Oxford University Press's Blog, page 444

November 7, 2016

Taking back control from Brussels – but where to?

Brexit has been described as “taking back control”, but that simple statement inevitably fails to reflect the complexity of the future that lies ahead. International environmental law obligations, provide the background to much of what is done in a more detailed way in relation to environmental protection by the EU and the UK. These obligations will take on new significance and even continue to constrain the UK’s freedom of action, once withdrawal from the EU is complete. As well as looking outside the UK, we have to look within, at the devolution arrangements which means that when Brussels ceases to be responsible for key environmental legislation, most powers will be moved not just to London, but to Edinburgh, Cardiff and Belfast. There are major challenges ahead in settling how these three levels – international, UK and devolved – will interact.

The role of international law is obvious when it comes to the big climate negotiations such as those last December leading to the Paris Agreement, but the UK is a party to important treaties on many other matters such as: air pollution, marine pollution, dangerous chemicals, trade in endangered species, and ensuring public access to environmental information. The extent of such treaty obligations can be easily overlooked since in recent decades the measures needed to give effect to them have often been introduced into the UK through EU law.

These legal commitments will continue, regardless of membership of the EU, and will be a constraint on the UK’s ability to develop its own environmental policies; new trade agreements with the EU and other nations may further affect environmental standards. In practice, though, there are significant differences between obligations in international law and those under EU law. International obligations tend to be expressed in less detailed and strict language, sometimes closer to aspirations than precise legal duties. International regimes usually lack the strong (if slow) measures provided by the EU structures to enforce compliance by states. Moreover, whilst the courts in the UK are bound to ensure that individuals can enjoy the rights conferred by EU law, the same doesn’t apply for international law.

A further issue is the UK’s status in relation to various treaties. Where treaties have been agreed within areas of the EU’s exclusive competence, steps will have to be taken for the UK to become a party to the treaty in its own right (or it will need to decide to withdraw). In other areas the implementation measures needed by the UK will have to be disaggregated from those agreed at the EU level. Thus, for example, in relation to the Paris Agreement, the UK will now have to propose its own separate Nationally Determined Contribution setting out its own climate action plan, as opposed to being covered by the EU’s commitments.

A big question is the role that the devolved administrations will have in the UK’s international dealings. Foreign affairs are reserved to the UK government, but carrying out the steps necessary to implement international obligations may lie at devolved level. Yet international commitments, under environmental or trade treaties, may not align with the policies of devolved governments. The tension here is not new, and exists in relation to EU matters, but there are some marked differences between the EU and international arrangements.

It is the UK which is the Member State of the EU and, therefore responsible for all negotiations, and accountable for ensuring compliance with EU law. This is reflected in the legal framework since the devolution legislation makes it clear that the devolved authorities have no legal power to legislate or act in ways contrary to EU law and the UK authorities have full power to act to ensure compliance, even in areas of devolved competence. Actions breaching EU law can therefore be restrained by the courts and there is a specific power for London to act.

[UK’s] legal commitments will continue, regardless of membership of the EU, and will be a constraint on the UK’s ability to develop its own environmental policies; new trade agreements with the EU and other nations may further affect environmental standards.

For international law things are different. Again, the devolved authorities have no competence to negotiate or reach international agreements – everything must be done through London. On leaving the EU, control of agreements over access to fish in British waters is taken back to London, even though the bulk of the waters lie off, and the bulk of the fleet is based in, Scotland. However, in contrast to the position with EU matters, the devolved authorities are not legally prohibited from acting in ways incompatible with international law. Instead compatibility with international obligations is ensured through the powers of the Secretary of State to intervene. In order to prevent such incompatibility, s/he can prevent Bills going for Royal Assent, revoke subordinate legislation or direct that any other action is, or is not taken by the devolved administrations. This means that any disagreements are not calmed through resolution by the courts, but require political intervention which is likely only to exacerbate the dispute.

This emphasis on London’s direct control – which feels quite different from the sense of participation in the much wider EU arrangement where everyone has to make compromises – may risk heightening tension in various areas. Thus changes to energy policy, including subsidies for renewables, have been seen as undermining Scotland’s plans for its own energy future. Trade agreements offer another potential area of dispute. For example, what will happen if a trade agreement made by London has the effect (intended or not) that products including genetically modified organisms must have access to the UK market, while Scotland and Wales maintain their opposition to such products?

At a less dramatic level, the removal of the need to comply with EU law will risk greater divergence within the UK in relation to environmental law. Even where the different administrations do not have the desire – or as significantly, the capacity – to develop dramatically different policies and standards, there will inevitably be greater fragmentation as each country works with its own distinct administrative structures and the timetables for introducing changes are affected by different electoral schedules and the space in legislative programmes. There may therefore be a case for structures where co-operation and co-ordination can be discussed, to ensure efficiency and avoid unnecessary fragmentation. The Joint Ministerial Committee established as part of the devolution settlement has not been a striking success, whereas less political bodies such as the Joint Nature Conservation Committee may offer a better model.

The overall message is how many different things have to be taken into account as questions of “hard”, “soft”, or any other type of Brexit are settled. Membership of the EU has dampened the risk of fragmentation of environmental law within the UK and placed disagreements between London and the devolved administrations in a wider (and hence less confrontational) setting. It has also obscured the extent to which international law can affect what happens not only in dealings beyond the UK but also within it. It is a multi-dimensional process that has been set in motion, not just a question of what happens between London and Brussels.

Featured image credit: River, UK. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay .

The post Taking back control from Brussels – but where to? appeared first on OUPblog.

November 6, 2016

The news media and the election

How does an avowedly nonpartisan news organization like the New York Times cover an outrageous but media-savvy and factuality-challenged candidate like Donald Trump?

In a recent interview, Times’ executive editor Dean Baquet explained that the press was at first flustered by Trump, that “everybody went in a little bit shell-shocked in the beginning, about how you cover a guy who makes news constantly. It’s not just his outrageous stuff…he says things that are just demonstrably false.” Dealing with the flood of falsehoods proved a challenge. “I think that he’s challenged our language. He will have changed journalism, he really will have.” In the past, Baquet said, journalists “didn’t know how to write the paragraph that said, ‘This is just false.’” And Trump changed that: “I think we now say stuff. We fact-check him. We write it more powerfully that it’s false.”

This didn’t begin with Trump. For much of US history, the role of the news media–newspapers–in elections was obvious: newspapers should praise the party and the candidates they supported (who in turn supported the newspapers and their friends with advertising and with government jobs). That close connection between party and paper faded in the 20th century. Commercially successful newspapers, freed from dependence on party handouts, competed with other papers for economic advantage and hired reporters inspired by their new faith in a “scientific” approach to viewing the world (when they weren’t aspiring to write novels). By the 1930s and well into the 1960s, reporters tried to live up to an “objectivity” model of political reporting: describe a recent campaign event; quote the Republican candidate; quote the Democratic candidate; line up the who, what, when, and where; and leave the “why” alone or bury it deep in the story.

The New York Times newsroom 1942 by Marjory Collins – This image is available from the United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The New York Times newsroom 1942 by Marjory Collins – This image is available from the United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.In the sixties, journalists came increasingly to believe that this “he said, she said” would not suffice. They began to include analysis, interpretation, or context to explain the campaign—not to favor one candidate or another. By the 1970s they routinely ventured from what candidates said to why they said it. And propelled by Vietnam and Watergate, ambitious news organizations developed special assignment teams to do tough investigative projects, making “investigative reporting” a newly central ideal for American journalists (“muckraking” was not unknown, of course, but a willingness to assign resources to it was indeed novel in the Vietnam/Watergate years and has persisted ever since.)

Although journalists grew more assertive, they were still reluctant to say to politicians—“you lied.” But as early as 1969, right-wing organizations, and later left-wing ones, too, sought to hold politicians accountable by examining the factual claims they made. But at first no one claimed “fact-checking” to be a valid journalistic activity. Then, in 2003, factcheck.org was founded to evaluate the truthfulness of what candidates were saying on the 2004 campaign trail. When candidates tried to convert voters to their policies or viewpoints with fact-based (or presumably fact-based) statements, factcheck.org was on the job. Doing that job sometimes involved getting information the old-fashioned way – call up some experts and see what they had to say. Later on, fact-checking was made possible by the internet and the ready access to all kinds of data for any reporter with a computer, a laptop, or a smart phone and the convenience of a Google search.

Factcheck.org was followed by PolitiFact.com in 2007 and also a fact-checking column in the Washington Post in 2007 that became a permanent Washington Post feature in 2011. These developments led others around the country—indeed, around the world—to adopt fact-checking practices. The New York Times had eighteen staffers assigned to fact-checking during the first presidential debate this year.

So, how do unbiased organizations like the New York Times cover factuality-challenged candidates like Donald Trump? Journalists are now pushed to more boldly declare their informed and researched judgment about what is and is not factually correct. But telling readers what journalists conscientiously believe about the political rhetoric of the day was not born in 2016. Nor—strange but true—is it as old as the journalistic hills.

Feature image credit: News Media Standard by Sollok29. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The news media and the election appeared first on OUPblog.

The nothingness of hyper-normalisation

In recent years my academic work has revolved around the analysis of two main concepts: ‘hyper-democracy’ and ‘normality.’ The former in relation to the outburst of forms and tools of democratic engagement in a historical period defined by anti-political sentiment; the latter relating to the common cry of those disaffected democrats – ‘why can’t politicians just be normal?’ Not only are these topics rarely discussed in the same breadth, they are also hardly likely to form key elements of any primetime broadcasting schedule. But miracles do happen, and the highlight of past month was the broadcast of Adam Curtis’s latest documentary on the topic of ‘Hyper-Normalisation.’ But just like democratic politics, hope and excitement were quickly followed by dejection and despair.

Over the past decade thousands of University of Sheffield undergraduates have been intellectually nourished by the work of Adam Curtis, as his documentaries provide a wonderful way of grounding and understanding a range of historical themes and intellectual positions. The Trap: What Happened to Our Dream of Freedom (2007) is a fiercely acute and direct analysis of modern social development. It is not a comedy and the production style is raw and direct. The style is journalism as provocation as documentary. As AA Gill wrote in a recent review of Hyper-Normalisation ‘Curtis is a singular social montagist: no one else does his thing.’

But what exactly is ‘his thing’ and why does it matter?

To capture ‘his thing’ is to identify both an art form and an argument. The documentary art form is itself constantly evolving, with films embracing archive clips, interviews, aerial shots, advertisements embedded in a narrative that uses powerful sound effects to capture the raw emotion of the visual images. The viewer is almost ground down through a relentless over-stimulation of the senses in an attempt to make one simple argument: political elites will always try to impose a controlling ideology in their time, and the consequences of this has reached tragi-comic proportions. The existence of a dominant political ideology that controls and shapes the thoughts, beliefs, and actions of the masses lies at the root of Curtis’s art. He is a docu-revolutionary who holds firm to the belief that the world is shaped by big ideas, many of which need to be exorcised for the good of society. Curtis, as the exorcist, and with his films are the tool he uses to expose the existence of ideological forces that benefit the few and certainly not the many.

TV by Sven Scheuermeier. Public domain via Unsplash.

TV by Sven Scheuermeier. Public domain via Unsplash.In a world plagued by increasing forms of social, economic, cultural – even intellectual – homogeneity there must always be a place for those creative rebels like Curtis who possess a rare capacity for mapping out a broad historical and global terrain. His work is mischievous, deconstructive and endlessly creative, in many ways public service broadcasting at its most sublime and valuable. For a man that got his first job in television finding singing dogs for Esther Rantzen’s That’s Life in the 1980s, his professional journey is as remarkable as his films.

But I cannot help but wonder whether Adam Curtis may have fallen into a trap of his own making. Or, put slightly differently, if the style of the art is now limiting the substance in at least two ways. Hyper-Normalisation is an epic endeavor consisting of ten chapters spread over nearly three-hours of content. It covers forty years of nearly everything, everywhere. From artificial intelligence to suicide bombing, and from cyberspace to the LSD counterculture of the 1960s, everything is, for Curtis, part of a universe built upon trickery and plot. The problem is that the connections between the themes and events (the chapters) becomes ever more opaque and tenuous, the viewer understands that an argument is being made but the contours remain fuzzy and the detail unspecified. If topographically translated, then Hyper-Normalisation would be a map that outlined the highest mountains and the deepest seas, but little in between.

Whether the medium is blocking the message is one issue. A second is the normative content of the message. It is undeniably negative, almost nihilistic. It grinds and grates by offering a familiar tale of ideological control and hegemony, but little in terms of any understanding of how change may occur. The nothingness of hyper-normalisation is recounted but not challenged: ‘nothing to learn, nothing to make, no hope of change’ as AA Gill put it. Curtis may well retort that to expose is by definition to challenge and to some extent I would agree but the risk with a ‘Curtisian’ analysis as currently and consistently circulated is that it provides nothing in terms of charting a way out of the trap that it so insightfully exposes.

Featured image credit: camera by Steve Doyle. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post The nothingness of hyper-normalisation appeared first on OUPblog.

Make demagogues great again

This year’s eyebrow-raising, jaw-dropping American electoral campaign has evoked in some observers the memory of the ancient Roman Republic, especially as it neared its bloody end. Commentators have drawn parallels between Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump and Julius Caesar. That would be an insult – to Caesar. Can anyone imagine in Mr. Trump’s mouth the statesmanlike arguments Caesar is supposed to have used to try to convince the Roman Senate not to give in to anger and fear and inflict capital punishment illegally on Roman citizens? The hallmark of Mr. Trump’s campaign (at least until other problems emerged recently) has been the sheer anger it has exuded (and incited). So a more promising analogy from Roman history might therefore be the so-called popularis – roughly, ‘populist’ – ‘demagogues’ of the Late Republic.

Put off by Trump’s demonizing of Mexican immigrants as murderers and rapists, or his call to throw his chief competitor into prison? Consider this excerpt from a speech that the historian Sallust (Iug. 31), himself a retired ‘demagogue’ and a master of that style, attributes to a Roman tribune named Gaius Memmius before the assembly:

‘But who are these men who have seized control of the state? Hardened criminals with bloody hands and unquenchable greed, as vicious as they are arrogant! They have sold for profit their good faith, dignity and respect – everything honorable and dishonorable. Some of them have slaughtered tribunes of the people while others protect themselves by unjust prosecutions or unleashing massacres among you. The more evil they do, the more secure they are: they have made you afraid despite your apathy when they should be afraid because of their crimes.’

Memmius seems to surpass even Mr Trump in anger and truculence. Concitatio invidiae, or ‘arousal of indignation’, was the characteristic rhetorical mode of the Roman populist ‘demagogue’, usually a Tribune of the People seeking to stir Roman voters into action when he thought their leaders in the Senate were up to no good. In Memmius’ case, the problem was (allegedly) bribery of senators on a massive scale by a foreign king and its cover-up. The outrage is understandable, though the violence of the language is shocking, even irresponsible, to our ears.

After such a fusillade, did riot or massacre ensue? No. Memmius had, after all, told his audience ‘there is no need for violence, no need for secession.’ But the Senate, cowed, yielded to popular pressure and ordered the king to come to Rome to give evidence. Memmius won his point, but he could not have done so had he not mobilized the common people of Rome; and to do this he had to employ anger and indignation. After all, for the most part, people had better things to do than spend hours listening to speeches in the Forum, shouting outside the Senate-House, or standing in line all day to vote. Normally they seem to have accepted that senators, who devoted their lives ostensibly to serve the Republic, were the experts. But there was always room for doubt about what they were up to when you weren’t looking, or when they were outside the public gaze in their own (untelevised) meeting-chamber.

Bust of Cicero, Musei Capitolini, Rome, Half of 1st century AD by Glauco92. CC BY-SA 3.0 by Wikimedia Commons.

Bust of Cicero, Musei Capitolini, Rome, Half of 1st century AD by Glauco92. CC BY-SA 3.0 by Wikimedia Commons.Though Cicero was himself a master of their techniques, he hated populist ‘demagogues’. They pretended to be ‘friends of the people’ while exploiting the great power enjoyed by the people in the republican system to advance themselves at the expense of the Senate and ‘the good men’, whose power mostly resided in that institution. The criticism is not unlike that levelled at today’s populists. But it is inadequate, as a brief look at Cicero’s targets shows: men like the brothers Gracchi, whom Cicero attacks posthumously as divisive and hostile to the ‘good men’, or like Publius Clodius, Cicero’s own bête noire, who had sent him, the ‘savior of the Republic’, into exile. Yet the Gracchi had been killed by those ‘good men’ for championing the rights of ordinary citizens and restraining some excesses of the rich and powerful, and Clodius, the late Republic’s ‘bad boy’ politician who still gets pretty bad press from scholars, had sent Cicero into exile for blatantly violating Roman statute and long-standing constitutional norms by executing at least five Roman citizens without a formal – that is, a legal – trial.

Was Clodius wrong? Other ‘demagogues’ played a crucial role in correcting failed senatorial policies: getting rid of the aristocrats who kept losing costly battles against the Germanic invaders of the late second century and putting the gifted general Marius in charge; or devoting the necessary resources and appointing the best military man of the age, Gnaeus Pompey, to clean up the plague of piracy that had spread throughout the Mediterranean, raiding even Rome’s port at the mouth of the Tiber as Roman officials looked on. (Some might reply that these decisions by the people also hastened the Republic’s end, but that’s for another day.)

None of this would have happened if the ‘demagogues’ hadn’t made pests of themselves. Seen in this light, their outrage was a necessary ‘hook’ to mobilize the crowds needed to strike ‘the fear of the people’ into the Senate and the ‘powerful few’ (pauci potentes) who dominated its proceedings. As it happens, Memmius’s anger did not carry him far from the truth. He accuses those who dominate the Senate of slaughtering plebeian tribunes with impunity, plundering the treasury, accepting massive bribes from foreign potentates, usurping the law for their own ends, while shamelessly ‘parading before your eyes priesthoods, consulships, and triumphs, as if they held these things as an honor rather than as plunder.’ But he wasn’t exactly making it up. The Gracchi brothers, heroes to Roman plebeians, were indeed slaughtered, their bodies thrown into the Tiber like the city’s refuse.

Even the most upright provincial governors, like Cicero, could pocket an extraordinary sum from their ‘patriotic service’ – not to mention victorious commanders in war, who whatever the technicalities of the law could generally turn a handsome personal profit from the army’s plunder. Bribery of Roman officials by the subject peoples in the provinces seems to have been endemic– to prevent greater depredations that would otherwise be unleashed on them – and, since these same communities were also often cash-strapped, wealthy Romans were happy to finance it on extortionate terms … enforced by those very same Roman officials. And so on. Roman senators often richly deserved the indignation that was directed at them by populist ‘demagogues.’

So the Roman ‘demagogues’ encourage reflection on the nature of populism, ‘demagogy’, and the rhetoric of popular outrage, of which we have seen and heard a good deal this year, not only in the United States. These may not always be a bad thing, and we should take care not to taint with loaded terms every call to a normally quiescent citizenry to wake up and challenge ‘business as usual’. But Mr Trump has a lot less to be outraged about than did the Roman tribunes. And there is an important ethical difference between the kind of populist anger that is sharply trained on ‘political elites’, the ‘powerful few’, and that which Mr Trump so often directs against the less powerful – immigrants, legal or otherwise, foreigners in general, religious or racial minorities, and women – chiefly, it appears, to appeal to the resentment of white blue-collar and suburban voters, especially males, who fear that they have lost their former dominance.

Maybe it’s time to make demagogues great again.

Featured image credit: “The Gracchi” by Jean-Baptiste Claude Eugène Guillaume. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Make demagogues great again appeared first on OUPblog.

The World Bank: India’s development partner

Donald John Trump, the Republican Party candidate for the 2016 US presidential election, vowed a largely Indian origin gathering at a glitzy event in Edison, New Jersey, by declaring, “I am a big fan of Hindus and a big fan of India. If elected, the Indian and Hindu community would have a true friend at the White House… I look forward to working with Prime Minister Narendra Modi.” That was an endorsement that India matters in world politics, which was not so till a few decades ago. Indians living in the US would have hardly imagined such an admission, especially by a presidential candidate until the 1990s.

It is common knowledge that India and the US have always shared a lukewarm relationship till recently. Why this shift? Why does the US presidential candidate want to forge a new relationship with India? Admittedly, India is a democratic country like US. But it is one of the fastest growing economies in the world, and is one of the nuclear powers to reckon with. Does that explain the growing clout of India? One needs to look for a more convincing argument.

It is undeniable that India has been one of the main partners in the world economic operations and the World Bank (also known as the Bank). America, being the largest contributor to the funds of the Bank, has enormous influence in the functioning of the Bretton Woods Institutions (BWIs). The Bank has played a major role in transforming the Indian economy and the country’s emergence as a credit worthy nation. Like India-US relations, the journey of India and the Bank also had its ups and downs.

It is noted that the current situation evolved from skepticism to friendship with many a blips in between. Today, the relationship has matured, but the experience is worth recording. Both India and the Bank share the fundamental goal of achieving poverty reduction marked by sustainable growth. India’s relationship with the Bank has undergone different phases with unmistakable imprints of the world of political pulls and pressures.

The relationship strained in 1966 after the Indian economic crisis. The Bank’s diminished role after that lingered briefly in memory. But the timely aid from the Bank (under President Robert McNamara) soon revived and increased many-folds. Though this phase did last longer, mutual trust got some beating on different occasions. While the Indian government accepted the need for reform, suggested by economist Bernard R. Bell, the Bank’s pressure caused resentment in the rank and file of the Indian polity. During this period, the Indian political scenario was also undergoing many upheavals. That had its own reflections on the Banks policies towards India.

Narendra Modi, Chief Minister of Gujarat, India, speaks during the welcome lunch at the World Economic Forum’s India Economic Summit 2008 by World Economic Forum. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Narendra Modi, Chief Minister of Gujarat, India, speaks during the welcome lunch at the World Economic Forum’s India Economic Summit 2008 by World Economic Forum. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.The Bank’s presence in every sector was quite visible as well as the achievements. It introduced the structural adjustment policy in India in 1981 when loans were sought from BWIs owing to the second oil crisis and severe droughts across the country. Since the days of Jawaharlal Nehru to the 1980s, India was, arguably, among the most important bastions of third world dirigisme. Hence, this shift was a momentous development, and leading Bank economists reportedly celebrated it as among the “three most important events in the history of the 20th century”, alongside the collapse of the Soviet Union and China’s transition to “market reforms.”

Though reform has delivered growth; scholars, particularly having Left leanings, lashed out at the Government of India and in the States for creating conditions leading to sharp slashing of allocations to welfare schemes, cuts in subsidies, and the reduced role of the State in the economy. The Left wing politicians argued that the Bank and organizations owe allegiance to the rich counties and pushed their agenda, especially of the US. They were particularly harsh in lambasting the growing importance and role of MNCs in the Indian economy. Despite criticism, one visible trend was many Indian bureaucrats getting attractive assignments at Washington, and the Bank continuing to employ Indian academics and scientists.

While during the seventies and eighties, the Bank paid more emphasis on project and sector lending, after the nineties the Bank was focused more on the macro economics of India. After setting right a few macro-economic policies, in the mid-1990s, the Bank launched its new assistance strategy – policy-based lending to sub-national governments – to set right lopsided development across states with the national interest. The Bank loans triggered reforms in some reform-oriented states but not to the extent envisaged.

In 2004, after the results of the national elections, prodded by the Indian government, the Bank changed its approach further and made its adjustment lending available to lagging states too, to ensure inclusive growth. Through project, sector, and policy-based lending; technical advice; policy dialogue; and institutional building; the Bank has contributed to India’s economic development and policy changes. The objective of projects or adjustment lending in all these years has been alleviation of poverty, whose success is visible in the drastic reduction in the number of people living in conditions of utter poverty.

The Bank-India relationship had two major determinants: one, the ideological shifting of goals in Indian polity, and second, major upheavals in the economic scenario. The milestones are visible but the path has not been systematically traced thus far. The journey of the political economy of the Bank on the Indian soil is as interesting as the history of India’s economy itself. The process of opening the economy was surely a major turning point in this eventful, meandering, and at times tortuous journey.

Featured image credit: The World Bank Group Headquarters sign — in Washington, D.C by Victorgrigas. CC-BY-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The World Bank: India’s development partner appeared first on OUPblog.

November 5, 2016

On the cliché trail

The election campaign season licenses two cohorts—politicians and journalists—to take up an even greater share of public discourse than is normally allotted to them. Both of these groups have a demonstrable and statistically verifiable tendency towards cliché, and so it is to be expected that in what’s left of the run-up to the US elections, the public forum will be awash in clichés. And so it is!

Politicians

First, let’s look at the presidential candidates themselves. Like nearly all good politicians, both Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump are adept at speech patterns that make them agreeable to their supporters. Clichés, owing to their familiarity and frequency, are often used by politicians because they demonstrate the ability to relate to ordinary people on familiar ground.

Hillary Clinton is the more conventional candidate and she is also a conventional user of cliché. In her recent speech to the American Legion, she extols veterans because they “put their lives on the line” to protect “the greatest country on Earth.” She has “bedrock principles” and “feels passionately” about veterans’ access to healthcare. She thinks we have to “step up our game” regarding cyberattacks and she’s going to “work her heart out” to implement her plans. She introduces major statements with formulas like “Let’s be clear” and “Make no mistake” in the tradition of many politicians who have gone before her. Still, for all this, no one would argue that Clinton’s speech is mired in cliché; the small handful noted here in a speech of four thousand words is not at all excessive.

“Hillary Clinton” by Brett Weinstein. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

“Hillary Clinton” by Brett Weinstein. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.Trump’s speech habits have not escaped the notice of language pundits. He is repetitive, bombastic, and relatively limited in vocabulary, but for all that, he is not a frequent user of the expressions that we typically classify as clichés. One reason for this may be his simple speaking style. Many of the phrases that we think of as clichés are also idioms, so their meaning is not compositional—you can’t derive the whole meaning from the sum of the parts. Donald Trump is a rather plain talker and is not frequently given to flights of figurative language, a domain in which many a cliché reside.

Donald Trump is, however, a practitioner of one speech habit that has the whiff of cliché, and that is what I call modifier fatigue—the overly predictable use of certain modifiers and intensives. Modifier fatigue arises from the lockstep fashion in which speakers (or writers) choose a particular modifier in preference to any other that might be used, or in preference to no modifier at all. The modifier’s meaning is thus diluted, eventually to the point of meaninglessness.

Trump draws from a relatively small collection of intensifiers, despite his touted claim of knowing the “best words.” Trump is fond of intensifying with “so”—in fact, the only instances of “so” in his recent speech to the American Legion are intensives: he utters two instances of “so much,” a “so many,” a “so desperately,” and a “so important.” Another of Trump’s best words, apparently, is “best”: five times per thousand words for Trump, once per thousand words for Clinton in their speeches to the same group.

“Donald Trump” by Gage Skidmore. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

“Donald Trump” by Gage Skidmore. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.Trump also likes to characterize various phenomena as “incredible.” He does not seem to intend the word in the literal sense (“too extraordinary to be believed”) but rather in the informal, colloquial sense (“amazing, exceptional”) and nearly always in a positive way: he compliments the veterans’ commanders on having done “such an incredible job” and adds that we want our kids to learn the “incredible achievements of America’s history.”

If this short sampling does not seem adequate to account for the deluge of cliché in which we now flounder, it’s because I have not noted the main source: the journalists who cover the election.

Journalists

Journalism has long been the true home of the cliché, and in the forcing house of a presidential campaign, “no holds are barred!” “All the stops are pulled out!” “No stone is left unturned” in the journalistic enterprise of converting events of the day into formulaic boxes of comprehensibility. Cliché in TV and print journalism is currently so thick that that you can—well, I don’t even have to finish that one. You can test this for yourself by searching in Google News for co-occurrences of the candidates’ names with various tired expressions. Here are some of the rich pickings:

“Donald Trump Faces Uphill Battle in Battleground States” [ABC]

“A Clinton victory in Florida would make it virtually impossible for Trump to overcome her advantage in the race for 270 electoral votes” [Associated Press/Newsmax]

“The elephant in the room remains the very real threat to Fox News that may be set into motion if Donald Trump loses the election and starts his own network” [Politicus USA]

“The rebukes appeared to reach a crescendo Wednesday when Hillary Clinton called the EpiPen price hikes outrageous” [STAT]

“The anti-Trump Republicans with whom Clinton has curried favor won’t move the needle by much” [The Diamondback]

Is there an alternative to this mind-numbing reduction? Indeed there is, and it is laid out refreshingly in George Orwell’s timeless essay, “Politics and the English Language.”

A scrupulous writer, in every sentence that he writes, will ask himself at least four questions, thus: What am I trying to say? What words will express it? What image or idiom will make it clearer? Is this image fresh enough to have an effect? . . . But you are not obliged to go to all this trouble. You can shirk it by simply throwing your mind open and letting the ready-made phrases come crowding in. They will construct your sentences for you — even think your thoughts for you, to a certain extent — and at need they will perform the important service of partially concealing your meaning even from yourself.

Orwell’s advice notwithstanding, it doesn’t seem likely that the end of the election season will leave readers stranded, “high and dry,” with no clichés for comfort. We can look forward to learning that one candidate has achieved a “decisive,” “landslide,” or “resounding” victory, while the other suffers an “embarrassing,” “disastrous,” or “heartbreaking” defeat.

Featured image credit: trump and hillary on stage together by Paladin Justice. Public Domain via Flickr.

The post On the cliché trail appeared first on OUPblog.

Washington, Gates, and a battle for power in the young United States

Conspiracies are seldom what they are cracked up to be. It is in their nature for people to gossip and complain. Through it all they sometimes agree with each other, or pretend to for other reasons. Thus eavesdroppers looking for conspiracy can imagine plenty of it in almost any gathering, particularly if alcohol is lubricating and amplifying the discussions. So it was that in the winter of 1777-78 that some commonplace military griping got elevated to the level of conspiracy, at the center of which were a few hapless men later referred to as the “Conway Cabal.”

Congress appointed George Washington Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army in June 1775. This was after fighting broke out at Lexington and Concord and New England militia regiments besieged British forces in Boston. More or less at the same time they created the Continental Army by cobbling together some of the stronger New England militia regiments and federalizing them. Horatio Gates, who had earlier been an officer in the British Army, was appointed adjutant general to Washington, with the rank of brigadier. The Americanized Gates was a firm believer in republican and democratic ideals by this time. He had strong administrative and managerial skills that would serve Washington well over the coming months.

In the early part of the war, many still held out hope for a negotiated peace that would keep the colonies in the British Empire. Many in Britain, including many army officers, were actually sympathetic to the Americans and critical of their government’s treatment of them. But despite moderate views on both sides there was no turning back. The Americans declared their independence in the summer of 1776, and it was then Washington’s task to maintain it with an improvised army made up mostly of amateurs.

Washington’s skills were in military leadership, and his selection was designed to keep the army intact and the southern states committed to the cause. He was by nature a patient man, and his patience would be tested many times over the next few years. Like all men, he had some failings, but his strong points outweighed them.

Washington knew how to spot talent. He admired young Alexander Hamilton and regarded him like a son. When in 1777 the Marquis de Lafayette showed up to offer his services, Washington took him under his wing like a son as well. Both young men were only twenty years old. Washington was forty-five. Hamilton was appointed aide-de-camp in March of that year, having served bravely as an artillery officer in the fighting around New York City the previous year. He served as Washington’s aide for the next four years.

As the war ground on and Congress worked to create a functioning government of the fly, military men were appointed, promoted, transferred, and occasionally sacked. By the summer of 1777, Horatio Gates was no longer Washington’s adjunct, but instead was an aspiring field commander. Congress appointed Gates to replace Philip Schuyler as commander of the Northern Army in the summer of 1777. Schuyler’s faults were that he was (1) an Anglo-Dutch aristocrat from New York, and (2) the guy in charge when Fort Ticonderoga was captured by John Burgoyne’s invading British army from Canada. For these reasons, the New England regiments that made up most of the Continental portion of the Northern Army were not inclined to serve gladly under Schuyler. They were, on the other hand, delighted to serve under Gates, a Major General who had made a good impression on them in the fighting around Boston two years earlier.

Surrender of General Burgoyne by John Trumbull Gates is in the center, with arms outstretched via Wikimedia Commons

Surrender of General Burgoyne by John Trumbull Gates is in the center, with arms outstretched via Wikimedia CommonsGates was ambitious, and he harbored a common failing, an unrealistic assessment of his own capabilities. For its part, Congress made a few errors in its eagerness to maintain control while still getting things done. One such error was appointing Gates commander of the Northern Army without involving Washington, who was supposedly Commander-in-Chief. Washington’s patience saved him from blowing up at this affront, just as it did with many other affronts. However, Gates did nothing to improve the situation after the Battle of Freeman’s Farm south of Saratoga on September 19, 1777. The American army did well that day, and the scene was set for the decisive Battle of Bemis Heights that would come eighteen days later on the same ground. Gates sent his report of the first battle directly to John Hancock, President of Congress, deliberately bypassing Washington, who most people regarded as Gates’s immediate superior. The snub was just another test of Washington’s patience.

Washington had recently helped Gates by sending him Daniel Morgan and his Corps of Riflemen. Morgan’s men had performed well, and when Washington asked Gates to send them back, Gates was able to decline on grounds that Washington could not order him to do so. His letter to Washington does not contain the phrase “You are not the boss of me,” but an astute reader can find it between the lines. Washington had his critics, and Gates thought he saw an opportunity to replace Washington as Commander-in-Chief if things continued to go well in the North and if Washington was forced out.

Things did go well. Burgoyne surrendered his entire army to Gates on 17 October 1777, and the grumblers in the officer corps of the Continental Army began to mention Gates as a better option than Washington. Brigadier General Thomas Conway wrote letters criticizing both Washington and the course of the war. These were eventually forwarded to Congress. When the letters were made public, Washington’s supporters moved to counter them politically. Conway was compelled to resign from the army, and his friends were cowed. Gates eventually apologized for any appearance of impropriety he might have contributed to the scandal.

Those Continental Army officers that had grumbled most were later branded the “Conway Cabal,” but there is no evidence that there ever was an organized conspiracy. It was the only serious threat to Washington’s command during the course of the war, but Washington naturally worried that it might indicate something deeper and more serious. His continued outward patience through late 1777 and early 1778 suggests that he was not terribly worried. Part of that was his ability to hide his thoughts. However, we also now know much more about Washington’s talents as a spy master. His spy networks around New York and Philadelphia served him well. His ability to acquire good intelligence and to counter the British with planted disinformation did much to help the American war effort. It seems likely that he also knew much more about the activities of his critics than they realized at the time.

Featured image credit: American flag by tookapic. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Washington, Gates, and a battle for power in the young United States appeared first on OUPblog.

Hillary Clinton, feminism, and political language

Language is, of course, how we communicate political ideas to each other. But what is not often realized is that the language we use can itself be political. Often on the face of it, the way in which our language is structured — the words themselves or their denotations — are seen to betray no political significance. To be trite and quote Orwell, “Underneath this lies the half-conscious belief that language is a natural growth and not an instrument which we shape for our own purposes.”

Many feminists criticize the traditional idea that language is a neutral vessel that merely depicts reality, because, like Orwell (who was markedly not a feminist), they see language as a powerful, and undeniably political, tool that can easily be weaponized. And not just in the form of political name calling to damage an individual opponent’s reputation, like labelling an opponent “crooked,” but also in the ways language actually shapes reality. For example, words like “caring” or “bitchy” are used more often to describe women than men, thereby embedding in our social consciousness the notion that these are specifically feminine traits — and traits that are undesirable in our political leaders.

Deborah Cameron, a professor of linguistics at Oxford University, writes that “… societies are characterised by the incessant production of messages, images, and signs. To understand society therefore entails learning how to ‘read’ its cultural codes, its languages.” (Feminism and Linguistic Theory, 2nd ed., 1994) This can just as easily apply specifically to election campaigns. The American political system and its corresponding language from stump speeches to the Congressional floor is a realm designed of men, by men, and for men, and little has changed in that respect over the course of our 240-year history. The problem for women here is easy to see and captured nicely by Dee Dee Myers, Press Secretary during the Clinton Administration: “If male behavior is the norm, and women are always expected to act like men, we will never be as good at being men as men are.” Cameron goes on to assert that, “[language] is a powerful resource that the oppressor has appropriated, giving back only the shadow which women need to function in a patriarchal society. From this point of view it is crucial to reclaim [political] language for women.”

Democratic Presidential Candidate Hillary Clinton has proven herself adept at functioning within this masculine paradigm of politics, and can attribute most of her success today to that set of skills. She has

Who were Shakespeare’s collaborators?

The following is an extract from the General Introduction to the New Oxford Shakespeare, and looks at the many different playwrights, actors, and poets that collaborated with Shakespeare.

When we read Shakespeare’s Complete Works we are primarily, of course, reading Shakespeare. But as a bonus we also get, in the same volume, an excellent anthology of most of the important playwrights who were his collaborators. Shakespeare collaborated for the same reason that most people do: different members of the team are especially good at different tasks. The poet Alexander Pope, who edited Shakespeare’s plays in 1725, had no idea that Fletcher had wrote parts of All Is True, but we now know that the four passages he singled out as particular ‘beauties’, worthy of special attention, were all written by John Fletcher.

Shakespeare’s conversations with other writers and artists, the interweaving of his creativity with theirs, began in his own lifetime. His last three plays were all co-written with Fletcher – who, in all three, seems to have written more of the surviving text than Shakespeare. But Fletcher also wrote The Tamer Tamed, a sequel and reply to The Taming of the Shrew, in which we learn that Kate was never successfully tamed, and Petruccio’s second wife tames him; we know the two plays were performed together at court in 1633, and perhaps much earlier. Ben Jonson’s Sejanus was clearly a response to Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, but it also seems likely that the lost version of Sejanus performed by the King’s Men was a collaboration between the two men, just as Shakespeare’s ‘Let the bird of loudest lay’ was originally printed in a small collection of commissioned poems by several poets, including Jonson. Thomas Middleton, ‘our other Shakespeare’, was Shakespeare’s junior collaborator on Timon of Athens, but he also seems to have adapted four of Shakespeare’s plays between 1616 and 1623 (Titus Andronicus, Measure for Measure, All’s Well that Ends Well, and Macbeth). Middleton began the long historical tradition of adapting Shakespeare’s work to make it more suitable, and more interesting, for later audiences. But Middleton also wrote a reply, The Ghost of Lucrece, to Shakespeare’s Lucrece; an early owner bound the two poems together in a single volume.

Thomas Middleton. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Thomas Middleton. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Shakespeare was, and is, bound to many kinds of artist, not just poets and playwrights. In the last two decades of his career he was legally bound together with the other ‘sharers’ of a joint-stock company of actors. This means that Shakespeare created his characters for individual actors who would collaborate with him in performing the play. In fact, each actor received a separate manuscript, called a ‘part’, containing only the speeches of the character he was going to create, and a few words of his cues. From the beginning, each actor ‘owned’ his character.

Those actors literally embodied Shakespeare’s characters, by giving them a particular physique and a particular face. By comparison with most modern plays, Shakespeare’s scripts say almost nothing about the visual impression created by his characters, perhaps because he had already cast them in his mind, as he was writing them. Certainly, once we have seen a particular actor play a role we tend to think of the character in terms of that actor’s body, and especially that actor’s face , and modern playwrights often anticipate or imagine a particular actor as they are writing (Figure 000).

All his plays were written to be co-created by a team. But that team also changed over time, as actors like the star comedian William Kemp left, and new talents like Robert Armin and John Lowin arrived. Even if the actors remained the same, the spectators did not, in part because they were being influenced by other playwrights. Early in his career Shakespeare was competing with better-educated playwrights, most of them older than him, and with playwrights with more experience writing successful plays: Watson, Kyd, Greene, Peele, Lodge and Marlowe. He outlived them all, but by the late 1590s he was challenged, and new audience tastes were being shaped, by fashionable younger playwrights, beginning with Ben Jonson, George Chapman, and John Marston, soon followed by Thomas Middleton, then by Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher.

In the decade before 1594, when the Chamberlain’s Men was created, England’s infant theatre industry had gone through years of turmoil, with acting companies disintegrating, consolidating, and morphing rapidly and unpredictably. This was Europe’s first mass-entertainment industry, and like any new industry it went through a chaotic period of trial and error, erratic boom and bust. After such an apprenticeship, Shakespeare could never have expected a play to be performed, for any long period, by exactly the same cast.

Nor could he have expected his plays to be performed, always, in the same space, or for a stable loyal audience of predictably returning theatregoers. Shakespeare’s first experiences of new English plays would have been the many visits to Stratford-upon-Avon of actors on tour: between 1569 and 1587 he could have seen dozens of plays performed by all the country’s most important professional adult companies. Such touring in the ‘provinces’, away from London, continued to be a fundamental part of the theatre business throughout his working life. So did performances at court, for intellectually and financially elite audiences in spaces that were never designed for the convenience of actors. The plays he wrote for Elizabeth I continued to be revived after her death and the succession of King James I.

Shakespeare’s commercial success in his own time depended on his ability to write adaptable scripts: plays that would reward different actors and different kinds of audience, plays that would survive a weak performance or different interpretation by a new member of the cast, plays that did not depend upon a particular size or shape of stage, plays that could appeal to different political regimes. Adaptability was the secret to stability.

Shakespeare’s plays have continued to do for centuries what they did in his own lifetime: adapt to connect to an endless succession of new collaborators, new venues, and new audiences.

Featured image credit: Signature alleged to be William Shakespeare’s, found in a copy of Florio’s Montaigne in the early 19th century. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Who were Shakespeare’s collaborators? appeared first on OUPblog.

What are we asking when we ask why?

“Why? WHY?” If, like me, you have small children, you spend all day trying to answer this question. It’s not easy: sometimes there is no answer (a recent exchange: “Sharing is when you let someone else use your things.” “Why?”); sometimes you don’t know the answer; even when you do, your child isn’t satisfied, he just goes on to ask “why?” about the answer.

This follow-up why-question is worth pausing over. Suppose you were asked why the lights came on and you answered that the lights came on because you flipped the switch. When your child immediately follows-up with a “why?” his question is ambiguous. Is he asking: why did you flip the switch? Or is he asking: why is it that the lights went on because you flipped the switch? The second interpretation is a meta-question, equivalent to: why is what you said the answer to the original question? Now we’re in philosophical territory. Philosophy is concerned, not just with answering this or that why-question, but also with answering a meta-question about why-questions: what does it take for a proposition to be an answer to a why-question?

If we start with a small diet of examples there appears to be a clear pattern. Why did the bomb explode? Because someone lit the fuse. Why did the balloon pop? Because it hit a sharp branch. In these cases we have asked, of something that happened, why it happened; and in all of these cases the answer mentions a cause of that thing. This observed regularity suggests a hypothesis: you can answer a question of the form “why did such-and-such happen?” with “such-and-such happened because X” when, and only when, X describes a cause of that thing.

To test this hypothesis we need more data. One place to look is science. But science appears to casts doubt on it, for scientific answers to why-questions often seem to go beyond describing causes.

Do they really go beyond causes? Let’s look at a particular example. The spruce budworm lives in the forests of eastern Canada and eats the leaves of the balsam fir tree. Usually the budworm population is held in check, but occasionally the population explodes; when this happens the budworms can eat all the leaves and thus kill all the forest’s fir trees in about four years. Suppose the budworm population explodes; our question is: why did the population explode?

One response uses a mathematical model of the growth of the budworm population. The equation for the model, which describes how the budworm population X changes over time, is

dX/dt = rX(1-X/k)-X2/(1+X2).

There are two influences on number of budworms: reproduction, which increases the population — that is the term rX(1-X/k) in the equation; and predation by birds, which decreases it — that is the term -X2/(1+X2). The term r is the budworm’s “natural growth rate,” and k is the forest’s “carrying capacity” (the maximum number of budworms that the forest can sustain).

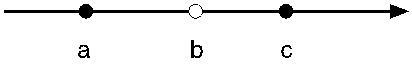

We can depict the information contained in this model on a line. The points on the line represent possible sizes of the budworm population. The points toward the left represent small sizes, the points toward the right, larger sizes. The solid circles are stable equilibrium points: the population quickly moves toward and stays near a stable point. The open circle is an unstable equilibrium point; the population moves away from it. So if the budworm population is smaller than point B, it will move toward (a); if the population is larger than (b), it will move toward (c) Before the population explosion, when the budworm population is relatively low, it is at (a). After the population explodes it is at (c). The question is, why did it jump to the higher point?

Figure 1. Created by and used with permission from the author.

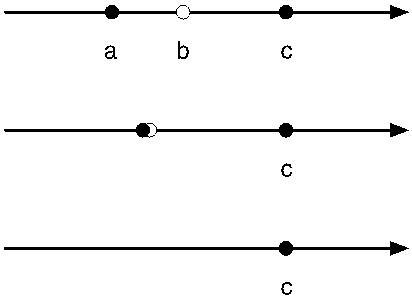

Figure 1. Created by and used with permission from the author.To answer we need to see how the positions of (a), (b), and (c) change as r, the natural growth rate, changes. The value of r goes up as the forest grows. And as r goes up (a) and (b) move toward each other, as in figure 2, until, at a certain value for r, they vanish. When that happens (c) becomes the only stable equilibrium, and the population it quickly increases to it — and the population explodes.

Figure 2. Created by and used with permission from the author.

Figure 2. Created by and used with permission from the author.I’ve answered the question of why the budworm population exploded. Now if everything I said is part of the answer, then the hypothesis I’ve been investigating, that “such-and-such happened because X” is true when and only when X describes a cause, is false. For the only relevant cause of the explosion is: the forest grew above a critical size. But I didn’t just say that this happened. I also wrote down a law governing the budworm population’s evolution. That law didn’t (couldn’t!) cause the budworm population to explode. If the law is part of the answer to the question of why the population exploded, then answers can do more than describe causes.

I, however, do not think that the law is part of the answer to the question of why the population exploded. I think that the answer consisted just in the fact that the forest grew big enough.

But how can this be? Doesn’t this mean that those paragraphs I wrote contain a bunch of information that is not part of the answer to the question of why the population exploded? Surely that can’t be. If you ask a question, and someone gives you a bunch of information that is not part of the answer, you will notice that they are changing the subject. But when I described the model of the budworm population it didn’t feel like I was changing the subject.

Responding to a question by providing information that is not part of the answer does not always feel like changing the subject. If I ask who came to the party and you respond “Jones did, I saw him there myself” you’re providing information that goes beyond the answer (which is just “Jones did”). But the extra information is relevant: in this case, it is your evidence for why your answer is correct.

That’s what I think is going on in the budworm example. If I just say that the budworm population exploded because the forest reached a certain size, you might well be skeptical: forests grow slowly, how can a small change in the forest size trigger such a huge change in the budworm population? The model shows how: when the forest grows above a certain size the low-population equilibrium state vanishes.

I’ve been defending a simple theory of answers to why-questions: the complete answer to “why did such-and-such happen?” lists the causes of that thing, and nothing else. But please don’t take this theory to say that scientists are wasting their time developing mathematical models, or searching for laws governing the phenomena they are interested in. The laws and models, while not parts of answers to questions about why things happened, are essential for coming to know that those answers are correct. In fact I think their role is even more exalted: they are essential for coming to know why those answers are correct. But that is a story for another time.

Featured image: Light Bulb by jniittymaa0. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post What are we asking when we ask why? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers