Oxford University Press's Blog, page 438

November 22, 2016

Brexit, Marmite, and brand loyalty in the Roman World

One of the early and somewhat unexpected effects of Brexit in the UK was the threatened ‘Marmageddon’, the shortage and subsequent price rise of the much-loved – and much-hated – Marmite. Yet even when supermarket stocks of Marmite were running low, a variety of other yeast extract spreads were available. The shortage related to one particular brand. As I fall into the category of those who hate Marmite, I am not well placed to comment on the suitability of the substitute spreads, but clearly brand loyalty is strong among Marmite consumers. The development of such commodity branding and consumer loyalty is often seen as a relatively modern phenomenon, reflecting the rise of consumerism in Western Capitalist economies; the Museum of Brands in London, for example, only displays artefacts dating from the Victorian era onwards.

Brands were, however, also a part of much earlier economies. In ancient Rome, for instance, consumers placed their trust in a number of brand markers, which signified reputation and quality, and very often carried a certain prestige. This was particularly the case with food and drink, especially wine. A wide range of wine of all qualities was available in Rome, from that drunk in the taverns and street side bars, to the expensive vintages served at the most lavish of elite dinner parties. It was at this upper end that brands mattered most. The famous Falernian wine, for example, was prized by connoisseurs. This wine was produced from grapes grown in the ager Falernus in Northern Campania, and for Pliny, it was second only to Caecuban among Italian wines. By the mid first century CE, ‘Falernian’ was such a popular brand that it had become a byword for good wine. A graffito from the entrance to a Pompeian bar told customers ‘With a single coin you can drink here; if you pay two coins, you will drink better; if you pay four coins, you will drink Falernian wine’.

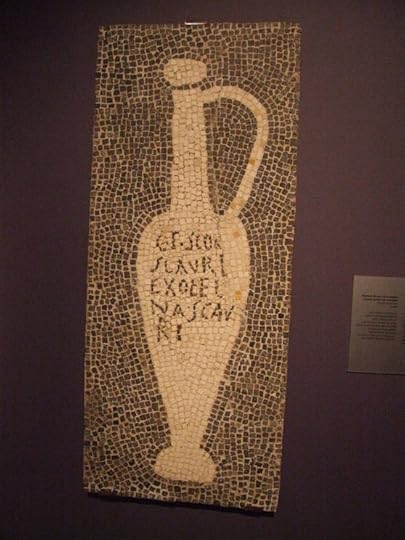

Garum Mosaik Pompeji, picture from the villa of Aulus Umbricius Scaurus, Pompeii by Claus Ableiter. CC BY-SA 3.0 by Wikimedia Commons. Detail of a floor mosaic from the atrium of VII.16.15 at Pompeii. The inscription reads G(ari) F(los) SCO(mbri) SCAURI EX OFFI(CI)NA SCAURI (Flower of garum of mackerel from the workshop of Scaurus).

Garum Mosaik Pompeji, picture from the villa of Aulus Umbricius Scaurus, Pompeii by Claus Ableiter. CC BY-SA 3.0 by Wikimedia Commons. Detail of a floor mosaic from the atrium of VII.16.15 at Pompeii. The inscription reads G(ari) F(los) SCO(mbri) SCAURI EX OFFI(CI)NA SCAURI (Flower of garum of mackerel from the workshop of Scaurus).Most Roman wines were best served young, but Falernian was unusual in that it improved with age. Trimalchio, the boorish fictional freedman of Petronius’ novel Satyricon, claimed to be serving aged Falernian wine to his guests, bottled in the consulship of Opimius in 121 BCE, a year that was renowned for its excellent vintages. Yet although small amounts of this vintage survived to the mid- first century CE, when both Pliny and Petronius were writing, it was so old that it had the consistency of honey and a rough flavour (only really suitable for adding to young wine for flavouring). Older was not necessarily better, and Falernian was best drunk after being left to mature for just fifteen to twenty years, not for nearly two hundred years! Trimalchio’s wine may have been rare, and for that reason, an impressive novelty, but if it were genuine, it would have been undrinkable.

It was, however, almost certainly fake; Trimalchio was either deliberately trying to deceive his guests, or he himself had been cheated by a crafty salesman. In fact, the Roman physician Galen questioned quite how much Falernian wine was actually genuine. Corinthian bronze statues too – much sought after by collectors – were sometimes faked, and Pliny the Younger was at great pains to emphasise that a Corinthian bronze of an old man that he donated to the Temple of Jupiter was a genuine antique. The problem of fake brands appears to be age old.

Falernian wine was stored and transported in clay amphorae, often marked with the brand name and sometimes a variety of other details, such as the name of the producer, the date, the shipper, and the intended recipient. Examples of such labels have been found as far afield as Roman Britain, where the shoulder of an amphora was marked with red painted letters reading FAL LOLL, abbreviations indicating that the vessel once contained Falernian wine produced from the vineyard of one Lollius. Such painted markers were originally found on most amphorae, although the majority are no longer visible today. They enabled producers to brand their products quickly and effectively. Umbricius Scaurus, a producer of fish sauce at Pompeii, even made a permanent record of such branding in a mosaic on the floor of his home (see image). The name Umbricius Scaurus – or that of another member of the Scauri family – appears on numerous fish sauce containers found in Pompeii and Herculaneum, and must have been a trusted marker of quality. People in Roman Campania may have been as loyal to Umbricius Scaurus’ range of fish sauces as fans of yeast extract in the UK are to Marmite.

Featured image credit: “Trajan’s Market” by Zello. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Brexit, Marmite, and brand loyalty in the Roman World appeared first on OUPblog.

November 21, 2016

Voltaire’s love letters

François-Marie Arouet, better known as Voltaire, was born on 21 November 1694. Famed as a great Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher, Voltaire argued for freedom of religion, freedom of speech, and most controversially at the time, the separation of church and state. Whilst he is best known for his satirical novella Candide (1759) and the Dictionnaire Philosophique (1764) – both espousing his views on society, Christianity, and morality – Voltaire’s private life is not as widely acknowledged.

The great author and philosopher was no stranger to scandal (both in the political, and personal realms) and was imprisoned on multiple occasions. Voltaire had numerous passionate affairs, most notably with Catherine Olympe Du Noyer (a French Protestant refugee known as ‘Pimpette’), Émilie du Châtelet (a married mother of three who was twelve years his junior), and Marie Louise Mignot (Voltaire’s niece). He engaged in an enormous amount of private correspondence with his lovers, much of which has been kept for posterity. Providing a fascinating insight into Voltaire’s inner-most emotions, his letters give a glimpse of his friendships, sorrows, joys and passionate desires…

In 1713, Voltaire’s father obtained a prestigious job for his son, as the secretary to the new French ambassador in the Netherlands. Whilst living in The Hague however, Voltaire fell in love with ‘Pimpette’ (a French Protestant refugee) – an outrageous union for the time. Their affair was discovered by the ambassador, and Voltaire was forced to return to France before the year was up. On 28th November 1713, he wrote the following desperate plea:

I am a prisoner here in the name of the King, but they can only take away my life and not my love for you. Yes, my adorable mistress, I will see you this evening even if it means losing my head on the scaffold. […]No, nothing can part me from you. Our love is based on virtue, it will last as long as our lives. Order the bootmaker to fetch a carriage—but no, I don’t want you to trust him. Be ready at four o’clock, I will wait for you near your street. Good-bye, there is nothing I would not risk for you, you deserve much more. Good-bye, my dear heart.

Image Credit: ‘Old Letters’ by Jarmoluk, CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

Image Credit: ‘Old Letters’ by Jarmoluk, CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.Despite the odds, the relationship continued for the next couple of years, with Voltaire still professing his love in February of 1715:

My dear Pimpette: Every post you miss writing to me makes me imagine that you have not received my letters, for I cannot believe that absence can have an effect on you which it never can have on me, and as I shall certainly love you for ever, I try to convince myself that you still love me.

In 1726 Voltaire was exiled to England, after an argument with a fellow nobleman who taunted the young writer on his nom de plume. Living in England, he was inspired by the contrast between Britain’s constitutional monarchy and French absolutism. After two and a half years in exile Voltaire returned to France, and in 1733 published a selection of essays on the superiority of the British political system. On translation into French they caused a massive scandal, and to avoid arrest Voltaire took refuge with Émilie du Châtelet, at her husband’s château. This was the start of an affair which lasted the next sixteen years. On their living situation, he jestingly noted:

She puts windows where I have put doors: she alters staircases into fireplaces, and fireplaces into staircases: she has limes planted where I had settled on elms: she has changed what I had made a vegetable plot into a flower garden. Indoors, she has done the work of a good fairy. Rags are bewitched into tapestry: she has found out the secret of furnishing Cirey out of nothing.

Émilie du Châtelet died after a complicated childbirth, in September of 1749, leaving Voltaire heartbroken. A philosopher, scientist and author in her own right, he wrote of her legacy:

A woman who translated Virgil, who translated and simplified Newton, and yet was perfectly unassuming in conversation and manner: a woman who never spoke ill of anyone and never uttered a lie: a constant and fearless friend — in a word, a great man, whom other women only thought of in connection with diamonds and dancing: for such a woman as this you cannot prevent my grieving all my life.

Image Credit: ‘Stack Letters’ by Andrys, CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

Image Credit: ‘Stack Letters’ by Andrys, CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.In spite of his attachment to the Marquise of Châtelet, in 1744 Voltaire had formed a new romantic relationship — with his niece, Marie Louise Mignot. There is much debate as to the nature of their association, and in a letter from 1747/8 he wrote:

How is my beloved? I have not yet seen her; but I am afire to see her every day, every hour.

Voltaire left behind a wealth of correspondence with Mignot, even sharing his intense grief at Châtelet’s death:

My dear, I have just lost one who was my friend for twenty years. You know that for a long time Madame Du Châtelet had no longer been a woman to me, and I am confident that you share my cruel sorrow. To have seen her die, and in such circumstances! And for such a reason! It is frightful.

Later in life, it is thought that Voltaire and Mignot co-habited platonically – and remained together until Voltaire’s death in 1778. Two weeks before his death, he wrote to the Baroness d’Argental poetically concluding:

I am ill, I suffer from head to toe. Only my heart is sound, and that is good for nothing.

A source of un-ending interest, Voltaire’s correspondence covers everything from personal and political events, to philosophy, science, and deepest sentiment. Offering a window into his and his companions’ milieu, they remain incredibly pertinent and moving over three centuries later. Born on this day in 1694 — a Happy Birthday to Voltaire, a man of love and letters!

Featured Image Credit: ‘Vintage, Parchment, Paper’ by ArtsyBee, CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Voltaire’s love letters appeared first on OUPblog.

A literary Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving has many historical roots in American culture. While it is typically a day spent surrounded by family and showing appreciation for what we are thankful for, we would all be lying if we did not admit that our favorite part is consuming an abundance of delicious food until we slip into a food coma. This Thanksgiving, celebrate the tastes of books by incorporating dishes from your favorite Oxford World’s Classic novels. This slideshow provides a complete literary-based Thanksgiving dinner menu for those that are looking for a bit of a twist on the traditional Thanksgiving meals.

Cheese ( The Belly of Paris by Émile Zola)

As an hors d’oeuvre, start with an elaborate cheese platter. Transport your guests’ olfactory senses to Madame Lecoeur’s cheese shop by incorporating a variety of types, such as those that Zola mentions in his “Cheese Symphony” – just maybe not until the point of nausea.

“All around them the cheeses were stinking…for the most part the cheeses stood in piles on the table. There, next to the one-pound packs of butter, a gigantic cantal was spread on leaves of white beet, as though split by blows from an axe; then came a golden Cheshire cheese, a gruyère like a wheel fallen from some barbarian chariot, some Dutch cheeses suggesting decapitated heads smeared in dried blood and as hard as skulls – which has earned them the name of ‘death’s heads’. A parmesan added its aromatic tang to the thick, dull smell of the others…Then came the strong-smelling cheeses: the mont-d’ors, pale yellow, with a mild sugary smell; the troyes, very thick and bruised at the edges, much stronger, smelling like a damp cellar; the camemberts, suggesting high game; the neufchâtels, the limbourgs, the marolles, the pont-l’évèques, each adding its own shrill note in a phrase that was harsh to the point of nausea…”

Cheese Platter by Linnaea Mallette, Public Domain via PublicDomainPictures.net

Clam Chowder ( Moby Dick by Herman Melville)

For your next course, throw your guests for a loop by deviating from the more traditional Thanksgiving dishes and serve them warm cups of clam chowder. Melville’s mouth-watering description proves that it’s sure to be a crowd pleaser.

“But when that smoking chowder came in, the mystery was delightfully explained. Oh! sweet friends, hearken to me. It was made of small juicy clams, scarcely bigger than hazel nuts, mixed with pounded ship biscuits and salted pork cut up into little flakes; the whole enriched with butter, and plentifully seasoned with pepper and salt….the chowder being surpassingly excellent, we dispatched it with great expedition.”

Clam chowder in a sourdough bread bowl by Marit & Toomas Hinnosaar, Public Domain via Flickr

Roasted Potatoes and Eggs ( The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett)

Treat your guests like royalty by whipping up an extremely simple, yet delicious side dish of roasted potatoes and eggs. According to Mary Lennox, feel free to eat at least 14 servings!

“Roasted eggs were a previously luxury and very hot potatoes with salt and fresh butter in them were fit for a woodland king—besides being deliciously satisfying. You could buy both potatoes and eggs and eat as many as you liked without feeling as if you were taking food out of the mouths of fourteen people.”

Roast potatoes with tomatoes on a decorative table by U.S. Department of Agriculture, Public Domain via Flickr

Turkey ( A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens)

It wouldn’t be Thanksgiving without turkey. For your main course, be sure to beat Scrooge to the butcher shop in order to purchase the largest prize turkey that they have!

“‘Do you know whether they’ve sold the prize Turkey that was hanging up there – Not the little prize Turkey: the big one?’

“What, the one as big as me?” returned the boy.

“What a delightful boy!” said Scrooge. “It’s a pleasure to talk to him. Yes, my buck.”

“It’s hanging there now,” replied the boy.

“Is it?” said Scrooge. “Go and buy it.””

Turkey Food Holiday by Isfara, Public Domain via Pixabay

Seed Cake ( Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë)

Finish off your feast with a warm cup of tea and a slice of seed cake. Even if everyone is stuffed to the brim, be sure to cut generous slices for your guests just as Miss Temple would do.

“Having invited Helen and me to approach the table, and placed before each of us a cup of tea with one delicious but thin morsel of toast, she got up, unlocked a drawer, and taking from it a parcel wrapped in paper, disclosed presently to our eyes a good-sized

seed-cake. “I meant to give each of you some of this to take with you,” said she; “but as there is so little toast you must have it now,” and she proceeded to cut slices with a generous hand.”

Poppy Cake by Einladung_zum_Essen, Public Domain via Pixabay

Featured Image: Thanksgiving by Wokandapix, Public Domain via Pixabay

The post A literary Thanksgiving appeared first on OUPblog.

Unidentified Aerial Phenomena and new research: Q & A with Diana Walsh Pasulka and Jacques Vallee

Unidentified aerial phenomena, commonly referred to as UFOs, has been the focus of research by sociologists, scholars of religion, anthropologists, philosophers, and astronomers. The information age now offers new and innovative ways to study the phenomena, and author Diana Walsh Pasulka sat down with astronomer and computer scientist Jacques Vallee to discuss how “big data” and information processing will influence the field of study.

Diana:

In a recent presentation you delivered in California in 2016, you described methods that you used to identify historical cases of sightings of anomalous aerial phenomena. Your methods were similar to those used by scholars of religion in that you locate primary sources and elaborate their historical contexts. You also utilized new research methods involving technology. You have been at the forefront of computer innovation since the 1960s, so I am intrigued on how you integrate historical research with digital technology. Can you discuss your methods and how they obtained the results that were eventually included in your book?

Jacques:

The study we just concluded is the product of a group of specialists (scholars, historians, researchers of ufology, archivists) linked through the Internet in an exchange managed by my colleague Chris Aubeck. The work builds on the intersection of classical scholarship and modern computer media to assess historical cases of extraordinary phenomena. In that sense the process is very similar to research in the history of religions, with the added benefit that the emerging patterns of ancient UFO sightings can be compared to modern reports.

This is very much a work in progress: future versions may focus on a nucleus of only 100 cases rather than 400 or 500; or they may expand to over 1,000 if we can get better access to data from Middle-eastern or Asian records.

Diana:

You issued a warning to new researchers in the field, particularly those who believe that “big data” and data mining techniques will shed light on the field and offer new insights? Can you elaborate?

My new keyboard by hardwarehank. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

My new keyboard by hardwarehank. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.Jacques:

For those who have just discovered the world of “big data” because of the exploits of super-computers winning at chess or GO against the best human champions, the technology seems almost magical: dump unstructured threads of information into a large binary warehouse and let “deep thinking” extract the salient patterns. This technology actually works when the data itself is well-behaved, in particular for consumer trends, industrial maintenance or medical research. When the subject area lacks an ontology, as in the case of unexplained aerial phenomena, the same techniques are problematic because the software is most likely to extract spurious or misleading patterns. Much of my career has been spent developing metadata software and (more recently) investing in Big Data companies, so I am a believer in the relevant techniques but one cannot skip the arduous work of preliminary data “scrubbing.” In particular, we have to keep in mind that the observed data may be the result of multiple phenomena rather than a single source. The problem is one of discernment and intelligence rather than brute-force statistics.

Diana:

Do you have advice for researchers today? How can we use new digital strategies to streamline our research?

Jacques:

The rapid expansion of computer records, as more and more old newspapers and books are digitized, has greatly facilitated access to original records. At the same time researchers are developing ingenious techniques for extracting information across long periods when the meaning of many terms has changed (think of the word “meteor,” which refers to the sighting of a falling aerolithe today but used to mean any luminous phenomenon in the sky). It has become feasible to conduct large-scale research on thousands of records at very minimum cost, without travel or administrative burden.

The problem remains of abstracting the data and making it available to others for critique, review and further research. A meeting was organized in 2015 at the Paris headquarters of the French Space Agency, gathering researchers from six nations in an effort to further collaboration in the exchange of data on unexplained aerial phenomena, but that work is just beginning. The phenomenon is global and very complex. Only 5-10% of the observations have actual research value. As a result, individual (occasionally heroic) attempts to hoard large quantities of information in hopes of “solving” the problem have proved naive, overly costly, and short-lived. It seems to me an open-source strategy will be the best way to motivate the research community and harness its resources.

Diana:

This seems like a crucial moment in the study of this phenomena in that we have access to digital technologies that help us identify patterns, but we cannot ignore the actual field research and historical methods that help us, first, identify something truly unexplainable, and second, draw correlations to other phenomena, or mostly importantly, rule these correlations out. This is arduous work but it results in knowledge.

Headline image credit: UFO by Vladimir Pustovit. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Unidentified Aerial Phenomena and new research: Q & A with Diana Walsh Pasulka and Jacques Vallee appeared first on OUPblog.

Adulting comes of age

The child in me was excited to see ‘adulting‘ as one of the shortlisted words for the Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year 2016. Adulting is on the minds–and tongues–of many of my millennial-generation college students.

They explain that it is about assuming adult responsibilities like managing money, showing up at a job, buying food and paying rent, getting health care, and more. Adulting can even be about mundane things events like staying in on the weekend, doing the laundry, filling the car with gas, or charging their phones.

Adulting is different than just “growing up” or even “acting your age.” You can tell an unruly seven-year-old to “grow up” or “act your age” but not to adult. The expression is especially useful because it captures a concept of our time: becoming a new adult in a world with more responsibilities, more and less clear economic opportunity than the last generation enjoyed. The experience of millennials is different from that of their parents, so it’s a concept in need of a word.

And adulting represents long-standing linguistic trend of making verbs and then gerunds out of well-worn nouns. When I first learned about adulting, I asked my students what other nouns they used as verbs. Of course, they text, they friend and unfriend, and they club. Several students volunteered that they library. One athlete said that she gyms. And two students reported that they money. When I asked for examples of the last usage, the students suggested things like “I need to get my car fixed as soon as I can money it” and “I had to money my tuition, so things are going to be tight this month.”

I like these shifts and now I occasionally library, gym, and money things myself. When I use these neologisms, I get some funny looks implying that I need some adulting, but for now I’m just going to oblivious them.

Featured image credit: “Doing laundry”. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

You can learn more about the Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year 2016.

The post Adulting comes of age appeared first on OUPblog.

November 20, 2016

The politics of caring: what this election can teach us

We awoke the morning after the presidential election to a festering wound made raw by the long campaign and, for some, split open by the results of the election. It is a wound of fear — not just any fear, but fear of people on the other side of the political divide.

Some supporters of Mrs. Clinton, for example, fear Republicans putting in a conservative Supreme Court justice. They fear this will tip the balance of the Court in favor of restricting a woman’s right to choose.

Meanwhile, some supporters of President-elect Trump have feared the policies of Democrats. Along with the loss of their jobs, coal miners, for example, fear losing their centuries-old way of life—the Appalachian hamlets in which they live and sing the hymns of their ancestors who are buried on the hills. “Will the circle be unbroken?” they ask in one of these hymns—unbroken in heaven, but broken here on earth through their government’s inattention to their economic realities.

Government can work to improve the economy, and it can ensure rights. But government cannot be the salve for the wound of fear. The only salve for that wound is caring for those on the other side.

To apply this salve, we must imagine the source of the wound for each other. We do not have to agree on the complex reasons for the changing energy economy to imagine coal-mining communities’ fear of losing deeply cherished ways of life. Nor do we have to agree on the interpretation of the Constitution to imagine the fear of having women’s rights undone.

Election by tstrong20. CC0 Public Domain Via Pixabay.

Election by tstrong20. CC0 Public Domain Via Pixabay.But this imagination is not merely for the sake of understanding. It is so we can act. Caring requires that we work with others unlike us to preserve that which they fear losing. One of this election’s great lessons for our politicians is that they should care enough about those on the other side to work with each other to ensure that that which we care about is preserved and protected. After all, isn’t our government to be concerned about the welfare of all? Should it not protect our individual rights? Government can only do this when those governing care about all of us.

Some voters voted out of fear of people unlike them, people with different countries of origin, people who speak different languages, and who worship different gods. Some voters voted out of fear of people who come here seeking a better life—undocumented people who try to improve their circumstances through the back-breaking work of picking produce as day laborers, their working conditions and their pay uncertain. Some voters voted out of distaste for the voters who fear people unlike them, unable to understand their fear’s source: their own poor pay and working conditions—or no work at all. Yet when we care for voters unlike us, we also help them to see that this country holds a special place for immigrants who come to escape war and violence, poverty and hunger, and who come to give their children a good education and a chance in life. When we care for voters unlike us, we help them to see that this country has a large enough heart, plenty of land, and an economy that can help them and immigrants. After all, our incoming first lady came as one herself. When we care for voters unlike us and help them improve their circumstances, we help them overcome their fear of others.

Maybe the greatest lesson from this election for all of us has to do with the kind of society we want. We have to care about the freedoms ensconced in the First Amendment—freedom of assembly, freedom of the press, and freedom of religion. And we have to care about justice applied fairly to all, including caring about the fundamental principle of the presumption of innocence until proven guilty. For when we do not care about a free and fair society, we cannot freely and fairly care for others. Yet when we freely and fairly care for others unlike us, we come together as one nation.

Caring for others is a powerful mendicant, which we all must now apply across the divide if we are going to heal the wound of fear.

Featured image credit: 2020 Senate Election Map by Orser67. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The politics of caring: what this election can teach us appeared first on OUPblog.

An alternative to the Electoral College

Over the last few days, as anyone interested in the American presidential election can tell you – and it seems everyone is –, the 2016 election is one of the few in history with two different winners: one candidate appears to have won the popular vote and the other has won the Electoral College vote. As of this writing, according to the latest tally the popular vote leader is Hillary Clinton by over 337,000 votes. This fact is politically (and perhaps sociologically) important. But it is irrelevant under our constitutional system.

Under the Constitution, the President is the only federal office subject to a special electoral process. There are two steps: first, individual voters register their preferences in the voting booth. The second step, which usually receives far less notoriety, consists of electors from each state designated according to the winner of the statewide popular vote. (Maine and Nebraska are exceptions, as their electoral votes are assigned by the popular vote winner in each congressional district.)

Also in the last few days, there has been reinvigorated discussion of the possibilities of reforming how the Electoral College works, and even whether it should be abolished. This recrudescence of reform of the Electoral College has assumed that there are two paths to reform: a constitutional amendment, or a previously little-known proposal called the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPV). A constitutional amendment would be very difficult to achieve. Of the thousands of constitutional amendments proposed since the beginning of the Republic, only 27 have been ratified. Even if the proponents of an amendment strike while the iron is hot, there is no likelihood a Republican-controlled Congress would vote for altering the Electoral College. That political reality leaves the National Popular Vote proposal as the only apparent reform option.

Under the NPV compact states would agree to award their electoral votes to the winner of the national popular vote, rather than awarding electoral votes to the popular vote winner in their state. Under such a system, Republican Wyoming would award its electoral votes to a Democratic candidate who won the popular vote on a national scale. So, too, would reliably Democratic New York award its electoral votes to a Republican national popular vote winner. The NPV compact goes into effect when a number of states equal to the 270 electoral votes needed to win the presidency have enacted it. To date, ten states and the District of Columbia have enacted the plan, totaling 165 electoral votes. That means NPV proponents are just over halfway home to putting the compact into effect. Proponents claim the NPV will reflect the democratic preferences of the voters much better than the allegedly antiquated Electoral College.

NPV compact proponents contend the Electoral College can be altered through the constitutional process for interstate agreements, without resort to a constitutional amendment. Other commentators have noted the political problems – How to handle recounts? More plurality winners? Regional candidates? – that might ensue from a popular vote system. I’ll restrict my comments to the legality of the NPV. In short, the NPV proposal is manifestly unconstitutional. Here’s why.

Proponents claim the NPV will reflect the democratic preferences of the voters much better than the allegedly antiquated Electoral College.

The Constitution’s Compact Claus provides: “No state shall, without the Consent of Congress … enter into any Agreement or Compact with another state.” Some prior interstate compacts have been challenged in the federal courts, and the Supreme Court has held that not all interstate agreements need congressional approval. For example, a compact resolving a state boundary or creating a multistate tax commission does not need Congress’s approval. NPV supporters claim congressional approval is unnecessary.

However, the Court has only allowed compacts that do not penalize non-joining states and do not threaten federal interests or institutions. The NPV compact would fail on both counts. First, the NPV would disadvantage states that refuse to join the compact. For example, low-population states would likely refuse to join because they would be disadvantaged relative to high-population states. Second, and most importantly in terms of constitutional legitimacy, the express purpose of the NPV compact is to change a federal constitutional institution, the Electoral College. That is, the NPV is trying to reform a constitutional institution – the Electoral College – without going through the amendment process. This fact requires the NPV to be submitted to Congress for approval, per the Compact Clause.

But that’s not the only roadblock for the NPV.

Even if Congress wanted to approve the NPV, it would be unconstitutional to do so. The Supreme Court has held that Congress’s approval of an interstate compact converts the agreement into federal law. Although the Constitution leaves the appointment of electors up to the states – a point NPV proponents repeatedly make – the submission of the NPV compact to Congress puts Congress in the position of approving a measure that Congress would be prohibited from enacting by itself. The Constitution does not allow Congress to create a popular vote system on its own initiative. Therefore, how could Congress approve a state-based plan that does the same? In short, the NPV compact is unconstitutional because the Constitution does not allow a minority of states, in combination with Congress, to amend the Constitution.

Headline image credit: American flag by tpsdave. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post An alternative to the Electoral College appeared first on OUPblog.

War stories of WWII

Historian Daniel Todman coalesces various aspects of military history and the personal narratives from those who were in battle. Linking the strategic, political, and cultural sides of war, Todman aims to capture the true consequences of WWII. The excerpt below, from Britain’s War: Into Battle, 1937-1941, illustrates the fluidity of history by telling the stories of the author’s two grandfathers, both veterans with their own respective views on the war. As he reflects on their experiences, Todman highlights how questioning and analyzing personal stories can find new meaning in history:

Tucked at the back of my desk drawer, in an old hearing-aid box, are the medals that could have belonged to my grandfather. The War and Defence Medals and the 1939–45 and France and Germany Stars were the sort awarded for service, rather than valour – and they match the three years that Charles Todman spent driving tanks and trucks in the UK before, transferred to a machine-gun battalion, he was sent out to North-west Europe at the start of September 1944. Their metal shines and their ribbons are unfaded. These are medals that have never been worn.

For most of the time that I knew him, Grandad showed no sign of thinking of himself as a veteran. He never went to the Royal British Legion, or belonged to a regimental association, or went to ceremonies on Remembrance Sunday. As a child, I was not regaled with his war stories. Only with reluctance could he be persuaded to name the guns wielded by my Airfix plastic soldiers, and when the film A Bridge Too Far made one of its frequent appearances on television, my grandmother, Nanny, told me to turn it off because it was too noisy. The medals he had actually received for his wartime service had been lost: given to his sons to play with, they had disappeared into the cracks that had opened up in the sun-baked garden of their Metroland house one summer in the 1950s. That seemed to sum up how he had decided to treat the war. Judging by the pictures they kept on their walls, he and Nanny were much keener on celebrating their post-retirement holidays, their grandsons, and the awards given to their home-made wine than on marking their participation in the Second World War.

The 1977 British-American war film A Bridge Too Far follows British Lieutenant-General Frederick Browning [above] during Operation Market Garden. Though unconfirmed, Browning is credited as saying, “I think we may be going a bridge too far” during the operation. Image credit: “Browning observes paratroop training at Netheravon” by War Office official photographer. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The 1977 British-American war film A Bridge Too Far follows British Lieutenant-General Frederick Browning [above] during Operation Market Garden. Though unconfirmed, Browning is credited as saying, “I think we may be going a bridge too far” during the operation. Image credit: “Browning observes paratroop training at Netheravon” by War Office official photographer. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. Yet the war had been the defining moment of their lives. How else would a trainee accountant from London and a miner’s daughter from Tyneside ever have met, if military service hadn’t brought them both to a dance in the sergeants’ mess at the army camp at Barnard Castle? They first met when he picked her up after she fell on the floor, but in their wedding photos, Grandad in his uniform looks like the one who might be about to topple over. Her father had drunk him and his mates under the table the night before. Husband and wife obviously made good use of the last moments before he was sent to Europe, because their first child, my father, was born exactly nine months after his embarkation leave, at the start of May 1945. The Russians were in Berlin, the war in Europe was in its final days, and the midwife insisted that the boy would have to be called Victor to mark the occasion, thus ensuring that he would spend the rest of his life as a war memorial.

His parents never used that name in my hearing: they always called him Bill, his second name, instead. This was probably not just a matter of preference. Years later, Grandad was still angry that, although the fighting had finished, he had not been allowed home to see his new son. Instead, he was stuck in a recently surrendered Hamburg with his unit, waiting for further service in the Far East. The end of the war with Japan saved him from that, but he didn’t get a leave long enough to come home again until the end of October 1945. Unlike a lot of families, they didn’t have to deal with bereavement or disability, but the anxiety and the pain of separation – during the pregnancy, then during the first year of my father’s life, because Grandad wasn’t demobbed until May 1946 – must have been terrible. When he returned home, they put the war behind them and got on with their lives.

Yet they were also interested in, and proud of, their grandsons. After my first book was published, Grandad decided that it might be nice if I could have his medals. When the Ministry of Defence explained that they didn’t issue replacements, he bought new ones from a dealer to pass on to me. In a letter, he recalled some of what he had experienced during that final, bitter campaign, including the terrifying day that rocket-firing Hawker Typhoons mistook the target marking and attacked his unit rather than the Germans. My brother and I bought him a copy of the regimental history for his birthday, and he read it with apparent interest. After all these years, he said, it was good to know what had actually been going on.

The France and Germany Star created and awarded by the British Government for operational service on land in France, Belgium, Holland or Germany after the D-Day landings on 6 June 1944 until 8 May 1945. Image credit: Col André Kritzinger. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The France and Germany Star created and awarded by the British Government for operational service on land in France, Belgium, Holland or Germany after the D-Day landings on 6 June 1944 until 8 May 1945. Image credit: Col André Kritzinger. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.In contrast to Grandad Todman, as I was growing up my maternal grandfather, Frederick Spackman, seemed to talk about the war every time we saw him. Fred had been a fitter with the London Transport Passenger Board and, having joined the Territorial Army in 1938, he spent the war repairing vehicles in workshops in Britain and Egypt. It was without doubt the most exotic thing that ever happened to him. The studio portraits taken by a wartime photographer in Cairo show Fred doing his best to look like Errol Flynn, but there wasn’t much swashbuckling in his stories. They were always the same. The motorbike accident that had put him in hospital, as one of the war’s first British casualties, on 3 September 1939. The time he knew more than the officer who had to test his mechanical knowledge. Keeping a chameleon, learning to repair watches and counting to ten in Arabic. The working of the Wilson epicyclic gearbox in the Daimler Armoured Car.

These tales were so familiar that we could repeat them word for word and, to us if not to him, they became something of a joke. Only at the end of his life did it become apparent that he could have told a different set of stories. The hasty first marriage conducted in the shadow of impending war. The wife who then told him that she was carrying a child and that she was not sure if he was the father. The belated divorce. All this had been written out of the family’s history: the strength of the taboo such that my mother, his daughter by his second marriage, had known nothing about it at all. While Fred was abroad, his estranged wife continued to draw an allowance from his pay, his father died and all his possessions were sold. On demobilization, he had to rebuild his life completely from scratch. Like most men of his generation, he did not enjoy unrestrained displays of emotion. Perhaps it was not surprising that he liked to keep his memories of the war closely controlled.

I tell these anecdotes not just as a means of paying tribute or claiming inherited authority, but also to make a point about the complexity and fluidity of our relationship with the past. What we put in and leave out of our history matters, but what we think we know can always be subject to change. Eighty years on from 1939, with the war disappearing over the boundary of lived memory, we can still question and rework the stories we tell about it, finding new meanings and turning the familiar strange.

Featured image credit: Pilots of ‘B’ Flight, No. 33 Squadron RAF” by Royal Air Force official photographer. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post War stories of WWII appeared first on OUPblog.

Behind the scenes: Installing John Singer Sargeant’s ‘Gassed’ at PAFA [slideshow]

Running from November 2016–April 2017, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts hosts the exhibition World War I and American Art. With over 150 works by American artists, this carefully curated exhibit is the first major exhibit to explore how American artists reacted to World War I. At the center is John Singer Sargent’s sizable and impressive masterpiece, Gassed (1919). David M. Lubin, co-curator of the exhibit, depicts the painting in his recent book, Grand Illusions:

Set against a blank sky tinged with pale lavender, cream, and mustard

tones suggestive of the invisible gas that poisoned them, ten sightless soldiers,

their eyes bandaged, stumble in a row down a duckboard lane, each

steadying himself on the shoulder of the man in front of him—although one

of them momentarily lurches out of line, presumably to vomit from gas-induced

sickness. Ironically, several of them carry a rifle—a firearm with a

built-in sight, that is, a mechanism for guiding the eye. That they do so only

heightens the painting’s aura of futility. An orderly guides them on their

way. Approaching a rise in the duckboard, one of the wounded raises his leg

in an exaggerated way, as if the orderly has cautioned him to mind his step.

In the background, only to be glimpsed through the legs of the blindfolded

marchers, healthy soldiers scrimmage in a casual game of football, with one

of the players extending his knee in a kick that parallels the exaggerated step

of the blind man in line.

Browse our slideshow to view the installation of this celebrated painting.

Installation photographs generously provided by the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.

Featured image: Gassed by John Singer Sargent. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Behind the scenes: Installing John Singer Sargeant’s ‘Gassed’ at PAFA [slideshow] appeared first on OUPblog.

November 19, 2016

Hillary Clinton and the “women’s vote”

One hundred years ago, in 1916, Montana elected the first woman to serve in Congress: Jeannette Rankin. On Tuesday 8 November, the US did not elect its first woman president. Although Hillary Clinton won the popular vote, Donald Trump won the Electoral College.

The expectation of a Clinton victory led many to reflect on the long history of the women’s quest for the right to vote. In Rochester, New York, visitors to Susan B. Anthony’s grave covered her modest headstone with “I Voted” stickers. Media commentators ticked off the ninety-six years that had elapsed between the 19th Amendment’s ratification and the arrival of a woman at the head of a major party ticket. And three researchers put together a widely circulated web site “I Waited 96 Years!” with stories and photographs of women “born before the 19th Amendment,” who planned to vote for Hillary Clinton.

Embedded in these developments are three narratives. One, the story of the long struggle to secure voting rights, underscores Anthony’s heroism in going to the polls in 1872 and being arrested for illegal voting. Another, the story of a singular, hard-won achievement, misleadingly insists that “American women lacked the right to vote until” 1920. A third, the story of eventual triumph, writes a neat concluding paragraph to the effort.

As with so many popular historical tales, the three narratives leave out a lot. When Susan B. Anthony voted in 1872, several other women joined her, all of whom hoped to prove that voting was a right of citizenship under the 14th Amendment. In scattered locations, hundreds of other women—both African American and white—did the same. Mary Ann Shadd Cary, a newspaper editor, teacher, and graduate of Howard University Law School, who argued that the 14th and 15th Amendments had conferred voting rights on African American women as well as men, led a group of more than sixty who attempted to vote in Washington, D.C. They were unsuccessful, but received affidavits certifying that they had made the effort. And it was not Anthony but Missouri’s Virginia Minor whose name eventually appeared on the 1875 Supreme Court decision on the legality of women’s voting, Minor v. Happersett. In case you’re wondering, she lost. Women were clearly citizens, the Court held unanimously, but it was up to the states to decide which citizens could vote.

States and territories had already begun making those decisions. In 1869, Wyoming Territory granted women full voting rights. When Wyoming entered the union in 1890, women kept those rights. Women in Montana gained full suffrage in 1914, the year of Montana statehood. By 1916, when Jeannette Rankin won her seat in Congress, women had full voting rights in 12 states and territories; by 1918, the number was 16. By the summer of 1920, as suffragists were making the final push to get states to ratify the 19th Amendment, women had won the right to vote in presidential elections in more than half of the 48 states.

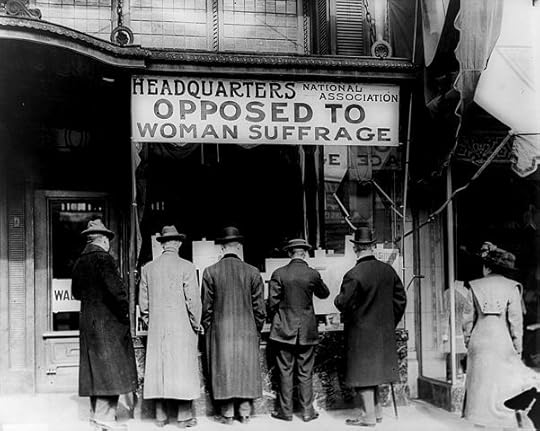

Image credit: National Association Against Woman Suffage by Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: National Association Against Woman Suffage by Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.These victories are not simply historical footnotes. Both full and partial woman suffrage became key elements in the suffragists’ strategy to secure a national amendment. If today’s voters are familiar with any part of the suffrage crusade, it’s likely to be the “Iron-Jawed Angels” of the National Woman’s Party. Founded in 1916, the group became famous for its militant tactics, including picketing the White House while burning Woodrow Wilson’s words about democracy. Those tactics, part of a strategy of “holding the party in power responsible” for women’s lack of voting rights, depended upon mobilizing women who had suffrage to work to extend that right to the rest. It also depended on the questionable assumption that all women shared common political interests.

With the 19th Amendment’s ratification, a chapter in a long struggle ended. But new chapters remained to be written. In principle, all women now had the right to vote. But some women, particularly in the states of the former Confederacy, as well as Asian-born and Native American women, remained disfranchised by laws that disfranchised men of their racial category or prevented them from becoming citizens. Still in 1920, in several former Confederate states, African American suffragists challenged voting registrars and successfully registered and voted—for a time. Their counterparts in the North, long active in the suffrage movement, found new political clout. In Illinois, for instance, led by the great anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells-Barnett, African American women voters mobilized to help elect Oscar De Priest to Chicago’s city council and later to the US House of Representatives.

After 1920, different women had different access to what was now considered a fundamental right of adult citizenship: voting. In other words, women’s suffrage suffered the same fate of differential entreé as did other women’s rights, such as the right to reproductive autonomy. Nor did all women agree on the value of voting. As 1920 ended, women antisuffragists were still challenging the 19th Amendment’s validity and vowing to defend “The Family and the State” against “Suffragism, Feminism, and Socialism.” By 1927, the group had accepted suffrage. There were women voters but clearly there was no united “women’s vote.”

There still isn’t. On 8 November, women as a group supported Hillary Clinton over Donald Trump, but 53% of white women voted for Trump. It was African American women, 94% of whom championed Clinton, and Latinas, 68% of whom voted for her, who most fervently wanted to see this particular woman in the White House. Some day, another woman will seek the presidency on a major party ticket. When she does, she shouldn’t expect a “women’s vote” to carry her to victory, any more than a “men’s vote” made Donald Trump into the president-elect.

Featured image credit: Hillary Clinton by Nathania Johnson. CC-BY- 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Hillary Clinton and the “women’s vote” appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers