Oxford University Press's Blog, page 423

January 1, 2017

The visual poetry of documentarian Frederick Wiseman

After six decades and 43 films, Frederick Wiseman, whom Pauline Kael years ago called “the most sophisticated intelligence in documentary,” is now enjoying more attention than ever before. He was honored with a complete retrospective of his films at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 2010, accompanied by a handsomely produced and illustrated book. In Los Angeles, Cinefamily also is honoring Wiseman with a comprehensive four-year retrospective that includes three newly restored 35mm prints (Titicut Follies [1967], High School [1968], and Hospital [1970]). He also received an Honorary Award (Governors’ Award) from the Academy in November, along with Jackie Chan, editor Anne Coates, and casting director Lynn Stallmaster.

Wiseman’s films are often, yet mistakenly, grouped with his contemporaries Richard Leacock, D.A. Pennebaker, and Albert and David Maysles as part of the American direct cinema movement of the 1960s and 70s. These filmmakers, like Wiseman, were using recently developed lightweight, portable 16mm cameras with synchronized sound recording equipment to capture events spontaneously, but there the similarity to Wiseman ends. The direct cinema film makers aspired to be, in Leacock’s famous phrase, a “fly-on-the-wall”: to observe, follow, and capture events as they happened without a script. This approach was, in the words of Soviet film theorist Dziga Vertov, “life caught unawares” by the camera eye, an unblinking, impartial witness that would reveal deeper truths about the world displayed before it.

Wiseman’s films are distinctly different. Where direct cinema tended to focus on charismatic individuals in crisis situations, Wiseman’s films, anticipating the cycle of “network narratives,” take as their subject American institutional life, revealing, in the words of Richard Brody, “the rules and the exercise and negotiation of power behind the surfaces of daily life.”

Further, while the direct cinema filmmakers insisted that their films must be structured chronologically in order to remain as faithful as possible to the pro-filmic events they have recorded, Wiseman’s films are clearly structured according to principles other than chronology, using rhetorical strategies such as contrast, similarity, analogy, metonymy, and irony. This temporal shuffling for aesthetic and thematic purposes is evident from Wiseman’s first documentary, the controversial Titicut Follies, which begins and ends by showing parts of the same annual musical show mounted by the inmates of Bridgewater and suggesting that everything in between is an inescapable nightmare involving social performance.

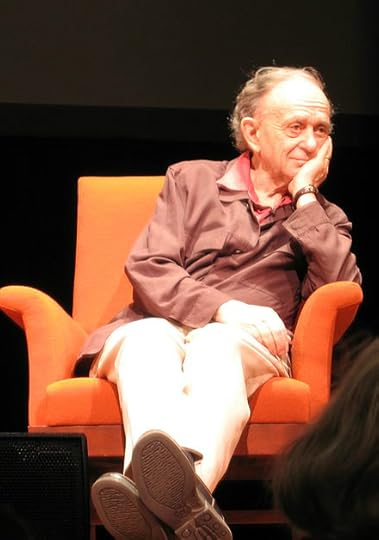

Frederick Wiseman in 2005. Picture by Charles Hayes, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Frederick Wiseman in 2005. Picture by Charles Hayes, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Wiseman himself is dismissive of the very idea of direct cinema’s ideal objectivity, or that his films are examples of it. Primate [1974], about the Yerkes Primate Research Center in Atlanta, is in part a joke about direct cinema, with his camera observing and framing the fly-on-the-wall scientist observers, taking a wider view than theirs. Wiseman readily admits the creative manipulation in his work in his own description of his films as “reality dreams” or “reality fictions.” He lists himself as director in the credits of his films, and has insisted that “When you’re signing the film, you are saying it’s your film, this is the way you see it.”

Although Wiseman’s films never feature a narrator, either within the film or as voice-over to explain or contextualize what we see, his authorial voice is always present, both at the level of the shot and in overall structure. His images consistently seize upon objects and physical details in the institutions he films and invests them with significance beyond their functional purposes. His images are charged with meaning beyond the literal to an extent that can only be called poetic. Like William Carlos Williams, Wiseman knows how much depends upon observing a red wheel barrow beside the white chickens glazed with rainwater.

In Wiseman’s documentaries the institutions are themselves treated symbolically (Wiseman calls them “cultural spoors”), with the films employing textual strategies that force the viewer to understand them as social microcosms, as interwoven parts of the larger social fabric. Like all the institutions Mr. Wiseman has examined – whether publicly funded ones like hospitals, schools, and courts; or cultural ones like advertising, retail sales, and ballet companies – they are shown to have their own logic, a logic which fuels the institution’s operational processes.

Crucially, Wiseman’s attitude toward institutions has shifted over the years, moving, broadly speaking, from exposé to empathy. In earlier films people were seen as victims of institutional practices; more recently they are more accepting of the people within institutions and even of the institutions themselves.

The love and openness that characterize Essene (1972) and the four films of the Deaf and Blind series (1986) have become prominent in more recent work. Belfast, Maine (1999) is a magisterial work that discovers aspects of many of the institutions Wiseman had examined in earlier films at work in the eponymous New England town even as it embraces the range of people who live there. The subject of domestic violence was important enough to Wiseman to devote two films to it (Domestic Violence [2001] and Domestic Violence 2 [2002]). And his most recent film, In Jackson Heights (2015), is a celebration of harmonious racial, ethnic, and religious difference in a neighborhood that proudly advertises itself as the most ethnically diverse in the world.

Animated by the same expansive and generous spirit that informs these films, Wiseman has become more involved in the other arts. Recent films have focused on dance — Ballet (1995), La Danse—Le Ballet de l’Opèra de Paris (2009), Crazy Horse (2011), and perhaps even Boxing Gym (2010) — and painting (National Gallery), which cleverly uses the gallery tour guide’s discussions of famous paintings to comment on his own filmmaking practice. Currently Wiseman is collaborating with James Sewell and the Minnesota Ballet Company on a ballet of Titicut Follies, hardly a subject that would leap to mind for such an adaptation (he already had collaborated on Welfare: The Opera in 1997).

Looking for an upbeat interpretation of King Lear, a teacher in High School II (1994) says about the ruler’s relationship with his daughter Cordelia that it was “a different kind of love. It’s very interesting how kinds” of love may be found in the play. This is becoming true of Wiseman’s own films as well. It is perfectly appropriate, therefore, that Wiseman’s work is now being embraced more widely in return.

Featured image credit: 16mm film reel from DRs Kulturarvsprojekt, (archive of Danish Broadcasting Corporation). CC-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The visual poetry of documentarian Frederick Wiseman appeared first on OUPblog.

New Year’s Day through the ages

How are you spending New Year’s Day this year? If your mind has turned to resolutions and plans for the coming months, a creative fresh start, or even if you’ve got a touch of the January blues, then you’re in good company. Some of our greatest writers and thinkers have found themselves in exactly the same predicament. To mark the start of 2017, we’ve taken a snapshot of poems, novels, and letters from famed literary and historical figures, all composed on January 1st.

On the same day, years apart, Frances Burney is turning her mind to resolutions, to “content myself calmly—unresistingly, at least, with my destiny,” whilst Edmund Burke is “perfectly unhappy” and concerned with the “capital of my fame.” Jeremy Bentham wonders what he should do about the mysterious “things” whilst Charles I is proclaiming the relocation of the Court of the King’s Bench to Oxford.

From Charles Dickens‘ health advice to William Cowper’s misplaced venison, discover the 1st of January as you’ve never seen (or read) it before…

Featured Image Credit: “Garibaldi Provincial Park January 2009” by Jennifer C. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post New Year’s Day through the ages appeared first on OUPblog.

December 31, 2016

Dragons, chimney sweeps, and grapes: New Year’s traditions around the globe

The advent of new technology and endless sources of instant transcontinental news has allowed the human race to be intricately connected, now more than ever. We asked staff across Oxford University Press to describe their New Year’s traditions, celebrating their culture, background, and ancestry. As we welcome the New Year, we also commemorate our differences and customs.

* * * * *

“Bleigießen, a type of fortune telling, is a favourite New Year’s activity in Germany (molybdomancy is probably the translation that comes closest). You melt a small chunk of lead (or wax or tin) over a candle, then quickly pour it into a bowl of cold water. The hardened shape (or its shadow) is then interpreted to predict that person’s future in the coming year.

“Many Germans prepare and drink Feuerzangenbowle (literary “fire tongs punch”) on New Year’s Eve. Preparing this drink is a ritual and part of the fun so for many, it’s as important as the drinking. A rum-soaked sugar loaf is set on fire so the caramelized sugar drips into spiced red wine (mulled wine) which is usually suspended over a ‘rechaud.’ The drink’s popularity was raised by a German book and subsequent film called Die Feuerzangenbowle.”

— Anne Ziebart, Senior Marketing Executive

* * * * *

“New Year’s Day is family time in Japan, like Christmas in the UK. We have a special lunchbox, alcohol in the morning, and visit a shrine. We eat soba noodles on 31 December, wishing to live longer. We give a little bit of money to kids on New Year’s Day, wishing happiness and wealth in the year.”

— Yuka Saito, Portfolio Marketing Executive

* * * * *

“I’m Dutch and in the Netherlands we eat ‘oliebollen.’ I also lived in Germany for a long time and call that home. Their New Year’s is called Silvester. People gift others marzipan Schornsteinfeger (chimney sweepers) or a Glücksschwein, as they’re used to wish someone good luck.”

— Franca Driessen, Senior Marketing Executive

* * * * *

“Lion Dance Confetti” by Kurt Bauschardt. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

“Lion Dance Confetti” by Kurt Bauschardt. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.“Growing up in Colombia, there were many traditions we adhered to on New Year’s Day. One of them included wearing yellow underwear to represent gold and wealth. My family and I always had twelve grapes in hand and had to eat them all up as soon as twelve o’clock hit, while making a wish for the upcoming year.

“Another tradition is ‘Año Viejo’, literally meaning the ‘Old Year’, which consists of creating a life size doll out of clothes and newspaper, and setting it on fire before midnight, signifying good-bye to the old year and welcoming the next one. Once all this is done, you’d grab a luggage and quickly run around the block to ensure there’d be lots of traveling in the upcoming year. This was my favorite part as a child, as neighbors would typically wave and wish you safe travels from their homes.”

— Estefania Ospina, Social Media Marketing Coordinator

* * * * *

“In the UK, people often go for a swim in the sea on New Year’s Day – especially in places like Dover and Cornwall, but in northern parts of the UK too. Another great British New Year tradition is the ‘start as you mean to go on’ run, which usually takes place on the morning of New Year’s Day within a group of friends who have all made a resolution to get fit, eat well, and drink less. The New Year’s Jog is followed immediately by a large brunch and the signing up of the entire party to the local gym. Many will attend religiously throughout January, though come February the treadmills will be still and the changing rooms deserted.”

— Katie Stileman, Publicity Assistant

* * * * *

“Although the Chinese New Year is not until 28 January this year on the Gregorian calendar, there are a myriad of traditions that people are already looking forward to in celebration of the event. One of the most recognizable traditions is lion or dragon dancing. The fearsome faces of the lions and dragons, combined with the loud beating of drums and gongs, are thought to ward off evil spirits.

On Chinese New Year, red is worn as it is traditionally believed to bring wealth and good fortune. Red envelopes with crisp new bills are even given out to children and unmarried individuals on this day. Last but not least, food and family plays an important role on Chinese New Year: on New Year’s Eve, families gather for feasts at the home of the most senior member of the family and enjoy a spread that includes chicken, pork, noodles, and fish.”

— Priscilla Yu, Social Media Marketing Coordinator

* * * * *

Featured Image Credit: Mooncake Festival Fireworks (Melbourne) by Chris Phutully. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Dragons, chimney sweeps, and grapes: New Year’s traditions around the globe appeared first on OUPblog.

December 30, 2016

Quoting the New Year and lessons from the past

“Year’s end is neither an end nor a beginning but a going on, with all the wisdom that experience can instill in us,” once said American author Hal Borland. New Year’s for him was simply an extension of the previous year. The New Year – and what it brings with it – can be interpreted in many different ways.

For many, this is a time of reflection and celebration, and in anticipation of the New Year, we have compiled a list of historical quotes pertaining to new beginnings, a new era, or a clean slate:

“The year which is drawing toward its close has been filled with the blessings of fruitful fields and healthful skies.”

– Abraham Lincoln, US President (1809–65)

**********

“This is the day upon which we are reminded of what we are on the other three hundred and sixty-four.”

– Mark Twain, American writer (1835–1910)

**********

“Ring out the old, ring in the new,

Ring, happy bells, across the snow:

The year is going, let him go;

Ring out the false, ring in the true.”

– Alfred, Lord Tennyson, English poet (1809–92)

**********

“Tonight’s December thirty-first,

Something is about to burst…

Hark, it’s midnight, children dear.

Duck! Here comes another year!

Across East River in the night

Manhattan is ablaze with light.

No shadow dares to criticize

The popular festivities.

Hard liquor causes everywhere

A general détente, and Care

For this state function of Good Will

Is diplomatically ill;

The Old Year dies a noisy death.”

– Ogden Nash, American humorist (1902–71)

**********

“Time has no divisions to mark its passage, there is never a thunderstorm or blare of trumpets to announce the beginning of a new month or year. Even when a new century begins it is only we mortals who ring bells and fire off pistols.”

– Thoman Mann, German novelist (1875–1955)

**********

“The ability to foretell what is going to happen tomorrow, next week, next month, and next year. And to have the ability afterwards to explain why it didn’t happen.”

– Winston Churchill, British politician and statesman (1874–1965)

**********

“It has ever been, and ever will be, permitted to issue words stamped with the mint-mark of the day. As forests change their leaves with each year’s decline, and the earliest drop off: so with words, the old race dies, and like the young of human kind, the new-born bloom and thrive.”

– Horace (Quintus Horatius Flaccus), Roman poet (65–8 BC)

**********

“When daffodils begin to peer,

With heigh! the doxy, over the dale,

Why, then comes in the sweet o’ the year.”

– William Shakespeare, English dramatist (1564–1616)

**********

“Men ever had, and ever will have leave,

To coin new words well suited to the age:

Words are like leaves, some wither every year,

And every year a younger race succeeds.”

– Wentworth Dillon, Lord Roscommon, Irish poet and critic (1633–85)

**********

“Youth is when you are allowed to stay up late on New Year’s Eve. Middle age is when you are forced to.”

– Bill Vaughan, American columnist (1915–77)

**********

“Now is the accepted time to make your regular annual good resolutions. Next week you can begin paving hell with them as usual.”

– Mark Twain, American writer (1835–1910)

**********

Featured image credit: “Notebook” by Pexels. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Quoting the New Year and lessons from the past appeared first on OUPblog.

On duty with the disease detectives

The recent confirmation that Zika virus is spreading in the southern states of the United States has been met with considerable public anxiety. Infectious diseases strike a particular primal fear in populations, not least because they are perceived to be unfamiliar, strike suddenly and unpredictably, and have strong cultural associations with filth, contagion, or nuisance vectors such as mosquitoes. In our technology-driven society, words like “infection”, “outbreak”, “epidemic”, and “plague” seem to hark back to a time when humans were at the mercy of the natural world. Surely by now modern medicine should have sorted this out?

Health protection doctors and nurses are familiar faces on the frontline of the response to the Zika epidemic, and have had high profile roles in other recent outbreaks such as Ebola, measles, and pandemic flu. Less widely known however is their day-to-day role in detecting and responding to local infections and outbreaks. For example, timely action to provide antibiotics and vaccination to university students who have been in contact with a case of meningitis infection may prevent further tragic cases. Identification of the source of contaminated food at a wedding vomiting outbreak could prevent other couples having their special day ruined.

Health protection professionals are often called “disease detectives”. The comparison is apt: they have to be highly skilled in gathering and appraising rapidly-emerging evidence, making high-pressure decisions with imperfect information, and in coordinating action from multiple different agencies and individuals. The real world is messy: information is often incomplete, especially in the first few cases of an outbreak, and quick action is needed.

Mutirão de combate ao mosquito Aedes Aegypti no Grupamento de Fuzileiros Navais de Brasília (Efforts to combat the Aedes Aegypti mosquito in the Brazilian Marine Corp) by Ministério da Defesa. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Mutirão de combate ao mosquito Aedes Aegypti no Grupamento de Fuzileiros Navais de Brasília (Efforts to combat the Aedes Aegypti mosquito in the Brazilian Marine Corp) by Ministério da Defesa. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Disease detective work is not limited to infections. The same skills that help public health professionals to detect and respond to infections can be used with other threats to health. Such threats include fires or floods and pollution of air or land, indeed, almost any environmental threat that affects a community in some way.

Most family and hospital doctors will only very rarely see an infection that requires urgent public health action. For example, in the United Kingdom, it would be unusual for a general practitioner to see more than one individual with the feared meningococcal disease during their whole career. When the unusual does strike however, they need to be able to quickly investigate and identify, then act rapidly and effectively. If action is delayed, public health officials will always be swimming upstream trying to catch-up with rapidly escalating numbers of exposed and unwell people.

The importance of easy and timely access to relevant information continues to be demonstrated time and again with national and international infectious disease incidents, such as the outbreaks of Ebola in West Africa and the spread of Zika in South America. Detailed infectious diseases plans and guidelines are invaluable for front-line healthcare professionals and alike, but in a time constrained environment with competing pressures, simpler tools which provide clear and succinct information come into their own. Practically focused, topic specific checklists with essential actions for clinicians and public health workers (including those without a medical background) make it much easier to ensure a timely and appropriate response. Access to user-friendly information is key to demystifying health protection work – ensuring that everyone is empowered to play his or her role in protecting the public from threats to their health and inspiring others to enter the exciting and fascinating world of the disease detectives.

Featured image credit: Pictured are two researchers looking at slides of cultures of cells that make monoclonal antibodies. These are grown in a lab and the researchers are analyzing the products to select the most promising of them. Image by Linda Bartlett, The National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Visuals Online. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post On duty with the disease detectives appeared first on OUPblog.

Why is home so important to us?

“Be it ever so humble, there’s no place like home.” “Home is where the heart is.” These well-known expressions indicate that home is somewhere that is both desirable and that exists in the mind’s eye as much as in a particular physical location. Across cultures and over the centuries people of varied means have made homes for themselves and for those they care about. Humans have clearly evolved to be home builders, homemakers, and home-nesters. Dwellings that are recognizable as homes have been found everywhere that archaeologists and anthropologists have looked, representing every era of history and prehistory.

Home has always been a gathering place, shelter, and sanctuary, providing escape from the busyness and intrusiveness of the world. Much thought about, treasured, and longed for as an anchor of our existence, home has been the subject of abundant written works and other cultural products. We might reasonably suppose, therefore, that home is a readily understood concept and source of universally positive feelings. On closer investigation, however, neither of these assumptions is found to be true. The concept of home is constructed differently by different languages; dwellings are built and lived in very differently by diverse groups; and many individuals have negative or mixed emotions in regard to their experiences of home life. To embrace all of the nuances of meaning, outlook, lifestyle, and feeling that attach to home is a daunting task, but it greatly enriches our perspective on the world.

For many, home is (or was) a loving, supportive environment in which to grow up and discover oneself. Most people will have more than one home in a lifetime, and if the original one was unhappy, there is always the opportunity to do better when creating a new home. This may not as easy as it sounds for those whose memory of home is of an oppressive or abusive situation from which escape is (or was) a desperate imperative. But even when it is a peaceful, loving environment, home is, for all of us, a political sphere wherein we must negotiate rights and privileges, make compromises, and seek empowerment through self-affirmation.

As an ideal that exists in the imagination, and in dreams and wish fulfilments, home carries many and varied symbolic meanings embedded in the physical design of houses and projected onto them by the belief systems within which our lives play out. The landscape, geopolitical location, the people who live with us, and material possessions with which we furnish our home space are essential aspects of the place where we dwell. Complex interactions with all of these elements give definition to home as we see it. And as we define home, we also define ourselves in relation to it.

Paris City homelessness by tpsdave. Public domain via Pixabay.

Paris City homelessness by tpsdave. Public domain via Pixabay.In recent times, home has become a more problematic notion, not only because of everyday encounters with our homeless fellow citizens, but also because of the great increase in immigrants, refugees, asylum-seekers, and victims of natural disasters in many parts of the world. Given the strong meanings and emotional associations that home has for us, those who have lost their homes and the things they most valued, or who have never had a proper home in the first place, face psychological impacts and identity crises of massive proportions. Being without a home is devastating on personal, social, and many other levels. The issues raised by homelessness exist on a world scale, and will be aggravated by climate change and rising populations. In the end, they can only be dealt with through united effort driven by compassion and dedication.

On the hopeful side of things, many immigrants have been welcomed into new countries for some time, and have made successful and rewarding lives there for themselves, as well as broadening the experience and culture of their adopted homelands. Living in the space age and the age of greater environmental awareness, we are also collectively making the first steps toward appreciating the Earth we share as our ultimate home, and as the place above all that we need to respect and protect. Thinking about home takes us into our inner selves, to be sure, but it also encourages us to look at things in their totality.

Why is home so important to us, then? Because for better or worse, by presence or absence, it is a crucial point of reference—in memory, feeling, and imagination—for inventing the story of ourselves, our life-narrative, for understanding our place in time. But it is also a vital link through which we connect with others and with the world and the universe at large.

Featured image credit: Home building residence by image4you. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Why is home so important to us? appeared first on OUPblog.

December 29, 2016

Dilemmas of a broken substance abuse system

With rising health care expenses, we are all trying to solve the paradoxical dilemma of finding ways to develop better, more comprehensive health care systems at an affordable cost. To be successful, we need to tackle one of the most expensive health problems we face, alcohol and drug abuse, which costs us approximately $428 billion annually. Comparatively, the expenses of health care services, medications, and lost productivity for heart disease costs $316 billion per year. In addition to economic costs, none of us are spared the ravages of this disease, due to addictions among our friends, family, workers or co-workers. Addictions are the most prevalent mental health disorders, afflicting about 8-9% of the US population. Yet the vast majority—an estimated 90% of those with a substance use disorder—do not receive any formal treatment services. In addition, the majority of those 10% who do receive formal services for substance abuse have been treated previously, and therefore, even those who do get treated for their addiction often do not attain recovery. Something has to change, as our current substance abuse health care system is both expensive and ineffective.

The fact is that millions of Americans are not receiving help for their substance use problems, nor are the current treatment programs consistently producing long term successes. We as a nation need to overcome our denial of our country’s high levels of problematic alcohol and drug use. Simplistic solutions of just saying “no” have been unsuccessful and unwittingly wrecked havoc on our citizens. Rather, we endorse a comprehensive campaign to highlight the extent of our nations’ addiction to mind altering substances, a movement to develop norms that increase an awareness when self-management of occasional use fails, an undertaking to overcome barriers in seeking the help that is needed, and critical efforts to increase the effectiveness of treatment and after-care programs.

Bold new initiatives will be needed to solve these problems on a more systemic and sustainable basis, and below are a few of our thoughts for change.

Aligned with more universal efforts of facilitating self-awareness of problem behaviors, efforts should be made to identify and reduce risks with settings that promote use. This especially includes settings that perpetuate self-defeating and destructive influences on our youth and young adults, for example, college freshman binge drinking.

We all have a role in abolishing barriers for someone seeking help and this includes reducing the stigma of substance use disorder.

As a universal prevention effort, all citizens can be responsible for helping those at risk for substance use disorders. The majority of people who use legal substances like alcohol and prescription drugs do so without endangering their health or that of their family members and friends. Early prevention efforts should focus on the trajectory of problematic use and building awareness for self-screening and use management. For some individuals, however, self-management fails, and their alcohol and drug use can become harmful. Collectively, we should promote acting early to prevent addictions, and begin a dialogue with loved ones when such patterns are observed. Family members, friends, and work associates must recognize and change often unconscious subtle actions that unwittingly promote and enable harmful use of substances by their loved ones. Rather than condoning or even encouraging reckless drinking or drugging, and waiting until problems are more entrenched and less resistant to change, loved ones have a responsibility to take action (e.g., changing social activities from bar hopping to art gallery hopping) before a more formal treatment is necessary. Other activities might involve attending self-help groups, making referrals, and searching for appropriate resources in a proactive way.

We all have a role in abolishing barriers for someone seeking help and this includes reducing the stigma of substance use disorder. Taking the first recovery step is emotionally difficult for those troubled with addictions. Often, those who have recognized the need to refrain from patterns of damaging addictive behaviors all too frequently have encountered insurmountable obstacles to obtaining help, such as risk to employment, lack of resources, needs of dependents, etc. We should be promoting personal change rather than erecting barriers, like stigma, against it. Like promoting help-seeking, all of us can help re-integrate those with addictions back into our communities. Rather than stigmatizing those coming out of the criminal justice system or addiction treatment programs, we need to welcome them back into our society following treatment, with needed housing, jobs, supports, and resources.

To achieve lower total costs and greater effectiveness, we as a society are responsible for ensuring adequate funding that provides appropriate and timely access to a choice of addiction treatments. Today, treatment completion rates hover around 50%. By providing high quality treatment programs that are adequately staffed, we also support treatment completion, which is critical for long term successful outcomes. Ultimately, this might involve social actions at the local levels, including legislative and government efforts (e.g., Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration) to provide needed resources across a spectrum of relevant care.

The recent presidential campaign and the media have graphically illustrated the epidemic problem of opiate deaths and more broadly, the Surgeon General’s report of addiction highlight the need for more attention and resources to solve this problem. What is now needed is more than good intentions, but rather a new agenda, a new way of thinking about systems that involve us all as responsible agents for setting the stage that leads our loved ones to healthy and addiction-free choices. We need to sponsor incubators of innovation, just as in the business world, to imaginatively and creatively find safer options and new ways of identifying those who are at risk and ultimately, treating and providing them the treatment and environmental supports to overcome their addictions.

Featured image credit: Medical Drugs for Pharmacy by epSos.de. CC0 Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Dilemmas of a broken substance abuse system appeared first on OUPblog.

Nine literary New Year’s resolutions

Do you need some inspiration for your New Year’s resolutions? If you’re in a resolution rut and feeling some of that winter gloom, then you’re not alone. Most of the top goals for 2016 fitted into the predictable categories of losing weight, taking more holidays, reading more, drinking less alcohol, and giving up smoking. Despite the day-to-day nature of these aspirations, most people go back on their New Year’s resolutions by the end of the first week of January!

To help you on your way to an exciting start to 2017, we’ve enlisted the help of some of history’s greatest literary and philosophical figures–on their own resolutions, and inspiring thoughts for the New Year.

1. Count your blessings

“Very many things to be grateful for, since then, however. Increased reputation and means—good health and prospects. We never know the full value of blessings ’till we lose them (we were not ignorant of this one when we had it, I hope) but if she were with us now…I think I should have nothing to wish for, but a continuance of such happiness.”

– Charles Dickens writes a poignant diary entry on 1 January 1838, regarding the death of his sister-in-law. She had briefly lived with the Dickens, and died in his arms after a brief illness in 1837 reminding us to count our blessings whilst they’re still with us.

2. New Year, new start

“Cheer up! Don’t give way. A new heart for a New Year, always!”

– A more positive resolution from Dickens’ The Chimes, prompting us to take courage as a new start is always just around the corner.

3. Treat yourself!

“La morte di Seneca, Musée du Petit-Palais, Parigi” by Jacques Louis David (1773). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“La morte di Seneca, Musée du Petit-Palais, Parigi” by Jacques Louis David (1773). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.“We went nowhere without figs and never without notebooks; these serve as a relish if I have bread, and if not, for bread itself. They turn every day into a New Year which I make ‘happy and blessed’ with good thoughts and the generosity of my spirit.”

– Take a lesson from Seneca and remember to treat yourself this January. Romans traditionally exchanged gifts of figs and dates on New Year’s Day, and they still symbolise prosperity and security to this day.

4. Go with the flow

“I opened the new year with what composure I could acquire…and I made anew the best resolutions I was equal to forming, that I would do what I could to curb all spirit of repining, and to content myself calmly—unresistingly, at least, with my destiny.”

– In stoic fashion on 1 January 1787, Frances Burney (the English satirical novelist) resolves to content herself with her destiny. If you’re struggling to retain your composure this January, “be like Burney” and go with the flow.

5. Rise early

“I have risen every morning since New Year’s day, at about eight; when I was up, I have indeed done but little; yet it is no slight advancement to obtain for so many hours more, the consciousness of being.”

– Samuel Johnson reminds us of the pleasures of early rising. He notes that waking early is not just to get more done in the day, but to extend the pleasure of our own “consciousness of being.” Why not join Dr. Johnson, and add an extra hour to your days?

6. Seize the moment

“‘A merry Christmas, and a glad new year,’

Strangers and friends from friends and strangers hear,

The well-known phrase awakes to thoughts of glee;

But, ah! it wakes far different thoughts in me.

[…] I, on the horizon traced by memory’s powers,

Saw the long record of my wasted hours.”

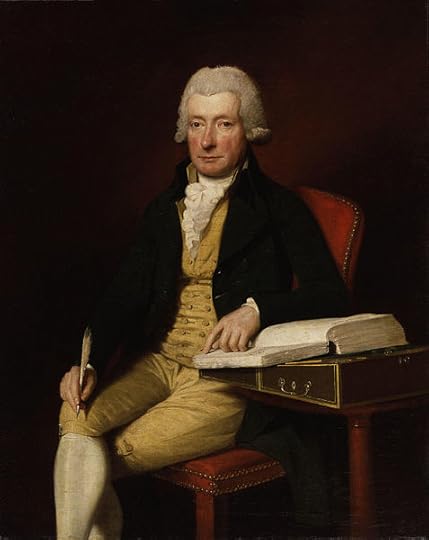

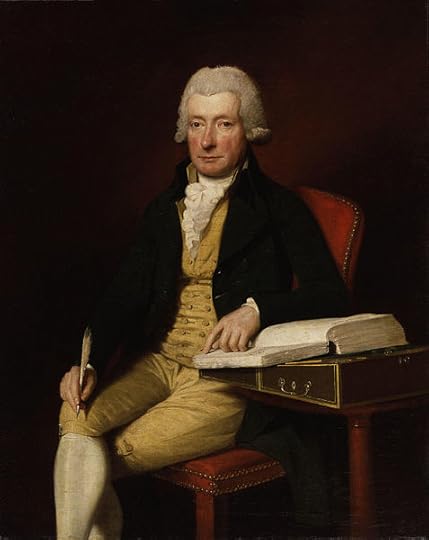

Portrait of William Cowper by Lemuel Francis Abbott (1792), from the National Portrait Gallery. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of William Cowper by Lemuel Francis Abbott (1792), from the National Portrait Gallery. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.– Amelia Alderson Opie’s Epistle to a friend on New Year’s Day finds the author wishing she’d seized the moment the previous year. Take some inspiration from Opie, and Carpe Diem this 2017!

7. Think of others first

“I dread always, both for my own health and for that of my friends, the unhappy influences of a year worn out; but, my dear Madam, this is the last day of it, and I resolve to hope that the new year shall obliterate all the disagreeables of the old one. I can wish nothing more warmly than that it may prove a propitious year to you.”

– The poet William Cowper (who suffered from periods of depression and mental illness) wishes his friend an auspicious new year. If you were faced with a “disagreeable” 2016, try sending out the positive vibes this January.

8. Leave the past behind

Ring out the old, ring in the new,

Ring, happy bells, across the snow:

The year is going, let him go;

Ring out the false, ring in the true.

– Forming part of Tennyson’s In Memoriam A.H.H., a poem lamenting the death of his beloved friend, these lines remind us that time waits for no man—and neither should we.

9. Don’t forget ‘dry January’

“Thanks be to God, since my leaving drinking of wine, I do find myself much better and to mind my business better and to spend less money, and less time lost in idle company.”

– On 26 January 1662, Samuel Pepys is thankful that he has kept his resolve with a seventeenth century dry January. If the old ones really are the best, why not follow in his footsteps and participate in a January dryathlon?

Featured Image Credit: “Budapest, Parliament, Fireworks” by 733215. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Nine literary New Year’s resolutions appeared first on OUPblog.

9 literary New Year’s resolutions

Do you need some inspiration for your New Year’s resolutions? If you’re in a resolution rut and feeling some of that winter gloom, then you’re not alone. Most of the top goals for 2016 fitted into the predictable categories of losing weight, taking more holidays, reading more, drinking less alcohol, and giving up smoking. Despite the day-to-day nature of these aspirations, most people go back on their New Year’s resolutions by the end of the first week of January!

To help you on your way to an exciting start to 2017, we’ve enlisted the help of some of history’s greatest literary and philosophical figures–on their own resolutions, and inspiring thoughts for the New Year.

1. Count your blessings

“Very many things to be grateful for, since then, however. Increased reputation and means—good health and prospects. We never know the full value of blessings ’till we lose them (we were not ignorant of this one when we had it, I hope) but if she were with us now…I think I should have nothing to wish for, but a continuance of such happiness.”

– Charles Dickens writes a poignant diary entry on 1 January 1838, regarding the death of his sister-in-law. She had briefly lived with the Dickens, and died in his arms after a brief illness in 1837 reminding us to count our blessings whilst they’re still with us.

2. New Year, new start

“Cheer up! Don’t give way. A new heart for a New Year, always!”

– A more positive resolution from Dickens’ The Chimes, prompting us to take courage as a new start is always just around the corner.

3. Treat yourself!

“La morte di Seneca, Musée du Petit-Palais, Parigi” by Jacques Louis David (1773). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“La morte di Seneca, Musée du Petit-Palais, Parigi” by Jacques Louis David (1773). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.“We went nowhere without figs and never without notebooks; these serve as a relish if I have bread, and if not, for bread itself. They turn every day into a New Year which I make ‘happy and blessed’ with good thoughts and the generosity of my spirit.”

– Take a lesson from Seneca and remember to treat yourself this January. Romans traditionally exchanged gifts of figs and dates on New Year’s Day, and they still symbolise prosperity and security to this day.

4. Go with the flow

“I opened the new year with what composure I could acquire…and I made anew the best resolutions I was equal to forming, that I would do what I could to curb all spirit of repining, and to content myself calmly—unresistingly, at least, with my destiny.”

– In stoic fashion on 1 January 1787, Frances Burney (the English satirical novelist) resolves to content herself with her destiny. If you’re struggling to retain your composure this January, “be like Burney” and go with the flow.

5. Rise early

“I have risen every morning since New Year’s day, at about eight; when I was up, I have indeed done but little; yet it is no slight advancement to obtain for so many hours more, the consciousness of being.”

– Samuel Johnson reminds us of the pleasures of early rising. He notes that waking early is not just to get more done in the day, but to extend the pleasure of our own “consciousness of being.” Why not join Dr. Johnson, and add an extra hour to your days?

6. Seize the moment

“‘A merry Christmas, and a glad new year,’

Strangers and friends from friends and strangers hear,

The well-known phrase awakes to thoughts of glee;

But, ah! it wakes far different thoughts in me.

[…] I, on the horizon traced by memory’s powers,

Saw the long record of my wasted hours.”

Portrait of William Cowper by Lemuel Francis Abbott (1792), from the National Portrait Gallery. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of William Cowper by Lemuel Francis Abbott (1792), from the National Portrait Gallery. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.– Amelia Alderson Opie’s Epistle to a friend on New Year’s Day finds the author wishing she’d seized the moment the previous year. Take some inspiration from Opie, and Carpe Diem this 2017!

7. Think of others first

“I dread always, both for my own health and for that of my friends, the unhappy influences of a year worn out; but, my dear Madam, this is the last day of it, and I resolve to hope that the new year shall obliterate all the disagreeables of the old one. I can wish nothing more warmly than that it may prove a propitious year to you.”

– The poet William Cowper (who suffered from periods of depression and mental illness) wishes his friend an auspicious new year. If you were faced with a “disagreeable” 2016, try sending out the positive vibes this January.

8. Leave the past behind

Ring out the old, ring in the new,

Ring, happy bells, across the snow:

The year is going, let him go;

Ring out the false, ring in the true.

– Forming part of Tennyson’s In Memoriam A.H.H., a poem lamenting the death of his beloved friend, these lines remind us that time waits for no man—and neither should we.

9. Don’t forget ‘dry January’

“Thanks be to God, since my leaving drinking of wine, I do find myself much better and to mind my business better and to spend less money, and less time lost in idle company.”

– On 26 January 1662, Samuel Pepys is thankful that he has kept his resolve with a seventeenth century dry January. If the old ones really are the best, why not follow in his footsteps and participate in a January dryathlon?

Featured Image Credit: “Budapest, Parliament, Fireworks” by 733215. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post 9 literary New Year’s resolutions appeared first on OUPblog.

Understanding the populist backlash

Although populism is making headlines across the globe, there is a lot of confusion about what this concept really means and how we can study this phenomenon. Part of the problem lies in the usage of the term as a battle cry. Both academics and pundits often employ the term populism to denote all the political actors and behaviors they dislike. While there are good reasons to worry about authoritarianism, economic mismanagement, opportunism, and racism, we should not treat them all as equivalents of populism. Augusto Pinochet was an autocrat, G. W. Bush mismanaged the economy, the Italian Christian Democratic Party was highly opportunistic, and South Africa’s National Party was racist, but none is an example of populism.

So what is populism? We have developed a comparative research agenda on populism whose starting point lies in the construction of a definition that can be used to analyze the phenomenon across time and place. As we have explained elsewhere in more detail, populism is best defined as “a thin-centered ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic camps, “the pure people” versus “the corrupt elite,” and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people.” In this view, the establishment is a perverse entity that governs solely for its own benefit, while the people is a homogenous community with a unified will. Take, for instance, the following statement by Donald Trump, in his speech in Florida on 16 October:

Our movement is about replacing a failed and corrupt establishment with a new government controlled by you, the American People. There is nothing the political establishment will not do, and no lie they will not tell, to hold on their prestige and power at your expense. […] This is not simply another 4-year election. This is a crossroads in the history of our civilization that will determine whether or not We The People reclaim control over our government.

As with any other ideology, populism is espoused not only by specific leaders, but also by certain constituencies. This means that one needs to take into account both the supply-side and the demand-side of populist politics. Regarding the former, different political actors across the globe combine populism with some other ideological agenda (which we call the ‘host ideology’). Generally speaking, we can distinguish between two broader types of populism: right-wing populism usually combines populism with some form of nationalism, while left-wing populism tends to combine it with some form of socialism. General mass of Indignados protesting austerity measures in Athens’ Syntagma Square in 2011 by Ggia. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

General mass of Indignados protesting austerity measures in Athens’ Syntagma Square in 2011 by Ggia. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

While all forms of populism combine both exclusionary and inclusionary aspects, right-wing populism tends to be more exclusionary, while left-wing populism is usually more inclusionary. Today, exclusionary right-wing populism is characterized by the promotion of a populist rhetoric with a strong emphasis on xenophobia, traditional moral values, as well as law and order issues. Paradigmatic examples of this type of populism are political parties such as the National Front in France or social movements like the Tea Party in the United States. On the other hand, inclusionary left-wing populism uses the populist set of ideas to politicize existing inequalities and defend a radical model of democracy, which is aimed at empowering popular sectors. Chavismo in Venezuela and Podemos in Spain are exemplary cases of this type of populism.

Those who articulate a populist discourse do not operate in vacuum, but rather in countries with different grievances and historical legacies. This means that one should also consider the demand-side of populist politics. Although the populist attitudes are widespread among voters, it is only under certain circumstances that populist sentiments are activated at the mass level. One of the main triggers for the increasing demand for populism lies in the general feeling that the political system is unresponsive. If certain constituencies share the idea that existing political parties do not take their claims into account, we should not be surprised that these constituencies interpret political reality through the lenses of populism. In the words of one of protesters of the anti-austerity populist movement in Greece, “we are here because we know that the solutions to our problems can only come from us. […] We will not leave the squares, until all those who led us here are gone: Governments, the Troika, Banks, Memoranda, and all those who take advantage of us.”

Across the globe liberal democracies are challenged by populist forces of different political color. The key question is how to respond to this challenge. Those interested in answering this question should keep in mind that populism can have both positive and negative effects on democracy. While it is true that both populist leaders and followers harbor illiberal tendencies and propose simple solutions to complex problems, they are able to (re)politicize certain issues that are, either intentionally or unintentionally, not (adequately) addressed by mainstream political actors. This means that the establishment needs to reassess not only the ideas and interests it has been advancing, but should also reconsider if the attempt to depoliticize contested issues, such as immigration and economic liberalization through international organizations, is the best way ahead.

Featured image credit: Donald Trump at a campaign rally in Phoenix, AZ by Gage Skidmore. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Understanding the populist backlash appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers