Oxford University Press's Blog, page 416

January 21, 2017

The year Bob Dylan was born again: a timeline

The following is an excerpt from Light Come Shining by Andew McCarron

On November 17, 1978, while playing a gig in San Diego, an audience member apparently threw a small silver cross onto the stage, and [Bob] Dylan felt impelled to pick it up and put it into his pocket. The following night, in Tucson, Arizona, he was feeling even worse and reached into his pocket, pulled out the cross, and put it on. That night, while stuck inside his hotel room, he apparently experienced the overwhelming presence of Jesus whose power and majesty he’d heard about through his girlfriends Helena Springs and Mary Alice Artes, in addition to his recently converted band mates Steven Soles, David Mansfield, and T- Bone Burrnett. It was Artes, though, who seems to have influenced him the most. She had recommitted herself to the Christianity of her youth through a Church in Tarzana, California, called the Vineyard Christian Fellowship, which Dylan soon joined. Founded by pastor Ken Gulliksen in 1974, it was a small but fast-growing evangelical church that emphasized redemption over judgment. Artes’s recommitment impelled her to live a scripturally pure life by moving out on Dylan, with whom she was living at the time. Through her prompting, two Vineyard pastors, Larry Myers and Paul Emond, were dispatched to Dylan’s home and ministered to him. He apparently received the Lord that day.

Although Dylan’s new faith was a syncretistic amalgam that incorporated elements of the Jews- for- Jesus movement, Southern Californian New Age, and old fashion fire-and-brimstone millennialism, there was no doubt Jesus was smack dab in the middle of it. “Jesus did appear to me as King of Kings, and Lord of Lords …,” he’d later explain. “I believe every knee shall bow one day, and He did die on the cross for all mankind.”

January 1980

In late January 1980, Dylan’s gospel tour played three nights at the Uptown Theater in Kansas City, Missouri. At some point during these shows, Paul Vitello, a young reporter for the Kansas City Times, managed to coax Dylan into discussing his conversion experience. The brief reflection Dylan shared was a perfect encapsulation of the destiny script. “Let’s just say I had a knee-buckling experience,” he explained. He then proceeded to touch upon the disenchantment of his life leading up to his encounter with Jesus. “Music wasn’t like it used to be. We were filling halls, but I used to walk out on the street afterward and look up in the sky and know there was something else. … A lot of people have died along the way—the Janices and the Jimmys. … People get cynical, or comfortable in their own minds, and that makes you die too, but God has chosen to revive me.” This description contains a familiar constellation of experiences. The sensation of feeling existentially adrift (“I used to walk out on the street afterward and look up in the sky and know there was something else”) intensifies a vague but persistent threat of annihilation (“A lot of people have died along the way”), a threat that Dylan is redeemed from (“but God has chosen to revive me”) through a wholehearted investment in “tradition”—in this case being Christianity—or more specifically, in the reality of Jesus, which Dylan substantiated by appealing to the Bible as a source of moral guidance and theological truth.

“Jesus put his hand on me. It was a physical thing. I felt it. I felt it all over me. I felt my whole body tremble. The glory of the lord knocked me down and picked me up.”

“People who believe in the coming of the Messiah live their lives right now, as if He was here,” he’d explain in 1985. “That’s my idea of it, anyway. I know people are going to say to themselves, ‘What the fuck is this guy talking about?’ but it’s all there in black and white, the written and unwritten word. I don’t have to defend this. The scriptures back me up.”

May 1980

The first journalist to interview Dylan at length about his conversion was Karen Hughes, a writer for The Dominion, which was Wellington, New Zealand’s daily newspaper. Unlike the off-the- cuff comments he made to Paul Vitello five months earlier, Dylan didn’t say much to Hughes about his pre-conversion state of mind. Instead, he used vivid language to describe the rawness of the transformation. “Being born again is a hard thing,” he said. “You ever seen a mother give birth to a child? Well it’s painful. We don’t like to lose those old attitudes and hang-ups.”

The physical language he used to characterize the change was reminiscent of his description of his motorcycle crack-up twelve years earlier: “Jesus put his hand on me. It was a physical thing. I felt it. I felt it all over me. I felt my whole body tremble. The glory of the lord knocked me down and picked me up.” Compare this language to the description he shared with Sam Shepard in A Short Life of Trouble (1987): “I went blind for a second and I kind of panicked or something, I stomped down on the brake and the rear wheel locked up on me and I went flyin’.”

Another familiar trope that runs across both events is the new sense of self that the change gradually engenders. “Conversion takes time because you have to learn to crawl before you can walk,” he told Hughes. “You have to learn to drink milk before you can eat meat. You’re reborn, but like a baby. A baby doesn’t know anything about this world and that’s what it’s like when you’re reborn. You’re a stranger. You have to learn all over again. God will show you what you need to know.” It bears mentioning that much of this language is paraphrased from the Pauline Epistles, which Dylan quoted from fairly regularly following his conversion. In the third chapter of Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians, Paul likens the wayward Corinthians to babies who must learn to drink milk before they can eat meat: “I have fed you with milk, and not with meat: for hitherto ye were not able to bear it, neither yet now are ye able” (1 Corinthians 3:2). Like many of the Born Again Christians studied by anthropologist Peter Stromberg in his book Language and Self-Transformation (1993), the canonical language of fundamentalist Christianity is grafted into the converts’ self-expressions, thus inscribing their fears and hopes with new meanings. In Dylan’s particular case, though, the canonical language of Christianity was joined to a preexisting schema of death and rebirth that can be traced back to his teenage years. The presence of a Messiah figure prompting the change was new, however.

Dylan alluded to a feeling of destiny behind Jesus’ call:

I guess He’s always been calling me. … Of course, how would I have ever known that? That it was Jesus calling me. I always thought it was some voice that would be more identifiable. But Christ is calling everybody; we just turn him off. We just don’t want to hear. We think he’s gonna make our lives miser- able, you know what I mean. We think he’s gonna make us do things we don’t want to do. Or keep us from doing things we want to do.

But God’s got his own purpose and time for everything. He knew when I would respond to his call.

November 1980

The third and final time Dylan discussed his conversion with a journalist was in November 1980 with The Los Angeles Times music journalist Robert Hilburn. As he had with Karen Hughes, he discussed the physicality of his experience in Tucson, describing a “vision and feeling” that moved the hotel room and that “couldn’t have been anybody but Jesus.” In an interesting revision that may have been a conscious attempt to counteract the generally bad rap that his con- version had been receiving in the press, Dylan claimed that he was neither “down and out,” “miserable,” nor “old and withering away” leading up to his acceptance of Jesus, but, to the contrary, “relatively content.” However, his remarks on stage in San Diego in 1979, to Paul Vitello in 1980, and the claims of his biographers, all paint a somewhat bleaker portrait of his state of mind.

Through the prompting of “a very close friend” (again, presumably Mary Alice Artes), he accepted Jesus into his life—and then, despite some initial resistance, attended most of a three- month Bible course at the Vineyard Christian Fellowship in Reseda, California, that changed his attitude toward the world. It was during this course that Dylan intensified his relationship to Biblical tradition. “I had always read the Bible,” he explained, “but only looked at it as literature. I was never really instructed in it in a way that was meaningful to me.” Much as he raided Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music and other sources of American traditional music at Big Pink, he now searched through the Bible, earmarking pages, underlining key verses, and subsuming Biblical lingo into his song lyrics and everyday vernacular.

He took particular interest in the Book of Revelation, which seems to confirm Howard Alk’s notion that death and destruc- tion were indeed on his mind. When asked by Hilburn to assess whether his conversion made him feel or act differently, Dylan made an oblique reference to things that he was saying on stage be- tween songs the previous year. “I was saying stuff I figured people needed to know. I thought I was giving people an idea of what was behind the songs.” What he was doing was regaling his audiences with fire-and-brimstone prognostications that the end of history was fast approaching, which necessitated immediate repentance.

The brush with death that jolted him after his motorcycle accident in ‘66 had now morphed in scope, becoming more broadly social in focus. The feelings of estrangement and anxiety that rendered him susceptible to death were no longer specific to him, but plagued the entirety of America—and beyond! Accordingly, Dylan made a reference to the “sickness” of society to Hilburn. “When I walk around some of the towns we go, however, I’m totally convinced that people need Jesus,” he said.

Featured image: Bob Dylan and Joan Baez, via Wikipedia, CC0 Public Domain.

The post The year Bob Dylan was born again: a timeline appeared first on OUPblog.

January 20, 2017

What kind of cheese are you?

The discovery of cheese predates recorded history. Although the earliest evidence of cheesemaking can be traced back to 5,500 BCE, historians theorize that cheese was originally discovered accidentally: it’s probable that cheesemaking first occurred inside animals organs used for storing milk.

History does trace back to the world’s first cheesemaking factory, which opened in Switzerland in 1815. The industrialization of cheesemaking soared as the United States began opening factories throughout the country, leading to the large-scale production of cheese globally. Since then, cheese has been, and continues to be, a cultural staple around the world–with a wide selection available, from cheddar to gouda to camembert.

To celebrate Cheese Lovers Day, Oxford University Press wants to know: what kind of cheese are you? Referencing The Oxford Companion to Cheese, we’ve put together a quiz to help you find out.

Featured image credit: untitled by fas. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post What kind of cheese are you? appeared first on OUPblog.

The centennial of mambo king Pérez Prado

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, a new, fast, and instantly appealing music and dance style swept across the globe: the mambo. The man behind the new sensation was the Cuban pianist, composer, bandleader, and showman Dámaso Pérez Prado. December 2016 we celebrate the centennial of his birth in the city of Matanzas, 100 miles east of Cuba’s capital in Havana.

Mambo fever started with unusually named tunes like “Mambo Number 5,” (rendered in the United States as “Mambo Jambo”), “Mambo Number 8,” and other instrumental compositions with similar nomenclature that moved to the top of the charts in the United States. Meanwhile in Mexico (Prado’s home base at the time), Cuba, and the rest of the Spanish-speaking world, other mambos that included lyrics from the Afro-Cuban traditions became regional favorites. Prado’s choice of the brilliant Cuban vocalist, Benny Moré, helped popularize tunes like “Babarabatiri” and “Anabacoa.” Always attuned to the visual and dance aspects of a new style, Prado featured, performances by the talented and famous Cuban women dancers called rumberas or even exóticas (such as Ninón Sevilla and María Antonieta Pons), both in live shows or in the many Mexican movies in which he participated.

Beyond his mambo tunes, Pérez Prado had an obvious knack for composing and orchestrating other material that became immediately popular around the world. He appropriated in his own particular manner an early 1950s music “craze,” the cha-cha-cha, and produced a novel arrangement of a French tune, “Cherry Pink and Apple Blossom White,” which became the number one hit on US music charts for 10 consecutive months in 1955. No sooner had the rock-and-roll revolution taken over in the United States than, in 1958 when Prado released “Patricia,” an almost indefinable slow mambo-rock featuring an organ as the lead instrument, for the first time in American pop music. It too reached the number one spot on the pop music charts, and it became something of a classic in American music. Cinema also came to pay respects: Swedish leading screen actress Anita Ekberg danced to “Patricia” in Federico Fellini’s memorable La Dolce Vita.

Prado’s music, in all its expressions, whether commercial or concertos, mambos, or other styles, had the evident qualities of style and rhythm. Everything he composed, everything he did, was full of rhythm.

Often accused of producing nothing except commercial music, Prado had another side to his musical inclinations, composing in the 1950s and 1960s three instrumental concerts. The 1954 “Voodoo Suite” was a four-movement tone poem, a fusion that combined jazz and Afro-Cuban themes. The seven-movement “Exotic Suite of the Americas,” recorded in New York in 1962, did not achieve much recognition in the United States. However, that was not the case in Cuba because the leading documentary filmmaker Santiago Alvarez used the first movement as a theme for the soundtrack of the daily official Cuban government newscast of 16 October 1967, that reported the death of Ernesto “Che” Guevara in Bolivia. Since then, the sound of that movement of the “Exotic Suite,” repeated year after year when Guevara’s death is commemorated, it has become synonymous in the average Cuban’s sonic imaginary with the image of the fallen guerrilla fighter. In 1965, Prado composed and performed live his third concerto, the percussion feast “Concierto para bongo.” As with his earlier hits, it’s difficult to put this music squarely in a box. But again, it made its mark in a film, serving as background music in Pedro Almodovar’s Kiki.

Prado’s star faded in the United States by the early 1960s, but not so in the rest of the world, especially in South America, Europe, and Japan, where he toured more than 20 times in the 1960s and 1970s. And in 1965 Pérez Prado launched another dance rhythm, the dengue, which turned into a huge success in his native Cuba and became emblematic of the 1966 Havana Carnival.

Prado’s music, in all its expressions, whether commercial or concertos, mambos, or other styles, had the evident qualities of style and rhythm. Everything he composed, everything he did, was full of rhythm. The mambo was of course his most memorable accomplishment. As always seems to happen with a successful style, several artists claimed that “they,” not Pérez Prado, had invented the mambo. After his death in 1984, a number of them, here and there, were anointed, or anointed themselves, as the mambo “kings.” My considered opinion is the same as the late, great New York musician Tito Puente when he stated, “For me, like for all musicians in New York and the world, the only mambo king ever was Pérez Prado.”

Featured image credit: “Southernmost Point” by FitzFox. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Pixabay.

The post The centennial of mambo king Pérez Prado appeared first on OUPblog.

What does Trump healthcare mean for consumer choice?

During his campaign, Donald Trump repeatedly called for the repeal of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). With the specifics of his replacement plan unknown, it’s clear that the ambiguity is making many in the healthcare industry very nervous. Ted Shaw, president and CEO of Texas Hospital Association, stated, “Any replacement [of the ACA] needs to ensure that patients can get the care they need and providers are fairly paid for services provided.” Similarly, Marilyn Tavenner, president and chief executive of America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP), released a statement requesting that the government support stable health insurance markets by encouraging young, healthy individuals to sign up for coverage, maintaining subsidies for low- and moderate-income individuals to purchase insurance, and offering financial support to health plans that enroll high-cost individuals.

The day after the election, more than 100,000 Americans rushed to purchase health insurance under the Affordable Care Act, highlighting that many consumers are just as nervous as big industry players about what impending changes might mean for them. As provider organizations and insurers scrambled to protect their interests, a common, impartial voice for healthcare consumers came from the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network, which implored Congress to consider patient protections, especially for those with pre-existing conditions.

Although President Trump has advocated for a more consumer-driven healthcare market, it is wrong to contend that consumerism in healthcare is entirely a right-wing idea. Both left and right-wing policies have created larger roles for consumers in the healthcare marketplace – albeit, in different ways. The ACA was arguably the largest driver of a consumer revolution in health insurance; it opened up a mass market of coverage sold directly to individuals. Furthermore, more than 90% of marketplace enrollees are enrolled in high deductible health plans, which typically increase the amount of out-of-pocket spending consumers are responsible for. As a result, consumers have more choice and greater financial stakes in the market than they had previously.

90% of marketplace enrollees are enrolled in high deductible health plans…

The ACA has given 22 million people coverage, including more than ten million who have received coverage through individual plans on marketplaces. The uninsured rate went down from 16.3% in 2010 to 8.6% in the first quarter of 2016. The ACA expanded options for those with pre-existing conditions, who often had little choice before. What’s more, the employer-sponsored market remained stable, calming initial fears that employers would reduce coverage and push employees onto the exchanges. And while overall consumer opinions on the ACA often parallel political party preferences, many of its individual provisions receive bi-partisan support.

However, unforeseen challenges have negatively impacted consumer choice. Consumers in some states found that the plans offered under the ACA had narrower networks, and their physicians weren’t necessarily included. Furthermore, in 2016, some of the largest insurers pulled out of the state marketplaces after sustaining substantial financial losses, meaning that consumers had fewer plans to choose from. Many of the remaining plans have raised their premiums. Even before Aetna’s decision in August to discontinue marketplace plans in 11 of the 15 states where it operated, the Kaiser Family Foundation projected that there would be 5.8 plans to choose from per state in 2017 (this compared to 6.9 in 2015 and 6.5 in 2016). In August, the New York Times reported that 17% of Americans eligible for a marketplace plan would only have one insurer to choose from for 2017.

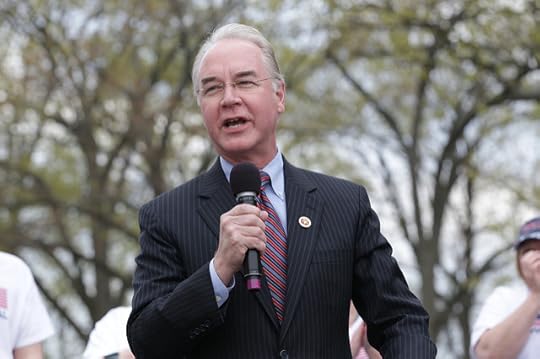

Image credit: Tom Price speaking, Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Georgia’s 6th district by Mark Taylor. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: Tom Price speaking, Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Georgia’s 6th district by Mark Taylor. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.So, what will happen to consumer choice during a Trump presidency? Because Republicans lack a supermajority in the Senate, it’s unlikely that they will be able to repeal the entire ACA. Trump has committed to keep two popular ACA provisions: one that allows children to retain coverage through their parents’ plans until age 26 and another that requires insurers to cover individuals with pre-existing medical conditions. They’ll also need to ensure that the employer-sponsored market, which provides insurance to 177 million people, remains stable and competitive.

However, Republicans can use reconciliation, a budget process, to eliminate several other ACA provisions. Tom Price, who received the nomination for Health and Human Services secretary, introduced a bill last year as a member of Congress to replace the ACA. The proposed measures from Price and Trump promise to expand consumer choice, but may limit it as well:

Potential to expand consumer choice:

Improving price transparency: Trump has advocated for improved price transparency from provider organizations. If successful, this would undoubtedly aid consumers in comparing healthcare options.

Selling insurance across state lines: Trump has advocated for allowing the sale of health insurance across state lines (existing laws prohibit it), which would likely increase the number of available options. However, some skeptics have pointed out that out-of-state plans may struggle to meet state regulations, as well as compile recruit physician networks.

Expanding use of Health Savings Accounts (HSAs): HSAs, tax-advantaged savings accounts for medical expenses, are currently only offered to individuals with high-deductible health plans. Trump would give a greater number of consumers the option of tax-advantaged saving for future health expenses. However, these accounts would more likely benefit the wealthy and educated.

Potential to limit consumer choice:

Trump has committed to keep two popular ACA provisions.

Reducing Medicaid availability: The ACA expanded Medicaid coverage for nearly all low-income individuals with incomes at or below 138% of the poverty line. Trump has instead advocated block grants to states, letting them administer Medicaid as each sees fit. This might decrease federal funding, and ultimately, enrollment numbers, reducing access and options for many needy people.

Eliminating the individual mandate: If Trump removes the individual mandate (which forces taxpayers to prove they have health insurance), it’s possible that many healthy people will choose not to buy insurance. Insurers would be left with riskier pools of sicker individuals who would have to pay higher premiums.

Losing insurance subsidies: If the replacement plan reduces subsidies, fewer affordable choices will be available to consumers seeking to purchase individual insurance plans.

In conclusion, it seems likely that those consumers who already enjoy the luxury of choice in the health insurance market will see their choices and therefore competitive pricing improve. But many consumers who have enjoyed greater choice thanks to the ACA may see their access to affordable health insurance choices dwindle rather than expand. The political downside of upending consumers who have benefited from the ACA may, however, limit the numbers who in the end will be disadvantaged by the determination to repeal and replace Obamacare, if only in name.

Featured image credit: Donald Trump by Marc Nozell. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post What does Trump healthcare mean for consumer choice? appeared first on OUPblog.

Learning from disaster

As part of our 50th anniversary issue of the OHR, Abigail Perkiss explored the impact of oral history in the aftermath of a Hurricane Sandy in her article Staring Out to Sea and the Transformative Power of Oral History for Undergraduate Interviewers. The article is a timely look at how doing and presenting oral history changes the way practitioners interact with both their interviewees and the broader world. Below, we hear more about how the project moved from recording to presenting in only a few months and how Perkiss helped to foster commitment and transformation. If you are interested in contributing your own pedagogical experiences and insights email our blog editor, Andrew Shaffer, or Abigail Perkiss, Pedagogy Editor at the Review.

The article shows how the Staring Out To Sea project transformed the students involved. Have you seen similar effects with other projects or do you think this was unique to the traumatic beginnings or the intimate connections the students shared to the events?

I’ve used oral history in my teaching before, but the semester during which we developed Staring out to Sea was the first time I’d ever taught a seminar specifically focused around oral history, and specifically centered on the development of one collaborative project. So, it’s hard to know what made the difference – was it spending the entire term concentrating on oral history? Was it the nature of the work and the immediacy of the experience for the students? Was it the project-based approach that allowed the students to feel some ownership over the work they were doing, some agency in the process?

My hunch at the time was that it was a combination of all of those things, and in subsequence semesters, I got to see that transformative power translate to other classroom experiences, where students had the same level of creative agency and responsibility for the direction of the work.

For example, in my spring 2016 black history survey, my students and I spent the entire semester examining the history and memory of black life at Kean University, where I teach. Using the school’s special collections as well as primary sources from other local archives, and conducting select oral history interviews themselves, students in this class worked to build an institutional history of race relations at Kean, telling the story of the dynamics of race and power at the school and on its grounds over the past 250 years. The course culminated with the development of The BlacKeaning: Illuminating Black Lives at Kean University, a campus tour highlighting this racial history of the school. I would say that that experience was similarly transformative for the students involved, and it made a comparable impact on me as well.

The project developed incredibly quickly, from conceiving of the idea to presenting the findings in only a few months. What lessons did you learn that helped move it along so swiftly?

Yes, “incredibly quickly” is a good way to put it. It was an unbelievably packed semester. I’ve never experienced a class so energizing and enervating at the same time. And it wouldn’t have been possible without the generous guidance and support of so many seasoned oral historians (Don Ritchie, Stephen Sloan, Linda Shopes, among others), and of the regional oral history association – Oral History in the Mid-Atlantic Region – and Kean University. Knowing that these various institutions and individuals had our backs gave me the confidence to undertake such a project, and showed my students that people were taking them and their work seriously.

I’ve never experienced a class so energizing and enervating at the same time.

I think the biggest takeaways from that spring, for me, were about preparedness, communication, and vision. I won’t rehash the things that went well in our development of the project – they’re in the OHR essay – but there are two critical things that I wish I’d approached differently.

First, equipment and technology – our mics and recorders arrived just hours before the first student was to conduct her first interview. I had used the equipment before and knew it well enough that I assumed it was relatively intuitive, and so – because of the time crunch – I forewent the proper training with the students in the limited amount of time we had for it. They all figured it out, but not without a few blips and a fair amount of anxiety for them. If I could do it over, I would have built in a technology workshop so that we could have gone through it more deliberately and collaboratively, and they could have tested everything ahead of time.

Second, the nature of the project was such that once the students graduated at the end of the semester, there was no built-in mechanism for completing the work. Such is the nature of the academic rhythms. While the project continued, through independent study and internship credit and collaborations with a neighboring institution, Stockton University, if I were to do it again, I would have thought more proactively about the longitudinal nature of the project and set up an infrastructure to develop that.

You noted that the project facilitated “a level of agency, autonomy, and affirmation that undergraduates…rarely get to experience.” Do you have any advice for educators that hope to foster similar kinds of transformation and camaraderie in the classroom?

I think developing a rapport among students is incredibly important. Before they can begin a meaningful collaboration, they need to understand where everyone is coming from, what their relationship is to the subject matter, what their work styles are, even what kind of music they like to listen to. They need to know each other, in order to trust each other, to be able to rely on each other.

From my experience, I’ve also found that it’s a careful balance for the instructor, wanting to encourage and affirm the work, but also providing critical feedback and – as I said in the OHR essay – “tough love.” Because sometimes the students need to step up, and the instructor needs to be able to tell them that in a way that they can hear and respond to, without feeling marginalized or silenced. I don’t think I did this perfectly, and at times I think I leaned too much toward the encouragement side, at the expense of the quality of the interviews. It was a learning process for me, too, in that way.

What is the future of the project? Are you still gathering interviews?

We collected the last of the interviews in the summer of 2015, and I’m currently at work on a book based on the stories of the narrators, which is due out with Cornell University Press in 2018. As I’m working on the book, I’ve had conversations with a number of the narrators, specifically about their social media representation of the storm as it was happening. That’s created for me a powerful parallel narrative about their experiences of Hurricane Sandy and an interesting way to contextualize and make sense of some of their recollections in the oral history interviews.

At the same time, I’m in the early stages of working with an oral history repository, transferring the interviews over to them so that people around the world can access and use them.

How has the project changed your approach to teaching, or doing oral history?

I think the biggest impact of the project for me has been in seeing the power of a project-based approach. I knew that in the abstract, prior to Staring out to Sea, but seeing the impact of this work on my students had a profound effect on how I approach the classroom more broadly, as I discussed above in working with students on The BlacKeaning.

I haven’t had the opportunity since Staring out to Sea to conduct oral history interviews myself or work with students on an oral history project, but I very much look forward to that opportunity. I’m so proud of the work that my students did over those two years, and feel tremendously indebted to them for their willingness to take on such high-stakes work. At the same time, as I’ve noted, there are certainly things that I would do differently, and so I look forward to having the chance to apply the lessons I learned from that project, to do it better next time.

Is there anything you couldn’t address in the article that you’d like to share here?

I’d just like to take this opportunity to highlight the Pedagogy Section of the Oral History Review and to encourage your readers – those in both secondary and higher ed institutions – to consider how their work might contribute to our broader understanding of how to teach oral history. When Glenn Whitman first conceived of the section in 2009, he envisioned it as a space to highlight the growing scholarship on educational methodology, specifically as it relates to oral history. For Glenn and the rest of the OHR editorial board, one of the central missions of our field is to train the next generation of oral historians. The Pedagogy Section of the journal affords us the opportunity to think collectively about how to do that.

Where have you seen the transformative potential of oral history? Add your voice to the conversation in the comments below or on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, or Google+.

Featured image: “Hurricane Sandy . The Aftermath” by Hypnotica Studios Infinite, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Learning from disaster appeared first on OUPblog.

Unite to abolish ‘might makes right’

After 20 January, 2017, Donald Trump will command America’s enormous power. His order will launch a devastating attack on any country. Sanctions will descend at his pen stroke. Alliances will be his to offer.

Yet one kind of foreign power will defeat Trump—as it has defeated presidents for 40 years. This is the power that comes from the world’s consumers, who buy billions of dollars of oil a year from violent and repressive foreigners. In 2014, for instance, the average American household sent $250 to autocrats and armed groups, just by paying at the pump.

What puts Americans into business with men of blood abroad is a law we take for granted, left over from the days of the Atlantic slave trade. It’s our law for foreign natural resources, which still says that ‘might makes right.’

When Muammar Gaddafi seized Libya in a coup in 1969, American law made it legal to buy Libya’s oil from him. And then in 2011, when rebels seized some of those same wells, American law made it legal to buy oil from the rebels. America’s—and every country’s—default law for foreign oil is, ‘whoever can control it by force can sell it to us.’

This old law for oil fuels conflict and oppression. Imagine that New York had a law saying that any goods seized by force in New Jersey could be bought legally by New Yorkers. We’d see turf wars, kingpins, and protection rackets in New Jersey—just what we actually do see, on a much larger scale, in countries along the world’s main artery of oil, which stretches from Siberia through the Middle East to Africa.

Map showing ‘the oil curse’. Image by Leif Wenar. Used with permission.

Map showing ‘the oil curse’. Image by Leif Wenar. Used with permission.The map shows the oil states that are authoritarian or failed—this is ‘the oil curse.’ Because military control over oil wins big money, armed groups fight to seize the oil (as in Iraq and Libya). Because we buy oil from whatever strongmen can control it, they can crush protests, buy off threats and propagandize their people (as in Russia and Saudi Arabia).

For a generation, oil-cursed countries have sent the West its worst threats and crises: ISIS, Assad and the Syrian refugees, Putin’s aggressions, Gaddafi’s explosive plots, Al Qaeda, Saddam’s invasion of Kuwait, the Soviets’ nuclear surge in the 1980’s, Iran’s state-sponsored terror. And, over four decades, the Saudi regime has spent tens of billions of petrodollars to spread their intolerant, medieval version of Islam worldwide—which we now see mutating into home-grown extremism across Europe and inside America.

US presidents have tried three strategies to control the power of oil from outside the country. Some presidents have tried alliances with the petrocrats: the Shah of Iran, Saddam, Gaddafi, the Saudi kings. Some presidents have tried military action: Gulf War I, Gulf War II, Libya, drones. Some presidents tried imposing sanctions: on Iran, Iraq, Sudan, Syria, Russia. Americans argue over the morality of these strategies—but even beyond morality, what have the real results been on the ground?

CIA Director John Brennan gave his verdict in March. The Middle East is the worst it’s been in 50 years, Brennan told Congress, and it faces unprecedented bloodshed. All of these presidential strategies have failed. The power of oil can’t be checked from outside oil-cursed countries.

The power of oil can only be controlled from inside these countries. In countries where the government is even minimally accountable to its citizens—like Canada, Mexico and Norway—oil does not fund civil war or despotism.

The United States can abolish its bad old law of ‘might makes right’ by passing a new law: we’ll only import oil from countries where there’s a government that’s minimally accountable to its people. We’ll taper off imports from all countries in black.

Economically, this will be easy. Nick Butler, a former top BP executive, says the transition could be made in months and would be virtually costless. With America’s help, our European allies could build new infrastructure and join us in a few years. The West doesn’t need to buy blood oil any more.

America’s taking a peaceful stand for the rights of all peoples will strengthen the democratic reformers in oil-cursed countries, who are the only hope for a durable peace in the Middle East. Today the peoples of oil-cursed countries are struggling against men who are using our money to oppress and attack them. It’s time to get on the side of the people.

Think of how angrily Americans have divided for 40 years over how to handle the oil curse: whether to invade or not, impose sanctions or not, tighten national security at the expense of our personal freedoms. So much bad blood from our fights, even between Americans of good will.

Americans can now come together in affirming a principle from Lincoln’s first inaugural address: a country belongs to its people.

‘Why should there not be a patient confidence in the ultimate justice of the people?’ asked Lincoln. ‘Is there any better or equal hope in the world?’ Our best hope to abolish the oil curse is to unite in our faith, as Lincoln also said, that ‘right makes might.’

Featured image credit: ‘Oil pump’, by skeeze. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Unite to abolish ‘might makes right’ appeared first on OUPblog.

What’s in a name?

In September 2015, the UK Met Office and Met Éireann (the Irish meteorological service) announced a project to give names to potentially damaging storms. The basis for naming any particular storm was the expectation that there would be major impacts on conditions over the British Isles and, in particular, of very high winds. But the very first winter that this scheme was applied, the winter of 2015/2016, not only did some of the named storms bring high winds, but they also caused exceptionally heavy rain and consequent devastating floods.

The first storm, Abigail, brought high winds to northern Scotland and the Outer Hebrides, and heavy rain farther south in Cumbria. The next, Barney, was accompanied by high winds (particularly over Ireland) and more heavy rain, as was the third storm, Clodagh, when there was a gust of 84 knots (156 kph or 97 mph) at High Bradfield in South Yorkshire.

But it was Storm Desmond that brought real trouble on 4—6 December. It had moderately high winds, but dumped a vast quantity of rain, most of it on Cumbria. Honister Pass experienced the new British rainfall record for 24 hours, with 341.1 mm between 18:00 GMT on 4 December and the same time on 5 December. Nearby Thirlmere set a new British rainfall record of 405 mm for the 48 hours to 09:00 GMT on 6 December.

Part of the trouble was caused by the fact that November 2015 had been the second wettest recorded since 1910 (only 2009 was wetter). The ground was already waterlogged before Desmond arrived. The resulting flooding was widespread, especially in Cumbria, where the West Coast Main Line to Scotland was cut. Lancashire, Northumberland, (with flooding on the River Tyne) and southern Scotland were also badly affected. Tens of thousands of homes were flooded in numerous towns and villages, and particularly in Carlisle, where the River Eden overflowed. The heavy rainfall also caused major problems and flooding in both Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic.

But then Storm Eva arrived, with high winds on 23 and 24 December, but brought still more heavy rain on 25 and 26 December. This time the worst flooding was farther south, in Lancashire, northern Manchester, and across the Pennines to West Yorkshire. The torrential rain on Boxing Day caused major flooding as the water moved downstream, such as at Hebden Bridge in Yorkshire and York itself. Thousands of more homes and businesses were flooded and at least 20,000 were without power. This single storm brought about three-quarters of the rainfall normally expected for the whole of December. Falling on saturated ground, and with rivers already in full spate, widespread flooding was inevitable.

Storm Frank arrived at the end of December and this time particularly affected southern Scotland, with thousands more homes flooded, including in Dumfries. Farther south, a band of heavy rain produced severe flooding in southern and south-eastern Ireland.

Storm Sea wind by mcian157. Public Domain via Pixabay.

Storm Sea wind by mcian157. Public Domain via Pixabay.There was a succession of lesser depressions with winds and rain in the New Year, but on 29 January, Storm Gertrude arrived. This tracked much farther north, mainly affecting northern Scotland with exceptionally high winds. The highest gust of the winter, 91 knots (169 kph or 105 mph) was recorded at Baltasound in Shetland.

At the beginning of February, Storm Henry brought strong winds to most of Scotland, which was followed by Storm Imogen on 7 February. That took a more southerly track and produced heavy rain and high winds over southern England (a gust of 81 knots = 150 kph or 93 mph at the Needles on the Isle of Wight), with gigantic swell waves affecting south-west England. The lowest pressure (962 hPa) of the winter was recorded at Lerwick in Shetland on 7 February.

That was the winter of 2015/2016. Of course, terrible weather and floods occurred before storms were named. In the winter of 2009, there was extreme rainfall in Cumbria. Then part of Workington being isolated when a bridge collapsed, with the death of a policeman who was trying to divert traffic away from the danger. There was more than two metres of water in parts of Cockermouth. The British rainfall record for 24 hours was set between midnight 9 November and midnight 10 November, when 316 mm of rain fell on Seathwaite in Borrowdale. That record was to be broken in December 2015, when Storm Desmond brought 341.1 mm of rain to Honister Pass. The rainfall in 2009 appears to have resulted from a phenomenon, recently given a specific name: an ‘atmospheric river’, which turns into what is known as the ‘warm conveyor belt’ within a depression system.

Featured image credit: Waves by NeuPaddy. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post appeared first on OUPblog.

January 19, 2017

Emotional dynamics of right-wing political populism

Donald Trump’s election to the 45th President of the United States is the biggest victory of contemporary right-wing political populism to date. The Brexit referendum had already shattered Europe and the UK “remain”-voters alike, but Trump’s win is of worldwide significance. The outcomes of both elections took the media, pollsters, and political analysts in the relevant countries and elsewhere by surprise. How could these campaigns that for the most part relied on exaggerations and deliberate falsehoods, and in Trump’s case also on openly racist, sexist, and protofascist statements defying the established standards of political debate, prevail?

As a philosopher and a sociologist who have investigated the social life of emotions for well over a decade, we believe that the success of right-wing populism must be examined in a longer-term perspective that accounts for social structural and psychological factors alike. Traditionally, the rise of the populist right has been linked to fundamental socioeconomic changes fueled by modernization, globalization, and economic deregulation. Although these developments certainly contribute a great deal to the rise of new right, they remain just one part of the larger picture. We suggest that emotional processes affecting people’s identities are a further crucial part of this picture. They can make a substantial contribution to understanding why the new right has become so popular, not only among low- and medium-skilled workers and people living in rural areas, but also among the middle classes. These segments of society are especially prone to both economic and cultural insecurities that manifest as fear of not being able to live up to salient social identities and their constitutive values, and as shame about these (actual or anticipated) inabilities.

Dollars by NickolayF. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

Dollars by NickolayF. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.An alarming piece of evidence of this kind of precarization that cuts through society is a recent finding that 47% of Americans would have trouble finding $400 to pay for an emergency. This standing financial insecurity is a hidden source of shame and humiliation for many middle-class Americans, as the journalist Neal Gabler points out in his May 2016 cover story in The Atlantic. The link between precarization and shame is particularly salient in contemporary capitalist societies where responsibility for success and failure is increasingly individualized, and failure is stigmatized through unemployment, living off welfare benefits, or labor migration. Under these conditions, we identify two social psychological mechanisms that fuel support for the new populist right.

The first mechanism of ressentiment explains how negative emotions – fear and insecurity, in particular – transform through repressed shame into anger, resentment, and hatred towards perceived “enemies” of the self and their social groups, for instance immigrants, the unemployed, political and cultural elites, and the “mainstream” media. We believe that the prevalence of repressed shame – and hence of the ensuing anger and hatred – is closely associated with the established structural determinants of support for right-wing populist parties, in particular economic de-regulation, globalization, and privatization. Repressed shame therefore constitutes a social mechanism that mediates between structural changes on the one hand, and voting behavior as well as other forms of support for right-wing parties and movements on the other hand. The rhetoric of populist parties is carefully crafted to deflect shame-induced anger and hatred away from the self and instead towards the political and cultural establishment and various Others, such as immigrants, refugees, and the long-term unemployed. This is why structural changes like globalization and economic liberalization – the actual causes of many of the events that provoke individual shame – get off easy, paradoxically even receiving support when figureheads like Donald Trump are voted for.

The US presidential election shows on an unprecedented scale how this bias operates when the relevant emotions are shared across social groups.

The second mechanism relates to the emotional distancing from those social identities that in contemporary capitalist societies progressively inflict shame and other negative emotions and are thus liable to alienation. This especially concerns identities that are tied to resources allocated on the basis of competition, in particular for people who already occupy precarious positions. Certain occupational identities are a good example. Many of them were steady and consistent throughout the first half of the 20th century, and, as such, central building blocks of public recognition, esteem, status, and prestige. When these identities become vulnerable and unstable due to the structural changes discussed above, people increasingly embrace identities still perceived to be emotionally appealing, stable, resilient, and to some extent exclusive, such as nationality, ethnicity, religion, language, or traditional gender roles. These are also identities in which solidarity with and belonging to other group members can still be experienced, unlike in the context of those identities where individuals are steadily competing with one another.

Bernie Sanders by Phil Roeder. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Bernie Sanders by Phil Roeder. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.We can see these two mechanisms in operation in the US presidential elections. Trump’s success in the Rust Belt states of the Midwest, commonly characterized by a declining industry, has been described as decisive for his election. These states have traditionally voted Democrats, but they now turned to Trump whose protectionist and revivalist promises, together with his blame of immigrants and other minorities, “corrupt” media, and political elites, appealed to the white workers in these states. Hillary Clinton has been blamed for neglecting these voters in her campaign, and some have argued that the strong focus of Democrats on identity politics instead of on issues of inequality led many to vote for Trump. However, there is evidence that even the more radical Bernie Sanders, who opposed free trade agreements and advocated a national $15 minimum wage, free healthcare, and free college education, would not have beaten Trump in the Rust Belt as writer and political scientist Marcus Johnson argued in The Huffington Post. While Democrats indeed proposed socioeconomic improvements to people’s lives, it was still Trump who prevailed, as he managed to tap into the anger, outrage, and frustration that emerged from the present socioeconomic situation of the electorate. The fact that he was able to channel these emotions – which may not have had clearly identifiable targets in the first place – towards various “Others” whom many were ready to perceive as enemies of their salient social identities fits the picture of the two emotional mechanisms of right-wing populism we propose.

Finally, emotions mobilized by populist parties, such as anger, resentment, and fear, are also important for political reasoning, as they affect how people perceive reality and make judgments. Research shows that emotions can systematically bias information processing in ways that make people neglect counterevidence to their favored views and convictions. This certainly was instrumental for citizens’ willingness to accept Trump’s lies and exaggerations on matters such as the role of President Obama in the rise of ISIS, the number of illegal Mexican immigrants in United States and their criminal record, the US unemployment rate, or the number of Syrian refugees Obama plans to permit into the America. The US presidential election shows on an unprecedented scale how this bias operates when the relevant emotions are shared across social groups.

Featured image credit: Make America Great Again slogan worn by a Trump supporter by Gage Skidmore. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Emotional dynamics of right-wing political populism appeared first on OUPblog.

Shakespearean Classics: Titus Andronicus, Ovid’s Metamorphoses, and a new papyrus of Sophocles

In Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus, Titus’s daughter Lavinia is brutally raped by Demetrius and Chiron. They prevent her from denouncing them by cutting out her tongue, and cutting off her hands. But as we see in the passage below, Lavinia nevertheless communicates their crime by pointing to a passage of Ovid’s Metamorphoses describing Tereus’s rape of Philomela. Guiding a staff with her mouth and stumps, she then writes her attackers’ names in the sand, leaving her father Titus to exact a terrible revenge.

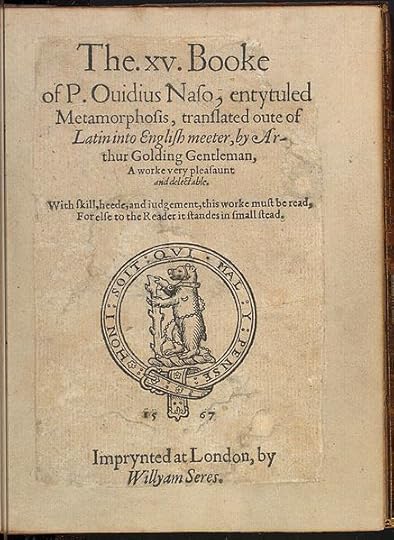

‘The xv. Booke of P. Oudious Naso, entyltuled Metamorphosis, translated oute of Latin into English meeter by Arthur Golding Gentlemen’, from the Schoenberg Center for Electronic Text & Image (SCETI). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

‘The xv. Booke of P. Oudious Naso, entyltuled Metamorphosis, translated oute of Latin into English meeter by Arthur Golding Gentlemen’, from the Schoenberg Center for Electronic Text & Image (SCETI). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Known to Shakespeare both in the original and through Arthur Golding’s influential translation (1567), Ovid’s epic poem describes how king Tereus of Thrace, after marrying the Athenian princess Procne, returns to Athens to fetch Philomela, Procne’s sister, for whom she had been pining. On the way, however, Tereus rapes Philomela and cuts out her tongue. Hidden away in the countryside after their arrival in Thrace, Philomela is discovered by Procne and reveals Tereus’ crime through a piece of weaving. The sisters wreak vengeance by killing Itys, Procne’s child by Tereus, and serving him as a meal to his unknowing father. On discovering the truth, he pursues them, only for the gods to turn them into birds: Procne into a nightingale, Philomela into a swallow, Tereus into a hoopoe.

Behind Ovid’s account stands Sophocles’ influential lost play Tereus, the earliest work known to tell this gruesome story. Only a few fragments of the drama survive; but the publication in 2016 of a papyrus dating to the second century, from Oxyrhynchus in Egypt, gives a precious glimpse into a crucial scene from this lost masterpiece. After a speech in which Procne bitterly laments the fate of married women – but before she has learned of her sister’s dreadful fate – a shepherd enters with news so significant, and so strange, that he promises to swear an oath that it is true. Telling Procne that he has come from a hunt, he describes his journey through the countryside. The papyrus breaks off just as we reach the Greek word for “hut.”

That hut will be the place where he has discovered the mutilated Philomela, news of whom he is now bringing to his queen. Sophocles’ Philomela, then, like Ovid’s, is imprisoned in the countryside after Tereus’ crime; so too Shakespeare’s Lavinia is left “in the ruthless, vast, and gloomy woods.” Ovid’s Philomela is discovered at a religious festival, but Shakespeare changes this detail. He has Lavinia discovered after a hunt, thereby unknowingly aligning his play with the Sophoclean drama which inspired Ovid, since (as we can now infer from the papyrus) the same is true for Sophocles’ Philomela.

It is natural enough for someone hidden in the country to be found by a man traversing the wilds as he hunts. But at a deeper level, the mention of the hunt is appallingly appropriate to the situation in which Procne and Lavinia find themselves. Both women have themselves been the object of a (perverted) hunt; both women have been tragically treated with a cruelty exceeding anything meted out by a regular hunter to his prey. And both will initiate the pursuit and punishment – the hunt, we might say – of the men who thought that they had thereby rendered them powerless.

As Colin Burrow points out in his recent book Shakespeare and Classical Antiquity (2013), “Shakespeare almost certainly never read Sophocles or Euripides (let alone the much more difficult Aeschylus) in Greek, and yet he managed to write tragedies which invite comparison with those authors.” So it is fascinating to see, thanks to the papyrus, this similarity between Shakespeare and a play that he could not have read even if he had wanted to. There is no question here of influence; we rather perceive the matchless dramatic instinct, independently honed, of two of the world’s greatest playwrights.

Featured image credit: ‘Nicolas Poussin, Apollo and Daphne (1625)’ from the Alte Pinakothek. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Shakespearean Classics: Titus Andronicus, Ovid’s Metamorphoses, and a new papyrus of Sophocles appeared first on OUPblog.

American Christians and the Trump vote: what’s law got to do with it?

The 2016 US election is over, and now begins the elaborate work of attempting to understand why Americans voted the way they did last year. Amid soul-searching about media bias, liberal smugness, and misleading data, many commentators have begun to set themselves to the task of making sense of the surprising proportion of American Christians – both Protestant and Catholic – who ultimately cast their ballots for a candidate such as Donald Trump.

Notwithstanding the many surprises of this election, one characteristic of Trump-supporting Christians is likely to remain a certainty: such Christians were deeply adverse to the possibility of a Democrat being in a position to appoint one or more justices to the US Supreme Court.

How has the Supreme Court come to assume such a pivotal position in the eyes of American Christians this election? Some answers to this question are more straightforward than others. Perhaps the most immediate of answers is the vacancy created last year by the death of conservative paragon Antonin Scalia. While this election was marked by repeated invocations of the threat of “radical” liberal appointments to the Court, this threat has taken on particular urgency in its reference not merely to potential future appointments, but to the actual vacancy left by the Court’s most vociferous conservative.

Setting aside the pressing case of Scalia, however, it is useful to consider a somewhat less straightforward answer to the question of why so many Christians have shown themselves willing to afford pride of place in this election to the Supreme Court. This answer revolves around a conviction, widely held among such Americans, that the Court has become hostile to Christianity and, perhaps, to religion in general.

Where does this perception come from? Is there any truth to this assessment of the Court? I have explored these questions and sought to provide an understanding of how it is that so many American Christians have developed the impression that the judicial system is stacked against them. And, though it will likely strike many legal professionals as uncomfortable, my conclusion is that such Christians have good reason to have come to this conclusion, at least when it comes to the high-profile issue of same-sex marriage.

In my previous work, I outlined a trajectory of landmark Supreme Court cases that has served to constrain the ability of so-called traditional marriage advocates to raise religious or even broadly moral objections to same-sex marriage within the courtroom. This trajectory has given rise to a series of discursive acrobatics within the traditional marriage movement, as advocates have endeavored to “secularize” their courtroom arguments by focusing on children’s welfare or social stability rather than upon the religious beliefs and doctrines that so clearly inform their positions on this issue. With full awareness of the many important reasons that exist for refusing to allow religious arguments to serve as foundations for public policy, legal scholars and professionals should nevertheless take seriously the likelihood that this increased constraint will be perceived by many Americans as an unfair burden upon their exercise of religion. To fail to take this phenomenon seriously, I argued, is to risk exacerbating a perception held by many Americans that the courts are fundamentally hostile to religious conservatives. It also quite possibly risks contributing to a turn among such conservatives to the other two branches of government for remedy against an “activist” Court.

The landmark ‘Obergefell v Hodges’ decision ultimately exemplified many of the concerns raised. In ‘Obergefell’, I argue, the Court demanded and then rejected precisely the brand of secularized argumentation that I described in 2014. In so doing, it not only handed a definitive defeat to a legal strategy that has been a mainstay of contemporary traditional marriage advocacy, but it also reproduced and even inflamed a set of deep-seated tensions lurking at the heart of our liberal democratic legal system.

Amid the post-election soul-searching now underway, it is important to consider the manner in which the significant Christian backing of this most unchristian candidate is at least partly a symptom of a broader history of church-state jurisprudence that has left many Americans simultaneously contemptuous of the Supreme Court and eager to see their elected representatives take the Court in hand in the name of religious freedom.

Image credit: U.S. Supreme Court Building by AgnosticPreachersKid. CC-BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post American Christians and the Trump vote: what’s law got to do with it? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 237 followers