Oxford University Press's Blog, page 412

January 31, 2017

Grammar for the ages: a royal intervention

The history of English grammar is shrouded in mystery. It’s generally thought to begin in the late sixteenth century, with William Bullokar’s Pamphlet for Grammar (1586)—but where did Bullokar’s inspiration come from? In these times, the structure and rules of English grammar were constructed and contrasted with the Latin. Bullokar wrote his treatise with the intention of proving that English was bound by just as many rules as Latin, and for this, he borrowed heavily from a pre-existing text: William Lily’s Latin Grammar.

No other textbook has been used for such a long period of time in English schools as Lily’s Latin Grammar. It was prescribed by Henry VIII in 1540 as the authorized an obligatory text, to be used in all schools across the country–and thereafter dominated the teaching of Latin for more than three centuries. As a consequence of this, Lily’s Latin grammar has a massive impact on not just Latin, but English as well, right up until the nineteenth century. One of England’s most famous school boys, William Shakespeare (when he was enrolled in King Edward VI School in Stratford-upon-Avon around 1571), acquired his formal education with none other than this ubiquitous grammar edition.

A number of allusions scattered in Shakespeare’s plays testify to his familiarity with the textbook. For example, Sir Hugh Evans, a Welsh parson in The Merry Wives of Windsor (Act 4, Scene 1) asks his student (William), some questions:

Evans: William, how many numbers is in nouns?

Will: Two….

Evans: What is ‘fair’, William?

Will: Pulcher.…

Evans: What is ‘lapis’, William?

Will: A stone.

Evans: And what is ‘a stone’, William?

Will: A pebble.

Evans: No; it is ‘lapis’. I pray you, remember in your prain.

The passage in Shakespeare’s comedy echoes rules in Lily’s grammar in English:

“A nowne adiectiue is, that can not stand by hym selfe, but requireth to be ioyned with an other worde, as Bonus good, Pulcher fayre…. In nownes be two numbers, The syngular and the plurall. The syngular numbre speketh of one as lapis, a stone. The plurall noumber speaketh of moo than one, as lapides, stones.”

“Latin Letters” by Tfioreze. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

“Latin Letters” by Tfioreze. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Lily’s Latin Grammar was based on a long tradition of grammar writing in the vernacular which can be traced back to the second half of the fourteenth century. From about 1400 onwards, Latin grammatical manuscripts written in English have come down to us. When printed school texts became available in the 1480s in England, short versions on elementary morphology and syntax also found their way into the classrooms. Soon afterwards, there is evidence that schoolmasters often compiled their own teaching materials which then appeared in print. After about 1510, this practice was clearly getting out of hand, and there is evidence of teachers’ and also pupils’ complaints about the large number of different versions which were circulating and in use.

As a result of this, problems arose in classrooms when children had to learn Latin using different editions, or even completely different versions of the same grammar. To solve this problem, Henry VIII issued his command that a common Latin grammar had to be used in all schools in the country. A royal committee was asked to compile the texts in English and in Latin, which were then introduced by royal prerogative in 1540.This grammar, attributed to William Lily (1468?-1522/23), was the text that has influenced the English language ever since. Sadly however, Lily did not live to see this grammar introduced and used in schools.

Lily was an eminent man and renowned teacher of Latin and Greek, as well as a close friend of Sir Thomas More and Erasmus of Rotterdam. He became the first headmaster of St. Paul’s School in 1510, and a number of his other works, especially on elementary syntax in Latin and in English, as well as those on gender and epigrams still survive. He was an excellent scholar and an outstanding teacher, and Lily’s successful teaching in St. Paul’s School was widely known to his friends and pupils—which in turn fed into the high rank and reputation of St. Paul’s School itself. As a result, this massively helped the implementation of the royal edict, as many other schools were keen to take St. Paul’s as their model and follow in their high standards. When John Milton wrote his Latin grammar Accedence Commenc’t Grammar (1669), over 60% of his illustrative quotations were taken from Lily’s grammar.

In the course of time, Lily’s name lent authority to the grammar introduced by Henry VIII, and came to signify an entire genre of textbooks. Lily’s grammar was the standard Latin school grammar, and with its influence on scholars, authors, and playwrights such as Bullokar, Milton and Shakespeare, shaped the English language for centuries after.

Featured image credit: “Grammar, Magnifier” by PDPics. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Grammar for the ages: a royal intervention appeared first on OUPblog.

Is the universe made of fields or particles?

A few ancient Greek philosophers seriously considered this question and concluded that everything is made of tiny particles moving in empty space. The key 17th-century scientist Isaac Newton agreed, but a century later, Thomas Young’s experiments convinced him and others that light, at least, was a wave, and Michael Faraday and James Maxwell showed that light and other radiations such as infrared and radio are waves in a universal “electromagnetic field.” Such physical fields are conditions of space itself, analogous to the way smokiness can be a condition of the space throughout a room. By 1900, the consensus was that the universe contains two distinct kinds of things: fields, of which electromagnetic radiation is made, and particles, of which material objects are made.

But then Max Planck, Albert Einstein, and others discovered the quantum — arguably the most radical shift in viewpoint since the ancient Greeks gave up mythology for rational understanding. Experiments with light showed radiation is made of microscopic bundles of radiant energy called “photons,” much as matter is made of microscopic bundles called protons, neutrons, electrons, atoms, and molecules. But these bundles turned out to be nothing like tiny particles moving through empty space as Newton and others had supposed. Call them “quanta.” We describe them with quantum physics, and we have good reason to think everything — all radiation and matter — is made of them.

Today we are able to study single individual quanta. At this level, we find matter and radiation to be strangely similar in ways never imagined by pre-quantum physics. Quanta of both matter and radiation turn out to be a sort of compromise between spatially extended fields and tiny isolated particles. A single electron or photon can, for example, be in two widely separated (even by many kilometers) places simultaneously, or spread continuously across a large distance much as a cloud can fill a large room. But single electrons and photons also demonstrate their particle nature by, for example, interacting with a fluorescent viewing screen in isolated tiny impacts that can be counted.

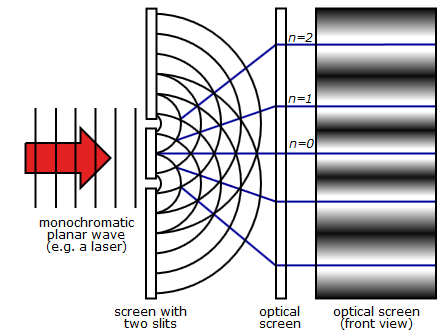

There are even a few demonstrations of both the particle and field characteristics of quanta in one and the same experiment. The best known is the so-called “double-slit experiment” first used by Thomas Young when he demonstrated light to be a wave. A light beam or electron beam is directed through a pair of narrow slits cut into an opaque screen and allowed to impinge upon a fluorescent screen placed “downstream” from the slits. A broad light-and-dark striped pattern appears on the screen, showing that each beam passed through the slits as waves that then “interfered” with each other the way waves are known to do. But when the beam is dimmed down sufficiently, the electrons and the photons make tiny individual impacts on the screen, impacts that you can count, in the way that particles do.

Two-Slit Experiment Light by inductiveload. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Two-Slit Experiment Light by inductiveload. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.The resolution of the field-versus-particles conundrum begins to appear when quanta come through the slits one at a time and we keep track of their impact points. We find that individual impacts fit into the same striped pattern that demonstrated interference, so that the striped interference pattern is formed by many small impacts the way an impressionist-era “pointillist” painting is made by many small dots of paint. This forces us to conclude that each quantum comes through both slits. As the great quantum physicist Paul Dirac put it, “each photon interferes only with itself;” the same is true of each electron.

So each quantum comes through both slits, and approaches the viewing screen in an interference pattern that spreads across the entire screen. Each quantum must embody the entire interference pattern, else how can we explain that each quantum avoids the dark stripes and impacts only the light stripes? Then, when the quantum interacts with the atoms of the screen, it collapses into a much smaller shape, vanishing over the entire screen and showing up at just one location. The details of this “field collapse” are still a subject of discussion among experts.

A quantum that comes through both slits and that embodies an entire spread-out interference pattern is not a particle. These things are waves in a field: the “quantized electromagnetic field” in the case of photons, and the “quantized electron-positron field” in the case of electrons. There are many other arguments for an “all-fields” view of the universe, but the widely-demonstrated double-slit experiment is the most direct demonstration that fields are all there is.

Slam your hand down on a table. The table slams back, as you can tell from your stinging hand. Now look at the microscopic picture: the table and your hand are made of atoms, containing electrons and protons that create electromagnetic fields. Slamming brings your hand’s electrons near the table’s electrons, causing their electromagnetic fields to repel each other. This repulsion stops your hand, and it distorts the molecules (more fields) in your hand, causing nerve cells (more fields) in your arm to transmit a signal (more fields) to your brain. Everything comes down to fields, “conditions of space.”

Featured image: Double slit x-ray simulation monochromatic blue-white by Timm Weitkamp. CC BY 3.0 de via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Is the universe made of fields or particles? appeared first on OUPblog.

Mass incarceration and the perfect socio-economic storm

In nature, there are weather conditions, referred to as ‘perfect storms’, arising from a rare combination of adverse meteorological factors creating violent storms that significantly affect the socio-economic conditions of an area. Social scientists refer to similar adverse factors as cultural amplifier effects. History shows that when leaders of empires were unable to adequately maintain a stable economy, govern diverse subcultures, and care for marginalized populations, these failures led to a socio-economic perfect-storm of cultural amplifier effects that resulted in the collapse of their respective empires.

The unprecedented and raucous 2016 presidential campaign, and its aftermath, suggests that there are several cohort pressure systems developing within the US – felons of mass incarceration, their children, and the aging baby boomers. Unbeknown to most citizens, these cohorts are significantly influencing the American culture in unpredictable ways. These pressure systems are likely to develop into cultural amplifier effects that will converge over the US, leading to a socio-economic perfect storm, and possibly leading to the collapse of the US as a world empire.

In his book, Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed (2005), Jared Diamond, believes that the elite leaders of nation-states develop a type of group-think whereby they do not notice the warning signs of social storms or, if they do notice, they may not be motivated to change the status quo. Currently, there are approximately 2000 correctional and detention facilities in the US with over 450,000 employees, and thousands of businesses with millions of employees supporting their operations. Obviously this is a large group of constituents interested in continuing the status-quo.

Rewards and sanctions are necessary for maintaining social order. However, they become counter-productive when they no longer create benefits. While only about 6% of the population is or has been incarcerated, the hidden problem is the cost to the US infrastructure when this percentage transitions from being taxpayers to tax-users. The percentage of the population effected is even higher when you consider the collateral effects to the families and communities of the incarcerated. In 2014, a little less than 3% of the US population was under some type of corrections supervision, many with non-violent offenses and mentally ill who would be fiscally better served in the community. By 2026, if policies remain the same, this population will be over nine million people, along with an estimated 24 million former felons at a budgetary cost in the trillions of dollars.

Currently, there are approximately 2000 correctional and detention facilities in the US.

A second cultural amplifier effect is the children of prisoners (including parents previously in prison), numbering approximately 13 million in 2014, according to the National Resource Center on Children & Families of the Incarcerated. In their book, Children of the Prison Boom (2014), Wakefield & Wildeman identify, that before 1990, children grew up within four main contexts: family, neighborhood, school, and family stressors. Afterwards, a new context was added – imprisonment of a parent. This exponentially increasing cohort of children will be raised in poverty and many in foster care. They have a greater potential for mental illness and addictions, post-traumatic stress, to drop out of school, and to become involved in domestic terrorism. Many will follow their parents into prison. The generational effect has and will continue to create a significant cultural group that is outside the American norm, even as a subculture.

A third amplifier effect is the aging baby boomer population, and the substantial decrease in tax income along with an increase in tax use. In 2015, the National Association of State Budget Offices reported funding for Medicaid, public aid, and corrections increased by 16% while education increased by only 8%. By 2026, these three budgets will significantly increase along with a 77% rise in social security and a 72% rise in Medicare; three-quarters of the Federal budget will be allocated for mandatory expenditures. One does not have to be a genius to understand that the price tag for the prison industrial complex will also rise exponentially. History shows us that economics played a major factor in the collapse of most fallen empires.

While the nation’s elite continue to focus on the controversial results of the 2016 presidential election, saving their respective statuses and their political parties, they fail to see the darkening storm clouds on the horizon. Shall we pretend that all is well and watch the American culture be swallowed up in a socio-economic perfect storm? Or should we have the courage to end the status quo, to tear down the structures that create apartheid groups and build cooperative, thriving communities that will sustain America through the next century?

Image credit: Chainlink fence metal by Unsplash. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Mass incarceration and the perfect socio-economic storm appeared first on OUPblog.

The future of US financial regulatory reform in the Trump era

Under the Trump Administration, many changes are in the air. Our prediction is that the post-financial crisis paradigm shift in financial regulation is here to stay. There will be a rebalancing of regulatory and supervisory goals away from a sole focus on financial stability to thinking about jobs and economic growth as well, but we do not expect to see a wholesale dismantling of the Dodd-Frank Act.

More than a week after the inauguration, the short-term outlook for US financial regulatory reform is not much clearer than it was in November for a number of reasons, including that financial regulatory reform is not at the top of the President’s agenda and that very few nominations for the financial regulatory posts have occurred. During the campaign, President Trump called for the “dismantling” of the Dodd-Frank Act while also voicing support for the restoration of an updated version of the Glass-Steagall Act. But financial regulatory reform is not even part of the Trump Administration’s White House website, while trade, immigration, and Obamacare are.

Financial regulatory reform is likely, however, to be a priority for Congressional Republicans, who have held the House of Representatives for six years but have not had unified control of Congress and the Presidency for a decade. Time out of power has given them ample opportunity to develop their own ideas for financial reform legislation. Many of the bills introduced in or passed by the House in recent years are messaging legislation—meant to stake out political positions, not to become law—but even these signal House Republicans’ willingness to consider far-ranging proposals, from changing how the Federal Reserve sets monetary policy to allowing banking organizations to opt out of enhanced prudential regulation in exchange for higher capital requirements. To understand the scope of the reforms currently on the table, it is worth considering the Financial CHOICE Act, an omnibus reform bill introduced by House Financial Services Committee Chairman Jeb Hensarling and described in detail. In the next few weeks, Rep. Hensarling is expected to release CHOICE Act 2.0, which may be more ambitious in certain aspects while scaling back some controversial proposals in an effort to win needed support in the Senate.

The key to financial regulatory reform, and the primary obstacle for Republican efforts, remains the Senate. Although Republicans hold 52 of 100 seats in that House, the filibuster enables a minority of only 41 Senators to block most new legislation. So long as the Senate keeps the filibuster and Republicans do not have a filibuster-proof Senate supermajority, we are not sanguine about the prospects of dramatic financial regulatory reform.

We do not, however, think that the currently narrow Republican majority in the Senate will be fatal for financial regulatory reform. Instead, the possibility of the filibuster may channel financial regulatory reform towards a consensus rebalancing of the Dodd-Frank paradigm shift. Many Democratic senators remain centrists, and ten Democrats will be seeking re-election in 2018 from states that voted for President Trump. Notwithstanding pressures for intraparty cohesion, these senators may feel the need to show that they can work across the aisle and with the President to craft bipartisan compromise legislation. In the context of financial regulatory reform, we expect this will lead to compromise legislation that leaves much of the Dodd-Frank Act intact but softens some of the Act’s most onerous requirements.

The key to financial regulatory reform, and the primary obstacle for Republican efforts, remains the Senate.

Finding opportunities for bipartisan consensus will require careful, evidence-driven reassessment of what the Dodd-Frank Act has accomplished, as well as its costs. Regulators have for too long pursued a single-minded focus on financial stability. With the change in Administration, the time is ripe for Congress and regulators to adopt a more balanced approach that considers not only stability, but also how regulations, individually and in the aggregate, affect investment, bank lending, market liquidity, community banks, and ultimately economic growth and job creation. By assessing both what the Dodd-Frank Act has done right and where it went wrong, policymakers can spot the low-hanging fruit for financial regulatory reform—laws and regulations that generate high costs while offering few to no corresponding benefits.

That such a reconsideration of the Dodd-Frank Act and its regulations is needed should not be surprising. We have, starting in 2008, lived through almost nine years of a financial regulatory shift. The Dodd-Frank Act required financial regulatory agencies to make nearly 400 new regulations, and since 2010, those agencies have rolled out new regulations at a breakneck pace, filling more than 25,000 pages of the Federal Register with proposed and final rules. This rush to issue new regulations, mandated by the Dodd-Frank Act’s impossible statutory deadlines, left little time to fine-tune regulations before they were released or to assess their market impacts afterwards, let alone to consider how previously enacted laws and regulations (such as the Sarbanes-Oxley Act) may have reduced market liquidity or made companies less likely to list securities on US public markets. Now that Dodd-Frank-mandated rulemaking is largely complete—only one fifth of the Act’s mandates have yet to be addressed by a proposed or final rule—it is time for policymakers to pause, to rebalance their approach to financial regulation, and to take stock of which regulations work and which do not.

Featured image credit: United States Capitol Dome and Flag by David Maiolo. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The future of US financial regulatory reform in the Trump era appeared first on OUPblog.

January 30, 2017

How a comet crash on Jupiter may lead us to mine asteroids near Earth

This past December, millions of people around the world gazed in wonder at the rising of the so-called “super moon.” The moon looks super when it turns full on its closest approach to Earth, and variations in its orbit brought it nearer to us than it has been in almost 70 years. Yet even this extra super moon was scarcely bigger than a regular full moon, and few would have noticed the difference without breathless media reports that encouraged them to see it. Those who looked up in awe certainly responded to a genuine natural event, but their culture also conditioned how they understood that event.

Similar relationships have played out before, in ways that have had profound consequences for human history. For centuries, historians argued about which people, or groups of people, have been most responsible for shaping the course of human history. They rarely considered the shifting stage on which the human story plays out: the natural world.

Then, in the 1960s, environmentalist historians pioneered a new kind of history – an “environmental history” – that traces how nature has shaped, and been shaped by, human beings. To explain the course of human history, they argued, we must look not only at human actors but also at a cast of decidedly nonhuman characters, from soils and pathogens to oceanic and atmospheric circulations.

Environmental historians have focused on Earthly environments, and with some justification: the Earth is, of course, the ancient cradle of humanity. Yet our world cannot be so easily distinguished from the much bigger environment beyond its atmosphere, and as the super moon makes clear, parts of that bigger environment can affect us on Earth.

Some of those connections are more obvious than others. Long before humans strengthened the greenhouse effect, for example, changes in Earth’s orbit around the sun caused our climate to fluctuate in ways that shaped our prehistory. The moon has also had a profound impact on the human past, owing not only to its appearance but also its gravitational pull, which causes tides that shaped the fates of coastal communities.

Surprisingly, even changes in environments on distant planets have occasionally had dramatic consequences for human beings on Earth. Take, for example, the natural and cultural drama that accompanied the death of a comet in Jupiter’s atmosphere, in 1994. Early in the twentieth century, Jupiter’s immense gravity pulled that comet into an erratic orbit around the planet. In 1992, the comet passed so close to Jupiter that it was ripped apart by tidal forces. The fragments and dust released by the breakup were together much brighter than the nucleus had been. As they passed out of Jupiter’s glare, they were suddenly easy to spot from Earth.

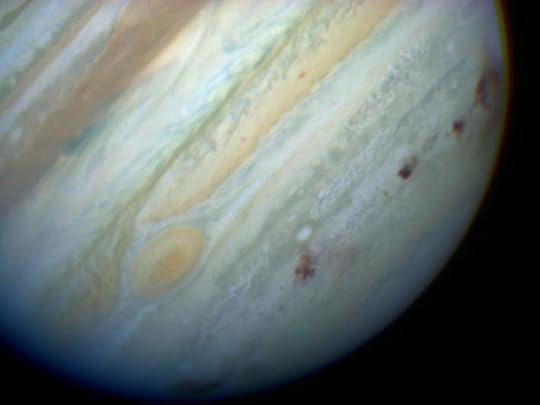

Deep bruises on Jupiter during Impact Week. Brown spots mark impact sites on Jupiter’s southern hemisphere. Image by Hubble Space Telescope Comet Team and NASA. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Deep bruises on Jupiter during Impact Week. Brown spots mark impact sites on Jupiter’s southern hemisphere. Image by Hubble Space Telescope Comet Team and NASA. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.In March 1993, a group of amateur astronomers led by David Levy and partners Carolyn and Eugene Shoemaker spotted a strange smudge near Jupiter. They soon recognized that they had discovered a new comet and called it “Shoemaker-Levy 9,” since it was the ninth they had found together.

The circumstances that led observers on Earth to scan the heavens just as a comet disintegrated and brightened near Jupiter had a deep intellectual and cultural context.

Nineteenth century astronomers had gradually realized that comets and asteroids travelled in huge numbers through the solar system. Twentieth century scientists then found that these objects occasionally crashed into planets, with catastrophic consequences. Meanwhile, popular ideas in western societies that favoured probability and change replaced those that privileged stability and continuity. Cultural and scientific developments together led to a new and precarious vision of humanity’s place in the cosmos. That vision encouraged astronomers to hunt for changes in the cosmos, and it would provoke dramatic popular responses to the changes they discovered.

In May 1993, astronomer Brian Marsden astonished the scientific community by predicting that the comet’s fragments would crash into Jupiter in the following year. It would be the first collision ever observed between known bodies in the solar system. The looming impacts quickly led to unprecedented changes in the culture and practice of astronomy on Earth. Major scientific bodies in the United States coordinated their funding allocations for the first time, and quickly awarded more than two million dollars (adjusted for inflation) to efforts at observing the collisions. Television, radio, and newspaper journalists both encouraged and responded to rising popular interest.

In July 1994, “Impact Week,” as journalists called it, finally arrived. Most scientists had predicted that the impacts would disappoint the general public. They were startled when brilliant fireballs left Earth-sized bruises on the giant planet. Live television broadcasts captured the jarring violence of one cometary fragment after another colliding with Jupiter.

These broadcasts were supplemented by a revolutionary new medium: the Internet. NASA officials had earlier decided to use the Internet to publish real-time images of the collisions. They were astonished when over 2.5 million Internet users accessed these images during Impact Week alone. It was the world’s first major web event. Even for the offline majority, the collisions raised popular interest in the early Internet. Subsequently, NASA officials prioritized their online services over investments in more experimental technologies.

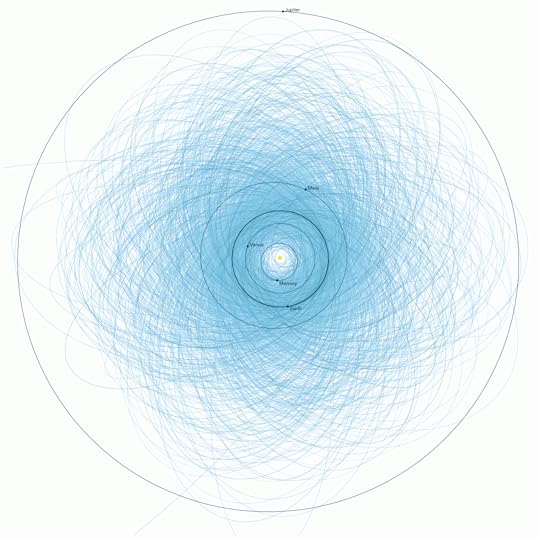

A map showing the orbits of Potentially Hazardous Asteroids at or above 140 meters in diameter, passing within 7.5 million kilometers of Earth’s orbit, discovered as of 2013. Jet Propulsion Laboratory, “Orbits of Potentially Hazardous Asteroids (PHAs).” Public domain via NASA.

A map showing the orbits of Potentially Hazardous Asteroids at or above 140 meters in diameter, passing within 7.5 million kilometers of Earth’s orbit, discovered as of 2013. Jet Propulsion Laboratory, “Orbits of Potentially Hazardous Asteroids (PHAs).” Public domain via NASA.Millions of amateur astronomers also used modest telescopes or binoculars to spot the impact scars as they spread across Jupiter. The bruises humbled and frightened many who saw them. For the first time, politicians, journalists, and ordinary people seriously considered the possibility that a comet or asteroid might someday threaten Earth.

In the following months and years, space agencies around the world responded to political pressure by launching or intensifying programs aimed at finding Earth-approaching comets and asteroids. If a threatening object is detected well before it reaches Earth, it can perhaps be deflected or destroyed. At the very least, the impact zone can be evacuated, although there is little point if the asteroid or comet is big enough.

The renewed quest to defend Earth has led to a detailed map of the space near our planet. That has revealed many thousands of little rocky bodies, none of which will hit Earth any time soon. Most are, however, within reach of unmanned and, before long, manned spacecraft. Companies such as Planetary Resources have recently raised billions of dollars to fund robotic missions that could soon mine these asteroids. Their proponents argue that outsourcing mining to space will support humanity’s colonization of the solar system while reducing its environmental footprint on Earth. Strangely, comet impacts on Jupiter, by galvanizing support on Earth for efforts to scan our corner of the solar system, may soon let companies exploit the environments of nearby asteroids.

The Shoemaker-Levy 9 collisions, like the furor over the recent super moon, reveal that environmental changes in space can affect popular culture on Earth. The collisions, however, also show the extent to which these changes can influence our politics and economy. As we gaze ever deeper into the cosmos, and especially as we begin to colonize it, we will open ourselves to the dynamic influence of ever more distant, and more alien, environments.

Featured image: The shattered comet, a so-called “string of pearls.” Shoemaker-Levy 9 on 1994-05-17 by NASA, ESA, and H. Weaver and E. Smith via the Hubble Space Telescope. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post How a comet crash on Jupiter may lead us to mine asteroids near Earth appeared first on OUPblog.

The Time Machine: an audio guide

The first book H. G. Wells published, The Time Machine, is a scientific romance that helped invent the genre of science fiction and the time travel story. Even before its serialization had finished in the spring of 1895, Wells had been declared “a man of genius,” and the book heralded a fifty year career of a major cultural and political controversialist. This dystopian vision of Darwinian evolution is a sardonic rejection of Victorian ideals of progress and improvement and a detailed satirical commentary on the decadent culture of the 1890’s.

Tune in to our podcast to listen to Roger Luckhurst, editor of the Oxford World’s Classics edition, discuss the plot and themes of The Time Machine, as well as Wells’ influences and impact on science fiction.

Featured image credit: “Banner, Header, time, Ancient Clock” by PeteLinforth. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post The Time Machine: an audio guide appeared first on OUPblog.

Do school food programs improve child dietary quality?

Each school day, more than 30 million children in the United States receive a meal through the National School Lunch Program (NSLP); many of those students also rely on the School Breakfast Program (SBP) for their morning-time meal. These two long-standing federally subsidized meal programs were enacted on the premise of providing school children with “adequate nutrition” and “an adequate supply of food.” As the second largest food assistance program in the US, cash payments to participating schools were over $16 billion in 2014, or about 10% of the US Department of Agriculture’s total spending.

But, as the adage goes, “There ain’t no such thing as a free lunch”–participating schools must meet minimal nutritional standards in order to receive federal cash assistance. Over the past 70 years, school meal standards have become increasingly focused on raising the quality of school food rather than simply supplying food. But exactly how does the quality of a school meal compare to a brown-bag meal from home? Turns out, the answer isn’t as simple as comparing the average school lunch to the average sack lunch; we must dig deeper, far below and above the average child, where very-low and very-high quality diets exist.

When I began researching this topic, the literature was a mixed bag with regards to how school meals stacked up against a home-prepared meal: some found a negative effect within the general population, others a positive effect for low-income children, and yet others found no impact at all. There are a variety of reasons why one might expect conflicting results, such as when and where the data was collected and how exactly one measures diet quality, but the one glaring oversight to me was that all studies focused on the average impact. This one detail is particularly important in the context of school meals when we consider the vast heterogeneity in the quality of US children’s at-home diets as compared to the rather homogenous, federally-regulated school meal.

As an example, consider a child who typically consumes a low-quality diet, possibly due to parental or environmental factors. It is reasonable to believe this child may benefit from a school meal. On the other hand, a child prone to a high-quality diet may be impacted negatively when switching from a sack lunch to a school meal. In fact, on average these countervailing impacts can wash out, leaving policymakers with the conclusion that school meal programs aren’t performing as we expect them to.

The above line of thinking led me to reframe the policy question at hand and ask, how do school meal programs impact children prone to low-quality diets separately from those prone to high-quality diets? Moreover, rather than take a one-at-a-time approach to analyzing single nutrients or food groups, I took a holistic approach using a scoring system developed and validated by nutritionists, the Health Eating Index (HEI). The HEI is an algorithm that gives a score from 0 to 100 based on all foods consumed, in this case over two nonconsecutive 24-hour periods in a nationally representative dataset collected over 2005 to 2010.

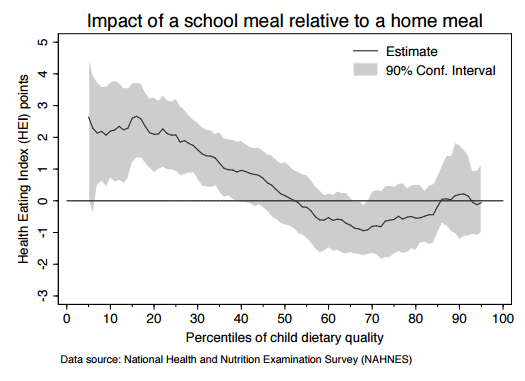

The results from my analysis are best shown in the figure below. The x-axis represents an ordering of children from the lowest quality diet to the highest quality diet. The y-axis plots out the impact of substituting a home-prepared meal for a school meal (about 33% of daily calories). For one-half of all children with relatively low-quality diets (i.e., below the 50th percentile on the x-axis) a school meal boosts diet quality; for the other half of all children we see negative and insignificant impacts.

Impact of a school meal relative to a home meal by Travis A. Smith. Used with permission.

Impact of a school meal relative to a home meal by Travis A. Smith. Used with permission.To further give perspective, consider the bottom quartile below the 25th percentile mark. Here, we see substituting a home-prepared meal for a school meal boosts dietary quality by over 2 HEI points. This is roughly 2.5 times higher than the average impact. Further, in results not show here, the quality of the at-home diet in the bottom quartile is no different than the quality of meals consumed at full-service and fast-food restaurants. Put simply, a school meal is the highest quality food consumed by children that rank the lowest on the diet quality spectrum.

How “large” is a one-point increase in HEI? Several medical studies have tracked adults over time, monitoring their HEI scores and recording adverse health outcomes. One study finds a 7% decrease in risk for any major chronic disease when moving from the first quintile (i.e., bottom 20%) to the second quintile. A quick back-of-the-envelope calculation implies a one-point increase in HEI equates to a nearly 1% decrease in risk. It remains to be studied how school meals impact diets in adulthood, but when we consider the two-point increase is daily and early on in life, the impact could be substantial.

These findings demonstrate the importance of school meal programs, especially for those children who need them the most. School food programs have undergone many changes since the 1960s, and there is good reason to believe they will continue to reform. As the new administration examines the existing school meal programs, they should consider the heterogeneous nature of the policy effects.

Featured image credit: Healthy choices of fresh fruit, salads and vegetables at Washington-Lee High School in Arlington, Virginia for lunch service on Wednesday, October 19, 2011 by U.S. Department of Agriculture. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Do school food programs improve child dietary quality? appeared first on OUPblog.

Impact of domestic courts’ decisions on international law

The Distomo cases, the Urgenda Foundation v The Netherlands case, the Alien Tort Statute cases, and the Israeli targeted killings cases are among the most fascinating domestic cases on international law. But why should we care about domestic courts’ interpretation and application of international law? And what role do domestic courts play in crystallizing the general principles of international law?

In practice, a vast amount of international law is actually implemented and interpreted by domestic courts. These courts are increasingly engaged with international law across a diverse array of areas, such as statehood; immunities; human rights and humanitarian law; environmental issues; refugee law; and the use of force and non-intervention.

However, the way that international law is interpreted, applied, and received at the national level differs widely from one state to another. The significance of domestic court decisions that deal with international law not only lies in the potential authoritative determinations of international law, but also in what we can learn from the distinct approaches taken by different domestic legal systems. Sometimes, a domestic judge’s refusal to engage with international law can say as much as judgments that go to great length to correctly apply international law.

Domestic courts decisions from the world’s richest states, including the United Kingdom and United States, are relatively easy to find but judgments from developing countries are often difficult to uncover and put into context. The result is that contributions by developing country courts are often overlooked in international law research.

Back in September, we celebrated the tenth anniversary of Oxford Reports on International Law in Domestic Courts (ILDC), the first module launched of the Oxford Reports on International Law (ORIL) service.

To mark ILDC’s tenth birthday, we sat down with Editors-in-Chief André Nollkaemper and August Reinisch, to discuss the most fascinating domestic cases on international law, and discover the huge impact that domestic courts’ decisions have on the rule of international law in general.

In this video ILDC Editors-in-Chief André Nollkaemper and August Reinisch discuss four of the most important domestic cases on international law: The Distomo cases, the Urgenda Foundation v The Netherlands case, the Alien Tort Statute cases, and the Israeli targeted killings cases.

In this video ILDC Editors-in-Chief André Nollkaemper and August Reinisch talk about the impact that domestic courts’ decisions have on international law, why we should care about domestic courts’ interpretation and application of international law, and the role that domestic courts play in crystallizing general principles of international law.

Featured image credit: Image created for Oxford University Press. Do not re-use without permission.

The post Impact of domestic courts’ decisions on international law appeared first on OUPblog.

January 29, 2017

Studying invasion biology with next-generation sequencing

The globe has never been more connected. The anthropocene has seen the world become entwined in a comprehensive web of trade and transport. Within this extensive interconnectivity, humans are altering the composition of the earth’s biota, providing vehicles for organisms to hitchhike around the planet. Organisms that before were restricted to areas by geographical barriers or limited natural dispersal capability are able to establish in novel areas beyond their native range limits, where they may be free from the pressures that restrict them in their native range. If they do well and become self-sufficient in this novel area, they can spread and proceed to alter the local area potentially causing serious ecological damage. Such organisms are termed invasive species, and biological invasions are having such an impact on biodiversity that there are now few topics more critical to contemporary biodiversity and ecology. The field of invasion biology has opened up to study these species, and fortunately, it is equipped with a potent tool: the genetic code.

Deciphering the genome (the complete genetic code) of any species can lead to a wealth of knowledge. By analyzing an invasive species’ DNA, an invasion geneticist may untangle, among other things, its origin, its invasion history, and any potential hybridization with native species. These all provide vital tools when informing management efforts tackling biological invasions. The main problem with such an analysis was that, until recently, DNA sequencing (reading the genetic order of the nucleotide bases, i.e. adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine) was an expensive and time-consuming process, especially when analyzing a great number of individuals.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms are able to outperform previous sequencing techniques in output by 100–100,000 times.

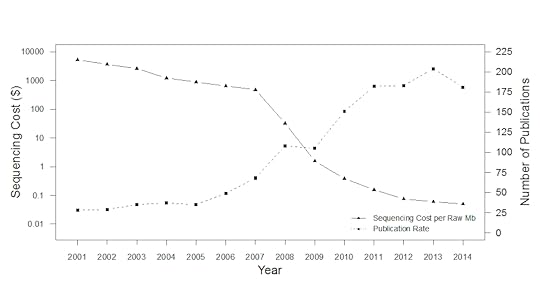

In recent years, a new form of DNA sequencing has entered the market. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms are able to outperform previous sequencing techniques in output by 100–100,000 times. This is accomplished by a more efficient, parallelised sequencing design, which has considerably decreased the price of DNA sequencing. Indeed, from 2007 onwards, the associated costs significantly decreased as NGS platforms became more commonly utilised. Lower costs facilitated the accessibility of DNA sequencing, which in turn catalysed the number of invasion biology studies that included a focus on genetics. The influence of NGS technology on DNA sequencing, and the benefits entailed, is strong enough that it is possible to pinpoint exactly when NGS technologies were adopted by the biological community by tracking the historical price of DNA sequencing (Figure 1).

Figure 1. DNA sequencing costs and publication rate of invasion biology studies that included a focus on genetics from 2001-2014. Graph created by the authors and used with permission.

Figure 1. DNA sequencing costs and publication rate of invasion biology studies that included a focus on genetics from 2001-2014. Graph created by the authors and used with permission.This ability to generate orders of magnitude more data from NGS technology leads to some exciting prospects for invasion biology, and has turned invasion genetics into a more comprehensive discipline. Firstly, it makes the assembly of full genomes more accessible. This means that an added focus can be placed on the DNA analysis of non-model organisms, for which genomes can be generated and assembled with much more ease than in the past. The amount of data generated also allows new markers to be used when analysing the DNA of invasive species. NGS allows hundreds of thousands of genomic sites to be interrogated simultaneously, enabling thousands of variable sites to be identified between individuals, giving a much deeper and broader survey of the species than was previously possible.

The higher number of markers afforded by NGS enables a more comprehensive DNA analysis to be performed, as more information from the genome is available. For example, it’s possible to detect much finer-scale population structure, and a more robust picture of invasion routes can be built, because more genomic information is available to feed into the analysis. Further analyses are also possible with an NGS approach. The influence of evolution can be investigated to a narrower degree than with techniques that utilize fewer markers, and it’s much more convenient to examine how environmental conditions cause invasive species to switch on and off particular genes.

Despite the increase in genetic studies however, NGS technology is still underutilised on a large-scale within the field of invasion biology. Moreover, when NGS is applied in invasive biology most studies take an introductory or descriptive role, rather than a more thorough analysis of specific questions. We expect that this currently underutilised resource will be adopted en masse, leading to much more in-depth genomic analyses of many invasive species, addressing a range of evolutionary and ecological questions. This will drive the further use of genetic and genomic studies in invasive species, assisting invasion biologists in understanding and mitigating this major biodiversity conservation problem.

Featured image credit: Dna by PublicDomainPictures. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Studying invasion biology with next-generation sequencing appeared first on OUPblog.

The humanities in Trump’s Gotham City

On 8 November 2017 the American political system threw up from its depths a creature wholly unrecognizable to those of us born in the West since 1945. Most of us who teach the humanities at any level have felt, since 8 November, that we have been reduced to the level of bit players in a Batman movie – we are out on the streets of Gotham City, with the leering Joker on the loose; we’re passively waiting, with trepidation, as to what on earth the Joker’s next lurid stunt will be. The only difference between us and the movies is that Batman is nowhere to be seen. Neither can we see any other speaker that will command the attention of Joker or his Penguin-like henchmen. When we most need to speak, we find ourselves instead trying to get the hang of the Joker’s strange, previously unheard, lingo of indecency and mockery. The entire operation of the humanities, with its ideals of depth, meaning, evidence, expertise, and passionate, life enhancing connection, has been stymied by The Joker. We’re tongue tied.

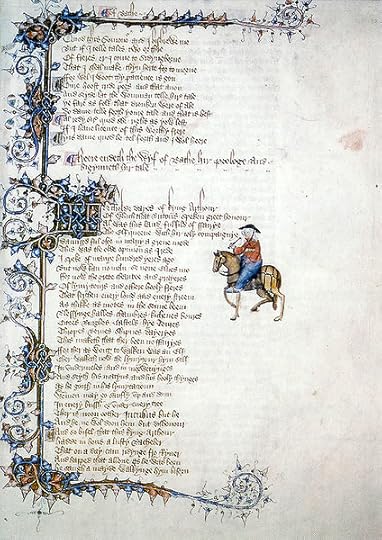

Or are we? Two days after the election, I found myself in front of 16 undergraduates, ready to discuss Chaucer’s Wife of Bath’s Tale, written in the 1390s. As I started, the mood of the class gave me some inkling of what it was like to be in one of outer space’s black holes. It was glacial, silent, and somber beyond experience. The discussion that followed was, however, unforgettable and inspiring. It persuaded me that humanists not only have a voice; nay, more, much more: the Humanities have suddenly become the central focus of a counter culture.

The Wife of Bath’s Tale is about two intimately related phenomena: misogyny and control of the media. The Wife’s fifth husband takes pleasure in reading from a huge, expensive volume of anti-feminist writing every night before bed. The Wife, Alyson, is understandably irked by her husband’s complacent, misogynistic reading. So one evening, she just can’t put up with the spectacle anymore; she jumps up and tears a great chunk of material out from the book of wicked wives.

Before she recounts the tearing episode, the Wife targets the media issues at stake, by delivering a sharp-eyed critique of media control by men. How come, she asks, there’s so much narrative devoted to portrayal of wicked wives? Is it because women are no good? Not at all, Alyson continues; it’s because men produced the narratives in the first place. She cites the fable of the lion who finds himself in a royal palace looking at frescoes of the king hunting a lion. In every painted scene, the king lords it over a cowering lion, about to become the king’s victim. The tourist lion is a sharp art critic: “Who,” he skeptically asks, “peyntede the leon, tel me who?” Whoever controls the means of cultural production, imply both lion and Alyson, controls the culture. You might lose fights with lions, but that’s irrelevant if you control the representation of lion hunts. Losers can win if they know how to manipulate media.

Opening page of The Wife of Bath’s Prologue Tale, from the Ellesmere manuscript of Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales by unknown. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Opening page of The Wife of Bath’s Prologue Tale, from the Ellesmere manuscript of Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales by unknown. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.The biggest issue of the recent presidential election for my undergraduates, both men and women, was the President-elect’s unequivocal indecency, particularly his gross indecency towards women. His triumphant election was a threat for every young woman in my class, since they knew that national tone and practice towards women was about to change for the very much worse. It was also deeply depressing for every young man, since the Joker and his surrogate henchmen had cast the charges of gross indecency aside by declaring that talk of that kind (the-published-video-on-the-bus kind) was the way all men talked “in the locker room.” The Joker and his henchmen cast a shadow of suspicion on every man.

So the Wife of Bath’s Tale was in fact strikingly pertinent to the issues pressing in upon my class from outside the classroom, in the wake of the election.

The discussion began by denying that pertinence. Of course I avoided any explicit reference to the election, or any indication of my own views about it. No explicit politics, and no T-word, but it was impossible not to acknowledge the mood in the room.

So I turn to an African-American student to get the ball rolling. “How are you feeling?,” I ask (instead of my usual starter of “What’s most interesting to you about this text?”). “I can’t take this text seriously,” is the reply; “it just hasn’t got any traction on what’s going on.” “Ok,” say I, and turn to another student to get us going. This student focuses immediately on the fact that the Wife of Bath’s Tale might pretend to promote women, and might pretend to focus on issues of media control, but hey, this text was written by a man; and a woman whose literary criticism consists of tearing pages from a book might in fact confirm those anti-feminist stereotypes. What looks like a pro-feminist text is instead a more subtly insidious anti-feminist text. Not so, says another student.

So we’re away, with a superb, focused, high-level, three-cornered discussion of feminist and media issues in the late fourteenth-century text. Twenty minutes in, and the African-American student puts up her hand to speak. She delivers a passionately felt, beautifully targeted case for reading the Wife as voicing what she can, how she can, with the materials available. Now everyone in the class understands that maybe the African-American student knows of what she speaks; the level of conversation rises a notch from its already Olympian height.

With my student’s brilliant intervention, I suddenly understand something, too: that my class is modelling the work of the humanities, repurposing texts from the thesaurus of the past to give voice and direction in the present. My own mental tongue is untied: this, I say to myself, is how the humanities have always worked, but now it means something different. Now we’re a counter culture. Now we offer a crystal clear alternative to the know-nothing, evidence-dismissive, derisive, indecent culture of the Joker. Our way of meditating, our mode of dialogue, our way of projecting into the future (respectively, immersive, respectful, reparative) offers an alternative to what’s being thrust from Washington.

I always devote the last class of my course to recitation. Each of us, myself included, stands up and recites a poem from the course that we’ve learned by heart. The African American student recited some lines from a very beautiful ninth-century elegy, The Wanderer. Her performance stilled the class; one could have heard a pin drop. I’ll never forget the confluence of ninth- and twenty-first-century exile. These are the lines my gifted student cited:

Often alone, always at daybreak

I must lament my cares; not one remains alive

to whom I could utter the thoughts in my heart,

tell him my sorrows. In truth, I know that

for any eorl an excellent virtue

is to lock tight the treasure chest

within one’s heart, howsoever he may think.

A downcast heart won’t defy destiny,

nor the sad spirit give sustenance.

And therefore those who thirst for fame

often bind fast their breast chamber.

So I must hold in the thoughts of my heart—

though often wretched, bereft of my homeland,

far from kinfolk— bind them with fetters.

It is the worst of times; for the Humanities, it may be the best of times.

Featured Image credit: Donald Trump speaking at CPAC 2015 by Gage Skidmore. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The humanities in Trump’s Gotham City appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers