Oxford University Press's Blog, page 413

January 29, 2017

Ineffable facts, deep ignorance, and the sub-algebra hypothesis: Part 1

There are many things we do not know, but sometimes our ignorance runs deeper than other times. In regular cases of ignorance we can ask a particular question, but we can’t figure out what the answer is. Furthermore, for some such cases we are bound to always remain ignorant, and we know it. Is the number of T. Rex that ever lived odd or even? We will never know, that information is lost in time, but, of course, in this case it won’t matter what the answer is.

However, in other cases our ignorance might go further and there it might matter a lot. Sometimes we might not merely be unable to answer a question, but we might be unable to ask the question in the first place. To illustrate this possibility, it is important to make vivid that every time we come to know something we need to complete two quite separate tasks, each of which is an achievement: one is to be able to represent the world, the other to find out that this representation is accurate. For example, when I come to know that mercury is toxic I first have to be able to represent that mercury is toxic in thought or language and then, second, have good enough reasons to hold that this representation is correct. Normally the second part gets all the attention, since it is holding us back in ordinary cases of ignorance: ones where we can ask the question, but we are unable to answer it. But in some cases a lot of the real work went into being able to ask the question and represent the world in the first place. To be able to represent that the universe is expanding, for example, is a real achievement, besides finding out that it is an accurate representation.

To come to know we thus need to complete two separate tasks — a representational one and a more narrowly epistemic one — and our inability to complete one or the other can be a source of ignorance. We can say that deep ignorance obtains when the source of our ignorance is representational, and regular ignorance when the source is epistemic. We are clearly ignorant of some facts, but are we deeply ignorant of some facts? Are there facts we can’t represent at all, and thus can’t even ask whether they obtain?

Any fact that is beyond what human beings can represent in thought or language we can call an “ineffable fact.” If there are ineffable facts then we are deeply ignorant of them, and thus our ignorance goes deeper than merely being unable to answer a question we can ask. If there are such facts then we clearly can’t give an example of them. We can’t coherently say that the fact that…is ineffable for us. But even though we can’t give examples of facts we are deeply ignorant of, we might still have good reasons to think that there are such facts. I would like to suggest that the answer to this question is rather significant for our conception of ourselves in the world and for what ambitions we can hope to have for coming to an understanding of the world as a whole.

Once we think about it, we should expect that there are ineffable facts. Even though we can’t give examples of facts that are ineffable for us, we can give examples of facts that are ineffable for other creatures, ones that have lesser representational powers. A squirrel can’t represent the fact that there is an economic crisis in Greece, but we can. We do better than the squirrels, but why might other creatures not do even better? Maybe other creatures — gods or aliens — could, and in fact do, look down at us like we look down at the squirrel. And maybe they would say that although humans are pretty good at representing some of the facts, like that there is an economic crisis in Greece, their human minds are much too simple to represent the fact that … (and now only they could complete this sentence). And thus there would be facts ineffable for us, and these other creatures can give examples of them, although we can’t.

But then again, maybe we got lucky, and we can in fact represent all the facts. Maybe we made it to the top of what can in principle be represented, while the squirrel is only halfway there. But that would be lucky, and we shouldn’t expect to have gotten lucky, even though we might have. Our brains are much larger and more complex than the squirrels’, but still much smaller than brains the size of a truck. A creature with super-complex truck-size brains might be able to resent much more about reality than we can. Unless, of course, as luck would have it, our size brains are just good enough to represent everything there is to represent, while the squirrels still fall short. Since we shouldn’t count on having gotten lucky, we should expect that there are ineffable facts, facts hidden from us just as the fact that there is an economic crisis in Greece is hidden from squirrels. But then, how can we hope to come to a proper understanding of all of the world when we need to recognize that our minds likely are too simple to even represent all of the facts? What should we conclude from there being ineffable facts and our being deeply ignorant of them?

In a second part, I will look at one proposal for an answer to these questions.

Featured image: Squirrel on a fence by milito10. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Ineffable facts, deep ignorance, and the sub-algebra hypothesis: Part 1 appeared first on OUPblog.

January 28, 2017

A Q&A with Jessica Green, global academic marketing assistant for humanities

We caught up with Jessica Green, who joined Oxford University Press in October 2016 and is currently a Marketing Assistant for Global Academic, working across Humanities subjects including Literature, Music, and Linguistics. She talks to us about her favourite authors, her role, and OUP journey so far.

When did you start working at OUP?

The end of October 2016 – which already feels like a lifetime ago.

What was your first job in publishing?

This is actually my first job in publishing, post-graduation. I graduated in 2015 and spent some time travelling for a while, and more recently I worked for a small media company based in Birmingham.

What’s the most enjoyable part of your day?

Whenever I’ve completed or made progress on a particular project.

What’s the least enjoyable?

Waking up – I’m not particularly fond of early mornings as it is, but I’m currently commuting from Birmingham so my day starts very early!

What is the strangest thing currently on or in your desk?

An odd print out of a pug dressed up as Princess Leia – I’m really not sure how it ended up there, but I have zero plans to remove it.

What one resource/site would you recommend to someone trying to get into publishing?

I found the Bookseller really useful when applying for roles – it’s super easy to navigate, with advice and tips on breaking into the industry as well as general insight for casual reading.

Jessica Green, used with permission of the author

Jessica Green, used with permission of the authorWhat’s your favourite book?

Ask any bookworm this question and I’m sure they’ll struggle to answer. I don’t have a favourite but I’m a huge fan of Neil Gaiman – I’d read his shopping lists.

If you didn’t work in publishing, what would you be doing?

I would be in an industry where I was utilising my creative writing skills, such as Journalism or Advertising.

What’s the first thing you do when you get to work in the morning?

I head straight to the canteen for my daily dose of porridge.

Open the book you’re currently reading and turn to page 75. Tell us the title of the book, and the third sentence on that page.

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari: “Large animals – the primary victims of the Australian extinction – breed slowly.”

What will you be doing once you’ve completed this Q&A?

I will be completing Google ad training, a practice that I’m soon to integrate into my role. I’ll also be putting together flyers for authors and working towards social media projects for our 2017 titles.

Tell us about one of your proudest moments at work.

I recently created an interactive map of names for The Oxford Dictionary of Family Names in Britain and Ireland, I was quite proud of it given that it took such a large amount of time to code!

If you could trade places with any one person for a week, who would it be and why?

Hilary Clinton – because it would be a very interesting week, undoubtedly.

What is your favourite word?

I usually have a word of the day, depending on how often I say it or the uniqueness of the word itself. But I’m a big fan of slipping archaic words into everyday conversation; I’ll often use “forsooth“, “hence”, and “thus” regularly and I even called somebody a “flibbertigibbet” the other day.

Longest book ever read?

The Lord of the Rings by the great Tolkien, if you consider it as one extended epic novel.

Favorite animal?

Foxes – they’re often labelled as miscreants but I believe that they’re simply misunderstood.

What drew you to work for OUP in the first place? What do you think about that now?

I was attracted to its prestigious reputation and the potential for career progression – which is fantastic for a recent graduate starting out in publishing.

How would you sum your job up in three words?

Eclectic, progressive, satisfying.

Featured image credit: Oxford, Street, England by keem1201. CC0 Public domain via Pixabay.

The post A Q&A with Jessica Green, global academic marketing assistant for humanities appeared first on OUPblog.

Favorite books around the world

Throughout 2016, Oxford University Press has traveled all around the world meeting and talking with librarians to learn about their favorite books.

From a Colombian librarian who prefers a French author, to a French librarian who’s enamored with an American novel, the results from our year-long quest exemplify the universal reach of literature and its ability to connect individuals from various walks of life. Check out the interactive book map below to explore more international favorite titles.

Featured image credit: “Colorful” by fxxu. CC0 Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Favorite books around the world appeared first on OUPblog.

The origins of Trumpism

The rise of Donald J. Trump may seem unprecedented, but we’ve seen this phenomenon before in the person of Robert H.W. Welch Jr., who founded the John Birch Society in 1958.

Like Trump, Welch was a wealthy businessman. As vice president for sales at his brother’s confectionery company—which manufactured Junior Mints, Sugar Babies, and other popular brands—he understood the power of publicity. Selling candy and marketing politics had a lot in common.

Like Trump, Welch was viewed as an unhinged rabble-rouser and a dangerous right-wing extremist. The media were fascinated and alarmed by him because he said such outrageous things: President Dwight Eisenhower was a communist who took his marching orders from his brother, Milton. Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren should be impeached because he supported school desegregation. The United States should withdraw from the United Nations, which existed to undermine US sovereignty. Fluoridation of water supplies was a communist plot.

The Society, which still exists, was named for a missionary-turned-soldier who was shot and killed by Communists in China at the end of World War II. Welch linked the martyrdom of the young John Birch to the subsequent “loss” of China to Mao’s Red Army. The cover-up of Birch’s death was evidence of treason within the Truman administration.

Welch, like Trump, aimed to transform the system. His core ideas hearkened back to a simpler time, before there was a federal income tax and the welfare policies of the New Deal. He advocated free market capitalism, opposed big-government, and attacked the Washington establishment as misguided and corrupt. He mounted a nationwide law-and-order campaign to “support your local police.”

Also like Trump, Welch claimed that conspiratorial forces threatened the United States, undermining its strength and sapping its will. Political elites were “insiders” working against America’s interests. They were either conscious agents or dupes being manipulated by subversive powers. If the government said something, the truth must be the opposite. The failed 1961 US invasion of Cuba was a phony assault to consolidate Castro’s alliance with the Soviets. Support for non-communist forces in South Vietnam actually disguised a plan to assist a communist takeover. In today’s world, Welch would have understood globalization as a sinister scheme, and China and Islam as existential threats.

President Trump’s politics draw on Robert Welch’s playbook.

Welch was maligned by liberals, denounced by conservatives, and dismissed by the mainstream media. Yet tens of thousands of Americans—mostly white, middle-class, suburban and many of them women—became loyal members. They didn’t necessarily agree with everything Robert Welch said, but they believed his basic message was important. They were concerned about the erosion of traditional values; the advance of socialism and communism; the overreach of government; runaway taxes and the national debt. Although Welch was not running for political office, he gave these citizens a voice.

President Trump’s politics draw on Robert Welch’s playbook. Trump has tapped into alienation and anxiety about rapid social change. He uses conspiracy theories and bogus information to provoke and disrupt. His supporters, who harbor a distrust for government and fear of foreign entanglements, are willing to look beyond his inflammatory rhetoric. And like members of the Birch Society, they believe that their individual rights are threatened, the federal government needs to be curtailed, and international agreements cannot be trusted.

The John Birch Society, which marked the beginning of our divided politics in modern times, faded from public view by the late 1960s. But with Trump’s electoral success, what was once considered a fringe movement has moved to the center. Mr. Welch, who died in 1985, would have celebrated Trumpism as the victory of Birchism. Whether the revival of his tactics and ideas will “make America great again” remains to be seen.

Featured image credit: Donald Trump with supporters by Gage Skidmore. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

The post The origins of Trumpism appeared first on OUPblog.

Hookup culture on Catholic college campuses: the norm and the marginalized

Students hook up. They have sexual encounters with no implications for subsequent relationships. Far from being the majority of students however, it is a small minority, somewhere around 20% of students. Moreover, these students share other characteristics: they tend to be white, wealthy, and attend elite schools.

While there is not a problem with these students, their activities foster stereotypical hookup culture that does cause problems. Their behavior becomes a norm, assumed to be what everyone on campus is doing and what everyone should want to do. It becomes the expected way of acting, so everyone has to position themselves in relationship to it, even if it is a rejection of it. Students have to conform or explain their divergence, and divergence almost always comes with some social penalties.

This dynamic is clear in the New York Times story “Sex on Campus – She Can Play That Game, Too.” There, Kate Taylor interviewed college women about hookup culture. Those who participated attended Ivy League schools. These women hook up, aren’t interested in relationships, and are primarily focused on their careers. The people who don’t participate are like Mercedes, who was summarized as saying that “at her mostlyLatino public high school in California, it was the troubled and unmotivated students who drank and hooked up, while the honors students who wanted to go to college kept away from those things.” As a result, she felt like she did not fit in with everyone else who “seemed to live life, not really care about what they were doing.”

For me, this story clearly sets out the dynamics of hookup culture. The women who hooked up were not intentionally excluding someone like Mercedes. Rather, they assumed that their behavior was the norm. This assumption, though, made those like Mercedes who acted differently feel like they did not belong. It pushed them to the social fringe. This is true even though, as the story reported, those who didn’t hook up were more numerous than those who did, from 30% of students to 20%.

…stereotypical hookup culture creates a problem that normalizes the behavior of a few and marginalizes the behavior of everyone else who differs.

Thus, stereotypical hookup culture creates a problem that normalizes the behavior of a few and marginalizes the behavior of everyone else who differs.

One group who is different is Catholic students. Catholic students who go to church regularly, pray frequently, have strong beliefs in agreement with church teaching (especially the ones on sexuality) tend not to hook up. Not only did I find this across the campuses in my research, but others also have found this connection (for example see here, here, here, here, and here).

The result of not hooking up, of not adhering to the “norm”, is marginalization. Catholic students feel like they are on the fringes of social life, committing what Donna Freitas calls “social suicide.” They feel ridiculed and ostracized for their beliefs and so tend to hide their faith or hide themselves among students with similar beliefs. If they don’t hide, students proclaim their beliefs, trying to defend them. Both, however, are different responses to the same problem of being pushed to the fringes of campus life.

LGBTQ students are also marginalized by stereotypical hookup culture. To be sure, their experience is more precarious than that of Catholic students. Worrying about personal safety and fighting for one’s basic human dignity outweighs the feeling that one’s beliefs are not being respected. With this caveat though, LGBTQ students experience similar forces of marginalization that Catholic students do. Those in the LGBTQ community tend not to hook up. This is partly because LGBTQ students are unsure that they would be welcomed in those environments where hooking up occurs or that their participation in hooking up would be accepted by others. Thus, they often find themselves pushed to the fringes of campus social life by the assumption that stereotypical hookup culture is the norm. Like Catholic students but with higher stakes, LGBTQ students have either hidden themselves from the broader culture or sought to advocate for their inclusion. The latter has resulted in numerous initiatives and changes on campuses.

How does one undo the marginalization that occurs from stereotypical hookup culture? Scapegoating those who participate in stereotypical hookup culture isn’t particularly helpful. Just changing who is marginalized doesn’t make things better.

Simple tolerance isn’t helpful either. Some activities should not be allowed, like sexual harassment, coercion, or assault. These are not sexual activities but violence done by using sex as a weapon. Respecting others and honoring their human dignity should apply to everyone, with special attention to the marginalized who too often struggle for these basic recognitions.

I do think that student awareness that stereotypical hookup culture is the preference of only a small minority of students, about 20%, can help. Hooking up is not the preference of about 80% of students, including those who are not in the upper economic classes, those who are racial minorities, those who are highly religiously committed, and those who are part of the LGBTQ community.

This awareness can help to undermine the dominance of stereotypical hookup culture as the norm and, in doing so, weaken its marginalization of the vast majority of students. If students do want to hook up, they should be left to do so. If students do not want to hook up, they should not be penalized for doing so. These differences should be acknowledged as strong and viable social possibilities. If this is done, if the social penalties for being different are removed, most students will move from being marginalized to being able to pursue happier, healthier relationships.

Featured image credit: Caldwell Hall at The Catholic University of America by Farragutful. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Hookup culture on Catholic college campuses: the norm and the marginalized appeared first on OUPblog.

January 27, 2017

The Amazons ride again

The Amazons of Greek legend have fascinated humans for the past 3,000 years. The Amazon women were faster, smarter, and better than men, or so claimed the Greek author Lysias:

[The Amazons] alone of those dwelling around them were armed with iron, they were the first to ride horses, and, on account of the inexperience of their enemies, they overtook by capture those who fled, or left behind those who pursued. They were esteemed more as men on account of their courage than as women on account of their nature. They were thought to excel men more in spirit than they were thought to be inferior due to their bodies.

In fact, they were so capable that they managed to live without men at all, procreating by meeting up with a neighboring tribe only once in a while, or, in an even more titillating version of the story, by crippling men and keeping them as sex slaves.

But is there any truth behind these legends? During the latter half of the 20th century, while Western classicists argued that the Amazons were figments of the Greek imagination, Soviet archaeologists were busy unearthing graves of women buried with weapons. While literary theorists argued that the Amazons were simply an imagined “other” against which the Greeks defined themselves, archaeologists dug up evidence of what they called “Amazons” among Scythians, Sauromatians, and Thracians, all peoples whom the ancient Greeks associated with the Amazons.

Furthermore, Greek authors tell us that the Amazons did similar things as the Scythians, Sauromatians, and Thracians, all peoples for whom there is more historical evidence than for the Amazons themselves. Just as Lysias tells us the Amazons were the first to harness the use of iron to make weapons, so the Greek author Hellanicus tells us it was the Scythians who first made iron weapons. The discovery of iron weapons dating to circa 2500 BCE in the Ukraine, the region that would later be called Scythia by the Greeks, suggests that there just might be something to these tales. The Greek author Hellanicus tells us that the word Amazon means “breastless” (a=without, mazon=breast), because the Amazons removed one of their breasts in order that they could draw back a bowstring more easily. The Greek physician Hippocrates, on the other hand, suggests that it was Sauromatian women who cauterized one of their breasts. The Greek historian Herodotus, often called the “father of history” tells us that the Amazon women married Scythian men to form the Sauromatian tribe.

Statue of fighting Amazon outside Altes Museum Berlin. Photo by Christian Benseler. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Statue of fighting Amazon outside Altes Museum Berlin. Photo by Christian Benseler. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Yet the Amazons were associated by Greek authors with other historical peoples as well, namely the Thracians and Libyans. In the earliest Greek literature, the epic poet Arctinus asserted that the Amazon queen Penthesilea, who came to fight the Greeks during the fabled Trojan War, was “Thracian by birth.” In later Greek literature, Diodorus Siculus exclaimed that the Amazons originated in Libya, whereas Herodotus told us that the young girls of the Libyan tribe of the Auseans were taught to fight with staves and stones. As one digs through the evidence, both literally (archaeologically speaking) and figuratively (in Greek literature), it begins to sound more and more as though the Greek idea of the Amazon was based upon some historical reality of women who fought.

While some of the stories of the Amazons may have been, admittedly, exaggerations, the Amazons were a Greek reflection of more historical peoples. How else might we explain that they turned up in Greek literature in all the same places where nomadic women fought? On the steppes of Afroeurasia, women had need to defend themselves from enemies and other predators. There were no walls to protect them. But because the Greeks did not fully understand such a nomadic way of life, they saw women warriors on horseback as “masculine.” Hence they called them breastless, or “Amazons.” Comparison to Sanskrit literature is of interest here, as the ancient Indians also called women whom they perceived to be masculine “breastless.” Sanskrit literature furthermore suggests that the nomadic women of Central Asia, whom the Greeks labelled Amazons, were imported into India to become women bodyguards. Fabled for their fierceness, the nomadic women of central Asia made excellent bodyguards in the harems of South Asian palaces, where no man, not even a eunuch, might enter.

So, to return to the question at hand, were the Amazons of antiquity historical? It certainly seems that they were based upon a Greek understanding of historical nomadic peoples, even if the term Amazon itself was a Greek epithet. And while Classicists may be correct, at least in part, to understand the “Amazon” as an “other” against which the Greeks defined their own ethnicity, narratives of Amazons that parallel those of Scythians, Sauromatians, Thracians, and Libyans suggest that the “other” was not entirely a construction of the Greek imagination. It was based upon a historical reality that we are only now just beginning to understand.

Featured image credit: Ancient Roman sarcophagi in the Museo Ostiense (Ostia Antica) by Sailko. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The Amazons ride again appeared first on OUPblog.

What is the role of the Environmental Protection Agency?

During his first official week as the president of the United States, Donald Trump is moving quickly on his to-do list for his first 100 days in office, proving that he plans on sticking to the promises that he made as a candidate. Earlier this week, the Trump administration ordered a media blackout at the Environmental Protection Agency and has instructed staff to temporarily suspend all new contracts and grant awards.

In the following excerpt from Environmental Protection: What Everyone Needs to Know®, author Pamela Hill describes what exactly the Environmental Protection Agency is, as well as what role the agency plays in the United States.

What is the Environmental Protection Agency?

The US Environmental Protection Agency (the EPA) is the main government agency charged with administering the federal environmental laws in the United States. The EPA’s job boils down to the difficult task of converting the broad mandates in laws passed by Congress into regulations and programs that can be understood by the public and by those who need to follow them, mostly industries. In addition, the EPA distributes large sums of money to states and other entities for specific purposes described in the environmental laws, such as money to run state environmental programs or to build sewage treatment plants. These funds make possible much of the environmental protection that the EPA oversees and the United States enjoys.

President Nixon created the EPA by an executive order, bringing together pieces of federal departments that previously had elements of environmental protection responsibility among their larger mandates. It is an independent regulatory agency and part of the executive branch of government. The president appoints its administrator with Senate approval. The EPA has a headquarters in Washington, DC in charge of policy and regulatory development, more than a dozen labs, and ten regional offices responsible for enforcement and for working with the states on program implementation. The EPA employs about 17,000 people, including scientists, engineers, policy analysts, lawyers, and economists.

The EPA’s independent status, notwithstanding its connection to the executive branch, is intended to protect its objectivity and the scientific basis of its programs and policies; both are highly valued within the agency. However, the agency is often buffeted by politics. An extreme example occurred during the Ronald Reagan administration when career staff clashed repeatedly with high- level political appointees. Similarly, during the George W. Bush administration the views of policymakers in the White House and political appointees within the agency especially concerning climate change created serious problems for some career staff.

Do most countries have environmental agencies similar to the EPA?

Yes. For example, China’s Ministry of Environmental Protection performs functions similar to the EPA and has collaborated with the EPA for over three decades, as have many other governments’ environmental agencies. The Umweltbundesamt has been Germany’s main environmental protection agency since 1974. The Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment of the Russian Federation is Russia’s EPA equivalent. Although many countries have high- level governmental agencies whose missions broadly concern environmental protection, they vary in focus, structure, and efficacy.

Yosemite National Park by faaike. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

Yosemite National Park by faaike. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.What values drive environmental policy?

Environmental protection has been embedded as a value in our global social fabric at least since the 1970s. The question becomes, then, what values to apply when solving specific environmental issues. Consider this oversimplified scenario: a proposed railway line would run through a wetland on its way from one major city to another, reducing the number of cars and pollution on the road and getting passengers to and from the cities much faster. Should the railway line be approved? Those who take a human- centered (anthropocentric) view value the human benefits from the railway line and would say yes. Those who value the nonhuman benefits of the wetland (such as wildlife habitat) and want to protect it would say no (unless saving it helps humans, as well it might). This is a fundamental values divide in environmental policymaking: human interests versus broader ecological interests. It raises the moral question of whether the human species can do whatever it wants to the environment to advance its own interests, or whether it is only one among many living things and has no right to destroy parts of the planet and deplete its resources for its own benefit at the expense of other species— whether, in fact, it has an obligation to protect these other living things.

At least in western moral philosophy, the human- centered perspective tends to win out: Aristotle himself said that “nature has made all … things for the sake of humans.” The divine command to the first humans in the Bible is to “fill the earth, and subdue it; and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds in the air, and over every living thing that moves upon the earth” (Gen. 1:28). Moreover, the dominance of the economic lens in deciding environmental issues tends to promote human- centered environmental values. But there is significant counterbalance. Some biblical scholars, for example, point to stewardship concepts in the Bible. Many indigenous peoples such as American Indian tribes manifest a strong and abiding spiritual attachment to and respect for nature. The ecological values of the nineteenth century American transcendentalists Emerson and Thoreau linked nature directly with divinity, and are still influential, as is the environmental ethic of thinkers like Carson and Aldo Leopold, famous for his land ethic. In 2015, in his encyclical Laudato Si’, Pope Francis reiterated remarks of his immediate predecessors and other Christian leaders that degradation of the environment is a sin. The relationship between human- centered interests and ecological ones finds its way into jurisprudence. Mineral King Valley in 1969 was a beautiful area and game refuge in the Sierra Nevada Mountains when The Disney Company proposed to build a resort there. Environmental groups tried to block it using a now famous legal argument: trees and other living creatures threatened with harm should have standing to sue in court, much like an orphaned child, with lawyers representing their interests. The legal theory did not win the day, but it received much attention in the US Supreme Court where the case ended up. The notion that “trees have standing” appeared in the dissent penned by Justice William O. Douglas and joined by Justices Brennan and Blackmun, and remains a provocative reminder of the fragility of a natural environment that has no voice, as well as of the stark conflict between economic and ecological values.

Featured image credit: “Earth, Globe, Birth” by geralt. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post What is the role of the Environmental Protection Agency? appeared first on OUPblog.

The music and traditions of Candlemas

Many of us argue about whether Twelfth Night is the evening of 5 or 6 January, anxious that it is considered unlucky to leave Christmas decorations hanging after this. In fact, a more ancient feast of the Church counts the forty days after Christmas as the whole season of Christmastide, ending with the celebration of Candlemas.

Candlemas is generally observed on 2 February (although the Armenian Apostolic Church celebrates Christmas Day on 6 January and Candlemas on 14 February) and it is said that the Queen requests that the tree and decorations remain on display in Sandringham House until the royal party leave, during the week of Candlemas. Think how much brighter those dark days of January must be with the twinkle of Christmas decorations still in place!

Christians celebrate Candlemas to commemorate the Purification of Mary and the Presentation of Christ in the Temple. Under Jewish law, a woman who had given birth to a son was considered unclean for seven days, and was to remain a further thirty-three days “in the blood of her purification.”

According to the law, children belonged to God, and the parents had to “buy them back” on the fortieth day after their birth. So the Presentation in the Temple followed the rite of Purification, which is encapsulated in the famous When to the temple Mary went by Johannes Eccard (found in both Epiphany to All Saints for Choirs and Three Festal Songs) The words of this anthem (arranged for SATB with divisions) summarize the entire Feast of the Purification and Presentation of Christ:

When to the temple Mary went,

And brought the Holy Child,

Him did the aged Simeon see,

As it had been revealed.

He took up Jesus in his arms

And blessing God he said:

In peace I now depart, my Saviour having seen,

The Hope of Israel, the Light of men.

Help now thy servants, gracious Lord,

That we may ever be

As once the faithful Simeon was,

Rejoicing but in Thee;

And when we must from earth departure take,

May gently fall asleep and with Thee wake.

Simeon is a key figure in the Biblical account of the Presentation in the Temple. Having met the baby Jesus at the temple, and taking him into his arms, he uttered a prayer that is still used liturgically as the Latin Nunc dimittis or Song of Simeon, which has been set to music by many notable composers, including Rachmaninoff in the fifth movement of his All-Night Vigil. An evocative and stirring arrangement of this by Katie Melua and Bob Chilcott, provides a more contemporary option with guitar accompaniment and an alto solo.

Image credit: Candlemas Procession. Image copyright The Parish of All Saints, Dorchester, Massachusetts. Used with permission.

Image credit: Candlemas Procession. Image copyright The Parish of All Saints, Dorchester, Massachusetts. Used with permission.Another setting of the Nunc dimittis is John Rutter’s elegant “Depart in Peace” which is scored for the traditional forces of SATB choir and organ accompaniment. Rutter wrote the setting in the style of the composer Sir Charles Villiers Stanford to whom the piece pays homage; Stanford’s own Magnificat and Nunc dimittis settings are firmly established works within the English sacred choral repertoire.

Settings of Senex puerum portabat (An ancient held up an infant) are also popular choices for Candlemas services. Those by Victoria, Palestrina, and William Byrd (in both four and five parts) and more recently, Nico Muhly, who set these words for SATB and brass ensemble, are all ideal selections.

The theme of light is central to Candlemas. Christians believe that Jesus, the “Light of the World”, came at Christmas, and the celebration of Candlemas presents Jesus as “a light to lighten the Gentiles.” Lighted candles are carried at key points in the liturgy, and the church’s beeswax candles to be used for the coming year are blessed during the service. Anthems such as Malcolm Archer’s Eternal Light, shine into our hearts, or Thomas Tallis’s O nata Lux di Lumine (Oh Light, born of Light), that both draw upon the theme of light, are particularly appropriate for a Candlemas service.

It is also natural for the music chosen for Candlemas services to draw upon the imagery of winter departing, and spring emerging. This is captured in Robert Herrick’s poem “Down with the rosemary and bays“, which was arranged for SATB voices by Edgar Pittman in his “Candlemas Eve Carol”, adapted from a Basque melody.

Candlemas also marks the transition from Christmas to the forthcoming season of Lent and Passiontide, and is the time when the church switches the “Anthem of the Blessed Virgin” from Alma Redemptoris Mater (Loving Mother of our Saviour) to Ave Regina Caelorum (Hail, O Queen of Heaven).

The latter will be sung between Candlemas and Maundy Thursday, and choral settings of this anthem, such as those by Gabriel Jackson (which includes a part for electric guitar), Cecilia McDowall, and Samuel Wesley, would also be appropriate additions to the musical choices for a Candlemas service.

Featured image credit: Candles by Gerd Altmann – CCO Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post The music and traditions of Candlemas appeared first on OUPblog.

Shakespearean tragedy and modern politics

On his recent visit to England Barack Obama chose to tour Shakespeare’s Globe, on Bankside; and in the last days of his Presidency, when interviewed about his reading habits, he spoke touchingly and revealingly of his admiration for Shakespeare’s tragedies, and of what they had taught him. ‘I took this wonderful Shakespeare class in college’, he said, ‘where I just started to read the tragedies and dig into them. And that, I think, is foundational for me in understanding how certain patterns repeat themselves and play themselves out between human beings.’ Like Obama, another American President, Abraham Lincoln, greatly admired Shakespeare’s tragedies, especially Macbeth, ironically since he himself, like Duncan in that play, was to be the victim of an assassin.

Other world leaders, too, have studied and found inspiration in these plays. Winston Churchill contributed a short story to a long-forgotten volume of 1934 called Six Stories from Shakespeare in which he chose to write about Julius Caesar. He displayed a politician’s shrewdness in narrating Brutus’s reasons for the assassination of Caesar, writing ‘Caesar must not even be allowed the chance of going wrong, the seed of potential tyranny must be killed outright, like a serpent in the egg. One could hear the sigh of relief and release with which he finally persuaded himself to acquiesce in this sophistry.’ A Great orator himself, Churchill stands aside from the story of the play to comment on its rhetoric: ‘it can scarcely be necessary to remind the reader of what [Antony] said, for no speech in the history of the world is more famous, none better known. “Friends, Romans, countrymen …” ….the words are alive on every tongue, and custom cannot stale them.’ Those last words show Churchill’s knowledge of another tragedy by Shakespeare: they echo Enobarbus’s description of Cleopatra in Antony and Cleopatra.

Nelson Mandela, like Churchill, appears to have had a special affinity with Julius Caesar. In the famous copy of the complete works of Shakespeare disguised as a Bible that was smuggled into the gaol on Robben Island where he spent part of his long period of imprisonment, he singled out a passage from this play: ‘Cowards die many times before their deaths. / The valiant never taste of death but once.’

For all this, few, if any, of the central characters of Shakespeare’s tragedies are fit to stand as role models for national leaders. In the plays based on English history, Henry VI is a wimp and Richard II a vain, self-centred narcissist who achieves grandeur only in defeat. Richard III is a tyrant who murders his way to the throne.

Shakespeare’s tragedies go on resonating with the times, foreshadowing the shape of things to come with a prescience that can seem uncanny.

Stephen Greenblatt, in a brilliant article published in the New York Times headed ‘Shakespeare Explains the 2016 Election’, has recently compared him to Donald Trump. Only the Earl of Richmond, who becomes Henry VII at the end of Richard III, shows promise as a leader. It is to the non-tragic English history plays that we have to look if we seek a central character who is a natural leader of men, and we may find him in Henry V, a charismatic warrior who is also, like Mark Antony, a master of rhetoric.

In the plays normally classed as tragedies, Othello’s distinction as a leader lies mainly in his past, before the action of the play starts. And King Lear is a spent force long before the play’s opening, in which he gives away his kingdom. Coriolanus is a great warrior, a natural leader of men, but a disaster as a politician, despising the common people and failing in his dealings with them so badly that they banish him. And in Antony and Cleopatra the Mark Antony who in Julius Caesar had succeeded so brilliantly in swaying the citizens of Rome against the conspirators is characterized as having become ‘the bellows and the fan / To cool a gipsy’s lust.’ In this play the successful politician is the coldly unlikable Octavius Caesar, as cold and unlikable here as in the earlier play.

In performance, Shakespeare’s tragedies have often been used for political ends. As early as 1681 Coriolanus was adapted, by Nahum Tate, as The Ingratitude of a Commonwealth to reflect on the ‘Popish Plot’ against King Charles II. A production of the same play at the Comédie Française in 1932 provoked right-wing demonstrations in Paris, and in 1973 John Osborne published A Place Calling Itself Rome, a ‘reworking’ of the play which adopts an emphatically right-wing attitude. In 1937 Orson Welles directed a strongly anti-Fascist Julius Caesar in New York, and Gregory Doran’s 2012 production of the same play with an all-black cast suggested comparisons with tyrannical African regimes of our time.

As Mr Obama suggested, Shakespeare’s tragedies go on resonating with the times, foreshadowing the shape of things to come with a prescience that can seem uncanny.

Featured image credit: Shakespeare King Lear ancient by MikeBird. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Shakespearean tragedy and modern politics appeared first on OUPblog.

January 26, 2017

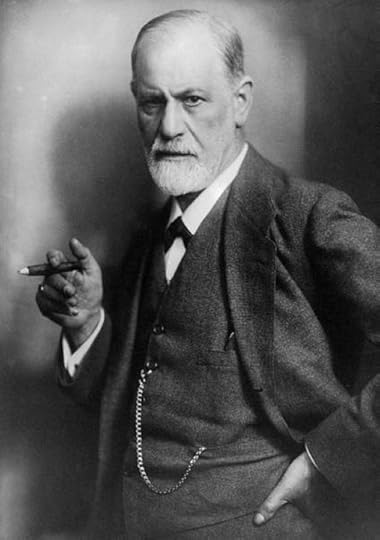

Winnicott’s banquet of 1966

As psychological practitioners and scholars from around the globe prepare to celebrate the launch of The Collected Works of D.W. Winnicott, it might be of interest to know that, almost exactly fifty years ago, the great English psychoanalyst played a substantial role in anointing the publication of the complete works of his hero, none other than Sigmund Freud.

Although Winnicott wrote extensively, producing enough books and chapters and essays to fill twelve volumes, Great Britain’s most accomplished psychoanalyst would never have described himself as a Freud scholar. As Winnicott’s biographer, I can attest to the fact that he read Freud in rather a cursory manner. Some years ago, I purchased quite a number of Winnicott’s personal copies of books by Freud, with the former’s unmistakable signature on the flyleaf, and I can confirm that many of these well-preserved tomes still have copious numbers of uncut pages.

But in spite of the fact that Winnicott read very little Freud, he actually loved the man profoundly.

Winnicott held the distinction of having undergone personal psychoanalysis from not one, but two, of Freud’s disciples, firstly, James Strachey, the younger brother of the littérateur Lytton Strachey, and secondly, Joan Riviere, the wife of a barrister, who had joined the psychoanalytical movement after having suffered from considerable psychological struggles of her own. So, in the course of Winnicott’s extensive period in personal analysis, he learned a very great deal about Freud from his two analysts, both of whom became leading translators of the maestro’s German prose.

Winnicott’s admiration for Freud developed apace. When Freud emigrated to London in 1938 to escape the Nazi menace, Winnicott paid an unexpected visit to Freud’s home in order to inquire about the well-being of the Viennese refugees and to offer help and support – a gesture deeply appreciated by the family.

Throughout his working life, Winnicott remained a devoted Freudian.

Throughout his working life, Winnicott remained a devoted Freudian. When James Strachey, the more beloved of Winnicott’s two analysts, needed access to the library at the Royal Society of Medicine in order to assist his translation work, he turned to Winnicott, his former patient and, also, a physician, for a letter of introduction. Thus, in a small and quiet way, Winnicott helped Strachey quite practically with the preparation of what became The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud in 24 volumes.

James Strachey had begun translating the works of Freud from German into English during the early 1920s, and he continued to do so throughout his working life. In fact, having spent more than 45 years as Freud’s translator, Strachey eventually suffered retinal detachment in the process.

Thus, when in 1966, the work on the Standard Edition neared completion, Winnicott, then President of the British Psycho-Analytical Society, arranged for a lavish banquet to be held in the Connaught Rooms on Great Queen Street, in Central London, not far from the theatre district, to pay homage to the unparalleled contributions of Freud and to the heroic labours of Strachey. Clare Winnicott, second wife to the great psychoanalyst, helped to organise the banquet along with Winnicott’s private secretary of long-standing, the intensely loyal Joyce Coles.

After much planning, some 377 guests, festooned in evening dress, gathered on Saturday, 8th October 1966, to enjoy a delicious meal and to celebrate the publication of the first fully comprehensive edition of Freud’s corpus in English.

Sigmund Freud by skeeze. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

Sigmund Freud by skeeze. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.Winnicott chaired the festivities smoothly and began by reading out congratulatory telegrams from those dignitaries who could not attend. Thereafter, Dr. Piet van der Leeuw, President of the International Psycho-Analytical Association, spoke, praising the “artistry” of Strachey’s translations.

Subsequently, James Strachey delivered his own speech, apologising for his fraudulence in not yet having completed either Volume I or Volume XXIV, which would come to bookend the compendious publication project, sponsored by the Hogarth Press. Next, the sartorially unprepossessing – though clinically brilliant – Anna Freud, dressed in peasant sandals, offered her warm appreciation to all who contributed to the publications of her father’s collected works.

Before the evening concluded, the 85-year-old Leonard Woolf, doyen of the Hogarth Press and widower of Virginia Woolf, reminisced about how he and his late wife had devoted a lifetime to the publication of English-language editions of Freud. Writing about this memorable banquet years later, Woolf confessed that, “I do not find psycho-analysts in private life – much as I have liked many of them – altogether easy to get on with”, and that he experienced the speech-making at the Connaught Rooms as rather “intimidating”.

With characteristic graciousness and generosity, Winnicott concluded the formal proceedings by singling out some special guests, including Freud’s youngest son, the architect Ernst Freud. Winnicott, then 70 of age, must have experienced considerable satisfaction in hosting an evening to mark the publication of 24 landmark volumes, still in use today, more than half a century later.

A consummate Freudophile, Donald Winnicott spent the remaining years of his life working most successfully to commemorate Freud in a more concrete form. Not long after the banquet, Winnicott launched an international campaign, eager to accumulate sufficient funds so that the Oscar Nemon’s life-size plaster statue of Freud, sculpted years previously, could be preserved in bronze. With considerable charm, Winnicott succeeded in raising a great deal of money from psychoanalytical colleagues from such faraway countries as Finland, Portugal, India, Australia, and Brazil.

Happily, on 2nd October 1970, Donald Winnicott presided over the unveiling of this marvelous bronze statue in Swiss Cottage, North London, not far from Sigmund Freud’s final home in nearby Maresfield Gardens.

Winnicott died some three-and-a-half months later, felled by his multi-decade cardiological vulnerabilities. But he departed this world knowing that he had undertaken heroic acts of commemoration of Sigmund Freud in both bibliographic and artistic form. And one can only imagine that it would delight him beyond all measure that, half a century after Winnicott launched the collected works of Freud, the editors and publisher of The Collected Works of D.W. Winnicott have now offered him a comparable posthumous prize.

Featured image credit: D. W. Winnicott for The Collected Works of D. W. Winnicott. Reproduced with permission.

The post Winnicott’s banquet of 1966 appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers