Oxford University Press's Blog, page 442

November 12, 2016

On Hokusai’s woodblock prints

Sometimes when looking at some piece of reality, puzzling choices have to be made when describing it as “one,” as “many” or perhaps as neither “one” nor “many.” Three woodblock prints of the artist Hokusai can illustrate the issue.

(Image 18 by Hokusai. Public domain via Marquand Library, Princeton University Library)

(Image 18 by Hokusai. Public domain via Marquand Library, Princeton University Library)

(Image 23 by Hokusai. Public domain via Marquand Library, Princeton University Library)

(The Great Wave off Kanagawa by Hokusai. Public domain via Wikimedia)

Let us start with print one.

Does this print represent seventeen things, seventeen men fighting, or does it represent a collection of men doing to, and thus in a way one thing, a collection, or does it represent eighteen things, the seventeen fighters and the individual men? None of the three options seems wrong, even if there is a preference for the first. What then does this mean? Are there three realities represented at once? Or is the collection in fact nothing beyond and above the two individual fighters, so that when we speak of the collection we don’t speak of another thing distinct from the seventeen fighters, rather we speak about nothing but he fighters. But then why do we seem to count it as something separate from the individual fighters? Or could we view a collection as many, rather than as one, as ‘the fighters’

Now let’s look at the second Hokusai print. Here we see three couples fighting with each other – or do we see just six fighters, each one engaged with fighting with one other fighter? Does this print represent three things, three couples of two fighters fighting with each other or does it represent six things, the individual fighters, though engaging with one another in a particular way? Or else does it represent the six individual fighters as well as three collections? Would that mean it represents nine things, the individual fighters and the three collections? Or is a couple of fighters nothing but the two fighters, and thus “two” rather than “one” — a collection “as two”? In that case the print would just represent six things, though divided into collections of two. In addition, the print could be described as representing a collection consisting of three things: three couples of fighters, and thus a collection of collections. Again the question arises, do these descriptions represent the very same reality or is there a difference in what the person describing is willing to accept as what is really represented, whether or not there really are such things as those collections? And why are there, as it seems just those descriptions available and not others. Couldn’t there be a third one, according to which the print represents a collection of fighters consisting in 12 single groups, each consisting of any one fighter fighting with some other fighter represented in the print. Somehow that description is hardly available, and the reason, it seems, is that only a couple of fighters fighting with each other (and no one else) should play a role.

Finally, let’s us look at the third print “mountain and waves.” What do we see here? We would say definitely one mountain, Mount Fuji. We also see birds. Now are these individual birds or a single swarm of birds? Or are these “birds in a swarm” and thus just birds without there being an additional thing that is a swarm? Furthermore, we see four waves. Or do we see just one sea, shaped into waves? Or do we see just water? Moreover, what sort of thing is water? “The water we see” is not one: we would not regard it as one thing, and we could not say “the one water we see” (but at best “the one quantity of water we see”). “The water we see” moreover is not many. We could not possible regard it as many things, and we could not say “many water,” but at best “many quantities of water” or “many drops of water.” But then the water that is represented would be neither one nor many. Why do we like to see one mountain, many birds, and four waves or else just water? Again we could imagine other descriptions (“several mountain parts” “several bird groups” “a single four wave-group”), but we resist applying them, and yet we would not be strictly wrong describing things in those other ways. What then makes us prefer one such description over another? That is, what makes us see something as one, as many, or as neither one nor many? Or should we say, what makes something be one, many, or neither one nor many?

Featured image credit: “Hokusai Boats & Moon” published by Yohachi, c. 1833. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post On Hokusai’s woodblock prints appeared first on OUPblog.

November 11, 2016

Home-coming

At the intersection of State and Washington Streets in the Warehouse District of downtown Peoria, a city of about 116,000 that sits halfway between Chicago and St. Louis, stands a nine-foot-tall bronze likeness of the city’s most infamous native son. If you were a visitor, in town to hang out along the up-and-coming riverfront or to visit Caterpillar, the only Fortune 500 company headquartered in the city, you would be forgiven for thinking this makes sense, that of course Peoria would memorialize Richard Pryor arguably the most culturally significant Peorian of all time, and inarguably one of the most significant figures in African American cultural history of the twentieth century. As a visitor, you might not be aware that this homage to Pryor, erected almost ten years after the comedian’s death, was years in the making—and that its official name,“Richard Pryor—More Than Just a Comedian,” is ultimately an artifact of Peoria’s belated attempt at reconciling the foul-mouthed, woman- and drug-abusing comedian-cum-social critic with an image of itself as a model American city.

I was born forty years after Pryor into a Peoria that seemingly wanted to rid itself of any memory of its singular superstar. I consequently had little frame of reference for Pryor until after I left home for college when I came to know that for many people, particularly black folks, he was often the only point of reference for my hometown. Among the things Pryor opined about Peoria, was that it’s only a model city insofar as it “had the niggers under control.” This sort of quip did nothing to endear Pryor to his hometown critics, but when you consider that in the past several years Peoria has been designated both an and one of the ten worst cities for black Americans, the prescient guerilla intellectualism underlying Pryor’s act is brought into sharp relief.

I was raised in a Christian household shielded from much of what Pryor came to know intimately in his childhood, which was spent in brothels owned by his grandmother, Marie Carter. While Pryor might seem an inordinate point of departure for me, a church-girl-turned-college professor, it is in his brazen commentary and his obscene, autobiographical, profanity-laden stage routines that I have found something of a life I know—something that the conventions of academia can sometimes gesture toward but for me, have only been fully embodied in the place I know of as home.

Peria City Hall by Robert Lawton. CC BY-SA 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.

Peria City Hall by Robert Lawton. CC BY-SA 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.I came up “down the hill” on Peoria’s predominately black South Side which, like most such places, is the most economically depleted, resource-deprived neighborhood in the entire city. Then and now the South Side is largely seen as Peoria’s site of consummate failure, the place from which one must flee in order to be understood as successful or “upwardly mobile.” Then and now the South Side is talked about as a neighborhood almost wholly given over to criminality, where one’s life might be snuffed out at any given moment. Then, and most certainly now, certain political figures imagine that what it must be like to live in communities like the South Side , is reducible to “hell,” as if our lives are conditioned by nothing other than absolute terror, as if all we need is a savior to come rescue us from ourselves.

Literary scholar Hortense Spillers reminds us in her essay “The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual: A Post-Date” that just because we do not live in a place doesn’t mean that we are not of a place. Here, then, is Pryor’s truest legacy. While he might have mocked and critiqued Peoria, he never held himself apart from it. Indeed, what others took as the detritus of black life he took as its very substance, and in his 1994 autobiography, Pryor Convictions, he argued that people like hustlers, prostitutes, winos, and pimps who he grew up with and who he continued to surround himself with throughout his life, were people who “knew stuff worth knowing.”

Perhaps for those who know nothing of what it means to live on the “black side” of town, it is difficult if not impossible, to imagine that people like Peoria’s black South Siders—who aren’t just thugs and gangsters but are like my mom, bookkeepers, like my best friend, nurses, like my stepdad, business owners and everything else in between —know something worth knowing. What they know is that while their lives ain’t no parts of easy, they are fundamentally irreducible to their worst days or their saddest moments. What they know is that black social life is life that is lived in spite of.

If you believe the rhetoric about the “inner city” that would suggest boarded up homes, broken down schools, food deserts and chronic joblessness means that we don’t have joy here, that we don’t have self-love here, that we don’t have fellowship here, that we don’t have scholarship here, or that we don’t have safety here, then, as the wino said to the junkie (in a Pryor skit), “that shit done made you null and void.” While “hood life” certainly does not always acquiesce to the demands of the state or the protocols of the “proper,” although very often it does just that, it is this very capacity for fugitivity, or what we might otherwise call making a way out of no way, that is, the very enabling condition of home, and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Feature Image Credit: Downtown Peoria from Air (Detail) – 1967, taken on August 17, 1967 by Roger W. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Home-coming appeared first on OUPblog.

Ending violence against children

Earlier this year, the first-ever nationally representative study of child maltreatment in South Africa revealed that over 40% of young people interviewed reported having experienced sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse, or neglect. This figure is high, but it is not unusual: similar studies on violence against children have been conducted across 12 other countries, with many revealing equally high rates.

Last year the UN General Assembly committed to the Sustainable Development Goals, which include ending abuse, exploitation, trafficking, and all forms of violence against children, and setting a number of goals targeting the risk factors for maltreatment (for example, goals for good health, quality education, and gender equality). Just over one year after the adoption of these Sustainable Development Goals, it is imperative that global leaders consider these figures and understand the urgent need to take decisive action to keep children safe.

However, while the current statistics are bleak, there is hope that with reliable data, national leaders have the opportunity to make real progress in improving the well-being of children. Provided with better data on the problems, countries may now draw on the growing body of evidence that has deepened our understanding of violence and how to prevent it, learning lessons about how to turn scientific evidence into effective policy. With the right support and investment, middle-income countries are well-positioned to lead the way.

School girl by Alex Serafini for Centre for Justice and Crime Prevention. Used with permission.

School girl by Alex Serafini for Centre for Justice and Crime Prevention. Used with permission.Take the case of South Africa. Like many countries, it has excellent laws and a national action plan to prevent, and respond to, violence against children; it has a clear indication of political will. However, laws and policies on their own are not enough: without enforcement, they are meaningless. This child maltreatment is where South Africa, like many others, falls down. For instance, corporal punishment is banned in South African schools – yet half of its students report having experienced corporal punishment at the hands of an educator. The study also found that young people tend not to report instances of maltreatment, and that when they do, the services – social, police, criminal justice, and health services – are not as efficient or effective as the policies clearly intend them to be.

While these facts are troubling, they also build a case for the path forward. What is needed is a clear protocol across the myriad agencies involved for the treatment, referral, and management of cases of child abuse, as well as support for the victims as they make reports. Such a protocol would improve service delivery; making it easier and more likely that young people would report maltreatment, and go a long way to preventing recurrences.

The study also provides a roadmap for how South Africa can ensure that young people who have been victimised will not go on to experience disabling consequences. It reveals that young victims of maltreatment are twice as likely as other young people to suffer anxiety or depression; three times as likely to report post-traumatic stress disorder; and more likely to report problems in schoolwork, high-risk sexual behaviour, and substance misuse. All of these can have serious long-term impacts on young lives. However, appropriate treatment through health and mental health services can make all the difference, either by preventing the consequences of violence, or providing early treatment before they develop into serious, intractable problems. Schools can be a key referral pathway here, by attending to young people who have sudden changes in their schoolwork and referring them on to professionals.

Finally, the study identified how strong action could prevent the maltreatment of children from happening in the first place. Parents are a key focus for prevention efforts as children who reported victimisation were far more likely to have parents who misused drugs and alcohol than children who did not; and children whose parents had warm relationships with them, and who knew where they were and who they were with, were far less likely to report maltreatment. This suggests that scaling up substance abuse prevention, treatment efforts, and effective, evidence-based parent skills training programmes would go a long way in preventing violence against children.

…scaling up substance abuse prevention, treatment efforts, and parent skills training programmes would go a long way in preventing violence against children.

Now that it has a better understanding of the problem, South Africa and the other countries with nationally representative studies have the opportunity to take a range of concrete actions to prevent violence against children and demonstrate how progress may be made. In doing so, these countries may be inspired by a growing community of international and national leaders who recognise and embrace the critical challenge of preventing violence against children and the necessity of investing political capital to make that happen. In July, a new global partnership to End Violence Against Children was developed by the World Health Organization and other partners; launched to catalyse action, it calls for pathfinder countries to demonstrate the way forward by implementing a set of strategies proven to reduce violence and its impact on the lives of children. These strategies (known collectively as INSPIRE) include promoting parenting skills and empowering families economically, as well as improving the emotional development of children and their access to health care. It also includes recommendations for laws and social norms that protect children, as well as challenging the gender stereotypes that can normalize violence.

Preventing violence against children has been a neglected issue, but today we have reached an unprecedented point of opportunity. We now have better data than ever before on the full extent of the problem, and a growing base of evidence on what needs to be done to prevent it. It is time for action.

Featured image credit: School chairs by Alex Serafini for Centre for Justice and Crime Prevention. Used with permission.

The post Ending violence against children appeared first on OUPblog.

Translating Hobson City

While we still haven’t figured out a way to reproduce all of the excitement of the OHA Annual Meeting on the blog (see our most recent attempt here), we have figured out how to bring you a sampling of some of the exciting projects oral historians are working on. Below, we bring you a short version of Margaret Holloway’s paper from the conference, “Translating Hobson City, Alabama: An Ethnographic, Rhetorical, and Technological Approach.” Holloway is using oral history to preserve the memories of Hobson City, Alabama and help it survive into the future. If you are interested in contributing to the blog, email our social media coordinator, Andrew Shaffer, at ohreview[at]gmail[dot]com.

Crossing the train track from the predominantly white Anniston into the historically black Hobson City, Alabama, I immediately noticed the significant changes in environment and people. It was not until I exited my car and physically inserted myself into the Hobson City community that I learned that there was much more to this small town than what initially met my eyes.

Hobson City, Alabama is the oldest incorporated African American town in the state. The town is a part of a larger nationally recognized organization called the Historic Black Towns and Settlements Alliance, which includes Tuskegee, AL, Mound Bayou, MS, Grambling, LA, and Eatonville, FL. Hobson City is located right in predominantly white Anniston; the only thing that separates the two towns is a train track. The train track serves as a national marker that symbolizes segregation along with differences in socio-economic statuses within communities. Over the past two years, I have learned about the town’s rich African American origins, significant political events, and entrepreneurial pioneers of Hobson City that make this place a historical black town.

In May of 2016, I conducted an oral history interview with one of the town’s most significant citizens, Mr. Montressor Sudduth. A native of Hobson City, he is the middle child of three children, with an older brother and a younger sister. He was raised in a single-parent home by his mother. His story is rooted in the early beginnings of Hobson City, Alabama and his contributions to the town live on to this day.

An important theme in this interview was the park as a site for community fellowship and engagement. Mr. Sudduth spoke about how there used to be a swimming pool, a bowling alley and baseball field all at the park. The present park in Hobson City includes a playground, a field that could serve as a football field, and an old basketball court. The park that Mr. Sudduth spoke of in the interview was called the Booker T. Washington Park. I am not sure why this park dissolved but it was the nucleus of all community gatherings in the 50s and 60s.

Mr. Sudduth attended Miles College in Birmingham before working in a foundry in Anniston. While at the foundry he persuaded two of his friends to start a disc jockey group, which they called Stop Slicking the Wicked. The group developed their DJ skills before the disco wave so once disco became popular they were “prepared…ready for the game.” In between his time at Miles and his time as a foundry worker he landed an opportunity as a broadcaster. He stated that he “fulfilled the need for minority broadcasters…at that time FCC was opening doors for minorities to go into broadcasting.” That is how he landed a midnight DJ job at one of the top rock stations. Mr. Sudduth worked as a DJ for a number of years until he and his friends decided to open a record store. The store was located downtown on Noble Street and was the 2nd or 3rd black owned business in Anniston. To this day, Mr. Sudduth works as a DJ for the local radio station that serves the Hobson City area, WGHOM-am 1120 am. His group, Stop Slicking the Wicked, was one of the first to perform on WEN radio station, 107.7 which covered the entire state, from Mobile to Huntsville.

Mr. Sudduth continues to contribute to the historical richness of Hobson City, Alabama. He continues to leave a lasting mark by working at the only radio station that serves the Hobson City area. His presence and service helps preserve the history of this historical black town. Mr. Sudduth takes pride in being a professional, the son of a wonderful mother, a black business owner, a DJ, and a product of Hobson City. At the conclusion of our interview I asked Mr. Sudduth if he had any last thoughts that he wanted to share. He said “if you don’t see life giving you what you want, go out there and get it yourself. Design your life the way you want to design your life. Don’t let no one else design it for ya.” Those words exemplified how Mr. Sudduth lived and continues to live his life. He journeyed through life while making his own personal and professional choices and to this day he continues to contribute to the rich history of Hobson City.

Photo by the author, used with permission

Photo by the author, used with permissionThe town established six goals in hopes of gaining access to human and capital resources, so that the town can return to a state of rich economic livelihood. Two of those goals are 1) recovering community histories and 2) achieving National Registry recognition. Collecting oral histories has accomplished the first goal and will hopefully help achieve the National Registry goal.

My oral history is the result of a class project from a course offered in the English Dept. at the University of Alabama taught by Dr. Michelle Bachelor Robinson. The class conducted a total of 14 oral histories with citizens of the town who were selected based on their contributions and significance to the town’s history. For my dissertation, I will conduct 2-3 more oral histories to add to that collection. Oral history plays a major role in gaining National Registry recognition because it recovers, rescues, and (re)inscribes (Royster and Kirsch) the stories that are not written in history books. Oral history allows others to hear and read about underrepresented stories that come out of towns such as Hobson City. It can be used to foster conversations across disciplines, across geographical locations, and across cultures on the importance of rescuing Historical Black Towns that have been marginalized, silenced, and dismissed in American history.

My dissertation goal is to create a digital space using a web platform that will house all of the research where I have assumed the role of either primary investigator or co-investigator for the entire Hobson City project. This space will serve as a digital preservation site for the town and will include the oral history projects, the Photovoice project and the cemetery and genealogy research. My target audiences for this digital space include the citizens of Hobson City, the HBTSA, The University of Alabama, and The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill who established the partnership with the HBTSA.

Chime into the discussion about aurality in oral history in the comments below or on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, or Google+.

Featured image: “Tracks” by Kevin Moreira, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Translating Hobson City appeared first on OUPblog.

Why didn’t more women vote for Hillary Clinton?

Hillary Clinton was confidently predicted to ‘crack the country’s highest glass ceiling once and for all.’ In Rochester, New York women queued up to put tokens on the grave of Susan B. Anthony, the nineteenth century suffragist and architect of the 19th amendment to the US constitution which gave federal voting rights to woman in 1920 (they had been voting in territories and states since 1869).

Well, Tuesday’s election certainly saw a breakthrough but it wasn’t for Clinton and it wasn’t based on gender, despite confident predictions that women or men were going to swing the vote for either candidate

If gender was going to be the determining factor, this was the election where it should happen. Clinton was a respectable public servant, wife and mother. Trump was the epitome of swaggering masculinity, bragging in an Access Hollywood bus of the most gross expressions of gendered bad behaviour. No one, male or female, minimised this. But the expectation that it would create a political earthquake and shame him out of the race was utterly wrong. In fact, his ability to ride through and surmount this and other proofs of his personal failings made him a stronger candidate. This should have been no surprise. In the 1990s when moralists were out for Bill Clinton’s blood because of his failings as a husband, his poll ratings stayed high. This was a president under whom there was prosperity at home and peace abroad, voters male and female could tell the difference between personal behaviour and politics.

It was not a new lesson: Grover Cleveland in the unforgiving nineteenth century produced a child out of wedlock while in the White House but still went on to win a second term – and, indeed, to be the only president in history to win two non-consecutive terms, despite his opponents’ jeers of ‘Ma, ma, where’s my pa?’

Hillary Clinton, by Gage Skidmore. CC BY SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Hillary Clinton, by Gage Skidmore. CC BY SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.The campaign for women’s votes tells us the paradoxical truth that in politics, gender doesn’t matter. In 1893 Colorado’s men voted for women’s suffrage in a referendum despite the predicted crisis of masculinity warned of by the opponents of ‘petticoat government.’ Disaster failed to arrive, but neither did the period of harmony and social justice promised by the proponents of women’s voting. A taste of the future was remarked on by Federal Judge Moses Hallett: ‘the presence of women at the polls has only augmented the total votes, it has worked no radical changes. It has produced no special reforms, and it has had no particularly purifying effect on politics.’ A woman reporter from the San Francisco Examiner who went to Colorado to report on the supposedly monumental changes wrought by this gender revolution lamented, ‘we women have found out that our politics are just as corrupt as men’s politics, they are just a little bit trickier if anything.’

This last comment brings to mind the anonymous Republican grandee’s comment on Hillary Clinton: ‘Whoever you are, she’s smarter than you, and meaner than you.’ That’s a comment about a person, not about gender. What was true of women’s voting has also been true of women’s participation in politics. Men and women politicians have identically peddled the same rhetoric, and risen and fallen by it. Hillary Clinton did not fail because she was too radically female, but because she was too conventionally part of a political establishment that had become despised.

What we saw in the electoral contest, despite the media’s incessant personalisation of the contest, was a genuine battle of priorities in which Hillary Clinton the experienced politician lost every time. Trump talked about fears over immigration, the broken economy, a putrid political class and America’s over-engagement in military adventures abroad. Clinton offered more of the same. omen voted on the issues, and non-college educated women, whose jobs are most threatened by globalisation (as are those of non-college educated men), notably supported Trump. There is ample room to say voters were misled and Trump cannot deliver what he promised, but that would apply to male and female voters. They made their choices on the issues put before them.

Cracking glass ceilings is an attractive goal for elite women, but if they want to bring less privileged women (and men) along to accomplish this task, they need to address their real concerns.

The post Why didn’t more women vote for Hillary Clinton? appeared first on OUPblog.

Three centuries of the American presidency

The following is an extract from The American Presidency: A Very Short Introduction and looks at 3 elections for each century since the American presidency began, and how it’s changed from then.

The United States and its Constitution are now in their third century. The passage from each century to the next has been eventful. The election of 1800 was bitter and personal. The contest was between two incumbents: John Adams serving as president, Thomas Jefferson as his vice president. Much of the campaign was carried on in the partisan press. Jefferson won with seventy-three electoral votes, but his running mate, Aaron Burr, had an equal number of votes. Burr refused to concede and it took thirty-six ballots in the House of Representatives for Jefferson to win. As a result, power was transferred from the Federalists to the Democratic-Republicans.

The election at the turn into the twentieth century was a rematch between the incumbent Republican president, William McKinley, and the Democratic populist William Jennings Bryan. Many of the difficult issues associated with changes from an agrarian to an industrialized society were being accommodated, if not resolved. New problems were developing that were related to a larger world role for the United States. McKinley, who hardly campaigned, was reelected easily but not overwhelmingly. The two-party system continued to face challenges from third parties, notably the Progressives in the early years of the new century. With McKinley’s death by assassination in 1901, a dynamic successor, Theodore (“Teddy”) Roosevelt, shouldered the country into the new century.

The 2000 presidential election joined these other “turn of the century” contests as being historic. Democratic Party dominance of Congress had been broken six years earlier, and the election of George W. Bush brought to Washington the first all-Republican government in nearly fifty years. Bush’s election was among the most contentious in history, showcasing, as it did, sour relations between an impeached President Clinton and the Republican Congress, and the frustrations of Democrats serving in the minority. Having the election settled by the Supreme Court and Bush losing the popular vote added to an intensely partisan mood in the nation’s capital carrying through to the Obama presidency.

These three contests also reveal changes in the presidency. The president’s constitutional authority has remained essentially the same, but the circumstances under which this authority is exercised are dramatically different at each century’s end. The presidency was being formed when Jefferson was inaugurated. It was more a person than an institution, with the incumbent seeking to comprehend the extent and meaning of his powers. Washington D.C-The White House by Stefan Fussan. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

Washington D.C-The White House by Stefan Fussan. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

By 1900 the presidency was beginning its ascendancy. Congressional Government, as Woodrow Wilson titled his treatise in 1885, could manage the issues of an agrarian society. Industrialization and growth of the world economy required the professionalism of bureaucracy, hierarchy, and executive control, including that by the chief executive. Take-over President Theodore Roosevelt welcomed these responsibilities, as did Woodrow Wilson and Franklin D. Roosevelt. Other presidents of the first third of the century, Taft, Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover, were less moved to embrace an expansive view of presidential power. Still the die was cast. From FDR forward, the presidency would grow in status, influence, and structure.

In two hundred years, the presidency had changed from that of a person—Washington followed by Adams, then Jefferson—to a presidential enterprise with a cast of thousands. Richard E. Neustadt expressed it this way as he reviewed The President at Mid-Century: “President and presidency are synonymous no longer; the office now comprises an officialdom.” The White House remains the symbolic location of the presidency but it can house only a small portion of the presidential workforce. Accordingly, George W. Bush’s principal task as president-elect in 2000 was to fill jobs, beginning with a personnel director.

This review suggests an important lesson in considering the presidency in the twenty-first century: Events, the issues they generate, and the people who serve are normally more important than reforms in explaining change. Neustadt again: “The presidency nowadays [has] a different look. … But … that look was not conjured up by statutes, or by staffing. These, rather, are responses to the impacts of external circumstances upon our form of government; not causes but effects.” This lesson should not come as a surprise. After all, the presidency is a vital institution in a representative democracy. As such it may be expected to respond to events, and this includes making adjustments so as to function more effectively.

Featured image credit: American flag by Sam Howzit. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Three centuries of the American presidency appeared first on OUPblog.

November 10, 2016

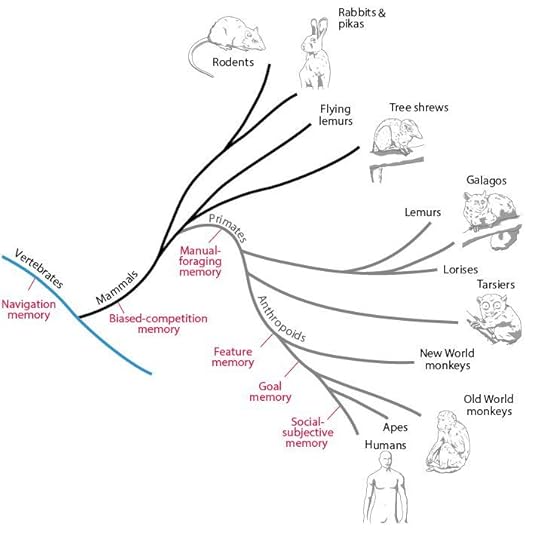

The evolution of human memory

Like all biological traits, human memory reflects a long evolutionary history, most of it shared with other animals. Yet, with rare exceptions, evolution has either been overlooked in discussions of memory or treated in an outdated way. As a result, a simple idea about the cerebral cortex has reigned for more than a century: that its various areas specialize in functions characterized as memory, perception, the control of movement, or executive control (mainly decision-making). By taking a contemporary view of brain evolution into account, however, it’s clear that the brain simply doesn’t work this way.

Instead, evolution has led to different parts of the cortex specializing in distinct kinds of neural representations, many of which evolved during major evolutionary transitions. Representations, in this sense, correspond to the information processed and stored by a network of neurons, and they underpin our memories as well as our ability to perceive the world and control our actions.

Several representational systems built up during evolution, with each new system adding to those inherited from earlier ancestors. These systems arose for the same fundamental reason: to transcend problems and exploit opportunities encountered by specific ancestors at particular times and places in the distant past. In effect, modern memory emerged via evolutionary accretion.

…with rare exceptions, evolution has either been overlooked in discussions of memory or treated in an outdated way.

Our examination of brain evolution has led to the identification of seven representational systems in the human brain:

Reinforcement-learning systems evolved in early animals. All modern animals have inherited this diverse collection of brain mechanisms, and they interact with representational systems that evolved later.

The navigation system evolved in early vertebrates. It originally provided advantages in navigating along novel paths using map-like representations, but it later adapted to a wide range of behaviors. Some of the oldest parts of the cerebral cortex specialize in such representations.

The biased-competition system evolved in early mammals, based on a new kind of cortex that emerged in these animals: neocortex. This representational system dealt with information that enabled early mammals to regulate older systems when they competed to guide behavior.

The manual-foraging system evolved in early primates. Housed in a suite of new cortical areas, it guided the choices and actions that enabled early primates to reach for, grasp, and manipulate items of value in the thin branches of trees.

The feature system evolved in anthropoid primates. It improved the perception and memory of both the qualitative and quantitative features of their world, which guided long-distance foraging as they became larger, farther ranging animals. New parts of the parietal and temporal lobes, along with some older areas, provided this advantage.

The goal system evolved a little later, in new parts of the frontal lobe that emerged in anthropoids. It generated goals—the targets of action—from representations of goal-related events, as well as from abstract strategies. Yet later, during human evolution, the feature and goal systems began to perform more-general functions, resulting in sophisticated reasoning, symbolic communication, and mathematics, along with the generalizations, concepts, and categories that underlie semantic memories.

Early humans developed new kinds of representations of themselves and others: a social–subjective system . Once these new representations began to interact with older ones, our ancestors developed a sense of participating in events and knowing facts, the hallmarks of autobiographical memories and cultural knowledge.

As humans, we have an ancestry stretching back hundreds of millions of years: a direct line of descent, parent to offspring, over countless generations. The figure below depicts some of our closest relatives, and it highlights the fact that we are many things besides Homo sapiens. We are also anthropoids, primates, mammals, and vertebrates, among other things. By embracing all of our ancestors we can both enlarge our identity and develop a deeper appreciation of how evolution produced our memories, our complex cultures, and the stories of our lives.

Adapted from Mary K. L. Baldwin, Dylan F. Cooke, and Leah Krubitzer. Intracortical microstimulation maps of motor, somatosensory, and posterior parietal cortex in tree shrews (Tupaia belangeri) reveal complex movement representations via

Cerebral Cortex

, 11 January 2016. Used with permission.

Adapted from Mary K. L. Baldwin, Dylan F. Cooke, and Leah Krubitzer. Intracortical microstimulation maps of motor, somatosensory, and posterior parietal cortex in tree shrews (Tupaia belangeri) reveal complex movement representations via

Cerebral Cortex

, 11 January 2016. Used with permission.Featured image credit: Old Vintage by kaboompics . CC0 public domain via Pixabay .

The post The evolution of human memory appeared first on OUPblog.

The complex world of climate change governance: new actors; new arrangements

Climate change governance dramatically challenges traditional International Relations (IR) notions of decision-making. The greatest challenge involves understanding the many ‘actors and the arrangements’ that describe this critical global governance issue. The field is made up of much more than the traditional intergovernmental and international organizations and their actions in a critical global issue. For some time, IR experts have been cataloguing the many non-state actors (NSAs) that have become a part the most challenging of global order matters – global climate change. Today there are individuals, private and public corporations, non-governmental organizations, transgovernmental organizations and networks, to name a few. My colleagues have described the hybrid nature of governance and have sought to capture the mixed character by terms such as regime complex (Keohane and Victor, 2011).

But the story of climate change efforts to substantially reduce carbon emissions goes beyond the identification of this new hybrid world. Even more dramatically, perhaps, is the consequences of chance and personal networks in the evolution of global policy-making. The story begins with a governmental position held by a notable academic in the UK. He represents a central element in this narrative. Sir David King served as the Chief Scientific Advisor from 2000 to 2007 and then in 2013, was made the new permanent Special Representative for Climate Change. There, Sir David witnessed the feed-in tariff success (feed-in tariffs are governmental subsidies for renewable energy – wind and solar, for example) in the UK, Germany, and also in California. The price of renewable energy tumbled. The program was so successful, according to Sir David, that the UK found it possible to eliminate the subsidy for all but offshore installations. But there were problems nonetheless, most particularly, but not only, the inability to store successfully renewable energy.

Undaunted, Sir David along with a number of well-known economic colleagues including Sir Nicholas Stern and Lord Layard and other notables including Baron O’Donnell, Lord Turner, Lord Browne, and Professor Lord Rees launched an initiative – the Global Apollo Project. This initiative, initially launched (June 2015) without a government imprimatur, was intended to be a global science and economic research program on clean energy technologies with the goal of making carbon-free electricity less costly than electricity from coal by the year 2025.

As stated this initiative was launched without firm governmental support. But chance appeared. In India, Narendra Modi was elected prime minister. The new Indian prime minister was keen to bring solar power to India and Sir David was invited to India to discuss issues with the Minister of Energy and, as it turned out, to discuss the Global Apollo Program with the new Prime Minister. The new Indian Prime Minister, according to Sir David, was enthusiastic about initiative but was not so keen on the name. And in fact the name was ultimately altered to Mission Innovation, where it was first discussed by Energy Ministers in the run up to the German G7 meeting at Schloss Elmau and it was identified in the Leaders’ declaration.

beach wind farm bangui by sonnydelrosario. Public domain via Pixabay.

beach wind farm bangui by sonnydelrosario. Public domain via Pixabay.Chance intervened again. At the launch of the Project, Sir David Attenborough, broadcaster and naturalist, expressed support for the effort. As it turned out Sir David Attenborough attended at the White House some 2 weeks later, not to interview the President of the United States, Barack Obama but in fact to be interviewed by him. And this allowed Sir David to ask him about US support for the Project, which the President indeed expressed.

And so by the time of the Paris COP21 meeting on Climate Change, specifically 30 November 2015 , a “Joint Launch Statement” was issued by 20 governments that identified Mission Innovation (MI). This Statement indicated that these governments were committed “to double governmental and or state-directed clean energy research and development investment over five years. New investments would be focused on transformational clean energy technology innovations that can be scalable to varying economic and energy market conditions that exist in participating countries and in the broader world.” And then, in turn, Ministers from these countries met in San Francisco in June 1, 2016 where Ministers once again expressed support and issued an “Enabling Framework” for MI.

Real commitment. But these actions, as valuable as they might prove to be, would not have represented a unique set of actors or arrangements. MI was an intergovernmental entity. But here yet once again chance intervened, for in the summer of 2015, Sir David received a call from Bill Gates of Microsoft fame. Gates indicated that he was prepared to provide up to $1 billion dollars of his own money – not as a donation – but as part of a venture capital commitment, because Gates believed the innovation here could make a significant innovative advance and could generate profit as well. Gates then went about soliciting other technology` innovators and venture capitalists, including Mark Zuckerberg and his wife, Priscilla of Facebook, Tom Steyer of NexGen, Jack Ma of Alibaba, Marc Benioff of Salesforce.com, Saudi prince Alwaleed bin Tala, Richard Branson from Virgin Group, Meg Whitman from HP and others, all joining together to create Breakthrough Energy Coalition (BEC). These venture capitalists came together to create, as they suggested in their Investment Principles, and to underscore that: “Technology will help solve our energy issues. The urgency of climate change and the energy needs in the poorest parts of the world require an aggressive global program for zero-emission energy innovation.” It seems that BEC will have $2 billion initially to invest and it would seem, that the first initiatives will be announced at the next COP meeting, COP22 at Marrakech in November.

So there, then, a new model of energy action bringing together a public and private partnership between governments, research institutions, and investors. In the Investment Principles of the BEC, the members expressed the design and goal for the Coalition:“… a partnership of increased government research, with a transparent and workable structure to objectively evaluate those projects, and committed private-sector investors willing to support the innovative ideas that come out of the public research pipeline.”

New actors; new arrangements built in part on chance and personal networks. Will they succeed? For that we will need to turn our attention to their efforts to curb global carbon emissions.

Featured image credit: alternative cell clean by PublicDomainPictures. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post The complex world of climate change governance: new actors; new arrangements appeared first on OUPblog.

The economic effect of “Trumpism”

Trumpism is defined as: (1) the rejection of the current political establishment and the vigorous pursuit of American national interests; (2) a controversial or outrageous statement attributed to Donald Trump.

On winning the US Presidential election, Trump’s victory speech confirmed that he would put America first in his policies. That pursuit of America’s interests will permeate US economic and other policies in the years to come.

US President Donald Trump’s effect on the economy is hard to discern due to a lack of policy detail, but there are three main areas to watch: fiscal, monetary, and foreign including trade policy. In each area, there is potential for significant change. But, as with all public policies, there will be a trade-off that is yet to be dissected. For instance, he’s vowed to double America’s growth rate, critiqued the Fed, and expressed protectionist views. How will he achieve those aims? And at what cost?

Firstly, America’s economic growth has been slower than before the 2008 financial crisis. There are underlying trends that have led economists to debate whether the US, and other advanced economies, are facing “secular stagnation”. It’s a term first coined by Alvin Hansen in the 1930’s and recently revived by Larry Summers, which captures the notion that America may face a slower growth future.

Trumpism’s first aim will be to raise economic growth, and the policy to be deployed to achieve that goal is to cut taxes and reduce regulation. But would that square with his desire to reduce America’s debt? The independent Tax Policy Centre, jointly set up by the Brookings Institution and the Urban Institute, estimates Trump’s plan will double the growth in federal debt.

Will Trump be able to justify that trade-off in his fiscal policy? Of course, his plan to cut business taxes from 35% (which is among the highest in the OECD) to 15% (which would be among the lowest), as well incentives to increase investment, may be welcomed by businesses who voted him into office.

The Tax Policy Centre also concludes that Trump’s plan would actually increase and not decrease the tax burden on middle class Americans, while cutting taxes for the better-off and corporations. Given the stagnant median wages that have squeezed the middle class, economic growth that does not raise incomes for the average American is less than desirable. The American consumer also drives the global economy, so there are wider implications.

Donald Trump, by Gage Skidmore. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr

Donald Trump, by Gage Skidmore. CC BY-SA 2.0 via FlickrSecond, and perhaps one that’s important for markets is what happens to the Fed. Trump has criticised the Chair of the US central bank, Janet Yellen, for acting in a politicised manner. It has led to concerns over the independence of the Federal Reserve as well as whether Yellen will remain in post until February 2018.

That adds prolonged uncertainty on top the near-term economic uncertainty caused by the scant details of Trump’s economic plans. The dramatic market movements where the US benchmark stock index, S&P futures, fell so far it hit its bottom limit, as well as the plunge in the value of the dollar reflected the concerns of investors. Indeed, markets have downgraded the prospect of an interest rate rise next month to 50-50.

But the most significant market movements were seen in emerging markets; notably Asian stock markets and the Mexican peso give an indicator of how emerging economy currencies were unsettled by Trump’s foreign and particularly trade policy.

Trump has said that he will revisit trade policy, including withdrawing from NAFTA if the agreement doesn’t benefit America, consistent with his philosophy of putting America first. This is an area where the President has the unilateral power to re-negotiate and even withdraw from trade agreements – congressional approval is needed to enter into free trade agreements (FTAs), but is not required to pull out. The same goes for the imposition of some tariffs, which President George W. Bush did on steel, until he was pulled back by the World Trade Organisation.

In a world economy that it already experiencing weak trade growth, a more protectionist US president is certainly worrying for the rest of the world, many of whom rely on selling to the vast American market. For Asian economies in particular, growth depends a great deal on exports, including to the US.

The immediate reaction to Trump’s surprise victory – polls predicted a Hillary Clinton win when the voting began – was a dramatic fall in global markets, which reflected this surprise but also an underlying concern about where America is headed. Those market declines were moderated as the news sank in.

But what happens next will depend on the policy specifics around Trumpism.

Until we get more detail, there will be economic uncertainty about America, and by extension, the global economy. And that tends to be unsettling.

Featured image credit: Donald Trump, by Gage Skidmore. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The economic effect of “Trumpism” appeared first on OUPblog.

November 9, 2016

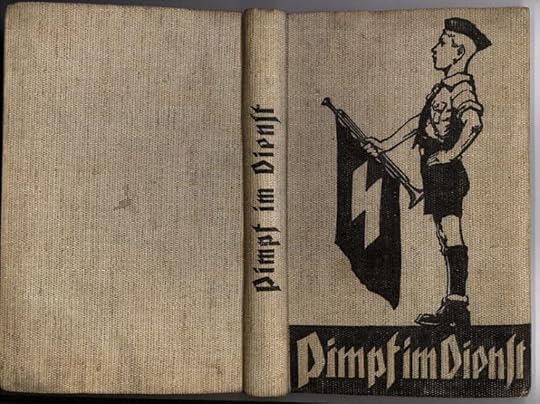

“Fog” and a story of unexpected encounters

“Fog everywhere. Fog up the river,… Fog down the river….” This is Dickens (1852). But in 1889 Oscar Wilde insisted that the fogs had appeared in London only when the Impressionists discovered them, that is, they may have been around for centuries, but only thanks to the Impressionists, London experienced a dramatic change in its climate. In my present capacity, I’d rather side with Dickens, because in etymology fog is indeed everywhere: up the river and down the river. Fog itself is a word of obscure origin, and, indeed, how could a word with such a meaning be transparent? If it were, it would not have been called fog.

The Impressionists introduced mists to London.

The Impressionists introduced mists to London.Please pay attention to the part of the title dealing with encounters: it is there for a reason. Fog has at least two meanings: one that is common (“a thick mist”) and one that is local “a thick layer of dead grass left as fodder; aftermath”; the latter is also known as fagagio. Fog 2 is current mainly or exclusively in the North, but, judging by the records in our texts, it is an old word. As could be expected, some people think that the two meanings of fog are connected, while, according to the others, they are not. I have little doubt that the first hypothesis is correct. My conviction is based on something I know from Russian. In that language, there is the noun par. It means “vapor,” something not too different from fog, which, after all, is also a cloud of water droplets. But, additionally, par means “land (or field) left to recover from the past year of cultivation”; such a field is also called being “under par” (pod parom). In the linguistic intuition of most Russian speakers, the two senses are probably not related. Yet both words—par1 and par2, —come from the root represented by the verb pret’ “to become wet from exposure to heat.” In etymology, a conclusion often depends on similarity, because semantic change is less regular than sound change and usually needs reinforcement.

This is also fog!

This is also fog!The fact that Russian par has two meanings resembling the two meanings of Engl. fog cannot prove that fog1 and fog2 are related, but it can support this idea or at least make it more plausible. And here is a minor point I would like to make about analogy. An English speaker who studies word origins and can read Russian (not a common occurrence) is unlikely to have encountered the second meaning of Russian par. By the same token, a Russian speaker and a student of etymology who can read English (a usual case) will probably never have encountered fog “grass,” so that neither scholar has the chance of noticing the similarity between those cases. (Let me cite a parallel. Engl. pimp is almost certainly related to German Pimpf “little boy; kid, etc.” But in the past, English etymologists were not aware of the rare German word, and Germans had no notion of English pimps (how could they?!) so that no one made the absolutely obvious connection. As a result, the origin of pimp is still supposed to be unknown.) It follows that in etymology a lot may depend on good luck. Some linguists—for example, Karl Brugmann and Antoine Meillet—mastered all languages, but we, the rank and file of philology, cannot compete with them. On this note of self-pity I’ll turn to the suggestions about the origins of the word fog.

German Pimpf denotes a boy before the age of puberty. Under the Nazis, the Pimpfe were the youngest subsection of the Hitlerjugend (Hitler Youth). Note that a helper in northern Idaho mines was also called a pimp!

German Pimpf denotes a boy before the age of puberty. Under the Nazis, the Pimpfe were the youngest subsection of the Hitlerjugend (Hitler Youth). Note that a helper in northern Idaho mines was also called a pimp!Some older English lexicographers already knew fog “grass,” though they were not sure what to do with the relation of fog1 to fog2. Fog reminded some people of Latin focus “hearth” (because both refer to warmth!), Latin fuligo “soot, mist, darkness” (cf. Engl. fuliginous “sooty”; the fuligo/fog tie looked especially attractive and stayed in Todd’s edition of Samuel Johnson’s and in many early editions of Webster’s dictionary), Old Engl. fæge “fated to die; (Scots) fey” (with reference to dead grass), and of several other nouns that need not be listed here. But quite early Danish fog “snowdrift” and Norwegian dialectal fogg “long, weak, scattered grass in a moist (!) hollow” were noticed and cited as clues to the English word. The English-Scandinavian parallel is so close that fog may well be a borrowing or a cognate of some Scandinavian word, though this derivation sheds no light on the origin of the Danish and Norwegian sources. As regards fog2 (“grass”), Skeat, for instance, did not even mention it in the first edition of his dictionary (1882), but later followed Murray’s OED and wrote that the history of fog should begin with the meaning “grass.” However, it is unclear whether there is a beginning here: fog1 and fog2 can be related but parallel formations going back to the same root meaning “a moist mass.”

Attempts to separate the two senses of Engl. fog are hardly persuasive, even if we disregard the Russian parallel. Not long ago, Richard Coates suggested tentatively that fog “grass” is a diminutive (he says: hypocoristic) form of fodder. It may be of some interest to quote a few definitions of fog from various dialectal descriptions: “second crop of grass in meadows”; “corn [= grain] which grows after autumn, and remains in pastures till winter”; “a portion of land or outfield glebe called the fogage, into which the minister’s cows were turned to pasture”; “grass not eaten down in summer, that grows in tufts over the winter”; “rank grass not eaten in summer”; “the word is used when farmers take the cattle out of their pasture in autumn: they say, ‘they are boun [= ready] to fog them”. In Westmoreland (North West England), feg means “dead grass.” According to one researcher (1883), “…fog is the rough coarse grass which is found in pastures; cattle will not eat this unless suffering from shortness of food.” Still more examples of fog will be found in Joseph Wright’s invaluable The English Dialect Dictionary. All those shades of meaning are of no importance for the present discussion, but the word is so little known to the general public that the short catalog presented above may intrigue our readers.

Scandinavian or native, what, we wonder, is the ultimate origin of fog? The word that suggests itself as helpful is German feucht “wet, humid.” Its partial lookalike is Old Icelandic fjúka “to be driven by the wind.” Many Germanic words begin with fu– and fū– and refer to blowing, imitating the “gesture” we make when we protrude our lips and blow off an object from the surface. Outside Germanic, such words (naturally) begin with pu– and pū– The rest is hard to reconstruct, but fog may belong with them. This hypothesis was offered more than a hundred years ago and made its way into a few dictionaries. Tracing fog and its alleged kin to the “gesture” is more convincing that deriving it from a root meaning “dirt, mud; swamp.”

The development of meaning may have been from “wind” to “a mass of air.” In rainy regions, a mass of air was probably often associated with wet air, so that an f-k word could acquire the meaning “dampness.” Old English was poor in such formations, while Scandinavian has very many of them. Fog “thick mist” turned up in English texts only in the seventeenth century. It is probably of dialectal origin and may have existed in regional speech for centuries. Once an association between fog ~ feg ~ fug and moisture became firm, the sound complex could be applied to anything that was wet, for instance, to the grass growing in a wet place. Later, as we have seen, the sense changed somewhat (from “wet grass” to “aftermath,” or eddish, as it is called in some parts of England). Be that as it may, fog is hardly “a word of unknown origin,” though, as always, everything depends on how we define unknown.

Images: (1) “Houses of Parliament in the Fog” by Claude Monet, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons (2) “Elymus junceus” by Matt Lavin, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr. (3) Pimpf, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons Featured image: Trees, fog by Unsplash, Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post “Fog” and a story of unexpected encounters appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers