Oxford University Press's Blog, page 409

February 7, 2017

Crimes without criminals

There are crimes without victims and crimes without criminals. Financial crime belongs to the second type, as responsibilities for crises, crashes, bubbles, misconduct, or even fraud, are difficult to establish. The historical process that led to the disappearance of offenders from the financial sphere is fascinating.

In the Christian consciousness love for money was seen as a repugnant signal of greed and an obstacle to salvation: “No one can serve two masters: you cannot serve both God and Money”. This biblical precept, however, was accompanied by the ambiguous command: “Render unto Caesar the things which are Caesar’s, and unto God the things that are God’s”. St Francis was well aware of the threat hidden behind this dictum, as Christians might interpret it as a justification to establish the separate kingdom of Mammon. Usurers, however, were deemed “financial sinners”, offenders whose earnings relied upon the exploitation of time, their finances being valorized through deferral. This was a sacrilege: time belongs to God. Eventually usury was able to move freely in the Christian conscience when, as historian Jacques Le Goff suggests, the invention of Purgatory made it a venial and redeemable sin.

There were no sinners or criminals behind the financial bubble caused by the Dutch “tulip mania” in the late 1630s, when a bulb of the magnificent semper augustus reached the value of a Rembrandt’s painting. Nor was any form of criminal activity detected in similar crises occurring in Paris and London, where at most the culprits were identified as gullible investors who thought they could amass wealth overnight. Whether buying flowers or stocks, investors were the victims of ineluctable natural causes, calamities that they attracted onto themselves through their own idiocy and, as Jeremy Bentham explained, no legislation can be designed to protect idiots.

Later we keep encountering crises, not sins, let alone crimes. The UK Bubble Act 1720 attempted to regulate financial practices and prevent manias. But after it was repealed in 1825, railways, robber barons, and crooks became the protagonists of the century. The collapse of the Royal British Bank and the Tipperary Bank occurred while, across the ocean, the careers of legendary tycoons such as Jay Gould, Cornelius Vanderbilt and John D. Rockefeller were in full swing. Smaller operators or petty embezzlers were targeted, while leading businessmen were condoned. Those described as villains managed to establish a reputation as generous philanthropists, and as the wealthy Christians of the past atoned through monetary donations, the new rich set up charitable organizations. The blame for financial criminality shifted more decisively towards its victims, namely imprudent and insatiable investors who engaged in what were blatantly fraudulent initiatives.

Image credit: Wall Street Sign by nakashi. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: Wall Street Sign by nakashi. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.Blaming the victims continued for decades, leading some commentators to equate financial crime to rape, and Positivist criminologists to coin the term “criminaloid”. How many “criminaloids” were responsible for the crisis of 1929 is hard to tell. When Wall Street collapsed it became clear that innovative financial strategies had mingled with unlawful schemes, creating openings for adventurers and swindlers. In criminology the concept of ‘white-collar crime’ was forged, and offenders of high social status and respectability were finally included among its objects of study. John Maynard Keynes, who lost a remarkable portion of his investments during the crisis, described it as one of the greatest economic catastrophes of modern history, a colossal muddle showing how easy it is to lose control of “a delicate machine, the working of which we do not understand”.

The Marshal Plan activated after WW2 helped to rebuild the economy in some European countries, but simultaneously gave rise to illicit appropriation of large sums and the creation of slush funds financing political parties loyal to the USA.

The names of Drexel, Milken, Maxwell, and Leeson marked the 1980s and 1990s, when the prosecution of some conspicuous villains did not alter the perception that criminal imputations in the financial sphere are inappropriate. This sphere, it was intimated, contains its own regulatory mechanism allowing for the harmless co-existence of self-interested actors. WorldCom, Enron, Parmalat and Madoff belong to the current century, which reveals how regulatory mechanisms are sidelined by networks of greed involving bankers, politicians, and auditors.

The 2008 crisis, finally, proves how specific measures aimed at avoiding future crises are criticized or rejected in the name of market freedom. Commenting on the crisis, Andrew Haldane, an Executive Director of the Bank of England, inadvertently reiterated Keynes’ notion that knowledge of the financial world is poor and that not criminals but individuals immersed in uncertainty populate it: mistakes are made, but they are “honest’, not fraudulent mistakes, and anyone could make them given how uncertain that world is.

When the Panama Papers were released, rather than uncertainty, one certainty came to light: crimes without criminals occur in grey areas where tax evasion, bribes, money laundering, and all other forms of “dirty money” constitute the hidden wealth of nations.

Featured image credit: ‘business-stock-finance-market’ by 3112014. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Crimes without criminals appeared first on OUPblog.

February 6, 2017

Why the Logan Act should be repealed

Congress should repeal the Logan Act. Modern, globalized communications have destroyed any remaining rationale for this outdated law. The Logan Act today potentially criminalizes much routine (and constitutionally-protected) speech of US citizens.

During the presidency of John Adams, Dr. George Logan, a private citizen, engaged in freelance diplomacy with the government of revolutionary France. The Federalists, then in control of the federal government, were not pleased by what they perceived as Dr. Logan’s interference with the foreign policy of the United States.

They consequently adopted what has been denoted the Logan Act in the good doctor’s honor. The Logan Act makes it a crime for a US citizen to “directly or indirectly” conduct “any correspondence or intercourse with any foreign government or any officer or agent thereof…to defeat the measures of the United States.” Violators of the Act can be fined and jailed for up to three years. For this purpose, “government” is defined broadly to include any foreign “faction, or body of insurgents.”

The Logan Act has rarely been enforced. Its constitutionality has been questioned. But the Act remains on the books and, every now and then, rears its head.

Consider, for example, the recent report that biographer John A. Farrell discovered evidence confirming the conjecture that in 1968 the Republican presidential nominee, Richard Nixon, pressed the government of South Vietnam to resist President Johnson’s efforts to negotiate an end the Vietnam war. Through an intermediary, Nixon allegedly communicated to the South Vietnamese government that it should drag its heels and wait for a better deal from a Nixon Administration. Some have speculated that Nixon’s communications with the South Vietnamese government violated the Logan Act.

In 2008, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice and former President Jimmy Carter engaged in a very public interchange about Carter’s Logan-style communications with Hamas. I speculated then that Mr. Carter’s acerbic response to Secretary Rice’s criticism might have reflected his concern that his freelance diplomacy violated the Logan Act.

Modern communications have made the Logan Act unworkable. For better or worse, we are all instantaneously communicating across the globe with everyone. Today, Dr. Logan need not travel to France to communicate with the French government. He can tweet from the comfort of his home.

The Logan Act is an anachronism in an era of modern communications and travel.

We saw this reality during the interregnum between the Obama and Trump Administrations. President Obama and Secretary of State Kerry used their last days in office to criticize policies being pursued by the Israeli government. The President-elect promptly tweeted out his disagreement with that criticism which was instantaneously perceived around the globe including, no doubt, in the halls of the Israeli government.

Americans today travel abroad and routinely meet with foreign officials, and participate in international conferences which representatives of foreign governments also attend. Suppose, for example, that a US citizen criticizes President Trump’s views on climate change to an international audience which includes an environmental “agent” of a foreign government. Most recently, Representative Tulsi Gabbard met with Syrian President Bashar Assad.

One can envision less anodyne communications between Americans and representatives of foreign governments. However, even without the Logan Act, federal law is adequate to address any untoward possibilities. Our criminal statutes, for example, forbid a US citizen from improperly disclosing confidential information to a foreign government.

In particular instances, the contact between a US citizen and the agent of a foreign government can be a legitimate – often important – issue for public debate, as was President Carter’s contact with Hamas. I similarly doubt the wisdom of Representative Gabbard’s meeting with Mr. Assad. However, it is wrong to criminalize routine communications, as the Logan Act today does. Even the remote threat of the Logan Act’s criminal penalties can chill the exercise of American citizens’ rights of free speech.

Though the Logan Act is rarely enforced, it remains on the books, potentially available to federal prosecutors. Other laws, such as prohibitions on bribery and on the misuse of confidential information, are targeted at true abuses. The Logan Act is an anachronism in an era of modern communications and travel. The Logan Act should be repealed.

Featured image credit: Federal court reports by Open Grid Scheduler. Public domain via Flickr.

The post Why the Logan Act should be repealed appeared first on OUPblog.

The enduring legacy of François Truffaut

On 6 February 2017, François Truffaut (1932-1984) would have been 85 years old. As it was, he died tragically from a brain tumor at the age of 52, thus depriving the world of cinema of one of its brightest stars. His legacy, nevertheless, continues, being particularly evident in his influence on the current generation of filmmakers. Indeed, after several decades during which Truffaut’s reputation suffered an eclipse, with his work dismissed as “bourgeois” and sentimental, especially when compared with the political and avant-garde tendencies of his fellow New Wave filmmaker, Jean-Luc Godard, his star appears to be once again in the ascendant.

The resurgence of interest in Truffaut was signaled by the mounting of a major exhibition, “François Truffaut,” on the 30th anniversary of his death, at the Cinémathèque française in Paris, between 8 October 2014 and 10 February 2015. This exhibition displayed screenplays annotated by Truffaut, letters to and from his acquaintances–figures such as Alfred Hitchcock and Jean Genet–photographs pertaining to all aspects of his life and work, and significant documents. It was also accompanied by a retrospective of Truffaut’s films, classified according to their type: the Doinel series, tracing the coming-of-age experiences of a character, played by Jean-Pierre Léaud, between the ages of 14 and 28; the “films of passion,” such as Jules et Jim, L’Histoire d’Adèle H., and La Femme d’à côté, in which Truffaut attempts to exorcise his vision of the compulsive and destructive power of love. The five films adapted from American crime novels, comprising such films as Tirez sur le pianiste, La Sirène du Mississipi, and Vivement dimanche!; and the films on childhood, including Les 400 coups, L’Enfant sauvage, and L’Argent de poche, with their emphasis on truancy and the importance of language and inventiveness as a means of forging one’s destiny. In the words of the introduction to the exhibition, it marked “un retour complet à François Truffaut” (a full return to François Truffaut).

François Truffaut in 1965 by Nijs, Jac. de/Anefo. CC BY-SA 3.0 NL via Wikimedia Commons.

François Truffaut in 1965 by Nijs, Jac. de/Anefo. CC BY-SA 3.0 NL via Wikimedia Commons. Apart from this significant exhibition, the revival of interest in Truffaut has also been evident in a number of significant publications: Thirty-one scholars from a variety of countries contributed to a reappraisal of Truffaut’s works in A Companion to François Truffaut (2013), a documentary film, Hitchcock/Truffaut (Kent Jones, 2015), based on Truffaut’s interviews with Alfred Hitchcock, was released in 2015 and screened at the Cannes Film Festival, and a comprehensive edition of Truffaut’s interviews relating to his own work will be published in an English translation as Truffaut on Cinema in 2017.

What is it about Truffaut’s film-making that has motivated this resurrection after a lengthy period of underestimation? For the answer to this question, one needs to go to filmmakers themselves. Arnaud Desplechin, a prominent contemporary French filmmaker, gives us some clues in an extended interview he gave with the Truffaut scholars Anne Gillain and Dudley Andrew in A Companion to François Truffaut in June 2010. Having dismissed Truffaut earlier in his career, Desplechin tells us that, when he began to watch Truffaut’s films again from about 1990 onward, he was shocked to realize that they embodied a quality that was absent from the films of those filmmakers who had previously been his idols: “There was something, in every cut, that allowed each shot to exist of its own volition. Usually when you link two shots, you’re putting them in the service of a story, but here, on the contrary, the shots retain their integrity, their will. Every shot is a unit of thought.” To put it another way, “there is a dramaturgical thought each time. The entire screen is occupied by this dramaturgical thought–nothing is given to some vague naturalism, nothing to chance, nothing to the plot … There’s only cinema.”

This is the great gift that Truffaut has bequeathed by his example and advocacy to the filmmakers who have followed him–the idea, revealed in his practice, that meaning in cinema needs to be conveyed through the way in which a shot is composed and executed–which is why Truffaut averred that he wished he had been alive to make films in the silent era, before the invention of sound made it possible for filmmakers to take facile or lazy shortcuts.

But there is more to it than that. The object of fiction film-making for Truffaut–he hated documentary–was first and foremost to convey emotion, and the example he provided in this respect continues to exert a powerful influence on younger filmmakers. To take a characteristic example, the young Canadian director Xavier Dolan, who attracted the world’s attention when he won the Jury Prize at the 2014 Cannes Film Festival for Mommy, expressed the following view when asked whether he preferred Godard or Truffaut:

Truffaut. Why? Because the former enjoys himself alone; the latter enjoys himself with us … Godard could never have made a film like La Femme d’à côté. Never. Never. Because he [Truffaut] is more moving, more human, also more aware of the need to accord importance to characters and stories, rather than merely to processes, to himself, to a vision, to freedom, to a revolution, to a play on words. You don’t find this humanity in Godard’s films.

While filmmakers admire and respect Godard, they continue to love and imitate Truffaut, as is apparent not only in their eulogies, but also their practice. To take but one example: Noah Baumbach’s critically acclaimed comedy-drama Frances Ha (2012), co-written with the American actress Greta Gerwig, in which the influence of Truffaut is unmistakable: in the soundtrack, which begins by citing the theme of Une Belle Fille comme moi, in the general characterization of the protagonist as an adaptive survivor, and in the wonderfully humane blend of pathos and humor that animates the whole film.

Truffaut himself, in the longer term, thus similarly emerges as a survivor in the eyes of the practitioners in his profession. More than that, it seems that he has become one of their enduring inspirations.

Featured image credit: François Truffaut in 1965 by Nijs, Jac. de/Anefo. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The enduring legacy of François Truffaut appeared first on OUPblog.

Reconsidering prostate cancer screening

In 2011, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) issued its controversial draft recommendation against measuring prostate-specific antigen (PSA) in blood to screen for prostate cancer, claiming the test didn’t save lives. USPSTF is an independent panel of national experts convened by Congress to make evidence-based recommendations on preventive care. And the D grade that its members assigned to PSA screening regardless of a man’s age, race, or family history carried a lot of clout: since the recommendation was finalized in 2012, PSA screening by general practitioners has dropped by half, prostate biopsies are down by nearly a third, and radical prostatectomies have dropped by just over 16%.

New prostate cancer diagnoses are falling off accordingly. According to the American Cancer Society (ACS), incidence rates for early-stage prostate cancer fell by 25% between 2011 and 2013. ACS now predicts that new prostate cancer diagnoses will plummet by more than 47,000 cases in 2016, largely because fewer men than ever are being screened.

In 2017, USPSTF will issue a five-year update of its PSA screening guideline. Some experts predict the organization will soften its stance on the test. That’s because men diagnosed with low- and intermediate-risk prostate cancer are increasingly opting to have their tumors monitored rather than treated immediately. Through monitoring, men can avoid the incontinence and impotence that treatment might cause without sacrificing years of survival.

Active surveillance entails routine biopsies and checks whether PSA levels are rising. Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, MD, PhD, professor of medicine and epidemiology at the University of California, San Francisco, chairs the task force. She said that when USPSTF issued its recommendation against PSA screening in 2012 (after recommending against it in men aged 75 years or older four years before), 80% of men who had PSA-detected lesions were being treated, even though many of them wouldn’t have benefited. Indeed, 1.3 million cases of prostate cancer were diagnosed in the United States between 1986 (when PSA testing was introduced) and 2009. Of them, more than a million were treated. “Too many men were experiencing harms from the diagnostic cascade,” Bibbins-Domingo said. “So it was challenging for us to recommend PSA screening. But if alterations in treatment patterns are now affecting the balance of benefits and harms, then we look forward to reviewing new evidence to see if a different approach is warranted.”

Otis Brawley, MD, chief medical officer at ACS, speculates that “since a diagnosis of prostate cancer in 2016 no longer means a man is definitely headed for radiation or radical prostatectomy, the task force will say that population harms associated with screening have decreased enough so that we can go from a grade of D, which discourages screening, to a grade of C, which recommends offering the test to selected men depending on their circumstances.”

Some welcome a return to PSA screening. Jim C. Hu, MD, professor of urologic oncology at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York, said that despite PSA’s shortcomings—including that PSA levels can go up when someone has some other kind of prostate problem, such as an enlarged prostate—“it’s the best thing we have in the absence of sticking your head in the sand and coming into the emergency room with bone pain, weight loss, and fatigue, which are the hallmarks of metastatic prostate cancer.”

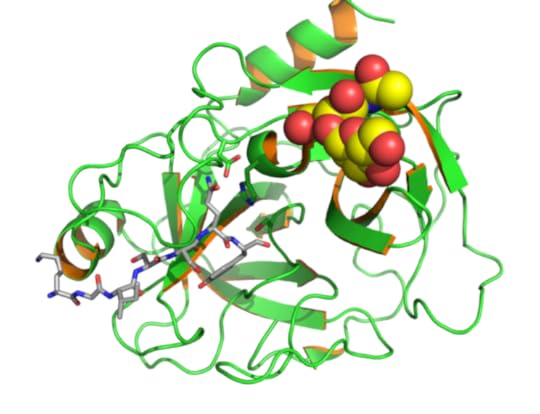

Human prostate specific antigen (PSA/KLK3) with bound substrate from complex with antibody (PDB id: 2ZCK) by E A S. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Human prostate specific antigen (PSA/KLK3) with bound substrate from complex with antibody (PDB id: 2ZCK) by E A S. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.In justifying its position against PSA screening, USPSTF cited two major studies showing that the test wasn’t much of a lifesaver. The Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial (PLCO) launched in 1993 and randomized 76,693 US men to either routine PSA screening or usual medical care that may have included screening. Follow-up data reported in 2012 showed that routine screening did not affect survival, though some scientists criticized that finding because an excess of men in the control group were given PSA tests as part of usual medical care. The European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (the ProtecT trial) enrolled 182,160 men similarly offered routine screening or usual care that may have included screening. In that study, also published in 2012, screening reduced the risk of dying from prostate cancer by about 21%. However, researchers would have to screen 1,055 men with the PSA test and detect (and potentially treat) 37 cases to prevent one prostate cancer death.

“PSA screening will help a very few avoid a cancer death and lead many men to be overdiagnosed and treated unnecessarily—and many more to go through diagnostic evaluations that can hurt and scare them,” said H. Gilbert Welch, MD, MPH. “That’s why screening is a choice, not a public-health imperative.”

The wide adoption of active surveillance has put the balance of harms and benefits from PSA screening in a new light. In a study of 1,643 men published in 2016, men who chose monitoring were as likely to live ten years after being diagnosed with localized prostate cancer as men treated with radiation or radical prostatectomy. No difference in overall survival was apparent among the three groups. The authors emphasized that survival differences could emerge with longer follow-up.

Hu’s view is that if overtreatment is now less of a problem, the benefits from PSA testing become more apparent. “Is it really so bad to find out if you’re at increased risk and then to find out if you have prostate cancer? Knowledge in this case is empowering.” Hu also worried that declines in screening could reverse a substantial drop in prostate cancer mortality since the PSA test was adopted.

But Brawley said that no reliable evidence so far indicates that incidence rates for metastatic prostate cancer are climbing. According to researchers at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, rates of metastatic prostate cancer increased by 72% between 2004 and 2013—a trend attributed partly to the drop in PSA screening. Brawley said the findings were statistically flawed because of “rookie errors” in epidemiology.

As far as alternatives to PSA screening, Brawley said none are ready for widespread use. “We all want to move away from the prostate biopsy [which has a roughly 3.5% infection rate] and to replace PSA with a more sophisticated screening test,” he said. “But even then we’d still have to consider this essential question: Does the test save lives? Too often that’s not the case.”

A version of this article originally appeared in the Journal of the Nation Cancer Institute.

Featured image credit: Medical Laboratory by DarkoStojanovic. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Reconsidering prostate cancer screening appeared first on OUPblog.

“Dickens the radical” – from Charles Dickens: An Introduction

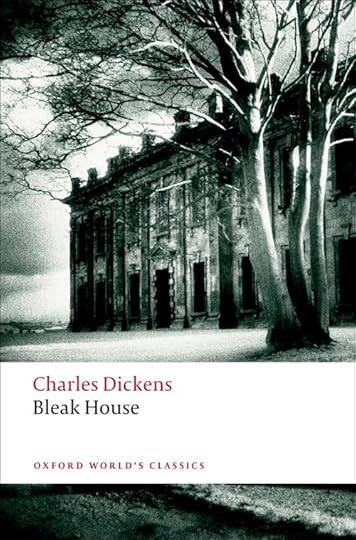

In this extract from Charles Dickens: An Introduction, Jenny Hartley explains how Charles Dickens (who turns 205 on February 7, 2017) used his novels as a form of social protest, tackling the ruling institutions and attitudes of Victorian Britain.

As Britain and her empire swelled in size and confidence, Dickens’s own belief in it diminished. For him the best of times were becoming the worst of times, Victorian high noon was dusk verging on midnight. Not that he was antiprogress. As Ruskin aptly said, “Dickens was a pure modernist— a leader of the steam-whistle party par excellence.” The titles he chose for fake book-jackets adorning his study door at Gad’s Hill succinctly express his attitude to the past: The Wisdom of Our Ancestors in seven volumes: 1 Ignorance, 2 Superstition, 3 The Block, 4 The Stake, 5 The Rack, 6 Dirt, 7 Disease. Articles in Household Words toured readers round modern factories and communication centres such as the General Post Office. But by the 1850s, rather than highlighting an issue like the workhouse or a vice like selfishness, Dickens was organizing his novels around his critique of the dehumanizing structures, ideologies, and bureaucracies of nineteenth-century Britain.

Dickens began work on Bleak House in 1851—the year of the Great Exhibition, showcase to the world for the wonders of industrial Britain. Dickens was less sure of the wonders of his nation. Bleak House was the first of a run of three novels (Hard Times and Little Dorrit followed) to tackle Britain’s ruling institutions and attitudes. His primary target in Bleak House is the legal system, exemplified by the incomprehensible and interminable Jarndyce lawsuit. “The little plaintiff or defendant,” the narrator tells us in the opening chapter, “who was promised a new rocking-horse when Jarndyce and Jarndyce should be settled, has grown up, possessed himself of a real horse, and trotted away into the other world” (Chapter 1). Those effortless transitions between horses real, rocking, and incorporeal, and between “this world and the next”: what precipitous dimensions they open up.

Bleak House by Charles Dickens

Bleak House by Charles DickensThe whole first chapter dazzles with its giddying shifts of scale expanding and contracting, converging and radiating, from the real fog of London to the “foggy glory” of the Chancellor’s wig and out to the “blighted land in every shire.” All involved in the legal system are doomed. The “ruined suitor, who periodically appears from Shropshire” and tries to address the Chancellor directly, face-to-face, has become a figure of fun. “‘There again!’ said Mr Gridley, with no diminution of his rage. ‘The system! I am told on all hands, it’s the system. I mustn’t look to individuals. It’s the system’” (Chapter 1).

If “The one great principle of the English law is, to make business for itself” (Chapter 39), other institutions are equally culpable. Religion, in the shape of the clergyman Mr Chadband, is self-regarding, greedy, and greasy. “A large yellow man with a fat smile and a general appearance of having a good deal of train oil in his system,” he spouts “abominable nonsense” (Chapter 19). Philanthropy, as embodied in Mrs Jellyby, is looking the wrong way, towards Africa instead of the inner city. The aristocracy, exemplified by Sir Leicester Dedlock, is “intensely prejudiced, perfectly unreasonable” (Chapter 2). As George Bernard Shaw commented in his 1937 Foreword to Great Expectations, “Trollope and Thackeray could see Chesney Wold [where the Dedlocks live]; but Dickens could see through it.” And that central institution of care and protection, the family itself, proves woefully inadequate. Everywhere in the book are abandoned, neglected, and exploited children, and some appalling parenting. The legal system, it becomes clear, is metonymic, synecdoche for something rotten in the state, the rottenness of the state itself. This is the prosperous nation which cannot educate its children, cannot look after its poor, cannot keep its cities clean, and cannot bury its dead properly.

In this vexed world there are no simple solutions. Quietism, staying as aloof as possible, is the path chosen by John Jarndyce as he provides succour to the defenceless. But his scope is limited, and his unworldliness lays him open to being duped, for instance by the calculatingly irresponsible “I’m just a child” Harold Skimpole. It is, surprisingly, the cottagey haven Mr. Jarndyce establishes outside London to protect his young wards, which is called Bleak House, and where Esther becomes infected with the smallpox coming out of the London slum. So it turns out that there is no good place in this novel which is un-bleak.

Featured image credit: “London lantern” by Unsplash. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post “Dickens the radical” – from Charles Dickens: An Introduction appeared first on OUPblog.

Party movements in the 2016 US election: A whisper of Weimar?

The role of party movements in the 2016 US presidential election reflected the electorate’s deep discontent and confirmed the endemic problems faced by both major political parties. The Democrats failed to articulate a unifying and persuasive message; while the Republicans failed to control the candidate nomination process. Out of those failures, party movements, which challenge existing power and advocate change, on the left and right found space to operate.

On the left, the main party movement was typical of those that have appeared during other presidential elections, arising in support of one candidate, and quickly dissolving on that candidate’s failure to secure the presidential nomination. Historical examples of this include the anti-war movement that coalesced around Eugene McCarthy’s 1968 challenge to incumbent Lyndon Johnson; his success persuaded the president not to run for a second term. Similar movements, though not on the left, were associated with John Anderson, a dissident Republican candidate in the 1980 election, and Ross Perot, who challenged George H. W. Bush in 1992. The closest parallel to this kind of party movement in 2016 was demonstrated by the enthusiastic backing that came primarily from young people galvanized by the candidacy of Bernie Sanders. Sanders campaigned against growing inequality and the erosion of the middle class, for which he blamed Wall Street and large corporations, and called for major change. But unlike the earlier examples, Sanders did not abandon the Democratic Party when he lost the nomination, and he urged his supporters to follow his example.

Some in the pro-Sanders movement did follow him, but without bringing along the backing of the now fading movement of which they had been a part. Yet, even if the movement had held together and supported the Democratic candidate, its impact would have been limited. This is because the demographic groups it represented—young, well-educated, concentrated in large cities in the Northeast–were already a part of the Democratic coalition, and additional votes from them would not have made much difference. In order to have made a difference in the outcome, the movement would have required much greater representation from older white men, the South and Northwest, rural areas, and the industrial heartland–all decisive in giving Trump his victory. No matter how much such voters felt their situation had deteriorated, the culprits identified by Sanders and his movement were too far removed and even too abstract to be reasonable sources of that deterioration.

Bernie Pre Caucus by Max Goldberg. CC BY-2.0 via Flickr.

Bernie Pre Caucus by Max Goldberg. CC BY-2.0 via Flickr.Historically, the emergence of party movements provides insight into prevailing political discontents and dissatisfaction with how established parties approach them. But, as conditions change, existing party movements may no longer capture the mood of the electorate. This is exemplified by the Tea Party movement that emerged after the 2008 election from within the Republican Party. It represented some continuity with previous insurgencies and was influential in affecting a number of Congressional races as well as the behavior of those already elected. However, by 2016, its influence was much less evident, and its irrelevance would be sealed when the movement endorsed Ted Cruz for the presidency.

With the Tea Party less important on the right, another preexisting movement gained prominence. It consisted of loosely affiliated groups united by white nationalism expressed in anti-immigrant, anti-Semitic, and anti-Muslim messages along with Nazi symbolism. It quickly found an affinity for the candidacy of Donald Trump and gave him its support. The movement was named the “alt-right” by its principal ideologist, Richard Spencer, and benefited from a skillful use of social media. The alt-right holds views similar to those of the right-wing news outlet Breitbart News, whose former chief executive Steve Bannon became a strong supporter of Trump and later was rewarded with appointment as White House chief strategist. Overall, given the election of Donald Trump, the alt-right can consider itself to have been successful in affecting the outcome of the election and even look forward to expanding its influence.

Both the Sanders and Trump campaigns espoused their own versions of populist appeals; that is, they framed their appeals in terms of the grievances of the “people vs. elites” and promised to disrupt politics as usual. J. Eric Oliver and Wendy M. Rahn confirm the pervasiveness of populism among the candidates, with Trump the strongest exponent (“Rise of the Trumpenvolk People in the 2016 Election,” Annals of the Academy of the Political and Social Sciences 667 [2016]: 189–206). But Trump also introduced an uninhibited language into the campaign that, during living memory, had not been heard in the rhetoric of a major party candidate. Rallies were often characterized by a disturbing lack of civility and acts of violence involving supporters and opponents of Trump. George Saunders, who attended a number of such rallies, gives some chilling examples. For instance, Saunders was told by one protester that two different Trump supporters had told him that they would like to shoot him in the back of the head. He also witnessed two Hispanic women, quietly watching, who were roughly thrown out of a rally. Such events evoked memories of the fall of the Weimar Republic and the street fights among Nazis, Communists, and anarchists that preceded it.

To link serious unrest generations ago in Germany with sporadic incidents in the United States may not be altogether plausible, but it still offers an apprehensive shiver. The German experience took place under very different conditions in a setting where democratic governance was not yet fully legitimated. The United States, as a mature democracy with deeply rooted institutions of governance, has incomparable advantages. Yet we should remain wary if the evolving political discourse, especially that stimulated by the “alt-right,” continues to coarsen and to threaten violence against minorities. Ten days after the election, the Southern Poverty Law Center reported almost 900 instances of harassment, intimidation, and racial slurs, of which 300 occurred in New York. In the same time span, the Anti-Defamation League similarly reported an upsurge in racist and anti-Semitic graffiti, vandalism, harassment, and assaults.

Featured image credit: Donald Trump with supporters by Gage Skidmore. CC-BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Party movements in the 2016 US election: A whisper of Weimar? appeared first on OUPblog.

President Trump: shortcuts with executive orders?

Every President is attracted by the idea of making public policy by unilaterally issuing an executive order — sounds easy and attractive. Get someone to draft it, add your signature, and out it goes. No need to spend time negotiating with lawmakers. The record, however, is not that reassuring, even when Presidents claim that national security requires prompt action.

Recall what happened in 1952 when President Harry Truman issued an executive order to seize steel mills to prosecute the war in Korea. He was promptly rebuked by a district court judge and the Supreme Court.

For some contemporary examples, think of President Barack Obama on his second full day in office issuing an executive order to close Guantánamo within a year. In that manner he hoped to fulfill a campaign pledge. Neither Obama or his legal advisers faced a simple fact: detainees could not be moved to facilities in the United States unless the administration received funds for that purpose. Public policy needed action by both branches. The money never came. Although the population of detainees declined substantially, the facility remained open when Obama left office eight years later.

Man Writing by Unspalsh. CC0 Public Domain by Pixabay.

Man Writing by Unspalsh. CC0 Public Domain by Pixabay.In his public statements, Obama often claimed authority to act alone. Speaking at the University of Colorado in Denver on 26 October, 2011, he announced: “Last month, when I addressed a joint session of Congress about our jobs crisis, I said I intend to do everything in my power right now to act on behalf of the American people, with or without Congress. We can’t wait for Congress to do its job. So where they won’t act, I will.” This type of rhetoric might have pleased audiences but had nothing to do with the need for legislation.

In his State of the Union address on 28 January, 2014, Obama pledged that in the coming weeks he would issue “an Executive order requiring Federal contractors to pay their federally funded employees a fair wage of at least 10 dollars and 10 cents an hour. Because if you cook our troops’ meals or wash their dishes, you should not have to live in poverty.” In testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee shortly after Obama’s address, Attorney General Eric Holder agreed that Obama possessed constitutional authority to act alone. Could Obama by his own powers raise the minimum wage of federal contractors? Holder told the committee: “I think that there’s a constitutional basis for it. And given what the president’s responsibility is in running the executive branch, I think that there is an inherent power there for him to act in the way that he has.”

Both Obama and Holder ignored the fact that Congress had passed legislation providing Presidents some authority over federal contractors. Obama would therefore be acting in part on the basis of statutory authority. That reality became clear a month later, on 12 February, when Obama issued the executive order. The first paragraph identified authority under the Federal Property and Administrative Services Act, codified at Title 40, Section 101. Section 1 of the order raised the hourly minimum paid by federal contractors to $10.10. Where would the money come from? There was no great mystery. Funds had to come from Congress. Section 7 of the order conceded that point: “This order shall be implemented consistent with applicable law and subject to the availability of appropriations.”

Barack Obama by 271277. CC0 Public Domain by Pixabay.

Barack Obama by 271277. CC0 Public Domain by Pixabay.It is true that an executive order issued by one President can be repealed or altered by a successor. Consider the executive order issued by President Obama on 22 January, 2009, prohibiting the coercive interrogations authorized by the Bush II administration, including waterboarding. Obama’s executive order sought to “ensure compliance with the treaty obligations of the United States, including the Geneva Conventions.” In so acting, Obama revoked an executive order issued by President Bush on 20 July, 2007. Under Obama’s order, detainees “shall not be subjected to any interrogation technique” that is not authorized by and listed in the Army Field Manual.”

During his presidential campaign, Trump promised to revive waterboarding and other coercive methods of interrogation. If he issued an executive order revoking the one issued by Obama and authorized waterboarding and other terms of torture, he would collide with his selections of Mike Pompeo as CIA Director and James Mattis as Secretary of Defense, who publicly announced their determination to comply with existing law, including specifications in the Army Field Manual.

Trump would also provoke direct confrontations with many US allies who have specifically denounced the interrogation methods used by the Bush administration. Trump’s desire to act unilaterally would invite many serious and costly downsides. His executive order for a travel ban imposed on seven Muslim-majority countries was criticized for a drafting process that excluded key officials, resulting in various changes and explanations after its release. A number of federal courts have placed limits on the administration’s policy.

Featured image credit: Fountain Pen by Andrys. CC0 Public Domain by Pixabay.

The post President Trump: shortcuts with executive orders? appeared first on OUPblog.

February 5, 2017

Can you learn while you sleep?

We will all spend about one third of our lifetime asleep, deprived of this precious ability to act and to react. During these long idle hours, little is perceived from the external world and little is remembered. For some, sleep is a refuge. For others, it is just a saddening waste. Yet, all animals, from fruit flies to humans, need to sleep and scientists have proven, time and time again, the variety of benefits that sleep has on the body and most importantly, on the mind.

In parallel, many have aspired to make a use of our nights. For example, in his novel A Brave New World, Aldous Huxley imagined a society in which sleep is used for learning. In times fueled by a fastening quest for self-optimization, finding a practical method to learn during sleep has become not only a trendy topic in fundamental research but also a new frontier for private endeavors.

Can the fantasy of learning during sleep be realized? A major obstacle is related to the fact that sleepers seem quite indifferent to what is going on in their close environment. Indeed, since sleepers do not react to external stimuli – unless they’re awoken – it is often assumed that sleepers are disconnected from the real world. Not even being able to process the material to learn should logically prevent any sleep-learning to occur. And yet, how can we be sure of what is processed (or not processed) during our nights?

Experimental evidence actually suggests that we remain, to some extent, connected to our environment. The detailed examination of brain responses to sounds during sleep revealed patterns of activity similar to wakefulness. In particular, it has been shown that, although behaviorally unresponsive, sleepers can still distinguish their own name compared to another, detect weird or meaningless sentences compared to regular ones, and be surprised when a rule shaping a stream of sounds is suddenly broken. All of this is done silently, covertly, and is only revealed when examining neural responses (through electroencephalography or brain imaging) rather than body responses. Recently, we showed that not only could sleepers process external information in a complex fashion (e.g. distinguishing spoken words based on their meaning), but they could also prepare the motor plan of the answer they were instructed to provide (pressing a right or left button) before falling asleep. These studies support the notion that the sleeping brain is not completely disconnected from its environment. The next logical step was therefore to examine whether processing a piece of information during sleep would leave a trace, a memory.

Sleep by Unsplash. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

Sleep by Unsplash. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.Early attempts to convincingly demonstrate sleep-learning have been largely inconclusive. Consequently, it has been hypothesized that sleep was a state in which the formation of new memories was inhibited in favor of the consolidation of past mnesic traces. Nonetheless, in these past few years, new, well-designed, and well-controlled investigations in both humans and animals showed that mnesic traces could be formed during sleep. Along this line, Sid Kouider and I set out to examine in finer details the nature of these sleep-memories.

Our approach was quite simple: we asked participants to classify real or fake words while falling asleep. Each word-category (real or fake) was associated to a response side (right or left). Preparing to answer a right or left response triggers an asymmetry between right and left motor cortices that we monitored with scalp electroencephalography. Thus, even when participants were unresponsive, we could check whether they correctly processed words presented during sleep.

After their nap, we presented our volunteers with the words heard during wakefulness or sleep along completely new items. Participants were instructed to indicate whether they remembered having heard a given item during their nap and to rate their confidence in their response. Unsurprisingly, participants were very good at recognizing words heard while awake but could not explicitly differentiate words heard during sleep from new ones. However, we found a difference in confidence ratings for words heard during sleep compared to the new ones. Such effect on confidence in the absence of an explicit recognition is classically interpreted as the manifestation of an implicit memory, like when you cannot explicitly remember a specific item from a list while still finding it somewhat familiar.

To buttress this interpretation, we completed the analysis of participants’ behavioral responses with the examination of their brain responses to old or novel spoken words during this memory test. Once again, we found different neural responses for words heard during sleep relative to new items. Such differences imply that participants’ brains could differentiate these two categories and that items processed during sleep left a trace within the brain. Dissecting the neural responses to words presented during sleep confirmed the existence of memories formed during sleep as well as their implicit nature.

However, it is important to stress the limited impact of these memories on behavior, making them of dubious use in our daily-lives. Learning words in a new language during sleep would be quite useless if we cannot explicitly retrieve these words when needed. Nonetheless, a recent study found an interesting application for such sleep-memories: during sleep, smokers were presented with the scent of tobacco paired to a nasty rotten fish odor in order to form an association between these two odors. Upon awakening, such pairing did not affect how participants perceived the scent of tobacco but significantly reduced their smoking habits. Importantly, the same manipulation during wakefulness did not lead to such decrease in cigarette consumption.

Hence, although faint, the implicit nature of sleep memories can be used to alter the behavior where classical wake-learning fails. But the long-term consequences of such manipulations are unknown. As said above, sleep has a crucial restorative effect on our cognitive abilities, so interfering with sleep should therefore be done wisely and taking into account the potential downsides. Learning is thus possible during sleep but is better suited for situations in which the implicit nature of the implanted memories is a positive rather than limiting factor. Otherwise, you better save your bedtime for resting.

Featured image credit: “Learning” by CollegeDegrees360. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Can you learn while you sleep? appeared first on OUPblog.

The magic of politics: the irrationality of rational people

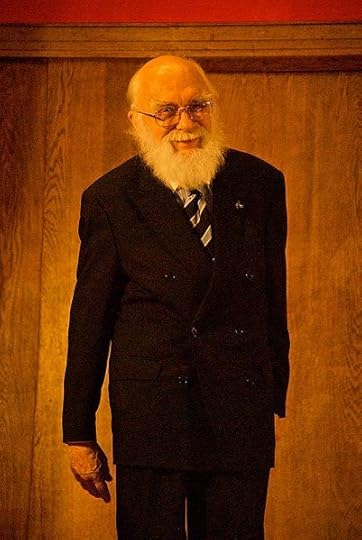

‘The Amazing Randi’ is by anyone’s measure quite a remarkable chap. His real name – Randall James Hamilton Zwinge – is pretty remarkable on its own, but over nearly ninety years James Randi has dedicated his life to challenging a whole host of paranormal and pseudoscientific claims. From faith healers to fortune-tellers, psychics to charlatans, and through to swindlers and conmen, the ‘Amazing Randi’ has debunked them all.

To understand what drives this little old man with a long white beard, a black cane, and twinkling eyes it is necessary to understand his life and how it has shaped him. Born in Ontario in 1928 James Randi dropped out of college and ran away with the circus after being amazed by a film featuring the famous magician Harry Blackstone. What followed was a life as a professional magician and escape artist who travelled the world in order to be locked in sealed boxes, hung over waterfalls, or trapped under water. In 1972 (incidentally the year of my birth but as far as I know there is no connection to ‘The Amazing Randi’) Randi entered the international spotlight when he publicly challenged the claims of a young man by the name of Uri Geller.

Now, I have no idea about whether Uri Geller has special powers or not. I don’t care. I am a simple man who can appreciate the bending of a metal spoon without asking too many questions. Apart from the fact, that is, that the spat between James Randi and Uri Geller really is something else. Randi’s position is that he has no problem with magicians fooling the public as long as it is for entertainment and fun; what he dislikes is when conmen and fakes use trickery to exploit the public. (Legal note: I am in no way linking Uri Geller with conmen or fakery. In fact I am rubbing a spoon while writing this blog.) What’s amazing is the lengths that James Randi has gone to in order to expose not only frauds, but gullible scientists who have too easily tended to corroborate supposedly special psychological powers. From the ‘Carlos Hoax’ in which Randi’s young partner pretended to be a ‘channeller’ who could provide a voice for souls from the past, through to the MacLab project in which he sent two young men to a university unit that had received funding to explore para-psychology. After months of detailed investigative scientific experiments the young men were hailed as possessing special powers only for James Randi to reveal in front of the world’s media that it was all a hoax. A film about his life and work – An Honest Liar – reveals just how cool James Randi is. He’s rocked with Alice Cooper and even appeared on Happy Days with the Fonze.

(Note to reader: metal bending skills improving – four forks and three knives now ruined.)

James Randi at Conway Hall in London, England. by John Turner. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

James Randi at Conway Hall in London, England. by John Turner. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.And yet in all the commentary and approbation regarding Randi’s unquestionably amazing life it strikes me that arguably the most important issue about the public’s relationship with charlatans and liars is over-looked: the public often don’t care!

Take the faith healer Peter Popoff as a case in point. This was the chap that filled auditoriums across America on the basis of a claimed ability to be able to heal the ill through some form of Godly connection. As if by a miracle Popoff would be able to name members of the audience, identify their illness, and then strike them down with the touch of a finger as part of what can only be described as an orgy of mass hysteria. Massive buckets, larger than modern wheelie bins, would then be distributed around the auditorium for the collection not of holy water but hard, cold, cash to allow the good work to continue. What James Randi revealed was the manner in which Popoff was less connected to God and more connected to his wife through an earpiece. The information Popoff used had not come from divine inspiration but from ‘prayer cards’ distributed to members of the audience by his staff before the show in order to collect the information he would need to pray for them. The ‘alleged’ scam was exposed to a mass American audience live on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, and within months Popoff had filed for bankruptcy.

(Note to reader: metal bending skills going into overdrive– have sculpted my car into a rabbit.)

But for me the most amazing part of the Popoff phenomenon was not poor Peter’s decline, but the manner in which he was able to resurrect (an apt word if ever there was one) his career as a faith healer and television evangelist. It was as if large sections of the public were so vulnerable or desperate that they were willing to ignore the evidence of trickery that Randi had provided. It was a blind faith that did not want to see the light. Now I have no truck with Peter Popoff or anyone who might sell Russian ‘miracle cure water’ – I can lay claim to a family visit in the 1950s by my grandfather to a faith healer who worked out of a sweet shop in Doncaster – but I am interested in the simple craving that humans have to believe in someone, in something. There is arguably a certain rationality in believing in certain things or people no matter how irrational such beliefs might be – if they allow you to retain a sense of hope that your life could improve in the future. ‘Popoff the Placebo’ might not make for an attractive stage name but it might help explain his apparent enduring attraction.

The reason the life of ‘The Amazing Randi’ made me stop and think? Because I saw in the interactions between his charlatans and swindlers and the people they duped is the same connection that I see between large sections of the public and the populist politicians who are emerging across Europe, offering a combination of nationalism, xenophobia, and snake oil. Their promises make very little sense; they feed off the vulnerable; and they garner support through a mixture of charm, menace, charisma, and guile.

‘Truth-o-Meters’ or ‘fact-checkers’ – the political equivalent of James Randi – have little purchase in an irrational world of ‘post-truth’, fake news, and all alternative facts. And that is my concern…when facts cannot be distinguished from fiction and large sections of the public feel trapped in a world they no longer understand, then the power of a political placebo may become an attractive, if irrational, option for more people.

Beware, I said before that 2017 would be the year of living dangerously, the stage is set for the sharks and charlatans, the tricksters and treats to assume control.

Featured image credit: letters deck magic by jlaso. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post The magic of politics: the irrationality of rational people appeared first on OUPblog.

Population will soon hit 8 billion. Here’s why that scares people

Any day now, global population will hit 7.5 billion. Experts predict that we humans will reach 8 billion in number sometime around the year 2024. Does that fact fill you with trepidation? Chances are that it does, even though it’s only a number, after all. “8 billion” says nothing about innovations in agriculture or renewable energy technologies, and certainly nothing about global social justice. How we will live as 8 billion, and how we will interact with our planet’s ecosystems is still a question that is very much up in the air. Yet I can predict with relative certainty that the stories that will appear when population reaches 8 billion will be couched in terms of grave concern, perhaps even catastrophic foreboding, and not solely because this is how we discussed population when we reached the milestone of 7 billion in 2011. I know this because the tendency to talk about potential cataclysm when we talk about population dates back to the origins of the word “population” itself. We literally do not have the words to discuss our collective numbers with each other without invoking potential devastation.

For the first century of what we would now retroactively call population science, both population and depopulation could have similar meanings, even though today they sound like opposites. This came about in part because of etymology and in part because it has always been easier for rulers to count dead bodies (corpses need to be buried or otherwise disposed of; and unlike living people, they don’t move about on their own accord). We inherited the etymological difficulty in part because the Latin “poplo-,” meaning army, is among the word’s roots. With this martial connotation, variations of the Latin term can refer to an army and what the army does to a place when passing through it. Moreover, the Latin noun “populatio” can refer to colonialism, so when we talk of “population,” we are also invoking the after-effects of colonialism. The Oxford English Dictionary tells us that writers first crafted this English word in the early 1600s, and for nearly a century, it included the meanings both of a gathering of people and a “wasting” of people; of a deliberate collection of bodies and the havoc those bodies have wrought.

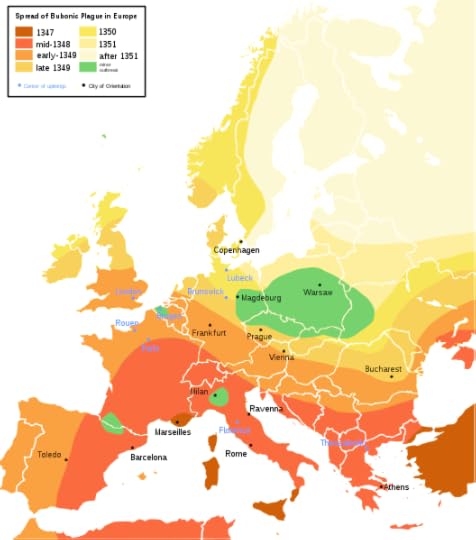

Bubonic plague-en.svg by Andy85719. COM: GFDL 1.2 via Wikimedia Commons.

Bubonic plague-en.svg by Andy85719. COM: GFDL 1.2 via Wikimedia Commons.Even if we dismiss all this as semantics, we still find that the history of counting people sets us up to discuss population in terms of cataclysmic events. The first censuses took place in the aftermath of invasions, such as the Norman Conquest, or as ways of taking stock after devastating events, like the medieval bubonic plagues. It was in response to terrible losses of life that local authorities in Europe and America would print the earliest forms of population statistics, called “bills of mortality,” or counts of how many people had recently died. The earliest speculations about population projections we have—including by people like Benjamin Franklin—came from these counts of the dead, not from counts of the living.

Finally, the element of foreboding that undergirds conversations about numbers of people endures in perhaps its most influential form in the Old Testament of the Bible. The first people to advocate for regular state censuses (like French political theorist Jean Bodin) had to spend considerable time dismantling the idea that the Bible forbade taking state-sponsored counts. The prohibition was known as “the sin of David,” and mentioning it had the power to shut down debates about keeping national counts of living people all the way up until just a few years before Thomas Malthus wrote his influential Essay. It comes from a moment in the book of Samuel in which God sends a devastating plague to the Israelites as punishment for King David’s hubris in telling his servant to “Go, number Israel and Judah.” Unlike other Biblical censuses, this one provoked God’s wrath because it wasn’t divinely ordained. Here again, daring to talk about population means talking about frightening devastation.

By the time Malthus intervened at the dawn of the nineteenth century, telling a story about the future of a world population overstretching its resources, anyone paying attention to population would have been accustomed to speaking about numbers of people in apocalyptic tones. The difference was that, before Malthus, talking about population was a way of talking about a cataclysm that had happened in the past, and after him, we all talk about the cataclysm that is to come. This is not to say that our struggles with access to resources like healthy food and health care—especially reproductive health care—aren’t real, or most importantly, that climate change and ecological devastation aren’t frighteningly real problems. On the contrary, this history shows us that these problems are all too real—they are human problems that require human ingenuity to address them. Despite the deeply ingrained history of speaking about population, the problems we face are not, in fact, mythic, or inevitable, or supernatural, or to be taken for granted.

Featured image credit: A Rolling Stones crowd – 1976 -Knebworth House B&W by Sérgio Valle Duarte. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Population will soon hit 8 billion. Here’s why that scares people appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers