Oxford University Press's Blog, page 443

November 9, 2016

Prosperity for all: how to prevent financial crises

The Western World is emerging from the largest economic crisis since the Great Depression. Economic crises are terrible, painful events that affect us all. Sometimes they are accompanied by large and persistent long-term job losses as in the Great Depression of the 1930s or the Great Recession of 2006—2009. At other times they are accompanied by hyperinflations, as in Germany following World War I when prices increased by a factor of almost four million in the space of five months.

The human being in me is deeply disturbed by every crisis. The economist in me recognizes the invaluable opportunity that is provided by every crisis to disentangle one economic theory from another. Just as the astrophysicist learns by observing the explosion of a supernova, so the economist learns from observing the fallout from a major economic catastrophe. The Great Recession has both taught and reminded us that the existing economic theory that guides policymakers in treasuries and central banks is deeply flawed. It is time for a paradigm change.

The Great Depression led to a revolution in economic theory and to a change in policy. The theoretical revolution was initiated by the English economist John Maynard Keynes who, writing in 1936 in The General Theory of Employment Interest and Money, overturned the deeply held conviction that capitalist economies are self-stabilizing. To the contrary, he claimed a role for national treasuries and central banks to ensure that everyone who wanted to work would be able to find employment. His ideas were enshrined in the United States’ Employment Act of 1946, and they transformed the political landscape in ways that endure to this day.

Following the Great Depression, macroeconomics was dominated by Keynesian ideas. But in the 1960s and 1970s, western economies experienced stagflation: a period of high inflation and high unemployment at the same time. Stagflation was deeply subversive of Keynesian economics because, according to the textbook interpretation of Keynes’ ideas, an economy can experience high inflation or high unemployment, but not both.

Keynes caricature in Stalin-Wells Talk by David Low, 1934. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Keynes caricature in Stalin-Wells Talk by David Low, 1934. Public domain via Wikimedia CommonsFollowing the Great Stagflation of the 1970s, economists backtracked and revived the classical economic theory that dominated academic economics for a hundred and fifty years, beginning with Adam Smith in 1776, and culminating in the business cycle theory described by Keynes’s contemporary Arthur Pigou in his 1927 book, Industrial Fluctuations. That backtrack was a big mistake. It is time to realize that much—but not all—of Keynesian economics is correct. Capitalism is better than any other economic system yet devised for maintaining living standards for billions of people. But it is not perfect. We must redesign the rules under which markets operate to take advantage of what works and eliminate what does not.

Not every crisis is transformative, but some are. There have been four transformative crises in the last century. The first was the US financial panic of 1907. The second was the Great Depression of the 1930s. The third was the Great Stagflation of the 1970s, and the fourth is one we are only now emerging from: the Great Recession of 2006—2009. Each of the first three crises was associated either with a transformation in economic thought or with a transformation in economic policy. Some were associated with both.

The panic of 1907 was not the worst crisis to hit the US economy; there had been deeper and more persistent recessions in the nineteenth century, for example, the long depression of 1873 which lasted for 6 years. But the 1907 panic was the straw that broke the camel’s back, leading to the creation of the Federal Reserve System in 1913 and to the widespread acceptance of the government’s role in setting the price at which private banks can borrow and lend to each other.

Will the Great Recession be followed by a theoretical revolution or a policy innovation of the same magnitude as the upheavals of the panic of 1907, the Great Depression of the 1930s, and the stagflation of the 1970s? I believe so. Like its predecessors, the Great Recession is a transformative event that will lead both to a paradigm shift and to a fundamental change in economic policy.

The control of asset prices will seem like a bold step to some, but so did the control of the interest rates by the Open Market Committee of the Federal Reserve System when it was first introduced in 1913. We do not have to accept hyperinflations of the kind that occurred in 1920s Germany, nor should we be content with the 50% unemployment rates that plague young people in Greece today. By designing a new institution, based on the modern central bank, we can and must ensure prosperity for all.

Featured image credit: British business budget by PublicDomainPictures. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Prosperity for all: how to prevent financial crises appeared first on OUPblog.

AAR/SBL Annual Meeting survival guide

The American Academy of Religion/Society of Biblical Literature Annual Meeting is quickly approaching, and we couldn’t be more excited. This year, we thought we’d provide a survival guide of sorts, the “do”s and “don’t”s, from our perspective, for a successful AAR/SBL. Have anything to add? Let us know in the comments below.

Download the conference app.

Not only does the official app have information for each session, each exhibitor has a listing. Check out our listing for our location, relevant sessions by our authors, and a mobile coupon for use at the booth.

Bring your business cards.

It’s much easier to drop a business card in a raffle drawing than to fill out a slip by hand. It’s also easier for us to take orders if we can just staple on your card to our order form. (And you know you have a million business cards in your office, might as well put them to some use.)

Do your homework.

Do you have a book to propose? Do your homework! Check whether the press you’re approaching publishes in your area, and have examples of recent, similar books at the ready. Find out the name of the appropriate editor. And get in touch in advance: editors can engage with your project more fruitfully if they know something about it beforehand.

Tweet us.

We’ll be live tweeting from our brand new @OUPReligion Twitter channel and will be retweeting our favorite tweets that we’re tagged in. Take a selfie with your book! Take a selfie with someone else’s book! Tag us; we want to see. (And don’t forget to also use the official hashtag, #SBLAAR16.)

Ask us about exam copies.

Teaching a Religion course? You can request complimentary exam copies of our high-quality and affordable college textbooks at the booth. Just ask anyone in the booth for an exam copy request form.

Don’t ask us for directions.

Want to know where to find something? We’d love to help. But most of us spend all day in the Oxford booth and barely have enough energy to drag ourselves back to our hotels afterward. So we’d love to give you restaurant recommendations, or tell you where other presses are located, but if it’s not visible from booth 320, chances are we have no idea where it is.

The San Antonio River Walk by Pedro Szekely. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The San Antonio River Walk by Pedro Szekely. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.Please take the free journals.

The journals are free! Don’t leave the booth without one (or two, or three, or four, or…).

Stay for the last day.

Don’t leave before the last day of the conference! While there are no promises, most presses do sell off their books at a higher discount on the last day of the book exhibit.

“Remember the Alamo!”

Don’t get so caught up in the meeting that you forget to sight see. From our resident Texas native:

Be sure to stop for delicious, authentic Tex Mex on the Riverwalk.

Visit the Cathedral of San Fernando, one of the most beautiful churches in the city, in the evening to take in its beauty. It’s also the first church built in San Antonio and the oldest standing church in Texas.

If you explore the Alamo, take time to walk around the grounds, too. You’ll find entertainers, gorgeous gardens, and a lot of historical tidbits.

Visit us at booth 320 in San Antonio to browse our new and noteworthy books, journals, textbooks, Bibles, and online products. You can also use code AAR16 on our website to save 20% off books we’re bringing to the meeting and receive free shipping.

Featured image credit: Photo taken for Oxford University Press.

The post AAR/SBL Annual Meeting survival guide appeared first on OUPblog.

November 8, 2016

Where to eat in San Diego during SfN 2016

In just a few days, the Society for Neuroscience annual meeting will be kicking off in San Diego, California. I’ve had a number of homes in my 48 years; the most recent being the New York/New Jersey area for the last ten years as part of Oxford University Press. But the longest home, and the one I keep coming back to, is San Diego. The weather is perfect, the multi-cultural facets are inspiring, the local universities top-notch, and the food scene is divine. If you consider the relatively small geographic area surrounding the San Diego Convention Center where the conference will be held, you are pretty much guaranteed to find every type of food you could desire. And since the annual meeting will be bringing nearly 40,000 neuroscientists to the Gaslamp Quarter, being prepared and in the know will guarantee that you can try some outstanding restaurants.

(Relatively) New to the San Diego restaurant scene

For fans of Bravo’s Top Chef, Richard Blais (season 4) opened Juniper and Ivy in Little Italy (which is an enjoyable walk—or a faster taxi ride—from the Gaslamp Quarter). When I first went to this cavernous warehouse of a restaurant, I wasn’t sure how I felt, even though I found the food to be fantastic, as expected of Chef Blais’ techno-gastro style. But when I returned the following night, I was hooked: it is fun, vibrant, and an experience to behold.

Right around the corner, and newer to the San Diego restaurant scene is Herb & Wood by famed San Diego chef (and Top Chef season 3 contestant) Brian Malarkey. This large former furniture store is gorgeously decorated with a mix of warehouse style, comfortable fabrics, and stunning chandeliers to create a truly magical environment. And the food? Stunning! It’s a bit of east meets west via a bit of the UK if you ask me. Oh yeah, arrive early and have an old school cocktail! (But no driving folks: call a taxi or walk home!)

Little Italy

Before we leave the Little Italy part of San Diego, there are a couple of favorites that I would be remiss if I didn’t tell you about. Mimmo’s has fond memories for me, and that includes the food! The portions are huge and the service is on point but not pretentious, and I think that this is about as close to real Italian as you’ll find.

Although I’m not a fan of chain anything (hotels, restaurants, bars, etc.) that doesn’t mean that they are all bad and Davanti is amazing. If the weather is perfect (which it should be), sit outside (and if you get chilly, ask that they turn on one of the outdoor gas-heaters).

Old Town San Diego

But let’s switch gears and talk Mexican food shall we? If you have a car, and you see a small restaurant with one of the ubiquitous names like Hilberto’s (my favorite), Royberto’s, or Roberto’s to name a few, just stop. Don’t question, just stop. (But don’t tell me because I’ll be envious as I won’t have a car.)

Old Town Trolley — Old Town, San Diego, California by fabrice gille. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Old Town Trolley — Old Town, San Diego, California by fabrice gille. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.If you don’t have a car, there are still a few options that won’t let you down. Just hop on the trolley—the stop is right across from the convention center and at the bottom of the Gaslamp Quarter—and head north (south will take you to Tijuana) to Old Town. The go-to restaurant, albeit perhaps a tad touristy, is the Old Town Mexican Café. The food is classic and there’s nothing boundary-breaking because hey, you’ve come here for traditional Mexican food!

My other go-to, and admittedly my favourite for the food, the drinks, and the memories is Café Coyote. This restaurant is much smaller than many of other restaurants in Old Town, but the food is amazing and the staff is so helpful and wonderful that I often find myself sitting there eating more tortilla chips than I need, and having another margarita (that I probably shouldn’t have had either).

Old school San Diego

Two stand-out restaurants that have been around for quite some time are also within walking distance of the Gaslamp Quarter, albeit a healthy walk: Mister A’s and The Prado. But remember: “old school” often means “dress code” so be prepared.

Mister A’s is quintessential old school San Diego to me. Situated “up the hill” on the corner of 5th and Maple with views of Balboa Park to the east, Downtown (south), and the airport and ocean to the west, this is classic American cooking. With white table cloths, jacketed waiters, and menu items cooked “sous vide”, you will be in for a rare treat. But remember to make a reservation and dress appropriately.

Another classic San Diego restaurant is located in Balboa Park: the Prado at Balboa Park. Although the dress code here is not quite the same as it is at Mr A’s, you would certainly be well-served to be dressed appropriately. Enhanced with classic and warm décor, the Prado leans toward the Italian side of seafood cooking, with a refined touch. If you have the time, I would encourage you to stroll around Balboa Park before heading to the Prado for a pre-dinner cocktail. (A note of advice: although I recommend walking to many places, and you can certainly walk up to Balboa Park, I would not recommend walking back after your dinner as you may encounter some of the homeless population who have made the park their home.)

Can’t miss Gaslamp Quarter

If your day has been long and you just don’t want to venture too far, there are plenty of Gaslamp Quarter restaurants (and bars) that will meet your culinary needs.

My favourite Gaslamp restaurant that is still around is Bice. Bice is classic Italian dining at its best. Although their website says “fine dining”, which it is, don’t be afraid to arrive without a jacket: although preferred, it is not a requirement. The décor probably leans toward the “calitalian” side of things which I find relaxing and inviting. The homemade pasta is amazing and if they have burrata on the menu, grab it!

My other favourite, which also happens to be a Brian Malarkey restaurant (and I think, perhaps, his first in San Diego) is Searsucker. This is quintessential and unapologetic American cuisine and although now a chain, they still maintain the highest quality food and service. The wine list is outstanding and, arguably, one of the best in the city. Don’t be surprised to see a queue outside of the restaurant of people hoping to get in: make a reservation and this won’t happen to you.

We look forward to seeing you in San Diego during the Society for Neuroscience conference. Stop by our booth to explore some classic texts released as new editions, along with free copies of neuroscience’s top-ranked journals. Be sure to follow us on @OUPMedicine and stay updated during the conference with #SFN2016 and @Neurosci2016.

Featured image credit: Hotel del Coronado by nighowl. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Where to eat in San Diego during SfN 2016 appeared first on OUPblog.

What did Shakespeare write?

We have always known already that Shakespeare was a collaborator; he was a man of the theatre which is inherently a very collaborative, social art. The news is that he also collaborated as a writer much more than we used to think he did. We can now say with a high degree of certainty that upward of third of his plays were co-written in some sense or other.

In most film portrayals, Shakespeare seems to produce his plays in isolation, with the works torn from his soul and arising from his own personal experiences alone. When we realise he worked collaboratively, we see him quite differently – in a community that works together not only in putting the plays on, but also in writing them.

Evidence comes from a number of sources. Firstly, there is published evidence: the 1634 edition of The Two Noble Kinsmen states on its title page that the play was written ‘by William Shakespeare and John Fletcher.’

Secondly, we know the method was common practice at the time: we have very good records for the rival company, The Admiral’s Men, who used freelance writers working in teams to get a play done quite quickly.

Thirdly, we can tell from the text itself. In the mid-nineteenth century, scholarship examining the minutiae of the writing began to throw up the suspicion that some of the plays were in fact co-written. The main method used has been comparing the fine detail of different writers’ styles, by measuring the frequency of particular features, be it the frequency of certain words, or poetic traits such as feminine endings to verse lines, or certain kinds of prose style.

The things that were counted were things that was easy for a human to count. But that could only take the research so far. In the last 20 or 30 years this approach has been greatly enhanced by the availability of machines to do the counting. Whilst previous generations of researchers were assiduous in the work they did, they couldn’t aim at a comprehensive approach – no-one has the time to study all of the verse features or all of the rhyme schemes found in all of the writing of Shakespeare’s time.

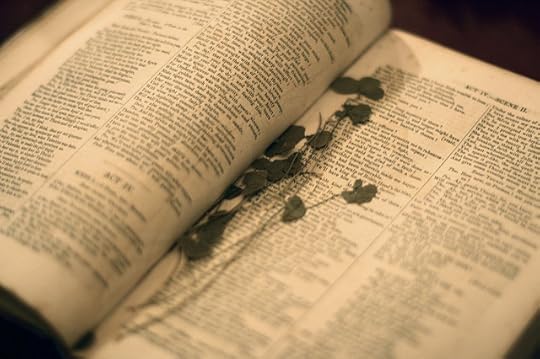

Untitled by Eflon. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

Untitled by Eflon. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.And it’s that kind of comprehensive approach that really enables one to examine Shakespeare in the context of a group of his contemporaries. For this type of analysis, we don’t want to treat him as ‘special’; we want to see if his style emerges from the other writers of the period as something distinctive that we can measure. To do that, we need to have a substantial body of the writing of the period available in digital form, and that has become true in the last 10 or 20 years.

The new machine-based approach – Computational Stylistics – has started to reveal some very startling facts. For example, it is now clear that Shakespeare’s vocabulary – the total body of all the different words he knew – was not exceptionally large (as has long been assumed) but rather was just typical for the period. We now know that a lot of words and phrases that we used to think were coined by Shakespeare were already in use by other writers before him. Wherever his genius lay, it was not in his vocabulary, but in his ways of combining existing words and phrases.

The computational approaches must be used with care, of course. The history of authorship attribution is full of cases of self-delusion in which an investigator discovered a new method, applied it, found that it seemed to confirm some existing beliefs about the text, and then the applied it elsewhere to produce a new set of ‘startling discoveries’ which later turned out not to be true. The worst case of this is Donald Foster’s SHAXICON database that was supposed to correlate Shakespeare’s roles as a performer with his choice of words for his next play after acting each role. It’s an interesting hypothesis – that learning a particular role for performance put certain words to the front of Shakespeare’s mind – but Foster was unable to prove it, and no-one else was able to replicate his claims, and the one attribution that Foster made by his methods, that A Funeral Elegy to William Peter is by Shakespeare, was soon disproved.

When addressing a particular question, the truly scientific approach is to have several independent studies, using different methods, working on the same texts. If they all come to the same conclusion by different methods and we cannot figure out how that might happen without the conclusion being true, then we can start to treat the conclusion as highly likely to be true. But if the studies do not agree, the question will become ‘why not?’ Has the discrepancy revealed unacknowledged investigator bias or something faulty with the methods? This is how science works: we have hypotheses, we devise experiments to test them, and we base our beliefs on the most plausible explanations that account for the results that we find. We should apply this kind of scientific rigour as much to humanistic study as anything else, since no matter what their fields everyone who undertakes research for a living is ultimately in pursuit of the truth, and these are the best ways we have for finding it.

Featured image credit: Front cover of William Shakespeare’s First Folio by Ben Sutherland. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post What did Shakespeare write? appeared first on OUPblog.

The problem of Gilbert and Sullivan performance materials

Most people would assume that, since Gilbert and Sullivan have been so widely renowned for so many years, the availability of satisfactory performance materials for their works would be a given. Nothing could be further from the truth.

The operas were produced at a time when the idea of copyright protection was only just beginning, and so the performance materials were jealously guarded by the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company. Over time, performance traditions gradually evolved, and by the time the operas were given new editions in the late 1920s, Sullivan had been dead for 25 years, and Gilbert for 15.

New vocal scores, libretti, and sets of band parts were commissioned, but without author input, the resulting materials naturally reflected then current performance practice, and bore significantly less relation to Gilbert and Sullivan’s intentions than the original materials. Those originals were already flawed in the way of such things, but the new materials were a good deal more so. Printed full scores were a rarity, and with conductors working from cued vocal scores there was no easy way to check the accuracy of the band parts.

Wind forward to today, and little has changed, except that performance traditions have evolved still further, and the band parts have gradually become more corrupted as they’ve been reprinted. For most of the Gilbert and Sullivan operas, the only parts available are still the D’Oyly Carte ones, either direct from the company library, or via reprinted editions such as Kalmus. The musical establishment has tended to be somewhat ‘snooty’ about Gilbert and Sullivan, and so in academic circles there has been a reluctance to address the issue.

That is gradually changing, with Broude Brothers in the USA embarking on a complete critical edition in the early 1990s, but so slowly that to date only Trial by Jury and HMS Pinafore have appeared. In 2000, OUP added a critical edition of Ruddigore edited by David Russell Hulme to the mix, and Dover has helped with reasonable full scores (but not parts) of HMS Pinafore, The Mikado, and The Pirates of Penzance. Now, OUP has added perhaps the finest of all the G&S collaborations with the publication of The Yeomen of the Guard.

In addition to returning as far as possible to the material as conceived by the authors, the preparation of a critical edition provides an opportunity to examine contemporary material which was cut from or rewritten for the original production. In the case of Yeomen, there are three complete songs in these categories, as well as various fragments.

Wilfred’s ‘When jealous torments rack my soul’ is a fabulous and highly unusual song. Gilbert wanted to cut it because he was worried about a supposedly comic work beginning with two solo numbers which were serious in tone, and Sullivan finally agreed 13 days prior to the opening night. Gilbert’s concerns might well have been justified in 1888, but since it plays an important musical role in the continuity of the whole, it is well worth including today.

Meryll’s ‘A laughing boy but yesterday’ is in a very different category from Wilfred’s song, because, far from being an integral part of the original plan, it was a relatively late addition. A cue-line was required (‘He’s a brave fellow, and bravest among brave fellows, and yet it seems but yesterday that he robbed the Lieutenant’s orchard’), which one can see hand-written into the prompt-book by Gilbert. It was then cut because Gilbert felt it was irrelevant, which is true, but it is a good song if not in the same league as Wilfred’s.

The original version of Is life a boon? is actually a rather wonderful song. It is a lot more florid than the final version, and has a very different second verse in the relative minor which necessitates an extra closing section to unite the verses/keys. An analysis of the lyric structure shows why this was a difficult song to set, and perhaps explains why Gilbert didn’t like Sullivan’s initial attempts.

These are just three examples of extra material which one might or might not wish to incorporate, but the central point remains that with the publication of this new critical edition of Yeomen, one more Gilbert and Sullivan work need no longer rely on the substandard materials which have been the only option for the past century. The new edition also offers a concert version which retains all the music but replaces the dialogue with a brief narration, and a reduced orchestration which allows for performances with as few as nine instrumentalists.

Featured image credit: Cover design from Yeomen of the Guard Vocal Score. (C) Oxford University Press. Do not reproduce without permission.

The post The problem of Gilbert and Sullivan performance materials appeared first on OUPblog.

November 7, 2016

Warren Buffett’s taxes: the more complicated narrative

In the second presidential debate, Donald Trump indicated that Warren Buffett had deducted, for federal income tax purposes, net operating losses in a manner similar to Trump’s deduction of his net operating losses. In response, Buffett, an outspoken supporter of Hillary Clinton, released a summary of Buffett’s 2015 federal tax return.

Buffett’s intended message was clear: Trump didn’t pay federal income taxes; I did.

However, the story revealed by Buffett’s tax data is more complicated than this simple narrative suggests. Buffett’s summary confirms his commendable generosity to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. In 2015, Buffett contributed an eye-popping $2.8 billion to the Gates Foundation, apparently in the form of appreciated shares of Berkshire Hathaway.

The data released by Buffett also confirm that Buffett has astutely minimized his federal income, estate, and gift tax obligations. Indeed, the data reflects the tension between Buffett’s outspoken support for federal taxation and his own aggressive avoidance of such taxation.

Buffett argues that America’s economically successful citizens should help to pay for the public services which facilitate their success:

“I was lucky enough to be born into a time and place where society values my talent, and gave me a good education to develop that talent, and set up the laws and the financial system to let me do what I love doing—and make a lot of money doing it. The least I can do is help pay for all that.”

Notwithstanding these sentiments, the data Buffett released indicate that he pays no federal capital gain tax on the appreciated Berkshire Hathaway shares which he transfers to the Gates Foundation.

Buffett’s intended message was clear: Trump didn’t pay federal income taxes; I did.

This is perfectly legal. But it deprives the Treasury of any federal income tax payment for the public services which, by Buffett’s own telling, helped create that appreciation.

Buffett’s transfers to the Gates Foundation similarly avoid federal estate and gift taxation since these transfers are fully deductible for purposes of the gift tax, and are thereby removed from Buffett’s estate tax-free. Buffett has supported Responsible Wealth, a lobbying effort to preserve the federal estate and gift taxes spearheaded by Bill Gates, Sr.

However, Buffett’s gifts to the Gates Foundation guarantees that Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway wealth will never be subject to federal estate or gift taxation. In terms of his personal generosity, these gifts and Buffett’s support of the Giving Pledge deserve the encomia they have received. However, the charitable contributions by Buffett and his fellow adherents to the Giving Pledge carry a hefty cost, namely, the federal estate and gift taxes these rich individuals avoid via their charitable contributions, contributions which deplete their respective estates tax-free.

I believe there is a need for limits on the federal estate and gift tax charitable deductions to assure that all large estates pay some federal estate tax. Buffett’s return data confirm the urgency of that proposal. Indeed, Buffett’s avoidance of all federal estate and gift taxes stands in sharp contrast to Secretary Clinton’s strong support for strengthening those taxes, as well as Buffett’s own statements advocating those taxes.

I hope that Buffett, the other Giving Pledgers, and the affluent supporters of Responsible Wealth will advocate amending the Internal Revenue Code to require their estates pay some federal estate tax even when these individuals leave wealth to charities. Just as the Internal Revenue Code requires a taxpayer to pay some federal income tax even if they devote all of their income to charity, the Code should, in similar fashion, require all large estates to pay some estate taxes.

In the meanwhile, Buffett, his fellow Giving Pledgers, and the supporters of Responsible Wealth can make voluntary payments to the federal Treasury to offset some or all of the federal income, estate, and gift taxes they avoid by their charitable transfers. Such voluntary contributions to the Treasury in lieu of taxes would indeed be, as Buffett says, “the least [he] can do.”

Featured image credit: President Barack Obama and Warren Buffett in the Oval Office, July 14, 2010 by Pete Souza. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Warren Buffett’s taxes: the more complicated narrative appeared first on OUPblog.

Hillary and history: how powerful women have been maligned through the ages

The 2016 United States presidential election has been perhaps the most contentious contest in recent history. Some of the gendered stereotypes deployed in it, however, are nothing new. Powerful and outspoken women have been maligned for thousands of years. Ancient authors considered the political arena to be the domain of men, and chastised women who came to power. Correspondingly, ancient Greek authors considered intelligence, courage, and outspokenness to be characteristics of men. Yet such traits were noted in women, women who were called masculine by some of the same authors.

In Greek tragedy, when Clytemnestra, the queen of Argos, killed her husband in revenge for his murder of their daughter, Iphigenia, her actions were called “monstrous.” Only a century later, Aristotle wrote that it was nobler for a man to take vengeance on his enemies than to reconcile with them. Aristotle was the tutor of Alexander III the Great, who followed Aristotle’s advice upon his accession to the throne of ancient Macedonia. He had those who rebelled against his authority, or, at least, were alleged to have done so, killed. Alexander’s “cleaning house” included the execution of his cousin, Amyntas. Alexander also achieved revenge for the Greeks, by avenging the Persian invasion of Greece some 150 years earlier with his own invasion and conquest of Persia. While Alexander would be called “the Great” for his exploits, his excessive use of force has raised the eyebrows of very few historians, and only recently at that.

Some six years after Alexander’s untimely death, his mother, Olympias, came to power as the regent for her grandson, Alexander IV. When Olympias killed her son’s alleged murderers in revenge, in addition to other enemies, she was not held to the same standard as Alexander had been. The historian Justin wrote that she had acted “more like a woman than a ruler.” Olympias has been gauged as instituting a reign of terror by ancient and modern historians alike, whereas her son was and is still called “the Great.” Both mother and son engaged in the same behavior: eliminating their rivals upon acceding to power. Yet history has judged them by different standards.

Hillary Clinton speaking at the Brown & Black Presidential Forum at Sheslow Auditorium at Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa, 11 January 2016. Photo by Gage Skidmore CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Hillary Clinton speaking at the Brown & Black Presidential Forum at Sheslow Auditorium at Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa, 11 January 2016. Photo by Gage Skidmore CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.The same can be said for the queens and kings of the Ptolemaic family. The Ptolemies became the rulers of Egypt after Alexander the Great’s conquest of that land. Ptolemaic queens became very powerful, and one in particular, Cleopatra VII, has left her mark emblazoned upon the ravages of time itself. Cleopatra VII took the same prerogatives as her male counterparts; she chose her own consorts, Julius Caesar and Marc Antony, and she eliminated several rivals who just happened to be her siblings, Arsinoë IV, a sister who had usurped Cleopatra’s throne and openly declared war upon her, and Ptolemy XIV, a younger brother who may have done so as well. Cleopatra had both of her siblings killed to preserve herself. Cleopatra’s actions were not unlike those of her male predecessors. Her ancestor, King Ptolemy IV, for example, killed his own brother, Magas, and his mother, Berenice II, upon his accession to the throne. He was then dominated by his mistress, Agathocleia, and her brother, as well as other unsavory ministers at whose hands he himself was killed. Cleopatra was a far more successful monarch in many respects. She was ultimately defeated by Augustus, but she managed to stave off the Romans, an invincible power, for seventeen years, whereas Ptolemy IV could not even stave off his own courtiers. Yet, instead of being given credit for her skills, Cleopatra is ‘diagnosed’ as having had “histrionic personality disorder with psychopathic tendencies.” Cleopatra’s sexuality lies at the center of such accusations. According to WebMD, one who has histrionic personality disorder may tend to “dress provocatively and/or exhibit inappropriately seductive or flirtatious behavior.” Was it inappropriate for Cleopatra to seduce Julius Caesar or Mark Antony to save her country from the onslaught of Roman legions? She is not recorded as having sexual encounters with any other than these two men, and each of her seductions began with political motives.

By the same token, was Cleopatra exhibiting tendencies of psychopathy when she ordered the death of her sister, Arsinoë IV, who had openly rebelled against her? Was Cleopatra demonstrating mental instability when she eliminated her brother Ptolemy XIV? Perhaps it would be better to simply note that Cleopatra killed Ptolemy XIV before he could attain majority and eliminate her. Cleopatra did the same things as countless other male monarchs. Yet she is still singled out as a psychopath rather than given credit for being a capable individual. Cleopatra was a woman in power, who knew how to stay in power.

While it may seem that we have advanced a million miles from the misogyny of our ancient counterparts, in some ways, nothing has changed at all. When Hilary Clinton used a private server for public business, or deleted emails from that server, she apparently did nothing that her male predecessors in previous administrations had not done. Yet she has been singled out as a “criminal,” whereas one never hears this of former male U.S. leaders who took similar actions. While I wish neither to condone nor criticize the actions of any U.S. presidential candidate, it is nonetheless important to insist, as November 8 approaches, that women in power no longer be treated by a double standard. As the world watches U.S. citizens cast their ballots, it is my hope that U.S. voters will bypass misogyny and make an informed choice.

Featured image credit: Painting of Cleopatra by John William Waterhouse, c.1887. Photo by Ángel M. Felicísimo. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Hillary and history: how powerful women have been maligned through the ages appeared first on OUPblog.

Lessons from the Song of Roland

What constitutes a person’s identity: family, country, religion? How do we resolve conflict: military action, strategy, negotiation? What turns a good man into a traitor? How different are we really from our enemies? These are all burning questions today, but they were equally urgent in the late eleventh century, as we see in the most famous Old French epic, the Song of Roland. Composed at the time of the First Crusade for a French-speaking audience in post-conquest England and continental France, the Roland tells of a heroic defeat turned into victory. Its eponymous hero dies for his family’s reputation, for his overlord Charlemagne, ruler of ‘sweet France’, and for his Christian God. But are his actions motivated more by self-interest (his reputation as a great warrior) or by altruism (the interests of France and Christendom)? Not all members of the French army agree with Roland’s thirst for revenge against the Saracens, who have previously killed Christian messengers, and after seven years on campaign in Spain, many Frenchmen are ready to return home. Roland, disgusted with the views of the doves, mischievously nominates his own stepfather Ganelon to negotiate with the Saracen foe. As a result, Ganelon becomes one of the most infamous of literary traitors, finding himself later in Dante’s Hell. He nominates Roland to lead Charlemagne’s rearguard, thus enabling the Saracens to kill the twelve peers (Charles’s greatest barons), including the emperor’s nephew at the battle of Rencesvals in the Pyrenees. This, however, occurs only after Roland’s companion-in-arms, Oliver, has tried to persuade him to call for reinforcements before joining battle, a suggestion Roland rejects as cowardly. Nevertheless, despite opposition to Roland’s reckless ideology from his fellow Frenchmen, he eventually does blow his famous ivory horn, attempts to destroy his trusty sword Durendal so that it does not fall into enemy hands, and dies a poignant death as a hero (scenes immortalised in the stained glass windows of Chartres Cathedral, and imitated countless times in literature and film down to the present day).

The rest of this tragic narrative involves Charlemagne’s revenge for Roland’s death, aided by divine intervention. He defeats a massive army of Muslims, whose martial, aristocratic characteristics resemble in many ways those of the Christians, and who differ from them only in religion, fundamental to the epic’s ideology, but in fact described (and understood) only superficially, or in the case of Islam, erroneously. In the final scenes, Charlemagne punishes Ganelon in the most gruesome of ways.

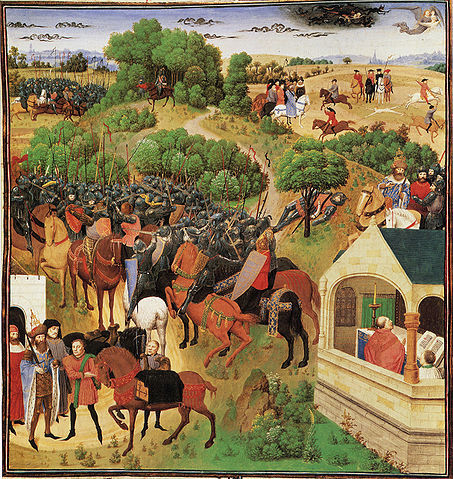

Image credit: Grandes chroniques Roland. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Grandes chroniques Roland. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.However, despite the Roland’s strong crusading propaganda many issues are left open for debate, suggesting parallels with our own troubled world. Can holy war ever be justified, particularly when human desires and emotions, such as jealousy, envy, and greed inevitably intervene? How different are opposing religions, or indeed races, from each other, however entrenched the ideological differences? As the Roland remarks wistfully of the strapping, handsome Saracen emir: ‘What a great warrior, if only he were a Christian!’ Troublingly, the lyricism of the poem’s celebration of military masculinity and its uncompromising patriotism are at times intensely moving, as are Roland’s distress at the sacrifice of his men and his own heroic self-sacrifice as he blows his iconic horn to recall Charlemagne, fatally rupturing his temples as he does so. The Roland is a perfect illustration of the power of epic poetry and rhetoric to sway opinion and stir emotion

Roland and Charlemagne are great heroes of French culture, yet the other two French epic poems we have translated present them in a surprising light. Both texts were composed after the Roland, probably in the twelfth century, but provide prequels to the battle of Rencesvals. In the Occitan (southern French) Daurel and Beton, Charlemagne betrays his sister for money, marrying her off to a treacherous and murderous baron who behaves with intense brutality. In the Journey of Charlemagne, he is prompted to travel abroad in order to disprove his wife’s suggestion that he is not the greatest ruler in the world. Thus women play a more significant role in the later works than the pagan queen in the Roland, who converts to Christianity, and Aude, who drops down dead at the news of her fiancé Roland’s death. Comedy, even parody, is the overriding tone in the Journey, especially when the French, after a drinking session, are overheard bragging outrageously about their sexual and martial prowess, and only divine intervention enables them to fulfil their boasts. What is more, Charlemagne proves to be superior to King Hugo the Strong of Constantinople only because he is taller, therefore wearing his crown higher! Thus, the medieval French were not averse to poking fun at their national hero and his acolytes, even questioning the propaganda coming out of St Denis that its holy relics had been fetched personally by Charlemagne from the Holy Land.

What these three medieval epics demonstrate is that medieval literature can be funny, dramatic, exciting, lyrical, self-questioning, and tragic. We may thus have more in common with medieval authors and audiences than we might think.

Featured image credit: Palais des Papes by Hans. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Lessons from the Song of Roland appeared first on OUPblog.

The good and bad of ghostwriting

I just found out that a scientist whom I greatly admire is writing his first book. Only he’s not. He’s hired a writer to do the heavy lifting. The hired writer’s name won’t appear on the cover. He’s signed on the dotted line in the invisible ink.

Ghostwriters don’t write about ghosts, but waft around in the background like them. Unlike real ghosts, such behind-the-scenes authors deal in reality, turning the ideas of ‘living’ authors into words for them to take credit for.

It’s a rapidly growing field. One that has the positive notions of bringing together disparate talents in an age of internet collaboration to create new projects, quicker, and the negative overtones of a scummy sense of dissimulation born of greed. Look at the debate over best-selling author James Patterson’s use of co-authors to fill his book publication queue more quickly.

The scientist author in this case had the idea for this book, and without this scientist, there would be no book, so his name should grace the cover. Yet, it feels questionable for readers to be sold an author’s name on the tin when there was a second chef doing all the stirring of the pot in the kitchen. Why not just put the other name in the small print, at least? For truth, if nothing else?

I’m certainly wondering now more than before how often this happens. If the use of ghostwriting is prevalent in the writing of science for the public, it seems to threaten the credibility of scientists known for their beautiful, profound, and inspiring words, of which there are now many. Might they be hiding ghosts?

The worst insult you can give a writer is to say their success was due to a ghostwriter, as recently happened to rapper Nicki Minaj. Just as her singing career is built on her lyrics, much of a career of a scientist can be built on the back of one or more prestigious books.

I really admire this scientist friend of mine. Love his science, love talking to him. So, with a distaste for ghosting in mind, imagine my surprise reaction to this news. My first thought when he said he was excited about hiring a writer was ‘why didn’t you pick me’! I shocked myself in thinking that. But the joy of being part of such a project really would be worth its weight in gold.

Of course, I’ve never thought about ghostwriting and he never thought of me that way, but the door was opened and I pushed on it and I suddenly got a very different view from the perspective of ghostwriters.

Maybe it can be a dream job.

Pen by fill. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

Pen by fill. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.I would happily be his anonymous ghostwriter.

Getting good science out to the public is a noble cause and fun. He’s a terrific guy. Ah, to write about important things you believe in deeply.

But then my mind jumped beyond scientists.

What if the ‘author’ were someone exceptional from another walk of life? A great sportswoman? A politician? A socialite. A social worker who changed the world? A refugee who made it to the top against all odds?

Now the role of ghostwriter comes into very different focus.

Some people are born with the ability to write, but lack ‘the story’. They can bust a pen like nobody’s business, but they haven’t lived the ‘life amazing’. Many great writers just haven’t been in the place to experience the life of deprivation, terror, ecstasy, or sheer luck that others have. With war rampant at all levels, whether countries, religions, or family members, we can all imagine what deprivation and terror looks like. In terms of ecstasy I’m thinking of being born with the looks to make you a supermodel, the strength to be an Olympian, or the brains to be a genius inventor. In terms of luck, I’m thinking about people who get hit by a meteorite and live to tell the tale, win the billion-dollar lottery, or marry a prince. Someone like the beautiful actress who married the prince of Monaco, Grace Kelly, did more than one amazing thing.

So what if you are a great writer, looking for a super story? Ghostwriting might just then look attractive.

It’s a symbiosis more than a parasitism.

The issue of this type of ghosting most recently came to the fore with the admission by Tony Schwartz that he ghosted Donald Trump’s book The Art of the Deal. Yes, Schwartz had an all-access pass to the life of one of the richest people and should have been the posterchild of the ‘fun’ of ghosting, but his experience and subsequent guilt about taking the money has led him to decry Trump as a sociopath unfit for presidency. Schwartz regrets his role today in magnifying Trump’s position of influence in the world and helping to write a book that put a reality TV show personality on the path to the presidency.

Yet, back to the romantic notion of ghosting. What about when ghosters really do find the right person?

I have completely shifted my feelings towards the idea of ever ghostwriting. For the right story, it could be the adventure of a lifetime.

If you are the right person, you know where to find me.

Featured image credit: Student typing by StartupStockPhotos. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post The good and bad of ghostwriting appeared first on OUPblog.

BHS is back

I wrote recently of the demise of department store retailer BHS as a high street presence in the UK. It is a moot point whether some of the pains that ultimately led to the demise of the business were self-inflicted. But what cannot be doubted is that the disappearance of BHS from high streets and shopping centres is a very salutary example of the huge structural shifts which are reshaping the retail industry today, and not just in the UK. BHS’s collapse also showed in stark terms how impossibly difficult life can become for retailers unable or unwilling to make fundamental changes in order to retain or re-establish their relevance to shoppers, especially the growing number of digitally enabled shoppers with previously unimaginable levels of access to brands, products, and price information.

And yet, just a couple of months later BHS is back! Well, sort of. Out of the wreckage of the old general merchandise store-based business, a very different type of BHS is trying to re-emerge – as an online only retailer. Instead of being an all-purpose general merchandise retailer, BHS.com will have a much edited merchandise assortment limited initially to just homewares and lighting – two categories where the old business had a particular strength with many shoppers. Other categories may be added later. BHS.com says it will be targeting a somewhat younger customer than the old business – logical given its online only orientation. And rather than 11,000 employees across its store network, BHS.com starts life with just 84. The new incarnation of BHS also has new owners – the highly diversified Almana Group in Qatar, pointing to the mobility of capital and ownership in the growing globalisation of the retail industry.

BHS Store in Brighton closing down by Gibboboy777. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

BHS Store in Brighton closing down by Gibboboy777. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Will BHS.com be a success? Of course, it really is much too early to say. But what is clear is that the new incarnation of BHS exhibits many of the features needed in the new landscape of retailing that the business in its previous incarnation so sadly and, ultimately, so disastrously lacked. It is digitally driven; it is more sharply focused on a specific customer type rather than trying to be all things to all shoppers (and, ultimately, not enough to anyone), and its product offer is heavily edited down to just a focused suite of specialty categories where the business has historic strengths. It also has the considerable benefit of being a well-known, if not always well-shopped, brand which a typical start up retailer doesn’t have. So certainly there are reasons to be at least cautiously optimistic. One further reason for optimism is that there may be an analogy with the great success that Shop Direct has had in taking a suite of redundant general merchandise retail brands and turning them into an effective, relevant, admired, and profitable set of online only retail businesses. In the Shop Direct portfolio a brand such as Littlewoods has been completely reinvented. Like BHS, Littlewoods had a strong presence of general merchandise stores on high streets and shopping centres across the UK. Today, those have all gone and a very tired ‘old retail’ business has been entirely reinvented as an internet only ‘new retail’ brand that is relevant again to the shoppers it is targeting.

The attempted rebirth of BHS as an internet only retailer does, however, illustrate too some of the big issues that happen when structural change is taking place to a sector on this scale. It seems inconceivable that BHS will ever again employ anything like the 11,000 employees it had when ‘old’ BHS stopped trading. In addition, while some of the old businesses 164 stores have been re-let or sold to other retailers, the majority have not and very likely never will be. Many urban centres are faced with the very considerable challenge of revitalising town centres against a backdrop of far less of the space in those centres being occupied by retailers as it once was.

Successful or not, the demise and rapid re-birth of BHS in a very different form is hugely and very poignantly emblematic of the very different retail landscape that this business is now trying to reinvent itself in.

Featured image credit: British Home Stores Closing Down Sale Wood Green by Philafrenzy. CC-BY-SA-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post BHS is back appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers