Oxford University Press's Blog, page 425

December 24, 2016

Donald, we need to talk about Russia

Congratulations on a hard-fought campaign, Mr. President-Elect. As a reward, you now get the onerous task of governing the United States, and establishing its foreign-policy priorities! The campaign was crazy, with speculation about your personal and business links to Russia and your coziness toward Russian President Vladimir Putin giving way to evidence of a coordinated Kremlin attack on American sovereignty and the sanctity of our democracy. While you may deny American intelligence as a political nuisance or distraction, like it or not, your response to Russia is going to be central to both your administration’s foreign and domestic agendas.

A few (more) of our favorite things

As is becoming tradition, we want to use this, our last blog post of the year, to look back over last 12 months and remember all the fun we’ve had together. We have been drawn in by the “seductive intimacy” of oral history, and inspired by the power of audio to move “oral history out of the archives and back into communities.” We explored the world of transcriptionists and museum curators, and looked at projects that are putting oral history on the map. We asked practitioners to explain how they do oral history, and we are looking for contributors to expand this series in the coming year.

Our first series of the year was a dialogue between Tim Cole and Henry Greenspan about space and time in oral history interviews. In the first part, they delve into positioning and ask how we can think through a narrator’s physical and intellectual movements. In the second part, they wonder if “the now usual way we engage survivors and their retelling—the ‘testimony’ paradigm itself—is beginning to crumble.” Their conversation continues to spark ideas, and we are happy to help highlight the movements within our changing discipline

Another of our favorite things this year was the launch of our #OriginStories series, where we asked people from across the field to explain how they got into oral history, and why they love it. We started way back in February with Dana Gerber-Margie’s journey from the “gateway drug” of This American Life to her career as an audio archivist. Since then, we’ve heard from Adrienne Cain, Jessica Taylor, and Steven Sielaff, whose stories highlight both the power and value of oral history education.

In June, we celebrated Pride by talking to Josh Burford, who is using oral history and memory to resist anti-LGBTQ laws in North Carolina, and Jason Ruiz, who gave an in depth exploration of the article he co-wrote in The Oral History Review. The article was part of a special issue “Listening to and Learning from LGBTQ Lives” – another highlight from 2016. On the blog we also heard from contributors to the issue who explained the importance of music in queer memories, and the queer history of Madison, WI.

This year we also launched a blog takeover, where we invited students and alums from the Oral History MA program at Columbia University to occupy our little corner of the internet throughout the month of July. We are big fans of their blog and were excited to republish some articles by Audrey Augenbraum and Eylem Delikanli. One of my personal favorites was a piece by Andrew Viñales, in which he showed that oral history can be “a way for [students] to understand that the civil rights movement has never ended, that social justice movements always build from movements of the past.”

The most important event of the fall season is, of course, the OHA Annual Meeting, which took place in Long Beach, CA this year. We enlisted a local to explain some of the city’s fascinating history, and asked some of you to tell us what you love about the conference. We published a shortened version of a conference paper from Margaret Holloway, on her use of oral history in preserving a historically Black town in Alabama, and our own Troy Reeves took to the blog to show his gratitude for his OHA friends and family. We’re already counting down the days to #OHA2017, and hope you’re working hard on your proposals (reminder: the deadline for submission is January 31!).

Thanks for indulging our attempt to remember the good parts of 2016, even as we are eager to bid this year goodbye and good riddance. We hope to see you back on the blog again soon!

Featured image: “Christmas gift #3” by photochem_PA, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post A few (more) of our favorite things appeared first on OUPblog.

December 23, 2016

Mean racist, kind racist, non-racist: which are you?

“Race is real, race matters, and race is the foundation of identity.” I imagine that perhaps with a tweak or two, most people would be OK with this declaration.

Many people are aware that the concept of race has no biological validity; that it’s a social construct, like gender or money, real only in that we treat them as real. So, in response to the first part of the thesis, I imagine most people would say, “Race is a social construct with very real effects.” As such, race certainly matters in myriad ways. To the third part of the statement, I’d bet that most people would say something like, “Well identity is a multi-faceted thing. Race is certainly among the factors that interact to form the foundation of one’s identity.” Notwithstanding these slight adjustments, I expect there’d be few objections to the thesis.

If I’ve guessed right about your reaction to the statement, then you share something very important and very problematic with Richard Spencer, who made the pronouncement about race at a National Policy Institute (NPI) convention in November. Spencer is the President and Director of NPI, “an independent organization dedicated to the heritage, identity, and future of people of European descent in the United States, and around the world.” He is the creator of the term “Alt-Right,” a new coinage for an old ideology of white supremacism, and he has stated unabashedly that America is “a white country,” created by whites who have no need for other inferior groups.

“Don’t you dare clump me with the likes of Richard Spencer!” you might be saying now. “I’m not a racist! Yes, I think of people as member of races, but for me that’s no different than thinking of people as tall or short, or any of the many ways that people naturally vary from one another, none of them implying inherent inequality. Racists are vile people who impute hierarchical differences to the idea of race, and use that rationale to oppress.”

I do not mean to offend. I mean only to provoke the realization that we have to stop believing and acting as if we can have it both ways: adhere to the notion of race while also trying to end racism. The scourge that is the latter is inextricably contingent on the former. Despite our best efforts to eradicate racism, it reemerges like a defiant toxic weed because we fail to pull it up by its root: the notion of race that Spencer and so many treat as real, crucial, and foundational to human identity.

Years ago, I came across an insight in an essay by sociologist, Donal Muir, that perfectly articulates the flaw in how most people think about racism. Muir distinguished three types of thinkers when it comes to racism: “mean racists,” “kind racists,” and “non-racists.” Mean racists and kind racists share a belief in the thesis articulated by Spencer. Mean racist see the thesis as an imperative to menace the racial other. Kind racists wish to ignore that the very essence of the idea of race is unequal worth, and they campaign for racial equality, effectively an oxymoron. The only people who qualify as non-racist are those who defy and denounce the false predicate of race altogether.

Race is not real. Race must cease to matter. Race is not a legitimate foundation of identity.

White supremacists, white nationalist, neo-Nazis, the Alt-Right, or whatever we choose to call mean racists, are, like all humans, driven to achieve consonance between their convictions and the shape, and functioning of the world. Their motivation is rooted in the belief that race is real, race matters, and race is the foundation of identity. We’ve failed to vanquish racism because kind racists are in a perpetual argument with mean racists about whose interpretation of the false declaration is accurate. What we need to do is disabuse them (and ourselves) of the delusion that catalyzes racist belief and behavior in the first place. Luckily, we have another thesis that can and should replace the faulty one about race.

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.” Despite the terrible truth that this declaration was hardly applied equally to every person (and with the necessary replacement of “men” with “people”), it is technically perfect, and it is perfectly incompatible with the idea of race that corrupted it before the ink had dried on our founding document.

Race is not real. Race must cease to matter. Race is not a legitimate foundation of identity.

Of course, many would fear that repudiating the concept of race would mean retreating from anti-racism and falling into dreaded colorblindness and a false sense of being post-race.

“In order to get beyond racism, we must first take account of race. There is no other way” (Regents of Univ. of California v. Bakke 438 U.S. 265 (1978)). This is what most people believe is necessary and what would be lost if we ceased to regard people in terms of race. But Supreme Court Justice Harry Blackmun’s precept was only half-right–necessary, but not sufficient.

The false notion of race was prescribed to allay the hypocrisy that was the by-product of our fledgling country’s virtuous aspiration to liberty and virulent addiction to slavery. The burden of that belief plunged us into a quicksand in which we continue to flail. To escape the trap–to truly get beyond racism, we must also get beyond race as a naturalized and compulsory social convention. To truly get beyond racism, we must do two things at once: monitor abuse based on the belief in race AND repudiate race as a legitimate basis of belief and behavior.

We can do this. We can walk and chew gum at the same time. We have to. There is no other way.

Featured Image Credit: “Fight Racism” by Metropolico.org. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Mean racist, kind racist, non-racist: which are you? appeared first on OUPblog.

John Glenn was a hero; was he a pioneer?

John Herschel Glenn passed away recently at age 95. He was the first American to orbit the Earth, on board Friendship 7 in February 1962, and before that, a much decorated war veteran, serving as a fighter pilot in both World War II and in Korea, finally retiring as a colonel in 1965. As if that wasn’t enough, after leaving NASA, he won a US Senate seat, representing his home state of Ohio, and served for 25 years.

John Glenn was certainly a hero. To some extent all astronauts are: what they do is so dangerous and requires such skill and dedication that few of us could qualify. As a planetary scientist, I am often asked if I had any ambition to fly in space: I always say no, I’d be terrified, especially of the launch. I have watched quite a few of those monster firecrackers take off, sometimes with my scientific experiments on board, and there is no way I would ever sit on top of one myself. I did once get the chance to stick my head inside the Apollo module that landed on the Moon, but that was in the factory that built them on Long Island, New York, in the 1960s.

On 20 February 1962, Astronaut John H. Glenn, Jr. piloted the Mercury-Atlas 6 “Friendship 7” spacecraft on the first manned orbital mission of the United States. Image by NASA. Public domain via NASA.gov.

On 20 February 1962, Astronaut John H. Glenn, Jr. piloted the Mercury-Atlas 6 “Friendship 7” spacecraft on the first manned orbital mission of the United States. Image by NASA. Public domain via NASA.gov.I was a student at the time, on a vacation course run by NASA. Later, I got to meet a couple of space shuttle pilots, and just last week I was there when Tim Peake came to the annual Appleton Space Conference held at the Harwell Science and Innovation Campus near Oxford. He was so, so impressive: not only had he risked his life on a trip fraught with danger, and performed complex tasks and experiments impeccably on the Space Station, he spoke about it all with a freshness and enthusiasm that made it impossible to believe that he must have given the same talk at least a thousand times. If he can inspire an old veteran like me, who has been involved in sending experiments to every planet in the Solar System, then youngsters just starting out with stars in their eyes must really be enchanted.

But where will they go? To a new permanent base on the Moon? To be one of the first humans on Mars? Even further afield, to the ocean worlds of Europa or Enceladus, where our Oxford-built instruments now orbit? The future of manned space flight is very uncertain. It is dangerous; it is expensive; it may even be useless in the sense of providing practical returns that justify, in terms of hard cash, the vast expense of going there with fragile, non-disposable payloads of human beings, most of whom would rather like to come back. Robots are tougher, and in many ways more capable, if rather less resourceful when something unexpected happens. Best of all, they don’t mind being left out there when their job is done; that, and their modest requirements for life support, make them a lot less expensive than astronauts like Glenn and those who follow him.

People ask me when humans will land on Mars. Will it actually happen during the lifetime of any of us, even the youngest? Will it ever happen, or will we succumb to war, overpopulation, or climate change, first? I tell them that it is as much up to them as it is to me, in fact I should be asking them. If the funding was there, we scientists would send manned missions to Mars like a shot. Most of us would not dream of going in person, if I am anything to go by, and I think I am; we’d have to find new people with the courage and vision of John Glenn to make the trip. Fortunately, they do exist. But whether to go is not really up to the scientists and astronauts. It is the politician and the taxpayer who will decide, by approving the expenditure, measured in hundreds of billions of whatever currency you care to name. We know how to do it technically, pretty much; but is it worth it, do we have the will to press ahead? How do you put a price on exploration, when you don’t know what you are going to find? And what will be John Glenn’s legacy, in the long term?

Featured image credit: International Space Station by Skeeze. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post John Glenn was a hero; was he a pioneer? appeared first on OUPblog.

Christmas on the radio

Back in 1944 the Archbishop of York, Cyril Garbett, wrote in the Radio Times that “the wireless and the English tongue are means by which God’s message of love and peace can spread through the world.” We may find it difficult these days to construe the BBC’s output over Christmas as taking on such a missiological flavour, but certainly in its early days Lord Reith, the first Director-General, saw religion as one of the four principal pillars which was to undergird the Corporation, the others being to cater to the majority of the public; to maintain public taste; and to provide a forum for impartial public debate, free from government interference. This led to what Simon Elmes identifies as the typical BBC Sunday: “a diet of services, religious talks, Bible stories, and histories of Christian heroes and martyrs, with little but the odd news bulletin and gardening programme to relieve the sabbatarian solemnity.”

Fast forward more than three quarters of a century, and at face value Reith would find little to object to in what the BBC offered its audience in Christmas 2015, as we learn from its Head of Religion & Ethics, Aaqil Ahmed, that “The BBC’s religious programming across TV and radio continues its fine tradition of bringing communities together and reflecting what is important to many of our viewers and listeners.” With Midnight Mass broadcast live on BBC One on Christmas Eve from St. George’s Cathedral in Southwark, to the Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols live on Radio 4 from the candlelit chapel of Kings College Cambridge, it is undoubtedly true that there are “many ways for audiences to take part and celebrate Christmas, be it via music, tradition, reflection, conversation or live worship.”

Is it necessarily the case, though, that a substantive definition of religion, whereby the presence of a core doctrinal or institutional manifestation of religion is being flagged up, is the best or even the only criteria for identifying and evaluating the extent to which the BBC is disseminating religion on its airwaves? It is the premise of Stewart Hoover’s Religion in the Media Age, for example, that “The realms of ‘religion’ and ‘media’ can no longer be easily separated”, as he sets about trying to “chart the ways that media and religion intermingle and collide in the cultural experience of media audiences.” For Hoover, “They occupy the same spaces, serve many of the same purposes, and invigorate the same practices in late modernity.” We see similar arguments evinced by Jeffrey Mahan who observes that “in post-modern communities, religion is multivalent and the wall between sacred and secular is clearly porous.” From the perspective of Implicit Religion, too, the late Edward Bailey claimed that “it must be one of the most assured results of religious studies… that it seems to be impossible to exclude any possibility as to the location of sacredness”, a point reinforced by Karen Lord who writes of the “interconnectedness of religious and quasi-religious behaviour in society, and the need to redraw previously accepted boundaries in order to enhance the analysis of such behaviour.” At the heart of such thinking is the notion that if we were simply to limit the study of religion to its institutional manifestations then, as Gordon Lynch puts it, this could “therefore blind us to some of the most pressing questions about the stories, values, and meanings that shape many people’s lives today.”

Vintage retro radio by LubosHouska. Public domain via Pixabay.

Vintage retro radio by LubosHouska. Public domain via Pixabay.Certainly, at Christmas today we need to revisit the role that radio has played in fomenting the sense of community and togetherness that was a staple of the early days of radio, when, as the Christmas 1951 edition of the Radio Times highlights, “The friendliness and joyfulness of Christmastide find their way into the BBC’s Christmas programme, at no other season is the broadcaster so closely in tune with his vast audience.”

In 2016, we might want to ask whether much of the BBC’s ‘secular’ output may be shaping the format and content of contemporary religion. The fandom generated each year by Christmas Junior Choice on BBC Radio 2, presented by the late Ed Stewart might, for instance, be no less fecund when it comes to exploring matters of faith, identity, beliefs, and values than programmes made within the auspices and remit of religious broadcasting. Listeners on Christmas Day 2015 wrote in to Stewpot, in what was to become his last programme before his death on 9 January this year, to say “Junior Choice has become a Christmas tradition for our family. We listen every year”, and that a record request for a song from one’s youth “instantly whisks me back to our happiest childhood Christmas days spent with [my mother] and my little brother, and whilst we are now all grown up doesn’t mean we don’t still treasure those memories.”

If, as Ninian Smart, the founder of Religious Studies in Britain, has suggested, there are plenty of people who “may see ultimate spiritual meaning… in relationships to other persons”, then Junior Choice might be a prime example of an alternative way of conceptualizing religion with its devotees who construe the two hours of nostalgia and reconnecting with the past on Christmas morning as a form of transcendent, even sacred, time. Might it even comprise no less of a commitment, even a ritual, than devotion to established religious traditions with its impact on several generations of radio listeners. Just think – next time you hear ‘Nellie the Elephant’ or ‘Sparky’s Magic Piano’ you might have unexpectedly encountered an instance of what Mazur and McCarthy identify as religious meaning being “found in activities that are often considered meaningless.” Religion may be intrinsic to the Christmas celebration, but might the festival’s secular components paradoxically amount to its most salient and fertile manifestation?

Featured image credit: Winter frost snow by sogard. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Christmas on the radio appeared first on OUPblog.

Top ten OUPblog posts of 2016 by the numbers

Our most-read blog posts of 2016 are… not published in 2016. Once again, for the third year in a row, Galileo, Cleopatra, and quantum theory dominated the traffic on the OUPblog. However, the 2016 posts that attracted the most pageviews ranged in subject from philosophy to literature, and from mathematics to law. As you might expect, people were also interested in learning more about Shakespeare and politics in 2016. Please find the top ten performing blog posts on the OUPblog in 2016 below:

#10 Is the mind just an accident of the universe?

Exploring the renaissance of Panpsychism in the 21st century.

#9 How do people read mathematics?

Why reading mathematical proofs is different from reading any other material and it takes years of training to perfect it.

#8 Top ten developments in international law in 2015

A round-up of what changed in international law in 2015.

#7 Top ten essential books for aspiring lawyers

A list of ten thought-provoking titles that new law students should endeavour to read.

#6 Philosophers of the year, quiz

A quiz testing your knowledge of key philosophers such as Plato, Aristotle, and Kant.

#5 How did Shakespeare originally sound?

How was Shakespeare originally pronounced? Test your knowledge with our quiz, and discover ‘original’ Shakespearean pronunciation.

#4 Philip K. Dick’s spiritual epiphany

Kyle Arnold discusses the effects of a possible spiritual epiphany on Philip K. Dick’s writing.

#3 The truth behind the restaurant industry

A quiz based on the often overlooked aspects of the restaurant industry.

#2 Ten underappreciated philosophers of the Islamic World

The philosophical contribution of Islamic culture often goes unacknowledged. This post shines a light on those philosophers who have been forgotten.

#1 What religion is Barrack Obama?

A post that questions the reliability of internet sources in the age of Google, and the benefits of search engines to religious historians.

Thank you for your continued support of the OUPblog. I wish you a happy new year and look forward to welcoming you back in 2017.

Featured image credit: Laptop. Photo by Slack. CC0 Public Domain via Pexels.

The post Top ten OUPblog posts of 2016 by the numbers appeared first on OUPblog.

What does myth have to do with the Christmas story?

There are two contrary ways of characterizing myth. By far the more common way is negative: a myth is a false or delusory belief or story. Here the aim is to expose the myth and be done with it. To take an innocuous example, the story that young George Washington was so honest that he could not deny to his father that he, the son, had chopped down the cherry tree is a myth because it never occurred.

Taken positively, a myth can still be false, but the significance of it when believed to be true is what counts. The story of Washington’s confessing that he had chopped down the tree attests to the character of the person even as a child. (An American comedian once contrasted Washington to Richard Nixon: we’ve gone, he said, from a President who could not tell a lie to a President who could not tell the truth.)

Viewed positively, a myth can as likely be true as be false. What matters, to use the line of Joseph Campbell, is the “power of myth.” But that power does not require that the myth actually be true. Yet myth need not be false. The power of myth transcends its factual status.

The phrase “Christmas myths” invariably uses the word negatively. What is false about Christmas ranges from the detailed to the fundamental. Strictly, Prince Albert of Victoria and Albert fame did not invent Christmas trees, which had been around the Court for almost a hundred years. More substantially, Christmas might have originally been a pagan holiday and one that centered on the sun. This argument is part of a broader claim that Christianity arose out of Roman religion.

Positively, what is Christmas about? Straightforwardly, it is the celebration of the birth of Jesus. (In two of the four canonical Gospels the birth takes place in Bethlehem. In a third it takes place in Nazareth. Only two of the Gospels place the birth in a manger.) The significance of the story is obvious: it recounts the birth of the savior of humanity.

Taken negatively, Christmas is a made-up story. Humans are not born of virgins. Miracles, such as Jesus’ spontaneously curing the blind, do not occur. Death is final. There is no return fare. Above all, Jesus was not the son of God, for there are no gods. Humanists, who pit myth and religion against science, relish amassing these beliefs as unscientific and therefore false.

Birth of Jesus by janeb13. Public domain via Pixabay.

Birth of Jesus by janeb13. Public domain via Pixabay.But there is an alternative positive reading — a secular one, one involving neither gods nor miracles. Here the celebration is of the winter solstice, or the shortest day of the year. The date fluctuates between 20 December and 23 December. But it is close enough to 25 December to be tied to the birth of Jesus. The celebration is thus of the forthcoming end of winter and coming of spring.

Who, then, is Jesus? Either the sun god or the sun itself. Or more likely, Jesus is either the god of vegetation or vegetation itself.

The counterpart to this seasonal approach to Christmas is the seasonal approach to Easter. Here Jesus is, again, either the god of vegetation or vegetation itself. As a god, his death and resurrection either symbolize or cause the death and rebirth of vegetation itself, the course of which coincides with Easter.

There are celebrations of the winter solstice all over the world. Pagans gather at Stonehenge, for example. And many Christmas customs, including trees and gift giving, doubtless hark back to pre-Christian times. (Apparently, our forebears especially liked getting electronic gifts, especially returnable ones.)

This approach to myth is comparative, as all theories of myth are. The key theorist here is James Frazer, author of The Golden Bough (1890, 1900, 1911-15). The significance of any myth is the significance of all myths of that kind, such as vegetation or solar myths. The birth of Jesus becomes simply the Christian version of a universal, or at least widespread, story of the birth of the god on all whom depend.

Taken cosmically, the birth of Jesus and of kindred figures worldwide is the birth, or rebirth, of the world itself. That in the Gospel of Matthew the wise men seeking Jesus’ birthplace follow the heavens for directions evinces the scale of the event. It is not merely Jesus who is being born. It is the world, as in the rebirth of the earth after the Flood in Genesis.

In a tamer form the birth of Jesus is merely being commemorated. In a bolder form it is being “redone.” Jesus is born anew every Christmas, dies every Good Friday, and is resurrected every Easter. Creation is not a merely one-time event but an annual one. Certainly the pagan, or seasonal, approach to Christmas makes the birth of the world a yearly enterprise. True, Jesus grows up, but he is still born anew when resurrected. There is a cycle of birth, death, and birth again.

Featured image credit: Christmas Glass ornament by mploscar. Public Domain via .

The post What does myth have to do with the Christmas story? appeared first on OUPblog.

December 22, 2016

Where next for dementia research?

Writing about the science of dementia has been different from any of my previous book projects in one rather sad respect. This time I have never had to explain the topic, or my choice of it. Dementia, once hidden in homes and institutions, has come out of the shadows. Almost everyone I know is afraid of it, and many have felt its impact on sufferers and their families.

Modern medicine has done well in helping Western citizens live longer. So have other changes like improved diets, better public hygiene, and less smoking. Dementia, which is primarily though not entirely age-related, has come to prominence in part as other lethal diseases have diminished. It recently surpassed heart disease as the number one killer in England and Wales (overall and in women, according to the UK Office for National Statistics). Dementia is also now being highlighted by charities convinced that, as with cancer before it, fear and stigma make patients’ and carers’ lives worse.

Charity campaigners also want dementia care and research to get much more funding. Diseases which affect brains tend to come off worse in the competition for resources, especially for charitable giving. As well as funds, researchers need volunteers for studies, including younger adults (if you are in the United Kingdom you can volunteer at Join Dementia Research). Dementia research needs all the help it can get, because this is an immensely challenging and complex problem to solve.

Just why is dementia so difficult? One reason is of course the sheer complexity of human brains. Dementia research must consider not only the interactions of billions of neurons and trillions of synapses, with all their proteins, lipids, ions, and genetic material, but also the roles of non-neuronal brain cells such as microglia, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes. There is still much to do, for instance, to sort out the contributions of cholesterol signalling, or understand whether, and when, microglia in neurodegenerative disorders are helping the brain and/or harming it.

Until recently we have not had the tools to assess the leading hypotheses about what underlies dementia in human beings.

Another reason, as so often in science, is to do with methods. Until recently we have not had the tools to assess the leading hypotheses about what underlies dementia in human beings. In addition, several of the brain regions which may be crucial early sites of damage in dementia are buried deep in the brain, making them hard to study. There has also been a chronic shortage of donor brains for pathological analysis.

Now, however, technical advances are having a gigantic impact on the field. New imaging techniques can ‘see’ key brain proteins, or changes in microglia, astrocytes, and the white matter which connects brain regions, in living people. Speedier mass analysis of genes and proteins has facilitated the search for mechanisms. Neuroimaging can look at functional connectivity – networking between different parts of the brain. And new ways of obtaining cell samples, such as making microglia from stem cells, look set to overcome many of the problems with older in vitro studies.

A third reason why dementia is so hard a challenge is that its science must extend beyond the brain: this condition is a whole-body disorder. Here again, considerable advances have been made lately in understanding how problems with other organs, such as the heart and pancreas, can push an ageing brain towards degeneration. Alongside this, we now have a much better understanding of the risk factors which may raise our chances of getting dementia in old age.

Perhaps the most important conclusion to have emerged from research so far is that the processes underlying dementia seem to start long before the disorder becomes apparent. Very long before: decades, not years. That is a huge problem for any cure – should one emerge from the clinical trials currently in progress – because new drugs are usually extremely expensive. Given how many people are at risk of dementia, the costs of having to treat them all for, say, 20 years before symptoms appear – and it might be longer – are unaffordable. And if the drugs have unpleasant side effects, the prospect for patients isn’t great either.

Yet thinking of dementia as a whole-body condition brings the hope that looking after our physical health can help stave off later problems. For now, we cannot cure dementia. We can however try to delay it until, to be blunt, we die of something else. Research suggests that dementia rates may already be leveling off in Britain and Europe because fewer people are smoking and getting heart disease. Eating healthily, taking plenty of exercise, staying sociable … all the familiar things we’re told to do to keep our hearts in good condition apply to our brains as well, and more so as we age.

Lifestyle changes aren’t easy. While we await a cure, though, they’re our best hope of avoiding the shadows of dementia.

Featured image credit: Neurons by geralt. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Where next for dementia research? appeared first on OUPblog.

Looking at the stars

The ancient Greek philosophers believed that the Sun, Moon, planets, and stars were mathematically perfect orbs, made from unearthly materials. These bodies were believed to move on perfectly symmetric celestial spheres, through which a backdrop of fixed stars could be seen, rotating majestically every 24 hours. At the centre was the motionless Earth. For the Greeks, the power of reason was more important than observation. Some 2000 years later, this was the prevailing cosmology when the telescope appeared on the stage.

A simple spyglass, consisting of two lenses held in sliding tubes, emerged from the European eyeglass lens-making industry, sometime in the 16th century. Initially the instrument had limited capability but, in the hands of one genius, Galileo Galilei, it soon began to deliver breath-taking views of the cosmos, imperfections of the heavenly bodies, and crucial evidence supporting Nicolaus Copernicus’ earlier model of a heliocentric system, placing the Sun at the centre of a whirling velodrome of planets.

Technology and curiosity were then harnessed, elevating the telescope to higher degrees of size, power, and perfection to create scientific instruments that would come to revolutionize our understanding of the Universe. Cameras and spectrographs were attached to record what could not be seen by eye and to split starlight into its rainbow colours. Stellar spectra reveal the chemistry of the stars, their temperatures, their rotations, and their motions. Crucially it showed that stars were made out of the same types of atoms that are found on Earth, heralding the birth of astrophysics.

Just over 100 years ago, we believed that our star, the Sun, lay in a cluster of stars, which defined the observable Universe. But when astronomers like Edwin Hubble pointed big telescopes to look out beyond our Galaxy, the Milky Way, they found a seemingly endless ocean of space and time, with billions of other galaxies embedded in it, all rushing apart from us and from each other. The Hubble expansion showed that the Universe is highly dynamic and that it started with a Big Bang, 13.8 billion years ago.

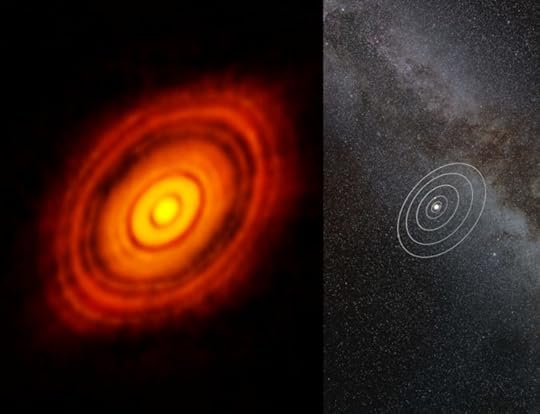

Traces of a faint cosmic microwave background radiation, the ubiquitous relic of the Big Bang, were discovered in the 1960s. Other radio telescopes discovered exotic objects like pulsars and the high-energy processes taking place in the hearts of galaxies, where supermassive black holes gobble up matter. Freed from the blurring and blocking effects of the Earth’s atmosphere, space telescopes, like the Hubble Space Telescope, and others at g-ray, X-ray, ultraviolet, and infrared wavelengths began observing high-energy processes and the formation of stars and planetary systems in giant clouds of cold interstellar gas. One of theses, a young star called HL Tauri, 400 light years away, was recently caught in the act of giving birth to a new planetary system by the Atacama Large Millimetre Array (ALMA) telescope in the Chilean desert. In this image, the newly born sun is seen to lie clearly in the middle of its nascent planetary system.

HL Tauri: a young star and forming planetary system seen by the ALMA telescope. On the right is our own solar system at the same scale; the outer planet is Neptune, by ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO). Used with permission.

HL Tauri: a young star and forming planetary system seen by the ALMA telescope. On the right is our own solar system at the same scale; the outer planet is Neptune, by ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO). Used with permission.A new generation of highly sophisticated telescopes will soon come into operation. These instruments will augment and extend those already gathering immense volumes of multidimensional data, turning the flow into torrent. The challenge of discovering new science in a tsunami of complex data is spawning an actively growing area: data science. The problem is akin to finding tiny needles in giant haystacks. Possible solutions include harnessing the eyes and brains of millions of volunteer citizen scientists, the use of advanced data visualisation techniques, and the training of computers to seek out the unexpected.

The next telescopes, straining at the limits of what is technically possible, will target key questions: what is the nature of dark matter; what is dark energy; how did the first galaxies form; and are there habitable Earth-like exoplanets? The last question is a tremendously exciting one because it includes the search for biomarkers – evidence of the molecules of prebiotic life in the atmospheres of exoplanets. Will the next generation of telescopes tell us that we are not alone in the Universe?

Featured image credit: Stars by Geoff Cottrell. Used with permission.

The post Looking at the stars appeared first on OUPblog.

The American Colonization Society’s plans for abolishing slavery

This month marks two hundred years since the founding of an organization that most people have never heard of: the American Colonization Society (ACS). The obscurity into which it has fallen would surprise Americans living in the decades before the Civil War. From its founding in 1816 until the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, the Society rallied some of the most influential people in the United States behind its principal objective: to persuade African Americans to leave the United States and settle in an overseas colony. In 1821, with a crucial assist from President James Monroe, the ACS acquired land in West Africa for its new settlement of Liberia. Over the following four decades, Colonization Society officials worked to expand their colony, and to persuade white and black Americans that the long-term solution to slavery was an epic form of racial separation.

At first glance, colonization seems part of the other forms of racism that structured American life before the Civil War. But colonization rhetoric was considerably more slippery than it might initially seem. For one thing, advocates of colonization – unlike defenders of slavery – largely avoided the claim that black people were permanently inferior to whites. In fact, the overwhelming majority of colonization advocates insisted that the institution of slavery was immoral, impolitic, or both. Even before the founding of the ACS in 1816, the idea of separating the races had become ubiquitous in proposals for abolition. It was pioneered by Thomas Jefferson in the 1780s, and became a mainstay of the so-called “first wave” of abolition activism in the 1790s and 1800s.

This sustained interest in black colonization betrayed a real anxiety among white Americans – even those who styled themselves as liberal and benevolent – about the difficulties they had of living alongside people of colour as equals. This was a problem that confronted the new United States with a particular force. When British and French campaigners attacked the slave trade, they did so in the knowledge that black people in the Caribbean would eventually receive freedom an ocean away from the metropolis. No French or British campaigner expected to live alongside black people in equality. Slavery was much more closely coiled around American society: free blacks formed a significant minority (10-15%) in many northern cities by 1810, while slaves comprised more than 30% of the population in Virginia, and close to a majority of the population in South Carolina and Georgia.

The demography of Caribbean slavery – with tiny white elites living amidst overwhelmingly black populations – was replicated in certain regions of the southern states, but no single state looked like Barbados or Jamaica or Haiti. Instead, black people made up between a quarter and a half of the population of most southern states. To white people who thought seriously about slavery before 1860, this meant that only three futures were possible: African Americans would be kept in slavery, with the associated dangers and moral burdens; they would be freed and given their rightful share of “all men are created equal”; or they would be freed and “colonized” beyond the borders of the United States.

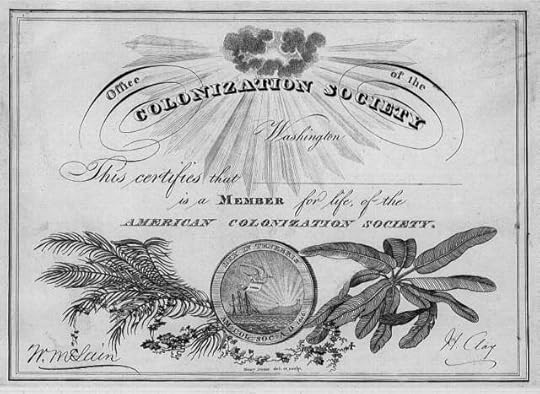

Member certificate of the American Colonization Society, ca. 1840 by Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Member certificate of the American Colonization Society, ca. 1840 by Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.With the advent of the cotton boom after 1820, increasing numbers of southern whites chose the first option. Developing arguments that styled slavery as a positive good in turn radicalized a new generation of abolitionist activists (mostly in the northern states) who insisted on the need for immediate and unconditional abolition. From the 1830s onwards, these two sides entered an open battle which, with the benefit of hindsight, anticipated the Civil War: Northerners argued for the need to destroy the slave system, and Southerners insisted that the rights of property (and the inferiority of African Americans) were incontrovertible. It’s important to put colonization back into the story precisely because it complicates this simple antagonism. The overwhelming majority of white northerners rejected immediate abolition, juggling a variety of neuroses and prejudices about the prospect of black equality. In the 1850s, figures as diverse as Abraham Lincoln and Harriet Beecher Stowe promoted racial separation as an important tool for securing the destruction of slavery. Even while Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison dismissed colonization as a pipe dream, leading politicians like Daniel Webster and Henry Clay presented the removal of black people as a prudent and reasonable prerequisite for slavery’s demise.

What made this commitment to colonization more surprising was the steadfast opposition of African Americans to the inducements and rhetoric of the American Colonization Society. The idea that black people might have to leave the United States to assert their rights and sovereignty predated the founding of the ACS in 1816; it was a black idea before it was appropriated by white ‘moderates’, and it continued to inspire black nationalists in the decades after the Civil War. But it was black opposition, more than any other single factor, which served to frustrate both the Colonization Society and the infant colony of Liberia in the decades before the Civil War. While liberal whites insisted that black people didn’t know what was in their best interest, African Americans from every part of the United States – even southern slaves – relayed the message that they would not accept white-imposed exile as a condition of freedom. This response was broadly consistent from 1817, when ACS officials were shouted down at a public meeting of free blacks in Philadelphia, to 1862, when Abraham Lincoln earned a furious response from Frederick Douglass for promoting black removal to Central America. African Americans may have recognized that slavery was the nation’s principal evil, but they were loath to accept expatriation as the means of overcoming it.

It’s ironic that colonization seemed the most responsible way for white ‘moderates’ to package their distaste for slavery before 1861. The course of the Civil War, and Abraham Lincoln’s acceptance after 1863 that colonization was chimerical, have made it easy for historians to sideline the American Colonization Society and the many related proposals for racial separation in the United States at that time. In popular memory, the slavery struggle pits radical abolitionists (black and white) against fire-eating slaveholders – a conflict that eventually tipped the nation into Civil War. While this version of American history captures the crucial point that white Northerners and Southerners became increasingly divided over slavery, it overlooks the accompanying fact that very few white people in the North or the South were committed to black citizenship. Colonization enabled white Northerners to oppose slavery without any commitment to integration and equality. Its proposals failed not because of a moral epiphany on the part of white Americans, but because so few black people proved willing to validate its rhetoric of benevolent segregation.

Featured image credit: An etching of Cape Palmas, Liberia in 1853 by Libreria past and present. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The American Colonization Society’s plans for abolishing slavery appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers