Oxford University Press's Blog, page 427

December 18, 2016

Finding the imposter: understanding a rare delusional disorder using brain connectivity

In residency, I met a patient who told me a peculiar story about an encounter with his pet cat. He began to feel that his world was strange and unfamiliar. He became scared, paranoid, convinced that he was being tracked by federal agents. But the most distressing and bizarre change occurred in his pet cat. He told me he recognized his cat, that the cat had the same color and type of fur, ate the same food from the same bowl, walked and jumped and played with the same idiosyncrasies as his cat. But it wasn’t his cat. It was an imposter.

His syndrome was a variant of Capgras syndrome, where a patient develops the delusion that a family member has been replaced by an identical imposter. Knowing what to look for, I began finding more and more cases: a man with Alzheimer’s who believed his daughter was an imposter, a woman with a right frontal lobe stroke who believed her house was a replica of her real house. Some patients had the opposite feeling, believing that strangers were actually familiar persons in disguise (Fregoli Delusion).

While these delusions, collectively referred to as delusional misidentifications, were initially described in psychiatric patients, several of the patients I saw had focal brain lesions. So, my colleagues and I asked whether studying these patients might help us to understand how the brain produces such bizarre yet specific delusions. In the tradition of classical neurology, we attempted to “localize” the part of the brain that was responsible for these delusions. However, while we found that most injuries occurred on the right side of the brain, there was no single location where the brain lesions always occurred.

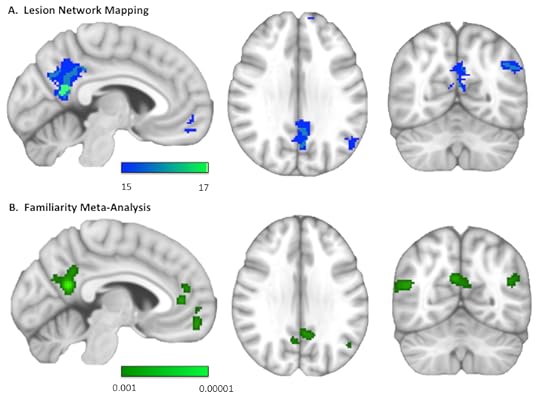

We therefore tried to test an alternative idea: that lesions in one brain region disrupt brain activity in other parts of the brain as well. This approach is not new; Constantin Von Monakow first proposed this idea, called diaschesis, over 100 years ago. However, we used a relatively new technique called lesion network mapping, which uses the human connectome to determine areas that are functionally connected to the location of a focal brain injury. Using this technique, we found that lesions causing delusional misidentifications in different locations had the same pattern of brain connectivity.

Network mapping of delusional misidentification lesions overlaps with regions involved in familiarity detection. Image provided by the authors and used with permission.

Network mapping of delusional misidentification lesions overlaps with regions involved in familiarity detection. Image provided by the authors and used with permission.Importantly, this connectivity was to brain regions that could help to explain why these patients developed these specific types of delusions. All the lesions causing delusional misidentifications were connected to regions involved in familiarity, explaining why patients with the imposter syndrome may lose this feeling of familiarity. Additionally, 16 of the 17 patients had lesions connected to regions involved in evaluating beliefs, potentially explaining why these patients accept their delusional beliefs as true. Brain lesions that didn’t cause delusions were not connected to these brain regions, explaining why these other patients did not develop delusions. Finally, we looked at lesions causing different types of delusions, like paranoia and jealousy. These delusions do not involve any abnormal feelings of familiarity, so shouldn’t be connected to familiarity regions. However, because they have delusions, these patients should have lesions connected to belief evaluation regions. That was exactly what we found: lesions were connected to belief evaluation, but not familiarity, regions.

We used lesion network mapping to “find the imposter” hiding in the brain, showing how a single brain injury might alter the relationship between two interacting sets of brain regions. Our findings don’t give the entire story for why delusional misidentifications occur, but they do provide an important step towards answering this question. Moreover, using functional connectivity to test for diaschesis could lend insight into other complex, bizarre neuropsychiatric symptoms that remain difficult to understand.

Featured image credit: Brain by Pete Linforth. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Finding the imposter: understanding a rare delusional disorder using brain connectivity appeared first on OUPblog.

Nationalism and Brexit

Was the vote for “Brexit” an expression of nationalism? It depends what we mean by nationalism and what kind of nationalism is involved. I define nationalism as the belief that national identity provides the focus of political loyalty and is best expressed and secured through independence, usually a sovereign nation-state. Nationalism consists of ideas (elaborate statements, slogans, symbols), politics (movements, parties), or sentiments (beliefs, attitudes). So far as sentiments are concerned, I distinguish two different types of nationalism.

Civic nationalism stresses shared beliefs and values. Ethnic nationalism stresses common descent, sometimes signaled by claims about religion, language, or race. We must qualify this distinction. Every nationalism invokes culture and values, and these change, often quickly. Religion and language cannot easily be labelled ethnic or civic as they are neither just a matter of personal choice, nor of fixed inherited qualities. Moralizing the distinction – e.g., civic good, ethnic bad –cannot be justified historically either. Nevertheless, the distinction helps us analyse nationalist sentiments. Nationalism can be state-supporting or state-opposing. State-supporting nationalism aims to further nationalize the state, internally by ‘purifying’ the nation and its institutions, and externally by reclaiming ‘national’ territory and extending national power. State-opposing nationalism seeks independence for “its” nation, usually by separation from a state, less often by merging smaller states.

Applying these ideas to the referendum

During the EU referendum vote about 70% of the electorate voted, splitting roughly 52/48 between Leave and Remain. There were some 13 million registered voters who did not vote and about 7 million people eligible to vote who were not registered. Leave votes were higher within older age groups, and generally those with less formal education, lower social groups, the retired and unemployed, and Conservative or UKIP voters in the 2015 General Election. Were voters divided in terms of “nationalism”? To quote from the summary of the exit poll of some 12,000 voters conducted by Lord Ashcroft’s polling organisation. St George’s Day 2010 – 18 by Garry Knight. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

St George’s Day 2010 – 18 by Garry Knight. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

White voters voted to leave the EU by 53% to 47%. Two thirds (67%) of those describing themselves as Asian voted to remain, as did three quarters (73%) of black voters. Nearly six in ten (58%) of those describing themselves as Christian voted to leave; seven in ten Muslims voted to remain. In England, leave voters (39%) were more than twice as likely as remain voters (18%) to describe themselves either as “English not British” or “more English than British”. Remain voters were twice as likely as leavers to see themselves as more British than English. Two thirds of those who considered themselves more English than British voted to leave; two thirds of those who considered themselves more British than English voted to remain. In Scotland, remainers (55%) were more likely than leavers (46%) to see themselves as “Scottish not British” or “more Scottish than British”.

Nearly three quarters (73%) of remainers think life in Britain is better today than it was 30 years ago; a majority (58%) of those who voted to leave say it is worse. By large majorities, voters who saw multiculturalism, feminism, the Green movement, globalisation and immigration as forces for good voted to remain in the EU; those who saw them as a force for ill voted by even larger majorities to leave.

The sentiments of a typical Leave voter can be characterised as ethnic. English identity is not about citizenship but linked to common language and heritage and hostility to immigration.

Most Scottish voters identified themselves as Scottish and voted Remain. Earlier surveys indicate that Scottish nationalism expresses itself in civic terms. A “Scottish voter” is a UK citizen resident in Scotland. People born in Scotland but residing elsewhere could not vote in the referendum on Scottish independence in 2015; conversely citizens who had recently moved to Scotland could vote. We know that most Scots consider this reasonable and there is no significant difference in voting for independence between Scots by birth and upbringing and Scots by residence. (Indeed, the latter possibly were “more nationalist”.)

Parties and politicians campaigning for Leave stressed support for the British state, claiming the need to “take back control” from foreign elites. Yet the Remain campaign was supported by a majority of the Cabinet, and only the Democratic Unionist Party supported Leave (plus a lone UKIP MP). This is ethnic nationalism which invokes the English nation in support of the British state but against the British government and elites it labelled “Establishment.” Civic Scottish nationalists supported the British government in the name of the Scottish nation and regarded the English nationalist Leave majority as another reason to pursue the state-opposing course of independence. Such complexities show why we must define nationalism, identify different types of nationalism, and connect these to how people voted.

Featured image credit: Brexit “Vote Leave” in Islington, London June 13 2016 by David Holt. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Nationalism and Brexit appeared first on OUPblog.

Sugar plums and mince pies

The Worcester joiner, John Read, appears to have been a regular customer of Thomas Dickenson, but two purchases stand out: on 25 December 1740 and again on 26 December 1741 he bought sugar plums and spices to the value of 5 shillings and 2 pence. Perhaps these were a special treat for his family, marking the festive season with small luxuries to relieve what was probably an otherwise rather unremarkable diet. Imported groceries were by no means a novelty, of course. In elite households, sugar and spices had long been used liberally to make food more flavoursome, but also to mark status—these were costly goods, imported from overseas and often from the other side of the world. They were by no means out of reach for poorer consumers, but—as Read’s small purchases make clear—they were hardly an everyday item.

Thomas Turner, a Sussex shopkeeper and likely a notch or two wealthier than Read, ate well enough in his own home and more occasionally at the houses of friends and relations. Meals were centred around roast or boiled meat, vegetables, and boiled puddings, the last of which often called for pepper or nutmeg, sugar, raisins, and sometimes almonds. His Christmas dinners (carefully recorded each year in his diary) were distinct in the slightly larger variety of food on offer. They typically comprised roast or boiled beef, turnips, potatoes, pearl barley pudding, plum suet pudding, and bullace pies. Local fresh produce was thus combined with sugar, spice, and dried fruits from further afield to create a modestly generous spread.

Scrooge’s third visitor, from Charles Dickens: A Christmas Carol. Illustration by John Leech, 1843. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Scrooge’s third visitor, from Charles Dickens: A Christmas Carol. Illustration by John Leech, 1843. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.These were a long way from the kinds of menus that appeared in the cookbooks published in growing numbers during the eighteenth century. Indeed, it is unlikely that Turner’s wife had either the resources or the inclination to consider using one of these publications to plan or guide her cooking. They would have been more use to Grace Nettleton, who kept house for her nephew-in-law at Tabley Hall, Cheshire in the 1710s. She made occasional purchases of pepper, cinnamon, nutmeg, and mace—a fairly typical set of spices—and also bought sugar and dried fruit. Grace was thus well equipped to prepare a wide range of the dishes appearing in books such as Henry Howard’s England’s Newest Way in all sorts of Cookery, first published in 1708. However, many of the purchases that she made were cakes, biscuits, and pies, suggesting that wealthy consumers then as now were happy to buy pre-made goods.

Of particular interest in this respect were two sets of mince pies bought on 25 December 1720. Six of them cost a shilling apiece and were probably intended for the family since they were distinguished from “eight mince pies for ye folks,” which cost just 6 pence each. It is impossible to know exactly what differentiated the two sorts of pie, but there are clues to be found in cookbooks. Howard, for example, provides two recipes. The first uses neat’s tongue, suet, and currants, flavoured with cloves, mace, preserved orange, and lemon peel, and cooked in verjuice, rosewater, and sack. These, he recommends, should be cooked in a variety of elaborate shapes. The second is more modest: the tongue is replaced with eggs, the currants with cheaper raisins and pippins, and the preserved orange, verjuice, and sack are omitted. The result is less rich and less costly.

Of course, the other thing of note in Grace Nettleton’s purchases is that the baker’s or confectioner’s shop where the mince pies were bought was open on Christmas Day itself. This was by no means unusual in the eighteenth century; whilst rather more than simply another trading day, only occasionally does the festive season seem have impacted on shops in a direct sense. One rare example comes from Norwich in the 1780s, where a confectioner called widow Cockey advertised that, for Twelfth Night, her shop would be “handsomely illuminated and decorated after the London taste with Plumb Cakes.” Not to be outdone, another confectioner announced that “his Shop will be illuminated in a most elegant Manner, and decorated in the Pastry Way, with all the Ornaments that Art and fancy can invent.” Then as now, it seems, Christmas was an excuse for additional advertising and promotion.

Featured Image Credit: “Home made mince” pies by Nick. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Sugar plums and mince pies appeared first on OUPblog.

A thousand and one translations

18 December is UN Arabic Language Day. We’re celebrating by reading Arabian Nights’ Entertainments, the most influential English translation of Alf Layla wa Layla (One Thousand and One Nights).

What do Jane Austen, William Makepeace Thackeray, Charles Dickens, Charlotte Brontë, Robert Louis Stevenson, Joseph Conrad, H.G. Wells, James Joyce, Salman Rushdie, and Hanan Al-Shaykh have in common? Give up? Other than all being great authors who write in English, they were all influenced by One Thousand and One Nights.

It’s difficult to overstate the significance of One Thousand and One Nights in our literary tradition, and yet this work of literature historically bore little resemblance to what we might recognize today as the Arabian Nights. In Arabic, the earliest fragments of the text (including the frame story involving Scheherazade, who tells a story each night to Schahriar to keep him from killing her) date to the ninth century, though the stories most likely circulated orally for centuries before that—it’s thought that the oldest stories originated in India and Iran. Later, in the tenth to twelfth centuries, the One Thousand and One Nights corpus grew to include stories originating in Baghdad, the cultural capital of the Arab world at the time, including the adventures of the caliph Haroun Alraschid and his vizier Giafar. (Spellings of characters’ names vary—in this article, I’m using the spelling that appears in the Oxford World’s Classics edition of Arabian Nights’ Entertainments, but you may recognize “Giafar” better as “Jafar,” as in Disney’s Aladdin.) Still more stories were added to the corpus in Cairo in the twelfth to fourteenth centuries; these stories often contain elements of ancient Egyptian folklore: tricksters, magic talismans, demons, and genies. Until the nineteenth century, there was never a single standard version of One Thousand and One Nights—aside from the definitive frame story, storytellers and compilers might choose to include or exclude stories associated with the collection to suit their own aims.

Although the first “authoritative” versions of One Thousand and One Nights in Arabic did not appear until the nineteenth century, the earliest French and English versions, which tacitly claimed to draw from a standardized source text, appeared a century earlier. In fact, rather than straightforwardly translating a single source text, Antoine Galland, the first translator of One Thousand and One Nights into French (as Mille et une nuit), drew on a variety of sources, including old manuscripts and the folk tales he heard from a traveling Maronite Christian from Aleppo, Hanna Diab. Some of the most popular stories in Galland’s Mille et une nuit—Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves and Aladdin and the Lamp among them—were probably not a part of the original One Thousand and One Nights at all. Critics tend to agree that, as one E.F. Bleiler put it, “translation [may be] too precise a word” for what Galland did to his Arabic sources.

Image credit: Aladdin; or, The wonderful lamp by Walter Crane. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Aladdin; or, The wonderful lamp by Walter Crane. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Arabian Nights’ Entertainments was, in turn, a translation not of any Arabic source text but of Galland’s Mille et une nuit. Known as the “Grub Street” translation, there is no named translator of the work. Arabian Nights’ Entertainments proved very popular—it was adapted countless times for children, usually with a moralistic tone (e.g., Oriental Tales, Being Moral Selections from the Arabian Nights Entertainments calculated both to Amuse and Improve the Minds of Youth (1829)), and in spite of attracting scorn from some critics for being perceived as too “feminine,” the work was widely read and worked its way into the psyches of many great British writers, from Jane Austen to H.G. Wells.

The influence of Arabian Nights’ Entertainments has been far from all positive—the stories, which romanticize and exoticize a monolithic “East,” added fuel to the Orientalist fire that swept Britain in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and we should be careful not to assume that details and the atmosphere of the stories in Arabian Nights’ Entertainments are factual rather than invented by Antoine Galland. (To combat the risk of making this assumption, I recommend reading Arabian Nights’ Entertainments in tandem with the excellent One Thousand and One Nights by Hanan al-Shaykh.) Though One Thousand and One Nights has mostly reached us as an Orientalist translation of a translation of a hodgepodge of stories, it is nonetheless important to recognize how much the modern British and American storytelling tradition owes to the art form as it developed in Baghdad and Cairo so many centuries ago.

Featured image credit: “Islamic Art” by hoomarg. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post A thousand and one translations appeared first on OUPblog.

The logic of unreliable narrators

In fiction, an unreliable narrator is a narrator whose credibility is in doubt – in other words, a proper reading of a narrative with an unreliable narrator requires that the audience question the accuracy of the narrator’s representation of the story, and take seriously the idea that what actually happens in the story – what is fictionally true in the narrative – is different from what is being said or shown to them. Unreliable narrators are common in fiction. Notable examples include Agatha Christie’s The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Akira Kurosawa’s Rashômon, and Ron Howard’s A Beautiful Mind.

There are all sorts of interesting philosophical questions one might ask about unreliable narrators and how they function as a storytelling device. Here, however, I am going to point out some purely logical features of unreliable narrators.

Presumably, although the full account is no doubt more complex, one of the primary factors that determines whether a narrator is reliable, and to what extent, is the ratio between the number of (fictionally) true claims made by the narrator to the total number of claims made by the author. All else being equal, the higher this ratio, the more reliable the narrator is. Now, consider two stories. The first story – S1 – involves the narrator making n claims for some number n:

S1 = {C1, C2, C3… Cn}

And let’s assume that, for some number m ≤ n, m of these claims are true. So the relevant ration is m/n. The second story – S2 – is exactly like the first except for the addition of one more claim by the narrator: the claim that he or she is unreliable, which we shall call U:

U = “I am an unreliable narrator”

Hence:

S2 = {C1, C2, C3… Cn, U}

Now, there are two possibilities. Either U is true, or U is false. If U is true, then the ratio of truths to falsehoods is (m+1)/(n+1). But, for any positive finite numbers m and n where m ≤ n:

(m+1)/(n+1) > m/n

So, although the narrator of S2 might well be unreliable, he or she is more reliable than the narrator of S1 which fails to contain the admission of unreliability U. Note that this also implies that the narrator of S1 must have been unreliable as well.

If U is false, however, then then the ratio of truths to falsehoods is (m)/(n+1). But, for any positive finite numbers m and n where m ≤ n:

m/n > (m)/(n+1)

So, although the narrator of S2 might well be reliable, he or she is less reliable than the narrator of S1 which fails to contain the admission of unreliability U.

The latter fact – that a reliable narrator claiming to be unreliable in fact makes them less reliable – is perhaps unsurprising and uninteresting, the fact that an unreliable narrator admitting their unreliability makes them more reliable is more interesting. Before examining this fact further, however, it is worth noting that there is a Truth-teller like phenomenon in the vicinity as well.

Consider a story where the narrator, in addition to narrating the story, also claims to be a reliable narrator (perhaps, along time-honored traditions, by beginning the story with “Everything I am about to tell you is true”). Via computations similar to the above, if the narrator of a story not containing a claim to reliability of this sort is generally reliable then the narrator of a story otherwise identical but supplemented with such a claim to reliability is even more reliable, and if the narrator of a story not containing a claim to reliability of this sort is generally unreliable, then the narrator of a story otherwise identical but supplemented with such a claim is even less reliable.

Now, although it involves fictional truth (i.e. what claims we ought to make-believe to be true when consuming a fiction) rather than actual truth, at this point this puzzle looks like nothing more than a variant of the Liar paradox and the Truth Teller. But there is a secondary puzzle that arises once we have noted the Liar-like behavior of “I am an unreliable narrator.”

Whether or not a narrator is reliable, and more generally, the extent to which a narrator is reliable, is typically not something the author of a work announces at a press conference or prints on the cover of a book or DVD, but is instead something that the reader or viewer of a work has to decipher for him-or-herself from clues included in the story. On the face of it, one piece of evidence that we might think to be definitive in this regard is an admission of unreliability by the narrator him-or-herself. But, as we have seen, such an admission in fact makes the narrator more reliable, rather than less, if the narrator is in fact generally unreliable. In short, the sort of claim that we might, on the face of it, take to be good evidence of the presence of an unreliable narrator turns out to be much less useful than we might have first thought.

On the other hand, the results given above do suggest a sort of informal decision procedure for determining whether or not the narrator of a work is generally reliable or not. When confronted with a story where the evidence seems indeterminate with regard to whether, and to what extent, we should “believe” the narrator, we can just imagine a story that is similar except that the narrator claims to be reliable. If the narrator of the original story was generally reliable, the narrator of this new story will be even more reliable, and if the narrator of the original story was generally unreliable, then the narrator of this new story will be even more unreliable. Presumably, the more pronounced reliability, or unreliability, in the new story will be easier to detect than the original degree of reliability or unreliability in the original story was. If there still isn’t enough evidence to decide, then simply add another claim to reliability on the part of the narrator. And if this isn’t enough, add another one. Presumably at some point the reliability, or unreliability, of the narrator will become so extreme that it will be impossible not to spot, in which case the narrator of the original story will be generally reliable or generally unreliable if and only if the narrator of this new expanded story is (although not, of course, to the same degree).

Now, clearly the recipe just given is absurd – this algorithm for detecting whether or not a narrator is reliable or not just won’t work. But it strikes me as a little bit difficult to say exactly where it has gone wrong.

Featured image: Book by Kaboompics // Karolina, Public Domain via Pexels.

The post The logic of unreliable narrators appeared first on OUPblog.

December 17, 2016

Dystopian times: that sinking feeling

Notwithstanding a few near misses (the Austrian presidential election), many more liberally-minded readers will probably reflect back on 2016 as a year of loss and anxiety. Two significant shocks—Brexit and the election as US President of a reality TV star billionaire with neither political experience or knowledge—have severely dented our sense of the logical progression of our times. Repeatedly, we have been forced to ask whether we are not moving in a retrograde direction, and whether in particular a right-wing populist agenda driven by hysterical propagandists spells doom for more tolerant, inclusive world-views and threatens anew to unleash the hatreds which proved so destructive throughout most of the 20th century.

To my mind these fears are not misplaced. Neither, however, are they new. A pervasive sense of crisis in fact defines much of the dialectical counterpoint to the recurrent official optimism of progress which constitutes the dominant ideology of the modern period. To Marx, capitalism would eventually self-destruct in one final cataclysm, producing at the same time the earthly paradise of the proletariat. To Schopenhauer, a natural cultural pessimism was the logical concomitant to the age of the masses. By the late 19th century, indeed, it was becoming evident that the pattern of urban industrial modernity and an increasingly dominant world-market mechanism might well prove more disruptive of humanity’s aspirations for betterment than not. From this perspective the moment of optimistic, expansive progression, which seems in retrospect to define most of the second half of the 20th century, now seems more the exception than the rule.

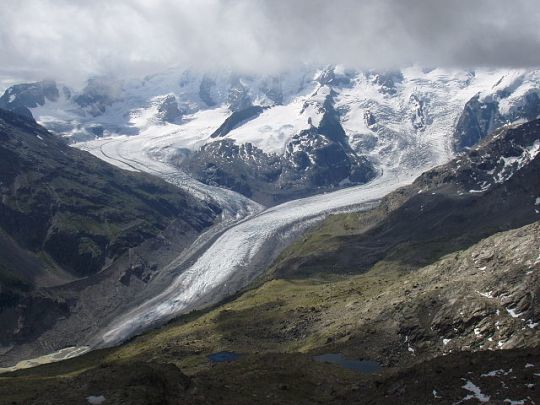

Morteratsch (right) and Pers (left) glaciers in 2005. Photo by Günter Seggebäing CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Morteratsch (right) and Pers (left) glaciers in 2005. Photo by Günter Seggebäing CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.But there are still more sobering reasons to suppose that things are getting worse rather than better. Our fears of the past two centuries have mostly involved mass society, revolution, capitalist exploitation, and crisis, and then, after 1945, the prospect of nuclear war. Now we face an environmental crisis of a magnitude which puts all these anxieties in the shade. We will not, it seems, “master nature,” as Bacon and Marx alike hoped. Nature is rightly angry at us and will have her retribution. While all our anxieties since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution have been contingent—they have involved things which might happen but also might not—global warming is certainly happening, and with a speed which leaves even scientists deeply dismayed. No amount of new iPhones, or advances in medicine, or in our ability to forestall ageing and disease, will stave off the calamitous eventuality of an earth which can no longer support its inhabitants. If, as now seems increasingly likely to be the case, we witness a constant process of warming across the next decades, we are likely to reach systemic collapse towards the end of this century. With a population of over 10 billion, this will produce the mother of all crises, and quite possibly the last.

This prospect ironically both heightens and diminishes the great shocks of 2016. So serious is the threat of this looming future that even the election of Donald Trump as president in 2016 would seem in retrospect to be a tedious mishap, reparable in four years. Yet we are all aware that the very people who will pace the corridors of the White House for the next four years will also be those who are most likely to ignore our greatest future perils. Many deny climate change. Most have an interest in avoiding the topic. The language they will speak will be jobs, business, money, making America great again. The 38% of the British electorate who voted for Brexit will echo similar sentiments, and the Daily Mail will assure them that Britain too is on its way back to greatness even as our further detachment from Europe dooms us to greater insignificance than ever before. So as the year draws to a close we are rightly bound to feel anxious, alarmed, and despondent. We are speeding down the path to dystopia, the bad place from which few return, with our eyes closed, chanting a mesmeric mantra of denial. We can only hope that we wake up while there is still time to apply the brakes.

Featured Image Credit: “Derelict” by Paul Hudson. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Dystopian times: that sinking feeling appeared first on OUPblog.

The best of Illuminating Shakespeare

To mark the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, we brought you a new theme every month throughout 2016. From women to race, from money to the supernatural, we delved into complex subjects surrounding his life and works, exploring their relevance for a modern audience. With specially commissioned videos, articles, and interactive content from a host of Shakespearean experts, Illuminating Shakespeare presented the very best Shakespeare resources from across Oxford University Press. Take a look at nine of our favourite posts from this anniversary year…

1. Shakespeare and sex in the 16th century – [infographic]

Did you know that Shakespeare created many more unfaithful wives than unfaithful husbands? He also created many more paranoid male partners than female. Shakespearean explorations of sexuality involve the collisions of identity, eroticism, and power.

“Without Islam there would be no Shakespeare” begins Matthew Dimmock, Professor of Early Modern Studies at the University of Sussex, in his exploration of Shakespeare’s encounters with Islam and Islamic culture for the Shakespeare and Religion theme.

3. Shakespeare across the globe [map]

Even mere decades after Shakespeare’s works were published in London, they had circulated from the west coast of Africa to New York City. Only a century or two after that, his plays had reached places like Japan, China, Italy, and Argentina. For the theme of Shakespeare Worldwide, take a look at some of the locations where Shakespeare and his work have had a profound effect in our interactive map.

Bildnis William Shakespeare, 1939; Berlin, Heinrich Vogeler. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Bildnis William Shakespeare, 1939; Berlin, Heinrich Vogeler. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.4. “This blasted heath” – Justin Kurzel’s new Macbeth

For the theme of Shakespeare and Film, Erin Sullivan (one of the revising editors of the second edition of The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare) explores the sumptuous and bloody 2015 adaptation of Macbeth starring Michael Fassbender and Marion Cotillard.

5. Michael Dobson on Shakespeare and the Supernatural

From the ghost in Hamlet to the miniature fairy Queen Mab from Romeo and Juliet, in this short video Michael Dobson explores Shakespeare’s use of all elements of the supernatural. Paradoxically, his witches and fairies and devils coexist with a scepticism about their very existence.

6. Quiz: last lines in Shakespeare

“I kill’d not thee with half so good a will” – whose dying words were these? Death is everywhere in Shakespeare, from the blasted heath to the marriage bed to the battlefield. The Oxford Dictionaries team test our knowledge of dying words of various Shakespeare characters.

7. Shakespeare and the suffragettes

As it approaches 100 years since the Representation of the People Act, introduced in 1918, Sophie Duncan looked back at the role of Shakespeare in the campaign for women’s suffrage. She explores how suffragettes found political inspiration in Shakespeare’s heroines, for the theme of Shakespeare and Women.

8. What music would Shakespeare’s characters listen to?

To celebrate the important relationship between Shakespeare and Music, we imagined modern playlists for some of Shakespeare’s most famous characters. Do you agree that Beatrice would have enjoyed a bit of Chaka Khan and Beyoncé? Or do you think Henry V would have worked out to ‘All I Do is Win’ by DJ Khaled?

9. Shakespeare’s clowns and fools [infographic]

Fools, or jesters, would have been known by many of those in Shakespeare’s contemporary audience, as they were often kept by the royal court, and some rich households, to act as entertainers. For the theme of Shakespeare and Performance, take a look at a host of facts around these subversive figures.

Featured image credit: ‘Shakespeare400’ design created for Oxford University Press. Used with permission.

The post The best of Illuminating Shakespeare appeared first on OUPblog.

Philosophy in 2016: a year in review [timeline]

This year was an important one for the field of philosophy. As the year draws to a close, the OUP Philosophy team takes a moment to reflect. We’ve compiled a general selection of the key events, awards, anniversaries, and passings, which shaped philosophy in 2016. From the 2,400th anniversary of the birth of Aristotle, to the loss of Hilary Putnam, take a moment to browse our interactive timeline.

Which events would you add to the timeline? Let us know in the comments.

Featured image: The Thinker by Rodin, photograph by Johnnie Shannon, Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Philosophy in 2016: a year in review [timeline] appeared first on OUPblog.

December 16, 2016

Did the United States invent teenagers?

The United States did invent teenagers. That is a historic fact, just as Americans invented the telegraph, telephone, PC, and atomic bomb. While much progress has been made over time with many inventions, less so with teenagers. By the 1920s, they were populating the United States, doing the same things as teenagers do today. Then as now, teenagers wanted to borrow the keys to the family car, had part-time jobs to generate money to support their social lives, and as American households obtained telephones, yes, guess who used them a great deal? Apparently the initial invention of teenagers must have been good enough if they behaved the same way over the next century, even if they stayed out too late at night, dominated tastes in clothes and music, and worried their parents.

They became a common commodity, sharing a profoundly influencing uniform experience for them and the nation: they attended high school. By the middle of the 1920s, high school experience had become relatively homogenized across the nation. A graduate from the Class of ’25 would have recognized what was going on in a high school in 1985, or later. Public high schools were part of a universal school system, one that supported sports teams, art appreciation, music programs, and 4-H, and that encouraged kids to go on into the military and to college.

How did more schooling and parenting lead to the invention of teenagers? First, as the nation industrialized, beginning largely after the Civil War (1861-1865), millions of people left their farms and went to work in factories. By World War I, labor movements and unions were forming all over the nation. To keep their employment high, unions and other labor groups advocated for young people not to take away their jobs through lower wages, but rather to stay out of the labor market entirely so that adult workers could be paid higher wages. But there were a lot of young people ages 11 through 18 at a time when the nation had a young population, due to the formation of families producing many babies, and tens of millions of young immigrants entering the country before World War I. What was the nation to do with all these youngsters?

4-H Cake by Lesley L. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

4-H Cake by Lesley L. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.Keep them in school! The logic for that solution was perfect. As the economy industrialized, future workers needed to know new things: mathematics, physics, how to operate machinery, to show up on time, to take instructions, to be able to read, to follow an operating manual, and to read a blueprint. High schools could teach these subjects, so labor supported states mandating that young potential workers stay in school. First it was through eighth grade, later to at least ages 16 or 17, and even later to graduate from high school, all paid for with property taxes. It worked. By the 1930s, the majority of teenagers entered high school and by the end of World War II most graduated.

The need to keep them out of the labor market and to equip them with new information to succeed in the New Economy led to a new class of people cleverly named teenagers. Before they were teenagers, they had been young workers in workshops, factories, and, of course, down on the farm.

But just having something new is not enough; it has to have a name, an identity, a brand. The PC was a tiny computational machine of some sort until IBM gave it a name: Personal Computer. Data transmission over dial-up phone lines needed a name for it to work. It got one—Internet. So, young workers now in school got theirs—Teenagers.

And that leads to the second way teenagers were invented. Beginning in the late 1800s, doctors began specializing in various sub-fields of medicine, like surgery or children. That trend led to the invention of pediatricians and psychologists—two new information-based specialties—who then began to point out that people under and over the age of 10 had different physical and mental circumstances. The latter, for example, experienced puberty and were interested in, dare we say it, sex. With Sigmund Freud a fashionable source of information about how humans behaved in the 1920s and 1930s, experts began advising parents about their older children—teenagers.

Experts were counseling parents on how to deal with new problems surfacing from these children: rebellion against authority, their urge for independence, resistance to supervision, and sexual liberation. Parents and schools developed school sports, Scouting, 4-H, and other activities to consume a teenager’s interests and to burn up their physical energy. Articles in popular magazines and books began appearing in the 1920s, a type of publication that continues to this day. Parents turned to these, because many in the 1920s and 1930s had not been teenagers, they had worked. This was new to them.

After World War II, it seemed every parent became exposed to Dr. Benjamin Spock and the “latest thinking” about how to raise children. He became the best-selling author in the United States from the late 1940s through the 1960s, outpacing even sales of the Bible, which in the 1800s had been the best seller in the United States. Tens of thousands of articles were published about teenagers in the second half of the twentieth century, ensuring that they would remain a fixture of American society.

Teenagers were invented by the rising tide of information that called for a new type of worker. It provided something for these older children to do, and assisted parents in dealing with this new type of person. Today almost every country on Earth has teenagers. With helicopter parents and the push to go to college, Americans may be expanding teenage-hood to the mid-20s. Is this 2.0 for teenagers, another contribution of the American Information Age?

Featured Image Credit: Lincoln High School by David Sawyer . CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Did the United States invent teenagers? appeared first on OUPblog.

What is it really like being a doctor?

Last year there were nearly 150,000 doctors employed by the National Health Service. Since 2004 this figure has been increasing annually by 2.5%. Doctors, whether they are gynaecologists, cardiologists, or GPs to name a few, are an extremely important part of our society.

So what is it like being a doctor? What are the hardest decisions doctors have faced in the field? Andrew Baldwin, Nina Hjelde, and Charlotte Goumalatsou share their experience and insight, answering questions from junior doctors around the world, on making difficult decisions, time constraints, juggling learning the latest medical knowledge and workload, as well as what being a doctor really means to them.

What is the hardest decision you’ve ever made as a doctor? – Chin Wei Wong (Coventry, UK)

Nina Hjelde: The toughest moments for me have been when I’ve made the conscious decision to stay late and help a colleague or patient at the cost of missing a key moment in my personal life… Medical school trains you, to a certain degree, to deal with death and breaking bad news. It never warned me how much of your own family you sometimes have to sacrifice.

Charlotte Goumalatsou: As a junior registrar I was on call and there was a woman with abdominal pain who was 28 weeks pregnant. Her membranes had ruptured three weeks beforehand and there were signs of impending chorioamnionitis. I examined her and there had been a cord prolapse at 2cm dilated, which leads to fetal demise very quickly if delivery is not imminent. There was a flicker of fetal heartbeat activity on the scan, but fetal position, lack of amniotic fluid, and my inexperience as a scanner made the scan difficult. So I made the decision to take the woman to theatre for an emergency caesarean section and called in the consultant from home. Unfortunately, the baby was born with no signs of life and didn’t respond to resuscitation. I often look back at that delivery and wonder if I did the right thing. But I know that I couldn’t have not acted, and not given that baby a chance.

Benchmarking by marcelohpsoares. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

Benchmarking by marcelohpsoares. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.Andrew Baldwin: We make difficult decisions every day when it comes to looking after patients; however for me, choosing which specialty to train in was probably most difficult. I found everything interesting. But I have no regrets about becoming a GP; the wide variety of knowledge required, running a business, and building long-term relationships with patients are very fulfilling.

How do you deal with the time constraints that are put on doctors when treating patients? Do you ever get frustrated by it? Do you have any particular tips to making sure a patient feels valued and acknowledged? – Victoria McKinnon (Ontario, Canada)

Andrew Baldwin: As a GP in the United Kingdom, I get frustrated every day by time constraints. I generally see 40 patients a day. But you can use short periods of time over weeks and months to build relationships and get to know your patients. My tip would be to find something out about your patient. While visiting an elderly man recently, he told me how in World War Two he crashed his Wellington bomber aircraft into the Mediterranean and spent two days afloat on a life-raft before being rescued. Inspiring!

Nina Hjelde: Smile and give a little personal story about yourself. Even something as mundane as the fact that the new rain jacket your mum bought you was put to good use in the storm this morning. It makes you more human and patients really appreciate that.

Charlotte Goumalatsou: I think this gets easier with experience in some ways – you will arrive at decisions quicker and your communication style will become more efficient. And to make patients feel valued, sometimes you have to let them sit down and shout or rant without interruption. This usually lasts a maximum of two minutes and then it’s possible to take a history and get on with the consultation.

What is your advice for keeping up-to-date with the latest medical knowledge, while being so occupied with work in hospital, sometimes only being able to sleep for five hours? – Elaine Kar Man (Pahang, Malaysia)

Nina Hjelde: Don’t be too hard on yourself if you don’t manage to read every journal! I recommend that you become familiar with the local guidelines since those will be regularly revised based on the best evidence.

Charlotte Goumalatsou: I never find time to go to the library now or sit for ages studying, and there’s no magic answer. Just squeeze in ten minutes when you can, before bed and over a cup of tea when on call.

Andrew Baldwin: Life is difficult for junior doctors! Having recently qualified, you will be up-to-date with much of the latest medical practice. My advice would be to focus on the specialty you are rotating through – learn from your seniors or read around a specific case you have seen.

What does being a doctor mean to you?

Charlotte Goumalatsou: I always knew I wanted to do medicine, like you just know that you are left or right-handed. I love the problem-solving aspect, working in a team in theatre and on labour ward, the emergency situations, having women as patients, and getting to operate. Delivering a baby never gets old and since having a baby myself I find it more emotional than before.

Andrew Baldwin: Actually, I hope that my identity is not caught up in being a doctor, despite the title and all-consuming nature of the work. Why medicine? It’s difficult to articulate but there is something so special about the human body in health and disease, the people who come attached to that body and the people we get to work with.

Nina Hjelde: I love the fact that you have such a privileged and unique opportunity to play a role in someone’s time of need. You also get to work alongside some of the most incredible people.

Featured image credit: Stethoscope by Parentingupstream. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post What is it really like being a doctor? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers