Oxford University Press's Blog, page 431

December 9, 2016

Marking Cassavetes’ birthday with a discussion on male discourse in his films

On the cusp of what would have been John Cassavetes‘ eighty-seventh birthday, it is not only possible to pause and imagine the work the man could have made throughout his sixties and seventies — think, for a moment, on Cassavetes as being alive and well, writing and directing films in a post-9/11 America — but also we can turn to his works for a lens onto a version of the world that, given the recent state of affairs on this planet, we could sorely use.

It is true that Cassavetes’ films present us with a complicated world, but it is a space in which myriad disconnections and complexities among characters lead them to not only struggle, fight, and argue but also to stop and deeply listen to each other and to themselves. Even if the characters that fill Cassavetes’ films are fraught with complications — even if they are prone to bad turns, and they frustrate each other (and themselves) as they grope for authority and control across chasms of unresolved behaviors and emotional double-backs — at the core of the characters Cassavetes constructed we also find depictions of a recurrent urge for understanding, a fumbling for compassion and empathy.

If one sets to one side, for a moment, the monumental attention that we must pay to Gena Rowlands’ career spent portraying powerful, tragic, fierce, and sometimes broken women throughout Cassavetes’ films — and any focus on Rowlands should not mistake Lelia Goldoni and other women who’ve portrayed the writer-director’s characters as being unimportant — in relation to these struggles and urges one can explore the films by giving attention to how men treat and talk to each other across the works. We can posit, in particular, as new kinds of presidents set new sorts of precedents for what men (in particular) and their friends can do — what they can say out loud without accountability — that in Cassavetes’ films he did many things but one thing he did many times throughout the twelve that he directed was to put his lens on a problematic, multivalent, and expansive male discourse. And from this we might learn a few things.

We find examples of the discourse in Husbands. The film is rich, despite its fractured and often deeply problematic bar-table and hotel-room aggressions — and often these are aggressions of men upon women, or the young upon the old, as we should note — with graveyard conversations about truth and lies, with crowded bathroom-stall fugues about the nature of mortality and the terror of aloneness, and with front-yard wind-ups on the topics of power in families and the authority we confer to our bosses and our paymasters and our spouses. All of this is absorbed and tolerated and finally erupts across the days we spend, through Cassavetes’ creation, in these men’s lives. They are, of course, men, these individuals. We cannot overlook their humanity, their empathetic cores pushing throughout the film’s imposed barriers, sharing weaknesses with one another — and sometimes with women, by film’s end — across time and two continents.

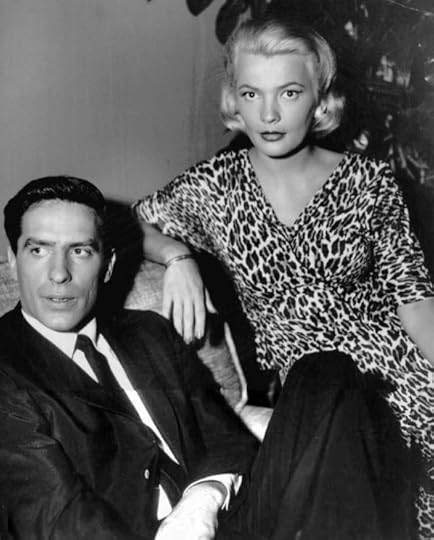

John Cassavetes and Gena Rowlands from the television program Johnny Staccato. Image: NBC, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

John Cassavetes and Gena Rowlands from the television program Johnny Staccato. Image: NBC, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.We can look also to the discourse between characters in Love Streams. In an early scene at a cabaret, a man dressed as a woman asks Robert Harmon (Cassavetes) if he is gay. The exchange is at once marked by both confidence and tremulousness. The asker is steady and perhaps gentle, allowing Robert to visibly grapple with the question, his face rippling with nervous energy, with surprise, and with the shy state of his apparent and immediate unsureness of what to say. No one is angry. No lines are drawn. No one is accused of being an ‘other’.

And we see this complicated world of men communicating about what they similarly do not yet know in the ramped-up days and nights of Shadows. Tony and friends race the city’s sidewalks, crying “forward!” to each other, play-fighting, and scooping on young women in diners. But then, momentarily surrounded by less familiar things in a museum sculpture garden, by a world of perceptions and depictions that strike some of them as, yes, too feminine or too elite (as Tom says), others among the men of Shadows resist these conclusions. We are struck when Dennis expresses his negative capabilities, shouting “I don’t know everything!” at Tom. For a moment, for the two, it is a pressing argument — the worth of looking at a modern sculpture, the value of acknowledging expressions not immediately decipherable, not intuitively recognized, and not categorizable by history and lessons handed down from the past.

Ray Carney, writing about Cassavetes’ work, ties something like that state of mind — ‘I don’t know everything’ — to larger themes, to Emersonian concepts of a fluid and volatile world in which what we think and feel is always in motion. To proclaim “I don’t know everything” is to invite disagreement but to demand recognition, to say, perhaps, along with Emerson (and Carney) that reality and knowledge are snapshots of experiences. In another vein, to say ‘I don’t know everything‘ is to court what Ilana Simons refers to as a wiser willingness for vulnerability — a willingness that is accessed by the “high modality” of kindness, as she puts it — and it is an argument for compassion and more thoughtfulness in the midst of moments otherwise suffused with confrontation.

In a time when we could be overwhelmed by confrontations, and when we are startled perhaps by choruses claiming disenfranchisement as a right to new authority — the authority to shun, ridicule, or squash fluidity and ambiguity — we come upon a fine way to mark Cassavetes’ birthday. We can turn to his films for a difficult, empathetic and multivalent look at how we — especially we men of this world — speak to and treat each other, and it is even finer to do so when we consider our words and deeds towards women. Pick one of the films and put it on, for these are the gifts Cassavetes has given us for our times.

Featured image credit: John Cassavetes with Gena Rowlands. Jon Rubin, CC BY-2.0 via flickr.

The post Marking Cassavetes’ birthday with a discussion on male discourse in his films appeared first on OUPblog.

Can Calvinism make you happy?

“Calvinism is a bleak, oppressive form of Christianity.” The sentiment is a common one. Finding quotations like this one from John Calvin’s letter to the Catholic Cardinal Sadoleto may seem to confirm it. “Whenever I descended into myself or turned my eyes to you, extreme terror seized me, which no expiations or satisfactions could cure.” Here, we surmise, is the rotten heart of Calvinism: the lost soul searching for some kind of mercy only finds endless self-examination compounded by a terrifying vision of a merciless Creator. Powerful pieces of literature like Herman Melville’s Moby Dick and John Updike’s In the Beauty of the Lilies have helped to perpetuate this negative image, inserting it firmly into the modern consciousness.

Though common, we might still take a moment to scrutinize the sentiment. Calvinism is robust Augustinianism. It is confessional in character. By that I mean it encourages looking back at the work of God in one’s life and marveling at that work; confessing that God has faithfully brought the believer through arduous difficulties up to the present day. Calvinism, then, takes this assurance into its assessment of the future. God has been faithful in the past, and will continue to be.

So Calvinism encourages self-examination. But it does more than that. To self-examination it adds God-examination. Calvinism happily embraces the sentiment expressed by Augustine: “I desire to know God and the soul. Nothing besides? Nothing whatsoever.” Calvin himself put it this way: “Nearly all the wisdom we possess,” he said, “consists of two parts: the knowledge of God and of ourselves.” Jonathan Edwards said the same thing in The Freedom of the Will. It is a Calvinist axiom.

This two-fold knowledge produces “extreme terror”; as Calvin said. This rather-startling fact requires some explanation. Calvin’s words (which may or may not be autobiographical) relate to an individual’s entrance into this knowledge and explain the effect this knowledge initially has on a person. Calvinism contends that true self-knowledge is profoundly humbling. Human beings are naturally arrogant. The first thing such knowledge impacts is their sense of well-being. This manifests itself in various ways depending on a person’s temperament, but a strong response of the kind mentioned by Calvin is not uncommon.

But this two-fold knowledge is, ultimately, the source of human happiness. So, Calvinism recognizes a movement from despair to contentment. The puritans, many of whom were Calvinists, used to write extensively about this. They described a good kind of sorrow arising from self-examination and distinguished it from harmful sorts of sorrow (which they often called melancholia). They produced what were called morphologies of conversion, plotting the steps through which a person would go on their way from sorrow over their sin to regret, despair, and misery, and then eventually to hope, faith, and joy. Marilynne Robinson speaking at the Covenant Fine Arts Center during an interview at the 2012 Festival of Faith and Writing at Calvin College by Christian Scott Heinen Bell. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Marilynne Robinson speaking at the Covenant Fine Arts Center during an interview at the 2012 Festival of Faith and Writing at Calvin College by Christian Scott Heinen Bell. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Later Calvinists also talked about this. Nineteenth-century preachers and theologians like Robert Murray M’Cheyne, W.G.T. Shedd and Robert Lewis Dabney, used to warn against excessive and incautious self-examination. It was, they said, dangerous and should be avoided. Instead, they counselled: “For every one look at you take at yourself, take ten looks at Christ,” so M’Cheyne used to tell his parishioners in Dundee, Scotland.

To Calvinists, human happiness does not take the form of uninterrupted euphoria; rather, it is quite different. Marilynne Robinson, the American Calvinist author who wrote Housekeeping, Gilead, and most-recently Lila speaks in a 2008 interview in The Paris Review about her life, reflecting at one point: “The ancients are right: the dear old human experience is a singular, difficult, shadowed, brilliant experience that does not resolve into being comfortable in the world.” Robinson continues in this vein throughout the interview, communicating the idea that a kind of deep contentment pervades her life alongside the trials, exhilaration, and boredom of this world, to which she does not feel particularly wedded. This sense of detachment from the world has nothing to do with her politics, income level, or choice of profession. It does not leave her distraught or anxiety-ridden. Rather, she knows a contentment that is felt on a plane below that of the humdrum of daily life.

We see this in Calvin as well. Commenting on Psalm 13, “How long, O Lord? Will you forget me forever?,” Calvin asserts that the Psalmist’s lament is not an expression of resignation or unbelief. Quite the opposite. It reveals an unshakeable hope which is confirmed by the rest of the Psalm. The believer laments, Calvin says, because she knows that her Father loves her and will hear her. Thus, the most despair-inducing, dehumanizing experiences she can go through cannot silence her.

So, to the Calvinist, it is not her religion that is bleak and oppressive; rather, life is. Life is hard. Human sinfulness is pervasive, intransigent, blinding. Calvinism just tries to take these facts seriously. It does, however, offer profound joy and a peace that is bottomless and enduring, with the proviso that “the ancients are right.”

Featured image credit: Interior of the Oude kerk in Amsterdam (south nave) by Emanuel de Witte (1617-1692). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Can Calvinism make you happy? appeared first on OUPblog.

December 8, 2016

Conversation starters in music therapy research

Conversation starters are questions and prompts intended to get people talking. Although often thought of in the context of a dinner party or professional meeting as a way to initiate dialogue with a stranger, conversation starters can also be thought of as ideas that stimulate discussions or impact you in a way that helps you grow both personally and professionally. Conversation starters are, at times, explicit in their intention and impact, but other times more subtle in their influence.

To start one such conversation, we invited members of the Editorial Boards from the Journal of Music Therapy and Music Therapy Perspectives to suggest articles they felt substantively contributed to our knowledge base but are not commonly cited or referenced. These articles reflect a small sample of “conversation starter” articles that help connect to our history while opening dialogues about current perspectives and practices.

As we consider this selection of articles, one consistent theme is a focus on establishing new vantage points in research and practice through the development of new methodology and self-inquiry. Below are board members’ reflections on some of these articles:

Regarding Amir (1990): I love the analysis adapted from Ferrara (1984) – an early example of phenomenological analysis in music therapy. Song composition is still such an important technique. With the newer techniques in neurological rehabilitation, it is nice to be reminded of the expressive needs of individuals recovering from traumatic brain injury (TBI).

Regarding Brunk & Coleman (2000): One reason I feel this article could be highlighted is that music therapists may not understand that the SEMTAP (Special Education Music Therapy Assessment Process) is, in fact, an assessment process vs. an assessment tool. The second reason is that the SEMTAP may be useful as an educational tool in instances where school personnel and others are not familiar with the value and “legitimate role” of music therapy in special education. This article explains the rationale for the development of the process, as well as background information on US federal special education laws.

Regarding Magee (1999): This article might be of value because it speaks to addressing patient’s emotional experiences in an age of functional outcomes, and also reflects an early article focused on rehab before the age of neuroscience research in this area – and finally, is an early example of a rather more complex approach to differential assessment, also developed by Wendy.

Regarding Marom (2008): In the hospice music therapy community, there can be a tendency to construct narratives around the beauty of hospice that belie the challenges of the clinical setting. This article touches on some of these challenges, such as clinicians’ potential countertransferences when clients do not readily express gratitude as explicitly or frequently in case studies. Marom finds a nice balance in capturing both the beauty and difficulty of hospice work.

‘“Healing America’s Heroes through the Power of the Arts” Marine Staff Sgt. Anthony Mannino plays guitar as he performs Music Therapy as part of his Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) treatment and recovery.’ 160301-D-FW736-012 by DoD News. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

‘“Healing America’s Heroes through the Power of the Arts” Marine Staff Sgt. Anthony Mannino plays guitar as he performs Music Therapy as part of his Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) treatment and recovery.’ 160301-D-FW736-012 by DoD News. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.Here, the authors begin conversations centered on topics not commonly addressed at the time, such as promoting self- and emotional expression in an individual recovering from a TBI or highlighting the emotional challenges involved in end-of-life care. These conversations are arguably still relevant today, both in terms of their topics and their ability to challenge us clinically. By fostering unique perspectives, these articles maintain the ability to invite music therapists into meaningful dialogues about clinical and research practices. Such dialogues are important avenues for moving the field forward, and can serve as a model for initiating and maintaining perspective-broadening professional discourses.

For example, one potential avenue for future discourse is in collaborating with healthcare professionals outside the music therapy field. How might the experiences of a hospice nurse further inform the difficulties in relationship building that Marom addresses? How might an occupational therapist or physical therapist’s perspectives inform the intersection of physical and emotional needs in individuals with TBI highlighted by Amir? Furthermore, such discourse is not unidirectional; music therapists can also serve to inform the practice of nurses, occupational therapists, and physical therapists too. It is through such collaboration that the unique clinical experiences afforded to clients served by these professions can be articulated and broadened.

In these ways, the conversations started by these music therapy researchers maintain viability, and may afford new means of initiating discourse moving forward.

The authors thank the Editorial Boards of the Journal of Music Therapy and Music Therapy Perspectives for their ideas and contributions.

Featured image credit: guitar by Derek Truningerz. CC0 Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post Conversation starters in music therapy research appeared first on OUPblog.

The little known history of Cuba’s intervention in Africa during the Cold War

When Nelson Mandela visited Havana in 1991, he declared: “We come here with a sense of the great debt that is owed the people of Cuba. What other country can point to a record of greater selflessness than Cuba has displayed in its relations to Africa?”

In all the reflections upon the death of Fidel Castro, his contribution to Africa has been neglected–because most Americans are unaware that Castro’s Cuba changed the course of southern African history. While Americans celebrated the peaceful transition of apartheid South Africa to majority rule and the long-delayed independence of Namibia, they had no idea that Cuba–Castro’s Cuba–played an essential role in these historic events.

During the Cold War, thousands of Cuban doctors, teachers, and construction workers went to Africa, while almost 30,000 Africans studied in Cuba on full scholarships funded by the Cuban government.

US officials tolerated Cuba’s humanitarian assistance, but not the dispatch of Cuban soldiers to Africa. There had been small Cuban covert operations in Africa in the 1960s in support of liberation movements, but the trickle became a flood in late 1975, engulfing Angola.

That Portuguese colony was slated for independence in November 1975, but civil war broke out several months earlier among the country’s three liberation movements–the MPLA, the FNLA, and UNITA. American officials were alarmed by the communist proclivities of the MPLA, but even they admitted that it “stood head and shoulders above the other two groups” which were led by corrupt men.

South African officials were also alarmed by the MPLA because of its implacable hostility to apartheid and promise to assist the liberation movements of southern Africa (UNITA and FNLA had proffered Pretoria their friendship).

By September 1975, the MPLA was winning the civil war. Therefore, Pretoria invaded Angola, encouraged by Washington. Secretary of State Kissinger hoped that success in Angola–defeating a pro-communist regime–would boost US prestige and his own reputation, pummeled by the fall of South Vietnam in April 1975.

The South Africans were on the verge of crushing the MPLA when 36,000 Cuban soldiers poured into Angola.

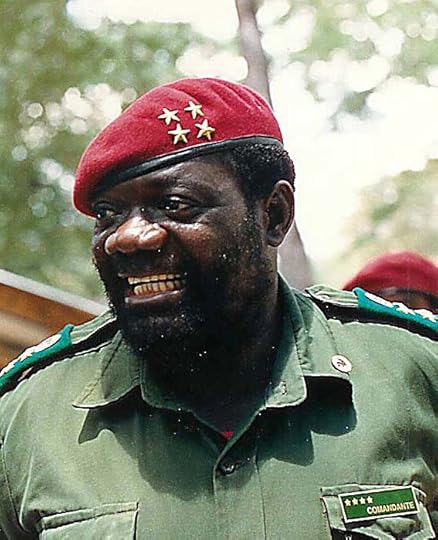

Jonas Savimbi, leader of the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), Eege Foto (1989) vum user ernmuhl. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Jonas Savimbi, leader of the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), Eege Foto (1989) vum user ernmuhl. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.The intervention, the CIA concluded years later, had been “a unilateral Cuban operation designed in great haste.” The Agency was correct: Castro dispatched the soldiers without consulting the Kremlin. Soviet General Secretary Brezhnev, who was focused on detente with the United States, opposed Castro’s policy, and refused–for two months–to help transport the Cuban troops.

Castro’s decision also derailed his secret negotiations with Washington to normalize relations. Had Castro been pursuing Cuba’s narrow self-interest, he would not have sent troops to Angola.

What, then, motivated Castro’s bold move? The answer is provided by Kissinger. Castro, he wrote in his memoirs, “was probably the most genuine revolutionary leader then in power.”

The victory of the Pretoria-Washington axis, the installation of a regime in Luanda beholden to the apartheid regime, would have tightened the grip of white domination over the people of Southern Africa. Castro sent his soldiers to join the struggle against apartheid, a fight he deemed “the most beautiful cause.”

The Cuban troops turned the tide of the war, pushing the South Africans back into neighboring Namibia, which Pretoria illegally occupied.

“Black Africa is riding the crest of a wave generated by the Cuban success in Angola,” exulted The World, South Africa’s major black newspaper. “Black Africa is tasting the heady wine of the possibility of realizing the dream of total liberation.”

In Angola, the Cuban-backed MPLA government welcomed guerrillas from Namibia, South Africa, and Rhodesia. It became a tripartite effort: the Cubans provided most of the instructors, the Soviets the weapons, and the Angolans the land.

For apartheid South Africa it was a deadly threat. Therefore, for over a decade, Pretoria continued to battle the MPLA, attempting to install in its place the leader of UNITA, Jonas Savimbi, a man whom the British ambassador in Luanda labeled “a monster.”

The Angolan army was weak. Even the CIA conceded that the Cuban troops were “necessary to preserve Angolan independence,” but for the United States–under Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan–the Cubans were an affront.

Reagan joined Pretoria in supporting Savimbi. He tightened the embargo against Cuba and demanded that the Cuban soldiers leave Angola. Castro refused. It was a stalemate.

Until 1988. It was the Iran-Contra scandal that broke the logjam. Before that imbroglio weakened Reagan, the Cubans had feared a US attack on their island. But in its wake, Castro decided it would be safe to send Cuba’s best planes, pilots, anti-aircraft systems and tanks to Angola to push the South Africans out of the country, once and for all. “We’ll manage without underpants in Cuba if we have to,” Raul Castro told a Soviet general. “We will send everything to Angola.”

Once again, Fidel had defied the Soviet Union. Gorbachev, bent on detente with the United States, opposed escalation in Angola. “The news of Cuba’s decision … was for us, I say it bluntly, a real surprise,” he told Castro. “I find it hard to understand how such decision could be taken without us.”

In early 1988 the Cuban troops gained the upper hand in Angola. They were strong enough to cross the Namibian border, seize South African bases, “and drive South African forces further south,” the Pentagon noted. The situation was “one of the most serious that has ever confronted South Africa,” the country’s president lamented.

Pretoria gave up. In December 1988, it agreed to Castro’s demands: allow UN supervised elections in Namibia and terminate aid to Savimbi. Pretoria’s capitulation reverberated beyond Angola and Namibia.

In Mandela’s words, the Cuban victory over the South African army “destroyed the myth of the invincibility of the white oppressor … [and] inspired the fighting masses of South Africa. [It] was the turning point for the liberation of our continent–and of my people–from the scourge of apartheid.”

Featured Image credit: guards at the tomb of José Marti in Santiago, Cuba by PRA. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The little known history of Cuba’s intervention in Africa during the Cold War appeared first on OUPblog.

Celebrity and politics before Trump

Donald Trump’s surprising victory in the 2016 US Presidential election demonstrated that celebrity is now a political force to be reckoned with. Famous actors such as Ronald Reagan or Arnold Schwarzenegger have held high office in the past in the US, and and Indian film stars such as Jayalalithaa Jayaram or Maruthur Gopalan Ramachandran (popularly known as MGR) translated their fame into successful political careers, but Trump’s victory reveals the power of celebrity name recognition as a force for political mobilization, and has highlighted the theatrical aspects of political performance in our heavily mediated society. Trump’s success has already encouraged other celebrities such as Kanye West and Dwayne ‘The Rock’ Johnson to consider making their own presidential bids in the 2020 election. Pundits such as Michael Moore have suggested that the Democratic Party should support a celebrity candidate such as Tom Hanks or Oprah Winfrey as their standard bearer in the future if it wants to find its way back to electoral success.

It would seem that this mix of celebrity culture and politics is a relatively new phenomenon, and indeed celebrity itself is often thought to be something distinctly modern. It’s true that the word ‘celebrity’ didn’t refer to a particular person until around the mid-nineteenth century, and ‘celebrity’ didn’t refer to the experience of fame or popular renown until the later eighteenth century. The French historian Antoine Lilti has referred to celebrity as “a radically new form of renown.” It’s easy to understand why one might think that celebrity has only gradually become a politically potent currency.

But there were celebrities long before that particular word identified them as such, and there was a time when politics made celebrities rather than the other way around. Before the later eighteenth century, the word ‘celebrity’ tended to refer to ceremony. Celebrity was a way of describing the pomp and circumstance that traditionally accompanied important public rituals such as weddings, funerals, and royal processions. Celebrity was intricately linked to the magic, charm, and charisma associated with the church and royalty, and this meant that celebrity was inherently political – contemporary fame was produced by the majesty of royal or spiritual power, or preferably both. It’s important to understand this connection between premodern, ceremonial forms of fame, and their modern successors known as celebrities.

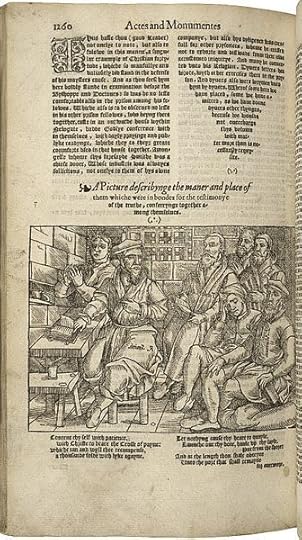

Modern celebrity is in many ways a product of the new publics created by the early modern printing revolution. The mass production of words and images enabled by the printing press allowed people to learn about, and recognize, contemporary figures in hitherto unprecedented ways. This early modern media revolution allowed for kings, queens, and religious leaders such as Martin Luther (1483-1546) or the English Protestant martyrs memorialized by John Foxe (1516/17–1587) to become famous with greater speed and extent than had been possible.

A page from the first edition of John Foxe’s Actes and Monuments, in 1563 by Folger Shakespeare Library Digital Image Collection. CC-BY-SA-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

A page from the first edition of John Foxe’s Actes and Monuments, in 1563 by Folger Shakespeare Library Digital Image Collection. CC-BY-SA-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.The political turmoils of early modern England helped to create new celebrities. The most effective means of turning ordinary people into celebrities was through persecution, and particularly through the spectacle of judicial process. Political trials were full-scale media events in early modern England. John Foxe’s Acts and Monuments (1563) cultivated an appetite amongst early modern readers for the stories of the tribulations of otherwise ordinary people who were persecuted for their religious beliefs. In the seventeenth century, the stories of people who were prosecuted for political transgressions also garnered a large readership. By the early eighteenth century, these stories would be collected into volumes called State Trials (1719) and they would be reprinted, augmented, and further anthologized right through the nineteenth century. Works such as the State Trials and Foxe’s Acts and Monuments served to preserve for posterity the fame of individuals who had gained notoriety through their persecution.

In some cases, judicial persecution could create a political celebrity. The Tory clergyman, Dr. Henry Sacheverell, was impeached in Parliament for high crimes and misdemeanors in 1710 in response to some intemperate and fiery words he had preached at St. Paul’s Cathedral. Although Sacheverell was found guilty, his punishment was mercifully light – he was simply banned from preaching for three years and his sermon was ordered to be burned – and so he emerged from the experience as a celebrity and a hero for the Tory cause. Sacheverell became perhaps the best known person in England with the exception of the reigning monarch, Queen Anne, and he even took to imitating monarchical practices such as going on a celebrated progress across the country. Religious and political divisions helped to construct a new celebrity.

Perhaps it is too easy to forget that politics has always been at the heart of celebrity. While some historians of celebrity have been inclined to draw a direct line between the London stage of the eighteenth century through to modern-day Hollywood, it is better to remember that the charisma that is at the heart of celebrity has always been as much about power as well as entertainment.

During his presidency, Barack Obama has sometimes been referred to as ‘the first celebrity president’ in which he remodeled the presidency in ways that were more suited to twenty-first century forms of communication, such as social media, and his careful construction of a public persona that resembled likeable film stars more so than aloof policy wonks. While the juxtaposition of the presentation of personality for public entertainment as well as for political leadership has sometimes seemed awkward, theatricality and politics have always been closely related. The election of a former reality TV star to the office of President of the United States of America is less surprising than it might otherwise seem if we recognize the importance of attention grabbing and performance skills are to a highly mediated political culture such as our own.

Featured image credit: Donald Trump holds a rally in Newtown, PA, October 2016 by Michael Candelori. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Celebrity and politics before Trump appeared first on OUPblog.

2016’s most popular baby names and their meanings

Every year, there is much speculation in the UK as to which names are rising or falling in popularity. Figures published by the BBC for the most popular baby names of 2015 had Oliver and Amelia as the two favourites. So far, 2016 has thrown up some surprise results with Isla currently top for girls (up four places from last year), and Alfie (a new entry) making it to the boys’ top spot. But with all this fierce competition, do you know the surprising origins of some of our most beloved names? With 2016 almost at an end, we’ve delved into the epithetical etymology of the girls’ and boys’ baby names. Has your name made the list?

Most popular girls’ names in the UK for 2016

Isla (up from 4th place)

Pronounced ‘eye-la’, this name originated in Scotland sometime in the twentieth century. It was relatively uncommon at first, but is now used widely in Britain. As you may have guessed, it derives from ‘Islay’ — the southernmost island of the Inner Hebrides of Scotland, known as ‘The Queen of the Hebrides’.

Amelia (down from 1st place)

Amelia is a blend of two medieval names, Emilia (of Latin origin) and the Latinized Germanic Amalia. It was used frequently during the seventeenth century, but only became really popular in in the eighteenth century, after both George II and George III (of the German House of Hanover) named their daughters Amelia.

Ava (up from 5th place)

‘What’s in a name?’ by Jack Dorsey, CC by 2.0, via Flickr.

‘What’s in a name?’ by Jack Dorsey, CC by 2.0, via Flickr.The meaning of Ava is contested, though it is thought to be a common form of various Germanic names, all containing the crucial element, av. There is little evidence of its use from the middle-ages through to the twentieth century – and it only rose in popularity recently. This is most likely due to the fame of the 1950s film actress Ava Gardner.

Freya (new entry)

Freya is a name of Old Norse origin. Freya (Alternatively spelt Freyja or Fröja) was a goddess associated with love, beauty and fertility in Scandinavian mythology. She owned the necklace Brisingamen, rode a chariot pulled by cats, had a cloak of falcon feathers, and always kept a boar by her side. The name has long been traditional in Shetland, and came to wider prominence in the 1990s.

Evie (new entry)

Evie is the pet form of Eve, Eva, or Evelyn — although it is often also used independently. It’s most common form Eve is the name of the first woman in the Bible, which derived from the Latin name Eva — which in turn originated from the Hebrew name Havva, thought to mean ‘living’ or ‘animal’. In line with this etymology, Eve is described in the Bible as ‘the mother of all living’ (Genesis 3:20).

Most popular boy’s names in the UK for 2016

Alfie (new entry)

The shortened form of Alfred, Alfie comes from a combination of two Old English names. These are ælf meaing ‘elf, supernatural being’ + ræd meaning ‘counsel’. A fantastic example of Old English folklore, it was extremely popular during the time of Alfred the Great (849–899), and spread all over Europe. It was less popular in the mid-twentieth century, but has recently seen a massive return to favour.

Oscar (up from 10th place)

Image Credit: ‘Brothers, Family, Siblings’ by sathiantripodi, CC0 Public Domain, via Pixabay.

Image Credit: ‘Brothers, Family, Siblings’ by sathiantripodi, CC0 Public Domain, via Pixabay.Oscar is an Old Irish name, used in the Fenian Cycle (ancient Irish tales and ballads describing the deeds of Finn MacCumhaill) – for the grandson of the protagonist. Today, Oscar is one of the few traditional Celtic names popular in Scandinavia as well as the rest of Europe. Its travels were helped by the fame of Oscar Wilde and the eponymous film industry awards.

Teddy (new entry)

Teddy is generally used as the nickname for Theodore and Edward, though also given as a name in its own right. Teddy bears themselves were named after the American president Theodore Roosevelt — largely inspiring its subsequent use. Teddy is one of the few top-ten names to be gender-neutral, as it can also be used as a pet form of Edwina.

Harry (down from 3rd place)

Although an ancient name in its own right, Harry derives from the even older name of Henry. It came to prominence in England in the Middle Ages, and has been used by dramatists and novelists across the ages – most recently at the protagonist of J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series. It was the nickname of all eight King Henrys, as well as a common form of Harold and Harrison.

Jack (down from 2nd place)

Like Harry, Teddy, and Alfie – Jack is also a pet form of an older name. Originally the nickname for John, it came from the Middle English Jankin, which in turn derived from from Jan (a contracted form of Jehan ‘John’) + the diminutive suffix -kin. It was so common in the Middle Ages that ‘jack’ became a generic term for a man.

Featured Image Credit: ‘Baby, Girl’ by regina_zulauf, CCO Public Domain, via Pixabay.

The post appeared first on OUPblog.

December 7, 2016

The people of the mist

The true people of the mist are not the tribesman of Haggard’s celebrated novel but students of etymology. They spend their whole lives in the mist (or in the fog) and have little hope to see the sun. However, after saying goodbye to fogs and foxes, I promised a post on mist. A good deal about this word is known and will be found in all dependable reference works, but a few details may be of interest to the readers of our blog.

Our oldest etymologists had no clue to the origin of this mysterious noun. Some Greek words were cited in the hope of finding a reliable cognate. At least one such word exists, but it did not occur to anybody three hundred years ago. Minsheu wondered whether mist is connected with Latin mixtus “mixed,” because mist, as he pointed out, is a combination of vapors. Moist looked promising, but English moist is from Old French, from Latin, where its traces are partly lost, though it could go back to the root seen in Latin mūcus “mucus.” In an English dictionary, a close neighbor of mūcus is the unrelated muck, perhaps of Scandinavian origin, though Old English also had moc. Old Icelandic mjúkr meant “dung,” akin to Gothic mūk– “gentle,” or rather “soft.” Engl. meek is a borrowing of Scandinavian mjúkr. From an etymological point of view, muck was “soft stuff.” None of those m-words is cognate with mist, but words for “manure” will accompany our search for some more time. It is only regrettable that the etymology of dung is unclear, despite the fact that it is a word widely represented in Germanic.

Surprisingly, the great Franciscus Junius, a renowned etymologist of old, missed Gothic maihstus (pronounced as mehstus) “dung heap”—surprisingly, because he was the first European with a thorough knowledge of that ancient Germanic language. This “mehstus” is the product of a Gothic sound change: i became e before h; consequently, the original form was mihstus. In Old English, h was lost, and the word became mīstus. Ī in it is long because it swallowed the following consonant (so-called compensatory lengthening), but in later Old English, vowels were shortened before two consonants, so that mīst became mist. (Those who begin to study historical phonetics tend to conclude that most changes are chaotic and senseless: sounds become long or voiced, in order to lose length and voice and a few centuries later to get them back. Likewise, diphthongs become monophthongs, and in the next chapter it is stated that the game was not worth the candle because the monophthongs turned into diphthongs. Only after the student has mastered the seemingly erratic moves of the kaleidoscope, can the mist disappear and at least some logic emerge, but this journey is for the patient. Those in a hurry need not apply.)

Compensatory lengthening at its most graphic.

Compensatory lengthening at its most graphic.Mist sounds and means nearly the same in several other Germanic languages, except that German Mist means “dung, manure; crap.” It is also used as an exclamation corresponding to English “shit!” but is a bit more polite. One can see that, with regard to mist, German and Gothic go together, and their meaning appears to be the oldest: the reference must have been to things unclean, to refuse, or something like it. This impression is reinforced by the rather obvious cognates of mist outside Germanic, all referring to darkness, clouds, and haze.” Gothic, as noted, had maihstus (that is, mehstus, from mihstus). Once its form must have been mig-stus, with g devoiced before st. The root turns out to be the same as in Slavic mig-la “darkness.” Even in Germanic some related mig– words exist, for instance, Dutch miggeln “to drizzle.” Some verbs meaning “to urinate,” as in Old Engl. mīgan, Old Icelandic míga, Latin mejere, and perhaps Latin mingere, belong here too.

From mist there is only one step to Engl. mixen (now archaic and dialectal) “dunghill”. Once again we are on the formerly explored unclean Gothic-German territory. Mist, it has been suggested, denoted a dirty, almost black cloud (see above). But urine is a liquid, so that, not quite improbably, the initial meaning was “wetness,” and, if so, we have an ancient synonym of fog (see the post of November 9, in which fog “mist” and “grass” are derived from the idea of wetness). The emergence of the root mig– remains a puzzle: what is the association between mig– and darkness or wetness? No sound symbolism, no sound imitation. Be that as it may, more ominous than the darkest cloud, is mistletoe, the name of the plant that killed the shining Scandinavian god Baldr.

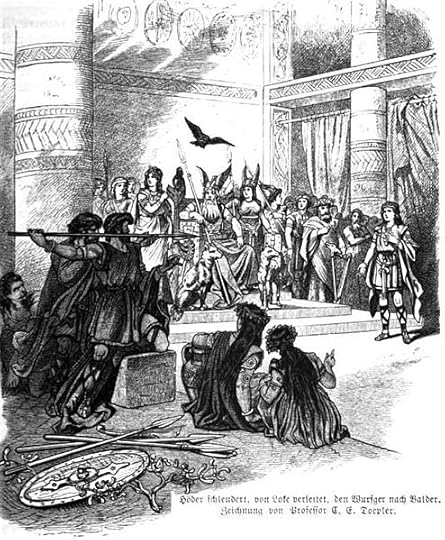

In the Scandinavian myth, the mistletoe, allegedly growing like a tree, turned into a spear and killed Baldr.

In the Scandinavian myth, the mistletoe, allegedly growing like a tree, turned into a spear and killed Baldr.Those who told this myth had hardly ever seen the mistletoe, for that plant could never have turned into a spear. (According to the story, a blind god listened to evil advice, uprooted the mistletoe (!), hurled it at Baldr, and the plant turned into a deadly spear in midair.) It was the name that seems to have stood behind the myth. Mistilteinn probably came to Norway and later to Iceland from England, because all the continental Scandinavian languages have an entirely different word for the mistletoe. The Old English form was misteltān. Tān is “toe,” that is, “offshoot.” The first element is problematic, but its origin is of no great consequence to us, for here folk etymology (proximity to mist-, real or imagined) played a decisive role. When the Norwegians and especially Icelanders heard mistel, they thought of their mistr “mist.” In Iceland, the hero of a typical fairy tale does not lose himself in the forest before some fatal meeting: a curtain of fog, not a thicket, separates the realm of human beings from the world of dangerous supernatural creatures. The valkyrie’s name Mistr shows that for Icelanders, as well as for Norwegians, mist was associated with death. (Valkyries were the female servants of Odin, the god of death: they invited fallen warriors to join him in Valhalla.) Later, the sword name Mistilteinn was coined, and another version of the myth arose: allegedly, Baldr was killed with that sword.

Could anyone who saw the mistletoe think of its becoming a spear?

Could anyone who saw the mistletoe think of its becoming a spear?This explains why the mistletoe, an evergreen plant, which, like other evergreens, symbolizes and promises fertility, acquired such an unusual role. People decorate their homes with holly and mistletoe for Christmas, and kissing under the mistletoe is a custom, transparent enough. There is a memorable description of that custom in Dickens’s Pickwick Papers, Chapter 28. The myth in the form known in medieval Iceland could arise only in Scandinavia. It would have had no chance to be told in the Celtic-speaking world (where the mistletoe was revered) or in England (the English learned the stories of this plant from the Celts).

Fog and mist are not the only Germanic words for this natural phenomenon. Icelandic þoka means the same (þ has the value of Engl. th in third). Norwegian tåke and Danish tåge are obviously related to it (they are reflexes of the same etymon). In Swedish, a cognate of þoka is known only from dialects (Swedes call mist dimma; its connection with Engl. dim needs no proof). Þoka probably also meant “dark,” but its origin is debatable. I always say that words live up to their etymology: opaque words designate things lacking transparency. But we are out of the dark—indeed, not because we have shed light on the history of so many obscure words but because we have left the story of them behind.

Images: (1) “American Alligator eating Blue Crab 2” by Gareth Rasberry, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. (2) “Baldr’s death” by Carl Emil Doepler, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. (3 and featured image) Mistletoe by Egle P, Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post The people of the mist appeared first on OUPblog.

Copyedits, caffeine, and cephalopods: A Q&A with Matthew Marusak

From time to time, we try to give you a glimpse into our offices around the globe. We sat down with Production Editor Matthew Marusak to talk us through the book production process, his favourite word, and what a day in the life is like for an OUP employee in Cary, North Carolina.

When did you start working at OUP?

I started in May 2011 as a temp but was hired full-time shortly thereafter.

What is your typical day like at OUP?

I am responsible for coordinating the production process—from copyediting to printing—on fifteen very different journals with very different needs. I am the main point of contact for my suppliers, editors, and authors, so there is a great deal of e-mail exchange and occasional phone calls. I also do a good deal of training—both formal and impromptu—with my colleagues, particularly new starters. A meeting-free day is a blessing!

What is the strangest thing currently on or in your desk?

A fellow cephalopod-adoring colleague lent me the book The Soul of an Octopus: A Surprising Exploration into the Wonder of Consciousness. I should probably think about reading or returning it at this point. I also have an unopened bottle of Pibb Xtra that I’m saving for an emergency pick-me-up.

Matthew Marusak. Used with permission from author.

Matthew Marusak. Used with permission from author.What’s the first thing you do when you get to work in the morning?

I turn on my computer and get all my systems up and running before diving into the sea of e-mails.

What’s your favourite book?

I became obsessed with Virginia Woolf after seeing the film The Hours. It is difficult to choose a favorite between Mrs. Dalloway and To the Lighthouse, though I think the former has a slight edge. The NSFW choice is Crash by J. G. Ballard.

What is the most exciting project you have been part of while working at OUP?

It is difficult to pinpoint one thing. Every day presents new challenges and new opportunities for growth and development. I recently gave a presentation at Oxford Journals Day, which was exciting and terrifying in equal measure. It’s the one time a year I get to be an extrovert—don’t get any ideas!

What is your favourite word?

Lavish

What’s the most enjoyable part of your day?

Arriving home after a long day and frolicking with my preposterous feline companions (Elvis and Leo) before collapsing on the sofa to watch a film or some cooking competition show I’ve recorded.

If you were stranded on a desert island, what three items would you take with you?

Why would I choose to be stranded on a desert island? And, if I did, why would I take only three things? It seems like a gross miscalculation. And how long am I planning to be stranded? A day? Two days? I seriously doubt I’d survive longer than a week. That being said, I would need, at the very least, a case of good Pinot Noir, my autographed copy of Liz Phair’s Exile in Guyville (and pray there’s a working CD player somewhere on this island), and a bottle of Chanel N°5—because why not go out in style?

What’s the most surprising thing you’ve found about working at OUP?

I don’t know if “surprising” is the right word, but I’m consistently amazed by our dedicated and hard-working staff. People seem legitimately passionate about the work they do, which I think is increasingly hard to find these days. In my five years at OUP, I have worked with so many intelligent, caring, and committed people who are all working toward the same goal. We greet challenges and difficulties with grace and dignity, and we support one another in ways I have never experienced in any other company.

Featured Image Credit: book publishing hobbies by Patrick Tomasso. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post Copyedits, caffeine, and cephalopods: A Q&A with Matthew Marusak appeared first on OUPblog.

What to expect from Trumponomics

Candidate Donald Trump’s policy proposals ranged from the bizarre to the truly frightening.

Remember his “secret plan” to defeat ISIS? Turns out it consists of working with our Middle Eastern allies and tightening border security. What about his rhetorical (we hope) question about why the US can’t use nuclear weapons? That and other foreign policy pronouncements may explain why a group of fifty senior Republican defense and foreign policy experts signed a letter repudiating his candidacy.

Candidate Trump’s economic policy pronouncements were similarly worrisome. Candidate Trump suggested renegotiating (i.e., defaulting on) interest payments on the federal government’s debt and initiating trade wars with China and Mexico. And non-partisan experts argued that adopting the candidate’s tax plan would result in an explosion of the government’s debt.

Now that the election is over, a number of pundits predict that Candidate Trump’s extremism will give way to a more moderate, pragmatic President Trump. We can only hope.

At the time of this writing, neither detailed proposals nor the names of personnel who will fill the top economic jobs (aside from Treasury secretary Steven Mnuchin) are available, so forecasting the Trump Administration’s priorities—and their chances of success—is speculative at best. Nonetheless, here is a first pass.

Personal taxes

Candidate Trump proposed turning the current seven income tax brackets into three and reducing the rate paid by those in the top bracket, giving a tax cut to those earning more than $413,350 (see table). His proposed repeal of the estate tax, which currently affects less than 1% of all estates, would similarly benefit the most affluent families. The exact effects of these proposals on lower income families is less clear. The Trump campaign argues that a higher child care allowance and standard deduction will reduce the tax burden on low-income families. Other experts argue that by eliminating personal exemptions and repealing the head of household filing status, Trump’s plan will cause lower-income, single parent households to face an increased tax burden. Given Republican majorities in both houses of Congress, the repeal of the estate tax seems almost certain. Similarly, some lowering of top tax rates is likely.

Comparison between current tax rates and Trump plan

Tax rate

Current policy

Tax rate

Trump proposal

10%

Up to $18,550

12%

Up to $75,000

15%

$18,551 to $75,300

25%

$75,001 to $225,000

25%

$75,301 to $151,900

33%

$225,001 or more

28%

$151,901 to $231,450

33%

$231,451 to $413,350

35%

$413,351 to $466,950

39.60%

$466,951 or more

Infrastructure investment

According to the Tax Foundation, US corporations are subject to a top marginal tax rate of 38.92%, the third highest in the world. This encourages US firms to undertake all sorts of costly tax-avoidance strategies. One such tactic is “corporate inversion,” which occurs when a US firm is “taken over” by a smaller firm based in a country with lower corporate taxes and changes its tax home to the new jurisdiction. Hence, a US company facing a 38% US corporate tax might be “acquired” by an Irish company paying 12.5%. The Treasury has taken aim at these corporate inversions, but both Democrats and Republicans recognize that some sort of corporate tax reform (including a lower corporate tax rate) will be necessary to stem this tide. It seems likely that President Trump and the Republicans will push through a lower corporate tax rate. This too, will likely benefit wealthier Americans.

NAFTA Initialing Ceremony, October 1992 by George Bush presidential library and museum Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

NAFTA Initialing Ceremony, October 1992 by George Bush presidential library and museum Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Corporate taxes

Candidate Trump proposed increased government spending to repair our crumbling infrastructure. This is one proposal which may garner more support from Democrats than Republicans. Larry Summers, a former Treasury secretary presidential economic advisor, argues forcefully that such investment will make the country more productive, keep the burden of repairs from falling entirely on future generations, and provide the economy with a much needed fiscal stimulus. The main obstacle to enacting infrastructure spending will be Congressional Republicans, who are far from sympathetic. It is unclear how this conflict will play out.

Trade

A signature theme of Trump’s campaign was a proposed about-face in US trade policy. Candidate Trump argued that lowering trade barriers—a policy pursued by Republican and Democratic administrations for decades—has harmed the US manufacturing sector and cost American jobs. He said that the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) between Canada, Mexico, and the United States was the worst trade deal ever signed by the United States, and that it would have to be renegotiated or scrapped entirely. He promised to sink the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade deal (according to the Senate Republican leadership after the election, the TPP is now officially sunk) and to slap punitive tariffs on China and Mexico for trade practices that hurt American workers. The election results, particularly those in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Wisconsin, and Michigan, suggest that this argument did not fall on deaf ears.

What can President Trump do about trade? According to the Peterson Institute for International Economics, the president has the authority to take the United States out of NAFTA with six months’ notice. The threat to withdraw may already have produced some results. Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto signaled that he is open to “modernizing” NAFTA, suggesting that he is concerned about getting into a trade war with the United States. Canadian manufacturers have made it clear to their government that retaining access to the US market is a priority and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said he was “more than happy to talk about NAFTA.” It is, however, unclear exactly what concessions President Trump will demand and what concessions Canada and Mexico will be willing to give to avoid a trade war. Given the integration of supply chains across borders (e.g., many of the components of US-made automobiles are manufactured in Mexico), tearing up NAFTA may be very costly for US manufacturers.

Starting a trade war with China could easily backfire. The Chinese are likely to retaliate—as they have done in the past—against US sanctions. US companies operating in China—and there are quite a few that have made big bets there—could suffer from such tit-for-tat behavior. And, of course, China holds more than a $1 trillion of US government debt. A decision to start selling these holdings could roil the value of the dollar on financial markets and have serious repercussions for domestic and world stock and bond markets.

Perhaps the most unsettling part of Candidate Trump’s trade policy is that it is not going to revitalize American manufacturing. The jobs Trump believes “made America great” are not going to come back—at least in enough quantities to make a difference—unless trade barriers are so high that they bankrupt American business and consumers. There are things we can—and should—do for the many Americans who have been harmed by trade. Starting a trade war is not one of them.

Featured image credit: Taxes by pictures of money. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post What to expect from Trumponomics appeared first on OUPblog.

WWI propaganda in America

By 1917, Americans increasingly became more concerned about the possible implications that would come with a German victory. With at-home values in mind, the United States presented propaganda to use as a call to action. For the first time ever, whole nations were involved in combat, and not merely professional armies. This medium was used to dehumanize the enemy and portray the growing hatred against them.

In order to convince the masses that there was a just cause behind the brutal and bloody conflict, propaganda was utilized, not only a means to gain cooperation from countries that remained neutral, but also to increase support of current allies, maintain people at home informed, and influence their opinion about the war. The following slideshow portrays images of WWI propaganda used in the United States:

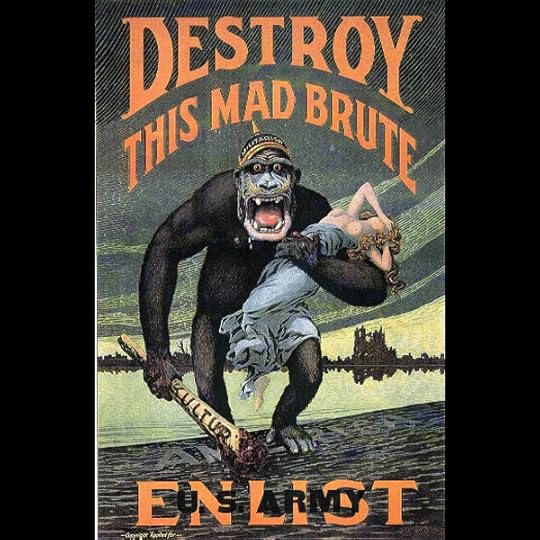

"Destroy this mad brute"

During WWI, American propaganda depicted Germans as barbaric and violent-natured.

(Image: “Destroy This Mad Brute propaganda poster” by US government related, H.R. Hopps 1917. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons).

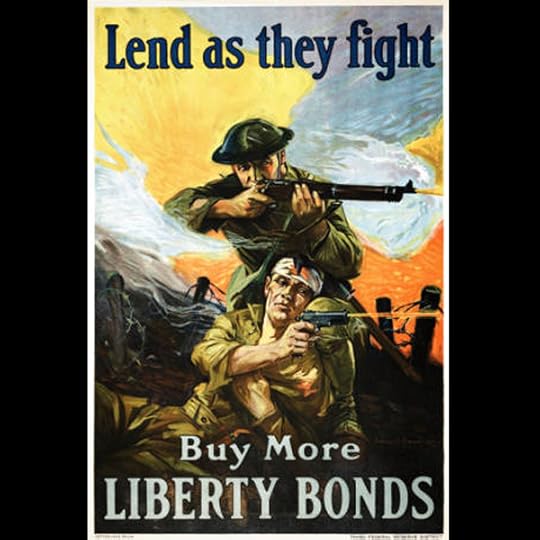

"Lend as they fight"

Sidney Riesenberg, a professional illustrator commissioned to create US Navy and Liberty Bond propaganda posters, is regarded as one of the greatest illustrators of the World War I era.

(Image: “Liberty Bond – 9” by Riesenberg, Sidney H. Public domain via Wikimedia Common).

"I own a liberty bond"

The “I own a liberty bond” buttons were distributed as a means to encourage American patriotism on the home front during WWI.

(Image: “Liberty Bond – 1” by Edwards & Deutsch Litho. Co. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons).

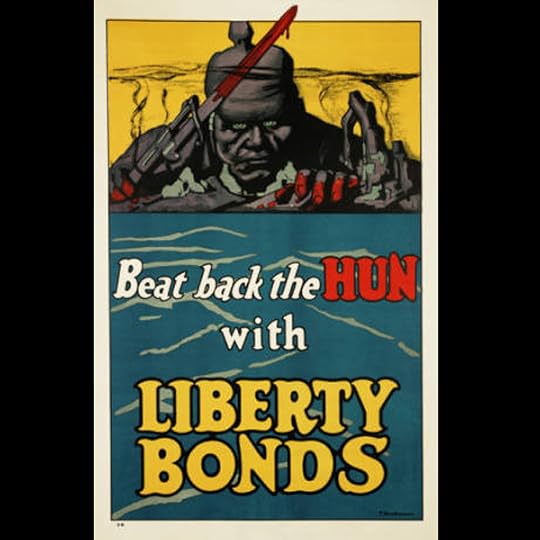

"Beat back the Hun with Liberty Bonds"

Liberty Bonds were promoted to Americans as a patriotic duty, and were first issued in 1917.

(Image: “German soldier with bloody bayonet and fingers” by Strothmann, F. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons).

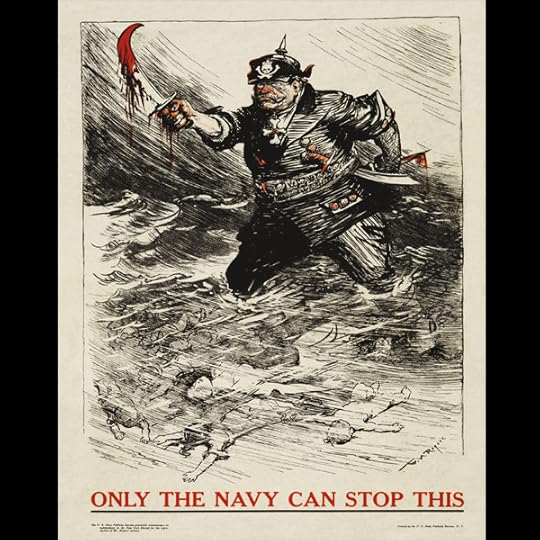

"Only the navy can stop this"

The negative imagery used to dehumanize the German military led to the persecution of German Americans during the war.

(Image: Image credit: “William Allen Rogers – Only the Navy Can Stop This” by William Allen Rogers for the US Navy Bureau, NY. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons).

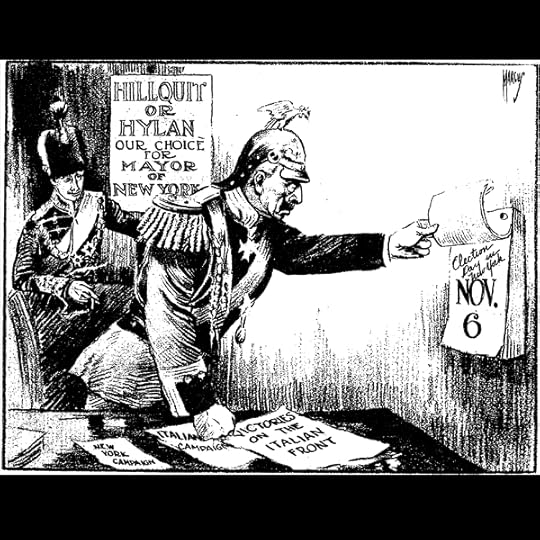

"Anymore victories, Papa?"

American animosity towards Germany was used as a means to attack political opponents during the war. The above cartoon implies that enemy forces favor New York City mayoral candidates Morris Hillquit and John F. Hylan.

(Image: “New York Times cartoon 4 Nov 1917” by Marcus for The New York Times. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons).

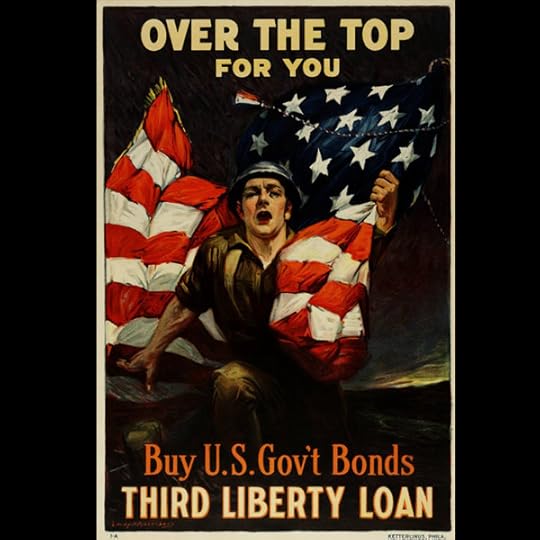

"Over the top for you"

During WWI, the US Government released four issues of Liberty Loans. The Third Liberty Loan Act allowed the government to issue $3 billion worth of war bonds at a rate of 4.5% interest for up to 10 years.

(Image: “Over the top for you – Buy U.S. gov’t bonds, Third Liberty Loan” by Riesenberg, Sidney H. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons).

Featured Image Credit: American soldiers on the Piave front hurling a shower of hand grenades into the Austrian trenches by Sgt. A. Marcioni. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post WWI propaganda in America appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers