Oxford University Press's Blog, page 446

November 3, 2016

Thoughts on Dylan’s Nobel

Of all the responses to Bob Dylan’s Nobel, my favorite comes from Leonard Cohen, who likened it to “pinning a medal on Mount Everest.” It’s a brilliant line, pure Cohen—all dignity and poise, yet with an acid barb. Not only is Everest in no need of a medal, the attempt to fix one to its impassive torso (imagine the puny pin bending back on first contact) is metaphorically all too apt for the Nobel committee’s current quandary. To the surprise of exactly no one, Dylan took his time responding to the award, waiting over two weeks; it is still unclear whether he will attend the ceremony. As someone who spends part of my professional life thinking about Dylan, I wince at this; just as I was asked to weigh in by a few journalists on the day of the award, I worry I will also be held to account for his churlishness, guilty by scholarly association (not to mention home state—I’m also a Minnesotan).

Compounding all of this is of course the controversy surrounding the award itself, and whether Dylan deserves a Nobel in literature. The day of the announcement I found myself telling a colleague that I felt odd weighing in on what should and shouldn’t count as literature, as I, a music scholar, had “no horse in that race.” He responded with the obvious: “You do now,” adding, “he just came in first.” So, of necessity—and over the course of more conversations—I began to feel my way toward a tentative position, often gesturing to the complex history of literature and performance, a dialectic that has lost some of its animating tension in recent generations, but that casts a long historical shadow, extending back through Shakespeare to Homer. The Nobel committee’s citation helped in this regard. Dylan was awarded the prize “for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition.” The emphasis on song at once sidesteps the tedious question of whether Dylan’s lyrics “are really poetry” and situates their literary aspects in a network that also embeds music, voice, and the moment of their sounding. The preposition “within” is also helpful. While the committee clearly means “within the tradition” of American song, if one squints a bit one can read “new poetic expressions within song.” The nestling of poetic expressions within the unpredictable alchemy of performed song seems right, for Dylan’s literary efforts have always been most potent when they are tempered—annealed—by the pressures of song, with its demands for formal concision, metric clarity, and verbal thrift. Without that tempering, his writing can be embarrassingly prolix, like Kerouac or Ginsberg on an especially undisciplined day. (I am thinking of his well-nigh unreadable early book Tarantula as well as the liner notes for the early records; his 2005 memoir Chronicles, Vol. 1 is a luminous exception: punchy and vivid, even if brimming with falsehoods and borrowed lines.)

Consider the opening verse from 1965’s “She Belongs to Me”:

She’s got everything she needs / she’s an artist, she don’t look back

She’s got everything she needs / she’s an artist, she don’t look back

She can take the dark out of the night time and / paint the day time black

Here it is the blues that tempers: note the AAB repetition structure, AAA end-rhyme, and the caesuras (rendered here as slashes) that perforate each line. Dylan was then, and is now, a connoisseur of blues lyrics. Unlike legions of British guitarists, he was compelled not only by Robert Johnson’s technical musicianship, but by his inscrutable words:

The songs were layered with a startling economy of lines… Johnson’s words made my nerves quiver like piano wires… I copied [them] down on scraps of paper so I could more closely examine the lyrics and patterns, the construction of his old-style lines and the free association that he used, the sparkling allegories, big-ass truths wrapped in the hard shell of nonsensical abstraction… (Dylan 2004, 283–85)

These words could just as well describe “She Belongs to Me,” in all of its startling economy. Its compression is so intense as to fuses literary registers. The third line—“She can take the dark out of the night time and / paint the day time black”—is at once a “perfect blues line” (Gray 2000, 275) and a nod to the Symbolists who so captivated Dylan: Rimbaud’s hued intoxication (“J’ai rêvé la nuit verte aux neiges éblouies”/ “On green nights I’ve dreamt of dazzled snows”), Verlaine’s celebrated musicality.

Yet here the “musicality” is more literal: this is a song, and it lives in the singing. Note first the preponderance of monosyllables. The only exceptions are the aptly generous “everything” and the “artist” who possesses it. Otherwise, each word pings out a single syllable, its vowel ripe for the work of Dylan’s idiosyncratic voice. In the studio recording of January 14, 1965 that voice does its work within a gentle groove that studiously avoids indexing the blues. Eighths are straight, not swung—Bobby Gregg’s drums all tasteful rim-shots and brushes—and Bruce Langhorne’s guitar punctuates Dylan’s sung lines with rippling sixths that are about as far from the blues as one can get. And then there’s the harmony, which swerves from 12-bar expectations precisely at the word “dark,” with one of the brightest harmonies in Dylan’s vocabulary: a major II# chord, which eases into a diatonic IV at “paint the day time black” (the paradoxically nocturnal raised fourth degree of the II# chord lowering to its diatonic version in IV, under pressure of the artist/lover’s brush). This is in fact a classic Beatles progression, I–II#–IV–I, which had been chiming joyously out of radios and record players since “Eight Days a Week” was released on December 4th, 1964, just over a month before Dylan entered the studio. Whatever influence that song may have had on Dylan here (and he was, recall, the band’s most famous superfan at this point), his singing resists the Beatles’ ecstatic vocal delivery: in contrast to their sharply etched tune, he lazily drapes his voice over the shimmering harmonic swerve, rising nonchalantly to a tonic A3 plateau at several points in the line (“dark” and “paint” receive particular emphasis). The result is an exquisite equipoise of light and dark—verbal, musical, vocal, instrumental—its density of connotation exceeded only by the understated grace of its execution.

Dylan is often celebrated for his syncretism, his knack for mashing-up musical and lyrical readymades. The diminutive “She Belongs to Me”—often overshadowed in the canon by billowing epics like “Desolation Row” and “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands”—is a quiet triumph in this regard. Robert Johnson, Rimbaud, Verlaine, Lennon and McCartney: all sound together in a new configuration. And yet Dylan’s voice—at once writerly and sonic, ideal and empirical—remains stubbornly singular, irreducible to their influence. Is the result literature? The question loses its urgency in the face of the song’s achievement, which coolly leaves debates about medals and mountains to others. And yet, if one listens closely, one can almost hear Dylan’s answer—for once tender as well as aloof—in another song on side one of Bringing It All Back Home, “Love Minus Zero / No Limit”:

In the dime stores and bus stations

People talk over situations

Read books, repeat quotations

Draw conclusions on the wall

(…)

Statues made of matchsticks

Crumble into one another

My love winks she doesn’t bother

She knows too much to argue or to judge

Image credit: Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C. [Entertainment: closeup view of vocalists Joan Baez and Bob Dylan.], 08/28/1963 by Rowland Scherman. Public Domain via U.S. Information Agency. Press and Publications Service, (National Archives Identifier) 542021 and Wikimedia Commons.

This article originally appeared on Musicology Now.

The post Thoughts on Dylan’s Nobel appeared first on OUPblog.

Tracing viking travellers

The medieval Norse were adventurous travellers: not only raiders but also traders, explorers, colonisers, pilgrims, and crusaders. Traces of their trips survive across the world, including ruined buildings and burials, runic graffiti, contemporary accounts written by Christian chroniclers and Arab diplomats, and later sagas recorded in Iceland. Their adventures spanned from New Foundland to Baghdad, and many other countries in between.

In this interactive map, you can follow the trail of the vikings to far-flung lands, with some possibly surprising results.

Featured image credit: “Guests from Overseas” by Nicholas Roerich, from the series “Beginnings of Rus’. The Slavs.” 1901. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Tracing viking travellers appeared first on OUPblog.

November 2, 2016

Blessing and cursing part 2: curse (conclusion)

The verb curse, as already noted, occurred in Old English, but it has no cognates in other Germanic languages and lacks an obvious etymon. The same, of course, holds for the noun curse. The OED keeps saying that the origin of curse is unknown. Indeed, attempts to guess the word’s etymology have not yielded a universally accepted solution. For a long time the oldest dictionary makers tried to derive curse from cross by transposing the sounds in the middle. Such a process (called metathesis) is not only possible but even common, and r is the usual victim of it. The anthologized example is Engl. burn versus German brennen; however, there are dozens of others. Given this reconstruction, we are left wondering how the meaning of curse developed. Since there were so many possibilities to borrow a Latin word or to use a suitable native one to express the idea of cursing, why should the missionaries or clerics have gone to the trouble of mutilating the noun for “cross” and endowed the product with such a meaning? Some people found the link in the verb crucify. But to curse is not the same as to crucify, so that this idea carries little conviction.

This is the famous Ruthwell Cross erected in England some twelve centuries ago. The word curse has nothing to do with cross

This is the famous Ruthwell Cross erected in England some twelve centuries ago. The word curse has nothing to do with crossIt is quite possible that curse came to Anglo-Saxon England from abroad. Skeat looked for a Scandinavian source. He referred to Norwegian kors ~ kros, which, as he observed, could mean “plague, trouble, worry.” Swedish korsa and Danish korse “to make the sign of the cross” could, in his opinion, develop into Engl. curse. Kors! in Danish is indeed often used as an imprecation. Thus, curse was said to mean something like “to swear by the cross” or “to ban, drive away, excommunicate by the sign of the cross.” This looks like rather uninspiring guesswork, for Danish kors is a typical oath, like Engl. ’sblood (that is, His blood). An ingenious but unacceptable etymology connected curse with the meaning of the adjective cross “angry” (virtually unknown in the United States but common in British English, as in: “If you don’t behave, I’ll be very cross with you.”). However, this sense of cross is late (recorded only around 1600) and could not be the source of curse.

Skeat stuck to his etymology despite the OED’s disagreement with it. In the last (1910) edition of his dictionary, he even added a special paragraph on the alleged Scandinavian source. But, curiously, in his popular A Concise Dictionary…, published at the same time, no mention of Scandinavian is left, and the Old Irish form cúrsaigim “I reprehend” appears (note that ú designates a long vowel). We are invited to “compare” it with curse. Skeat implied that he had found the Irish form in the 1880 dictionary by the distinguished German Celtologist Ernst Windisch. Yet, more likely, he learned about it from Kluge’s 1899 book English Etymology. Curse is said there to be cognate with (!) Old Irish cúrsachaim (sic) ‘I seek’; Kluge added: “Source and history unknown.” At least two modern etymological dictionaries of English cite the Celtic hypothesis without committing themselves. They probably found it in Skeat. Finally, in 1921 Max Förster made a strong case for the English word being a borrowing from Old Irish. I referred to his book-length article on the Celtic influence on the vocabulary of English in Part 1 of the post on curse.

“Plague o’ both your houses.” This is perhaps the most famous curse in the history of English literature

“Plague o’ both your houses.” This is perhaps the most famous curse in the history of English literatureThe next step in my exposition goes back to Andrew Breeze’s article in Notes and Queries 238, 1993, pp. 287-289. The Old English verb cursian appeared first in Northumbrian texts and gradually made its way south; Northumbrian clerics had especially close ties to Ireland. The Irish forms are cúrsagad “reprimand, reproof” and cúrsagaid “corrects, chastises, rebukes.” It follows that the meaning of curse, assuming that English has the word from Irish, developed on British soil. We will soon see that a slightly different approach to the word’s history can be more profitable. Förster and Breeze discussed the same material, but only Förster noted that, if curse had an Irish etymon, the vowel u must have been long in Old English (and it was short). As far as I know, there have been no attempts to account for the shortening. Perhaps this is the reason Karl Luick, a great historian of English phonetics, in a special note added to his section on Irish words in English wrote that curse was not borrowed from Irish. Most regrettably, his apodictic remark provides no material for discussion. As regards Irish cúrsagad, Breeze supported its now universally accepted derivation from Latin curas agere, which can be glossed rather loosely as “to exercise control.” (Incidentally, the English noun cross, which supplanted rood “cross,” did penetrate English from Irish.)

Other than that, I am aware of three more etymologies of curse. The entry in the first edition of The Century Dictionary is a cautious version of Skeat’s, but in the second edition not a trace of it remains. We read (with the abbreviations expanded): “[from] Latin cursus, a course, specifically in ecclesiastical usage, the regular course, or series of prayers and other offices said or sung by the priest…. The ecclesiastical cursus included at times a formula of general commination or excommunication called ‘the major excommunication’, as distinguished from ‘the minor excommunication’, pronounced in certain cases.” If Charles P. G. Scott, the etymologist for The Century Dictionary, found this derivation, so different from Skeat’s and the OED’s, in some source on the history of religion, I have not been able to locate it. Scott’s suggestion was neglected, but Middle English Dictionary (MED) resurrected (or rediscovered?) and enriched it, though with a bit of hedging, and explained that Middle Engl. curs is “the set of daily liturgical prayers, applied to ‘the set of imprecations’ of the gret curs [great curse] ‘the formula read in churches four times a year, setting forth the various offenses which entailed utmost excommunication of the offender; also, the excommunication so applied; the state of being under excommunication and, hence, in mortal sin; mortal sin.” This is a very convincing etymology. It appears as though in Middle English the Old Irish verb met Latin cursus and merged with it, so that curse may have had two sources. That is perhaps why the word acquired a short vowel!

The rest will sound like an anticlimax. Leo Spitzer (1946) traced curse to the Latin noun incurusus, as in the phrase incursus poenam “the fact of having incurred a penalty.” He had to account for the loss of the prefix in the word incursus and did offer some explanation, but, as was pointed out by one of his critics, the main trouble with this etymology is that the reflexes (continuations) of incursus do not appear with the sense “curse” in any Romance language. Ernst Weekley, like Leo Spitzer, had a profound knowledge of Old French. That is why both of them were always on the lookout for the Romance etymons of English words. Weekley derived curse from Old French coroz, Anglo-French curuz (Modern French courroux “anger, wrath”), whose Latin source is related to Engl. corrupt. In his dictionary, Henry C. Wyld referred to Weekley, but here Spitzer was, I think, right: the word curse turned up in English too early to be a borrowing from French. Finally, there is a Germanic etymology of curse. Its author, Otto Ritter, based his reconstruction on a questionable meaning of an Old English word, and I will refrain from going into detail.

In my opinion, the verdict origin unknown should be used only when there is really nothing to be said about a word. In other cases, a summary, however cautious, would be helpful, for example: “Curse. [Attested forms] The derivation from cross, though often suggested in the past, cannot be substantiated. Unlikely are also the derivations by L. Spitzer from Latin (in)cursus ‘the fact of having incurred a penalty’ and by E. Weekley from Anglo-French curuz ‘wrath. A Germanic source (Otto Ritter) is even less likely. By contrast, the derivation from Latin cursus ‘a formula for excommunication, etc.’ (The Century Dictionary and Middle English Dictionary), sounds convincing. Rather probably, the Latin formula merged with a borrowing of Old Irish cúrsagad ‘reprimand’ and yielded the modern form, which then is a blend.

A curse averted. She will sleep, not die, and Prince Charming will kiss her into womanhood.

A curse averted. She will sleep, not die, and Prince Charming will kiss her into womanhood.This is not a great entry, but, admittedly, better than nothing. And if the idea of cúrsagad, from curas agere, and cursus having produced the modern form is correct, we know everything about Engl. curse we would like to know!

Images: (1) “The Ruthwell Cross” by Lairich Rig, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. (2) “Death of Mercutio” by Edwin Austin Abbey, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. (3) “Briar Rose” by Anne Anderson, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. Featured image: “Canterbury Cathedral – Portal Nave Cross-spire” by Hans Musil, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Blessing and cursing part 2: curse (conclusion) appeared first on OUPblog.

A new philosophy of science? Surely that’s been outlawed

The main thing that drew me to the history and philosophy of science was the simple desire to understand the nature of science. I was introduced to the exciting ideas of Popper, Kuhn, Lakatos, and Feyerabend, but it soon became clear that there were serious problems with each of these views and that those heydays were long gone.

Professionals in the field would no longer presume to generalize as boldly as the famous quartet had done. For the past 40 years or so the field has seen increasing levels of specialization. These days, philosophers of science tend to work on specific topics such as reduction, emergence, causation, the realism-anti-realism debate, or the latest band-wagon—mechanism. Meanwhile many other historians and philosophers have gone off at the deep end by concentrating almost exclusively on the context of discovery rather than on the actual science at stake. As we all know this development led to the nefarious Science Wars, which are only now finally starting to recede into the background.

As for my own work I have specialized in the history and philosophy of chemistry and in particular on the periodic table, including the question of the extent to which this system of classification reduces to quantum mechanics. More recently I have worked on the discovery of the elements and on scientific discovery in general. I have pondered over the question of scientific priority and multiple discovery. I seem to have now arrived, or maybe have stumbled into, a general approach to the philosophy of science of the form that one is no longer supposed to indulge in. Let me share a little of this view with you in case you have not now decided to switch off.

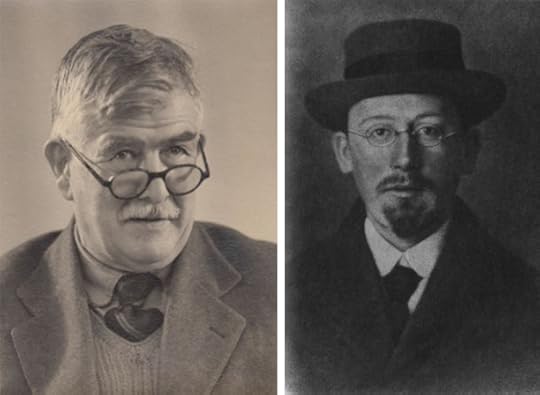

From left to right: 1) Charles Bury, chemist. Used with permission. 2) Dutch amateur scientist Antonius van den Broek (1870-1926). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

From left to right: 1) Charles Bury, chemist. Used with permission. 2) Dutch amateur scientist Antonius van den Broek (1870-1926). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.My work has focused on several minor figures in the history of modern chemistry and physics. They include such virtually unknown scientists as John Nicholson, Anton van den Broek, Edmund Stoner, Charles Bury, John Main Smith, Richard Abegg, and Charles Janet, none of whom are exactly household scientific names. What I see convinces me that these ‘little people’ represent the missing links in the evolution of scientific knowledge. I take the evolutionary approach quite literally as I will try to explain. Rather than concentrating on the heroic figures like Bohr, Pauli, and G.N. Lewis, in the period that interests me, I see an organic whole, the body scientific that is continually putting out random mutations in the form of hunches, guesses, speculations. No doubt the recognized giants of the field are those that seize upon these half-baked ideas most effectively. But in trying to understand the nature of science, we need to stand back and view the whole process from a distance.

What I see when I do that is something like a living, fully unified, and evolving organism that I have called SciGaia by analogy to James Lovelock’s Gaia theory, whereby the earth is one big living organism. But I reject any notion of teleology in my version. Science is not heading towards some objective “Truth” and here I agree with Thomas Kuhn who always insisted on this point.

But I disagree with the venerable Kuhn over the question of scientific revolutions. To focus on revolutions is to miss the essential inter-relationship and underlying unity between the work of all scientists whether it be the little or the big people. Talk of revolutions unwittingly perpetuates the notion that science advances through a series of leaps conducted by the heroes of science.

I also part company with most analytical philosophers of science by not placing any special premium on the analysis of the logical and linguistic aspects of science. I regard logic and language as being literally “superficial,” by which I mean that they enter into the picture after discoveries are made, for the purposes of communication and presentation. Discovery itself lies deeper than logic and language and has more to do with human urges and instincts, or so I believe.

Of course I do not claim to have invented the notion of evolutionary epistemology. I just seem to have arrived in somewhere in that camp by examining the grubby details in the development of early twentieth century atomic chemistry and physics such as the introduction of the quantization of angular momentum, the discovery of atomic number, the emergence of the octet rule, the use of a third quantum number to specify the electronic configurations of atoms, and so on.

What I find rather curious is that Kuhn more or less disavowed his early insistence on scientific revolutions in later life and turned to talk of changing lexicons. Indeed, in his final interview, he went as far as to say that the Darwinian analogy, that he had briefly mentioned in his famous book, had been his most important contribution and that he wished it had been taken more seriously.

Featured image by vladimir salman via Shutterstock. Used with permission.

The post A new philosophy of science? Surely that’s been outlawed appeared first on OUPblog.

The rise of passive-aggressive investing

Some good ideas take a long time to gain acceptance.

When Adam Smith argued forcefully against tariffs in his 1776 classic The Wealth of Nations, he was very much in the minority among thinkers and policy-makers. Today, the vast majority of economists agree with Smith and most countries officially support free trade.

Index investing, sometimes called “passive investing,” has taken somewhat less time to gain acceptance, growing from a cottage industry and intellectual sideshow in the 1970s to a major player in the world of finance today.

Indexing consists of picking a benchmark stock index — for example, the S&P 500 index (S&P500) of large capitalization US equities — and buying the components in order to replicate its performance. Thus, the manager of an index mutual fund is sometimes characterized as engaging in “passive investing,” buying the stocks in the index and keeping them in the fund roughly in accordance with their weight in the index, rather than trying to pick individual high-performing stocks, as an “active manager” might do.

The intellectual godfather of index investing is Burton Malkiel, a retired Princeton professor; its Johnny Appleseed is John Bogle, founder and former CEO of the Vanguard Group.

In 1975, Malkiel published A Random Walk Down Wall Street, now in its 12th edition. A Random Walk sets forth, in layman’s terms, the efficient markets view of finance: stock equity prices reflect the best currently available information about the underlying firms. Any attempt to forecast individual stock price movements and “outguess” the market is likely to fail. A better strategy for the equity portion of your portfolio is to buy shares in an index that encompasses a substantial portion of the market; however, stock market mutual funds in the 1970s did not offer such index mutual funds to their clients.

Around the same time that Malkiel’s Random Walk appeared, Bogle founded Vanguard Investments, and shortly thereafter established a stock market mutual fund that approximated the S&P500. Vanguard now has approximately $3.5 trillion under management and is one of the world’s largest investment companies.

The Mutual Fund Store office Livonia Michigan by Dwight Burdette. CC-BY-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The Mutual Fund Store office Livonia Michigan by Dwight Burdette. CC-BY-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Index investing makes good sense for a number of reasons. First, there is ample evidence that nobody, including mutual fund managers and publishers of stock market newsletters, is all that that good at beating market averages. And those that do beat the market in any given year will not necessarily do so again in a subsequent year.

Second, hiring professionals to pick stocks and paying commissions to trade shares increases the cost of managing a mutual fund, which cuts into investor returns. The average expense ratio of US equity mutual funds is somewhere between 0.66% and 1.03%; the average expense ratio at Vanguard is 0.19%. Although the differences in these figures might seem insignificant, assuming a 7% rate of return before expenses, at the end of 30 years an investor would be 11 to 15% wealthier having invested in a low-fee fund rather than a high-fee fund.

Third, actively managed funds can have negative tax consequences for investors because of high turnover. Whenever a fund manager sells shares at a profit, investors receive capital gains, on which they must pay taxes. By contrast, index funds have much lower turnover and hence generate fewer taxable capital gains for their investors.

Given all the advantages of index funds, it is perhaps not surprising that they have become more popular in recent years. Assets in S&P500 index mutual funds have grown by an average of more than 17% per year for the last 22 years; assets in all index mutual funds have increased by an astounding 22% per year during the same period. Among the high profile supporters of index funds is Berkshire Hathaway chairman Warren Buffett, who urged his executors to invest the vast majority of his estate in low cost index funds.

Although indexing has clearly been a boon to investors, it is possible that if the upward continues, it may have some undesirable economic consequences. If everyone indexes, the absence of “active investors” looking for mispricing in the market in order to turn a profit would render the market less useful in attracting funds to growing sectors and firms. Because index funds concentrate their funds in larger companies, more indexing may encourage the growth of large companies (at the expense of smaller ones) simply because they are already large. Finally, large index funds may increase the concentration of firm ownership, with problematic consequences for industrial competition, and put index fund managers in the uncomfortable position of taking a more active role in managing the firms in which they are “passive” shareholders.

Index investing has grown dramatically since the 1970s, and is likely to continue this impressive growth in the years to come. As indexing becomes an even more dominant investment strategy, policy makers will have to remain alert to its potential downside.

Featured image credit: NYSE, New York. by Kevin Hutchinson. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post The rise of passive-aggressive investing appeared first on OUPblog.

Archaic and postmodern, today’s pagans challenge ideas about ‘religion’

Several people chuckled when they walked past Room 513B during the 2009 annual meeting of the American Academy of Religion, held in Montréal. The title of the session within was simply “Idolatry,” held by the AAR’s Contemporary Pagan Studies Group, papers such as “Materiality and Spirituality Aren’t Opposites (Necessarily): Paganism and Objects” were presented.

The nervous laughter at the session’s title shows that even among scholars of religion, topics of polytheism and idolatry seem quaint, antique, and even trivial. Do people still even take them seriously?

Indeed, they do. Pagan religions, both newly envisioned and reconstructed on ancient patterns, are growing throughout the world. In addition, followers of these newer Paganisms, such as Wicca, Druidry, and reconstructed Germanic, Baltic, Slavic, Greek, and other traditions, have begun to reach out to people attempting to maintain other indigenous or tribal traditions.

In the English-speaking world, the best-known new Pagan religion is Wicca, which is one form of Pagan witchcraft. Arguably rooted in Romantic ideas — appreciation of nature, an idealization of the “folk soul” and the countryside, a great appreciation of feminine principles — it was created around 1950 by a retired civil servant and spiritual seeker named Gerald Gardner (1884–1964). Gardner did not seek a mass movement but more of a “mystery cult” in the classical sense — small groups of initiates who would meet according to the lunar calendar to worship a goddess symbolized by the Moon and a god symbolized by (among other things) a stag or goat or the Sun, and to perform magic.

Wicca, as the British historian Ronald Hutton has noted, is the “the only religion that England has given the world.” Lacking missionaries, Wicca, which can be practiced solo or in groups, spread by books and later the Internet — where it can be found not just in the English-speaking world, but also in Western Europe, Brazil, Russia, and Mexico, among others.

While fraternal and cultural Druidic groups existed in the British Isles from the eighteenth century onwards, it was only in the mid-twentieth century that self-consciously Pagan Druidism began, seeking to restore both a harmonious relationship with nature (Druids are frequent eco-protestors) and to restore the relationships with ancient British deities.

By contrast with Wiccan individuality, Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union have seen the rise of numerous Pagan groups that claim to express the true identities of Baltic and Slavic people. Among the first were Pagan movements that blossomed in the Baltic nations of Latvia and Lithuania after the collapse of imperial Russia, offering a return to folk roots severed by the violent arrival of Christianity in the late Middle Ages. In Latvia, Pagans called Dievturi sought to reconstruct traditional religion through the study and performance of dainas (folksongs), traditional arts, archaeology, folk healing, and other practices, while denouncing Christian clergy as “alien preachers.” A key leader, Ernests Brastiņš (1892–1942), was arrested and executed by the Soviet Union after the Red Army swept into Latvia.

Wiccan event in the US, by Ycco. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Wiccan event in the US, by Ycco. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Similarly in Lithuania, nineteenth-century folklorists collected songs that twentieth-century reconstructionists mined for older worldviews and practices. Old festivals were revived in a self-conscious way, and in 1911 the new religion of Romuva was proclaimed by Domas Šidlauskas-Visuomis (1878–1944). As in Latvia, when Lithuania was annexed to the Soviet Union, Romuva was outlawed and persisted only underground and among Lithuanian immigrants in North America. With independence regained, the new national government recognized Romuva as a “non-traditional” religion in 1995, because of its organizational newness.

Now Russia itself has its own “Native Faith” movement, challenging the Russian Orthodox Church as to which best expresses “true Russian spirituality,” while similar movements have arisen in Ukraine, Poland, and elsewhere. In Scandinavia, followers of Norse “Native Faith” groups also meet. One is Ásatrú (followers of the Norse gods), especially prominent in Iceland, where construction of a new, purpose-built temple began in 2015.

Ásatrú has planted roots in North America, part of a larger Heathen revival, to use a more general term for Norse and Germanic reconstructed Paganism. But America’s and Canada’s cultural history are different than Iceland or Latvia; here religious identity cannot be linked to cultural heritage in the same way. From Wicca to Ásatrú, all these forms of Paganism pose a problem for both scholars’ and the general public’s understanding of “religion.”

Paganism is polytheistic, although Pagans themselves debate just how separate and distinct their gods actually area. There are no elevated prophets and no holy scriptures — although Pagans themselves produce a plethora of books, blogs, and journals. Scholars whose approach is primarily textual may find little to grasp, unless they return to ancient texts like the Iliad or the Eddas to understand how they shape contemporary practice.

Pagans expect that divinity can manifest in many ways: through a ritual participant temporarily “ridden” by a god or goddess, through art, through natural features such as trees or rivers, or through ecstatic experience of any sort. Sometimes this principle of relationship is stated as, “Pagan mysticism is horizontal, not vertical.” While humans are fallible and make mistakes, no contemporary Pagan religion preaches hell and damnation. (An acceptance of reincarnation is fairly common.)

Pagan religion identity is fluid. The same individual might be initiated in a Vodú “house” and attend a ritual blot at an Ásatrú hof. Contemporary Paganism is relational rather than revelatory. Instead of being told how to worship the One God, a Pagan might form ritual and personal relationships with several who have spoken to him or her through dreams or other life experiences.

Even the term “worship” is problematic among many Pagans, since it suggests submitting to an absolute ruler and begging for favors. “To honor” is often preferred.

Increasingly, polytheistic, animist, and tribal religions begin to make common cause in an inter-connected world. With no one god/one book/one truth ideology, and no mandate to convert “unbelievers,” Pagans of all sorts are more likely to support each other against monotheisms that bulldoze their uniqueness. They challenge the claim that polytheism is merely a stage on the way to “true religion” or to moving “beyond religion.” They affirm that their “horizontal” relationship with divinity embraces an environmental ethic that no longer treats the natural world in only utilitarian ways.

Featured image credit: Hellen ritual by YSEE . Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Archaic and postmodern, today’s pagans challenge ideas about ‘religion’ appeared first on OUPblog.

November 1, 2016

The essence of presidential leadership

The challenges of governing have rarely been greater. The distance between the parties in Congress and between identifiers with the parties among the public is the greatest in a century. The public accords Congress the lowest approval ratings in modern history, but activists allow its members little leeway to compromise. The inability of Congress and the president to resolve critical problems results in constant crises in financing the government, endless debate over immigration, health care, environmental protection, and other crucial issues, and a failure to plan effectively for the future.

Given the difficulties of governing, it is not surprising that presidents typically choose a strategy for governing based on the premise of overcoming impediments to policy change by creating new opportunities through persuasion. Entering the White House with vigor and drive, they are eager to create a legacy. Unfortunately, they also begin their tenures with the arrogance of ignorance and thus infer from their success in reaching the highest office in the land that both citizens and elected officials will respond positively to themselves and their initiatives. As a result, modern presidents invest heavily in leading the public in the hope of leveraging public support to win backing in Congress.

It is not surprising that new presidents, basking in the glow of their electoral victories, focus on creating, rather than exploiting, opportunities for change. It may seem quite reasonable for leaders who have just won the biggest prize in American politics by convincing voters and party leaders to support their candidacies to conclude that they should be able to convince members of the public and Congress to support their policies. Thus, they need not focus on evaluating existing possibilities when they think they can create their own.

Campaigning is different from governing, however. Campaigns focus on short-term victory and candidates wage them in either/or terms. To win an election, a candidate need only convince voters that he or she is a better choice than the few available alternatives. In addition, someone always wins, whether or not voters support the victor’s policy positions.

Seal of the President of the United States. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Seal of the President of the United States. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. Governing, on the other hand, involves deliberation, negotiation, and often compromise over an extended period. Moreover, in governing, the president’s policy is just one of a wide range of alternatives. Furthermore, delay is a common objective, and a common outcome, in matters of public policy. Neither the public nor elected officials have to choose. Although stalemate may sometimes be the president’s goal, the White House usually wishes to convince people to support a positive action.

In sum, we should not infer from success in winning elections that the White House can persuade members of the public and Congress to change their minds and support policies they would otherwise oppose. The American political system is not a fertile field for the exercise of presidential leadership. Most political actors, from the average citizen to members of Congress, are free to choose whether to follow the chief executive’s lead; the president cannot force them to act. At the same time, the sharing of powers established by the Constitution’s checks and balances not only prevents the president from acting unilaterally on most important matters, but also gives other power holders different perspectives on issues and policy proposals.

Although it may be appealing to explain major policy changes in terms of persuasive personalities and effective leadership style, public opinion is too biased, the political system is too complicated, power is too decentralized, and interests are too diverse for one person, no matter how extraordinary, to dominate. Neither the public nor Congress is likely to respond to the White House’s efforts at persuasion. Presidents cannot create opportunities for change. There is overwhelming evidence that presidents, even “great communicators,” rarely move the public in their direction. Indeed, the public often moves against the position the president favors. Similarly, there is no systematic evidence that presidents can reliably move members of Congress to support them through persuasion.

The context in which the president operates is the key element in presidential leadership. Successful leadership, then, is not the result of the dominant chief executive of political folklore who reshapes the contours of the political landscape, altering his strategic position to pave the way for change. Rather than creating the conditions for important shifts in public policy, effective leaders are facilitators who work at the margins of coalition building to recognize and exploit opportunities in their environments. When the various streams of political resources converge to create opportunities for major change, presidents can be critical facilitators in engendering significant alterations in public policy.

Recognizing and exploiting opportunities for change—rather than creating opportunities through persuasion—are essential presidential leadership skills. As Edgar declared in King Lear, “Ripeness is all.” To succeed, presidents have to evaluate the opportunities for change in their environments carefully and orchestrate existing and potential support skillfully. Successful leadership requires that the president have the commitment, resolution, resiliency, and adaptability to take full advantage of opportunities that arise.

Featured Image Credit: Washington DC by retzer_c. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post The essence of presidential leadership appeared first on OUPblog.

Does skin cancer screening work?

According to the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), only limited evidence exists that skin cancer screening for adults is effective, particularly for melanoma mortality.

USPSTF evidence-based preventive care recommendations

Finding melanoma at early stages improves outcomes. That has led to research on the subject and suggestions from professional groups, such as the American Academy of Dermatology and the Skin Cancer Foundation, for yearly visits with a dermatologist.

The USPSTF is a group of independent preventive-care experts supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

“We come together to make evidence-based preventive care recommendations for clinical services, those provided or ordered within the clinical setting,” said task force member Michael Pignone, MD, PhD, professor of medicine at the Dell Medical School at the University of Texas at Austin.

Although the task force screens issues, it also makes—and regularly updates—recommendations in other areas of preventive medicine such as counseling and medications. The last update on skin cancer was published in 2009. In this case, the task force chose the Group Health Research Institute at Kaiser Permanente Research Affiliates Evidence-based Practice Center in Portland, OR, to do the research on skin cancer screening. The center assembled the research and reviewed the information. “The ability to find and treat melanoma with the most conservative surgery possible may be a benefit of screening,” Fundakowski said. “It may not have an impact on survival.”

The task force’s research plan on screening for skin cancer was posted for public comment in May. The final recommendation was released on 26 July 2016, about two years after the task force completed its work.

“We proposed a work with a set of questions that was posted publicly, and comments were received,” said coauthor Nora Henrikson, PhD, MPH, a research associate at the Group Health Research Institute in Seattle and a coinvestigator at the center. “After the task force and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality approve the work plan, we conduct the systematic review of the literature. Once we identify the articles that meet our inclusion criteria, we extract the data from each. That becomes the basis for our report”.

Once the task force reviewed the information, it was clear that the evidence for skin cancer screening wasn’t very strong.

“We found that there is really very limited information available to answer our questions,” Henrikson said.

Insufficient evidence to support recommendation

Therefore, the USPSTF issued an I statement, meaning insufficient evidence was present to support a recommendation either for or against the clinical service. The I is given when the evidence is nonexistent, unclear, or contradictory and when assessing the magnitudes of harm versus benefits isn’t possible.

That doesn’t mean skin cancer screening isn’t effective, however.

Trusted Mole Check Clinic in Australia by Skincareaus. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Trusted Mole Check Clinic in Australia by Skincareaus. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.“Often when the task force issues an I statement, it is misconstrued as a recommendation against screening, and that is not the case,” Pignone said. “This is just an indication that we that we don’t know enough information to give good, evidence-based guidance.”

He said that patients and their doctors should decide about screening on the basis of each patient’s specific circumstances.

“A really important caveat in this is to remember that this is a discussion of screening an asymptomatic person of average risk,” Pignone said. “This doesn’t apply to those with a previous diagnosis of melanoma, who have a strong family history, or something that worries them. Their increased risk may warrant a different approach.”

Impediments to further research

The task force also issues suggestions for areas of research that are needed to provide more evidence for each service they assess. However, many of those recommended studies may be hard to perform given the relatively slow growth of the lesions and the few cases in comparison with other cancers.

“It would require a very large study to enroll enough people into a randomized, controlled trial of screening and then following them all the way out to skin cancer outcomes,” Henrikson said. “That may be a priority for funding compared to other kinds of screenings or preventive interventions.”

Another impediment to getting substantive research into screening for skin cancers is the way melanoma develops.

“If the goal of the screening program is to identify and treat patients as early as possible in order to increase survival, it may not be easy to demonstrate, as the five-year survival rate based on the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program database is already at 91%,” said Christopher Fundakowski, MD, assistant professor of surgical oncology at Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia. “This is largely because the majority of melanomas will present at localized or early stage.”

Morbidity of treatment

Although most patients with melanoma will be alive at five years, other factors must be considered, such as the morbidity and potential disfigurement caused by surgery. “The ability to find and treat melanoma with the most conservative surgery possible may be a benefit of screening,” Fundakowski said. “It may not have an impact on survival.”

Eye as an assessment tool

Another concern is that the difference between a slow-growing lesion and a more aggressive one can be just a few millimeters. Big differences occur with very small changes.

“When we are using the eye as an assessment tool, it just isn’t a fine enough instrument to detect these kinds of differences with any accuracy,” Fundakowski said. “That is why sensitivity of visual screening, or the ability to correctly identify melanoma, is around 50%.”

Most people with skin cancers do well. That trend makes developing a successful screening program difficult.

“When you have many more deaths, it is easier to create screening tests that save more people,” Fundakowski said. “For skin cancer, you would need very specialized screening methods, and we just don’t have them yet.”

The big win for melanoma patients will come when physicians can readily identify deep lesions and those likely to spread.

“While this is a small percentage of all melanomas, these are the patients who will have the most to gain from early diagnosis and treatment,” he said.

A version of this article originally appeared in the Journal of the Nation Cancer Institute.

Featured image credit: Micrograph of malignant melanoma. Photo by Nephron. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Does skin cancer screening work? appeared first on OUPblog.

Health inequalities call for advocacy and public engagement

There has now been a consistent stated policy desire to reduce health inequalities for nearly two decades. Yet, despite a mass of research and raft of policy initiatives on the topic of health inequalities in the 19 years since, current indicators suggest either that health inequalities have continued to widen or that progress has been remarkably limited. The failure to reduce health inequalities in the UK has led to some reflection among researchers working in this field, with two distinct explanations both attracting support. For some, the policy failure simply reflects failings in the evidence-base: health inequalities researchers have simply not been able to advise policymakers on ‘what works’ in tackling health inequalities. Others, however, take a much more normative (values-based) view, arguing that the policies put in place to tackle health inequalities were shaped by ideological commitments to national economic growth, limited state intervention in markets and, more recently, a need to reduce the public deficit. In other words, some people think the failure is down to evidence and others to politics, ideologies, and values.

Lots of books and articles have been published about health inequalities (a quick Google Scholar search for the term returns 104,000 hits) and many of these seem to assume that expanding and developing the evidence-base will assist with policy efforts to reduce health inequalities. And perhaps some of this evidence will but, as former policy advisor to Tony Blair, Geoff Mulgan, has noted, in a democracy politicians have every right to ignore evidence, particularly if they think it goes against public preferences. That’s one reason that journalists and some political scientists spend so much time polling people to try to figure out what they think.

What role, then, might evidence play in policy development around health inequalities? Perhaps it’s time to move beyond the idea of evidence-based policy to start focusing on how different kinds of actors employ evidence in policy debates. This includes understanding how interests that can run counter to public health, such as unhealthy commodity producers like the tobacco industry, engage with policy debates about health inequalities. It also means better understanding the relationships between research, policy, and advocacy for tackling health inequalities.

…the role of science is not to tell us (or our political leaders) what we (or they) should do, or how we should live, but rather to make more meaningful choices possible.

There are two very different ways of thinking about public health advocacy. In Chapman’s terms, it includes (amongst other things) working to place and maintain issues on public and political agendas (and exploiting opportunities to do so), discrediting opponents of public health objectives, and working to frame evidence in persuasive ways (e.g. via metaphors or analogies). In other words, advocacy involves strategically selling public health objectives to a range of non-academic audiences. This way of thinking about advocacy, which has been termed ‘representational’, implies that health inequalities researchers first need to achieve some kind of consensus around the policy (or societal) changes they are trying to ‘sell’ and then work to strategical sell this idea. This involves important work to try to attract political and public attention to the idea, including via the promotion of the research underpinning it.

A rather different way of thinking about ‘advocacy’ is in ‘facilitational’ terms; work akin to Burawoy’s notion of ‘public sociology’. Here, the emphasis is on researchers’ willingness and ability to engage in dialogue with members of the public. It might involve, for example, working with relevant communities to ensure that voices which might traditionally be ignored are given a greater voice in policy debates.

In sum, while commitments to ‘evidence-based policy’ might sound reassuring, they risk: (1) ignoring the realities of policymaking in democracies (and therefore failing); and (2) striving for what is, in effect, an elitist, technocratic approach to decision-making. I find myself agreeing with Max Weber that the role of science is not to tell us (or our political leaders) what we (or they) should do, or how we should live, but rather to make more meaningful choices possible. In practical terms, this means finding ways to ensure that people are able to meaningfully engage with research evidence. And in a democracy, this shouldn’t simply be the people academics often ubiquitously refer to as ‘policymakers’. Rather, we need to get much better at creating deliberative spaces in which researchers, policymakers and members of the public come together to discuss and debate evidence and ideas in ways that acknowledge the role of values and ethics.

Featured image credit: Cold bench by Pexels. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Health inequalities call for advocacy and public engagement appeared first on OUPblog.

The Universities UK taskforce: one year on

It is now a year since it was announced that Universities UK would be establishing a taskforce on the problem of sexual violence in higher education. At its first meeting it widened its remit to also include the (much) broader issue of hate crime affecting students, but promised to maintain a particular focus on violence against women and sexual harassment. The taskforce intended to consider the current evidence, any ongoing work, and what more needs to be done.

As we move towards the date that the report will be published, it is worth reflecting on the importance of the work of this taskforce. I write this as a relative outsider to the process – I am not on the taskforce and have been on maternity leave for much of it so have not been able to attend any of their seminars or workshops. But I write as someone with a huge stake in the taskforce “getting this right”.

As a Professor at Durham University who specialises in violence against women research, I feel a huge responsibility to ensure our students feel safe and free to have a fun and positive experience at university. I’ve been publicly critical of the defensive approach taken by some universities and their failures to treat survivors of sexual violence who speak out with the respect and care they deserve.

We owe it to our students to ensure their experience is a safe and positive one at university.

It was while listening to delegates from a range of universities attending an Epigeum event recently where I spoke about the online course I am lead advisor to (training staff to respond appropriately to disclosures of sexual violence) that I realised just how important it is that the Universities UK taskforce “gets this right”. So many universities are ready to act on the recommendations and are ready to put things in place to properly tackle sexual violence at university. But they often don’t have the necessary knowledge or experience to know where to start – especially in terms of what disciplinary options are available where students don’t want to make a police report but also on what to do while criminal justice system investigations are ongoing. The need for a clear framework for universities to develop their own approach came through clearly at the event.

Part of me feels concerned about whether the Universities UK report will be able to be clear enough given its broadened remit and the seemingly few meetings held. But as a natural optimist, I will continue to look forward to the report and hope that real, bold actions will be taken by universities on the back of it. We owe it to our students to ensure their experience is a safe and positive one at university and that we are willing to take actions to protect and promote this.

This article first appeared on the Epigeum Insights blog on 5 October, 2016.

Featured image credit: Student-library-university. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post The Universities UK taskforce: one year on appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers