Oxford University Press's Blog, page 445

November 5, 2016

Hillary Clinton, feminism, and political language

Language is, of course, how we communicate political ideas to each other. But what is not often realized is that the language we use can itself be political. Often on the face of it, the way in which our language is structured — the words themselves or their denotations — are seen to betray no political significance. To be trite and quote Orwell, “Underneath this lies the half-conscious belief that language is a natural growth and not an instrument which we shape for our own purposes.”

Many feminists criticize the traditional idea that language is a neutral vessel that merely depicts reality, because, like Orwell (who was markedly not a feminist), they see language as a powerful, and undeniably political, tool that can easily be weaponized. And not just in the form of political name calling to damage an individual opponent’s reputation, like labelling an opponent “crooked,” but also in the ways language actually shapes reality. For example, words like “caring” or “bitchy” are used more often to describe women than men, thereby embedding in our social consciousness the notion that these are specifically feminine traits — and traits that are undesirable in our political leaders.

Deborah Cameron, a professor of linguistics at Oxford University, writes that “… societies are characterised by the incessant production of messages, images, and signs. To understand society therefore entails learning how to ‘read’ its cultural codes, its languages.” (Feminism and Linguistic Theory, 2nd ed., 1994) This can just as easily apply specifically to election campaigns. The American political system and its corresponding language from stump speeches to the Congressional floor is a realm designed of men, by men, and for men, and little has changed in that respect over the course of our 240-year history. The problem for women here is easy to see and captured nicely by Dee Dee Myers, Press Secretary during the Clinton Administration: “If male behavior is the norm, and women are always expected to act like men, we will never be as good at being men as men are.” Cameron goes on to assert that, “[language] is a powerful resource that the oppressor has appropriated, giving back only the shadow which women need to function in a patriarchal society. From this point of view it is crucial to reclaim [political] language for women.”

Democratic Presidential Candidate Hillary Clinton has proven herself adept at functioning within this masculine paradigm of politics, and can attribute most of her success today to that set of skills. She has

Who were Shakespeare’s collaborators?

The following is an extract from the General Introduction to the New Oxford Shakespeare, and looks at the many different playwrights, actors, and poets that collaborated with Shakespeare.

When we read Shakespeare’s Complete Works we are primarily, of course, reading Shakespeare. But as a bonus we also get, in the same volume, an excellent anthology of most of the important playwrights who were his collaborators. Shakespeare collaborated for the same reason that most people do: different members of the team are especially good at different tasks. The poet Alexander Pope, who edited Shakespeare’s plays in 1725, had no idea that Fletcher had wrote parts of All Is True, but we now know that the four passages he singled out as particular ‘beauties’, worthy of special attention, were all written by John Fletcher.

Shakespeare’s conversations with other writers and artists, the interweaving of his creativity with theirs, began in his own lifetime. His last three plays were all co-written with Fletcher – who, in all three, seems to have written more of the surviving text than Shakespeare. But Fletcher also wrote The Tamer Tamed, a sequel and reply to The Taming of the Shrew, in which we learn that Kate was never successfully tamed, and Petruccio’s second wife tames him; we know the two plays were performed together at court in 1633, and perhaps much earlier. Ben Jonson’s Sejanus was clearly a response to Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, but it also seems likely that the lost version of Sejanus performed by the King’s Men was a collaboration between the two men, just as Shakespeare’s ‘Let the bird of loudest lay’ was originally printed in a small collection of commissioned poems by several poets, including Jonson. Thomas Middleton, ‘our other Shakespeare’, was Shakespeare’s junior collaborator on Timon of Athens, but he also seems to have adapted four of Shakespeare’s plays between 1616 and 1623 (Titus Andronicus, Measure for Measure, All’s Well that Ends Well, and Macbeth). Middleton began the long historical tradition of adapting Shakespeare’s work to make it more suitable, and more interesting, for later audiences. But Middleton also wrote a reply, The Ghost of Lucrece, to Shakespeare’s Lucrece; an early owner bound the two poems together in a single volume.

Thomas Middleton. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Thomas Middleton. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Shakespeare was, and is, bound to many kinds of artist, not just poets and playwrights. In the last two decades of his career he was legally bound together with the other ‘sharers’ of a joint-stock company of actors. This means that Shakespeare created his characters for individual actors who would collaborate with him in performing the play. In fact, each actor received a separate manuscript, called a ‘part’, containing only the speeches of the character he was going to create, and a few words of his cues. From the beginning, each actor ‘owned’ his character.

Those actors literally embodied Shakespeare’s characters, by giving them a particular physique and a particular face. By comparison with most modern plays, Shakespeare’s scripts say almost nothing about the visual impression created by his characters, perhaps because he had already cast them in his mind, as he was writing them. Certainly, once we have seen a particular actor play a role we tend to think of the character in terms of that actor’s body, and especially that actor’s face , and modern playwrights often anticipate or imagine a particular actor as they are writing (Figure 000).

All his plays were written to be co-created by a team. But that team also changed over time, as actors like the star comedian William Kemp left, and new talents like Robert Armin and John Lowin arrived. Even if the actors remained the same, the spectators did not, in part because they were being influenced by other playwrights. Early in his career Shakespeare was competing with better-educated playwrights, most of them older than him, and with playwrights with more experience writing successful plays: Watson, Kyd, Greene, Peele, Lodge and Marlowe. He outlived them all, but by the late 1590s he was challenged, and new audience tastes were being shaped, by fashionable younger playwrights, beginning with Ben Jonson, George Chapman, and John Marston, soon followed by Thomas Middleton, then by Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher.

In the decade before 1594, when the Chamberlain’s Men was created, England’s infant theatre industry had gone through years of turmoil, with acting companies disintegrating, consolidating, and morphing rapidly and unpredictably. This was Europe’s first mass-entertainment industry, and like any new industry it went through a chaotic period of trial and error, erratic boom and bust. After such an apprenticeship, Shakespeare could never have expected a play to be performed, for any long period, by exactly the same cast.

Nor could he have expected his plays to be performed, always, in the same space, or for a stable loyal audience of predictably returning theatregoers. Shakespeare’s first experiences of new English plays would have been the many visits to Stratford-upon-Avon of actors on tour: between 1569 and 1587 he could have seen dozens of plays performed by all the country’s most important professional adult companies. Such touring in the ‘provinces’, away from London, continued to be a fundamental part of the theatre business throughout his working life. So did performances at court, for intellectually and financially elite audiences in spaces that were never designed for the convenience of actors. The plays he wrote for Elizabeth I continued to be revived after her death and the succession of King James I.

Shakespeare’s commercial success in his own time depended on his ability to write adaptable scripts: plays that would reward different actors and different kinds of audience, plays that would survive a weak performance or different interpretation by a new member of the cast, plays that did not depend upon a particular size or shape of stage, plays that could appeal to different political regimes. Adaptability was the secret to stability.

Shakespeare’s plays have continued to do for centuries what they did in his own lifetime: adapt to connect to an endless succession of new collaborators, new venues, and new audiences.

Featured image credit: Signature alleged to be William Shakespeare’s, found in a copy of Florio’s Montaigne in the early 19th century. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Who were Shakespeare’s collaborators? appeared first on OUPblog.

What are we asking when we ask why?

“Why? WHY?” If, like me, you have small children, you spend all day trying to answer this question. It’s not easy: sometimes there is no answer (a recent exchange: “Sharing is when you let someone else use your things.” “Why?”); sometimes you don’t know the answer; even when you do, your child isn’t satisfied, he just goes on to ask “why?” about the answer.

This follow-up why-question is worth pausing over. Suppose you were asked why the lights came on and you answered that the lights came on because you flipped the switch. When your child immediately follows-up with a “why?” his question is ambiguous. Is he asking: why did you flip the switch? Or is he asking: why is it that the lights went on because you flipped the switch? The second interpretation is a meta-question, equivalent to: why is what you said the answer to the original question? Now we’re in philosophical territory. Philosophy is concerned, not just with answering this or that why-question, but also with answering a meta-question about why-questions: what does it take for a proposition to be an answer to a why-question?

If we start with a small diet of examples there appears to be a clear pattern. Why did the bomb explode? Because someone lit the fuse. Why did the balloon pop? Because it hit a sharp branch. In these cases we have asked, of something that happened, why it happened; and in all of these cases the answer mentions a cause of that thing. This observed regularity suggests a hypothesis: you can answer a question of the form “why did such-and-such happen?” with “such-and-such happened because X” when, and only when, X describes a cause of that thing.

To test this hypothesis we need more data. One place to look is science. But science appears to casts doubt on it, for scientific answers to why-questions often seem to go beyond describing causes.

Do they really go beyond causes? Let’s look at a particular example. The spruce budworm lives in the forests of eastern Canada and eats the leaves of the balsam fir tree. Usually the budworm population is held in check, but occasionally the population explodes; when this happens the budworms can eat all the leaves and thus kill all the forest’s fir trees in about four years. Suppose the budworm population explodes; our question is: why did the population explode?

One response uses a mathematical model of the growth of the budworm population. The equation for the model, which describes how the budworm population X changes over time, is

dX/dt = rX(1-X/k)-X2/(1+X2).

There are two influences on number of budworms: reproduction, which increases the population — that is the term rX(1-X/k) in the equation; and predation by birds, which decreases it — that is the term -X2/(1+X2). The term r is the budworm’s “natural growth rate,” and k is the forest’s “carrying capacity” (the maximum number of budworms that the forest can sustain).

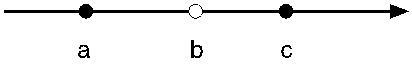

We can depict the information contained in this model on a line. The points on the line represent possible sizes of the budworm population. The points toward the left represent small sizes, the points toward the right, larger sizes. The solid circles are stable equilibrium points: the population quickly moves toward and stays near a stable point. The open circle is an unstable equilibrium point; the population moves away from it. So if the budworm population is smaller than point B, it will move toward (a); if the population is larger than (b), it will move toward (c) Before the population explosion, when the budworm population is relatively low, it is at (a). After the population explodes it is at (c). The question is, why did it jump to the higher point?

Figure 1. Created by and used with permission from the author.

Figure 1. Created by and used with permission from the author.To answer we need to see how the positions of (a), (b), and (c) change as r, the natural growth rate, changes. The value of r goes up as the forest grows. And as r goes up (a) and (b) move toward each other, as in figure 2, until, at a certain value for r, they vanish. When that happens (c) becomes the only stable equilibrium, and the population it quickly increases to it — and the population explodes.

Figure 2. Created by and used with permission from the author.

Figure 2. Created by and used with permission from the author.I’ve answered the question of why the budworm population exploded. Now if everything I said is part of the answer, then the hypothesis I’ve been investigating, that “such-and-such happened because X” is true when and only when X describes a cause, is false. For the only relevant cause of the explosion is: the forest grew above a critical size. But I didn’t just say that this happened. I also wrote down a law governing the budworm population’s evolution. That law didn’t (couldn’t!) cause the budworm population to explode. If the law is part of the answer to the question of why the population exploded, then answers can do more than describe causes.

I, however, do not think that the law is part of the answer to the question of why the population exploded. I think that the answer consisted just in the fact that the forest grew big enough.

But how can this be? Doesn’t this mean that those paragraphs I wrote contain a bunch of information that is not part of the answer to the question of why the population exploded? Surely that can’t be. If you ask a question, and someone gives you a bunch of information that is not part of the answer, you will notice that they are changing the subject. But when I described the model of the budworm population it didn’t feel like I was changing the subject.

Responding to a question by providing information that is not part of the answer does not always feel like changing the subject. If I ask who came to the party and you respond “Jones did, I saw him there myself” you’re providing information that goes beyond the answer (which is just “Jones did”). But the extra information is relevant: in this case, it is your evidence for why your answer is correct.

That’s what I think is going on in the budworm example. If I just say that the budworm population exploded because the forest reached a certain size, you might well be skeptical: forests grow slowly, how can a small change in the forest size trigger such a huge change in the budworm population? The model shows how: when the forest grows above a certain size the low-population equilibrium state vanishes.

I’ve been defending a simple theory of answers to why-questions: the complete answer to “why did such-and-such happen?” lists the causes of that thing, and nothing else. But please don’t take this theory to say that scientists are wasting their time developing mathematical models, or searching for laws governing the phenomena they are interested in. The laws and models, while not parts of answers to questions about why things happened, are essential for coming to know that those answers are correct. In fact I think their role is even more exalted: they are essential for coming to know why those answers are correct. But that is a story for another time.

Featured image: Light Bulb by jniittymaa0. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post What are we asking when we ask why? appeared first on OUPblog.

November 4, 2016

“True” stories of the obesity epidemic

“Eat right and exercise”: amid the cacophony of diet fads and aids, conflicting reports regarding what causes obesity, and debate about whether and what kind of fat might be good for us after all, this seems like pretty sound and refreshingly simple advice. On the surface, it is: it’s hard to argue against good nutrition or circulation. But dig a bit deeper and it’s a veritable political and cultural minefield.

In the first place, the “eat right and exercise” maxim places full responsibility for weight on the individual’s shoulders: it’s on him or her to monitor and regulate intake and output. A variation of this theme is the “calories in/calories out” narrative of obesity, featured in every “official” public obesity campaign originating from health or government agencies: we are encouraged to make wise choices by these agencies, who stand by to offer resources, but don’t presume to cross the line in ways that might compromise our autonomy. Moreover, what does it mean to “eat right?” Perhaps calorie restriction is part of that, but it’s mostly understood to mean quality of food—fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean meats, for instance. As Michael Pollan succinctly surmised in his Eater’s Manifesto, “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.” But in the context of the obesity crisis and the discourse surrounding it, this is grounds for a host of debates regarding how such foods are grown and processed—considerable science suggests, contrary to the caloric imbalance narrative, that obesity is a consequence of endocrinal and hormonal imbalance, perhaps prompted by “adultered” food, whether via pesticides, hormone or antibiotic treated livestock, GMOs, refinement/processing, or preservatives. And of course, those debates are inherently political and ideological because they inevitably lead to questions about food politics in particular, and the political economy in general: Big Agriculture, food subsidies, greed, and profit. Which brings us back to the individual: if industry is responsible for the obesity epidemic, what is our role? What is the government’s?

Diet by Jennifer Burk. Pubic domain via Unsplash.

Diet by Jennifer Burk. Pubic domain via Unsplash.In fact, the core issues that inform each of these competing narratives are reflections of the broader political economic crisis that the United States (and most of the world) has been grappling with since 2008—a crisis in neoliberalism, a political economic philosophy that promotes a market unfettered by government oversight and justified by individual autonomy: that is, individuals are articulated as having more and better choices if the industry responds exclusively to their demands. Government regulation is understood in this view to be patronizing and oppressive to the individual. In 2008, when the bottom fell out of neoliberalism, this self-serving (for industry) logic was called to task, in particular as relevant to its insensitivity to the material realities and experiences of everyday citizens, a sentiment popularized in the “99 percenters” movement. This same impasse is evident in the “official” story of obesity—the rational individual monitoring her/his consumption, unfettered by structural intervention and aided by the market—and the reactive, environmental obesity story that posits the individual as the hapless victim of corporate greed.

Between these stories exist a number of competing cultural narratives of obesity. While all of them, like any story, contest “the facts,” at heart they are attempting to give shape to a piece conspicuously absent from the originary narratives: authenticity, a powerfully resonant sensibility in our culture today. The official story turns on a rational agent who successfully resolves or avoids obesity by engaging in simple caloric budgeting; the reactive narrative posists instead a passive subject acted upon by industry. Neither acknowledges the experienced intimacies, materialities, and sensualities entailed by body and food that lie at the heart of obesity— and for that matter, of identity. Writ large, we are struggling with these same issues on a broader cultural scale: the contemporary tensions, anxieties, and imperatives that characterize visceral, literal consumption are likewise written upon the national body. As obesity goes, so goes the nation.

Featured image credit: scale diet health tape by mojzagrebinfo. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post “True” stories of the obesity epidemic appeared first on OUPblog.

The founding of the Electoral College

Every four years, the debate over the United States’ continued use of its Electoral College reemerges. The following excerpt from Michael Klarman’s The Framers’ Coup: The Making of the United States Constitution discusses the political interests that shaped the Electoral College and American presidential politics as a whole:

Late in the convention, a grand committee appointed to tackle various unresolved issues endorsed a proposal first made by Wilson, which the convention had already rejected on multiple occasions: The president would be chosen by special electors, whose appointment would be made according to a method specified by state legislatures. Because the body of electors would have no perpetual life, it would have no particular interests to defend. A president selected in this fashion would not be dependent upon the institution selecting him.

Moreover, the electors would presumably be prominent people of superior knowledge and independence. This is what inclined the delegates to consider entrusting them with a task as important as choosing the president (although dissenting delegates denied that “first characters” or “the most respectable citizens” would be interested in holding a transitory position such as that of presidential elector). The report of the Committee on Unfinished Parts also specified that electors would cast ballots in their home states in order to preclude, in Morris’s words, “the great evil of cabal.” Requiring that electors in the different states meet simultaneously throughout the country made it “impossible to corrupt them.” Moreover, the use of electors in place of direct popular election obviated the problem of slaves counting for nothing, which would have been disqualifying from the southerners’ perspective. The electoral college system was ingenious, though Caleb Strong objected that it would “make the government too complex.”

The issue of how to apportion presidential electors naturally provoked disagreement between delegations from large and small states. When the issue was discussed earlier in the convention, at a time when the delegates were considering an electoral college system for choosing the president, small-state delegates had favored a relatively flat distribution, in which the small states received one elector and no large state more than three. Unsurprisingly, large-state delegates had thought their states deserved even greater influence in choosing the president. Connecticut delegate Ellsworth objected to giving large states extra clout in the electoral college, which he said their citizens would probably use simply to prefer candidates from their own states.

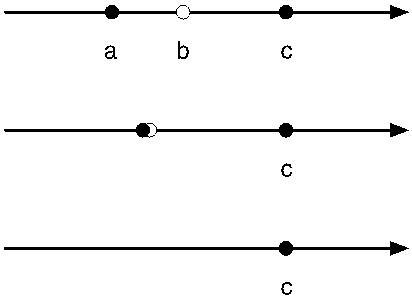

State-by-state breakdown of the 2016 Electoral College. Image credit: “Electoral College 2016” by Cg-realms. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

State-by-state breakdown of the 2016 Electoral College. Image credit: “Electoral College 2016” by Cg-realms. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.The grand committee’s report proposed a compromise on the apportionment of the electoral college: Each state’s number of presidential electors would equal its number of congressional representatives plus its two senators. Small states would fare better than if the apportionment had been based strictly upon population, yet large states still derived a substantial advantage from their greater populations, as reflected in their number of congressional representatives. Thus, for example, Virginia would outnumber Delaware by ten to one in the first House but only by twelve to three in the first electoral college. Because the number of electors depended partly on a state’s number of congressional representatives, the power of southern states in the electoral college would reflect their slave populations.

In addition, the committee proposed that no candidate could be elected president without securing the votes of a majority of the electors appointed. If no candidate received such a majority, then the Senate would choose the president from among the top five vote getters. Convention delegates mostly assumed that presidential candidates would rarely win outright majorities in the electoral college—at least once Washington had ceased to be a candidate. The vast geographic scope of the country, combined with the relatively primitive state of transportation and communication, would prevent presidential candidates from becoming widely known or coordinating their campaigns across states—especially in the absence of national political parties, which the delegates did not assume would exist. Thus, Charles Pinckney protested that the electors would “not have sufficient knowledge of the fittest men and will be swayed by an attachment to the eminent men of their respective states,” and Mason predicted that “nineteen times in twenty the president would be chosen by the Senate….”

Accordingly, some large-state delegates objected to the committee’s proposal and suggested eliminating the requirement that a presidential candidate receive the votes of a majority of the electors in order to be elected. Yet small-state delegates naturally resisted a proposal that would have ordinarily allowed the electors from just a few of the large states to pick the president by themselves, and it was easily defeated. The convention then also rejected a motion by Madison to substitute “one-third” for “a majority” as the requirement for the candidate winning the most votes in the electoral college to be elected president.

State-by-state results from the 2012 US Presidential Election. Image credit: “Electoral college map for the 2012 United States presidential election” by Gage. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

State-by-state results from the 2012 US Presidential Election. Image credit: “Electoral college map for the 2012 United States presidential election” by Gage. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.As just noted, according to the committee’s proposal, the Senate’s choice would be made from among the top five vote getters in the electoral college. The number five was a compromise between the preference of a large-state delegate such as Mason, who suggested limiting the list to three, and that of a small-state delegate such as Sherman, who would have preferred expanding it to seven or even thirteen candidates. Madison expressed concern that if the president were to be chosen from a list as long as even five vote getters, “the attention of the electors would be turned too much to making candidates instead of giving their votes in order to [make] a definitive choice.”

Several delegates objected to the Senate’s being made the de facto selector of the president on the grounds that, under the committee proposal, the Senate and the executive were also now slated to jointly exercise the powers of appointment and treaty making. For example, Wilson protested that if the Senate were to make the ultimate choice of the president, he “will not be the man of the people as he ought to be, but the minion of the Senate.” Mason warned that “if a coalition should be established between these two branches, they will be able to subvert the Constitution.” Williamson objected that referring the appointment of the president to the Senate “lays a certain foundation for corruption and aristocracy”—a view with which Randolph concurred…

Thus, Wilson and other large-state delegates proposed that “the legislature” rather than just the Senate choose the president from among the top vote getters when no candidate received the votes of a majority of the appointed electors. Sherman suggested that the House—rather than the Senate alone or both houses of Congress together—should choose the president in such situations. Because Sherman proposed that the House, when selecting the president, vote by delegation rather than as individual representatives, small-state influence would be preserved, while “the aristocratic influence of the Senate” would be eliminated. The convention then overwhelmingly approved the substitution of the House for the Senate. Madison later explained that, in addition to other considerations, the House was thought safer “on account of the greater number of its members,” which would “present greater obstacles to corruption than the Senate with its paucity of members.”

Featured image credit: “White House” by Diego Cambiaso. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The founding of the Electoral College appeared first on OUPblog.

Unleashing the power of bioscience for human health

The 21st century is said to be the century of bioscience, with the promise of revolutionising human health. Every week we hear of dramatic discoveries in research labs, new genome links to disease, novel potential treatments for diseases like cancer and Alzheimer’s, nanotechnology applications to create miniature machines for inside the human body, and digital health tools to track the state of our health as we go about our lives. More than two million academic biomedical science papers pour out each year, over 14,000 patents are filed, and thousands of possible new drugs are studied – the statistics are impressive and rising, as governments and private industry invest more heavily in life sciences than any other field.

And yet only 30-40 new drugs are approved each year, each after more than ten years of effort and millions of dollars spent in clinical trials. Only a small handful of cell and gene therapies reach patients, despite more than two decades of investment in these powerful new regenerative medicine modalities. Worse still, many of the new treatments that manage to penetrate the market reach only a small fraction of patients who could benefit. In reality, digital health fails to deliver the promised revolution in how we manage and monitor our health. The question that needs to be asked is what’s going on?

If we compare the changes in human health to information technology, the contrast is dramatic. On the basis of a few advances in basic electronics, many of which are 20 years old – and their steady miniaturisation – we have new generations of powerful devices and applications every year. Smart phones, tens of thousands of new apps, exciting advances in artificial intelligence, and the Internet of Things all around us – we see the ultra-fast translation of technology into useful products and services. In fact, they seem often to arrive faster than we can track and adopt them. So why is this speed of new innovation not visible in bioscience?

So why is this speed of new innovation not visible in bioscience?

Most of our new science is getting ‘lost in translation’. Consensus over who is to blame is lacking, with criticism falling on the industry, regulators, over-conservative doctors, and stingy health systems. They are blamed for the growing innovation gap – the gap between what science now makes possible and what actually results in patient benefit and creates new models of care. Like many human diseases of course, this disease of the system, this gap in translation could be said to be “multi-genic”, with many causes and no easy simple answers.

An overhaul of the innovation system for life sciences seems called for. Indeed, worried governments, challenged by ever more activist patients seeking cures for their diseases, are launching dramatic-sounding initiatives like ‘21st Century Cures’ in the United States or the ‘Accelerated Access Review’ in the United Kingdom. Can these initiatives make the crucial difference, close the innovation gap, and bring the life-changing products that patients need more quickly, affordably, and reliably, to transform our health systems? Only time will tell, and the fact remains that government motivation for such initiatives is not only to improve the health of their populations, but also to generate economic growth and to secure better returns for their rising spend in bioscience.

In order to effectively tackle this problem and unleash the power of bioscience for healthy human lifespan, we must look beyond simplistic remedies and understand the major factors in poor translation:

How basic bioscience is focused (or not) on human disease

The translation of scientific breakthroughs into potential new products

Approval for use and reimbursement of new products

Practical adoption by doctors and patients of new products

How we learn from practical real-world use to shape the future R&D agenda

All of these five gaps can stymie life science innovation and so result in poor returns for government and company investment.

…there is a golden thread that runs through most of the solutions needed to address this failure in translation: Precision Medicine.

I believe there is a golden thread that runs through most of the solutions needed to address this failure in translation: Precision Medicine. We are learning how the molecular basis of disease can help us find more targeted treatments and then match them to those patients most likely to benefit, making new therapies less costly to trial, more likely to be successfully licensed, more affordably reimbursed, and more readily adopted.

Currently there is a lot of talk about longevity: can we increase the human lifespan? At the moment, however, it is unhealthy longevity that risks bankrupting our health systems. Diseases that strike in the second half of our lives, often several at a time, with the consequent cost in human and economic terms. Precision Medicine holds the promise of reshaping our innovation ecosystem so we can target our limited resources to maximise healthy human lifespan – which should surely be the goal of every health system on the planet.

Featured image credit: Life by Huy Phan . CC0 public domain via Unsplash .

The post Unleashing the power of bioscience for human health appeared first on OUPblog.

Contrary to recent reports, coups are not a catalyst for democracy

In recent years, a new and surprising idea has emerged suggesting that coups d’état may actually be a force for democracy. The argument is surprising because coups have historically been associated with the rise of long-lasting and often brutal dictatorial regimes. During the Cold War, coups brought Suharto to power in Indonesia, military rule to Egypt, Pinochet to power in Chile, and allowed Hafez al-Assad to consolidate rule in Syria.

These and other seizures of power during the Cold War era rarely gave way to government by moderate or democratically-minded leaders, and coups acted primarily as a means to install enduring authoritarian rule.

By contrast, coups in the post-Cold War period have demonstrated a distinctive characteristic – they are much more likely to be followed by some form of democratic election within a few years. A coup in Cambodia in 1997 was followed by elections the following year, while a seizure of power in Fiji in 2000 gave way to free and fair elections in 2001. The democratically elected Honduran President Manuel Zelaya’s removal from power in 2009 was followed by fresh elections even before the year was out. Recent studies have suggested that a major reason for this new trend is that contemporary coup leaders face a drastically different international environment from that faced by their Cold War predecessors.

With the end of the Cold War, Western states and international organizations developed a strong normative preference for democracy, and increasingly used their material leverage to promote democratic development abroad. In particular, the rise of democratic conditionality created a new incentive structure for coup leaders: either hold elections, or lose the aid and trade on offer from Western democratic states and international organizations. International democracy pressure thus helps explain the rise of post-coup electoral competition.

But these arguments have oversold the link between coups and democracy in two important ways. The first problem is that elections are not a particularly good indicator of genuine democratic rule. While elections can clear a path to sustainable democracy, they may also be used by sitting incumbents to entrench authoritarian rule and facilitate regime survival rather than act as any kind of threat to it. Elections are often used as window dressing to signal the democratic legitimacy of a regime, even as the rulers rig the system in ways to ensure they don’t lose.

Coups act as a catalyst for instability and repression rather than the emergence of benign democratic rule.

When looking at measures that capture the prevailing level of democracy rather than just the presence or absence of elections, it becomes clear that most post-coup countries have struggled (or been unwilling) to consolidate genuine democratic rule.

A recent study shows that most countries that experienced a coup in the years after 1991 failed to achieve stable democratic rule, and instead consolidated some form of autocratic regime. Using a widely used 21-point democracy scale (the Polity index), we can see that the average 5-year change in post-coup democracy levels across all coup countries since 1991 was less than a single point increase. Post-coup elections may be more common, but post-coup democratic development remains rare.

A key reason for this pattern also illustrates the second weakness of the democratic coup thesis. Far from being a consistent force for democracy, the international environment can vary quite significantly from country to country, and post-coup rulers in one setting may receive a very different reaction from coup leaders in another. Not all international actors are active democracy promoters, and even those who claim to care about democracy regularly look the other way when allies or strategically important countries are involved. When Egypt’s democratically-elected president Mohamed Morsi was removed from power and arrested in 2013, the international reaction was far from united and the more punitive responses were relatively tame. Although the coup was condemned in some quarters, and Egypt was suspended from the African Union, many states voiced only muted criticism, while others offered outright support. The US refrained from describing the ousting of Morsi as a coup, which would have triggered automatic sanctions, and instead continued to work closely with the new authorities. Saudi Arabia went further and was quick to applaud the Egyptian military for its actions, and, along with other Gulf states, offered an immediate aid package amounting to $12billion. When coup leaders can count on the tacit or open support of major international powers, they are much more like to be able to resist whatever democracy pressure that is enforced by others.

There is no question that the politics of post-Cold War coups is systematically different from what has gone before, and contemporary coup leaders face a tougher international environment that their historical counterparts. But we should avoid any temptation to see this shift as ‘good news’ for international democracy or for the countries who experience these sudden upheavals. More often than not, coups act as a catalyst for instability and repression rather than the emergence of benign democratic rule.

Featured image credit: 2009 Honduran coup d’état by YamilGonzales. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Contrary to recent reports, coups are not a catalyst for democracy appeared first on OUPblog.

Marlowe, not Shakespeare—so what?

The recent media furore surrounding the publication of new findings about the authorship of Shakespeare’s works reassures us of one thing: people care about Shakespeare. Or, perhaps better stated, people care about caring about Shakespeare. A momentary venture into the ‘comments’ section to any of these news stories (a risky move at the best of times) reveals at least three camps of commentators: those who care about Shakespeare, the Stratford-born author; those who care about ‘Shakespeare’, the imagined mastermind of conspiracy theorists who ‘really’ wrote the plays (De Vere, Bacon, et. al.); and those who protest that they do not care at all about Shakespeare, but still took the time to comment. This short post is for those in the first and third camps. For the first, I want to briefly outline what is new. For both groups, I want to suggest why any of this matters.

Christopher Marlowe was and remains box office. Though one of the more shadowy figures of the period—much more has been speculated about his extra-literary activities (espionage, homosexual affairs, smoking tobacco) than is known—his astonishing retinue of plays (Doctor Faustus, Jew of Malta, Edward II, Tamburlaine) assure his place at the centre of teaching and research canons in early modern drama. His plays are often performed. His creative genius, and his murder at the age of twenty-nine, makes us wish that more of his work survived. But such wishing has no place in modern attribution research. No-one undertaking an analysis of the three Henry VI plays, for example, should begin with a desire to supplement the canon of Marlowe or Kyd or any other writer. Any such approach risks bias. So, too, skepticism is a must in the ways in which people interested in Shakespeare receive this news. Just because Marlowe’s name is printed on the title-page to these three plays in the New Oxford Shakespeare does not mean, of course, that readers must accept this unwittingly. Many won’t. But before dismissing it as a novelty, perhaps readers should cast an eye on the new research about this (Hugh Craig, John Burrows, John V. Nance, Gary Taylor). Or look over the summary of previous scholarship on the authorship of these plays in the Authorship Companion’s ‘Canon and Chronology’ essay. The new attribution of scenes and passages to Marlowe may not convince everyone, but the case for his hand in these plays has been built slowly, cumulatively, and cautiously.

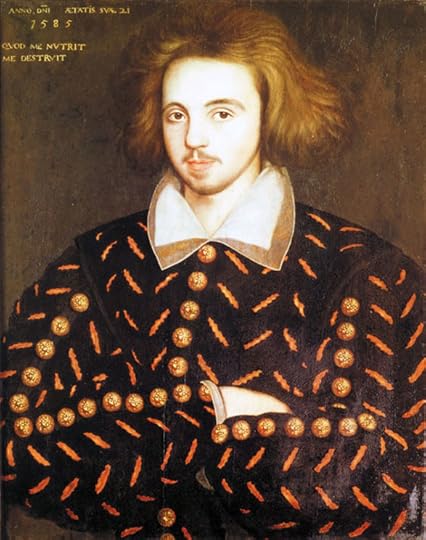

Unknown 21-year old man, supposed to be Christopher Marlowe by unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Unknown 21-year old man, supposed to be Christopher Marlowe by unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.The Marlowe news, box office as he is, buried another remarkable disclosure. Drawing upon the pioneering work of MacDonald P. Jackson, the New Oxford Shakespeare is the first edition to include Arden of Faversham in a Complete Works of Shakespeare. In his 2014 book, Determining the Shakespeare Canon, Jackson persuasively argued that Shakespeare as the author of scenes 4-9. These findings are supplemented further in the Companion by Jackson, Jack Elliott and Brett D. Hirsch. (Notably, the same modern attribution techniques that confirmed Marlowe’s presence in the Henry VI plays have disproven conjectures that Marlowe is present in this play.) Arden of Faversham is a brilliant ‘domestic tragedy’, dramatizing an infamous Kent scandal about a cheating wife, hired assassins, and a murdered husband. The Shakespeare canon is infinitely richer for its inclusion: its emotional depth, memorable if not necessarily likeable characters, tight-knit plotting, and one of the period’s longest and most complex female roles, mean it can be astonishingly effective in performance. The 2014 RSC production was praised as ‘comically sublime’ and noted that its ‘mixture of lust, greed and dark humour has a distinctly contemporary edge.’ The 2014 Indianapolis production, directed by Terri Bourus—was praised for affirming the ‘value of theatrical performance in scholarly debates about attribution.’ This play needs to been seen, heard, read, performed, and taught; its new status will surely encourage further productions and further interest.

But while we might care (or not care) about Shakespeare, why does any of this new attribution work matter? Why, in this sense, does authorship matter? It is easy, perhaps even reasonable, to be weary of the application of ‘Big Data’ to studies of Shakespeare. His plays are still taught and performed not because we can measure his distinctive use of ‘function words’ and ‘n-grams’. But if we disavow an interest in authorship, we teeter perilously on the edge of two traps. One, if we think the work stands alone, regardless of the contexts, conditions, and contingencies of its authorial provenance and transmission from script to print, we are deliberately, consciously, choosing to know less about how these masterpieces came into being. Two, if we think the authorship debate is irrelevant and choose to think of the work as Shakespeare’s alone regardless (as many undoubtedly will for the Henry VI plays), then we are in fact making a stand on authorship but just not explicitly stating it. This matters on a literary and theatrical level of analysis because if a critic identifies a thematic pattern or motif running through a co-authored play, then in fact what they have noticed is either a feature decided upon by the play’s collaborators, or it is one co-author picking up on what another author has already done. Such findings do not (necessarily) invalidate previous critical readings; rather, they add nuance, texture, and complication. But, perhaps most of all, these new findings matter because they disabuse the notion of Shakespeare as an always-solitary genius.

In our modern times, when so much work is collaborative and network-driven, surely this is an idea we can all get behind. Shakespeare’s genius is hardly in question, and he is the sole author of most of the plays and poems in the Complete Works (including his most famous texts). But such new analyses of his works demonstrate emphatically that he was a man of his time, despite Ben Jonson’s hyperbolic assertion that his peer was ‘not of an age’—like his contemporaries in the theatre trade, Shakespeare relied on the collaborative work of co-authors, companies, censors, performers, audiences, printers, and publishers. Jonson, who would have known the toil of a working playwright as well as any, probably recognized no contradiction in saying that Shakespeare was also ‘for all time.’

Featured image credit: King Henry VI, part III, act II, scene III, Warwick, Edward, and Richard at the Battle of Towton (adjusted) by Jappalang. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Marlowe, not Shakespeare—so what? appeared first on OUPblog.

The blessing of Babel

I am in Palermo, sitting on the floor of the puppet museum with a circle of teenagers. Around us hang gaudy, dormant marionettes of characters from the Orlando Furioso: the valiant Orlando and his horse Brigliadoro, his rival Rinaldo, his beloved the beautiful Angelica. Their stories are amazing, the stuff of epic and romance; but in fact the teenagers around me, all boys, have been through adventures no less extraordinary, though harsh and real. They have travelled to Palermo from many parts of Africa including Guinea, Libya, Mali, and Sudan; they have crossed the Mediterranean via smugglers’ boats, shipwreck and rescue, and it is only a few months since Sicily became their sanctuary.

Together, we are sharing words and clapping rhythms, making poems and stories. There are several different languages in the room: a lot of French; bits of English and Italian; African languages such as Xhosa, Bambara and Malinké which I do not know. So, inspired by the nonsense writing of Carroll and Lear, we put words in different languages in a heap in the middle of the circle. We arrange them into lines that please us – that have attractive sounds or seem to make a kind of sense:

Bonjour madeka grime

La luna vere mischief

L’oiseau cool go pizza

Maria riz la vache

The lines build into a nonsense narrative, a kind of modern ‘Quangle-Wangle.’ Someone chooses words from only French to make a resounding last line: ‘Le ciel va manger le soleil’ (‘the sky is going to eat the sun’).

Our workshop was part of a project, ‘Stories in Transit,’* led by Marina Warner and hosted by the University of Palermo, which enables refugees and migrants to share stories and join in fiction-making, and thereby challenges the dominant political narratives by which the migration crisis is understood. Migrants are not only the objects of news stories and asylum assessments, but also the bringers of languages and cultures which can enrich the places where they arrive. For, throughout history, moments of cultural encounter, language-mixing, misunderstanding, and translation have generated new cultural energies and forms.

Think of the American immigrant to Europe, Ezra Pound, struggling with partially understood ancient Chinese texts, with Japanese and English annotations, and emerging from the struggle with the haunting translation-poems that make up Cathay. Think of other Modernists whose work is energised by migration and the mixing of languages: Joyce, Stein, T. S. Eliot. Think of Beckett translating himself back and forth between French and English. Think of postcolonial writers such as Sam Selvon with his West Indian London English, or Chinua Achebe whose Nigerian English is layered with Igbo phrasing and terms. Think of Charlotte Brontë whose edge as a writer was honed by intense composition exercises done in French at a school in Brussels, or George Eliot whose stylistic authority was nourished by a long labour of translation from German.

Migrants are not only the objects of news stories and asylum assessments, but also the bringers of languages and cultures which can enrich the places where they arrive.

Think of Pope and Dryden with their images and cadences drawn from Latin and Greek. Think of Shakespeare, who was working in a language that had, over the previous few decades, been massively enriched via translation from the Classics and romance languages. Phrases like ‘to castigate thy pride’ or ‘Jove multipotent’ bear the marks of this translational energy (‘castigate’ and ‘multipotent’ are from the Latin ‘castigare’ and ‘multipotens’). They have something in common with ‘madeka grime’, or ‘l’oiseau cool’: they are like snippets from a chaotic multilingual dictionary.

This continual intermingling of translation and writing presents a challenge to the usual ways in which the relation between translation and literature is understood. ‘Translations are never as good as their originals’, the standard view proclaims; ‘poetry is lost in translation.’ But how can this be so if an original text itself emerges from imaginative processes that include translation, or if a translation can itself become literary classic – for instance the King James Bible?

In recent years, the English reader’s traditional hostility to translation (always, I think, more a myth than a reality) has very obviously been softening. Works by Karl Ove Knausgaard, translated by Don Bartlett, and Elena Ferrante, translated by Ann Goldstein, are massive literary hits. Could it be that translation has added something to these texts, for instance a doubling of perspectives, a layering of linguistic forms? The writing of W. G Sebald is an interesting example. As translated by Michael Hulse and Anthea Bell it takes on an air of precision and reserve: it is in English but perhaps not wholly of it. This slightly distanced tone is different from Sebald’s own German, but arguably more in tune with his narratives of migration and dislocation.

Literature can gain in translation; Babel was a blessing as well as a curse.

* Stories in Transit was funded by The Metabolic Studio.

Featured image credit: Wood cube by blickpixel. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post The blessing of Babel appeared first on OUPblog.

November 3, 2016

Place of the Year spotlight: test your knowledge of The White House

The 2016 battle for the White House has been contentious and historical. Someone new will be occupying the White House come January, and who exactly it will be is still up in the air. With the 2016 presidential election often leading international news cycles, we decided to include the White House in the running for Place of the Year. The home of the president has been a symbol of government for the United States for almost as long as its been an independent nation–but how much do you actually know about the iconic building? Take the quiz below and then vote for what you think the Place of the Year should be for 2016.

Featured image and quiz image: “The White House” by Daniel Zimmermann, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.Place of the Year 2016

The post Place of the Year spotlight: test your knowledge of The White House appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers