European Broadcasting Union (EBU), the largest broadcasting network in the world and the organizational infrastructure for the Eurovision itself. In extreme cases, when the politics of a song mirrored the geopolitics of Europe, violation of the code could lead to banning a nation from competing entirely, as it did in 2022 when Russia invaded Ukraine. The Eurovision Song Contest, in a word, should be apolitical. It should channel a cultural democracy for Europe heralded by an annual motto, this year “Unity by Music.” Such lofty goals for song may well be cause for celebration, but the reality of the largest music competition in the world, in which nation vies against nation on the global television stage, undermines the myth of a world without politics.

At Eurovision 2024, that myth would be fully dispelled. It was the announcement of the Israeli entry, Eden Golan and a song called “October Rain,” that in February forced the EBU into its attempt at apolitical activism. The title and lyrics of the song, according to the EBU, were direct references to the October 7th Hamas attack in Israel. Whether direct or not, always an abstruse category for EBU censors, Israel was given the option of withdrawing, substituting a new song, or altering “October Rain” to contain no political references. Israel chose the third of the options, entering with a song called “Hurricane”. With that entry, political controversy was unleashed, with calls for banning Israel because of its war in Gaza, which led in turn to massive demonstrations on the streets of Malmö and loud booing of Eden Golan at the semi-finals and finals—and a fifth-place finish in the May 11th Grand Finale, highly respectable under any circumstances.

Eden Golan, “Hurricane,” Official Eurovision video, Israel

Just how does the EBU and the organizers of the Eurovision Song Contest, including the host country that produces the shows for Eurovision Week, exercise its apolitical activism? To answer that question, one needs to consider the long history of the counterpoint between top-down organization by Europe’s media empire and the bottom-up participation of a musical citizenry seeking to win its place in a Europe constituted of diverse fragments. There are many ways to pose the question, but a critical way to answer it is to reflect on the different ways song itself expresses organization and participation.

In principle, any citizen of a nation whose broadcasting network is a member of the EBU has the potential to participate in the Eurovision. Competitions begin locally in the nation, move across regional boundaries, and eventually reach the stage provided nationally by the country’s broadcasting network, for example, the well-known Sanremo Song Contest in Italy. Winning entries are determined by a voting system that, though in variants among different countries, affords the feeling of democracy. The entry of San Marino (population 33,660) reaches Eurovision Week through a process that is comparable to that of Italy, albeit on a vastly different scale. The concept of Eurovision democracy in the bottom-up process is inherently political, which in turn is evident in the changing styles, languages, and symbolism of entries from year to year. Some nations choose to be more international, others recognizably national, for example, in the folk music-inflected entries of Croatia and Armenia on May 11th. The musical politics of some nations serve style and genre: for example, the consistent use of chanson and cabaret style by singers for France, the political meaning of the lyrics notwithstanding. In 2024, the LGBTQ+ signifying of the North African Muslim French entry, Slimane, fitted beautifully to the chanson style of his song, “Mon Amour.” National differences, when performed effectively, do not deter the voting public across Europe, who this year placed Croatia and France in the second and fourth positions.

The top-down musical democracy of the EBU and of the Eurovision Song Contest (as pageant and spectacle) depends on another set of criteria to enforce its apolitical activism. Not only the content of a song, but its structure must observe strict rules (for example, exactly three minutes, maximum six performers on stage). Infringing on these rules is an act of not belonging to Eurovision democracy. In 2024, as conflict and controversy enveloped the rest of the world, the EBU and the Swedish production team turned away from the roiling of external politics, instead looking inward, gazing at the Eurovision itself, its history, and a sort of fantasy world imagined as its alternative for Europe. In both the semi-final performances (May 7th and 9th) and the Grand Finale, the intermission acts on the stage in Malmö were consistently retrospectives of earlier Eurovision entries performed by former Eurovision stars. Host Sweden had made the decision that Eurovision 2024 should be a grand fiftieth-anniversary celebration for Eurovision 1974, won by ABBA singing “Waterloo,” the most popular song in Eurovision’s sixty-eight-year history. Many of the songs performed in the 2024 Eurovision imaginary came off as sad commentaries of a world no longer relevant, if apolitical. I found it rather pathetic to watch Johnny Logan (“Mr. Eurovision” from the 1980s and 1990s) during the first semi-final singing Loreen’s 2012 winning song, “Euphoria.” When Loreen, the Swedish winner from 2012 and 2023, introduced her “new song” at the appropriate ritual moment in the entr’acte of the finals, it was barely distinguishable from those earlier songs, as if she was trapped in a cycle of covering herself.

As the political world did battle with the apolitical world, it was the former that broke through, opening the stage for a politics that could capture a new attention. Criticism of the politics of ongoing war, in Gaza and Ukraine, can be openly expressed. Engagement with a different Europe, one unsettled, not united, by music, might someday occupy a presence on the Eurovision stage. In 2024, we witnessed that presence in the powerful cry to humanity in the Ukrainian entry of Alyona Alyona and Jerry Heil, “Teresa and Maria,” which concluded the Grand Finale in third place. As I did in my blogpost last year, I give the final words in 2024 to Ukraine, which show us why the Eurovision really can and should matter.

Spring makes its path, no matter what.

The world is on her shoulders,

Misled, winding, rocky. . . .

All the divas were born

As human beings with us.

Featured image by Arkland via Wikimedia Commons. CC4.0.

Working together: William Walton and Oxford University Press

Working together: William Walton and Oxford University Press

The British composer Sir William Walton (1902-1983), writer of operas, symphonies, concertos, and instrumental music, enjoyed an exclusive publishing relationship with Oxford University Press from the mid-1920s until his death. The works collected in OUP’s twenty-four volume William Walton Edition are representative of all that composer and publisher together achieved. Sitting behind the published scores, however, is a collection of materials relating to the original publications, amassed during Walton’s lifetime and now in the OUP Archive: proofs, copyist’s scores, early versions, original orchestral parts, conductor-marked scores, programmes, and correction sheets. Together these artefacts, the chippings on the workshop floor, tell the story of publisher working with composer, bringing to life a corpus of music now known and admired worldwide. Let us glance at some of the collection’s most revealing items.

Troilus and Cressida: first thoughts Christopher Hassall’s early draft of the libretto for Troilus and Cressida.

Christopher Hassall’s early draft of the libretto for Troilus and Cressida.Despite playing to mixed reviews Troilus and Cressida was, in the words of Walton’s biographer Michael Kennedy, ‘the opera he wanted to write’: large-scale, big-boned, romantic. This complete recasting of Chaucer’s masterpiece Troylus and Criseide was composed to a libretto by Ivor Novello’s collaborator Christopher Hassall. Surviving in OUP’s collection is Hassall’s first draft, neatly scribed in a wartime issue ‘Stationery Office’ folio notebook. Now looking back at this draft, the libretto as finally set by Walton is all but unrecognizable within it. Hassall’s first version reads more as a play, having none of the crisp concision characteristic of an opera libretto—it is expansive, wordy, and overflowing with a cast of superfluous ‘extras’. While a few of the draft’s choice phrases (Pandarus on Troilus: ‘On jealousy’s hot grid he roasts alive’) survived into the final text, and a couple of the opera’s eventually famous set pieces (for example, the female chorus ‘Put off the serpent girdle’) were there, in some form, from the start, it is clear that it was only the ruthless cutting and re-writing undertaken by Hassall and Walton (as, for years, they worked together on the opera) that transformed it to become the spectacular piece of musical theatre first revealed as the curtain of the Royal Opera House rose on the night of 3 December 1954. Embedded in the draft, though, are many ‘lost gems’—it’s tempting to speculate on what otherwise might have been. Text, subsequently cut, for a humorous ‘round’ or ‘catch’, to be sung at sunrise, might well have resulted in a perfectly sardonic Waltonian redress to traditional and benign views of larks ascending: ‘Hark, hark, the horrid lark hilariously calls! How sprightly and depressing! How soon that tuneful blessing disgruntles and appalls!’. In all, this long-forgotten manuscript has a multitude of stories to tell.

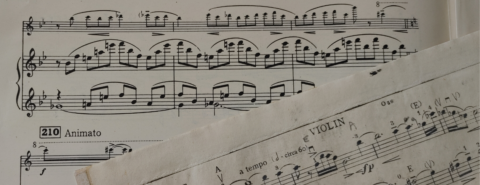

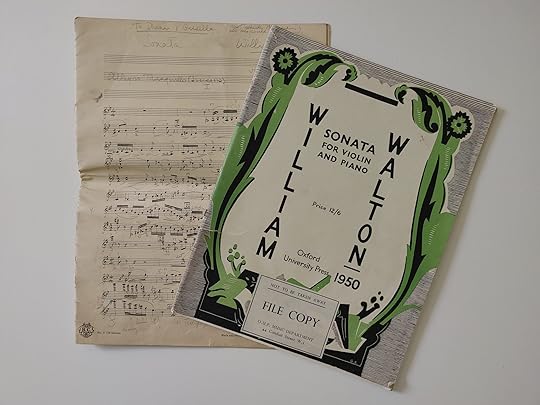

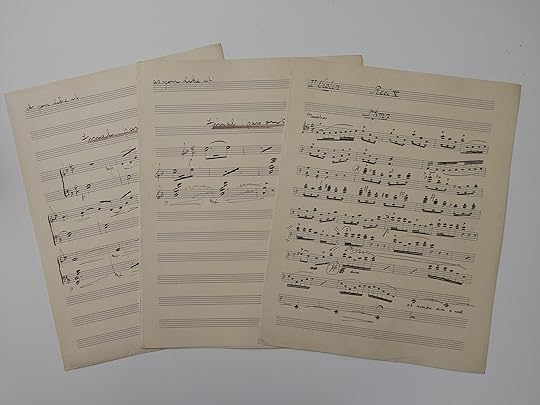

Walton, Menuhin, and the Violin Sonata The Violin Sonata: Yehudi Menuhin’s marked and edited ‘pre-publication’ copy of the violin part

The Violin Sonata: Yehudi Menuhin’s marked and edited ‘pre-publication’ copy of the violin part‘Work in progress’ of a different order is preserved in a pack of materials relating to Walton’s Sonata for Violin and Piano. This was written for Yehudi Menuhin: he and the pianist Louis Kentner gave a public ‘run through’ in Zürich in 1949. They gave the first performance of the by then definitive version in London on 5 February in the following year. That London version had been ‘overhauled’ by Menuhin to the extent that upon receipt of Menuhin’s edited violin part OUP wrote to Walton, ‘It really is quite a nightmare since there is hardly a note which hasn’t got a marking of some kind’. This edited solo part, and a set of proofs, survive—with their multiplicity of fingerings, articulation marks, queries, and dynamic markings, they together demonstrate dramatically Menuhin’s important contribution to the work’s final form. There is a separate note about bowings, flamboyantly signed by ‘Yehudi’—this eventually appeared in the published score.

Menuhin’s editorial note on his markings for bowing was printed in the published edition of the Violin Sonata.

Menuhin’s editorial note on his markings for bowing was printed in the published edition of the Violin Sonata.In May 1950 Menuhin and Kentner recorded the sonata for HMV. It is possible, by bringing this recording and the proofs together, not only to hear Menuhin creating the sonata in sound but at the same time also to watch him, collaborating with Walton through an intense shaping and a burnishing of the text, to perfection—a rare ‘open window’ on the creative process.

Outside the concert hall: big screen and airwavesSome collection items serve as reminders of Walton’s work in what today would be labelled as ‘media’—music not written for concert hall or theatre, but for the cinema, and for radio. Although OUP was not directly involved in Walton’s works for cinema, radio, and television, his editors would nonetheless proffer advice and assistance, and Walton and the companies often placed the scores with OUP to ‘look after’. In many cases OUP then published suites and other selections, suitable for concert use, using the materials entrusted to them. In 1936 Walton wrote the score for Paul Czinner’s film As You Like It (the first of Walton’s several Shakespeare film scores): while his autograph manuscript is today in the Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, surviving in the OUP collection are two bags containing the hastily-written orchestral parts used by the London Philharmonic Orchestra at the recording session—these show alterations made as the music was recorded to film. And for the music written for the BBC Home Service’s broadcast of Louis MacNeice’s radio play Christopher Columbus on 12 October 1942, a 160-page manuscript full score (in the immaculate hand of a professional copyist) survives.

Recording session orchestral parts for William Walton’s film score As You Like It.To the Bodleian Libraries

Recording session orchestral parts for William Walton’s film score As You Like It.To the Bodleian LibrariesOther collection highlights include manuscripts relating to the early performances of Façade: An Entertainment (and a 1926 London performance programme), an arrangement of the Spitfire fugue made for the band of Bomber Command, and Walton’s marked score for the Piano Quartet revision. Oxford University Press is delighted that the whole Walton publishing collection will, this year, be transferred to the Bodleian Libraries Special Collections at Oxford’s Weston Library where, in due course, it will be catalogued, stored, and curated. In doing so, scholars and all with an interest in William Walton’s music will be enabled to take a glance behind the covers of the published scores, finding out more about how his works took shape.

Photographs by Jerry Black

May 22, 2024

Fink, a police informer

Specialists and amateurs have long discussed fink, and the main purpose of today’s post is to tell those who are not versed in etymology what it takes to study the origin of an even recent piece of slang and come away almost empty-handed. Fink, which emerged about a hundred and thirty years ago, surfaced in American English and has American roots. In the linguistic journal Comments on Etymology for May 1, 1988, Archie Green listed thirteen hypotheses purporting to explain the origin, use, and spread of fink. The number thirteen need not surprise anyone: an obscure word tends to attract the ingenuity of specialists and amateurs, and while separating the wheat from the chaff in this mass, one sometimes emerges empty-handed: about everything turns out to be chaff. But such is the lot of the etymologist as winnower: wrong ideas are sometimes easy to discard—it is the right solution that often escapes us.

[image error]An etymologist as winnower.Image by Lorie Shaull via Flickr, CC2.0.

Since the late eighties, two papers on fink have appeared: one by David L. Gold (“The American English Slangism fink Probably Has No Jewish Connection,” 1998), an acrimonious but most useful study, and the other by William Sayers (“The Origin of fink ‘informer, hired strikebreaker’,” 2005; nothing new, can be disregarded). For entertainment’s sake, here are the thirteen hypotheses mentioned above.

1. From Mike Fink, an Ohio Mississippi River boatman (I’ll skip the legends about his treachery, because this is certainly not how our word emerged).

2. From Pinkerton detectives “in setting of assault on steel workers during Homestead strike, 1892.” “When armed Pinkerton guards and strikebreakers approached Carnegie Steel’s Homestead plant, an ensuing battle left a dozen dead and scores of wounded. Foreign-born workers picked up the battle cry ‘Th’ goddam pinks are comin’. Mispronunciation led to ‘goddam finks’.” Gold made a decisive objection to this hypothesis: what foreigners had an accent that required the substitution of f for p? Indeed, the most recent candidates I can think of were Germanic speakers who lived more two thousand years ago (that is why the English cognate of Latin pater is father; the process is known as the First Consonant Shift). The change of Pink to fink in the context we are discussing has no rational explanation. Yet a few sources half-heartedly accept this etymology, probably assuming that some solution is better than the off-putting verdict: “Origin unknown.”

Finks galore

Finks galoreImage by Library of Congress via Picryl. Public domain.

3. Fink is allegedly the ethnic name Finn, pronounced with final k. Obvious nonsense: those finks were not Finns, and whence final k?

4-5. From fenks ~ finks “fibrous parts of whale’s blubber; refuse of reindeer blubber.” Fink “prostitute” (from the sense mentioned above) had some currency in San Francisco, and perhaps it was applied to scabs as a term of disparagement. The derivation sounds sensible, but the path from “hooker” to “strike-breaker; informer” has not been traced, and I find it a bit hard to imagine a situation in which a male person (given the context we are now discussing) would be called a whore, even though offensive words are not particularly gender-specific (for instance, in Shakespeare’s days punk meant “prostitute”) and though terms of abuse easily change their targets. (By the way, note the geographic range: Mike Fink lived in Ohio, the 1892 strike occurred in Pennsylvania, and finks “hookers” flourished in San Francisco.)

6. Eric Partridge derived fink from funk. Many changes occur in unbuttoned speech, but why did the vowel change in funk? The history of funk, punk, and spunk, the words whose history I have once investigated, does not seem to provide any clue to fink.

7-10. Fink has been compared with finger (the reference being to finger “penis”), but no one could explain how finger became fink. In the nineteen-thirties, fink also meant “hobo, tramp,” as well as “non-spender.” Not improbably, the sound complex fink has been coined more than once, and always with derogatory connotations. It would be an exaggeration to say that words ending in –ink usually have a negative sense, but occasionally they do suggest something insignificant or unpleasant, as in stink, blink, chink, wink, shrink, and their likes. Fink has indeed been recorded with the sense “any defective, worthless, or small article of merchandise.” Yet the role of sound symbolism in coining fink would be hard to demonstrate.

11. Fink as an anti-Semitic joke (from a proper name). David L. Gold discussed this etymology in detail and showed that the joke referred to in this context could not result in producing fink “despicable man, cheat,” let alone “strikebreaker,” and that it seems to have emerged too late for the role attributed to it. Fink “scab” surfaced in print in 1892 and must have existed some time earlier (by definition, the first attestation of a word means that it was coined before it appeared in a newspaper or a book), while Jewish jokes about a fink turn up only in the nineteen-twenties. Chronology may not be a decisive argument in this context, but as a general rule, whenever some derogatory word is ascribed to Yiddish or Hebrew, one should be extra careful. It is natural to turn to anti-Semites in looking for the origin of offensive speech, and the solution appears so often to be wrong that all such hypotheses require extra-careful vetting. As Gold says: “Pre-1894 Yiddish influence on American English is unlikely, and none of the Yiddish words is semantically similar to the English one.” The case is closed, I believe.

This is a finch, an innocuous, cleanly bird.

This is a finch, an innocuous, cleanly bird.Image by Lorie Shaull via Wikimedia Commons, CC4.0.

12-13. Finch as in bullfinch is a bird name, and the German cognate of finch is Fink. Fink used to mean all kinds of bad things, because the finch is known to peck in horse manure. I may add that many birds do the same (those interested in the subject may consult the entry cushat “wood pigeon” in An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction), but for some reason, finches have been chosen as the main object of disparagement. The alleged path from German Fink to English fink “strikebreaker” is far from straight. We are supposed to assume that the word fink was launched by native speakers of German, familiar with Fink as slang. Though the assumption is not fanciful, this may be all one can say about it. Fink, understood as a borrowing from German, is today the most often cited etymon of the English word.

Archie Green’s long essay reads like a thriller. It recounts the story of how the word fink has been used for a very long time and discusses all the proposed etymologies. At the end of the day, the origin of fink remains undiscovered. Perhaps from German, but why? Green says: “Most likely, a number of ‘origins’ will converge or reinforce each other to cover fresh discoveries.” I am not sure I can share his optimism. There are hundreds of slang words whose origin is hopelessly obscure. A word is coined, becomes common property, and soon no one remembers where and when it came into being. The same also happens to countless stylistically neutral words. To give one example: no one knows for sure the etymology of the word boy. Why should fink be more transparent?

Feature image via Library of Congress. Public domain.

The word on arithmetic

When we think of genre, it is often in the sense of literature or film. However, rhetoricians will tell us that genre is a concept that includes any sort of writing that has well-defined conventions, such as business memos, grant proposals, obituaries, syllabi, and much more. Even such workaday genres present complexities, pitfalls, and opportunities for refinement.

So consider the humble math word problem, a genre you may not have thought much about since high school. Word problems are the stuff of educators’ attempts to fit arithmetic and mathematics to real world situations. The concept goes back to ancient times and Babylonian math exercises connected to engineering, agriculture, and business.

Some of today’s problems are pretty elementary: If Sue has five dollars and spends three of them, how many dollars does she have left? But even for very simple arithmetic, there is a vocabulary of addition and subtraction; you translate the question into the rudimentary five minus three by knowing that spend means subtract.

But there are other ways to express subtraction.

If Sue has five dollars and gives three of them to Rick, how many will she still have?

The problem requires someone to know that giving something away indicates subtraction. But give can also indicate addition:

If Sue has five dollars and Rick gives her three more, how much money will she have?

An elementary school problem-solver needs to understand the difference between being the subject of giving or the object. More generally, they need to gain proficiency with genre clues, like “in total” or “in all” for addition, like “have left,” “more than,” “less than” for subtraction, and “each,” “times,” “doubled” for multiplication.

A number of studies have shown that providing good verbal clues improves children’s performance and allows them to get right to the arithmetic. Even a little specificity can help. Which of these do you suppose is easier for a first-grader?

There are five marbles. Two of them belong to Mary. How many belong to John?

There are five marbles. Two of them belong to Mary. The rest belongs to John. How many belong to John?

A 1991 study by Denise Dellarosa Cummins found that the second was easier because it contained more specific information about how many marbles John had. And the mean proportional accuracy increased from 30% for the first problem to 85% for the second.

Sometimes too, inconsistency can trip up a word problem. Take this one, adapted from a study by Anton Boonen and colleagues: “At the grocery store, a bottle of olive oil costs $7. That is $2 more than at the supermarket. How much will a bottle of olive oil cost in the supermarket?” Here the use of “more” may prompt an addition strategy rather than a subtraction strategy, giving the wrong answer of $9 rather than the correct $5.

Like any genre, word problems get more sophisticated with age. Some require translation into mathematical concepts plus a knowledge of mathematical problem-solving tricks. How about this one:

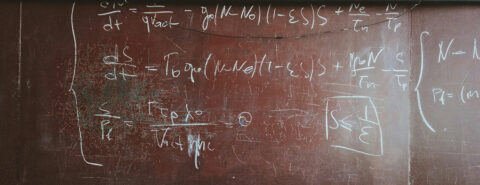

Two cars are 300 miles apart on Interstate 80, which has a speed limit of 65 miles per hour. One is driving 10 miles per hour faster than the other and they pass each other after three hours. How fast is each car going?

Here you need to know the formula distance = speed time. And you need to know the trick that the combined speed can be expressed as the speed of the slower car plus 10. In other “words”, 300 miles = 3 hours (slower speed + slower speed + 10). And that means that the speeds are 45 and 55 mph. The information about the highway and the speed limit are irrelevant, but if you follow the genre convention that all the numbers in a problem are important, it’s possible to get distracted.

If you can see through the distractors, remember the formula, and realize that the combined rate is 100 mph, the problem is not too hard.

Sometimes, the expectations of the genre can entice children to look for answers that are not there. Yet another study gave 97 first and second-graders this problem:

There are 26 sheep and 10 goats on a ship. How old is the captain?

Seventy-six students used the numbers to “solve” the problem. The expectation that there should be a solution and that you should do something with the numbers drove young learners to find one.

When students struggle with word problems, they are often struggling with wording. Adults too, perhaps.

Featured image by Roman Mager on Unsplash

May 21, 2024

Here’s Johnny––and Bette!

New York-based talk shows in the 1970s offered plentiful opportunities for quirky young talents like Bette Midler to sing a song or two and maybe kibitz with the host, regardless of whether they had a Broadway show or film or new record to promote. Midler had none of these when her manager Budd Friedman got her booked on The Tonight Show starring Johnny Carson not long after she began her legendary run at the Continental Baths. Her bawdy alter ego, the Divine Miss M, was birthed during late night performances for an audience of gay men sitting at her feet, naked but for skimpy bath towels. The Divine Miss M brought together gay, Jewish, feminist, and show business sensibilities in a package that combined raucous comedy, a jukebox’s worth of old songs re-energized, and devastating ballads that brought tears as well as cheers. Midler immediately became the most celebrated new star New York’s gay cognoscenti.

Carson’s flirtatious/fatherly chemistry with Midler continued during her frequent visits over the next twenty years. In 1973, now a best-selling recording artist and concert star, Midler made a triumphant return in all her curly, red-haired glory. Midler, musical director Barry Manilow, and her backing trio, the Staggering Harlettes, tore the place up, with the Harlettes’ “Optimistic Voices” leading into Midler’s grand entrance for “Lullaby of Broadway” and a sizzling “Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy.” They were a sight: Midler spilling out of a garish evening gown, accessorized with stone martens and platform shoes, and the Harlettes in vintage tie-and-tails harmonizing and dancing their stylized 1940s moves like contemporary women giddily discovering a new/old musical world. Manilow and the band in their 1970s long hair and street clothes jammed in the background. If any single performance exemplified the musical and sartorial fun of the early 1970s nostalgia trend, it was surely this one.

In 1980, publicizing her new book, A View from a Broad, Midler looked remarkably subdued, wearing what she might sardonically call a “tasteful” ensemble of slacks, jacket, and high-necked blouse, with her now-blonde tresses pulled back behind her ears. But she’s as vivid a conversationalist as ever. When Carson asks if she ever envisioned she would be as big a star as she has become, her answer is a straightforward, sincere, “Yes.” But she’s quick to point out that her early view of stardom was superficial. “I didn’t realize that the one thing that’s worse than not being looked at is being looked at,” she says, before launching into a comic riff on being followed in the grocery store by fans who judge her food choices. “I can only go to the fancy food section now.” It was a perfect Midlerian anecdote: outlandishly funny, told with mock horror, but with an underlying seriousness that made it entirely plausible.

In 1983, she was pushing her new single, “Beast of Burden” and her new book, The Saga of Baby Divine, a lavishly illustrated children’s book with adult appeal. Her savage re-envisioning of the Rolling Stones’ hit began with her on the floor, crouching like a caged animal. A tight, spaghetti-strapped cocktail dress and spike heels didn’t inhibit her from dropping to her knees and “humping the floor,” as she liked to call it. The performance ended with a full round of microphone swinging that threatened to destroy the set. The topper was her ad lib as she took her seat next to Carson: “And she writes books too!”

Midler had just turned forty when she returned at the end of 1985, and unlike so many other women in show business, she wasn’t afraid to joke about getting older and trying to stay in shape. A bit more zaftig than usual, and ruing her love of food, she launched into “Fat As I Am” while seated between Carson and sidekick Ed McMahon and proceeded to take over the set, lounging on Carson’s desk, kicking off her shoes, and pulling every laugh out of the comic torch song.

Then she turned around and offered a heart stopping “Skylark” that surpassed her recording from the 1970s.

By her next appearance at the end of 1988, she was one of the most successful and highest paid women in films following a string of hit Disney comedies. She was there to promote her latest film, the dramatic musical Beaches, and was very much the regal film star, complete with an opulent mane of auburn hair cascading around her shoulders while performing “Under the Boardwalk,” from the film’s soundtrack album.

Midler was on another upswing when she returned just as For the Boys was opening in November 1991. The expensive and ambitious movie musical had good buzz and Midler, coming off big record and film hits, was in high spirits and looking splendid. It seemed more like The Bette Midler Show than The Tonight Show, with the star showcased in several songs from the film, including another impromptu (but not really) comedy number from her guest chair, making “Otto Titsling” a hellzapoppin’ history lesson about brassieres that even for her was wildly, comically flamboyant.

For the Boys was a high-profile failure for Midler and she laid low for months, finally reappearing, at Carson’s request, on his penultimate episode as host of The Tonight Show. After nearly thirty years, Carson was retiring from the show that had come to define late night television. His last guests were Midler and Robin Williams on 21 May 21 1992. It was rare for Robin Williams to be relegated to the role of second banana, but that night Midler left him in the dust. She pulled off one more sitting-on-the-chair song––this one for the television history books––with a specially-tailored version of “You Made Me Love You” and its introductory “Dear Mr. Gable,” first performed by Judy Garland to the movie heart throb, Clark. “Dear Mr. Carson” and “You Made Me Watch You,” with new lyrics co-written by Midler, Marc Shaiman, and Bruce Vilanch, hit all the comic bases, from Carson’s personal life (“I watched your hair turn slowly from dark to white/And when I can’t sleep I count your wives at night) to jokes about Ed McMahan and even Carson’s longtime producer Ted DeCordova (“Before you bid adieu/Don’t be cheap/Put DeCordova to sleep”). Midler was known for her razorlike timing, but her every slow take, grimace, and pause was delivered with comic perfection that was deepened by her genuine affection for and gratitude to Carson.

It was hard to imagine Midler topping that moment. But returning from a commercial, Midler sang Carson one last song. On a stool in the center of the soundstage, she delivered Johnny Mercer and Harold Arlen’s “One For My Baby (And One More For the Road),” turning this boozy barroom standard into a final, loving tribute, as if standing in for the millions who had watched him over the years. Midler could sometimes overdo the pathos, but here her smiling warmth was even more affecting because it kept the tears at bay. It was Carson who grew increasingly misty-eyed as the camera captured him over Midler’s shoulder while she bid him farewell on “that long, long road.” The moment was instantly iconic, a prime example of live television at its best.

The night was as much a milestone for Midler as it was for Carson. The eager, anxious-to-outrage young chanteuse had matured into an evergreen entertainer who could effortlessly toggle between uproarious comedy and deep emotion. All her Carson appearances had been notable, but this night it was impossible to imagine anyone in show business other than Midler creating this final moment for him.

Featured image credit: Publicity photo of Bette Midler from 1973 by Aaron Russo-manager. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

May 20, 2024

Did the Santa Barbara oil spill save our beaches?

Did the Santa Barbara oil spill save our beaches?

On 28 January 1969, a blowout on a Union Oil platform six miles off the Santa Barbara coast released three million gallons of crude oil into the ocean. As the first environmental disaster captured in technicolor and publicized across national news media, the Santa Barbara oil spill played an important role in the emergence of the modern environmental movement. According to an oft-cited anecdote, Wisconsin Senator Gaylord Nelson was flying home from California after having toured the oil-scarred beaches when he came up with the idea for a nationwide environmental teach-in. On 22 April 1970, his idea became reality when twenty million Americans attended Earth Day events, making it the second-largest protest in US history after the 2020 Black Lives Matter demonstrations. The disaster also provided a major impetus for the creation of the California Coastal Commission, the state agency in charge of reviewing permits for construction projects along the California shoreline and ensuring public access to the coast.

The oil spill was a momentous event in the history of environmentalism. But was it enough to save our beaches? Today, Southern California beaches are threatened by problems common to many other shores around the world: sea level rise, erosion, privatization, plastic and sewage pollution, and the legacy of toxic waste ocean dumping.

The aftermath of the oil spill carried two important lessons. The first is that no one is isolated from environmental problems, not even the rich and famous. In 1969, the oil spill came as a shock because places like Santa Barbara, home to many celebrities and elites, had been largely protected from the consequences of a fossil fuel-based economy. When the slick reached the shore, two worlds that were deeply entangled, but had always been deliberately separated, collided: the oil industry and the ultimate postwar dream of a California beach.

Today, many Malibu beach homeowners fight to keep the public off their sands. But they’re also battling climate change. By 2050, all but the largest Malibu beaches are expected to be below annual flood level due to sea-level rise. Such projections have yet to deter some homeowners from trying to save their small patch of paradise. In 2010, Broad Beach homeowners started an unprecedented, privately funded battle against rising seas. They’ve built an emergency seawall, which only makes erosion worse in the long-term, and trucked in offshore sand. But all the sand in the world and the highest seawalls will not solve a problem that can only be addressed collectively. If we want to keep our beaches, we need to stop releasing carbon into the atmosphere and leave them to do what beaches do, which is to wax and wane naturally as they’ve always done.

The second lesson from the spill is that cleaning beaches is pointless if we keep on trashing them. Fifty-five years later, oil spills have become a cost of doing business in a fossil fuel economy. The latest major spill, which affected Huntington Beach in 2021, was caused by a container ship’s anchor rupturing a seabed oil pipeline. Ships also regularly dump “bilge water,” engine wastewater full of oil and other toxic substances, into the ocean instead of treating it. In addition, sewage spills when storm drains overflow after big downpours continue to plague Los Angeles, despite the crusading work of Heal the Bay since the 1980s. More worrisome are the findings of recent seafloor explorations that chemical companies dumped DDT through the sewers and routinely unloaded leaking barrels of DDT off barges through the 1970s.

Finally, plastic pollution plagues California shorelines. In season 2 of And Just Like That…, the reboot of Sex and the City, the character Miranda Hobbes was filmed cleaning up a Malibu beach, just like California’s many dedicated, real-life volunteers. But even if Carrie Bradshaw and all her fans came out, there wouldn’t be enough hands to pick up the 1.5 Mt of microplastic that enter the ocean annually. Later this year, the United Nations is set to finalize and sign on a new global treaty to end plastic pollution. Stopping (or at least curbing) the production of plastics at the source—rather than once it has reached our shores—is the only way to truly address the problem. But the chemical and plastic lobbies are working hard behind the scenes to prevent the treaty from imposing a cap on production. Protecting beaches will also mean keeping an eye on these negotiations.

Beaches are places of joy, wonder, and play. It’s incumbent upon us to make sure they don’t just melt away.

Feature image by Gustavo Zambelli on Unsplash

May 14, 2024

Classical allusions in Owen and Rosenberg’s war poems

Classical allusions in Owen and Rosenberg’s war poems

Wilfred Owen is one of the most studied of the war poets, and his poem ‘Dulce et Decorum Est’ is undoubtedly the best-known example of classical reception in First World War poetry. The poem ends with seven Latin words from Horace Odes 3.2: dulce et decorum est pro patria mori—‘it is sweet and fitting to die for one’s country’. Owen bitterly denounces these words as ‘the old Lie’.

Modern readers are now more likely to identify the words dulce et decorum est pro patria mori with Owen rather than with Horace, but Owen himself was never fully proficient in Latin. He studied Latin at his first school, the Birkenhead Institute. But his family moved to Shrewsbury when he was 14 and this put an end to his formal study of Latin. His continued attempts to master the language on his own were never fully successful.

Most Owen scholars have not focused on the question of how he came to know the Latin phrase dulce et decorum est pro patria mori. This Latin ‘tag’ appears frequently in anthologies of famous quotations. It was also very popular as an inscription on gravestones and memorials, so Owen’s use of the Latin words is not direct evidence that he had actually read Horace Odes 3.2. In my previous work on Owen, I had assumed that he probably knew only dulce et decorum at second hand. But working on this commentary has changed my thinking on this question.

As I read and re-read Owen’s poems and concentrated on tracing any and all classical elements in them, it became evident to me that ‘Dulce et Decorum Est’ is not an outlier in Owen’s work. At least eight of Owen’s poems include Horatian connections, ranging from structural parallels to quotations, allusions, and echoes. Owen may not have progressed far enough in his formal Latin study to read Horace at school, but clearly he did indeed read at least some of the Odes at some point, and he engaged with Horace across a wide range of his own work.

As with Horace, so with other classical authors and with classical culture. Classics forms a crucial substratum for many of Owen’s works. This is evident in the published versions of some of his best-known poems. In addition, our commentary’s examination of Owen’s manuscript variants, discarded versions, and fragments reveals the importance of classics even for some poems where the printed versions retain no classical references at all. The manuscripts show that Owen considered incorporating a reference to the abduction of Persephone into ‘Exposure’, for instance. ‘Apologia pro poemate meo’ at one point contained a reference to Homeric gods watching human battles. One iteration of ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’ referred to the Homeric flowers asphodels among its imagery of mourning and remembrance. Among Owen’s juvenilia, ‘To Poesy’ (probably his earliest extant poem), directly states that thorough knowledge of classical culture, myth, and languages is crucial for a poet’s craft. Our commentary elucidates the extent to which Owen cleaved to this belief throughout his own poetic career. [Elizabeth Vandiver]

Isaac Rosenberg’s Trench poems offer poetic reworkings of images and motifs from antiquity that both complement and differ from the work of Brooke, Sorley, and Owen. Rosenberg was born in Bristol and killed in action in France 1918. He came from a poor immigrant family and his early education gave no opportunities for studying classical material. After leaving school, he was able to study at the Slade School of Fine Art, and he benefitted from contacts made at the Whitechapel Public library and via tutors at Birkbeck College, who lent him copies of the poetry of Donne, Blake, and Shelley. He was familiar with the Iliadic episodes of the Trojan War and probably also read Aeschylus in translation. His rabbinic cultural heritage had embedded knowledge of the episodes, figures, and imagery of the Hebrew Bible and he was sensitive to the language of the well-known English translation of the Old Testament, the King James Bible.

These elements came together in the poems that he composed during the war, often in extreme conditions in France—some surviving manuscripts are written in pencil on mud-stained scraps of paper. Rosenberg was a private soldier and only volunteered in the hope of obtaining an allowance for his mother. His letters contain harrowing details of the arduous conditions, compounded by the antisemitism that he encountered. However, he hoped that the experience of the war would enrich his poetry and was convinced that the task of the poet was to be ‘perverse’. His Trench poems rarely comment directly on the rights and wrongs of the war or on his own suffering. Instead, they focus on episodes in conflict, exploring and communicating these through images from Homer, the Hebrew Bible, and poetry in English. Our commentary maps these interactions and analyses their resonance for Rosenberg and for subsequent readers and poets. Key examples include the metaphor in ‘August 1914’ of slaughter in war as a desecration of harvest, bringing together Homer and motifs from the cultures of the ancient near-East. Its image of ‘A burnt space through ripe fields / A fair mouth’s broken tooth’ anticipates the post-war poetry of Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot.

Rosenberg’s poetic ‘perversity’ underpins his variations on the motif of the poppy, notably in ‘Break of Day in the Trenches’. In Homer, the fragility of the poppy was the metaphor for the death of Gorgythion in Iliad 8. In WWI Flanders, the poppy was not only a feature of the ecology but, according to Siegfried Sassoon, was, with the larks, a reassuring cliche favoured by journalists and the unknowing public back in Britain (for whom it later became an emblem of remembrance). In Rosenberg, the poppy is a symbol both of bloodshed and of nuanced sensibility. His capacity for creating images that were both tangible and ironic also opened the way for eco-critical readings of human agency and the environment. The commentaries explore connections between this thread and the ancient texts. [Lorna Hardwick]

Check out part one of this blog post from the authors of Rupert Brooke, Charles Sorley, Isaac Rosenberg, and Wilfred Owen: Classical Connections and Greek and Roman Antiquity in First World War Poetry: Making Connections

May 13, 2024

Are academic researchers embracing or resisting generative AI? And how should publishers respond?

Are academic researchers embracing or resisting generative AI? And how should publishers respond?

The most interesting thing about any technology is how it affects humans: how it makes us more or less collaborative, how it accelerates discovery and communication, or how it distracts and frustrates us. We saw this in the 1990s. As the internet became more ubiquitous, researchers began experimenting with collaborative writing tools that allowed multiple authors to work on a single document simultaneously, regardless of their physical locations. Some of the earliest examples were the Collaboratories launched by researchers in the mid-1990s at the University of Michigan. These platforms enabled real-time co-authoring, annotation, and discussion, streamlining the research process and fostering international collaborations that would have been unimaginable just a few years earlier.

Most people, but not all, would agree that the internet has benefitted research and researchers’ working lives. But can we be so sure about the role of new technologies today, and, most immediately, generative AI?

Anyone with a stake in research—researchers, societies, and publishers, to name a few—should be considering an AI-enabled future and their role in it. As the largest not-for-profit research publisher, OUP is beginning to define the principles on which we are engaging with companies creating Large Language Models (LLMs). I wrote about this more extensively in the Times Higher Education, but important considerations for us include: a respect for intellectual property, understanding the importance of technology to support pedagogy and research, appropriate compensation and routes to attribution for authors, and robust escalation routes with developers to address errors or problems.

Ultimately, we want to understand what researchers consider important in the decision to engage with generative AI—what excites or concerns them, how they are using or imagining using AI tools, and the role they believe publishers (among other institutional stakeholders) can play in supporting and protecting their published research.

We recently carried out a global survey of researchers to explore how they felt about all aspects of AI—we heard from thousands of researchers across geographies, disciplines, and career stages. The results are revealing in many important ways, and we will be sharing these findings in more detail soon, but the point that struck me immediately was that many researchers are looking for guidance from their institutions, their scholarly societies, and publishers on how to make best use of AI.

Publishers like OUP are uniquely positioned to advocate for the protection of researchers and their research within LLMs. And we are beginning to do so in important ways, because Gen AI and LLM providers want unbiased, high-quality scholarly data to train their models, and the most responsible providers appreciate that seeking permission (and paying for that) is the most sustainable way of building models that will beat the competition. LLMs are not being built with the intention of replacing researchers, and nor should they be. However, such tools should benefit from using high quality scholarly literature, in addition to much of what sits on the public web. And since the Press, and other publishers, will use Gen AI technologies to make its own products and services better and more usable, we want LLMs to be as neutral and unbiased as possible.

As we enter discussions with LLM providers, we have important considerations to guide us. For example, we’d need assurances that there will be no intended verbatim reproduction rights or citation in connection with display (this includes not surfacing the content itself); that the content would not be used for the creation of substantially similar content, including reverse engineering; and that no services or products would be created for the sole purpose of creating original scholarship. The central theme guiding all of these discussions and potential agreements is to protect research authors against plagiarism in any of its forms.

We know this is a difficult challenge, particularly given how much research content has already been ingested into LLMs by users engaging with these conversational AI tools. But publishers like OUP are well positioned to take this on, and I believe we can make a difference as these tools evolve. And by taking this approach, we hope to ensure that researchers can either begin or continue to make use of the best of AI tools to improve their research outcomes.

Featured image by Alicia Perkins for OUP.

May 9, 2024

The importance of sun safety: Sun Awareness Week 2024

The importance of sun safety: Sun Awareness Week 2024

Sun Awareness Week (6-12 May) kicks off the British Association of Dermatologists’ (BAD) summer-long campaign dedicated to raising awareness of non-melanoma skin cancer, a very common type of cancer. The week also aims to teach the public about the importance of good sun protection habits, including ways you can check for signs of skin cancer.

What is non-melanoma skin cancer, and how does it differ from melanoma?Non-melanoma skin cancer is a group of cancers that develop in the outer layer of the skin, unlike melanoma which starts in the cells that produce pigment in the skin.

The two most common types of non-melanoma skin cancer are basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas, which are keratinocyte cancers. They can be prevented and treated with sun avoidance behaviours, but their prevalence is on the rise.

John Ingram, Editor-in-Chief of the British Journal of Dermatology, believes that Sun Awareness Week is a good time to spotlight recent research outputs in the fields of melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer. A new collection from the BAD journals presents key research studies on the topic, ranging from the use of artificial intelligence large language models in management advice, to skin risk evaluation for people of colour with a history of non-melanoma skin cancer.

Let’s look at some of the key findings from the collection:

Actinic keratosis is a global health concernActinic keratosis is a form of dry, scaly patches of skin caused by sun damage. In a recent systematic review, it was found that actinic keratosis has a global prevalence rate of 14%, with prevalence increasing the closer you get to the equator. Wearing sunscreen and sun-protective clothing has been shown to help reduce its prevalence.

Genetic factors may put you at higher risk of nodular melanomaNodular melanoma is an invasive type of melanoma that appears as an enlarging lump that is often diagnosed at later stages than non-nodular forms of melanoma. A study found that an increased number of rare gene variants could help identify patients at higher risk of this form of melanoma.

People of colour at risk of developing melanoma following keratinocyte carcinomasPatients with a history of keratinocyte carcinomas are at an increased risk of developing melanoma but there is a lack of research on patients with skin of colour. A recent retrospective study investigated the risk of melanoma in skin of colour patients with a history of keratinocyte carcinoma and found that it was associated with an 85% increased risk of melanoma.

Non-melanoma skin cancer is predicted to have a higher mortality rate than malignant melanomaIn another recent study, it was predicted that non-melanoma skin cancer mortality will soon be higher than malignant melanoma, reaching this threshold first in Scotland (2028), followed by the United States (2031), Australia (2033), and England (2038), but later for Nordic countries (beyond 2050).

Autoimmune hepatitis is linked to melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer

Autoimmune hepatitis is linked to melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancerAutoimmune hepatitis is a disorder characterized by its remitting course, often requiring long-term immunosuppressive therapy. A study showed that patients with autoimmune hepatitis had increased odds of developing basal cell carcinoma, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and melanoma. Due to their increased risk of skin cancer, patients may benefit from regular dermatological care and skin examinations.

IBD drug is linked to a higher risk of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomaAzathioprine is a drug used to treat inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). A recent study found a 56% increase in the risk of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in patients taking azathioprine compared with those taking other immunosuppressive drugs. As newer immunosuppressive agents become available, clinicians should carefully consider the individual’s skin cancer risk before prescribing.

Self-perception impacts sun-related behavioursA survey of over 5,000 people found that those who perceived their health as positive were associated with higher odds of tanning and sunburn history. These individuals may be more likely to spend time outdoors and be more willing to practise risky behaviours.

Low sunscreen use recorded in studentsSunscreen use in the United States was shown to be relatively low in a student study, with men of colour and older adolescents at the greatest risk for not using sunscreen at all. Reasons for avoiding sunscreen use were multifactorial, including lower levels of skin cancer knowledge, viewing sunscreen as a beauty product, and social-cultural norms. Skin cancer prevention will need to target these specific populations to generate the most significant impact on changing sunscreen habits.

Can artificial intelligence (AI) provide clinical advice about melanoma?This study showed that ChatGPT marginally outperforms BARD and BingAI in providing reliable, evidence-based clinical advice for melanoma. However, these technologies still face limitations in depth and specificity and further research is needed to improve their performance.

Sun Awareness Week highlights the need for sun protection, education, and awareness about lesser-known skin cancers, as well as the increasing burden of non-melanoma skin cancer. If there are any changes to skin lesions or moles, then it is best to consult your doctor.

Contribute to the conversation this #SunAwarenessWeek and explore the latest research collection from the BAD journals.

Featured image by NicholayFrolochkin via Pixabay.

May 8, 2024

My word of the year: hostages

I have never been able to guess the so-called word of the year, because the criteria are so vague: neither an especially frequent word nor an especially popular one, we are told, but the one that characterizes the past twelvemonth in a particularly striking way. To increase my puzzlement, every major dictionary has its own favorite, to be named and speedily forgotten. The fateful 2024 has not reached even its middle, but since December is a long way off, I’ll volunteer to offer my own word of the year and say something about its murky origins. The word is hostage. It is not likely to disappear from our memory anytime soon.

Taking hostages in the Middle Ages.

Taking hostages in the Middle Ages.Image by J. Paul Getty Museum via Picryl. Public domain.

The Hebrew word “hostages” can be translated into English as “children of surety,” and in many languages the word for “hostage” means both “security, pledge” and “people captured (held) in pledge.” The Greek for “hostage” (hómēros) will come as a surprise to many. Is this, we wonder, the meaning of Homer’s name? Why was the most famous Greek in history called this? Since nothing is known about Homer, we will avoid guesswork. In any case, the word does not go back to the poet’s name: the opposite is true. Moreover, this noun occurs in neither the Iliad nor the Odyssey. Though its etymology is far from clear, hómēros does not seem to have emerged from any root meaning “pledge” or “security.” May the poet sleep in peace, while those whose only connection with Homer is by way of Homer Simpson enjoy their hero’s deeds. Needless to say, Homer is a fully acceptable name in today’s English-speaking world.

Contrary to Greek hómēros, many other European words for “hostage” make sense even to a non-specialist. Such is Italian statico (a little-known synonym for ostaggio), Russian zalozhnik (stress on the second syllable; zalog “pledge”; that is, “pledge-ling”), and even Latin obses, evidently, from ob-sed-s, though the connection between –ses and sedere “to sit” was probably no longer felt by Latin speakers (English obsess is not too far off!). Wherever we look, hostage means “pledge, security” and only then, by extension, “a person held as security.” In Ancient Greece and Rome, hostages were often handed over for the carrying out of an agreement and not as captives, and in medieval Europe, hostages were usually given, not taken.

Rollo, the husband of Gisela.

Rollo, the husband of Gisela.Image by Pradigue via Wikimedia Commons. CC1.0

Among the European words for “hostage,” the ones from Germanic are particularly obscure. In Old English, we find gīs(e)l ~ gȳsel (read ī as Modern English ee and ȳ as long German ü). The other Germanic languages had close cognates of gīsl but unlike Modern English, have retained them. Such are, for example, German Geisel and Dutch gijzel. Gisela, the wife of the Francian Viking king Rollo (from Hrólfr?), spoke a dialect of Romance but had a Germanic name that must have meant “pledge” (medieval marriages were certainly not made in heaven). To this day, we meet not only Homers but also Giselas. In Scandinavia, many men were called Gísli. The Saga of Gisli (Gísla saga) is one of the most memorable and intriguing tales that have come down to us from the Middle Ages.

Old Norse gísl is an obvious cognate of the words cited above. It continued into all the Modern Scandinavian languages, but strangely, some reconstructed protoform like geisla does not resemble any other Germanic word. Yet it seems to have strong ties with Celtic. Irish giall ~ geill “deposit, pledge” (from Old Irish gíall) looks similar to gīsel, and most language historians treat the Germanic word as a borrowing from Celtic. They reconstruct some ancient root like gheis- ~ ghis-, followed by a suffix.

Why this root meant “pledge” remains unknown: no light on it falls from Sanskrit, Greek, or Latin. The verb for “give” sounds a bit similar, but the similarity must probably have been due to chance. By contrast, the fact of borrowing need not surprise us. The ancient speakers of Celtic and Germanic lived in close proximity from time immemorial, and in some respects, the culture of the Celts was superior to that of their neighbors. Quite a few terms of industry and societal organization reached the ancestors of the Scandinavians, Germans, and Anglo-Saxons from the Celts. Hostage “pledge, security; a person taken as security” was, quite obviously, a legal term, part of the vocabulary of societal organization.

The word for “hostage” does occur in the Old Testament and has a familiar ring. In the Revised Version, we read: “And he [Jehoash, king of Israel] took all the gold and silver and all the vessels that were found in the house of the Lord, and in the treasures of the king’s house, and hostages, and returned to Samaria” (II. Kings, XIV:14; almost the same in II. Chronicles, XXV: 24). Unfortunately, only part of the New Testament from the fourth-century Gothic text of the Bible has come down to us, and we do not know the Gothic cognate of Old Norse gísl. Yet perhaps an almost contemporaneous Germanic word occurs on a runestone, dated approximately to the year 400, though the meaning of the noun –gislas on that stone is debatable. In any case, the Gothic word must have been close to those we know from Old English, German, and Icelandic, because the second part (-gīs) in the Gothic name Andagis meant the same as Gís– in Gísli. From Homer to Gísli people were called “hostage.”

A scene from Gisla saga.

A scene from Gisla saga.Image from Gisli the Outlaw, by George W. Dasent via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

The word continued its travels. Though seemingly borrowed by the Germanic-speaking world from the Celts, it was picked up by their other neighbors, the Finns, with the predictable sense “pledge.” Such is Finnish kihla “community; engagement to be married” (remember Gisela!), a reliable loan from Germanic. By contrast, English lost gīs(e)l. In the thirteenth century, it was supplanted by French (h)ostage (the Modern French form is otage). Hostage looks deceptively simple. Is it not host– plus the suffix –age? Perhaps, though at first glance, such a sum makes little sense. According to a reconstruction offered long ago and repeated dogmatically in many modern dictionaries, the word’s original base was obsidatus (from the still earlier obsidaticus) “condition of being made a hostage,” with h- added under the influence of hostis “enemy” (compare English hostile). In obsidatus, we recognize Latin obses (the genitive: obsedis) “hostage,” from ob “in front of” and sedēre “to sit.”

Though, as noted, this reconstruction can be found in many dictionaries, Old French (h)ostage meant “dwelling,” a sense hardly expected from “hostage.” French hôte “host; guest” looks more compatible with the idea of an unwilling guest. In Latin, hostis “stranger, enemy” and hospes “enemy” sounded similar. This is not surprising. “Guest,” “stranger,” and “enemy” form a knot, which is hard to disentangle. The English word guest is certainly related to hostis, and think of the pair host and hostile! Therefore, some language historians gave up the sensible but bulky obsidaticus and derived hostage from host. Neither etymology looks fully convincing, but the simpler one may be more acceptable. Such then is the shortest history of the European words for “hostage.” Hostage, it will be remembered, is my word of the year. Years are long, and weeks are short. In a few days, I’ll be out of town, at a medieval conference (speaking predictably about etymology). Therefore, you will hear from me only on May 22. Kindly fill the interim with questions and comments.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers