Oxford University Press's Blog, page 426

December 21, 2016

The fruit of the loom and other looming revelations: Part 1

When we deal with old languages, Jacob Grimm’s rule works rather well. He suggested that homonyms are usually related words whose meanings had diverged too far for us to recognize their original unity. One can demonstrate the validity of this idea even while looking at some modern forms. For instance, autumn is called fall in American English, and it takes minimal effort to connect the season’s name with “the fall of the leaf.” By contrast, spring “to jump,” spring “the source of a stream,” and spring “a season of the year” have almost come apart, and people hardly think of them as related, though of course they are.

Obviously, not all homonyms are related. For example, we have sound, as in the sounds of music; sound, as in Long Island Sound; sound, as in sound judgment, and sound “to probe the depth of” (one can also sound one’s colleagues as to their intentions). Some of them may be related, or perhaps each word has its own etymology, even if our intuition suggests the possibility of ties here and there. To discover the truth, one needs the help of a professional historical linguist. But the general advice stemming from Jacob Grimm’s approach is valid, namely: “When you encounter homonyms, ask whether they are related.”

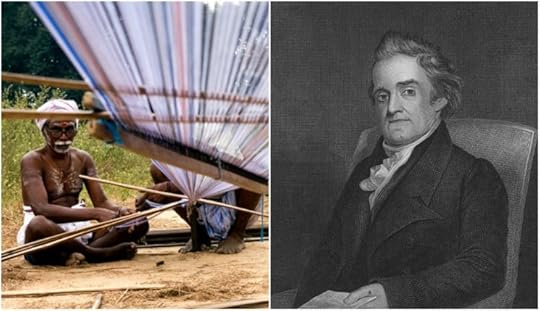

Observe a weaver and a loom on the left. On the right is our hero, Noah Webster. His family name means “weaver.”

Observe a weaver and a loom on the left. On the right is our hero, Noah Webster. His family name means “weaver.”This is what I am going to do with two words: loom “weaving machine” and loom “to appear indistinctly” (there is also a third word, but it will appear as an afterthought). Although the origin of both is supposedly unknown, the picture may not be so opaque. We have to begin from afar. Loom “weaving machine” is (as Skeat showed) the remainder of weblōme, while lōme is the stub of Old Engl. ge-lōme “implement, utensil” (ge- is an ancient prefix, whose obliterated remnant e- can be seen in enough: compare it with German ge-nug, the same meaning; some people may have seen in dictionaries the participle yclept “called”; ō designates long o). Heirloom contains apparently the same element, even though it surfaced in texts only in late Middle English. I wonder whether hoodlum, which, according to at least one suggestion, goes back to a family name, can be derived from hoodloom. Was the original Mr. Hoodlum a hatter?

While thinking of heirlooms, don’t forget the heirloom tomato (the American name of the vegetable). It is called heritage tomato in Great Britain. The main description on the Internet praises it’s (sic) valuable characteristics.

While thinking of heirlooms, don’t forget the heirloom tomato (the American name of the vegetable). It is called heritage tomato in Great Britain. The main description on the Internet praises it’s (sic) valuable characteristics.Side by side with gelōme “implement” stood gelōme “often.” It occurred mainly in the tautological phrase oft and gelōme, something like “often and frequently” (such binomials are not too rare: compare safe and sound, prim and proper, fine and dandy, and so forth; they are like tautological compounds of the courtyard type, on which see my post for 11 February 2009). The prefix ge- was a marker of collective nouns, so that perhaps gelōme “utensil,” along with its Old English synonym andlōman “furniture” (that word had a Dutch cognate), once meant “utensils, stuff,” rather than a single implement. Oft and gelōme, as well as gelōme, continued into Middle English and then “died.”

Before going on, I have to mention the little-known Modern Engl. adjective loon “gentle, easy” (this is the afterthought). Loon, unlike all the words mentioned above, is not an etymological orphan, for it is allied to Dutch loom “slack; languid.” It also had many cognates in Middle High German in the form of the suffix –luomi (uo in it developed from ō). This sound complex showed a strange aversion to an independent existence: also, in Old English, –lōme did not occur without ge-, a phenomenon that baffles me but is probably of no importance in our search for origins.

I will cite only two Middle High German adjectives, because their meaning is easy to guess: sumar-luomi “sunny, hot” and gast-luomi “hospitable.” The suffix meant something like “susceptible to, provided with.” The other adjectives, of which there are about half-a-dozen, follow the same pattern. Jacob Grimm connected the suffix –luomi with the root of the adjective lame, from lam-, a congener of Slavic lom-, as, for example, in Russian lomat’ “to break” (stress on the second syllable). This derivation works very well for the adjective meaning “slack” (from “slack, weak” to “lame”) but worse for the suffix attested with the sense “provided with.” However, the contradiction will disappear if we start from the meaning “break,” as in Slavic, because broken means both “not solid” and “incapable to offer resistance, yielding.” Sumar-luomi and gast-luomi can therefore be understood as “yielding to summer” (hence “sunny, hot”) and “yielding to guests” (hence “hospitable”).

The sense “broken” will also provide us with a bridge to Old Engl. ge-lōme “often.” Let us repeat that “broken” can mean “not solid; soft, yielding” (such is a broken reed) and “made up of odds and ends, in fragments; in close proximity but lacking cohesion” (such is a broken social order). In the languages of the world, the notion “often” tends to go back to “thick, dense, crowded together” or “heap, mass.” The most transparent examples are German häufig (Haufe “heap”), Dutch dick-wijs (dick “thick”; –wijs is a suffix), and Russian chasto (chastyi “thick, dense, frequent,” applied to heavy rain, thicket, etc.); compare also Engl. thick and fast. In Old Engl. gelōme, the suffix ge– is as though it were made to order, for us to discover the origin of the adverb and the noun. At one time, the noun (“implement, utensil”) must have designated a heap or a set of tools. I made this suggestion at the beginning of the post.

Occasionally I see objections to the etymologies I defend because they are not perfect: the idea looks attractive, but some details do not click. Very much depends on the nature of the imperfection. When an established sound correspondence is violated, it has to be accounted for. Likewise, when senses are at cross-purposes, they have to be harmonized. Grammar is an equally important factor. For example, the English word wife was once neuter (German Weib still is). In my opinion, all the etymologies of wife proposed by numerous scholars were wrong because they failed to explain the gender of the noun: indeed, how could a word for “woman” be neuter?! (Those interested in a possible answer to this fateful question should consult my post of 12 October 2011; it has the provocative title “Were ancient ‘wives’ women”?). In Icelandic, skáld “skald, poet” is neuter. Alas, I have no idea why. But the fact that the sense “utensils” (plural) in gelōme has not been recorded does not look like an insurmountable obstacle to accepting the etymology proposed above. The prefix points to a collective noun. Probably the sense “stuff” yielded the meaning known to us. In any case, the Old English adverb gelōme “often” appears to align itself perfectly with the adverbs of the same meaning in several languages. It must have suggested the idea “made up of odds and ends.”

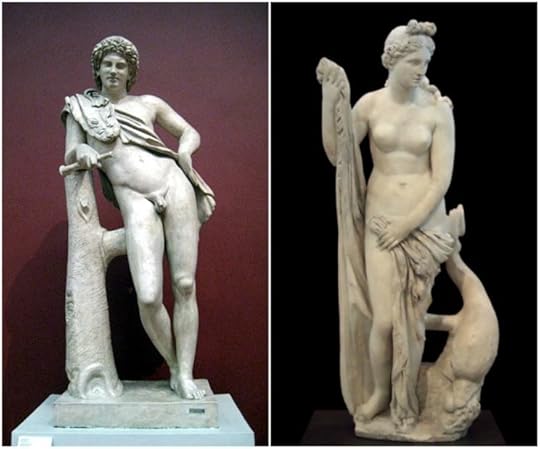

Only Praxiteles is perfect. Etymologies seldom are.

Only Praxiteles is perfect. Etymologies seldom are.Thus, from “broken, lacking cohesion; yielding” to “slack, weak, gentle,” to “a heap or set of things; utensils,” to “loom” (a single utensil), and, most unexpectedly but not illogically, to “often.” I am sorry to say that Engl. oft(en), unlike Old Engl. gelōme, lacks a persuasive etymology. Perhaps it belongs with häufig, dickwijs, chasto, and the rest, but the picture is far from clear.

Yes, but what about loon “gentle” and the verb loom? Wait until next week.

Images: (1) “Weaver in India” by Claude Renault, CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons (2) “Noah Webster engraving” Photographed from the holdings of the University of Manitoba, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. (3) Heirloom tomatoes by Amy Guthrie, Public Domain via Pixabay. (4) “Leaning satyr by Praxiteles” photo by Shakko, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons (5) “Roman Venus Copy of Praxiteles Front” photo by Shawn Lipowski, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Featured Image: Autumn, forest by Valentin Sabau, Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post The fruit of the loom and other looming revelations: Part 1 appeared first on OUPblog.

9 fascinating facts about festivals in ancient Greece and Rome

Festivals in ancient Greece and Rome were important periods of time during which people performed “activities that are most often thought of as communications with the superhuman world.” Marked by a variety of unique cultural rituals and traditions, festival days stood in stark contrast to ordinary life in ancient Greece and Rome. Processions, sacrifices, athletic events, and musical performances were just the start of some of the interesting highlights. The ways in which the ancient people chose to express themselves on these special calendar days is fascinating. In examining both its contrasts and similarities to today, studying ancient culture can be seen as the study of our own humanity.

To demonstrate some of the unique aspects of culture in ancient Greece and Rome, we compiled a list of these 9 facts about some festivals in ancient Greece and Rome.

1. To celebrate the goddess Bendis, Thracians in Athens held night-time torch races on horseback. Referenced in Plato’s Republic, these races were quite popular around the time of Socrates in the late 5th century BCE.

2. During Skirophorion, the last month of the Athenian calendar, Athenians sacrificed a plow ox to Zeus Polieus, the protector of civic order, on the Acropolis. According to research, “ordinarily, one did not sacrifice plow oxen; they were valuable work animals, and often they must not have been perfect enough to qualify as sacrificial animals. The sacrifice was followed by a trial that accused the sacrificer of murder; he shifted the blame to the sacrificial ox, which was convicted and drowned in the sea; the killed ox was resurrected by stuffing its hide with straw.”

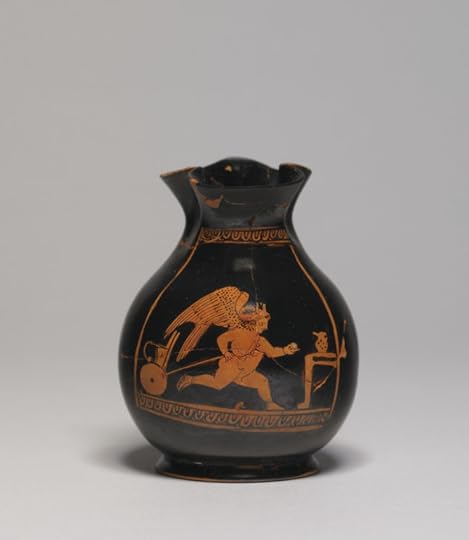

“Red-Figure Chous with Eros,” circa 410 BC. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“Red-Figure Chous with Eros,” circa 410 BC. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.3. Anthesteria, a festival of Dionysus, was of an importance comparable perhaps to modern Christmas. Despite its name suggesting anthos (meaning flower), Anthesteria was associated particularly with the production of new wine. It was celebrated in the correspondingly named month Anthesterion, roughly late February. On the evening of the first day, ‘Jar-opening’ (Pithoigia), pithoi of the previous autumn’s vintage were taken to the sanctuary of Dionysus in the Marshes, opened, offered to the god, and sampled.

4. During Anthesteria, a strange major ritual was held. On the day of Choes, ancient Greek for “pitchers,” participants would sit alone and drink a chousor (about three liters of wine) that they emptied without speaking. Social boundaries collapsed as slaves took part. “Miniature choes were also given as toys to children.” Receiving the ‘first Choes’ was a landmark occasion.

5. Also on the day of Choes, Athenians would smear black pitch on their house doors and chew backthorn leaves to ward off evil.

6. For unknown reasons, Romans were very reluctant to have one festival immediately following another, so they introduced an empty “buffer day” between festivals following one another.

7. During the festival of Bona Dea, men (including even male dogs and statues) were specifically excluded from the celebration. At the beginning of December, Roman matronae celebrated the festival by acting as sacrificers and consuming large quantities of wine. The exclusion of men and the radical inversion of upper class female behavior fit into the rituals of the last month of the year, experimenting with social boundaries, and proposing alternative–albeit temporary–models of behavior.

8. The Saturnalia were the merriest festival of the year, ‘the best of days’ (Catull. 14. 15). Presents were exchanged, particularly wax candles and Sigillaria, and as a general rule, Romans at this time inverted their normal behavior. Slaves were either served by their masters or dined with them, and were allowed temporary liberty to do as they liked.

9. During the drawn-out, boisterous carnival of Saturnalia, people enjoyed relaxed meals at home, painted their faces black as if they were wearing a mask, replaced the formal white toga with an informal dress and felt cap (which was proper to slaves), and played with the otherwise prohibited dice.

Featured image credit: “Ave, Caesar! Io, Saturnalia!” Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, 1880. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post 9 fascinating facts about festivals in ancient Greece and Rome appeared first on OUPblog.

Networks of desire: how technology increases our passion to consume

When we walk into a restaurant, we are often confronted by the sight of people taking pictures of their food with their smartphones. Online, our Facebook feeds seem dominated by pictures of people’s hamburgers and desserts. What is going on with food porn? This question leads us down the rabbit hole of technology and passion, into rather arcane theories of consumer desire. Through investigated food porn, the search widened. How is consumer desire itself transformed by contemporary technology?

Investigating past literature about technology showed that most of the writers thought that using technology has a rationalizing effect. As we use technology, we become more logical and calculating, and this reduced passion. But with food porn, it’s the opposite. We took a closer look at food porn using the method of “netnography,” a type of anthropology that uses social media to investigate and understand human culture. We collected data for over a decade on different kinds of online food-related communities, and studied how they demonstrated passion and what effect technology had on that passion. We also interviewed prominent food bloggers and restaurateurs about their role as content creators. In addition, we used social networking site tools to provide an open forum for people to contribute their own food porn, answer polls, and tell stories about the emotions they attach to food porn.

The conclusion? Our smartphone and computer technology directs and intensifies our most basic human passion. People, their smartphones, their passion, and the objects of their desire all combine into a system. That system affects all the players within it. So computers, food, and human beings are all joined into a circuit that increases the flow of desire among them.

The biological necessity for food had become a passion for food that has now translated into a passion for more technology.

The idea that desire can flow like energy came from our exploration of one of the most comprehensive—and difficult—theories of desire. In this theory, which relates in many ways to ancient forms of belief about the role of energy in human life, desire is treated as a free-flowing form of energy. Desire connects us to each other, and also to things, and sophisticated machines like software and smartphones. When they are connected, these things behave like a system, and they direct and amplify the flow of desire. We call this a “network of desire.” Desires do not merely end in culmination or satisfaction. They build. And as they are building up energy, they can inspire great creativity.

Machines were not only directing these desires, but also building in us the desire for more machines. The biological necessity for food had become a passion for food that has now translated into a passion for more technology. We live in an age where sexting drives people to suicide, where augmented reality video games instantly gain legions of followers who storm public places such as cemeteries, where Presidential candidates announce policy platforms on Twitter, and where fundamentalist-based international terrorist organizations successfully recruit using YouTube and WhatsApp. Indeed, it seems as if the news is getting nastier, celebrities are acting more outrageous, general language is sounding more crude, political positions are becoming more polarized, religious beliefs are more extreme, and on and on through culture and society. Our increasing codependence with technology is playing a role in this mass increase of our passions.

Our collective linking into a vast network of technology might be leading us into a future of rapidly changing, highly segmented taste clusters. Consumers of the future, each micro-segmented into interface-driven categories of consumption desire, might transform ever more rapidly from their other interests and other connections as they pursue their own individual peaks of passion. Consumers, networks, and consumer culture itself turn into things whose hungers have no limits, whose capacity changes by the hour. Unleashing new abilities for us to couple with machine bodies, object bodies, and branded bodies, we literally become posthuman.

Very recently, our adoption of technology seemed to offer more democratic, authentic, and grassroots places to commune and converse. Yet it now appears equally likely that technologically-enabled consumer networks also function as effective amplifiers of corporately monitored and sponsored desires. In the midst of this situation, it seems very important that we try to understand what is happening to our society. Directed by the technology and capitalism, changing rapidly in taste, pushed by our passions to posthuman extremes, we must continue to wonder and explore what our use of technology is doing to us.

Featured image credit: Food grilled chicken by Ananya440. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Networks of desire: how technology increases our passion to consume appeared first on OUPblog.

Passenger lists and their uses: the example of Anglo-American marriages

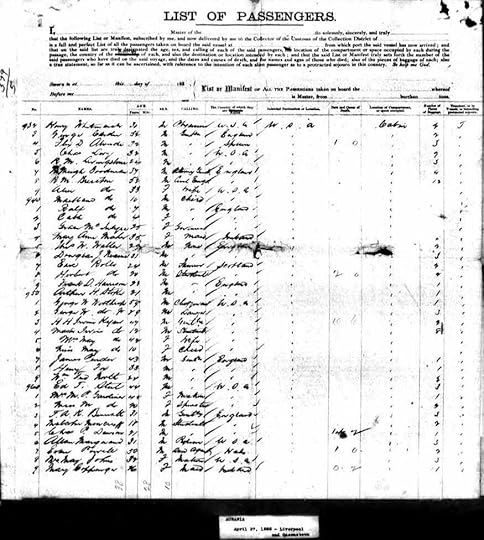

On 27 April 1885, Alice Brereton (née Fairchild) returned to America with her family. The Aurania’s passenger list includes her British-born husband and their three children. From information contained in the list–name, age, citizenship, and occupation–we can reconstruct aspects of the family’s history revealed in other public documents.

Alice was born in a small town in upper New York State in 1852, the daughter of a jeweler. Her husband, born in 1833 in a small village in Norfolk, England was the son of a clergyman. Both families seem to have valued education. Robert trained as a civil engineer. In 1870 we find Alice attending school far from home in San Francisco. It is there that she likely met and married Robert. Their first child was born in the city in 1875. However, three years later they were in Hereford, England. Their second and third children were born in England. Robert made trips to the United States in 1876 and 1877. In 1885 the family apparently relocated permanently to America. A fourth child was born in Montana in the same year. The 1910 US census shows a household comprised of Robert and Alice, their youngest child, and a daughter-in-law and a boarder, both from Minnesota.

The excerpt from passenger list for Aurania, 27 April 1885, is saved from U.S. National Archives and Records Administration database, New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957, accessed through Ancestry.com.

The excerpt from passenger list for Aurania, 27 April 1885, is saved from U.S. National Archives and Records Administration database, New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957, accessed through Ancestry.com.The above is an example of the kind of research in family history undertaken by hundreds of thousands of people each year. Popular interest in genealogy has generated a level of demand for information from public records, much of it monetized, far beyond what could have come from professional researchers. The result has been a dramatic improvement in online access to scanned images of original records held in public archives. Digitization has focused on producing indexes by name and basic demographics, allowing individuals to be traced across different sets of records.

My interest in the Brereton family, however, stems from research into Anglo-American marriage patterns using passenger lists for Liverpool to New York crossings. The data base includes 342 family groups of two or more members, including at least one American, traveling Cabin class. These were drawn from 15 crossings from 1854 to 1856, 22 for 1875, and 27 for 1885. All were spring crossings from Liverpool to New York drawn from the US National Archives and Records Administration database, New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957.

From 1854 to 1856 and in 1875, mixed nationality family groups, mainly Anglo-American, accounted for 12% of all groups including Americans. In 1885, the figure was somewhat higher at 16%. Most mixed groups were based on intermarriage between Americans and non-American (mainly British) citizens. However, the pattern of intermarriages changed over time. In the 1854-1856 period, over 70% of intermarriage groups involved American men marrying non-American (mainly British) women; in 1885, just over 70% were based on American women taking non-American (mainly British) husbands. In 1875, 55% of intermarriages involved American men; 45%, American women.

An off-the-shelf explanation for the change in pattern is that in the 1854 to 1856 period, mixed groups were the result of naturalized Americans, now established in their new country, “retrieving” wives and families from Britain. In the 1880s the popular image of Anglo-American marriage was of well-off American women marrying much less well-off British aristocrats and gentry. In the first instance, there is no evidence in the passenger lists since naturalized Americans are not distinguished from native-born. Regarding the second, the occupational evidence does not fit the pattern. The British husbands in 1885 are diverse group: civil engineer, contractor, merchant, stevedore (in cabin class!), and two identified as “gentlemen.” The history of the Breretons is informative because in contrast to the popular image of elite Anglo-American intermarriages, the operative factor is the presence of a British man in America, almost certainly engaged in professional employment. The family’s movements likely reflect the career opportunities of an engineer working internationally.

To move forward we need two kinds of research. First, the pattern sketched above needs to be tested with an expanded sample. Second, we will need to delve into the histories of many representative families. The second is well supported by infrastructure developed to meet the needs of genealogical researchers. The first is not. Currently there are no publicly available large scale databases containing passenger records that can be used for computer-based analysis.

Constructing such a data set is difficult, time-consuming, often tedious work. Lists before World War I are handwritten with legibility frequently an issue. The agents employed time-saving practices ranging from less than transparent abbreviations to actual suppression of information, most flagrantly, by simply declaring, as seemed policy for at least one line from 1875, that all working age males would be listed as “gentlemen.” Yet a database of passenger lists at a time when transatlantic steamers were the “only way to cross,” might support research in a number of areas. I have demonstrated elsewhere that the lists provide a window on the evolving American class structure. The list also makes visible the strong presence of transatlantic business travelers, providing a basis for new work in the undeveloped area of 19th century business networks. Finally, as the example above shows, the lists can also be used to explore transatlantic family and social networks. The database would be worth what it would cost to build.

Feature Image Credit: The image of Aurania is courtesy of the Norway Heritage Collection. Source: www.heritage-ships.com. Used with permission.

The post Passenger lists and their uses: the example of Anglo-American marriages appeared first on OUPblog.

Religion and the Second Redemption

A tense, volatile electoral season, accusations of “voter fraud,” and real instances of thuggery on the campaign trail. Documented instances of real voter suppression due to newly instituted state policies attempting to restrict voting disproportionately by race. Real or implicit threats of violence against minority voters. Surging anti-immigrant and exclusionist sentiment, particularly against relative newcomers who practiced seemingly strange religions. And a beleaguered set of progressive civil rights and church leaders, who looked to the recent past when the signs seemed so much more hopeful.

Some might describe the recent electoral campaign that way, but I have in mind the election campaign of 1876. The Democratic candidate, the New Yorker, Samuel Tilden, appealed to aggrieved white voters tired of government intervention on behalf (as they perceived it) of newly enfranchised or non-white citizens. The Republican candidate, Rutherford B. Hayes, had his own set of issues involving corruption, and faced an electorate suspicious of his party’s identification with the freed people and their demands.

Tilden won the popular vote, and led Hayes with 184 electoral votes to 165 after the first count of votes. Disputed returns in three states, particularly Florida, left twenty electoral votes remaining. Eventually after much debate, Democrats in Congress agreed to cede those votes to the popular vote loser, Hayes, in return for an effective end to Reconstruction. Thus, Tilden became the only candidate ever to receive more than 50% of the popular vote, but lose the electoral college count.

In subsequent decades, newly “redeemed” state governments (“redeemed” from Reconstruction), under white Democratic control, instituted far-reaching measures of voter suppression that destroyed the effective intent of the 14th and 15th Amendments to ensure equality for emancipated slaves. The era that contemporaries trumpeted as “Redemption,” was unfortunately marked by a cleansing of the nation’s soul from the “alleged sins” of Reconstruction. Surging sentiments of white nationalism, xenophobia, and mistrust of government intervention towards those perceived as less worthy fueled growing tides of racist sentiment expressed politically and culturally.

Down to the 1876 gulf between the popular vote and electoral vote winners, the divisive campaign just fought has the feel of the era of Redemption,. More importantly, however, both elections empowered a significant counter-reaction to civil rights advances, and saw the rise of white nationalist groups (nowadays referred to with euphemisms such as “alt-right,” but in reality entirely similar to groups that rose to fight Reconstruction) to political and cultural prominence.

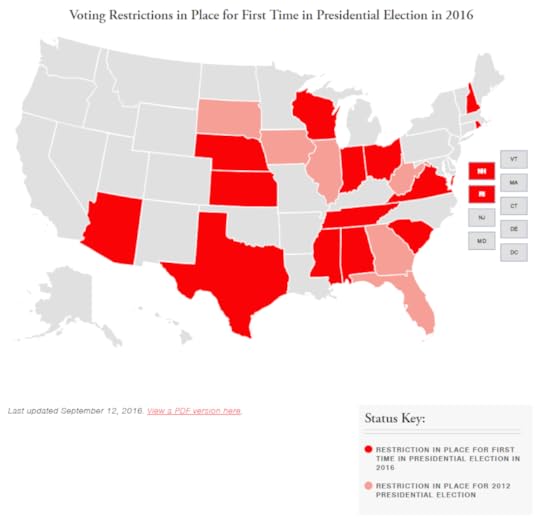

“Voting Restrictions in Place for First Time in Presidential Election in 2016.” Used with permission from the Brennan Center for Justice.

“Voting Restrictions in Place for First Time in Presidential Election in 2016.” Used with permission from the Brennan Center for Justice.Nationally, the contemporary story has been hijacked by the focus on a “recount,” and of “voter fraud.” The first won’t change anything, and the second has been discredited repeatedly. For all the national talk of “voter fraud” in both cases, the real story for the long term was of carefully targeted voter suppression. That was starkly, often violently, true of the 1870s and 1880s. In more subtle and hidden ways, it is true today.

During the Reconstruction era, Black church leaders anticipated issues of suppression. Energized by the political opportunities opened up by the Reconstruction Act of 1867, they entered the political arena avidly and defended the civil and spiritual rights of the freed people. Meanwhile, white para-military groups and terrorist cells in the 1860s and 1870s focused on reversing the revolutionary political gains made by freedmen after the war. One ex-slave most succinctly expressed his view of what the violence endemic in the postwar South really meant: “That was about equalization after the freedom. That was the cause of that,” he said. Consequently, by the late nineteenth century, black political gains had been nearly completely wiped out, and the majority of black citizens again disfranchised.

During the Second Reconstruction – that of the 1950s and 1960s – the story ended differently. The passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965, one made possible by the massive spiritual energies tapped by the Civil Rights Movement , provided effective enforcement mechanisms that guarded against a second Redemption. The federal government would not abandon the rights of black voters this time. The political climate of the country was revolutionized. Massive increases in black voting and office holding followed, and the Second Reconstruction spurred its own political counter-movement: the wholesale migration of white southerners from the Democratic to the Republican Party.

Flash forward to 2013, and effects of the Voting Rights Act were reversed. Chief Justice John Roberts, defending the Supreme Court’s decision to strike down key parts of the Voting Rights Act, declared that “Our country has changed.” Civil rights leaders joined the dissenters on the 5-4 divided Court in pointing out the ways in which the country had not changed. With states no longer requiring to “preclear” voting law changes, voter suppression violently accomplished during Redemption could now be legally achieved in the ongoing Second Redemption.

In 2013, North Carolina legislators tried to lead the way. They drafted a new state voting requirement law that would disproportionately reduce black and Latino voting. Documents later uncovered revealed that, as the circuit-court opinion put it, the restrictive voting measures targeted African Americans “with an almost surgical precision,” helped along by data collected by Republican legislators in the process of drafting the law. The racially discriminatory intent was obvious. An appeals court struck down the law. A divided 4-4 Supreme Court left that reversal in place. In 2017, the new Supreme Court coming may well decide differently.

Voter suppression through the closure of polling facilities, carefully crafted voter ID laws, the disfranchisement of ex-felons, the restriction of early voting days, and like measures suggest the new mechanisms by which a second Redemption will take place. Nationally, well over eight hundred polling facilities closed from 2012 to 2016. In Mississippi, for example, state authorities closed the polling place at the Mt. Olive Baptist Church – where the three civil rights workers had visited shortly before their murder in J une 1964.

Church leaders, both white and black, played a key role in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965. White evangelicals today, in supporting candidates that enact voter suppression laws, can be seen as reprising their roles as leaders of the forces of Redemption, down to repeating discredited charges of “voter fraud.”

And thus, the struggle for the ability to exercise democratic rights continues even today. As with the eras of Reconstruction and the civil rights years of the 1950s and 1960s, the role of progressive church people in mobilizing on behalf of an expansive democracy will be key to its preservation. As the leaders of the civil rights movement knew, freedom is a constant struggle.

Featured image credit: “United States Capitol.” CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Religion and the Second Redemption appeared first on OUPblog.

December 20, 2016

The Affordable Care Act and cancer screening in Medicare

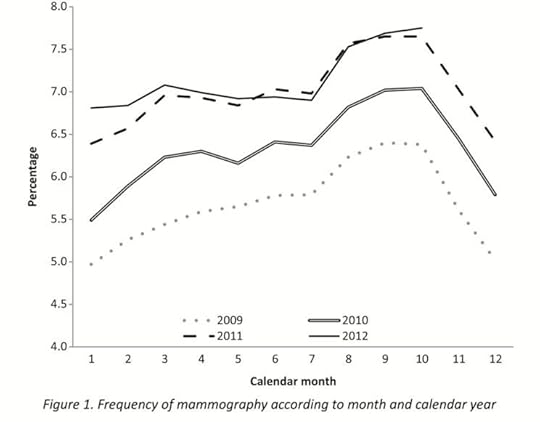

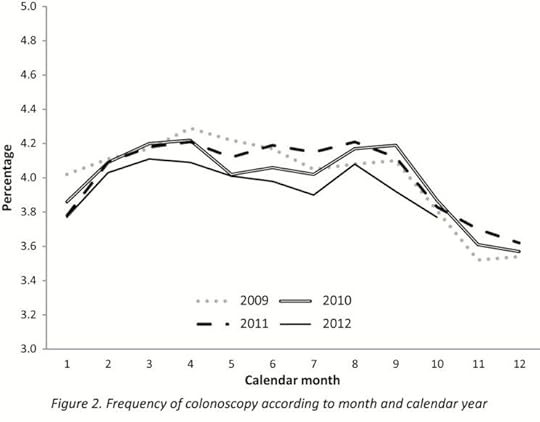

Universal screening for breast and colorectal cancers are currently recommended as methods to reduce the mortality associated with these diseases. Mammography is capable of detecting cancer before it has the opportunity to invade into lymph nodes or other organs, and colonoscopy is able to not only detect early stage cancers, but by removing precancerous polyps, prevent cancer from developing. Although both procedures have been covered by insurance, patients often faced significant deductibles and/or copayments. Thus, there is evidence that members of lower socioeconomic groups are less likely to be screened with mammography and colonoscopy, with out-of-pocket expenses associated with these tests being an important barrier. The Affordable Care Act (ACA), which among other features, waived all out-of-pocket expenditures for recommended preventive services, was enacted in the United States in 2011 for Medicare beneficiaries.

So did the ACA have an impact on screening mammography and colonoscopy in Medicare? Previous studies of initiation of Medicare reimbursement for routine mammography and colonoscopy found increased use after implementation. With this in mind, we hypothesized that the ACA’s elimination of copayments and deductibles would promote uptake of these preventive screenings.

We found that whereas monthly mammography use after the ACA was enacted did increase by approximately 2% compared with the pre-ACA period of 2009–10 (Figure 1), colonoscopy uptake was stagnant (Figure 2). We found that individuals in the “younger” age groups of Medicare (less than 75), who would derive the greatest longevity benefit from early detection, did have a larger uptake in mammography and colonoscopy than others. Also, patients who utilized the Medicare Wellness Visits, which are designed in part to provide a schedule of preventive services, were also more likely to undergo testing.

Although the study was limited to older patients and only looked at the first two years of ACA coverage (2011-2012), we found mixed results for the ACA’s impact in this population. Compared to colonoscopy, because mammography does not require other preparation and is noninvasive, it may be easier to facilitate in the general population. In contrast, colonoscopy requires a bowel preparation and intravenous sedation and has a small risk of complications and it is not known from our study whether these remained as deterrents to its uptake. Also, because of a loophole in the ACA legislation, colonoscopy procedures that result in removal of polyps are considered diagnostic, even if the indication for the procedure was preventive. Although there are ongoing attempts to fix this loophole through legislation, at this time, diagnostic procedures are still subject to copayments. It is uncertain whether this was another barrier to colonoscopy receipt.

Our findings suggest that elimination of out-of-pocket expenditures is an important step to increase the uptake of preventive services, especially mammography. Other recommended cancer preventive services, including Pap testing and fecal occult blood testing are also covered in full by the ACA and the impact of the legislation on the uptake of these procedures is not known. However, keep in mind that follow-up procedures to evaluate positive tests are considered diagnostic, not preventative, and are subject to copayments. We would suggest that further studies should examine the long-term impact of the ACA in other patient groups, including privately insured and Medicaid recipients. In addition, other benefits of the ACA in improving access to care such as expansion of Medicaid eligibility in a subset of states should be evaluated.

Image credit: Photo by GDJ. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post The Affordable Care Act and cancer screening in Medicare appeared first on OUPblog.

What is the future of behavioral economics?

Behavioral economics is a fast growing field within economics. We caught up with Sanjit Dhami to discover how he came to specialise in behavioral economics, how it has developed, and what he thinks is in store for the field in the future.

Could you tell us a bit about yourself?

I did my BSc Honours and MSc Honours in economics from the Punjab School of Economics in India. I left home for the first time to pursue my MPhil in Economics at the Delhi School of Economics in University of Delhi. This was followed by a second Masters in economics and a PhD in economics from the University of Toronto in Canada.

Having completed my PhD in 1997, I took up my first academic job, a lectureship at the University of Essex in Colchester. After spending two years in Essex, we moved to the University of Newcastle and in 2003, I took up a lectureship at the University of Leicester, where we have lived ever since.

In a few words, could you describe what exactly behavioral economics is?

Behavioral economics models human behavior by using insights that are drawn mainly from economics and psychology but also, critically, from socio-biology, sociology, anthropology, and neuroscience. Its domain encompasses both market and non-market behavior.

How did you become interested in this field?

When I arrived at the University of Leicester in 2003, I chanced upon a talk by a colleague Professor Ali al-Nowaihi on behavioral decision theory, a branch of economics that deals with situations of risk, uncertainty, and ambiguity. Ali argued that the existing mainstream decision theory, expected utility theory, is rejected by a large body of evidence, while prospect theory, the leading decision theory in behavioral economics, explained the empirical facts much better.

I decided to test prospect theory on the well-known “tax evasion puzzles” that were outstanding for more than three decades. This successful experience convinced me that I ought to explore behavioral economics more fully. This led, in due course, to a variety of papers that I published jointly with Ali in many diverse areas such as behavioral decision theory, other-regarding preferences, behavioral time discounting, and behavioral game theory. Like me, he is happy to explore any interesting research question in economics. This accounts for why our research straddles so many diverse areas in behavioral economics.

Hopefully, the prefix behavioral in “behavioral economics” will be shed in due course. After all, what other kind of economics is there?

How has behavioral economics developed over the years?

Behavioral economics has its roots that go back, at least to Adam Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments that was published in 1759, although it is the other book by Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations that gets cited more. Despite much interesting work in the interim, modern behavioral economics really began in the 1970’s with the work of Daniel Kahneman, Amos Tversky, and Richard Thaler. The work done in the 1970’s was the first attempt at stringently testing the basic features of the classical model in economics. This, and subsequent empirical attempts, have found the classical model seriously wanting, which has given impetus to more realistic behavioral models.

It is fair to say that behavioral economics is the fastest growing and most exciting field in economics. The development of behavioral economics is simply in the nature of scientific progress in economics. It currently appears that the steepest gradient for progress in economics is provided by behavioral economics. Hopefully, the prefix behavioral in “behavioral economics” will be shed in due course. After all, what other kind of economics is there?

What do you hope to see in the coming years from the field?

I would like to see progress in many areas of behavioral economics. After all, it is still a relatively young field and the best is surely yet to come. We must continue to stringently test behavioral theories and be prepared to shed those that do not work—taking a religious position with respect to theories never works in science. One of my favourite quotes is by the Nobel Prize winning physicist Richard Feynman, who said: “We are trying to prove ourselves wrong as quickly as possible, because only in that way can we make progress.” Economists would do well to heed his advice.

What is one thing people would find surprising about behavioral economics?

Humans can hugely underestimate their future self-control problems. The result is that some of us find it difficult to get things done and we procrastinate too much. We like to believe that in the future we will have fewer self-control problems so we often put off making decisions, such as cleaning our rooms/cars or visiting an ailing neighbour. Often, in the future, we tend to have the same self-control problems; the result is that in many cases things never get done.

This is not to say that we are not trying to discover ourselves. We often engage in good deeds and acts of piety to convince ourselves (and others) that we really are good people. We also try to take actions to bind ourselves in the future. For instance, we are reluctant to raid a children’s education account or a book account.

Are you attending any conferences or events in the next year or so?

I have just accepted an invitation to be one of 5 international experts on the Finnish Academic Council that disburses research money. I have accepted a research fellowship in residence at the Centre for Economic Studies in Munich during the next summer. During this time I will also be giving a seminar at the University of Innsbruck in Austria. I am also presenting a paper at the 2nd psychological game theory conference in the University of East Anglia in July 2017.

Featured image credit: Cube red lucky number by caro_oe92. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post What is the future of behavioral economics? appeared first on OUPblog.

December 19, 2016

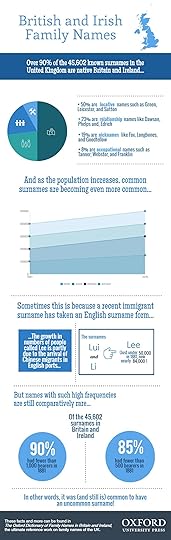

British and Irish family names [infographic]

As the population of Britain and Ireland grows, some surnames are becoming even more common and widespread, alongside a steady continuation of uncommon surnames; but how many of us know anything about our family names’ origins – where it comes from, what it means today, and exactly how long it has actually been around for? Names derive from the diverse language and cultural movement of people who have settled in Britain and Ireland over history, with many of the common surname bearers such as Smith and Jones rapidly increasing from 1881 to the present day.

Below you will find a brief exploration of family name statistics in Britain and Ireland.

Download the infographic as a PDF or JPEG.

Featured image credit:”Isle of Skye” by FrankWinkler. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post appeared first on OUPblog.

The Internet never forgets, unless the law forces it to

When I worked as a campus newspaper faculty advisor several years ago, a recent graduate once asked if we could remove an article about dating from the newspaper’s website because it was ruining his chances at romance. The graduate had been quoted, some years earlier, trying to make a joke about relationships, but the line came across in an unflattering way. He told us that whenever he met a new person he wanted to date, she Googled him and the news article invariably came up near the top of search results. He had decided that the article was going to prevent him from ever getting married.

Although the case might seem trite, I could feel how serious it was for this graduate. The newspaper staff debated what to do about information that was once true, but might have become outdated. The debate pitted free expression and historical truth arguments, on the one hand, versus the case for restored privacy and the right to control one’s own identity, on the other.

A similar debate is now playing out in legislative and judicial bodies around the world, under the catchy but perhaps misleading title of “the right to be forgotten.” Most prominently, this right has been endorsed by the

Human rights and business: is international law relevant?

Corporations are now widely seen as having responsibilities in regard to human rights abuses. This was thrown starkly onto the front pages recently when a number of high profile UK companies, including M&S and Asos, were caught up in allegations of child refugees from Syria working in very poor conditions for clothing suppliers based in Turkey. They are just one of many instances around the world where corporations have been shown to be involved in human rights abuses.

Traditionally, international law was only about States: what they did and why they did it. Now international law, while primarily about States is also concerned with the actions of international organisations, armed groups, non-state actors, corporations, individuals and others. Apparently, of the 100 largest economies in the world, 51 are corporations, as Amnesty International points out. The relationship between business and society is critical to standards of living and quality of life.

One of these developments has been in international human rights law. In 2011, the UN Human Rights Council adopted the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights 2011. This reinforced that states had the legal obligation to protect human rights, including in relation to corporations in their jurisdiction. It also made clear that corporations have a responsibility to respect human rights, including by undertaking human rights due diligence and having grievance mechanisms, and that both States and corporations had to provide adequate remedies for victims.

Corporations have a responsibility to respect human rights.

While the corporation’s responsibility may not necessarily lead to legal liability, there have been a range of developments at national, regional and international levels, which show where it is headed. For example, the UK introduced the Modern Slavery Act in 2015, which requires any company with annual turnover of £36 million or more (US$43 million) to produce yearly report on what steps it is taking to prevent slavery and human trafficking in any part of its business and supply chain wherever in the world. In March 2016, the Council of Europe issued Recommendations on Human Rights and Business, which require member states to apply measures which ‘encourage or, where appropriate, require’ mandatory human rights due diligence of companies domiciled or conducting substantial activities within their jurisdiction. There have also been a range of cases in Canada, The Netherlands, the UK and the US, which have shown a willingness by courts to extend the duty of care of parent companies for actions of their subsidiaries.

The need for companies across all industry sectors to do genuine, focused human rights due diligence is becoming ever clearer. However, research by the British Institute of International and Comparative Law and law firm Norton Rose Fulbright has uncovered some worrying findings that show many companies still aren’t doing enough to tackle the issue properly. The extensive report was the result of surveying over 150 companies around the world. It found that only 51 per cent undertook a dedicated human rights due diligence assessment which encompassed the full range of a company’s human rights obligations. The rest relied on catching human rights issues within other, more general due diligence.

Not undertaking human rights due diligence processes has risks for the company: reputational, financial, operational and legal. A picture or comment on social media from a local group far from the company’s headquarters can transform a company’s reputation very quickly. By the time the awareness of human rights risk reaches the board level, it is often too late to apply a preventative approach. In order to ensure the effectiveness of the human rights due diligence process, human rights impacts have to be recognised on the operational level, where the interaction with the rights-holders take place: on the factory floor; the construction site; the overseas operations; in the laboratory; and when supplies are procured.

Ignorance of human rights abuses is no defence. Companies will not only be liable for those human rights impacts of which they had knowledge, but also for what they ‘ought to have known’, had they been diligent. All human rights are potentially at risk of violations by corporations. The increase in regulation and litigation, including in regard to the actions of parent companies, increase the overall business risk to companies.

The direction of legal developments in this area is clear: human rights scrutiny is only going to intensify, and the human rights performance of companies is becoming an increasingly important corporate issue. It will also increasingly be part of international law.

Featured image credit: Building by Unsplash. CCO Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Human rights and business: is international law relevant? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers