Oxford University Press's Blog, page 408

February 10, 2017

Understanding AIDS

In 1981, the first cases of patients with the disease that was to become known as AIDS, were identified in hospitals in New York and San Francisco. By late 1983, the cause of AIDS — the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) had been identified. Significant numbers of cases had been reported from central Africa. In southern Africa, where I lived and worked, we had seen only sporadic occurrences — mainly among gay white men. However by 1987, HIV-infected men were identified in the workforce serving the mines industries and farms of South Africa. Armed with knowledge of labour migration and the potential for the spread of this disease, I wrote and presented my first (highly speculative) paper on AIDS at the first ‘Global Impact of AIDS’ conference held in the Barbican Centre in London.

By 1994, it was clear that the southern African epidemic was going to be horrendous. In Swaziland, the prevalence among anti-natal clinic attenders, who were a bellwether for infections, rose from 3.9% in 1992 to 16.1% in 1994. This peaked to an unbelievable 42.6% in 2004. Similar patterns were seen across the region. The prevalence was highest among younger people, who aged between 25 and 39.

I quickly realised the task for academics was to understand the causes and consequences of this disease. In particular, we needed to warn of its potential social, political, and economic impacts. Because of the long term nature of the disease, it was clear that academics had to ‘cry wolf’ long and loud. AIDS generally only emerges after a prolonged period during which a person’s immune system battles the virus. It is, like climate change, a long wave event. Those who understood this had to reach policymakers, politicians, and persuade them to take action. The tools we had to do this were, and continue to be, limited. Research and writing; talking to whatever audience will have us; and educating and influencing students.

I deployed all these strategies to the best of my ability. From 1992, I co-ran short courses on ‘Planning for the Impact of AIDS’ in countries from the Philippines to the United Kingdom via South Africa, Ukraine, and other locations. I set up and raised money for research projects, and brought in students and research assistants. I published widely. Books and articles flowed. Did they make any difference? I believe so, but it is hard to measure.

In 2005 while preparing an article which asked ‘Is AIDS a Darwinian event’, I came across the Very Short Introductions (VSI) series. I decided I had to write a VSI on HIV and AIDS. Following their acceptance of the proposal, there was the painfully slow writing process, peer review of an early version, and meticulous editing and production. Ultimately, the first edition of the HIV and AIDS VSI appeared in 2008. By 2015, it was apparent that a second edition of the HIV and AIDS VSI was needed.

We can’t ignore the most serious epidemic of the past 100 years, and if nothing else, we should learn from it.

AIDS is a fast moving epidemic and some of the data and assertions were immediately out of date. For example, the book failed to foresee the massive expansion in treatment. In 2008, there were 28.9 million people living with HIV, and a mere 770 000 were receiving anti-retroviral drugs. By 2015, there were 36.7 million people infected with HIV, but 17 million were on treatment. Of course, the current thinking is that everyone who is infected should be on treatment. Unfortunately, there is a long way to go for this to become a reality. The level of funding that the disease has received, especially from international donors, was exceptionally generous.

The election of Donald Trump in the United States and the vote where 52% of Britons said they should leave the European Union in the Brexit poll, will have consequences for the epidemic. These countries are the main international donors and have led the fight against the epidemic. It is unclear if global support will continue.

AIDS is no longer at the top of the global agenda; not even for health, where two outbreaks — Ebola and Zika, have caught the attention of the world. Environmental challenges and inequality are going to be high on the international agendas. Who is to say this is wrong, because ultimately these challenges have created fertile ground for the spread of HIV and other diseases. Despite this, we can’t ignore the most serious epidemic of the past 100 years, and if nothing else, we should learn from it.

Featured image credit: microscope slide research by PublicDomainPictures. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Understanding AIDS appeared first on OUPblog.

February 9, 2017

The European Left’s legacy of nationalism

Since the end of the Second World War, it’s been difficult to talk about nationalism in Europe as a force of progress. Nationalism, which seemed to reach its logical conclusion in violent fascism, has appeared anathema to liberalism, socialism, and other ideologies rooted in the Enlightenment. It’s been seen as the natural enemy of tolerance, multiculturalism, and internationalism. To many observers, it was nationalism’s atavistic return that explained the Balkan Wars of the 1990s. In 2016, many discerned it as the dark force behind Brexit and the election of Donald Trump. Perhaps nationalism is the shadow side of our modern liberal democracies, our destructive collective id harking back to a tribal past.

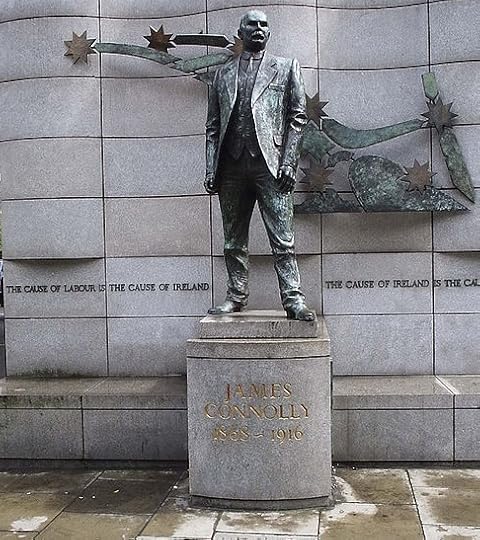

This view would have puzzled important advocates of liberal progress and social justice in nineteenth-century Europe, among them the Italian revolutionary Giuseppe Mazzini and the Irish republican James Connolly. They believed that nations existed as collective actors in history and were the best basis for organizing human society and politics. Of course, the national idea had both inclusive and exclusive implications. It was inclusive in the sense that everyone—regardless of class, status, sex, or age—belonged to the nation. Many thus viewed nationalism as the natural corollary of democracy. But it was exclusive in the sense that a particular nation represented a bounded community to which not all of humanity could belong. Yet internationalism—the belief in the fraternity and equality of nations—presupposes the division of humanity into separate nations. Who belonged to these nations and who did not? Who was best suited or qualified to lead the nation? The wealthiest citizens or the best educated? The most connected to “national” folk traditions or the most capable of delivering national glory?

Statue of James Connolly in Dublin city centre. Photo by Sebb. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Statue of James Connolly in Dublin city centre. Photo by Sebb. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Or maybe the working classes. The idea that the working classes were the authentic core and natural leaders of European nations powered forward mass socialist movements at the beginning of the last century. This did not necessarily entail aggression toward other nations; often the contrary was true. But it did entail separate trajectories for those ostensibly working-class nations. How this would play out in practice became a vexed question. Some states, like the vast multinational empires of Central and Eastern Europe, contained multiple nations; in many places, the national identity of “the people” was far from clear. Perhaps nowhere was the situation more complicated than in Habsburg Austria: a dynamic, literate, and industrializing society with no official nationalist ideology (the Austrian regime down to its collapse in 1918 was nationally agnostic or neutral), but with at least nine officially recognized national groups. In the Social Democratic movement, Czechs and Germans predominated. The movement thrived on the mobilization of Czech and German workers, who became convinced they were the true leaders of the Czech and German nations; it broke apart when they decided their paths toward a future socialist utopia lay apart, not together.

Here was an apparent paradox. Social Democracy dedicated itself to democratizing society. In Habsburg Austria, the campaign for universal male suffrage in parliamentary elections was the clearest expression of that. It culminated in 1905 with dramatic and unprecedented street demonstrations; electoral reform followed a year and a half later. But the expanding working classes that won it increasingly saw themselves in narrowly national terms. For instance, Czech socialist workers were the real Czech nation and needed to have their own movement separate from their German “comrades”. The future of socialism depended on it, in their view. Populist ethnic nationalism, then, was behind both Austrian Social Democracy’s meteoric rise and its ignominious collapse on the eve of the First World War. Workers’ nationalism was populist because it was premised on the notion that national virtue and authenticity lay not with elites, but with the laboring classes. It was ethnic because it identified the national collective not with the state, but with groups defined by allegedly inherited traits, language above all.

It’s true that the legal and political structures of imperial Austria since 1867 (the constitutional settlement that created the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary) made national separatism more likely at all levels of society. But nationalism appealed to Czech and German socialist workers at a deep cultural level. Stories of suffering, sacrifice, and redemption, drawn in part from Austrian Catholicism, had wide currency. Socialism appeared capable of redeeming and reversing proletarian suffering, which was both social due to capitalist exploitation, and national due to nefarious elites and to the interference of other nations. This proved to be an incredibly powerful idea.

Liberalism is in crisis now, and not for the first time. The rise of mass politics, including social democracy, accompanied the first major crisis of European liberalism toward the end of the nineteenth century. Today socialist parties are everywhere in retreat. Amid fears of what the current shakeup might bring, we ask whether populism is not inherently opposed to democracy. Few see progressive potential in nationalism. But it’s worth remembering that the political left in the early twentieth century harnessed nationalist and populist energies to expand political participation, not to restrict it.

What this legacy might mean for the present, whether it’s to be recalled or best ignored, is an open question.

Featured image credit: “Two signs” by Bradley Gordon. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The European Left’s legacy of nationalism appeared first on OUPblog.

After Brexit: the English question surfaces?

“Will the Prime Minister provide a commitment today that no part of the great repeal bill will be subject to English votes for English laws?” This seemingly technical query – posed by the SNP’s Kirsty Blackman at PMQs the day after the Prime Minister had outlined the government’s plans for Brexit – will have reminded Theresa May that, amidst the turmoil and drama of the current political moment, a powerful English – as well as Scottish – question is now salient in British politics. To the SNP, the new system of ‘English Votes for English Laws’, in operation in the Commons since October 2015 represents a brazen attempt by an English Tory party to turn Westminster into an English Parliament. In fact, given the balance of the current House, it is likely to become an issue only if those parts of the legislation that Brexit requires, which apply to England, are supported by an English (Tory) majority, but defeated by the Commons as a whole. And that will only happen if the Conservative parliamentary party is split, and its backbenchers willing to side with other parties and face down the howls of tabloid outrage that would follow.

But these questions of parliamentary procedure and tactics are really the tip of the iceberg. A more existential English question began to take root some years previously, well away from Westminster, in the deepening sense of disenchantment and dispossession felt by large numbers of the English, especially those who live in Northern working class communities, Eastern coastal towns, the Southern shires, those parts of the countryside where agri-business rules supreme, and the peripheral zones of the largest conurbations. It was in these regions where turnout for the Referendum was highest (and notably higher than the areas that voted for ‘Remain’), and where – as different polls have consistently shown – people are more likely to identify most strongly as ‘English’ and view the restriction of inward migration as a priority.

A growing sense of assertiveness in these places prepared the way for the English rebellion that helped deliver Brexit. Class was, of course, an important determinant of voting intention too. But its variable impact across the UK, and the strength of the English desire to vote against what the governing elite wanted, can only be understood in relation to the deep-lying dynamics – associated with de-industrialisation, deepening regional inequalities, and political disillusion – that have eroded many people’s faith in the political mainstream. These trends were palpable from the mid 2000s, but were either ignored or denied by the doyens of the political mainstream. They manifested first in the growing salience of the immigration question, and increasingly in a simmering sense that the English were the ‘last, forgotten tribe of the United Kingdom.’

Brexit “Vote Leave” in Islington, London June 13 2016 by David Holt. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Brexit “Vote Leave” in Islington, London June 13 2016 by David Holt. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Importantly, this sense of national frustration is more regionally and ethnically varied than crude stereotypes of the ‘white working class’ tend to suggest. Indeed the gathering feeling that ‘England’ provides the imagined community, where the overlooked and anxious can find some kind of authenticity and a feeling of rootedness, in a world characterised by dizzying kinds of technological and cultural change, began to generate a much more bifurcated sense of national allegiance among the English. These trends have served to undermine the ingrained habit of regarding Englishness and Britishness as labels that could be easily exchanged one for the other.

But there is of course another England to consider as well. In some of its largest and most diverse cities – most notably in London but also in places like Manchester and Liverpool – most people voted to ‘Remain.’ And it is in these places where support for Britishness, rather than Englishness is also highest in England.

These very different forms of national outlook, previously buried beneath the waves of British party politics, are – in the context of Brexit – exacerbated and made transparent. Many of the English have come to feel that London is another country, dominated by plutocrats and remote elites – even as it contributes disproportionately to public investment across the UK.

These were some of the dynamics and sensibilities I sought to reflect in the book that I published early in 2014 on this gathering sense of Englishness, and its potential political and constitutional ramifications. Since it appeared, some of the possibilities I considered turned into realities, with a speed I did not foresee, and they caught the UK’s political parties flat-footed.

David Cameron sensed the possibilities of this new mood when he raised the flag of English devolution in the aftermath of the Scottish independence referendum in 2014, but followed up with a technically complex reform that matters greatly to the House of Commons, but not to anyone else. He caught this mood again as his party commandeered the political agenda during the General Election campaign in 2015, focusing relentlessly on English fears of a weak Labour government propped up by the SNP.

In making restricting migrants a red line in its current negotiating position, and seeking to remove the UK from the Single Market, the May government appears to be ready and willing to heed the voices of the dispossessed of England. And yet it faces immense obstacles in delivering on this promise. This version of Brexit requires a re-assertion of the powers and ethos of the unitary state which are in profound tension with the multi-tiered, asymmetric polity that the UK has turned itself into, since devolution. It looks likely to generate profound conflict with Scotland, and may pave the way for a further Independence Referendum, and also with London and its financial services industries, a vital source of tax revenue for a state still seeking to reduce its public spending.

Equally, if May’s government really does seek to turn ‘Global Britain’ into a deregulated, low-tax, offshore island, it is likely that many of those who voted for Brexit will lose out once more. For the kinds of free trade arrangements which many Brexiteers appear to favour, are exactly the forces that have opened up the chasms between capital city and provinces, and between the networked and the ‘left behind’ which have done so much to bring a disaffected, political Englishness into being.

Featured image credit: flags union jack british by 27707. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post After Brexit: the English question surfaces? appeared first on OUPblog.

February 8, 2017

Face to face with brash: part 2

James Murray showed great caution in his discussion of the Modern English words spelled and pronounced as brash (see Part I of this essay). It remains unclear how many of them are related. One of the homonyms seems to go back to French, but even that word is of Germanic origin. The entry in the OED online has not yet been revised, and revising it will entail many difficulties.

To begin with, Icelandic also has a word sounding like Engl. brash. It ends in –s, but sh is a late addition to the phonetic inventory of English, so that the mismatch s versus sh is of no consequence. The real problem consists in the fact that the Icelandic word surfaced in print only in the seventeenth century. It means “bad weather; hard work, anxiety; sexual urge.” Its cognates (or seeming cognates!) in other Germanic languages mean “to burn, crackle; to fall down with a noise; arrogant, uncontrollable.” At first sight, the common semantic base of all of them appears to be “great force; impetuosity.” It accords well with Engl. brash “attack, assault,” and “arrogant” is also familiar to us from English. If we are dealing with an old word, unrecorded in Medieval Scandinavian, Engl. brash may, but does not have to be, a borrowing from Norwegian or Danish.

“Burn” appears to be at variance with “noise” and the rest, even though Germanic apparently had the noun brasa, which was borrowed into French and continues as braise “hot coals”; the word is familiar to English speakers from brazier. Burn may be an extension of the sense “spring forth forcibly like a flame”; think of, for instance, Scotch and northern English burn “little stream, rivulet.” And, if we take into account German Brunst “lust; rutting season, heat,” then Icelandic bras “sexual urge” will be a perfect match for it. A rebellious family it is: “noise, passion, fire, assault”! However, we still cannot decide whether we are dealing with a group of Germanic adjectives, nouns, and verbs (the oldest of them being burn, from some form like brennan), represented in several languages, or whether some of them were borrowed from or into Scandinavian.

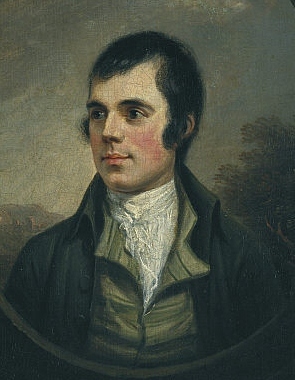

Robert Burns. Thanks to him, millions of people have heard the word burn “little stream”

Robert Burns. Thanks to him, millions of people have heard the word burn “little stream”The Century Dictionary describes the situation in the same terms as the OED. It too points to the fact that the senses overlap and make the separation of brash1, 2, 3, 4 uncertain. Additionally, it states, again exactly like Murray, that similar-sounding words designate all kinds of loud noises and are reminiscent of bash, dash, clash. Several Scandinavian and German verbs beginning with br-are cited. Finally, the obsolete, except as dialectal, Engl. brastle is glossed as “to crack; crackle; boast, brag.” When things are brittle and break, they make a noise. Here then is another possible link. In principle, it would be rather natural to derive all the occurrences of brash from some nuclear meaning “breakable, brittle; hence noisy; crack” and, by extension, even “crackle; burn.” “Rash, impetuous; sexually aroused; attack” would be natural metaphorical senses. It is tempting to follow Jacob Grimm and reconstruct a common “root” of so many divergent forms. But, as I keep repeating, semantic bridges are easy to build, and that is why they tend to collapse at the gentlest push. The history of brash is made particularly obscure because most words pronounced so turned up in written monuments late; besides some of them may be sound-imitative. We have already witnessed two points of departure but need only one.

Most of what has been said above, except for the connection brash—burn, can be found in the first edition of the OED, but there has been another attempt to discover the etymology of brash, in at least one of its senses, and it takes us in a different direction. Rather long ago, English etymologists used to cite the fish name bass as a possible cognate of brash. The Old English for bass was bærs ~ bears. Bass is the product of metathesis: the vowel and r changed places, as they did in burn “stream,” its metathesized doublet bourn (different from Hamlet’s bourne), from brunna-, and in the verb burn, from brenna-. (From burn “stream” comes the family name Burns.) Later, r was lost in the r-less dialects of British English. A similar change occurred in the fish name dace, from French dars (related to Engl. dart). German and Dutch have retained the initial form of the fish name: Barsch and baars respectively. British regional barse (known, for example, in the northwest) is their exact congener. The origin of bass is known. It is a “bristled” fish of the perch family. The root of bristle can also be seen in Borste and Bürste, the German for “bristle” and “brush.” But German (and this is the main point) also has the adjective barsch “harsh, curt, abrupt,” which can hardly be separated from the fish name and from Engl. brash. German Barsch is a northern word, which makes its ties to Engl. barse, bass even more convincing and important. The fish called bass ~ barse got its name from the sharp dorsal fin. Incidentally, Old Icelandic, had barr (that is, bar–r: the second r is an ending) “vigorous,” and it is it is probably related to bras ~ brash ~ Barsch.

This is the fish bass. It may hide the solution of the origin of the word brash.

This is the fish bass. It may hide the solution of the origin of the word brash.Above, I tried to find a common denominator for the concepts ranging from “brittle” to “sexual urge” in “great force, impetuosity” or “noise.” “Sharpness” will do equally well, if not better. It will perhaps be incautious to deny the influence of bash, clash, dash on Engl. brash. Some of its senses may not have arisen if the word had a different phonetic shape. Also, we need not assume that all the present day senses developed at the same time, especially if we again remember how late most of our attestations are. Here I am only pleading for the restitution of the fish name in the entry on brash “attack; rash, impetuous.” Those senses go very well with sharpness. The verb break might have accelerated or even caused the emergence of brash “brittle” and “broken branches.” Burning and sharpness are also good allies. On the whole, it is not too hard to produce an evolutionary line, beginning with the nuclear sense “sharp” (hence the fish name, “attack,” “pain,” “rashness”) to metaphorical senses: “impudent, sexually aroused.” In this scenario, “brittle” refuses to cooperate but can perhaps be forced into this scheme.

The conclusion is obvious. Thanks to the fish name, we seem to know more about the history of brash than our contemporary English dictionaries make us believe. The least attractive lexicographical solution would be to retain the verdict that the many senses of brash are hardly compatible or that the word’s (or words’) origin is unknown. Unknown is a loose concept. One thing is to know nothing about the subject (a possible situation: some words are indeed like aliens: they exist, but their past is beyond reconstruction), and quite a different thing is to have a hypothesis that cannot be proved beyond reasonable doubt but is good enough to stimulate further research. Our great dictionaries are timid, because their users take the verdicts given there for God’s truth. We have to advise people to give up their illusions and state frankly that the much sought-after ultimate truth is rarely achievable in etymology. However, it does not follow that we should hide behind careful, uninformative pronouncements and leave our readers in the dark. We should remain wise and yet attack, assault our target with the brashness of youth and the noisy impetuosity of an ardent lover.

An etymologist pursing his prey.

An etymologist pursing his prey.Images: (1) Robert Burns portrait by Alexander Nasmyth, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) “Bass” by PublicDomainImages, Public Domain via Pixabay. (3) “The Crown of Love” by John Everett Millais, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. Featured image: “Largemouth bass fish art work micropterus salmoides” by Raver Duane, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Face to face with brash: part 2 appeared first on OUPblog.

Is God on Facebook? [excerpt]

One university student seems to think so.

In the shortened excerpt of The Happiness Effect below, author Donna Freitas interviews Jennifer, a senior at a Christian university in the southern United States. Jennifer explains how she shares her spirituality on social media, and how she sees God in everyday Facebook posts.

From the moment Jennifer sits down for our interview, I know I’m in for a treat. She’s a bright, bubbly senior at a conservative, southern, Christian university. A pretty redhead with freckles, she talks enthusiastically about all the things she loves about her studies, her experience at college (she’s made two “lifelong friends,” she immediately tells me), and how, during her four years here, she’s been “pushed in the best of ways.” She has a ring on her finger, too— she’s engaged and thrilled about it. At the core of all these things, for Jennifer, is her faith. She’s a devout Christian and a member of the Pentecostal Church of God, and she can’t really talk about anything without bringing up her faith. Her father is a pastor, and she both teaches Sunday school to preschoolers and works with her church’s youth group on Wednesdays. Jennifer is a psychology major, and while this has challenged her faith at times, she believes that her major has helped to “expand her horizons.”

Jennifer says that one of the things she asks herself before she posts is whether or not what she writes will “uplift” others. She wants to make other people happy.

“[Religion] is a big part of my life because I do have a relationship with God,” Jennifer says. “You know, we talk on a daily basis, and it definitely influences the decisions that I make. My faith is a big part of how I decide things I’m going to do, things I’m not going to do. I don’t think I worry as much as other people do because I believe that there’s a plan and there’s a purpose for everything that’s destined by God. So I don’t have to worry about the future as much, because even though it’s unforeseen, I know that everything will be okay.”

I begin to grow curious about the ways Jennifer’s Christianity will affect who she is online and what she posts, if at all. Most of the students I’ve interviewed are only nominally religious, so faith isn’t something they discuss when they’re talking about social media. And the more devout students I’ve met usually tell me that social media isn’t the place to talk about religion, and just generally students see posts that have anything to do with God, prayer, or even worship attendance as one of the biggest no-nos of online behavior, right alongside politics. It’s the old cliché about polite conversation updated for the twenty- first century. It’s best not to ruffle any feathers on social media— you never know who might be watching.

But Jennifer is very different. At first, she sounds like most everyone else, saying that she never really posts anything bad on social media— if you have a bad day, you should keep it to yourself. She posts happy things and things she’s thankful for. Jennifer says that one of the things she asks herself before she posts is whether or not what she writes will “uplift” others. She wants to make other people happy; she believes people will be happy for her when she’s doing well, and she also gets pleasure out of seeing others doing well. Jennifer gushes about the announcement she and her fiancé made about their engagement and how many “likes” and sweet comments they got. It was her most popular, most uplifting post ever— exactly the kind of thing that belongs on social media, in her opinion.

Then I ask Jennifer if she’s open about her faith on social media. Yes, she tells me, she definitely is. At first the posts Jennifer mentions that relate to her faith seem pretty low-key. If she finds twenty dollars, she’ll post something like, “Lord bless me today, I found twenty dollars.” Sometimes she’ll ask for prayers on Facebook, too, usually for things like an exam she’s studying for or a paper she needs to get done, but never for personal or emotional needs. “I don’t think the whole world needs to see [those things],” she says. “There’s a lot of people on Facebook who, I don’t want them to know my needs. I don’t confide in them like that. The people who I would request prayers from for personal needs or emotional situations, I would confront face to face, usually one- on- one.”

“So, I think you can spread the gospel, you can spread hope, you can spread love through social media, which would be, by doing that, you would be glorifying God and you would be uplifting Him. So I think He can use social media.”

This is where our conversation circles back to Jennifer’s earlier mention of God’s plan. “I think God can use anything for His glory,” she says. “Not everything on Earth may have been set up or created to glorify Him, but I think He can use it. So, I think you can spread the gospel, you can spread hope, you can spread love through social media, which would be, by doing that, you would be glorifying God and you would be uplifting Him. So I think He can use social media.”

I ask Jennifer to explain what exactly she means.

“Yeah, yeah,” she says, laughing. “I mean, not literally, you know. He doesn’t sit down and type up a message for you, or whatever. But, yeah, I think through people, because people are the ones that are using Facebook, and God can use people, so if He can use people to do anything, to preach in a pulpit, to sing a song, He can use them to type an encouraging message on Facebook, or spread hope or love through a post that could uplift others, or encourage them to continue, you know, the fight or whatever.” It’s not as if social media is holy, Jennifer wants to reassure me, it’s just that the Lord works in mysterious ways and sometimes it’s through Mark Zuckerberg, even if he doesn’t realize it.

While so many of Jennifer’s peers are working hard to please and impress their audience— future employers, professors, college administration, grandparents, sorority sisters, and fraternity brothers— Jennifer’s number one viewer is God. She believes God is always watching her, even on social media, so she posts accordingly, trying to appear happy at all times and to inspire others, but most of all to serve God.

When Jennifer goes online, she tries to ask herself, “Will this glorify God when I post this?” She doesn’t always do it, she tells me. She’s human, so she makes mistakes. But she believes that when she’s on Facebook she’s in a “role model state,” so she feels a responsibility to do the best she possibly can to allow God to work through her.

The difference between Jennifer and almost everyone else, though, is that the effort to please God and appear happy doesn’t seem to exhaust her. Rather, she seems invigorated by it.

Featured image credit: “Social media” by dizer. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Is God on Facebook? [excerpt] appeared first on OUPblog.

A desperate gamble

“It’s a joke as far as I’m concerned.” George Carney paused to sip his beer. It was early in the afternoon on 3 August, 2016, at the Rock Island Boat Club, a little tavern behind a levee on the Illinois side of the Mississippi River. The election was still three months away and the displaced factory worker, a two-time Obama voter, was mulling his options. “Hillary is a compulsive liar and Trump thinks this is a game show.”

The next day I spoke with Tracy Warner, whom I’ve known since 2002, the year when she and Carney learned that Maytag would shift refrigerator production, and their jobs, from Galesburg, Illinois, to Reynosa, Mexico. The final shuttering of the Illinois plant in 2004 marked the end of what was once a prosperous era; nearly 5,000 workers tinkered, brazed, and assembled in the factory in the 1970s, when the factory itself was known as “Appliance City.”

That August day Warner was putting up signs and balloons for a yard sale in nearby Monmouth, Illinois. As for the election, Warner was undecided. A straight-ticket Democrat until 2012, Warner was intrigued by Bernie Sanders, but questioned ideas like free college tuition. And she was turned off by Black Lives Matter and other groups on the Left that she saw as too radical and anti-American.

George Carney stands in the front of his house in Illinois. Photo by Chad Broughton. Used with permission.

George Carney stands in the front of his house in Illinois. Photo by Chad Broughton. Used with permission.Like Carney, Warner was flirting with the idea of voting for libertarian candidate Gary Johnson. Also like Carney, she had serious doubts about Trump. “He’s always making an ass of himself and doesn’t have the savvy to be president,” Warner said. “And he says weird stuff about his daughter.” She liked his bravado and the tough talk on trade, but, with a high-school-aged son, Warner worried that Trump would get the country entangled in another senseless war.

On election day, Warner settled on Trump while Carney voted for Johnson. Clinton simply was never an option for either of them. Even a mention of her name would set them off.

Carney, Warner, and others from that Maytag factory have endured a steady erosion of their standard of living since their layoffs. Consider what a decade of downward mobility would be like for a middle-aged parent. You’re unable to take your kids to Disney World. You cut back on Christmas gifts. You might feel like less of a role model. Incomes, for many, were cut in half. A dignified and secure retirement vanished. They had followed the American work-hard-and-play-by-the-rules blueprint and yet lost out. They were going in the wrong direction; therefore the country was going in the wrong direction. They felt forsaken by their union and by their party. “I got fooled by Obama twice,” Carney said. In 2016, they were willing to vote for someone they knew was unready and potentially dangerous.

The election results, as illustrated by this “Change from 2012” map, were striking: western Illinois, along with much of the rural Rust Belt, switched dramatically to red. Election postmortems (like this one) have attempted to explain why the white working class voted for Trump. Some claim that we are witnessing a massive long-term adjustment, a political realignment. Certainly, the election returns, and the ubiquitous coverage of his rowdy rallies since June 2015, suggest a working-class embrace of Trump.

In hindsight, Trump’s strategy to attract the working class seems brilliant. He hammered away constantly on trade and jobs, and still does. When he said “I am your voice” at the RNC convention last July, some heard Orwellian demagoguery. I heard a message that would resonate with voters in western Illinois who feel, as Trump said in that same speech, “ignored, neglected, and abandoned.”

A resonant message, however, should not be mistaken for enthusiasm at the polls. As this analysis of the Rust Belt indicates (here, the “Rust Belt” is Michigan, Iowa, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Ohio), exit-poll data reveal that Democrats lost many more white voters and low-income voters than Trump gained, and that over half a million sat out the election compared to 2012. Voters like Carney who left the Democrats were more than twice as likely either to vote third party or to stay at home than to vote for Trump in these states.

This was generally true of Knox County, where the longtime appliance factory once stood. Clinton earned 3,512 fewer votes than Obama (9,939 compared to 13,451, a decline of 26%) while Trump earned only 1,250 more than Romney (10,658 compared to 9,408, an increase of only 13%).

The critical question, then, is why Clinton was never an option for so many in the white working class. From what I’ve observed in western Illinois, there’s a simple answer, and George Carney said it best. “Clinton is big money. Democrats used to be more for working people. I don’t think that’s true anymore.”

Tracy Warner in front of her home in Illinois. Photo by Chad Broughton. Used with permission.

Tracy Warner in front of her home in Illinois. Photo by Chad Broughton. Used with permission.They spurned the party because it had spurned them.

Nearly two-thirds of American workers do not have a college degree. Their prospects are bleak, and they know it, but mainly they’re worried about their children and their retirements and they want a fix. Obama came to Galesburg time and time again. He used the 2004 Maytag closing to demonstrate that he felt folks’ pain and that he was on their side. By the end of Obama’s presidency, though, not much had changed in western Illinois, and his rock star sheen had faded. But at least he had shown up. Clinton was anchored to her husband, and he to NAFTA, a fact that is lost on no one in western Illinois. “They pushed NAFTA and made it sound so good,” Carney said. “NAFTA destroyed half the country.”

Most economists dismiss this kind of talk and point to their incontestable supply and demand curves. Some, like Harvard economist and New York Times columnist N. Gregory Mankiw, turn up their nose to any dissent on the benefits of free trade, blaming ignorance and ethnocentrism.

Dani Rodrik of the Harvard Kennedy School is a rare defector among economists. NAFTA produced, he writes, only tiny efficiency gains for the United States, but incurred devastating costs for workers (e.g., job losses, wage depression) and their communities. Economists ought not to stop there: “it’s a mistake to judge real-word trade agreements strictly on economic terms, rather than social or political ones.” Trade agreements can change the rules of the game through the back door and “undercut the social bargains struck within a nation.” In providing intellectual support for these agreements, Rodrik concludes, “the trade technocracy has opened the door to populists and demagogues on trade.”

The point here is that NAFTA is about much more than the tariffs, quotas, and the theoretical benefits of free trade of Econ 101. As this report shows, NAFTA was a policy hammer wielded by corporate America against Rust Belt workers and their unions. In the free trade era that began in the 1980s, Carney and Warner not only had to compete on wages and productivity with Mexican workers—they had to compete with workers who were and are oppressed. In my field research, I’ve seen firsthand how maquiladora workers in Mexico still lack freedom of association, health and safety protections, and other basic labor standards that workers fought for and won in places like Galesburg. That’s not free competition and it’s not fair trade.

Sure, rising productivity and automation are part of the deindustrialization story, but voters in western Illinois know it’s only one component of their economic and political disenfranchisement. They see it happening all around them. Nearby, in Hanover, Illinois, a profitable factory was closed and production sent to Mexico by private equity investors looking for a quick buck. It’s no wonder free-trade-as-practiced looks un-American in western Illinois.

Admittedly, it’s difficult to draw a straight causal arrow between a declining standard of living in western Illinois and international economic policy and trade deals—and their specific effects can be dramatically overstated by political opportunists like Trump. But workers in western Illinois see that something is desperately wrong, and has been for a long time. As such, NAFTA and the Trans-Pacific Partnership have unexpectedly become potent symbols, proxies for whose side you’re on in the increasingly lopsided fight between capital and labor.

Carney and Warner remain skeptical about the Republicans. “They’ve always been the party that was bought off,” Carney said. But they are especially embittered by the party that they feel has scorned them and went with the trade technocracy. Their support for Trump may be cynical and thin, but a renegade candidate with his middle finger waving in the air has its appeal.

Having lost so much, voters in western Illinois had little more to lose.

Featured image credit: California Zephyr at Galesburg Illinois by Loco Steve. CC-BY- 2.0 via Flickr.

The post A desperate gamble appeared first on OUPblog.

Was Chaucer really a “writer”?

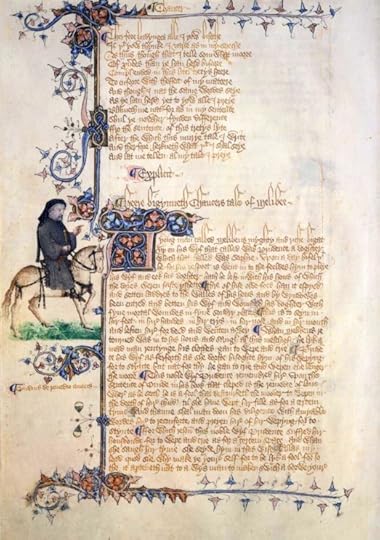

We know more about Geoffrey Chaucer’s life than we do about most medieval writers. Despite this, it is a truism of Chaucer biography that the records that survive never once describe him as a poet. Less often noticed, however, are the two radically different views of Chaucer as an author we find in roughly contemporaneous portraiture, although the portraits in which we find them are themselves well known.

We have, first, the portrait of Chaucer in the margin of the Ellesmere manuscript, one of the oldest surviving copies of the Canterbury Tales. Next to the beginning of the narrator’s Tale of Melibee, we have an image that derives directly from a tradition of drawings begun by someone who seems to have known what Chaucer looked like. The image insists on what those of us who teach Chaucer regularly try to tell our students is not true—that the narrator of the Tales is Chaucer himself. More importantly however, although Chaucer is depicted as a pilgrim on horseback, like the other images of the pilgrims in the margins of Ellesmere, Chaucer is portrayed with some of the tools of his craft. As the self-appointed recorder of the stories comprising the Tales, Chaucer is portrayed, above all, as a writer.

“MS Ellesmere 26 C 9, fol. 153v.” Public Domain via the Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

“MS Ellesmere 26 C 9, fol. 153v.” Public Domain via the Huntington Library, San Marino, California.As can be seen more clearly in this detail, what Chaucer has hanging around his neck is a writing instrument a “penner” or pen case.

“MS Ellesmere 26 C 9, fol. 153v., detail”

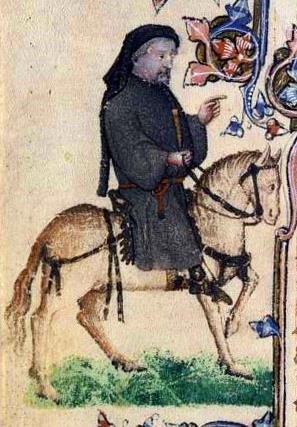

“MS Ellesmere 26 C 9, fol. 153v., detail”A second view of Chaucer as author comes from the frontispiece of one of the best manuscripts of Troilus and Criseyde, now held in the library of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. Here, Chaucer is standing, and in court rather than on a pilgrimage, although this depiction of Chaucer seems to borrow from the same tradition of portraiture as the Ellesmere image (this Chaucer also has a beard, a similarly high forehead, and a head bowed slightly and purposefully). What this Chaucer does not have, however, is a penner or pen.

The caption traditionally given to this image’s reproduction in the many books it has graced is “Chaucer reading from a book”. But, as Derek Pearsall put it gently, with characteristic astringency, in a landmark article on this image, “the book from which ‘the Poet’ is supposed to be ‘reading’ is not at all obvious in the picture since it is in fact, not there”. This Chaucer is not a writer but a declaimer or reciter and, given the location of the picture, as the frontispiece to this deluxe copy of Troilus and Criseyde, what he is almost certainly meant to be reciting is Troilus.

“MS 61, fol. 1v” Image reproduced with kind permission of the Master and Fellows of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge.

“MS 61, fol. 1v” Image reproduced with kind permission of the Master and Fellows of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge.The two images differ in the claims they make about how Chaucer disseminated his work, but they agree more subtly about the importance of orality to the making of Chaucer’s texts. Although the prologue to the Tale of Melibee represents the Tale as something Chaucer writes, it also represents the tale as something to be listened to (“therefore herkneth” [VII.965] the narrator says). The slippage is conventional as any scholar of Middle English would be quick to say and probably derives directly from the Middle English romances in which Chaucer’s style was schooled. But the convention derived from practice that regularly mixed declaiming with writing since, even if these romances were written as if they were being recited, they were also often recited to the kind of audiences the Troilus frontispiece depicts.

The image of Chaucer in the Troilus frontispiece relies on a pictorial tradition depicting the oral delivery of sermons, as Derek Pearsall also noted, but this raises the interesting possibility that Chaucer could perform the poem in this way because he could hold the whole of it in his head, and therefore “wrote” it in the first place by dictating it. This is a possibility almost never considered for the performance or production of Chaucer’s works, yet we know it was quite common from antiquity through the Middle Ages. One might say that the image of Chaucer in the Corpus Christi frontispiece is traditional, but it relies on a tradition in which the author of a text does not write it out so that it can be read, but, rather, recites it so that it can be written.

Since, by definition, every trace of such dictation would have vanished, it’s hard to find evidence for it. But it would solve some problems. There are a number of key passages in Troilus and Criseyde itself that come and go in ways that cannot be easily accounted for as errors of copying: it is as if Chaucer recited the poem with some passages on one occasion but not on another. And we do know that dictation was common in England among men and women of Chaucer’s class in the fifteenth century.

While our own habits of writing incline us to think that an image of Chaucer reciting the whole of Troilus and Criseyde is fancy rather than fact, it’s significant that we have this second view at all. Chaucer must have set penner to parchment frequently. However, the portraits of Chaucer also suggest that it was equally likely Chaucer also often wrote by reciting to a secretary. That is, without actually “writing” at all.

Featured image credit: “William Blake-Chaucer’s Canterbury Pilgrims”. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Was Chaucer really a “writer”? appeared first on OUPblog.

Measuring belief?

Pop quiz: What do standing in a long line outside a temple on New Year’s Eve, kneeling alone in a giant cathedral, and gathering around with 10-15 friends in an apartment room all have in common? It’s kind of an unfair question but the answer is that each of these would qualify equally as a statistical instance of “having prayed” despite the glaringly different social context and relational ramifications of the action itself. My little gimmick highlights an important question about religious research: do our standard operationalizations actually capture what we want them to? Are instances of the “same” religious practices commensurate across traditions and cultures?

Global, comparative statistical studies remain important research goals, and for good reason. Religion remains a significant element of modern life, and may be growing in importance given its common role as a source of push-back against the forces of globalization or as a globalizing force itself. We are right to want to understand what is going on on the ground and what larger trends are in play and the implications they may have. However, if our metrics are faulty, at best we will be playing with partial findings. At worst, we will end up with terribly skewed visions of global religious trends.

For American and European researchers, the question of what is behind the numbers does not typically cause much pause. The statistically marginal nature of anything but Christianity in these two regions has meant a certain assumed uniformity of measurement. While there have been some protestations from Catholic quarters that our metrics are too Protestant, rethinks have only come on rather momentous issues. One example would be the slow jettisoning of RELTRAD as it became increasingly clear that liberal/conservative told us a lot more than did Baptist/Presbyterian.

Religion remains a significant element of modern life, and may be growing in importance given its common role as a source of push-back against the forces of globalization or as a globalizing force itself.

When we look outside classically Christian cultural contexts, however, the usefulness of our measures begin to rapidly decline. In my research context (Asia: most specifically China and Japan), unless you are dealing with Christian communities (and even then it is not a sure thing), self-identification and attendance, two typically key indicators, are misleading. Unless you are talking to a priest linked to a particular religious tradition (Daoist, Buddhist, Shinto, etc.) or one of the few fervently committed practitioners, belonging isn’t as important as efficacy. Even if you are not personally Buddhist or Shinto, that won’t keep you from seeking out shrines and temples known for their practical impact on everything from healthy births to successful test scores to safe travels, regardless of a given deity’s affiliation. Similarly, the concept of weekly attendance at religious events is purely a Christian imposition on the data. That just is not how religions in China and Japan work. Attendance has more to do with major life events and significant festivals. Measured on that scale, the Chinese and Japanese are far more faithful then they are often given credit for.

Returning to my pop quiz, it is not just the points of difference that should give our statistical endeavors pause; it is also the points of similarity. Prayer is one of the few practices in which nearly every religion can find some common ground. If there are superhuman powers, then communicating with them would be the natural province of a religion. Yet, if we are interested in the social nature and impact of religion, how people pray is just as important as whether they pray. We are, ultimately, most interested in the causal nature of prayer – the causal mechanisms that such actions activate and the results they tend to inspire. If we use the examples from my quiz, we can see very different possibilities for what is, statistically, the same action. All three would seem to either strengthen or draw on some personal devotion. However, the first would seem to work more as a source of communal solidarity and collective identity (a fact that was at the heart of how State Shinto was formed in the early Meiji years). The second lacks a direct communal/relational element, but would certainly heighten a sense of connection with the institutional apparatus of church…or just as easily allow for hit-and-run prayer with little broader social implications. The third, with its strong relational component could have all manner of effects.

While a cursory consideration, the point, I hope, is clear. Where religious practices are concerned, not all actions are created equal, even if we call them by the same name.

Featured image credit: A set of Jizo along the pathways near Kiyomizudera in Kyoto, Japan, photographed by the author. Used with the author’s permission.

The post Measuring belief? appeared first on OUPblog.

February 7, 2017

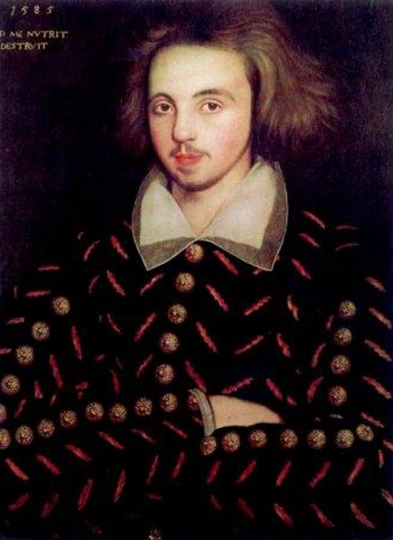

The Promethean figure of Christopher Marlowe, the quintessential Renaissance man

Christopher Marlowe was born in February of 1564, the same year as Shakespeare. He was the son of a Canterbury shoemaker, and attended the King’s School there. With fellowship support endowed by the Archbishop of Canterbury, young Marlowe matriculated at Corpus Christi College in Cambridge University in 1580-1 and received the BA degree in 1584. He may have served Queen Elizabeth’s government in some covert capacity, perhaps as a secret agent in the intelligence service presided over by Sir Francis Walsingham. He may have been recruited to this service during his stay at Cambridge. In 1597, the Privy Council ordered the university to award Marlowe the MA degree, refusing to credit the rumor that had intended to study at the English College at Rheims, presumably on order to prepare for ordination as a Roman Catholic priest. He spent lavishly on food and drink while at Cambridge to the extent that his fellowship would presumably not have afforded. He was absent for prolonged periods during his stay at the university. By 1587 he appears to have moved to London. Part I of Tamburlaine the Great, first performed in that year, took London by storm.

Ten days before he died by violent death, on 30 May 1593, Marlowe was commanded to appear before the Privy Council and then to attend them daily thereafter until “licensed to the contrary.” Although the details of this investigation are not known, a warrant for his arrest had been issued on May 18, possibly because he was suspected of having authored a treatise containing “vile heretical conceits.” He had been arrested in the Netherlands in 1592 for alleged involvement in the counterfeiting of coins. Apparently he was living at that time with Thomas Walsingham, a cousin of his more famous Sir Francis Walsingham. When Thomas Kyd’s living quarters were searched on May 12, papers of a heretical cast were found and were asserted by Kyd to have been written by Marlowe.

When Marlowe was then stabbed to death at a tavern in Deptford, the coroner’s report concluded that Marlowe had quarreled with Ingram Frizer over payment of the tavern reckoning, and that Marlowe had seized Frizer’s dagger, wounding him on the head, at which point Marlowe was stabbed fatally in the right eye. Frizer was exculpated on the grounds of self-defense. He, along with Nicholas Skeres and Robert Poley, had been employed by the Walsinghams in (among other matters) helping to foil the infamous Babington conspiracy in behalf of Mary, Catholic Queen of Scots. Whether Marlowe’s death was related to matters of Catholic conspiracy is not known. What is certain is that the Puritan-leaning divines of London trumpeted his death in 1593 as an exemplary demonstration of God’s just vengeance against a man and writer who had earned for himself the reputation of atheist blasphemer, glutton, Machiavel, and sodomist. Francis Meres wrote in 1598 that Marlowe had been “stabbed to death by a bawdy servingman, a rival of his in his lewd love” as punishment for “epicurism and atheism” (Palladis Tamia, 286v-287).

Unidentified Corpus Christi student assumed to be Christopher Marlowe. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Unidentified Corpus Christi student assumed to be Christopher Marlowe. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Tamburlaine erupted onto the London stage in two parts, in 1587 and 1588. Its subversive quality is especially manifest in the realm of struggles for political power. Tamburlaine is presented as a man who rose from rustic obscurity to imperial greatness as the “scourge of God.” He triumphed in Part I over one ruler after another, from Mycetes King of Persia to Bajazeth, Emperor of the Turks, and the Sultan of Egypt, and then, in Part II, the kings or governors of Natolia, Hungary, Bohemia, Jerusalem, and Babylon. His astonishing successes thrive on the decadence of the rulers he overthrows; an insistent theme of these plays is that established and inherited rule inevitably declines into dissipation and worldly extravagance. Given that inborn weakness of hereditary power, a shepherd of supreme self-confidence and ruthless determination can prevail against all his enemies. He relies too on his followers, Theridamas, Techelles, and Usumcasane, whom he rewards by making them monarchs under his authority and who are accordingly loyal to him the last extreme. He is, in other words, a self-made man who exploits what English audiences understood to be the gospel of Nicolò Machiavelli: might makes right. When he lays siege to a fortress, he displays his banners of white, red, and black on succeeding days: offering at first mercy to those who surrender, then death to all but women and children, then total mayhem. By invariably carrying out the dire threat signaled by these icons, even when women come to him pleading for lenity those who are innocent, he terrifies his enemies into accepting his invincible might.

Roy Battenhouse, in his Marlowe’s Tamburlaine, a Study in Renaissance Moral Philosophy (1941), has argued that the two plays of Tamburlaine constitute a composite whole ending in a way that is morally and religiously orthodox: Tamburlaine’s victories lead finally only to his death and the end of his empire. His death is edifying and divinely purposeful, Battenhouse insists. But this argument really won’t do. The two plays were performed in separate years, and the first ends with Tamburlaine supremely powerful. His ruthlessness has been vindicated, along with its subversive suggestion that any ordinary man could do the same if sufficiently ready to practice Tamburlaine’s scorched-earth methods. Moreover, Tamburlaine’s eventual death in Part II is not clearly the result of divine retribution. He has dared the authority of the gods in the name of human self-assertion, but the causes of his eventual death may well be simply those of aging and normal mortality. Wherever he goes he has taken with him the embalmed and lead-encases corpse of his wife, Zenocrate, in an attempt to defy death itself. This is a battle he cannot win. For the rest, however, he offers an unsettling model of human striving that the gods themselves do not seem to be able to prevent.

Marlowe’s other plays are no less defiant of moral order in human life or in the cosmos. The Jew of Malta centers on a Jewish merchant who plays Christian monarch off against Turkish tyrants in their struggle to dominate commerce in the Mediterranean, and does so with such audacity and cunning that he eventually becomes the ruler of Malta. To be sure, he is defeated in the end by being dropped into a cauldron of boiling oil, but this may be little more than a nominally convenient moral conclusion for a play that seethes with hubris and ingenious maneuvering. Marlowe’s best-known play, Doctor Faustus, similarly frames its action with a moral perspective by insisting that the famous magician will be damned for selling his soul to the devil in return for twenty-four years of pleasure and power. Faustus is dragged off to hell by devils at the end of the play. What could be more edifying? Yet in the course of the play Faustus turns out to be doggedly insistent on learned secrets about planetary motion and the like, daring to “practice more than heavenly power permits” (the Epilogue). Why do heavenly powers deny him the right to ask questions? In these terms Faustus becomes in part a Promethean figure, wresting powers for humanity that the jealous gods wish to deny us. And then Edward II, though it too espouses a nominal orthodoxy by having the kingship of England finally restored to just political rule, presents readers with a monarch who openly defies sexual conventionality in order to enjoy the embraces of his favorite, Gaveston.

A major contribution of Marlowe to the Renaissance and to the Reformation, then, is to dramatize the heady excitement of being what Harry Levin memorably calls him, an “overreacher” (The Overreacher, A Study of Christopher Marlowe, 1974). Marlowe overreaches in the realms of realpolitics, sexuality, the quest for knowledge, and still more. In this sense Marlowe stands before us as the quintessential Renaissance man, daring to open our eyes to possibilities that are at once visionary, frightening, and, above all, ineluctably human.

Featured image credit: page from original printing of Marlowe’s The Tragicall History of the Life and Death of Doctor Faustus, 1628 by Libris. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The Promethean figure of Christopher Marlowe, the quintessential Renaissance man appeared first on OUPblog.

Man’s best friend: the pig

Cute and heartwarming videos of dogs fill the internet. My favourite is the bacon dog tease, but others catch my attention because they reveal extraordinary animal behaviours. For example, there are many of dogs helping other animals, like opening the back door to let in a friend.

Dogs are our best animal friends, but there is a new contender. The pig might not be agile enough for Frisbees, or into making ‘guilty faces’, but like dogs, might save your life in the future.

Keeping pigs as pets is increasing in popularity, especially as sizes decrease in new breeds: pigs the size of dogs now include genetically-engineered micropigs. Gene-editing alterations to a hormone that controls growth locks pig development at a size that means these pets can cuddle with their owners on the couch without breaking bones.

Physiologically, pigs and humans are surprisingly similar. Enough so that pig organ donation might be viable in the future. The gap in numbers between those dying of organ failure and donors is so vast that France has just implemented a progressive ‘opt-out’ policy.

Recent work aimed at taking advantage of the pig as a model system for humans is being led by Craig Venter who hopes to alter the pig genome sufficiently to make pig lungs human-enough for transplantation without the normal risk of rejection by the human immune system. Another genomic pioneer, George Church of Harvard, broke the record for editing the most pieces of DNA using CRISPR gene-editing technology, snipping out 60+ parts of the pig genome to humanise it for transplantation.

Pig by PhotoGranary. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

Pig by PhotoGranary. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.Could scientists take the next giant step and grow human organs inside pigs? The entire complement of genes would then be human. A research group at the Salk Institute have taken a step in this direction and published early results in the journal Cell. Named after the fire-breathing chimera of Greek mythology, a lion with the head of a goat and a tail capped with the head of a snake, they’ve created the first human-pig cell hybrids.

Creating chimeras exceeds the boundary of research eligible for public funding in the United States: this work was funded by private donations. What is contentious about chimeras is the need to build them using stem cells, generalist cells that can turn into any type of adult cell. It is this ‘pluripotent quality’ that is needed to make them ‘take seed’ in the embryo of another species.

Like kittens and puppies who grow up together don’t fight each other as grown cats and dogs do, human cells injected early enough in the development of a different species play nice together with their foreign host cells.

The trick of crafting a viable chimera lies in fusing cells together at exactly the time: the human stems cells and pig cells both need to be in a compatible stage of development. Get it correct, as these authors did, and the result is a pig-human.

Well, sort of.

Only a tiny fraction of the pig is human. Still, these experiments offer critical proof-of-principle that it is possible to force a co-existence. And human cells aren’t building any one targeted organ – yet. But this could be achieved by knocking out the right pig genes with gene-editing, as was done in mice to ensure the growth of organs from injected rat cells. Finally, the ability of these chimeras to produce mature organs remains to be proven. They were destroyed in accordance with ethical regulations after only a few weeks. So, the starting gun has been fired but there is a long way to go to cross the finish line.

Human cells can grow in petri dishes, and now it seems, they can grow in other species, perhaps even to the point of forming transplantable organs. Might you one day owe your life to a pig?

Featured image credit: Pig in a bucket by Ben Salter. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Man’s best friend: the pig appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers