Oxford University Press's Blog, page 417

January 19, 2017

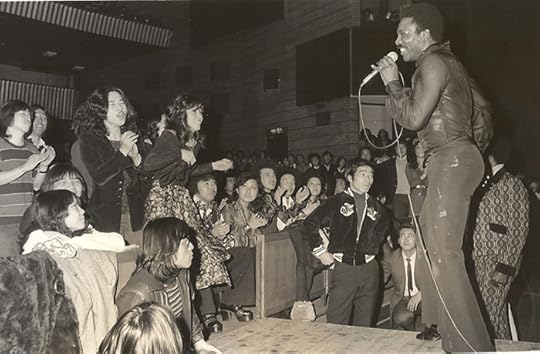

The legacy of Wilson “Wicked” Pickett [excerpt]

Today marks eleven years since the death of Wilson “Wicked” Pickett. Known for such hits as “In the Midnight Hour,” “Land of 1,000 Dances,” and “Mustang Sally,” Pickett claimed his place as one of history’s most influential R&B figures when he was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1991. After a successful fifty-year career in the music industry, Pickett was laid to rest in Louisville, Kentucky at the age of 64.

In the below excerpt from In the Midnight Hour: The Life and Soul of Wilson Pickett, author Tony Fletcher describes the aftermath of Pickett’s death.

The obituaries for Wilson Pickett— and they were everywhere— inevitably balanced the good with the wicked. The Guardian in the United Kingdom described him, accurately, as the “singer who revolutionized the sound of 60s soul.” Just about every paper of record made some reference to his troubled 1990s, his jail terms, or what the Washington Post referred to simply as his “volatile personality.” Aretha Franklin was among the surviving soul stars who paid tribute. “One of the greatest soul singers of all time,” she said, a simple statement of which there could be surely no dispute.

The Washington Post was one of the many papers to report that Pickett was survived by “his fiancée, Gail Webb.” His family felt otherwise about that description. Gail moved out of the Ashburn house and into a nearby hotel prior to a private service held at the Loudoun Funeral Chapel on January 21. Among the attendees that day were many of the musicians who had played under the name of the Midnight Movers; Margo Lewis and Chris Tuthill; Bo Diddley, who had become good friends with Pickett over the years of sharing stages and hotels and airplanes with him; and Don Covay.

Courtesy of the Wilson Pickett, Jr. Legacy LLC.

Courtesy of the Wilson Pickett, Jr. Legacy LLC.Wilson Pickett’s body was transported to Louisville, Kentucky. There, at the Canaan Christian Church, on January 28, hundreds gathered to pay respects and mourn his passing. The service proved memorable: sister Emily Jean led a rousing gospel tribute in honor of those Sunday morning walks 260 through the Prattville backwoods en route to Jericho Baptist, and brother Maxwell offered measured words of comfort that recognized both Wilson’s brilliance and his difficulties. Stephanie Harper read from the scriptures. Dovie Hall sat quietly in the pews. Sir Mack Rice and Willie Schofield of the Falcons, with guitarist Lance Finnie, paid tribute, and although Aretha Franklin and Solomon Burke, each listed on the printed program, did not in fact attend, the mourners received an impromptu, show-business eulogy from a sequin-clad Little Richard.

“Wilson, he’s an innovator, an emancipator,” said Richard. “He’s supposed to be in the Hall of Fame; he’s one of the ones that paved the way for all these people you see, like Puff Daddy, and Will Smith, and Eminem, and Kanye West. If it weren’t for him, they wouldn’t be there.”

The official eulogy was delivered by the Reverend Steve Owens, imported from Maxwell Pickett’s home church in Decatur, Georgia. Maxwell and Owens had become good friends once it was discovered that the preacher had played in a soul band prior to taking up the church— and that he had, of course, covered many a Wilson Pickett song in his day. As Owens reached the climax of his eulogy, he sang the refrain from “Land of 1000 Dances.” Soon enough he had the whole church chanting a joyous last hurrah: “Na, na- na- na- na, na- na- na- na- na- na- na- na- na- na …”

At the conclusion of the service Wilson Pickett’s casket was taken to the mausoleum in the Evergreen Cemetery, close to his mother, per his request. His eternal resting place was engraved with an image of his face in its prime and inscribed with the Lord’s Prayer.

There were to be further tributes over coming weeks and months, including a public memorial concert at B. B. King’s in New York. And family drama resumed. Gail Webb was bought out from her position as coexecutor, and Maxwell Pickett was left to administer a Wilson Pickett Jr. Legacy company with an associated scholarship fund. A trust fund was established for Wilson’s four children, the only family members to benefit directly from his wealth; part of Michael Pickett’s quarterly inheritance would make its way directly to Dovie Hall, who had served as his mother throughout his formative years.

Pickett his thirtieth birthday party, 1971. Pictured singing with his sister, Emily Jean. Courtesy of the Wilson Pickett, Jr. Legacy LLC.

Pickett his thirtieth birthday party, 1971. Pictured singing with his sister, Emily Jean. Courtesy of the Wilson Pickett, Jr. Legacy LLC.Barely a week after he was interred, Wilson Pickett was honored at the Staples Center in Los Angeles, where he finally received the recognition from the Grammys that he had always sought. The subdued awards ceremony focused largely on the devastation wrought the New Orleans musical community by Hurricane Katrina the previous summer, but at the conclusion of the evening a one- off supergroup assembled to play the soul anthem to eclipse them all: “In the Midnight Hour.” The lineup included Dr. John on piano, The Edge of U2 and Elvis Costello on guitars, and Bonnie Raitt, Yolanda Adams, and Patti Scialfa on backing vocals. Singing lead was one of the last remaining great voices of Pickett’s generation, Sam Moore, who delivered a stirring, heartfelt rendition of the first verse. He was joined for the second verse by Bruce Springsteen and for the finale by the Soul Queen of New Orleans, Irma Thomas.

For all the hundreds of times that “In the Midnight Hour” had been performed on television— and for the hundreds of thousands of times that it had been covered in bars, clubs, theaters, concert halls, and stadiums around the world— this was an especially spirited, emotionally evocative rendition. “This is for the Wicked Pickett,” roared Springsteen as the second verse gave way to the famous horn instrumental, and it was evident that he was doing so not just on behalf of the musicians on stage, but on behalf of every soul fan who had ever been touched by one of the greatest voices and, yes, one of the most volatile personalities of the last fifty years.

Wilson Pickett had gone on home. Lord, have mercy.

Featured image credit: untitled by Markus Spiske. CC0 Public Domain via Pexels.

The post The legacy of Wilson “Wicked” Pickett [excerpt] appeared first on OUPblog.

Trump should build on Obama’s legacy in Myanmar

To the surprise of many political observers around the world—both critics and supporters alike—Donald Trump was elected the 45th president of the United States on 8 November, 2016.

If the president-elect is going to follow his election campaign promises, he will focus on domestic politics over relations with the international community, including the US “Pivot to Asia”, one of President Barack Obama’s central foreign policy initiatives.

The pivot was meant to be a strategic re-balancing of US interests from Europe and the Middle East towards East Asia. With its pivot program, the Obama administration signalled a shift from his predecessor’s focus on the Middle East. Myanmar under the Bush administration had been under economic and political sanctions.

The Obama administration’s Myanmar policy started in September 2009 when it officially announced a nine-month-long policy review to start engaging the military junta while retaining sanctions.

The policy shift was followed by the US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s visit to Myanmar in December 2011, which was the first US secretary of state’s visit to the country in 50 years. The visit was made possible by Myanmar’s progress toward democratic reform, particularly the release of political prisoners, including Aung San Suu Kyi.

The secretary of state’s visit was followed by the appointment of Derek Mitchell as the new US ambassador to Myanmar on 29 June 2012. The US downgraded its diplomatic representation in Myanmar to charge d’affaires following a military coup in 1988 and a violent crackdown on pro-democracy protests, as well as due to the nullification of the 1990 general election result, which was overwhelmingly won by the National League for Democracy (NLD).

In a sign of progress in the bilateral relationship, President Obama first visited Myanmar in November 2012, making him the first sitting US president to visit the country. Obama then visited again in November 2014, partly because Myanmar hosted the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and the East Asia summit which Obama had to attend.

The bilateral relations improved further in the aftermath of the November 2015 election which the NLD won in a landslide. The NLD’s electoral victory eventually led to the lifting of the long-held US sanctions on Myanmar on 14 September 2016. Subsequently, the Obama administration terminated the National Emergency with respect to Myanmar and revoked the Executive Order-based framework of the Myanmar sanctions program. The US also restored the Generalized System of Preferences trade benefits to Myanmar in light of progress on a number of fronts, including strengthening protection for internationally recognised worker rights.

…it can be guessed or speculated from his election campaign that Trump is unlikely to take a strong personal interest on Myanmar like his predecessor.

However, the US arms embargo under the International Traffic in Arms Regulations and other stringent export controls remain in place. There is also a continued visa ban on a list of individuals viewed as being linked to the Myanmar armed forces, known as Tatmadaw. In addition, there are Specially Designated Nationals located in Myanmar who remain listed under authorities related to North Korea and narcotics trafficking.

With the lifting of sanctions, the US commits to continued cooperation in addressing challenges, such as strengthening the rule of law, promoting respect for human rights, countering human trafficking, combatting corruption, and advancing anti-money laundering efforts and counter-narcotics activities.

President-elect Donald Trump has not made any public statement on what his administration’s policy toward Myanmar would be. But it can be guessed or speculated from his election campaign that Trump is unlikely to take a strong personal interest in Myanmar like his predecessor. For example, Obama established a close rapport with Suu Kyi and also visited the country twice.

But the overarching US policy on Myanmar will largely remain the same. Though a Republican in the White House and a Republican-dominated Congress will make things easier if the US government does choose to implement policy on Myanmar. Republican senators such as John McCain of Arizona and Mitch McConnell of Kentucky have been staunch supporters of democracy and human rights in Myanmar.

Whether the Trump administration will have an interest or focus on Myanmar will also depend on America’s broader policy toward the Asia-Pacific region.

But as the leading advocate of human rights and democracy around the world, the US needs to continue its unfinished objectives in Myanmar, especially in areas such as the consolidation of democracy, the peace process between the government and ethnic armed groups, and on the sensitive question of the Rohingya issue. Challenges remain in the democratisation process, especially in areas of institutional building, constitutional amendment, as well as the need for gradually reducing the role of the military in politics.

The second phase of the 21st century Panglong conference is due to begin in the month of February 2017 but heavy armed clashes continue between the Myanmar Army and members of the Northern Alliance—the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA), the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), and the Arakan Army (AA).

Under the present circumstances, it is unlikely that majority of the armed groups will attend and or participate in the upcoming conference. It must be remembered that the first Panglong conference in 1947 failed partly due to the non-participation of all major ethnic nationalities of the time. Only representatives from the Chin, Kachin, and Shan ethnic groups signed the Panglong agreement with the Burmese government representative Aung San to form an interim government. Soon after the country’s independence, insurgency movement started that continues until today.

Another major problem where the Trump administration should diligently help or at least offer assistance is on the question of the Rohingya conundrum. One way to do that would be to encourage the Kofi Annan-led commission, which the NLD government appointed to find a long-lasting solution to the problem.

Featured image credit: Hluttaw Complex, Naypyidaw by Peerapat Wimolrungkarat. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Trump should build on Obama’s legacy in Myanmar appeared first on OUPblog.

January 18, 2017

Approaching “brash”

Two weeks ago, I promised to deal with the word brash, but, before doing so, I would like to make it clear that we are approaching a minefield. Few people, except for professional etymologists, think of words in terms of phonetic or semantic groups. (With regard to phonetics, note my recent series on kl-words, from clutter and clod to cloud and cloth.) Inquisitive students ask: “What is the origin of brouhaha, hullabaloo, and shenanigans?” It seldom occurs to them that brouhaha may be in some obscure way related to other br– words, that, to discover the derivation of hullabaloo, one should cast a wide net and consider other such slangy formations, and that for explaining shenanigans it is necessary to study certain and possible borrowings from Irish. The phonetic aspect is the hardest. So to repeat: Can brouhaha be “related” to bread and brother?

In the past, I have discussed only two br-words: brisket and brothel. The origin of both is problematic. The whole br-page even in such a small reference book as The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology should strike awe in a word lover. A caveat: etymological dictionaries have mastered, and mastered to the full, the art of talking a lot and saying little. The most common trick is to list numerous cognates and stop, as though knowing that a word has relatives in three or more languages is an etymology. Sometimes those cognates are traced to a hypothetical root, but this root (Germanic or Indo-European) is an abstraction from those same cognates and does not increase our stock of knowledge. Finally, quite often we learn that a certain word is from Latin or French, but it may appear that the origin of the Latin or the French word in question has not been discovered: the answer is only looming (excuse me for this unsubtle reference to one of my previous posts), which means “appearing in the distance.” A good etymology sets out to explain how the recorded form came into being and why it means what it does. Etymologists reach the desired destination on the rarest occasions. All this is not an innuendo but an exercise in self-criticism.

What then do we find on the br-page? Brother is a kin term, with congeners in half of the world, and something is known about it. It certainly had a suffix (compare Latin fra-ter, along with father / pa-ter and daugh-ter), which probably designated the inclusion of this man in a certain group (“fraternity”), but what is fra- ~ bro-? And bread? It is a West Germanic word, and two main etymologies of it compete. One may be correct, or both may be wrong. Brother and bread are aristocrats in the world of words, because they are so well-connected; yet we still cannot explain why people called “brother” brother and “bread” bread. Elsewhere, we run into a host of commoners and poor relatives.

Not by bread alone, but it would be nice to know why bread is called bread.

Not by bread alone, but it would be nice to know why bread is called bread.Take bribe, for instance. It is nice to know that the word is French, but English speakers have proved themselves good pupils (to be sure, they have had ample time to learn their lesson). In the fourteenth century, bribe meant “to steal” and acquired its present sense two hundred years later. Since words for stealing are often slang, it is no wonder that their origin tends to be lost. Incidentally, both steal and thief are also words of obscure etymology. Next comes broad. The adjective is like the noun bread: Germanic and of unknown origin. As to broad “woman,” several ingenious conjectures have been offered. However the word may have originated, the sad path from “woman” to “prostitute” is short and has numerous analogs (historical linguists call this process deterioration of meaning, as opposed to the much rarer process known as amelioration of meaning; apparently, to improve is harder than to degrade). Even whore (with it non-historical initial w-) is related to Latin cārus “dear” (the Gothic Bible, a fourth-century Germanic text, already had the noun hors “adulterer”: alas, love in the past did not always have romantic overtones).

I deliberately stay with the most common, universally known words. Brick is around to offer its services. However, its neighbors are more obscure. Above it in my dictionary stands bric-à-brac, and under it bricole “a military engine of catapult” appears (I am sure many more people know bricole only as a tennis or billiards term). If you have never encountered bricole, you may have heard French bricolage: in English, it means “construction of an artifact from chance available materials” (bricoler “to putter about”). The word was made famous by the French structuralist Claude Lévi-Strauss. At one time, his works were studied in all language departments. Now he is remembered by relatively few old admirers, which does not mean that the trends and fads that came later are better. Is bric-à-brac (which is French of course) sound-imitative? If so, then imitative of what? Producing bricks is serious business, different from bricolage and breaking. Also, the vowels of break (Old Engl. brecan) and brick do not match.

These children love bricolage. When they grow up they may (or may not) study the works by Claude Lévi-Strauss.

These children love bricolage. When they grow up they may (or may not) study the works by Claude Lévi-Strauss.Some of those vagaries could be disregarded if it did not turn out that bride is another word of unknown origin. Strange things happen here. Wife (Old Engl. wīf) was neuter (a word for “woman” was neuter? Indeed it was: see the post of 12 October 2011), and bride, which has cognates in all the Old Germanic languages, including Gothic, could sometimes mean “a married woman.” I am glad that yesterday does not begin with br-. Otherwise, our confusion would have been even worse confounded, for the cognates of yesterday occasionally meant “tomorrow” (in Gothic, it was the only sense of gistradagis). Hypotheses on the origin of bride exist, but they are full of acrobatics, and, as a general rule, very clever, intricate etymologies turn out to be wrong. By way of consolation, I can add that the adjective bridal poses no problems: it began its life in English as a compound noun: bride + ale (from ealu) and meant “wedding feast; wedding.” Later, the second syllable was shortened to –al and taken for a suffix. Such things happen not too rarely. Since we are speaking about feasts, it will be remembered that wassail goes back to wæs hæil and to earlier wæs hāl “be whole (healthy),” a salutation used when drinking to a guest’s health. Those are facts, not conjectures.

Here comes a bride all dressed in white, but at the moment she is in a brown study, for she does not know the origin of the word “bride.”

Here comes a bride all dressed in white, but at the moment she is in a brown study, for she does not know the origin of the word “bride.”The names of metals are among the hardest to investigate. Brass (of West Germanic provenance) is still another word of unknown etymology. Brazen is certainly related to it in both its literal and figurative senses. Brazier “a worker in brass” apparently contains the same root. But brazier “a pan for holding burning charcoal” is from French. French braise means “hot coals”; hence Engl. braise “to cook in a closed pan.” Although this word is believed to have been borrowed from Germanic, this fact sheds no light on brass.

My list goes on and on, and the turn of brash will come round very soon, but today my aim was to show that etymological dictionaries can sometimes be read like novels. I have presented a few passages from the chapter “Words Beginning with br-” Think of bring, bridge, brogue (whichever sense), brat, the noun brook, the mysterious brumby “a wild horse in Australia,” and Johnathan Swift’s Brobdingnag, and you will never be bored or go broke. Br– may express all kinds of feelings or nothing at all. Therein lies the beauty of the present exercise in bricolage.

Images: (1) Bread by jacqueline macou, Public Domain via Pixabay. (2) “Portrait of Claude Lévi-Strauss taken in 2005” by UNESCO/Michel Ravassard, CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. (3) Children-sandbox by Arek Socha, Public Domain via Pixabay. (4) Bride by opertv, Public Domain via Pixabay. Featured image: “Bric-a-brac” by xlibber, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Approaching “brash” appeared first on OUPblog.

Can we end poverty by 2030?

Is it possible to end extreme poverty? And by 2030?

That’s the aim of the first of the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). These were adopted by all nations and have begun to drive conversations at global gatherings, including those that I have contributed to in recent weeks.

This ambitious goal builds on the dramatic fall in worldwide poverty since 1990. Then, over one-third of the world’s population lived on less than $1.25 per day, adjusted for purchasing power parity or what a dollar buys in a country. That measures the level of abject poverty, and has since been adjusted to $1.90 per day. Based on these measures of extreme poverty, we are at a historic point where just 1 in 10 people in the world are poor.

It means that over 1 billion people have been lifted out of extreme poverty since 1990. The halving of the global poverty rate happened more quickly than the UN’s Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) had envisioned. The MDGs aimed to halve poverty worldwide from 1990 levels by 2015 – it was achieved in 2010.

So, the current SDGs are more ambitious. The aim is to end extreme poverty in just 13 years, by 2030. It means lifting the remaining 767 million poor out of poverty. But, what has worked before may not be enough this time.

In other words, most of the poverty reduction occurred because of China’s economic growth, as well as the rest of the East Asian region – countries which are on course to ending poverty. The poverty rate in East Asia fell from 61% to 4% between 1990 and 2015. In South Asia, it’s dropped from more than half (52%) to 17%.

By contrast, the number of poor isn’t declining in Sub-Saharan Africa and more than 40% of Africans still live in abject poverty. This is despite Africa registering the second fastest economic growth rate after only Asia during this period. The implication is that though it has worked largely for China and other Asian nations, economic growth isn’t enough to reduce poverty. High levels of inequality, for instance, mean that an economy can grow and not help the very poor.

So, that means eradicating poverty requires new strategies, in addition to what has been tried in the past couple of decades.

The aim is to end extreme poverty in just 13 years, by 2030. It means lifting the remaining 767 million poor out of poverty.

Half of the 767 million poor live in Africa and one-third are found in South Asia. The remaining poor dwell in East Asia, Latin America, and Eastern Europe, all regions which are on track to end poverty. Thus, the poor in Africa and South Asia should now be the focus, and devising economic growth that helps the poorest will require new approaches.

For instance, reducing income inequality should be a higher priority. That typically requires redistributive policies, but also pre-distribution ones such as mandating education to better equip the workforce.

Also, capital accumulation tends to be the engine of growth for industrialising nations, so investment funds are needed. This can come from public and private sources, and usually involves both governments and businesses working together to get financing into countries to fund entrepreneurship and infrastructure.

How these funds are deployed, of course, is where novel strategies are particularly needed. For instance, effective deployment of funds requires an understanding of the needs of the locality. Some of the most knowledgeable of a community’s needs are found in civil society organisations. NGOs or non-governmental organisations of any stripe can, for instance, help transmit the needs of a locality to government and businesses so that funding and resources can be used more effectively to foster economic growth. There is also a degree of accountability from smaller groups rooted in a community, as much of the evidence from social capital studies show.

Of course, there is not one recipe for economic success. But, involving more participants with a stake in society is worth considering. After all, policymakers and businesses have increasingly sought feedback from their citizens and customers about governance and needs. It’s just a step further to encourage individuals to become involved to help grow their communities.

Governments do not have all the answers, nor do businesses. Working with communities to support economic growth would be a natural step.

Without trying more eclectic ways of thinking about growth strategies, poverty is likely to persist. To realise the ambition of living in a world without extreme poverty will require trying something different and more collaborative going forward.

Featured image credit: Money coins by JerzyGorecki. Public Domain via Pixabay

The post Can we end poverty by 2030? appeared first on OUPblog.

The Millennials’ God

The Millennial Generation—consisting of those individuals born between 1980 and 2000—is an oddity when it comes to religion. On the one hand, its members are leaving organized religion in unprecedented numbers. On the other hand, they are not exactly unbelievers.

According to a survey conducted in 2014 by the Pew Research Center, the modal 18-29-year-old identifies as “nothing in particular”: not part of a distinct religious group, but not atheist or agnostic either. Most believe in God with some certainty. Yet it is unclear from this survey just what kind of God they mean, and how they ‘experience’ that God in which they believe.

This puzzle relates to two larger narratives often told about the Millennial Generation. The first narrative claims that because of their many privileges, Millennials are self-focused, immature, and afraid to make strong commitments. An alternate narrative posits that due to growing economic uncertainty and inequality, Millennials are self-reflective, spiritually attune, and unwilling to compromise on core values of self-fulfillment.

The exodus from organized religion generally fits the first narrative: Millennials are the ultimate spiritual individualists who avoid faith commitments. They are the Marlboro men and women of American spirituality. The persistent belief in God fits the second narrative: Millennials are insatiable soul searchers, intrigued by the unseen and unscientific. They like to ask the big questions while rejecting easy answers.

Yet what if these conflicting narratives could be integrated by looking more closely at their patterns of spirituality? What if Millennials seem less religious because they are dissatisfied with the categories of belief that made sense to earlier generations?

Millennials are the ultimate spiritual individualists who avoid faith commitments

Take the issue of God, for example. In survey data from the National Study of Youth and Religion, a cohort of young adults age 24-29 report on their views of God. The categories provided by the researchers include a “personal being involved in the lives of people today”; someone who “created the world but is no longer involved in it”; and something that is “not personal, but something like a cosmic life force.” As in the Pew Center survey, about a third identify as “not religious”; but among these, 16% ascribe to a personal God, and another 27% reject any of these views, while also rejecting the label of atheist or agnostic.

When asked about how they relate to God, an even clearer picture emerges. Millennials tend to be deeply engaged with God and have lots of positive experiences of God. Many of them have a felt and experienced bond with God, not unlike a human-to-human bond, which is distinct from strong religious identities or theological beliefs.

These bonds are multi-faceted. There is evidence they vary along dimensions of intimacy, consistency, anxiety, and anger. Experiences of intimacy and consistency are the most common, suggesting that on the whole Millennials’ experiences of God produce positive emotions. For example, 72% of the survey sample agree with the statement, “I feel like I can always rely on God,” which is an indicator of consistency in the bond. 67% agree with the statement, “I feel God is a close companion in my life,” which is an indicator of intimacy.

These dimensions also go together in interesting ways. While those who are high on intimacy and consistency are lower on anger, they are even higher on anxiety, suggesting that a strong bond with God is also one they are more likely to worry about. This makes sense—we are often anxiously protective of the things we value most. It is interesting, though, to see it play out in Millennials’ relationships with the divine as well.

Finally, bonds with God are not exclusive to those who identify with a religious tradition. 13% of those with no affiliation agree with the statement above about always relying on God, and 11% of those with no affiliation agree with the statement above God being a close companion.

Thus, what Millennials say about their bonds with God in part subverts the narrative about them being highly individualistic or secularized. We see lots of similarity in their responses, suggesting their faith might not be as “individualized” as suspected; and we see lots of positive experiences of God, suggesting they are far from fully secularized. It remains to be seen whether these bonds with God will result in greater interest in organized religion down the road. Nevertheless it is clear that God matters to today’s Millennials, and their God is a distinctly personal one.

Image credit:“Audience concert” by Unsplash. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post The Millennials’ God appeared first on OUPblog.

January 17, 2017

Benjamin Franklin and the sea

Everyone knows about Benjamin Franklin. His revolutionary electrical experiments made him famous, and the image of the kite-flying inventor spouting aphorisms have kept him so for more than two centuries. His Autobiography could be considered a founding document of the idea of America, the story of a poor but bright young indentured servant who eventually became so famous he appeared before kings and on our money. Printer, journalist, community organizer, natural philosopher, satirist, diplomat—Franklin’s skill with language and his ability to shape it to personal, national, scientific purposes are unparalleled in American history.

But we don’t often think about Benjamin Franklin in his nautical context, as someone who drew inspiration and much of his expressive framework from the sea, though we should.

He had been born in maritime Boston on 6 January 1705 (old style), and professed in his Autobiography to having “a strong Inclination for the Sea” from an early age. Part One of his Autobiography, written in 1771, is filled with stories of young Franklin in and around the water, where he “learnt early to swim well, and to manage Boats, and when in a Boat or Canoe with other Boys…was commonly allow’d to govern, especially in any case of Difficulty.” His father, however, having already lost one son at sea, made sure to indenture Ben in a land-based trade to his brother, James, a Boston printer. Nevertheless, Franklin’s first published writing took the form of broadside poems about the recent capture of Blackbeard the pirate and the drowning of lighthouse keeper George Worthylake and his family.

He eventually fled from Boston to Philadelphia in 1723, and the next year found himself on another ship bound for London, where he would spend the next 18 months working in large printing houses, meeting writers and natural philosophers, and sketching out a plan for his life. Though he considered staying in London to open a swimming school (one of the great historical “what-ifs” of all time), he decided to return to Philadelphia in 1726, and he kept a daily journal of that voyage. It is a fascinating portrait of young Franklin trying on the persona of a gentleman traveler, and it is an excellent indicator of how the sea would shape his interests in natural philosophy, travel writing, and his own self-fashioning.

The journal is filled with keen observations on marine wildlife, including several varieties of birds, sharks, flying fish, and dolphins. Though not detached, Franklin’s style is objective, mimicking his heroes Bacon and Newton—he describes the bodies and behaviors of these creatures in minute detail.

Franklin also uses the picturesque language of travel literature to describe his departure: “And now whilst I write this, sitting upon the quarter-deck, I have methinks one of the pleasantest scenes in the world before me […] On the left hand appears the coast of France at a distance, and on the right is the town and castle of Dover, with the green hills and chalky cliffs of England.” He described the ships in Portsmouth harbor, and the castles and churches and cemeteries on the Isle of Wight, which Franklin toured while the Berkshire waited for favorable winds. Perhaps most importantly, he contrasted the illegible tombstones at the church of St. Thomas of Canterbury with the self-inscribed statue of Sir Robert Holmes, which Franklin approved as “a monument to record his good actions and transmit them to posterity.” He was no doubt beginning to think in terms of a maxim he later included in Poor Richard’s Almanac: “If you wou’d not be forgotten/ As soon as you are dead and rotten,/ Either write things worth reading,/ Or do things worth the writing.”

Throughout his life, nautical references dot his massive correspondence and nautical metaphors power some of his most compelling rhetorical performances. In his 1747 pamphlet Plain Truth, for example, Franklin transforms the literal project of building a ship to defend Philadelphia against French privateers into a political metaphor, calling on the pacifistic Quaker party to “quit the Helm to freer Hands during the present tempest.” In 1750 he admonished his friend and fellow natural philosopher Cadwallader Colden to place public responsibility over the private satisfactions of experiments: “Had Newton been Pilot of but a single common Ship, the finest of his discoveries would scarce have excus’d, or atton’d for his abandoning the Helm one Hour in Time of Danger; How much less if she had carried the Fate of the Commonwealth.”

Engraving of Captain Teach, also known as Blackbeard the Pirate, 1736. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Engraving of Captain Teach, also known as Blackbeard the Pirate, 1736. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Franklin’s mind never seemed to be far from water in some form. He exchanged numerous letters with his scientific colleagues hypothesizing about the relationship between the ocean and weather; the existence of a northwest passage to the Pacific; and the best designs for canals and water pumps. In one of his own rather bizarre experiments, carried out just before the outbreak of the Revolution, Franklin had oil poured from a longboat onto the sea at Portsmouh to determine whether oil poured on water in large quantities could calm rough seas. Though the experiment was a disappointment, Franklin learned that some waves are more likely to be quelled by people than others.

Franklin often compared the situation of Revolutionary America to being at sea and when time came to design the new Continental currency, he put a tempestuous sea on the face of the twenty dollar bill, with the waves all blown in one direction by a face with swollen cheeks. He explained, in the Pennsylvania Gazette, that the waves represented an “Insurrection” of the people that had been raised by the blowing of “Boreas, the North Wind,” a not-too-subtle jab at Lord North, England’s Prime Minister. On the back of the thirty dollar bill, a scene of good weather at sea seemed to hold promise of better times once the “wind” ceased.

After helping secure the peace after the Revolution, Franklin made his eighth and final ocean voyage, in 1785. During this trip, he began organizing what became known as his “Maritime Observations.” A compendium of nautical notes, it is remarkable for its scientific content. Franklin makes suggestions to account for wind resistance in an improved sail configuration and designs experiments to test them; he proposes improvements to anchor cables in order to keep them from being lost or doing damage to the ship; he suggests partitioning the holds of ships into separate watertight compartments to prevent a leak in one part of the ship from sinking the whole; he advocates building vessels constructed along the lines of the boats of Pacific Islanders, “the most expert boat-sailors of the world”; he explains how to prevent shipboard fires from candles, lanterns, and lightning, and how to avoid icebergs; and proposes moving through the water by the use of human-powered propellers. Franklin also discusses at length the Gulf Stream and its usefulness in navigation. He makes voluminous notes on surviving disasters at sea, including having emergency kites available for sailors to pull them across the water. He even proposed a design for soup bowls that would keep them from spilling on the rolling seas!

Franklin concludes his observations with a consideration of the ethics of navigation, prescribing the proper uses for man’s increasing mastery of the sea, asserting that the use of ships to transport slaves is abhorrent, and even risking men’s lives at sea to transport superfluities is difficult to justify morally.

In the final sections of his Autobiography, written and dictated during the last years of his life, Franklin moralized some of his own nautical experiences. He used a tense scene from William Penn’s Atlantic crossing to critique religious hypocrisy. He repeated a joke—about the man who refused to save himself by pumping on a sinking ship because it would save others he disliked—to display the stupidity of prejudice. And he recounted his third Atlantic crossing to explain how experimentation and shared authority could make ships efficient and help them avoid disaster. Franklin knew cooperation and tolerance were going to be important to the success of the new experimental American ship of state, and delivered that message drawing on a strong inclination for the sea that never waned.

Featured image credit: Benjamin Franklin National Memorial at the Franklin Institute, Philadelphia, PA. Picture by Michael H. Parker. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Benjamin Franklin and the sea appeared first on OUPblog.

The Mental Capacity Act 2005: an opportune time to reflect

More than a decade has passed since the Mental Capacity Act (‘MCA’) received royal assent. Described as a ‘visionary piece of legislation’, the MCA was a significant landmark on the legal landscape. It represented a triumph of autonomy by recognising that, as far as possible, people should play an active role in decisions about their welfare. At the core of the MCA is the fundamental principle that a person must be assumed to have decision making capacity unless it is established that he lacks it. The law therefore assumes that everyone has the ability to act and take decisions in accordance with their own interests, and affords primacy to individual priorities over paternalistic imperatives. Where a person lacks capacity – whether for reasons of learning disability, dementia, brain injury, or some other impairment of or disturbance in the functioning of the mind or brain – the MCA permits decision-makers to act on behalf of the person in accordance with his ‘best interests’. This means that, amongst other things, decision-makers must take into account the person’s past and present wishes and feelings, his beliefs and values, and any other factors that the person would be likely to consider, in order to act in a way which would likely give expression to the person’s autonomy. In this way, the MCA sought to empower people to make decisions for themselves, protect the vulnerable from the excesses of paternalism, and engineer a cultural shift in attitudes to mental impairment and incapacity.

In 2014, the House of Lords Select Committee for Health embarked on a wide-ranging review of the Act’s implementation and observed that its ‘empowering ethos’ had not been delivered:

‘Our evidence suggests that capacity is not always assumed when it should be [and]… The concept of unwise decision-making faces institutional obstruction due to prevailing cultures of risk-aversion and paternalism.’

The breadth of the MCA’s application was always going to pose formidable challenges in terms of managing compliance. The lack of enforcement mechanisms and organisations with overall responsibility for oversight of the MCA in practice was a primary criticism levied by the House of Lords Select Committee. With hindsight, it might also be said that the MCA’s decision-making framework has not quite been the panacea that was originally envisaged.

“To what extent has the MCA changed medical practice in England and Wales since its introduction?”

Tagged on to the MCA through the Mental Health Act 2007, Parliament introduced the Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (‘DOLS’), a new legal framework designed to close the so-called ‘Bournewood’ gap. DOLS have proved to be a controversial innovation, indeed, it is perhaps in this respect that the MCA’s recent legacy has been most problematic. The mechanics of the DOLS are labyrinthine and they have a complex relationship with the Mental Health Act 1983. Since the Supreme Court’s decision in Cheshire West and Cheshire Council v P, there has been an explosion in number of applications for DOLS ‘standard authorisations’ in England, adding further strain to an already-creaking system. Since they first came into effect in 2009, calls to reform the DOLS have grown in volume. In March 2017, the Law Commission will publish a final report on a recent consultation on the law of mental capacity and deprivation of liberty, with recommendations for a new framework of safeguards, which may redraw the boundary between the MCA and mental health law in England.

In light of the above developments, it occurred to the authors that the recent tenth anniversary of the introduction of the MCA was an opportune moment to reflect on the 2005 Act’s record so far and to evaluate its implications for the future. To what extent has the MCA changed medical practice in England and Wales since its introduction? How effectively has it been implemented? To what extent has the MCA’s unashamed emphasis on autonomy transformed professional culture?

Featured image credit: Brain by Jesse Orrico. CC0 Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post The Mental Capacity Act 2005: an opportune time to reflect appeared first on OUPblog.

The economic efficiency of fake news

Fake news has always had a presence American politics. No less an august figure than Benjamin Franklin partook of the practice. In 1782 Franklin generated a fake version of a real Boston newspaper, featuring his own inspired but false story about American troops uncovering bags of scalps to be sent to the King of England. As the story was spun, the scalps were intended to win the King’s friendship toward Native Americans. Franklin hoped that the story would turn British citizens against the Crown.

Since Franklin’s time, fake news has taken on different forms. In the past it has sometimes come from mainstream sources, as was the case with Yellow Journalism. Today, insurgent media are the primary source. However fake news is manifested, it is characterized by sensationalism—headlines that prove irresistible, content that is compelling, and a story line that “uncovers” a scandal or an injustice. In the 2016 election the fake news stories about Hillary Clinton’s health were a staple of the genre. One piece said she had a blood clot surgically removed from her brain and then, shortly thereafter, Clinton’s henchman killed the doctor, Sandeep Sherlekar, to keep him from exposing the surgery. Poor Dr. Sherlekar did die but he committed suicide after being indicted in an alleged kickback scheme involving urine samples.

More disturbing is the case of the gunman, Maddison Welch, who wanted to “shine some light” on a Washington pizza parlor, Comet Ping Pong, which fake news had identified as the center of a Hillary Clinton underage sex ring. Arrested after firing his gun inside the restaurant, Welch subsequently told the New York Times that “The intel on this wasn’t 100%.”

Although there is historical continuity in the fallibility of those who accept fake news as real, the business side of fake news today is fundamentally different than in the past. Whereas Ben Franklin had to find a printer, produce many copies of the fake issue, and then hand them out to friends to circulate, fake news can now be distributed instantaneously and almost without cost. The reduction in barriers to entry have fundamentally altered the media industry. Consider the evolution of television. When there was only broadcast TV, the early network entrants, ABC, CBS, and NBC, quickly became an oligopoly because the newly established value of a nationwide set of local TV stations created a prohibitive barrier to entry. When cable technology emerged, however, the barrier to entry fell as affiliate stations were no longer necessary. The technology also created advertising efficiencies and programming for niche markets became economically feasible. The result was the Golf Channel, Fox Cable News, the Home Shopping Network, food channels, and other narrowly focused enterprises.

Anyone with a laptop and an Internet connection can be in the news business.

The Internet is the ultimate equalizer as it demolished the existing barrier to entry for those who would like to be in the news business. Conventional newspapers have not been able to monetize their online presence while news websites without newsrooms have proliferated. Anyone with a laptop and an Internet connection can be in the news business (such as the rise of “citizen journalists”). Quality, of course, is another matter but when it comes to fake news, it is sensationalism and “clickability” that is most critical.

The capital requirements for creating fake news stories are not only infinitesimal—only an imagination is required—but the costs of distribution are negligible as well. The technologically savvy can create bots which propel stories back and forth among fake accounts, scoring hits and likes and pushing these articles to the top of trending news on Facebook and Google. Placed on a website, a story can be linked to an advertising service which generates a few pennies per clickthrough. Solutions are elusive. Fact checking fake news is ineffective—stories multiply faster than legitimate news sites can discredit them. With the unquenchable thirst of the 24 hour news cycle, cable TV and talk radio often cover political accusations as news stories, alleviating themselves of the responsibility to without the need to verify their accuracy. Thus, on his show on Fox Cable Sean Hannity might discuss accusations that were made by Breitbart, which in turn was covering incendiary charges made earlier in the day by radio host and conspiracy theorist Alex Jones. The biggest megaphone of all for fake news belongs to Donald Trump, who can dominate a news cycle even with a story that is immediately refuted, such as his tweet that there was evidence that three million voted illegally.

In our current media environment outrageous content is what attracts audiences and, therefore, advertising. Legal remedies for even the most scurrilous of stories are beyond what’s realistically possible. Distribution often emanates from foreign servers such as those based in Macedonia, home to many fake news sites.

Scholars don’t know what impact fake news had on the 2016 election and we may never really know. News consumers have a strong selection bias as they make choices among conventional media, websites, tweets, and Facebook postings. The density and velocity of fake news is an overwhelming tide that provides stiff competition to mainstream news sources. Unfortunately, in terms of its economic efficiency, fake news makes a lot of sense.

Featured Image Credit: Man using stylus pen by Kaboompics. Public domain via Pexels.

The post The economic efficiency of fake news appeared first on OUPblog.

What ails India’s health sector?

Most discourse on the health sector in India ends with a lament about underfunding and not without reason. India is one of 15 countries in the world that has a public spending record of about 1% of its GDP on health. Such low spending cannot be expected to deliver much. After all, health is expensive. The more sophisticated the technology, the better the chances of survival but also the higher the cost. A PET (positron emission tomography) scan can help with accurate diagnoses and can improve chances of survival but also costs a hundred times more than the familiar X-ray machine. Many Indians can ill afford to bear the cost of drugs, doctors, technicians, or hospitals with beds and operating theatres, and look to the government for help. So discussions around increased public funding in a poor country like India are critical.

But then, money does not buy everything. What is equally important is attention to systems of governance based on trust and empathy. Systems that recognise that when people are sick, they are equally vulnerable, regardless of means, age, or gender. Such a system would foster patient-centered health delivery and a culture of values such as honesty, integrity, and the pursuit of knowledge. As a society, we do not seem to give these issues much importance. But then it hurts when one recalls and reads about the poor tribal Manjhi carrying the dead body of his wife Amang back home on his frail shoulders as he could not afford an ambulance. And again when in the Guntur Medical College ICU, a ten-day-old infant died of rat bites. What is disturbing is that such instances of indifference are rapidly becoming the norm. Such disregard for human life is a strong indictment on us as a people as much as it is on the government.

Clearly, what is needed is a deepening of dialogue and the creation of a discursive environment for policymaking in a conscious and deliberate manner. This implies a deepening of democracy, over and above the symbolic elections. Policies that impact the daily life of the people, such as health, need to be formulated based on the people’s participation. For this to occur, systems have to be built and organisational structures put in place. There is some evidence of such approaches having been adopted in the battle against HIV-AIDS and polio. These community-anchored and people-centered approaches helped design policies that created results faster. Fund utilisation was also more efficient and misuse more difficult. India needs to build on these experiences and construct a democratic architecture where common people and patients have a voice in formulating policy and actively help in its implementation. For ultimately, democracy is as much about parliaments as it is about hearing people’s voices and redressing their problems as a matter of routine—every day, not just once in five years.

Understanding what ails us provides us with the opportunity to go forward.

But then, adequate funding, value-based societal relations, and people-centered governance models can only be possible when there is clarity on the type of future we aspire to. Such clarity is sadly missing. For example, we have a vast private sector that caters to more than half of the people’s health needs but is largely unaccountable to either price or quality. On the other hand, we have a public sector that is overburdened, understaffed, and underfunded. There is no clarity on the implications of such a system to notions of equitable access, improved health or cost. Likewise, we have a situation where the upper tiers of tertiary care are built on the foundations of a rickety primary care system. Primary healthcare, if effectively delivered, can address 90% of people’s health needs. India’s primary healthcare system barely addresses 15%. So more than half of the meagre resources are being spent on tertiary care benefitting 2% of the sick, largely financed through third-party insurance in the private corporate hospitals. What is worrisome is that both the burgeoning private sector and health insurance markets are poorly regulated with little accountability to the patient. Such unplanned and haphazard growth in the sector resembles the US model where healthcare is similarly fragmented, costly, and inefficient. The question is whether India can afford a US model of healthcare and what its implications are for a country that has such a large reservoir of the sick and the poor.

Finally, there is a need for dialogue around what we mean by development. Is it about GDP? Is poverty to be measured only in terms of income thresholds or should it be viewed more multi-dimensionally? The latter view involves thinking of health in its broader sense and placing a charge on the state to provide clean air, water, and sanitation; environmental hygiene; nutrition; and basic healthcare for all its citizens without prejudice.

Policy choices are not made in a vacuum. They are the result of the lobbying power of interests and stakeholders. I believe that to act for the future, we need to understand the past and comprehend the present. In other words, we need to have a comprehensive understanding of our context—our strengths, our weaknesses, our beliefs, and our aspirations. Such holistic perspectives are necessary as all policies and actions flow as a continuum, which is why copy-cat solutions or imitating another country’s experiences most often fail and fall short. We need to understand what ails the health sector and what we need to do. For every problem has its solution embedded within it.

Understanding what ails us provides us with the opportunity to go forward.

Featured image credit: Thermometer, by stevepb. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post What ails India’s health sector? appeared first on OUPblog.

January 16, 2017

What members of congress can learn from nurses

Once again, the American public have rated nurses as the most trusted professionals, as they have for the past 15 years. Members of Congress were at the bottom of the list, as they have been for the past five years. What’s the difference between nurses and members of Congress when it comes to trust? And what can members of Congress learn from this difference?

We trust people when people prove themselves trustworthy. Trustworthy people, the philosopher Onora O’Neil says, are reliable, competent, and honest.

Anyone who has been cared for by a nurse knows that nurses are reliable. They’ll do what they say they’ll do. It may take them a while, but usually this is because they are busy. Research has shown that when nurses are less busy, they deliver even more reliable care.

After years of stubborn refusal to pass laws and perform basic duties, such as to confirm appointed judges, some members of Congress appear unrepentant about their unreliability.

Nurses pass a national certification exam, and they take mandated continuing education courses throughout their career. But nurses truly demonstrate their competence by delivering quality patient care day after day.

Perhaps Congress could institute training for newly elected members on how to govern. The syllabus might include Plato’s Republic or Rousseau’s The Social Contract. Yet many members of Congress come with government or law degrees. These degrees notwithstanding, they could prove their competence by performing their governing duties.

Barack Obama signing the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act at the White House by Pete Souza. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Barack Obama signing the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act at the White House by Pete Souza. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.By and large, we trust that nurses are honest. For example, we trust they do not lie about the medications they are about to give. We often ask for them for verification, but we do so out of fear of human error, not fear that they may have malicious motives. After all, nurses have little reason to be dishonest. They don’t want to harm their patients, and they don’t gain income or promotion by bringing more money into the hospital or clinic through trumping up tests or treatments that aren’t necessary. Nurses gain no reward from their honesty beyond knowing that they’ve done their job well, but their patients do.

Members of Congress are not in office for underhanded reasons; surely they have a sense of public service. But unlike nurses, it seems that members of Congress are not disinterested. Many are rich. In 2015, the median net worth of a member of Congress was $1,029,505, compared to $56,355 for the average American household. And they tend to get richer during their time in public service.

But there’s one more quality – perhaps the most important – that makes nurses trustworthy. Nurses care. In hospitals, clinics, schools, prisons, and homes across America, nurses care for others. Sure, nurses earn a paycheck, but as a nurse, I can tell you that on many a day, the paycheck does not make up for the stress of having another person’s life in my hands. Nor does it soothe my aching feet, sore back, and hands cracked from repeated washing. We nurses care for others because it is the right thing to do. We care for others regardless of who they are. We show we care through our daily acts of nursing for all people who need it.

On the first day of the 115th United States Congress, a majority of the members of the House of Representatives voted to weaken the Office of Congressional Ethics. It makes one wonder for whom these members care. To be sure, there must be many members of Congress who care for all people in their constituencies, not just for those who are likely to re-elect them or those who may help them to enrich themselves. But to improve their position on the “Most Trusted” poll, perhaps members of Congress could follow nurses’ example. Perhaps the American public would trust members of Congress more if, through their repeated acts of governing on behalf of all Americans, they showed us they care.

Featured image credit: Capital by jensjung. CCO Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post What members of congress can learn from nurses appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 237 followers