Oxford University Press's Blog, page 447

October 31, 2016

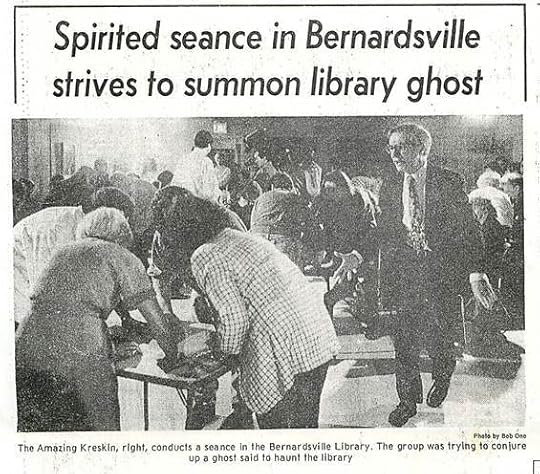

Specters in the stacks: Haunted libraries in the US

Some people love libraries so much, they never leave. Though no living human being knows exactly what happens—or doesn’t happen—after death, certain library patrons have reported unnatural, paranormal events occurring within the walls of these four supposedly haunted libraries. Could they be ghosts attempting to check out a new Sci-Fi novel or mischievously disrupting the organized stacks? Or are these sightings and sounds merely natural coincidences? We spoke to these four haunted libraries about their stories, and here’s what they had to say:

Saline County Library, Benton, Arkansas

Ashley Jones, Adult Programmer at the Saline County Library, is no stranger to spookiness in the library. The library, which had an old branch that was closed in 2002, was (and is) home to many a bewildering event. One story from the old branch concerns a painting of two women in rocking chairs on the library’s wall. On 29 January 1988, there was a fire in that building that closed the library until the middle of April of the same year. Everything but the painting and the area immediately around it burned. As one of Ashley’s coworkers puts it, the old branch was “filled with demons.” Many staff members remember hearing voices when they were alone; the old director heard a typewriter tapping when she was alone.

“Profound human interaction, the exchange of the ideas, the solving of problems and, at times, the breaking of bad news all took place here – reasons for residual energy, both good and bad.”

In a recent ghost hunt held at the current library branch, Ashley reveals, “I was here for the hunt and it was actually kind of creepy. We heard keys jingling, heavy boot steps, and a man talking. It was so real that I thought our maintenance man had come here trying to scare us and I was ready to fight.”

Some of Ashley’s experiences include seeing a woman with big, black bushy hair standing in the children’s section when she’s the first one in the building in the morning, and seeing the lower half of someone in a black skirt walking through the large print fiction area. There was no one else in that area. She will also hear people stomping up and down the stairs early in the morning later at night. The sound of chairs moving across the floor in the story time room, as well as books pages rustling, also accompany a day at work in the library. Books fall off the shelves occasionally. Ashley notes one comical story, saying, “Once I thought one of my coworkers spoke to me, I answered her, then asked her another question to have my office mate point out that no one was there but the two of us. Oddly enough, the spirit was talking about doughnuts.”

Willard Library, Evansville, Indiana

At 131 years old, Willard Library is the oldest public library building in the State of Indiana and until opening a new addition in 2015, had occupied the same 15,000 square foot building and retained much of its attendant Victorian trappings (original woodwork, tile work, high ceilings, and opulence). Greg Hager, Director of the Willard Library, notes that “Willard Library just looks like the kind of place built for housing a ghost.”

“Bernardsville Library 2” photo by Pat Kennedy-Grant. Used with permission.

“Bernardsville Library 2” photo by Pat Kennedy-Grant. Used with permission.The first reported encounter with the ghost who would become to be known as the Grey Lady occurred in early February 1937. It was the practice of the library’s custodian to come into the library at about 3am during the winter to stoke the coal-fired furnace and begin to get the building heated before it was time to open. He entered the basement and approached the furnace carrying his flashlight when he encountered a woman in a dress with a type of gauzy material over her face standing in front of the furnace. When he realized that the beam of his flashlight passed through her and illuminated the furnace behind her, he fled the basement.

This same custodian would go on to have frequent encounters with this unsettling apparition; in the words of the day, after the first sighting, he “took to drink.” Finally, he quit his job at Willard Library stating as his reason for leaving, always seeing that ghost and having nobody believe him. He is the only staff member to ever leave the employ of the library because of the ghost.

The most recent Grey Lady sighting involved two employees in the Children’s Department who, via a security camera in 2014, witnessed a woman in a Victorian dress standing at the basement door with her back to the camera as if she was looking out the window. The woman turned to face the camera and then disappeared slowly, in pieces like a jigsaw puzzle, from the head down, until she was gone. Both employees independently corroborated this story and stated that seeing her made them feel uneasy and unsettled. Other employees who have seen the famous ghost, state that she is accompanied by the strong smell of very cheap smelling perfume and they feel immense cold. Sightings typically last in the range of 10 seconds.

In 1995, Willard Library sponsored the first Grey Lady Ghost Tour, thinking it would be a fun, low key library program. That evening Greg stood in his office looking out the window at the 800 people lined-up outside. The one-hour program turned into a 5 hour event and spurred the library’s current offering of Ghost Tours that span weeks and attract thousands of people. The program remains the library’s most popular program event for adults.

Greg notes, however, that “while we are a haunted place, we are first and foremost a public library that serves the Evansville, Indiana area.” The library doesn’t conduct staff-led Ghost Tours year round and limits overnight paranormal investigations to one night per year. Though the Grey Lady is a sought-after apparition, the library staff is first and foremost concerned with serving the library patrons, which we and the Grey Lady can agree is a very important purpose.

“Bernardsville Library 3” photo by Pat Kennedy-Grant. Used with permission.

“Bernardsville Library 3” photo by Pat Kennedy-Grant. Used with permission.Bernardsville Library, Bernardsville, New Jersey:

It is believed a grieving ghost haunts the Bernardsville Library, unwilling to let go of her long lost love. Though the story has yet to be verified, it is believed that the ghosts of Phyllis Parker and Dr. Byram are responsible for the mysterious occurrences happening between the stacks.

In 1777, Dr. Byram, a traveling doctor, stopped at the Vealtown Tavern in Bernardsville to rest after a long journey, and quickly became acquainted with the tavern owner’s daughter, Phyllis Parker. The doctor remained at the tavern for an extended amount of time, and during his stay he courted the daughter, who fell madly in love with him.

One night, a group of soldiers in General George Washington’s army entered the tavern, charting out their next venture, when Dr. Byram quickly hurried to his room, then later left the tavern all together. The next day, the soldiers, realizing Dr. Byram was actually a spy for the British army, hunted and quickly captured him, bringing him before their commanding officer. Byram was exposed for who he really was: Mr. Aaron Wilde, a spy for the British army. Within one day, he was tried, convicted, and hanged.

The men returned his body in a coffin to the tavern owner, and gave the owner the full account of the story. Knowing this reality would crush his daughter, he placed the coffin in a back room to bury the next day, and told her nothing. Later that evening, Phyllis crept downstairs to the back room and pried the lid of the coffin off to behold her paramour lying lifeless in the box. She wailed with absolute despair, and never fully recovered from the heartbreak caused by his death, dying herself shortly thereafter.

“Throughout the years there have been sightings and feelings of other worldly beings in the Old Bernardsville Library,” says an employee of the library, “Maybe Phyllis, maybe not.”

In January 1977, the library took advantage of the interest in the ghost story and presented the Ghost Watch Ball on the 200th anniversary of the story. No sightings were reported, but the celebration was well enjoyed.

“Sacramento Public Library,” photo by Tracie Popma, showing books that randomly “fall off shelves.” Used with permission.

“Sacramento Public Library,” photo by Tracie Popma, showing books that randomly “fall off shelves.” Used with permission.Sacramento Public Library, Sacramento, California:

“Conjecturing as to why both spots are [haunted] isn’t hard,” explains James C. Scott, Information Services Librarian at the Sacramento Public Library. “The Special Collections rest within what would have been the reference room of the Main Library, built in 1917, and this spot was the information hub for one of the West Coast’s most vibrant cities.”

Though Scott himself questions the library’s supernatural state, as he has yet to experience any paranormal activity in the library since his employment there in 2000, a large amount of queries from patrons and other employees suggests something spooky is happening here.

“Over the years,” he goes on, “archival staff, particularly at night, have heard inexplicable banging and clanging coming from the room’s climate controlled vault, books – many several hundred years old – have randomly fallen off of shelves, and the glass doors enclosing several of the room’s stacks have been found opened in the morning after being closed the evening before.”

Still, it makes sense that lingering spirits would choose a library as their place of eternal residence. Scott commented, “Profound human interaction, the exchange of the ideas, the solving of problems and, at times, the breaking of bad news all took place here – reasons for residual energy, both good and bad.” The library has been and still remains a place of shared knowledge, ideas, and experiences, and would understandably continue to be a special place for people to congregate, those both living and dead.

At the Sacramento library, the Special Collections section hosts an annual haunted house (Haunted Stacks), whereby staff dress up as personalities from Sacramento’s past and speak about their untimely demise somewhere within the context of the city and counties’ rich history. Around 70 people attend each year.

Featured Image Credit: “Willard Library at Night” by Greg Hager. Photo courtesy of Willard Library. Used with permission.

The post Specters in the stacks: Haunted libraries in the US appeared first on OUPblog.

How much do you know about ancient ghosts, witches, and monsters?

From tales of Medusa’s wretched gaze turning men to stone to the cunning Sphinx torturing the city of Thebes, supernatural creatures and beings have long been a part of poems and children’s stories for centuries. Ghost stories, urban legends, and tales of frightening monsters still thrill us today. The ancient world was no different. The Greeks’ and Romans’ fears and superstitions informed their culture, and have long fascinated scholars intrigued by the extant corpus of mentions of witches, ghosts, and monsters in Greek and Roman literature.

Passed on through time by poets hoping to spin a tale that would chill their listeners to the bone, these imaginary creatures have a legacy deeply rooted in the annals of antiquity and continue to be reimagined in popular culture today. Like Hades himself, monster myths and ancient ghost stories have proven themselves immortal and show no signs of fading away.

In the quiz below, test your knowledge about the origins of these otherworldly and mythical beings. Some of this trivia may jump out and surprise you—don’t get scared!

Quiz background image credit: “Circe Offering the Cup to Odysseus” by John William Waterhouse. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Featured image credit: “Kadmos a drak” 560–550 BC. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post How much do you know about ancient ghosts, witches, and monsters? appeared first on OUPblog.

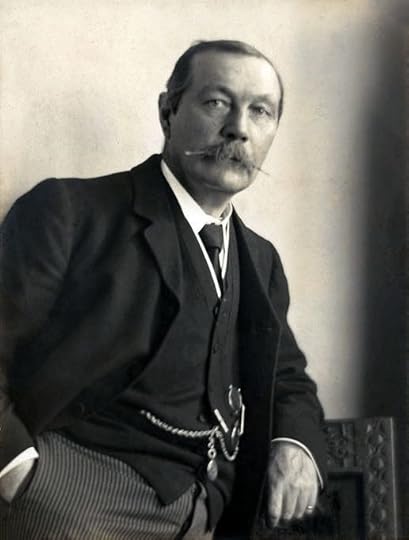

Arthur Conan Doyle: spirits in the material world

Sherlock Holmes is literature’s greatest rationalist; his faith in material reality is absolute. In his certainty, he resembles his creator; but not in his materialism. From the beginning of his writing career, Doyle was fascinated by the spirit world. One of his favourite literary modes, the Gothic, allowed him to explore the world of spirits and the supernatural, of vengeful mummies and predatory vampires, of ghosts and necromancers. This was territory forbidden to Holmes on principle. Doyle, a consummate genre professional, knew what his audience wanted in Holmes: brilliant readings of urban reality from the one man able to comprehend the complexities of the sprawling metropolis of London. ‘No ghosts need apply,’ as Holmes himself says in The Sussex Vampire (which is not a vampire story at all, but a tale of domestic poisoning). As Doyle himself became drawn ever more closely into the world of the paranormal, he became increasingly frustrated with Holmes. He tried to kill him off, of course, in The Final Problem, as early as 1893. But Doyle, of all people, should have known that death is not the end. ‘I believe that if I had never touched Holmes, who has tended to obscure my higher work, my position in literature would at present be a more commanding one’, he wrote in frustration in his 1924 autobiography.

Arthur Conan Doyle by Walter Benington, 1914. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Arthur Conan Doyle by Walter Benington, 1914. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.As a medic, Conan Doyle specialized in two distinct areas. After graduating from Edinburgh University in 1881, he returned to take an MD degree in 1885, writing a thesis on syphilis. In 1891, he went to study ophthalmology in Vienna, and briefly set up a practice in London as an ophthalmic surgeon. Both of these specialisms have resonances for his fiction. His sense of the body politic as diseased and corrupt – articulated in Dr. Watson’s vision of London as ‘that great cesspool into which all the loungers and idlers of empire are irresistibly drained’ – is in part a product of his professional knowledge. In one of his most disturbing medical tales, The Third Generation, an aristocrat on the eve of his wedding discovers that he suffers from hereditary syphilis, initially contracted by his dissolute grandfather, which he will inevitably pass on to his wife and his children. He throws himself under a carriage.

Doyle’s interest in ophthalmology feeds into Holmes’s genius for observation, but also into a lifelong interest in photography. As a young man in the 1880s, he wrote a series of articles for the British Journal of Photography, largely recounting photographic expeditions in Africa and in Ireland. He was convinced of the absolute reality of the photograph. This was to cause him serious problems in the early 1920s, when he attracted derision in some quarters for his uncompromising belief in the veracity of the ‘Cottingley Fairies’ photographs. These were photographs, Doyle seemed to think; they simply had to be real.

Even more than this, of course, Doyle wanted to believe that they were real. Although he had been interested for years – had been attending seances, writing supernatural tales, and joined the Society for Psychical Research – in 1918 he finally came out publicly as a spiritualist, with the publication of The New Revelation. He flung himself into this cause as he had into all others, and spiritualism became the governing idea of the last decade of his life: he wrote The Vital Message (1919), The Coming of the Fairies (1921), the monumental two-volume History of Spiritualism (1926), the spiritualist adventure The Land of Mist (1926), the extraordinary account of his own relationship with his personal spirit guide Pheneas Speaks (1927), and several others. For many, these were a library of credulity: Arthur Conan Doyle was a crank.

My own sense of this is more nuanced, and much more sympathetic to Doyle. Like very many others, he suffered agonizing losses during the First World War. When the War broke out, Doyle did what he always did: he propagandized like mad in the name of the British Empire. His history of The British Campaign in France and Flanders (1916-20) runs to six thick volumes. But their stolid dark blue covers conceal what was for Doyle an unbearable personal tragedy. His son Kingsley died from pneumonia after being wounded in action in 1918. His beloved younger brother Innes died in the influenza pandemic that followed the War. Spiritualism taught the belief in the survival of the human personality after death. It taught that the dead were still with us, unchanged in their essence, still caring about us. Love survived the grave, and even survived the War. ‘The body,’ he wrote in 1919, ‘is a perfect thing. This is a matter of consequence when many of our heroes have been mutilated in wars. One cannot mutilate the etheric body, and it always remains intact.’ The next world, Doyle believed, ‘is a place of joy and laughter’. Our world, the world of secular materialism, which Holmes inhabits and interprets, is a horrifying place, an inexorable parade of grief and mutilation. Who would want to live here?

Featured image credit: Spooky tree by Jason Bowler. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Arthur Conan Doyle: spirits in the material world appeared first on OUPblog.

Why the UK must welcome the young people from Calais

The UK government has wanted to leave to their dramatic fate children, teenagers, refugees and migrants who find themselves in Calais and elsewhere in Europe. This is true even of those minors with relatives in the UK, with a legal right to enter the country. The callousness and abdication of responsibility of this stance has been opposed by many, with limited practical success, even when Parliament has clearly expressed the will of having the British borders open to at least some vulnerable children.

To much fanfare, a dozen children (legally meaning a person under 18) were finally allowed to cross the Channel on Monday 17 October to be reunited with members of their families. As the same paltry number of children arrived the next day, an uproar was started by the likes of David Davies MP and Nigel Farage, which the tabloid press was more than happy to relay. The suggestion was that some arrivals were actually adults, as they did not look like teenagers. There was a call for these young men to be subjected to dental X-ray.

This must be resisted. We must keep in mind and re-affirm what scientists have long been saying: dental x-rays and other physical examinations cannot determine age.

First thing first. Part of the reason why the age of these young people is unknown is linked to the fact that the birth of one in three children goes unregistered worldwide. Non registration is particularly prevalent in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. Those who start their travels with official documents often lose them in the course of their long and perilous journey. Even if a document bearing a date of birth survives the journey, the authorities at arrival may question either its validity or the fact that it really belongs to its holder.

It therefore has to be accepted as a fact of life that many young people just cannot prove their age. It should also come as no surprise that minors who have travelled the world alone and experienced things that one would not wish on one’s children’s worst enemy, may look substantially older than they are.

It should also come as no surprise that minors who have travelled the world alone and experienced things that one would not wish on one’s children’s worst enemy, may look substantially older than they are.

People often think that, in an era where technological developments have defied the imagination of what would have been thought possible a generation or two ago, it should be possible to resort to scientific methods, such as x-rays, for determining age. This is a mistaken view: age cannot be specifically determined by physical examination. The reason for this is simple: people do not physically develop at the same rate within one population, let alone across ethnic groups. A multitude of factors, such as genetic inheritance, nutritional intake, environment, health and illnesses, influence individual development.

Neither skeletal X-rays of the hand and wrist, nor dental X-rays, nor bone development imaging, nor height or testicular volume for men, or measurement of any other part of the body, can specifically answer the question ‘how old is this person?’ Teenagers grow, acquire bone and tooth maturity, and develop sexually, at hugely different rates. What can be known is the range of ages compatible with a given measurement – but not the age of a person who presents certain measures.

Within a given population, 5% of normal boys aged 14 have heights above the average adult height. Some 15 year olds have wisdom teeth showing, even though these generally appear later. Once it is determined that an individual is physically mature because four (for boys) or five (for girls) indicators are all satisfied, this still need not mean the individual is over 18; they might be as young as 15.

In other words, physical examinations, however sophisticated and precise, are not a dependable age indicator. In the UK, medical professional bodies have ceaselessly highlighted the danger of wishing to ascribe adult age to individuals on the basis of developmental maturity. Their determination and clarity have successfully thwarted British government proposals, for example in 2009 and 2012, to introduce X-rays for age determination process.

Their opposition is based not only on medical and statistical grounds, but also on ethical considerations. Medical ethics give prominence to the principles of respect for autonomy and beneficence. In this case, not only is it difficult to think the young person would be in a position to give informed consent to the procedure, but X-rays would be used purely for government’s administrative convenience, without therapeutic benefit and indeed with potential harm such as an increased risk of brain tumour.

In the UK, official policy recognises that it would be wrong to assess age on the basis of physical appearance.

In the UK, official policy recognises that it would be wrong to assess age on the basis of physical appearance. This stance should continue. Although far from perfect the policy is that social workers perform a ‘holistic’ assessment to determine age if there are reasons to dispute the age the young person claims to be. This holistic assessment combines observations of physical appearance and social development with the taking of a family and educational history, and whatever else might be considered relevant.

This method is far from perfect, but it is better than subjecting young people to dental x-rays or getting a young man to undress so as to match the size of his testicles to one ball in a chain of balls of increasing size. Does one really need to point out that such a method, still practiced in Slovenia and possibly elsewhere, is demeaning and humiliating and fails to show respect for dignity and privacy? Of course, it is not even a reliable method to determine the biological age of the person subjected to it.

We are facing a humanitarian crisis in Calais that requires urgent action. This action must take the form of welcome. This is not the time to talk about introducing age assessment methods that do not work.

This post was originally published on the When Human Rights Become Migrants blog.

Featured image credit: ‘The White Cliffs of Dover’ by Immanuel Giel. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Why the UK must welcome the young people from Calais appeared first on OUPblog.

October 30, 2016

It’s beginning to look a lot like October: Breast Cancer Awareness Month & policymaking

October is National Breast Cancer Awareness Month and pink is everywhere. Panera Bread is promoting a Pink Ribbon Bagel, Staples is selling pink Uniball pens, and Dick’s sporting goods is offering pink tennis balls. Even government can get into the spirit. In 2009, the Obama Administration wrapped the White House in a giant pink ribbon while, this year, the Winder (GA) Police Department painted one of its patrol cars pink. It’s hard not to notice all of the pink. And that’s the point.

Corporate-connected activists have branded breast cancer as pink—feminine, hopeful, and uncontroversial. They worked with businesses to sponsor walks and runs and to create cause-marketing products (like the bagels) to raise awareness of and money for breast cancer. They have been wildly successful. Americans see pink products at the store on everything from yogurt to socks. They buy these products and, when they bring them into their homes, the message of breast cancer as pink is reinforced while eating breakfast and getting dressed.

These messages have changed the way Americans think about breast cancer. We’ve come a long way from the 1980s, when breast cancer was a stigmatized disease and not openly discussed, when local newspapers wouldn’t print the word ‘breast’ in their stories, and when women avoided seeing their doctors or getting second opinions on painful lumps. Today, more Americans know the pink ribbon is the symbol of breast cancer than the name of the vice president. They are more likely to identify the organization that created cause-marketing campaigns as a funder of breast cancer research than the National Institutes of Health.

But for all of the benefits it provides, raising awareness of breast cancer as pink also comes at a cost. Although nobody wants more breast cancer, there are deep divisions within the breast cancer community about what breast cancer is, how best to solve the problems associated with breast cancer, and what it means to have the disease. Pink framing—publicly promoted in walks and runs and in supermarkets and shopping malls across the country—however, forms an umbrella over men and women who have breast cancer, and activists and organizations who work to address the disease, whether they agree with it or not. Many activists dislike the association of breast cancer with pink, because they believe the disease isn’t soft and sweet—it’s difficult, painful, and sometimes deadly. According to one group, “Cancer Sucks.”

But for all of the benefits it provides, raising awareness of breast cancer as pink also comes at a cost.

Contrary to the walks, runs, and cause marketing there are a wide variety of solutions that activists propose. Some want to go to Congress and ask for money for research on breast cancer, for healthcare to cover treatment, and for more stringent regulations on the known causes of cancer. Others want to take to the street and protest corporations that put carcinogens in air, water, and commercial products. But it is hard to advocate for alternative solutions when policymakers wear pink ribbons as a sign of support and when corporations promote their good deeds on the packages of their products.

So, now that it is October, what should we know about breast cancer? We should know that breast cancer affects both women and men, though it is far more common in women; that breast cancer deaths have been declining over the past two decades; that African American women have the highest mortality rates; and that the gap between African Americans’ and white women’s mortality is growing.

And what is the best way to address the problems associated with breast cancer? Should we skip the walks and runs and avoid the pink products? I don’t think the solution is so easy. Breast cancer, like cancer more generally, is a complex disease that can have a significant impact on men and women who are diagnosed as well as their families, friends, and communities. People do get individual benefits when they get involved, from feeling solidarity with others at walks and runs to feeling good about buying pink products. We can’t dismiss these experiences.

At the same time, however, there are other ways to get involved too. We can give money to national nonprofits or to local support groups, which focus on everything from research, to treatment, to various kinds of support. We can get informed by reading about breast cancer or by signing up for trainings. We can be involved through advocacy, political protest, and volunteering formally or informally in our communities.

Breast cancer is many things, including pink. But it isn’t just that.

Featured image credit: October pink brease cancer by waldryano. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post It’s beginning to look a lot like October: Breast Cancer Awareness Month & policymaking appeared first on OUPblog.

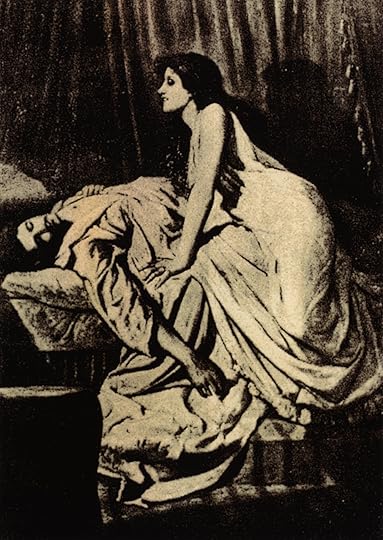

Vampire awareness in October 2016

When Best Buy, the American multinational consumer electronics corporation, declared 30 October 2008 “National Vampire Awareness Day,” they were cannily exploiting a metaphor that, within Western culture at least, was over 200 years old. Here, though, the vampires to be arrested, staked, and vanquished were not the suave, velvet-cloaked aristocrats of Old-World Europe, but the electronics and electrical appliances of the ordinary, modern-American home: while suburbia relaxed and slumbered in blissful ignorance, its computers, microwaves, plasma TVs, DVD players, cameras, and cell phones—all consumer goods peddled by the Best Buy corporation itself—were draining the nation of its electrical power. Silently infiltrating the domestic realm, these vampires had rendered the home ‘unhomely,’ unleashing a dreadful force in suburban America that made “a trip to Transylvania” seem like a “tiptoe through the tulips.” The YouTube video has all the irony and self-consciousness of a low-grade horror movie about it:

With electricity figured as the life-force and the “standby-mode” as the sign of the undead, the campaign was a call to urgent action: to prevent these “creepy suckers” from “striking you where it hurts the most—your wallet,” appliances and their chargers were to be unplugged, disconnected, and “defanged,” “phantom loads” carefully scrutinized, gauged, and conserved. As in so many fictional and filmic vampire narratives, excessive consumption was the mark of monstrosity, economic prudence and parsimony the sign of the human, but whereas, in Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897), technology had proved the most reliable of vampiric deterrents, here it had turned alarmingly monstrous.

Philip Burne-Jones, The Vampire, 1897. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Philip Burne-Jones, The Vampire, 1897. Public domain via Wikimedia CommonsEven in the support that it purported to offer for the conservation of electrical and financial resource, Best Buy’s strategy ultimately remained one for the promotion of further consumption: “forget the garlic,” it urged, and visit your nearest store for further information and advice— or at least another appliance and a vampire-repellent Best Buy Power-Strip to accompany it! No “pesky fiend” but the naked monster of corporate capitalism, a bitterly ironic return of the vampire of bourgeois consumerism as metaphorically figured by Karl Marx in Capital: Critique of Political Economy (1867‒1883). Though well attuned to the irony, a number of fringe eco-awareness groups, including the online Green Living Guide, Ecorazzi, and , welcomed the move.

Unsurprisingly, though, and despite calls for its reinstatement on Ecocentric and in The Huffington Post in 2010, it is fair to say that National Vampire Awareness Day has not become the commemorative occasion that its devisers, in however playful a manner, intended it to be. Nonetheless, the very fact of its undead existence in the annals of consumer and internet history provokes what, at first glance, appears to be a very simple question: other than their centrality to the Halloween celebrations of the day after, “What does it mean to be aware of vampires on 30 October 2016?”

For the marketing team at Best Buy in 2008, vampiric awareness meant being mindful, vigilant, and forever on one’s guard against the draining effects of these unwelcome intruders. Here, the campaign deployed the cultural mythology of vampirism that, though of earlier provenance, had been popularized in the fictions of John Polidori, Sheridan Le Fanu, James Malcolm Rymer, Elizabeth Braddon, and Bram Stoker in nineteenth-century Britain, and tirelessly reiterated in global horror literature and cinema ever since.

Ernst Stöhr, Vampir, 1899. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Ernst Stöhr, Vampir, 1899. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.A figure of absolute “Otherness,” be it the otherness of race, class, sexuality, nationality, or gender, the vampire was that which crossed the sacred threshold of the home, the body, the self, or the nation, wreaking havoc therein and contaminating all who dwelt there with its insatiable appetites, lusts, and desires. Although, like the electronic goods of Best Buy, the vampire was said to enter into these cherished spaces of the familiar only upon the acceptance of an invitation, the vampiric guest worked stealthily to undermine and displace the mastery of the human host, subjecting him or her to the part-painful, part-pleasurable consequences of parasitism. Vampirism in the Victorian period, as now, was primarily conceptualized as the perversion of the spirit of national hospitality. Such dangers, it was claimed, could only be eliminated by ruthless eradication: expelled, staked, burned, and decapitated, the monster was rendered functional in the reassertion of white, heteronormative, middle-class conservatism.

The effect of such progressive Anglo-American agendas as second-wave feminism, Gay Liberation, and the Civil Rights movement from the 1960s onwards was surely to challenge the firm distinctions between “self” and “monstrous Other” upon which the Western mythology of vampires had hitherto depended. In the work of writers such as Anne Rice, vampires became the objects of intense sentimental identification, melancholic, misunderstood Romantic outsiders who traversed a borderless world in search more of antidotes to their deep-felt sense of ennui than blood alone. Charged with delicious sexuality in the work of Angela Carter, Poppy Z. Brite and other writers and film-makers of the 1970s, 80s and 90s, vampires were used to perform a range of queer desires, dismantling and rearticulating the heteronormative structures of the nuclear family as they did so. Our bodies, our desires, our selves: no longer as easily recuperable under the sign of monstrosity, racial difference and sexual deviance became in later vampire narratives the objects celebration, fascination, even fetish.

Francois Sagat in Blab La Zombie by Arno Roca. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Francois Sagat in Blab La Zombie by Arno Roca. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.To be aware of vampires in the late 1990s and early 2000s was thus in some senses to reflect on “how far we’d come,” believing, as Nina Auerbach did in 1995, that every age embraces the vampire it needs and deserves. Vampiric awareness, here, was barely distinguishable from self-congratulation, the smug paying of lip-service to the forces of modernization, progress, and liberalization. With rise of neoliberalism, national and economic boundaries, elements once so vital to the vampire myth, were gradually erased. In Stephanie Meyer’s Twilight saga (2005‒2008), vampires learned to sparkle, the once overly-sexualized figures of strange desires rendered functional of the interests of abstinence and control. In this, the post-millennial era, vampires have entered the boundless world of cyberspace, and thrive in the borderless literary-, filmic-, and media-worlds of globalization. And yet, for a moment at the beginning of the twenty-first century, it seemed that the vampire’s ubiquity was in danger of being eclipsed by the swarming of another Gothic monster: in a post-9/11 world of global terrorism, it was the zombie, the vampire’s less sophisticated and attractive cousin, that seemed the most appropriate figure to condense and articulate Western culture’s fears of decline.

To return to our overriding question, though: what does it mean to be aware of vampires in late October 2016? The answer lies, partly, in all of the above. At its most fundamental level, to be aware of vampires is simply to acknowledge a figure that, of all species of Gothic monstrosity, has exerted the most powerful and enduring grasp on the cultural imagination since the beginning of the nineteenth century. As mercurial as the bodies of those that it infects, the vampire has mutated effortlessly across time, space, and creative medium, and, as in the case of Best Buy, taken up metaphorical existence at the heart of language itself for anything that saps an entity of its resources.

But vampire awareness in 2016 is also, I would argue, the disquieting acknowledgment of the return in modern Western society of some of the conditions that made the Victorian mythology take effect, among them resurgent nationalism and the policing of the boundaries of the state and nation. What, for example, is Britain’s recent decision to cede from the European Union (“Brexit”) but a rearticulation of the same Europhobic anxieties over national purity and contamination that made Stoker’s Eastern European Count into the monster that he was? Are the Victorian period’s xenophobic fears of “reverse colonization” in any way different from the right-wing discourse on immigration today, or is it simply that the particular objects of those fears have changed? And the influx of migrants and the so-called “refugee crisis” in Western Europe: a replaying of that vampiric fear of old that, once they have been admitted, these guests are likely to pervert our hospitable gestures, making of us, their hosts, the victims of unspeakable hostility? Building walls to keep the Other out, a relax in gun-control laws to make the Other more easily eradicable: though these and other signs of national anxieties over territory are all so familiar, contemporary politics is breeding a monster of an entirely different order. We watch in horror not as the shadow of the vampire appears on the screen, but as the new species of vampire-hunters sharpens its stakes, grimacing and gurning as it does so.

Featured image credit: ‘Vampire Children’ by Shawn Allen. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Vampire awareness in October 2016 appeared first on OUPblog.

Brexit wrecks it? Prospects for post-EU retailing

The UK’s retail sector is going to be a particularly sensitive indicator of the effects of the Brexit referendum decision. Retailers, whether they are store-based, online or both, are intermediaries at the end of the value chain – and as such are very close to both consumers and suppliers – so they’ll be at the receiving end of Brexit effects in other sectors ranging from agriculture to car production to financial services.

Any potentially negative impact would come at an already difficult time for retailers. Many are dealing with an already near ‘perfect storm’, including the impact of non-store channels, particularly mobile on large amounts of retail stores; the threat of new entrants; increasing price competition, as well as complex changes in consumer behaviour, including volatility in previously reliable sub-sectors such as clothing.

So far, any short term impact of the Brexit vote on spending levels has not been significant. Let’s look at consumers. Whilst we have seen enormous volatility in exchange rates and in share prices in vulnerable sectors (including some retailers) over the first few weeks following the referendum, these do not themselves drive buying behaviour in the short term, other than for lucky tourists. Many UK citizens will express their feelings about the consequences of the Brexit vote through their consumption behaviour over the forthcoming months and years, and in the light of critical events in the process (whether this be the triggering of Article 50, announcements by Japanese companies, or pontificating by Commissioners or Ministers.)

At least as far as spending is concerned; these feelings are unlikely to be positive, particularly in relation to spending on high value discretionary purchases, which will be deferred should confidence slip or prices increase.

Dresses apparel clothing by JamesDeMers, Public domain via Pixabay.

Dresses apparel clothing by JamesDeMers, Public domain via Pixabay.Long term, many consumers will become increasingly price sensitive. Inflation will tick up through price increases as a result of exchange rate effects on import prices. The prices of Apple’s new iPhone and Watch products experienced a 15-20% increase in markup against their initial entry level prices in September 2016. The short-lived spat between Tesco and Unilever over the price of Marmite in October is only the first of what will be a series of battles between suppliers and retailers, and is indicative of the dilemma faced by all food retailers in an already highly price competitive environment. The outcome will determine to what extent suppliers, retailers – or ultimately consumers – will have to absorb the uncertainty premium arising from the Brexit decision, as it works its way through the economic system. What might this mean for consumer behaviour? Certainly a boost to online price comparison services and e-commerce as consumers still wanting to spend shop around for the best deals.

What will retailers do longer term? The prospects for fast growth in European markets have never been very good. In the context of a declining domestic market, the biggest firms will look for higher growth opportunities elsewhere in the world. Equally, overseas entrants, although they might find entry or M&A costs a little lower, may well be deterred from UK openings. If anything, this will precipitate a readjustment of the cost base of many of the larger bricks and mortar retailers, with a faster closure of poorly performing real estate and a greater reliance on online platforms.

So will Brexit wreck the retail sector? Probably not, but it’s not going to help. In the absence of a crystal ball, nevertheless, the sector’s performance will be an extraordinarily interesting bellwether for the UK economy.

Featured image credit: Shopping Cart Supermarket by Michael Gaida. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Brexit wrecks it? Prospects for post-EU retailing appeared first on OUPblog.

Philosophy of Science/History of Science Biennial Meeting 2016: a conference guide

The Oxford Philosophy and History teams are excited to see you in Atlanta for the upcoming 2016 History of Science/Philosophy of Science Biennial Meeting. We have some suggestions on sights to see during your time in Georgia as well as our favorite sessions for the conference.

We suggest visiting the following sights and attractions while in Atlanta:

Atlanta in November is a great place for those who enjoy nature. Enjoy a run or stroll in some of the many parks including Centennial Olympic Park, Piedmont Park, and Atlanta Botanical Garden.

An important place for the Civil Rights Movement, Atlanta is home to key museums and historic spots. Visit the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site, The APEX, and Center for Civil and Human Rights to trace the history of civil rights in America.

Atlanta and the surrounding areas has been used extensively for filming purposes. You can take a tour of TV filming locations like The Walking Dead and Atlanta, as well as visit the inspiration for the classic movie Gone with the Wind.

Keep an eye out for these conference sessions that we’re excited about:

Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Thursday, November 3rd: 9:00 – 10:30 AM:

Topics in Philosophy of Economics (Sponsored by the International Network for Economic Method) featuring Caterina Marchionni, Brian Epstein, Maria Jimenz-Buedo, and Erik Angner.

Thursday, November 3rd: 10:45 – 12:45 PM:

Chemistry as a Source of New Perspectives for the Philosophy of Science (Sponsored by the International Society for the Philosophy of Chemistry) featuring Eric Scerri, Olimpia Lombardi, Grant Fisher, William Goodwin, Juan Camilo Martinez, and Jean-Pierre Llored.

Thursday, November 3rd: 3:45 PM – 5:45 PM:

Physics in the 19th and 20th Centuries featuring Peter Ramberg, Joshua Eisenthal, J. Brian Pitts, Gustavo Rocha, and Stephen Brush.

Friday, November 4th: 8:30 – 10 AM:

Biopolitics in History, 1500-1800 featuring Robert Markley, Al Coppola, Lucinda Cole, and Richard Barney.

Friday, November 4th: 9:00 – 11:45 AM:

Symposium: Science, Values, and Wishful Thinking featuring Immaculada de Melo-Martin, Daniel Hicks, Kevin Elliott, Matthew J. Brown, Sharon Crasnow, Kristen Intemann, and Daniel Steel.

Friday, November 4th: 12:00 – 1:15 PM:

Roundtable: The Relevance of History of Science to Diversity and Global Learning featuring David Spanagel, Richard Beyler, Jacob Hamblin, and Helen Rozwadowski.

Friday, November 4th: 1:30 – 3:30 PM:

Symposium: Multiple Realizability in a Physical World featuring Gualtiero Piccinni, Meir Hemmo, Thomas Polger, Lawrence Shapiro, and Orly Shenker.

Saturday, November 5th: 9:00 – 11:45 AM:

Symposium: The Public Understanding of Science: Philosophical & Empirical Approaches featuring Miriam Solomon, Chris Haufe, Arnon Keren, Boaz Miller, Meital Pinot, Matthew Slater, Joanna Huxster, Deena Skolnick, S. Emlen Metz, and Michael Weisberg.

Saturday, November 5th: 1:30 – 3:30 PM:

Contributed Papers: Explanation & Understanding featuring Michael Lissack, Bradford Skow, Matthew Haug, Insa Lawler, Yannick Doyle, Spenser Egan, Noah Graham, and Kareem Khalifa.

Take time to visit the Oxford University Press Booth! Browse new and featured books which will include an exclusive conference discount. Pick up complimentary copies of our philosophy journals which include The British Journal of the Philosophy of Science, Analysis, Public Health Ethics, and more! Receive free access to our online resources including Oxford Handbooks Online, Very Short Introductions, Oxford Reference, and more. And, of course, stop by to say hi!

Featured image: Atlanta panorama by Brooke Novak. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Philosophy of Science/History of Science Biennial Meeting 2016: a conference guide appeared first on OUPblog.

October 29, 2016

The Reformation: a conversation about death

After studying the Reformation for over four decades, I’ve found myself alongside many other historians in pulling down one great Protestant myth: all you needed to do was put a little finger on the structure of the medieval Western Church, and it would fall over and collapse. Not so: the old religion satisfied most people and satisfied consumer demand. So how did Protestant Reformers destroy an institution which was powerful, strong and self-confident? Only the power of ideas could have had such a dramatic result.

The Reformation was not caused by social and economic forces, or by nationalism but by big ideas about death, salvation, the afterlife. This seized the friar Martin Luther, inspired so many people in Europe, and brought that strong structure down. It was not the religiously indifferent who became Protestants, but those who like Luther, had believed passionately in the old Church’s road to salvation, and were then convinced that they had been cheated. White-hot Catholics became white-hot Protestants. Because Luther’s struggle involved an attack on the power which the Church claimed to help people in gaining their salvation, it became a power struggle in a much wider sense.

More remarkable still was that behind the thoughts of Luther, Calvin and all the other Reformers who called themselves Protestant, were the thoughts of two men centuries before: first the Apostle Paul of Tarsus, and then the African theologian of the fourth century, Augustine, Bishop of Hippo (don’t mix him up with the other Augustine, of Canterbury).

You cannot overestimate Augustine’s importance to western Christianity.

You cannot overestimate Augustine’s importance to western Christianity. At first sight it is a puzzle that Augustine was so tangled in the Protestant Reformation, because he was equally important for Catholics. One very fine American historian of the Reformation, B.B. Warfield, said words to the effect that the sixteenth-century Reformation was a battle in the mind of fourth-century Augustine. Catholics listened to one part of what Augustine said, mainly about the Church and its authority, while Protestants listened to another part about what he had called grace: the gift of God which brings salvation to individual humans. Both Catholics and Protestants were right, because both Church and grace mattered to Augustine. You can see why the Church should matter, because Augustine became a bishop of the Universal church, and brooded a great deal about what that might mean. Why should his thought on grace pull in a different direction?

To understand that, you need to go behind Augustine to Paul of Tarsus four centuries before his own time. Augustine read Paul, especially his letters to Churches in Rome and Galatia, and saw a picture of an all-powerful God, contrasted with a humanity utterly fallen, utterly corrupt, worthy of nothing but punishment because humans had disobeyed their creator. Augustine trained his thought on this frightening doctrine like training the sun through a magnifying glass onto paper until it bursts into flame. Augustine called human beings “a lump of perdition.” There is nothing that people like you and me can do for our own salvation. You need God to do it all.

Luther just said what Augustine had said before him. That became subversive because Luther saw the church of his day telling people they could do things for their salvation. He had believed in that idea, and now he thought it was a confidence trick, a cheat. He made Augustine’s message so loud and clear that he ignored Church leaders who told him to be obedient and forget the implications of Augustine’s views on grace. It was not just some abstract argument, because it affected everyone’s being and their eternal happiness. This life is very short, and in the Christian scheme of things, the afterlife is very long – eternal, actually. Heaven and Hell beckon. There is only one chance to go through the right entrance when you die.

But the medieval Western Church suggested something more complicated, and more comforting. God might provide an extended chance to achieve purity and atone for sin: the state known as Purgatory, a tough preparation for Heaven. Purgatory had only one exit, but it was best not to linger there too long. You might influence God’s decision to speed up your journey through Purgatory, with the help of all the power which God had given his Church: the power of prayer being the most powerful gift of all. The highest form of prayer in Christian practice is the piece of theatre which re-enacts Christ’s last supper with his disciples.

The Western Church called this re-enacted meal, the Mass. It told the faithful that the more Masses they directed towards prayer for the dead in Purgatory, the more God would be induced to show mercy for salvation. Only clergy could preside at the Mass and had the power to make it more than a meal. Thus when Luther denied Purgatory, he was attacking the power of the clergy and of the Church. He said that they had set out to con the faithful people of God. What a complex tangle of consequences! All because of ideas: ideas which led to practical action, and much of that action angry and cruel on both sides. Though remember this Reformation five centuries later, we may forget that it was an argument literally about life and death.

Featured image credit: Notre Dame by RCbass. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post The Reformation: a conversation about death appeared first on OUPblog.

Cities lead pushback against Big Soda

Hacked corporate emails that expose Coca-Cola’s efforts to quash local health initiatives, a long-awaited statement from the World Health Organization expressing strong support for taxes on sugary drinks, and upcoming votes on four local soda tax proposals are keeping the grassroots movement to protect health over beverage industry profits front and center this fall.

Over the past seven years, the beverage industry has been taking pages out of Big Tobacco’s playbook, pouring over $67 million into defeating soda tax initiatives in 19 US cities and states. On the eve of November’s soda tax votes in the Bay Area cities of Oakland, San Francisco, and Albany, the beverage industry has blocked $9.5 million in TV ad time (out of more than $20 million total spending in California this year to shut down soda tax campaigns), preying on the economic anxieties of Bay Area residents by deceptively branding the initiatives as “grocery taxes.”

These expressions of concern for the welfare of the Bay Area’s communities of greatest need, particularly communities of color, are coming from the same industry that shamelessly blankets low-income neighborhoods with its ads and has saddled generations of its low-income consumers with high-price medical conditions like type-II diabetes, heart disease, and tooth decay.

The industry spends about $866 million per year to market to kids everywhere they go, from their homes to their classrooms and through their social networks. Black youth saw more than twice as many TV ads for sugary drinks and energy drinks compared with their white peers and black teens saw four times as many Sprite ads and three times as many Coca-Cola ads as white teens. Hispanic youth were 93% more likely to visit beverage company websites compared with all youth, while black youth were 34% more likely to visit these websites.

Soda and other sugary drinks are the number-one source of added sugar in the American diet, driving an epidemic of type-II diabetes, heart and liver disease, and tooth decay. Drinking just 12 ounces of soda a day can increase the risk of heart disease by a third, and people who consume one to two sugary drinks per day have a 26% greater risk of developing type-II diabetes. And the burden of diet-related disease isn’t distributed evenly: low-income communities and communities of color face the highest rates of preventable diseases. One-third of all children and nearly half of African-American and Latino children are predicted to develop diabetes in their lifetimes.

Drink-Soda-Glass by Mitaukano. CC0 Public Domain Via Pixabay.

Drink-Soda-Glass by Mitaukano. CC0 Public Domain Via Pixabay.But now – tens of millions of dollars in ad buys, lobbying, and deceptive public relations campaigns later – soda companies are learning what their predecessors in the tobacco industry learned the hard way: that when community-driven health initiatives go mainstream, there’s no turning back. A powerful coalition of community members, activists, and researchers across the country are using the same tactics that changed policies and norms around tobacco use against the beverage industry, and winning. Today, it’s easy to forget that doctors once hawked cigarette brands, that smoking on airplanes and in workplaces used to be the norm. Community-based activism rewrote the story of tobacco use in the United States – rejecting the industry’s narrative that nicotine dependency equaled independence, changing the culture, and saving millions of lives of in the process. Now, communities are opting out of the “Pepsi generation” and walking away from “the Coke side of life” toward a healthier future.

This summer, Philadelphia became the first major city in the United States to pass a soda tax, expected to generate $91 million in its first year to fund public resources like pre-Kindergarten programs, libraries, and parks. Seeing this measure succeed in a city where it had failed twice before marked a sea change in the national conversation about how to address the outsized impacts the beverage industry’s products have on health.

Meanwhile, Berkeley’s soda tax – passed with overwhelming support from voters in November 2014 and enacted in March 2015 – is showing results. Berkeley’s low-income neighborhoods are drinking 21% less soda and other sugary drinks, while consumption of tap and bottled water increased by 63%. One year out, the soda tax had generated $1.5 million for community nutrition and health programs, including school gardens.

This is just one face of a broader community-led movement to put health and safety first, pushing back against industries and powerful interests that have too often sacrificed community wellbeing to corporate profits. Across the country, we see workers standing up to corporations that don’t pay living wages in the Fight for 15; residents organizing against displacement and environmental injustices like unsafe drinking water, pesticide spraying near schools and homes, and toxic land uses; immigrant and racial justice coalitions demanding an end to private prisons; Native American and First Nations activists demonstrating against legislation that would weaken indigenous sovereignty and environmental protection and open the door to further environmental degradation; social justice movements like Black Lives Matter transforming the national dialogue on racial inequities entrenched in our institutions and policies; and families touched by gun violence challenging the manufacturing, marketing, sale, and regulation of deadly weapons that have infiltrated too many of our homes and public places.

This kind of community-driven change in norms is what public health is all about. A healthier future for all is possible. Our communities are leading the way.

Featured image credit: Happy Child by tykejones. CC0 Public Domain Via Pixabay.

The post Cities lead pushback against Big Soda appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers