Oxford University Press's Blog, page 437

November 24, 2016

The many ‘sides’ of Thanksgiving…and the English language

We may talk a lot of turkey during the holiday, but US Thanksgiving is really all about the sides. Yes, we pile our plates with mashed potatoes and green beans, but we also feast on the many other great sides the English language has to offer.

From all sides

During the holiday, both sides of a family may gather together out in a relative’s home in the countryside. The cook may serve up food on a sideboard, with the stuffing cooked on the inside of the bird.

At dinner, some may take sides of a political controversy, while others may just stay on the sidelines – of the American football game on TV, that is, where a ref may flag a player who is offside.

A distant aunt may pull an unsuspecting nephew aside for some colorful side comments. That’s better than her husband, who corners a cousin about the new siding on his house.

Besides the family drama, too much food will split sides, as will the convivial laughter. Celebrants can cap the meal with a postprandial snooze: How about sideways on the sofa right by the fireside? The drowsiness is surely just a side effect of all the turkey’s tryptophan – not the booze, of course!

Inside side

English really dishes up the sides. This may not be surprising, as the word has had a lot of time to develop in the language: the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) dates side back to Old English, when, much as now, it named the sides of the body.

Side has many cognates in the Germanic languages, but its ultimate origins are unclear. Proposing a Proto-Germanic root, philologist Walter Skeat has suggested an earlier, literal meaning of ‘that which is extended.’ This is possibly connected to another early side in Old English, this one meaning ‘long’ and ‘spacious.’

Let’s have a look at – er, taste of – some other particularly interesting side words in English.

Side notes

If we have a hard time paying attention, we might easily get sidetracked. This term is derived from the 19th-century side-tracks of railroads.

If we want to avoid a touchy topic, we might sidestep it in a conversation, a word first recorded in military marches near the backside, shall we say, of the 1700s. In such a conversation, we might digress with many sidebars, which US journalists were using by the late 1940s to refer to articles secondary to the feature story in a newspaper; the figurative sense was in place by the early 1950s.

A sideshow may have been – no hoax – a coinage of the great showman P.T. Barnum. He refers to it as a ‘temporary enterprise’ alongside his main attraction, as the OED first records the word in 1855.

A sidekick is also first found in American English. It’s back-formed from side-kicker, documented at least by the start of the 1900s for a ‘close but lesser pal.’ The kick may originally have meant “to walk or wander,” yielding to kick around or kick about.

Another stateside word is sideburns. This facial hair is named after Ambrose Burnside, an American Civil War general noted for the particular way he groomed his whiskers. Here, the OED quotes the Cincinnati Enquirer in 1875: “His whisker was of the Burnside type, consisting of mustache and ‘muttonchop,’ the chin being perfectly clean.”

Maybe you recall that records had A-sides and B-sides? Another term for the B-side was the flip side, dated to the late 1940s. The B-side typically featured the lesser track(s) of a recording, although on the flip side lives on as a positive consideration of some matter.

Like flip side, we can also speak of the upside or downside of some event. While upside and downside have long been in the language, these substantive usages for ‘advantage’ and ‘disadvantage,’ respectively, trace back to the early 20th century, when they were used to describe the movement of share prices in the stock market.

Upside down is far older, at least in sense. The OED dates it back to the 1300s, but the phrase took a different form early on: up so down. Speakers shaped the word into upset down and upside down, which stuck, since the usage of so was unusual, the OED explains.

Sidle, ‘to edge sideways,’ also features some curious linguistic changes at work. The verb is actually a back-formation of sideling, which was an adverb meaning ‘sideways’ but whose -ing sounds like the progressive tense or a present participle in English. In the word sideling, however, this -ing is actually part of -ling, an old adverbial suffix in the language. Not to be left out, -ling got confused with -long, another adverbial suffix seen in sidelong.

Sports fans, especially of American football, may well be familiar with blindsided. As the OED notes, the term, deriving from blind side, actually dates back to the very early 1600s, referring to the ‘weak side of a person or thing.’ Bedside manner may also strike some as a relatively new phenomenon, but it is in fact recorded by the mid-1800s.

Finally, two words that are surprisingly younger than many may suppose are insider and outsider. Insider is documented by 1848 (and in the context of the stock exchanges), which makes it roughly contemporary to sunny side.

In a recent observation made by lexicographer Peter Sokolowski, outsider, has been spiking in the American language due to the political outsider status some Republican Party presidential candidates are touting. Sokolowski also noted it appears in 1800 in a letter by Jane Austen (the OED attests this, too), referring to some outsiders to a card game.

But like gravy, many like to keep their politics on the side on Thanksgiving.

This article originally appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Featured Image Credit: “Thanksgiving Table” by vxla. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The many ‘sides’ of Thanksgiving…and the English language appeared first on OUPblog.

Donate smarter this Thanksgiving and holiday season

Despite the fact that we produce more than enough food to feed the world, food insecurity is a serious societal issue. Even in a nation as wealthy and rich in resources as the United States, food insecurity is troublingly common, impacting more than 1 in 5 children and nearly 15% of all households. Food insecurity, which can be defined as limited or uncertain access to nutritionally adequate and safe foods, is a major stressor on the family. Lack of income, reliable transportation, and distance from grocery stores offering low-cost healthy foods can make it extremely difficult for some families to obtain a minimally adequate diet.

Food insecurity can be expressed in the form of social, emotional, behavioral, and physical health problems. It also results in feelings of alienation, powerlessness, guilt, and shame. Children in food-insecure households demonstrate lower levels of academic achievement and more behavioral and mental health problems.

Food insecurity is “a societal failure to make adequate food meaningfully accessible to all.” Though government programs have made great strides to reduce chronic under-nutrition in America, the programs do not provide a complete safety net. Many Americans are struggling to have enough to eat. With cuts to food stamps and 40% of food in the US ending up in landfills, it is critical that we all do our part in advocating for more social policies that prevent conditions of food insecurity. Social and policy reform takes time, but there is one thing you can definitely do right now to bring about change:

Donate.

But don’t just donate, donate smarter.

You probably know about how important it is to donate food to your local soup kitchen during the holiday season (and the rest of the year, as well!), but do you ever give much thought to what you’re donating? Do you ever give food you wouldn’t necessarily want to feed to your kids in large quantities? Do you often find yourself shopping in the canned goods aisle of your grocery store, buying cheap canned raviolis and packaged sugary granola bars, or similar sorts of items?

Foods given to charitable organizations tend to be low-quality, processed, energy-dense, and high in unhealthy fats and sugars. Compromises in the quality of food often lead to greater energy consumption of food as people try to feel full while saving money. Children from insecure households are much more likely to be overweight. Though you may be giving these children and their parents calories, the recipients of this food could become malnourished from lack of essential nutrients over time. This unfortunately results in various health and obesity problems for millions.

In promoting food security for all Americans (and for the world, as well!), responses to food insecurity should prioritize healthy diet rather than just having “enough” to eat. The next time you’re planning to donate, think healthy, and spread this message to your friends!

Featured image credit: “Members of the United States Navy serving hungry Americans at a soup kitchen in Red Bank, N.J., during a community service project.” by United States Navy. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Donate smarter this Thanksgiving and holiday season appeared first on OUPblog.

November 23, 2016

(All) my eye and Betty Martin!

The strange exclamation in the title means “Fiddlesticks! Humbug! Nonsense!” Many people will recognize the phrase (for, among others, Dickens and Agatha Christie used it), but today hardly anyone requires Betty Martin’s help for giving vent to indignant amazement. However, the Internet is abuzz with questions about the origin of the idiom, guarded explanations, and readers’ comments. Therefore, considering that “The Oxford Etymologist” must keep abreast of the times, I decided to make public the information I have in my database, even though I, like most of my predecessors, am unable to offer any etymology of this puzzling ejaculation, as such phrases were called in the golden and innocent past.

In all my eye and Betty Martin, one segment causes no trouble. My eye, like my foot, is an expression of surprise, though my eye seems to be dated. All has no explanation, and the identity of Betty Martin remains a mystery. Two things should be taken into consideration before we embark on our fruitless but instructive journey.

First. Idioms teem with references to proper names. It’s all Cooper’s ducks with him means “It’s all over with this man.” In a year of Sundays, we would not be able to discover who Cooper was and what disaster befell his ducks, even though the Internet is aware of the idiom! The simile as busy (or thrang) as Throp’s (sic) wife is current in northern England. According to at least one legend, this lady “is known (!) to have hanged herself.” But, most likely, people invented the story in retrospect, as they often do, to explain the incomprehensible phrase, though Mr. Throp could of course exist and be married to an unhealthily active woman. The Internet did not miss him of course. However, the disturbing circumstance is that one can also be “as queer (= odd, strange) as Tim’s wife looked when she hanged herself” (an Irish idiom). Apparently, we have a substitution table, with the elements replacing one another, unless, of course, Throp’s first name was Tim and we are dealing with the same character. One can be lazy as Laurence’s (Ludlum’s, Lumley’s) dog, drunk as Davy’s cow (or Chloe), and as hot as Mary Palmer. In the middle of the nineteenth century, English schoolboys shouted on the arrival of the holiday: “Let’s sing Old Rose, and burn the bellows,” meaning “Let’s singe the master’s wig, and burn our books.” Those who have enough leisure on their hands may try to investigate the biography of old Rose. Mary Palmer looks like someone from history, but, though the origin of the simile has been more or less ascertained, the biography of the lady remains undiscovered. She may have been Betty Martin’s older married sister. Incidentally, at least one early novelist wrote: “That’s all my eye and Tommy” (possibly a facetious version of the better-known phrase, but perhaps a variant: consider the case of Tim’s hapless wife).

Second, countless sayings infiltrate language from popular culture, that is, from street songs, the music hall, scurrilous jokes repeated again and again, and evanescent urban legends. Traces left by such “texts” are hard and often impossible to recover. The Betty Martin exclamation surfaced in books in the late eighteenth century, and a record of her doings is lost, most probably forever. Some wit (wag) may have added the lady’s name to my eye, and the joke “found favor” with the public. Such is the history of a good deal of slang. All remains obscure, and it would be more profitable to dispense with it. Part of what I am about to say has been recycled many times, though the tales I singled out will be new to most. For some additional references see my Word Origins… (p. 265, note 2).

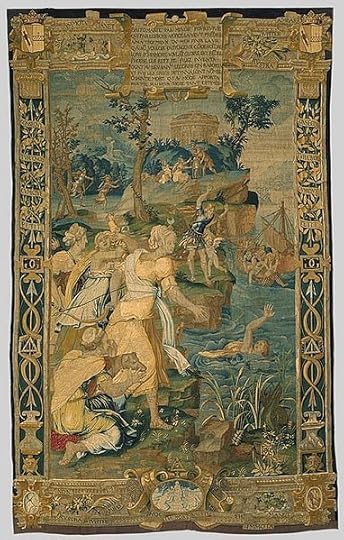

Britomartis was a Minoan (Greek) goddess, but Edmund Spenser (Faerie Queene), prey to folk etymology, connected the name with Britain and Mars. Is Britomartis our Betty’s alter ego?

Britomartis was a Minoan (Greek) goddess, but Edmund Spenser (Faerie Queene), prey to folk etymology, connected the name with Britain and Mars. Is Britomartis our Betty’s alter ego?The suspicion that my eye and Betty Martin is a facetious alteration of some Latin phrase is old: allegedly, we are dealing with a word group garbled beyond recognition. Most often St. Martin has been pressed into service, but the Minoan goddess Britomartis bore him company in the 1943 book The Heritage of Britain by J. H. Harvey. The explanation usually repeated in popular sources traces the phrase to the experience of a British sailor who, during the service, heard the Latin invocation containing the words O mihi Beate Martine and repeated them in the form we know today. Here is the original story, as quoted by E. Cobham Brewer in the first edition of his immensely popular and equally unreliable Dictionary of Phrase and Fable: “A Jack Tar went into a foreign church, where he heard someone muttering these words ‘Ah mihi beate Martini’ (Ah! Grant me, blessed Martin). On giving an account of this adventure, Jack said he could not make much of it, but it seemed to him very like ‘All my eye and Betty Martin’”

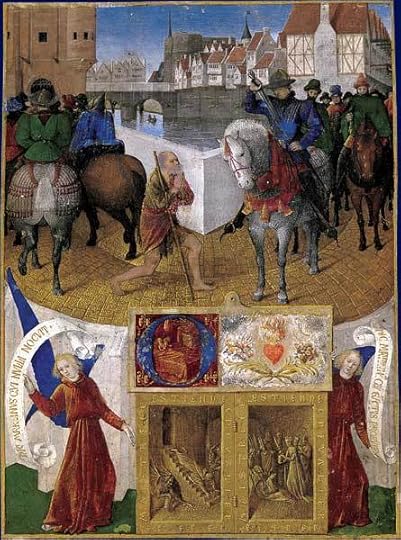

If St. Martin could give half of his cloak to a beggar, could he be the inspiration for our idiom?

If St. Martin could give half of his cloak to a beggar, could he be the inspiration for our idiom?The most cogent objections to this hypothesis were voiced at least as early as the middle of the nineteenth century. To begin with, no such public formulary exists, and the phonetic base of this derivation is beyond redemption. In England, Latin vowels and consonants were for a long time pronounced as though they were English. Caesar’s veni, vidi, vici had the form vee-nigh, vie-die, vie-sigh. Consequently, our naïve informant must have heard o mihi Beate as oh my-hi bee-a-tee or something like it (still not quite o my eye). Some people realized the problem and sent the sailor abroad.

A charming story, quite seriously repeated by learned men in the nineteen-twenties runs as follows: “A party of gypsies (sic) were apprehended, and taken before a magistrate; the constable gave evidence against an extraordinary woman named Betty Martin; she became violently excited, rushed up to him, and gave him a tremendous blow in the eye. After which the boys and rabble used to follow the unfortunate officer with cries of ‘My eye and Betty Martin’.” A more inspiring conjecture runs as follows: “ There is a phonetic resemblance in Betty Martin to Berta and Martine, Berta of the mill and Martino the thrasher, the Italian types of stupidity, alluded to in Dante, Paradiso, Canto XIII: 139.”

Here is another attack on the idiom. Charles Lee Lewes wrote in his Memoirs (Volume 1: 120-124) that a certain Elizabeth Grace married a young gentleman of a reputable family in county Meath (Ireland) ca. 1741 and refused to support Martin, saying: “Bah, bah, Mr. Gentleman, so I was made your property to maintain your idleness, was I? Oh, my eye, for that my dear. There…. Christopher Martin, there’s the door.” Betty afterwards married a Mr. Workman, became an actress, married many times, and was known for an adventurous life. (Search for Elizabeth Workman, actress.)

Meath, Ireland. Betty Martin’s home?

Meath, Ireland. Betty Martin’s home?This array of guesses will, it can be hoped, dissuade prospective word sleuths from following the cold spoor. But one note should be added to the tale of Betty Martin. Even if we succeeded in discovering the true origin of the saying (for instance, in the Italian names occurring in Dante), it would be necessary to explain how the saying spread, in what milieu it was used, and under what circumstances it caught the popular fancy. Most probably, (all) my eye and Betty Martin is a piece of eighteenth-century slang going back to some anecdote, now lost, unless Betty Martin was added gratuitously to my eye. When there is no evidence, there can be no etymology. Origin unknown. Alas!

Images: (1) “The Drowning of Britomartis, 1547–59” Probably designed by Jean Cousin the Elder, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) “La charité de saint Martin” by Jean Fouquet, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. (3) “Meath Ireland (BI Sect 7)” by Visitor from Wikishire, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post (All) my eye and Betty Martin! appeared first on OUPblog.

5 facts about Black Friday

As families across the United States gather to celebrate Thanksgiving tomorrow, one thing will be on the mind of savvy, deal-hunting shoppers more than turkey, parade floats, football, or even pumpkin pie–Black Friday.

Malls and retail centers of all sizes and specialties will soon be swarmed from corner to corner with people–many who lined up at the entrance well before the stroke of midnight–looking to snag the best deals of the year on nearly every product imaginable.

From an economics standpoint, Black Friday is one of the most important days of the year, as it marks the unofficial start of the busy holiday shopping season. The origin of the term “Black Friday,” however, is not entirely straightforward. We’ve compiled a list of some of the 5 most common explanations for how this infamously chaotic day got its name.

As far back as the 17th century, students used the term Black Friday as part of schoolyard slang to refer to exam days. As such, the day was “characterized by tragic or disastrous events; causing despair or pessimism,” according to one definition from the Oxford Dictionaries.

When referring to a specific day, “black” has historically been used as a general term marking a collapse in prices. For example, Friday 24 September, 1869 is also referred to as Black Friday. On this day, President Ulysses S. Grant released all government-held gold for sale in order to curb the efforts of those trying to corner the country’s gold market. As a result, the price of gold plummeted and a stock market panic was created. In addition, the Wall Street Crash on Tuesday, 29 October, 1929–also referred to as Black Tuesday–ultimately caused the Great Depression.

Todo mundo fazendo black friday… by v1ctor casale. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

Todo mundo fazendo black friday… by v1ctor casale. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.One of the most prevalent explanations of the name Black Friday is that it refers to the first day of the year businesses make a profit, otherwise known as being “in the black” as opposed to “in the red.” In traditional, handwritten bookkeeping practices, an account’s credit was written in black ink, and debit was written in red.

In Philadelphia in the 1960s, the day after Thanksgiving came to be known as Black Friday in reference to the heavy traffic congestion that shoppers caused as they traveled to the city’s retail centers. As a result, public transportation workers and police officers faced difficulties managing the large crowds, and often worked long hours.

Retailers nationwide began turning Black Friday into the holiday shopping extravaganza it is today during the 1980s, offering steep discounts as a way to draw in crowds of eager Americans–and their wallets. Since then, Black Friday has continued to evolve past a single day of sales, spurring the creation and increasing popularity of Brown Thursday, Small Business Saturday, and Cyber Monday.

No matter the truest origin of the term Black Friday, the day continues to attract massive crowds of consumers each year, spurring a positive boost for our nation’s economy. In fact, it is estimated that 137.4 million people plan to shop this weekend, totaling 59% of all Americans!

Are you planning to shop on Black Friday this year?

Featured image:Boxing Day at the Toronto Eaton Centre by 松林 L. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post 5 facts about Black Friday appeared first on OUPblog.

The life and times of Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys penned his famous diaries between January 1660 and the end of May 1669. During the course of this nine year period, England witnessed some of the most important events in its political and social history. The diaries are over a million words long and recount in minute and often incredibly personal detail events such as the restoration of the monarchy, the Second Anglo-Dutch War, the Great Fire, and Great Plague of London. By detailing his daily life with such frankness (Pepys never anticipated his diaries to be so publicly scrutinized) he provided an unprecedented window into the everyday experiences of seventeenth century Londoners as well as major political events.

Find out more about key events in the life of Samuel Pepys with this interactive timeline — from his comments on the coronation of Charles II to his scathing review of A Midsummer Night’s Dream and from the chaos of the Great Fire of London to the devastation left by the Plague.

Featured image credit: ‘The burning of the English fleet off Chatham, 20 June 1667’ by Peter van den Velde, from the Rijks Museum. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post The life and times of Samuel Pepys appeared first on OUPblog.

How the Bible influenced the Founding Fathers

In the midst of political campaigns, including the last election season, one often hears appeals to the American founding principles and the political visions of the founding fathers.

Which political traditions and thinkers shaped the ideas and aspirations of the American founding? Late eighteenth-century Americans were influenced by diverse perspectives, including British constitutionalism, classical and civic republicanism, and Enlightenment liberalism. Among the works frequently said to have influenced the founders are John Locke’s Two Treatises of Government, Montesquieu’s The Spirit of the Laws, and William Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England.

Another, often overlooked or discounted source of influence is the Bible. Its expansive influence on the political culture of the age should not surprise us because the population was overwhelming Protestant, and it informed significant aspects of public culture, including language, letters, education, and law. No book at the time was more accessible or familiar than the English Bible, specifically the King James Bible. And the people were biblically literate.

The discourse of the era amply documents the founders’ many quotations from and allusions to both familiar and obscure biblical texts, confirming that they knew the Bible from cover to cover. Biblical language and themes liberally seasoned their rhetoric. The phrases and cadences of the King James Bible influenced their written and spoken words. Its ideas shaped their habits of mind and informed their political experiment in republican self-government.

The Bible left its mark on their political culture. Following an extensive survey of American political literature from 1760 to 1805, political scientist Donald S. Lutz reported that the Bible was cited more frequently than any European writer or even any European school of thought, such as Enlightenment liberalism or republicanism. The Bible, he reported, accounted for approximately one-third of the citations in the literature he surveyed. The book of Deuteronomy alone is the most frequently cited work, followed by Montesquieu’s The Spirit of the Laws. In fact, Deuteronomy is referenced nearly twice as often as Locke’s writings, and the Apostle Paul is mentioned about as frequently as Montesquieu.

Many in the founding generation–98% or more of whom were affiliated with Protestant Christianity–regarded the Bible as indispensable to their political experiment in self-government. They valued the Bible not only for its rich literary qualities but also for its insights into human nature, civic virtue, social order, political authority and other concepts essential to the establishment of a political society. The Bible, many believed, provided instruction on the characteristics of a righteous civil magistrate, conceptions of liberty, and the rights and responsibilities of citizens, including the right of resistance to tyrannical rule. There was broad agreement that the Bible was essential for nurturing the civic virtues that give citizens the capacity for self-government. Many founders also saw in the Bible political and legal models–such as republicanism, separation of powers, federalism, and due process of law–they believed enjoyed divine favor and were worthy of emulation in their polities.

Declaration of Independence by John Trumball. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Declaration of Independence by John Trumball. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.The political discourse of the founding, for one example, is replete with appeals to the Hebrew “republic” as a model for their own political experiment. In an influential 1775 Massachusetts election sermon, Samuel Langdon, the president of Harvard College and later a delegate to New Hampshire’s constitution ratifying convention, opined: “The Jewish government, according to the original constitution which was divinely established, … was a perfect Republic … The civil Polity of Israel is doubtless an excellent general model …; at least some principal laws and orders of it may be copied, to great advantage, in more modern establishments.” Most of what the founders knew about the Hebraic republic they learned from the Bible. These Americans were well aware that ideas like republicanism found expression in traditions apart from the Hebrew model, and, indeed, they studied these traditions both ancient and modern. The republican model found in the Hebrew Scriptures, however, reassured pious Americans that republicanism was a political system favored by God.

Focusing on the Bible’s impact on the political culture of the founding is not intended to discount, much less dismiss, other sources of influence that informed the American political experiment. Rather, I contend that casting a light on the often ignored place of the Bible in late eighteenth-century political thought enriches one’s understanding of the ideas that contributed to the founding project.

Does it matter whether the Bible is studied alongside other intellectual influences on the founding? Yes, because biblical language, themes, and principles pervaded eighteenth-century political thought and action. Accordingly, an awareness of the Bible’s contributions to the founding project increases knowledge of the founders’ political experiment and their systems of civil government and law. A study of how the founding generation read and used the Bible helps Americans understand themselves, their history, and their regime of republican self-government and liberty under law.

Headline image credit: Shema Israel – (שמע ישראל) by Yaniv Ben-Arie. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post How the Bible influenced the Founding Fathers appeared first on OUPblog.

November 22, 2016

The impact of the press on the American Revolution

Issues of the press seem increasingly relevant in light of the recent U.S. presidential election. At its best, the press can play a critical role in informing, educating, and shaping the public’s thoughts—just as it did at the time of the nation’s founding. In fact, the press was so crucial in those early days that David Ramsay, one of the first historians of the American Revolution, wrote that: “In establishing American independence, the pen and press had merit equal to that of the sword.” To illustrate the influential role of the press in the formation of the United States, we’ve pulled out some interesting highlights from Robert G. Parkinson’s article, “Print, the Press, and the American Revolution,” for the Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History.

Because of the unstable and fragile notions of unity among the thirteen American colonies, print acted as a binding agent that mitigated the chances that the colonies would not support one another when war with Britain broke out in 1775. Stories that appeared in each paper were “exchanged” from other papers in different cities, creating a uniform effect akin to a modern news wire. The exchange system allowed for the same story to appear across North America, and it provided the Revolutionaries with a method to shore up that fragile sense of unity.

Pamphlets became strategic conveyors of ideas during the imperial crisis

Often written by elites under pseudonyms, pamphlets have long been held up by historians as agents of change in and of themselves—that texts like Thomas Paine’s Common Sense or John Dickinson’s Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, to name two of the most famous, are often seen as actors themselves, driving the resistance movement forward.”

The concept of anonymity transformed during the imperial crisis

Long a key feature of 18th-century print culture, with the republican claims of the patriots, anonymity took on a new significance in print, one that allowed for a broader inclusion of the public, and, by implication, the possibility of greater purchase by the people at large. As a rule, contributors to the newspapers shielded themselves with pseudonyms, often judiciously employed to cast themselves as public defenders (“Populus,” “Salus Populi,” “Rusticus”) or guardians of ancient liberty and virtue (“Mucius Scaevola,” “Cato,” “Nestor,” “Neoptelemus”). As one literary scholar has suggested, by adopting such identities those “guardians” were then not real, individual inhabitants of Boston or Philadelphia, with particular social interests, but universal promoters of republican liberty. Analysts often point to the destruction of the concept of deference—a staple of 18th-century social structure—as a sign of the Revolution’s radicalness.

Printers mediated several fluid and rapidly changing concepts of both their professions and colonial politics before the Revolution. They were the keepers of very important political secrets.

Publishing loyalist pamphlets could have been dangerous for those who opposed the revolution.

Printers mediated several fluid and rapidly changing concepts of both their professions and colonial politics before the Revolution. They were the keepers of very important political secrets. They alone knew who had submitted a manuscript for publication; only they could pierce the republican fiction of anonymity. Often, this position was precarious. As political pressure increased in the 1760s and 1770s, the impulse to throw off these veils was occasionally very strong. Printers periodically found themselves or their property in harm’s way if they refused to bow to the will of angry demands that they confess.

In 1776, when New York Packet printer Samuel Loudon dared to advertise the publication of a pamphlet that answered Tom Paine’s Common Sense and called the “scheme of Independence ruinous and delusive,” the Mechanics Committee, a radical patriot group created in 1774 out of the Sons of Liberty, summoned the printer to explain his behavior and reveal the author’s identity. Loudon refused to tell the committee the Anglican rector of Trinity Church, Charles Inglis, had written the pamphlet, so six members of the committee went to his shop and, in Loudon’s words, “nailed and sealed up the printed sheets in boxes, except a few which were drying in an empty house, which they locked, and took the key with them.” They warned Loudon to stop publishing the pamphlet, or else his “personal safety might be endangered.”

(Loyalists) Mein and Fleeming sought to embarrass the Sons of Liberty … by revealing the caprice and self-interest that they thought really actuated the non-importation boycott the Sons had organized to resist the Townshend Duties. The Chronicle featured fifty-five lists of shipping manifests revealing the names of merchants who broke the non-importation agreement, including many who had actually signed the boycott. In response it was many upset Bostonians who embraced vigilantism this time. Mein and Fleeming had published the lists to suggest the boycott was really an effort to eliminate business competition on the part of merchants sympathetic to the Sons. Now they had to stuff pistols in their pockets to walk the streets of Boston. In October the Boston town meeting condemned Mein as an enemy of his country, and a few days later a large crowd confronted the offending printers on King Street, producing a scuffle that left Mein bruised, Fleeming’s pistol empty, and a few dozen angry Bostonians facing British bayonets. Mein at first took shelter in the guardhouse, but, when Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson did not offer vigorous support, the truculent printer departed for England.

As printers increasingly gave space to contributors who claimed they were unmasking corruption or conspiracy, they aided in the disintegration of established concepts of what kept a press “free.”

The most impassioned publications of the 1760s and 1770s—Dickinson’s Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, the chronicle of soldiers’ abuses known as the “Journal of Occurrences,” Paul Revere’s engraving of the Boston Massacre, and Thomas Hutchinson’s private letters—all centered on revealing or dramatizing the government’s true aims of stripping American colonists of their liberties. There were not two sides to “truth.” Either behind pseudonyms or not, the patriot writers or artists who brought these plots to light claimed they were heroic servants of the people, informants seeking to protect an unwitting public from tyranny’s stealthy advance. This was not a debate. So framed, it was also a difficult position to counter. At the same time, the appearance of each of these “exposés” also represented a choice by the printers themselves. By giving space to the “truth”—and, by extension, to the protection of the people’s rights—they took a side that changed the older values of press freedom forever. A free or open press, they decided, did not have to allow equal space for opposing viewpoints that they characterized as endorsing lies and tyranny.

Featured image credit: “Join, or Die” by Benjamin Franklin. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The impact of the press on the American Revolution appeared first on OUPblog.

The future of the NHS – let’s not lose sight of what is important

There is general agreement that the National Health Service (NHS) in the United Kingdom is currently facing unprecedented challenges. Many of these challenges face all health services: increasing demand for healthcare arising from technological developments, demographic changes, rising expectations, and the increase in chronic diseases that require long-term coordinated care.

In terms of public spending, the United Kingdom has entered a period of austerity. Under the Coalition government (2010-2015), spending increased by 0.8% but growth in demand was 3-4%, resulting in a shortfall in funding. According to the 2015 Kings Fund verdict, although ‘[t]he coalition government met its commitment to increase NHS funding in real terms over the course of the parliament, […] this was less than the growth required to meet demand.’ The Kings Fund “Deficits in the NHS 2016” report found that ‘NHS providers and commissioners ended 2015/16 with an aggregate deficit of £1.85 billion, […] the largest aggregate deficit in NHS history.’ It has been estimated that by 2020/21 there will be a gap of £22 billion between patient need and NHS resources. The suggested solution to this shortfall is for the NHS to make efficiency savings rather than to expect more funding.

However, as Chris Ham has noted, money designated for transforming the NHS and priming new care models, as set out in the Five Year Forward View (2014), is being used for sustainability and deficit reduction rather than improvements that could lead to more efficiency. These pressures are set to continue, with Brexit bringing financial uncertainty and the current government’s statement in October 2016 that no more money will be forthcoming for the NHS.

The response to this ‘funding crisis’ in the NHS has been fascinating and illustrates how choices that would not have been seriously discussed 20-30 years ago are now being considered as possible policy options. User charges are on the agenda and professional bodies such as the BMA have discussed whether patients should be charged for GP visits. Examining the NHS in Wales, the Nuffield Trust commented: ‘it is difficult to see how the NHS as we know it can be sustained without significant change in public spending policy or the approach to its financing.’ The House of Lords has recently appointed a Select Committee in June 2016 to look at the long-term financial sustainability of the NHS and will consider, among other things, ‘alternative types of funding (eg. charging for some services, encouraging greater private spending, limiting what the NHS provides)’. This all indicates that the parameters of the debate over how healthcare is funded are changing.

Ambulance by Jon Hunt. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

Ambulance by Jon Hunt. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.Alongside financial pressures, the NHS has also undergone significant organisational changes with the 2012 Health and Social Care Act. This was the culmination of policy measures over last 30 years that questioned state provision of welfare and goods. These twin elements have resulted in a heated debate over the very future of the NHS. This debate has become crystallised over the big issue of whether we can afford to continue with the NHS, as it is now a, more or less, publicly funded body – or if we need some form of radical change such as introducing insurance models of funding or moving away from the principle of ‘free at the point of delivery’.

These debates have been focussed very much at the economic level – what can we afford, how can we get more from the money we do spend, how can we get extra resources into the system (i.e. through top-up charges or more private spending). However, this is a debate that needs to be based on a consideration of what type of health service we want. As Nick Black has noted in his evidence to the House of Lords Committee, there is a political question of ‘how much we want to spend on health and social care as a society […and] how fair we want the distribution of those services to be.’ The kinds of social values and type of society we want to promulgate are key (yet often neglected) areas that should be central to this debate. As the eminent health economist Alan Maynard says, ‘ensuring that people don’t have to pay out of their own pockets in times of ill health and enshrining the principle of collective responsibility for each other’s healthcare, remains essential.’

At root, much of this discussion is driven by ideological or political considerations: do we want a more free-market approach to welfare provision, underpinned by a conception of negative rights, or should certain goods be provided by the state and ‘social rights’ safeguarded and given priority? Health care funding and financing raises important philosophical and ethical questions which are, at root, about the role of the state in the provision of key resources and the extent of state responsibility to individual citizens. The answers to these questions have implications for the public-private mix in health and social care financing and provision.

There is now a pressing need for public debate over these issues – a renewed consideration of what type of health service and, ultimately, society we want. To my mind, a commitment to healthcare as a societal good and collective responsibility for healthcare (coupled with a greater reliance on evidence of what works) should frame the policy agenda so that healthcare in England remains globally respected and can continue to improve and develop in the 21st century.

Feature image: Medical by Darko Stojanovic. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post The future of the NHS – let’s not lose sight of what is important appeared first on OUPblog.

A Q & A with Amelia Carruthers, marketing executive for online products

We caught up with Amelia Carruthers, who joined Oxford University Press in June 2015 and is now currently a Marketing Executive for the Global Online Products team. She talks to us about working on online products, her own publishing, and her OUP journey so far.

When did you start working at OUP?

I started working at OUP in the summer of 2015 as an intern with the social media team. It was a great introduction to the company, allowing me to gain an insight into so many different departments and roles. After that, I spent a year with the medicine books marketing team before joining online products this September.

What was your first job in publishing?

I moved to Oxford from Bristol, where I worked as a writer and editor for an independent publisher, specialising in rare and vintage books. As a very small company, it was a great experience, and I was even able to manage some of my own series. Origins of Fairy Tales from Around the World was my favourite project to write and research; a series looking at folkloric tales and their adaptations over time.

What’s the first thing you do when you get to work in the morning?

Try to avoid the temptation of hot breakfasts in the canteen. Limited success rates.

What is the strangest thing currently on or in your desk?

Two very large, very heavy, owl book-ends. They were a present from my mum that I’ve never quite found the energy to carry home – put to great use when I worked in books marketing, but somewhat redundant now I deal solely in online products!

If you didn’t work in publishing, what would you be doing?

Amelia Carruthers, used with permission of the author.

Amelia Carruthers, used with permission of the author.I very narrowly escaped a life in academia, having left a PhD in Modern History to come to Oxford, and have always enjoyed arts-writing. I still run an arts blog discussing all things art and philosophy in my spare time. Despite this, my dream ‘alternative’ job has always been working in a bakery, preferably in the South of France with baguettes and bicycles (with a possible bee-hive too, I’ll see how it goes).

Open the book you’re currently reading and turn to page 75. Tell us the title of the book, and the third sentence on that page.

Steppenwolf by Herman Hesse:

“The “man” of this concordat, like every other bourgeois ideal, is a compromise, a timid and artlessly sly experiment, with the aim of cheating both the angry primal mother Nature and the troublesome primal father Spirit of their pressing claims, and of living in a temperate zone between the two of them.”

What is the longest book you’ve ever read?

Probably Crime and Punishment at 720 pages, which is also one of my favourite books. I was going to go for Montaigne’s Essays at 1,360 pages, but there’s still a few I haven’t finished. ‘Of Thumbs’ is one of the shortest and strangest – definitely worth a read.

What is your favourite animal?

Dogs. I grew up with two of the loveliest black Labradors, one of whom (Muffin) is still around — tottering about the house with the greyest of beards. She had her moment of fame in an OUP animals post.

What will you be doing once you’ve completed this Q&A?

Putting together some quizzes, maps and timelines — on subjects as varied as Shakespearean pronunciation, ‘quotes of the year’, world nuclear forces, and ‘the life and times of Samuel Pepys’. This is a really enjoyable part of my job — getting to create all manner of fun content. Apart from that, going over the strategy documents I’ve written over the past couple of weeks, and trying to put some plans into action!

What is your favourite word?

I love crazy German words that don’t have a direct English translation – is that cheating? Things like Treppenwitz (literally meaning staircase joke) – the witty retort that inevitably comes to mind two hours after a tricky conversation, walking up the staircase at home. Or Fremdschämen (exterior shame) – the uncontrollable feeling of cringing on someone else’s behalf, whilst witnessing an embarrassing situation.

Tell us about one of your proudest moments at work.

When I first started at OUP, walking through the building’s grand columned entrance for the first time was pretty special. The lovely send-off and kind words from all my colleagues when I moved departments also made me feel very proud, and grateful too.

How would you sum your job up in 3 words?

Exciting, varied, and busy.

Featured image credit: Oxford, Street, England by Keem1201. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post A Q & A with Amelia Carruthers, marketing executive for online products appeared first on OUPblog.

Fostering friendly relations between Hitler’s Germany and Franco’s Spain through music

As the Wehrmacht launched its offensive on the USSR in summer 1941, a contingent of Spanish musicians and critics traveled to Bad Elster, on the border between Bavaria and Bohemia. In the spa town, they took part in the first of three Hispanic-German music festivals held during the Second World War aimed at fostering cultural and political understanding between both countries.

The timing of the festival illustrates how the relations between Hitler’s Germany and Franco’s Spain were often founded on opportunism and pragmatism rather than on pure ideological affinity. When the Second World War was declared, Franco claimed neutrality; with Spain just out of a three-year long civil war, a second conflict could have dashed all hopes of reconstruction. Subsequently, though, he entertained the idea of entering the war on the side of the Axis. A meeting between Franco and Hitler took place in Hendaye on 23 October 1940, with no agreement being reached, but the Russian in summer 1941 campaign lifted Franco’s hopes again. Indeed, it was only a few days before the festival started that Franco’s Foreign Affairs minister, Ramón Serrano Súñer, admitted to a German newspaper that Spain had moved from non-belligerency to moral belligerency.

The Spanish expedition included pianist José Cubiles, who had toured Germany during the Spanish Civil War playing recitals in swastika-clad concert halls; guitarist Regino Sáinz de la Maza, an enthusiastic member of Falange, the Spanish fascist party; composer Joaquín Rodrigo, who had recently reached household name status in post-Civil War Spain with his Concierto de Aranjuez; and Federico Sopeña, then at the beginning of a prolonged career as a music critic and administrator. Sopeña was the one to best capture the spirit of the festival, writing on 3rd August 1941 for the Spanish newspaper Arriba:

The fact that the most musical of nations, Germany, organizes in the middle of the war a series of concerts dedicated to Spanish music is not only a sign of vitality, but also a symbol of what unites these two nations, whose sons again fight against their universal enemy: Communism. (…) Tomorrow, our shared triumph in the trenches which protect the best essences of both nations will originate a new artistic communion.

In a country devastated by civil war and repression, stories about performers, authorities and critics travelling around Europe to pay homage to music likely very attractive: later in 1941, the chronicles that Sopeña and composer Joaquín Turina sent from Vienna, where they took part in the Mozart centenary celebrations at the invitation of the Reich’s government, described in detail the palaces and the atmosphere of the city, and not only what they had heard in the concert halls. But such writings, as well as the events they reviewed themselves, also presented an opportunity to subtly disseminate notions about Spain’s role in the world order that the regime’s ideologues were developing elsewhere. Poet José María Pemán argued that German and Italian aid to Franco’s Spain reawakened the old imperial brotherhood of the Hapsburg Empire and Rome, and Falange founder Ernesto Giménez Caballero stated that Aryan ‘blonde’ peoples needed to form alliances with other Aryan ‘black-haired’ peoples so that both could accomplish their destinies – in an attempt at justifying Germany’s alliances with Italy and Spain with historical and racial arguments.

Several of the Spanish-German musical exchanges which took place from the beginning of the Second World War to late 1943 were explicitly political. On the occasion of the second Hispanic-German festival, which took place in Madrid and San Sebastián in 1942, the German and Spanish delegations paid tribute the tomb of José Antonio Primo de Rivera, founder of Falange. Other musical events were meant to support the war effort: in May 1943 Hans Knapperbutsch conducted the Berliner Philharmonie – one of four times that the orchestra toured Spain during the Second World War – to help support financially the División Azul – a group of approximately 20,000 Spanish volunteers who fought with the German army on the Eastern front between summer 1941 and autumn 1943

When I first came across the musical exchanges between Franco’s Spain and Hitler’s Germany as I started my doctoral research in 2006, I was astounded that such events, which helped translate ideological and diplomatic maneuvering into something greater contingents of Spaniards could understand, did not feature at all into Spain’s memory of the dictatorship; in fact, at the time they were even marginal in academic research, brushed under the broad category of propaganda or even ignored completely. Nevertheless, although the rhetoric surrounding the festivals would be unacceptable to most Spaniards today, their legacy can still be felt. The festivals forced those in charge of musical policies under Franco to think about what their musical canon was – the selection of composers and works they wanted to present to Germany, regarded at the time as the model nation in music. Whereas some names in the Spanish canon had been well-established for decades (Albéniz, Granados, Falla), it was in the selection of their own contemporaries that Francoist officers left the most durable footprint: with a significant number of composers in their twenties, thirties and forties having gone into exile or at least left public musical life as a consequence of the Franco regime, the festival showcased the work of Joaquín Rodrigo and Ernesto Halffter, both of them firmly entrenched in the tonal, nationalist field – suitably modern but not too dissonant. Both of them, especially Rodrigo, still embody to a great extent how Spanish music of the mid-twentieth century is perceived both in Spain and abroad, at the detriment of other musical languages Spanish composers cultivated contemporaneously, both in Spain and in exile.

Featured image: “Banda de Gaites Naranco” by Michel Curi. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Fostering friendly relations between Hitler’s Germany and Franco’s Spain through music appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers