Oxford University Press's Blog, page 22

July 22, 2024

Bounded rationality: Being rational while also being human

Bounded rationality: Being rational while also being human

The middle of the twentieth century was an optimistic time in the study of human rationality. The newly rigorized science of economics proposed a unified decision-theoretic story of how humans ought to think and act and how humans actually think and act. For the first time, we had good scientific evidence that humans were by-and-large rational creatures.

In the 1970s-1980s, the story changed. A new wave of social scientists, led by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, proposed that humans decide how to think and act by using a simple toolbox of heuristic strategies. Heuristics are fast, frugal, and reasonably reliable, but they also have biases: systematic ways in which their outputs come apart from the requirements of leading decision-theoretic ideals. For example, we might judge that Linda is more likely to be a feminist bank teller than a bank teller, though that is clearly impossible, since all feminist bank tellers are bank tellers. Soon, hundreds of systematic biases in human cognition had been discovered and cataloged. As a result, many scholars came to believe that humans are not very rational after all.

In the past few decades, a new wave of scholars have urged that the 1970s and 1980s were too harsh in their judgment of humanity. Humans are, it is increasingly held, indeed fairly rational creatures. But this is not because we always do what mid-century decision theory says we should. It is instead because mid-century decision theory did not tell the full story about what it means to be rational, while also being human. Recent work has urged that traditional decision-theoretic standards of rationality leave out a number of relevant factors that rational humans should and do respond to, then wrongly treat humans as irrational when in fact we are responding correctly to factors that decision-theoretic standards have traditionally neglected.

In particular, theories of bounded rationality urge that humans are bounded agents. We are bounded by our internal structure, as agents with limited cognitive abilities and who must pay costs to exercise those abilities. We are also bounded by our external environment, which shapes the problems we are likely to face and the consequences that our actions will have on the world. Theories of bounded rationality aim to show how factors such as limited cognitive abilities, cognitive costs, and the structure of the environment shape how it is rational for humans to think and act. Bounded rationality theorists propose that what looks like irrationally biased cognition is often a rational response to cognitive and environmental bounds.

For example, suppose I ask you to estimate the date on which George Washington was first elected president of the United States. If you are like many people, you will answer this question by beginning with a relevant anchor value, such as 1776, the year in which the Declaration of Independence was signed. You will adjust your estimate upwards a few times to account for the length of the Revolutionary War and the interval between the Revolutionary War and the election of the first president. You may also adjust downwards to account for factors such as the need to quickly form a stable government. If you are like many people, you will arrive at an estimate in the low- or mid-1780s.

This process is called anchoring and adjustment: judgments begin by taking a relevant fact as an anchoring value, then iteratively adjusting the estimate upwards or downwards from the anchor to incorporate new items of information. In this case, anchoring and adjustment performs remarkably well: Washington was first elected in 1788. But anchoring and adjustment shows an anchoring bias: estimates tend to be skewed towards the anchor. In this case, they tend to be several years too low, because the anchor value of 1776 is lower than the true value of 1788. Classic theories of rationality would treat this as an irrational type of cognitive bias, but bounded rationality theorists are not so sure.

Anchoring bias happens because agents do not make enough adjustments to wash out the effect of the initial anchor. There is strong evidence that this happens because adjustments are effortful: we could, if we wished, wash out the anchor by making thousands of tiny adjustments, but this may not be worth the effort. That is, we face an accuracy-effort tradeoff between increased accuracy and increased effort from each additional adjustment. Bounded rationality theorists propose that in cases such as the above, humans make an optimal compromise between competing goals such as accuracy and effort. In this case, we choose a number of adjustments sufficient to yield a highly accurate estimate while keeping the number of effortful adjustments low. In this way, what looks like an irrational cognitive bias may actually be a rational response to our bounded human condition.

Not all human cognition is rational. For example, there is not much to be said for someone who prefers to draw from an urn containing 7/100 prizes instead of an urn containing 3/10 prizes, on the basis that 7 is larger than 3. But careful theorizing about bounded rationality aims to show that many cases which look as biased and irrational as this urn draw are in fact fully rational when viewed in the proper light.

Featured image by Sasha Freemind via Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

A listener’s guide to Music in Medieval Rituals for the End of Life [playlist]

A listener’s guide to Music in Medieval Rituals for the End of Life [playlist]

The music has been hidden—unseen and unheard—for centuries. Listen to the playlist and hear a historic soundscape unfold—songs of compassion and hope, created to accompany the final breaths of life.

Music in Medieval Rituals for the End of Life took seven years—searching through medieval manuscripts, transcribing their music notation, and writing the book. As a musician who has attended to loved ones during their final breaths of life, I was determined to recover the historic music created for those awful and awe-filled moments.

But even as I researched and wrote, I knew that the book was only the beginning. The music was never meant to be confined to the written page.

Singers from the University of Notre Dame now offer the first recordings, completed in the campus’s historic Log Chapel. A soundscape from a distant time unfolds while listening to these chants. Transcribed from manuscripts dating from the twelfth to the fifteenth centuries, the chants acknowledge the suffering and pain that accompany death. But they also sing of a soul in motion—a soul journeying towards a loving creator and a place of hope and welcome. The following playlist highlights a selection of these chants, intended to accompany the final minutes of life, the last breath, and the time immediately following death:

Track 2.2 Suscipiat te Christus: When Israel was released…The final minutes of life provided the time to tell the story of the Exodus—the Hebrew Bible narrative relating the Israelites’ escape from slavery. The experience of the Hebrew people was understood to parallel the experience of death. Just as the community of Israel escaped from captivity, so the soul escaped from the hard constraints of earthly life into heavenly freedom.

In the chant, the story of the Hebrew people (Psalm 113) is framed with a traditional Christian blessing:

May Christ receive you, who created you, and to the bosom of Abraham may angels lead you.

The Christian blessing and the Jewish narrative together form a single expression of reassurance and hope.

Track 1.8 Redemisti me: Into your hands…This chant brings the dying person into the center of the Christian story. The last words Jesus spoke (following the gospel of Luke) were sung on the dying person’s behalf:

Into your hands, Lord, I commend my spirit

The chant mimics the movement depicted in the text. With the words “into your hands” (in manus tuas), the melody leaps up, musically echoing the spirit’s leap—from the human body to divine hands.

Track 4.1 Subvenite: Advance, saints of God…The women of Aldgate formed a close community, and when one of their sisters was dying, they surrounded her with song. This chant was sung during the final breath of life. As it unfolded, it gently moved the sisters through the loss.

The chant begins by calling for help from angels and saints:

Come now and take this soul. Bring it to the Most High One.

It continues by offering a final blessing to the departing loved one:

May Christ receive you; may angels lead you.

It concludes with a final prayer, asking for peace:

Give them eternal rest, Lord.

Track 4.2 Kyrie, all voices: Have mercy…When the final breath of their sister had passed, the women of Aldgate stood surrounding her. In a time of quiet prayer, before her body was cleansed and dressed for burial, they sang this chant:

Lord, have mercy

Christ, have mercy

Lord, have mercy

The simple words were familiar from their religious services; the graceful melody followed familiar patterns of breathing. Listen to the first words. The music gently rises and falls as the singers pass the melody back and forth. The final lines expand. As the opening melody mimics a gentle breathing pattern, the melody with the final words breathes more deeply.

The sister’s breath had stopped, but the community’s song continued, making their breath audible as sound.

Track 1.1 Dirige domine: Direct my ways…The singing continued as the body was moved.

The elite, educated practitioners of Saint Peter’s Basilica at the Vatican sang as they carried the body from the place of death to the church:

Direct my ways, Lord, my God

Let me walk in Your sight.

Did they sing in the voice of the one who had just died, whose soul was moving into the afterlife? Or was this a prayer for themselves, the ones who continued to move through the difficulties of earthly existence? Possibly both.

The medieval rituals blur the line between the living and the dead. Each person’s fate was the same; the need for help was the same: only time separated the living and the deceased.

Listen as the chant voices the words in conspectu tuo (“in your sight”). The melody ascends confidently, offering a reassuring musical image—God’s sight is broad and expansive, taking in any path a human might travel.

***

I am deeply grateful to the University of Notre Dame for making the entire playlist freely available.

Featured image by Chris Linnett via Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

July 17, 2024

Words, emotions, and the story of great

Words, emotions, and the story of great

Last week (July 10, 2024), I promised to deal with the word great and will do so, but two comments on that post reinforced my old wish to deal with the topic indicated in the title of today’s essay. Those who have read the entire series may remember my light-hearted remarks on English leetle and its Gothic cognate (a word with an equally puzzling long vowel) and another facetious remark on the history of a in Latin magnus (one expects short i in its root). I wrote that since magnus means “big,” the meaning might inspire people to open their mouths wide. None of such ideas can be “proved,” and counterexamples are easy to find. For instance, big, obviously, has a “wrong” (closed) vowel: bag and even bug would fit its sense better. Yet sound-symbolic tendencies are real, even if erratic. See the header for images of a man learning, as I suspect, to pronounce Latin magnus.

It is always pleasant to wander and even err in good company. Years of studying sound-symbolism have made me aware of many words whose form cannot be accounted for in any other rational way (just symbolism!). I am also an old admirer of Wilhelm Horn (1876-1952). His contributions to English studies are outstanding, and it is a shame that the Internet has almost nothing to say about him. Horn spent years working on a book that was published after his death under the title Laut und Leben (“Sound and Life”). It appeared in 1954 thanks to the efforts of his former colleague Professor Martin Lehnert, who had a position of authority in the GDR and could hire enough assistants to help him in going through Horn’s manuscript and providing an inestimable word index. Laut und Leben is a woefully neglected book.

Is Broadway wide?

Is Broadway wide?Image by Vlad Alexandru Popa via Pexels.

Horn believed that when it comes to historical phonetics, numerous exceptions from the otherwise safe laws owe their origin to words pronounced on a high note, that is, with emphasis. In his dedication to a high note, he often went too far. Yet the material he amassed is worthy of our closest attention. One of his star witnesses was the word broad. If we compare broad with goad, load, road, and other words with oa (the likes of goat, oaf, and soak also belong here), we will see that all of them have the vowel of no, while broad does not rhyme with road, goad, load! It rhymes with hoard, sword, and sward! I’ll later return very briefly to the etymology of broad, but at the moment, the Old English form will suffice: it was brād (ā, a long vowel, had the value of a in Modern English spa). This ā became ō (the vowel of today’s awe) and still later the diphthong, which we now have.

Broadly speaking, how wide awake is this baby?

Broadly speaking, how wide awake is this baby?Image by Avsar Aras via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 4.0.

Why did broad avoid the trend? No one knows! But if we suggest that a word like broad might often be pronounced in a particularly emotional way (“on a high note”), we may not be too far from the truth. Affectation, simpering, deliberate imitation of baby talk, drooling over some happy event, and similar processes certainly change the way words sound. Broad has no secure cognates outside Germanic. Wide is the common word for the concept, though, strictly speaking, wide and broad are not synonyms. Who coined Old English brād and under what circumstances? Should I again repeat: “No one knows”?

Curiously, the etymology of break, another br-word, is also unclear. And the same holds for its br– synonym, whose only remnant in today’s English is the adjective brittle. Were both sound-imitative words, with their formidable br-? Despite its etymological obscurity, English break has cognates all over most of the Germanic-speaking world and beyond. The obviously related Latin frangere (we can detect its root in English fragile and fraction) again has a instead of e in the root! And the development of the English verb is also erratic. Today’s form should have rhymed with speak from Old English specan, rather than with make, from Old English macian. Horn suggested that break is an emotional form, without going into detail, and of course, what else could he say? I’ll skip his other examples and only add that wide has no secure etymology either. (“No secure etymology” means that no ancient root with a clear form has been reconstructed.)

The time has now come to look at great. At first sight, its origin seems to be rather clear, but dictionaries hedge and prefer to remain noncommittal. Of course, the spelling, or rather the pronunciation, of great is also problematic. Beat, seat, and feat don’t rhyme with it: only steak, with its erratic ea in the middle, does. But as I said (everybody around me says like I said, but I’ll stick to my variant), it is the origin of great that interests us at the moment. Despite all the uncertainty, some careful word historians half-heartedly suggest that great (no change of spelling since the Old English period: great, or with the length sign added, grēat) has the root of such words as grout (its oldest sense was “coarse meal”). If so, the semantic development was from “coarse” to “big.”

The original OED devoted an unusually long discussion to the word’s origin. The problems are several. The same adjective existed everywhere in Old West Germanic (which means that it is indeed old), but not in Scandinavian. Today’s German has groß. Dutch groot is well-known from the family name Groot ~ De Groot and groat “a small coin” (German Groschen means the same: such coins were once called “thick pennies”). Though grautr “porridge” did exist in Old Icelandic (English groats, grout, and of course, grits are close by), no adjective like great developed in it.

A grandee of unknown origin.

A grandee of unknown origin.The Nobleman with his Hand on his Chest by El Greco, Web Gallery of Art via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

The way from “coarse,” that is, “hard-grained,” to “sizable” is not unthinkable. Yet the word’s triumph (it ousted micel) arouses surprise. Then we stumble at gross (some of its senses were also “dense; thick; coarse”), a borrowing from French, where it is native (!), and again discover that the word’s origin is unknown. Grand is from Latin grandis, another upstart: it superseded magnus. Etymologists agree that grandis was “a vulgar word,” that is, a word used by the Roman plebs. An additional detail will more amuse than embarrass us: its a in the root has never been accounted for. Of course, we notice that great, gross, and grand—all three unrelated adjectives—begin with gr.

In today’s (American) English, great has become the smallest conversational coin, a true groat. “Have a great day!” “How was it? It was great” (that is, awesome). “I am ready. Great, let us go!” What a bizarre journey: from “hard-grained” to “magnificent,” and finally, to a vacuous formula, full of sound and fury and signifying nothing.

No end of trouble with emotional words.

Featured image by Tima Miroshnichenko via Pexels.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

How to choose the right journal

How to choose the right journal

With approximately 30,000 academic journals worldwide, how do you determine which one is the best fit for your research? There are likely to be many suitable journals in your field, but targeting the right journal is an important decision, as where you choose to publish can influence the impact and visibility of your work.

As a first step, consider: what is your publishing goal?Defining your goal helps you identify which journals are best suited to achieve your aims. Authors publish for various personal and professional reasons, so consider what’s important for your career, professional development, or research program. Some potential goals could include:

Advancing knowledge in your specialist field, and contributing to the development of research or debate, so that others can build upon your ideas or resultsDisseminating your findings to a wide or interdisciplinary audience, or having an impact beyond academiaAdhering to your funder or institutional requirementsSupporting a learned society or organisation in your subject areaUsing a particular article type or media format to convey your findingsSecondly, what is important to you in the publishing process?As with goals, this is often personal. This could be:

Publishing quicklyA particular type of peer review processAn easy or straightforward submissions processThe option to transfer rejected papers to related journalsAssistance with editingNext, make a shortlist of journals to compareLook for journals that publish on your topic. It can be helpful to ask colleagues and mentors for their recommendations, and you can also consider which journals you regularly read or cite yourself. Once you have your shortlist, you can start to check which meet your criteria and more easily rank your options.

Things to compare and considerManuscript suitability – scope and topicDoes the journal publish your article type and research topic? Seth Schwartz recommends browsing a recent issue of the journal to determine whether any of the articles are similar in scope or type to the paper you are planning to write. Checking the editorial board can also help you to assess the subjects and topics the journal focuses on, and the journal’s aims and scope information or current call for papers will indicate the breadth and depth of the topics covered and whether your article would be a good fit.

Considering the impact and reachThere are a variety of metrics available, including Journal Impact Factor and Altmetrics. Some apply at the journal level and some at the article level. It’s important to pay attention to the metrics that best reflect your publishing goal. For example, if you want your research to be widely read, Altmetrics can help you track the impact on specific areas like policy documents or conversations on social media.

When weighing up journal reputation and metrics, Schartz suggests selecting a journal that matches the significance of your research findings or theory. We can think in terms of “three general levels of contribution—major, moderate, and incremental. Matching the contribution of your work with the prestige level of your target journals may maximize your chances of receiving an invitation to revise and resubmit your paper, and hopefully an eventual acceptance for publication.”

Readership and audienceA 2019 bioRxiv survey found that academics prioritize a journal’s readership when choosing where to publish. You should check journal websites for readership stats and reflect on your own publishing goals: for a specific audience, ask colleagues about their go-to journals; for broader reach, look for journals with a global audience and strong social media presence.

Abstracting and indexing databases also play a significant role in how discoverable your article is, and therefore how many people will find and read it. Well-known databases include Scopus, PubMed, Web of Science, and Google Scholar, but there are also many subject-specific databases.

Ethics and PoliciesIn recent years there has been an increase in deceptive or “predatory” journals. Niki Wilson describes that while the individual practices can vary, these journals “generally prioritize self-interest and profit over research integrity… and often take fees without performing advertised services”. Before submitting your paper, it is important to take a close look at its website and review its policies, the expertise of the editorial board, and peer review processes—a reputable journal will disclose all this information publicly. It is also a good idea to check if the journal is a member of COPE, or if they ensure that they practice high standards of publication ethics. The free Think.Check.Submit service can help to steer you towards quality and trusted journals.

Peer reviewA reputable journal will practice rigorous peer review, and there are various peer review models are available to journals, each with different merits. Peer review helps to guarantee the publication of high-quality research, by assessing the validity, significance, and originality of research. Peer review also benefits you as the author, as it helps to improve the quality of your manuscript and detects errors before publication. In our surveys of OUP authors, the quality of peer review is consistently among the top three factors authors prioritise when choosing a journal.

A good journal will explain its peer review process, and details will normally be available on the ‘instruction to authors’ page. At OUP, we refer all editors to the COPE Ethical Guidelines for peer reviewers, which encourages journals to publish their review procedures.

Author experienceYour experience as an author will vary widely by journal, publisher, and subject area. Many journals are improving processes to make publishing smoother and faster, with format-free submissions, efficient submission systems, quick decisions, strong editorial support, and awards. Consider which options align with your priorities and seek feedback on recent experiences from your network.

Publication models and complying with funder policies

There are multiple publication models to choose from, including fully open access (often known as gold OA), hybrid publishing, and self-archiving (often known as green OA). A growing number of funding agencies and institutions stipulate the publishing license that their academics must use, so familiarise yourself with any limitations or restrictions you need to adhere to and check the journals on your shortlist comply. Ensure you understand (and are able to meet) the publication charges, or see if your institution has a Read and Publish agreement.

ConclusionCheck your shortlist of journals against your criteria and the points above. If you are unsure and need additional information about a journal, consider contacting the journal editors or editorial office for clarification. Remember, do not submit your article to more than one journal at a time. If discovered, this will normally result in the automatic rejection of your manuscript.

If you are ready to publish your findings, take a look at our extensive list of high-quality academic journals or delve into our journal author information page for more insight into our publishing process.

Featured image by Anne Nygård via Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

July 16, 2024

Israel, Palestine, and reflections on the post-9/11 War on Terror

Israel, Palestine, and reflections on the post-9/11 War on Terror

How can the United States best help Israel defend itself against terrorist atrocity? Obviously, sustaining the alliance and friendship with the United States is vital for Israel and its security. Equally clearly, the scale and nature of Israeli violence in Gaza since October 2023 has placed new and great strain on the US relationship. This has famously been reflected in university campus protests across the States, including those at major universities. But this strained relationship has also been repeatedly evident in the tensions between US political preferences and the current Israeli government’s stubborn adherence to its Gaza policy.

One of the repeated problems with state counter-terrorism is a tendency towards short-termism. The understandable pressure to do something after a terrorist atrocity, and to do it now, can get in the way of wise policies based on past experience. Short-termism also ignores the long-term future dangers that are generated by impulsive contemporary actions.

The United States’s long and sometimes painful experience of its post-9/11 War on Terror offers potential insights to help shape its ally’s response to Hamas terrorism. Hamas’s horrific 7 October attack, like al-Qaida’s appalling assault on the United States in September 2001, prompted the demand for something unprecedented and decisive to be done. So much can now be known about what went well and what went badly in the post-9/11 War on Terror as it evolved. Given this retrospect, we can start to analyse the limitations and errors in Israel’s approach towards Palestine, in light of previous US actions.

Allow me to briefly suggest four undermining factors of the US’s counter-terrorist approach:

1. The exaggeration of what can be done through military meansMuch that went badly in the US-led War on Terror involved an exaggeration of what could be done through military means. This has been a common error in the long history of counter-terrorism elsewhere too: from the French in Algeria, to the UK in Ireland in the 1920s and in Northern Ireland in the 1970s, and beyond. While the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 was justifiable in relation to al-Qaida and their Taliban hosts, the Iraq War was—in relation to counter-terrorism—a disastrous military venture. Terrorism increased as a result of the invasion and its aftermath, rather than diminishing.

In Israel/Palestine too, both Hamas and the current Israeli government exaggerate what their own violence will achieve. For Israel’s part, military methods simply will not eradicate Palestinian resistance and Hamas terrorism in the ways that are being proclaimed by some politicians.

2. The pursuit of unrealistic goalsA second insight from the War on Terror is the need to set realistic goals and then to pursue them consistently. Much of what proved problematic in Afghanistan, Iraq, and the wider War on Terror had its roots in a mixture of unrealistic ambitions and an unhelpful vacillation between priorities. The envisioned transformations of Afghan and Iraqi society were implausible, not least since their only chance of success would have required a US commitment to massive engagement over a period far longer than was ever likely to be possible. More limited goals (damaging al-Qaida, displacing the Taliban, but not embarking on nation-building transformation) would probably have been more sensible.

Regrettably, part of the adoption of a realistic approach to counter-terrorism involves learning to live with and contain terrorist violence rather than pledging to eradicate it (certainly within any short timeframe). Israeli government mistakes here are clear, and are likely to prove counter-productive. There seems no likelihood of completely removing Hamas terrorism against Israel. But there does exist the possibility of limiting it so that life can proceed in far safer and more normal ways than has become the case for Israeli citizens in recent years. A combination of efficient counter-terrorist tactics with the avoidance of strategic over-reaction is likely the best approach.

3. The mistaking of the terrorist symptom for the wider issuesCounter-terrorism is made more difficult if one mistakes the terrorist symptom for the more profound issues at stake. In the War on Terror, it was less accurate to suggest that al-Qaida hated the United States for its freedoms, than to suggest that it hated the US for its foreign policy. Misdiagnosis of cause does little to help those trying to remedy the problem so produced. In Israel, understandable rage at entirely unjustified Hamas atrocities such as 7 October should not blind anyone to the reality that terrorism in Israel/Palestine emerges from a clash of religiously fuelled rival nationalisms; and from an agonizing conflict over state legitimacy and the autonomy of national peoples.

This does not mean there are any easy answers or simple political solutions. But the ignoring or misdiagnosis of the root causes behind terrorism have tended in the past to prove counter-productive.

4. The public opinion that too many civilians have been avoidably killedCounter-terrorism has tended to undermine itself where public and international opinion judges too many civilians to have been avoidably killed and injured in the process. In the War on Terror, civilian deaths at the hands of the United States and its allies (whether in Afghanistan, Iraq, or elsewhere) helped terrorist enemies gain sympathy and damaged the War on Terror in terms of credibility and support. The implications here for Israel and Gaza could hardly be clearer. Extensive violence against civilians—however unintended—is likely to undermine the counter-terrorist effort.

Israel’s most important global ally needs to ensure that the mistakes of the War on Terror encourage the adoption of a more proportionate and politically strategic counter-terrorism. Without this, Israel and the wider Middle East will likely experience exacerbated conflict and bloodshed.

Featured image: ©Getmilitaryphotos/Shutterstock.com

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

Artificial Intelligence? I think not!

Artificial Intelligence? I think not!

“The machine demands that Man assume its image; but man, created to the image and likeness of God, cannot become such an image, for to do so would be equivalent to his extermination”

(Nicolai Berdyaev, “Man and Machine” 1934)

These days, the first thing people discuss when the question of technology comes up is AI. Equally predictable is that conversations about AI often focus on the “rise of the machines,” that is, on how computers might become sentient, or at least possess an intelligence that will outthink, outlearn, and thus ultimately outlast humanity.

Some computer scientists deny the very possibility of so-called Artificial General Intelligence (AGI). They argue that Artificial Narrow Intelligence (ANI) is alone achievable. ANI focusses on accomplishing specific tasks set by the human programmer, and on executing well-defined tasks within changing environments, and thus rejects any claim to actual independent or human-like intelligence. Self-driving cars, for example, rely on ANI.

Yet as AI researcher and historian Nils J. Nilsson makes clear, the real ‘prize’ for AI researchers is to develop artifacts that can do most of the things that humans can do—specifically those things thought to require ‘intelligence.’” Thus the real impetus of AI research remains AGI, or what some now call “Human Level Artificial Intelligence (HLAI).

The central problem with such discussions about AI, however, is the simple fact that Artificial Intelligence does not exist.

To achieve this goal, AI researchers attempt to replicate the human brain on digital platforms, so that computers will mimic its functions. With increasing computational power, it will then be possible first to build machines that have the object-recognition, language capabilities, manual dexterity, and social understanding of small children, and then, second, to achieve adult levels of intelligence through machine learning. Once such intelligence is achieved, many fear the nightmare scenario of 2001: A Space Odyssey’s self-preserving computer HAL 9000, who eliminates human beings because of their inefficiency. What if these putative superintelligent machines disdain humans for their much inferior intellect and enslave or even eliminate them? This vision has been put forward by the likes of Max Tegmark (not to mention the posthuman sensationalist Yuval Harari), and has enlivened the mushrooming discipline of machine ethics, which is dedicated to exploring how humans will deal with sentient machines, how we will integrate them into the human economy, and so on. Machine ethics researchers ask questions like: “Will HLAI machines have rights, own property, and thus acquire legal powers? Will they have emotions, create art, or write literature and thus need copyrights?”

The central problem with such discussions about AI, however, is the simple fact that Artificial Intelligence does not exist. There is an essential misunderstanding of human intelligence that undergirds all of these concerns and questions—a misunderstanding not of degree but of kind, for no machine is or ever will be “intelligent.”

Before the advent of modernity, human intelligence and understanding (deriving from the Latin intellectus, itself rooted in the ancient Greek concepts of nous and logos) indicated the human mind’s participation in an invisible spiritual order which permeated reality. Tellingly, the Greek term logos denotes law, an ordering principle and also language or discourse. Originally, human intelligence did not imply mere logic, or mathematical calculus, but the kind of wisdom that comes only from the experiential knowledge of embodied spirits. Human beings, as premodern philosophers insisted, are ensouled or living organisms, or animals, that also possess the distinguishing gift of logos. Logos, translated as ratio or reason, is the capacity for objectifying, self-reflexive thought.

Moreover, as rooted in a universal logos, human intelligence was intrinsically connected to language. In this pre-modern world, symbols are not arbitrary cyphers assigned to things, as AI researchers have always assumed; rather, language derives from and remains inseparably linked to the human experience of a meaningful world. As the German philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer explains, “we are always already at home in language, just as much as we are in the world.” We live, think, move, and have our being in language. As the very matrix that renders the world intelligible to us, language is not merely an instrument by which a detached mind masters the world. Instead, we only think and speak on the basis of the linguistic traditions that make human experience intelligible. And let’s not forget that human experience is embodied.

The only way we can even conceive of computers attaining human understanding is a radical redefinition of this term in functionalist terms.

No wonder, then, that human understanding, to use the English equivalent of the Latinate ‘intellect,’ has a far deeper meaning than what computer scientists usually attribute to the term. Intelligence is not shuffling around symbols, recognizing patterns, or conveying bytes of information. Rather, human intelligence refers to the intuitive grasp of meaningful relations within the world, an activity that relies on embodied experience and language-dependent thought. The critic of AI, Hubert Dreyfus summed up this meaning of intelligence as “knowing one’s way around in the world.” Algorithms, however, have no body, have no world, and therefore have no intelligence or understanding.

The only way we can even conceive of computers attaining human understanding is a radical redefinition of this term in functionalist terms. As Erik Larson has shown, we owe this redefinition in part to Alan Turing, who, after initial hesitations, reduced intelligence to mathematical problem solving. Turing and AI researcher after him thus aided a fundamental mechanization of nature and human nature. We first turn reality into a gigantic biological-material mechanism, then reconceive human persons as complex machines powered by a computer-like brain, and thus find it relatively easy to envision machines with human intelligence. In short, we dehumanize the person in order to humanize the machine. We have in fact, as Berdyaev prophesied, exterminated the human in order to create machines in the image of our de-spirited, mechanized corpses.

In sum, our problem for a proper assessment of so-called AI is not an imminent threat of actual machine intelligence, but our misguided imagination that wrongly invests computing processes with a human quality like intelligence. Not the machines, but we are to blame for this. Algorithms are code, and the increasing speed and complexity of computation certainly harbors potential dangers. But these dangers arise from neither sentience nor intelligence. To attribute human thought or understanding to computational programs is simply a category mistake. Increasing computational power makes no difference. No amount of computing power can jump the ontological barrier from computational code to intelligence. Machines cannot be intelligent, have no language, won’t “learn” in a human educational sense, and they don’t think.

As computer scientist Jaron Lanier pithily sums up the reality of AI: “there is no A.I.” The computing industry should return to the common sense of those AI researchers who initially disliked the label AI and called their work “complex information processing.” As Berdyaev reminds us with the epigram above, the true danger of AI is not that machines might become like us, but that we might become like machines and thereby forfeit our true birthright.

Featured image by Geralt (Gerd Altmann) from Pixabay.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

July 14, 2024

Can a word have an existential crisis?

Can a word have an existential crisis?

A while back, a philosopher friend of mine was fretting about the adjective “existential.” She was irked by people using it to refer to situations which threaten the existence of something, as when someone refers to climate change as an “existential crisis,” or more commonly, as “an existential threat.”

Is the meaning of “existential” being corrupted?

Dictionaries give the meaning as “of, relating to, or affirming existence” and “grounded in existence or the experience of existence,” neither of which is much help. I do think “existential” has become a bit of a buzzword, but I’m not worried about its meaning.

Historically, an “existential crisis” has referred to philosophical or psychological questions of purpose, identity, and the meaning of life; and to the periods of anxiety that such questions produce. And indeed, this seems to be the way the phrase is used in serious journalism, at least in headlines like these from the New York Times:

Iowa Faces an Existential CrisisDamar Hamlin and the Existential Crisis of ‘Monday Night Football’Baseball’s Existential CrisisThe G.O.P.’s Existential CrisisCure for the Existential Crisis of Married MotherhoodAn Existential Crisis for Law SchoolsNo one expects the state of Iowa to cease to exist (perhaps becoming East Dakota). The same goes for Monday Night Football, Baseball, the G.O.P., married motherhood, or law school. The headlines refer to identity crises, not threats to existence (well, maybe for the G.O.P.). The shift of “existential crisis” from referring to a personal identity crisis to a cultural one is nothing to fret about.

Folks who use “existential crisis” only in its human “identity crisis” meaning may not like the way it is extended in these headlines, but what really annoys them is the phrase being used to indicate something is a threat to humanity. This use is becoming increasingly common, as for example, when President Joe Biden called climate change “a global, existential crisis.” Is it a crisis of the earth’s identity or a crisis of human existence? It could be both I suppose, which may be how the extended meaning comes about.

The naturalness of the semantic shift may not satisfy my philosopher friend or other critics. Feeling that you have a special interest in technical terms is only human. As a linguist, I would occasionally snark when people used the term “deep structure” to refer to some hidden meaning in a phrase. For linguists of a certain generation, its technical use referred to a particular level of analysis (the output of the phrase structure component). The expression has shifted enough so that linguists now talk about d-structure, omitting the “deep.”

Some of my literature colleagues used to worry about the casual use of “deconstruction” to mean “analysis” or “taking things apart” (though, in fact, that meaning preceded its literary use). Just about everyone in the sciences gets upset at the use of “theory” to refer to “hunch” rather than to a precisely formulated and tested body of principles offered to explain phenomena about the world. And philosophers are no doubt put out when non-philosopher friends talk about their “philosophy of life.”

My philosophy, so to speak, is to appreciate these shifts but not get too upset about them. Words and phrases, it turns out, have their own existential crises—and they come out of them with new meanings.

Featured image by Anne Nygård via Unsplash

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

July 12, 2024

Ethnographic data-sharing as community building

Ethnographic data-sharing as community building

The open science movement has fundamentally changed how we do and evaluate research. In theory, almost everyone agrees that open research is a good thing. In reality, most researchers struggle to put theory into practice. None more so than ethnographers. Instead of rejecting data sharing, ethnographers are uniquely positioned to contribute positively to open research by decentering data and recentering context, community, and lived experience.

Data sharing principles are hard to implementData sharing following “FAIR Principles” has widely come to be seen as best practice in research. Data should be findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable. However, implementation of the FAIR Principles has proven challenging. Even in STEM disciplines working with quantitative data, “data sharing is still mostly an ideal, honored more in the breach than in practice.” This is due to the fact that there is a gap between the ideal of data sharing and research workflows characterized by time pressures and the imperative to compete for scarce resources.

Implementation barriers particularly affect early career researchers. As a group, they have low awareness of open research, have no space for the additional time commitments needed to create open data, and often face restrictions from supervisors and more senior colleagues.

Protecting the anonymity of participants in shared dataDespite these implementation challenges, funding bodies are increasingly mandating open data. Such mandates create specific challenges for humanities and social sciences scholars working with qualitative data.

Questions of privacy usually spring to mind first: ethnographers wonder how they can protect the anonymity of their participants under an open data regime. On the face of it, this problem seems to have an easy solution. Putting specific user restrictions for a specific dataset in place is not technically difficult. Most data repositories allow a variety of privacy settings from fully open to highly sensitive.

Yet this seemingly straightforward technical solution clashes with how research participants may feel about their research participation. Everyone knows that data breaches are extremely common. Therefore, even the possibility of data being made available beyond the confines of the research team—regardless of what the privacy settings of the repository might be—will mean that some participants think twice about participation. This is particularly true of vulnerable groups, whose experiences will be further marginalized in the scientific record.

Maintaining the richness of ethnographic dataFurthermore, for ethnographers, “data” are created in interaction between researcher and participant. Researcher positionality is central to humanities and social sciences research.

All research is partial and the product of specific relationships between people. Yet, to be sharable we need to transform our observations, interactions, conversations, and relationships into “data.”

Conversations, for example, become audio-recordings and transcripts, erasing the material context of the conversation: the embodied researcher and their relationship with participants. Some of this will be captured in field notes, which constitute another data point. However, practically, we cannot even begin to imagine how much work polishing our field notes to prepare them for data sharing in a repository would entail. Our field notes are built on our “having been there” and usually consist of half sentences, in a mix of languages, full of abbreviations and cross-references meaningful only to ourselves.

Open data as fodder for generative AIWe like to think of open data as “best practice” enabling scientific rigor, transparency, and ultimately enhancing human knowledge. Yet, in reality, open data has become caught up in commercial data scraping and surveillance capitalism. We can no longer think of digital text only positively as “open” but must also exert caution as they provide the fodder for the large language models underlying generative AI. By putting our data out there in digital formats we may well add fuel to the fire of the textocalypse, “a crisis of never-ending spam, a debilitating amalgamation of human and machine authorship.”

Reimagining data sharingThe ambition of open research – for research to extend its benefits as widely as possible – is close to the heart of most researchers. After all, the privilege of knowledge creation carries with it the responsibility of knowledge sharing.

How can we reap the benefits of data sharing without letting “the logic of open data distort ethnographic perspectives”?

Ethnographic data sharing cannot be depositing text in a repository, for the reasons outlined. To preserve the ontological and epistemological integrity of ethnographic research, data sharing must not only maintain the relationships established in the projects being brought together but extend and enhance them.

For the Life in a New Language project, we combined data from 130 participants across six separate ethnographic studies conducted over a period of 20 years to explore the lived experience of adult language learning and migrant settlement.

All six projects had been conducted within the larger Language on the Move research team and four of them were PhD projects supervised by the lead author. Sharing our data thus took place within an established personal relationship. We managed to bring the person of the researcher along with the data.

Reimagining data sharing as creating a research community of practice enabled us to create new knowledge related to our specific research problem, how adult migrants make a new life through the medium of a language they are still learning. Incidentally, we created a working model for how to combine existing small data sets into a larger longitudinal study of a social phenomenon within an open research framework and a collaborative ethics of care.

Featured image by Ester Marie Doysabas via Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

July 11, 2024

“But you got to have friends…”: A Bette Midler playlist

“But you got to have friends…”: A Bette Midler playlist

Bette Midler began her recording career back when Richard Nixon (“Tricky Dick,” as she liked to call him) was still President, and her range and versatility were obvious from the very beginning. Since she first entered a recording studio, she’s tackled just about every genre of music. This tour through her recorded output reveals not just the familiar best-selling hits but five decades of deep cuts and delightful discoveries. Take a listen for yourself:

1. “Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy” (1972)Midler’s affinity for 1940s music resulted in her first top ten hit: a period-perfect recasting of this Andrews Sisters’ World War II boogie woogie smash. Multi-track layering gave us Midler as Patty, Maxene, and LaVerne, all in perfect harmony.

If you like that, try this: “It’s the Girl” (2014): Decades on, Midler’s harmony chops were undiminished as she revisited this swinging 1930s hit by the Boswell Sisters, one of her childhood favorites.

2. “Do You Want to Dance?” (1972)This sultry, slowed-down version of the Bobby Freeman hit opened Midler’s debut album, The Divine Miss M—no album ever got off to a better start. Midler has never sounded more sensuous as she pleads for one more dance in an arrangement that remained a staple of her live concerts into the twenty-first century.

If you like that, try this: “Under the Boardwalk” (1988): Midler brought a similar sexy vibe to this remake of the 1960s Drifters’ hit for the soundtrack of Beaches.

3. “Friends” (1972)This jaunty sing-along ode to the importance of friendship became Midler’s unofficial theme song when she worked at the Continental Baths in the early 1970s and it’s been part of her act ever since. Its lyric, “I had some friends but they’re gone/Something came and took them away,” has meant different things at different stages of her career. In the 1970s it was a promise of solidarity with the gay men who made up her first audiences. During the AIDS epidemic, it acknowledged the unfathomable losses of the gay community. In later years, it marked the passage of time and the inevitable loss of aging friends.

If you like that, try this: “Samedi et Vendredi” (1976): Midler wrote lyrics to many of the songs she’s recorded over the years, and this captivating burst of witty wordplay and infectious rhythms is one of her best. Singing all the voices––and doing it entirely in French––Midler sounds like she’s gathered all her friends into one room and let them run wild.

4. “Hello in There” (1977)Midler the actress made a meal out of John Prine’s poignant ballad about an old couple facing the end of an uneventful life. On her 1977 Live at Last album, she prefaced the song with an outlandish monologue about a giant, bald-headed woman on the streets of New York wearing a fried egg on her head, turning the fried egg into a metaphor for the existential anxieties of our era. After that introduction, “Hello in There” was more heart-wrenching than ever.

If you like that, try this: “Waterfalls” (2014): Midler turned TLC’s rambling scenario about mothers’ inability to keep their sons safe from the horrors of street crime and AIDS into a stripped down, mournful ballad.

5. “I Shall Be Released” (1973)Midler claimed ownership of every song she ever sang. In the case of Bob Dylan’s classic lament for an incarcerated man, she turned it into a furious feminist cry. Barry Manilow’s piano arrangement slowly builds in intensity as it takes Midler from quiet resignation to righteous anger.

If you like that, try this: “Beast of Burden” (1983): Midler did a similar renovation of Keith Richards and Mick Jagger’s teasing riff aimed at a reluctant lover, redefining it as a woman’s demand for respect.

6. “Cradle Days” (1979)Possibly the greatest vocal Midler ever laid down. In this slow-burning soul shouter, she’s a modern-day Medea pleading with a departing husband to restore both their relationship and their shared children. Her singing is equal parts untamed and tightly disciplined, all of it cushioned in creamy backing vocals led by Luther Vandross. Sublime.

If you like that, try this: “Birds” (1977): Midler’s take on Neil Young’s gentle breakup song gives it a driving R&B edge and features fierce vocal back-up from the Harlettes.

7. “Stay With Me” (1979)Midler’s film debut as a tortured Janis Joplin-like star in The Rose gave her plenty of opportunities to rock. But her best moments demonstrated her (and Joplin’s) feel for combining rock and soul, as in this staggering plea to a lover as he heads out the door.

If you like that, try this: “When a Man Loves a Woman” (1979): The other great performance number from The Rose. Midler sings the old Percy Sledge ballad as a recognition of the difficulty a woman rock star can have finding love. For maximum impact, watch the performance clips of “Stay With Me” and “When a Man Loves a Woman” rather than only listening to the audio.

8. “Wind Beneath My Wings” (1988)Midler’s first and (so far) only #1 hit demonstrates her skill at stirring in a bit of vinegar to cut the sticky sweetness. She rides the song’s anthem-like waves, but never falls off into bathos. Even if you’re immune to its message, it’s hard not to be moved by Midler’s sincerity.

If you like that, try this: “Laughing Matters” (1998): This rueful call to keep a sense of humor in a world gone increasingly mad gets a ravishing orchestral backing for one of Midler’s most reassuring vocals.

9. “The Rose” (1979)Just about perfect. The hushed power of Midler’s voice captures the “endless aching need” so vividly evoked in Amanda McBroom’s evergreen hymn—a classic pairing of singer and song.

If you like that, try this: “Lullaby in Blue” (1998): Midler holds back on the emotion and her restraint makes this tender remembrance of a teenage pregnancy deeply affecting.

10. “(Your Love Keeps Lifting Me) Higher and Higher” (1973)Another great Barry Manilow arrangement, this one starts soft but gathers force as Midler and a stentorian choir take it to church. Just when you think she can’t go any higher––or wilder––she reaches even more frenzied heights.

If you like that, try this: “Bang, You’re Dead.” (1977): Midler was known to dabble in disco, and this propulsive Ashford and Simpson production is one of her best in that genre. It’s impossible to stand still when Midler’s scorching vocal rides that four-on-the-floor beat.

11. “Mele Kalikimaka” (2006)Midler frequently evoked her background growing up on the island of Hawaii, and this holiday song, based on the Hawaiian derivation of the phrase, “Merry Christmas,” is an affectionate tribute to her home state.

If you like that, try this: “In the Cool, Cool, Cool of the Evening” (2003): Midler at her good-humored best, swinging lightly through Johnny Mercer’s dense, savory lyrics.

Featured image by Rob Bogaerts / Anefo. via Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

July 10, 2024

More English words for size: the size increases…

More English words for size: the size increases…

First of all, many thanks to our two readers who sent me letters on sw-words and the linguistic environment of the adjective tiny. For some reason, the combination t-n suggests smallness or perhaps insignificance to speakers of many languages. Likewise, the initial group sw– occurs in numerous words in which it may have a symbolic value. I hope to return to them in the near future, but today I will go on with English words denoting size and will deal with some antonyms of small. In the two previous weeks, it was small, little (with its illegitimate variant leetle), wee, and tiny that kept us busy.

This is Emperor Magnus Maximus. No one can be bigger!

This is Emperor Magnus Maximus. No one can be bigger!Image by Classical Numismatic Group, LLC via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 2.5.

Many a mickle makes a muckle, right? See the header! It is in mickle, a Scottish adjective, that we find the Common Germanic word denoting something big. Big, as we will soon see, is rather enigmatic. Gothic, our constant point of departure, because it was recorded so early (in the fourth century, to be exact), had mikils: for all intents and purposes, the same word as mickle. Mikils has many respectable relatives (that is, cognates). The closest one is Greek mégas. We recognize its root in English megapolis and megalith (among other similar compounds) and even in megalomania. The Old English for mickle was micel. Latin magnus is also related. Though the root vowel of magnus has baffled word historians for generations, it need not bother us. Perhaps in the opinion of some people living long ago, the Latin adjective denoting bigness needed a wide-open sound. This conjecture is not a joke: short i (as in it) tends to suggest smallness, while a (as in up) has the opposite effect.

Let me repeat what I say with perhaps irritating regularity. Discovering cognates is a necessary prerequisite for deciphering a word’s etymology, but even if we are fortunate enough to put together a long list of related forms, we want to reconstruct the link between sound and meaning. Presumably, some association between meg-words for “big” and the idea of bigness existed in the past. Outside sound-imitative, sound-symbolic, and baby words, we can seldom discover such associations. Small, as we have seen, goes back to the name of small cattle (perhaps sheep). What was called meg thousands of years ago? Huge beasts or enormous boulders? Once upon a time, adjectives did not differ from nouns, and only their place in a sentence distinguished them. English, which has lost most of its endings, has partly reached that stage again. One can say rose garden and garden rose and guess the meaning only from the word order. To repeat, what associations did meg– evoke, regardless of the syntax?

It is not surprising that such ancient words have an “unknown origin.” While reading the news, I often stop to look up the etymology of “funny words” (slang; our reports are full of slang). Today, I have looked up flub “to botch, bungle,” cagey “shrewd, smart” (an adjective I don’t like, because it reminds me of the Soviet KGB), and glom “to steal.” Only glom was recorded in the nineteenth century and is supposed to go back to a verb in Scots (though I don’t quite understand how the borrowing occurred). Anyway, all three words are late “Americanisms,” and none has any etymology worth mentioning. If even such recent words remain obscure, what can we expect from an ancient adjective that seems to have existed for millennia? To add insult to injury, I may add that huge, a borrowing of Old French ahuge into Middle English, is also of unknown origin, and the same holds for large, another loan from French.

Still, it arouses surprise that one word for “big size” after another falls into the same black hole. The German etymologist Jost Trier (1894-1970) advanced a theory, according to which dozens of words arose in the process of dealing with specific labor activities. This is a reasonable approach (where else should people coin words?), but his results seldom carry conviction, even though he had ardent supporters, among them the distinguished Dutch etymologist Jan de Vries. For instance, the origin of broad and and wide has never been explained to everybody’s satisfaction. The Old English for wide was vīd. Its Old Icelandic cognate had ð (that is, th, as in English the) in the middle. Trier isolated the root wei- ~ wī– in it, connected wide with numerous other words, and spun most interesting, but unverifiable hypotheses. For instance, he allied wide to withy, because withy could be used for building fences. In a similar way, he tried to explain broad, but in this case, his ideas are even less attractive. Since Trier was a serious scholar, he suggested several promising etymologies, but in principle, his conjectures should be treated with utmost caution.

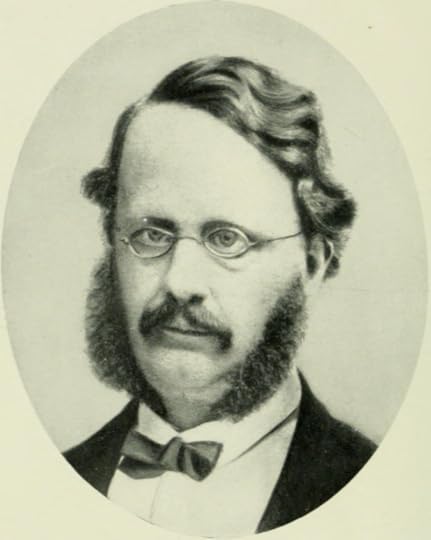

Sophus Bugge, a man who lived up to his name.

Sophus Bugge, a man who lived up to his name.Image by Jara Lisa via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 4.0.

Our main opposite of small is big. Big is also a tough word, but it is not hopeless. It surfaced only in Middle English, around the year 1300. That is why the idea that big goes back to a word like Gothic gabigs (or gabeigs) “rich” holds little promise (such an idea was advanced twenty-five years ago). Ga– in gabeigs was part of the root and could not be reinterpreted as a prefix. Moreover, gabigs had a regular Old English cognate, namely gifig “rich.” An Old Icelandic cognate also existed. That was, to my mind, a stillborn etymology.

Two facts suggest a northern origin of big: the word’s late appearance in English texts (mainly northern!) and the consonant g at the end. A native Old English word would have ended in –dge, like bridge and wedge. Such was Walter W. Skeat’s opinion, and this is what one finds in most dictionaries. Skeat also cited Norwegian bugge “a strong man” (Bugge is a well-known Norwegian last name), along with English regional bug “big” and bog “boastful.” In the thirteenth century, big meant “strong, stout.” Later, the sense “advanced in pregnancy” was recorded (the phrase big with child, that is, “heavy with child, ready to give birth,” is still understood). The current sense of big does not antedate the sixteenth century.

Was this an inspiration for the adjective big?

Was this an inspiration for the adjective big?Image by nidan via Pixabay.

As we have seen, the sense of small goes back to the name for small cattle. Norwegian bugge sounds like Old Icelandic bukkr “he-goat, billy goat” (bokkr and bokki have also been recorded), English buck, German Bock, and several other animal names of horned animals. Skeat referred them to the root of the verb bow “to bend.” Later, several eminent researchers held the same opinion. Though a unified approach to small and big looks appealing, I have some doubts about the connection of big with cattle. It so happens that numerous b-g and p-g words all over Eurasia refer to bulky, fat, and inflated creatures and objects. Bag, bug, bog, pig, pug, and many other nouns belong here. Therefore, I am not sure that big is related to the verb referring to bent horns or antlers. Also, I cannot find any Old Scandinavian word sounding like big and see that Skeat wrote in parentheses: “Scandinavian?”. His question mark is well-appreciated. Big was, most probably, coined in the north of England, and it may be native, one of the numerous b-g words referred to above. Its origin is not “unknown” but somewhat uncertain. Anyway, with it, we, cagey people, are in better shape than with huge and large.

Next week, I’ll discuss the adjective great and bring this series to an end.

Featured image by Calyponte via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 3.0.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers