Oxford University Press's Blog, page 411

February 3, 2017

Brexit and muddled thinking

When Sir Ivan Rogers stepped down in January as the UK’s top official in Brussels, he urged his colleagues to ‘continue to challenge ill-founded arguments and muddled thinking’ and not to be afraid ‘to speak the truth to those in power.’ The implication was clear. The government’s Brexit preparations displayed all these failings but the politicians responsible did not like having this pointed out.

We did not have to wait long for evidence of muddled thinking. It came in the form of Prime Minister Theresa May’s speech on the government’s negotiating objectives for exiting the EU. May painted a rosy picture of the post-referendum UK. It was an ‘open and tolerant country’ based on ‘a precious union’ of four nations. Its people had voted to leave the EU ‘with their eyes open.’ Although the referendum campaign had been divisive, the country was now ‘coming together’ and 65m people were willing the government to make Brexit happen.

This is not a picture that many will recognise. The success of the Leave campaign was based on a series of false claims: that withdrawal would enable us to spend an extra £350m a week on the NHS; that EU immigration was having a big effect on domestic wages; that we would be unable to block Turkish accession or a European army. Some Leave campaigners even said that withdrawal would not mean leaving the single market. Many young people were devastated by the loss of opportunities entailed by withdrawal. There was a spike in hate crimes, immigrants were demonised, people heard speaking in foreign languages abused. EU nationals who had made their homes and careers in the UK were plunged into turmoil. ‘Our precious union’ was put at risk because of the increased likelihood of a second referendum on independence in Scotland, which voted to remain.

True, there is something in May’s criticism of the EU for its inflexibility and lack of democratic accountability, although this may sound distinctly odd coming from the Prime Minister of a country with a hereditary monarch and an unelected second chamber, and who has never herself won an election. Moreover, she failed to acknowledge how successfully the UK has operated within the institutions of the EU since 1973. Had successive governments shown leadership, the UK could have been a leading force for reform and helped ensure that the EU is the success May claims she wants it to be. As things stand, it will inevitably be distracted and weakened by Brexit.

The muddled thinking continued when May turned to her negotiating objectives. She didn’t want membership of the single market but did want a free trade agreement with the EU, which might take in elements of the single market. She didn’t want to be in the customs union but did want a customs agreement with the EU, which might mean associate membership of the customs union or signing up to some elements of it. She extolled the virtues of free trade, yet wanted to walk away from the world’s most sophisticated free trade regime. She would not ‘contribute huge sums’ to the EU (exaggerated during the referendum campaign, and outweighed by the economic value of the single market) but was willing to make a financial contribution to specific EU programmes in which the UK took part. She would welcome agreement on continuing collaboration in science and technology and cooperation on law enforcement, intelligence, and foreign and defence policy. Oh, and she would also like phased implementation of the withdrawal agreement to avoid a ‘cliff edge’ for business and individuals.

Had successive governments shown leadership, the UK could have been a leading force for reform and helped ensure that the EU is the success May claims she wants it to be.

May ended her speech with a threat. A punitive deal would be ‘an act of calamitous self-harm’ for the EU27. She was prepared to walk away without a deal – clearly not an act of calamitous self-harm – and ‘change the basis of Britain’s economic model’ to ‘attract the world’s best companies and biggest investors to Britain.’ So as the Foreign Secretary might put it, she wants to have her cake and eat it, and, if she doesn’t get her way, she will take her bat and ball home. How this would help the ‘just about managing’ whom she had earlier pledged to support is unclear. The reaction of Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker to the speech was that the negotiations would be ‘very, very, very difficult.’ HSBC and UBS announced they were preparing to move jobs from the UK to other Member States, while Toyota was considering how to maintain competitiveness in its UK operations.

A week later, the UK Supreme Court gave its eagerly awaited judgment in the ‘Miller’ case. Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union says that ‘Any Member State may decide to withdraw from the Union in accordance with its own constitutional requirements.’ Once the decision has been taken, it is then notified to the EU. The issue in ‘Miller’ was whether the decision to withdraw could be taken by ministers or whether it needed the approval of Parliament. By a majority of 8-3, the Supreme Court held that an Act of Parliament was necessary, but that the content of the Act was a matter for Parliament to decide. The Supreme Court unanimously held that the consent of the devolved legislatures of Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland was not required. So much for ‘our precious union.’

Lawyers may find muddle in the reasoning of the Supreme Court but the result is clear and signals the fundamental importance of Parliamentary democracy and the rule of law. The government introduced a short bill two days later, to be followed by a white paper. These concessions were forced from a government that wished to conduct a secretive process closed to public and Parliamentary scrutiny. Meanwhile, the lead claimant in ‘Miller’ was the subject of prolonged abuse, some of it racially aggravated, and had to hire private security guards. An open and tolerant country? Really?

Featured image credit: westminster palace london by skeeze. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Brexit and muddled thinking appeared first on OUPblog.

February 2, 2017

Social democracy: a prescription for dementia?

In present-day Western Europe and North America, the dementia research field is in as much political turmoil as mainstream politics. And the struggling forces at play in both domains are often the same: individual activity or collective solidarity, technological solutions or community development/public health, for-profits versus nonprofits, unbridled capitalism or regulatory constraint.

So too are the same types of questions often asked: where should we allocate resources? How much should we focus on capitalism, free markets, and science to solve our problems and how much on community investments and infrastructure, and the initiative of nonprofit organizations? To what degree does personal responsibility guide outcomes versus socioeconomic determinants and the flawed (rigged) systems that perpetuate them? In short, both domains seem to reflect a ratcheting up of tensions between neoliberalism and social democracy in our current milieu.

These tensions were recently manifest in US President Barack Obama’s signing of the 21st Century Cures Act passed by the Congress and Senate with bipartisan support. The bill provides $4.8 billion in new funding for the National Institutes of Health, with $1.8 billion earmarked for cancer, $1.6 billion for brain diseases including Alzheimer’s, $500 million for the Food and Drug Administration, and $1 billion to help states deal with opiate abuse. While this sounds like an occasion for celebration, any time a bill mentions the word “cure” we should ask ourselves what is meant by such a promised medical breakthrough and who really benefits?

The easiest health product to sell is false hope and the hardest to implement is real change. As Elizabeth Warren recently pointed out, the Senate passed the bill with good features like strengthening the budget of NIH and finding ways to engage patients and their views in research. But by the time it was finished in the House it had become the dream of lobbyists, loaded up with multiple gifts for many in the private sector. The principle beneficiary was the pharmaceutical and medical device industries where regulatory changes were made to make it easier to get devices and drugs to market. The American Public Health Association also reported that money to find a cure could be taken away from funds for prevention. Cure, of course, is where the profit is—there is much less money to be made from preventing illness.

Image credit: Studying by Mari Helin-Tuominen. CC0 public domain via Unsplash.

Image credit: Studying by Mari Helin-Tuominen. CC0 public domain via Unsplash.And yet, prevention is where data is increasingly telling us our focus ought to be. A recent JAMA article, based on national dementia prevalence data in the United States from 2000-2012, confirmed earlier findings that in some industrialized Western countries, particularly those with high standards of living (e.g. the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Sweden, etc.), the rate of dementia has actually been falling over the last decade. In such population-based studies it is admittedly difficult to determine all the interacting social, behavioral, medical, and other factors that likely contributed to this decline. Even so, the general consensus experts have drawn, both from the recent JAMA study and other such research, is that it is likely that social policy and public health measures that have improved diet, created better educational and exercise opportunities, and contributed to the amelioration of risk factors for cognitive impairment, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or smoking, may be having downstream effects on lowering the dementia rate. Indeed, because researchers found that years of schooling correlated with lower risk in the study, it has also been surmised that post-World War II social democratic policies that widened access to education in Western countries may have played a key role by increasing “cognitive reserve” (i.e. the brain’s capacity to maintain performance in the face of neuropathology) at the population level.

We don’t know for sure whether people born with more robust brains acquire more education or that education itself is protective for dementia. It may ultimately be a combination of both. However, we do know that people who are better-educated are healthier in general, and are less likely to suffer from dementia. Moreover, we know that better educated people are, on average, more economically well off. In sum, the studies demonstrating trends toward lower incidence of dementia in multiple countries would seem to be suggesting that strong social democratic policies supporting socio-economic equality, public and environmental health, and a focus on collective wellbeing best serve the health of the human brain. Overall, the findings stand in pleasant contrast to the usual rhetoric we hear about the “oncoming tidal wave”, or “silver tsunami”, of elderly people with Alzheimer’s.

Image credit: Medicine trials by Nathan Forget. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: Medicine trials by Nathan Forget. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.Indeed, it was quite interesting that just two days after JAMA published the research establishing the drop in dementia rates the pharmaceutical company Lilly announced the failure of their investigational new drug solanezumab in phase III trials of patients with mild Alzheimer’s. This anti-amyloid drug had previously failed with persons with advanced Alzheimer’s, but had shown some small glimmers of hope for subgroups of persons with so-called “Mild Cognitive Impairment.” At the same time Lilly’s drug failed in phase III, the company Biogen was promoting new data suggesting some minimal benefit of their drug aducanumab, another amyloid antibody. As has been a common theme in the wake of consistent amyloid drug failures over the past decade, company spokespersons and others are shifting the goal posts, claiming that these drugs have not been given early enough and sometimes to the wrong population.

Despite this, Paul Aisen, the leader of the Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute at University of Southern California, was quoted as saying that a (formally) negative study of solanezumab actually supports the amyloid hypothesis, because some small beneficial effects were seen. Further, the Alzheimer’s Association’s Heather Snyder was quoted at the same meeting as saying that, despite, continued failures in Alzheimer’s drug development, they are on track for approval of a disease-modifying drug by 2025.

Even if such a prediction were to come true, based on existing drugs in late trials we can wonder what the real magnitude of the benefit to patients and families would be. If a compound was found that “prevented” Alzheimer’s, but had to be administered across many decades, how would we pay for it and who would have access? Would free market dynamics dictate which individuals were able to reduce their risk for dementia? The underlying point is that public health interventions benefit many and expensive drugs (perhaps) very few.

At a time of right-wing/neoliberal drift in many Western countries (as recently represented by Brexit, the election of Donald Trump, and the rise of other far right politicians in countries like France), we mustn’t lose sight of the fact that government investments that broaden access to quality education, increase economic opportunity and reduce poverty, and target known risk factors have complex but critically important downstream benefits for brain health at the population level.

As we face down not only Alzheimer’s disease but also major existential issues like climate change, growing income inequality, and lead in public drinking water, it appears to be imperative for both governments and the dementia field to not merely serve corporate agendas but rather take an active role in creating a fairer, healthier, and more humane society and providing security against the hazards and vicissitudes of life. In the final analysis, a more caring and egalitarian society where we look after one another, invest in shared infrastructure and socioeconomic opportunities, and help people live with dignity and purpose will result in healthier bodies and brains; consequently, social democracy should be seen as a major strategy in the so-called ‘war on Alzheimer’s’.

Featured image credit: Obama by Austen Hufford. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Social democracy: a prescription for dementia? appeared first on OUPblog.

Rise, read, repeat: Groundhog Day at OUP

Bill Murray fought tirelessly to combat the ennui and frustration that accompanied repeating the same day over and over and over again in the film “Groundhog Day.” For him, repetition was torture, but for several of us at Oxford University Press, it’s not so bad…when it comes to reading!

On a day rife with meteorological superstition, we at OUP escape to the sanctuary provided by our favorite books, ones we’ve read again and again and again. Here are a few of our favorites, and why:

* * * * *

“Not only is it beautifully written, The Accidental by Ali Smith made me question everything when I first read it. If I ever feel I’m starting to lose my sense of perspective or purpose, or like my brain needs a spring clean, I dig it out and read it again.”

— Alice Graves, Assistant Marketing Manager

* * * * *

“The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes – my bedside companion, reliably solves any case of insomnia.”

— Clare Bebber, Senior Marketing Manager

* * * * *

“Bizarrely, I think I must have read the The Land of Green Ginger about a hundred times. It’s a satirical re-telling of the Aladdin by Noel Langley and it makes me laugh until I’m sick. Don’t be fooled, it’s the 1937 edition you’re after, not the awful modern re-writes.”

— Katie Stileman, Publicity Assistant

* * * * *

“Andie MacDowell with a groundhog, 2008” by anoldent. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“Andie MacDowell with a groundhog, 2008” by anoldent. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.“Siddhartha by Herman Hesse. At the beginning of the book you take it for granted that you are reading about the Siddhartha Gautama; the Buddha, but as things develop you realise that it’s just a man, and it’s a man who earnestly strives for answers, only to find something resembling an answer as he looks back over the twists and turns and tumult of his own life. Life is the teacher. What to do but start again?”

— Ged Welford, Library Sales Manager

* * * * *

“A Tale of Two Cities is the perfect mix of tragedy, comedy, love, and sacrifice, and is bookended by two of the most famous phrases in English literature. Dickens’ tragic Sydney Carton remains my favorite literary character.”

— Steven Filippi, Marketing Assistant

* * * * *

“The Eyre Affair by Jasper Fforde. It’s fast paced and hilarious, and features cameos from countless literary characters and an awesome heroine to boot. Think Terry Pratchett meets Jane Austen, with a dash of Roald Dahl…don’t ask, just read it!”

— Katharine Eyre, Marketing Manager

* * * * *

“The Time Machine by HG Wells. It was written in 1895, but is still ahead of its time; it predicted world wars and an even worse far-future that may yet come to pass!”

— Colin Pearson, Library Sales Manager

* * * * *

“Groundhog_eating.jpg” by D. Gordon E. Robertson. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“Groundhog_eating.jpg” by D. Gordon E. Robertson. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.“I have probably read I Capture the Castle by Dodie Smith over twenty times since childhood. And just writing this sentence has made me long to get home and escape to that crumbling old castle and eccentric family once again!”

— Rachel Fenwick, Marketing Manager

* * * * *

“Northanger Abbey, far too many times. My favourite re-read has to be when I took it with me to Bath for my 21st birthday, and ended up reading it while visiting the Roman Baths and the Royal Crescent, feeling very Austenian!”

— Emma French, Marketing Assistant

* * * * *

“The Westing Game by Ellen Raskin. Even though I’ve read this book countless times and know the answer to the mystery, the memorable characters keep me coming back to this title.”

— Amanda Hirko, Senior Marketing Manager

* * * * *

“The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams. The total randomness of the universe is hilariously and thoughtfully depicted in the book (and series) and changed my world(s)view the first time I read it in high school. It also taught me the most important lesson in life—Don’t Panic.”

— Molly Hansen, Assistant Marketing Manager

* * * * *

Among other favorites, such as the Harry Potter series and almost every Jane Austen novel, we find these books to be a breath of spring when the winter of our lives seems never-ending. One must only dive into the refreshing yet comforting waters of a story they once knew, and revive themselves.

We wait with anticipation to see if Bill Murray will finally win over Andie MacDowell—I mean, if we must endure six more weeks of winter—but no matter what the fortune-telling mammal decides, we don’t mind. We find comfort in knowing that the best place to weather the winter is the library, a cozy place to spend the day. And the next day. And the next day. And the next day…

Featured image credit: “book-2869-640” by PublicDomainPictures. CC0 Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Rise, read, repeat: Groundhog Day at OUP appeared first on OUPblog.

7 Blasphemous books of the 1920s: James Joyce’s birthday booklist

James Joyce had a thing about birthdays. With some difficulty, he contrived to have Ulysses published on his 40th birthday, and to receive the first copy of Finnegans Wake just in time for his 57th birthday. The day itself was typically crowned by a gala dinner party; at his 50th birthday, he was presented with a big blue cake, decorated as a copy of Ulysses—which moved the author to intone, in the language of the Catholic Mass:

Accipite et manducate ex hoc omnes: Hoc est enim corpus meum.

[Take and eat you all of this, for this is my body.]

That irreverent gesture befits the spirit of Joyce’s novels, suffused as they are with blasphemous appropriations of scripture and sacrament. It speaks also to the work of his fellow modernists, many directly influenced by Joyce, who were often driven by a similar urge to make art from the language and forms of blasphemy.

So however else you may be spending Joyce’s birthday this year—it’s his 135th—consider cozying up with one of the highly irreverent books described below. Drawn from modernism’s heyday in the 1920s, these profiles in profanation all speak to the powerful allure of blasphemy for modernist writers, Joyce foremost among them.

James Joyce, Ulysses (1922):

One contemporary reviewer cautioned readers that Ulysses contained “not only the description but the commission of sin against the Holy Ghost.” That sounds hyperbolic, perhaps, until one reflects that this most canonical of modernist texts begins with a mock-Communion—presided over by Buck Mulligan, the book’s blasphemer-in-chief—then climaxes with a phantasmagoric Black Mass and concludes with the famously profane soliloquy of Molly Bloom, whose flesh and word fulfill the novel’s brazenly Eucharistic ambitions. (“Don’t you think,” Joyce would ask, “there is a certain resemblance between the mystery of the Mass and what I am trying to do?”)

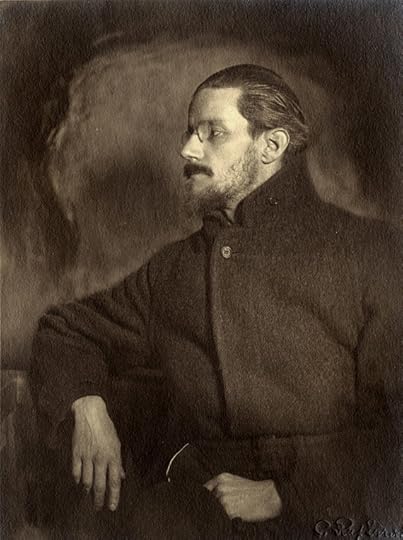

Photo of Revolutionary Joyce Better Contrast by C. Ruf, Zurich, ca. 1918. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Photo of Revolutionary Joyce Better Contrast by C. Ruf, Zurich, ca. 1918. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Mina Loy, Lunar Baedeker (1923):

The third poem in this volume describes Ulysses, with admiration, as “the word made flesh / and feeding upon itself / with erudite fangs.” Loy’s own poetry often achieves much the same effect. On page one of Lunar Baedeker, for instance, a “silver Lucifer” beckons readers to partake of forbidden fruit (“cocaine in cornucopia”) and forbidden bodies (“adolescent thighs”); the book closes with a parodic Nativity that elevates procreation over Creation. But the most indelible image here is the carnal communion imagined in “Love Songs,” where two lovers couple “at the profane communion table,” spilling sacramental wine “on promiscuous lips.”

Ronald Firbank, Concerning the Eccentricities of Cardinal Pirelli (1926):

The madcap opening pages of this novel depict “a christening—and not a child’s.” In fact the object of the priest’s attentions is a week-old police dog who is presently anointed, not with holy water, but with white menthe. (“Sticky stuff,” an onlooker later recalls.) The puppy devotes the rest of this solemn occasion to “incestuous frolics” with its father, while from above them “a choir-boy let fall a little white spit.” “Dear child,” the narrator reflects, “as if that would part them!”

Djuna Barnes, Ladies Almanack (1928):

Barnes is best known for her 1936 novel Nightwood, which culminates in a sacrilegious rite that replaces God with dog. But the earlier Ladies Almanack is a lot more fun. It also features fictional versions of Mina Loy (“Patience Scalpel”) and of Radclyffe Hall, who authored the next item on our list. The book’s real heroine, though, is Saint Evangeline Musset, the larger-than-life prophet of lesbianism; her parables drip with double entendres. “I come,” she proclaims, “to give you Word,” and her lingual facility exceeds the merely rhetorical. After her death, Musset’s tongue is miraculous resurrected, in fiery form, to pleasure each of her disciples one last time: a bawdy reenactment of Acts 2:3, where the Holy Spirit descends on the Apostles in “tongues like as of fire.”

Radclyffe Hall, The Well of Loneliness (1928):

Like Ladies Almanack, this controversial novel combines Christian symbolism with lesbian themes—but to rather more lugubrious effect. The “stigmata” of the homosexual, Hall writes, are “verily the wounds of One nailed to a cross.” Accordingly, protagonist Stephen Gordon believes “that in some queer way she was Jesus”; she yearns to “give light to them that sit in darkness.” British courts suppressed the novel on the grounds of obscenity; meanwhile an anonymously published satire, The Sink of Solitude (1928), not only skewered Hall herself but also called for England’s blasphemy laws to be enforced against Hall’s most vocal critic, James Douglas: the same Sunday Express editor who had earlier railed against the “appalling and revolting blasphemies” of Joyce’s Ulysses.

Georges Bataille, Story of the Eye (1928):

This one isn’t for everybody, but those who make it to the final chapters will find there an orgy in a cathedral, an enucleated eyeball, and a remarkably lewd parody of the Mass.

H. Lawrence, The Escaped Cock (1929):

In this revision of the Christ myth, the recently crucified Jesus wakes in his tomb to overwhelming feelings of regret and resentment. He’s had a raw deal, he now realizes. But he finds his own redemption when he meets an alluring woman who tends to his wounds and, more importantly, initiates him into the mysteries of sexual pleasure. In what may be the most unwittingly comical moments in the canon of modern blasphemy, Lawrence replaces the Resurrection with, in effect, the Erection: “He crouched to her, and he felt the blaze of his manhood and his power rise up in his loins, magnificent. ‘I am risen!'”

Featured image credit: Memorial tablet at the statue of James Joyce in Trieste by Rilegator, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post 7 Blasphemous books of the 1920s: James Joyce’s birthday booklist appeared first on OUPblog.

February 1, 2017

Etymology gleanings for January 2017

One of the queries I received was about the words dimple, dump, dumps, and a few others sounding like them. This is a most confusing group, the main reason being the words’ late attestation (usually Middle and Early Modern English). Where had they been before they came to the surface? Nowhere or just in “oral tradition”? Sometimes an association emerges, but it never goes too far. For instance, not only dumps “depression” has a plural ending. Its synonym doldrums also has it; tantrums often occurs in the plural too. Does this mean that dumps is the plural of dump, with the initial sense “thrown down, being at the bottom”? Such lexicalized plurals are many. Compare color and colors “flag.” Words like digs “living quarters” are also numerous, and animal names like Cuddles and Sniffers (the guinea pigs with which I had the privilege of being acquainted) are known to many of us. Mrs. Skewton’s page (in Dickens’s Dombey and Son) was called Withers. Unlike dumps, the noun dump in the singular, needs no explanation: this is the name of a place where we dump things.

Cuddles or Sniffers, its main virtue is the grammaticalized plural in its name.

Cuddles or Sniffers, its main virtue is the grammaticalized plural in its name.Middle Low [= northern] German dumpeln meant “to dive,” and Modern German Tümpel (also a Low German form, for otherwise it would have begun with pf-) means “pond.” Pond and dive make one think of “deep,” and, beginning with Jacob Grimm (at the latest), it has been customary to compare Engl. dump with deep. To be sure, deep has no m in the middle, but this is not a problem. The old Germanic root of deep was deup-. The vowels in it alternated according to the usual scheme of ablaut: hence Engl. dip (from dupj-) and its German twin taufen, on a different grade of ablaut (taufen now means only “to baptize”). Dump and dumps have the same vowel as dup-, the root of dip. Very many words in the Indo-European languages appear with an intrusive nasal consonant, that is, m or n. From time to time I mention this fact in my essays and always give the same example, because it’s the most transparent one in Modern English: the past of stand is stood. In this verb, the infinitive has a so-called n-infix. Occasionally, our most common borrowings from Latin retain it, but we don’t pay attention: compare convince and conviction. Reconstructing a root with an infix is a trivial procedure. Consequently, deep and dump may be allied (may!). Damp looks like another member of the family, but its belonging with dump has been questioned. We have German Dampf “steam” and Middle High German dimpfen “to give off steam.” Dampness goes well with steam and vapor rather than depths and dumping. Skeat connected damp and dumps through the phrase to damp one’s spirits, but the connection looks weak. Dank may also belongs to this club, but discussing it would take us too far afield.

In the dump group, even easier cases than damp are not without problems. For instance, take dumpling. It is an obvious sum of dump and the diminutive suffix –ling, as in duckling, gosling, changeling, and so forth. But which dump? English dialectal dump “an ill-shaped piece” (applied to various short thick objects) has been attested. It may be related to the verb dump “to throw down with force; throw down in a mass,” but there is no absolute certainty. By contrast, Humpty Dumpty looks transparent, for he was short, even if not “thick”; this jocular word must be a derivative of dump. In such compounds, as a general rule, the determining element is the second, while the first one is meaningless, has no ascertainable origin, and often begins with an h (helter-skelter, hoity-toity, hootchy–kootchy, etc.). Above, we encountered the German word Tümpel “pond.” It matches Engl. dimple almost letter for letter. Both mean “a hollow,” and in the thirteenth century dimple also meant a hollow in the ground. It is the status of damp that keeps bothering me. Its meaning militates against allying it to dump, but from the point of view of ablaut dimple—damp—dump is such an attractive group!

Deedle is a nice onomatopoeia that means nothing. It just alliterates with dumpling, and dumplings are always welcome.

Deedle is a nice onomatopoeia that means nothing. It just alliterates with dumpling, and dumplings are always welcome.If the verb dump had ever meant “to make a hole or hollow,” its origin would have become clear, but such a sense has not been recorded. Perhaps dump is sound-imitative, like plump? The adjective plump was first attested in the fifteenth century with the meaning “dull, blockish.” Its cognates mean “unshapen; obtuse,” and of course the verb plump means “to fall down with a thud.” “Unshapen” and “obtuse” are close enough. Compare blockish ~ blockhead, fathead, and thickhead ~ thick–headed. If dump and plump are somehow connected, the problem is partly solved, but of course we don’t know whether they are. Conversely, dumps and hollow are close. Note that the word depression denotes both a hollow and low sprits.

Dimple and dump may be related, but what a world of difference!

Dimple and dump may be related, but what a world of difference!To repeat: in my opinion, the most problematic word in the entire group is damp. It is sometimes supposed to be allied to Latin fūmus “smoke” (which we know from fume) and even to s-team, assuming that s- in steam is the so-called s-mobile, an evasive sound whose ghost has appeared in this blog more than once. In case dank has anything to do with my story, we have one more candidate whose legitimacy is doubtful but not improbable. I also wonder (a heretical thought) whether all those words have anything to do with deep! Damp ~ dimp- ~ dump– could be onomatopoeic (sound-imitative), though damp does look like an odd man out. An inconclusive story, I admit, but gleaning is hard when the ground is covered with frost and snow, as in the famous children’s poem about two little kittens.

Ablaut

I have a few more interesting questions but will answer them in the next set of gleanings. Today I’ll only touch on the query about ablaut, because it is connected with what has been written above. Ablaut refers to the fact that in Germanic, as in the other Indo-European languages, vowels alternated according to strict rules. In Germanic, there were six series: .1. ei ~ ai ~ i ~ i. 2. eu ~ au ~ u ~ u. 3. e ~ a ~ u ~ u. 4. e ~ a ~ ǣ ~ u. 5. e ~ a ~ ǣ ~ e, and 6. a ~ ō ~ ō ~ a. (in Classes 3, 4, and 5, I did not specify the consonants following the vowels; they have no bearing on my brief note.) Those series were like non-intersecting railway tracks. For instance, i was not allowed to alternate with u, because they belonged to different series. Some vestiges of the old system of ablaut can still be seen in the principal parts of such English verbs as rise ~ rose ~ risen, find ~ found, speak ~ spoke, get ~ got, and others like them (grammars call such verbs strong) and elsewehre. In all handbooks, the alternating series of vowels are given in the order presented above, from 1 to 6. The question was from a correspondent who knew that the scheme had been offered by Jacob Grimm (few non-specialists are aware of this fact), but he wondered why it was established in this order. I do not know. The numbering was, I assume, arbitrary, but perhaps the reason was this: The first and the second “class” have diphthongs in the first two parts (ei ~ ai and eu ~ au), so Jacob Grimm perhaps thought that it would be logical to begin with them. I have no materials to confirm my guess, but I don’t think he explained his coinages and orderings anywhere.

Featured image credit: IMG_7369-1500 by Bengt Nyman. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Images: (1) “Guinea pig” by vantagepointfl. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay. (2) “Soup dumpling” by Andrew Mager. CCo CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr. (3) “Woman, smile” by bearinthenorth. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Etymology gleanings for January 2017 appeared first on OUPblog.

Humpty Dumpty and his kin

One of the queries I received was about the words dimple, dump, dumps, and a few others sounding like them. This is a most confusing group, the main reason being the words’ late attestation (usually Middle and Early Modern English). Where had they been before they came to the surface? Nowhere or just in “oral tradition”? Sometimes an association emerges, but it never goes too far. For instance, not only dumps “depression” has a plural ending. Its synonym doldrums also has it; tantrums often occurs in the plural too. Does this mean that dumps is the plural of dump, with the initial sense “thrown down, being at the bottom”? Such lexicalized plurals are many. Compare color and colors “flag.” Words like digs “living quarters” are also numerous, and animal names like Cuddles and Sniffers (the guinea pigs with which I had the privilege of being acquainted) are known to many of us. Mrs. Skewton’s page (in Dickens’s Dombey and Son) was called Withers. Unlike dumps, the noun dump in the singular, needs no explanation: this is the name of a place where we dump things.

Cuddles or Sniffers, its main virtue is the grammaticalized plural in its name.

Cuddles or Sniffers, its main virtue is the grammaticalized plural in its name.Middle Low [= northern] German dumpeln meant “to dive,” and Modern German Tümpel (also a Low German form, for otherwise it would have begun with pf-) means “pond.” Pond and dive make one think of “deep,” and, beginning with Jacob Grimm (at the latest), it has been customary to compare Engl. dump with deep. To be sure, deep has no m in the middle, but this is not a problem. The old Germanic root of deep was deup-. The vowels in it alternated according to the usual scheme of ablaut: hence Engl. dip (from dupj-) and its German twin taufen, on a different grade of ablaut (taufen now means only “to baptize”). Dump and dumps have the same vowel as dup-, the root of dip. Very many words in the Indo-European languages appear with an intrusive nasal consonant, that is, m or n. From time to time I mention this fact in my essays and always give the same example, because it’s the most transparent one in Modern English: the past of stand is stood. In this verb, the infinitive has a so-called n-infix. Occasionally, our most common borrowings from Latin retain it, but we don’t pay attention: compare convince and conviction. Reconstructing a root with an infix is a trivial procedure. Consequently, deep and dump may be allied (may!). Damp looks like another member of the family, but its belonging with dump has been questioned. We have German Dampf “steam” and Middle High German dimpfen “to give off steam.” Dampness goes well with steam and vapor rather than depths and dumping. Skeat connected damp and dumps through the phrase to damp one’s spirits, but the connection looks weak. Dank may also belongs to this club, but discussing it would take us too far afield.

In the dump group, even easier cases than damp are not without problems. For instance, take dumpling. It is an obvious sum of dump and the diminutive suffix –ling, as in duckling, gosling, changeling, and so forth. But which dump? English dialectal dump “an ill-shaped piece” (applied to various short thick objects) has been attested. It may be related to the verb dump “to throw down with force; throw down in a mass,” but there is no absolute certainty. By contrast, Humpty Dumpty looks transparent, for he was short, even if not “thick”; this jocular word must be a derivative of dump. In such compounds, as a general rule, the determining element is the second, while the first one is meaningless, has no ascertainable origin, and often begins with an h (helter-skelter, hoity-toity, hootchy–kootchy, etc.). Above, we encountered the German word Tümpel “pond.” It matches Engl. dimple almost letter for letter. Both mean “a hollow,” and in the thirteenth century dimple also meant a hollow in the ground. It is the status of damp that keeps bothering me. Its meaning militates against allying it to dump, but from the point of view of ablaut dimple—damp—dump is such an attractive group!

Deedle is a nice onomatopoeia that means nothing. It just alliterates with dumpling, and dumplings are always welcome.

Deedle is a nice onomatopoeia that means nothing. It just alliterates with dumpling, and dumplings are always welcome.If the verb dump had ever meant “to make a hole or hollow,” its origin would have become clear, but such a sense has not been recorded. Perhaps dump is sound-imitative, like plump? The adjective plump was first attested in the fifteenth century with the meaning “dull, blockish.” Its cognates mean “unshapen; obtuse,” and of course the verb plump means “to fall down with a thud.” “Unshapen” and “obtuse” are close enough. Compare blockish ~ blockhead, fathead, and thickhead ~ thick–headed. If dump and plump are somehow connected, the problem is partly solved, but of course we don’t know whether they are. Conversely, dumps and hollow are close. Note that the word depression denotes both a hollow and low sprits.

Dimple and dump may be related, but what a world of difference!

Dimple and dump may be related, but what a world of difference!To repeat: in my opinion, the most problematic word in the entire group is damp. It is sometimes supposed to be allied to Latin fūmus “smoke” (which we know from fume) and even to s-team, assuming that s- in steam is the so-called s-mobile, an evasive sound whose ghost has appeared in this blog more than once. In case dank has anything to do with my story, we have one more candidate whose legitimacy is doubtful but not improbable. I also wonder (a heretical thought) whether all those words have anything to do with deep! Damp ~ dimp- ~ dump– could be onomatopoeic (sound-imitative), though damp does look like an odd man out. An inconclusive story, I admit, but gleaning is hard when the ground is covered with frost and snow, as in the famous children’s poem about two little kittens.

Ablaut

I have a few more interesting questions but will answer them in the next set of gleanings. Today I’ll only touch on the query about ablaut, because it is connected with what has been written above. Ablaut refers to the fact that in Germanic, as in the other Indo-European languages, vowels alternated according to strict rules. In Germanic, there were six series: .1. ei ~ ai ~ i ~ i. 2. eu ~ au ~ u ~ u. 3. e ~ a ~ u ~ u. 4. e ~ a ~ ǣ ~ u. 5. e ~ a ~ ǣ ~ e, and 6. a ~ ō ~ ō ~ a. (in Classes 3, 4, and 5, I did not specify the consonants following the vowels; they have no bearing on my brief note.) Those series were like non-intersecting railway tracks. For instance, i was not allowed to alternate with u, because they belonged to different series. Some vestiges of the old system of ablaut can still be seen in the principal parts of such English verbs as rise ~ rose ~ risen, find ~ found, speak ~ spoke, get ~ got, and others like them (grammars call such verbs strong) and elsewehre. In all handbooks, the alternating series of vowels are given in the order presented above, from 1 to 6. The question was from a correspondent who knew that the scheme had been offered by Jacob Grimm (few non-specialists are aware of this fact), but he wondered why it was established in this order. I do not know. The numbering was, I assume, arbitrary, but perhaps the reason was this: The first and the second “class” have diphthongs in the first two parts (ei ~ ai and eu ~ au), so Jacob Grimm perhaps thought that it would be logical to begin with them. I have no materials to confirm my guess, but I don’t think he explained his coinages and orderings anywhere.

Featured image credit: IMG_7369-1500 by Bengt Nyman. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Images: (1) “Guinea pig” by vantagepointfl. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay. (2) “Soup dumpling” by Andrew Mager. CCo CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr. (3) “Woman, smile” by bearinthenorth. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Humpty Dumpty and his kin appeared first on OUPblog.

The wonderful poetic production of Langston Hughes

Langston Hughes, whom Carl Van Vechten memorably called “the Poet Laureate of the Negro race,” was born on 1 February 1902 in Joplin, Missouri; he died in New York City on 22 May 1967. This year, then, we celebrate Hughes‘ birthday at the beginning of what is now Black History Month, and we honor the fiftieth anniversary of his untimely passing. Remembering Hughes will no doubt lead to more books, articles, and conferences, which is as it should be. This work will be added to what has already been written about Hughes, much of it based on the Langston Hughes Papers at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale.

Given these riches, one would imagine that there is little left to discover about Hughes. And yet, new material—new to us now—still surfaces from time to time. The story I would like to share here, however briefly, has to do with one such unexpected surfacing. It speaks loudly to the international reputation Langston Hughes enjoyed for most of his life, something we tend to forget here at home.

On 20 October 2016, I received an email from Nora Galer, one of Julio Galer’s three children, who, it turns out had been living in New York City for the past twenty-five years. She told me that she has in her possession all the letters her father, who passed in 2006, had kept from his long correspondence with Langston Hughes. If you don’t know who Julio Galer is, you’re not alone, and that is the point of recounting this story.

Born in Argentina, Julio Galer was one of Hughes’s many literary translators, and, as we well know, translators tend to be rather invisible. They certainly have not exactly received the attention they deserve. Galer stands out among those who translated Hughes’s writings into many languages because his interest in Hughes’s work was much more than a passing fancy. Starting in the later 1940s, Julio Galer worked tirelessly on his Spanish translations of Hughes’s autobiographical writings, fiction, plays, and of course poetry. In 1956, he published a hefty collection of his versions of Hughes’s poems in Buenos Aires. Throughout all this, Galer and Hughes corresponded for almost twenty years, from 1948 to 1966.

Langston Hughes in 1943. Photo by Gordon Parks for the US Office of War Information. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Langston Hughes in 1943. Photo by Gordon Parks for the US Office of War Information. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.I was familiar with Galer’s translations and had written about them in The Worlds of Langston Hughes (2012), but I had no idea about the extent of his correspondence with Hughes. All I knew at the time was that he had sent Hughes a copy of his book, Poemas de Langston Hughes, which I had found at Beinecke Library, along with the Spanish versions of Mulatto, Laughing to keep from Crying, and I Wonder as I Wander.

It wasn’t until I flew up to New York City barely two weeks after Nora Galer’s email, talked with her at length, and perused her father’s papers, that I began to appreciate how much of a serious commitment Julio Galer’s Hughes translations had been from the very start. “You see, Mr. Hughes,” the twenty-three-old Galer writes in his first letter from April 1948, “I do not undertake this heavy task just for commercial purposes, I do not make my living translating but teaching. But I want to put at the disposal of the Spanish speaking public your wonderful poetic production.… In my opinion the translator is like the apostle, because, like him, his mission is to spread the holy word, in this case the holy word of beauty and knowledge.”

What attracted Julio Galer to Hughes’s poems was a shared literary sensibility, which is what made Galer such an extraordinary translator of Hughes’ writings, especially of the poetry. Yet, one looks in vain for at least a word about Galer’s important work as a literary translator in the obituary published in 2006 by the International Labour Office, for which he worked from 1959 to 1987. But at least there is a reference to his “rare sensitivity to human and historical situations.” Julio Galer and Langston Hughes almost met, but not quite. Truly a shame, that.

Let me end with an anecdote that speaks to Langston Hughes’ afterlives, and not just in translations. When we first met, Nora and I decided to pay homage to Hughes by visiting his old brownstone on 20 E. 127th Street in Harlem. Hughes lived there during the entire time Julio Galer and he corresponded. As we lingered on the steps of this run-down, empty building, a garrulous neighbor walked up to us. The good news he told us was that Langston’s house was finally being fixed up. By whom? we asked. We were especially curious because of recent efforts by the I, Too, Arts Collective to raise money to rent this landmark and use it as a space for younger poets and musicians. The fellow’s answer came as a surprise: “By his children, of course.” He insisted, even after we gently put to him that Hughes did not have any children—at least not biological ones. I don’t think the man was referring to Renee Watson and the other poets who are trying to raise money to save Hughes’s old home from being gentrified. By hindsight, thought, I guess he was right, in a sense. In the end, it all depends on who counts as kin.

Featured image credit: The poem Danse Africaine on the wall of a building in The Netherlands by Tubantia, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The wonderful poetic production of Langston Hughes appeared first on OUPblog.

On the economics of economists

We economists spend a lot of time writing about the job market. Can the unemployment rate drop any further? Will the number of unemployed people increase when the Fed starts to raise interest rates? And will wages begin to pick up if the unemployment rate does drop?

To pursue these questions, economists construct theoretical models of the labor market, gather hiring and wage data from a variety of industries and regions, and–in the United States–pore over the monthly employment situation report which is published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics at 8:30 am on the first Friday of the month.

But what about the market for economists? Having recently returned from the largest regular gathering of economists in the world, the annual meetings of the American Economics Association, I can report from the front lines of the market for new economists.

In 2014, US universities produced nearly 1200 PhD’s in economics; the number that will be produced in 2017 is probably similar. Those expecting to complete their PhD’s in 2017 have been busy for the last few months preparing their job market papers. These papers are typically a chapter from their PhD thesis, usually the one that job candidates (and their academic advisors) believe to be their most promising work. Most new PhD’s have already spent four or more years in graduate school learning economic theory, statistics, and the nuts and bolts of their own specialty (e.g., international economics, macroeconomics), but for most candidates the job market paper will be one of their first major pieces of serious research.

During the fall semester, candidates polish their job market papers to a high-gloss, give practice presentations to faculty and other graduate students (or anyone who will listen), and line up faculty members to write letters of recommendation. They also practice their pitch—the 30-second elevator pitch, the 3-minute cocktail party pitch, and the 10- to 15-minute job interview pitch—so when someone at the meetings casually asks about their research, they will have an answer of the appropriate length. There is an interesting piece on navigating the economics job market by John Cawley.

Sometime during the period between August and November, ads appear in the American Economics Association’s Job Openings for Economists—or JOE, for short. The ads cover a wide range of jobs: permanent and temporary academic jobs from large research universities and small teaching colleges, non-academic jobs including the Federal Reserve, agencies of the United States government (including the CIA), and a variety of jobs in state governments, international institutions (e.g., the World Bank and International Monetary Fund), and consulting firms.

And then the rush begins. Up until about 10 years ago, applications came in via US mail and with the assistance of a lot of photocopying; our office was routinely buried in paper for three months. Now, much to the relief of our administrative assistant, jobs are applied for via e-mail and online submission.

Employers have a variety of attitudes toward field specialization. The top 10-20 university economics departments typically do not care too much about the applicant’s specialization—they are just looking for the best economist they can hire. Many, however, will have a preference: if there is a newly endowed chair in finance, well, a microeconomic theorist—even a very good one—won’t stand a chance. Because submitting an application is now cheaper—no postage or photocopying to pay for— it is also easier to send more of them, and to send them indiscriminately. This year, my university advertised for a particular sub-specialty (open economy macroeconomics)—of the 300 or so applications received, about a third of them came from applicants who had little to no background in that field (needless to say, this reduced the amount of time we spent on those applications).

The top 10-20 university economics departments typically do not care too much about the applicant’s specialization—they are just looking for the best economist they can hire.

After sifting through a dauntingly large number of applications, we pared down 300 applications to 16 plausible candidates. We met these candidates for 30 minutes each in a hotel suite at the Economics Association’s annual meetings, which took place this year in Chicago, on 6-8 January. (Quick advice to convention organizers: Chicago is a wonderful city; it is a lot less wonderful in January when the city becomes one big walk-in freezer.)

The economics meetings are huge. In addition to hundreds of sessions devoted to academic presentations (which I would have been happy to attend if I hadn’t been interviewing job candidates), it is a great time to meet up with old friends in the profession, and to stroll through the exhibitors’ hall to see the latest in computer software, textbooks, databases—as well as pick up as many free pens and souvenir mugs as you can carry.

The evidence suggests that the economics job market works reasonably well. Research on the economics job market during 2007-2010 suggested that 94% of newly minted economists found employment during the job market season and two-thirds got jobs that matched their preference (university, government, etc.) and another got their second choice type of job. A 2013 survey by the National Science Foundation found an unemployment rate among those with PhD’s in economics of less than 1%, suggesting that longer term employment prospects for economics PhD’s are pretty good.

And the pay is pretty good too. The most recent survey of salaries in the market for new PhD’s, conducted by the Walton Business School at the University of Arkansas suggests that the average pay for a new faculty member in economics averages in the low to mid-six figures for folks who snag jobs at PhD granting institutions, somewhat less for those teaching at non-PhD granting institutions.

My own university’s search for a new economist is not yet complete. At the time of this writing, we have invited a subset of the candidates we interviewed in Chicago to come to campus and spend a day interviewing, presenting their job market paper, and spending some time socializing with potential future colleagues. We are anxiously awaiting them and hope that we like them, they like us, and a match will be made so that we can live happily ever after.

Featured image credit: Chicago buildings united states by marielegoff. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post On the economics of economists appeared first on OUPblog.

Taking liberties with the text: reflections of a translator

If you have ever tried to learn another language you already know that, even for beginners, translation is never simply a matter of looking the “foreign” words up in a dictionary and writing them down. The result is gibberish, because no two languages work in exactly the same way at the level of grammar (what the rules are) and syntax (how the sentence puts them to work). But more than that, and even once you’ve taken those differences into account, it’s hard to get a satisfactory result–satisfactory to yourself as a translator learning the craft of a different language, never mind to anyone else.

Languages don’t just differ at a nuts-and-bolts level; they’re unlike each other in how they represent the world, how they convey the experience of being a speaker (which is to say, a person) within a culture. In what way, and to what kind of observer, does the sea in Homer “resemble wine” to the eye (its standard epithet, just as Achilles is routinely “swift-footed”)? Homer’s colour palette seems not just very limited, but also basically unlike ours, so the conventional rendering “wine-dark” is really just a guess–or a fudge, to cover up that we are just groping in the dark when we try to guess at what he might be trying to get across.

Conversely, if I wanted to translate “I love you” into Homer’s ancient Greek (or Cicero’s Latin), I would have to think twice about what word or words to use because our word “love” has so much baggage attached. I love my wife, my parents, my dog, a glass of wine–but not, thankfully, all in the same way. “Love” tells us that words are sticky; they pick up layers of meaning from new contexts (religion, chivalry, pop…) and it’s difficult ever to call time on their evolution (sex, family…what next?).

Things get harder still when the text we are translating won’t play fair–refuses to do a straightforward job of conveying meaning. When is a door not a door? When it’s a jar. Think for a moment on what a job you’d have putting that into French, German, whatever. And what if (even worse) the destination language expressed the world-view and experience of a culture that didn’t use doors; that was aware of jars (if at all) as a historical curiosity? No wonder translations of satirical and humorous writers so frequently need updating or replacing. Among ancient authors for modern readers and audiences, Aristophanes is a classic crux. His humour is topical–do you swap out the references for rough modern equivalents, or render them literally? It mostly depends who you decide you are translating for, which determines what kind of version you need to deliver. A crib for language learners? A set text for ancient history students? Or a script for a contemporary stage?

Wine-dark? “Sunrise, Phu Quoc, Island” by quangle, CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

Wine-dark? “Sunrise, Phu Quoc, Island” by quangle, CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.Whatever way you slant it, something must be lost. Swap Cleon for Trump? You’ve muddied the sense of Aristophanes’ original! Leave Cleon as Cleon? Now no one is laughing!–and that, for a comedy meant for a mass audience, is its own and perhaps inexcusable kind of infidelity. We always translate for particular audiences, in the first instance and perhaps always foremost ourselves (or else, why bother?), but we can never control which audiences will actually pick our version up and either castigate it or, sometimes worse, make it their own.

As with colours (Homer’s sea), so with sexual innuendos and outright accusations/bragging–again, the ancient world (through its languages) simply breaks up human experience into different chunks, processes and categorises it differently. In a post-Foucauldian scholarly world, it is common knowledge that “homosexuality” only came into being (initially through medicalisation) at the tail end of the nineteenth century–and “heterosexuality” shortly thereafter; but that isn’t the half of it. To translate (as I have, and do) the first-century AD satirical epigrammatist Martial, who is perhaps the muckiest of ancient authors, is always to harbour the suspicion that–through profound cultural difference, expressed through language that is at the same time humorous, and colloquial, and obscene–we are being laughed at.

Will we ever get every last nugget of nasty innuendo out of his text? Perhaps we should be glad not to–but changing times bring new possibilities for Martial’s readers in English. For instance, in 10.68 Martial complains that a Roman girl of good conservative stock is making herself ridiculous by affecting the speech (“ah m’sieu!”) and mannerisms of a Greek courtesan. He even imagines her going so far as to wiggle and twitch her hips in a sexually suggestive manner: numquid, cum crisas, blandior esse potes? We have a word for it now. Criso, crisas, crisat: I twerk, you twerk, he, she, or it twerks; all this time, Martial’s Latin was waiting for us to catch up.

Featured image credit: “Home, Old, Door” by derRenner, CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Taking liberties with the text: reflections of a translator appeared first on OUPblog.

Agatha Christie at mass

In the wake of the Second Vatican Council, Dame Agatha Christie, the renowned writer of detective fiction, added her name to a protest letter to Pope Paul VI. With over fifty other literary, musical, artistic, and political figures, Christie — who’d recently celebrated her eightieth birthday — expressed alarm at the proposed replacement of the old Mass rite, which used Latin and elaborate ritual, with a new rite in English with simpler ceremonial.

Although Christie’s then husband, the archaeologist Sir Max Mallowan, was Roman Catholic, she herself wasn’t. Christie didn’t defend the old rite, nor contest the new, on the grounds that either was good or bad for the Church. Rather, along with her fellow partners in crime, she argued that the old rite had inspired countless artistic achievements, including in poetry, philosophy, music, architecture, painting, and sculpture. These, she contended, made it a universal possession of human culture that the Church had no right to abolish. The letter had a positive outcome, securing an indult allowing the bishops of England and Wales to authorize the continued celebration of the old rite alongside the new. In 1984, a similar permission was granted worldwide.

The structure and logic of Christie’s plots mirror the Mass in its full, traditional drama. Her theological anthropology is one of lost innocence, with confessions of guilt for past offences, both spoken and unvoiced, punctuating exchanges. This guilt is frequently shared, problematizing attribution. At the centre is the death of a chosen victim, which is brought about by intentional and often meticulously planned actions. This death might be vicarious, the result of misdirected malice or false identification, and might be necessary to restore an order that has been violated by other, prior sins. A large country house is an appropriate setting, providing separation, distance, obscurity, and grandeur.

The crime’s execution and motive can’t immediately be understood, even if foreboding has preceded. Meaning instead emerges later, and progressively, out of the exchanges, recollections, repetitions, and silences that follow. At the dénouement, a deeper truth than the directly visible is finally brought fully into the light, with the significance of apparently superficial circumstances fully revealed.

Both the detective and the worshipper are interpreters of action rather than people of action. Christie’s fictional and screen creations Hercule Poirot and Jane Marple are both contemplatives, comfortable while watching and waiting and rarely pursuing an investigation by frenetic activity, unless drawn into action by their deep absorption in the events around them. In a pre-forensics age, they exhibit a heightened intuitive attentiveness to their surroundings and to human character that could rightly be called spiritual. This is made possible by the continued commitment of their creator: in the case of Poirot, at least, Christie stuck with her creature even after tiring of him.

The rite and the world she loved each exhibited a degree of opacity, resisting simple rational interpretation. In churches, as in country houses, there were silent spaces for contemplation.

Christie’s literary critics have accused her of writing books that lack realism. In making this charge, they’ve failed to see that meaning is contained in structured emplotment similarly to how it’s found in the Bible and the Eucharist. What occurs is literally believable, even if improbable, and this distinguishes the classic English detective novel from science fiction. Events are also narrated as moral instruction, calling the spectator to an examination of conscience in the light of an external source of authority. However, unlike crimes with an obvious perpetrator, which may be truer to real life, detection understood as a form of art points to higher truths and purposes that help us understand life and have their ultimate origin outside of it. Although Christie’s stories aren’t high-class literature, she’s here in good company: Augustine of Hippo described the Bible, which was the book dearest to him above any other, as “unworthy in comparison with the dignity of Cicero”. In theological perspective, beauty and its source lie ultimately outside the text.

Christie has been translated into over 100 languages. What lessons might her phenomenal success, and her advocacy of traditional worship, have for Churches today? It’s too easy to view worship instrumentally, as building up the church community and preparing its members to be sent out for mission, and to opt for simple and bland texts because they’re more comprehensible. In contrast, Christie saw, in worship as in life, the importance of the classic concepts of sin and sacrifice, and of suitably evocative settings. The rite and the world she loved each exhibited a degree of opacity, resisting simple rational interpretation. In churches, as in country houses, there were silent spaces for contemplation.

In the staging and interpretation of worship, new attention needs to be given to materiality. The bread and wine, actions, movements, settings and silences of the liturgy speak louder than words, pointing beyond the visible toward truths that are typically ignored in daily life. They also connect it to the wider world beyond the Church, giving new meaning to the suffering, transformation, and creativity to be found there.

Featured image credit:”Church, Altar, Mass, Religion, Christian, Holy” by Skitterphoto. CCO Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Agatha Christie at mass appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers