Oxford University Press's Blog, page 435

November 30, 2016

Etymology gleanings for November 2016

I keep receiving this question with some regularity (once a year or so), and, since I have answered it several times, I’ll confine myself to a few very general remarks. Etymology is a branch of historical linguistics dealing with the origin of words. It looks at the sound shape and meaning of words and at the cultural milieu in which words were coined. Quite often a word has related forms in several languages, and all of them have to be compared. The most time-consuming part of an etymologist’s education consists in learning which sound correspondences look helpful and which should be discarded. But even in this area one should not be dogmatic, because words are not soldiers marching forward in serried ranks and tend to escape the prescribed formations. Comparative semantics is based on vaguer rules, but they too have to be explored. By contrast, isolated words are hard because they are isolated!

Words are not like soldiers in serried ranks.

Words are not like soldiers in serried ranks.The usefulness of the historical milieu needs no proof. If you study the origin of the word bed, you should learn as much as possible about the type of beds people slept in, and, if your subject is the etymology of god, the more you know about comparative religion, the better. Ideally, etymologists should have years of research behind them before they can risk bringing forward even the most tentative hypotheses. Some old ideas were not bad, but, in principle, guesswork yielded to reasonable constructions only at the beginning of the nineteenth century. In the course of the last two hundred years mountains of books and articles have been written about the derivation of words in various languages. There is no use in coming up with a conjecture without at least some knowledge of what the predecessors had to say. Etymology is incredibly interesting and rewarding, but it exacts a high price from its practitioners. It should be added that etymology interests many people, but in today’s academia being able to explain the origin of words is not a marketable skill. Good luck!

Fog and fox

I devoted two posts to the word fog (November 9 and November 16) and some time earlier two posts to the word fox ( and March 23) but did not exhaust either subject and would like to add something to what was said there. Long ago, I read a book by Ludwig Laistner Nebelsagen, that is, “Stories of the Mist” (1879) and found it extremely interesting. Outside the anthroposophic circle of Rudolf Steiner’s devotees, not many people turn to Laistner’s writings today, but Rita Caprini did. In 1983, she published an article with the terse title “Fox, fog” (Quaderni di semantica 4, 59-68; the article is in Italian). As I understand, Laistner’s book was one of her main inspirations, but, not unexpectedly, she was also fully aware of the recent literature on the subject.

In the myths of many peoples, the fox causes the mist (it cooks or brews the mist, and so forth). Caprini emphasized the idea that Engl. fog “coarse grass, aftermath” is often reddish, while the phonetic proximity between fox and fog needs no proof. Her conclusions are guarded, but perhaps one may offer a more definite etymology. In the second post on fox, I mentioned the hypothesis that the word is of imitative origin. Let it be reminded that –s in fox (fok-s) is the ending of the masculine gender; the word’s old root is approximately foh-. Allegedly, this foh– represents the “gesture” we make while giving a whiff (blowing) and trying to get rid of an unpleasant smell. See also Johan Palme’s comment after my post.

That the fox is an ill-smelling animal has always been known. Russian pukh “down, light fluff” can be related to fox, as many etymologists believe; both words have the root designating “light stuff easily tossed by the wind.” In my story of fog, I wrote that fog “mist” and fog “coarse grass” are related (another old idea) and that both go back to the sound-imitative root designating blowing (hence the movement of the air, wind, with further development from “wind” to “wet wind” and “wetness” in general; initially, fog “grass” was associated with wet places). If this reconstruction is correct, the closeness of fox to fog no longer causes surprise. However, the foundation of the myth remains partly obscure, because Engl. fog is isolated, while the superstition is widespread. “Food for thought,” as they say. To provide the series with a good finishing touch, next week I’ll discuss the origin of the word mist.

Another comment on fog came from my Romanian correspondent Ion Carstoiu. He sent me his etymology written twenty-five years ago. The first part of his note deals with the common tie between words for “sky” and “cloud.” There is no need to cite all his examples. Latin nebula “mist, fog” and Russian nebo “sky” tell the story quite well (compare the obsolete Engl. welkin “sky” and German Wolke “cloud,” to add a pair Carstoiu did not cite). It is his second step that looks perilous to me. He compares Old Iranian bag, which he glosses as “sky,” compares it with Russian bog “god,” and suggests that bog is related to Engl. fog. The idea of b becoming f before a stressed vowel has a weak foundation (there are no analogs in English), and the suggestion that bog at one time meant “sky” needs more proof (see the end of my post for 19 August 2015: the etymology of god). Another obstacle to his reconstruction is the isolated character of Engl. fog.

Who can deny the connection between the cloud and the sky?

Who can deny the connection between the cloud and the sky?The spelling of proceed versus recede

Why do we spell excEED, procEED, and succEED but accEDE and recEDE (among others)? The reason is the chaotic spelling English inherited from its past epochs. This chaos could have been “ordered” by a reasonable spelling reform, but such a reform is evidently not forthcoming. All the words mentioned above are of French origin and are related to cede. The radical vowel in them goes back to closed long e, and the vacillation between ede and eed is arbitrary, often dating to the sixteenth or the seventeenth century. Thus, there is no rational explanation. One has to learn the spelling of such words mechanically, as one learns hieroglyphics. Too bad!

A postscript to curse

See the posts for October 19 and November 2. There is the phrase not worth a curse. Several attempts exist to explain it. According to some people, curse is here a variant of kerse “a small sour wild cherry” or cress “an insignificant weed” (due to metathesis); compare not worth a fig, the pip of a fig, a straw, and the like. One can also say not worth a tinker’s damn. Damn here may go back to the name of a small Indian coin confused with Engl. damn. Once that phrase arose, curse was allegedly substituted for damn, regardless of whether tinkers swear more than anyone else. “Origin (still) unknown….”

Which one is not worth a curse?

Which one is not worth a curse?FINALLY, my thanks to Stephen Goranson and John Cowan for their latest remarks on Betty Martin!

Image credits: (1) Sgt. Lauren Twigg Muster Photos by Arizona National Guard. Public Domain via Flickr. (2) Tree Natur by Bessi. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay. (3) Cherries by PublicDomainPictures. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay. Cress Herbs by Pezibear. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Etymology gleanings for November 2016 appeared first on OUPblog.

Which “little woman” are you? [quiz]

The twenty-ninth of November 2016, marked the 184th birthday of American author Louisa May Alcott, best known for her literary classic Little Women. Taking place in New England during the Civil War, Little Women follows Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy–four strong-minded sisters, each determined to discover and fulfill her destiny. Adapted for film six times, Little Women is a coming-of-age story that has influenced young women for generations. Take the quiz below to see which March sister you align with most.

Featured image credit: “Frontispiece illustration from part 2 of Little Women by Louisa May Alcott” illustrated by her sister May Alcott. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Which “little woman” are you? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

Moving crisis management from the ‘war room’ to the board room

Organisations that suffer a major crisis have more than a one in four chance of going out of business. Yet despite this level of risk, many companies continue to leave crisis management in the hands of operational middle managers or inexperienced technicians.

Corporate crisis management traditionally has a strong emphasis on tactical elements such as crisis manuals, cross-functional teams, table-top simulations, communications procedures and a well-equipped ‘war room.’ However, leading companies are now taking a more proactive role in crisis planning and issue management, shifting from reactive crisis response to proactive crisis prevention, and moving the focus from the war room to the board room.

But progress is slow. A global survey of board members, published in early 2016, found that fewer than half of the non-executive directors questioned reported they had engaged with management to understand what was being done to support crisis preparedness. And only half the boards had undertaken specific discussion with management about crisis prevention. Moreover, fewer than half of the respondents believed their organisations had the capabilities or processes needed to meet a crisis with the best possible outcome.

The reality is that many organisations still fail to prepare properly and continue to treat crisis management as an operationalised part of the emergency or security function. That may provide an adequate response to an incident when it happens, but contributes nothing to crisis prevention, long-term value, or reputation management.

The other key factor driving increasing senior executive involvement has been the acknowledgment that most crises which threaten a company are not sudden, unexpected events, but are preceded by clear warning signals, which are frequently ignored. In fact, the Institute for Crisis Management in Denver, Colorado, which has been tracking business crises in the media for well over 20 years, concludes that about two thirds of crises are not unexpected at all, but are what they categorise as ‘smouldering crises’ – events which should have and could have prompted prior intervention (and more than half of all corporate crises are in fact caused by management).

Board Room by Benjamin Child. Public domain via Unsplash.

Board Room by Benjamin Child. Public domain via Unsplash.Together these two factors – that most crises are not truly unexpected and that many are avoidable – have fueled the move from the operational emergency context of the war room to strategic planning in the board room.

This evolution towards strategic recognition and prevention rather than tactical response has in turn expanded the crisis management role of top executives and directors. However it has also exposed a practical challenge. Most managers want to do what’s right for their organisation. Yet some struggle with deciding exactly what needs to be done to protect against the reputational and organisational damage threatened by a crisis or major public issue.

One response to this challenge is Crisis Proofing, which focuses on the role of executive managers and the practical steps they can take to prevent crises and protect reputation. The barriers to effective crisis prevention and preparedness are well documented, but can be best summed up in two common responses: ‘It won’t happen to us’ or ‘We are too big/too well run to be affected by a crisis.’

Many directors and senior executives would prefer not to think about crises, so participation in crisis management does not always sell well at the top. But every top manager should be concerned with preventing crises and protecting the company’s reputation.

If crises are to be prevented before they occur, issues and problems need to be identified early, and acted upon at the highest level. While this may require a fresh mindset, the quality of executive and board involvement can make a real difference to crisis prevention and management, and there are some basic requirements which help facilitate this approach:

Integrating issue management and crisis prevention into strategic planning and enterprise risk management

Encouraging blame-free upward communication and willingly accepting bad news and dissenting opinion

Implementing and regularly reviewing best practice processes for identifying and managing issues before they become crises

Establishing robust mechanisms to recognise and respond to crises at all levels, both operational and managerial

Benchmarking crisis management systems against peer companies and peer industries

Participating in regular crisis management training

Promoting systematic learning from your own issues and crises, and the issues and crises of others

Providing leadership, expertise, experience, and support in the event of a real crisis.

Developing a genuine crisis prevention approach, instead of focusing on crisis response, gives senior executives the responsibility to protect the organization and prevent crises from the top.

A version of this post originally appeared on the Oxford Australia Blog.

Featured image credit: Architecture blue building by PublicDomain Pictures. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Moving crisis management from the ‘war room’ to the board room appeared first on OUPblog.

Can medieval apocalypse commentaries help us feel better about the US election?

In 1453, medieval Europeans were reeling. The great Christian city of Constantinople, which had stood as the capital of the Eastern half of the Roman Empire for over a thousand years, was conquered by the Muslim Ottoman Turks. The militarily superior Turks had been expanding into the Christian territories for more than a century. It was almost inevitable that they would take Constantinople. But few in the West expected this blow. Constantinople was a symbol of Christian (and Roman) strength and continuity. Hence, the Muslim conquest of this city was met in the West with shock and anguish. While we might not agree, medieval Europeans were convinced that the inconceivable had occurred, and that evil had triumphed.

This followed upon another shock—a political one. A number of individuals had spent the previous decades attempting to change the political structure of the Christian Church. They hoped to combat the absolutism of the Roman pope by insisting that the pope should not act as a sole monarch, but rather should rule in cooperation with a council of Church leaders. They summoned councils dedicated to reforming financial abuses within the Church and to overturning a corrupt status quo. These “conciliarists” were soundly defeated. Their ideological opponents destroyed attempts by Church councils to limit the power of the pope and crushed the efforts of these councils to introduce reform.

These two blows—the conquest of Constantinople and the defeat of the “conciliarists”—appeared to medieval Europeans to be connected. Many concluded that corruption in Christendom had prompted God to abandon Constantinople, and that the End Times must be at hand.

Can you imagine how these defeated individuals felt? The entity to which they were entirely devoted, to which they owed their greatest loyalty, their hope, and their support was the Church. They now had to face a future in which the leaders of the Church would not represent their values, and the Church itself would not function for the good of the Christian community (as they saw it). And directly as a result of the Church’s failed reform, “infidels” had successfully taken one of Christendom’s most holy cities.

What were their options? They could not, and would not, abandon the Church, which for them represented the only chance of salvation. Instead they turned to deep and agonized soul searching. They sought the source of their misery within their own society. They wrote treatises with chapters titled “On the sins which caused the affliction of the Church,” and “On how the present affliction is worse than any that came before.”

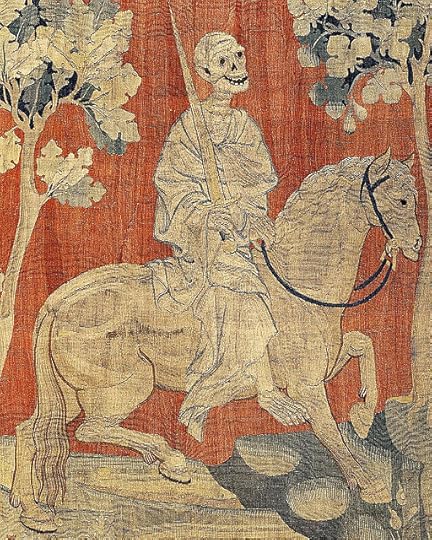

The apocalypse of Angers. Drawings: Hennequin de Bruges. Weaving: Robert Poinçon’s team, in Nicolas Bataille’s factory. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The apocalypse of Angers. Drawings: Hennequin de Bruges. Weaving: Robert Poinçon’s team, in Nicolas Bataille’s factory. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Their afflictions were the result of sin, they concluded. But to say that they blamed “sin” is misleading, because they saw specific human actions as the causes of God’s wrath. It was the powerful Church leaders whom protest writers held responsible, citing their resistance to reform and their pursuit of self-interest.

One frightened monk experienced a vision in which he spoke with God. The monk begged God to explain why he chastised the Church. God replied that he punished the Church so severely in order to provoke change. God informed the weeping monk that the Christian Church “has reached such a state of extreme deformation, ruin, perversity, and ingratitude that it cannot reform itself, because its highest officials are in fact its most depraved, and they lie without blushing.”

The leadership of the Church were meant to protect their flocks and lead them to salvation. Instead, they had abandoned their flocks to chase gold and power. One author railed that reform had been thwarted by the resistance of “those of the highest rank,” i.e. the wealthy and powerful. Another pointed out that corruption was “principally carried out by those who ought to remove and cure such vices, not participate in them.” Yet another asserted, “This is how things now stand in the Church. Its leaders do not burn with the fever of charity. They are not even warm!”

Some explained their dramatic losses as precursors of the End Times. They saw their current times reflected in what Paul had described when he wrote, “In the Last Days perilous times will come. For men will be lovers of themselves … lovers of pleasure rather than God.” One writer concluded with a warning: “Perhaps the amassing of evil deeds by the holy pope – who should be striving for reform – prepares the way for the son of perdition, … namely the Antichrist.”

Some concluded that the corruption was so deeply rooted that reform was no longer possible. There was nothing left to do but await the End: “The world descends daily into deeper depravity… to the deepest degradation, until the time that the son of perdition should come…”

Can medieval apocalypse commentary help us feel better? Is it useful to see that others have struggled with gut-wrenching disappointment, with the recognition that they have been beaten by their opposition, that injustice has triumphed? In the doleful rhetoric of 600 years ago, I see myself and my political allies. It is the same heartache, the same defeat of dearly held values and fear for the future.

I will add, though, that there was no ultimate solution, no happy ending. I wish that studying the reaction of disappointed individuals in the fifteenth century resulted in lessons about how to wisely move forward and heal, but it does not. The discouraged dealt with their losses in their own ways—they retreated into prayer, into visions and mysticism, or they placed their hopes in the arrival of the Last Judgment. How many died in bitterness? How many in despair? How many in acceptance? In hope? It is impossible to say.

The monk who spoke with God, at least, seemed to have found hope. In spite of the afflictions around him, God assured him, “The greater the adversities, the darker the times are, the more prosperous will be what follows, and after these will be golden times. I would not permit my people to be pressed down, excepted that I wish for the occasion to raise them up.”

Headline image credit: Donald Trump by Gage Skidmore. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Can medieval apocalypse commentaries help us feel better about the US election? appeared first on OUPblog.

November 29, 2016

Woman as protagonist in BBC’s re-adaption of Conrad’s The Secret Agent

“This country is absurd in its mania for individual liberty”. This is a sentence of eerily timely resonance. With the onset of Brexit and Vladimir Putin’s claim that it will have “traumatic effect” on Britain, BBC’s recent adaption of Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent offers an uncomfortable presentation of politics documented in the murky streets of Victorian Britain.

Published in 1907, and set in 1887, The Secret Agent contextually engages with the Greenwich Bomb Outrage and conveys a story of an anarchist attempting to detonate London in detest of Britain’s overtly politicised liberalism. The uncanny Nostradamus-ism of The Secret Agent has been recognised in the public domain with Peter Lancelot Mallios revealing in his collection Conrad in the 21st Century that following 9/11 attacks, The Secret Agent was “referenced over a hundred times in newspapers, magazine, and online journalistic resources across the world”. With its plot of espionage, global terrorism and suicide bombers, Conrad’s text has become a significant piece in the examination of modernism and terrorism, with critics such as John Gray claiming that Joseph Conrad “can be read as the first great political novelist of the twenty-first century”.

With the recent surge of interest in Conrad’s text following the programme airing in July, one needs to question the contribution that BBC’s adaption offers to the oeuvre of Conrad’s criticism. Tony Marchant’s adaption is acutely aware of global relevance of this text, noting that the “contemporaneity just hit[s]” you “in the face”. Yet, his production precisely fails in this presentation of terrorism. Whereas Conrad’s text is a complex plot of temporality, allusions and non-essentialist ironies, Marchant’s adaption projects Russia as the menacing power and creates a very definite correlation between Europe and non-European terrorism. It is precisely these taxonomies that Conrad stirred away from with the nuances of his writing.

Conrad skilfully conflates the public and private spheres and the institution of terrorism with domesticity through Winnie.

Nevertheless, this adaption offers us something very important to Conradian studies. Vicky McClure’s performance of Winne Verloc, aptly and subtly asserts the female protagonist’s role in Conrad’s narrative. By doing so, this adaption aligns itself with the feminist body of criticism, such as Susan Jones’ Conrad and Women, which challenge the research that claims that Conrad is exclusively a patriarchal writer. In this way, Marchant’s adaption reminds one of Conrad’s purpose for The Secret Agent – to place the female protagonist at the centre of the narrative. In a letter to Ambrose Barker, Conrad wrote that the initial intention of his novel was to write “the history of Winnie Verloc”. In this respect, Merchant’s re-adaption better presents the nuances of the text and significantly challenges the body of Conradian criticism that reductively attest that Conrad’s female characters are simply stoics with no creative influence in his male-dominated, often seafaring stories.

Keeping in tone with other critics on Conrad, Joyce Carol Oates wrote that Conrad’s “quite serious idea of a ‘heroine’” is always someone who “effaces herself completely, who is eager to sacrifice herself in the ecstasy of love for her man”. So how does Winnie Verloc, and Vicky McClure’s portrayal of her character defy this? Winnie, as critics note, is still positioned within the domestic sphere, marries for convenience and believes deeply “life doesn’t stand much looking into”. Yet, Marchant’s adaption gives focus to Winnie’s role and demonstrates how The Secret Agent serves as a re-examination of the female within patriarchal society. Vicky McClure gives credence to Winnie as an active agent within the domestic sphere and poignantly conveys Winnie’s character in a manner that transforms Winnie into a signifier for “everywoman“. Significantly, Winnie is the only protagonist in the novel to manipulate institutional structures – cleverly using the institution of marriage to escape an abusive father and marrying Verloc to ensure security for herself and her disabled brother.

Conrad skilfully conflates the public and private spheres and the institution of terrorism with domesticity through Winnie. Whereas the bombing of the Observatory fails in the narrative, the ultimate act of violence and usurpation of authoritative power lie in Winnie. Out of the three deaths described in The Secret Agent, those of espionage Verloc, pseudo suicide bomber Stevie, and Winnie, only one is described explicitly – Winnie’s murder of her husband Verloc. Yet, the emphasis is not on the murder, but it is Winnie’s psychological being that Conrad focuses on – giving Winnie the ultimate voice in the narrative.

The reviews of Tony Marchant’s broadcast have largely focused on the shortcomings of the adaption to convey the subtle allusion and ironies of Conrad’s plot of terrorism. Nevertheless, despite these limitations, the recent BBC airing offers an important examination of the position of the Victorian woman and the manners in which she can negotiate agency within the androcentric structures of Victorian politics. Marchant’s production achieves the fundamental aim of Conrad’s narrative – to convey the domesticity and passivity of the Victorian woman, and to hold up that stereotyping for critique.

Featured image credit: Joseph Conrad. CC0 Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Woman as protagonist in BBC’s re-adaption of Conrad’s The Secret Agent appeared first on OUPblog.

Conversations and collaborations: lessons from the Charleston Conference

As a first-time attendee of the Charleston Library Conference earlier this month, I knew I was headed for a few idea-charged days, but was overwhelmed by the amount of things I learned from the conference. The conference, according to its website, “is designed to be a collegial gathering of individuals from different areas who discuss the same issues in a non-threatening, friendly, and highly informal environment.” It not only succeeds in creating this friendly gathering, but also spurs questions for the future of libraries and information. I picked three sessions that impacted me, though all of the fantastic sessions and their implications have stayed with me since the end of the conference.

Rolling with the punches … and punching back: the millennial librarian’s approach to library budgets and acquisitions

This session was conducted as a panel between four librarians from libraries of different sizes and scopes. It was also presented as an open discussion surrounding the difficulties and opportunities that come from being labeled a “millennial” in our current generational terminology. The title of the panel immediately grabbed me as I also fall within the “millennial” generation range (generally understood as a person reaching young adulthood in the early 21st century), and was curious about what millennial librarians encounter in their daily work.

I was blown away by the panelists and their experiences. They noted that as early career librarians they feel they have to take on take on substantial, numerous projects to prove themselves, even though the projects might be outside of their skill set. They felt that their age and general stereotypes about millennials are obstacles in forging relationships with colleagues, as well as vendors, and that they had to be defensive about their abilities. I felt that these experiences were hugely important to share in keeping with the conference’s larger mission in forging conversation between diverse people engaged in current issues. Their discussion made me think about the library as a place composed of relationships, as well as its collections and services, and how crucial it is to work together to achieve the best experience for library users.

The questions that came up as I listened were not only about age and starting a career, but about the current state of libraries and budget structures. In general, libraries are operating on reduced budgets, curating leaner collections, and exploring changes to the physical layout. Focusing on staff development throughout these changes is key, noted one of the panelists, and holding events that recognize the users of the library goes a long way towards creating partnerships. Libraries are also moving towards becoming community spaces—the collections are still there to support research, but the need for collaborative environments within the library space is a constant conversation. One librarian noted that making a physical change in the library was a signifier for other changes to come in the library’s focus and mission, which was a similar theme in the next session I attended.

Re-imagining the library: relationships between library collections, space and public services

Following the previous session about millennial librarians, in my mind this session expanded on the idea of using the library space to communicate change to users. Representatives from the University of California, Irvine (UCI) Libraries and the Rotterdam Public Library in the Netherlands presented on current strategies they employ to engage their users and surrounding communities. In the presentation, UCI explored its use of social media and other forms of engagement on campus, while the Rotterdam Public Library discussed reaching out to the surrounding neighborhoods and creating an inclusive environment.

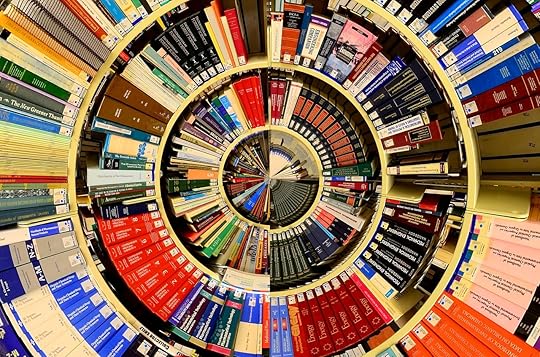

Library electronic by geralt. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

Library electronic by geralt. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.UCI Libraries uses its social media channels to show off library events, users and their personal stories, and interior changes as the libraries go through construction projects. They also plan events in conjunction with other groups on campus, and experiment with different social media broadcasting features like Facebook Live, Periscope, and Instagram Stories to create an online community around the libraries’ activities. All of these strategies help to present UCI Libraries as an inviting place, and one that is committed to communication with its users and the wider world.

The Rotterdam Public Library presented a different but related set of strategies, in opening the library and its offerings up to the larger community of the city of Rotterdam. The library system has recently experienced a 75 percent reduction in the number of branches, but the director of the Rotterdam Public Library wants to change that by 2020 by expanding to 300 locations. Accessibility is one of the key objectives in the director’s plan, moving away from the library system’s previous centralization model. The library hopes to benefit more people by expanding its services, and especially hopes to involve the younger generation in using the library. The library offers video gaming opportunities (including beta testing new video games), live music, and workshops to encourage young adults to come in. It also offers opportunities for the refugee community that has settled in Rotterdam, which demonstrates the library’s goal of accessibility.

Both UCI Libraries’ and the Rotterdam Public Library’s examples of relationship building made me think about a library’s role in our changing world, and how being truly involved requires constant conversations with the community and its interests. Opening up the library to work beyond its walls and engaging with all communities show the library is both a physical space and a call to collaborate.

The nuts and bolts of supporting change and transformation for research libraries

Two librarians from North Carolina State University Libraries led this session, discussing several professional development programs NCSU Libraries have undertaken to empower library staff. These programs include the Data Science and Visualization Institute for Librarians and the Visualization Discussion series. The programs not only show off the expertise and learning opportunities for staff, but also the incredible amount of resources the NCSU Libraries system has to offer in technology and visualization.

The Data and Visualization Institute for Librarians started in the summer of 2014 and consisted of a week-long series of classes about important concepts in data analysis, visualization, content mining, and other topics. The Institute is currently known as the Data Science and Visualization Institute for Librarians and intends to build a community of practice within the librarian workforce. The 27 attendees from the most recent Institute included both NCSU librarians and librarians from other universities and with diverse experiences within the library field. I thought this was a phenomenal idea for encouraging discussion and training between librarians, for librarians. When the Institute isn’t in session, however, NCSU Libraries doesn’t slow down the learning opportunities.

In 2014 the Visualization Services Team at NCSU Libraries developed a “Coffee & Viz” seminar series, which continues today and offers informal discussions led by researchers from different disciplines on tools and techniques for visualization. I looked through the seminar series after the conference, and it included session topics that promote new technologies and support faculty research all while encouraging people to gather in the library to discuss the featured topics. This series combined with the Institute position NCSU Libraries to be a leader in this field and to get people excited about visualization strategies.

From these three sessions, examples of relationship building applied not only to working within the library or library system, but also to the wider community visiting the library. If you also attended the Charleston Conference or are interested in any of the themes presented, please share your thoughts! Let’s keep the conversations going.

Featured image credit: These two: Society Street, Charleston, SC by Hunky Punk. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Conversations and collaborations: lessons from the Charleston Conference appeared first on OUPblog.

November 28, 2016

How Facebook’s Aquila initiative provides an impetus to rethink the boundaries in competition law

Aquila is the Latin word for eagle, but it is also an ambitious Facebook project to provide internet access by solar-powered drones. In India, the project was supposed to provide internet access to the rural and most impoverished areas. Yet, the project was prohibited by the telecoms regulator for several reasons, one being net neutrality. The project would have offered free access to Facebook and some associated web pages and access to the rest of the internet for a fee.

While this case was decided under the telecommunication regime, the issue could equally arise in the context of competition proceedings. The question then would be: should the competition authority take account of the fact that the internet would be available in the rural most impoverished areas in India? This issue goes to the heart of a long-standing debate about the interaction between competition law and public policy. In the following, I argue that we will be seeing more and not less of these issues in the future. It is time to revisit the debate.

A wide held belief amongst the competition community is that competition law and public policy are two separate areas, not to be mixed. Competition cases should be assessed ‘purely’ on competition grounds and issues of public policy should be kept apart. These should be dealt with by other policies areas and the (democratic) policies in place in these areas.

A wide held belief amongst the competition community is that competition law and public policy are two separate areas, not to be mixed.

This thinking is grounded in a specific understanding of the role of the company and the State in society. Economic theory tells us that the company provides private goods while the State provides public goods (those are goods that are non-excludable, non-rivalrous and thus from which no profit can be made—a classical example: national defence). In short, the idea holds that profit maximization by individuals and companies will maximize total welfare (ie for everyone in the society). The role of the State is to address negative externalities and/or to provide public goods. This seems to make sense from a constitutional point of view. The company is concerned about making profit and has no democratic accountability so should not be trusted with issues of public policy. In contrast, the State is (democratically) accountable and therefore possesses the legitimacy to determine what is in the public interest.

At least since the 1950s the traditional understanding of the role of the company in society has been challenged, for example, by the emphasising the social responsibility of the company (Corporate Social Responsibility, CSR). While CSR is rightly viewed critical for the risk of green-washing, a business case for CSR can also be made. For instance, greater consumer demand for environmentally friendly products and higher energy costs are pushing companies to sustainability.

The traditional understanding is also challenged by the idea of social enterprises. The Grameen Bank established by Muhammad Yunus in 1983 and for which he received the Nobel Peace Prize is possibly the most prominent example. While the classical entrepreneur aims at creating wealth through exploiting opportunities, the social entrepreneur aims at creating value for the society through exploiting opportunities which is combined with a willingness to sacrifice (some) profit. The idea of social enterprises has gain traction in last decade and it is now part of the curriculum of many leading business schools such as Harvard and Oxford.

How do we handle cases where a company sacrifices profits for a public benefit in line with the aims set by its articles of association?

Possibly the most fundamental challenge to traditional thinking stems from the incorporation of ideas like CSR and social enterprises into the legal framework. While previously the aim of a corporation was profit, new legal forms provide other options. Countries like the UK, Germany or the US have created new company forms within their laws. In these, public policy matters take a central role as the aim of the company. For example, shareholders of Public Benefit Company (available in Delaware-US since 2013) can hold the board accountable would the company pursue profit maximization over its public benefit mission.

As these new company forms take hold and a new, successful and innovative company like Kickstarter, make use of it, the competition community will need to ask itself: how do we handle cases where a company sacrifices profits for a public benefit in line with the aims set by its articles of association?

Three options seem available: first, orthodoxy prevails: issues of public policy are not considered in competition law. Second, an attempt is made to adjust the interpretation of the competition provisions—to the extent possible—to allow public policy to be considered. Third, fundamental re-design of competition law takes place to regulate the interaction between competition and public policy.

With the emergence of more companies like Kickstarter and initiatives like Facebook’s Aquila, it will be time to ask again: what message does competition law send to businesses? Can competition law cater for public benefits or should companies not even try to promote the public good?

Featured image credit: ‘101123-F-4684K-688′ by U.S. Department of Defense Current Photos. Public Domain via Flickr.

The post How Facebook’s Aquila initiative provides an impetus to rethink the boundaries in competition law appeared first on OUPblog.

November 27, 2016

Place of the Year spotlight: Tristan da Cunha, the most interesting place you’ve (n)ever heard of

I confess that when I saw Tristan da Cunha among the nominations for Place of the Year, I had no idea where it was, but once I got out my atlas, I was intrigued. Colloquially known as Tristan, the eight-mile-wide island is the most remote inhabited place in the world: it lies 1,200 miles east of the nearest inhabited island, Saint Helena, and a full 1,500 miles east of the nearest continental land, South Africa. Traveling west from the island, South America is another 2,090 miles away. (Fittingly, one of Tristan’s neighboring islands is named “Inaccessible Island.”) The island has no airport, so even now, the only way to reach the island is a seven-day journey by boat.

Tristan has a fascinating history–first sighted in 1506 by Portuguese explorer Tristão da Cunha, who named the island after himself, it was visited periodically by explorers and scientists until 1810, when the first permanent settler arrived from Salem, Massachusetts. Six years later, the UK annexed the island–primarily, it’s said, to keep the French from using it as a base to rescue Napoleon Bonaparte, who was imprisoned on the island of Saint Helena. Over the course of the past two centuries, the island’s population has continued to grow (except between 1961 and 1963, when everyone on the island was temporarily evacuated because of a volcanic eruption), and today more than 260 people live on Tristan.

Rockhopper penguin; Image by Nicolas Bschor, Public Domain via Pixabay.

Rockhopper penguin; Image by Nicolas Bschor, Public Domain via Pixabay.Because of its extreme isolation, the island is of interest to scholars of linguistics and genetics: Tristan’s present-day inhabitants speak a unique dialect of English and are believed to be descended from just fifteen ancestors, seven women and eight men. The island is also important for wildlife: Tristan is home to thirteen species of breeding seabirds and two species of resident land birds, including northern rockhopper penguins, Atlantic yellow-nosed albatrosses, sooty albatrosses, Atlantic petrels, great-winged petrels, soft-plumaged petrels, broad-billed prions, grey petrels, great shearwaters, sooty shearwaters, Tristan skuas, Antarctic terns, and brown noddies.

Tristan appears in the news periodically because of its distinction as the most remote inhabited place on earth–an op-ed recently suggested that Americans had better go all the way to Tristan, not just to Canada, if they’re trying to escape the effects of a Trump presidency–but in 2016 in particular it’s been in the news as the island sets out to become fully self-sufficient. A British architecture firm, Brock Carmichael Architects, won the contest to design a sustainable future for the Tristan da Cunha community–you can see their winning proposal for yourself.

Tristan’s experiment in sustainability could prove a model for communities around the world as the threat of climate change becomes ever more significant. If you think Tristan deserves a spot on the Place of the Year shortlist, vote for it in the poll below!

Featured image: “The island of Tristan da Cunha as seen from space.” by NASA, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. Place of the Year 2016

The post Place of the Year spotlight: Tristan da Cunha, the most interesting place you’ve (n)ever heard of appeared first on OUPblog.

Ten surprising facts about humanitarian intervention

After the end of the Cold War, humanitarian intervention – the use of military force to protect populations from humanitarian emergencies without the consent of the host state – emerged as one of the hottest topics of international relations.

As is usually the case in world politics, the actual practice of humanitarian intervention is more complex, than we might think. Sometimes, states traditionally thought to oppose intervention might support it, as with Pakistan over Bosnia and China over Somalia. The reverse is also sometimes true – in 2011 Germany opted not to vote in favour of NATO-led intervention in Libya, whilst decades earlier, Norway – a well known champion of humanitarianism – condemned Vietnam for its intervention which ended a genocide in Cambodia that had accounted for a quarter of that country’s population.

So, when we think about humanitarian intervention we need to be especially mindful of its ever-complex politics. These ten surprising facts might help.

1. Humanitarian intervention has a long history in both thought and practice. The question of whether it is legitimate to wage war to protect people in other countries from tyranny has a long history. The earliest Just War thinkers, St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas, argued that ending tyranny in other countries was a just cause for war. In the nineteenth century, European powers intervened in Greece to end Ottoman atrocities there.

2. Humanitarian intervention remains rare. We talk about humanitarian intervention much more frequently than we practice it. It is much more common for humanitarian emergencies to end because those that caused it achieved what they wanted (think of the decline of violence in Darfur after 2005 or the end of the Sri Lankan civil war in 2009), were defeated militarily by local actors (think of the end of the Rwandan genocide), or were deposed/persuaded to change course by internal dissent.

3. Not until 2011 did the UN Security Council authorize the use of force against a recognized government for humanitarian purposes. The UN Security Council is mandated by the UN Charter to authorize the use of force to maintain international peace and security. In the early 1990s, the Council identified a range of humanitarian issues as threats to the peace, but stopped short of authorizing force unless the recognized government granted consent (as in the cases of Haiti and Rwanda in 1994), or it judged that there was no government (as in Somalia). In other cases, the Council refused to authorize intervention because the relevant government was opposed to it (Kosovo), or insisted that it would only authorize intervention once consent was granted (as in the case of East Timor).

When we think about humanitarian intervention we need to be especially mindful of its ever-complex politics.

4. Humanitarian intervention is as likely to be conducted by non-Western states as it is by Western states. There is a widespread view – that humanitarian intervention is an action that Western countries carry out on non-Western, or post-colonial, countries. However, this is not the case for two reasons. Firstly, since the Second World War, as many humanitarian interventions have been conducted by non-Western countries than by those in the West. These include India’s intervention in Bangladesh, Vietnam’s intervention in Cambodia, Tanzania’s intervention in Uganda, and the ECOWAS interventions in Liberia and Sierra Leone. The US-led intervention in Somalia comprised a significant non-Western element acting under UN-command, and the NATO-led intervention in Libya in 2011 included states such as Jordan, Lebanon, and Qatar. Secondly, Western interventions have tended to focus on states in, or near, the West itself – for example Kosovo, Bosnia and Libya.

5. The African Union was the first international organization to codify a right of humanitarian intervention. And it remains the only organization in the world to do so. Article 4(h) of the African Union’s Constitutive Act gives the organization a right to intervene in the domestic affairs of its member states in situations involving genocide or mass atrocities. This right has not yet been exercised.

6. ECOWAS in West Africa was the first regional organization to launch a humanitarian intervention without the authorization of the UN Security Council. Nearly a decade before NATO got into the humanitarian intervention business, ECOWAS – led by Nigeria – intervened against Charles Taylor’s regime in Liberia without UN authorization. The Security Council later passed a resolution ‘welcoming’ the intervention.

7. The “United Nations Protection Force” did not have a mandate to protect civilians. In response to the wars of Yugoslavia’s dissolution, which began in 1991, the UN established a large peacekeeping mission known as UNPROFOR – the UN Protection Force. Yet, despite its name, UNPROFOR did not have a mandate to protect anyone other than its own forces. It was mandated to “deter attacks on safe areas” but not to use force to defend them – something that the people of Srebrenica discovered to their horror in 1995 when UN forces dissipated and left them to their fate. More than 7,700 men and boys were massacred by Bosnian Serb militia in the genocide that followed.

UN peacekeepers at Sarajevo airport in 1993, during the siege of Sarajevo by Mikhail Evstafiev. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

UN peacekeepers at Sarajevo airport in 1993, during the siege of Sarajevo by Mikhail Evstafiev. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons8. Done well, humanitarian intervention save lives. Calculating whether humanitarian intervention works, or not, is difficult because it requires counter-factual thinking. Research done independently by Taylor Seybolt and Matthew Krain, and using different data sets, suggests that when the international community does not intervene, or when outside powers intervene to support a warring party, a civil war or episodes of mass killing tends to last longer, and therefore leads to a higher death toll, than situations where intervention occurs. Virginia Page Fortna, meanwhile, has shown that long-term interventions involving peacekeeping also seem to reduce the likelihood of a war reigniting by a significant margin.

9. The Responsibility to Protect tries to reframe how the world responds to genocide and mass atrocities. The Responsibility to Protect, or R2P, focuses on the rights of populations to be protected from mass atrocities. It says that when states manifestly fail to protect their populations from mass atrocities, the international community should take action, working through the United Nations and employing powers given to the Security Council by the UN Charter in 1945. R2P does not give states or regional organizations a right to use force to protect populations without authorization by the UN.

10. The UN Security Council regularly refers to the Responsibility to Protect principle. Contrary to popular belief, R2P is now widely used by the UN Security Council. It has adopted more than 40 resolutions referring to the principle, including some that specifically authorize UN peacekeepers in South Sudan and Mali to help implement R2P. The Council has referred to R2P in relation to crises in, Democratic Republic of Congo, Somalia, Yemen, Libya, Central African Republic, South Sudan, Syria, Cote d’Ivoire, Liberia,, and Burundi.

Featured image credit: Reconciliation: The Peacekeeping Monument by Tony Webster. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The post Ten surprising facts about humanitarian intervention appeared first on OUPblog.

Jacob Tonson the elder, international spy and businessman

Few have heard of him today, but Jacob Tonson the Elder (1656?-1736) was undoubtedly one of the most important booksellers in the history of English literature. He numbered Addison, Behn, Congreve, Dryden, Echard, Oldmixon, Prior, Steele, and Vanbrugh among those canonical authors whom he published. His reputation was international, and the quality and range of his classical editions remained a benchmark throughout the eighteenth century. Having a reputation outside of England was an extremely rare thing for the time, and this was remarkably brought to light by a letter from Johann Rudolf Holzer (1678–1736).

Holzer was a politician and bibliophile of minor Swiss aristocracy, also a member of the Grand Council and a Provincial Governor of County Büren. He wrote, on 11 November 1730 (originally in French):

Every day such excellent books come from the press in England & you stand out to such advantage among your colleagues through the admirable editions for which the public is in your debt, that it is enough that a book comes from your press for one to be assured that it will be equally good and attractive […] Since I was born curious and our bookshops have not the wherewithal to satisfy my curiosity, I have [MS illegible], Sir, been unable to do better than to apply directly to you to satisfy my desires, persuading myself that a man who has made himself so useful to the public would certainly want to help me hunt out good books which are available in your country…

– Manuscript: British Library, Add. MSS., 28,275, fol. 266.

Dated from 1730 (after Tonson the elder had retired from publishing), this letter is evidently addressed to him, given the references to his earlier publications. Holzer may not even have known of the existence of Jacob Tonson the younger (1682-1735), Tonson’s business partner and heir, who by this time would have been the recipient of this letter.

Image Credit: ‘Jacob Tonson’ (1717) by Sir Godfrey Kneller, from the National Portrait Gallery. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image Credit: ‘Jacob Tonson’ (1717) by Sir Godfrey Kneller, from the National Portrait Gallery. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Despite the confusion over recipients, the letter is exceptional among Tonson’s correspondence, in that it was originally in French. This is particularly telling, as Tonson could speak and read French, having possibly been a spy in France, reporting on the ‘Plenipotentiary-Extraordinary Matthew Prior’ when he was ostensibly on ‘business in Europe’ on behalf of his press. The preliminaries for the Treaty of Utrecht (April 1713), which had ended the War of the Spanish Succession, had been negotiated by Prior. He was treated with considerable suspicion by the Whigs (a British political party), and, after the fall of the Tory ministry (1714), was arrested for treason. If Tonson had been a spy however, he has been dismissed by his most recent biographer (Ophelia Field) as ‘inept.’

Having said this, it is also of interest that the letter comes from such a high up European official. Tonson’s reputation in Great Britain was high, as can be seen from his association with men, including politicians and authors, who became members of the ‘Whig Kit Cat Club’ (an esteemed London literary and political group), which he founded. This example of his reputation in Europe was not without precedent however, as his edition of Dryden’s translation of The Works of Virgil (1697) was hotly anticipated by royalty and elites both in England, as well as on the continent. Addison even wrote to Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz that “this Edition of this Book … will probably be the noblest volume that ever came from the English Press.”

Cumulatively, the correspondence surrounding the Tonsons sheds substantial light on the editorial and publishing practices of the most important and successful publishing house at the time. They show the level of connections and discourse going on in Europe at the end of the eighteenth century – revealing a thoroughly cosmopolitan and intellectual elite. As such, letters like these offer an important and timely window on the ‘history of the book’ at a significant moment in English and European literary history.

Featured Image Credit: ‘Old Books’ by Tom Woodward. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Jacob Tonson the elder, international spy and businessman appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers