Oxford University Press's Blog, page 419

January 13, 2017

Curing brain aneurysms by reconstructing arteries

A brain aneurysm is a tiny bubble or bulge off the side of an artery on the brain’s surface. It may grow undetected, the product of blood vessels weakened by high blood pressure, cigarette use, inherited genes, or (in most cases) just bad luck. While it is believed that about one in 50 Americans harbor a brain aneurysm, most will never know it, and their aneurysm will never cause a problem. But rarely, the arterial wall of an aneurysm can become so thin that it bursts, spilling blood over the brain’s surface. This is the most feared outcome of a brain aneurysm and is what drives the urgency in treating many brain aneurysms, even if found accidentally.

Any quick online search will tell you why. More than one third of people who suffer a ruptured brain aneurysm will die as a consequence. Of those who survive, the majority will be left with a disability or neurologic deficit. The financial costs to society are high, and the emotional costs to patients and their families are even higher. Between the silent growth, potentially explosive nature, and the devastating consequences, brain aneurysms have been aptly termed “ticking time bombs.”

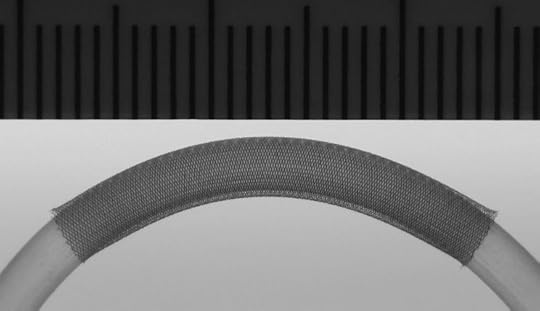

The treatment of brain aneurysms is aimed at disrupting blood flow into the aneurysm. This was traditionally done from the outside by pinching the aneurysm with a metal “clip” or from the inside by filling an aneurysm with metal “coils.” These treatments, however, were not uniformly successful or even possible with some aneurysms. This prompted physicians and engineers to experiment with a novel concept of treating a brain aneurysm indirectly by encouraging the blood flowing through an artery to stay within that artery and not enter the bulging aneurysm as it passed by. This was done using tiny stents, or mesh tubes that could be placed within a blood vessel in the brain across the origin of an aneurysm. As blood flow slows or stagnates within an aneurysm, it forms a clot and then eventually scars down, occluding the aneurysm. The density of the mesh turned out to be key – if the mesh was too dense it might inhibit flow into other normal branches that the brain needs for survival but if not dense enough, the aneurysm would continue to fill with blood and remain a danger. The perfect mesh tube would contour the artery, shepherding blood past the aneurysm and through the normal arteries. Once that aneurysm clotted and scarred, the mesh would then serve as a scaffold, allowing cells of the inner lining of the artery, known as the endothelium, to grow across the aneurysm. The artery would, in effect, reconstruct itself.

The Pipeline Embolization Device, an implantable flow diverting stent used to treat brain aneurysms. Courtesy of Neuroangio.org and used with permission.

The Pipeline Embolization Device, an implantable flow diverting stent used to treat brain aneurysms. Courtesy of Neuroangio.org and used with permission.Careful experimentation and product design eventually led to the production of several commercially-available devices, now known as “flow diverters.” The first and most widely available in the United States was known as the Pipeline Embolization Device, which received its Federal Drug Administration approval based on the results of a prospective trial known as the Pipeline for Uncoilable or Failed Aneurysms (PUFS) trial. This single-arm trial tested the use of this device on large and giant aneurysms that were considered otherwise untreatable or had failed prior attempts at conventional treatment. The initial results were exciting in that over 70% of treated aneurysms were occluded at a six-month follow-up. This result, however, came with a risk of stroke or death in 5.6% of the patients, which was considered comparable to other treatments.

Long-term follow-up of the original patients from this trial was recently published, showing overall aneurysm occlusion rates of greater than 90% after five years with no additional major complications after the initial six-month follow-up. Importantly, treatment with flow diverters was durable, and there were no instances of an aneurysm recurring after successful occlusion.

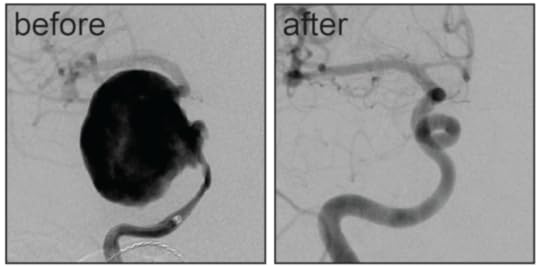

Treatment of a giant internal carotid artery aneurysm with the Pipeline Embolization Device. Image provided by the author and used with permission.

Treatment of a giant internal carotid artery aneurysm with the Pipeline Embolization Device. Image provided by the author and used with permission.The recent success of flow diverters has been followed with development of many new devices and technologies all aimed at making aneurysm treatment safer and more effective. There is no one treatment that will cure every aneurysm, but each additional technology provides one more tool that aneurysm surgeons can use to stop these ticking time bombs before it’s too late.

Featured image credit: Surgical instruments by tpsdave. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Curing brain aneurysms by reconstructing arteries appeared first on OUPblog.

Caring about the past in the embattled present

Growing up in Manhattan meant that I didn’t live among ancient ruins – just subway stations, high-rise apartments, and Central Park’s relatively recent architectural confections. It took living for a year in Europe as a six-year old and for another year as a ten-year old to develop awareness about our collective heritage stretching back millennia. Visiting the vacant site of Stonehenge on a blustery fall day in the early 1960s, long before the introduction of a Visitor Centre and tickets, led me to imagine white-robed druids chanting among the stones. I filled a small bottle with water from the Roman baths in Bath, England, believing that the water itself was 2,000 years old. And I pretended to be a knight while exploring the medieval citadel of Carcassonne in Southeastern France, built atop the remains of Roman fortifications.

Yet as we shake our heads at images of Aleppo’s rubble captured through slow-moving drones, it is hard to explain why attention to the remote past warrants even a millisecond of concern today. Tragedy and misfortune strike people around the globe, hour by hour. From criminal gangs to intolerant governments to natural disasters, our 24-hour news cycle provides an ever-spinning carousel of loss.

In the face of human brutality and environmental devastation, the relevance of archaeology is far from obvious. But to those of us who have sought to illuminate the handiwork of ancient artisans, artists, and architects, and the contexts in which they toiled, the real gift of that study is a balanced perspective about our place in history.

It is possible to be consumed by sadness from footage replayed minute-by-minute on screens of every type. But it is also possible to seek a larger understanding of life, in recognizing that it has always been so.

Before modern medicine, there were neither vaccines nor awareness of preventive treatments. Before satellites, there was no ability to forewarn those in the path of a tsunami. And before video and the Internet, there was no way to reveal acts of violence perpetrated on the innocent.

“The study of antiquity reminds us that the human condition is ever-changing, and that our sense of self is built on the remains of earlier civilizations.”

With each of these advances and countless others, our modern lives have been greatly improved since Thomas Hobbes’s 1651 description in Leviathan of the natural state of mankind as “nasty, brutish, and short”. As more people are lifted out of poverty, generation by generation, we can find consolation in the fact that increased global awareness is spreading among the young, rather than receding, regardless of the vagaries of electoral politics of the moment.

The study of antiquity reminds us that the human condition is ever-changing, and that our sense of self is built on the remains of earlier civilizations. By making room and time for understanding what people believed, how they lived, and what they left behind for us, we stand to appreciate what we do have without forgetting what we can do to better the lives of others.

There are many among us who work to improve the world without interruption—and we are all grateful to environmentalists, firefighters, police, and first responders, medical professionals, members of the military, scientists, social workers, and so many others for their daily efforts. But they too can find perspective and awareness about the value of their work through the lens of history. It is a lens that both sharpens our vision about the day’s events and magnifies otherwise less visible lessons of earlier times, without which we would be an impoverished world, lacking the long view.

By embracing the long view and the examined life that comes with it, we can equip ourselves for thoughtful, purposeful action, leavened by knowledge of antiquity, sensitivity to the present, and clear-eyed hopefulness about the future. For kids growing up in both the canyons of New York and the smoldering remains of postwar Syria, that potential for hopefulness will be an essential ingredient in keeping the human experiment one of promise and possibility.

Featured image credit: “Paestum, Salerno, Italy” by valtercirillo. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Caring about the past in the embattled present appeared first on OUPblog.

What to keep in mind for the inauguration

Given our constitutional separation of powers, it seems odd that a presidential inauguration takes place on the Capitol steps. Like so much else in American history, the story begins with George Washington. In 1789, the First Congress met in New York City, where it proceeded to count the electoral ballots, an easy task since the vote had been unanimous. Congress sent notification to the president-elect in Virginia, and then swore in Vice President John Adams, who presided over the Senate before Washington ever arrived in New York.

As the only functioning branch of the new federal government at the time, Congress appointed a joint committee to conduct the presidential inauguration. Although the House of Representatives occupied the largest chamber in New York’s Federal Hall, the Senate had a balcony that would enable large crowds outside to witness the ceremony. After taking his oath outside, Washington went to the Senate chamber and delivered the first inaugural address. Everyone then proceeded to nearby St. Paul’s church to seek divine blessing for the new government. The First Amendment did not yet exist, but there was some controversy about this event since not everyone approved of an Episcopal church service. The joint committee had not recommended it, but the “churchmen” in Congress preferred it.

The Constitution specifies only the text of the oath of office that the president would take, and the date and time for the ceremony. Only the president takes that oath. Other government officials take an oath written by Congress. Beyond the Constitutional requirements, that first inauguration established many traditions. Congress would host the inaugural ceremonies and open them to the public. The Senate would take the lead in the joint committee on inaugural ceremonies. The new president would deliver an inaugural address. There would also be a parade, although in 1789 the parade had escorted the president to the inauguration, rather than away from it. And there would often be a church service connected to the event. Some accounts say that Washington ended his oath by saying “I swear, so help me God,” but the evidence is so sparse and contradictory that we don’t know one way or the other. That phrase is not in the Constitution, although Congress wrote it into the oath for other federal office holders. It is a personal choice for the president to say it, but one would think that the chief justice might want to deliver the oath exactly as it appears in the Constitution, without embellishment.

When the federal government moved to Washington, Thomas Jefferson’s inauguration took place in the Senate Chamber (the House wing of the Capitol remained incomplete at the time). The ceremony moved back outside for James Monroe’s inaugural in 1817, since by then the British had burned down the Capitol. Andrew Jackson took office as the man of the people, and such a large crowd was expected that he took the oath on the East Front stairs, beginning a tradition that continued until Jimmy Carter. The one exception was FDR’s 4th Inaugural in 1945, who overrode congressional objections during wartime to hold an austere inaugural at the White House. Despite its unhappiness, Congress could do nothing about it.

Photograph of President Franklin D. Roosevelt delivering his fourth Inaugural Address by Abbie Rowe, 1905-1967. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Photograph of President Franklin D. Roosevelt delivering his fourth Inaugural Address by Abbie Rowe, 1905-1967. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Every four years, construction of the inaugural platform grew more elaborate and expensive until 1980, when the Joint Committee voted to shift the ceremonies to the West Front, where the existing terrace could serve as a platform and where much larger crowds could be accommodated down the Mall. News stories often claim that Ronald Reagan as a Westerner chose the West Front, but in fact the joint committee had designated that site before Reagan had been nominated. Reagan shrewdly took possession of the move by incorporating it into his inaugural address, orating about looking west towards “those shrines to the giants on whose shoulders we stand,” and the graves of heroes in Arlington National Cemetery. Having gotten credit for a decision he did not make, Reagan did ask to move his next inauguration into the Capitol Rotunda because of extremely cold temperatures that day.

The biggest single change in the inauguration has been the date, which the Twentieth Amendment moved forward from 4 March to 20 January. This was done in part to stagger the beginning of the congressional and presidential terms so that preceding president did not need to spend their last night in office signing legislation before their authorization expired at noon. The weather in March was never good–rain, snow, cold blustery days–but the weather in January has also been unpredictable. Historians and journalists are always looking at the weather reports to find some ray of sunshine or other omen portending the future of the new administration.

The upcoming inauguration will attract large crowds in Washington and be broadcast and streamed to audiences around the world. All this holds great significance. After a divisive election, when everyone has chosen sides, the inauguration is intended to reunite the country. Presidential inaugural addresses traditionally appeal for healing the nation’s wounds and establishing common ground. In the wake of this past election, such goals will be much harder to achieve, but when the three branches of the government come together, with the legislative branch hosting on its steps the swearing in of the chief executive by the chief justice of the United States, the underlying theme will be national unity.

Featured image credit: Marching Band Military Army by Skeeze. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post What to keep in mind for the inauguration appeared first on OUPblog.

January 12, 2017

How the mind comes into being

When we interact with our world – regardless if by means of a simple grasp, a smile, or the utterance of a sentence – we are typically quite confident that it was us who intended to and thus executed the interaction. But what is this “us”? Is it something physical or something mental? Is it merely a deterministic program or is there more to it? And how does it develop, that is, how does the mind come into being?

Clearly, there is not a straight-forward answer to these questions. However over the last twenty years or so, cognitive science has offered a pathway towards an answer by pursuing an “embodied” perspective. This perspective emphasizes that our mind develops in our brain in close interaction with our body and the outside environment. Moreover, it emphasizes that we do not passively observe our environment – like the prisoners in Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave” – but that we are actively interacting with it in a goal-directed manner.

Even with such a perspective, though, challenging questions remain to be answered. How do we learn to control our body? How do we learn to reason and plan? How do we abstract from and generalize over our continuously incoming sensorimotor experiences and develop conceptual thoughts?

It appears that key computational and functional principles are involved in mastering these immense cognitive challenges. First of all, bodily features can strongly ease the cognitive burden, offering embodied attractors, such as when sitting, walking, holding something, or when uttering a certain sound. The addition of reward-oriented learning helps to accomplish and maintain the stability of these attractors. Think of the joy expressed by a baby, who has just accomplished the maintenance of a novel stable state for the first time, such as taking the first steps successfully!

How do we learn to control our body? How do we learn to reason and plan?

However, our minds can do even more than expressing reactive, reward-oriented behavior. Clearly, we can think ahead and we can act in anticipation of the expected action effects. Indeed, research evidence suggests that an “image” of the action effects is present while we interact with the world. It seems that this image focusses on the final effect of the action – such as holding an object in a certain way after grasping it. Thus, predictions and anticipations are key components of our minds. Combined with the principle of stability, desired future stable states can be imagined, their realization can be accomplished by goal-oriented motor control, and the actual accomplishment can trigger reward.

How are these principles spelt out in our brains? When considering the brain’s neural structures and their sensory- and motor-connectivity, it may be possible to describe a pathway towards abstract thought. Hierarchical, probabilistic, predictive encodings have been identified, which can be mimicked by computational processes. When allowing interactions between multiple partially redundant, partially complementary sensory information sources, progressively more abstract structures can develop. These include:

Spatial encodings – such as the space around us as well as cognitive maps of the environment;

Gestalt encodings of entities – including objects, tools, animals, and other humans;

Temporal encodings – estimating how things typically change over time.

These encodings are temporarily or permanently associated with particular reward encodings, depending on the experiences.

When reconsidering behavior in this scenario, it becomes very clear that hierarchical structures are also necessary for realizing adaptive and flexible behavior. To be able to effectively plan behavioral sequences in a goal-directed manner, such as drinking from a glass, it is necessary to abstract away from the continuous sensorimotor experiences. Luckily, our continuous world can be segmented in an event-oriented manner. An event-boundary, such as the touch of an object after approaching it, or the perception of a sound wave after a silence, indicates interaction onsets and offsets. Computational measures of surprise can be good indicators to detect such boundaries and segment our continuous experiences.

But what about language? From the perspective of a linguist, the Holy Grail lies in the semantics.

But what about language? From the perspective of a linguist, the Holy Grail lies in the semantics. Although we have no system that is able to build a model of the world’s semantics – except for our brains – yet, computational principles and functional considerations suggest that world semantics may be learned from sensorimotor experiences. Moreover, language seems to fit perfectly onto the learned semantic structures. All this learning happens in a social and cultural context, within which we experience ourselves and others – particularly during social interactions with others, including conversations. In addition, tool usage opens up another perspective onto us as tools, serving a purpose.

Putting the pieces together, we are advancing toward developing artificial cognitive systems that learn to truly understand the world we live in – essentially demystifying the puzzle of our “selves” by computational means. Conversely, a functional and computational perspective onto our “selves” suggests that we are intentional, anticipatory beings that are embodied in a socially-predisposed, understanding-oriented brain-body complex, choosing goals and behaviors in our own best interest – in the search for finding our place in the social and cultural realities we live in.

Featured image credit: Barefoot child by ZaydaC. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post How the mind comes into being appeared first on OUPblog.

Marital love and mourning in John Winthrop’s Puritan society

Puritans did not observe birthdays as we do, but the occasion–John Winthrop’s twenty-ninth birthday–in January 1617 may well have been a time for greater reflection than normal. Winthrop was in mourning for his wife, Thomasine Clopton Winthrop, who had died on 8 December. Four hundred years later, it is appropriate to reflect on what Winthrop’s experience and his Thomasine’s protracted death tells us about love and marriage, and death, and dying in puritan society.

John had been born and baptized in Edwardstone, one of the small communities adjoining Groton where the Winthrop’s owned land. His uncle was the lord of Groton manor, and shortly after John’s birth his family moved to Groton so his father, Adam Winthrop, could manage the estate for his brother. Groton was part of a godly kingdom encompassing much of the Stour Valley that was deeply shaped by puritan values. In 1602, John matriculated at Trinity College, Cambridge and may well have expected to prepare for the ministry. But his plans changed. On a visit to Great Stambridge, Essex, the home of one of his college friends, he was smitten by Mary Forth and the 17-year-old married her a few months later, in April 1605. There is reason to believe that the attraction was largely sexual. Contrary to what many believe, puritans did not view sex as sinful. They saw human sexuality as a gift from God that would bring a married couple closer together. Intercourse between a husband and wife was, as the puritan clergyman William Gouge preached, “one of the most proper and essential acts of marriage.” It “must be performed with good will and delight, willingly, readily, and cheerfully.” “As the man must be satisfied at all times in his wife,” he wrote, “and even ravished with her love; so must the woman.”

Mary gave birth to a son John in 1606, Henry in 1608, Forth in 1609, and Mary in 1612, while two other daughters died shortly after birth in 1614 and 1615. While physically compatible, the couple was not well matched spiritually. John was struggling to adapt to the different expectations of the puritan community in southwest Essex–he was criticized for hunting along a creek and allowing card-playing by his servants–but he was also troubled by Mary’s unwillingness “to talk with me about any goodness.”

Groton church and Groton Hall in Suffolk, England, where John Winthrop was lord of the manor before traveling to New England. Image is from the author’s collection, used with permission.

Groton church and Groton Hall in Suffolk, England, where John Winthrop was lord of the manor before traveling to New England. Image is from the author’s collection, used with permission. Mary died in childbirth in June 1615. In 1613, the couple had moved to Groton, where John had, with the help of his father, purchased the estate from his uncle. Bereft of the marital companionship which was so important to him in December 1615, John married Thomasine Clopton, whom he had known from childhood. Thomasine was well read and deeply spiritual. She shared his concern for the broader community and supported the erection of a house for the impotent poor on manorial land John donated to Groton’s overseers of the poor and church wardens. Thomasine soon became pregnant, but their child, a daughter born on 30 November 1616, died a few days later. Thomasine herself did not recover from the childbirth, and died on 8 December.

During the days that Thomasine hovered between life and death, John was constantly at her bedside. His long and detailed account of her last days is one of the most affecting deathbed accounts of the period. Winthrop’s concern for his “dear and loved wife” is evident, as is Thomasine’s concern for him and her step-children, and the deep religious faith they shared. John was constantly with her, reading to her from the Scriptures, especially the gospel of John and the Psalms. She called the various servants of the estate to her bedside, exhorting them to live godly lives, and identifying things, such as excessive pride, that they should guard against. She thanked John’s parents for the kindness and love they had given her, and blessed the children. What made her situation more painful for John was that the “second Sunday of her illness,” when her death was certain, was the anniversary of their marriage. Devastated by his own approaching loss, he comforted her with how “she should sup with Christ in Paradise that night” and of “the promises of the Gospel, and the happy estate that she was entering into.”

Years later, in his lay sermon on “Christian Charity,” he preached to those embarking on the errand into the New England wilderness, John Winthrop would express the obligation for members of a godly Christian community to “mourn together” as well as to “rejoice together,” always having before them “our community as members of the same body.” Winthrop himself had recorded occasions of having visited and comforted neighbors who were in need. Now, following the death of Thomasine, he himself needed the support of friends–including a group of clergy and laymen whom he had joined in a conference (a spiritual prayer group)–as he struggled with his sense of loss. He gradually emerged from a grief that for a time led him to question God’s love, and by the end of 1617, he had begun to court Margaret Tyndale, whom he would wed in 1618 and who would stand by his side till her death in 1647.

John’s remarriage sixteen months after Thomasine’s death was not evidence of insincerity in the affection he had expressed for Thomasine, nor simply a necessity to find a helpmate in raising his young children. As noted before, marriage was seen by Winthrop and most puritans as a critical relationship in which a couple through love came together to aid one another not only materially but spiritually. Winthrop’s religious faith was often strengthened by a comparison between the love he felt for a spouse and the love God bestowed on him. On one such occasion he dreamed of Christ and was “so ravished with his love towards me, far exceeding the affection of the kindest husband, that being awakened,” he had “a more lively feeling of the love of Christ than ever before.” We should not generalize about puritan views of marriage and love from the experiences of one individual, but there are ample other examples in the poetry of Anne Bradstreet and the diaries of Samuel Sewall, as well as elsewhere, to make it clear that if Winthrop’s story was not that of all puritans it was certainly common. Marital love, religious faith, and social commitment all were interrelated in his story.

Featured image credit: Oil painting of John Winthrop from the early 18th century, based on a portrait from the 1630s. Artist unknown, National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Marital love and mourning in John Winthrop’s Puritan society appeared first on OUPblog.

The distinctiveness of German Indology – and its expression in German philosophy

Unlike England, France, Holland, Spain, and Portugal, Germany scarcely enjoyed vast or prosperous overseas colonies. Late to develop its navy, Germany entered into the notorious “scramble for Africa” toward the closing years of the 19th century, and would soon lose (or give away, if the story is true) what it had recently acquired, early on in the 20th century. Prior to the Chancellorship of Otto von Bismarck (who became active in the 1860s), Germany was just not a salient participant in the so-called Europeanization of the earth.

For those powers that were (like England and France), it was quite expected to witness the cultivation and development of new domains of knowledge pertaining to the regions under colonial rule. Where else would we expect an institution devoted to the languages, customs, religions, laws, history, and politics of the various nations of Asia and Africa than right in the metropolitan centre of a great colonial power? The Ecole Spéciale des Langues Orientales of Paris and SOAS in London both make perfect sense. Within this context—the link between colonial power and colonial knowledge—the prominence and dynamic nature of German Indological scholarship was something of an anomaly. It was, more or less, as close as you could get to unmotivated study; scholarship in the pure pursuit of knowledge.

Of course, the drive for just this sort of knowledge didn’t arise in a vacuum. The German fascination surrounding “ancient Indian wisdom” unfolded in parallel with the rising interest in Germany’s own distinctive, pre-Christian past. Another important current, especially with the onset of the 19th century, was a rising prevalence of a sort of synthetic way of thinking; similar to what, in the late 20th century, we began to capture with the corny expression “think global”. By the time the German philosopher who thought most globally, G.W.F. Hegel (1770-1831), was to pen his compendium of all knowledge—the three-volume Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences—synthetic thoughts encompassing all the known globe already reigned supreme among the foremost intellectuals of his time.

Such ideas appeared everywhere: they had aesthetic manifestation as Romanticism; their political manifestation was trans-national socialism; their philological manifestation was the search for an Ursprache (a proto-Indo-European language ultimately linking all great civilizations at a unified cradle or source); and there was, of course, their philosophical manifestation as a quest for absolute knowledge with not merely a universally valid force, but indeed a universally comprehensive source. It was in this vein that the German Indologists so eagerly explored and promulgated whatever morsels of literature or philosophy were available to them from India.

…Hegel treated Indian thought with acerbic contempt, riding roughshod over the subtle distinctions which, during cooler and more contemplative moments, he himself took great pains to tease out, articulate, and explore.

Hegel was himself willy-nilly immersed in this syncretist mood, albeit vectored by his peculiar genius. He had the personal ambition to collect from all corners every worthwhile sundry piece of human knowledge and cultural achievement and to synthesize it all into one resource, which—as mentioned—he would call the Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences. At the centre of the word encyclopedia we observe the term cyclo, circle or cycle. Hegel would consciously use the imagery of the circle as symbolic of the completeness of his philosophical system. And a precondition for this completeness was, of course, a full and robust characterization, evaluation, and placement of ancient Indian wisdom within it.

But what Hegel is most known for today with respect to his appraisal of Indian art, religion, and philosophy is not how much time and energy he devoted to studying and writing about them, but instead his harsh critiques, unkind representations, his rudeness transgressing into outright racism.

Hegel had indeed inherited (and perpetuated) so many of the vices of his era: orientalism, chauvinism, religious bias, pride in the sense of cultural superiority, cruel anti-Semitism—the full gamut. On the other hand, his philosophical bent enjoined repeated engagement with the newly discovered treasures of Indian philosophy, and his irrepressible intellectual hunger and curiosity engendered his wide-ranging study of Indian mythology, history, art, and religion.

On one side, posturing against his intellectual rivals (that is, the German romantics, great champions of Indian wisdom) Hegel treated Indian thought with acerbic contempt, riding roughshod over the subtle distinctions which, during cooler and more contemplative moments, he himself took great pains to tease out, articulate, and explore. And yet that which was most impressive to Hegel about Indian philosophy also posed a deep threat to him. At times it might have struck him that all his thankless, laborious development of a cutting-edge, end-all philosophy, culminated in no more than the very same insights articulated by distant Indian philosophers so many centuries before.

To be sure, Hegel’s relationship to Indology was complicated. Using another contemporary expression, it could quite accurately be epitomized as a love-hate relationship.

Speaking of the hate moments, many of Hegel’s prejudices and contemptuous pronouncements appear shameful to us nearly two centuries on. But to turn the tables, you might ask yourself how our own self-righteousness might appear to Hegel: for under our watch, at even the best universities in the Anglophone world, students are graduated with degrees in philosophy without ever having heard the names or basic concepts of major philosophers or philosophical systems that arose in traditions ostensibly beyond the horizon of our own. “Ostensibly” beyond, because, as Hegel illustrated, we are actually free to determine for ourselves where we would like that horizon to lie. Professional contemporary philosophers in the Western world have preponderantly drawn the boundary, physically and metaphysically, in a manner even more retrograde and rigid than Hegel’s own.

Featured image credit: Friedrich Hegel mit Studenten by Franz Kugler. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The distinctiveness of German Indology – and its expression in German philosophy appeared first on OUPblog.

January 11, 2017

From good wine to ivy

Last week’s post was about the proverb: “Good wine needs no bush,” and something was said about ivy as an antidote to good and bad wine. So now it may not be entirely out of place to discuss the origin of the word ivy, even though I have an entry on it my dictionary. But the entry is long and replete with off-putting technical details. Also, though I would like my dictionary to be on every word lover’s desk, this does not yet seem to be the case.

Does anyone in the Ivy League know the origin of the word ivy? Whatever the answer, read this post!

Does anyone in the Ivy League know the origin of the word ivy? Whatever the answer, read this post!It grieves me to say that despite the medicinal qualities of ivy, the origin of the word ivy remains partly hidden, and the same is true of the plant’s name in quite a few other languages, for instance, Greek (kissós), Latin (hedera), and Russian (pliushch). Plant names are often borrowed from indigenous languages about which little else or even nothing is known, that is, from the languages of the people who inhabited the land now belonging to new settlers. The old population could be either exterminated or assimilated, and the old language could become extinct, but some words might penetrate the speech of the invaders. Examples are not far to seek. The Celts in Britain mixed with the native Picts. Later, Germanic speakers conquered the island, so that it would not come as a surprise if Pictish words turned up in Irish, Welsh, and Scots, or even English, but the source is lost. Those who have read Robert Louis Stevenson’s ballad “Heather Ale” will remember the situation, even though the Picts were not exterminated and were probably not shorter than the Scots (the drama related in the ballad has nothing to do with history). I have always suspected that pixie, a word of unknown origin (it surfaced in English only in the seventeenth century) is in some way connected with Pict, that it is of Celtic-Pictish origin, and that the small size of those fairy-like creatures gave rise to the legend of the Picts’ diminutive stature. Alas, I have no evidence for my etymology. Celtic legends became famous via Old French (King Arthur and King Mark). Tristan, understood by Romance speakers as a sad person (remember Sibelius’s “Valse Triste”?), probably had a Pictish name, whose origin we have no chance to uncover. Incidentally, Latin hedera is not related to Engl. heather, and heather is another word whose etymology is “disputable.”

This is a stone with a text in Pictish. The inscription on Aberlemno Stone 1, like other Pictish inscriptions, has not been deciphered.

This is a stone with a text in Pictish. The inscription on Aberlemno Stone 1, like other Pictish inscriptions, has not been deciphered.Ivy has been known since the Old English days. Its earliest recorded form was īfig; it has an established cognate only in German in which the modern form of ivy is Efeu, from ebah. Dutch eiloof (apparently, but not certainly, ei–loof, with loof meaning “leaf”) may be related, but its history is even less clear than that of the English word. The match Old Engl. īf-ig ~ Old High German eb-ah is far from perfect, but the differences can be explained or at least explained away. There have been many attempts to detect the word for “hay” in –ig ~ –ah, because in Old High German, ebah competed with eba–hewi, but the longer form was, most likely, an alternation due to folk etymology: ivy leaves were, and in some places still are, regularly used as fodder in winter. Even a thousand years ago, the inner form of ebah and īfig must have been totally opaque. As always in such cases, it should be stated that, if the recorded names of ivy (īfig and Efeu) are substrate words, borrowed from a lost language, all subsequent discussion is a waste of time. But I believe that the words are Germanic and will continue.

There have been numerous attempts to derive ivy from the name of some other plant, and indeed, several such names look suggestive: Greek ápion “pear,” the putative source of Lain apium “parsley” (not “pear!), which yielded French ache “parsley, celery” and which German borrowed as Eppich “celery” and sometimes “ivy”(!); German Eibe “yew” (it is a cognate of Engl. yew); Latin abiēs “fir”; the mysterious Middle Engl. herbe ive, known from Canterbury Tales, certainly not “ivy” (the word is French, and it disappeared from English at the beginning of the seventeenth century: OED). The Indo-European word for “apple” belongs here too. Some pre-Indo-European migratory plant name could have been known to Germanic speakers and associated with ivy. It need not even have been the name of ivy, as the gulf between “pear” in Greek and “parsley” in Latin or between Arabic rībās “sorrel” and Engl. ribes “currants” (OED) shows. I’ll skip the many attempts to explain ivy as “a plant on top of some object or another plant” and on this account to compare the word with the names of some articles of clothing (a reasonable idea: compare Dutch klimop, literally “climber up;” by the way, more than thirty Dutch names of ivy are known), as well as some dubious look-alikes in Old Icelandic, and go on to the only etymology that for a long times was and sometimes is still considered true.

In 1903, the West Germanic name of ivy was compared by Johannes Hoops, an excellent philologist, with Latin ibex “a mountain goat.” Both the animal and the plant emerged as climbers. Hoops’s etymology found influential supporters, though Kluge and Skeat were not among them. However, the later editors of Kluge’s etymological dictionary of German either sided with Hoops or found his opinion correct or at least worthy of discussion. Yet it is, most probably, wrong. The Indo-European root ibh– “to climb” did not exist. This is not a crushing objection to Hoops, for some other (similar) root can be found to fit the desired meaning, and such a root has been offered. More important is the fact that ibex is a word of unknown origin, probably an animal name borrowed into Latin from some Alpine, non-Indo-European substrate. I am sorry for rubbing in the same rule year after year, but this is indeed the golden rule of etymology: one word of unknown origin can never throw light on another opaque word. Whoever violates this rule, eventually repents.

An ibex. The horns are wonderful but have probably nothing to do with the origin of the word ivy.

An ibex. The horns are wonderful but have probably nothing to do with the origin of the word ivy.A thriller needs a climax. Unfortunately, I don’t have a true revelation up my sleeve, but one hypothesis seems acceptable to me. There was a prolific researcher named John Loewenthal. He offered numerous etymologies, all of which appear to be wrong. Scholars of his type are not too rare: they know a lot, have a vivid imagination, and publish like a house on fire. But when you begin to separate tares from wheat in their heritage, only tares remain. That’s fine: it’s the thought that counts. Once again, as I have done in the past, I would like to celebrate the slogan launched by the old revisionists of classical Marxism: “Movement is everything, the goal is nothing.” I am not sure that Eduard Bernstein formulated this slogan, but the problem of authorship need not bother us here.

Marx and Engels hated the revisionists because those heretics hoped to achieve socialism without the use of force. Never mind socialism: the revisionist principle works well for a diligent student of etymology. Both Loewenthal and I plodded along (“movement is everything”), and once, I believe, I ran into a good idea of his. He compared Old Engl. īfig and āfor “bitter, pungent; fierce.” Ivy emerged from his comparison as a bitter plant, thanks to the taste of its berries. Or perhaps ivy was thought of as a poisonous plant, like Old High German gund–reba, which means “poisonous grass.” It is a tempting etymology, provided it is correct. For the truth is, as always, evasive. After all, ivy could be a substrate word, like ibex! Or it could be a migratory word, disguised by its attested forms beyond recognition. Barring such agnostic conclusions, for the moment, ivy “bitter plant” is the best interpretation of this hard word known to me.

Images: (1) Harvard by Monica Volpin, Public Domain via Pixabay. (2) “Aberlemno” by Xenarachne, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. (3) hagengebirge capricorn by Nationalpark_Berchtesgaden, Public Domain via Pixabay Featured image: Heather by Didgeman, Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post From good wine to ivy appeared first on OUPblog.

Aldo Leopold at 130

“There are some who can live without wild things, and some who cannot. These essays are the delights and dilemmas of one who cannot.” [Aldo Leopold, from the foreword to A Sand County Almanac (1949).]

The eleventh of January marks the 130th anniversary of the birth of conservationist, ecologist, and writer Aldo Leopold. As one of Leopold’s biographers, I have become accustomed over the years to marking these milepost dates. They tend to bring forth a strong pulse of articles, commentaries, and editorials. Some are celebratory, perhaps built around a choice bit of Leopold prose:

“To arrive too early in the marsh is an adventure in pure listening; the ear roams at will among the noises of the night, without let or hindrance from hand or eye. When you hear a mallard being audibly enthusiastic about his soup, you are free to picture a score guzzling among the duckweeds. When one widgeon squeals, you may postulate a squadron without fear of visual contradiction. And when a flock of bluebills, pitching pondward, tears the dark silk of heaven in one long rending nose-dive, you catch your breath at the sound, but there is nothing to see except stars.”

Some of the references are more wry, taking advantage of Leopold’s skill in subtly expressing consequential thoughts. “There are two spiritual dangers in not owning a farm. One is the danger of supposing that breakfast comes from the grocery, and the other that heat comes from the furnace.” From such seeds whole discourses — whole movements — can grow. And have.

Some items veer more toward topical issues, for there is never a shortage of conservation-related topics in the news, and Leopold is a go-to source for supportive quotations. This is especially the case at times when the core tenets of Leopold’s approach to conservation are at issue. Leopold emphasized, in his work and in his writing, the fundamental need in conservation for scientific research and information, interdisciplinary understanding, community participation, and public education. He called for more comprehensive definitions of economic value, and for an expansion of our ethical sphere to embrace our relations to the entire “land community.” These remain contentious arenas of debate, and Leopold’s views remain trenchant:

“One of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives alone in a world of wounds. Much of the damage inflicted on land is quite invisible to laymen. An ecologist must either harden his shell and make believe that the consequences of science are none of his business, or he must be the doctor who sees the marks of death in a community that believes itself well and does not want to be told otherwise.”

It is hard to imagine Leopold’s continuing ripple effect in the world apart from the role that his published works has played in advancing it. Seventy years ago this year, Leopold completed and submitted the manuscript for A Sand County Almanac (1949), his highly influential collection of essays. It is estimated that more than three million copies have been sold over the decades, and it has now been translated into a dozen languages. Over the last twenty-five years, as interest in Leopold’s work has continued to grow, several collections of his other articles and essays and previously unpublished works have appeared. And through a partnership of the Aldo Leopold Foundation and the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the rich archival collection of Leopold’s papers have been digitized and made available to scholars.

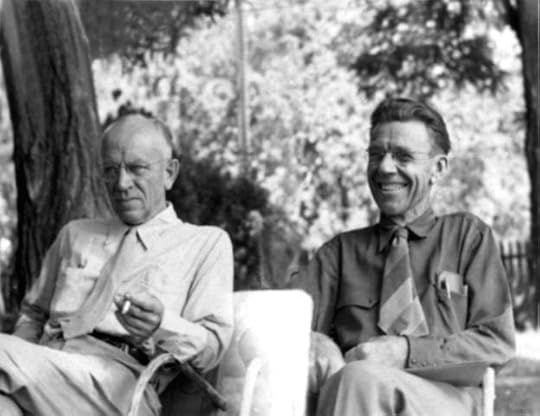

Aldo Leopold (right) with Olaus Muire at the annual meeting of The Wilderness Society Council in Old Rag, Virginia, 1946. United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Aldo Leopold (right) with Olaus Muire at the annual meeting of The Wilderness Society Council in Old Rag, Virginia, 1946. United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Five years ago I was invited by Oxford Bibliographies to prepare the entry on Leopold for its “Ecology” section—a far more daunting task than I anticipated! Leopold’s own body of writings was large and diverse. Scholarship on Leopold, his many areas of influence, and especially his concept of a land ethic has expanded tremendously in volume and scope, over many decades. After realizing that I could hardly embrace the whole ocean, I made my best effort to distill it.

Scholarly interest in Leopold has hardly slowed since then. And so Oxford Bibliographies came knocking at my e-mail box again last summer, inviting me to update the entry. Over the last several weeks I have been at work on that job, surveying and summarizing the last five years of published works on Leopold. Collectively, they reveal much about the state, not only of Leopold scholarship, but of current thinking in conservation, ecology, and environmental studies. We find scholars from a dozen different fields carefully examining, exploring, criticizing, and extending Leopold’s thinking—on such diverse topics as water and marine ethics, global climate change and sustainability, human health, urban studies, ecological economics, and the cultural context of Leopold’s early conservation advocacy. Most recently, Estella B. Leopold published a personal account of life in the Leopold family. The youngest of the five Leopold siblings and a distinguished paleoecologist, Estella at the age of 90 remains active as an emeritus faculty member at the University of Washington and as a board member of the Aldo Leopold Foundation in Wisconsin.

It seems that Aldo Leopold, at 130 years old and counting, still inspires a sense of wonder, still suggests creative responses to our sobering social and environmental challenges, and still demands that we think critically about the “delights and dilemmas” that our relationship to the living world entails.

Featured Image credit: The shack near Wisconsin Dells, Wisconsin, where Aldo Leopold spent time and was inspired to write A Sand County Almanac. Photo by Jonathunder, GFDL 1.2 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Aldo Leopold at 130 appeared first on OUPblog.

Evaluating the long-view forecasting models of the 2016 election

In an earlier paper this year, we argued that election forecasting models can be characterized by two ideal types, called short-view models and long-view models. Short-view forecasting models are predominantly based on polls, and are continually updated until election day itself. The polls themselves are often interviewing respondents right up until a couple of days before the election. The long-view models apply theory and evidence from the voting and elections literature, and make forecasts months before the actual election. Our earlier paper explored the pros and cons of short-view and long-view forecasting, and we argued then that both views have value. What does the 2016 election result tell us about the polls, and short-view and long-view forecasting?

We start by looking at the short-view forecasts that predicted the Electoral College vote as listed in The Upshot on The New York Times website. All of these short-view models predicted Clinton had at least a 70% chance of winning the Electoral College vote using state and national polls. The Princeton Election Consortium even went so far as to predict a Clinton win in the Electoral College with 99% certainty. The Electoral College vote forecast is where the short-view forecasts all missed the mark.

As these short-term forecasts were based on state and national polls, the size of these errors can be better understood by scrutinizing some of the individual polls on the eve of the election. Each poll’s margin of error (MoE) at the 95% confidence level is key to understanding how accurate it was on election eve. The MoE at the 95% confidence level means that if the survey was done 100 different times, we would expect the actual percentage result to be within the estimated MoE in 95 of those 100 different surveys. In other words, the MoE tells us the range of values for the “actual” value with 95% confidence. If then the actual vote for Trump falls within the poll’s margin of error, then the poll was not too far off the mark. Take the battleground state of Michigan as an example. In the November Detroit Free Press poll, the reported MoE was plus or minus 4%, and Trump’s poll result was 38%. Thus, according to the poll, the “actual” value was between 34 and 42%. Trump won 47.6% of the vote in Michigan, so the Detroit Free Press was not very accurate. In five state polls taken in November, Trump’s vote percentage (47.6%) was inside the margin of error in only one of the five polls. Michigan’s result shows that if election eve polls are any indication of overall poll accuracy, then there is significant room for improvement.

Turning to the long-view forecast models (including what we called synthetic models), we evaluate how well they performed in the 2016 presidential election. These models are based on historical outcomes dating back to 1948 and earlier, but the 2016 election was certainly like no other in recent memory. So how well did these comprehensive long-view models do in their forecasts?

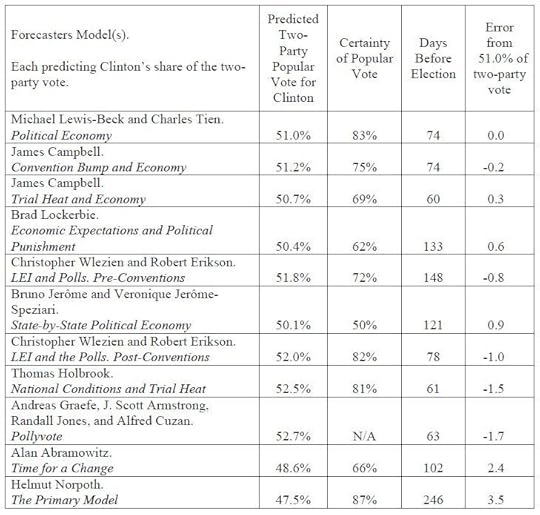

Each model set out to predict the incumbent party’s share of the two party vote (which was 51.0 as of December 2nd, 2016). Table 1 lists all eleven 2016 published forecasts in PS: Political Science and Politics put out by nine different forecasters (or teams of forecasters), and shows that seven of the eleven forecasts were within one percentage point of the reported vote. Another three forecasts were within two-and-one-half percentage points of the actual outcome. Only one forecast missed by more than three points. Our Political Economy model forecast of 51.0 appears exactly right, as of this date. Thus, the performance of the long-term forecasts is remarkable.

Table 1, Political Science Long-view Forecast Models by Charles Tien and Michael S. Lewis-Beck. Used with permission

Table 1, Political Science Long-view Forecast Models by Charles Tien and Michael S. Lewis-Beck. Used with permission

Taking into consideration that Table 1 also shows the number of days before November 8 that each forecast was made, with the median number of days at 78, the long-view forecast models’ relative accuracy is even more impressive. The earliest forecast by Helmut Norpoth was made 246 days before the election, and the latest was by James Campbell, 60 days before the election. These long-view forecasts were all made well before the short-view forecasts settled on their final predictions on the morning of 8th November.

Earlier this year we warned that the short-view forecasts can go wrong if the polls go wrong. Short-view models are based on the polls until, in the end, nothing else seems to matter. The 2016 polls, especially the state polls, led the short-term Electoral College forecasters astray. The long-view forecast models, relying on political science theory and historical data, and constructed with considerable lead time with only occasional updating, fared quite well this election. We know from past experience, however, that one is only as good as one’s last forecast, and 2020 already looms too close in the near future for forecasters to rest easy.

Featured image credit: October 22: Election by Shannon. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Evaluating the long-view forecasting models of the 2016 election appeared first on OUPblog.

African military culture and defiance of British conquest in the 1870s

The Anglo-Zulu War of 1879 is undoubtedly the most widely familiar of the Victorian campaigns of colonial conquest, those so-called “small wars” in which British regulars were pitted against foes inferior in armaments, operational sophistication, and logistics. It is also by far the most written about, some would say to the point of exhaustion.

Yet, in poring over military minutiae, historians of the Anglo-Zulu War have all too often failed to note that it was not fought in isolation. In 1879 the Zulu kingdom was only one among several African polities in southern Africa forced to defend their independence when faced by the accelerating British determination to unify the sub-continent in a confederation of states under imperial control.

There was no place in this design for sovereign African states. So, to neuter their military capabilities and shatter their political coherence, imperial strategists embarked on a concerted, interrelated, and sometimes overlapping series of campaigns against them. Some historians now regard this offensive as the First War for South African Unification, the second being the Anglo-Boer (South African) War of 1899–1902.

Within the concentrated span of three years, the British crushed the Ngqika and Gcaleka amaXhosa in the Ninth Cape Frontier War of 1877–1878, subjugated the Griqua, Batlhaping, Prieska amaXhosa, Korana, and Khoesan in the Northern Border War of 1878, shattered the Zulu kingdom in the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879, and extinguished Bapedi independence in the First and Second Anglo-Pedi Wars of 1878 and 1879.

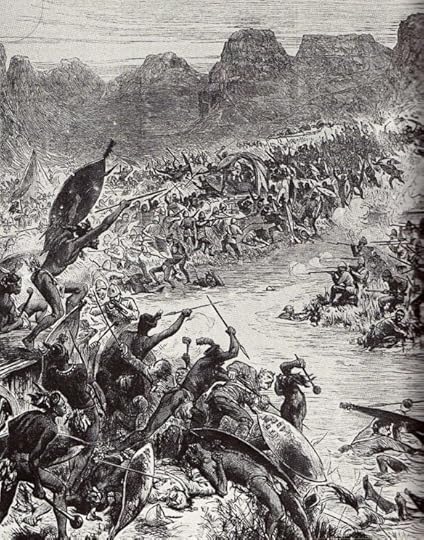

The Battle of Intombe, fought on 12 March 1879 between Zulu forces and British soldiers, image from The Illustrated London News. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The Battle of Intombe, fought on 12 March 1879 between Zulu forces and British soldiers, image from The Illustrated London News. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.In one sense, there was nothing new about these conflicts. Intermittent, piecemeal colonial encroachment had begun with the Dutch in the Cape in the mid-seventeenth century, and tough and often skillful African resistance had frequently delayed or even staved it off. But in the late 1870s, African rulers were unprepared for the unrelenting determination of the British offensive. In this crisis, all the indigenous armies of the sub-continent, vary as they might in everything from numbers and armaments to customary tactics, faced the same urgent challenge. How were they to adapt their traditional ways of war (honed effectively enough for combat against each other) to the ever-growing European military threat?

Despite differing responses ranging from set-piece battles to guerrilla warfare, and from a reliance on traditional sharp-edged weapons to the adoption of firearms, there was a connecting thread that ran through the interwoven pattern of the resistance of these southern African societies to the British assault. That was a commonly held military culture through which notions of military honour and manhood inspired and sustained African warriors in their doomed defence of their homes and independence.

Although African military culture differed in detail from society to society, a generally accepted system of military values defined the warrior’s place in the social order and legitimized aggressive masculinity and the violence of war in which face-to-face, heroic combat was the ultimate test of courage and manliness. Indeed, masculine virtue and honour (as in many other parts of the world) were closely bound up with the prowess of military heroes, and were the binding myths of the state itself, the cultural focus around which the community adhered.

Bearing in mind this cultural universe, it is hardly surprising that African rulers in southern Africa entirely subscribed to the pervasive warrior ethos and notions of honour. Whether under threat of attack by an African or European foe, the issue for a king was always more than a question of sovereignty or expediency: it was a matter of honour. A king was a war leader, first and foremost; his warriors were raised from birth to war and its stern demands. Rather than surrender like a coward without a fight, even in the face of hopeless odds, it was considered best by far to die honourably on the battlefield as befitted a true man and warrior.

This warrior ethos was fully shared by the African allies, levies, and auxiliaries serving with the British in the South Africa campaigns of 1877–1879. (There was nothing unusual in this, for the colonial conquest of Africa was substantially the work of locally raised indigenous forces commanded by European officers.) In undertaking military service with their colonial masters against fellow-Africans these, black forces were not merely looking after their own interests by choosing what seemed likely to be the winning side. Many of them also saw it as a means of maintaining their warrior traditions and sense of masculine honour under the colonial aegis. It was this military culture which inspired and sustained them, just as it did those Africans against whom they fought.

Featured Image Credit: The Battle of Gingindlovu on 2 April 1879, image from the Illustrated London News. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post African military culture and defiance of British conquest in the 1870s appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers